Abstract

Background and Objectives

This study investigated the relationship between childhood friendships and cognitive functioning, as assessed with cognitive status and decline among adults aged 45 and older in China. We also examined the mediating effect of adult social disconnectedness and adult loneliness for this relationship.

Research Design and Methods

This study was based on 3 waves of data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS; 2011, 2013, 2015; N = 13,959). Cognitive functioning was assessed with episodic memory. Childhood friendship measures were taken from the 2014 life history module of the CHARLS. Two dimensions of adult social isolation, loneliness and social disconnectedness, were included as mediators. Latent growth curve modeling was utilized to test the associations between childhood friendships, adult social isolation, and cognitive functioning.

Results

Adverse childhood friendship experiences were found to be significantly associated with both lower initial cognitive status and the rate of decline in cognitive functioning. Our findings indicated that adult loneliness and social disconnectedness partly mediated the link between childhood friendship experiences and the initial level of cognitive functioning, but not cognitive decline later in life.

Discussion and Implications

The findings emphasized the enduring importance of childhood friendships for cognitive functioning later in life. Interventions that focus on improving social participation through fostering friendships in childhood may have long-term benefits for cognition later in life.

Keywords: Brain health, China, Life-course model, Perceived social isolation, Social participation

Early life conditions account for differences in health trajectories in later life, as disadvantages in childhood often lead to disadvantaged outcomes in adulthood (Kobayashi et al., 2017; Ritchie et al., 2011; Z. Zhang, Liu, & Choi, 2019; Z. Zhang, Liu, Li, & Xu, 2018). Research showed that children who lack friends and who do not feel connected to their peers are at greater risk of poor adult health compared with children with stronger friendship bonds (Caspi, Harrington, Moffitt, Milne, & Poulton, 2006). This association was independent of other childhood factors that contribute to poor adult health (Caspi et al., 2006). Evidence also demonstrated that two dimensions of social isolation (loneliness and poor social integration, sometimes referred to as social disconnectedness) in adulthood were risk factors for cognitive functioning in middle and late adulthood (Cornwell & Waite, 2009a; Rafnsson, Orrell, D’Orsi, Hogervorst, & Steptoe, 2020). The relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive decline in later life has not been adequately explored and is not well-understood, especially in non-Western societies.

China represents a unique, evolving context for studying the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and later-life cognitive decline, a risk factor for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD). During the 20th century, China experienced widespread famine and poverty, wars, and political upheaval, negatively impacting child and adolescent development. During the 21st century, China witnessed phenomenal economic growth, dramatic rural-to-urban migration, and historically low fertility, along with a weakening of social norms surrounding the meaning and application of intergenerational support (Du, 2013). Meanwhile, cognitive functioning became a critical public health concern related to China’s large and rapidly aging population. The number of people aged 65 and older in China was expected to reach 366 million by 2050 (National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, 2018). Around 12.7% of older Chinese adults had MCI (Nie et al., 2011), and the number of older Chinese adults with ADRDs is expected to reach 10 million by 2050 (Y. Zhang et al., 2012).

This study aimed to investigate the association between childhood friendship experiences and cognition among middle-aged and older adults in China. We also examined the mediating role of two dimensions of adult social isolation, loneliness and poor social integration, as possible explanations for this association. We analyzed nationally representative panel data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) to address the following research questions: (i) Is there a relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning among Chinese adults? and (ii) Does adult loneliness and poor social integration mediate the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning?

Two Dimensions of Social Isolation and Cognitive Functioning

Social isolation is defined as “a state in which the individual lacks a sense of belonging socially, lacks engagement with others, has a minimal number of social contacts and they are deficient in fulfilling and quality relationships” (Nicholson, 2009, p. 1346). This definition highlighted the subjective and objective dimensions of social isolation. These two dimensions are conceptualized as poor social integration, or social disconnectedness and loneliness (Cornwell & Waite, 2009b). Social disconnectedness is an objective state characterized by a restricted social network and social inactivity with low participation and engagement (Cornwell & Waite, 2009b). Loneliness is a subjective assessment defined as “a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010, p. 218). The prevalence of loneliness is likely to vary in a curvilinear fashion over the life course, with loneliness being highest in childhood, declining in middle age, and increasing again in later life. The effects of loneliness are argued to be persistent and cumulative over time, such that chronic loneliness yields long-term health risks (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Loneliness is prevalent among older adults in China, with estimates as high as 50% for persons living in households without children or grandchildren and as high as 78% among those living in rural areas (G. Wang et al., 2011). Among the older Chinese population, estimates showed that loneliness increased from 29.7% in 1995 to 38.7% in 2011 (Yan, Yang, Wang, Zhao, & Yu, 2014).

