Abstract

Objective

Why do some Americans trust the World Health Organization (WHO) during the COVID‐19 pandemic, but others do not? To date, there has been no examination of trust in the WHO. Yet the global nature of the pandemic necessitates expanding our scholarship to international health organizations. We test the effects of partisanship, ideology, the cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation, and nationalism on trust in the WHO and subsequently examine how this trust relates to preventive health behavior.

Methods

Multivariate analysis of original survey data from a representative sample of Americans.

Results

Democrats, liberals, and those with a strong cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation are more likely to trust the WHO's competence and integrity in responding to the COVID‐19 pandemic while Republicans, conservatives, and nationalists are less likely. Even though trust in the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has the largest impact on preventive health behaviors, trust in the competence of the WHO is also an important factor. These results remain robust after controlling for other covariates.

Conclusion

Pandemic politics in the United States is polarized along party and ideological lines. However, our results show that a fuller understanding Americans’ political trust and health behaviors during COVID‐19 requires taking the international dimensions of the pandemic seriously.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has taken thousands of lives, caused unprecedented changes in public health, and altered how Americans live, work, and interact. The virus also catapulted the World Health Organization (WHO) into everyday conversations of Americans significantly more than other global health crises. According to a survey by the Better World Campaign (March 2020), 46 percent of Americans have a lot of trust, 31 percent have some trust, and 12 percent have no trust in the WHO during the coronavirus pandemic.1 According to a Pew Research Center survey (April–May 2020), 46 percent of Americans say the WHO has done a good or excellent job and 51 percent say it has done a poor or fair job in handling the pandemic.2 What explains this heterogeneity? Who trusts the WHO's ability to deal with the pandemic and the information it provides? To what extent does trust in the WHO predict preventive health behavior? Despite a burgeoning body of public opinion research related to COVID‐19, no study to date has examined Americans’ trust in the WHO. Our research undertakes this task, exploring the international dimensions of pandemic politics in the United States.

The literature investigating trust in national governments is deep and far reaching (Citrin and Stoker, 2018; Levi and Stoker, 2000) and analyses of trust in governments and domestic health agencies like the CDC during the pandemic is growing (Devine et al., 2020; Udow‐Phillips and Lantz, 2020; Dryhurst et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020; Oksanen et al., 2020; Goldberg et al., 2020). Yet there has been no systematic examination of what shapes public trust in the WHO during the pandemic and how this trust relates to preventive health behavior. This is an important omission. The mission of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) is limited to monitoring and preventing disease and outbreaks within the United States. The coronavirus pandemic, however, is a world‐wide pandemic and the WHO has spearheaded the global response to it. While trust in the CDC is an important part of understanding Americans’ health behavior, the global nature of the current pandemic requires that we expand our scholarship into investigations of international health organizations.

There is little question that public trust in the WHO is essential for the organization to fulfill its mission. As the WHO itself notes “[t]rust is the currency for communicating health risks.”3 For individuals to change their behavior in light of WHO guidelines, they must trust that the WHO has the competence to effectively manage the pandemic and believe that the information provided by the organization is credible and unbiased. If trust in the WHO is important to shaping Americans’ health behavior, then criticisms such as those raised by former President Trump regarding the WHO's handling of the pandemic could dramatically affect Americans’ beliefs and related health behaviors. Indeed as Trump sympathized with the “ostrich alliance”4 and public trust in his ability to deal with the pandemic declined,5 trust in the WHO became more critical in communities that were skeptical of Trump's management of the pandemic. Recent studies show that the WHO is a crucial source of information for many Americans (Yum, 2020). Therefore, explaining the basis of Americans’ trust in the WHO will lead to a fuller understanding of pandemic politics in the United States.

While the WHO gained considerable public attention due to COVID‐19, like many other international organizations (IOs), the WHO is generally far removed from most people's daily lives. Because people typically lack knowledge of the WHO, we argue that Americans take heuristic cues from different domestic and international sources in order to decide if they trust this organization. Since most people do not have sufficient incentives to conduct extensive research, or spend time deliberating about the trustworthiness of most IOs, they will rely on heuristics and cues from other sources to help inform their evaluations. Similar to how citizens process information and reach decisions in other areas of public opinion, we anticipate that people will rely on heuristics. So, we ask which heuristics matter the most? Because of the nature of the WHO, and the global reach of the pandemic, we question that partisanship and ideology are the only heuristics that citizens use when evaluating the WHO. While the partisan fights over the WHO might lead to the conventional wisdom that the public uses party identification as a cue for evaluating the WHO, we interrogate whether there are other heuristics that might play an even greater role given the nature of the pandemic and the mission of the WHO.

We argue that Americans take heuristic cues from their partisan identity, ideology, foreign policy dispositions, and sense of nationalism to form trust judgments about the WHO during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Using original data from a nationally representative survey, we show that Democrats, liberals, and individuals with a cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation and a low sense of nationalism are more likely to trust the WHO, believe that the information it provides is not marred by the political agendas of its member governments, as well as are somewhat more inclined to follow the WHO's safety recommendations during the coronavirus pandemic.

Our findings make a number of contributions. First, we offer the first systematic examination of the heuristics shaping Americans’ trust in the WHO and of the extent to which this trust translates into preventive health behavior. We add to the growing evidence indicating the importance of party identification and ideology as heuristics for pandemic politics (Shino and Binder, 2020; Fridman, Gershon, and Gneezy, 2020; Pennycook et al., 2020; Calvillo et al., 2020; Goldstein and Wiedemann, 2020; see also Kushner et al., 2020). Focusing primarily on partisanship and ideology, however, previous research has not fully considered the potential importance of the international relations paradigm in individuals' minds that is also likely to be an important factor in how citizens' evaluate iIOs (Rathbun, 2009; Bayram, 2017). We argue that scholars must move beyond the conventional “party‐centric” view of information processing and explore other heuristics that citizens likely use to evaluate IOs, global problems, and the factors that drive public trust in the WHO during a world pandemic. Our evidence indicates that even though the WHO has been pulled into political battles between Republicans versus Democrats, and conservatives versus liberals, when it comes to trusting or distrusting the WHO to handle the pandemic, a cooperative internationalist (CI) foreign policy orientation, embodying a preference for multilateralism and global cooperation, also matters because the WHO is an international organization and CI is a foreign policy heuristic. We further show that the general sense of distrust of international institutions embodied in a core sense of populist nationalism decreases trust in the WHO. Further, our exploratory analysis of the behavioral consequences of trust in the WHO suggests that trust in the CDC may be the main driver of Americans’ health behavior; trust in the WHO may also play an important role.

