Abstract

Food and gastronomy are important features of the identity of cities, regions and countries, contributing therefore significantly to their branding. This contribution is possible through the multiactor value co-creation in the place. The aim of the article is to analyse the links between processes of co-creation of agricultural and gastronomic value through the integration of systems of production and gastronomy. Evidence is provided that food and agriculture are moving towards a holistic service logic integrating sector subsystems into broader inter-industrial ecosystems. The paradigm of Service-Dominant Logic offers a framework for analysing interactions between multiactor engagement processes, and food/gastronomy service linked to places and their cultural milieux. These complex processes of co-creation are mapped, then applied to the case of agriculture and gastronomy in the Basque Country in Spain. The Basque gastronomic co-creation brings together the rural context of smallholders, fishermen, or farmers, service providers, and the urban context of cities, with their circles of social interaction and events, where service users are largely concentrated. Crucial role in the system—as institutional innovators—is played by the Basque chefs who integrate the different aspects of food production and consumption.

Keywords: Food and gastronomy, Place branding, Value co-creation, Service-Dominant Logic, Ecosystem, Basque Country

Introduction

Gastronomy, the enjoyment of fine foods and beverages, is a natural and relevant dimension of place branding (Berg and Sevón 2014; Freire and Gertner 2021) as food and gastronomy form the place offerings, are part of its experience, represent place heritage and its identity. The meaning of agriculture products and associated gastronomic services are also components of public diplomacy (Suntikul 2019), where the term ‘gastrodiplomacy’ was coined to involve food’s role in public diplomacy, which exposes broad public audiences to a nation’s food culture to “enhance the edible nation brand” (Rockower 2014, p. 14). At the same time, place branding is moving towards a new mind-set or logic that involves multiple stakeholders (Houghton and Stevens 2010; Kavaratzis 2012; Stubbs and Warnaby 2015; Muñiz-Martínez 2016) as complex systems of interactions. As Kavaratzis and Hatch (2013, p. 76) discuss, “there seems to be an agreement that both the place brand and place identity are formed through a complex system of interactions between the individual and the collective, between the physical and the non-physical, between the functional and the emotional, between the internal and the external, and between the organized and the random”.

The aim of this study is to present a shift from schemes based on a Goods-Dominant Logic tied to local production, towards gastronomic service ecosystems that encompass multi-actor holistic branding of food and gastronomy, businesses and places.

From a manufacturing perspective, there is a solid body of academic literature and practice concerning the concept of “country-of-origin” effects (Dinnie 2004). This has provided evidence for a relationship between a country’s image and the reputation of the products it creates, and the prestige or brand awareness generated by the “made in X” effect. Some regions pushed hard to become recognized places of origin for products, whether foods or beverages (Andéhn and Berg 2011). In response, the European Union devised the Protected Designation of Origin (PDO), Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and Traditional Specialties Guaranteed (TSG) schemes to designate agricultural products and foodstuffs of quality associated with a specific location of production. A designation of origin provides a guarantee of quality for consumers, as also of unique characteristics that are lacking in similar products made in another region, or with different raw materials, or by mass industrial processing.

This concept of regional origin seems to be expanding and nowadays includes not only countries, but also regions and cities. It is also shifting from the location of production to a wider and more holistic place branding process (Andéhn and Berg 2011).

These holistic processes entail value co-creation among multiple socio-economic actors. Service-Dominant Logic (Lusch and Vargo 2014; Vargo and Lusch 2016; and the Nordic School of Service Management and Marketing, led by Gummesson and Grönroos) has made a significant contribution to the science of marketing and service (Maglio and Spohrer 2008), stating that value is co-created by multiple service providers, such as firms, organizations and social entities, and by service users, like consumers, residents, tourists and organizational or individual customers, in multiple complex exchanges through many-to-many marketing (Gummesson 2006). However, Service-Dominant Logic is relatively silent concerning the study of places and furthermore their branding, within the broad concept of “servicescape” (Bitner 1992; Fisk et al. 2011).

Therefore, on the basis of Service-Dominant Logic theoretical framework, an exploratory case study analysis was conducted of gastronomic features in a region of Europe, namely the service ecosystem of food and gastronomy in the Spanish Basque Country. Within this area, the City of San Sebastian has emerged as a centre of gastronomic creativity and of excellence in food. The local context provides high-quality foodstuffs and a socio-cultural identity centred on food as a major element in human social interaction. These represent the cultural and institutional background that has given rise to this food and culinary service ecosystem, upon which place branding has been co-created and new experiences emerge.

Theoretical background on Food and Gastronomic Place Branding

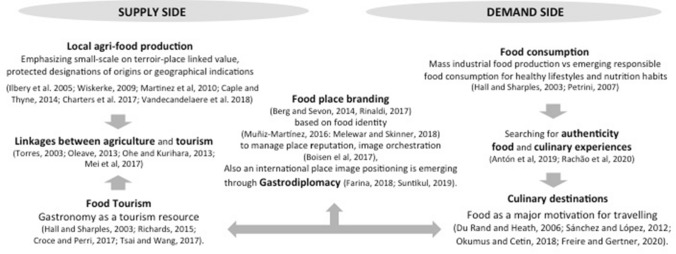

Research on food and gastronomy has been adopted from various multidisciplinary approaches (Rinaldi 2017), being essentially divided into supply side and demand side (Lee and Scott 2015). This section briefly discusses the various theoretical-conceptual streams that the authors have identified and used as the theoretical framework for further discussion (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical streams of research and approaches on food place making and branding.

Source: own compilation

The supply side

While the twentieth century consolidated a system oriented towards the mass production of agro-food products, this intensive industrialisation has shown negative consequences, such as damaging biodiversity and overexploiting natural resources, which calls into question the environmental and social sustainability of this model, as The Brundtland Report (Brundtland et al. 1987) warned. Other negative implications have also emerged, such as consumers' mistrust in agro-industrial food, environmental pollution and increasing prevalence of obesity and malnutrition (Wiskerke 2009). Thus, alternative local food systems (Martinez et al. 2010, p. 3) emerge as "food produced, processed and distributed within a geographical boundary that consumers associate with their own community". As a result, in recent decades, local agro-foods linked to specific territories have been re-valued. This acquires an economic value in the form of the relationship of agro-food products with their local territory—terroir (Charters et al. 2017) that contains a geophysical and a cultural dimension (Caple and Thyne 2014). The human-cultural value resides in ancestral knowledge passed down through generations, forming a heritage of cultural territorial identity.

