Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the associations of sociodemographic characteristics and PROMIS domain scores with patient activation among patients presenting for spine surgery at a university-affiliated spine center.

Methods

Patients completed a survey collecting demographic and social information. Patients also completed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) and Patient Activation Measure questionnaires. The associations of PROMIS scores and sociodemographic characteristics with patient activation were assessed using linear and ordinal logistic regression (patient activation stage as ordinal).

Results

A total of 1018 patients were included. Most respondents were white (84%), married (73%), and female (52%). Patients were distributed among the 4 activation stages as follows: stage I, 7.7%; stage II, 12%; stage III, 26%; and stage IV, 55%. Mean (±standard deviation) patient activation score was 70 ± 17 points. Female sex (adjusted coefficient [AC] = 4.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.1, 6.4) and annual household income >$80,000 (OR = 3.7; 95% CI 0.54, 6.9) were associated with higher patient activation scores. Lower patient activation scores were associated with worse PROMIS Depression (AC = −0.31; 95% CI −0.48, −0.14), Fatigue (OR = −0.19; 95% CI −0.33, −0.05), Pain (OR = 0.22; 95% CI 0.01, 0.43), and Social Satisfaction (OR = 0.33; 95% CI 0.14, 0.51) scores.

Conclusion

Depression and socioeconomic status, along with PROMIS Pain, Fatigue, and Social Satisfaction domains, were associated with patient activation. Patients with a greater burden of depressive symptoms had lower patient activation; conversely, women and those with higher income had greater patient activation.

Level of evidence

Level 1.

Keywords: Depression, Patient activation, Socioeconomic status, Spine surgery

1. Introduction

In a patient-centered health care model, successful medical treatment centers on the relationship between health care providers and patients.1 Delivery of quality care involves a health care team, as well as active participation by patients. For patients to assume an active role, they need the motivation, knowledge, skills, and confidence to make effective decisions regarding their care. Hibbard et al.2 conceptualized these attributes as “patient activation.”

To assess the degree of patient activation, Hibbard et al.2 developed the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) questionnaire, which ranks patients from 0 (no activation) to 100 (high activation). Since the development of the PAM, studies have found that increased patient activation is positively correlated with better health outcomes. Skolasky et al.3 reported that patients with high activation scores had better adherence to physical therapy recommendations than those with low scores. In a cohort of patients with diabetes, Rask et al.4 found that higher levels of patient activation were associated with increased likelihood of following up. Although the importance of patient activation is recognized, interventions to support patients in this area have not been well-developed or implemented.

Despite growing recognition of patient activation, few studies have explored the influences of depression, socioeconomic status, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) on patient activation. A recent study suggested that a lack of patient involvement, decision making, and resilience may explain the mechanism for poor outcomes in surgical spine patients with certain psychosocial risk factors.5 Likewise, depressive symptoms have been associated with poor outcomes after spine surgery.6

We analyzed the associations of sociodemographic characteristics and health and wellness with patient activation among those presenting for spine surgery evaluation at a university-affiliated spine center. We hypothesized that depression would be negatively associated with patient activation, and income would be positively associated with patient activation.

2. Material and methods

Our institutional review board approved this study.

