Abstract

Background: The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is variable and ranges from asymptomatic, mildly symptomatic, moderately severe and severe disease. A small proportion might develop severe disease and may have cytokine storm. One of the therapeutic options to treat such cases is Tocilizumab (TCZ). In this study, we present cases of severe COVID-19 treated with TCZ and glucocorticoids and discuss the treatment responses.

Methods: This is a retrospective observational study of severe COVID-19 cases treated with TCZ and glucocorticoids. The case series examined the characteristics and outcome of those patients.

Results: This study included 40 Severe Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) confirmed patients who received TCZ and glucocorticoids. The mean age of the included patients was 57.55 (±Standard deviation 12.86) years. There were 34 (85%) males, 19 (47.5%) were obese (BMI >30), 13 (32.5%) over weight, and five (12.5%) normal weight. The mean days from positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test to admission was 1.641 (±3.2) days. Of the patients, 18 (45%) had diabetes mellitus, 14 (35%) had hypertension. The mean days from hospital admission to ICU was 1.8 (±2.6), 20 (50%) required mechanical ventilation, 39 (97.5%) had received prone position, seven (17.5%) had renal replacement therapy, 13 (32.5%) required inotropes, four (10%) had plasmapheresis, one (2.5%) had intravenous immunoglobulin, all patients received steroid therapy, and the majority 31 (77.5%) did not receive any anti-viral therapy. Of all the patients, six (15%) died, 28 (70%) were discharged and six (15%) were still in hospital.

Conclusion: The overall mortality rate was lower than those cited in meta-analysis. As our understanding of the COVID-19 continues, the approach and therapeutics are also evolving.

Keywords: SARS-COV-2, COVID-19, Tocilizumab, therapy, steroid

1. INTRODUCTION

The emergence of the Severe Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) had caused the Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) pandemic and had resulted in signification medical challenges and societal interruption [1]. The clinical spectrum of COVID-19 is variable and ranges from asymptomatic, mildly symptomatic, moderately severe and severe disease [2–6]. About 5% of the patients would require Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, mechanical ventilation, and may succumbed into their illness. The reported case fatality rate of COVID-19 is variable between countries and localities [7,8]. There had been few studies of the clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia and these studies showed similar clinical characteristics to those reported in the literature [4–6,8,9]. Similar to the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus [10], the clinical course of COVID-19 may go through an initial viral replicative phase followed by an intense inflammatory response [11]. This immune response may subsequently lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, and may be associated with a cytokine storm [12]. Cytokine storm is thought to be secondary to hyper-production of cytokines including IL-6 and may increase the patient’s risk of death [13,14]. Therapeutic options for COVID-19 had been limited despite an extensive initial evaluation of multiple medications including hydroxychloroquine, ritonavir, remdesivir, and corticosteroids. Cytokine storm is of particular importance due to the limited therapeutic options. In addition, clinical diagnosis is a common theme and biomarkers such as IL-6 is not commonly available at many healthcare settings [15]. Acute inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) are not specific for cytokine storm. However, these markers might aid in the monitoring of response to therapy. In an attempt to enhance therapy for cytokines storm, Tocilizumab (TCZ) has been suggested as a therapeutic option for the disease and had been used in clinical practice for such cases [15–19]. TCZ is a humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptors and thus will inhibit the action of IL-6 [20]. However, the exact mechanism of action of TCZ in the treatment of cytokine storm is not well known. In this retrospective observational study, we present cases of severe COVID-19 treated with TCZ and glucocorticoids and discuss the treatment responses.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective observational study of severe COVID-19 cases treated with TCZ and glucocorticoids. The patients were admitted and treated at King Fahad Military Medical Complex, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. The patients received TCZ if they met the severe or critical case criteria [21]. The diagnosis of severity was based on (1) respiratory rate >30 breaths/min (2) O2 saturation <93% on room air (3) a ratio of PaO2 to FiO2 of <300 mmHg. The diagnosis of critical cases was based on (1) respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation (2) the presence of hemodynamic shock (3) multi-organ failure and (4) ICU admission [21]. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 was based on a positive Real-time (RT)-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharyngeal swabs [4,5,8,9,22].

We collected, in a standardized excel form, the following variables: demographics, laboratory data, therapeutic agents being used and outcome. The Institutional Review Board of the King Fahad Military Medical Complex approved the study (AFHER-IRB-2020-030).