Territorial identity based on local food is the basis for channelling inter-industrial service vectors between agricultural food production and tourism (Telfer and Wall 1996; Sims 2009). While mass industrial agri-food production resulting from globalisation implied long marketing channels that led to a separation and distance between producers and suppliers on the one hand, and customers and end consumers on the demand side, the growing appreciation of local quality production with territorial certifications implies a paradigm shift that makes rural development possible (Rinaldi 2017). The change is also sustainable to the extent that small-scale production takes precedence over mass production. This way, complex interactions are formed, in which multiple senses converge in culinary-gastronomic experiences: smell, taste and tactile senses (Berg and Sevon 2014). The growing cultural dimension of the traditional landscapes combines works of nature and humankind, expressing a long historical heritage relationship between people and their natural environment (https://whc.unesco.org/en/culturallandscape/). Thus, many rural territories in developing countries of the world (Vandecandelaere et al. 2018) can co-create value to become food place brands based on their cultural identities (Muñiz-Martínez 2016).

In this way traditional food and cuisine become tourist attraction providing links between traditional values of conservation and stability with modern values of dynamic innovation and change (Bessière 1998). Thus, places are reimagined beyond mere places of production, via designations of origins, or beyond the country-of-origin effect (Andéhn and Decosta 2018), towards new symbolic values, narratives of authenticity, and cultural storytellings that creatively combine the best of the traditional and the avant-garde.

The demand side

The previous research streams focus on the supply side of food value co-creation, on its service providers and their link with the territory. In the meantime, there are also emerging streams oriented towards the demand side of food consumption and gastronomic tourism. The latter is reflected in food destination marketing. In general, new forms of food consumption which value the local products whether in homes or as motivations for visiting places appear, where multi-sensory experiences of authenticity are linked to the territories and turned into sophisticated agro-gastronomic themes (Hjalager 2002; Hall and Sharples 2003). In such experiences, food and drinks are often paired (Rachão et al. 2020), and the user, who is referred to as a foodie (Richards 2015), often adopts roles of active participant, learning and sharing knowledge and emotions (Schau et al. 2009).

Food and gastronomy represent important dimension of territorial identity and destination marketing (Du Rand and Heath 2006; Sánchez and López 2012; Okumus and Cetin 2018; Freire and Gertner 2020). Likewise, gastronomy constitutes a basic element of the attractiveness of tourist powers, such as France (Frochot 2003), or Spain and Italy through healthy Mediterranean gastronomy (de Salvo et al. 2013).

Food and gastronomic place branding

Beyond mere place promotion actions based on food features or place marketing exchanges, that use to be supply centric or top-down approaches (cities authorities, governments, politicians, public servants, consultancies, business clusters, etc.), food constitutes an element of cultural-territorial identity (Montanari 2006) (and place brand identity) from which a cultural-territorial image (and place brand image) is projected. Place branding entails supply and demand sides, it serves as an integrative holistic complex process of managing place identity and place image (Boisen et al. 2018), among multiple actors, both providers and place users (citizens, tourists, visitors, students), each constructing their own image.

While in agro-food production, the territory is conceptualised as a physical-geographical place of production; in place marketing the territory is a social construct where market exchanges and social interactions converge; in place branding (Berg and Sevón 2014; Rinaldi 2017) value co-creation processes, food, either meals or beverages, culinary or gastronomy, are key elements of place identity and projection of image and cultural significance.

The complexity of inter-territorial synergies and inter-industrial linkages as well as the multiple actors involved in these processes, has led to the emergence of a research stream that conceptualises the complex exchanges under holistic systems logic. The links between cities and their regions (Jennings et al. 2015) are fundamental and are based on synergies between the ecological, social and economic dimensions (Vandecandelaere et al. 2018).

Methodological foundations

Food studies have tended to analyse natural and social dimensions separately (Goodman 1999), using dichotomous structures that divide material from ideal, external from internal, static from active and objective from subjective, resulting in narrow conceptual frameworks. It would be appropriate to move towards approaches that encompass production, distribution, retailing and consumption, micro and macro levels, and food as a social system and a biological basis (Lockie and Kitto 2000). Little attention has been paid to the integration of complex ecosystems maintaining a balance between the ecological and natural dimension, and the human ethical dimension. Service-Dominant Logic offers a framework for such an integration.

Thus, within Service-dominat Logic, in addition to micro interactions between the parties directly involved in exchanges, Lusch and Vargo (2014) proposed consideration of broader –macro- levels of value co-creation at national or global spheres, and a meso-level intermediate level related to the market or industry. Their proposal extended relationships beyond dyadic exchanges towards holistic actor-to-actor (A2A) frameworks, zooming-out actor engagement (Alexander et al. 2018; Fehrer et al. 2018), encompassing multilevel value co-creation from an ecosystem perspective (Akaka and Vargo 2015; Frow and Payne 2018).

The need to bring in multiple actors has also been recognized in the field of place branding, because it became evident that in any region there are various stakeholders involved (Kavaratzis 2012; Stubbs and Warnaby 2015), as there are in place branding based on food or beverages (Muñiz-Martínez 2016).

Actor-Network Theory (Callon 1999; Latour 2007) provides a conceptual basis for conceiving cross-sectional relationships between the natural, environmental, and agricultural subsystem, and the food and gastronomy human and social sub-system, tending towards the common good (Goodman 1999). Earlier analyses have adopted industrial perspectives, such as tourism and food production (Ilbery et al. 2005; McKitterick et al. 2016). However, such sector-based approaches would seem to point to the absence of any holistic analysis that incorporates food and gastronomy within the complex images of cities and regions (Berg and Sevón 2014). Consumers seek solutions, not merely products (Sawhney 2006; Gummesson et al. 2010). Hence, Service is a more appropriate and integrated logic than Goods-dominant Logic, based on the production and distribution of products.

