Abstract

Bats dispersed widely after evolving the capacity for powered flight, and fossil bats are known from the early Eocene of most continents. Until now, however, bats have been conspicuously absent from the early Eocene of mainland Asia. Here, we report two teeth from the Junggar Basin of northern Xinjiang, China belonging to the first known early Eocene bats from Asia, representing arguably the most plesiomorphic bat molars currently recognized. These teeth combine certain bat synapomorphies with primitive traits found in other placental mammals, thereby potentially illuminating dental evolution among stem bats. The Junggar Basin teeth suggest that the dentition of the stem chiropteran family Onychonycteridae is surprisingly derived, although their postcranial anatomy is more primitive than that of any other Eocene bats. Additional comparisons with stem bat families Icaronycteridae and Archaeonycteridae fail to identify unambiguous synapomorphies for the latter taxa, raising the possibility that neither is monophyletic as currently recognized. The presence of highly plesiomorphic bats in the early Eocene of central Asia suggests that this region was an important locus for the earliest, transitional phases of bat evolution, as has been demonstrated for other placental mammal orders including Lagomorpha and Rodentia.

Keywords: bat evolution, Bumbanian, Junggar Basin, Onychonycteridae, Archaeonycteridae, Icaronycteridae

1. Introduction

Bats have a notoriously poor fossil record [1,2], despite being among the most widespread and speciose living mammals. The oldest fossil bats date to the early Eocene and are recognized from Africa [3–5], Australia [6], Europe [7–10], North America [11–13], South America [14] and the Indian subcontinent [15,16] (figure 1). Most of these taxa are represented by isolated teeth and jaw fragments, with only a few species known from relatively complete skeletons. The oldest fragmentary bat dentitions date to the earliest Eocene [6,7], whereas the most primitive bat documented by skeletal remains, Onychonycteris finneyi, dates to younger late early Eocene sediments [13]. The oldest bats previously known from mainland Asia are from the middle Eocene of Jiangsu, Henan, and Shanxi provinces, China [17,18]. Despite their nearly cosmopolitan distribution by the early Eocene, molecular analyses uniformly support an origin for bats on one of the northern continents—Asia, Europe or North America—as members of the superorder Laurasiatheria [19–21]. As laurasiatherians, bats are closely related to such orders as Perissodactyla, Carnivora and Cetartiodactyla, for which a Laurasian origin is generally acknowledged [22,23]. The absence of early Eocene bats in Asia, however, is striking in light of their laurasiatherian relationships and apparent rapid dispersal to such far flung continents as Australia and South America. Additionally, relationships among bats and other laurasiatherians are unsettled [21,24,25], obscuring the identification of unambiguously primitive characters among bats.

Figure 1.

Map showing localities of early Eocene bat fossils: (1) Wind River Formation, Wyoming, USA; (2) Green River Formation, Wyoming, USA; (3) Laguna Fría, Chubut, Argentina; (4) Silveirinha, Portugal; (5) Abbey Wood, England; (6) Mutigny, Pourcy, Avenay, Meudon, and Prémontré, France; Egem and Evere, Belgium; (7) Fournes and Fordones, France; (8) El Kohol, Brezina, Algeria; (9) Chambi, Kasserine, Tunisia; (10) Vastan, Gujarat, India; (11) Murgon, Queensland, Australia (12) Junggar Basin; Xinjiang, China. Dark grey depicts the position of continents during the early Eocene, light grey depicts position of continental shelf and epicontinental seas. Insets depict M1 morphology of basal bats (a) Icaronycteris index (Icaronycteridae), (b) Archaeonycteris brailloni (Archaeonycteridae), (c) Ageina tobieni (Onychonycteridae), (d) Altaynycteris aurora (family incertae sedis). Ectoflexus indicated with (E), lingual cingulum indicated with (L), and hook-shaped parastyle indicated with (P). Palaeogeography adapted from Ron Blakey (Northern Arizona University).

These factors highlight two key deficiencies in our knowledge of early bat evolution: a morphological gap, in which transitional fossils linking bats with other closely related placental mammals remain unknown; and a biogeographical gap, whereby early Eocene bats are recognized from nearly all continental landmasses except Asia, despite the strong likelihood that bats inhabited Asia during the early Eocene and may well have originated there [26]. The first deficiency is exacerbated by the large morphological disparity between bats and their closest living relatives, hindering efforts to identify plesiomorphic characters in bats. The second deficiency is complicated by the fact that bats are volant and appear to have dispersed virtually worldwide shortly after their evolution, obscuring any potential Laurasian signal with respect to their region of origin. The discovery of primitive bat fossils from the early Eocene of central Asia illuminates both of these deficiencies.

