Abstract

COVID‐19 has challenged people worldwide to comply with strict lock‐downs and meticulous healthcare instructions. Can states harness enclave communities to comply with the law in such crucial times, even when compliance conflicts with communal sources of authority? We investigated this question through the case of Israeli ultra‐Orthodox schools compliance with COVID‐19 regulations. Drawing on semi‐structured interviews with school principals, documents and media sources, and a field survey, we found that the state has the capacity to quickly internalize new norms and harness the cooperation of previously suspicious communities. At the same time, we found that communal authorities were able to shield widespread communal defiance from legal enforcement. These findings expose the bidirectionality of legal socialization: As the community uses its defiance power to attenuate the law, it socializes public authorities to accede to their bounded authority. As public authorities come to realize that the community cannot be brought to full compliance, they curtail enforcement efforts and socialize the community to operate outside the law. Our findings animate the reciprocity assumption in legal socialization theory and highlight one of the crucial tasks for the next 50 years of research: to examine the bidirectionality of legal socialization and discover its socio‐legal effects.

Keywords: bounded authority, COVID‐19, enclave communities, enforcement, law and policy, law and religion, legal socialization, reciprocity, ultra‐orthodox community

COVID‐19 has challenged people worldwide to comply with strict lock‐downs and rigorous healthcare instructions. However, enduring national emergencies is a collective effort. How do enclave communities respond to the law in such crucial times, particularly when compliance conflicts with communal authorities? How does this response socialize, in turn, both the community and the state? We explore these questions in the context of the ultra‐Orthodox Jewish community in Israel, an enclave religious community (hereinafter: EC) with a distinct ideological and organizational culture (Almond et al., 2003). When the COVID‐19 pandemic broke, Israeli ultra‐Orthodox schools were instructed to close along with all schools nationwide. We examine the decision making of ultra‐Orthodox principals, focusing on the interaction between legal and nonlegal norms in their decisions and how bidirectional legal socialization influenced their perceptions and behavior.

Our findings indicate that school principals’ decisions to comply or defy the regulations that mandated school closure (hereinafter: the regulations) were intertwined with their perceptions of the law. Compliant ultra‐Orthodox principals perceived the regulations as unequivocal, trustworthy, professional, and unbounded by communal authority. In contrast, defiant ultra‐Orthodox principals perceived the regulations as ambiguous and untrustworthy and viewed legal authority as bounded by communal authority and religious norms. The findings also show that the defiant principals’ behavior was intertwined with the behavior of public authorities, who operated under the notion that the ultra‐Orthodox community could not be brought to compliance and hence, lowered their expectations and curtailed their enforcement efforts. These low expectations were a consequence of communal political efforts to attenuate the law, constrain the public authorities’ conduct, and impose alternative norms. The result of this feedback loop is what we term bidirectional legal socialization, as legal power is shaped by community pressure and, in turn, shapes community responses to the law. Thus, the community uses its clout to socialize the state and attenuate the power of law, and the state socializes the community by refraining from enforcing the law. Our findings further expose the malleability of legal socialization, as many ultra‐Orthodox school principals complied with the regulations and trusted the law, despite a history of suspicion of state authorities and weak law enforcement (Perry‐Hazan, 2015a, 2015b). These widespread expressions of compliance reveal the prospect of reconstructing the relationships between law and communities based on fresh teachable experiences.

Our study intersects three theories regarding legal decision making and legal socialization: reciprocity, which concerns the assumption that whereas the law affects citizens, citizens also affect the law; bounded authority, which concerns societal notions regarding the domains where legal authorities should not intervene; and legal socialization beyond the legal world, which addresses the role of nonlegal factors in shaping citizens’ legal attitudes and behavior.

In addition to showing how these theories interrelate and complement each other in the context of our research questions, we make specific contributions to each of them. First, although early studies underscored the need to understand the role of reciprocity in legal socialization (Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974), the phenomenon and its mechanisms have yet to be explored. Our analysis of the bidirectional processes of legal socialization emerged from the concept of reciprocity and expands its meaning. Second, we contribute to the literature on bounded authority by shifting the focus from the impact of increased intrusion by legal authorities (Murphy, 2021; Tyler et al., 2014) to the impact of decreased intrusion, particularly via legal exemptions and refraining from enforcement. Third, our research contributes to the understudied subfield of legal socialization that explores the interaction between social environment and legal socialization (Trinkner & Cohn, 2014). Several studies on legal socialization beyond the legal world have explored the role of communities and neighborhoods in legal socialization (Antrobus et al., 2015; Piccirillo et al., 2021; Sampson & Bartusch, 1998; Tyler & Fagan, 2008). However, none of these studies examined religious communities and the impact of religious norms and leadership on binding state authority. Moreover, our analysis is grounded in qualitative socio‐legal methods (see also Kupchik et al., 2020) and thus, contributes new perspectives to legal socialization scholarship, heretofore dominated by perspectives rooted in cognitive development and social psychology (Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). Finally, our findings have implications for legal authorities interacting with ECs.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows. After reviewing the relevant literatures, we provide a contextual background about the ultra‐Orthodox educational system in Israel. We then present the research design, which is based on interviews with ultra‐Orthodox school principals, as well as on document analysis and a field survey that triangulated the data. We conclude by discussing our theory of bidirectional legal socialization, our contributions to research, the study's limitations, and recommended directions for future research.

LEGAL SOCIALIZATION, BOUNDED AUTHORITY, AND RECIPROCITY

Legal socialization refers to the process by which individuals develop values, attitudes, and beliefs about laws, the institutions that create law, and the people who enforce the law (Fine & Trinkner, 2021). The study of legal socialization is concerned with understanding how this process transpires and how variations in socialization lead to variations in orientations toward the law (Trinkner & Tyler, 2016) and affect legal behavior, particularly compliance with the law (Cohn & White, 1986; Reisig et al., 2011, 2014; Tankebe et al., 2016). When people develop a stable relationship with the law based on mutual respect and shared values, they are more likely to support the legal system, comply with laws, and cooperate with legal authority (Trinkner & Tyler, 2016).

The legal socialization literature focuses on two primary orientations: legitimacy of the law and cynicism toward the law (e.g., Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Kaiser & Reisig, 2019; Reisig et al., 2011, 2014; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014). Legitimacy of the law refers to the judgment that laws and legal authorities are acknowledged as appropriate, proper, and just (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Tyler, 2006). Legal cynicism is embedded in the rejection of law and its binding power (Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014). Whereas legitimacy of the law is associated with voluntary and intrinsically motivated compliance (Tyler & Fagan, 2008), legal cynicism is related to noncompliance, compelling the state to be reliant upon deterrence and sanctions.

The legal socialization process is influenced by individual factors, such as cognitive and developmental aspects, along with aspects relating to the social environment, such as interactions with the authorities (Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Tapp, 1991). One of the prominent factors cited as influencing legal socialization is the legal authorities’ behavior, particularly whether the authorities’ conduct is procedurally just (e.g., Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014; Tyler & Fagan, 2008; Tyler et al., 2014). Procedural justice refers to the quality of both the decision making and the interpersonal treatment of legal agents (Tyler & Fagan, 2008). Tyler et al. (2014) termed encounters with legal agents, such as the police, as “teachable moments” (p. 754) that shape public views about the legitimacy of legal authority.

Another significant factor influencing legal socialization processes is the perceived boundaries of legal authority, namely, whether and to what extent citizens perceive legal authorities as acting within the confines of their rightful powers (Huq et al., 2017; Murphy, 2021; Tyler & Trinkner, 2018). While procedural justice is a function of how legal power is exercised, bounded authority is about when, where, and what power is exercised (Trinkner et al., 2018). These extralegal limits of state authority are contextual. They are not related to the legality of state power but to individuals’ expectations about what domains should be exempt from the law (Huq et al., 2017; Trinkner et al., 2018). The impact of bounded authority perceptions on legal socialization––analyzed in the current study––has received considerably less attention in the literature than procedural justice. Several studies examined cases of increased intrusion by legal authorities in the context of street stops (Tyler et al., 2014) and police presence in Muslim neighborhoods (Murphy, 2021). No study to date has used legal socialization frameworks to examine decreased intrusion by legal authorities, such as underenforcement and granting legal exemptions.

