Abstract

The birth and adult development of 'Dolly' the sheep, the first mammal produced by the transfer of a terminally differentiated cell nucleus into an egg, provided unequivocal evidence of nuclear equivalence among somatic cells. This ground-breaking experiment challenged a long-standing dogma of irreversible cellular differentiation that prevailed for over a century and enabled the development of methodologies for reversal of differentiation of somatic cells, also known as nuclear reprogramming. Thanks to this new paradigm, novel alternatives for regenerative medicine in humans, improved animal breeding in domestic animals and approaches to species conservation through reproductive methodologies have emerged. Combined with the incorporation of new tools for genetic modification, these novel techniques promise to (i) transform and accelerate our understanding of genetic diseases and the development of targeted therapies through creation of tailored animal models, (ii) provide safe animal cells, tissues and organs for xenotransplantation, (iii) contribute to the preservation of endangered species, and (iv) improve global food security whilst reducing the environmental impact of animal production. This review discusses recent advances that build on the conceptual legacy of nuclear transfer and – when combined with gene editing – will have transformative potential for medicine, biodiversity and sustainable agriculture. We conclude that the potential of these technologies depends on further fundamental and translational research directed at improving the efficiency and safety of these methods.

What did Dolly teach us?

The germ-plasm theory by August Weismann proposed that cells of a developing organism lose developmental plasticity during differentiation (Weismann et al. 1889). Observations in the roundworm Parascaris equorum made by Theodor Boveri, showing chromosome diminution in the somatic compartment whilst a full chromosome set was retained in the germline, contributed to Weismann’s concept. Hans Spemann proposed that transferring the nucleus of a cell into an egg would be a 'fantastical experiment' that would put this idea to the test (Spemann 1938). Early experimental attempts in amphibians supported this idea, as embryonic development failed after the nuclear transfer of gastrula-derived somatic cells into oocytes (King & Briggs 1955). Furthermore, when primordial germ cells (PGCs) from the same stages were used as nuclear donors, normal tadpoles developed, implying that developmental plasticity was restricted in cells adopting a somatic identity (Smith 1965). However, subsequent work by using more advanced developmental stages, such as embryonic gut epithelial cells, resulted in the development of normal adult frogs after the nuclear transfer (NT). Although the efficiency was very low (~1%), this experiment offered the first evidence that the genetic content of differentiated cells was equivalent to that of an undifferentiated blastomere (Gurdon & Uehlinger 1966). However, adult frogs were never obtained after NT with adult cells, thus a demonstration of complete reprogramming of an adult somatic cell remained unanswered for another three decades. A report of four cloned cattle made from NT embryos reconstructed with cultured inner cell mass (ICM) cells suggested that partially differentiated donor cells supported full-term development in mammals (Sims & First 1994). The year 1996 saw the culmination of extensive efforts by many groups over previous decades in overcoming the technical challenges of performing NT in mammals. For the first time, cultured cells from established cell lines from the embryonic disc of a sheep embryo were successfully used as nuclear donors. These experiments resulted in the birth of two lambs, Megan and Morag, who grew to fertile adults (Campbell et al. 1996b). Following this experiment, the team used cells isolated from the mammary gland of a 6-year-old Finn Dorset sheep and performed 277 NT experiments, from which one lamb, Dolly, was born (Wilmut et al. 1997). A key insight for the success of these experiments was the understanding of the critical need for cell-cycle coordination between the donor cell and the recipient oocyte (Campbell & Alberio 2003). Previous work by Campbell and colleagues had established the importance of using cells in the non-replicative phase of the cell cycle for NT into metaphase II oocytes (Campbell et al. 1996a). This was achieved very ingeniously via the 'starvation' of cells for several days, in order to slow down cell-cycle progression and enrich for cells in G0. As a result, reconstructed embryos had normal ploidy. This was in contrast to embryonic blastomeres, which have a long S-phase and undergo DNA damage after transfer into an MII oocyte (Campbell et al. 1993). DNA damage contributes to widespread chromosomal abnormalities, consistent with those reported in early studies in amphibians.

The biological significance of Dolly the sheep, the first cloned mammal by using an adult somatic cell, was far-reaching. First, it answered the long-standing question of genetic/cellular equivalence among cells in the adult organism, which had occupied the minds of scientists for over a century. Secondly, it represented a new dawn for biotechnological applications in medicine and agriculture. Importantly, NT carried out under optimized conditions can erase epigenetic memory of somatic cells enabling multiple rounds of re-cloning without loss of developmental potential (Wakayama et al. 2013), emphasizing the powerful reprogramming capacity of oocytes (Alberio et al. 2006, Halley-Stott et al. 2013). Indeed, the physiological parameters of 6-year-old Dolly clones were equivalent to age-matched control animals, which indicates that NT does not have long-term detrimental effects on aging (Sinclair et al. 2016). Thus, although the overall efficiency of NT remains low, the animals that develop full-term can be clinically healthy and fertile.

Genetic modification in livestock

Genetic modification of animals has primarily relied on the genetic modification of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESC) and the generation of chimeric founders that are bred to homozygosity (Doetschman et al. 1987, Thomas & Capecchi 1987). Mice have a short intergenerational interval and stem cell technologies have been available since 1981 (Evans & Kaufman 1981, Martin 1981). Hitherto, these methods have not been adopted in livestock because germline competent ESC were not available. However, two recent reports suggest that this may no longer be a limitation. They demonstrated two novel sources of embryonic stem cells derived from pig and horse pre-implantation embryos capable to robustly generate PGCs in vitro and can contribute to chimeric foetuses (Gao et al. 2019, Yu et al. 2020). The authors indicate that this technology can also work in other species, which would offer exciting opportunities for genetic engineering (GE) in livestock species. However, demonstration of efficient germline contribution in chimeric offspring is still needed before the broad use of livestock stem cells for GE can be realized. Thus far, however, NT has been a valuable alternative strategy for the generation of GE livestock. It has been used for multiple purposes, such as the generation of animal models of disease, the development of genetically multi-modified organ donor pigs for xenotransplantation, the production of nutraceuticals, preservation of endangered species, and as a platform technology for enhancing livestock genetic selection. Examples of these applications and some of the challenges and future directions are presented in the following sections.

