Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this study was to explore the utility of measuring motivation to quit smoking as a predictor of abstinence maintenance among smokers who wanted to quit and who were included in a multicenter study conducted in daily clinical practice.

METHODS

This observational, longitudinal (prospective cohort), multicenter study was conducted in smoking clinics in Spain and the Argentine Republic in daily clinical practice. Motivation was assessed using three quantitative motivation tests and a Visual Analogue Scale. Statistical analysis included descriptive, association measures and logistic regression models.

RESULTS

Of a total of 404 subjects, 273 were ultimately included for analysis (147 women; 53.8%), mean age 51±11 years). In one year, 53.5% (36.13% by intention to treat) of subjects (146) were successful in quitting smoking [men: 45.2% (66) and women: 54.8% (80)], with no differences between sexes. None of the scales utilized was associated, in an unquestionable or direct way, with long-term abstinence, although three of them, in a very complex model, with additional variables and added interactions, were associated with the ‘result’ variable, when other variables intervened in certain circumstances.

CONCLUSIONS

None of the analyzed motivational scales alone demonstrated an association with success or failure in quitting smoking; thus, their use in isolation is of no value. Some of the scales analyzed might be related to the maintenance of abstinence but in complex models where other variables intervene, which makes interpretation considerably difficult. Therefore, the predictive capacity of the tests analyzed, based on the models, was low.

Keywords: smoking, tobacco dependence, smoking cessation, motivation scales, regression analysis, maintenance abstinence

INTRODUCTION

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death, and although the prevalence of tobacco consumption in Spain (24%, Eurobarometer 2021)1 and Argentina (22.2%)2 continues to be an important problem, it has been decreasing in recent years, especially in men. For this reason, in both countries, specialized care is offered to quit smoking.

Success in stopping smoking depends on the balance between the individual’s motivation to quit and their degree of nicotine dependence3,4. Motivation can be assessed qualitatively by asking the smoker directly about their interest and intention to quit; however, it can also be evaluated by semi-quantitative and quantitative methods4. Motivation and the number of previous attempts to quit smoking have been shown to be predictors of effort. In contrast, a low level of dependence5,6 and a high level of self-efficacy7,8 have been shown to be predictors of abstinence after the attempt to quit.

We routinely measure motivation to quit smoking using quantitative questionnaires, such as the Richmond Test (RT)9, the Henri Mondor Paris Motivation Test (HMPMT)10 and the Khimji-Watts Test (KWT)11, and semi-quantitative scales, such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). None of these motivation tests used has been validated in their original language; however, with the exception of the KWT, these motivation scales can distinguish between individuals with a higher chance of quitting or a greater number of attempts to quit, since this group scores higher in these scales3 (Supplementary file SM1). As previously mentioned3, the different scales used in this study have been considered adequate to measure the motivation of a smoker who wants to make a serious attempt to quit smoking due to their extensive and generalized use.

Several previous works have investigated predictors of smoking cessation attempts and continued abstinence, finding that motivation does not predict abstinence at any given time6. Furthermore, and it is not enough to maintain abstinence12-14, and not all the authors have reached the same conclusions. Some have found that motivation to quit smoking predicted both short- and long-term maintenance of abstinence15,16.

The aim of the study was to explore the utility of measuring motivation to quit smoking using three quantitative motivation tests and a VAS as a prediction of abstinence maintenance among smokers who wanted to quit smoking and who were included in a multicenter study conducted in daily clinical practice.

Therefore, we hypothesized that ‘high motivation, measured with questionnaires considered adequate to measure motivation for its extensive and generalized individual use to quit smoking, predicts cessation maintenance’.

METHODS

Design

The observational, longitudinal (prospective cohort), multicenter study was conducted in smoking clinics in daily clinical practice in Spain and the Argentine Republic in five tertiary hospitals, three secondary hospitals and a community specialized smoking unit. Patients were consecutively enrolled as they attended consultations from 1 October 2014 to 31 October 2015, and all patients were followed for one year. This study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for observational research (Supplementary file SM2).

Collected variables

The quantitative variables consisted of age, age at initiation of tobacco use, cigarette consumption per day (as a continuous variable; and categorical variable: 0–10, 11–20, 21–30 and >30 cigarettes/day), number of years smoking, cumulative consumption (pack-years), number of previous attempts to quit, number of previous attempts to quit in the past year, weight (kg), height (cm), body mass index (kg/m2), carbon monoxide in exhaled air (ppm), follow-up time in months, the RT, the HMPMT, the KWT, the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence (FTND)17, the Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI)18 score, and the VAS (scale of discrete values, range: 0–10), all of which were used as either continuous and/or categorical variables.

The qualitative variables consisted of patient referral (primary care, other specialists, or own free will), level of studies (basic, secondary, university), sex, reason for quitting smoking (yes/no), father and mother smoke/smoked (no/ yes/don’t know), older brother smokes/smoked (no/yes/don’t know/not applicable), rest of the brothers, the friends, co-workers and siblings smoke (don’t smoke/smoke mostly/same number of smokers as non-smokers/not applicable), comorbidities (yes/no), pharmacological and psychological treatment (yes/no; for different combinations of treatments), and outcome/result (failure/success).