Bounded authority concerns are embedded in the reciprocal relationship between the law and the public. When police wield their power in ways congruent with citizens’ expectations, citizens are likely to feel obligated to comply with the law (Huq et al., 2017; Trinkner et al., 2018). The reciprocity assumption implies that individuals carry strong beliefs about the duties and purposes of the law regarding the community as well as the responsibilities and obligations of the community toward the law (Tapp & Levine, 1974; Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). In another sense, reciprocity implies that whereas the law affects citizens, citizens also affect the law (Fine & Trinkner, 2021). The latter understanding of reciprocity entails that law is not static but is continually modified as a consequence of citizen pressure (Fine & Trinkner, 2021) or participatory mechanisms of decision making (Tapp & Levine, 1974). Treating legal activity as a reciprocating process implies that individuals are continually trying to make sense of their socio‐legal environment and push for change (Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Tapp & Levine, 1974). Bottoms and Tankebe (2012) offered proximate conceptual arguments, emphasizing the dual and relational character of legitimacy in criminal justice, which involves both responses by the audience (i.e., citizens) and claims for legitimacy by power holders. Within this dialogic framework, they noted that the legitimacy of the law is in constant flux, as the power holders might adjust the nature of the claim in light of the audience's response. Early studies emphasized the importance of understanding reciprocity in legal socialization (Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974), but there is a gap in the legal socialization literature regarding the impact of reciprocity and how it operates in action. Religious ECs comprise one such context, as these communities are wont to push for obtaining legal exemptions. In the current study, we expand the concept of reciprocity beyond the positive sense that Tapp and others envisioned: rather than collaborating with authorities on a joint enterprise to advance the law, citizens may collaborate with authorities to erode the law.

LEGAL SOCIALIZATION BEYOND THE LEGAL WORLD

Most studies of legal socialization have focused on individuals’ interactions with legal authorities, particularly with the police (e.g., Geller et al., 2021; Granot et al., 2021; Kupchik et al., 2020; Tyler et al., 2014). Beyond the simple application of rules, the actions of legal authorities communicate broader social information to subordinates (Justice & Meares, 2014; Tapp & Levine, 1974). However, the legal socialization process is pervasive, extending far beyond the legal domain (Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974; Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). In daily life, rule‐creating and administrative processes transpire in various contexts (Tapp & Levine, 1974). Legal socialization, therefore, encompasses diverse processes through which people experience relationships with authority in their families, schools, and communities (Cohn et al., 2012; Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974; Thomas et al., 2021; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014; Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). Ultimately, individuals acquire their notions of law and compliance and develop strategies for utilizing the law through an interaction between legal and nonlegal environments (Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014; Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). Examining legal socialization as a trajectory that occurs in both legal and nonlegal domains lies at the core of our study.

Some of the studies addressing nonlegal environments focused on youth participants and showed that parents and teachers have a profound impact on legal socialization (e.g., Cavanagh & Cauffman, 2015; Cohn et al., 2012; Pennington, 2017; Thomas et al., 2021; Trinkner & Cohn, 2014; Trinkner et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2017). Social influences on legal socialization were also identified by Cardwell et al. (2021), who demonstrated a peer effect in youth's perceptions of school authority. Although social influence is particularly strong during adolescence, it continues to impact the legal socialization of adults (Forrest, 2021; Tapp, 1976).

Individuals’ attitudes and behaviors are also shaped by the contexts in which they live. Tyler and Fagan (2008) showed that residents in poor neighborhoods characterized by high concentrations of racial and ethnic minorities experience different forms and strategies of policing that may shape their views of the police. Similarly, Sampson and Bartusch (1998) found that structural characteristics of neighborhoods explain variations in normative orientations toward law, criminal justice, and deviance. Their findings revealed that inner‐city disadvantaged neighborhoods display elevated levels of legal cynicism, dissatisfaction with police, and tolerance of deviance beyond what can be attributed to sociodemographic composition and crime‐rate differences. Antrobus et al. (2015) found that perceived community norms about obeying the police were strongly associated with individuals’ personal commitment to obey police; moreover, individuals placed greater emphasis on procedural justice when they felt others in their community viewed police as less legitimate. Piccirillo et al.’s (2021) study on police contact with Brazilian teenagers indicated that the role of neighborhood ecology in legal socialization was dependent on multiple and sometimes conflictual factors relating to the level of violence and fear of victimization. Studies also showed that race influences individuals’ perceptions of the law (e.g., Fine et al., 2019; Hagan et al., 2005). According to the group‐position hypothesis, minority groups’ negative views of law enforcement may derive from their view that they hold an unfavorable group position in society (see Blumer, 1958; Fine et al., 2019; Lockwood et al., 2018).

These findings highlight that legal socialization is intertwined with structural conditions that shape communities’ relations with the state, such as inequalities, social inclusion, and feelings of belonging to the state (see Bradford & Jackson, 2018; Murphy et al., 2019; Wolfe & McLean, 2021). These insights align with the assumption of reciprocal relationships between the law and the public (Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Tapp, 1991; Tapp & Levine, 1974). Trinkner and Cohn (2014) suggested that future research should delineate how the diverse areas of the social environment impact legal socialization and develop a more comprehensive and sophisticated understanding of legal socialization. Our study of communities’ socializing power offers such an analysis. We contribute to the study of legal socialization beyond the confines of the legal world by focusing on the context of religious ECs and exploring the understudied theoretical framework of reciprocal relationships between communities and the law.

Religion is the prime example of a system of norms that may contend with the law over the ultimate authority and influence individuals’ perceptions of law's boundaries. Schools comprise one of the foremost arenas in which conflicts between law and religion are played out (Barak‐Corren, 2017; Callan, 1997; Guttmann, 1999; Mautner, 2011; Tebbe, 2007). Today, little is known about the effects of law on religious ECs (see Barak‐Corren, 2017; Perry‐Hazan, 2014, 2015b, 2019; Stolzenberg, 2015; Weisbrod, 1980). Understanding the encounter between legal and religious norms on the ground can help elucidate the mutual socializing role of legal and nonlegal contexts.

CONTEXTUAL BACKGROUND

The site of our study is the Jewish ultra‐Orthodox community in Israel, an enclave culture that enshrines its insularity and autonomy and shares a guarded approach toward the state (Leon, 2016). The community includes numerous subgroups, each with its dominant spiritual leader (Leon, 2016; Shoshana, 2014; Zicherman & Cahaner, 2012). Around 12.5% of the Israeli population define themselves as ultra‐Orthodox Jews, and 18.5% of schoolgoers attend ultra‐Orthodox schools, comprising 24.5% of Jewish students in Israel (Malach & Cahaner, 2019).

The ultra‐Orthodox community aspires to the ideal of a scholars’ society, viewing the full‐time study of sacred texts as the ultimate commitment of ultra‐Orthodox men (Hakak & Rapoport, 2012; Perry‐Hazan, 2015b). Consequently, the ultra‐Orthodox boys’ curriculum focuses primarily on religious texts, a factor that has generated continuing litigation concerning these schools’ noncompliance with the state‐mandated core curriculum (Perry‐Hazan, 2015a, 2015b). Several decades ago, the ultra‐Orthodox parties became a balance pivot in Israeli politics, and almost every coalition needed to enlist ultra‐Orthodox support (Lehmann, 2012). As ultra‐Orthodox politicians placed education at the forefront of their activity, ultra‐Orthodox schools became a “third rail,” an untouchable issue for out‐group politicians (Katzir & Perry‐Hazan, 2019; Perry‐Hazan, 2015a).

