Abstract

Objective

Previous studies have unveiled a relationship between the severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pneumonia and obesity. The aims of this multicenter retrospective cohort study were to disentangle the association of BMI and associated metabolic risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and current smoking status) in critically ill patients with COVID‐19.

Methods

Patients admitted to intensive care units for COVID‐19 in 21 centers (in Europe, Israel, and the United States) were enrolled in this study between February 19, 2020, and May 19, 2020. Primary and secondary outcomes were the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) and 28‐day mortality, respectively.

Results

A total of 1,461 patients were enrolled; the median (interquartile range) age was 64 years (40.9‐72.0); 73.2% of patients were male; the median BMI was 28.1 kg/m2 (25.4‐32.3); a total of 1,080 patients (73.9%) required IMV; and the 28‐day mortality estimate was 36.1% (95% CI: 33.0‐39.5). An adjusted mixed logistic regression model showed a significant linear relationship between BMI and IMV: odds ratio = 1.27 (95% CI: 1.12‐1.45) per 5 kg/m2. An adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model showed a significant association between BMI and mortality, which was increased only in obesity class III (≥40; hazard ratio = 1.68 [95% CI: 1.06‐2.64]).

Conclusions

In critically ill COVID‐19 patients, a linear association between BMI and the need for IMV, independent of other metabolic risk factors, and a nonlinear association between BMI and mortality risk were observed.

Study Importance.

What is already known?

-

►

Early evidence has linked the overall severity of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) with older age, male sex, and preexisting chronic conditions such as cancer and chronic renal, liver, respiratory, and cardiovascular disease.

-

►

Some studies have also found an overall association of disease severity with obesity and other metabolic risk factors, including diabetes, hypertension, and smoking.

-

►

A wider geographic representation across centers with variable prevalence of obesity is needed.

What does this study add?

-

►

We showed a significant relationship between BMI and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV): adjusted odds ratio = 1.27 (95% CI: 1.12‐1.45) in the whole cohort and 1.65 (95% CI: 0.97‐2.79) per 5 kg/m2 in female patients under the age of 50 years.

-

►

The adjusted Cox regression model showed a significant association between BMI and 28‐day all‐cause mortality, which was increased only in obesity class III (≥40 kg/m2; adjusted hazard ratio = 1.68 [95% CI: 1.06‐2.64]).

How might these results change the focus of clinical practice?

-

►

We observed a linear association between BMI and the need for IMV in COVID‐19 patients in intensive care units across multiple countries, independent of other metabolic risk factors, and a nonlinear association between BMI and mortality risk.

-

►

These findings will help to determine the risk of severe COVID‐19 pneumonia in all BMI categories in order to provide clear guidance for specific prevention, including vaccination in patients at highest risk.

INTRODUCTION

Eighteen months after the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has expanded globally, having already affected more than 150 million individuals worldwide and having claimed more than 3 million lives (1). Identifying risk factors of worse outcomes is essential for reducing the future overall burden of COVID‐19 on the health system and enforcing prevention efforts in populations at higher risk. Early evidence has linked the overall severity of COVID‐19 with older age, male sex, and preexisting chronic conditions such as cancer and chronic renal, liver, respiratory, and cardiovascular disease (2, 3, 4). Numerous studies have also found an overall association of disease severity with obesity (5, 6, 7, 8, 9) and other metabolic risk factors, including diabetes (2, 5, 10, 11), hypertension (3), and smoking (12). One distinct feature of COVID‐19 is pneumonia and the frequent need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), resulting in a great strain on intensive care resources worldwide (13).In Simonnet et al. (14), we reported that the need for IMV gradually increased with BMI in COVID‐19 patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU). The association between obesity and the need for IMV also has been found to be statistically significantly in four independent studies (15, 16, 17, 18) in contrast with other studies (19, 20, 21). Some reports have suggested that the relationship between BMI and COVID‐19 severity might be restricted to younger patients (22, 23, 24, 25). Based on existing data, public health agencies in Europe and the United States have issued guidelines that include obesity as an increased risk factor of severe COVID‐19 (26, 27, 28). Likewise, the COVID‐19 pandemic has already impacted people living with obesity in multiple ways, ranging from food shortages and insecurity, reduced physical activity during lockdown, anxiety from cancellation of care, and mental health issues compounded by isolation (29). Therefore, more global data are needed to determine the risk of severe COVID‐19 pneumonia across all BMI categories in order to provide clear guidance and inform patient care (30). A wider geographic representation across centers and countries with variable prevalence of obesity is also needed to ensure the validity and generalizability of the findings.