Smoking cessation interventions: procedures

We defined abstinence as ‘continuous abstinence’19. We consider continuous abstinence when the subject refrained from smoking, from the moment they stopped smoking until the end of the follow-up or when they affirmed, by means of a telephone interview when not in person, that they had been abstinent in the previous three months. The treatment and follow-up intervention to stop smoking followed the regulations in force with a known protocol20. This protocol included at least 9 follow-up visits throughout the year (face-to-face and some by telephone). The patient attended the consultation in person after the initial visit at 15 and 45 days, at three, sixth, nineth months, and at one year, in addition, between the previous ones, 2 or 3 telephone visits were added (duration of the first visit was 40 minutes and in the follow-up visits 15 minutes). Smokers were treated in each clinic by its staff (doctor, nurse, and psychologist was added in some clinics) and were assigned to the treatment that has demonstrated greater effectiveness in quitting smoking following current treatment protocols (multicomponent treatment: combination of psychological-behavioral and pharmacological treatment).

We measure motivation to quit smoking using quantitative questionnaires, including the Richmond Test (RT)9, the Henri Mondor Paris Motivation Test (HMPMT)10 and the Khimji-Watts Test (KWT)11, and a semi-quantitative scale, the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).

To corroborate self-reported abstinence by subjects, an expired air carbon monoxide (CO) meter was used at each clinic and at all visits during the 12-month follow-up (we used a cut-off point of CO ≤6 ppm to be considered a non-smoker)21. When consultation was by telephone, we recorded the verbal self-report of not smoking.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were described by absolute value and percentage, and quantitative variables were described as mean with standard deviation, and range of values. The association between qualitative variables was evaluated using a chi-squared test. When the expected value criterion was not fulfilled in table cells ≥5, Fisher’s exact test was used in the case of 2 × 2 tables. In some cases of ordinal qualitative variable, the linear association test was also used. In the case of finding a significant association between the qualitative variables, the difference in percentages between the categories that introduce significance is expressed with the standard error. The relationship between qualitative and quantitative variables was evaluated using Student’s t-test. Normal distribution was verified using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the homogeneity of the variances was evaluated using the Levene test. In the case of non-compliance with any of these 2 assumptions, the non-parametric U-Mann-Whitney test was used for analysis. In the case of statistically significant difference in means, this is expressed by the standard error and 95% confidence interval.

Association between the outcome variable of the attempt to quit smoking and the motivation scales (RT, HMPMT, KWT and VAS) was tested using logistic regression. Given the high number of variables, the procedure was performed as follows. The statistical significance of the variable Motivation scale to quit smoking was assessed, controlling for the variables sex, age and Type of treatment, and, one by one, each of the remaining variables. The variable Type of treatment chosen for these models was Varenicline alone or Combined vs Other treatments vs No treatment, because varenicline is the more effective and powerful treatment to quit smoking22. When models were evaluated for other treatments, such as bupropion, nicotine replacement treatment (NRT), or combinations of NRT, the mentioned treatment variable was replaced with the corresponding treatment variable. All models included the variables in question and all possible first-order interactions between them. The backward step regression or backward elimination method was used as the automatic variable selection method to evaluate the interactions. Furthermore, when deemed necessary, the selection process for the best logistic regression equation for predictive purposes was performed in an automated way using a script or extension command for SPSS designed by the Laboratori d’Estadistica Aplicada of the Universidad Autónoma from Barcelona (Spain)23. In this case, the following selection criteria were used for the best logistic regression model: 1) The Akaike information criterion; 2) area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve; 3) sensitivity and specificity of the models for a cut-off point of 0.5; 4) value of -2 times the logarithm of the verisimilitude (-2LL); and 5) degree of significance of the Hosmer-Lemeshow adjustment index and degree of significance of the adjustment index of Le Cessie-van Houwelingen. The proportion of variance of the dependent variable explained by the predictor (independent) variables was evaluated using the Cox and Snell R2 and Nagelkerke’s R.

The following aspects were analyzed once the final regression model was obtained: 1) independence from residuals; 2) linearity; 3) absence of collinearity; and 4) absence of distant values of the response variable or of the predictor variables, and of influential values that affect the estimates. After evaluating the diagnosis of the model, its validity was studied by constructing the ROC curve and estimating the area under it. The accuracy of the area of the ROC curve was assessed following the Swets classification24. Subsequently, the cut-off point of prevalence or probability of success was selected that yielded the highest efficiency values (highest percentage of correct classifications), together with the highest sensitivity value plus specificity. Subjects with missing values were excluded from the statistical analyses.

Analyses were performed using the statistical programs SPSS v.20 for Windows (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.), MedCalc Statistical Software v.16.8. (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium), and STATA/SE 15.1 (Stata Corp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: Stata Corp LLC). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Descriptive analysis