Over the years, the enclave status of ultra‐Orthodox schools has been entrenched through several official and non‐official legal exemptions. In primary education, Israel's Ministry of Education has refrained from enforcing the obligation to teach a state‐mandated core curriculum in ultra‐Orthodox schools and has not systematically supervised their curricula and teacher education (Perry‐Hazan, 2015b; State Comptroller, 2020). In secondary education, after the Supreme Court required the state to determine a core curriculum for ultra‐Orthodox high schools (Jewish Pluralism Center v. The Ministry of Education, 2008), the state officially exempted these schools from having to teach secular education (Unique Cultural Educational Institutions Act, 2008). Additionally, ultra‐Orthodox young men enrolled in religious institutions are exempted from service in the Israeli army, an exemption that is under continual public, political, and legal controversy (Leon, 2017). Thus, the COVID‐19 crisis erupted against a fraught relationship between Israeli authorities and the ultra‐Orthodox community, particularly regarding ultra‐Orthodox education issues.

CURRENT RESEARCH OBJECTIVE AND QUESTIONS

On March 12, 2020, in the wake of the coronavirus crisis's first wave, the Israeli government ordered the closure of all schools nationwide, to begin the following day (Order of National Health [The New Coronavirus––Restricting Activities of Educational Institutions], 2020; see also Nachshoni, 2020; Rosen, 2020; Rosner, 2020a). In response, a prominent ultra‐Orthodox leader (Rabbi H. Kanievsky) directed ultra‐Orthodox boys’ schools to continue teaching, declaring that religious study is the indispensable foundation of the universe that protects against all harm (Adamker, 2020a; Katz, 2020a; Lavie, 2020c; Sherki, 2020). Some schools complied with the government regulations and closed their gates (Cohen, 2020a; Rabina, 2020a; Rotman, 2020; Sheffer, 2020), whereas others remained open for another week to 10 days (Frey, 2020; Katz, 2020c; Rabina, 2020c; Rabinovich, 2020e). During this brief interval, COVID‐19 spread widely in the ultra‐Orthodox community, and the community locales became the primary hotspots for the virus in the country (Rosner, 2020d, 2020h; Yod, 2020). By 26 March, all ultra‐Orthodox schools had closed, if not for fear of the virus, then for the prescheduled Passover holiday break.

The current study explored how the ultra‐Orthodox community responded to the law in the wake of the March 2020 school closure regulations, given that compliance to the state‐mandated regulations was in conflict with the communal authorities’ directives. Furthermore, we inquired how this response socialized both the community and the state. To resolve these questions, we explored the intersection between the legal socialization, perceptions of law, and legal behavior of ultra‐Orthodox school principals. Specifically, we posed the following questions: (1) How did legal and nonlegal norms interact in the decision‐making process of school principals? (2) How did the principals perceive the law and its legitimacy? (3) Whether and how were legal perceptions intertwined with legal behavior (defiance or compliance)? (4) Whether and how did interactions with state authorities influence school principals’ legal socialization?

METHOD

Our examination combined several methods: First, we conducted semi‐structured interviews with 18 principals of ultra‐Orthodox boys’ schools, exploring their compliance with the regulations and the factors that shaped their decisions. Appendix 1 presents the interview guidelines. We recruited school principals who had participated in an ongoing study we are conducting (N = 8), as well as school principals who answered the phone for the field survey we conducted (see below) and agreed to be interviewed (N = 10 of 13 who answered the phone), yielding a cooperation rate of 86%. In most cases, the school secretary answered the phone and provided details for the survey (more on the survey below). Notably, we were able to field the study quickly as an outgrowth of our ongoing project that examines conflicts between legal and religious norms in ultra‐Orthodox schools. Having already established field contacts and the research infrastructure, including a research team that comprised ultra‐Orthodox research assistants and IRB approvals, we had the rare opportunity to examine the principals’ decision making during the crisis. Both of us have considerable experience conducting empirical research within ultra‐Orthodox communities.

We used a heterogeneous purposive sampling (Ritchie et al., 2013, pp. 113−114). This sampling ensured a diversity of ultra‐Orthodox affiliations, school networks, and municipalities. Table 1 summarizes our sample's characteristics. Quotations ascribed to interviewed principals are identified by the letter P and a serial number ranging from 1 to 18.

TABLE 1.

List of interviewed principals (N = 18)

| Age | School location by city | Religiosity of the locality | School network | School's UO affiliation | School's legal status | Venue of interview | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 57 | Tiberias | Mixed | Private association | Sephardic | Recognized unofficial | Principal's office |

| P2 | 55 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Public | National Haredi | National | Phone |

| P3 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Private association | Sephardic | Exempt | Phone | |

| P4 | 38 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Private association | Sephardic | Recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P5 | 48 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Private association | Lithuanian | Exempt | Phone |

| P6 | 47 | Tiberias | Mixed | Wellspring of Torah Education | Sephardic | Recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P7 | 37 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Private association | Overall Haredi | Recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P8 | NA | Jerusalem | Mixed | NA | NA | Exempt | Phone |

| P9 | 48 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Wellspring of Torah Education | Sephardic | Recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P10 | 41 | Jerusalem | Mixed | Private association | Hassidic | Exempt | Phone |

| P11 | 37 | Tiberias | Mixed | Private, other | Lithuanian | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P12 | 51 | Migdal Haemek | Mixed | Wellspring of Torah Education | Sephardic | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P13 | 55 | Bnei Brak | Ultra‐Orthodox | Private association | Lithuanian | Exempt | Phone |

| P14 | 47 | Modi'in Illit | Ultra‐Orthodox | Private association | Lithuanian | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P15 | 48 | Modi'in Illit | Ultra‐Orthodox | Private association | Lithuanian | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P16 | 39 | Netanya | Mixed | Wellspring of Torah Education | Sephardic | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P17 | 49 | Mateh Binyamin | Ultra‐Orthodox | Private association | Sephardic | recognized unofficial | Phone |

| P18 | NA | Netanya | Mixed |

Independent Education |

Hassidic | Recognized unofficial | Phone |

Note: The vast majority of ultra‐Orthodox schools (98%) are private, having the legal status of either recognized unofficial or exempt. The two largest networks of ultra‐Orthodox recognized unofficial schools are the Independent Education and the Wellspring of Torah Education. The remaining recognized unofficial schools and the exempt schools belong to various private associations.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

All interviews were conducted between March 23 and April 2 in the principals’ office or via telephone (due to the pandemic, most were phone interviews). Interviews lasted around 30 min on average, and they were recorded and transcribed. The procedures followed ethical guidelines, including guidelines relating to informed consent and confidentially. To maintain the interviewees’ anonymity, we have removed all identifiable details from this paper.

The interviews were analyzed in several steps. During the first phase of analysis, we outlined factual patterns and general themes that emerged from the interviews. To increase the coding's credibility, this process was conducted by each of the two authors separately (Olson et al., 2016). Then, we discussed and compared the ideas and jointly formulated the initial coding scheme, aiming to capture all sources of variation in the principals’ decision‐making processes. These included explicit and implicit positions toward compliance with the regulations, trust in the law, encounters with law enforcement, fear of law enforcement, attitudes toward health professionals, and explicit and implicit positions toward rabbinic directives.1 In the second phase, we analyzed the interviews, based on the coding scheme, in two complementary phases (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015): (1) a vertical analysis, where data regarding each principal were analyzed separately to capture within‐principal nuances, expose tensions and dissonances, and construct a detailed as well as a holistic account of each principal's attitudes and behaviors; and (2) a horizontal analysis, which compared common themes and contrasting patterns across principals, using Dedoose. During a further round of analysis, we refined our categories for added precision. During all rounds, disagreements were resolved by discussion to reach a consensus.