2.1. Statistical Analysis

The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients and laboratory variables were compared on days 1, 2, 7 and 14 of TCZ and steroid therapy using Minitab. The mean and Standard Deviation (SD) of neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count, CRP, d-dimer, Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH), serum ferritin level, serum procalcitonin level, and serum lactate level were compared on the specified days using analysis of variance. A significant p-value for the difference was considered when p was <0.05.

3. RESULTS

This study included 40 confirmed COVID-19 patients who were treated with TCZ (Roche Pharma “Schweiz” Ltd., Basel, Switzerland; B2084B21) and corticosteroid. The first TCZ dose was based on body weight and was 4–8 mg/kg. The mean age of the included patients was 57.5 (±SD 12.8) years. There were 34 (85%) males and the majority were Saudis (N = 37, 82.5%). Of all the patients, 19 (47.5%) were obese (BMI > 30), 13 (32.5%) were overweight, and five (12.5%) had normal BMI (BMI 18.5–24.9). The mean days from positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test to admission was 1.6 (±3.2) days. Of the patients, 18 (45%) had diabetes mellitus, 14 (35%) had hypertension. On admission, 18 (45%) were febrile with temperature of 38°C, and 26 (65%) were receiving oxygen due to hypoxia. The mean days from hospital admission to ICU admission was 1.8 (±SD2.6), 20 (50%) required mechanical ventilation, 39 (97.5%) had received prone position, seven (17.5%) had renal replacement therapy, 13 (32.5%) required inotropes, four (10%) had plasmapheresis, one (2.5%) had intravenous immunoglobulin, all patients received corticosteroid therapy, and the majority (77.5%) did not receive any anti-viral therapy. Those who received anti-viral therapy were treated with favipiravir (n = 3), lopinavir/ritonavir (n = 2), lopinavir/ritonavir and Ribavirin (n = 2), or tenofovir (n = 2). The most frequently prescribed corticosteroid was dexamethasone 6 mg daily (n = 24; 60%) and the other patients received methylprednisone in variable doses (from 20 to 125 mg). The mean duration from admission to TCZ therapy was 2.8 (±SD 2) days. Of all the patients, six (15%) patients died, 28 (70%) patients were discharged and the others were still in hospital.

