Abstract

Screening is an important component of cancer control internationally. In Scotland, the National Health Service Scotland provides screening programmes for cervical, bowel and breast cancers. The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the suspension of these programmes in March 2020. We describe the integrated approach to managing the impact of the pandemic on cancer screening programmes in Scotland throughout 2020. We outline the policy context and decision-making process leading to suspension, and the criteria and framework informing the subsequent, staggered, restart in subsequent months.

The decision to suspend screening services in order to protect screening invitees and staff, and manage NHS capacity, was made after review of numbers of screening participants likely to be affected, and the potential number of delayed cancer diagnoses. Restart principles and a detailed route map plan were developed for each programme, seeking to ensure broad consistency of approach across the programmes and nationally. Early data indicates bowel, breast and cervical screening participation has increased since restart. Primary care has had to adapt to new infection prevention control measures for delivery of cervical screening. Cancer charities provided cancer intelligence and policy briefs to national bodies and Scottish Government, as well as supporting the public, patients and screening invitees through information and awareness campaigns.

Emerging from the pandemic, there is recognition of the need and the opportunity to transform and renew both cancer and screening services in Scotland, and in particular to address long-standing workforce capacity problems through innovation and investment, and to continue to prioritise addressing health inequalities.

Keywords: COVID-19, Impact of pandemic, Cancer screening, Programmatic screening, Screening suspension, Screening restart, Monitoring impact

Abbreviations: BCEs, Board chief executives; CRUK, Cancer Research UK; FIT, Faecal immunochemical test; HPV, Human papilloma virus; IPCT, Infection Prevention and Control Team; NSD, National Services Division; NSS, NHS National Services Scotland; NSOB, National Screening Oversight Board; PPE, Personal Protective Equipment; SCC, Scottish Screening Committee

1. Introduction

The Scottish Government announced the temporary suspension of the National Screening Programmes (including the cervical, breast, and bowel screening services) due to the COVID-19 pandemic on 30th March 2020. Cervical screening restarted on 29th June, breast screening on 3rd August, and bowel screening on 12th October. This paper will provide a multi-sectoral perspective on the impact of COVID-19 on cancer screening programmes in Scotland in 2020, including the policy context and decision-making process leading to the suspension, the criteria and framework informing the subsequent, staggered, restart in subsequent months, and provide early data on restart of bowel, breast and cervical screening programmes.

2. Background

Cancer is a leading cause of death for both males and females in Scotland (Cancer Incidence in Scotland, 2020). Within the United Kingdom, health is a devolved area of government responsibility: the Scottish Government has sought to address rising cancer incidence and mortality, and observed variation in outcomes (e.g. by socio-economic status) through policy strategies that address prevention, detection and diagnosis, treatment and survivorship care (Beating Cancer: Ambition and Action, 2016a). As the scale of the global COVID-19 pandemic became clear, guidance was developed to aid diagnostic decision-making in primary care (Jones et al., 2020; Helsper et al., 2020). The impact of COVID-19 on cancer diagnoses and outcomes is now increasingly being understood in Scotland and internationally (Public Health Scotland, 2020; Maringe et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Sharpless, 2020). Similarly, data are now emerging on the effect on cancer screening programmes (Dinmohamed et al., 2020; Yong et al., 2020).

In Scotland, there are currently three cancer screening programmes: bowel, breast and cervical (Screening in Scotland, 2020). Bowel screening is offered to everyone aged 50–74 years every two years, and is delivered via a postal faecal immunochemical test (FIT) direct to the participant's home. Kits are mailed back to the nationally commissioned Bowel Screening laboratory and analysed; thereafter all positive results are referred electronically to the participant's local Health Board for follow-up and colonoscopy. Mammography is offered to women and those with a female Community Health Index (unique health number) aged 50–70 years, every three years, either at a local screening centre or a mobile screening unit. Cervical screening is routinely offered to women and those with a female Community Health Index in Scotland, every five years (for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) negative participants between the ages of 25 and 64. HPV primary testing was introduced in mid-March 2020 to replace cervical cytology (Scottish Government, 2020). Governance of screening in Scotland is multi-level. Policy and Strategy is led by the UK National Screening Committee, the Scottish Government and the NHS Scotland (NHSS) Chief Executive; Assurance and Oversight is provided by the Scottish Screening Committee (SSC), the NHS Board Chief Executives, and the National Screening Oversight Board (NSOB). Programmes are coordinated nationally by National Services Division (NSD) of NHS National Services Scotland (NSS). Operational delivery is the responsibility of the fourteen local health boards, although some elements of the cancer screening programmes (Breast Screening, Bowel Screening Laboratory and Cervical Screening Laboratories) are nationally commissioned by NSD. The governance for each screening programme sits with its Programme Board.

2.1. Suspension of screening

In March 2020, as the number of COVID-19 cases in the UK began to increase, risk assessments were developed for each of the Scottish screening programmes outlining the risks associated with both continuing and pausing screening, with expert clinical and public health input from each screening programme's governance group (Programme Board). It was agreed that a decision on the continuation of screening should be taken nationally to ensure a consistent and equitable approach across the country.