To supplement the analysis of the interviews, we collected and analyzed publicly accessible data from several sources (Table 2 summarizes the sources; N materials = 498): First, between March 12, 2020 and April 5, 2020,2 we collected every issue of all three ultra‐Orthodox daily newspapers, one periodical, and every item published in the two largest ultra‐Orthodox news websites. Together, these sources provide a comprehensive representation of the outlets of all major ultra‐Orthodox sects and worldviews at the time of the study. Second, we collected all relevant tweets published by the ultra‐Orthodox general media correspondents within these dates. Third, we searched for relevant coverage in the general media using the search words “corona” and “ultra‐Orthodox.” We cite these materials as media and social media sources and provide direct links to them wherever possible. Finally, we received visual evidence from informants in ultra‐Orthodox neighborhoods. We coded the number and content of all mentions of schools’ legal behavior, legal norms, law enforcement, healthcare guidelines, rabbinic guidelines, communal norms, and pandemic outcomes in ultra‐Orthodox communities in Israel and the world. The materials provided rich insight into how the progression of the crisis, the decisions of state authorities, and the directives of rabbis were conveyed, understood, and evolved, day‐by‐day, in real time.

TABLE 2.

Summary of materials

| No. items in UO newspapers (March 12–April 5, 2000) | General media items about UO schools | Formal documents | Visual evidence | Street posters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (Hassidic) | YN (Lithuanian) | HM (Hassidic) | KH (Sephardic) | HH (Lithuanian) | ZI (Modern) | |||||

| 173 | 134 | 94 | 47 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 19 | 4 | 5 |

| Total number of materials = 498. | ||||||||||

Note: S (Shaharit), YN (Yated Neeman), HM (HaMevaser) are daily ultra‐Orthodox newspapers; KH (Kikar Hashabat) and HH (Hadrei Haredim) are major ultra‐Orthodox news websites; ZI (Zarich Iyun) is an ultra‐Orthodox periodical; General media items were collected by searching for all mentions of “corona” and “ultra‐Orthodox” in the same date range; Twitter messages were gathered from accounts of ultra‐Orthodox general media correspondents; visual evidence of institutions and street posters were gathered by ultra‐Orthodox informants.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

We then cross‐checked this information with the interview data and the field survey (see below) to triangulate the analysis, confirm factual statements, and contextualize the interviews against the rapidly fluctuating information and social background at the time of the study. For example, the daily ultra‐Orthodox coverage on the progression of the pandemic and rabbinic directives facilitated our understanding of the information that was available to our interviewees at the time of the interviews. In addition, the materials included detailed reports concerning the legal behavior of numerous schools across the country and their interactions with the police, which supplemented our findings on school behavior and were cross‐checked against them.

Finally, we conducted a field survey of ultra‐Orthodox schools in all large ultra‐Orthodox concentrations in Israel (N = 628). The schools’ contact information (names, addresses, and phone numbers) was obtained from the Ministry of Education's website, where it is publicly available. A team of trained research assistants called each school office on two different dates to inquire whether the school was open or closed and since when. In a few cases, the principal himself answered the phone, and in most of those cases, we proceeded to conduct a full interview with him (see above); in other cases, we collected information from the school office. Most employees who answered the call readily provided information on the school's opening status, but some were quick to hang up.

The field survey's original objective was to supplement the interview data with real‐time evidence on the schools’ closure status and to obtain a deeper understanding of how widespread were the behaviors and decision processes that were revealed in the interviews. However, the rapid pace of developments during the crisis prevented us from fully achieving this objective, as schools were closing while we were conducting the survey. Furthermore, in the course of the interviews, we discovered that many defiant schools closed before we had begun the survey, information that was unavailable in real time. Overall, we obtained responses from 101 of the contacted schools (16%). Whereas this response rate is comparable to response rates characterizing public opinion surveys in the United States (Schoeni et al., 2013) and previous surveys of ultra‐Orthodox in Israel (Enos & Gidron, 2016), we cannot determine that the responding schools were representative of the general population of ultra‐Orthodox schools. Thus, as explained below, we cross‐checked the survey findings against reports of school behavior gathered from the media and the interviews.

RESULTS

Our findings tell a story of legal socialization in two parts. In the first part, we map the variation in the perspectives of the law—how the law was perceived, applied, and delineated––by ultra‐Orthodox school principals. In the second part, we focus on the interplay between the community and the state, revealing the bidirectionality of legal socialization. The two parts are complementary, but they are not symmetric: Whereas the introduction of a new law socializes all decision‐makers, only objectors act to attenuate the law.

Mapping the variance in legal behavior and legal perceptions

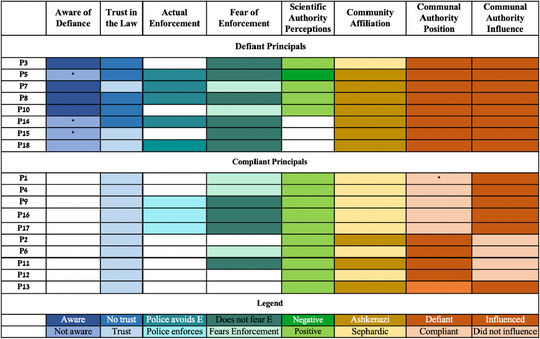

In this section, we describe how different ultra‐Orthodox school principals responded to the new law conferred upon them and how they perceived the interrelations of legal authority, scientific authority, and communal authorities. We find that legal perceptions are intertwined with legal behavior. Compliant and defiant principals perceived the regulations’ clarity, legitimacy, and rational basis very differently and were subject to different communal authorities. All defiant schools followed the defiant Rabbi Kanievsky, whereas most compliant schools followed compliant rabbis3 (however, some schools decided to close despite contrary rabbinical authority). Our analysis distinguishes between principals who complied with the regulations and those who initially defied them. Figure 1 graphically depicts the differences between these two groups.

FIG 1.

Charting the variance in legal perceptions among compliant and defiant ultra‐orthodox principals. Note: The findings presented in this table are based on interviews with 18 ultra‐Orthodox school principals during the early weeks of the COVID‐19 crisis, when schools were ordered to shut down to prevent the pandemic from spreading. Asterisks signify that the interview's classification was not clear cut. E signifies enforcement. * denotes mixed or ambivalent perceptions. The orange cell in the "Communal Authority Position" column is explained in FN 6.

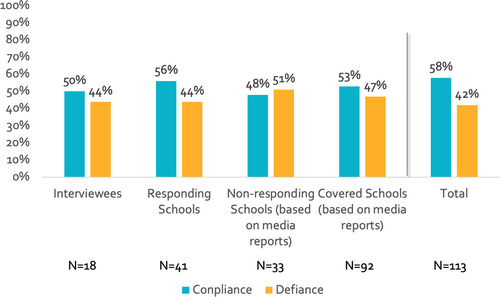

In our interview sample, 44% of the principals defied the regulations and 50% complied.4 How common were defiance and compliance overall? We addressed this question by triangulating findings from the survey, the interviews, and the additional materials. First, the defiance and compliance rates among the interviewed schools were comparable to those of schools in the field survey (44% vs. 56%, respectively).5 Nonetheless, we were cognizant of the possibility that the survey findings under‐represented defiant schools due to response bias, given the limitations noted above. Therefore, we cross‐checked them against the dozens of reports concerning the opening status of ultra‐Orthodox schools in the materials. This inquiry yielded data on the actions of a subset of schools that did not respond to the survey but were covered by the media (N = 33). These data corroborated the survey results, revealing comparable patterns (51% defiance vs. 48% compliance). We then analyzed the entire sample of media reports, as it offered an independent dataset of schools’ behavior, including schools that were not included in the field survey (N = 92). We again found similar rates of defiance and compliance (47% vs. 53%, respectively). Pooling data from all sources (interviews, survey, media), minus overlaps, yielded converging results (42% defiance vs. 58% compliance; N = 113). Overall, it appears that the ultra‐Orthodox schools were roughly split between compliance and defiance. We now turn to examine the underpinnings of this split (see Figure 2).

FIG 2.

Estimating compliance and defiance among Ultra‐Orthodox schools. Note: The figure plots the pattern of compliance and defiance among ultra‐Orthodox schools during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic, by different methods of inquiry and resulting samples (from left to right): (a) qualitative interviews; (b) phone survey (including only schools that provided pertinent information on their legal behavior); (c) a cross‐examination of the phone survey data against media reports that yielded evidence on a subset of schools that did not respond to the phone survey; (d) the broad sample of all media reports on school behavior. The final column pools data from all samples, excluding overlaps.