2.1. Participants

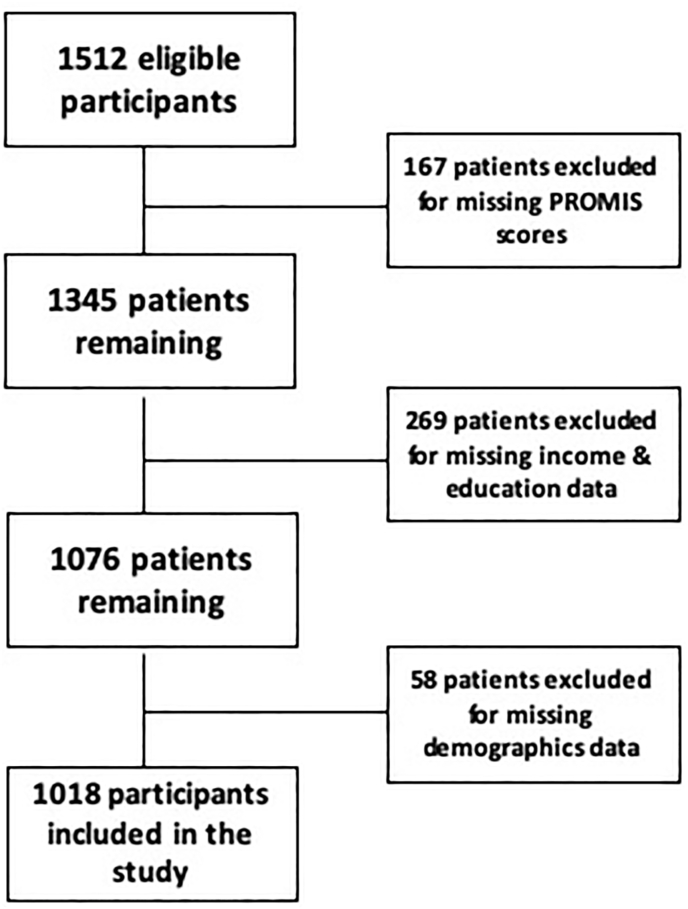

Patients presenting to our spine center from October 2014 to August 2019 for evaluation and screening for prospective surgical treatment were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1). We included patients who were older than 18 years, English-speaking, and able to provide informed consent. We excluded patients with a history of spine surgery because they have a markedly different clinical recovery course than those undergoing primary surgery. We also excluded patients with missing sociodemographic data and PROMIS scores. A total of 1018 patients were included in our study. Our study population presented with a wide variety of clinical diagnoses. Approximately 72% of patients underwent surgery, and 28% received nonoperative treatment (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Participant selection flow diagram for participants who presented to a single spine center from October 2014 to August 2019 for evaluation and screening for prospective surgical treatment; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 1018 patients evaluated for surgical spine treatment from October 2014 to August 2019.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 1018) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 59 ± 14a |

| Sex | |

| Female | 533 (52) |

| Male | 485 (48) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 875 (86) |

| African American | 144 (14) |

| Hispanic | 24 (2.4) |

| Relationship status | |

| Not in relationship | 273 (27) |

| In a relationship | 745 (73) |

| Highest educational level | |

| High school diploma | 423 (42) |

| College degree | 316 (31) |

| Graduate degree | 279 (27) |

| Annual household income, $ | |

| <30,000 | 199 (20) |

| 30,000–80,000 | 327 (32) |

| >80,000 | 492 (48) |

| Employed | |

| No | 574 (56) |

| Yes | 444 (44) |

| Nonoperative patients | 283 (28) |

| Operative patients | 735 (72) |

| Surgical procedures | |

| Instrumentation | 478 (47) |

| Fusion | 439 (43) |

| Laminectomy complete | 192 (19) |

| ACDF | 154 (15) |

| PSO | 28 (3) |

| VCR | 10 (0,1) |

| Patient activation stage | |

| I | 78 (7.7) |

| II | 119 (12) |

| III | 263 (26) |

| IV | 558 (55) |

| PROMIS domain | |

| Pain | 65 ± 8a |

| Physical function | 36 ± 7a |

| Fatigue | 57 ± 10a |

| Anxiety | 54 ± 10a |

| Depression | 51 ± 10a |

| Sleep | 55 ± 9a |

| Social satisfaction | 41 ± 9a |

ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion; PAM, Patient Activation Measure; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System; PSO, pedicle subtraction osteotomy; VCR, vertebral column resection.

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.2. Assessments

Patients were assessed at their initial presentation to our orthopaedic spine center. This assessment occurred before surgery. All research-related events occurred in a private research room to ensure confidentiality.