Many NHS Boards were already cancelling elective inpatient activity and outpatient clinics in order to redeploy staff to support the COVID-19 response, resulting in a lack of staff and accommodation to deliver screening and investigative procedures safely. There were ethical concerns that any screening participant with a positive result would experience delays in onward assessment and treatment (e.g. elective colonoscopy services had to be suspended due to infection control concerns). There was also a risk that continuing screening may lead to increased transmission of the virus amongst staff and participants. Although it was recognised that the main risk of pausing screening would likely be public anxiety arising from the potential delay in the diagnosis of the screened-for conditions, the actual risk of participants experiencing a clinically significant delay in diagnosis was considered to be relatively small if the programmes were paused for a short time.

Estimates of the number of screening invitees likely to be affected were derived from screening data for the previous 12-month period for the number of screening appointments for each programme that would take place in a three-month period, along with the expected number of cases of the screened-for condition that would subsequently be diagnosed. Estimated numbers affected per quarter-year, based on the most recent information available to Public Health Scotland, were 248,177 invitations to Bowel Screening, with an expected 220 cancer diagnoses; 46,596 invitations to breast screening, with an expected 291 cancer diagnoses; and 101,963 patients invited to cervical screening, with an expected 70 diagnoses of invasive cancer.

The risk assessments therefore recommended that adult screening programmes should be paused for an initial period of three months in order to facilitate social distancing, reduce virus transmission and to minimise the impact on essential NHS services as they responded to COVID-19. The Scottish Directors of Public Health, Board Chief Executives and the Chair of the Scottish Screening Committee endorsed this recommendation and it was submitted to Scottish Government for approval with accompanying documentation. The Chief Medical Officer and Scottish Government Ministers reviewed the submission and endorsed the recommendation. National Screening Programmes across the four UK Nations consulted with each other. Wales and Northern Ireland took the same approach as Scotland and paused all adult screening programmes. Whilst England did not officially pause screening, screening activity was severely curtailed.

The pause of screening was communicated to the public on March 30th 2020 during the Scottish Government's daily televised COVID-19 briefing and also through Scotland's national health information website (www.nhsinform.scot/), social media and individual written correspondence to those at particular stages of screening. Public messaging also included a description of signs and symptoms of the conditions screened for and advice to seek medical assistance should any develop. Health Professionals received guidance around how to manage the pause and participant enquiries.

The issuing of invitations, reminders, appointments and bowel screening kits was stopped and most existing appointments were cancelled. Each programme ensured that tests for participants who had recently been screened continued to be analysed and communicated. Breast screening assessment clinics continued to take place until all participants with a positive mammogram had been fully assessed and referred for treatment if required. Elective colonoscopy services were cancelled nationally and bowel screening participants with a positive result were informed that there would be a delay in their colonoscopy taking place. Colposcopy continued to some extent in all NHS Boards, however capacity was reduced due to PPE and infection control measures and remains this way.

2.2. Restarting screening

2.2.1. Recovery leadership

The Scottish Screening Committee (SSC) and Board Chief Executives (BCEs) delegates responsibility for the oversight of national screening services in Scotland to the National Screening Oversight Function (NSOF) which includes the National Screening Oversight Board (NSOB): the NSOB includes membership from Directors of Public Health, Board Screening Coordinators and screening service delivery partners at local and national levels. NSD led the development of detailed recovery plans for each screening programme via the Programme Board structure and these were then approved by the NSOB. A number of principles (see Table 1 ) were developed to ensure consistency across all programmes whilst acknowledging that the restarting of different programmes may require slightly different approaches. It was acknowledged that some principles would be more relevant than others and that to adhere to one principle too robustly could compromise adherence to another.

Table 1.

Principles of the national screening oversight board to inform restart decisions for screening programmes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.2.2. Recovery workplan and routemap

A detailed recovery workplan was produced to meet the following objectives: develop materials to support safe, consistent recovery delivery, ensure IT changes were in place and tested, develop national communications for participants, and review national standards to agree variations (especially around risk stratification). In addition, an Equalities Impact Assessment and action plan were put in place, and a monitoring plan to assure delivery, support ongoing flex of plans and planning for subsequent phases was developed.

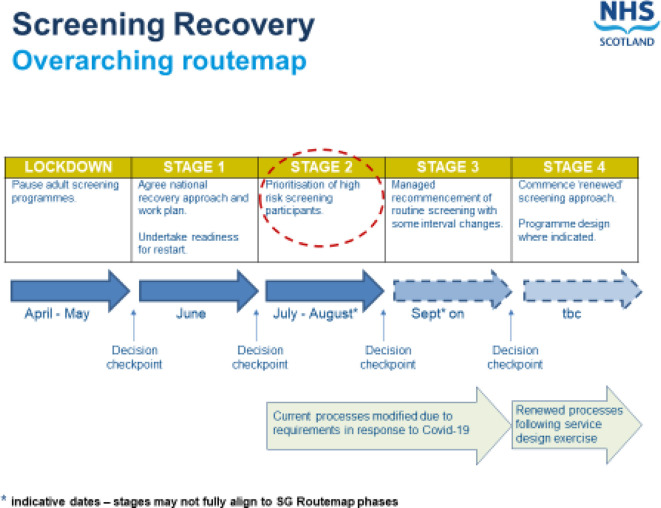

Individual programme recovery plans were developed by multi-disciplinary operational groups and approved by Programme Boards. A national screening Recovery Routemap (Fig. 1 ) was used by Boards as a basis for their own screening delivery recovery plans. Responsibility for the decision process for recovery and restart was shared across different groups. The Screening Programme Board had to confirm availability of all elements of the programmes (call/re-call, screening, diagnostic tests, treatment services), by the target date. The NSOB's role was critical: they reviewed the screening programme plans (including mitigation actions), and the restart proposals before recommendation of these to the SSC and Scottish Government. The SSC approved the plans (including any variations to standards and process changes); these were then endorsed by the Board Chief Executives. Detailed restart actions for recovery for each screening programme are shown in Table 2 : in each case, the staged approach allowed for consistency in implementation across the country.