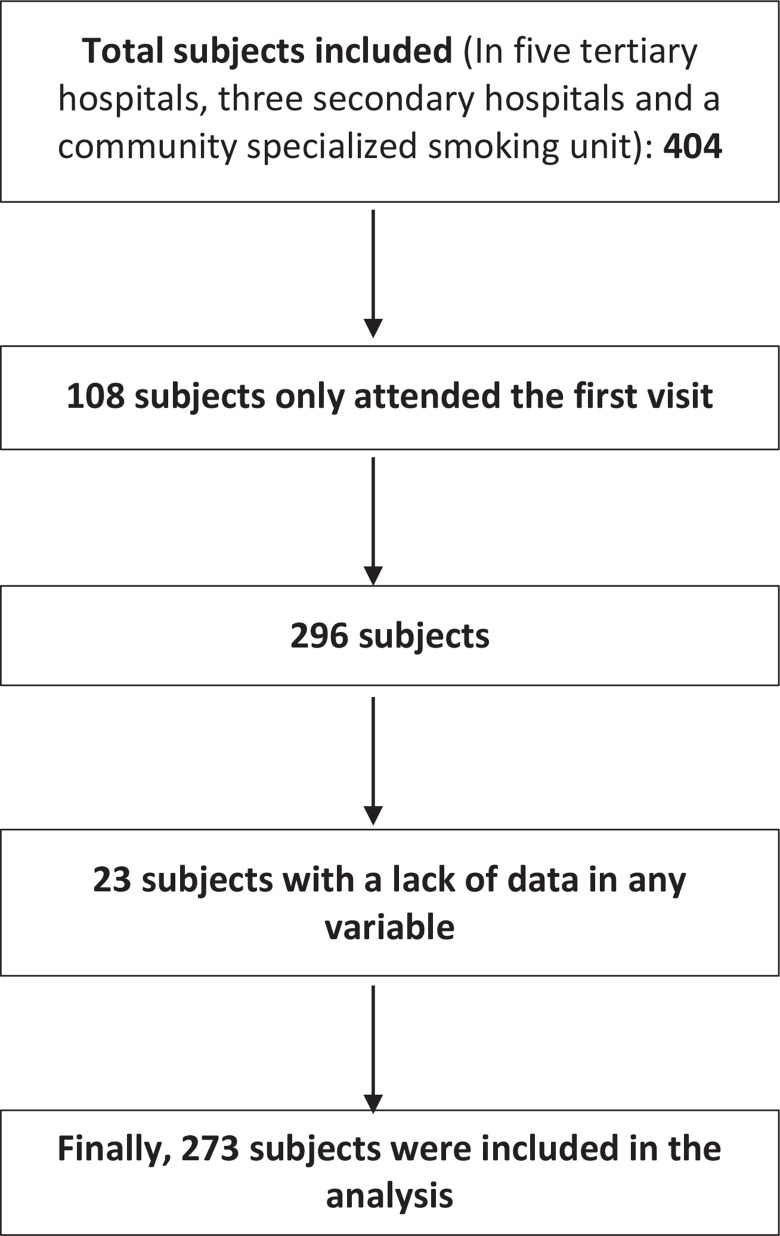

A total of 404 subjects were included, of whom 108 only attended the first visit. Of the remaining 296, a total of 23 subjects had a lack of data on any variable; therefore, 273 subjects (147 women, 53.8%; mean age 51±11 years) were ultimately included in the analysis (Figure 1). Material given in Supplementary file SM3 shows the characteristics (frequencies) of all qualitative variables for the total sample and by sex, and comparison between sexes. Supplementary file SM4 shows the descriptive values of the quantitative variables, for the total sample and by sex, with comparison between sexes.

Figure 1.

Flowchart detailing subjects’ selection

Descriptive and bivariate analysis of the result variables

At one year, 53.5% (36.13% by intention to treat) of the subjects (146) were successful in quitting smoking, i.e. 66 (45.2%) males and 80 (54.8%) females, with no significant differences between the sexes. Supplementary file SM5 and SM6 show the percentages of each qualitative and quantitative variable, respectively, in relation to the Result variable. We identified an association between the Result of quitting smoking and the educational level (p=0.011). No association was observed between the mean scores of any of the motivation tests included to quit smoking (RT, HMPMT, KWT or VAS) or the success or failure, either for the overall series or by sex (Supplementary file SM5 and SM6).

Multivariate analysis of motivation tests to quit smoking

Table 1 shows the degree of significance of the different variables in the different tests of motivation to quit smoking, controlling for the variables age, sex and type of treatment at the first analysis.

Table 1.

Degree of significance of the different tests of motivation to quit smoking, controlling for the variables age, sex, and type of treatment, for the following variablesa

| Variables | RT | VAS | HMPMT | KWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative variables | ||||

| Patient referral (primary care, other specialists, or own free will) | 0.786 | 0.661 | 0.197 | 0.112 |

| Level of studies (basic, secondary, or university) | 0.967 | 0.171 | 0.053 | 0.048 |

| Quit-smoking reasons | ||||

| Health/prevention | 0.973 | 0.422 | 0.114 | 0.068 |

| Health/decrease in symptoms | 0.939 | 0.388 | 0.020 | 0.670 |

| Stop being dependent | 0.973 | 0.370 | 0.115 | 0.060 |

| Saving money | 0.973 | 0.398 | 0.136 | 0.079 |

| Quality of life | 0.973 | 0.419 | 0.182 | 0.063 |

| Do not harm my children/partner | 0.973 | 0.394 | 0.123 | 0.843 |

| Be a good example | 0.853 | 0.414 | 0.113 | 0.090 |

| Number of reasons for quit smoking | 0.820 | 0.431 | 0.123 | 0.096 |

| Smoking situation | ||||

| Father smokes/smoked | 0.951 | 0.476 | 0.340 | 0.035 |

| Mother smokes/smoked | 0.887 | 0.491 | 0.170 | 0.064 |

| Older brother smokes/smoked | 0.755 | 0.213 | 0.071 | 0.788 |

| Other brothers smoke | 0.894 | 0.360 | 0.062 | 0.020 |

| Friends smoke | 0.906 | 0.408 | 0.175 | 0.056 |

| Co-workers smoke | 0.976 | 0.640 | 0.243 | 0.193 |

| Illness | ||||

| COPD | 0.986 | 0.362 | 0.040 | 0.401 |

| Asthma | 0.888 | 0.432 | 0.119 | 0.066 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.970 | 0.378 | 0.110 | 0.090 |

| Arterial hypertension | 0.888 | 0.568 | 0.127 | 0.080 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.888 | 0.745 | 0.116 | 0.129 |