Here, we report two upper molars from the Junggar Basin in central Asia, which rank among the oldest and most primitive bats in the world. These teeth possess a set of plesiomorphic features that address gaps in our understanding of the morphology and biogeography of the earliest bats. The Junggar Basin bats combine apparent bat synapomorphies with basal eutherian symplesiomorphies, many of which are not observed in other stem bats. This unique amalgamation of characters furthers our knowledge of the early dental evolution of bats. Biogeographically, the presence of primitive stem chiropterans in the Junggar Basin raises the possibility of bat origins in the Paratethyan realm of central Asia.

Institutional Abbreviations—IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing, China.

2. Locality and age

The fossils described here were sorted from screen-washed residue collected from the early Eocene Red Rodent locality in the Gurbantunggut Desert, northeastern Junggar Basin, Xinjiang Province, China. This locality is approximately 20 km northwest of the South Gobi locality, where a diverse late Palaeocene vertebrate fauna occurs [27]. Palaeogene strata in the northeastern Junggar Basin belong to an unnamed lithological unit, consisting of reddish-brown mudstones interbedded with greyish-green fluvial sandstones. A reddish-brown sandy mudstone occurs in the middle of this unit, containing abundant gypsum crystals. This gypsum bed is approximately 10 m thick and can be traced laterally over tens of kilometres. The South Gobi fauna, which has been tentatively correlated with Gashatan faunas on the Mongolian Plateau and Clarkforkian faunas in North America [27], occurs below this gypsum bed. Fossils from the Red Rodent locality occur in a reddish-brown palaeosol containing abundant calcareous concretions approximately 2 m above the laterally persistent gypsum bed. In addition to the new bat reported here, taxa from the Red Rodent locality include Advenimus hubeiensis, Tamquammys robustus, Hyposodus sp. and Erlianomys cf. combinatus. These mammals typify the Bumbanian [28,29], and probably correlate to the first approximately 1 million years of the Eocene [28,30].

3. Systematic palaeontology

Chiroptera Blumenbach, 1779

Family incertae sedis

Altaynycteris aurora gen. et. sp. nov.

Etymology. The generic name refers to Altay Prefecture in northern Xinjiang and the nearby Altai Mountains, and -nycteris after the Greek nykteris, a common suffix for bats. The specific epithet is Latin for ‘dawn’, an allusion to the early Eocene age of this fossil.

Holotype. Left M1, IVPP V27157 (figure 2a–c)