Fig. 1.

NHS Scotland Screening Recovery Routemap.

Table 2.

Outline of key stages in restart decisions for each cancer screening programme in Scotland.

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | Stage 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cervical | Agree national recovery approach and work plan. Undertake readiness for restart. |

Prioritised recommencement of non-routine screening. Participants invited prior to pause can make an appointment. |

Managed recommencement of routine screening. | Commence ‘renewed’ screening approach. Programme redesign, including planning self-sampling pilot. |

| Bowel | Agree national recovery approach and work plan. Undertake readiness for restart. |

All health boards to recommence screening colonoscopy. Provide HBs numerical FIT values for participants on colonoscopy waiting lists to enable local prioritisation. | Managed recommencement of screening with short term gap for all recall participants. New participants start as normal around 50th birthday. |

Commence ‘renewed’ screening approach, including exploration of any potential programme redesign. |

| Breast | Agree national recovery approach and work plan. Undertake readiness for restart. |

Prioritisation of symptomatic & high risk clinics. | Managed restart of screening from where the pause was implemented. Temp pause on self-referrals for women 71+ & out with the eligible invited age range. | Commence ‘renewed’ screening approach. Breast screening review completion and recommendations implementation. |

Each screening programme's national IT system required significant modifications and developments both to pause and restart. The Bowel Screening IT system had built-in pandemic functionality which allowed the programme to be paused easily and this function was subsequently introduced across the other systems. The overall landscape of standards, key performance indicators and targets was reviewed at each stage to ensure progress towards the Scottish screening strategic objectives.

Communication materials were developed by Health Scotland to include letter inserts informing participants of any changes to screening due to COVID-19 restrictions following restart, reassurance that infection-control measures were in place to ensure that COVID-19 risks were minimised and to advise of the continued importance of undertaking screening, with informed consent. Other communication material was shared via social media to emphasise to participants that travelling to screening was considered an ‘essential activity’ in terms of COVID-19 restrictions. Communications to health professionals in primary care and the acute sector were shared via Board Coordinators to ensure all stakeholders were aware of the plans and had opportunities to input views according to local circumstances. A national inequalities workshop was held with third sector agencies and other screening stakeholders to examine the effect of COVID-19 on screening inequalities and identify potential mitigation measures.

2.3. Practical implementation of Restart

The three screening programmes restarted at different times. A number of considerations informed the decision for each programme. Cervical screening re-started first (end of June 2020) for those who had received a prompt for screening before the pause but who had yet to make an appointment, or had their appointment cancelled due to COVID. Participants on the non-routine screening pathway (i.e. those who receive more frequent screening due to a previous screening result) started to be invited from the 6th July – this was because they were considered at higher risk of disease. Staff from the breast screening programme were redeployed to support high-risk surveillance clinics (e.g. due to family history, genetics etc.) until the end of July as these groups were assessed as being at greater risk than the general breast screening population. Once this cohort had been managed, staff were able to return to the Breast Screening services and re-commence screening in August 2020. Whilst it would have been straightforward to restart the issuing the of bowel screening kits before any of the other programmes restarted, this would have led to unacceptable waiting times for colonoscopy amongst participants with a positive screening test, as elective colonoscopy worked had been temporarily paused. It was necessary to clear the bowel screening colonoscopy backlog before new screening kits could be issued, and this took until the end of September 2020. Bowel screening officially recommenced in October 2020.

2.3.1. Cervical screening

Cervical screening was restarted on a phased basis from the end of June 2020. In July and August, participants on non-routine recall who should have been invited for screening from the time of the pause onwards were sent a screening invitation. Non-routine recall reminders were also sent during this time. From September 2020 onwards, following an assessment of sample taker capacity, participants on routine recall who should have been sent a screening invitation from the time of the pause onwards were sent one. Women on non-routine recall were “caught up“in terms of recall date, whilst those on routine had their dates moved forward by the length of the pause. Additionally, any participant who was invited for screening before the pause who had yet to make an appointment or who had their appointment cancelled was informed via public communications that they could contact a sample taker location to request an appointment. This included women who required a cervical screening test for fertility treatment.

The number of new invitations sent out nationally per month was reduced by 50% to around 15,000 in July and August, as screening capacity within primary care was reduced due to COVID-19 infection control measures (see below). The number of prompts issued returned to normal levels in September when routine screening commenced. To supplement the message that attending for screening was safe and important to consider, Public Health Scotland produced a video on NHS inform by a practice nurse describing what to expect on going to GP practice for smear (Coronavirus (COVID-19), 2020).

2.3.2. Breast screening

On recommencement in early August 2020, the breast programme restarted screening based on the pre-existing schedule inviting women by GP practices. However, appointments were first prioritised for those participants who had failed to attend or cancelled their appointment in March, and participants invited to clinics which were cancelled by the service. Those who had fallen above the upper screening age during the pause were also offered an opportunity to attend for screening. Given the lack of evidence around the risks versus benefits of screening women aged over 71 years, a temporary pause was introduced on over-age self-referrals. Communications signposting breast awareness information and primary care pathways for referral to symptomatic services were promoted.

