Executive Summary.

While the United States (US) population at large is rapidly diversifying, cardiothoracic surgery is among the least diverse specialties in terms of racial and gender diversity. Lack of diversity is detrimental to patient care, physician well-being, and the relevance of cardiothoracic surgery on our nation’s health. Recent events, including the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests, have further accentuated the gross inequities that underrepresented minorities face in our country and have reignited conversations on how to address bias and systemic racism within our institutions. The field of cardiothoracic surgery has a responsibility to adopt a culture of diversity and inclusion. This kind of systemic change is daunting and overwhelming. With bias ubiquitously entangled with everyday experiences, it can be difficult to know where to start.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Workforce on Diversity and Inclusion presents this approach for addressing diversity and inclusion in cardiothoracic surgery. This framework was adapted from a model developed by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and includes information and recommendations generated from our literature review on diversity and inclusion. A MEDLINE search was conducted using keywords “diversity,” “inclusion,” and “surgery,” and approaches to diversity and inclusion were drawn from publications in medicine as well as non-healthcare fields. Recommendations were generated and approved by The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Executive Committee.

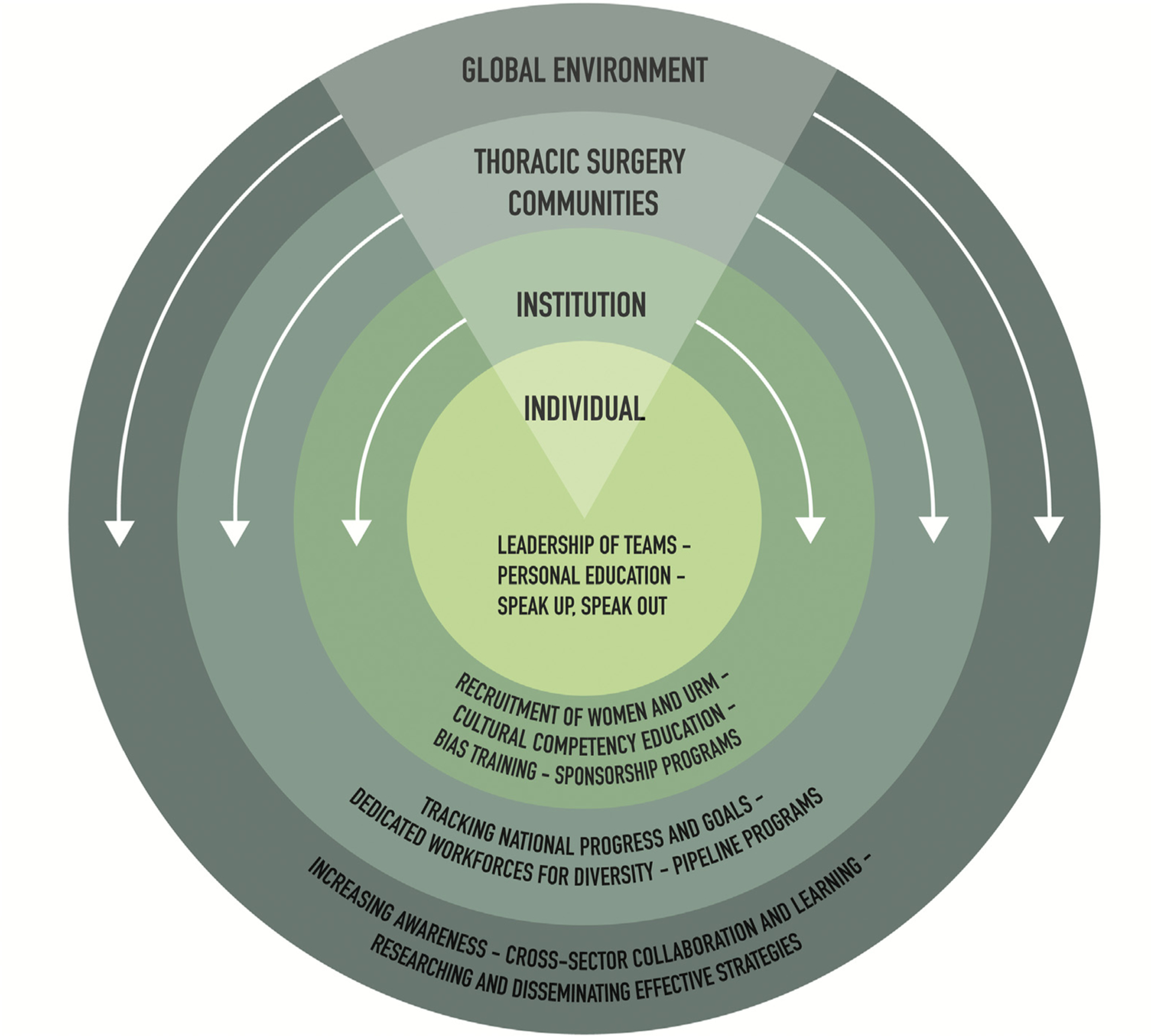

We present an overarching framework that conceptualizes diversity and inclusion efforts in a series of concentric spheres of influence, from the global environment to the cardiothoracic community, institution, and the individual surgeon. This framework organizes the approach to diversity and inclusion, grouping interventions by level while maintaining a broader perspective of how each sphere is interconnected. We include the following key recommendations within the spheres of influence:

In the global environment, it is important to understand how cardiothoracic surgery compares to fields outside of surgery and medicine overall in diversity and inclusion, and cardiothoracic surgeons should look to and learn from advances in other professions.

Professional societies that represent the cardiothoracic community share a responsibility to prioritize specialty-wide action to improve diversity in membership, mentorship, leadership, and representation at annual meetings.

Each institution (including health systems, medical schools, and clinical departments/sections) must perform a self-assessment of diversity and implement program-specific strategies to achieve diversity goals.

Individual surgeons can create cultures of inclusion by assessing personal implicit biases and advocating for diversity and inclusion.