Tailored large animal models for human diseases

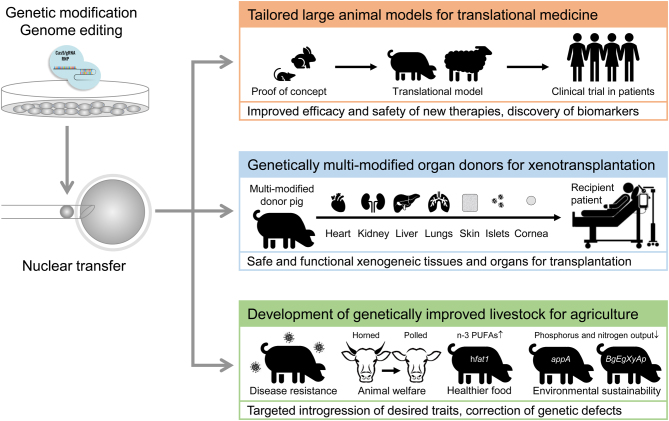

Livestock species share many anatomical and physiological characteristics with humans, such as large body size, similar metabolism and long lifespan, which are desirable when modelling human development and studying disease. Furthermore, livestock species are mostly outbred, making phenotypic observations more relevant to humans (Fig. 1). Among livestock, the pig stands out as the species of choice for human disease modelling due to similarities in organ anatomy, size and physiology. Genetically engineered pig models of cardiovascular disease (Schneider et al. 2020), diabetes (Renner et al. 2010, 2020), cystic fibrosis (Rogers et al. 2008, Bartlett et al. 2016, Caballero et al. 2021), several types of cancer (Perleberg et al. 2018), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) (Klymiuk et al. 2013, Moretti et al. 2020) and neurodegenerative disorders (such as Huntington’s disease and spinal muscular atrophy) have shown to closely recapitulate the physiopathology of these human diseases (Yang et al. 2010, Baxa et al. 2013, Holm et al. 2016). Importantly, these models are currently being used as platforms for developing new treatments and diagnostic tools (Renner et al. 2016, Regensburger et al. 2019, Moretti et al. 2020).

Figure 1.

Nuclear transfer using genetically modified cells as technological pipeline for the generation of large animal models for translational medicine, organ donor pigs for xenotransplantation, and new developments for sustainable animal agriculture. PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; hfat1, humanized version of the C. elegans fat1 desaturase gene; app, expression cassette for microbial phytase; BgEgXyA, polycistronic expression cassette for beta-glucanase, xylanase, and phytase.

Notably, all these models have been generated via NT by using genetically modified somatic cells. The creation of gene-targeted animals by using somatic cells is very laborious, requires intensive cell screening, multiple rounds of NT, and results in only low numbers of viable healthy offspring, which explains the relatively small numbers of animals generated so far. However, the development of gene-editing techniques by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system promises to drastically increase the efficacy of gene modification in somatic cells as well as directly in zygotes, which would remove the need for NT. For example, a new DMD pig model that displayed robust disease phenotype has been created by zygotic injection of Cas9 mRNA and guide RNA (Yu et al. 2016). However, DNA repair following double-strand breaks (DSB) caused by CRISPR endonucleases in zygotes is primarily driven by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ), which results in a high proportion of mosaic embryos. One way to reduce mosaicism has been to optimize the injection of the Cas9/gRNA complex during the first few hours (~5 h in pig and ~10 h in bovine), before the onset of the S-phase in the zygote, greatly reducing mosaicism (Park et al. 2017, Lamas-Toranzo et al. 2019). Another key aim of gene editing is the generation of a targeted knock-in via homologous recombination (HR). Since homology-directed repair (HDR) is not the preferred mechanism for DSB repair, methods that promote this process are needed. Complementation of Cas9/gRNA complex with RAD18, a component of the post-replicative repair pathway, increases HDR in cell lines, however, no data exist for embryos (Nambiar et al. 2019). The use of chemical compounds promoting HDR in bovine embryos has shown promising results yielding >50% gene targeting (Lamas-Toranzo et al. 2020). The simplicity of zygotic injection represents a major technological advantage over NT for the generation of gene-targeted animals and may replace the need of the latter in the future. It is also possible that microinjection may become less critical as methods for delivering one or multiple ribonucleoprotein complexes by electroporation are becoming more efficient in livestock (Tanihara et al. 2016, Hirata et al. 2020). A note of caution, however, needs to be made with regards to the high frequency of whole- or segmental-chromosome loss determined after DSB caused by the on- and off-target Cas9 cleavage during the zygote gene editing (Zuccaro et al. 2020). These observations call for the use of alternative approaches that do not require DSB to convert a targeted DNA into a new desired sequence, such as base or prime editors (Anzalone et al. 2020). Recently, transgenic chickens and pigs expressing Cas9 were reported as new resources for genome editing in livestock (Rieblinger et al. 2021).

Genetically multi-modified donor pigs for xenotransplantation

The 'opt-out' system introduced as part of the changes to organ donation law in several countries was supposed to alleviate the waiting lists for organ transplantation. However, data from the UK shows that demand for organ transplants is growing at 1% per year, and the number of suitable donors is decreasing at a rate of 1–4% per annum. Reasons for the decline in available organs include older age of donors and obesity, both factors that contribute to adverse effects on transplant outcomes. The highest organ demand is for kidneys, pancreata, hearts and livers. The use of animal organs from livestock, such as pigs, offers a possible solution to this growing problem (Fig. 1). The pig has many advantages, including human-like size and physiology, broad availability and breeding characteristics (large litters and short reproductive cycles). Furthermore, pigs are amenable to advanced reproductive and genetic engineering platforms (reviewed in Kemter et al. 2020). Public acceptance for using pigs as organ sources is growing, although strict regulatory measures that ensure safe and ethically sustainable sourcing of organs are imperative (Kogel & Marckmann 2020). The technology has now reached a stage that offers hopes for clinical applications in the not-so-distant future.

Pig heart transplantation to non-human primates has been widely used over decades as a model system (Cooper et al. 2014). NT technology was used to produce multi-modified pigs devoid of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase (GGTA1), and expressing human complement regulatory protein CD46 and human thrombomodulin. Hearts from these triple-modified pigs survived for over 900 days after heterotopic abdominal transplantation in baboons (Mohiuddin et al. 2016). Remarkably, pig hearts with these genetic modifications showed consistent life-supporting function after orthotopic transplantation in baboons with survival times of up to 195 days (Langin et al. 2018, Reichart et al. 2020). Survival for a longer period was mainly limited by the continued growth of the pig hearts in the small chests of the recipient baboons. Inactivation of the growth hormone receptor gene (GHR) in the donor pigs is a potential strategy to overcome this problem (Hinrichs et al. 2021).

Besides the heart, multi-modified pigs (GGTA1-deficient/human CD55 transgenic) made by NT have been used for kidney transplantation in a baboon that survived for 136 days (Iwase et al. 2017a, Iwase et al. 2017b). Moreover, transplantation of similar kidneys into macaques resulted in more than 1-year survival (Kim et al. 2009). For liver and lung xenotransplantation, the survival is more limited, however, the best results were obtained by using multi-modified pigs. Multiple other genetic modifications have been proposed to overcome humoral and cellular rejection of xenotransplants, to prevent coagulation disorders and other physiological incompatibilities, and to reduce/eliminate the risk of transmission of porcine endogenous retroviruses (Table 1; reviewed in Kemter et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Genetic modifications of donor pigs of cells, tissues and organs for xenotransplantation.

| Aim | Genetic modification |

|---|---|

| Deletion of sugar moieties of pig cells with pre-formed recipients’ antibodies | Knockout of the GGTA1, CMAH, B4GALNT2 genes |

| Inhibition of complement activation | Transgenic expression of human complement regulatory proteins (hCD46, hCD55, hCD59) |

| Prevention of coagulation dysregulation | Transgenic expression of human THBD, EPCR, TFPI, ENTPD1, CD73 (NT5E) |

| Prevention of T-cell mediated rejection | Transgenic expression of human CTLA4-Ig, LEA29Y, PD-L1; knockout or knockdown of swine leukocyte antigens |

| Inhibition of natural killer cells | Transgenic expression of HLA-E/human β2-microglobulin |

| Inhibition of macrophages | Transgenic expression of human CD47 |

| Prevention of inflammation | Transgenic expression of human TNFAIP3 (A20), HO-1, soluble TNFRI-Fc |

| Reduction of the risk of transmission of porcine endogenous retroviruses (PERV) | Knockdown of PERV expression; genome-wide knockout of the PERV pol gene |

Recently, the combined use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology plus transposon-mediated transgenesis in somatic cells has been used to create NT-engineered pigs with multiple gene knockouts and human transgenes (Yue et al. 2020). The efficacy of these modifications was demonstrated in in vitro assays, but transplantation experiments in non-human primates still need to be performed. Newly created multi-modified pigs carrying eight human transgenes encoding for coagulation regulators, negative regulators of the immune response and complement system, plus the inactivation of three pig xeno-antigens were successfully used as donors of skin xenografts in Cynomolgus monkeys without the need of immunosuppressants for 25 days (Zou et al. 2020).