Screening centres had to make changes to working practices to incorporate the necessary precautions. Requirements included new ventilation systems, screens and processes to manage participant flow through the range of environments (static and mobile units). Managing patient flows to include social distancing often in small mobile units, alongside new IPCT and PPE requirements meant that appointment times had to be increased and capacity was significantly reduced. To mitigate against this, two additional mobile units which were about to be decommissioned were re-fitted and re-introduced to the programme and some centres extended their working hours. Patient flows at mobile units were managed in a variety of ways across screening centres, including options such as manual management of queuing outside and introduction of a “coaster buzzer” system to allow women to wait either in their cars/shelter in the nearby supermarket facilities etc. and be alerted safely when the staff were ready for them to enter the mobile premises. Screening appointment slots have subsequently returned to the normal duration but capacity remains limited because over-booking of clinics (to take into account non-attendance) cannot be done due to the inability to socially distance women if more women than expected attend their appointments.

2.3.3. Bowel screening

Prior to the recommencement of mailing of bowel screening testing kits in mid-October 2020, it was agreed that Health Boards should reduce screening colonoscopy waiting lists to pre-covid levels. This required additional resource to be provided to some Boards. Bowel screening test results are classed as either FIT positive or FIT negative: all FIT positive cases should be referred for colonoscopy and prioritised in the same manner as urgent suspicion of cancer referrals. However, to aid the prioritisation of participants awaiting colonoscopy it was agreed that FIT values could be provided to Boards, given that a higher faecal haemoglobin concentration is associated with severity of colorectal neoplasia (Digby et al., 2013). The provision of these values stopped once the backlogs had been cleared, as screening data shows that the use of FIT values to predict cancer risk is less useful than in symptomatic patients. Although those with lower FIT values in the screening range are less likely to have cancer than those with higher values, the difference is not great, particularly at levels above 100, and there is virtually no difference in the prevalence of high-risk adenomas.

Whilst much was unknown at the start of the pandemic there was felt to be a plausible and possible risk of faecal transmission of SARS CoV at colonoscopy (Endoscopy Activity and COVID-19, 2020). Since then further guidance (British Society of Gastroenterology, 2020) has been issued with advice to undertake colonoscopy alongside infection control measures. These include pre-procedure patient testing, self-isolation and/or social distancing pre-endoscopy, increased PPE required and room downtime/fallow time between procedures. Collectively the efforts to improve safety and reduce transmission contributed to a much longer time to scope each patient and consequently services are operating at a much reduced capacity and throughput. This along with a backlog of symptomatic patients accrued during the pause of colonoscopy services following GP referral or those undergoing surveillance colonoscopies, provides ongoing difficult priority service delivery decisions for any of these patients awaiting colonoscopy.

2.4. Performance since screening Restart

One of the many concerns around the impact of the pandemic was how screening participation may be affected. Breast and cervical screening require physical attendance at a healthcare facility, as does a positive test result in bowel screening. Clearly, such appointments have the potential to raise a person's risk of COVID-19 infection via attendance at and/or travel to and from such a setting (although risks were minimised due to infection control measures and PPE). There were therefore concerns that this would discourage attendance and that a reduced level of uptake could become a feature of programmes until the pandemic had abated. Fortunately, early data from the Scottish cancer screening programmes suggest that this may not be the case.

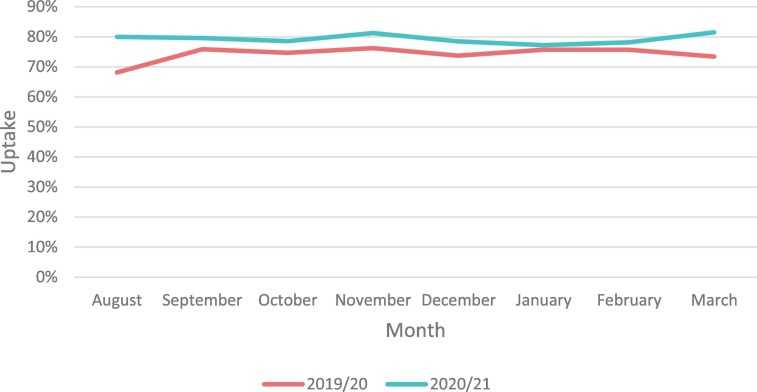

Fig. 2 shows uptake by month in the Scottish breast screening programme, for 2019/20 and 2020/21. Since the resumption of the programme in August, a higher proportion of women have attended for mammography appointments, with an increase of 2–8% points from September to March. Although data on socioeconomic deprivation per se are not currently available for breast screening, increases are seen across the different breast screening centres in Scotland, giving some cause for optimism (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Breast screening uptake by month, for 2019/20 and 2020/21. Participation rates are conditional on being invited.