In the fields of economics and of business management, value creation has also been studied from a sector perspective, divided up into economic compartments or industries, according to products or outcomes. However, complex many-to-many marketing (Gummesson 2006) in the contemporary post-industrial world implies cross-sector interactions. These co-creation processes entail synergies between sectors which should be viewed from a more holistic perspective. For example, it has been suggested that there is a symbiosis between agriculture and tourism (Bowen et al. 1991; Telfer and Wall 1996), with links between small-scale agriculture and tourists in pursuit of sensory experiences, since culinary pleasures are often combined with the image of beautiful surrounding landscapes (Bowen et al. 1991; Sims 2009).

The theoretical and conceptual framework postulated in this paper is based upon a network approach and systems thinking to address the complexity of value co-creation, and Service-Dominant Logic (Lusch and Vargo 2014) allow to integrate and map processes of inter-industry interacting subsystems.

Whilst the notion of networks captures the complexity of structures, if in a somewhat static way, the concept of systems expresses dynamic interactions among actors and interchange flows (Vargo and Lusch 2008; Barile et al. 2016). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the two concepts and the integrated role of Service-Dominant Logic in the food and gastronomy ecosystem applied in the case of Basque country.

Table 1.

Network approach, Systems Thinking and Service Dominant Logic to address the complexity of agro-food multiactor value co-creation

| Network approach Complexity theory |

Systems thinking | Service ecosystems within Service-dominant Logic and application to the Basque food and gastronomy system |

|---|---|---|

|

Networks are non-hierarchical structures of objects connected to other objects or nodes through links, in a somehow static way Complex systems entail a large number of elements that interact dynamically Socio-economic actors are connected to other actors, forming a network. When this brings together a whole that is greater than the sum of its interdependent parts, it forms a system |

Living systems are integrated wholes whose properties cannot be reduced to those of smaller parts. Every organism, whether a micro-organism, an animal, a plant, or a human being, is an integrated whole, a living system, which contains smaller communities of organisms, such as leaves or cells, and is nested within broader systems. These larger systems may be social systems, such as a family, a business organization, a city, or a biological ecosystem |

Service-Dominant Logic states that value is co-created among multiple actors, including users and beneficiaries (axiom 2), and that all social and economic actors are resource integrators (axiom 3) This means that in the Basque country, within a socio-cultural milieu, many stakeholders integrate public and private resources in food value co-creation, interacting through multi-actor engagement, thus forming the Basque gastronomy ecosystem |

| Multiple actors interact within a hybrid networked connectivity. As a result, social systems are non-linear and asymmetrical | The shift of perspective from the parts to the whole also entails a shift from objects to relationships. Thus, nodes (actors) and links (service flows) form systems | Classical management and marketing conceive of value from a mind-set of the production and distribution goods along linear value chains, here aimed at producing foods. Service-Dominant Logic, in contrast, sees processes of co-creation occurring in systems, where goods, in this case food, are mechanisms for service provision, in this case culinary co-creation |

| Complex systems evolve and are in a constant flow of change and imbalance. Symmetry and complete stability or equilibrium imply their death | Such a systems mind-set implies a change of methodological focus from quantities to qualities, from static structures to dynamic processes, from Cartesian certainty to epistemic approximate knowledge | |

| Western science is basically rational, and measures phenomena within a framework of Empirical Positivism. While the creation of value is difficult to observe, actor engagement is observable (Storbacka et al. 2016); and while relationships are also difficult to be empirically measured, relationships can be mapped (Capra and Luisi 2014). Thus, mapping mutiactor value co-creation represents an optimal tool to synthesize and visualize the complexity of the Basque Food and Gastronomic service ecosystem | ||

| There are loops in the interconnections. Feedback is an essential aspect of complex systems | Instead of searching for partial causality, systems require an understanding of patterns of interactive relationships as wholes | Value is co-created through Actor-to-Actor interactions, involving both service providers and service users. The customers and consumers of agriculture and gastronomy, whether local Basque residents or visitors motivated by food experiences, also co-create the value |

| Complex systems have histories and are context-dependent | Going beyond a search for cause and effect phenomena, complexity explores the whole that determines the patterns of its parts. Emergent systems are integrated wholes, whose properties cannot be reduced to those of smaller parts (Capra and Luisi 2014) | Service-Dominant Logic states that value co-creation is coordinated through actor-generated institutions and institutional arrangements (axiom 5). Food and gastronomic encounters represents a key identity element of the Basque and the whole Spain’s culture, thus provides a shared social meaning. This symbolic institution act as a social glue for people to interact socially |

| An outstanding property of all life is the tendency to form multilevel structures of systems within broader systems (Capra and Luisi 2014). A network is usually multi-dimensional, and the context determines which and how many dimensions are pertinent in each case (Gummesson 2017) | Within systems thinking, a multi-level value co-creation perspective is envisaged through direct interactions between providing actors and direct users or beneficiaries. This micro level is embedded in broader meso subsystems that form macro ecosystems when they interact | Service-dominant Logic recognizes the leading role of Prime Movers (Normann 2001), Institutional Entrepreneurs (Thornton et al. 2013), or Market Shapers (Fehrer et al. 2020), as visionary actors who integrate new resources, leading new value co-creation processes, and reconfiguring old structures into renewed systems |

| The emergence of a creative Basque food and gastronomy ecosystem was spearheaded by a group of chefs who raised cuisine to a new level of sensory creativity. Building on their ideas, local, regional and national governments have backed public initiatives. As a result, an holistic food and gastronomic service ecosystem has emerged | ||

Important for understanding of the ecosystem discussed is to to apply visualisation in the form of graphs (Gummesson 2017, p. 175), which map service ecosystems so as to reflect their processes of co-creation of value (Lusch et al. 2007). Graphic analysis aids in interpreting the density of actors and their interactions, with skill and knowledge exchanges, making it possible to visualize these through zooming-in and zooming-out (Chandler and Vargo 2011). Zooming-in shows direct interactions at micro level between single actors or prime movers, or small groups of them (Norman 2001). Zooming-out highlights holistic interactions at a macro level forming a service ecosystem (Vargo and Akaka 2012). Despite the systemic nature of organizations, the implications of this feature are poorly captured and often ignored in management (Barile et al. 2016).