| Lung cancer | 0.978 | 0.442 | 0.113 | 0.084 |

| Bladder cancer, cerebral strokeb | - | - | - | - |

| Depression | 0.943 | 0.460 | 0.119 | 0.056 |

| Anxiety | 0.888 | 0.297 | 0.093 | 0.039 |

| Dependence tests | ||||

| Fagerström test | 0.730 | 0.484 | 0.136 | 0.071 |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index test | 0.730 | 0.471 | 0.117 | 0.064 |

| Type of treatmentc | ||||

| Pharmacological/psychological treatment typed | 0.861 | 0.420 | 0.953 | 0.309 |

| Treatment alone vs combinede | 0.917 | 0.270 | 0.191 | 0.358 |

| Varenicline alone or combined vs other treatments vs without treatment | 0.917 | 0.470 | 0.121 | 0.064 |

| Types of NRT treatmentsf | ||||

| Patches | 0.723 | 0.414 | 0.186 | 0.068 |

| Gums | 0.723 | 0.461 | 0.145 | 0.087 |

| Tablets | 0.723 | 0.473 | 0.169 | 0.790 |

| Oral spray | 0.723 | 0.581 | 0.075 | 0.098 |

| Patches + gums | 0.723 | 0.477 | 0.135 | 0.049 |

| Patches + tablets | 0.723 | 0.409 | 0.237 | 0.504 |

| Patches + oral spray | 0.723 | 0.456 | 0.110 | 0.526 |

| Other combinationsg | - | - | - | - |

| Number of NRT therapies | 0.723 | 0.533 | 0.196 | 0.076 |

| Nicotine dependence treatments | ||||

| Varenicline alone | 0.723 | 0.554 | 0.206 | 0.077 |

| Bupropion alone | 0.693 | 0.498 | 0.250 | 0.072 |

| NRT alone | 0.805 | 0.623 | 0.194 | 0.396 |

| Quantitative variablesh | ||||

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.730 | 0.531 | 0.150 | 0.581 |

| Sex | 0.730 | 0.534 | 0.187 | 0.610 |

| Age and sex | 0.730 | 0.506 | 0.147 | 0.127 |

| Age of initiation (years) | 0.956 | 0.019 | 0.129 | 0.053 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Cigarettes/day | 0.917 | 0.471 | 0.117 | 0.065 |

| Number of years smoking | 0.956 | 0.154 | 0.129 | 0.053 |

| Cumulative consumption (pack-years) | 0.956 | 0.451 | 0.125 | 0.056 |

| Number of previous quit attempts | 0.917 | 0.728 | 0.006 | 0.071 |

| Number of previous quit attempts (past/year) | 0.917 | 0.517 | 0.118 | 0.068 |

| Physical/psychological characteristics | ||||

| Weight | 0.524 | 0.750 | 0.306 | 0.433 |

| Height | 0.709 | 0.721 | 0.220 | 0.010 |

| BMI | 0.709 | 0.760 | 0.275 | 0.073 |

| Carbon monoxide (ppm) | 0.598 | 0.061 | 0.012 | <0.001 |

| VAS | 0.917 | 0.470 | 0.119 | 0.066 |

| HMPMT | 0.917 | 0.721 | 0.155 | 0.585 |

| KWT | 0.917 | 0.875 | 0.192 | 0.093 |

RT: Richmond Test for quitting smoking. VAS: visual analogue scale. HMPMT: Henry Mondor Paris Motivation Test. KWT: Khimji-Watts Test. BMI: body mass index (kg/m2). NRT: nicotine replacement therapy. COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The models include the mentioned variables and all their possible interactions.

These variables were not analyzed as only one subject had this antecedent.

In the treatment models, the variable Type of treatment used so far, namely, Varenicline alone or Combined vs Other treatments vs No treatment that contains the categories No treatment, Other treatments, and Varenicline-containing treatments, is replaced by the specific treatment variable mentioned.

Categorized as: No treatment (Reference category), Only pharmacological treatment, Only psychological treatment, and Pharmacological and psychological treatment.

Categorized as: No treatment (Reference category), Varenicline, Bupropion or NRT alone, and Combined treatment (Varenicline + NRT, Varenicline + Bupropion, or Bupropion + NRT).

Nicotine replacement therapy.

Other combinations of nicotine replacement therapy were not studied due to the small number of effective treatments.

The models with the variables: Age only, Sex only, and Age and Sex, do not include the variable Treatment. Starting with the variable Age of initiation, the models include the variables mentioned in the title of the table.

In examining the effect of the RT score on the variable Result in the abstinence maintenance, none of the models showed any association between either variable.