In the following sections, we develop our argument and derive hypotheses. We then introduce our methodology and data followed by the presentation of the results. The conclusion discusses the policy implications of our findings and makes suggestions for future research.

Party Identity, Ideology, Cooperative Internationalism, Nationalism, and Trust in the Who During Covid‐19

Throughout the literature there is substantial debate over exactly what trust means, as well as how to measure the construct. Yet there is consensus that trust is “relational” and involves “vulnerability” (Levi and Stoker, 2000; Citrin and Stoker, 2018). A trusts B to do X but accepts the risk of possible betrayal or failure (Hardin, 2000:26). Trust is also situational and domain specific. It can be extended or taken away based on the individuals, groups, or organizations involved, the political context, and the specific policy area under consideration. According to Citrin and Stoker (2018:50), “The foundation of trust is that A judges B to be trustworthy that he or she will act with integrity and competence… .”

What then might lead Americans to trust the WHO and believe it acts with integrity and competence during the coronavirus pandemic? Given that most Americans are poorly informed about foreign affairs (Carpini and Keeter, 1996; Baum and Groeling 2010; Colaresi 2007) and there are few incentives to expend the cognitive effort, or the time required, to become politically sophisticated about an international organization, it is conceivable that many citizens have poorly formed “non‐attitudes” about an organization such as the WHO. It is true that becoming politically sophisticated in an area of public policy, or about a particular organization, requires costly cognitive efforts that outweigh any investment return, at least for most people. Relying on heuristiccues dramatically simplifies the complexity of the political world and reduces any costs involved in making decisions or political evaluations. Particularly when there are sharp partisan and ideological divisions about an issue or topic, relying on partisan and ideological source cues is a rational shortcut that dramatically reduces the time and energy associated with information processing (Baum and Groeling, 2009; Berinsky, 2009; Cavari and Freedman, 2019; Colombo and Steenbergen, 2020; Rahn, 1993; Zaller, 1992). Since evaluating the competence and integrity of the WHO is a cognitively demanding task, particularly given the unique global complexity and uncertain information environment surrounding the pandemic, we expect that Americans are very likely to form trust judgments about the WHO based on mental shortcuts and cognitive heuristics, such as partisanship and ideology (Zaller, 1992)

Decades of research from psychology and political science has shown that individuals rely on cognitive heuristics when they face uncertainty and complexity. Cognitive heuristics are mental short‐cuts individuals use to reduce their mental load, especially when they face complex, incomplete, and risky information environments (Kahneman, 2011; Taversy and Kahneman, 1974; Simon, 1955; Lau and Redlawsk, 2001; Sniderman, Brody, and Tetlock, 1993)

Since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020,6 life has been characterized by information overload, stress, and fear. Throughout, the WHO has issued countless guidelines and recommendations, each updated as new scientific information becomes available.7 And, of course, there have been numerous positive and negative news reports about the WHO's handling of the pandemic. In this complex, uncertain, and anxiety‐ridden information environment created by the coronavirus, there is every reason to think that people will form trust judgments about the WHO using mental shortcuts. Further, even without a deadly pandemic, most people lack the time and resources to learn about IOs. Accordingly, we expect individuals to rely on heuristics when assessing the trustworthiness of the WHO during the coronavirus pandemic.

Which heuristics then shape Americans’ trust judgments of the WHO? We argue that people take cues from their party identification, ideology, foreign policy orientations, and sense of nationalism. Studies of public opinion have long argued that party identification functions as a biased filter for processing political information (Campbell et al., 1960; Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee, 1954; Zaller, 1992). Party identification is relatively stable, not because of an accurate assessment of ideological and political values, but because of the “partisan perceptual screen” that cognitive misers use to filter information, disregard different parts of complicated issues, and ultimately form different evaluations even when presented with the same set of facts (Campbell et al., 1960; Rahn, 1993). Party identity in the United States is imbued with ideological meaning. As a result of political events throughout the 20th century, political elites in both the Democratic and Republican party clearly aligned themselves with their respective liberal and conservative ideological values and the correspondence between party identification and ideology among the general public eventually became so interwoven that we now may have the largest “political polarization” in U.S. history (Fiorina, 2017). “The American Voter” described by Campbell, who was driven by their partisan perceptual screens, has now become the “New Partisan Voter,” driven by an alignment of partisan and ideological biases (Bafumi and Shapiro, 2009).

Pandemic politics in the United States have been polarized along political party and ideological lines. While the Republican leadership and conservative politicians and media have downplayed the threat of COVID‐19 and criticized the WHO, Democrats and liberals have consistently called for stricter measures and expressed support for the WHO (Calvillo et al., 2020; Rothgerber et al., 2020; Fridman, Gershon, and Gneezy, 2020; Clinton et al., 2020). On May 29, 2020, when former President Trump announced that the United States will terminate its relationship with the WHO accusing the organization of mishandling the pandemic, Democrats expressed deep concern, calling the decision to withdraw from the WHO irresponsible.8 The most senior Democrat on the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, Senator Bob Menendez, tweeted that this move “leaves Americans sick & America alone” (@SenatorMenendez, July 7, 2020). Menendez and Senate Democrats then promptly introduced legislation to reverse the administration's decision. On September 1, when the Trump administration announced that it will not join the global effort to manufacture and distribute a coronavirus vaccine because the WHO is involved, Democrats were deeply disturbed.9 Calling it a “political stunt” that risks American lives, on September 10, Democratic Senators Dick Durbin (D‐IL) and Cory Booker (D‐NJ) introduced a bill to ensure that the United States fulfills its commitments to the WHO and partakes in the global effort to coordinate the response to COVID‐19.10 In sum, the WHO's management of the pandemic has been a deeply divisive political issue between conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Accordingly, the heuristic cues provided by partisanship and ideology should be especially germane to trust judgments about the WHO. Specifically, we predict that Democratic party identification and liberal ideology will be associated with a higher sense of trust in the WHO while Republican party identification and conservative ideology will be associated with a lower sense of trust (H1).