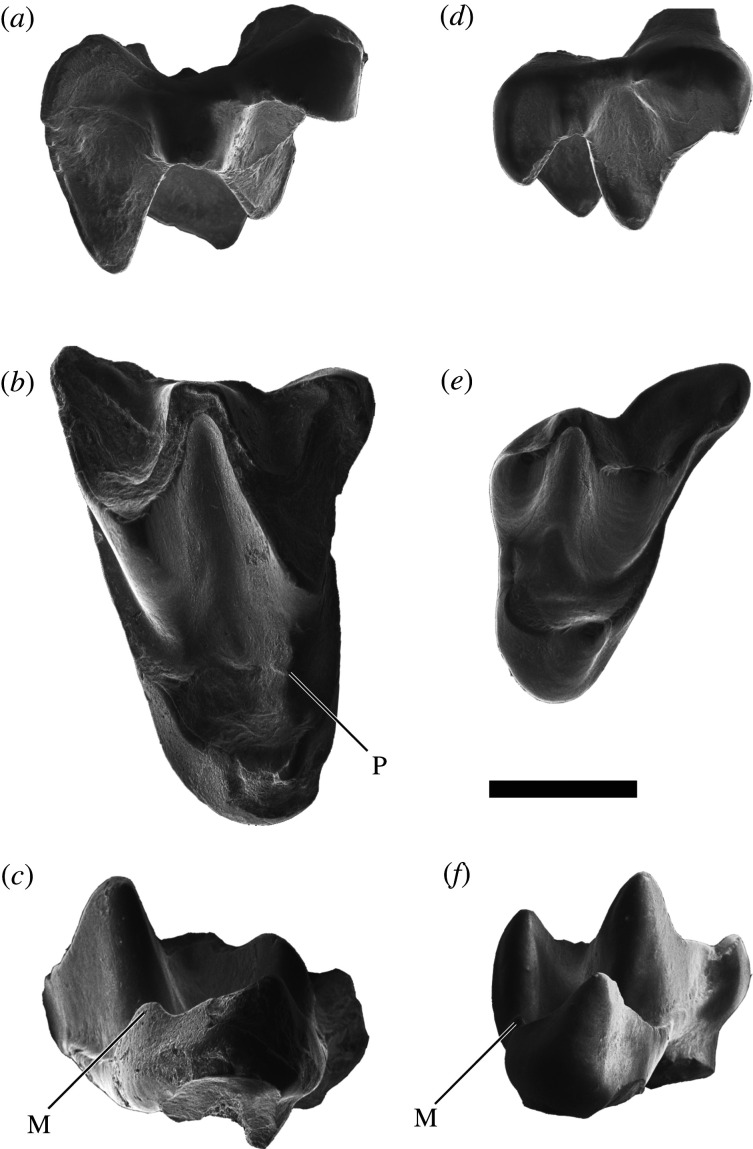

Figure 2.

Upper molars of Altaynycteris aurora. IVPP V27157, holotype right M1, in buccal (a), occlusal (b) and lingual view (c); IVPP V27158, right M3, in buccal (d), occlusal (e) and lingual view (f). Metaconule indicated with (M) and postparaconule crista indicated with (P). Scale bar is 0.5 mm.

Referred material. Right M3, IVPP V27158 (figure 2d–f)

Type locality and horizon. Red Rodent locality (XJ20160615LQ04), Xinjiang, China; early Eocene.

Diagnosis. Upper molars differ from those of other early and middle Eocene bats in the following ways: from Onychonycteridae in being more transverse and triangular and from Icaronycteridae, Archaeonycteridae and Hassianycteridae in lacking a talon; further differ from Icaronycteridae in lacking complete or partial lingual cingulum, from Archaeonycteridae in lacking a deep ectoflexus and in possessing a metaconule; and from Palaeochiropterygidae in lacking paired, acute ectoflexi and a strongly hooked parastyle. Upper molars differ from those of Vespertiliavus, Tachypteron, Necromantis, Hipposideros, Palaeophyllophora and Mixopterygidae in lacking a talon; further differs from Necromantis in lacking an ectoflexus and from Mixopterygidae in lacking a mesostyle, and differs from Dizzya in lacking an anteroposteriorly elongate postprotocrista and complete lingual cingulum.

Description and remarks. IVPP V27157 (figure 2a–c) is considered as M1 rather than M2 based on the asymmetry of its buccal margin, whereby the metastylar region projects more buccally than the parastylar region. The tooth is transversely elongate (length: 1.13 mm, width: 1.85 mm), with a pronounced W-shaped ectoloph, a distinct metaconule on the postprotocrista and a weak swelling of enamel in the position of a paraconule and postparaconule crista. There is no lingual cingulum, hypocone or pericone and the mesostyle may also be absent, although the latter is obscured by wear. The anterior and buccal sides of the paracone are heavily worn, as are the buccal margin of the metacone and associated cristae. The lingual margin of the protocone is also abraded. The preparacrista is heavily worn, but appears to terminate in a weakly hooked parastyle. The postmetacrista projects farther buccally than the parastyle and centrocrista. The protocone is lingually canted and much lower than the paracone and metacone. A crestiform metaconule is present on the postprotocrista, posterolingual to the metacone. A weak premetaconule crista extends from the metaconule toward the trigon basin.

IVPP V27158 (figure 2d–f) is triangular in shape (length: 0.88 mm, width: 1.23 mm) and lacks a postmetacrista. The preparacrista is the longest of the primary cristae, which progressively decrease in length toward the distal margin. The postparacrista and premetacrista join on the buccal margin of the tooth at a shallow angle (less than 30°). The parastyle lacks the hook shape typical of Eocene bats. The paracone is taller and more massive than the metacone, and positioned slightly more lingually. IVPP V27158 lacks a mesostyle and paraconule, but possesses a distinct metaconule on the postprotocrista and a weak ectoflexus distobuccal to the paracone. Neither talon nor hypocone is present, and there is no trace of a lingual cingulum.

We identify these teeth as belonging to Chiroptera due to the presence of a suite of characters present in most primitive bats, the combination of which does not appear in other Eocene mammals, including dilambdodont molars with paracone and metacone shifted strongly lingually; narrow, tapering trigon that is closed buccally by elevated centrocrista, absence of a mesostyle, large stylar shelf, similarly sized primary cristae, and exaggerated parastylar and metastylar fovea (for a more detailed analysis of primitive upper molar characters in bats, see [31]). These specimens are referred to the same taxon due to such characters as a pronounced metaconule, weak parastyle and lack of a lingual cingulum.