This multicenter, international, retrospective cohort study was designed to examine the relationship between BMI and COVID‐19 pneumonia severity, as defined by the need for IMV (primary outcome) and the 28‐day all‐cause mortality rate (secondary outcome) among patients admitted to an ICU. The study’s secondary objectives were to disentangle the influence of BMI from other metabolic risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status, as well as to investigate the modifying effects of age and sex on this relationship.

METHODS

The BMI‐SARS‐CoV‐2 study was a multicenter, international, retrospective cohort study designed to investigate the relationship between BMI and the need for IMV among adult patients admitted to an ICU for COVID‐19 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04391738; sponsored by the Lille University Hospital, Lille, France). The study complied with the standard operating procedures in place, in accordance with the European Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) and, upon its entry into force, Regulation (EU) 2016/679 (also referred to as the General Data Protection Regulation) and French CNIL frameworks n° MR004 regarding the processing of personal data in clinical studies. The institutional review board from other centers in the US and Israel approved the retrospective case series as minimal‐risk research using data collected for routine clinical practice and waived the requirement for informed consent. The study report followed the Strengthening Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.

Data sources

Centers that routinely registered BMI in patients admitted to the ICU for COVID‐19 during the study period were identified among a preexisting network of ICUs in France (French Network of Simulation in Intensive Care) or through the published literature. The Medline database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and the Clarivate Web of Science database (https://webofknowledge.com) were searched using the following keywords to identify cohort studies that reported BMI in patients admitted to an ICU for COVID‐19: “intensive care;” “COVID‐19;” “SARS‐CoV‐2;” “obesity;” and “body mass index.” Overall, 27 centers from seven countries (France, China, Belgium, the US, Israel, Italy, and Spain) were identified and contacted, and 21 agreed to participate as follows: France (13), Italy (3), the US (2), Israel (1), Belgium (1), and Spain (1). In order to minimize data input errors or possible bias, each participating center received a standardized template based on the registered study design, which was accompanied by a glossary of required variables and a data‐entry support guide, in order to enforce the homogeneity and validity of the data and to lower the number of missing values. At each center, investigators extracted primary data from medical records from all consecutive patients admitted to an ICU for COVID‐19 between February 19, 2020, and May 11, 2020. Data cleaning involved repeated cycles of screening, diagnosing, treatment, and documentation of this process. Finally, each center removed all potential identifiers from the data set, which was assembled in random order and protected with a password prior to being sent to the study sponsor in accordance with the data transfer agreement. Individual data were eventually aggregated by the sponsor center, in random order, with an inclusion number corresponding to each center.

Study patients and covariates

Participants were patients admitted to an ICU for confirmed COVID‐19‐related pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome, as diagnosed on the basis of World Health Organization (WHO) guidance (31). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was defined as a positive result on real‐time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens, as previously described (32). All primary data were reviewed and collected by trained physicians. The variables collected at the time of admission included sex, age, height, and body weight, measured or estimated by a physician, as well as prespecified metabolic risk factors such as current smoking status and history of diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Other associated comorbidities included cardiovascular disease (including chronic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral arterial disease), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and immunodeficiency (including steroid use, preexisting immunological condition, or current chemotherapy in individuals with cancer). Current or previous history of cancer and chronic kidney disease were also collected as well as the use of angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and antidiabetic treatment, with or without insulin.

Exposure of interest

The exposure of interest was BMI, defined as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared and measured at the time of admission to an ICU. BMI was analyzed as a continuous variable or classified in BMI categories as defined by the WHO (33): underweight (under 18.5); normal weight (18.5‐24.9); overweight (25‐29.9); obesity class I (30‐34.9); obesity class II (35‐39.9); and obesity class III (40 and above). In some subgroup analyses, underweight and normal weight categories on one hand and obesity class I, II and III categories on the other hand were combined as lean (under 25) and obesity (30 and above), respectively, in order to gather sufficient numbers of patients.

Outcomes and follow‐up

The primary outcome was the need for IMV prior to or after ICU admission. The secondary outcome was all‐cause mortality rate within 28 days following ICU admission. Data were collected from February 19, 2020, to May 19, 2020. The following events were collected: the date of ICU admission, the number of days between admission and intubation (0 days means that IMV occurred the day of admission), and the number of days spent under IMV (1 day means that the patient was extubated after a day spent under IMV). When the patient was tracheotomized, the return to spontaneous ventilation with ambient air was considered as an extubation event. Patient status at last news (deceased, discharged from, or still hospitalized in ICU) and the number of days that elapsed since ICU admission were also collected.