Focusing only on party identification and ideology alone, however, ignores other potentially important heuristics that may drive public evaluations of the WHO. Because the WHO is an international health organization and the pandemic is a world‐wide crisis requiring a global response, we expect individuals to derive heuristic cues from their foreign policy orientations when evaluating the trustworthiness of the WHO. A strong body of scholarship has established that individuals have stable foreign policy orientations reflecting the international relations paradigms in their minds and in turn inform their attitudes and preferences on specific issues in world politics (Hurwitz and Peffley, 1987; Wittkopf, 1990; Holsti and Rosenau, 1990; Rathbun, 2009; Chittick, Billingsley, and Travis, 1995; Bayram, 2017). Cooperative internationalism (CI) is a specific foreign policy orientation marked by a preference for multilateralism and cosmopolitanism in international affairs (Rathbun et al., 2016; Wittkopf, 1990; Holsti and Rosenau, 1990). CI reflects support for international institutions and cooperation with other states for mutual gains and collective action. It also involves a concern for the well‐being of other countries and human beings and a sense of global solidarity. As an individual level predisposition, CI is a continuum. Individuals can score high or low on it depending on how strongly they embrace multilateralism and cosmopolitanism. Because it marks diffuse support for international institutions and global cooperation, an underlying endorsement of IOs embodied in CI should lead individuals to intuitively trust the WHO during the pandemic without actually scrutinizing the WHO's policies. In accord with recent studies that have demonstrated that people assess the legitimacy and trustworthiness of IOs by relying on heuristics instead of substantive information about IOs (Armingeon and Ceka, 2014; Nielson, Hyde, and Kelley, 2019; Lenz and Viola, 2017), we expect CI to be a particularly relevant heuristic for judging the competence and integrity of the WHO in managing the pandemic. Specifically, we hypothesize that higher levels of CI will be associated with a higher degree of trust in the WHO during COVID‐19 (H2).

Since nationalism is a broad and complex construct (Anderson, 1991; Brukaber, 1996; Gellner, 1983; Greenfeld, 1992; Smith, 1998), it is not exactly the antithesis of a commitment to global solidarity and international cooperation embraced by CI. Yet, there is evidence that nationalism can be related to distrust of IOs and international law in foreign policy (Herrmann, Isernia and Segatti; 2009; Wittkopf, 1990; Hixson, 2008; Von Borzyskowski and Vabulas, 2019). With the rise of populist nationalism in North America and Europe, a new skepticism about IOs has emerged. Indeed, targeting global governance institutions is a key tool in the populist political playbook because it allows populists to appeal to voters’ feelings of being left behind by globalization, laissez faire economics, and multilateralism (Copelovitch and Pevehouse, 2019; Verbeek and Zaslove, 2017; Voeten, 2020; Bayram and Thomson, Forthcoming). Populists perceive many IOs as corrupt, cumbersome bureaucracies, run by elite technocrats who are disconnected from the public they are supposed to serve, and who ultimately infringe upon national sovereignty and threaten national interests. Consequently, we expect nationalism to be an important heuristic for how Americans evaluate the competence and integrity of the WHO. In particular, we hypothesize that nationalism will be associated with a lower sense of trust in the WHO during the COVID‐19 pandemic (H3).

Finally, while the focus of our study is on the heuristics that the public may use to evaluate their trust in the WHO, we also present exploratory analysis on the possible link between trust and health behaviors. Existing research shows that trust in government and health agencies is associated with following preventive health behaviors such as getting vaccinated (Prati, Pietrantoni, and Zani, 2011; Siegrist and Zingg, 2014 Van Bavel et al., 2020; Bangerter et al., 2012; Quinn et al., 2009) and studies specifically focused on COVID‐19 have largely replicated these findings, showing that trust in government, medical professionals, and the CDC corresponds to greater compliance with social distancing and face covering recommendations (Dryhurst et al., 2020; Han et al., 2020; Oksanen et al., 2020; Olsen and Hjorth, 2020). Based on these findings, we expect that trust in the WHO during the pandemic may result in greater compliance with the health and safety recommendations of the organization (H4). However, it is also conceivable that trust judgments in the WHO have limited effect on health behavior because people are not knowledgeable about the WHO and its recommendations, which is the reason they rely on heuristics to form trust judgments in the first place. Given this possibility, we approach the final section of our analysis in an exploratory manner.

Data and Method

To test our hypotheses, we fielded a nationally representative survey of American adults administered by YouGov in September 2020.11 The survey instrument was created to capture respondents’ trust in the WHO and in domestic institutions during COVID‐19, health behaviors, foreign policy attitudes, as well as views on various public policy issues and demographic characteristics.

Our first outcome variable is trust in the WHO during COVID‐19. We measured it with four questions. The first two capture trust judgments about the “competence” of the WHO. We asked respondents how much they trust the WHO to manage the response to the coronavirus (Management) and how much they trust the WHO to provide accurate and timely information (Information) on the coronavirus. Responses were coded on a 5‐point scale anchored by “A lot (coded 5)” and “Not at all (coded 1).” The next two outcome variables measure trust judgments about the “integrity” of the WHO conceptualized as its neutrality and political independence from its member states in managing the pandemic.12 We asked participants how strongly they agree or disagree that the WHO acted independently of the political agendas of its member governments in managing the response to the coronavirus (Political Independence) and how strongly they agree or disagree that the WHO provided accurate and unbiased information on the coronavirus that is “not” affected by the political agendas of its member governments (Unbiased Information). Responses to both were coded on a 5‐point scale ranging from “Strongly agree (coded 5)” to “Strongly disagree (coded 1).”

Since we are also interested in the relationship between trust judgments and health behavior, our second outcome variable focuses on following health guidelines. We asked respondents whether they practice social distancing (Social distancing), measuring responses on a 3‐point scale of “Yes, very much (coded 3),” “Yes, somewhat (coded 2),” and “No, not at all” (coded 1).13 We also asked participants how well they comply with COVID‐19 health behavior guidelines generally. The variable Compliance is measured on a 4‐point scale ranging from “Very well (coded 4)” to “not at all (coded 1).”