Differences between Altaynycteris aurora and other early Eocene bats generally highlight the primitive nature of the former. Distinct conules are observed in a number of early therian mammals [32–34], and their loss in most bats has been interpreted as a synapomorphy [6]. A complete or partial lingual cingulum is observed in other Eocene stem bats [31] and may also be a synapomorphy of bats more derived than Altaynycteris.

4. Discussion

(a) . Dental characteristics of archaic bats

Unambiguously plesiomorphic characters of chiropteran dentition are difficult to determine due to uncertainty regarding their closest living and fossil relatives. Most stem bats possess dilambdodont upper molars without mesostyles that either lack conules altogether or retain small conules [31]. Comparisons to potential outgroups including eulipotyphlans and basal eutherians suggest potential upper molar characters of the transitional chiropteran, including the absence of a complete lingual cingulum or well-developed talon region (although some of those taxa possess variably developed hypocones) and transversely elongate teeth with distinct conules [32,35–37] (table 1). Altaynycteris combines primitive characters that are missing in most stem and crown bats (e.g. retention of conules, absence of a lingual cingulum) and obvious bat synapomorphies (e.g. large stylar shelf, lack of a mesostyle), suggesting that it occupies an unusually basal position within Chiroptera.

Table 1.

Upper molar characters observed in Altaynycteris aurora; stem bat families Palaeochiropterygidae (Palaeochiropteryx, Lapichiropteryx, Stehlinia), Hassianycteridae (Hassianycteris), Archaeonycteridae (Archaeonycteris), Icaronycteridae (Icaronycteris) and Onychonycteridae (Onychonycteris, Honrovits, Ageina); and dentally unspecialized eutherian outgroups, including Mesozoic eutherians (Eomaia, Juramaia, Maelestes; [32–34]), Palaeocene stem placentals Adapisoriculidae (Afrodon, Bustylus, Proremiculus [35,36]), Cimolestidae (Altacreodus, Ambilestes, Scollardius [38]), Leptictidae (Prodiacodon [39]) and putative Palaeocene laurasiatheres Nyctitheriidae (Leptacodon [40,41]).

| trigon shape | Ectoflexus | Lingual cingulum | Talon expansion | Paraconule | Metaconule | Hypocone | references | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palaeochiropterygidae | transversely elongate | present and acute | incomplete or complete | present | absent | small or absent | absent | [42,43] |

| Hassianycteridae | transversely elongate | absent | complete | present | absent | absent | weak or absent | [42,44] |

| Archaeonycteridae | transversely elongate | present | complete | present or absent | present or absent | absent | absent | [42,45] |

| Icaronycteridae | transversely elongate | present | incomplete or complete | present | absent | small or absent | present (M1) | [42,46] |

| Onychonycteridae | squared | weak or absent | incomplete or complete | present | present | small or absent | absent | [42] |

| Altaynycteris | transversely elongate | absent | absent | absent | crista present | present | absent | This paper |

| Chiroptera common ancestor | transversely elongate | indeterminate | absent | weak or absent | present | present | absent | This paper |

| Mesozoic eutherians | transversely elongate | present | absent | absent | present | present | absent or present | [32–34] |

| Leptictidae | transversely elongate | weak or absent | absent | weak | present | present | weak or absent | [39] |

| Adapisoriculidae | transversely elongate or squared | weak | absent | weak or absent | present | present | absent | [35,36] |

| Cimolestidae | transversely elongate | absent or present | absent | absent | present | present | absent | [38] |

| Nyctitheriidae | transversely elongate | absent or present | absent | weak to pronounced | present | present | weak or absent | [40,41] |

The most postcranially primitive chiropteran family currently recognized, Onychonycteridae, is characterized by comparatively square-shaped upper molars with shallow ectoflexi and a centrocrista that does not extend to the buccal margin [42]. Excluding the lack of an ectoflexus in hassianycterids, none of these conditions is present in other stem bat taxa and some or all of them may be derived. Thus, Onychonycteridae likely do not represent the most basal clade of bats when considering fossils known only from dentition. Icaronycteridae, the next most basal recognized clade, is characterized by only plesiomorphic dental features [42,47] including anteroposteriorly narrow upper molars without a mesostyle but with a centrocrista contacting the buccal margin and relatively well-developed ectoflexi. These traits are shared with nearly all other stem bats excluding Onychonycteridae. Most stem bats possess a weakly developed talon and/or lingual cingulum [31], and in some (e.g. Palaeochiropteryx tupaiodon), the talon can be relatively distinct.