It is important to note that each of the spheres of influence is interconnected. Interventions to improve diversity must be coordinated across spheres for concerted change. Altogether, this multilevel framework (global environment, cardiothoracic community, institution, and individual) offers an organized approach for cardiothoracic surgery to assess, improve, and sustain progress in diversity and inclusion.

Despite the diversifying face of the US population at large,1 the workforce of US physicians has remained overwhelmingly White and male. Numerous studies have demonstrated that women and underrepresented minority physicians comprise a smaller proportion of employed doctors relative to the general US population.2 While African Americans and Hispanics made up 13.4% and 18.3% of the US population in 2018,3 these 2 groups accounted for only 5.0% and 5.8% of all active physicians,4 respectively. Similarly, women made up 50.8% of the 2018 US population3 and 47.9% of 2018 US medical school graduates,5 yet they only comprised 35.8% of practicing physicians.6

This diversity gap in the physician workforce is even more apparent in the surgical fields. Relative to nonsurgical specialties, fewer underrepresented minority physicians enter surgery.7–10 Once in a surgical specialty, these minority physicians are significantly slower to ascend the ranks. A study by Siotos and colleagues11 found in 2013 that the ratio of White to non-White surgeons was 2.86 compared with 2.0 in nonsurgical specialties. The ratio of men to women across surgical specialties was 2.95. Moreover, despite an increase in women in medicine overall, fewer women practiced thoracic surgery in 2013 than in 2000.11 Only 7% of practicing cardiothoracic surgeons and 20% of cardiothoracic surgery residents in training were women in 2017 and 2015, respectively.12,13 It is clear much work needs to be done in the cardiothoracic surgery profession to correct the disparities in demographic makeup compared with the composite US population.

Importance of Increasing Diversity

Aside from the inherent benefits of a diverse, inclusive, and socially just environment, correcting the physician diversity gap leads to improved patient care. Patients report improved satisfaction with their healthcare when they are treated by a same-ethnicity provider.14,15 Same-ethnicity physicians may engage patients and their family using shared cultural context and language better than physicians from different ethnicities. Same-ethnicity physicians can also provide cultural insight and perhaps education to the entire care team, which may improve patient compliance. Underrepresented minority physicians are also more likely to care for minority patient populations.16–18 Therefore, closing diversity gaps within the medical community may help alleviate racial disparities as the US population continues to diversify.