The Development of an Agricultural-Gastronomic System in the Basque Country

Throughout history, the Mediterranean Sea has provided Southern Europe with the climatic conditions and cultural frameworks necessary to produce a wide range of foodstuffs. It was in this context that the concept of a terroir, a French word etymologically linked to terre (land), arose. When applied to wine, this refers to the unique characteristics of a vineyard, including its micro-climate, topography and soil, which together define a unique taste from a single place (Beverland 2006). By extension, terroir designations (Croce and Perri 2010) have been created to promote geographically earmarked high-quality products such as wine, olive oil, cheese, vegetables and fruit. Wine itself is increasingly combined with food to offer a complete gastronomic service (Frochot 2003).

With natural conditions and historical heritage both so favourable, at a more recent date the European Union has joined with food producers and local governments (Ilbery et al. 2005) to create an institutional system for agro-food products, the quality of which is linked to geographical denominations of origin, most of them relating to countries in Southern Europe. Furthermore, alongside this provision of quality products, a number of gastronomic trends have sprung up in various localities in given cultural contexts. In this way, culinary networks with cultural connections (Murdoch and Miele 2004) have been formed. One region where there has been the joint setting up of gastronomic creativity emanating from human skills and knowledge is the Spanish Basque Country.

The Basque Country, and within it the City of San Sebastian and surrounding county, is developing a sustainable production system for high-quality agricultural and marine food. In this area a group of talented, creative, skilled chefs (Martín Berasategui, Karlos Arguiñano, Pedro Subijana, Arzak -father and daughter, Andoni Aduriz) are co-creating a form of culinary excellence based on a combination of traditional high-quality food products and on new avant-garde gastronomy. This is giving the City and the Province a place-branding based on sensory experiences of food, attracting visitors and tourists (“foodies”), as well as those studying or otherwise enjoying gastronomy. As a result, a food ecosystem of value co-creation involving multiple public and private actors is emerging, in an institutional context of social and civic society encounters where sustainable food, and marine and terroir landscapes are key resources.

Unlike the creation of the New Nordic Food trend, spearheaded by the Noma restaurant in Copenhagen, where there was no real prior gastronomic heritage, the Basque Country movement has combined a tradition of quality products, with new culinary modernity linked to a sense of place. Tradition and modernity have been blended together (Bessière 1998). It may be asked how this small European region, known for sheep farming, fisheries, and heavy industry, and which for decades suffered the tragedy of ETA terrorism, has managed to put itself at the head of world gastronomy.

The Basque cuisine phenomenon was started in 1976 by chef Arzak and another dozen cooks, led by their teacher, Luis Irizar. The Basque Country already had a rich variety of folk recipes. These chefs took them, developed them and made them better, healthier, and lighter, giving them a touch of individual gastronomic innovation. They remained rooted in the peasant cookery “like grandma used to make” from rural farmhouses (caseríos) and popular dining societies (txokos). They relied on good products, such as fish from the Atlantic like anchovy or cod, and local vegetables, peas, artichokes, beans, mushrooms. A number of Basque cooks developed excellence in cuisine with enthusiasm and passion, despite lacking funds or any public support. They invested in trips to France to learn from nouvelle cuisine (Rao et al. 2003). Thereafter, they combined the great existing culinary tradition and quality of products with modernization, thanks to their skills and knowledge. Basque chefs thus made a name for New Basque Cookery, raising the status of Spanish gastronomy, together with Catalan chefs such as visionary chef Ferran Adrià – El Bulli Restaurant (Rao and Giorgi 2006), and the Roca brothers – El Celler de Can Roca Restaurant. They co-created new value on food, moving it to a sensorial art, beyond foods as a basic need, engaging in creative gastronomy, and adding value attraction for Spain as a country of culinary excellence, within one of the world’s top tourism destination.

This co-creation of value appeals to visitors and tourists seeking sensory experiences, whose participation is more active than merely being diners, since they can learn through cookery courses, and engage in culinary co-creation. In this way, gastronomy has become a basic motivation for travel to the Basque Country (as can be seen from the websites euskadigastronomika.eus and euskadigastronomika.es), attracting visitors, “foodies”, and others whose motive for a trip would be gastronomic experiences (Richards 2015).

With a population barely topping two million, the Basque Country, welcomes four million tourists, with arrivals spread out over the whole year. Such visitors are usually well-to-do, and have a high average spend per person of 1,500 euro (Rodríguez 2019). There have been attempts elsewhere to imitate this Basque culinary phenomenon. Singapore, Peru and the Nordic countries have banked on haute cuisine and gastronomy to attract quality tourism, especially Japanese, Americans, Swiss, and lovers of fine dining in general. This is similar to the way in which the early 2000s saw various cities around the world attempting to reproduce the Bilbao Guggenheim effect—also in the Basque Country- (Plaza et al. 2009), but with little success.

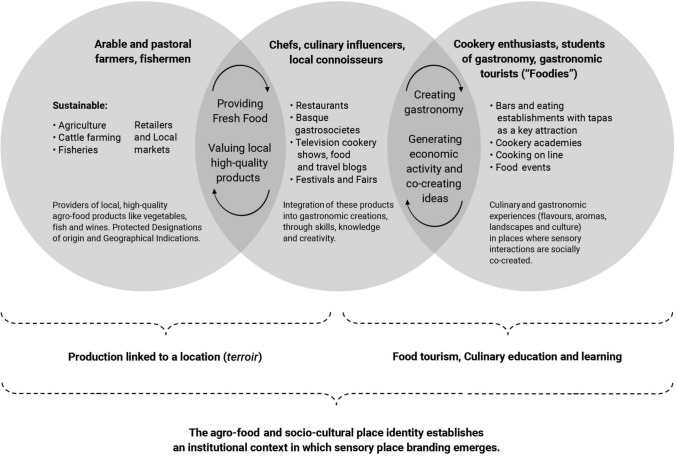

Meanwhile, the culinary co-creation is growing in San Sebastian (both the City and its Province), in the Basque Country (a constituent country), and in Spain as a whole (the Nation-State). Chefs play a focal role by bringing together high-quality agro-food products, raw materials produced by fishermen, arable and pastoral famers, and integrating this produce in the creation of gastronomy in their restaurants thanks to their creativity. Figure 2 shows the subsystems whose interactions shape a holistic agricultural and gastronomic ecosystem.

Fig. 2.

Sectors and Industries that Interact to establish a Holistic Agro-Food Tourist Ecosystem in the Basque Country.