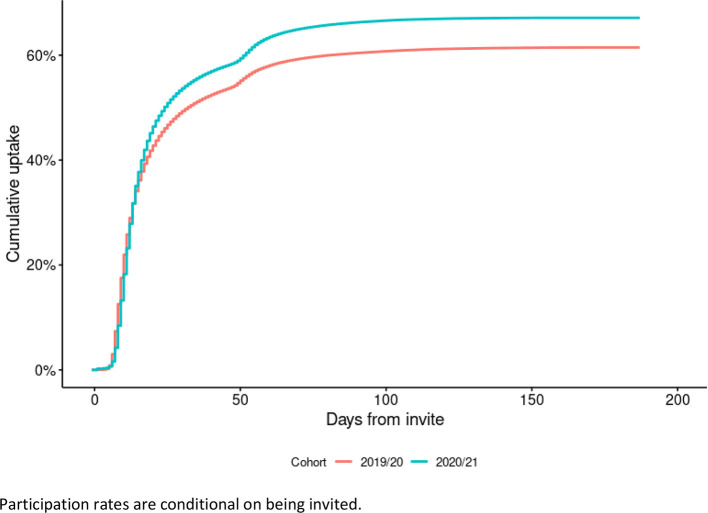

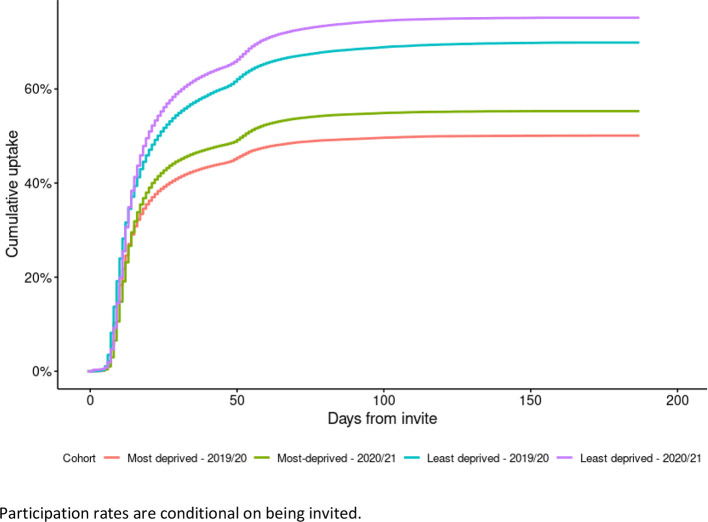

Data from the Scottish Bowel Screening Programme tells a similar story. In order to adjust for the time taken for participants to return kits, Fig. 3 shows cumulative uptake since the 11th of October 2020 (when the programme resumed), compared to the same time period from October 2019. Cumulative uptake is estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method (Kaplan and Meier, 1958). A clear difference can be seen from around 25 days after a kit being issued, and current estimates of uptake are 67.1% in the 2020/21 restart cohort vs. 61.5% in the equivalent period in 2019/20, with 6 months of follow-up. Further analysis showed that this trend for increased uptake since the programme restarted can be seen for all levels of socioeconomic deprivation: data for the most and least deprived are shown in Fig. 4 , with clear increases in 2020/21 for both groups.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative uptake for the Scottish Bowel Screening Programme, for 2019/20 and 2020/21.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative uptake for the most and least deprived postcodes in the Scottish Bowel Screening Programme, for 2019/20 and 2020/21.

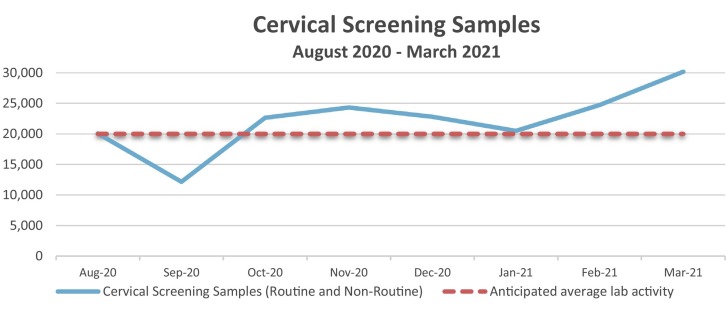

Early data from the cervical screening programme are also encouraging. Fig. 5 shows the actual versus anticipated cervical screening samples processed, since resumption of the programme. From October 2020 the number of samples processed is above the anticipated level, implying greater participation levels than in years, with only January being in line with expectations. It is important to note that there have been variations in monthly mailing of invitations, so the true pattern of participation since restart will emerge only in 2021.

Fig. 5.

Actual versus anticipated cervical cancer screening samples processed from August 2020 –March 2021.

Participation rates are conditional on being invited.

Data reflect a complex restart process. Figures received for August are actually from 30 June – 31 August; only half the anticipated number of invitations were sent out in July and August; September 2020 data also highlights a mailer incident in August where around 13,000 non-routine invitations were not sent out and were subsequently sent out at the start of November.

The early picture from the cancer screening programmes is an encouraging one. However, an important limitation is that the data shown here are early data from the programmes. It will likely be years until the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on screening is fully understood, and it may be that the trends we see at this point in the pandemic change over time. Nonetheless - and contrary to the concerns that the screening population would be reluctant to participate during a pandemic - uptake appears to have come back stronger. Research is underway in Lothian to understand the increased attendance at breast screening: one theory is that with more women working at home the screening site is closer and more convenient to attend when invited; raised health anxiety due to COVID-19 may also play a role.