Increasing diversity and inclusion may improve cognitive processes and knowledge overall. A study by Whitla and colleagues19 found that increased peer diversity among medical students enhanced educational experiences and fostered discussion of alternative viewpoints and a “greater understanding of medical conditions and treatments for disease.” Gender diversity can increase the breadth of knowledge on research teams and add new perspectives.20 Woolley and colleagues21 demonstrated that in solving tests, teams of evenly mixed men and women tended to perform better than teams with mostly one sex. Therefore, boosting the representation of women and underrepresented minority physicians in cardiothoracic surgery has the potential to enhance patient care and innovation.

Without a concerted effort to engage in a culture of diversity and inclusion, the field of cardiothoracic surgery will suffer. In a study of surgical residents, 16.6% reported racial discrimination during training, and 65% of women in the same study reported sexual discrimination.22 Within the field of cardiothoracic surgery, the situation is even more dire. A study of cardiothoracic surgeons reported 81% to 90% of female surgeons experienced sexual harassment, most commonly from supervisors and colleagues.23 Interestingly, 23% to 46% of male surgeons in the same study experienced sexual harassment as well, but more commonly from ancillary staff and colleagues.

Cardiothoracic surgeons who are victims of or witness to harassment or discrimination can experience disengagement and burnout, and talented surgeons may find less enjoyment and meaning in their work. This dissatisfaction may cause physicians to change jobs or even leave the profession, resulting in a lost investment in training and development. Furthermore, our field will fail to attract a diverse population of competitive candidates as trainees are less likely to pursue a program that they perceive as lacking in diversity.24 Our environment also includes collaborating physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and staff. A hostile environment can harm recruitment, retention, and productivity of the entire healthcare team. The current environment within cardiothoracic surgery is a direct threat to the future growth of our specialty. It is crucial that steps be taken quickly to engage in diversity and a culture of inclusion.

What Can We Do as a Specialty?

Advancing diversity and inclusion within cardiothoracic surgery is a daunting but achievable endeavor. We begin this challenge by creating a framework in which diversity and inclusion are conceptualized as concentric spheres of influence. These spheres are global environment, the cardiothoracic community, institutional environment, and individual environment (Figure 1). This model is adapted from the socioecologic model developed by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.25 This adapted framework communicates that determinants at multiple levels create cultures of diversity and inclusion.

Figure 1.

Spheres of influence in cardiothoracic surgery with recommended interventions. (URM, underrepresented minorities.)

The largest sphere is the global environment, including national and regional context, patients, other specialties, the healthcare industry, and other industries. As cardiothoracic surgeons, we may not necessarily have influence in this sphere, but we can learn from advances in diversity and inclusion from other professions and industries. For example, the Pro Golf Association (PGA) of America recognized that a lack of candidate interest was their greatest barrier to recruiting underrepresented minorities and women.26 The PGA had to overcome a lack of exposure to underrepresented minorities and women and a perception that the field was inhospitable to these candidates. Therefore, the PGA developed a robust social media campaign featuring women and underrepresented minorities within the organization. Through this effort, the PGA successfully increased its diversity in personnel, and through its influence in the golf world, helped to spread diversity throughout the sport.27

Also, effective July 1, 2020, Goldman Sachs will only underwrite initial public offerings of private companies that have at least 1 board member of underrepresented background and plans to raise the target to 2 candidates in 2021.28 Understanding diversity and inclusion in the global environment, assessing where cardiothoracic surgery is in relation to other professions, and learning from experience of other professions are important first steps to inform the transformation of cardiothoracic surgery into a more diverse and inclusive profession.

The next sphere encompasses the cardiothoracic community. This includes our professional societies, such as the STS, American Association of Thoracic Surgery, Women in Thoracic Surgery (WTS), and Thoracic Surgery Directors Association. Within this sphere, there have been notable advances. The WTS has developed multiple scholarship programs to attract women medical students and residents to the field as well as promote continued career development of women cardiothoracic surgeons by focusing on mentorship and sponsorship.