Statistical analysis

Having examined histograms, all quantitative variables were summarized by median and quartiles, and groups were compared using a Mann‐Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers (percentage) and compared by χ2 test with the use of Yates continuity correction.

The association of BMI with the need for IMV in patients with COVID‐19 admitted to intensive care was assessed by using a mixed logistic regression model, including center as a random effect. BMI was analyzed as a categorical variable using modified WHO classification and as a continuous variable. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated using the lean category (BMI < 25) as reference or per 5‐kg/m2 increase in BMI. The log‐linearity assumption was examined using restricted cubic spline functions.

A multivariable analysis using a mixed logistic regression model was performed to adjust the association between BMI and IMV on predefined confounding variables, including age, sex, and the presence of prespecified metabolic risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status). Finally, in a secondary and exploratory analysis, we investigated the heterogeneity in the association of BMI and IMV into the mixed logistic regression models according to sex (male vs. female) and age subgroups (<50 years, 50‐74.9 years, and ≥75 years).

The association between BMI and 28‐day all‐cause mortality was assessed by using a Cox proportional hazards regression model with a random center effect (frailty model) with and without predefined confounding variables. Similar to previous analyses, BMI was analyzed as a categorical variable using modified WHO classification and a continuous variable. Owing to the fact that the log‐linearity assumption was not satisfied, only results for BMI, treated as a categorical variable, were reported. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the lean category (BMI < 25) as reference.

Primary analyses for both outcomes were done after handling missing values by multiple imputations. Imputation procedure was performed using a regression‐switching approach (chained equations with m = 10 imputations) under missing‐at‐random assumption using all patient characteristics with a predictive mean‐matching method for quantitative variables and a logistic regression model (binary, ordinal, or multinomial) for categorical variables. Regression estimates obtained in the different imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules. An available‐case sensitivity analysis was also performed. Statistical testing was done at the two‐tailed α level of 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Characteristics of study population

A total of 1,461 individuals admitted to an ICU with confirmed COVID‐19 in 21 institutions from six countries, including France (13), Italy (3), the US (2), Israel (1), Belgium (1), and Spain (1), were included in this study (see study flowchart [Supporting Information Figure S1]). Table 1 details the characteristics of the participants who required IMV and those who did not, as well as the prevalence of preexisting chronic conditions and treatments at the time of admission. Overall, study participants were predominantly male individuals (73.2%), with an age varying from 19 to 93 years and a median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of 64 (56‐73) years. The median (IQR) BMI was 28.1 (25.4‐32.3) with an overall prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30) of 37.5%. The study participants had markedly higher BMI, after adjustment for sex and age, than those observed in the general population of the corresponding country (Supporting Information Figure S2).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics at baseline of patients admitted to an ICU in the whole cohort (n = 1,461) and in patients who did (n = 1,080) or did not (n = 381) require IMV

| N | All patients (n = 1,461) | Non‐IMV (n = 381) | IMV (n = 1,080) | p value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, no. (%) | 1,461 | 1,070 (73.2) | 246 (64.6) | 824 (76.3) | <0.001 |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 1,461 | 64 (56‐73) | 62 (53‐75) | 65 (56‐72) | 0.48 |

| Age by classes, no. (%) | 1,461 | <0.001 | |||

| <50 years | 210 (14.4) | 74 (19.4) | 136 (12.6) | ||

| 50‐74 years | 968 (66.3) | 211 (55.4) | 757 (70.1) | ||

| ≥75 years | 283 (19.4) | 96 (25.2) | 187 (17.3) | ||

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 1,375 | 28.1 (25.4‐32.3) | 27.7 (24.7‐31.2) | 28.4 (25.4‐32.6) | 0.001 |

| BMI, by WHO classes, no. (%) | 1,375 | 0.005 b | |||

| <18.5 | 8 (0.6) | 4 (1.1) | 4 (0.4) | ||

| 18.5‐24.9 | 296 (21.5) | 93 (25.7) | 203(20.0) | ||

| 25‐29.9 | 557 (40.5) | 147 (40.6) | 410 (40.5) | ||

| 30‐34.9 | 301 (21.9) | 71 (19.6) | 230 (22.7) | ||

| 35‐39.9 | 134 (9.8) | 32 (8.8) | 102 (10.1) | ||

| ≥40 | 79 (5.8) | 15 (4.1) | 64 (6.3) | ||

| Preexisting conditions, no. (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 1,461 | 426 (29.2) | 99 (26) | 327 (30.3) | 0.11 |