Although recovery has been strong in terms of uptake of invited participants, screening programmes are operating a varying levels compared to pre-pandemic activity. For breast screening, restart metrics for the period August 2021 to March 2021 indicate that capacity (i.e. number of invitations sent to women) was 80% compared to the previous year. For cervical screening, whilst there are some reports of reduced capacity from primary care (particularly due to staff being engaged in supporting covid vaccination), the number of samples received by the cervical screening labs per month are in line with or above routine activity estimates. General Practice staff have been prioritising cervical screening over other work that is carried out by Practice Nurses, e.g. chronic disease management, and efforts are being made to increase staff hours and numbers. In the bowel screening programme, while capacity has increased, it remains below pre-covid levels (exact data not available).

3. Involvement and role of primary care

Primary care has had to adapt and change to accommodate the restart of the cancer screening programmes alongside general practice services. Most cervical screening delivery in Scotland is carried out in primary care/GP practices. As described above, restart across the three cancer screening programmes was staggered with cervical screening restarting for people on non-routine recall in July 2020, i.e. a four-month pause. National guidance (COVID-19: Infection Prevention and Control (IPC), 2020) on physical distancing, infection control and health and safety measures for COVID-19 have brought challenges. Cervical screening requires close face to face engagement; many general practice premises struggle with accommodation and layout to maintain physical distancing in the waiting area and reception, limiting the flow and numbers of people in the practice premises; increased cleaning regimes and time to don and doff PPE has resulted in the length of a cervical screening appointment doubling. Primary care screening capacity has therefore been estimated at 50% of normal levels. Workforce pressures due to sickness, shielding, caring responsibilities, self-isolating and COVID-19 infection itself has also contributed to the difficulty of providing cervical screening in primary care. Concurrently, the primary care workforce in heavily involved in delivering the UK's COVID-19 vaccinations, and practices need to balance this priority against ongoing delivery of cervical screening. Further, HPV primary testing had only just been introduced in Scotland in the weeks prior to suspension (early March 2020, (Scottish Government, 2020)), and primary healthcare professionals are also providing information and reassurance to women about this change.

General practice provides cradle to grave care and support and the balance of addressing acute, chronic and preventative care has been challenging to deliver. Keeping patient pathways in place for those who are well and require screening for example, alongside those who are unwell and who may turn out to have COVID-19, has required planning and teamwork. Restarting screening has also brought ethical questions of inviting well people into health care settings when the Government message is to stay at home. The balance of risk of late presentation and diagnosis of cancers has been the driver to resume screening programmes, and many practices have been proactive in identifying and calling in those patients most at risk i.e. already on non-routine recall pathways. In addition, all staff delivering screening ensure that full PPE/infection control measures are taken to ensure the safety of participants.

General practice has seen some potential benefits of changes in procedures, for instance a move to new models of working with more telephone consultations and triage and use of sign posting to other health services. However, the impact of the pause and waiting times in secondary care has resulted in more people phoning practices with queries about cervical screening appointments. Scottish Government offered additional funding to health boards to boost cervical sample taking and colonoscopy capacity. For example, NHS Lothian Primary Care opted to increase capacity and availability by offering additional clinics/ appointments using additional hours for existing staff or supplementary staff either within or out with normal practice hours. Other boards used a more community-based model providing capacity in community settings instead of within the constraints of general practice.

4. Engagement with third sector

Scotland has substantial third sector involvement in the cancer landscape; these organisations advocate on behalf of the public and patients, and many actively participated in policy discussion and engagement with screening services, both during suspension and since restart of screening.

Cancer Research UK (CRUK, (Cancer Research UK, 2020)), the UK's largest cancer charity, sees its role as that of a ‘critical friend’ to the NHS and the Scottish Government, providing supportive and constructive input, as well as being a trusted source of information to the public, people affected by cancer, health professionals, and the academic community. At the policy level, CRUK draws on its substantial evidence, data and public affairs and policy teams to provide briefings to Members of Parliament, the Cross Party Group on Cancer and COVID-19 Health Committee at the Scottish Parliament, and the Scottish Screening Committee, and UK-wide through national stakeholder group. Advocacy priorities are ensuring cancer services are minimally disrupted as staff are redeployed to COVID-19 roles, addressing variation in delivery of diagnostic services across health boards, and development of safe spaces to support confidence in the ‘NHS is open’ message by the public. Messaging has had to balance reassurance to attend screening (it is safe, and that screening has the potential to detect earlier disease), with the recognition of ethical concerns about potential delays in investigations following a positive result with resources and capacity stretched in secondary care as they deal with symptomatic patients. Cancer awareness messages to the public have emphasised the need to make an appointment with a GP if suspicious signs and symptoms occur, and again that it is safe to do so; this is especially important given the overlap of COVID-19 and lung cancer symptoms.

CRUK currently has agreements with six NHS Health Boards to offer frontline support through provision of training to general practices in increasing screening participation, by reducing barriers to participation, engaging with non-responders and addressing inequalities. This included training for practice nurses on information sharing around the introduction of HPV screening. These activities were curtailed since the screening pause; even since the restart, practice time has been limited although remote training is now being offered again. There was concern that the ‘stay at home’ and ‘avoid public transport’ messages during lockdown may have put women off attending breast and cervical screening appointments, potentially exasperating inequalities.

Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust has developed information materials for women concerned about attending cervical screening during the pandemic (Jo's Cervical Cancer Trust, 2020), and is advocating for faster consideration of self-sampling HPV testing to be introduced within the cervical screening programme across the UK. Self-sampling pilots are currently in place around the UK, including Scotland and a further large-scale pilot of self-sampling for non-responders is currently being planned for Scotland. Similarly, Bowel Cancer UK has been active in advocacy, and providing online information, advice and support (Bowel Cancer UK, 2020). The Scottish Cancer Coalition, a partnership of 32 voluntary organisations representing a wide-range of cancers (Scottish Cancer Coalition, 2020), collectively published a comprehensive “11-point plan for recovery and renewal” of cancer services in Scotland in June 2020, setting out what they regarded as the priority areas for the NHS and Scottish Government to enable cancer services to recover from the pandemic. These included the need to monitor the impact of COVID-19 on delivery of cancer care and on cancer outcomes, protection of staff and provision of safe spaces for cancer treatments, and addressing public awareness (including of cancer screening) and encouraging help-seeking with suspicious symptoms. In particular, the Coalition advocated for development of plans to provide “adequate catch-up approaches, with clear targets in place for when to reach pre-covid-19 levels of coverage and uptake”.

5. Challenges and opportunities going forward

The consistent message from clinicians and the third sector in Scotland is the need for ‘renewal and transformation’ not just ‘restoration’ as cancer and screening services emerge post-covid. Some of the workforce and capacity issues pre-date the pandemic. Rebuilding will require substantial investment in the cancer workforce, innovation in use of technology and data sharing, and accelerating rigorous research on the introduction of new diagnostics tests and rapid diagnostic clinics in order to not only address the covid-related backlog but also to ‘future proof’ cancer care in Scotland. Many of these issues are now embedded in policy documents (Recovery and Redesign: An Action Plan for Cancer Services, 2020; Beating Cancer: Ambition and Action, 2016b) and recommendations (Early Detection and Diagnosis of Cancer a Roadmap for the Future, 2020). In particular, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the inadequate colonoscopy capacity in Scotland, and variation in waiting times between health boards that jeopardise patient care. There is now a dedicated programme recovery board that will give recommendations to the Scottish Screening Committee on ways of mitigating colonoscopy capacity at the national level.

As noted previously, the full impact of the ongoing pandemic on cancer outcomes will only be known in years to come. While early uptake results are encouraging for breast and bowel screening participation in Scotland, the impact of the economic downturn and increasing unemployment may exacerbate existing inequalities. The emphasis is now on encouraging people to attend screening when invited, but also promoting recognition of symptoms and help-seeking, and prompt referral for investigation. There is an urgent need for screening programmes to return to operating at 100% capacity in order to prevent the pause-related screening delays from continuing even longer, with adverse consequences for patients.

A study of 79-countries found that mortality for screen-detectable cancers increased during times of economic recession, with some indication that universal health coverage could have had a protective effect against the possible impact of unemployment (Maruthappu et al., 2016). Although Scotland has a national health system, and organised screening programmes, deprivation gradients in screening participation existed prior to COVID-19, and are a continuing cause for concern. As mentioned, a Screening Inequalities workshop was held with stakeholders and Third Sector partners to examine concerns about widening inequalities: it is recognised that COVID-19 will likely have exacerbated existing screening inequalities. The National Screening Oversight Function is working with the Scottish Government, Public Health Scotland and the screening programmes to develop a high-level inequalities strategy. Scottish Government has made additional funding available to tackle this issue. In NHS Lothian, there has been considerable efforts focusing on access and support to make informed decision about screening in more deprived communities, with people with learning disabilities, amongst Black and Minority Ethnic communities, people in prison and long-term institutions with severe mental health illness, addiction services, the transgender community, trauma informed community services, and gypsy travellers. There has also been education initiatives for healthcare professionals to raise awareness of challenges within screening for marginalised groups.

Unanticipated benefits have however been seen during the management of this pandemic. Colleagues report better interaction between primary and secondary care, with GPs and hospital specialists liaising directly for advice on referral, safety-netting guidance, seeking continuity of care, and avoiding bottlenecks in referral pathways: there is a need for this better communication to be continued post-pandemic. Governance structures and internal and external communication strategies within the Screening Programmes have been strengthened, as has more rapid information governance decisions, provision of IT and reporting systems and availability of data to inform decision-making within Public Health Scotland. These changes are welcome, and build resilience for future events for cancer screening delivery in Scotland. As we reflect on the lessons learned during the total process of decision to suspension to restart, a critical issue to emerge was that the earlier that a national decision is taken, the better: this prevents different health boards from taking different actions, creating inequity in screening provision around the country. Internationally, cancer detection and screening programmes are grappling with similar issues of suspension, restart and rebuilding: sharing knowledge and effective practices will be important for the global community (Puricelli Perin et al., 2021; Figueroa et al., 2021).

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

We report Scotland-level non-identifiable aggregate data on restart of screening programmes: these data are routinely collected and collated by Public Health Scotland within their statutory responsibilities. Approval for use in this manuscript was sought from Directors of Public Health & Health Board Screening Coordinators.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gareth Brown, Bryan Davies and David Steel (Screening, NHS National Services Scotland), Prof Bob Steele (Director, Scottish Bowel Cancer Screening Programme), and Marion O'Neill, Lisa Cohen and Samantha Harrison (Cancer Research UK) for helpful discussion and insights. We acknowledge statistical input for re-start participation data from John Quinn, Douglas Clark, and Murdo Turner (Public Health Scotland).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106606.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Table - Participation (% of invitees) at breast screening centres in Scoltand (June 2019 - March 2021)

References

- Beating Cancer: Ambition and Action Scottish Government, March. 2016. https://www.gov.scot/publications/beating-cancer-ambition-action/ Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Beating Cancer: Ambition and Action . The Scottish Government; 2016. Update: Achievements, New Action and Testing Change.https://www.gov.scot/publications/beating-cancer-ambition-action-2016-update-achievements-new-action-testing-change/ April 2020. Accessed 15/02/2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bowel Cancer UK 2020. https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk Accessed 15/02/2021.