Source: own compilation

Within the system, one popular institution that is a key to the identity and the passion of the Basques for cookery are the dining clubs known as txokos. They are a major strand in the social life of the Basque Country, in which members meet in premises with a kitchen to have a lunchtime or evening meal in the company of other affiliates, and sometimes families or guests. Such societies often organize cultural activities in the leisure and social life of a town. Those attending a dining club, whether members or guests, normally find that the cooking duties are shared by two or three of those attending the meal, using products they themselves have brought, although certain basic ingredients are normally available from the society’s communal store cupboard. After the meal is over, the expenses are calculated and shared among those attending.

These C2C networks and interactions in society reveal that gastronomy is a social, gregarious feature for Basques. It underlines their love for their roots, their enjoyment of landscape and sea, their respect for seasonal produce that reduces any unsustainability caused by transporting products from long distances, the pleasure they take from seeking out the best local products, and the fact that they enjoy planning, meeting, cooking, eating, drinking and singing. Hence, the average Basque feels a part of the gastronomic movement, even without ever having eaten in a three-star restaurant, according to the chef Andoni Aduriz.

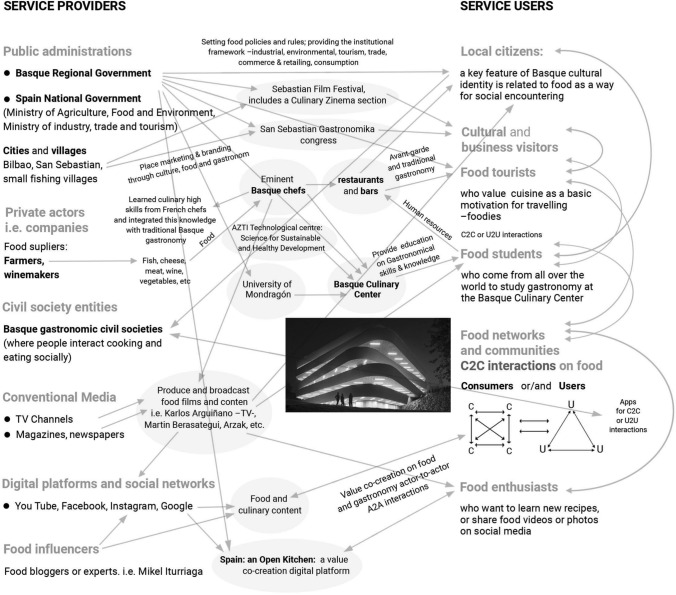

In the Basque food and gastronomy ecosystem (mapped in Fig. 3) there is participation by multiple socio-economic actors bringing together resources in processes that may be bottom-up, going from individuals to society, or top-down, running from public administration and government, whether municipal, Basque regional, Spanish national or European, down to consumers. There is co-ordination of the policies of various public administrations on these lines. For example, the Basque regional government’s strategic plan for gastronomy is aligned with the action plans issued by the EU with regard to environmental policies. This co-creation shapes a local sensory identity brand, confirming the theoretical and conceptual principles of Service-Dominant Logic, specifically Axiom 2: “Value is co-created by multiple actors, always including the beneficiary” (Vargo and Lusch 2016). Ferran Adrià, the leading chef with the El Bulli restaurant in Gerona in the Catalan region of Spain, has been elected the best chef in the world in several different years. He explains things by stating that this development in cookery began when chefs started collaborating with the primary sector, such as producers of craft cheeses, small wine makers and farmers. It had become clear that without such people no progress could be made, and the rarity of outstanding produce constituted a handicap in developed countries at that moment, since many crop varieties were no longer cultivated because of the exodus from rural areas. At a later stage, the secondary sector, the food industry, became involved, as did tourism thereafter. Finally, the net spread out into the area of innovation, research and universities, the last sector to join being cultural. This made the changes into a movement, since in involved all these different participants (Rodríguez 2019).

Fig. 3.

The Basque-country gastronomic ecosystem.

Source: own compilation

Whilst this agricultural and gastronomic process has been shaped primarily by physical and sensory interactions in society, there has also been an emergence of digital co-creation of value. This can comprise operators providing on-line gastronomic tourism services, such as is offered by atasteofspain.com. It may include worldwide digital participants paying particular attention to the phenomenon of gastronomy in Spain, like the “Spain: an Open Kitchen”, digital platform gastronomy by Google, achieving value co-creation through dissemination of information and knowledge. For their part, C2C interactions also lead to applications, such as elkargest, which is intended to aid in the management of dining societies or txokos, and was designed through the collaboration of members. Tourists contribute to gastronomic co-creation as well, by talking about their culinary experiences through sharing information in the shape of photographs and comments on social networks. For its part, the San Sebastian International Film Festival, in addition to having a section for food films, usually invites cinema stars attending to eat in the best restaurants in the city. These celebrities share this gastronomic attraction through their social networks, and thus become influential C2C opinion shapers.

Discussion and conclusions

Marketing has shifted from relationships conceptualized as being dyadic links between supply organizations and customers, towards a better understanding of the dynamic processes of value co-creation between multiple socioeconomic actors. These forge service ecosystems of complex human interactions within a new service logic in their institutional frameworks.

Designations of origin should go beyond mere accreditation schemes and provenance labels, and should not merely seek product quality, whether in foods or drinks. They should also generate an ethical, environmental and moral narrative of the common good, through a creative gastronomic service that provides an alternative to industrial mass production. This is especially relevant today, as healthy and environmentally responsible lifestyles have become increasingly popular, spurring movements such as the “Slow Food” trend (Petrini 2003; Sassatelli and Davolio 2010), which strives to preserve a rich heritage of traditional cuisine and local production of healthy food. At the same time, there is an increase in tourism seeking new experiences to enjoy using various senses in scenic landscapes (Richards 2015).

Consequently, nostalgic ideologies aimed at reviving traditional recipes or dishes should be compatible and combined with exploring dynamic visions of regional revitalization through a creative agro-food service in which small-scale, high-quality craft gastronomic production is allied with eco-agro-tourism experiences of authenticity, and economic progress co-exists with values of environmental harmony and animal welfare. Such an approach permits the creation of gastronomic ecosystems such as the Basque Gastronomic Ecosystem, which explore new craft and gastronomic creativity.