Thus, future milestones directed to reducing the size of the organs produced, compatible with humans, and increased tolerance through targeted gene modifications will pave the way to clinical assessment of these organs (Sykes & Sachs 2019, Reichart et al. 2020). The recent progress demonstrates the critical need for NT technologies for the generation of these donor animals for xenotransplantation that can now be enhanced by the incorporation of efficient gene-editing and -targeting technologies.

Another avenue that is being explored for autologous transplantation considers the creation of human organs in organogenesis-disabled pigs through interspecies chimerism. The proof of concept for this idea comes from a study showing the creation of a mouse with a rat pancreas following blastocyst complementation and interspecies chimerism (Kobayashi et al. 2010). Notably, in a reciprocal experiment, a mouse pancreas was created in a rat by blastocyst complementation. Isolated islets of Langerhans transplanted into a diabetic mouse restored normal glycaemia, demonstrating functional complementation (Yamaguchi et al. 2017). This experiment demonstrated the potential for creating functional organs using interspecies chimeras. As an alternative for human organogenesis, pigs and sheep are the desired host species. An initial study showed very limited contribution of human cells into pig chimeric foetuses following blastocyst complementation (Wu et al. 2017). The causes of the very limited chimerism are unclear, but they could be due to differences in the developmental stages represented by the stem cells and the host embryo (Mascetti & Pedersen 2016). The type of stem cell and the culture conditions can also determine the viability of the cells in interspecies chimeras (Fu et al. 2020, Aksoy et al. 2021). It is also noteworthy that the greater evolutionary divergence between pigs and humans (>90 million years) compared to that between mice and rats (<20 million years) renders this approach incompatible under these experimental conditions. However, a better understanding of the signalling pathways and pluripotency features operating in the early embryo could lead to developing better stage-matched complementation strategies. Comparative embryology using scRNASeq has revealed that conventional and naïve human cells are more closely matched to late pig blastocysts, suggesting that more advanced stages of pig development could be better hosts for human cells (Ramos-Ibeas et al. 2019).

The combination of strategies aiming at the 'humanization' of pig organs via (i) elimination of pig antigens, (ii) introduction of human immunomodulatory genes, and (iii) genetic ablation of pig organs followed by embryo complementation constitute avenues that are technically possible. Indeed, a recent study shows the generation of human–pig chimeric embryos using a combination of techniques. First, ablation of the ETV2 gene, a master regulator of haemato-endothelium, was performed in porcine somatic cells. ETV2 mutant embryos created by NT were then complemented with human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC). Remarkably, the embryos generated contained blood vessels made exclusively of human endothelial cells (Das et al. 2020). The colonization of pig embryos was facilitated by the overexpression of BCL2, an anti-apoptotic gene. Previous work showed that inhibition of BCL2 can overcome the staged-related barriers to colonization in chimeric embryos (Masaki et al. 2016). More recently, a new approach for increasing interspecies chimerism was reported, based on the creation of Igf1r mutant mouse embryos complemented with WT rat ESC (Nishimura et al. 2021). This resulted in the generation of neonatal mice having the extensive contribution of rat cells in diverse organs, predominantly those in which IGF signalling is very important, including the kidney, heart, lung and thymus. Although future studies should focus on the phenotypic analysis of such animals, this work shows the prospect of using pigs for creating organs containing autologous human vasculature, thus greatly reducing the chances of immune rejection.

The impact of gene editing in animal production and welfare

The challenges of improving sustainable animal production whilst meeting the increased demand for healthier and nutritious animal products by the growing world population demand the use of new approaches to enhance the quality and productivity of livestock (Fig. 1). One approach suggested to improve the health benefits of meat consumption is to modify the proportion of unsaturated fats. Since dietary interventions to feed animals with sources of such fats are not environmentally friendly, transgenic approaches could be used. Examples of cattle, sheep and pigs expressing the C. elegans fat1 desaturase gene in fibroblasts prior to NT have been reported (Lai et al. 2006, Wu et al. 2012, Zhang et al. 2013). These animals had a richer content in omega-3 fatty acids, making them a prime example of a nutraceutical produced by NT. Other examples include the generation of hypoallergenic milk through the abolition of β-lactoglobulin production in cows (Jabed et al. 2012), and lactoferrin and lysozyme-containing cow milk (Kaiser et al. 2017). However, current regulations for the consumption of products from genetically modified animals are very restrictive.

Another strategy for improving specific traits not reliant on transgenesis is to incorporate specific mutations that can alter animal phenotypes. For example, the naturally occurring mutation at the MSTN gene is the cause of the 'double muscle' phenotype in some cattle (Grobet et al. 1997, McPherron & Lee 1997) and sheep (Clop et al. 2006) breeds, resulting in 20% more muscle mass. These mutations were introduced not only into other sheep and cattle breeds (Proudfoot et al. 2015) but also into pigs (Wang et al. 2015a) and goats (Wang et al. 2015b) by gene editing via NT or zygotic injections. Gene editing offers an alternative means for the accelerated introduction of naturally occurring alleles, albeit in different species. From a regulatory and consumer perspective, the acceptability of such products may be less controversial.

Importantly, herd productivity is also dependant on the robust health status of the animals reared. Gene editing can be used to generate disease-resistant animals. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV)-resistant pigs were created following the mutation of CD163, which prevents viral infection (Whitworth et al. 2016, Burkard et al. 2017). Similarly, transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV)-resistant pigs were created by editing the gene for the putative viral receptor ANPEP(Whitworth et al. 2019). Other strategies include the use of gene introgressions to create disease-resistant pigs. The RELA gene from the warthog, naturally resistant to African swine fever, was introgressed into domestic pigs (Lillico et al. 2016). Although a delayed onset of infection was determined, this introgression did not confer complete protection against the clinical symptoms, suggesting that additional modifications may be needed (McCleary et al. 2020). Another recent study reports the use of a CRISPR/Cas9 nickase strategy combined with NT to generate cattle with a targeted insertion of a natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1 (NRAMP1) expression cassette making them resistant to tuberculosis (Gao et al. 2017).