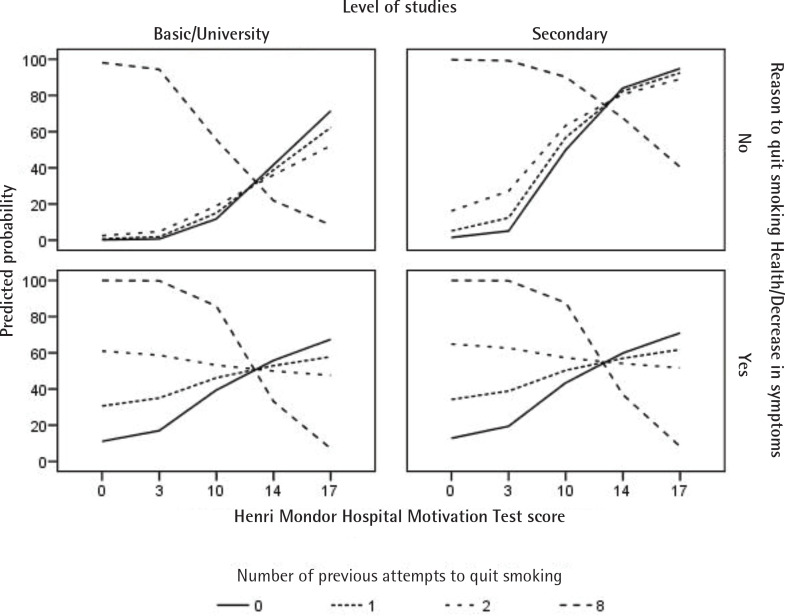

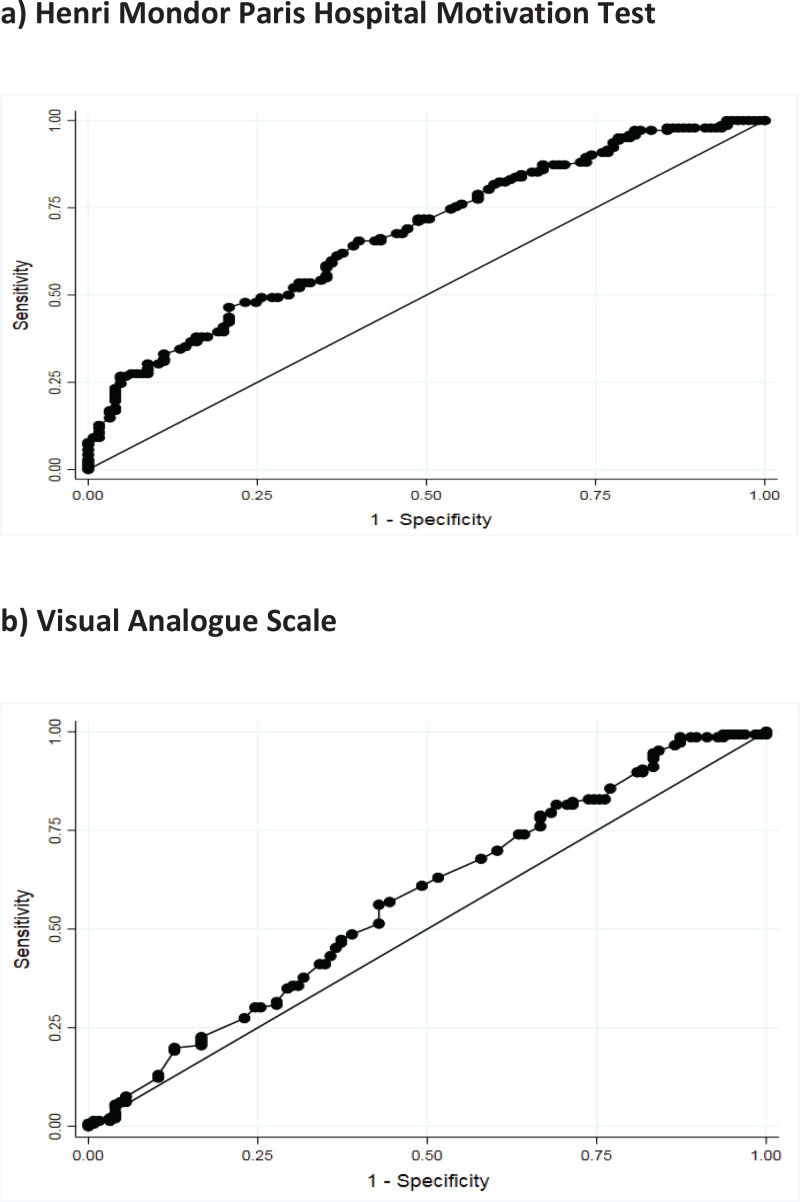

The results of the study of the effect of the HMPMT score on the variable Result are shown in Table 2, and the regression model is shown in Figure 2. The score of the HMPMT was associated with the variable Result in quitting smoking in a complex model in which the variables Number of previous attempts, Level of studies, and Reason for quitting smoking (Health/Reduction of symptoms) intervene. The higher the HMPMT score, the greater the probability of quitting, although it depends on the variable Number of previous attempts. The statement of the previous point is valid for subjects with few previous attempts to quit smoking (≤2). Conversely, subjects with a high number of previous attempts to quit smoking are more likely to quit smoking with low scores on the HMPMT (as the score of this test increases, the probability of quitting smoking decreases, especially after 10 points). Therefore, the decision to start or not start treatment in a subject based on the score of the HMPMT should also take into account other variables, such as the Number of previous attempts, the Level of studies, and whether their motivation to quit smoking is due to health/decrease in symptoms. In this case, we could not show that abstinence was determined by the previously chosen smoking cessation treatment. The area under the ROC curve of this model was 0.678±0.032 (95% CI: 0.618–0.734, p<0.001), showing low accuracy (Figure 3a).

Table 2.

Logistic regression models for the VAS motivational test, the HMPMT and KWT

| Variable | OR | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| Henri Mondor Paris Motivation Test (n=267) | ||||

| HMPMT | 1.52 | <0.001 | 1.21 | 1.91 |

| Health/decrease in symptom motivation [yes vs no (Ref.)] | 60.07 | 0.009 | 2.75 | 1311.35 |

| Number of previous quit attempts | 3.54 | 0.004 | 1.48 | 8.46 |

| Level of studies [secondary vs basic/university (Ref.)] | 7.40 | 0.000 | 2.77 | 19.80 |

| HMPMT × Health/decrease in symptom motivation | 0.78 | 0.026 | 0.62 | 0.97 |

| HMPMT × Number of previous quit attempts | 0.91 | 0.005 | 0.85 | 0.97 |

| Health/decrease in symptom motivation × Level of studies | 0.16 | 0.002 | 0.05 | 0.51 |