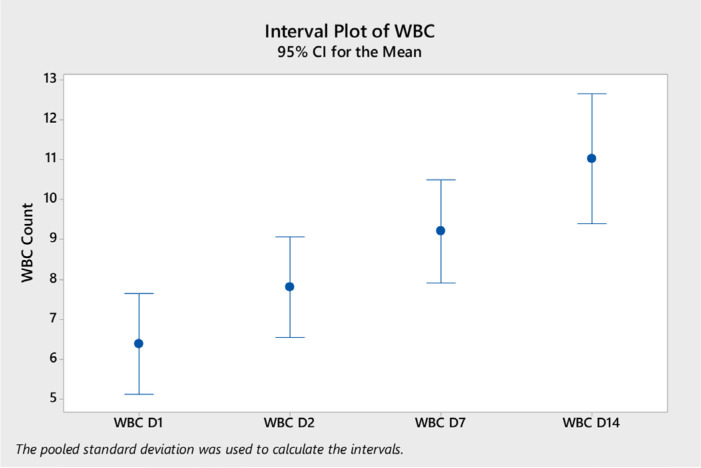

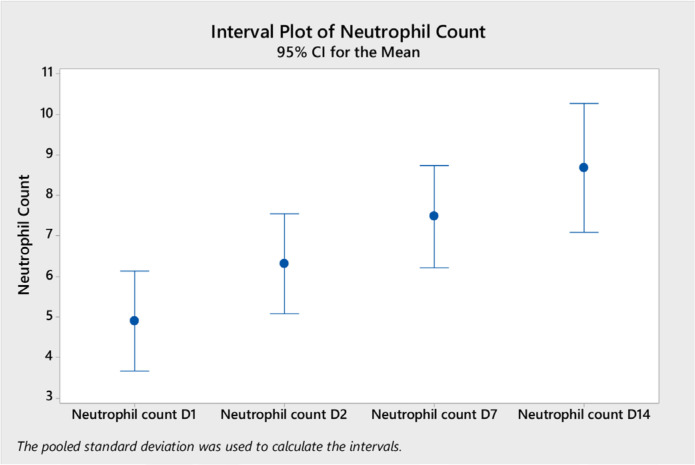

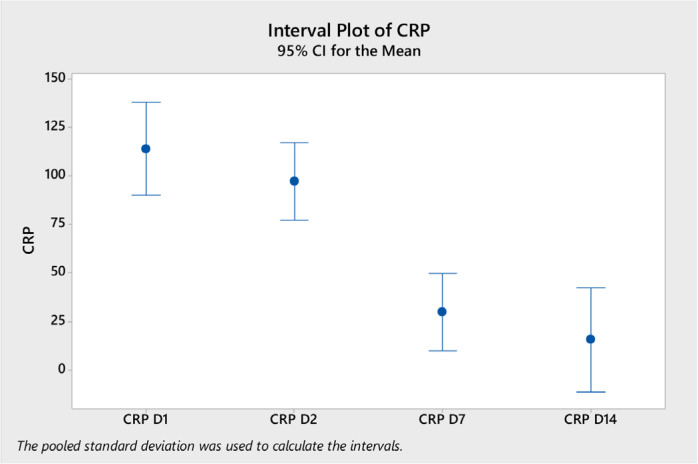

Analysis of variance of the laboratory tests showed a significant difference in the mean white blood cells (WBC) on day 14 (mean = 11.04, ±SD 4.5) compared to day 2 (mean 7.8, ±SD 3.2) and to day 1 (mean 6.4, ±SD 3.2) (p < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Neutrophil counts were significantly higher on day 14 compared to other days (Figure 2). Platelet count was significantly higher on day 7 and day 14 compared to day 1 (Figure 3). CRP level was significantly lower on days 7 and 14 compared to day 1 and day 2 (Figure 4). However, there was no difference in the mean (±SD) of lymphocyte count, d-dimer, LDH, ferritin, procalcitonin, and lactate in the different days.

Figure 1.

WBC count (mean and 95% CI) on different days after the start of tocilizumab on different days (D1, D2, D7, and D14).

Figure 2.

Neutrophil count (mean and 95% CI) on different days after the start of tocilizumab on different days (D1, D2, D7, and D14).

Figure 3.

Platelet count (mean and 95% CI) on different days after the start of tocilizumab on different days (D1, D2, D7, and D14).

Figure 4.

CRP level (mean and 95% CI) on different days after the start of tocilizumab on different days (D1, D2, D7, and D14).

4. DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study, we presented the outcome of 40 patients treated with TCZ and corticosteroid. The case fatality rate in this study was 10% and of the total cases 60% were discharged from the hospital. TCZ had been used as a therapy for patients presumed to have cytokine storm. The mean age of the included patients was 57.5 (±SD 12.8) years. In an observational study of TCZ therapy of COVID-19, the median age was 69 years [23]. In previous studies from Saudi Arabia, the reported mean age was 36–38 years [5,24] and a median age 44 years in another study [25]. In this study, 18 (45%) had diabetes mellitus, 14 (35%) had hypertension. Similarly, a previous study showed hypertension in 47% and diabetes in 16% [23]. The cited rates of the presence of comorbidities varies between 32% and 93% in different studies [12,26].

The included patients received TCZ within was 2.8 (±2) days. However, the mean time from development of symptoms to receiving TCZ was approximately 10 days [17,27]. It had been argued that it is not easy to put a definite time for the initiation of TCZ as the clinical course of COVID-19 is variable [14].

The included patients had high inflammatory markers such as ferritin and CRP levels indicating the role of inflammatory markers in the pathophysiology of hypoxia [2,26,28–30]. Our patients had significant increase in the CRP at the initiation of therapy indicating a severe disease [31]. Following therapy, we observed reduction on the CRP on days 7 and 14. Similarly in a randomized clinical trial of TCZ, there was a reduction in CRP over time in the TCZ arm [32]. Another study showed that CRP levels decreased from 95 to 14 mg/L (p < 0.001) [31]. We had not seen a significant change in lymphocyte count overtime. One study showed that lymphocyte counts increased to 1000/µL from 900/µL (p = 0.036) [31].