2.2.1. Patient activation

Patient activation was assessed using the PAM-13 questionnaire.2 The PAM-13 is a participant-completed 13-item questionnaire that addresses key psychologic factors and personal competencies. We used a modified scale that was devised to increase the clinical utility of the measure.7 Validity of the scale has been established through correlation with key clinical indicators, such as overall health and self-management behaviors.7 Participants are asked to rate their agreement on health statements ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Scores on the PAM-13 are continuous measures ranging from 0 (no activation) to 100 (high activation). A previous report of the use of PAM-13, in a national probability sample of more than 1500 patients with and without chronic illness, found a mean score of 55 points (range, 40–80).2 In patients about to undergo surgery for low back pain, the PAM-13 has been shown to be a reliable (intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.87) and valid assessment of patient activation.8, 9, 10

The 4 stages of patient activation are defined as disengaged and overwhelmed (stage I: PAM-13 scores, 0–47.0), becoming aware but still struggling (stage II: PAM-13 scores, 47.1–55.1), taking action (stage III: PAM-13 scores, 55.2–72.4), and maintaining behavior and pushing further (stage IV: PAM-13 scores, 72.5–100).2 In our study group, the distribution of patients among the 4 patient activation stages was as follows: stage I, 78 patients (7.7%); stage II, 119 patients (12%); stage III, 263 patients (26%); and stage IV, 558 patients (55%) (Table 1). The mean (±standard deviation) patient activation score was 70 ± 17 points.

2.2.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)

PRO measures use patient feedback to help structure treatment strategies and predict patient outcomes. We used the PROMIS questionnaire to assess the following health domains: Depression, Anxiety, Pain, Fatigue, Sleep Disturbance, Physical Function, and Satisfaction with Participation in Social Roles and Activities (herein, Social Satisfaction). Each measure is scored on a scale of 0–100, and all measures were recorded preoperatively. Higher scores indicate worse Depression, Anxiety, Pain, Fatigue, and Sleep Disturbance. Conversely, higher scores indicate more favorable Physical Function and Social Satisfaction. A recent study found PROMIS to be a valid measure of PROs in patients undergoing adult spinal deformity surgery.9

2.2.3. Sociodemographic characteristics

We used a questionnaire to collect patient demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity) and social characteristics (marital status, highest level of education, self-reported household income, and employment status). Household income data were collected as a self-reported measure using the following categories: less than $30,000, between $30,000 and $80,000, more than $80,000, or do not know/refused to answer. Our study population was predominantly non-Hispanic white (84%) and female (52%). The mean (±standard deviation) patient age was 59 ± 14 years (Table 1). Patients’ self-reported relationship status was dichotomized as “not in a relationship” (single, widowed, divorced, or separated) or “in a relationship” (married or living with partner). Nearly 73% of patients (N = 745) reported being in a relationship, and the remainder identified as single, divorced, widowed, or separated.

2.3. Statistical analyses

To examine the associations of sociodemographic characteristics with patient activation, we classified patients according to their PAM-13 responses, using both total score and stage of activation. To test the associations between patient activation score (a continuous measure) and PROMIS health domain scores and sociodemographic characteristics, we used linear regression methods, with patient activation score as the dependent variable. To test the associations between patient activation stage (an ordinal measure) and PROMIS scores and sociodemographic characteristics, we used ordinal logistic regression, with stage as the dependent variable. Multivariate regression was used to analyze the interactions between multiple PROMIS domains, sociodemographic characteristics, and patient activation. All analyses were performed with Stata, version 16.0, software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Significance was set at p < 0.05. Variables with p < 0.20 were included in multivariate analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Patient activation score

3.1.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

Annual household income >$80,000 (adjusted coefficient [AC] 3.7; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.54, 6.9; p = 0.02) and female sex (AC 4.3; 95% CI 2.1, 6.4; p < 0.01) were associated with higher patient activation scores. Patient activation score was not associated with age, attainment of a college degree or graduate degree, marital status, or employment status (Table 2). Race/ethnicity was not associated with patient activation score when comparing non-Hispanic white patients with Hispanic (p = 0.53) and non-Hispanic African American patients (p = 0.40).

Table 2.