| Visual Analogue Scale (n=272) | ||||

| Visual analogue scale | 2.33 | 0.019 | 1.15 | 4.73 |

| Age of initiation | 1.49 | 0.030 | 1.04 | 2.15 |

| Visual analogue scale × Age of initiation | 0.95 | 0.024 | 0.91 | 0.99 |

| Khimji-Watts Test (n=208) | ||||

| KWT | 0.07 | 0.018 | 0.01 | 0.64 |

| Sex [male vs female (Ref.)] | 142.04 | 0.006 | 4.03 | 5008.56 |

| Father smokes/smoked [yes vs no (Ref.)] | 3.09 | 0.002 | 1.53 | 6.22 |

| Height (cm) | 0.81 | 0.010 | 0.68 | 0.95 |

| Number of NRT therapies (Ref.) | 0.68 | 0.035 | 0.47 | 0.97 |

| KWT × Sex | 0.65 | 0.005 | 0.48 | 0.88 |

| KWT × Height | 1.02 | 0.012 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| Khimji-Watts Test (n=252), without the variable Height | ||||

| KWT | 1.13 | 0.081 | 0.98 | 1.30 |

| Sex [male vs female (Ref.)] | 7.54 | 0.097 | 0.69 | 82.18 |

| Sex [male vs female (Ref.)] | 1.98 | 0.027 | 1.08 | 3.62 |

| Number of NRT therapies (Ref.) | 0.78 | 0.113 | 0.57 | 1.06 |

| KWT × Sex | 0.83 | 0.075 | 0.68 | 1.02 |

OR: odds ratio.

Figure 2.

Graphic representation of the distribution of predicted probabilities according to the model in Table 2 for the different combinations of values of dummy subjects of the variables Henri Mondor Paris Motivation Test, Number of previous quit attempts, Level of studies, and Reason to quit smoking (Health/decrease in symptoms)

Figure 3.

ROC curves corresponding to the logistic regression models of the Visual Analogue Scale and the Henri Mondor Paris Motivation Test

The outcomes of the effect of the VAS score on the variable Result are shown in Table 2. The only variable with which the VAS variable showed statistical significance with the variable Result was Age of onset of tobacco use. The regression model presented a good fit of the model to the data (Hosmer-Lemeshow adjustment index was not significant p=0.594); however, the overall significance of the model was almost significant (p=0.079). The study of the internal validity of the model showed that the ROC curve was almost superimposable to the diagonal line of the graph, indicating poor predictive capacity of the model. The area under the ROC curve was 0.573±0.035 (95% CI: 0.512–0.633), discretely above the area of the diagonal that was 0.5 (Figure 3b). The best cut-off point of probability of success, which produces the best percentage of correct classifications was ≥0.411, but this percentage of correct classifications was only 58.82%, with a sensitivity of 98.63%, and a specificity of 12.70%. Given these results of internal validity, the model lacks relevant predictive capacity regarding association with the Result variable. Therefore, although there might be a certain association between the score of the VAS and the Result variable, this association would be modulated by the variable Age of onset of tobacco use to smoking; thus, we did not identify an association between the variables.

The results of this study on the effect of KWT score on the variable Result are also shown in Table 2. The score of the KWT to quit smoking was associated with the variable Result in quitting smoking in a complex model in which the variables: sex, father smokes/smoked, height, and number of treatments with NRT. However, the height variable was a variable with low probability or biological plausibility of association with smoking abstinence; so, when it was excluded, the KWT did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

The main conclusion of our work was that none of the scales used was associated, in an unquestionable and direct way, with long-term abstinence, although three of them, in a very complex model, with additional variables and added interactions, were associated with the Result variable, when other variables intervened in certain circumstances.

Our results are consistent with previous studies, both for and against, that initial high levels of motivation predict sustained abstinence. Borland et al.12 concluded that it is wrong to suggest that all that is needed to quit smoking is motivation. However, motivation is necessary to prompt action to stop smoking but is not sufficient in itself to ensure that cessation is maintained. Perski et al.25 found that the perception of being addicted was positively associated with the motivation to quit smoking and having recently made an attempt to quit, but was not associated with attempts to quit in the future or with maintaining abstinence. Klemperer et al.26 found that the only variable that predicted the beginning of an attempt to quit smoking was a longer time of the first cigarette in the morning after getting out of bed, although a higher score of self-efficacy and an increased initial motivation were the only variables that predicted converting the attempt to quit to maintenance of abstinence. In the study by Kale et al.27, the only variable in the multivariate analysis that was associated with and predicted abstinence at three months was having a pathology related to tobacco use. In these previous studies, motivation was associated with the attempt to quit smoking but not with the maintenance of abstinence, which has also been observed by other investigators6,12-14,28.

Not all studies have reached to the above conclusions. Boardman et al.29 found that higher levels of motivation increase the likelihood of maintaining smoking cessation. Wee et al.30 and Williams et al.16 found that motivation to quit predicts abstinence at 3 and 6 months. Likewise, in other studies, initial levels of motivation to quit predicted smoking cessation31,32, and motivation predicted continuous smoking abstinence in a sample of pregnant woman33. Piñeiro et al.15 concluded that motivation to quit smoking predicted short- and long-term cessation, and predicted long-term maintenance of abstinence.