The case fatality rate in this study was 15% and was different from 23.2% in a previous study [23] and that study used multiple therapeutics and only cyclosporin was shown to have a significant reduction in mortality [23]. In the Boston Area COVID-19 Consortium (BACC) Bay trial, a randomized controlled study, there was no advantage of using TCZ on the rate of intubation or death with 95% confidence interval of 0.38–1.81 for these outcomes in the TCZ group compared to the placebo group [28]. In a large cohort study, 125 (28.9%) of 433 patient treated with tocilizumab died compared with a death rate of 37.1% in those who did not receive tocilizumab (risk difference, 9.6%) [33]. An additional randomized control trial of patients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen outside ICU, TCZ did not have an effect on day 28 mortality rate [32]. In a case control study, a single 400 mg TCZ dose increased the survival in patients with COVID-19 not requiring mechanical ventilation [34]. The lethality rate was reduced with TCZ in patients not requiring mechanical ventilation [35].

The observed case fatality rate in the current study was 15% and was lower than those reported previously. One of the possible explanations is that 15% of the patients were still in hospital at the time of the reporting. In a study from Saudi Arabia, the overall 30-day mortality was 31.1% in patients who received TCZ and steroid [36]. Another possible explanation is the difference in the time of reporting cases in different studies. In a systematic review that included 10,150 COVID-19 patients who were admitted to ICUs from 24 studies across Europe, Asia, and North America, the mortality rate dropped from 60% at the end of March 2020 to 42% at the end of May 2020 [37]. A third possible explanation is variability in therapies across different countries and centers. In a meta-analysis of 15 studies, the ICU crude mortality rate was 25.7% [38]. Another possible factor is the use of steroid as it had been shown to decrease case fatality rate from 25.7% in standard therapy to 22.9% in the dexamethasone group [39].

This study is a case series of COVID-19 treated with corticosteroid and TCZ. As such the study has few limitations. One of the limitations is the small sample size of 90 cases. In addition, this is a retrospective study with the lack of a concurrent control arm and a control group to elucidate the contribution of TCZ to the therapy of severe COVID-19 cases.

In conclusion, we described the presentation and outcome of hospitalized severe COVID-19 patients treated with both TCZ and corticosteroid. The overall case fatality rate was lower than those cited in meta-analysis. However, there are multiple explanations for such differences. As our understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection continues, the approach and therapeutics are also evolving. In a recent commentary, it was indicated that several studies reported remarkable results with TCZ and it is advisable to have additional studies from additional clinical trials [14].

Footnotes

Data availability statement: Data available upon request.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed to the data gathering, analysis, or drafting the first draft. All authors approved the final draft.

FUNDING

No financial support was provided.