Associations between patient activation score and sociodemographic characteristics of 1018 patients evaluated for surgical spine treatment from October 2014 to August 2019.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted |

Adjusteda |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | Coefficient (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | −0.08 (−0.14, −0.02) | 0.01 | −0.06 (−0.14, 0.03) | 0.21 |

| Female sex | 2.8 (1.1, 4.5) | <0.01 | 4.3 (2.1, 6.4) | <0.01 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | Referent | Referent | ||

| African American | −2.1 (−4.8, −0.06) | 0.11 | −1.3 (−4.3, 1.7) | 0.40 |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (−5.5, 6.5) | 0.88 | −2.2 (−8.9, 4.6) | 0.53 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Not in relationship | Referent | Referent | ||

| In relationship | −0.29 (−2.3, 1.7) | 0.77 | −2.1 (−4.6, 0.48) | 0.11 |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| High school diploma | Referent | Referent | ||

| College degree | 1.3 (−0.76, 3.4) | 0.22 | −0.88 (−3.4, 1.6) | 0.48 |

| Graduate degree | 6.7 (4.5, 8.9) | <0.01 | 2.6 (−0.09, 5.3) | 0.06 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||

| <30,000 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 30,000–80,000 | 3.5 (0.70, 6.3) | 0.01 | 1.8 (−1.2, 4.8) | 0.24 |

| >80,000 | 6.8 (4.2, 9.4) | <0.01 | 3.7 (0.54, 6.9) | 0.02 |

| Employed | ||||

| Yes | Referent | Referent | ||

| No | 5.6 (3.8, 7.4) | <0.01 | 1.9 (−0.52, 4.3) | 0.12 |

| PROMIS domains | ||||

| Anxiety | −0.34 (−0.43, −0.24) | <0.01 | −0.004 (−0.16, 0.16) | 0.97 |

| Depression | −0.43 (−0.52, −0.34) | <0.01 | −0.31 (−0.48, −0.14) | <0.01 |

| Fatigue | −0.37 (−0.46, −0.27) | <0.01 | −0.19 (−0.33, −0.05) | <0.01 |

| Pain | −0.27 (−0.38, −0.15) | <0.01 | 0.22 (0.01, 0.43) | 0.04 |

| Physical function | 0.33 (0.20, 0.45) | <0.01 | −0.13 (−0.34, 0.08) | 0.23 |

| Sleep disturbance | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.04) | 0.24 | ||

| Social satisfaction | 0.44 (0.33, 0.54) | <0.01 | 0.33 (0.14, 0.51) | <0.01 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

All variables with p < 0.20 in unadjusted analysis were included in the adjusted analysis.

3.1.2. PROMIS scores

Lower patient activation scores were associated with worse PROMIS Depression (AC −0.31; 95% CI −0.48, −0.14; p < 0.01), Fatigue (AC −0.19; 95% CI −0.33, −0.05; p < 0.01), Pain (AC 0.22; 95% CI 0.01, 0.43; p = 0.04), and Social Satisfaction (AC 0.33; 95% CI 0.14, 0.51; p < 0.01) scores (Table 2). Patient activation scores were not associated with PROMIS Physical Function or Anxiety scores.

3.2. Patient activation stage

3.2.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

The following sociodemographic characteristics were associated with patient activation stage: sex (odds ratio [OR] 1.75; 95% CI 1.35, 2.26; p = 0.01), annual income >$80,000 (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.18, 2.50; p = 0.01), and employment (OR 1.37; 95% CI 1.03, 1.84; p = 0.03) (Table 3). Conversely, age, marital status, attainment of a college or graduate degree, Hispanic ethnicity, African American race (p = 0.63), and annual household income <$80,000 were not associated with patient activation stage.

Table 3.

Associations between patient activation stage and sociodemographic characteristics of 1018 patients evaluated for surgical spine treatment, from October 2014 to August 2019.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.02 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.53 |

| Female Sex | 1.37 (1.13, 1.66) | <0.01 | 1.75 (1.35, 2.26) | 0.01 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||

| Caucasian | Referent | Referent | ||

| African American | 0.84 (0.64, 1.11) | 0.15 | 0.91 (0.64, 1.31) | 0.63 |

| Hispanic | 1.35 (0.68, 2.67) | 0.39 | 0.83 (0.36, 1.93) | 0.67 |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Not in a relationship | Referent | Referent | ||

| In a relationship | 1.03 (0.83, 1.23) | 0.33 | 0.79 (0.58, 1.08) | 0.14 |

| Highest educational level | ||||

| High school diploma | Referent | Referent | ||

| College degree | 1.29 (1.04, 1.62) | 0.02 | 1.04 (0.77, 1.39) | 0.80 |

| Graduate degree | 2.09 (1.62, 2.68) | <0.01 | 1.32 (0.95, 1.83) | 0.10 |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||