Compliant school principals

Perceptions of the law: clear, trustworthy, and should be obeyed, regardless of enforcement

Compliant principals closed their schools immediately following the government's decision to close schools nationwide (Cohen, 2020a; Sheffer, 2020). In the interviews, they described the law and their duties to close their institutions as clear‐cut, noting that their decision to comply was straightforward:

P6: We had nothing to consider. Simply, the instructions were given, and we complied with them, as is. They asked us to close, so we closed.

P4: The Ministry of Education ordered the closure! Closed is closed.

P2: There are instructions here; I didn't think twice.

P1: Certainly, the decision of the legal authorities binds everyone.

The principals’ explanations of their decisions to comply with the regulations revealed their trust in the government's decision‐making process. As P4 put it:

This is a matter for the state, and I appreciate the state in this regard. Because, between you and me, if it weren't for the state, people would “eat each other alive” [a paraphrase of a biblical passage]. I mean, the state knows things that you and I don't, and therefore, I accept the decision making.

Similarly, P6 said: “It was clear to me that closing schools was a drastic step and that the state would not have done so unless it was essential.” P11 emphasized a broader perception of trust in the law: "It's clear to me that I'm subject to the rules, and I'm not above the law. There are rules in this world, and if the rules of the state tell me to close, why wait? … The law is the law.”

Compliant principals were dismissive of a query about whether fear of enforcement played a role in their decisions. They emphasized the legitimacy of the regulations:

P16: We were less concerned about enforcement; this is a matter of responsibility, and because of this responsibility, we didn't take any risks.

P17: [Enforcement] wasn't a factor… I think that this was the right call, that if this thing is contagious, then, oh my God, what might happen if 600 children are there together? […] I really think there are no two sides here.

At the same time, some compliant principals perceived law enforcement as a real and likely scenario. As P9 explained: “I don't see any policy that would grant us any leniency in this regard… It's not like they say: ‘you know what, you're ultra‐Orthodox, open the school, teach, and have fun with it.’ This is really, really not the case […] Not at all!.” P1 referred to what would have happened had his school remained open: “I have no doubt that they would have sent [the police inspectors] and sent them in full force.”

Perceptions of scientific authority: Trust in the experts and professional rule‐making

Compliant principals were fairly knowledgeable of the health concerns underpinning the closure regulations. These principals trusted the law because they believed that the law was the product of a professional decision‐making process led by experts (during this period, ultra‐Orthodox media published numerous calls to follow the instructions by public health officials [e.g., Honig, 2020a; Lavie, 2020b; Lustigman, 2020; Rosner, 2020b]). As P6 put it:

Amidst all the political games, we're familiar with all of the tricks… it seemed that this time, it's serious, that this is a health matter, driven by health considerations, that these are experts who study what happens elsewhere, diagnose, assess, and issue instructions to the public.

For some principals, trust in the judgment of experts was tied to the principals’ acknowledgment of their limited understanding of the science of the pandemic:

P13: I don't understand what stops a pandemic… there are experts [for that purpose], and if they decided to ruin our economy, then it must be a serious event.

P6: If the government consults healthcare and pandemics experts, and they say that schools should close down because social gatherings should be reduced, who am I to disagree?

Perceptions of communal sources of authority: It's complicated

The compliant principals comprised members of two ultra‐Orthodox subgroups: Sephardic and Lithuanian. Sephardic principals experienced little conflict between the legal authority and the communal authority, as P17 noted: “We asked [the head of the Sages Council] Rabbi Shalom Cohen, and he instructed us emphatically that we are obliged by all the rules of the Ministry of Health… without any deviation.” Thus, it is not surprising that all Sephardic principals in our interview sample complied with the regulations. In contrast, Lithuanian principals faced a conflict because the prominent communal authority they followed adopted a defiant position (which was publicized by communal media: Katz, 2020a, 2020b; Lavie, 2020c; Rabinovich & Breiner, 2020), begging the question: How did these principals come to comply with the law rather than with the rabbinic instructions? The interviews revealed that compliant Lithuanian principals were acutely cognizant of the health risks involved in keeping schools open, and their approach toward their rabbis was very critical. For instance:

P2: [The rabbis] are doing the wrong thing; they are doing the wrong thing in all respects.

P12: This is a pandemic… there shouldn't have to be any dispute here… In a situation like this, everyone should comply with the Ministry of Health's instructions […] The fact is that [the rabbis] changed their minds [agreeing to close the schools in the end].

P11 did not want to share his views about the rabbis’ instruction to keep ultra‐Orthodox schools open: “This makes me furious. Can I pass on this question?” he asserted, “It makes me so mad, and I ask you to permit me not to answer.” P11 also confessed that he deliberately avoided consulting rabbis about his decision to close the school: “I didn't ask because this matter was very, very clear to me… I thought it's unhealthy and dangerous [to keep the school open].” P6 couched his reproach in softer terms, saying the rabbis were “slow to grasp” the situation.

Defiant school principals

The ultra‐Orthodox and the general media reported on dozens of defiant institutions that continued business as usual, without taking any special precautions against the pandemic (Katz, 2020g; Rabinovich, 2020a; Wiesz, 2020c; Kann News, 2020a; e.g., “Hundreds of boys gathered to study in Yeshiva X”; “Yeshiva Y: A notice affixed to the study hall entrance said, ‘the Yeshiva informs the students that the Ministry of Health notification should be disregarded, and school proceeds as usual’”). According to the media, confirmed by our interviewees, other defiant institutions acknowledged a change in routine by teaching in small groups of 10 students, staggering the breaks, and seeking to improve the sanitary conditions (Bornshtein, 2020; Nachshoni & Cohen, 2020; Rabinovich, 2020c; Weisz, 2020b). Whereas these steps mimicked the pandemic guidelines applied to the labor market at the time, they disregarded the mandated full school closures.

A crucial attribute of this form of defiance, which we will revisit in our discussion of the bidirectionality of legal socialization, was that it was not an independent act. The interviews revealed that defiant principals were not lone wolves; they acted with the consent or at least the acquiescence of the municipal leadership and the police:

P8: In the beginning, we received permission to [keep the school open for an] additional ten days, and once they revoked this permission, we closed.

P14: The municipality told us that [teaching in groups of] ten and ten are possible… the municipality said that [name of an ultra‐Orthodox town] had obtained special permission.

P7: We finally closed last weekend. As long as the [city] security inspector permitted teaching in small groups of ten, abiding by all the guidelines, we did it.

P5: There was an agreement with the authorities that we may remain open in groups of ten and ten […] all primary schools in [name of ultra‐Orthodox dominant city] operated that way […]. We understood that this [practice] was sanctioned by the authorities.

These accounts came from principals in ultra‐Orthodox‐dominated towns and cities, where the municipal government is either entirely ultra‐Orthodox (e.g., Bnei Brak) or dominated by ultra‐Orthodox council members (e.g., Jerusalem). Ultra‐Orthodox media similarly reported that these municipalities decided to open schools and teach in small groups (HaMevaser, 2020a; Peper, 2020). However, it would be incorrect to infer that defiance was the norm in these localities, as we found compliant principals in all of them. We return to this form of local subversion and the interactions between defiant principals and the police in our discussion of the bidirectionality of legal socialization.

Perceptions of the law: Unclear, irrational, and insufficient as a justification for action

In contrast to the compliant principals, the defiant principals’ perceptions of the regulations were complex, reflecting tension and dissonance. First, almost all defiant principals declared outwardly that they complied with the regulations, and only later did they acknowledge that they, indeed, deviated from the regulations (see Figure 1). For example, P5 passionately said, “we complied, we obeyed the law!” However, he also referred to his agreement with the authorities to remain open as an act of “the authorities shutting their eyes,” and explained that he decided to close the school after realizing that “from now, there will be serious enforcement,” implying that previously, he took advantage of the weak enforcement to remain open. Second, whereas the compliant interviewees perceived their legal obligation as clear‐cut, the defiant interviewees portrayed the regulations as ambiguous and unclear:

P15: When we were open… I think it was sort of legal then […] There was a period that it wasn't fully defined.