Part of improving production systems will require changes in the ways in which animals are reared. A good example of a step towards improving welfare is the propagation of the POLLED genotype across cattle breeds. By using gene editing and NT, POLLED alleles were introgressed and resulted in the birth of homozygous polled bulls (Carlson et al. 2016), which after crossing with horned cows delivered hornless offspring (Young et al. 2020).

Probably the most important goal of future animal production is environmental sustainability. Genetic engineering was thus used to overcome inefficient feed digestion in pigs, which results in excessive release of phosphorus and nitrogen to the environment. Transgenic pigs expressing microbial phytase in the salivary glands had an increased ability to digest phosphorus from dietary phytate and showed a markedly reduced faecal phosphorus concentration (Golovan et al. 2001). Recently, this approach was extended to transgenic pigs expressing beta-glucanase, xylanase, and phytase in the salivary glands. As a consequence, digestion of non-starch polysaccharides and phytate was enhanced, faecal nitrogen and phosphorus outputs were reduced (23–45%), and growth rate (~25%) and feed conversion rate (12–15%) were significantly improved (Zhang et al. 2018).

These examples demonstrate that favourable traits (e.g. disease resistance and feed conversion efficiency) can be rapidly introduced to improve sustainable production, health and welfare of animal production systems.

Advanced animal breeding and genetic selection

The long generation intervals in domestic animals hinder the progress of genomic selection requiring novel approaches to accelerate the pace at which new animal phenotypes can be created. As discussed above, the combination of robust and safe gene/base-editing methods and reproductive techniques, such as in vitro fertilization and NT can drastically accelerate the rate of genetic gain. However, the bottleneck of meiosis remains. This critical step in the reproductive cycle of animals ensures genetic diversity, however, in breeding programmes, it represents a major hurdle due to the long time needed to generate mature gametes in livestock. Breeders and geneticists have been working on technological solutions to shorten this period for decades. A vision for utilizing in vitro systems for growing gametes as a means to reduce generation intervals, also known as 'velogenetics', was proposed in the early ’90s when genotype databases and assisted reproduction were beginning to be used (Georges & Massey 1991). More recently, these ideas have resurfaced as a result of developments in genetic selection, stem cell technologies and the possibilities of in vitro gamete production in domestic animals (Rexroad et al. 2019). In vitro breeding (IVB) was proposed as a platform combining the use of quantitative trait loci (QTL) datasets and reproductive techniques as a method of enhanced genetic selection (Goszczynski et al. 2019). This approach would yield a ten-fold increase in genetic selection without genetic manipulation. The use of gene/base-editing methods could further enhance the rate of genetic gain of this platform by multiplexing the incorporation of new alleles (Jenko et al. 2015).

However, this technology is contingent on a complete in vitro system for making gametes. Recent advances in our understanding of gamete development in large mammals are paving the way for the generation of mature gametes (Kobayashi et al. 2017). Remarkably, there are close similarities in the transcriptional programme between human, pig and cattle germline development (Soto & Ross 2021, Zhu et al. 2021), which offers advantages when it comes to translating findings from one species to another. This is particularly important because progress in human germ cell differentiation shows that mature oogonia can be generated, albeit at very low efficiency (Yamashiro et al. 2018). Detailed molecular understanding of the biology of germ cells has also enabled the creation of oocyte-like cells directly from mouse embryonic stem cells by the expression of eight specific transcription factors (Hamazaki et al. 2021). These oocyte-like cells were capable of chromosome segregation but failed to undergo normal meiosis. Nevertheless, these advances offer exciting opportunities for adapting some of these conditions for the generation of animal gametes from novel stem cells.

Considering the challenges of accomplishing meiosis in vitro, the technology of surrogate sires could serve as an alternative. The idea is to generate males that lack their own spermatogonia, but their testis can act as a developmental niche for spermatogonia from other males. Testis of NANOS2 KO males support allogeneic spermatogonial transplantation and full spermatogenesis (Ciccarelli et al. 2020). The use of this technology could not only significantly increase the genetic merit of sires used in breeding programs (Gottardo et al. 2019) but can also serve as a tool for the genetic preservation of endangered species.

Preservation of endangered species

Nuclear transfer offers an avenue for the rescue of endangered species, provided a compatible cytoplast can be obtained from closely related species. Some successes were reported with wild African cats and grey wolfs, but limited success was reported with an extinct subspecies of goat (Gomez et al. 2004, Kim et al. 2007, Folch et al. 2009). A critical aspect of this approach is the reliance on compatible cytoplasts. Importantly, a major breakthrough in the generation of synthetic cytoplasts from embryonic stem cells was recently reported (Hamazaki et al. 2021). Future experiments will determine whether this technology can be used as an alternative source of compatible cytoplasts suitable for nuclear transfer. This platform would offer a reproductive alternative for rescuing species such as the Northern White rhinoceros (Hildebrandt et al. 2018). In this case, in vitro fertilized embryos and embryonic stem cells have been produced from the last two female specimens of the species. The generation of gametes from these stem cells as well as the generation of cytoplasts would enable the propagation of these last remaining animals by both natural reproduction and nuclear transfer. Although a limited gene pool could represent an obstacle for expanding endangered species, the establishment of induced pluripotent stem cells from frozen tissues/blood could offer an alternative route for the generation of gametes that could be used for in vitro breeding.

Concluding remarks

In this review, we summarized the critical impact that nuclear transfer had in facilitating the generation of genetically modified animals over the past 25 years. The impact of this technology has undoubtedly been more significant in livestock species due to the lack of embryonic stem cells, the standard route of gene targeting in mice. Thus, gene modification of donor cells prior to NT has been the preferred avenue for creating genetically modified livestock. Although the technique remains quite labour intensive, significant progress has been made in the procedures resulting in better efficiency. New sources of livestock embryonic stem cells have been reported, suggesting that gene manipulation and chimera generation may be simplified in the future. However, the long generation interval of livestock species makes the process of breeding to homozygosity of chimeric animals a lengthy and expensive process compared to mice. In contrast, NT allows the instant generation of transgenic animals, suggesting that it will remain a valuable technology for years to come.

We have come a long way since this landmark experiment, with improved knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of cellular reprogramming and more efficient techniques of NT. We can look forward to the next 25 years in which NT, in combination with other modern gene manipulation technologies, can offer solutions to urgent biomedical needs, improve sustainable animal production and facilitate species conservation.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of this review.

Funding

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grant number BB/S000178/1) to R A and by the German Research Council (DFG; TRR127) and the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD; 82DZD00802) to E W.

Author contribution statement

RA and EW performed literature research and wrote the manuscript. EW prepared the figure and table. Both authors reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors apologize to authors whose work was not cited due to space limitations. RA states that writing this review brought back many memories of the excitement and the mystique that surrounded the Dolly the sheep experiment. Doubts were soon dispelled and a race to develop a better understanding of NT started in many labs around the world. The author having just started his PhD studies (RA), struggled to fully envision the impact of the discovery, but realized the magnitude of the findings for the understanding of cell plasticity. Only 2 years after starting as Chair for Molecular Animal Breeding and Biotechnology at LMU Munich (EW), he was incredibly lucky to have Valeri Zakhartchenko in the team who was among the first worldwide to establish NT in bovine. EW is also very grateful to Hiroshi Nagashima for sharing his porcine NT technology that was the basis of their pipeline of genetically modified pig models.