| <30,000 | Referent | Referent | ||

| 30,000–80,000 | 0.45 (0.15, 0.74) | <0.01 | 1.37 (0.97, 1.95) | 0.07 |

| >80,000 | 0.80 (0.52, 1.1) | <0.01 | 1.72 (1.18, 2.50) | 0.01 |

| Employed | ||||

| No | Referent | Referent | ||

| Yes | 1.84 (1.51, 2.24) | <0.01 | 1.37 (1.03, 1.84) | 0.03 |

| PROMIS domains | ||||

| Anxiety | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.01 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 0.50 |

| Depression | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | <0.01 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | 0.00 |

| Fatigue | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.01 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.20 |

| Pain | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.01 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.30 |

| Physical function | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | <0.01 | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.20 |

| Sleep disturbanceb | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.54 | ||

| Social satisfaction | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | <0.01 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.06) | 0.01 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.

Race was included in the multivariate model because 1 component of race met the p < 0.20 threshold.

Sleep disturbance was excluded from the multivariate model because p > 0.20 in the univariate model.

3.2.2. PROMIS scores

Patient activation stage was associated with PROMIS Depression (OR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.94, 0.98; p = 0.00) and Social Satisfaction (OR 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01, 1.06; p = 0.01) but not with Sleep Disturbance (p = 0.54), Anxiety (p = 0.50), Fatigue (p = 0.20), Pain (p = 0.30), and Physical Function (p = 0.20) (Table 3).

4. Discussion

In patients presenting to an orthopaedic spine center for surgical care, we found a significant association between patient activation and depression. Moreover, patient activation was associated with female sex, annual income >$80,000, and PROMIS Depression, Pain, Fatigue, and Social Satisfaction. These associations persisted after adjustment for other key variables (marital status, highest level of education, race/ethnicity, household income, PROMIS domain scores, sex, and employment status).

The role of patient activation and the positive effect it has on outcomes in patients with depression has been established.10 Furthermore, studies have shown associations of socioeconomic status and depression with poor patient outcomes. Fowles et al.8 found that higher annual income is associated with higher patient activation scores. In patients with diverse spinal abnormalities, depression is common and is associated with poor clinical outcomes in spine surgery.11,12 Dersh et al.13 analyzed 1323 patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders and found that approximately 56% were also diagnosed with major depressive disorder. A multicenter study conducted by the International Spine Study Group reported that 25% of patients with adult spinal deformity also had a preoperative diagnosis of depression.14 Sacks et al.10 proposed that higher patient activation predicts better depression outcomes, lower depression severity, and higher depression remission and treatment response. In accordance with the research, our findings suggest that patient activation mediates the association between depression, socioeconomic status, and patient outcomes.

High patient activation has been associated with better adoption of positive health behaviors and increased likelihood of positive health outcomes in various medical and surgical conditions. In a sample of patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery, Skolasky et al.3 reported a relationship between high patient activation and increased participation and engagement in physical therapy. Moreover, patients with high preoperative patient activation were more likely to achieve clinically meaningful reductions in pain and disability and improvements in health status.15 Additionally, Harris et al.16 found that higher patient activation scores were associated with higher satisfaction, postoperatively. In a survey of nearly 25,000 adult patients, high patient activation was associated with 12 of 13 beneficial health outcomes, including reduced likelihood of emergency department visits and obesity and increased likelihood of undergoing breast cancer screening.17 The relationship between patient activation and health behavior was shown in a group of 1108 randomly selected adults with diabetes.18 Remmers et al.18 showed that high patient activation was associated with better HbA1c control and greater likelihood of receiving HbA1c and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol testing. The authors concluded that assessment of patient activation could be used to identify patients at risk for poor outcomes. Our findings highlight the negative association between lower patient activation stages and various sociodemographic risk factors on surgical outcomes; yet, surgical patients are not universally screened for these risk factors. Therefore, patient optimization for spine surgery candidates should include screening for lower activation stages, along with the other risk factors identified in our study.