P5: The instructions might not have been so clear […] At first, no one talked like this [about enforcement and sanctions]; it sounded more like a recommendation than a dictate.

P10: At first, it wasn't clear whether the order is unequivocal, so we studied for a day or two, then closed, then opened in the form of ten‐ten students [ten students per group].

The narrative of legal ambiguity not only conflicts with the compliant principals’ perception of the law as unequivocal; it is also at odds with the defiant principals’ own narrative of compliance. For if the law is so unclear, how can principals be confident they complied with its dictates?

Third, the defiant principals’ approach toward the law was ambivalent and often distrustful. They were expressly critical of the law and challenged the justifications for closing schools while regular workplaces and other activities were allowed to continue operating under restrictions:

P5: I see no reason [to close the school]… It's more dangerous for the kids to wander in the house and the streets than for us to teach them in groups of]ten students]. If the ten‐ten format [i.e., teaching in groups of ten students] is approved everywhere else, then why should ultra‐Orthodox schools not be allowed ten‐ten?

P14: The decision to close schools without ordering a full lock‐down is a matter I don't understand. What difference does it make where kids meet–– in the park or in school? […] It's worse meeting in parks. In schools, 30 kids are together… in parks, 200 kids are together.

Several principals compared the necessity of keeping ultra‐Orthodox schools open to keeping the military operating, perceiving their schools as infrastructures critical to the state. P10 argued in this regard: “Will they close the military? No, right? You cannot close the military… Here is your answer!”

Perceptions of scientific authority: Cherry‐picking what directives to apply

On the one hand, defiant principals took the pandemic very seriously, emphasizing the importance of health recommendations (e.g., “If this is what produces contagion, then there's no choice, we must close” P8). This aligned with the salience of these recommendations in the ultra‐Orthodox media, including calls by prominent rabbis to follow distancing and self‐isolation guidelines (Honig, 2020b; Katz, 2020f; Lavie, 2020d; Rosner, 2020e). On the other hand, defiant principals were critical of the professional decision‐making process underlying schools’ regulations and believed that they knew how to stop the disease better than the experts. As P5 asserted: “From a health perspective, if [students] were to remain in groups of ten, they would be in a hygienic place, in a place with hand towels, soap, sanitizers. Now, where are they? How long can they stay at home? [after] one hour, two hours, they go off to the playground.” Ultimately, defiant principals cherry‐picked what health directives to follow: They adopted the general instructions regarding distancing and sanitation while disregarding the specific instruction to close schools.

Perceptions of communal sources of authority: Marking the boundaries of the law

Defiant principals followed Rabbi Kanievsky's order to remain open despite the closure regulations (the order was widely reported, e.g., in Efrati et al., 2020; Katz, 2020d; Lavie, 2020c; Wiesz, 2020a). Furthermore, the practices that defiant principals applied in their schools—splitting up classes to small groups and improving sanitation conditions—were consistent with specific directives from Kanievsky and other rabbis (Farkash, 2020; Lavie, 2020a; Rabinovich, 2020b). However, the defiant principals’ reliance on communal authority was not absolute. We compared the timing of when the defiant principals closed their schools with the concurrent position of Rabbi Kanievsky. It appears that all defiant principals closed their schools between March 18 and March 26, in advance of when Rabbi Kanievsky so instructed on March 29) Hacohen, 2020; Lavie, 2020f; Rabinovich, 2020d; Rosner, 2020c). Most closed their gates immediately after the Ministry of Health issued a letter addressing ultra‐Orthodox schools and stating that they must close immediately (the letter was publicized in the ultra‐Orthodox media: Efrati et al., 2020; Hadrei Haredim, 2020b; HaMevaser, 2020b; Lavie, 2020e). When asked about the seeming discrepancy between their ultimate decision to close and rabbinical authority, most principals dodged the question and did not offer clear answers.6

Paradoxically, even though direct and specific regulations drove the timing of their closures, defiant principals did not perceive the law as the key factor in closing. Although they ultimately made their own calls, defiant principals still justified their decisions in religious terms. For instance, P8 noted, “Once there was a decree, I informed everyone in a voice message that we have no choice, and [I reported] what they had ordered us. Frankly, I don't see this as a state order; this is [our obligation, in tune with the biblical verse:] ‘take heed for your souls’ [paraphrasing Deuteronomy 4:15/Berakhot 32b].” Similarly, P10 said: “And you should take great care for your souls” […] This is Torah, it's not the state that decides.” P3 referred to the existence of a legal rule as “a consideration, but the [religious] consideration of continuing teaching is more important.” In sum, despite legal pressures that ultimately led to the closure of schools, legal authority was bound by communal authority in two ways: First, principals felt confident in defying the law, in congruence with rabbinical instructions, marking a clear boundary of the law's reach; second, even as defiant principals were brought to compliance, they continued to perceive legal authority as bound by religious considerations.

Bidirectional legal socialization and the attenuation of the law

In this section, we describe the interplay between communal authority and legal authority that resulted in bidirectional legal socialization and in the attenuation of law. The attenuation of legal obligations into weakened norms during the COVID‐19 crisis was initiated by the community and engaged all levels of government—national, municipal, and street‐level. The data revealed a meticulously subversive system in which defiant communal authorities leveraged political power to transform the general, potent law into a tailored and attenuated community norm; in response, the police abdicated their charge to enforce the law and essentially provided ultra‐Orthodox schools an imprimatur for defiance. Moreover, whereas these dynamics appear to portray the sequence of events pertinent only to the defiant principals, compliant principals took notice and concluded that the law was not as potent and binding as they initially perceived.

National leadership: Modifying state power by negotiating compliance

The attenuation of the coronavirus regulations began almost immediately after being announced, as Rabbi Kanievsky publicly declared that ultra‐Orthodox schools would remain open (e.g., Adamker, 2020a; Katz, 2020a; Lavie, 2020c; Sherki, 2020). The general media reported on hectic negotiations between the government and the rabbis (Rabinovich, 2020b; Kann News, 2020b). Although these negotiations were not open to the public, and their outcome was never reported, the government's inclination to negotiate sent a message to school principals’ level that the ultra‐Orthodox community was not compelled to conform to the same norms obligating the rest of the citizens. As one defiant principal asserted: “Negotiation is a good thing. It was the right thing to do it slowly‐slowly… Just like [the state] negotiates with the Arabs, there is also negotiation with the ultra‐Orthodox” (P14). P11, a compliant principal, argued that this approach undermines the rule of law and harms ECs:

I get the feeling that the state says that two populations are under the radar––the Arabs and the ultra‐Orthodox. But no! The law should be enforced on all. Most of the public obeys the law, and these groups [Arabs and the ultra‐Orthodox] should be dealt with as well… [they] shouldn't be exempted from the norm, especially in matters of health.

Despite their differences, the compliant and defiant principals understood the message in the same way: The community's bottom‐up challenge could and had attenuated the law, not only regarding the ultra‐Orthodox community but regarding the ECs generally.

Municipal leadership: Modifying legal norms by exercising state powers

The second scene reflecting bottom‐up legal socialization was the municipal government in ultra‐Orthodox‐dominated localities, where the community worked to modify legal norms by directly exercising state power. In these areas—which quickly emerged as the national hot spots for the virus (Lustigman, 2020; Rosner, 2020f, 2020g; Yod, 2020)—defiant schools and local governments collaborated to replace the general obligation to close schools with an attenuated obligation to operate allegedly “safe” schools. As noted in M314: “In a quick municipal operation, the city of Bnei Brak matched religious schools to educational facilities to continue Torah instruction while following safety guidelines.” Peper (2020) provided a similar report on Modiin Illit. We discussed these local agreements when we discussed the legal perceptions of the defiant principals. During the crisis, the local modification of state law socialized principals into understanding that the law was contingent upon the ultra‐Orthodox authorities’ consent. Moreover, the law was open to negotiation that would likely result in exemptions from state‐wide rules. Thus, when defiant principals were asked if they had considered the possibility that the government would send inspectors that might close the school or fine it, a typical reply was, “No, if I have authorization from the city, what can they do?” (P14).