Motivation is a broad term that means ‘desire’ or ‘to want’, implying movement either towards or away from a future action and is not the same thing as ‘quit intention’34. An intention is more than motivation and suggests readiness to perform the behavior and captures a commitment to act, reflecting volitional processes34. When motivation is separated into its different components, ‘desire’ and ‘intention’ have been shown to be independent predictors of the attempt to quit, while ‘duty’ mitigates the predictive value of the previous two35. Therefore, it is clear that motivation is key to change; it is a multidimensional, dynamic and fluctuating state that is interactive and can be modified36. Since motivation is multidimensional, it cannot be easily measured with just one instrument or scale; a consensus panel36 has recommended that substance abuse treatment staff use a variety of tools to measure various dimensions of motivation (self-efficacy, importance of change, preparation for change, decisional balancing, and motivations for using substances). Recently, Minian et al.37, reviewed the possible contexts and mechanisms used in multiple health behavior change interventions that are associated with improving smoking cessation outcome. To identify the mechanism of behavioral change, they used opportunity (defined as ‘all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behavior possible or prompt it’), capability (defined as ‘individual's psychological and physical capacity to engage in healthy behavior’) and motivation (defined as ‘all those brain processes that energize and direct behavior, not just goals and conscious decision-making’). They concluded that motivation in smoking cessation appears effective in certain contexts for improving smoking cessation outcomes, including those with intervention in community-based settings were more likely to quit smoking long-term, while applying motivation as a mechanism in clinical settings and intervention that aimed to increase participants’ motivation had mixed results. Once the decision to quit is made, success is determined more by the degree of dependence than the level of motivation4, and the level of confidence in succeeding to quit is another important factor that is also indicative of success8,37. Motivation varies over time, even in a short space of time38 and is heavily influenced by circumstances. When smokers relate their desire to quit in a clinical interview, they may not be accurately reflecting their true feelings4. Perhaps this is what causes motivation to be associated with additional variables and interactions that could intervene in certain circumstances, as observed in our study. All of this indicates that motivation may be important as a first step in the attempt to quit process, but other factors could contribute to quitting success, making it important to study the determinants of quit attempts separately from predictors of success37.

Limitations

The present work has several limitations. First, the findings were obtained using smokers who voluntarily attended smoking cessation clinics, and the surveys were performed in different scenarios and geographical locations, which might not reflect the general population. Second, both the dependency and motivation tests were developed to be answered face-to-face. However, in some cases, the questionnaires were delivered to and completed at the participant’s home and brought back at a later time. Third, the use of questionnaires in patients is not always accurate. Fourth, the fact that some of the motivational measures were associated with smoking outcomes could be due to the fact that these are not validated measures, so they could be measuring something other than motivation to quit smoking. Fifth, the sampling strategy and the dimensions of the sample may not have sufficient statistical strength to identify differences. Sixth, although there were few subjects in our work with missing data, they were excluded from the work, we are therefore aware that they could have an effect on the conclusions, reducing the representativeness of the sample obtained and therefore distorting the inferences about the population. This variability could lead to other results.

In view of the results, we suggest that it is not worth measuring the motivation to quit smoking with the instruments analyzed, since they do not predict smoking abstinence and can be misleading in the approach of each specific case, in the sense that a low score in such tests may suggest that the subject is not motivated and consequently not offered treatment that could lead to smoking abstinence, a decision based on clearly unreliable instruments.

CONCLUSIONS

None of the analyzed tests demonstrated by themselves an association with success or failure in quitting smoking; thus, the use of their score, taken in isolation for the assessment of the indication for treatment without considering other variables, lacks any utility. Some of the analyzed tests might be related to the results of attempts to quit smoking, but in complex models, in which other variables intervene, this intervention considerably hinders the interpretation of the score obtained in these tests when making decisions about whether a specific subject should be treated or not treated to quit smoking. The predictive capacity of the tests analyzed, in relation to the Result in quitting smoking and based on the models found, was low and RT was of no use in measuring motivation to quit smoking.

Therefore, although there are some validated scales to measure motivation, we believe that there is a need to develop new instruments that can predict smoking abstinence, which would be useful when deciding which subjects are offered treatment to stop smoking and which are not.

Supplementary Material

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have each completed and submitted an ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no competing interests, financial or otherwise, related to the current work. JIG-O has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Chiesi, Esteve, Faes, Gebro, Menarini, and Pfizer. CAJR has received honoraria for advisory and talks for pharmaceutical companies trading smoking cessation medications. LL-A has received honoraria for lecturing, participation in clinical studies and writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer, Chiesi, Esteve, Ferrer, Grifols, GSK, Menarini, Novartis, and Pfizer. SS-R has received honoraria for lecturing, participation in clinical studies and writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Boehringer, Esteve, Pfizer, and Sandoz.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Spanish Respiratory Society (SEPAR) under Grant No. 146/2013.

ETHICAL APPROVAL AND INFORMED CONSENT

This work was presented and approved by each one of the ethics committees of the participating centers: HU12O CEIC 13/350; Alicante CEIC 2013/44; Málaga CEIC (31/01/2014); Burgos CEIC 1322; HCSC-UET CEIC nº 14/121-E; HGUGM- Acta 01/2014; HNC 185/14; Rosario SP 20/01/2014; and Avilés 16/12/2013.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have introduced patients to the study in our smoking cessation clinics. JIGO: conception and design of the study, writing the core content of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. JFPL: statistical analysis and interpretation of data, preparation and critical review of the manuscript. SAS, SSR, MGR, MAMM, LLA, DB, RP, SL, ICA and CAJR: critical review of the manuscript. All authors approved the current version of the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting this research is available from the authors on reasonable request.

PROVENANCE AND PEER REVIEW

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.European Commission Attitudes of Europeans towards tobacco and electronic cigarettes. Special Eurobarometer 506. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/health/tobacco/eurobarometers_en.

- 2.Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo, Cobertura Universal de Salud, Secretaría de Gobierno de Salud, Ministerio de Salud y Desarrollo Social - Presidencia de la Nación 4o Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo: Principales Resultados. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://bancos.salud.gob.ar/sites/default/files/2020-01/4ta-encuesta-nacional-factores-riesgo_2019_principales-resultados.pdf.