| Hypertension | 1,461 | 752 (51.5) | 193 (50.7) | 559 (51.8) | 0.71 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1,461 | 423 (29) | 99 (26) | 324 (30) | 0.14 |

| Current smoker | 1,275 | 83 (6.5) | 14 (4.1) | 69 (7.4) | 0.049 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1,461 | 373 (25.5) | 111 (29.1) | 262 (24.3) | 0.06 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1,265 | 133 (10.5) | 35 (10.8) | 98 (10.4) | 0.86 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1,461 | 146 (10) | 45 (11.8) | 101 (9.4) | 0.17 |

| Malignancy | 1,461 | 150 (10.3) | 37 (9.7) | 113 (10.5) | 0.68 |

| Immunosuppression | 1,275 | 88 (6.9) | 19 (5.9) | 69 (7.3) | 0.39 |

| Severity score | |||||

| SAPS‐II | 1,135 | 39 (29‐53) | 29 (22‐39) | 43 (33‐57) | <0.001 |

| Treatments | |||||

| Hypoglycemic treatment | 1,362 | 0.09 b | |||

| No treatment, no. (%) | 990 (72.7) | 282 (76.2) | 708 (71.4) | ||

| Yes, but no insulin, no. (%) | 222 (16.3) | 58 (15.7) | 164 (16.5) | ||

| Insulin, no. (%) | 150 (11) | 30 (8.1) | 120 (12.1) | ||

| Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors | |||||

| ARBs, no. (%) | 1,153 | 192 (16.7) | 59 (18.1) | 133 (16.1) | 0.41 |

| ACEi, no. (%) | 1,153 | 190 (16.5) | 55 (16.9) | 135 (16.3) | 0.82 |

Abbreviations: ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; IQR, interquartile range; SAPS‐II, Simplified Acute Physiology Score II; WHO, World Health Organization.

Mann‐Whitney U test was used for continuous variables comparison, and χ2 test with Yates continuity correction was used for categorical variables comparison if not specified.

Cochran‐Armitage trend test was used for comparison of ordinal BMI categories.

Half of participants had hypertension (51.5%), whereas the prevalence of diabetes and dyslipidemia was 29.2% and 29.0%, respectively. Overall, a total of 1,080 (73.9%) participants required IMV after a median (IQR) time of 0 (0‐1) days following ICU admission. As expected, patients who required IMV had a higher initial severity score than those who did not require IMV. The patients who required IMV were also predominantly male (76.3%), had a higher BMI, and were more frequently current smokers (Table 1). Patient characteristics and data collected in each of the 21 centers are detailed in Supporting Information Figure S3.

At the time of analysis (May 19, 2020), 903 (61.8%) patients had been discharged alive, 385 (26.4%) had died following a median (IQR) 11 (6‐18) days in the ICU, and 173 (11.8%) were still hospitalized in an ICU. The median (IQR) follow‐up period of observation following ICU admission was 13 (7‐26) days in the overall population and 15 (7‐29) days among survivors. Among 1,080 patients who required IMV, 633 (58.6%) patients had been extubated alive at the time of analysis after a median (IQR) duration of IMV of 14 (8‐22) days.

Association between BMI and the need for IMV

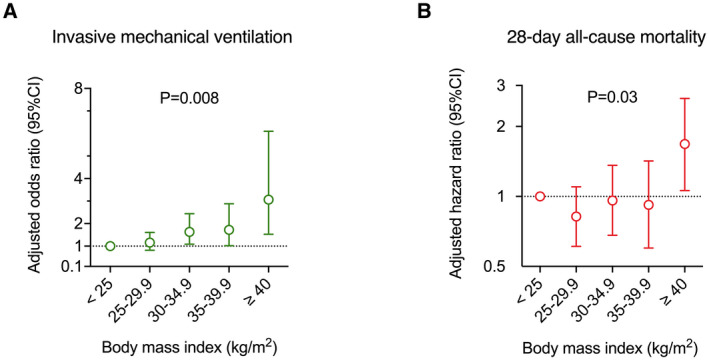

In a multivariable mixed logistic regression model adjusted for center and/or age, sex, and prespecified metabolic risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status), BMI was statistically significantly associated with the need for IMV (Table 2). Moreover, the relationship between BMI and the risk of the need for IMV was linear, as illustrated by the gradual increase of OR with each BMI category, reaching 3.06 (1.53‐6.10) in patients with class III obesity (BMI ≥ 40; Figure 1A). The relationship between BMI and the need for IMV was further confirmed in a sensitivity analysis limited to available cases (Supporting Information Table S1). In addition, we observed that older age and male sex were independent predictors of the need for IMV in contrast to diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status (Table 3 and Supporting Information Table S2).