Our key explanatory variables partisanship, ideology, CI, and nationalism are measured with commonly used questions drawing from extant research. For party identity we asked: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, Other or Are you not sure? “For ideology we asked: “In general, how would you describe your political viewpoint with response options ranging from “Very liberal (coded 1) to “Very conservative” (coded 5). We measured CI with four questions coded on a 5‐point “Strongly agree (coded 5)” to “Strongly disagree (coded 1)” scale: (1) It is essential for the United States to work with other nations to solve problems such as overpopulation, hunger, and pollution. (2) The United States needs to cooperate more with the United Nations and other international organizations. (3) In deciding on its foreign policies, the United States should take into account the views of its major allies. (4) The best way for the United States to be a world leader in foreign affairs is to build international consensus (α = 0.85). We measured nationalism with four questions coded on a 5‐point “Strongly agree (coded 5)” to “Strongly disagree (coded 1)” scale: (1) I believe in the motto: “My country, right or wrong.” (2) I am proud to be an American. (3) When I see the American flag flying I feel great. (4) Regardless of my feelings about President Trump, I too say “America first.” (α = 0.87).

We also controlled for fear of getting infected with the coronavirus (“How worried are you about the possibility of becoming infected with the coronavirus?” with response options ranging from very worried to not at all worried). Finally, we controlled for income (from less than $10,000 to $500,000 or more), education (from less than high school to postgraduate), race, gender, and age.

Results

We discuss the results in four stages. We start with presenting the descriptive statistics for trust judgments about the WHO during the pandemic, followed by an analysis of the effects of partisanship, ideology, CI, and nationalism on trust in the WHO. We then offer a series of robustness checks by controlling for other potential influences on trust in the WHO. We then examine how trust in the WHO affects compliance with COVID‐19 guidelines.

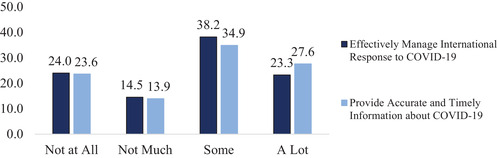

As can be seen in Figure 1, there is wide variation in American's trust in the WHO's competence. About 23 percent of the respondents have a lot and 38 percent have some trust in the WHO's ability to effectively manage the response to the pandemic. In contrast, over 38 percent of the participants are skeptical of the WHO's ability to manage the pandemic. Similarly, about 63 percent of the respondents trust the WHO to provide timely and accurate information on the coronavirus, about 37 percent do not.

FIGURE 1.

Trust in the Competence of the World Health Organization

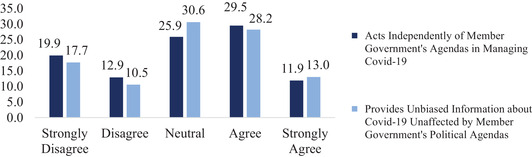

FIGURE 2.

Trust in the Integrity of the World Health Organization

As shown in Figure 2, trust judgments about the integrity of the WHO during the pandemic similarly indicate substantial differences. While about 41 percent of our respondents agree or strongly agree that the WHO has acted independently of the political agendas of its members, about 33 percent disagree or strongly disagree with this observation and about 30 percent of our respondents are neutral. A similar pattern exists regarding confidence in the information provided by the WHO. About 42 percent agree or strongly agree that the information WHO provides is accurate and unbiased and not tainted by the political agendas of member nations. About 33 disagree or strongly disagree with the credibility of the information provided by the WHO and about 26 percent are neutral.

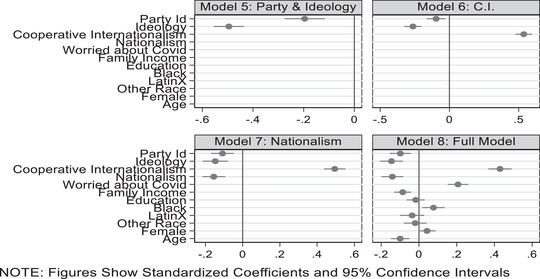

To test our hypotheses, we estimate a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, starting with trust in the competence of the WHO. The first four models analyze trust in the WHO's ability to effectively manage the pandemic. The next four focus on the WHO's ability to provide timely and accurate information about the pandemic. Here, we present the results of the models graphically; the models can be found in the supplementary Appendix. First, we regress the dependent variables Management and Information onto political party affiliation and ideology variables (see supplementary Appendix, Table A1, Models 1 and 5).

As shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, displaying standardized and centered coefficients along with their corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals, we see that both partisanship and ideology are important predictors of trust in the WHO, supporting H1. While Democrats and liberals are more likely to trust the WHO's management of the pandemic and its ability to provide timely and accurate information Republicans and conservatives remain skeptical. Next, we include the cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation to our estimations (supplementary Table A1 Models 2 and 6). We find that individuals who score high on CI express much greater trust in the WHO than those who score low, lending credence to H2. Next, we add nationalism into our estimations (supplementary Table A1, Models 3 and 7). As predicted by H3, nationalism is negatively associated with trust in the WHO during the pandemic and we see that the effect of nationalism is smaller than that of CI and comparable to that of ideology.

FIGURE 3.

Trust in the Competence of the WHO to Manage the Covid 19 Virus

FIGURE 4.

Trust in the Competence of the WHO for Accurate and Timely information

Finally, as robustness checks, we add control variables for fear of getting infected as well as for socioeconomic and demographic characteristics (supplementary Table A1 Models 4 and 8). We find that fear of being infected by COVID‐19 is positively related to trust in the competence of the WHO. We do not find significant effects associated with education, gender, or being Latinx. African Americans, however, were significantly more likely to report greater trust in the WHO while income was a negative predictor. Finally, older participants were less likely to trust the competency of the WHO. In terms of our results regarding party identity, ideology, CI, and nationalism, these findings remain robust in the face of additional controls, and a Wald test indicates a significant loss in model fit if these variables are omitted (F = 98.59, p < 0.000 for Model 4 and F = 111.51, p < 0.000 for Model 8).14

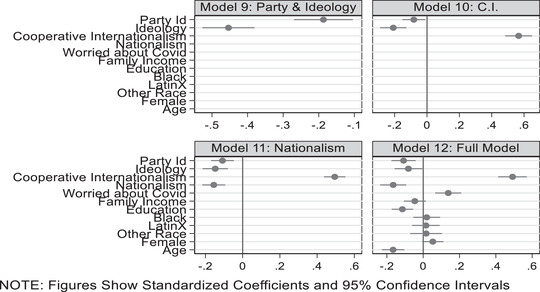

Turning to trust in the integrity of the WHO, as shown in Figure 4 (see also supplementary Appendix, Table A2), we start by regressing the dependent variables Political Independence and Unbiased Information onto party identity and ideology (supplementary Table A2 Models 9 and 13). Similar to our findings for the competence of the WHO, we observe that Democrats and liberals are more likely to think that the WHO acts independently of the political agendas of its members in responding to the pandemic and provides unbiased information, as predicted by H1. These findings are presented graphically in Figures 5 and 6 again displaying standardized and centered coefficients along with 95 percent confidence intervals.