In 2018, American Association of Thoracic Surgery in collaboration with WTS dedicated an entire class of its leadership academy to women in thoracic surgery.29 This conference focused on development of national and international networks of support for women seeking leadership positions within cardiothoracic surgery.

The STS developed the Workforce for Diversity and Inclusion in 2019 and has dedicated enduring funds to support diversity and inclusion at their national Annual Meeting.30 The program committee developed goals of diversity for the annual meeting and measures the number of women and underrepresented minority invited presenters and moderators. In 2020, more than 50% of sessions had at least 1 female moderator or chair, and more than 70% of sessions had at least 1 invited female panelist. To promote inclusion at the Annual Meeting, the STS designated lactation rooms for nursing attendees and a prayer/meditation room to support attendees from diverse religious backgrounds. Although not specifically targeting underrepresented minorities, the STS Looking to the Future Program has been successful in introducing medical students and general surgery residents to the specialty.31

To improve and expand on these initiatives, the cardiothoracic community must assess the current status of diversity and inclusion among surgeons and trainees, including a delineation of discrimination and harassment within our field. Informed by this assessment, the cardiothoracic community should develop a consensus statement of best practices to encourage diversity and a culture of inclusion. Furthermore, guidance from the cardiothoracic community on the prioritization of specialty-wide action is needed to achieve objectives such as pipeline programs, shared educational programs and training curricula, mitigation of discrimination, and shared metrics of diversity and inclusion.

The third sphere consists of institutions such as medical schools, health systems, and hospitals. Many institutions have existing infrastructure to encourage a culture of inclusion, but further evaluation of local resources should be done. For example, Temple University Health System’s Graduate Medical Education office, in collaboration with the Office of Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, developed strategies with program directors to increase underrepresented minority residents. Efforts included an educational presentation to program directors outlining the current status and goals for diversity in trainees and various programs to increase diversity.

One of these programs is a second-look opportunity for applicants to meet, network, socialize, and ask questions of current residents and faculty. Although all applicants could attend, applicants from self-identified underrepresented groups were eligible for a stipend to defray travel and housing costs. After 1 year of implementation, underrepresented minority trainees increased 3-fold.

Similarly, the Harvard Medical School Visiting Clerkship Program facilitates the participation of external underrepresented minority medical students in visiting clerkships at Harvard-affiliated hospitals. Over a 25-year period, 59% of participants have been women and 85% Black or Hispanic. In the entry survey, 49% of attendees stated they would apply to a Harvard-affiliated training program. In the exit survey, 73% said they would apply.32

Medical schools, health systems, and hospitals must also support their faculty who create and sustain these programs, particularly with resources, protected time, and consideration for promotion. Work at the institutional level to recruit, retain, and develop underrepresented minority and women faculty is needed. Cardiothoracic surgeons must catalog and assess resources within their practices, medical schools, and health systems. Evaluation of the institutional environment will identify areas of concern and provide insight into those areas to target for change efforts. Cardiothoracic surgeons should participate in or lead bias education and should assist in the mitigation of bias in recruitment and promotion and the development of metrics of diversity and inclusion within their own institutions. Cardiothoracic surgeons should also ask that their institutions value diversity efforts with protected time, resources, and credit toward promotion or career advancement.

The last sphere consists of individual cardiothoracic surgeons. This sphere includes our own personal conduct, as well as the teams we lead in the operating room, clinical practice, and education. A study by Duma and colleagues33 demonstrated that physicians are more likely to call female colleagues by first names only, whereas male colleagues are addressed by their professional title. When peer evaluations are given among cardiothoracic surgeons, Gerull and colleagues34 found surgeons consistently provide more positive evaluations and more favorable, “standout” words to describe men compared with women. Mindfulness of our conduct, even to the level of how we address our colleagues or evaluate our trainees, can impact our environment of inclusion. We can also assess our own implicit or unintentional biases with the Harvard Implicit Bias Assessment35 to reveal areas for future improvement at the personal level. To be an inclusive leader, we must understand common areas of bias in everyday practice, be aware of our own implicit or unintentional biases, act to minimize discrimination and bias, and ultimately advocate for a culture of inclusivity.36 At the individual level, cardiothoracic surgeons should assess their own conduct, explicit and implicit biases, and opportunities to act and advocate for diversity and inclusion. With this assessment, surgeons can then create personal interventions, such as education and advocacy efforts.