TABLE 2.

Association of BMI categories with the need for IMV and 28‐day all‐cause mortality

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | p valuea/b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 (n = 319) | 25‐29.9 (n = 591) | 30‐34.9 (n = 323) | 35‐39.9 (n = 143) | ≥40 (n = 85) | ||

| IMV | ||||||

| No. (%) | 219 (68.5) | 436 (73.8) | 248 (76.7) | 109 (76.0) | 69 (81.4) | |

| Center‐adjusted OR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.20 (0.86‐1.66) | 1.46 (0.98‐2.15) | 1.53 (0.93‐2.52) | 2.35 (1.21‐4.52) | 0.07/0.004 |

| Fully adjusted OR (95% CI) c | 1.00 (ref.) | 1.16 (0.82‐1.61) | 1.63 (1.09‐2.44) | 1.72 (1.02‐2.88) | 3.06 (1.53‐6.10) | 0.008/<0.001 |

| Death | ||||||

| No. (%) d | 84 (40.3) | 134 (33.6) | 72 (33.3) | 34 (36.4) | 31 (47.2) | |

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.79 (0.59‐1.06) | 0.75 (0.53‐1.06) | 0.73 (0.48‐1.12) | 1.21 (0.77‐1.87) | 0.10/0.81 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) c | 1.00 (ref.) | 0.82 (0.61‐1.10) | 0.96 (0.68‐1.36) | 0.92 (0.60‐1.42) | 1.68 (1.06‐2.64) | 0.03/0.13 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; OR, odds ratio; ref., reference.

Values were calculated after handling missing values by multiple imputations.

p value for treating BMI categories as a categorical variable in regression model.

p value for treating BMI categories as an ordinal variable in regression model.

Adjusted on center and prespecified covariates (age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and current smoking status).

Kaplan‐Meier estimate at 28 days.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Linear association of BMI categories with the need for invasive mechanical ventilation and (B) nonlinear association of BMI with 28‐day all‐cause mortality. Odds and hazard ratios were calculated using the lean category (BMI < 25 kg/m2) as reference and were adjusted for center and prespecified covariates (age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and current smoking status) after handling missing values by multiple imputations. P values were calculated by treating BMI categories as a categorical variable in the regression model [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

TABLE 3.

Association of continuous BMI with the need for IMV in multivariable analysis including age, sex, and metabolic risk factors

| OR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI, per 5‐kg/m2 increase | 1.27 (1.12‐1.45) | <0.001 |

| Age, per 10‐year increase | 1.17 (1.05‐1.31) | 0.004 |

| Male sex | 1.82 (1.38‐2.41) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.97 (0.72‐1.30) | 0.84 |

| Diabetes | 1.21 (0.89‐1.65) | 0.21 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.08 (0.78‐1.48) | 0.64 |

| Current smoking status | 1.25 (0.66‐2.35) | 0.48 |

OR calculated using multivariable mixed logistic regression model by taking into account center as random effect and after handling missing values by multiple imputations.

Abbreviations: IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; OR, odds ratio.

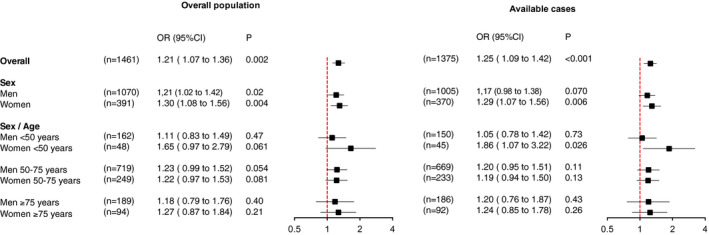

The heterogeneity of the association between BMI and IMV with age was studied in key subgroups exploratory analysis on the overall study population and on the complete‐cases population (Figure 2). As illustrated, the association of BMI with IMV was more pronounced in females under the age of 50 years, with an adjusted OR of 1.65 (95% CI: 0.97‐2.79) in the primary analysis and 1.86 (95% CI: 1.67‐3.22) in the sensitivity analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Association of continuous BMI with the need for invasive mechanical ventilation in the overall study population after handling missing values by multiple imputations and on the complete‐cases population (sensitivity analysis) according to sex and sex/age subgroups. Odds ratios (OR) are expressed per 5‐kg/m2 increase, with 95% confidence intervals (CI) calculated using mixed logistic regression models including center as random effect and adjustments for prespecified, known risk factors (fixed effects) such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and current smoking status [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Association of BMI with 28‐day mortality

The overall estimate of 28‐day mortality was 36.1% (95% CI: 33.0%‐39.5%). As shown in Table 2, we found a nonlinear relationship between BMI categories and 28‐day mortality with an increased mortality risk only for patients with severe or class III obesity (≥40; Figure 1B). The nonlinearity of the relation between BMI and 28‐day mortality was further confirmed in a sensitivity analysis (Supporting Information Table S1).