Altaynycteris is notable in being defined almost entirely by plesiomorphic features, as in Icaronycteridae. IVPP V27157 shares with Onychonycteridae and Hassianycteridae a very weak ectoflexus and is unique among stem bats in lacking any development of a talon and/or lingual cingulum. The presence of both conules on IVPP V27157 is unusual, as only Archaeonycteridae and some Onychonycteridae possess a small paraconule and only Palaeochiropterygidae and some Onychonycteridae have a small metaconule among stem bats [42]. The presence of both in Altaynycteris is likely primitive. We declined to undertake a formal phylogenetic analysis of Altaynycteris because of its limited anatomical documentation. However, its upper molar morphology closely resembles that of the hypothesized ancestral chiropteran (table 1). Future collecting in the Junggar Basin will hopefully enable a more thorough analysis of the phylogenetic position of these bats.

If Altaynycteris is, indeed, among the most plesiomorphic bats known, it provides valuable insight into potential synapomorphies of early stem families Onychonycteridae, Icaronycteridae and Archaeonycteridae. Onychonycteridae appears to be characterized by clear synapomorphies, including comparatively square-shaped upper molars with expanded protocones and a centrocrista that does not reach the buccal margin of the tooth. Icaronycteridae are characterized primarily by plesiomorphic features, but all possess an ectoflexus, a weakly developed talon on at least one molar and a complete lingual cingulum on M2. Archaeonycterid upper molars possess these same characters but additionally preserve a rudimentary paraconule. Due to their characterization by presumed plesiomorphies, the strict monophyly of both Icaronycteridae and Archaeonycteridae remains dubious [42,48].

(b) . A possible Central Asian origin for bats

Few previous authors have speculated on the region of origin of bats in the light of their laurasiatherian relationships. Sigé et al. [49] suggested an origin in North America, with dispersal toward Europe and Africa via the North Atlantic, Asia via Beringia, and Australia via South America and Antarctica. Teeling et al. [50] also suggested a possible North American origin for bats, possibly due to the presence of Icaronycteris index from Wyoming as the most basal taxon in their analysis. The most postcranially primitive bats are known from North America, but Onychonycteris finneyi and Icaronycteris index are approximately three million years younger than the earliest known bats [6,7,13,51–53]. Additionally, other onychonycterids and icaronycterids are now recognized from the early Eocene of Europe and India, suggesting that the North American species may not be especially primitive relative to older bats on other continents.

Bats almost certainly arose during the Palaeocene due to their wide geographic distribution in the earliest Eocene [49]. Molecular analyses generally support a Palaeocene origin for Chiroptera [21,50], and genomic data indicate that bats are part of the large and diverse laurasiatherian clade that is clearly rooted in the northern continents. The late Palaeocene records of western North America and the Paris Basin in Europe are reasonably well-sampled, yet bats remain unknown there [12]. Yu et al. [26] suggested an Asian origin for bats based on ancestral area reconstructions of extant taxa. Central Asia, then, presents an intriguing opportunity to investigate bat origins. Numerous other mammalian orders are hypothesized to have originated in Asia, including Cetartiodactyla, Lagomorpha, Perissodactyla, Primates and Rodentia (e.g. [22,23]).

Bats are now known from the earliest Eocene of Asia—making them as old or older than their earliest occurrences in Europe and North America—and Altaynycteris retains plesiomorphic characters likely shared with the common ancestor of Chiroptera. The absence of clearly derived upper molar traits (e.g. lingual cingulum, talon, hook-shaped parastyle) suggests that Altaynycteris is among the most primitive bats known. The most postcranially primitive taxon, Onychonycteris finneyi, exhibits comparatively derived dental morphology. Altaynycteris aurora, along with such European taxa as Archaeonycteris? praecursor, may represent earlier diverging lineages due to their dearth of derived characters and retention of plesiomorphic traits. Prior to the acquisition of powered flight, transitional bats almost certainly would have possessed a limited geographic range. The primitive upper molar morphology of Altaynycteris makes it an intriguing candidate for such a transitional stage. Corroboration of this hypothesis will require additional anatomical data, especially from the postcranial skeleton, and an improved phylogenetic framework. Although the earliest Eocene of Europe and North America has been intensively sampled for more than a century [54], the Palaeogene of central Asia remains comparatively poorly studied. Thus, the early Palaeogene of central Asia represents a promising region to investigate bat origins and from which to understand their rapid diversification and dispersal.