Given the strong evidence supporting the association between patient activation and health behaviors and outcomes, interventions have been designed to increase patient activation. In recent years, effectiveness has been documented of interventions directly targeting patient activation and its correlated psychologic factors and personal competencies. The aim of these interventions is to improve health behavior using empowerment strategies,19 educational sessions,20 and self-management strategies.21,22 These interventions have shown that increases in patient activation can lead to improved adoption of positive health behaviors in various patient populations. Hibbard et al.23 examined a cross-section of patients with various chronic diseases and reported that increases in patient activation were related to positive changes in various self-management behaviors. These findings persisted even when the behavior in question was not being performed preoperatively. When the behavior was already being performed preoperatively, an increase in patient activation was associated with maintaining a high level of the behavior over time. Skolasky et al.24 developed a brief health behavior change counseling intervention according to the principles of motivational interviewing that increases patient activation and improves outcomes among those undergoing lumbar spine surgery. Ultimately, interventions aimed to improve patient activation may help mediate the effects of various risk factors on patient outcomes.

Our study had limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, our patient sample was from a single academic spine center, and patients presenting to our service may not be typical of the patients who present to a community hospital. Compared with a national study's mean PAM-13 score of 55,7 patients presenting for elective surgery at our academic medical center had a mean patient activation score of 70 ± 17 points. Because these patients have already navigated the complex health care system, it is likely that a number of patients have a high activation stage. In fact, more than three-fourths of patients score in the top two stages of activation. However, our center comprises 2 hospitals (a tertiary care center and an affiliated community hospital), which may ameliorate this limitation. Second, reliance on self-reported measures may lead to bias. Subgroups of the population may have been differentially affected by this bias, leading to spurious associations between patient activation and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Third, most patients in our sample were non-Hispanic white. Although this underrepresentation of racial/ethnic minorities may limit subgroup analyses, especially in examining the influence of patient activation on individual behaviors, our sample of non-Hispanic white patients is similar to other published observational studies of those presenting for spine surgery.25 A national study of elective spine surgery for 39,884 US Medicare beneficiaries found that 94.5% of patients, who underwent elective lumbar surgeries between 2004 and 2007, were non-Hispanic white.25 Moreover, given the strength of our findings regarding differences in patient activation, we feel confident of their validity. Future work to examine the potential mediating effect that patient activation may have on the relationship between depression and socioeconomic status to influence health behavior and outcome after spine surgery will require oversampling of these groups.

5. Conclusion

Among patient presenting for spine surgery, depression and socioeconomic status, along with PROMIS Pain, Fatigue, and Social Satisfaction domains were associated with patient activation. Patients with a greater burden of depressive symptoms had lower patient activation; conversely, those with higher income and women had greater patient activation.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval

This study received approval from our institutional review board. IRB committee: IRB-X. IRB number: IRB00135145.

Consent to participate

As authors, Emmanuel McNeely, Rahul Sachdev, Rafa Rahman, Bo Zhang, and Richard Skolasky consent to participate.

Consent for publication

As authors, Emmanuel McNeely, Rahul Sachdev, Rafa Rahman, Bo Zhang, and Richard Skolasky consent to submit this paper for publication.

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

N/A.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Emmanuel McNeely, Rahul Sachdev, Rafa Rahman, and Richard L. Skolasky. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Emmanuel McNeely, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

For their editorial assistance, we thank Jenni Weems, MS, Kerry Kennedy, BA, and Rachel Box, MS, in the Editorial Services group of The Johns Hopkins Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. This research was supported by NIH National Institute on Aging under Award Number P01AG066603.

Footnotes

This study received approval from our institutional review board. IRB committee: IRB-X, IRB number: IRB00135145.