In a data‐driven model, considering BMI as a binary variable (≥40 vs. <40), obesity class III remained an independent predictor of mortality (HR = 1.84; 95% CI: 1.23‐2.75) in addition to age (HR per 10‐year increase = 1.74; 95% CI: 1.54‐1.95; Table 4). These results were further confirmed in a sensitivity analysis (Supporting Information Table S3).

TABLE 4.

Association of BMI ≥ 40 with 28‐day all‐cause mortality in multivariable analysis including age, sex, and metabolic risk factors

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| BMI ≥ 40 | 1.84 (1.23‐2.75) | 0.003 |

| Age, per 10‐year increase | 1.74 (1.54‐1.95) | <0.001 |

| Male sex | 1.24 (0.96‐1.60) | 0.10 |

| Hypertension | 0.93 (0.72‐1.19) | 0.56 |

| Diabetes | 1.25 (0.98‐1.58) | 0.07 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.00 (0.77‐1.29) | 0.97 |

| Current smoking status | 1.00 (0.59‐1.69) | 0.99 |

HR calculated using frailty model by taking into account center as random effect and after handling missing values by multiple imputations.

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this multicenter cohort study represents the first international collaborative effort to explore the association of BMI with the outcomes of pneumonia among COVID‐19 patients admitted to an ICU. Our main finding was a linear correlation between BMI and the need for IMV after adjustment for center, age, sex, and other prespecified metabolic risk factors. Of note, we observed, in age‐sex subgroups analyses, that the relationship between BMI and the need for IMV was more pronounced in female patients than in male patients under the age of 50 years (Figure 2). An influence of age on the relationship between obesity and COVID‐19 severity has been previously suggested (22, 23, 24), but one that existed regardless of sex. A milder severity of COVID‐19 has been previously reported in premenopausal women (34). In line with our findings, obesity was also the variable most associated with COVID‐19 disease severity in pregnant women in a recent report (35). Of note, estrogen is playing a classically protective role in women (36), and Estradiol levels decreased with overweight and/or obesity in premenopausal women (36, 37). However, the observational nature of our study cannot address the complexity of this question. As expected, we also observed an overall association of the need for IMV with older age and male sex (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19). However, we did not unveil any independent relationship between the need for IMV and current smoking status or with any other prespecified metabolic risk factors. A distinct association of diabetes with the overall severity of COVID‐19 has been suggested in previous reports (4, 16, 38). However, one study did not include BMI among the variables analyzed (38), whereas, in the two others, obesity was the main driver of the association between diabetes and the need for IMV (4, 16).

The second original finding of our study was the nonlinear relationship observed between BMI and the 28‐day all‐cause mortality rate in patients admitted to an ICU. When fully adjusted for center, age, sex and prespecified metabolic risk factors, obesity class III (BMI ≥ 40) was associated with a 68% increase in mortality compared with lean patients (BMI < 25). On the other hand, mortality risk was not increased in patients with overweight or obesity class I and II (BMI between 25 and 39.9). This seemingly paradoxical relationship between mortality and BMI categories has not yet been reported in COVID‐19 patients (5, 6) but echoes the “obesity survival paradox” generally observed in critically ill patients (39), with overweight and moderate obesity being protective compared with lean BMI, normal BMI, or more severe obesity (40). Further research should focus on identifying the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of the “obesity survival paradox” in COVID‐19.

As expected, the all‐cause mortality was also closely linked to age, with a 74% increase per 10 years. Of note, male sex and diabetes were only marginally associated with mortality in the present study, which only enrolled patients admitted to an ICU, in contrast to other multicenter studies conducted in hospitalized patients (6, 38, 41) or in the general population (5).