FIGURE 5.

Trust in the Integrity of the WHO Act Independently of Political Agendas

FIGURE 6.

Trust in the Integrity of the WHO Provide Unbiased Information

As before, CI is an important predictor of trust in the integrity of the WHO, supporting H2 (Models 10 and 14). We also find that nationalism is a significant and negative predictor of trust (supplementary Table A2 Models 11 and 15), supporting H3. Also, similar to previous findings, the effect of nationalism is smaller than that of CI. Further, these findings hold even in the face of other controls (Models 12 and 16). As before, we find that fear of being infected by COVID‐19 is positively related to trust in the integrity of the WHO. Further, in terms of the WHO acting independently (supplementary Table A2 Model 12, Figure 5) income is not a significant predictor while education is a negative predictor. We do not find significant differences across race, ethnicity, or gender, but we do find that older participants were less likely to trust the integrity of the WHO.

In terms of providing unbiased information (supplementary Table A2 Model 16, Figure 6), we again find that education is a negative predictor, African Americans and women were more likely to report trust in the WHO, while older people were less likely to trust the WHO. Once again, the importance of party identity, ideology, CI, and nationalism remain robust even with additional controls and a Wald test indicates a significant loss in model fit if these variables are omitted (F = 76.12, p < 0.000 for Model 12 and F = 91.88, p < 0.000 for Model 16).

In sum, results provide strong support for H1, H2, and H3. We find that partisanship and ideology are critical predictors of trust in the WHO during the pandemic. However, the robust impact of CI across all the models also indicates that a focus on party and ideology alone misses the international dimension of trust in the WHO. Diffuse support for international institutions and cooperation reflected in CI plays a crucial role in shaping Americans’ trust in the WHO's political independence during COVID‐19. Similarly, the importance of nationalism as a source of distrust in the WHO is clear, indicating that COVID has not mitigated long‐standing nationalist misgivings about IOs.

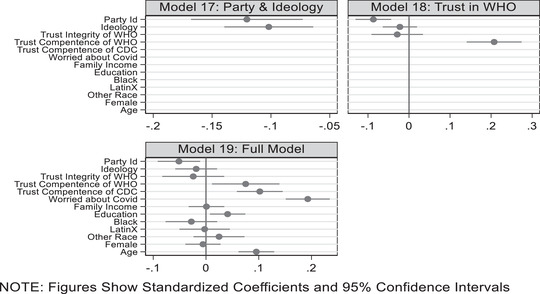

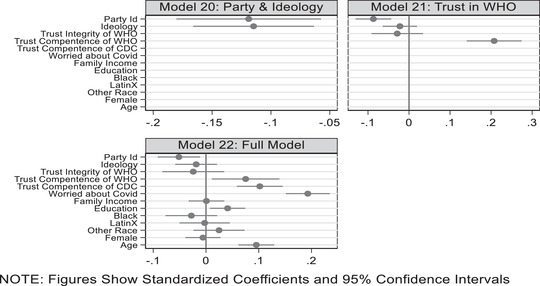

To explore the possible influence of trust in the WHO on health behavior, we start with a base model including party identity and ideology to predict participant's self‐reported Social distancing and health behavior Compliance (see supplementary Appendix Table A3, Models 17 and 20).15 We begin by looking at Social distancing behavior for which the findings are presented graphically in Figure 7. The findings for following health guidelines are presented graphically in Figure 8 .

FIGURE 7.

Social Distancing as a Function of Trust in the Competence and Integrity of the WHO

FIGURE 8.

Following Health Guidelines as a Function of Trust in the Competence and Integrity of the WHO

Similar to previous studies, we find supportive evidence that Democrats and Independents are more likely to practice social distancing and comply with COVID‐19 health guidelines. To test H4, we include the two variables measuring trust in the WHO's competence and integrity (Models 18 and 21). Results partially support H4. The coefficient for WHO's competence is statistically significant and moderately large. However, the coefficient for WHO's integrity fails to reach statistical significance. This suggests that when it comes to health behavior, trust in the WHO's competence matters more than its political neutrality. Given the demonstrated importance of trust in domestic public health agencies for health behavior, in our next set of estimations, we also control for trust in the CDC along with fear of getting infected and demographic factors (Models 19 and 22). In addition to fear of infection, trust in the CDC emerges as a strong predictor of both social distancing and compliance with COVID‐19 guidelines. Taking trust in the CDC into account also decreases the size of the coefficient for trust in the competence of the WHO, suggesting that Americans’ health behavior is likely driven more by what the CDC says than what the WHO says. On balance, we take the partial support for H4 as preliminary and suggest that the WHO may play a role in supporting health behavior while noting future research should consider these possibilities further.

Conclusion

The global nature of the coronavirus pandemic makes understanding trust in the WHO just as important as trust in domestic institutions. As one observer put it, “[o]nly the WHO has the membership (and thus, the legitimacy) to engage in collective action. Under the right leadership, the WHO can stand up to governments, mobilize global opinion on key public health issues, and create political will for action in a way that no one else can.”16 However, understanding of public trust in the WHO has largely remained uncharted territory. Our research addresses this glaring gap. We have argued that given the complex information environment surrounding the coronavirus pandemic and the “out of mind, out of sight” nature of the WHO as an institution, Americans rely on heuristics to form trust judgments about the competence and integrity of the WHO during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Specifically, we have hypothesized and showed that partisanship, ideology, cooperative internationalism, and nationalism are among the main heuristics that shape public trust in the WHO. Evidence from our representative survey indicated that Democratic party identity, liberal ideology, and a strong cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation led to trust that the WHO is capable of effectively managing the pandemic, providing timely and reliable information about COVID, and acting independently of the political agendas of its members, while Republican party identity, conservatism, and a strong sense of nationalism diminished trust in the WHO. We have also provided preliminary evidence that trust in the competence of the WHO may be a part of Americans’ health behaviors.