References

- Aksoy I, Rognard C, Moulin A, Marcy G, Masfaraud E, Wianny F, Cortay V, Bellemin-Menard A, Doerflinger N, Dirheimer Met al. 2021. Apoptosis, G1 phase stall, and premature differentiation account for low chimeric competence of human and rhesus monkey naive pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Reports 16 56–74. ( 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.12.004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberio R, Campbell KH, Johnson AD.2006. Reprogramming somatic cells into stem cells. Reproduction 132 709–720. ( 10.1530/rep.1.01077) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anzalone AV, Koblan LW, Liu DR.2020. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nature Biotechnology 38 824–844. ( 10.1038/s41587-020-0561-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett JA, Ramachandran S, Wohlford-Lenane CL, Barker CK, Pezzulo AA, Zabner J, Welsh MJ, Meyerholz DK, Stoltz DA, McCray Jr PB.2016. Newborn cystic fibrosis pigs have a blunted early response to an inflammatory stimulus. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 194 845–854. ( 10.1164/rccm.201510-2112OC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxa M, Hruska-Plochan M, Juhas S, Vodicka P, Pavlok A, Juhasova J, Miyanohara A, Nejime T, Klima J, Macakova Met al. 2013. A transgenic minipig model of Huntington’s disease. Journal of Huntington’s Disease 2 47–68. ( 10.3233/JHD-130001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkard C, Lillico SG, Reid E, Jackson B, Mileham AJ, Ait-Ali T, Whitelaw CB, Archibald AL.2017. Precision engineering for PRRSV resistance in pigs: macrophages from genome edited pigs lacking CD163 SRCR5 domain are fully resistant to both PRRSV genotypes while maintaining biological function. PLoS Pathogens 13 e1006206. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero I, Ringot-Destrez B, Si-Tahar M, Barbry P, Guillon A, Lantier I, Berri M, Chevaleyre C, Fleurot I, Barc Cet al. 2021. Evidence of early increased sialylation of airway mucins and defective mucociliary clearance in CFTR-deficient piglets. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 20 173–182. ( 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.09.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, Alberio R.2003. Reprogramming the genome: role of the cell cycle. Reproduction 61 477–494. ( 10.1530/biosciprocs.5.035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I.1993. Nuclear-cytoplasmic interactions during the first cell cycle of nuclear transfer reconstructed bovine embryos: implications for deoxyribonucleic acid replication and development. Biology of Reproduction 49 933–942. ( 10.1095/biolreprod49.5.933) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, Loi P, Otaegui PJ, Wilmut I.1996a. Cell cycle co-ordination in embryo cloning by nuclear transfer. Reviews of Reproduction 1 40–46. ( 10.1530/ror.0.0010040) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KH, McWhir J, Ritchie WA, Wilmut I.1996b. Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line. Nature 380 64–66. ( 10.1038/380064a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson DF, Lancto CA, Zang B, Kim ES, Walton M, Oldeschulte D, Seabury C, Sonstegard TS, Fahrenkrug SC.2016. Production of hornless dairy cattle from genome-edited cell lines. Nature Biotechnology 34 479–481. ( 10.1038/nbt.3560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli M, Giassetti MI, Miao D, Oatley MJ, Robbins C, Lopez-Biladeau B, Waqas MS, Tibary A, Whitelaw B, Lillico Set al. 2020. Donor-derived spermatogenesis following stem cell transplantation in sterile NANOS2 knockout males. PNAS 117 24195–24204. ( 10.1073/pnas.2010102117) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clop A, Marcq F, Takeda H, Pirottin D, Tordoir X, Bibe B, Bouix J, Caiment F, Elsen JM, Eychenne Fet al. 2006. A mutation creating a potential illegitimate microRNA target site in the myostatin gene affects muscularity in sheep. Nature Genetics 38 813–818. ( 10.1038/ng1810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DK, Satyananda V, Ekser B, van der Windt DJ, Hara H, Ezzelarab MB, Schuurman HJ.2014. Progress in pig-to-non-human primate transplantation models (1998–2013): a comprehensive review of the literature. Xenotransplantation 21 397–419. ( 10.1111/xen.12127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Gafni O, Maeng G, Singh BN, Rasmussen T, Pan X, Choi KD, Mickelson D, Gong Wet al. 2020. Generation of human endothelium in pig embryos deficient in ETV2. Nature Biotechnology 38 297–302. ( 10.1038/s41587-019-0373-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetschman T, Gregg RG, Maeda N, Hooper ML, Melton DW, Thompson S, Smithies O.1987. Targetted correction of a mutant HPRT gene in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature 330 576–578. ( 10.1038/330576a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH.1981. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature 292 154–156. ( 10.1038/292154a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Cocero MJ, Chesne P, Alabart JL, Dominguez V, Cognie Y, Roche A, Fernandez-Arias A, Marti JI, Sanchez Pet al. 2009. First birth of an animal from an extinct subspecies (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica) by cloning. Theriogenology 71 1026–1034. ( 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2008.11.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R, Yu D, Ren J, Li C, Wang J, Feng G, Wang X, Wan H, Li T, Wang Let al. 2020. Domesticated cynomolgus monkey embryonic stem cells allow the generation of neonatal interspecies chimeric pigs. Protein and Cell 11 97–107. ( 10.1007/s13238-019-00676-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Wu H, Wang Y, Liu X, Chen L, Li Q, Cui C, Liu X, Zhang J, Zhang Y.2017. Single Cas9 nickase induced generation of NRAMP1 knockin cattle with reduced off-target effects. Genome Biology 18 13. ( 10.1186/s13059-016-1144-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Nowak-Imialek M, Chen X, Chen D, Herrmann D, Ruan D, Chen ACH, Eckersley-Maslin MA, Ahmad S, Lee YLet al. 2019. Establishment of porcine and human expanded potential stem cells. Nature Cell Biology 21 687–699. ( 10.1038/s41556-019-0333-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georges M, Massey JM.1991. Velogenetics, or the synergistic use of marker assisted selection and germ-line manipulation. Theriogenology 35 151–159. ( 10.1016/0093-691X(9190154-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golovan SP, Meidinger RG, Ajakaiye A, Cottrill M, Wiederkehr MZ, Barney DJ, Plante C, Pollard JW, Fan MZ, Hayes MAet al. 2001. Pigs expressing salivary phytase produce low-phosphorus manure. Nature Biotechnology 19 741–745. ( 10.1038/90788) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MC, Pope CE, Giraldo A, Lyons LA, Harris RF, King AL, Cole A, Godke RA, Dresser BL.2004. Birth of African Wildcat cloned kittens born from domestic cats. Cloning and Stem Cells 6 247–258. ( 10.1089/clo.2004.6.247) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goszczynski DE, Cheng H, Demyda-Peyras S, Medrano JF, Wu J, Ross PJ.2019. In vitro breeding: application of embryonic stem cells to animal productiondagger. Biology of Reproduction 100 885–895. ( 