Strengths

The main strength of the present study was the large number of participants across all BMI categories and the inclusion of both sexes, which allowed us to perform all planned analyses with BMI as the exposure, as well as the association with prespecified metabolic risk factors. Second was the choice of IMV as the study’s primary outcome. As opposed to other, less‐specific end points such as hospital or ICU admission, all‐cause mortality, or composite severity end points (6, 10, 20), IMV allowed us to specifically explore the association between BMI and severity of pneumonia in COVID‐19. Finally, the wide geographic representation of participating centers provides insight related to the generalizability of effect across regions and countries with variable prevalence of obesity, thus improving the validity of our findings and enhancing their general relevance.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study lies in its retrospective nature. Standard clinical care may have varied between centers, and participants received various treatments that were not considered in our analyses. Second, the data from patients who remained hospitalized at the final study date (11.8%) were censored, which may have led to an underestimation of the outcomes. However, this risk appears limited because 98.7% of patients requiring IMV received it within 7 days of admission and because, at the time of analysis, 95.8% of patients had already been discharged alive or had been hospitalized for more than 28 days. Third, the multicenter design of this international study creates a complex confounding structure. Results were not adjusted for other potential confounders, including race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status indicators, and comorbidities such as chronic kidney, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases. Finally, we did not enroll participants from Africa, South America, or Asia, in whom different BMI cut points may have been more relevant. This may limit the generalizability of our findings, which remain to be confirmed more globally.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, the data of this international multicenter cohort study provide direct evidence of the independent association between obesity and the severity of pneumonia in COVID‐19. First, we observed an overall linear relationship of BMI with the need for IMV, which was most pronounced in female patients under the age of 50 years. Second, we observed a nonlinear relationship of BMI with 28‐day all‐cause mortality, which was increased in patients with severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40). With the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic and the obesity epidemic feeding each other (42), this close association between BMI and the severity of COVID‐19 pneumonia should foster more drastic measures to limit the risk of COVID‐19 infections in patients with obesity.

The evidence presented here may also inform physiopathological research to elucidate the relationship between obesity and severe lung damage in COVID‐19.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

FP and MJ had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: MJ and FP; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: MC, VR, JL, AD, MJ, and FP; drafting of the manuscript: MC, VR, MJ, and FP; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: JL and AD; administrative, technical, or material support: NA; and supervision: FP and MJ.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04391738.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Authors thank Mr. Maxime Caillier, Mr. Guillaume Deraedt, and Mr. Amhed Bouzidi for their management of regulatory aspects of the study.

Role of the sponsor: The sponsors were represented by the corresponding authors (François Pattou and Mercè Jourdain). The sponsors had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and review and approval to submit the manuscript for publication. The sponsors did not have the right to veto submission to any particular journal but did participate in the writing group’s discussion when selecting an appropriate journal for submission. The corresponding authors had the final say in submitting the manuscript for publication.

Chetboun M, Raverdy V, Labreuche J, et al. BMI and pneumonia outcomes in critically ill COVID‐19 patients: An international multicenter study. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:1477–1486. 10.1002/oby.23223

Mikael Chetboun and Violeta Raverdy are co‐first authors.

Mercè Jourdain and François Pattou are co‐last authors.

On behalf of the “LICORNE Lille Intensive Care COVID‐19 and Obesity Study Group” (Lille, France); the “COVID‐19 Toulouse Intensive Care Unit Network” (Toulouse, France); the “Hasharon Hospital‐Rabin Medical Center Covid‐19 and Obesity Study Group” (Petach‐Tikva, Israel); the “ID and ICU Covid‐19 Study Group” (Providence, Rhode Island); the “Rouen Covid‐19 and Obesity Study” (Rouen, France); the “COVID‐O‐HCL Consortium” (Lyon, France); the “MICU Lapeyronie” (Montpellier, France); the “Bronx COVID‐19 and Obesity Study Group” (Bronx, New York); the “MIR Amiens Covid19” (Amiens, France); the “Strasbourg NHC” (Strasbourg, France); and the “Foch COVID‐19 Study Group” Suresnes, France.

A complete list of co‐authors can be found in online Supporting Information.

Contributor Information

Mercè Jourdain, Email: mercedes.jourdain@univ-lille.fr, Email: mercedes.jourdain@univ-lille.fr.