References

- 1.Berenson R.A., Hammons T., Gans D.N. A house is not a home: keeping patients at the center of practice redesign. Health Aff. 2008;27:1219–1230. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hibbard J.H., Stockard J., Mahoney E.R., Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skolasky R.L., Mackenzie E.J., Wegener S.T., Riley L.H., III Patient activation and adherence to physical therapy in persons undergoing spine surgery. Spine. 2008;33:E784–E791. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818027f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rask K.J., Ziemer D.C., Kohler S.A., Hawley J.N., Arinde F.J., Barnes C.S. Patient activation is associated with healthy behaviors and ease in managing diabetes in an indigent population. Diabetes Educat. 2009;35:622–630. doi: 10.1177/0145721709335004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Block A.R., Marek R.J., Ben-Porath Y.S. Patient Activation mediates the association between psychosocial risk factors and spine surgery results. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2019;26:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s10880-018-9571-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beck A.T., Ward C.H., Mendelson M., Mock J., Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hibbard J.H., Mahoney E.R., Stockard J., Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fowles J.B., Terry P., Xi M., Hibbard J., Bloom C.T., Harvey L. Measuring self-management of patients' and employees' health: further validation of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM) based on its relation to employee characteristics. Patient Educ Counsel. 2009;77:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raad M., Jain A., Huang M. Validity and responsiveness of PROMIS in adult spinal deformity: the need for a self-image domain. Spine J. 2019;19:50–55. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacks R.M., Greene J., Hibbard J.H., Overton V. How well do patient activation scores predict depression outcomes one year later? J Affect Disord. 2014;169:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvin M.D., Miller J.A., Sundar S. The impact of preoperative depression on quality of life outcomes after posterior cervical fusion. Spine J. 2015;15:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tetreault L., Nagoshi N., Nakashima H. Impact of depression and bipolar disorders on functional and quality of life outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative cervical myelopathy: analysis of a combined prospective dataset. Spine. 2017;42:372–378. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dersh J., Gatchel R.J., Mayer T., Polatin P., Temple O.R. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with chronic disabling occupational spinal disorders. Spine. 2006;31:1156–1162. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216441.83135.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theologis A.A., Ailon T., Scheer J.K. Impact of preoperative depression on 2-year clinical outcomes following adult spinal deformity surgery: the importance of risk stratification based on type of psychological distress. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25:477–485. doi: 10.3171/2016.2.SPINE15980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skolasky R.L., Mackenzie E.J., Wegener S.T., Riley L.H., III Patient activation and functional recovery in persons undergoing spine surgery. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2011;93:1665–1671. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris A.B., Kebaish F., Riley L.H., Kebaish K.M., Skolasky R.L. The engaged patient: patient activation can predict satisfaction with surgical treatment of lumbar and cervical spine disorders. J Neurosurg Spine. 2020 doi: 10.3171/2019.11.SPINE191159. Epub ahead of print, Feb 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greene J., Hibbard J.H. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:520–526. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Remmers C., Hibbard J., Mosen D.M., Wagenfield M., Hoye R.E., Jones C. Is patient activation associated with future health outcomes and healthcare utilization among patients with diabetes? J Ambul Care Manag. 2009;32:320–327. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ba6e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alegria M., Polo A., Gao S. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Med Care. 2008;46:247–256. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158af52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morisky D.E., Bowler M.H., Finlay J.S. An educational and behavioral approach toward increasing patient activation in hypertension management. J Community Health. 1982;7:171–182. doi: 10.1007/BF01325513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams G.C., McGregor H., Zeldman A., Freedman Z.R., Deci E.L., Elder D. Promoting glycemic control through diabetes self-management: evaluating a patient activation intervention. Patient Educ Counsel. 2005;56:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skolasky R.L., Mackenzie E.J., Riley L.H., III, Wegener S.T. Psychometric properties of the Patient Activation Measure among individuals presenting for elective lumbar spine surgery. Qual Life Res: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2009;18:1357–1366. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9549-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibbard J.H., Mahoney E.R., Stock R., Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1443–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skolasky R.L., Maggard A.M., Li D., Riley L.H., III, Wegener S.T. Health behavior change counseling in surgery for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Part II: patient activation mediates the effects of health behavior change counseling on rehabilitation engagement. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh S., Sparapani R., Wang M.C. Variations in 30-day readmissions and length of stay among spine surgeons: a national study of elective spine surgery among US Medicare beneficiaries. J Neurosurg Spine. 2018;29:286–291. doi: 10.3171/2018.1.SPINE171064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.