Loneliness and social disconnectedness are associated with specific dimensions of cognitive functioning (Poey, Burr, & Roberts, 2017) and incident dementia (Rafnsson et al., 2020), including lower baseline levels of cognitive functioning and faster cognitive decline (DiNapoli, Wu, & Scogin, 2014). Loneliness and social disconnectedness are associated with an increased risk of poor memory (Shankar, Hamer, McMunn, & Steptoe, 2013) and lower levels of executive function (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Zhong, Chen, Tu, and Conwell (2017) found a significant correlation between loneliness and cognitive function among Chinese older adults.

Childhood Friendship Experiences and Cognitive Functioning

Early life experiences are shown to have long-term relationships with later cognitive functioning (Chapko, McCormack, Black, Staff, & Murray, 2017). Experiences during early developmental stages often have long-lasting associations with a person’s social opportunities and developmental resources that cascade throughout the life course. Friendships and other peer relationships in childhood are significantly related to various aspects of social and cognitive development, and general well-being. These included intellectual ability, coping and adjustment capacities, delinquency, criminality, physical activity, substance abuse, sleep, suicide, sexual behavior, and mental health (Andrews, Hanish, & Santos, 2017; Hamilton, Warner, & Schwarzer, 2017; Li, Kawachi, Buxton, Haneuse, & Onnela, 2019; Light, Mills, Rusby, & Westling, 2019).

Furthermore, the child development literature showed that limited friendship experiences during childhood are linked to loneliness (Spithoven, Bastin, Bijttebier, & Goossens, 2018), as well as educational achievement (Lessard & Juvonen, 2018), factors known to be related to cognitive decline in later life. Given that social interaction with friends promotes cognitive development during childhood (Cooc & Kim, 2017), adverse childhood friendship experiences during this sensitive period may have lasting consequences for cognitive functioning throughout the life course. We argue, as others have, that the negative effects of social isolation, operationalized as loneliness, cumulate over the life course (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009) and that adverse friendship circumstances experienced during childhood are associated with trajectories of cognitive functioning throughout middle and late adulthood.

What deserves additional consideration is whether and how childhood friendship circumstances are related to the development and the establishment of social relationships and loneliness in adulthood (Sherman, De Vries, & Lansford, 2000). Early friendships provided children with opportunities to learn and practice their social skills, which lays a foundation for their later social relationships. Lack of adequate friendship experiences during childhood may have trapped some individuals in a vicious cycle of loneliness, marginalization, and frustration, which may lead to further defensiveness and maladaptive interactions with others.

Considering that adult social isolation, especially the loneliness dimension, is associated with later-life cognitive functioning and childhood friendship experiences are associated with social isolation at subsequent stages of the life course (Lempinen, Junttila, & Sourander, 2018), we propose that loneliness and social disconnectedness in adulthood are mechanisms through which childhood friendship experiences are related to adult cognitive functioning in later life. Thus, these two dimensions of adult social isolation are viewed as a continuation of poor childhood friendship experiences at the early stages of the life course.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

This study makes three contributions to our understanding of the association between childhood friendship experiences and cognition in later life among older Chinese adults. First, this study is among the first to investigate the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and later cognitive functioning. Second, this study examines the mediating role of adult loneliness and social disconnectedness as two mechanisms through which childhood friendships are associated with later-life cognitive functioning among Chinese adults. Third, using nationally representative CHARLS data, this study provides new evidence about early-life friendships and later-life cognitive functioning in China, the country with the largest older population embedded in a unique historical, cultural, and social context. We hypothesize that (i) compared to Chinese adults who experienced more favorable friendship experiences earlier in life, those who had more adverse friendship experiences as children would experience worse cognitive functioning in later life, and (ii) adult loneliness and social disconnectedness in later life would mediate the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning among older Chinese adults.

Methods

Data Source

This study was based on three waves of data taken from the CHARLS (2011, 2013, 2015), a nationally representative panel survey (the panel survey includes a sample of respondents observed across multiple time points) conducted by the China Centre for Economic Research of Peking University. The CHARLS recruited eligible respondents aged 45 and older based on a multistage probability sampling method and conducted follow-up interviews every 2 years. The CHARLS collected information on a wide range of topics, including health, family structure, living arrangements, social networks, labor force status, pensions, and economic standing. Furthermore, the 2014 CHARLS life history module collected information about respondents’ childhood conditions, including childhood friendships, family relationships, neighborhood quality, education, health, and socioeconomic status.

The number of CHARLS respondents in the 2011, 2013, and 2015 waves was 17,708, 18,612, and 21,097, respectively. A total of 20,543 respondents from the first two waves were given the life history questionnaire. The study sample was limited to 17,708 CHARLS respondents who completed the baseline questionnaire in 2011. We excluded respondents with missing information on cognitive functioning at baseline (n = 3,376) and those below age 45 (n = 371). We excluded two respondents who had missing information on age. The final study sample included 13,959 respondents.