REFERENCES

- [1].Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Yami SS, Rigamonti D. Changes in healthcare managing COVID and non–COVID-19 patients during the pandemic: striking the balance. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;98 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.115147. 115147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nicastri E, D’Abramo A, Faggioni G, De Santis R, Mariano A, Lepore L, et al. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in a paucisymptomatic patient: epidemiological and clinical challenge in settings with limited community transmission, Italy, February 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.11.2000230. 2000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Al-Omari A, Alhuqbani WN, Zaidi ARZ, Al-Subaie MF, AlHindi AM, Abogosh AK, et al. Clinical characteristics of non-intensive care unit COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia: a descriptive cross-sectional study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:1639–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Al Mutair A, Alhumaid S, Alhuqbani WN, Zaidi ARZ, Alkoraisi S, Al-Subaie MF, et al. Clinical, epidemiological, and laboratory characteristics of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients in Saudi Arabia: an observational cohort study. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25:61. doi: 10.1186/s40001-020-00462-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].AlJishi JM, Alhajjaj AH, Alkhabbaz FL, AlAbduljabar TH, Alsaif A, Alsaif H, et al. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 patients in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tirupathi R, Muradova V, Shekhar R, Salim SA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Palabindala V. COVID-19 disparity among racial and ethnic minorities in the US: a cross sectional analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101904. 101904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Al-Tawfiq JA, Leonardi R, Fasoli G, Rigamonti D. Prevalence and fatality rates of COVID-19: what are the reasons for the wide variations worldwide? Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101711. 101711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Al-Tawfiq JA, Sattar A, Al-Khadra H, Al-Qahtani S, Al-Mulhim M, Al-Omoush O, et al. Incidence of COVID-19 among returning travelers in quarantine facilities: a longitudinal study and lessons learned. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;38 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101901. 101901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Al-Tawfiq JA, Hinedi K. The calm before the storm: clinical observations of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) patients. J Chemother. 2018;30:179–82. doi: 10.1080/1120009X.2018.1429236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: a clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pedersen SF, Ho YC. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2202–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI137647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tirupathi R, Bharathidasan K, Areti S, Kaur J, Salim S, Al-Tawfiq JA. The shortcomings of tocilizumab in COVID-19. Infez Med. 2020;28:465–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33257619/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954. 105954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sciascia S, Aprà F, Baffa A, Baldovino S, Boaro D, Boero R, et al. Pilot prospective open, single-arm multicentre study on off-label use of tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38:529–32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32359035/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:10970–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005615117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Radbel J, Narayanan N, Bhatt PJ. Use of tocilizumab for COVID-19-induced cytokine release syndrome: a cautionary case report. Chest. 2020;158:e15–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, Liu X, Liu D, Li J. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID-19: a single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92:814–18. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang S, Li L, Shen A, Chen Y, Qi Z. Rational use of tocilizumab in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40:511–18. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].(Released by National Health Commission & National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine on March 3, 2020). Diagnosis and treatment protocol for novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial version 7) Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:1087–95. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].AlJishi JM, Al-Tawfiq JA. Intermittent viral shedding in respiratory samples of patients with SARS-CoV-2: observational analysis with infection control implications. J Hosp Infect. 2020;107:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Guisado-Vasco P, Valderas-Ortega S, Carralón-González MM, Roda-Santacruz A, González-Cortijo L, Sotres-Fernández G, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes among hospitalized adults with severe COVID-19 admitted to a tertiary medical center and receiving antiviral, antimalarials, glucocorticoids, or immunomodulation with tocilizumab or cyclosporine: a retrospective observational study (COQUIMA cohort) EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100591. 100591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Alsofayan YM, Althunayyan SM, Khan AA, Hakawi AM, Assiri AM. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia: a national retrospective study. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13:920–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Barry M, AlMohaya AE, AlHijji A, Akkielah L, AlRajhi A, Almajid F, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in a MERS-CoV endemic area. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10:214–21. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.200806.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hassoun A, Thottacherry ED, Muklewicz J, Aziz QUA, Edwards J. Utilizing tocilizumab for the treatment of cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;128 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104443. 104443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stone JH, Frigault MJ, Serling-Boyd NJ, Fernandes AD, Harvey L, Foulkes AS, et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2333–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang Y, Lu X, Li Y, Chen H, Chen T, Su N, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1430–4. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O’Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fomina DS, Lysenko MA, Beloglazova IP, Mutovina ZY, Poteshkina NG, Samsonova IV, et al. Temporal clinical and laboratory response to interleukin-6 receptor blockade with tocilizumab in 89 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Pathog Immun. 2020;5:327–41. doi: 10.20411/pai.v5i1.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hermine O, Mariette X, Tharaux PL, Resche-Rigon M, Porcher R, Ravaud P, et al. Effect of tocilizumab vs usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:32–40. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gupta S, Wang W, Hayek SS, Chan L, Mathews KS, Melamed ML, et al. Association between early treatment with tocilizumab and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:41–51. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rossi B, Nguyen LS, Zimmermann P, Boucenna F, Dubret L, Baucher L, et al. Effect of tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a case-control cohort study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13:317. doi: 10.3390/ph13100317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Perrone F, Piccirillo MC, Ascierto PA, Salvarani C, Parrella R, Marata AM, et al. Tocilizumab for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. The TOCIVID-19 prospective phase 2 trial. medRxiv. 2020;18:405. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.01.20119149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sigurgeirsson B, Steingrímsson Ó, Sveinsdóttir S. Prevalence of onychomycosis in Iceland: a population-based study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:467–9. doi: 10.1080/000155502762064665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Armstrong RA, Kane AD, Cook TM. Outcomes from intensive care in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1340–9. doi: 10.1111/anae.15201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Quah P, Li A, Phua J. Mortality rates of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of the emerging literature. Crit Care. 2020;24:285. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR, Mafham M, Bell JL, et al. RECOVERY Collaborative Group Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2021436. NEJMoa2021436 [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]