Our research extends existing studies on pandemic politics and health behavior in a number of ways. In showing that party identity and ideology are important predictors of trust in the WHO, we confirm previous findings that pandemic politics and health behaviors in the United States are highly polarized and that citizens use partisan and ideological heuristics to make decisions about IOs like the WHO. However, our results indicate that the literature characterizing the political trust during the pandemic solely as partisan or ideological paints an incomplete picture. The cooperative internationalist foreign policy orientation and nationalism are also critical heuristics that shape Americans’ trust in the WHO.

Important implications follow from our research. Scholars examining COVID‐19 are wise to remember we are facing a world pandemic and therefore not simply domestic agencies and attitudes are important. We must also study international institutions and foreign policy attitudes if we expect to fully understand the pandemic, public evaluations, and public behaviors. We found that trust in the competency of the WHO was predictive of health behavior, but trust in the integrity of the WHO was not. This suggests that partisan attacks on competency may be more damaging than attacks on the integrity and political autonomy of the WHO. Perhaps the WHO should worry more about criticisms of its competency to handle the pandemic and how its competency is evaluated by the public they hope to help. At the same time, since trust in the CDC appears more important than trust in the WHO for Americans’ compliance with COVID‐19 guidelines, collaboration between the CDC and the WHO seems critical in protecting Americans and saving lives.

Our study suggests an agenda for research that links the international and domestic dimensions of the pandemic. One useful avenue of inquiry will be exploring how elite and media framing of the WHO in the domestic realm affects trust in the WHO. Future research should also examine how attitudes toward world politics other than CI and nationalism might shape views on the pandemic. It is quite plausible that people who see themselves as cosmopolitans or have transnational ties are more trusting of the WHO during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Investigating why trust in the competence of the WHO predicts health behavior but trust in the integrity of the WHO has no effect will similarly constitute another useful direction of research. It is conceivable that the political independence and competence of the WHO weigh differently on Americans’ health behavior calculus because people have faith in the medical, technical, bureaucratic expertise of the WHO even if they doubt its political neutrality. We encourage future studies to provide additional tests of the trust‐behavior link using different model specifications and outcome measures.

The present study contributes to a deeper understanding of the international dimension of pandemic politics, yet some of its limitations should be noted. For example, could trust in the WHO be less about partisanship or foreign policy dispositions and more about trust in science and scientists?17 Our research cannot directly engage this criticism other than to note that given the scientific uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus, recent studies suggest that perceptions of COVID science can be colored by partisanship (Kreps and Kriner, 2020). Future research should examine the extent to which trust in the WHO can be attributed to a latent sense of trust in medical science. Such an inquiry will ideally be grounded in a larger theoretical framework allowing for a comparison of the importance of message content and message source in public opinion. Second, we are cognizant of the difficulty of capturing what people “really” know about WHO's health recommendations in our current design. Alternative research designs such as focus groups or interviews will allow researchers to directly investigate Americans’ knowledge of these recommendations, and this investigation will facilitate a fuller understanding of the trust‐behavior nexus. Similarly, time‐series data linking changes in trust to health behavior will be beneficial. We see our research is a first step in scratching the surface of the impact of the WHO on pandemic politics in the United States, and hope that future studies can offer additional tests of our hypotheses by exploring the causal mechanisms involved in trust judgments and health behaviors.

Supporting information

Table A1. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Competence: Management of Covid and Accurate Information

Table A2. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Integrity: Independence of Political Agents and Unbiased Information

Table A3. Following Health Behavior Guidelines as a Function of Trust in the Competence and Integrity of the World Health Organization

Table A4. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Competence‐GOLOGIT2

Table A5. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Integrity‐GOLOGIT2

Table A6. Following Health Behavior Guidelines as a Function of Trust in the WHO‐GOLOGIT2

Footnotes

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/more‐americans‐trust‐biden‐than‐trump‐to‐handle‐the‐pandemic.

See the WHO's updated timeline of the virus at https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/29‐06‐2020‐covidtimeline.

It is important to note that YouGov samples are “as if” representative; they are not directly drawn from representative random samples. Instead, YouGov uses sample‐matching techniques to create “representative” samples from nonrandomly selected pools of respondents in online panels. The sample‐matching technique first draws a stratified national sample from the 2010 American Community Survey. It then employs matching techniques to construct a comparable sample from its online panels. Members of the matched sample are then invited to participate in the survey. After the data have been collected, the sample is weighted to match the target population on a series of demographic factors. YouGov surveys are increasingly common in political science research. The main advantage of YouGov surveys is that, although the matched sample has been drawn from a non‐randomly selected pool of opt‐in respondents, it can in many respects be treated as if it were a random sample (Vavreck and Rivers, 2008). These matched samples resemble the broader public in terms of a number of sociodemographic variables.

This measure is inspired by Haftel and Thompson (2006).

Presented in the supplementary Appendix, results from generalized ordered logistic regression models yield substantively similar findings.

We also explored the possibility that religious beliefs might influence trust in the WHO. To explore this possibility, we included a measure of religious fatalism (Franklin et al., 2007) into the models presented in the manuscript and none of the substantive findings were changed. More specifically, respondents were asked the following four questions. I do not need to try to improve my health because I know it is up God. If an illness runs in my family, I am going to get it too. If I am meant to have an illness, changing my health habits will not help. I can control a small health issue, but only God can control a big health issue. Participants were asked if they strongly disagree, disagree, agree, or strongly agree with the statements and responses were coded so that low scores indicated belief in control while high scores indicated a belief in fate (α = 0.71). Results are available on request.

The models presented in the tables (see appendix) and figures are largely robust to diagnostic tests. Examining the unstandardized and uncentered variables presented in these models, we do not find evidence of multicollinearity problems. In Table A1 in the supplementary Appendix, there are no VIF values higher than 1.92 and the average VIF is 1.3 for the first full model and 1.31 for the second full model. The correlations between independent variables do not appear to be concerning and the correlation between party identification and ideology is 0.23. Similarly, in Table A2 in the supplementary Appendix, there are no VIF values higher than 1.85 and the average VIF is 1.26 for the first full model and 1.30 for the second full model. Finally, in Table A3 in the supplementary Appendix, there are no VIF values higher than 3.6 and the average VIF is 1.57 for both full models.