François Pattou, Email: francois.pattou@univ-lille.fr.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 2. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054‐1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574‐1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052‐2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID‐19‐related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430‐436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid‐19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Caussy C, Pattou F, Wallet F, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in France. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:562‐564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gao M, Piernas C, Astbury NM, et al. Associations between body‐mass index and COVID‐19 severity in 6·9 million people in England: a prospective, community‐based, cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(6):350‐359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cariou B, Hadjadj S, Wargny M, et al. Phenotypic characteristics and prognosis of inpatients with COVID‐19 and diabetes: the CORONADO study. Diabetologia. 2020;63:1500‐1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deng S‐Q, Peng H‐J. Characteristics of and public health responses to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. J Clin Med. 2020;9:575. doi:10.3390/jcm9020575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhao Q, Meng M, Kumar R, et al. The impact of COPD and smoking history on the severity of COVID‐19: a systemic review and meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2020:92;1915‐1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1973‐1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simonnet A, Chetboun M, Poissy J, et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2020;28:1195‐1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid‐19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2372‐2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bello‐Chavolla OY, Bahena‐López JP, Antonio‐Villa NE, et al. Predicting mortality due to SARS‐CoV‐2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID‐19 outcomes in Mexico. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgaa346. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalligeros M, Shehadeh F, Mylona EK, et al. Association of obesity with disease severity among patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1200‐1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W, et al. Severe obesity, increasing age and male sex are independently associated with worse in‐hospital outcomes, and higher in‐hospital mortality, in a cohort of patients with COVID‐19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020;108:154262. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Busetto L, Bettini S, Fabris R, et al. Obesity and COVID‐19: an Italian snapshot. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1600‐1605. doi: 10.1002/oby.22918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cai Q, Chen F, Wang T, et al. Obesity and COVID‐19 severity in a designated hospital in Shenzhen, China. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(7):1392‐1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chao JY, Derespina KR, Herold BC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized and critically Ill children and adolescents with coronavirus disease 2019 at a tertiary care medical center in New York City. J Pediatr. 2020;223:14‐19.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buscemi S, Buscemi C, Batsis JA. There is a relationship between obesity and coronavirus disease 2019 but more information is needed. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1371‐1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kass DA, Duggal P, Cingolani O. Obesity could shift severe COVID‐19 disease to younger ages. Lancet. 2020;395:1544‐1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S, et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid‐19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:896‐897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ong SWX, Young BE, Leo Y‐S, Lye DC. Association of higher body mass index with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in younger patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2300‐2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Overweight and obesity. https://www.CDC.gov/obesity/index.html. Updated March 23, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 27. Ministry of Solidarity and Health . Obesity and Covid‐19. https://solidarites‐sante.gouv.fr/soins‐et‐maladies/prises‐en‐charge‐specialisees/obesite/article/obesite‐et‐covid‐19. Updated August 10, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 28. GOV. UK . COVID‐19: infection prevention and control (IPC). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan‐novel‐coronavirus‐infection‐prevention‐and‐control. Published January 10, 2020. Updated August 10, 2021. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 29. World Obesity . Obesity and COVID‐19: Policy statement. https://www.worldobesity.org/news/obesity‐and‐covid‐19‐policy‐statement. Accessed June 4, 2021.

- 30. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology . COVID‐19: underlying metabolic health in the spotlight. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:457. [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organization . Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID‐19 is suspected Interim guidance. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665‐332299. Published January 12, 2020.

- 32. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization . Overweight and obesity. Updated June 9, 2021. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/obesity‐and‐overweight

- 34. Ding T, Zhang J, Wang T, et al. Potential influence of menstrual status and sex hormones on female SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a cross‐sectional study from multicentre in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:e240‐e248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kayem G, Lecarpentier E, Deruelle P, et al. A snapshot of the Covid‐19 pandemic among pregnant women in France. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;49(7):101826. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Gracia CR. Obesity and reproductive hormone levels in the transition to menopause. Menopause. 2010;17:718‐726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Y, Jerkic M, Slutsky AS, Zhang H. Molecular mechanisms of sex bias differences in COVID‐19 mortality. Crit Care. 2020;24:405. doi:10.1186/s13054-020-03118-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu L, She Z‐G, Cheng XU, et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID‐19 and pre‐existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020;31:1068‐1077 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schetz M, De Jong A, Deane AM, et al. Obesity in the critically ill: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:757‐769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Acharya P, Upadhyay L, Qavi A, et al. The paradox prevails: outcomes are better in critically ill obese patients regardless of the comorbidity burden. J Crit Care. 2019;53:25‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rottoli M, Bernante P, Belvedere A, et al. How important is obesity as a risk factor for respiratory failure, intensive care admission and death in hospitalised COVID‐19 patients? Results from a single Italian centre. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;183:389‐397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dicker D, Bettini S, Farpour‐Lambert N, et al. Obesity and COVID‐19: the two sides of the coin. Obes Facts. 2020;13(4):430‐438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material