Although the municipality tailored state law to accommodate the defiant principals’ demands, it did not socialize principals to perceive the law as more legitimate, nor did it enhance their trust in legal authorities. Instead, defiant principals perceived the law as confusing and irrational: “It was a gray zone; it was ambiguous,” said P15, referring to the municipality's ``authorization’’ to open his school. Both P5 and P14 referred to the decision to cancel these ``authorizations’’ and close schools with the rise of the pandemic as “a matter I don't understand.” Their accounts clarify that the municipal accommodation of the community's demands attenuated the law in two respects: First, it diminished the legal obligation into a weaker norm. Second, it delegitimized the law itself.

Law enforcement: Changing the meaning of ``Compliance’’

The final arena of bidirectional legal socialization is perhaps the most critical: encounters with the police. Encounters with the police traditionally reinforce the law with concrete meaning and teach citizens what is expected of them (see Geller et al., 2021; Tyler & Trinkner, 2018). However, when masses of citizens defy the law, they teach the police the boundaries of their own power.

The schools’ defiance during the coronavirus crisis took several forms. The ultra‐Orthodox media reported on many schools that defaulted to remain open until the police forced their closure (Adamker, 2020b; Cohen, 2020b; Katz, 2020e; Rabina, 2020b). For instance, the following report appeared in Hadrei Haredim, a popular ultra‐Orthodox website (Hadrei Haredim, 2020a):

An informant in the school [said] that he asked Rabbi X what to do, and the rabbi told him: “Here in the yeshiva, the person who decides is the ‘Minister of Torah’ [Rabbi Kanievsky's byname], and as long as it is feasible and until further notice, students will stay in school; [this will remain the case] unless we'll have no choice, and the police come to evacuate us.

Nevertheless, even after the police arrived, ultra‐Orthodox media reported that many schools defied orders to close their doors (Hadrei Haredim, 2020a). In most cases, the police did not force school closure but attempted persuasion and deliberation. As one report indicated, “The police came to the place and requested its closure. After negotiating with school leadership, the police left, leaving the situation the same as when they arrived, and for now, the school continues as usual” (Hadrei Haredim, 2020a). Another report similarly noted: “Tens of thousands of ultra‐Orthodox students learned today, as usual, with the police settling for just issuing warnings… The police tried to close ultra‐Orthodox institutions through dialogue, and senior officers met with Rabbi Kanievsky regarding this issue, but to no avail” (Rabinovich & Breiner, 2020). The blow to police power was also described by defiant principals who encountered the police. Rather than enforcing closure or threatening the principals with sanctions, the police settled for verification that the defiant schools maintained physical distancing and adequate sanitary conditions. As P5 described:

I never felt I was doing anything illegal for an instant. The police came twice […] they didn't tell us: “Close, break up the gathering, and go home.” […] [The officer] never told me: “Listen, what you're doing is wrong; go home.” […] He photographed all of the classrooms; he photographed the bathrooms, the soap containers we placed there… he took photos of everything! I don't know whom he sent them to; apparently, to his commander.

P3 shared a similar story: “[Police] inspectors came here, and overall, it passed with no incident […] They said that each classroom was arranged properly, and they said that was fine.”

As the community socialized the police to observe the limits of their clout in the face of mass defiance, defiant principals were also socialized, in turn, by the actions of the police. P5 noted in this regard: “I think that the police also misunderstood the law […]; it seems to me that there was some kind of failure in the law enforcement system […] Or maybe this was a directive from the top [of the police command] concerning the ultra‐Orthodox community […] Maybe they shut their eyes.” It was only when the police began enforcing the law that the defiant principals closed, but by then, the lesson had already been internalized: The community has the capacity to bound police authority. Furthermore, compliant principals were also socialized by police behavior: “As you know, during the first few days, the police were not even close to patrolling and enforcing these rules,” said P16. This lack of enforcement taught him that “At first, the decision wasn't as binding as it is today.” The negative social learning of compliant principals may foreshadow their future behavior. Principals who witnessed potent enforcement learned that the law itself is potent: “In this area, we have Lithuanian schools who were told by Rabbi Kanievsky at the time to continue teaching… they opened and were issued tickets and fines,” said P9, “this is why… I don't see any policy that would go easy with us in this regard.” However, P12, who witnessed the police's interactions with defiant principals, appeared to reach a different conclusion, saying, “there was no coercion, [so] people realized this is up to them.”

DISCUSSION

We investigated how enclave communities respond to the law in times of a collective crisis and how these responses socialized both the community and the state. Drawing on semi‐structured interviews, various documents and media sources, and a field survey, we found that the state has the capacity to quickly internalize new norms and harness the cooperation of traditionally suspicious communities. Indeed, in our estimation, about half of all ultra‐Orthodox schools complied with the government's COVID‐19 regulations. Compliant principals perceived the regulations as unequivocal, legitimized state power, believed that the regulation process was professional and trustworthy, and rejected the notion that the regulations should be bounded by communal authority. At the same time and in the same locales, communal authorities managed to shield widespread defiance from legal enforcement. Legal behavior was intertwined with legal perceptions, as defiant principals—in stark contrast to compliant principals—perceived the regulations as unclear, had little trust in the regulation process, cherry‐picked which health directives to follow, and subjected legal authority to communal authority and norms. Defiance did not only refute the law; it transformed the law. Taken together, the data revealed a meticulously subversive system in which defiant communal authorities leveraged political clout and used the tool of mass defiance to negotiate the terms of compliance. Public authorities, apparently assuming that the community could not be brought to compliance, lowered their expectations and curtailed enforcement efforts, providing the schools an imprimatur for defiance.

This defiant behavior alludes to previous teachable experiences (as defined by Tyler et al., 2014) involving the ultra‐Orthodox community and the state. This relationship has been characterized by repeated failures to implement regulations in ultra‐Orthodox schools (Perry‐Hazan, 2015a, 2015b) and by informal consultations between community leaders and street‐level bureaucrats that restrained government authority (Barak‐Corren, 2017). Whatever the reasons, the outcome we reveal is the state's succumbing to the dynamics of “learned helplessness” (borrowing from Seligman, 1972; see Arnold, 2015), which carries a substantial cost in times of crisis.

These bidirectional processes of legal socialization comprise a feedback loop in which legal power is shaped by community pressures and, in turn, shapes the community's legal responses. The community uses its defiance power to socialize state authorities to acknowledge their bounded authority and attenuate the power of law, and, in turn, the state socializes the community to operate outside the law by desisting from law enforcement. When schools choose to defy the law, and law authorities choose to avoid enforcement, the authorities simultaneously become students who learn the boundaries of their power from the community and teachers who validate the community's testing of the limits of state power. In this interplay, each side observes the legal behavior of the other and absorbs lessons for the next encounter. As we found, even compliant decision‐makers observe and conclude that legal authorities are not as committed to law enforcement as they initially believed. Indeed, when the state manifests a position of learned helplessness and empowers defiant principals, it teaches all principals that the power of law is limited. Thus, in the next crisis, the compliant principals might think twice before legitimizing the law and other considerations—rabbinic, health‐oriented, or others—may take the lead. As P12, a compliant principal, reasoned, when there's no enforcement, “people realized this is up to them.” Indeed, a survey conducted in November 2020 revealed that about 67% of ultra‐Orthodox parents reported that their children's school was open during the mandated closure (Askaria, 2020; this comprised a considerable rise from the ∼42–51% that were open in March, according to the present study).7 In January 2021, the Ministry of Education reported that about half of all COVID‐19 infected students nationally were attending ultra‐Orthodox schools (despite comprising only 20% of the nationwide student population, Dattal, 2021; see also Kingsley, 2021).