Acknowledgements

Drs Grégoire Métais, Łucja Fostowicz-Frelik, Thomas Stidham and Yangheshan Yang attended the fieldwork. Ming Hao and Yongchun Yang helped in the field. Guizhen Wang and Ran Li sorted the screenwashing concentrates. Kristen Tietjen assisted in drafting the figures. We thank two anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xijun Ni, Email: nixijun@ivpp.ac.cn.

K. Christopher Beard, Email: chris.beard@ku.edu.

Data accessibility

All relevant data are included in the table 1, section ‘Locality and age’, and section ‘Systematic palaeontology’.

Authors' contributions

X.N. and K.C.B. organized the project. M.F.J., Q.L., X.N. and K.C.B. conducted fieldwork. L.Q. and X.N. measured and imaged the specimens. M.F.J. and K.C.B. described the specimens and drafted the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript, approved the final version and agree to be held accountable for the content.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This project has been supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant nos. CAS XDB26030300, XDA20070203 and XDA19050100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 41888101, 41988101 and 41625005), the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Program (2019QZKK0705) and the David B. Jones Foundation.

References

- 1.Eiting TP, Gunnell GF. 2009. Global completeness of the bat fossil record. J. Mamm. Evol. 16, 151-173. ( 10.1007/s10914-009-9118-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown EE, Cashmore DD, Simmons NB, Butler RJ. 2019. Quantifying the completeness of the bat fossil record. Palaeontology 62, 757-776. ( 10.1111/pala.12426) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravel A, Marivaux L, Tabuce R, Adaci M, Mahboubi M, Mebrouk F, Bensalah M. 2011. The oldest African bat from the early Eocene of El Kohol (Algeria). Naturwissenschaften 98, 397-405. ( 10.1007/s00114-011-0785-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravel A, Marivaux L, Tabuce R, Ben Haj Ali M, Essid EM, Vianey-Liaud M. 2012. A new large philisid (Mammalia, Chiroptera, Vespertilionoidea) from the late early Eocene of Chambi, Tunisia. Palaeontology 55, 1035-1041. ( 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01160.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravel A, et al. 2014. New philisids (Mammalia, Chiroptera) from the early–middle Eocene of Algeria and Tunisia: new insight into the phylogeny, palaeobiogeography and palaeoecology of the Philisidae. J. Syst. Paleontol. 13, 691-709. ( 10.1080/14772019.2014.941422) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hand S, Novacek M, Godthelp H, Archer M. 1994. First Eocene bat from Australia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 14, 375-381. ( 10.1080/02724634.1994.10011565) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabuce R, Antunes MT, Sigé B. 2009. A new primitive bat from the earliest Eocene of Europe. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 29, 627-630. ( 10.1671/039.029.0204) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hand SJ, Sigé B, Archer M, Gunnell GF, Simmons NB. 2015. A new early Eocene (Ypresian) bat from Pourcy, Paris Basin, France, with comments on patterns of diversity in the earliest chiropterans. J. Mamm. Evol. 22, 343-354. ( 10.1007/s10914-015-9286-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hand S, Sigé B, Archer M, Black K. 2016. An evening bat (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) from the late early Eocene of France, with comments on the antiquity of modern bats. Palaeovertebrata 40, e2. ( 10.18563/pv.40.2.e2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooker JJ. 1996. A primitive emballonurid bat (Chiroptera, Mammalia) from the earliest Eocene of England. Palaeovertebrata 25, 287-300. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beard KC, Sigé B, Krishtalka L. 1992. A primitive vespertilionoid bat from the early Eocene of central Wyoming. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, Serie II 314, 735-741. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jepsen GL. 1966. Early Eocene bat from Wyoming. Science 154, 1333-1339. ( 10.1126/science.154.3754.1333) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons NB, Seymour KL, Habersetzer J, Gunnell GF. 2008. Primitive early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation. Nature 451, 818-821. ( 10.1038/nature06549) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tejedor MF, Czaplewski NJ, Goin FJ, Aragon E. 2005. The oldest record of South American bats. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 25, 990-993. ( 10.1671/0272-4634%282005%29025%5B0990%3ATOROSA) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rana RS, Singh H, Sahni A, Rose KD, Saraswati PK. 2005. Early Eocene chiropterans from a new mammalian assemblage (Vastan Lignite Mine, Gujarat, Western Peninsular Margin): oldest known bats from Asia. J. Palaeontol. Soc. India 50, 93-100. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith T, Rana RS, Missiaen P, Rose KD, Sahni A, Singh H, Singh L. 2007. High bat (Chiroptera) diversity in the early Eocene of India. Naturwissenschaften 94, 1003-1009. ( 10.1007/s00114-007-0280-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong Y. 1997. Middle Eocene small mammals from Liguanqiao Basin of Henan Province and Yuanqu Basin of Shanxi Province, central China. Palaeontol. Sinica 18, 1-256. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravel A, Marivaux L, Qi T, Wang Y-Q, Beard KC. 2014. New chiropterans from the middle Eocene of Shanghuang (Jiangsu Province, coastal China): new insight into the dawn horseshoe bats (Rhinolophidae) in Asia. Zool. Scripta 43, 1-23. ( 10.1111/zsc.12027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Springer MS, Stanhope MJ, Madsen O, de Jong WW.. 2004. Molecules consolidate the placental mammal tree. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 430-438. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2004.05.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Springer MS, Meredith RW, Janecka JE, Murphy WJ. 2011. The historical biogeography of Mammalia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 2478-2502. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amador LI, Arévalo RLM, Almeida FC, Catalano SA, Giannini NP. 2018. Bat systematics in the light of unconstrained analyses of a comprehensive molecular supermatrix. J. Mamm. Evol. 25, 37-70. ( 10.1007/s10914-016-9363-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beard KC. 1998. East of Eden: Asia as an important center of taxonomic origination in mammalian evolution. Bull. Carnegie Mus. Nat. Hist. 34, 5-39. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen GJ, Clyde WC, Koch PL, Ting S, Alroy J, Tsubamoto T, Wang Y, Wang Y. 2002. Mammalian dispersal at the Paleocene/Eocene boundary. Science 295, 2062-2065. ( 10.1126/science.1068700) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Xu S, Xu J, Chen B, Zhou K, Yang G. 2012. Phylogenomic analysis resolves the interordinal relationships and rapid diversification of the laurasiatherian mammals. Syst. Biol. 61, 150-164. ( 10.1093/sysbio/syr089) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nery MF, Gonzalez DJ, Hoffmann FG, Opazo JC. 2012. Resolution of the laurasiatherian phylogeny: evidence from genomic data. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 64, 685-689. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2012.04.012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu W, Wu Y, Yang G. 2014. Early diversification trend and Asian origin for extent bat lineages. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 2204-2218. ( 10.1111/jeb.12477) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ni X, Li Q, Stidham TA, Li L, Lu X, Meng J. 2016. A late Paleocene probable metatherian (? deltatheroidan) survivor of the Cretaceous mass extinction. Sci. Rep. 6, 38547. ( 10.1038/srep38547) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Q, Meng J. 2015. New ctenodactyloid rodents from the Erlian Basin, Nei Mongol, China, and the phylogenetic relationships of Eocene Asian ctenodactyloids. Am. Mus. Novitates 3828, 1-20. ( 10.1206/3828.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong Y, Wang Y, Li Q. 2006. Subdivision of the Paleogene in Lingcha area of Hunan Province and early Eocene mammalian faunas of China. Geol. Rev. 52, 153-162. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q. 2016. Eocene fossil rodent assemblages from the Erlian Basin (Inner Mongolia, China): biochronological implications. Palaeoworld 25, 95-103. ( 10.1016/j.palwor.2015.07.001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simmons NB, Seiffert ER, Gunnell GF. 2016. A new family of large omnivorous bats (Mammalia, Chiroptera) from the late Eocene of the Fayum Depression, Egypt, with comments on use of the name ‘Eochiroptera’. Am. Mus. Novitates 3857, 1-43. ( 10.1206/3857.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wible JR, Rougier GW, Novacek MJ, Asher RJ. 2009. The eutherian mammal Maelestes gobiensis from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia and the phylogeny of Cretaceous Eutheria. Bullet. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 327, 1-123. ( 10.1206/623.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ji Q, Luo Z-X, Yuan C-X, Wible JR, Zhang J-P, Georgi JA. 2002. The earliest known Eutherian mammal. Nature 416, 816-822. ( 10.1038/416816a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo Z-X, Yuan C-X, Meng Q-J, Ji Q. 2011. A Jurassic eutherian mammal and divergence of marsupials and placentals. Nature 476, 442-445. ( 10.1038/nature10291) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gheerbrant E, Russell DE. 1989. Presence of the genus Afrodon Mammalia, Lipotyphla (?), Adapisoriculidae. in Europe; new data for the problem of trans-Tethyan relations between Africa and Europe around the K/T boundary. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 76, 1-15. ( 10.1016/0031-0182(89)90099-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Bast E, Sigé B, Smith T. 2012. Diversity of the adapisoriculid mammals from the early Palaeocene of Hainin, Belgium. Acta Palaeontol. Polonica 57, 35-52. ( 10.4202/app.2010.0115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopatin AV. 2006. Early Paleogene insectivore mammals of Asia and establishment of the major groups of Insectivora. Paleontol. J. 40, S205-S405. ( 10.1134/S0031030106090012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox RC. 2015. A revision of the Late Cretaceous–Paleocene eutherian mammal Cimolestes Marsh, 1889. Can. J. Earth Sci. 52, 1137-1149. ( 10.1139/cjes-2015-0113) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clemens WA. 2015. Prodiacodon crustulum (Leptictidae, Mammalia) from the Tullock Member of the Fort Union Formation, Garfield and McCone Counties, Montana, USA. PaleoBios 32, 1-17. ( 10.5070/P9321025382) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Secord R. 2008. The Tiffanian land-mammal age (middle and late Paleocene) in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Univers. Michigan Pap. Paleontol. 35, 1-192. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenna MC. 1968. Leptacodon, an American Paleocene nyctithere (Mammalia, Insectivora). Am. Mus. Novitates 2317, 1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith T, Habersetzer J, Simmons NB, Gunnell GF. 2012. Systematics and paleobiogeography of early bats. In Evolutionary history of bats: fossils molecules and morphology (eds Gunnell GF, Simmons NB), pp. 23-66. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maitre E. 2014. Western European middle Eocene to early Oligocene Chiroptera: systematics, phylogeny and palaeoecology based on new material from the Quercy (France). Swiss J. Palaeontol. 133, 141-242. ( 10.1007/s13358-014-0069-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith JD, Storch G. 1981. New middle Eocene bats from ‘Grube Messel’ near Darmstadt, W-Germany (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Senckenbergiana Biol. 61, 153-167. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunnell GF, Habersetzer J, Schlosser-Sturm E, Simmons NB, Smith T. 2011. Primitive chiropteran teeth: the complete dentition of the Messel bat Archaeonycteris trigonodon. In The world at the time of Messel: puzzles in palaeobiology, palaeoenvironment, and the history of early primates (eds Lehmann T, Schaal SFK), pp. 73-76. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Senckenberg Gesellschaft fur Naturforschung. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Russell DE, Louis P, Savage DE. 1973. Chiroptera and Dermoptera of the French early Eocene. Univers. Calif. Publ. Geol. Sci. 95, 1-57. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simmons NB, Geisler JH. 1998. Phylogenetic relationships of Icaronycteris, Archaeonycteris, Hassianycteris, and Palaeochiropteryx to extant bat lineages. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 235, 1-182. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hand SJ, Sigé B. 2018. A new archaic bat (Chiroptera: Archaeonycteridae) from an early Eocene forest in the Paris Basin. Hist. Biol. 30, 227-236. ( 10.1080/08912963.2017.1297435) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sigé B, Maitre E, Hand S. 2012. Necromantodonty, the primitive condition of lower molars among bats. In Evolutionary history of bats (eds Gunnell GF, Simmons NB), pp. 456-469. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teeling EC, Springer MS, Madsen O, Bates P, O'Brien SJ, Murphy WJ. 2005. A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science 307, 580-584. ( 10.1126/science.1105113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Godthelp H, Archer M, Cifelli R, Hand SJ, Gilkeson CF. 1992. Earliest known Australian Tertiary mammal fauna. Nature 356, 514-516. ( 10.1038/356514a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith ME, Carroll AR, Singer BS. 2008. Syntopic reconstruction of a major ancient lake system: Eocene Green River Formation, western United States. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 120, 54-84. ( 10.1130/B26073.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marandat B, Adnet S, Marivaux L, Martinez A, Vianey-Liaud M, Tabuce R. 2012. A new mammalian fauna from the earliest Eocene (Ilerdian) of the Corbières (Southern France): palaeobiogeographical implications. Swiss J. Palaeontol. 105, 417-434. ( 10.1007/s00015-012-0113-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gingerich PD. 2000. Paleocene/Eocene boundary and continental vertebrate faunas of Europe and North America. GFF 122, 57-59. ( 10.1080/11035890001221057) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the table 1, section ‘Locality and age’, and section ‘Systematic palaeontology’.