In a phenomenon called “the minority tax,”37 underrepresented minorities and female faculty often take on a disproportionate responsibility for mentoring, community outreach, and diversity efforts. These efforts are usually not valued as promotion-earning activities.38 The responsibility of promoting diversity and inclusion and mentoring young surgeons and trainees should be shared by all thoracic surgeons. In addition, all cardiothoracic surgeons should be encouraged to mentor people who do not look like them.39 To do this most effectively, mentors should assess their own implicit bias, educate themselves on cultural competency, and create an environment of diversity and inclusion among trainees, staff, and team members. Mentoring someone who does not look like you may be as simple as identifying the mentee’s professional needs, supporting them, and introducing them to one’s networking apparatus. Male surgeons should not neglect mentoring women during the #MeToo era but should exhibit common sense mentoring behavior identified by Byerley,40 including demonstrating professional behavior during and outside the workday, avoiding generalizing comments about gender, and “speaking up to support women.”

It is critical to understand that the various spheres of influence—global environment, cardiothoracic communities, institutions, and individual—are interrelated and dependent on each other. For example, pipeline programs to engage underrepresented minorities and women as undergraduates and in medical school is a priority of STS. These pipeline initiatives will fail in fostering diversity and inclusion if institutions or individuals have inherent bias against underrepresented minorities and/or women in recruitment or promotion. A focus of effort into only one sphere will result in an incomplete and ineffective change. These spheres, when linked and providing complementary support, will help organize researchers, leaders, and individuals who aspire to improve diversity and inclusion in cardiothoracic surgery.

This model organizes an approach to diversity and inclusion, both for implementation and future research. Within each sphere, assessments of where we stand, interventions to improve diversity and inclusion, and the metrics by which we can measure progress are all desperately needed. Systems of accountability must also be developed to ensure sustainability of diversity practices. Furthermore, study of the interdependence of the spheres is essential. For example, mentorships can develop in every sphere—across professions and specialties, within the cardiothoracic community, within an institution, or at an interpersonal level. This framework may inform future study of how best to mentor women and underrepresented minorities by using interventions at different levels to greater effect.