Basque cooks have been key actors to the creation of a model of gastronomy that starts from an agro-food tradition and re-invents this heritage, converting chefs and their cuisine into a prestige place brand that attracts tourists and lovers of fine dining. This spirit has taken institutional form in a small, hilly region between the Bay of Biscay, a part of the Atlantic Ocean, and the foothills of the Pyrenean Mountains, even though it lacks any massive agricultural output or extensive cattle farms. The Basque Country became an industrial and financial powerhouse at the end of the nineteenth century. However, it has rediscovered its rural hinterland in a balanced way through this process, thus revitalizing the production of high-quality, sustainable, local foodstuffs. This Basque gastronomic co-creation brings together the rural context of smallholders, fishermen, or farmers, clearly service providers, and the urban context of cities, with their circles of social interaction and events, where service users are largely concentrated. This permits the identification of sub-systems within larger systems (Ostrom 2010), within an integrated service logic with multiple many-to-many interactions (Gummesson 2006) going to shape a sensory experience of destination brand (Rodrigues et al. 2019). As Suntikul (2019) argues, discussing the gastrodiplomacy context, it is actually instantiated in countless individual interactions between people and those individual hearts and minds are engaged through senses and palettes in a myriad of social and cultural encounters.

This process is based on an identity that is local and Basque, but also the whole Spain as a country of traditional cuisine and avant-garde gastronomy, and in general, European Mediterranean, strongly identified with gastronomy as a social interaction between individuals. Multiple public and private actors have played a part, and various types of consumer have been attracted, such as devotees of gastronomy, students, visitors and tourists motivated by a wish to expand their range of culinary experiences. In this way, a multi-actor food destination brand has been co-created, with an image and a reputation inspired by place cultural identity.

New, creative agro-food co-creation processes are emerging in different contexts relevant to regional and local development, whether the perspective is global (Jennings et al. 2015), European (Croce and Perri 2010; Cavicchi and Stancova 2016), Asian (Zhang 2015), Latin American (Dubbeling et al. 2017), or North American (Telfer 2001). In general, this research provides evidence for a mind-set of multi-actor systems and organization networks, linking country, region and city, production and tourism; there are also widespread underlying strong cultural identifications and territorial marketing or branding. Food and gastronomy based destination branding can serve to create an umbrella for small businesses and craft production. Although explanatory, the case studied in this piece of research may be of use as a reference for emerging destinations worldwide, helping also to enrich cultural dialogue on the planet and generate value and social progress in harmony with the natural environment.

The Covid-19 virus pandemic has brought with it a major crisis in the world economy, with serious consequences for gastronomy as well, which requires the rethinking of models of gastronomic co-creation. Whilst food and agriculture suppliers have played a key part in maintaining the flow of staples, the implications for restaurants and bars will depend on recuperating confidence in health and safety. On these lines, the Basque Culinary Center and the Euro-Toques European network of chefs are exploring solutions for food safety, bringing together B2B skills and knowledge. It is likely that because of close vicinity and social custom, the local public will gradually get back to the forms of consumption they had prior to the crisis. There is a question mark over the future return of tourists, especially those from other countries, and in particular from outside Europe. The required spatial distancing deals a blow to all social interactions. Implications are thus visible for a paradigm shift in tourism (Zenker and Kock 2020). This is likely to witness tendencies that had already begun to emerge, but which this crisis may accelerate, looking for sustainable authentic culinary experiences, without the stridencies of artificial luxury upon which too high a value was probably set in the past. To this end, there is a need for socio-economic governance that will protect and preserve the natural ecosystems on whose viability and biodiversity human health and well-being depend (Jarauta 2020), as does healthy nourishment.

This paper is no without limitations. The case study is based on authors’ many years observations and collection of available information. The attempt was foremost to map the agri-food and gastronomical interactions in the Basque region. Service Dominant Logic is the optimal conceptual-theoretical framework to analyse multiactor value co-creation. Nevertheless, the implications for place branding can be further explored. It needs however to be tested on real organism. Possible options include extensive field study and direct interviews with actors identified. Comparative studies could also be conducted to explore further insights on how particular ecosystems are framed—top-down—by broader institutional logics and socio-cultural milieux, and how key actors contribute to shape—bottom-up—institutional arrangements.

Biographies

Norberto Muñiz-Martínez,

Professor of Marketing at the University of Leon (Spain). Master Science of Transport & Distribution Management, University of Central England (Birmingham, England); Diploma in European Union and Foreign Trade by the Polytechnic University of Madrid (Spain). Has published papers in academic journals and books; Academic research and teachings at universities and institutions from Europe, the Americas and Asia. He has taught courses on new trends in tourism in a number of cities of Mexico and Colombia; and doctoral courses in Brazil and Venezuela. Visiting professor at the Asia-Europe Institute, University of Malaya (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia); and Universidad de Medellín (Colombia); and cooperating with Stockholm University Business School (Sweden). Areas of research: city marketing & place branding, strategic marketing and international retailing, new trends on tourism (eco-tourism and adventure travelling), and Service-dominant Logic.

Magdalena Florek,

PhD is Associate Professor at the Poznan University of Economics and Business (Poland). She is co-founder and Member of the Board of International Place Branding Association, co-founder and Member of the Board of Best Place – the European Place Marketing Institute. Senior Fellow at the Institute of Place Management. Scholarship participant of Fulbright Foundation at Northwestern University and Kellogg School of Management, USA and CICOPS scholarship at University of Pavia, Italy. In 2006/2007 senior lecturer at Marketing Department, University of Otago. Recently she published in Cities, Public Administration Review, Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, Journal of Place Management and Development. Areas of research: place branding, place brand identity, place brand effectiveness, place brand equity, place brand experience, food and gastronomy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Norberto Muñiz-Martinez, Email: nmunm@unileon.es.

Magdalena Florek, Email: magdalena.florek@ue.poznan.pl.

References

- Akaka MA, Vargo SL. Extending the context of service: From encounters to ecosystems. Journal of Services Marketing. 2015;29(6/7):453–462. doi: 10.1108/JSM-03-2015-0126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander MJ, Jaakkola E, Hollebeek LD. Zooming out: Actor engagement beyond the dyadic. Journal of Service Management. 2018;28(3):333–351. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-08-2016-0237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andéhn, M., and P.O. Berg. 2011. Place of origin effects–From nations to cities: A conceptual framework based on a literature review. In 2nd International Place Branding Conference, Bogotá, pp. 1–24.