Our study demonstrates that citizens and authorities adopt behaviors that are not always reciprocal in the positive sense that legal socialization scholars envisioned (Fine & Trinkner, 2021; Tapp & Levine, 1974; Trinkner & Tyler, 2016). Rather than collaborating for mutual benefit to advance the law, citizens, and authorities may interact in ways that erode the law and constrict the boundaries of state authority. This notion contributes to the study of legal socialization in two critical ways: First, it shows that the influence of citizens on legal authorities should be conceptualized in terms that tap both constructive and destructive interactions. Indeed, the interactions in the present case were destructive in the dual sense that they eroded the law and contributed to the spread of the pandemic; however, authority–citizen interactions can also be constructive if they expose injustices and yield beneficial reforms, or they may even be ``positively destructive,’’ for example if they erode an unjust law.

Thus, we propose expanding the meaning of reciprocal legal socialization processes and conceptualize them as bidirectional legal socialization. This concept corresponds with Bottoms and Tankebe's (2012) arguments regarding the dialogic character of legitimacy. However, it is also broader in encompassing the reality that power holders might not necessarily quest moral legitimacy that would facilitate buttressing the rule of law but rather prioritize political stability, conflict avoidance, and other pragmatic goals that may ultimately erode the rule of law.

Second, whereas previous studies of bounded authority analyzed the negative impact of increased intrusion by legal authorities (Murphy, 2021; Tyler et al., 2014), our study highlights the potentially harmful impact of decreased intrusion. The immediate consequence of the massive defiance we described was that the community suffered disproportionately from the disease, and the country experienced an intense breakout of the virus and dire economic consequences. In the long run, decreased legal intrusion may erode the rule of law itself.

Our conclusions may apply to other ECs with high levels of legal cynicism and distrust of the state. Previous studies traced the legal perceptions and behaviors of ethnic and racial minorities to their neighborhoods’ contextual conditions, particularly those characterized by concentrated disadvantage and crime (e.g., Sampson & Bartusch, 1998; Tyler & Fagan, 2008). Our study confirms the local environment's critical role in light of the attenuation of the law that we found in ultra‐Orthodox‐dominant locales. However, we cast this role in a different light: The local environment's negative impact on legal behavior does not necessarily arise from concentrated disadvantage—rather, it may arise from a concentrated advantage, namely concentrated political power that emboldens communal authorities to modify the law. Whereas the group‐position hypothesis presumes that minority groups’ negative views of the law may derive from their belief that they hold an unfavorable group position (see Blumer, 1958; Fine et al., 2019; Lockwood et al., 2018), our study indicates that such negative views of the law may also derive from minority groups’ perceptions of the law as subordinate and inferior to their group's systems of norms and political power.

Furthermore, our study exposes a factor independent of geography that may contribute to the erosion of the law in ECs––the interplay between legal and communal authorities. Erosion of the law can occur when EC members who are subject to conflicting sources of authority are sufficiently organized to pose a massive enforcement challenge. If the police must actively secure compliance rather than rely on citizens’ cooperation, achieving compliance becomes costly and uncertain (Tyler, 2007). Mass defiance forces legal authorities to confront the limits of their power, likely resulting in the law's attenuation, as in the present context.

Circumstances such as these are not unique to the Israeli context. Stolzenberg (2015) described the exercise of governmental power by religious EC authorities in a New York town, resulting in harnessing civil law for religious purposes. Weisbrod (1980) showed how utopian communities across the United States created autonomous regimes outside the reach of the law. More recently, religious communities in the United States and elsewhere filed lawsuits against pandemic restrictions on religious services (Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, 2020; South Bay United Pentecostal Church et al. v. Newsom et al., 2020) and sought to evade school closures (Danville Christian Academy v. Beshear, 2020; Monclova Christian Academy v. Toledo‐Lucas County Health Department, 2020). In other cases, communities did not turn to the courts but used their power of mass defiance to erode or drive change in the law. For example, the Grace Community megachurch in Los Angeles openly defied restrictions on mass gatherings without encountering enforcement (Cosgrove, 2020). In Minnesota, Catholic bishops planned to defy pandemic restrictions collectively, leading the governor to ease the rules (CNA Staff, 2020).

What should the government and the police do in such circumstances? Our work implies that the legal authorities should anticipate encountering considerable pressure to attenuate the law and devise their response to this pressure before allowing future confrontations to get out of hand. In the present case study, the governmental response brought about the worst of all worlds: legal authorities aided in a subversive effort to refute the law; they failed to secure the legitimacy of the law, which remained unclear and irrational in the eyes of the defiant principals; they taught compliant principals that enforcement was in abeyance and that each school was left to manage its own practices; and, most importantly, they proved to be accomplices in spreading the pandemic.

Alternative responses should be considered. First, if justified challenges emerge, legal authorities may choose to formally revise the law through a reasoned and transparent process (rather than the sporadic and subversive modification that characterized the present case). Second, in dealing with the key personages, those representing the compliance and defiance camps should be addressed discretely: legal authorities should seek ways to reinforce compliant decision‐makers (e.g., by ensuring they have the means necessary for compliance and that compliance is noticed and appreciated) and address defiant decision‐makers individually, providing them with substantial, convincing grounds for action to strengthen the law's authority (e.g., more detailed scientific or procedural explanations; assuming that communal authorities cannot be brought to compliance, as in our case). While suasion of the defiant principals might seem unlikely, the present study demonstrates that positions can be malleable. The fact that many school principals were willing to comply with the regulations and trust the law, despite a history of suspicion of state authorities and weak law enforcement in ultra‐Orthodox schools (Perry‐Hazan, 2015a, 2015b), highlights the prospect of restructuring relationships between legal authority and ECs, based on compelling reasons and fresh teachable experiences. This is not to say that suasion should be the ultimate enforcement effort, as hard enforcement will be needed when suasion fails. Indeed, abdicating enforcement altogether is harmful for the rule of law. Determining when to switch from soft measures to hard enforcement will depend on the circumstances, influenced by the severity of the defiance, the harm it causes, and the likelihood of achieving compliance through other methods.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

In this study, we examined how decisions were made by all sides of an acute legal conflict in real time and triangulated our findings using a field survey, analysis of documents and media sources, and interviews with school principals. Absent from our study are data from police officers and municipal officials, which could have elucidated these agents’ motives and add another layer to our findings. We concur with Bottoms and Tankebe (2012) that such studies can advance our understanding of the dynamic relationship between law and its constituencies. Whereas we were unsuccessful in obtaining such data for the current project, given its time constraints, we are currently engaged in research incorporating government agents’ input concerning the enforcement of core‐curricular regulations, a long‐standing focus of conflict.

A further limitation is the incomplete data regarding schools’ compliance with the regulations. Given the limited time frame available between when the regulations took effect and the beginning of the prescheduled holiday break, we were unable to condense the survey of ultra‐Orthodox schools. We sought to mitigate this shortcoming by cross‐checking our survey findings against our interview data and the additional collected materials. As all sources corroborated that noncompliance with COVID‐19 regulations was widespread, the precise rates were not central to our primary findings regarding the perceptions of law and the bidirectionality of legal socialization.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Appendix 1: Interview Guidelines

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are indebted to Gilad Elituv, Gil Nachmani, Shelley Robinson, Oriel Shmidov, and Hen Yeffet for excellent research assistance. They also thank Benny Benjamin for helpful comments, the Israeli Science Foundation (Grant 1487/19) for financial support, and the interviewees for contributing their time and thoughts.

Biographies

Netta Barak‐Corren is a legal scholar and cognitive scientist, who focuses on empirical and behavioral analysis of constitutional and public law, with a particular interest in conflicts of rights and the interaction between law and religion and law and social norms. Having obtained her first degree from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2012) and her doctorate from Harvard University (2016), Barak‐Corren is currently an Associate Professor of Law and the Academic Director of the Center for the Study of Multiculturalism and Diversity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her scholarship was published or is forthcoming in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, the Journal of Legal Studies, Management Science, Judgment and Decision Making, and Regulation and Governance, among other publications.