Conclusions

As the US population continues to diversify, there is an imminent need to increase diversity and inclusion within cardiothoracic surgery for the purpose of social justice, patient care, innovation, research, and the relevance of our field. Increasing diversity and fostering an environment of inclusivity may be a daunting endeavor, but it is one we can accomplish together. We propose a multilevel approach (global, cardiothoracic community, institutional, and individual) to develop meaningful practices to promote diversity. With this organizational framework, cardiothoracic surgery can effectively assess, improve, and sustain a culture of inclusion.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Temple University Fox Chase Cancer Center and Hunter College Regional Comprehensive Cancer Health Disparity Partnership, award number U54 CA221704(5) (contact primary investigators: Grace X. Ma, PhD, and Olorunseun O. Ogunwobi, MD, PhD) from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Krogstad JM. Reflecting a demographic shift, 109 U.S. counties have become majority nonwhite since 2000. Pew Research Center. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/08/21/u-s-counties-majority-nonwhite. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 2.Sullivan Commission on Diversity in the Healthcare Workforce. Missing Persons: Minorities in the Health Professions. The Sullivan Commission, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. QuickFacts: United States. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120218. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 18. Percentage of all active physicians by race/ethnicity, 2018. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures 2019. Figure 12. Percentage of U.S. medical school graduates by sex, academic years 1980–1981 through 2018–2019. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-12-percentage-us-medical-school-graduates-sex-academic-years-1980-1981-through-2018-2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 6.Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report. Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2017. Available at https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2017. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 7.Abelson JS, Symer MM, Yeo HL, Butler PD, Dolan PT, Moo TA, et al. Surgical time out: our counts are still short on racial diversity in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2018;215:542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler PD, Longaker MT, Britt LD. Major deficit in the number of underrepresented minority academic surgeons persists. Ann Surg. 2008;248:704–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels EW, French K, Murphy LA, Grant RE. Has diversity increased in orthopaedic residency programs since 1995? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2319–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woo K, Kalata EA, Hingorani AP. Society of Vascular Surgery Diversity and Inclusion Committee. Diversity in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:1710–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siotos C, Payne RM, Stone JP, et al. Evolution of workforce diversity in surgery. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shemin RJ, Ikonomidis JS. Thoracic surgery workforce: report of STS/AATS Thoracic Surgery Practice and Access Task Force—snapshot 2010. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:39–46. e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stephens EH, Robich MP, Walters DM, et al. Gender and cardiothoracic surgery training: specialty interests, satisfaction, and career pathways. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:200–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:997–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moy E, Bartman BA. Physician race and care of minority and medically indigent patients. JAMA. 1995;273:1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marrast L, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen MW, Alegria S, Borjesön L, et al. Opinion: gender diversity leads to better science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:1740–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolley AW, Chabris CF, Pentland A, Hashmi N, Malone TW. Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science. 2010;330:686–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1741–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceppa DP, Dolejs SC, Boden N, et al. Sexual harassment and cardiothoracic surgery: #UsToo? Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109: 1283–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auseon AJ, Kolibash AJ, Capers Q. Successful efforts to increase diversity in a cardiology fellowship training program. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:481–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvidrez J, Castille D, Laude-Sharp M, Rosario A, Tabor D. The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(Suppl 1):S16–S20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cross S, Braswell P. A Data-Driven Approach to Hiring More Diverse Talent. Harvard Business Review. December 10; 2019. Available at: https://hbr.org/2019/12/why-isnt-your-organization-isnt-hiring-diverse-talent. Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 27.PGA Impact. Fostering Inclusion & Diversity 2019. Available at: https://pgaimpact.org/fostering-diversity-inclusion/. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 28.Goldman Sachs. Goldman Sachs’ Commitment to Board Diversity. February 4, 2020. Available at: https://www.goldmansachs.com/what-we-do/investing-and-lending/launch-with-gs/pages/commitment-to-diversity.html. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 29.Women in Thoracic Surgery. AATS Collaboration with Women in Thoracic Surgery for the 2018 AATS Leadership Academy. Available at: https://wtsnet.org/career-development/2018-aats-leadership-academy/. Accessed April 10, 2020.

- 30.Cooke DT, Olive J, Godoy L, Preventza O, Mathisen DJ, Prager RL. The importance of a diverse specialty: introducing the STS Workforce on Diversity and Inclusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:1000–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reddy RM, Kim AW, Cooke DT, Yang SC, Vaporciyan A, Higgins RSD. The Looking to the Future Medical Student Program: recruiting tomorrow’s leaders. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:741–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visiting Clerkship Program 25th (VCP25) Anniversary Celebration. Available at: https://dicp.hms.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/files/2015/VCP/VCP25/VCP25_programbook.pdf. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 33.Duma N, Durani U, Woods CB, et al. Evaluating unconscious bias: speaker introductions at an international oncology conference. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3538–3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerull KM, Loe M, Seiler K, McAllister J, Salles A. Assessing gender bias in qualitative evaluations of surgical residents. Am J Surg. 2019;217:306–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97:17–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown J How to Be an Inclusive Leader: Your Role in Creating Cultures of Belonging Where Everyone Can Thrive. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25: 1363–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rockquemore KA. Can I Mentor African-American Faculty? Inside Higher Ed. February 17, 2016. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2016/02/17/advice-white-professor-about-mentoring-scholars-color-essay. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 40.Byerley JS. Mentoring in the era of #MeToo. JAMA. 2018;319: 1199–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]