- 3.de Granda-Orive JI, Pascual-Lledó JF, AsensioSánchez S, et al. Is There an Association Between the Degree of Nicotine Dependence and the Motivation to Stop Smoking? Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2019;55(3):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West R. Assessment of dependence and motivation to stop smoking. BMJ. 2004;328(7435):338–339. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vangeli E, Stapleton J, Smit ES, Borland R, West R. Predictors of attempts to stop smoking and their success in adult general population samples: a systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2110–2121. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ussher M, Kakar G, Hajek P, West R. Dependence and motivation to stop smoking as predictors of success of a quit attempt among smokers seeking help to quit. Addict Behav. 2016;53:175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smit ES, Hoving C, Schelleman-Offermans K, West R, de Vries H. Predictors of successful and unsuccessful quit attempts among smokers motivated to quit. Addict Behav. 2014;39(9):1318–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Granda-Orive JI, Pascual-Lledó JF, Solano-Reina S, et al. When Should We Measure Self-Efficacy as an Aid to Smoking Cessation? Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2019;55(12):654–656. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2019.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richmond RL, Kehoe LA, Webster IW. Multivariate models for predicting abstention following intervention to stop smoking by general practitioners. Addiction. 1993;88(8):1127–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Torre G, Saulle R, Nicolotti N, De Waure C, Gualano MR, Boccia S. From nicotine dependence to genetic determinants of smoking. In: La Torre G, editor. Smoking Prevention and Cessation. Springer; 2013. pp. 1–21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khimji H, Watts J. Two years evaluation of general practice based smoking cessation clinic. J Smok Relat Disord. 1994;5:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(Suppl 1):S4–11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. Suppl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.West R, McEwen A, Bolling K, Owen L. Smoking cessation and smoking patterns in the general population: a 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2001;96(6):891–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96689110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherrill B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009;34(4):365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piñeiro B, López-Durán A, Del Río EF, Martínez Ú, Brandon TH, Becoña E. Motivation to quit as a predictor of smoking cessation and abstinence maintenance among treated Spanish smokers. Addict Behav. 2016;53:40–45. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams GC, Gagné M, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Facilitating autonomous motivation for smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2002;21(1):40–50. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.21.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagerstrom KO, Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT. Nicotine addiction and its assessment. Ear Nose Throat J. 1990;69(11):763–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with selfreported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34(3):211–216. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West R, Hajek P, Stead L, Stapleton J. Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel . Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63952/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Middleton ET, Morice AH. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. Chest. 2000;117(3):758–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD009329. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doménech JM. Análisis multivariante: modelos de regresión. UD. 12: modelos de regresión con datos de supervivencia. Signo; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240:1285–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3287615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perski O, Herd N, West R, Brown J. Perceived addiction to smoking and associations with motivation to stop, quit attempts and quitting success: A prospective study of English smokers. Addict Behav. 2019;90:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemperer EM, Mermelstein R, Baker TB, et al. Predictors of Smoking Cessation Attempts and Success Following Motivation-Phase Interventions Among People Initially Unwilling to Quit Smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(9):1446–1452. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kale D, Gilbert HM, Sutton S. Are predictors of making a quit attempt the same as predictors of 3-month abstinence from smoking? Findings from a sample of smokers recruited for a study of computer-tailored smoking cessation advice in primary care. Addiction. 2015;110(10):1653–1664. doi: 10.1111/add.12972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Girvalaki C, Filippidis FT, Kyriakos CN, et al. Perceptions, Predictors of and Motivation for Quitting among Smokers from Six European Countries from 2016 to 2018: Findings from EUREST-PLUS ITC Europe Surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boardman T, Catley D, Mayo MS, Ahluwalia JS. Self-efficacy and motivation to quit during participation in a smoking cessation program. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):266–272. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wee LH, West R, Bulgiba A, Shahab L. Predictors of 3-month abstinence in smokers attending stop-smoking clinics in Malaysia. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(2):151–156. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 1991;10(5):360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jardin BF, Carpenter MJ. Predictors of quit attempts and abstinence among smokers not currently interested in quitting. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(10):1197–1204. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heppner WL, Ji L, Reitzel LR, et al. The role of prepartum motivation in the maintenance of postpartum smoking abstinence. Health Psychol. 2011;30(6):736–745. doi: 10.1037/a0025132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veilleux JC. Shifts in momentary motivation to quit smoking based on experimental context and perceptions of motivational instability. Addict Behav. 2019;96:62–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smit ES, Fidler JA, West R. The role of desire, duty and intention in predicting attempts to quit smoking. Addiction. 2011;106(4):844–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller WR. Mejorando la Motivación para el Cambio en el Tratamiento de Abuso de Sustancias. Serie De Protocolo Para Mejorar El Tratamiento (TIP-Por Sus Siglas En Inglés De Treatment Improvement Protocol) Departamento de Salud y Servicios Humanos de los EE.UU; 1999. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://web.vocespara.info/comparte/2017_vcs/Drogodependencias_y_adicciones/Mejorando_la_motivacion_para_el_cambio_en_el_tratamiento_de_abuso_de_sustancias.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minian N, Corrin T, Lingam M, et al. Identifying contexts and mechanisms in multiple behavior change interventions affecting smoking cessation success: a rapid realist review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):918. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08973-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes JR, Keely JP, Fagerstrom KO, Callas PW. Intentions to quit smoking change over short periods of time. Addict Behav. 2005;30(4):653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this research is available from the authors on reasonable request.