In our current analyses, we did include religious health fatalism as a proxy for trust in science/scientists in our full models. Fatalists see themselves at the mercy of fate and God and are skeptical of their ability to control their health and well‐being. Since medical science is about controlling and improving human health and condition, while imperfect, religious health fatalism might serve as a proxy for trust in medical science/scientists. Including religious fatalism in our models did not change any of the substantive findings or conclusions presented in the paper. Future research should consider more direct measures of trust in science and scientists.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, Benedict , 1991. Imagined Communities. New York: Verso Press. [Google Scholar]

- Armingeon, Klaus , and Ceka Besir. 2014. “The Loss of Trust in the European Union during the Great Recession Since 2007: The Role of Heuristics from the National Political System.” European Union Politics 15:82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bafumi, Joseph , and Shapiro Robert Y.. 2009. “A New Partisan Voter.” The Journal of Politics 71:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter, Adrian , Krings Franciska, Mouton Audrey, Gilles Ingrid, Green Eva GT, and Clémence Alain. 2012. “Longitudinal Investigation of Public Trust in Institutions Relative to the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic in Switzerland.” PLoS One 7:e49806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Matthew , and Groeling Tim. 2009. “Shot by the Messenger: Partisan Cues and Public Opinion Regarding National Security and War.” Political Behavior 31:157–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, A. Burcu , and Thomson, Catarina . Forthcoming. Ignoring the Messenger? Limits of Populist Rhetoric on Public Support for Foreign Development Aid. International Studies Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Bayram, A. Burcu. 2017. “Cues for Integration: Foreign Policy Beliefs and German Parliamentarians’ Support for European Integration.” German Politics and Society 35:19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. R. , Lazarsfeld P. F., and McPhee W. N.. 1954. Voting: A Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky, Adam. 2009. Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brukaber, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, Dustin P. , Ross Bryan J., Garcia Ryan JB, Smelter Thomas J., and Rutchick Abraham M.. 2020. “Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of Covid‐19 (and Susceptibility to Fake News About It).” Social Psychological and Personality Science 11(8):1119–28. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, A. , Converse P. E., Miller W. E., and Stokes D. E.. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cavari, A , and Freedman G. 2019. “Partisan Cues and Opinion Formation on Foreign Policy.” American Politics Research 47:29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chittick, William O. , Billingsley Keith R., and Travis Rick. 1995. “A Three‐dimensional Model of American Foreign Policy Beliefs.” International Studies Quarterly 39:313–31. [Google Scholar]

- Citrin, Jack , and Stoker Laura. 2018. “Political Trust in a Cynical Age.” Annual Review of Political Science 21:49–70. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton, Joshua , Cohen Jon, Lapinski John S., and Trussler Marc. 2020. “Partisan Pandemic: How Partisanship and Public Health Concerns Affect Individuals’ Social Distancing during COVID‐19.” SSNR. Available at 〈https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3633934〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaresi, Michael . 2007. “The Benefit of the Doubt: Testing an Informational Theory of the Rally Effect.” International Organization 61(1): 99–143. [Google Scholar]

- Colobom, Celine , and Steenbergen Marco R.. 2020. “Heuristics and Biases in Political Decision Making.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford; Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, C. and Steebergen M. 2020. “Heuristics and Biases in Political Decision Making.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford; Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Copelovitch, Mark , and CW Pevehouse Jon. 2019. “International Organizations in a New Era of Populist Nationalism.” The Review of International Organizations 14:169–86. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, Daniel , Jennifer Gaskell, Will Jennings, and Gerry Stoker. 2020. “Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature.” Sage Journals. Available at 〈https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1478929920948684〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpini Delli, and Keeter Scott. 1996. What American Know About Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dryhurst, Sarah , Schneider Claudia R., Kerr John, Freeman Alexandra L. J., Recchia Gabriel, Anne Marthe van der Bles, David Spiegelhalter, and Sander van der Linden. 2020. “Risk Perceptions of COVID‐19 Around the World.” Journal of Risk Research. 〈 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193〉 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorina, Moriss. 2017. Unstable Majorities: Polarization, Party Sorting, and Political Stalemate. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Monica D. , Schlundt David G., McClellan Linda H., Kinebrew Tunu, Sheats Jylana, Belue Rhonda, Brown Anne, Smikes Dorlisa, Patel Kushal, and Hargreaves Margaret. 2007. “Religious Fatalism and Its Association with Health Behaviors and Outcomes.” American Journal of Health Behavior 31(6):563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman, Ariel , Gershon Rachel, and Gneezy Ayelet. 2020. “COVID‐19 and Vaccine Hesitancy: A Longitudinal Study.” SSRN. Available at 〈https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3644775〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellner, Ernest. 1983. Nations and Nationalism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Matthew H. , Gustafson Abel, Maibach Edward W., Ballew Matthew T., Bergquist Parrish, Kotcher John E., Marlon Jennifer R., Rosenthal Seth A., and Leiserowitz Anthony. 2020. “Mask‐wearing Increased After a Government Recommendation: A Natural Experiment in the US during the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Frontiers in Communication 5:44. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, Daniel. A. N. , and Wiedemann Johannes. 2020. “Who Do You Trust? The Consequences of Political and Social Trust for Public Responsiveness to COVID‐19 Orders.” SSRN. Available at 〈https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3580547〉 [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld, Liah. 1992.. Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, Matthew A. , Tim, Groeling . 2010. “Reality Asserts Itself: Public Opinion on Iraq and the Elasticity of Reality.” International Organization 64(3): 443–479. [Google Scholar]