- Andéhn M, Decosta JNPLE. Re-imagining the country-of-origin effect: A promulgation approach. Journal of Product & Brand Management. 2018;27(7):884–896. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-11-2017-1666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barile S, Lusch R, Reynoso J, Saviano M, Spohrer J. Systems, networks, and ecosystems in service research. Journal of Service Management. 2016;27(4):652–674. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-09-2015-0268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berg PO, Sevón G. Food-branding places – A sensory perspective. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy. 2014;10(4):289–304. doi: 10.1057/pb.2014.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bessière J. Local development and heritage: Traditional food and cuisine as tourist attractions in rural areas. Sociologia Ruralis. 1998;38(1):21–34. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beverland M. The ‘real thing’: Branding authenticity in the luxury wine trade. Journal of Business Research. 2006;59(2):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitner MJ. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing. 1992;56(2):57–71. doi: 10.1177/002224299205600205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boisen M, Terlouw K, Groote P, Couwenberg O. Reframing place promotion, place marketing, and place branding - moving beyond conceptual confusion. Cities. 2018;80:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2017.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen RL, Cox LJ, Fox M. The interface between tourism and agriculture. Journal of Tourism Studies. 1991;2(2):43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brundtland GH, Khalid M, Agnelli S, Al-Athel S, Chidzero BJNY. Our common future. New York: Oxford University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Callon M. Actor-network theory—the market test. The Sociological Review. 1999;47(S1):181–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.1999.tb03488.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caple, S., and M. Thyne. 2014. The concept of terroir: The elusive cultural element as defined by the Central Otago Wine Region. Academy of Wine Business.

- Capra F, Luisi PL. The systems view of life: A unifying vision. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, A., and K.C. Stancova. 2016. Food and gastronomy as elements of regional innovation strategies. Institute for Prospective and Technological Studies, Joint Research Centre, Sevilla.

- Chandler JD, Vargo SL. Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory. 2011;11(1):35–49. doi: 10.1177/1470593110393713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charters S, Spielmann N, Babin BJ. The nature and value of terroir products. European Journal of Marketing. 2017;51(4):748–771. doi: 10.1108/EJM-06-2015-0330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cilliers P. Complexity and postmodernism: Understanding complex systems. London: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Comunian R. Rethinking the creative city: The role of complexity, networks and interactions in the urban creative economy. Urban Studies. 2011;48(6):1157–1179. doi: 10.1177/0042098010370626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croce E, Perri G. Food and wine tourism: Integrating food, travel and territory. Wallingford: Cabi; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- de Salvo P, Hernández Mogollón JM, Di Clemente E, Calzati V. Territory, tourism and local products. The extra virgin oil's enhancement and promotion: A benchmarking Italy-Spain. Tourism and Hospitality Management. 2013;19(1):23–34. doi: 10.20867/thm.19.1.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnie K. Country-of-origin 1965–2004: A literature review. Journal of Customer Behaviour. 2004;3(2):165–213. doi: 10.1362/1475392041829537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbeling M, Santini G, Renting H, Taguchi M, Lançon L, Zuluaga J, Andino V. Assessing and planning Sustainable City region food systems: Insights from two Latin American cities. Sustainability. 2017;9(8):1455. doi: 10.3390/su9081455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du Rand GE, Heath E. Towards a framework for food tourism as an element of destination marketing. Current Issues in Tourism. 2006;9(3):206–234. doi: 10.2167/cit/226.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrer JA, Woratschek H, Germelmann CC, Brodie RJ. Dynamics and drivers of customer engagement: Within the dyad and beyond. Journal of Service Management. 2018;29(3):443–467. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-08-2016-0236. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrer JA, Conduit J, Plewa C, Li LP, Jaakkola E, Alexander M. Market shaping dynamics: Interplay of actor engagement and institutional work. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing. 2020;35(9):1425–1439. doi: 10.1108/JBIM-03-2019-0131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisk RP, Patrício L, Rosenbaum MS, Massiah C. An expanded servicescape perspective. Journal of Service Management. 2011;22(4):471–490. doi: 10.1108/09564231111155088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freire JR, Gertner RK. The relevance of food for the development of a destination brand. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy. 2021;17(2):193–204. doi: 10.1057/s41254-020-00164-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frochot I. An analysis of regional positioning and its associated food images in French tourism regional brochures. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2003;14(3–4):77–96. doi: 10.1300/J073v14n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frow P, Payne A. Value cocreation: An ecosystem perspective Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage; 2018. pp. 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman D. Agro-food studies in the ‘age of ecology’: Nature, corporeality, bio-politics. Sociologia Ruralis. 1999;39(1):17–38. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson E. Many-to-many marketing as grand theory. The service-dominant logic of marketing: Dialog, debate, and directions. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe; 2006. pp. 339–353. [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson E. Case theory in business and management: Reinventing case study research. Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gummesson E, Lusch RF, Vargo SL. Transitioning from service management to service-dominant logic; Observations and recommendations. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences. 2010;2(1):8–22. doi: 10.1108/17566691011026577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CM, Sharples L. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste in Food tourism around the world. Development Management and Markets. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager AM. A typology of gastronomy tourism. Tourism and gasronomy, chapter 2. London: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton JP, Stevens A. City branding and stakeholder engagement. In: Dinnie K, editor. City branding: Theory and cases. Basingstoke: Palgrave-McMillan; 2010. pp. 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ilbery B, Morris C, Buller H, Maye D, Kneafsey M. Product, process and place an examination of food marketing and labelling schemes in Europe and North America. European Urban and Regional Studies. 2005;12(2):116–132. doi: 10.1177/0969776405048499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarauta, F. 2020. La rebelión de la Naturaleza, 8 Jun. https://elpais.com/opinion/2020-06-07/la-rebelion-de-la-naturaleza.html.