- British Society of Gastroenterology Multi-Society Guidance on Further Recovery of Endoscopy Services during the Post-Pandemic Phase of COVID-19. August 2020. https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-19-advice/bsg-multi-society-guidance-on-further-recovery-of-endoscopy-services-during-the-post-pandemic-phase-of-covid-19/ Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Cancer Incidence in Scotland Public Health Scotland. July 2020. https://beta.isdscotland.org/find-publications-and-data/conditions-and-diseases/cancer/cancer-incidence-in-scotland/ Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Cancer Research UK 2020. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Immunisation and Screening. NHS Inform. 2020. https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-and-poisoning/coronavirus-covid-19/healthy-living/coronavirus-covid-19-immunisation-and-screening# Accessed 15/02/2021.

- COVID-19: Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) UK Government Guidance. January 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Digby J., Fraser C.G., Carey F.A., et al. Faecal haemoglobin concentration is related to severity of colorectal neoplasia. J. Clin. Pathol. 2013;66:415–419. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2013-201445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinmohamed A.G., Cellamare M., et al. The impact of the temporary suspension of national cancer screening programmes due to the COVID-19 epidemic on the diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020 Nov 4;13(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00984-1. PMID: 33148289; PMCID: PMC7609826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early Detection and Diagnosis of Cancer a Roadmap for the Future Cancer Research UK. 2020. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/early_detection_diagnosis_of_cancer_roadmap.pdf Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Endoscopy Activity and COVID-19 British Society of Gastroenterology and Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy Guidance. April 2020. https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-19-advice/endoscopy-activity-and-covid-19-bsg-and-jag-guidance/ Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Figueroa J.D., Gray E., Pashayan N., Deandrea S., Karch A., Vale D.B., Elder K., Procopio P., van Ravesteyn N.T., Canfell K., Nickson C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on breast cancer early detection and screening. Prev. Med. 2021;(151C) doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsper C.W., Campbell C., Emery J., et al. Cancer has not gone away: a primary care perspective to support a balanced approach for timely cancer diagnosis during COVID-19. Eur. J. Cancer Care. 2020 Sep;29(5) doi: 10.1111/ecc.13290. Epub 2020 Jul 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D., Neal R.D., Duffy S.R.G., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the symptomatic diagnosis of cancer: the view from primary care. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Jun;21(6):748–750. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30242-4. Epub 2020 Apr 30. PMID: 32359404; PMCID: PMC7251992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo'’s Cervical Cancer Trust Coronavirus Guidance. 2020. https://www.jostrust.org.uk/coronavirus Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Kaplan E.L., Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Lai A.G., Pasea L., Banerjee A., et al. Estimated impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer services and excess 1-year mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity: near real-time data on cancer care, cancer deaths and a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 17;10(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043828. PMID: 33203640; PMCID: PMC7674020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maringe C., Spicer J., Morris M., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Aug;21(8):1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0. Epub 2020 Jul 20. Erratum in: Lancet Oncol. 2021 Jan;22(1):e5. PMID: 32702310; PMCID: PMC7417808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruthappu M., Watkins J., Noor A.M., Williams C., Ali R., Sullivan R., Zeltner T., Atun R. Economic downturns, universal health coverage, and cancer mortality in high-income and middle-income countries, 1990–2010: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet. 2016 Aug 13;388(10045):684–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00577-8. Epub 2016 May 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Scotland . Public Health Scotland; 2020. COVID-19 Wider Impacts on the Health Care System. Cancer Dashboard.https://scotland.shinyapps.io/phs-covid-wider-impact/ Accessed 16/02/2021. [Google Scholar]

- Puricelli Perin D.M., Elfström M., Bulliard J.-L., et al. Early Assessment of the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Cancer Screening Services: The International Cancer Screening Network COVID-19 Survey. Prev. Med. 2021;(151C) doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recovery and Redesign: An Action Plan for Cancer Services The Scottish Government. December 2020. https://www.gov.scot/publications/recovery-redesign-action-plan-cancer-services/ Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Scottish Cancer Coalition 2020. www.scottishcancercoalition.org.uk Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Scottish Government Smear test to screen for HPV. 2020 March. https://www.gov.scot/news/smear-test-to-screen-for-hpv/ Accessed 07/06/2021.

- Screening in Scotland 2020. https://www.nhsinform.scot/healthy-living/screening/screening-in-scotland Accessed 15/02/2021 Accessed 15/02/2021.

- Sharpless N.E. COVID-19 and cancer. Science. 2020 Jun 19;368(6497):1290. doi: 10.1126/science.abd3377. 32554570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong J.H., Mainprize J.G., Yaffe M.J., et al. The impact of episodic screening interruption: COVID-19 and population-based cancer screening in Canada. J. Med. Screen. 2020 Nov 26 doi: 10.1177/0969141320974711. 969141320974711. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33241760; PMCID: PMC7691762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table - Participation (% of invitees) at breast screening centres in Scoltand (June 2019 - March 2021)