- Haftel, Yoram, H. , and Thompson, A. Alexander, T. , 2006. “The Independence of International Organizations.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50(2):253–75. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Qing , Zheng Bang, Cristea Mioara, Agostini Maximilian, Belanger Jocelyn, Gutzkow Ben, Kreienkamp Jannis, PsyCorona Team, Pontus Leander, and Somayeh Zand. 2020. “Trust in Government and Its Associations with Health Behaviour and Prosocial Behaviour During the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” PsyArXiv Pre‐Prints. Available at 〈https://psyarxiv.com/p5gns/〉 [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, Russel. 2000. “Do We Want Trust in Government?” in Warren M.E., eds., Democracy and Trust. 22–41. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, Richard K. , Isernia Pierangelo, and Segatti Paolo. 2009. “Attachment to the Nation and International Relations: Dimensions of Identity and their Relationship to War and Peace.” Political Psychology 30:721–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hixson, Walter L. 2008. The Myth of American Diplomacy: National Identity and US Foreign Policy. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holsti, Ole R. , and Rosenau James N.. 1990. “The Structure of Foreign Policy Attitudes among American Leaders.” The Journal of Politics 52:94–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz, Jon , and Peffley Mark. 1987. “How are Foreign Policy Attitudes Structured? A Hierarchical Model.” The American Political Science Review 81:1099–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, S.E. and Kriner D.L.. 2020. “Model Uncertainty, Political Contestation, and Public Trust in Science: Evidence from the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Science Advances. 6:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner Gadarian Shana, Sara Wallace Goodman, and Thomas B. Pepinsky. 2020. “Partisanship, Health Behavior, and Policy Attitudes in the Early Stages of the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” SSRN. Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3574605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz, Tobias , and Viola Lora Anne. 2017. “Legitimacy and Institutional Change in International Organisations: A Cognitive Approach.” Review of International Studies 43:939–61. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, Margaret , and Stoker Laura. 2000. “Political Trust and Trustworthiness.” Annual Review of Political Science 3.1:475–507. [Google Scholar]

- Nielson, Daniel L. , Hyde Susan D., and Kelley Judith. 2019. “The Elusive Sources of Legitimacy Beliefs: Civil Society Views of International Election Observers.” The Review of International Organizations 14:685–715. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, A. , Kaakinen M., Latikka R., Savolainen I., Savela N., and Koivula A.. 2020. “Regulation and Trust: 3‐Month Follow‐up Study on COVID‐19 Mortality in 25 European Countries.” JMIR Public Health Surveill 6:19218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, Asmus Leth , and Hjorth Frederik. 2020. “Willingness to Distance in the COVID‐19.” OSF Preprints. Available at 〈https://osf.io/xpwg2/〉 [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, G , McPhetres J, Bago B, and Rand DG. 2020. “Attitudes About COVID‐19 in Canada, the UK, and the USA: A Novel Test of Political Polarization and Motivated Reasoning.” PsyArXiv Preprints. Available at 〈https://psyarxiv.com/zhjkp/〉 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati, Gabriele , Pietrantoni Luca, and Zani Bruna. 2011. “Compliance with Recommendations for Pandemic Influenza H1N1 2009: The Role of Trust and Personal Beliefs.” Health Education Research 26:761–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Sandra Crouse , Kumar Supriya, Freimuth Vicki S., Kidwell Kelley, and Musa Donald. 2009. “Public Willingness to Take a Vaccine or Drug Under Emergency Use Authorization during the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic.” Biosecurity and Bioterrorism: Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 7:275–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahn, Wendy. 1993. “The Role of Partisan Stereotypes in Information Processing about Political Candidates.” American Journal of Political Science 37:427–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbun, Brian C. 2009. “It Takes All Types: Social Psychology, Trust, and the International Relations Paradigm in Our Minds.” International Theory 1:345–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbun, Brian C. , Kertzer Joshua D., Reifler Jason, Goren Paul, and Scotto Thomas J.. 2016. “Taking Foreign Policy Personally: Personal Values and Foreign Policy Attitudes.” International Studies Quarterly 60:124–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lau Richard R., and Redlawsk David P.. 2001. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making.” American Journal of Political Science 45:951–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rothgerber, Hank , Wilson Thomas, Whaley Davis, Rosenfeld Daniel L., Humphrey Michael, Moore Allie, and Bihl Allison. 2020. “Politicizing the Covid‐19 Pandemic: Ideological Differences in Adherence to Social Distancing.” PsyArXiv. Pre‐print. Available at 〈https://psyarxiv.com/k23cv/〉 [Google Scholar]

- Shino, Enrijeta , and Binder Michael, 2020. “Defying the Rally During COVID‐19 Pandemic: A Regression Discontinuity Approach.” Social Science Quarterly. 101(5):1979–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegrist, Michael , and Zingg Alexandra. 2014. “The Role of Public Trust During Pandemics: Implications for Crisis Communication.” European Psychologist 19:23. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Herbert A. 1955. “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 69:99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Anthony D. 1998. Nationalism and Modernism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sniderman, Paul M , Brody Richard A., and Tetlock Phillip E.. 1993. Reasoning and Choice: Explorations in Political Psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, Amos , and Kahneman Daniel. 1974. “Judgment Under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185:1124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udow‐Phillips, Marianne , and Lantz Paula M.. 2020. “Trust in Public Health Is Essential Amid the COVID‐19 Pandemic.” Journal of Hospital Medicine 15.7:431–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel, Jay J. , Baicker Katherine, Boggio Paulo S., Capraro Valerio, Cichocka Aleksandra, Cikara Mina, Crockett Molly J. et al. 2020. “Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID‐19 Pandemic Response.” Nature Human Behaviour 4:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavreck, L. and Rivers D.. 2008. “The 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Study.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties. 18: 355–366. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, Bertjan , and Zaslove Andrej. 2017. “Populism and Foreign Policy.” In Rovira Kaltwasser Cristóbal, Taggart Paul, Espejo Paulina Ochoa, and Ostiguy Pierre, Eds., The Oxford Handbook of Populism. Available at https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198803560.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198803560-e-15. [Google Scholar]

- Von Borzyskowski, Inken , and Vabulas Felicity. 2019. “Hello, Goodbye: When do States Withdraw from International Organizations?” The Review of International Organizations 14:335–66. [Google Scholar]

- Voeten, Erik. 2020. “Populism and Backlashes Against International Courts.” Perspectives on Politics 18:407–22. [Google Scholar]

- Yum, Seungil. 2020. “Social Network Analysis for Coronavirus (COVID‐19) in the United States.” Social Science Quarterly. 101(4):1642–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkopf, Eugene R. 1990. Faces of Internationalism: Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zaller, John R. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table A1. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Competence: Management of Covid and Accurate Information

Table A2. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Integrity: Independence of Political Agents and Unbiased Information

Table A3. Following Health Behavior Guidelines as a Function of Trust in the Competence and Integrity of the World Health Organization

Table A4. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Competence‐GOLOGIT2

Table A5. Trust in the World Health Organization‐Integrity‐GOLOGIT2

Table A6. Following Health Behavior Guidelines as a Function of Trust in the WHO‐GOLOGIT2