- Jennings S, Cottee J, Curtis T, Miller S. Food in an urbanised world: The role of city region food systems. Urban Agriculture Magazine. 2015;29:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis M. From necessary evil to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development. 2012;5(1):7–19. doi: 10.1108/17538331211209013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaratzis M, Hatch MJ. The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Marketing Theory. 2013;13(1):69–86. doi: 10.1177/1470593112467268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Latour B. Reassembling the social: An introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KH, Scott N. Food tourism reviewed using the paradigm funnel approach. Journal of Culinary Science & Technology. 2015;13(2):95–115. doi: 10.1080/15428052.2014.952480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lockie S, Kitto S. Beyond the farm gate: Production-consumption networks and agri-food research. Sociologia Ruralis. 2000;40(1):3–19. doi: 10.1111/1467-9523.00128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lusch RF, Vargo SL. Competing through service: Insights from service-dominant logic. Journal of Retailing. 2007;83(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jretai.2006.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lusch RL, Vargo SL. Service dominant logic: Perspectives, possibilities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maglio P, Spohrer J. Fundamentals of service science. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2008;36(1):18–20. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0058-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, S., M. Hand, M. Da Pra, S. Pollack, K. Ralston, T. Smith, S. Vogel, S. Clark, L. Lohr, and L. Low. 2010. Local Food Systems Concepts, Impacts, and Issues; Economic Research Report 97; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington DC, USA.

- McKitterick L, Quinn B, McAdam R, Dunn A. Innovation networks and the institutional actor-producer relationship in rural areas: The context of artisan food production. Journal of Rural Studies. 2016;48:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montanari M. Food is culture. Columbia University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz-Martinez N. Towards a network place branding through multiple stakeholders and based on cultural identities; the case of “The Coffee Cultural Landscape” in Colombia. Journal of Place Management and Development. 2016;9(1):73–90. doi: 10.1108/JPMD-11-2015-0052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch J, Miele M. Culinary networks and cultural connections: A conventions perspective. The Blackwell Cultural Economy Reader. 2004 doi: 10.1002/9780470774274.ch13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Normann R. Reframing business: When the map changes the landscape. New York: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Okumus B, Cetin G. Marketing Istanbul as a culinary destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. 2018;9:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Transnational Corporations Review. 2010;2(2):1–12. doi: 10.1080/19186444.2010.11658229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrini C. Slow food: The case for taste. New York: Columbia University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza B, Tironi M, Haarich SN. Bilbao's art scene and the “Guggenheim effect” revisited. European Planning Studies. 2009;17(11):1711–1729. doi: 10.1080/09654310903230806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rachão, S.A.S., Z. Breda, C. Fernandes, and V. Joukes. 2020. Food-and-wine experiences towards co-creation in tourism. Tourism Review.

- Rao H, Monin P, Durand R. Institutional change in Toque Ville: Nouvelle cuisine as an identity movement in French gastronomy. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108(4):795–843. doi: 10.1086/367917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao H, Giorgi S. Code breaking: How entrepreneurs exploit cultural logics to generate institutional change. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2006;27:269–304. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27007-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi C. Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability. 2017;9(10):1748. doi: 10.3390/su9101748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richards G. Evolving gastronomic experiences: From food to foodies to foodscapes. Journal of Gastronomy and Tourism. 2015;1(1):5–17. doi: 10.3727/216929715X14298190828796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockower, P. 2014. The state of gastrodiplomacy. Public Diplomacy Magazine, 11. Winter.

- Rodrigues C, Skinner H, Dennis C, Melewar TC. Towards a theoretical framework on sensorial place brand identity. Journal of Place Management and Development. 2019;13(3):273–295. doi: 10.1108/JPMD-11-2018-0087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, J. 2019. El poder de la cocina vasca. El País Semanal, Mayo 24. https://elpais.com/elpais/2014/07/09/eps/1404857157_140485.html.

- Sánchez-Cañizares SM, López-Guzmán T. Gastronomy as a tourism resource: Profile of the culinary tourist. Current Issues in Tourism. 2012;15(3):229–245. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2011.589895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sassatelli R, Davolio F. Consumption, pleasure and politics: Slow food and the politico-aesthetic problematization of food. Journal of Consumer Culture. 2010;10(2):202–232. doi: 10.1177/1469540510364591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney M. Going beyond the product. The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialogue, Debate, and Directions. 2006;15:365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Schau HJ, Muñiz AM, Jr, Arnould EJ. How brand community practices create value. Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(5):30–51. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.5.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sims R. Food, place and authenticity: Local food and the sustainable tourism experience. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2009;17(3):321–336. doi: 10.1080/09669580802359293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storbacka K, Brodie RJ, Böhmann T, Maglio PP, Nenonen S. Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation. Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(8):3008–3017. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Warnaby G. Rethinking place branding from a practice perspective: Working with stakeholders. In: Kavaratzis M, Warnaby G, Ashworth GJ, editors. Rethinking place branding: Comprehensive brand development for cities ad regions. Heidelberg: Springer; 2015. pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Suntikul W. Gastrodiplomacy in tourism. Current Issues in Tourism. 2019;22(9):1076–1094. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2017.1363723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer DJ, Wall G. Linkages between tourism and food production. Annals of Tourism Research. 1996;23(3):635–653. doi: 10.1016/0160-7383(95)00087-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telfer DJ. Strategic alliances along the Niagara wine route. Tourism Management. 2001;22(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00033-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M. The Institutional logics perspective: A new approach to culture, Structure, and Process. Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo SL, Akaka MA. Value cocreation and service systems (re)formation: A service ecosystems view. Service Science. 2012;4(3):207–217. doi: 10.1287/serv.1120.0019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vargo SL, Lusch RF. Why “service”? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2008;36(1):25–38. doi: 10.1007/s11747-007-0068-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vargo SL, Lusch RF. Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2016;44(1):5–23. doi: 10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecandelaere, E., C. Teyssier, D. Barjolle, P. Jeanneaux, S. Fournier, and O. Beucherie. 2018. Strengthening sustainable food systems through geographical indications: An analysis of economic impacts. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

- Wiskerke JS. On places lost and places regained: Reflections on the alternative food geography and sustainable regional development. International Planning Studies. 2009;14(4):369–387. doi: 10.1080/13563471003642803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zenker S, Kock F. The coronavirus pandemic: A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Management. 2020;81:104164. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. The food of the worlds: Mapping and comparing contemporary gastrodiplomacy campaigns. International Journal of Communication. 2015;9(24):568–591. [Google Scholar]