10.1093/biolre/ioy256) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottardo P, Gorjanc G, Battagin M, Gaynor RC, Jenko J, Ros-Freixedes R, Bruce A Whitelaw C, Mileham AJ, Herring WO, Hickey JM.2019. A strategy to exploit surrogate sire technology in livestock breeding programs. G3 9 203–215. ( 10.1534/g3.118.200890) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobet L, Martin LJ, Poncelet D, Pirottin D, Brouwers B, Riquet J, Schoeberlein A, Dunner S, Menissier F, Massabanda Jet al. 1997. A deletion in the bovine myostatin gene causes the double-muscled phenotype in cattle. Nature Genetics 17 71–74. ( 10.1038/ng0997-71) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon JB, Uehlinger V.1966. ‘Fertile’ intestine nuclei. Nature 210 1240–1241. ( 10.1038/2101240a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halley-Stott RP, Pasque V, Gurdon JB.2013. Nuclear reprogramming. Development 140 2468–2471. ( 10.1242/dev.092049) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki N, Kyogoku H, Araki H, Miura F, Horikawa C, Hamada N, Shimamoto S, Hikabe O, Nakashima K, Kitajima TSet al. 2021. Reconstitution of the oocyte transcriptional network with transcription factors. Nature 589 264–269. ( 10.1038/s41586-020-3027-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt TB, Hermes R, Colleoni S, Diecke S, Holtze S, Renfree MB, Stejskal J, Hayashi K, Drukker M, Loi Pet al. 2018. Embryos and embryonic stem cells from the white rhinoceros. Nature Communications 9 2589. ( 10.1038/s41467-018-04959-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs A, Riedel EO, Klymiuk N, Blutke A, Kemter E, Langin M, Dahlhoff M, Kessler B, Kurome M, Zakhartchenko Vet al. 2021. Growth hormone receptor knockout to reduce the size of donor pigs for preclinical xenotransplantation studies. Xenotransplantation 28 e12664. ( 10.1111/xen.12664) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata M, Wittayarat M, Namula Z, Le QA, Lin Q, Nguyen NT, Takebayashi K, Sato Y, Tanihara F, Otoi T.2020. Evaluation of multiple gene targeting in porcine embryos by the CRISPR/Cas9 system using electroporation. Molecular Biology Reports 47 5073–5079. ( 10.1007/s11033-020-05576-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm IE, Alstrup AK, Luo Y.2016. Genetically modified pig models for neurodegenerative disorders. Journal of Pathology 238 267–287. ( 10.1002/path.4654) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase H, Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Li T, Zhang Z, Gao B, Liu H, Long C, Wang Y, Cassano Aet al. 2017a. Immunological and physiological observations in baboons with life-supporting genetically engineered pig kidney grafts. Xenotransplantation 24 e12293 ( 10.1111/xen.12293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwase H, Liu H, Schmelzer E, Ezzelarab M, Wijkstrom M, Hara H, Lee W, Singh J, Long C, Lagasse Eet al. 2017b. Transplantation of hepatocytes from genetically engineered pigs into baboons. Xenotransplantation 24 e12289. ( 10.1111/xen.12289) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabed A, Wagner S, McCracken J, Wells DN, Laible G.2012. Targeted microRNA expression in dairy cattle directs production of beta-lactoglobulin-free, high-casein milk. PNAS 109 16811–16816. ( 10.1073/pnas.1210057109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenko J, Gorjanc G, Cleveland MA, Varshney RK, Whitelaw CB, Woolliams JA, Hickey JM.2015. Potential of promotion of alleles by genome editing to improve quantitative traits in livestock breeding programs. Genetics, Selection, Evolution 47 55. ( 10.1186/s12711-015-0135-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser GG, Mucci NC, Gonzalez V, Sanchez L, Parron JA, Perez MD, Calvo M, Aller JF, Hozbor FA, Mutto AA.2017. Detection of recombinant human lactoferrin and lysozyme produced in a bitransgenic cow. Journal of Dairy Science 100 1605–1617. ( 10.3168/jds.2016-11173) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemter E, Schnieke A, Fischer K, Cowan PJ, Wolf E.2020. Xeno-organ donor pigs with multiple genetic modifications – the more the better? Current Opinion in Genetics and Development 64 60–65. ( 10.1016/j.gde.2020.05.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Jang G, Oh HJ, Yuda F, Kim HJ, Hwang WS, Hossein MS, Kim JJ, Shin NS, Kang SKet al. 2007. Endangered wolves cloned from adult somatic cells. Cloning and Stem Cells 9 130–137. ( 10.1089/clo.2006.0034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SC, Mathews DV, Breeden CP, Higginbotham LB, Ladowski J, Martens G, Stephenson A, Farris AB, Strobert EA, Jenkins J. et al. 2019. Long-term survival of pig-to-rhesus macaque renal xenografts is dependent on CD4 T cell depletion. American Journal of Transplantation 19 2174––2185.. ( 10.1111/ajt.15329) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King TJ, Briggs R.1955. Changes in the nuclei of differentiating gastrula cells, as demonstrated by nuclear transplantation. PNAS 41 321–325. ( 10.1073/pnas.41.5.321) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klymiuk N, Blutke A, Graf A, Krause S, Burkhardt K, Wuensch A, Krebs S, Kessler B, Zakhartchenko V, Kurome Met al. 2013. Dystrophin-deficient pigs provide new insights into the hierarchy of physiological derangements of dystrophic muscle. Human Molecular Genetics 22 4368–4382. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddt287) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Yamaguchi T, Hamanaka S, Kato-Itoh M, Yamazaki Y, Ibata M, Sato H, Lee YS, Usui J, Knisely ASet al. 2010. Generation of rat pancreas in mouse by interspecific blastocyst injection of pluripotent stem cells. Cell 142 787–799. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Zhang H, Tang WWC, Irie N, Withey S, Klisch D, Sybirna A, Dietmann S, Contreras DA, Webb Ret al. 2017. Principles of early human development and germ cell program from conserved model systems. Nature 546 416–420. ( 10.1038/nature22812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogel J, Marckmann G.2020. ‘Xenotransplantation challenges us as a society’: what well-informed citizens think about xenotransplantation. EMBO Reports 21 e50274. ( 10.15252/embr.202050274) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Kang JX, Li R, Wang J, Witt WT, Yong HY, Hao Y, Wax DM, Murphy CN, Rieke Aet al. 2006. Generation of cloned transgenic pigs rich in omega-3 fatty acids. Nature Biotechnology 24 435–436. ( 10.1038/nbt1198) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas-Toranzo I, Galiano-Cogolludo B, Cornudella-Ardiaca F, Cobos-Figueroa J, Ousinde O, Bermejo-Alvarez P.2019. Strategies to reduce genetic mosaicism following CRISPR-mediated genome edition in bovine embryos. Scientific Reports 9 14900. ( 10.1038/s41598-019-51366-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas-Toranzo I, Martínez-Moro A, O Callaghan E, Millán-Blanca G, Sánchez JM, Lonergan P, Bermejo-Álvarez P.2020. RS-1 enhances CRISPR-mediated targeted knock-in in bovine embryos. Molecular Reproduction and Development 87 542–549. ( 10.1002/mrd.23341) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langin M, Mayr T, Reichart B, Michel S, Buchholz S, Guethoff S, Dashkevich A, Baehr A, Egerer S, Bauer Aet al. 2018. Consistent success in life-supporting porcine cardiac xenotransplantation. Nature 564 430–433. ( 10.1038/s41586-018-0765-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillico SG, Proudfoot C, King TJ, Tan W, Zhang L, Mardjuki R, Paschon DE, Rebar EJ, Urnov FD, Mileham AJet al. 2016. Mammalian interspecies substitution of immune modulatory alleles by genome editing. Scientific Reports 6 21645. ( 10.1038/srep21645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR.1981. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. PNAS 78 7634–7638. ( 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki H, Kato-Itoh M, Takahashi Y, Umino A, Sato H, Ito K, Yanagida A, Nishimura T, Yamaguchi T, Hirabayashi Met al. 2016. Inhibition of apoptosis overcomes stage-related compatibility barriers to chimera formation in mouse embryos. Cell Stem Cell 19 587–592. ( 10.1016/j.stem.2016.10.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascetti VL, Pedersen RA.2016. Contributions of mammalian chimeras to pluripotent stem cell research. Cell Stem Cell 19 163–175. ( 10.1016/j.stem.2016.07.018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleary S, Strong R, McCarthy RR, Edwards JC, Howes EL, Stevens LM, Sanchez-Cordon PJ, Nunez A, Watson S, Mileham AJet al. 2020. Substitution of warthog NF-kappaB motifs into RELA of domestic pigs is not sufficient to confer resilience to African swine fever virus. Scientific Reports 10 8951. ( 10.1038/s41598-020-65808-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherron AC, Lee SJ.1997. Double muscling in cattle due to mutations in the myostatin gene. PNAS 94 12457–12461. ( 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12457) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohiuddin MM, Singh AK, Corcoran PC, Thomas Iii ML, Clark T, Lewis BG, Hoyt RF, Eckhaus M, Pierson Iii RN, Belli AJet al. 2016. Chimeric 2C10R4 anti-CD40 antibody therapy is critical for long-term survival of GTKO.hCD46.hTBM pig-to-primate cardiac xenograft. Nature Communications 7 11138. ( 10.1038/ncomms11138) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretti A, Fonteyne L, Giesert F, Hoppmann P, Meier AB, Bozoglu T, Baehr A, Schneider CM, Sinnecker D, Klett Ket al. 2020. Somatic gene editing ameliorates skeletal and cardiac muscle failure in pig and human models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature Medicine 26 207–214. ( 10.1038/s41591-019-0738-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar TS, Billon P, Diedenhofen G, Hayward SB, Taglialatela A, Cai K, Huang JW, Leuzzi G, Cuella-Martin R, Palacios Aet al. 2019. Stimulation of CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair by an engineered RAD18 variant. Nature Communications 10 3395. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-11105-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Suchy FP, Bhadury J, Igarashi KJ, Charlesworth CT, Nakauchi H.2021. Generation of functional organs using a cell-competitive niche in intra- and inter-species rodent chimeras. Cell Stem Cell 28 141–149.e3. ( 10.1016/j.stem.2020.11.019) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KE, Powell A, Sandmaier SE, Kim CM, Mileham A, Donovan DM, Telugu BP.2017. Targeted gene knock-in by CRISPR/Cas ribonucleoproteins in porcine zygotes. Scientific Reports 7 42458. ( 10.1038/srep42458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perleberg C, Kind A, Schnieke A.2018. Genetically engineered pigs as models for human disease. Disease Models and Mechanisms 11 dmm030783. ( 10.1242/dmm.030783) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot C, Carlson DF, Huddart R, Long CR, Pryor JH, King TJ, Lillico SG, Mileham AJ, McLaren DG, Whitelaw CBet al. 2015. Genome edited sheep and cattle. Transgenic Research 24 147–153. ( 10.1007/s11248-014-9832-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Ibeas P, Sang F, Zhu Q, Tang WWC, Withey S, Klisch D, Wood L, Loose M, Surani MA, Alberio R.2019. Pluripotency and X chromosome dynamics revealed in pig pre-gastrulating embryos by single cell analysis. Nature Communications 10 500. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-08387-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regensburger AP, Fonteyne LM, Jungert J, Wagner AL, Gerhalter T, Nagel AM, Heiss R, Flenkenthaler F, Qurashi M, Neurath MFet al. 2019. Detection of collagens by multispectral optoacoustic tomography as an imaging biomarker for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature Medicine 25 1905–1915. ( 10.1038/s41591-019-0669-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichart B, Langin M, Denner J, Schwinzer R, Cowan PJ, Wolf E.2020. Pathways to clinical cardiac xenotransplantation. Transplantation In press. ( 10.1097/TP.0000000000003588) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner S, Fehlings C, Herbach N, Hofmann A, von Waldthausen DC, Kessler B, Ulrichs K, Chodnevskaja I, Moskalenko V, Amselgruber Wet al. 2010. Glucose intolerance and reduced proliferation of pancreatic beta-cells in transgenic pigs with impaired glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide function. Diabetes 59 1228–1238. ( 10.2337/db09-0519) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner S, Blutke A, Streckel E, Wanke R, Wolf E.2016. Incretin actions and consequences of incretin-based therapies: lessons from complementary animal models. Journal of Pathology 238 345–358. ( 10.1002/path.4655) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner S, Blutke A, Clauss S, Deeg CA, Kemter E, Merkus D, Wanke R, Wolf E.2020. Porcine models for studying complications and organ crosstalk in diabetes mellitus. Cell and Tissue Research 380 341–378. ( 10.1007/s00441-019-03158-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rexroad C, Vallet J, Matukumalli LK, Reecy J, Bickhart D, Blackburn H, Boggess M, Cheng H, Clutter A, Cockett Net al. 2019. Genome to phenome: improving animal health, production, and well-being – a new USDA Blueprint for Animal Genome Research 2018–2027. Front Genet 10 327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieblinger B, Sid H, Duda D, Bozoglu T, Klinger R, Schlickenrieder A, Lengyel K, Flisikowski K, Flisikowska T, Simm Net al. 2021. Cas9-expressing chickens and pigs as resources for genome editing in livestock. PNAS 118 e2022562118. ( 10.1073/pnas.2022562118) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CS, Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Ostedgaard LS, Rokhlina T, Taft PJ, Rogan MP, Pezzulo AA, Karp PH, Itani OAet al. 2008. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science 321 1837–1841. ( 10.1126/science.1163600) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JW, Oommen S, Qureshi MY, Goetsch SC, Pease DR, Sundsbak RS, Guo W, Sun M, Sun H, Kuroyanagi Het al. 2020. Dysregulated ribonucleoprotein granules promote cardiomyopathy in RBM20 gene-edited pigs. Nature Medicine 26 1788–1800. ( 10.1038/s41591-020-1087-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims M, First NL.1994. Production of calves by transfer of nuclei from cultured inner cell mass cells. PNAS 91 6143–6147. ( 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6143) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair KD, Corr SA, Gutierrez CG, Fisher PA, Lee JH, Rathbone AJ, Choi I, Campbell KH, Gardner DS.2016. Healthy ageing of cloned sheep. Nature Communications 7 12359. ( 10.1038/ncomms12359) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LD.1965. Transplantation of the nuclei of primordial germ cells into enucleated eggs of Rana pipiens. PNAS 54 101–107. ( 10.1073/pnas.54.1.101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto DA, Ross PJ.2021. Similarities between bovine and human germline development revealed by single-cell RNAseq. Reproduction 161 239––253.. ( 10.1530/REP-20-0313) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spemann H.1938. Embryonic development and induction. In American Journal of the Medical Sciences, p. 401. Ed Milford H.New Haven: Oxford University Press. ( 10.1097/00000441-193811000-00047) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes M, Sachs DH.2019. Transplanting organs from pigs to humans. Science Immunology 4 eaau6298. ( 10.1126/sciimmunol.aau6298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanihara F, Takemoto T, Kitagawa E, Rao S, Do LT, Onishi A, Yamashita Y, Kosugi C, Suzuki H, Sembon Set al. 2016. Somatic cell reprogramming-free generation of genetically modified pigs. Science Advances 2 e1600803. ( 10.1126/sciadv.1600803) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KR, Capecchi MR.1987. Site-directed mutagenesis by gene targeting in mouse embryo-derived stem cells. Cell 51 503–512. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(8790646-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakayama S, Kohda T, Obokata H, Tokoro M, Li C, Terashita Y, Mizutani E, Nguyen VT, Kishigami S, Ishino Fet al. 2013. Successful serial recloning in the mouse over multiple generations. Cell Stem Cell 12 293–297. ( 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Ouyang H, Xie Z, Yao C, Guo N, Li M, Jiao H, Pang D.2015a. Efficient generation of myostatin mutations in pigs using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Scientific Reports 5 16623. ( 10.1038/srep16623) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yu H, Lei A, Zhou J, Zeng W, Zhu H, Dong Z, Niu Y, Shi B, Cai Bet al. 2015b. Generation of gene-modified goats targeting MSTN and FGF5 via zygote injection of CRISPR/Cas9 system. Scientific Reports 5 13878. ( 10.1038/srep13878) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weismann A, Poulton EBS, Shipley AES.1889. Essays upon heredity and kindred biological problems. Authorised translation, edited by E. B. Poulton, S. Schönland, and A. E. Shipley. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1891–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Rowland RR, Ewen CL, Trible BR, Kerrigan MA, Cino-Ozuna AG, Samuel MS, Lightner JE, McLaren DG, Mileham AJet al. 2016. Gene-edited pigs are protected from porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Nature Biotechnology 34 20–22. ( 10.1038/nbt.3434) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Rowland RRR, Petrovan V, Sheahan M, Cino-Ozuna AG, Fang Y, Hesse R, Mileham A, Samuel MS, Wells KDet al. 2019. Resistance to coronavirus infection in amino peptidase N-deficient pigs. Transgenic Research 28 21–32. ( 10.1007/s11248-018-0100-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmut I, Schnieke AE, McWhir J, Kind AJ, Campbell KH.1997. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 385 810–813. ( 10.1038/385810a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Ouyang H, Duan B, Pang D, Zhang L, Yuan T, Xue L, Ni D, Cheng L, Dong Set al. 2012. Production of cloned transgenic cow expressing omega-3 fatty acids. Transgenic Research 21 537–543. ( 10.1007/s11248-011-9554-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Platero-Luengo A, Sakurai M, Sugawara A, Gil MA, Yamauchi T, Suzuki K, Bogliotti YS, Cuello C, Morales Valencia Met al. 2017. Interspecies chimerism with mammalian pluripotent stem cells. Cell 168 473, .e15–486.e15. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.036) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi T, Sato H, Kato-Itoh M, Goto T, Hara H, Sanbo M, Mizuno N, Kobayashi T, Yanagida A, Umino Aet al. 2017. Interspecies organogenesis generates autologous functional islets. Nature 542 191–196. ( 10.1038/nature21070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashiro C, Sasaki K, Yabuta Y, Kojima Y, Nakamura T, Okamoto I, Yokobayashi S, Murase Y, Ishikura Y, Shirane Ket al. 2018. Generation of human oogonia from induced pluripotent stem cells in vitro. Science 362 356–360. ( 10.1126/science.aat1674) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Wang CE, Zhao B, Li W, Ouyang Z, Liu Z, Yang H, Fan P, O’Neill A, Gu Wet al. 2010. Expression of Huntington’s disease protein results in apoptotic neurons in the brains of cloned transgenic pigs. Human Molecular Genetics 19 3983–3994. ( 10.1093/hmg/ddq313) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AE, Mansour TA, McNabb BR, Owen JR, Trott JF, Brown CT, Van Eenennaam AL.2020. Genomic and phenotypic analyses of six offspring of a genome-edited hornless bull. Nature Biotechnology 38 225–232. ( 10.1038/s41587-019-0266-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Zhao H, Qing YB, Pan WR, Jia BY, Zhao HY, Huang XX, Wei HJ.2016. Porcine zygote injection with Cas9/sgRNA results in DMD-modified pig with muscle dystrophy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17 1668. ( 10.3390/ijms17101668) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Wei Y, Sun HX, Mahdi AK, Pinzon Arteaga CA, Sakurai M, Schmitz DA, Zheng C, Ballard ED, Li Jet al. 2020. Derivation of intermediate pluripotent stem cells amenable to primordial germ cell specification. Cell Stem Cell 28 550, .e12–567.e12. ( 10.1016/j.stem.2020.11.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Y, Xu W, Kan Y, Zhao HY, Zhou Y, Song X, Wu J, Xiong J, Goswami D, Yang Met al. 2020. Extensive germline genome engineering in pigs. Nature Biomedical Engineering 5 134–143. ( 10.1038/s41551-020-00613-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Liu P, Dou H, Chen L, Chen L, Lin L, Tan P, Vajta G, Gao J, Du Yet al. 2013. Handmade cloned transgenic sheep rich in omega-3 fatty acids. PLoS ONE 8 e55941. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0055941) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li Z, Yang H, Liu D, Cai G, Li G, Mo J, Wang D, Zhong C, Wang Het al. 2018. Novel transgenic pigs with enhanced growth and reduced environmental impact. eLife 7 e34286. ( 10.7554/eLife.34286) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Sang F, Withey S, Tang W, Dietmann S, Klisch D, Ramos-Ibeas P, Zhang H, Requena CE, Hajkova Pet al. 2021. Specification and epigenomic resetting of the pig germline exhibit conservation with the human lineage. Cell Reports 34 108735. ( 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108735) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L, Zhang Y, He Y, Yu H, Chen J, Liu D, Lin S, Gao M, Zhong G, Lei Wet al. 2020. Selective germline genome edited pigs and their long immune tolerance in non human primates. bioRxiv 2020.2001.2020.912105. [Google Scholar]

- Zuccaro MV, Xu J, Mitchell C, Marin D, Zimmerman R, Rana B, Weinstein E, King RT, Palmerola KL, Smith MEet al. 2020. Allele-specific chromosome removal after Cas9 cleavage in human embryos. Cell 183 1650, .e15–1664.e15. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a