Measures

Cognitive Functioning

Respondents’ cognitive functioning was assessed with episodic memory, which is thought to be effective in capturing respondents’ cognitive status and “highly sensitive to brain changes in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease” (Weir, Lay, & Langa, 2014). Episodic memory was assessed by immediate recall and delayed recall (several minutes later) of 10 simple Chinese nouns. Estimates of respondents’ episodic memory ability were obtained by summing scores for the immediate and delayed recall items (range = 0–20). Higher scores indicated better cognitive functioning.

Childhood Friendship Experiences

From the life history module, three items were used to assess respondents’ friendship circumstances before the age of 17. The first two measures captured (i) frequency of loneliness due to lack of friends and (ii) frequency of having a group of friends, originally assessed on a four-point Likert scale, which were recoded into a dichotomous measure indicating social isolation from friends (i.e., frequency of loneliness: 0 = never or not very often, 1 = sometimes or often; frequency of having a group of friends: 0 = sometimes or often; 1 = never or not very). An additional measure assessed (iii) whether the respondent had a good friend (0 = yes; 1 = no). The first two items above were dichotomized to be consistent with the item on whether the respondent had a good friend. Responses to the three items were then combined to create a summative index of childhood friendship characteristics (range = 0–3), with higher scores indicating poorer childhood friendship experiences. No other measures of childhood friendship were available.

Adult Social Disconnectedness and Loneliness

For adult social disconnectedness, respondents were asked at each wave to indicate whether they had participated in any of six activities in the past month (1 = yes; 0 = no). These activities included (i) interacted with friends, (ii) played ma-Jong, chess, cards, or went to a community club, (iii) provided help to family, friends, or neighbors who did not live with respondent, (iv) went to a sport, social, or other kind of club, (v) engaged in voluntary or charity work, and (vi) attended an educational or training course. We reverse-coded the responses and created an index measure of social disconnectedness by summing the six dichotomous measures, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social disconnectedness (range = 0–6). An average activity score across the three waves was generated and used to capture the level of social disconnectedness. Respondents were also asked to indicate their frequency of loneliness during the last week at each wave (1 = most or all of the time [5–7 days], 2 = occasionally or a moderate amount of the time [3–4 days], 3 = some or a little of the time [1–2 days], and 4 = rarely or none of the time [<1 day]). The item responses were reverse-coded so that higher scores indicate more frequent feelings of loneliness (range = 1–4). Similar to social disconnectedness, an average score of loneliness across the three waves was used in the analyses. No other measures of loneliness were available.

Covariates

The analysis included measures of adulthood characteristics and childhood characteristics. Adult characteristics measured at baseline (2011) included age (years), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), and marital status (1 = married, 0 = not married). Education was assessed with a three-category measure (1 = illiterate, 2 = less than high school, 3 = high school and above). Official Chinese hukou registration status was recoded as a binary variable (1 = agriculture, 0 = nonagriculture). Hukou status conferred housing, education, and health benefits to nonagriculture registrants (urban) that are not available to agricultural registrants (rural). Respondents’ annual household income was assessed in the Chinese yuan (transformed by the natural log). Respondents’ current occupational and employment status were combined into one variable (1 = not currently working, 2 = agricultural job, and 3 = nonagricultural job). Measures of physical activity assessed as engaging in any vigorous physical activity or exercise at least 10 minutes during a usual week (1 = yes, 0 = no). Smoking history (1 = ever smoked, 0 = no), history of stroke (1 = yes, 0 = no), and obesity (1 = body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2, 0 = no) were also included.

Childhood socioeconomic status was assessed with a single item, “Before age 17, how did your family financial status compare with that of the average family in the same community/village?,” which was coded on a five-point Likert scale (1 = a lot better off than them, 2 = somewhat better off than them, 3 = same as them, 4 = somewhat worse off than them, 5 = a lot worse off than them). Childhood self-rated health was measured with “How do you rate your health before age 15 compared to your peers?” (1 = much healthier, 2 = somewhat healthier, 3 = about average, 4 = somewhat less healthy, 5 = much less healthy). Childhood hukou registration status was assessed as respondents’ first hukou registration status (1 = agricultural, 0 = nonagricultural). Education levels of each parent were assessed based on a single question about literacy (1 = illiterate, 0 = literate).

Analytic Strategy

We first examined the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. Next, the research questions were addressed using latent growth curve modeling (LGCM), where trajectories of cognitive functioning were captured using two latent growth factors: the intercept (I) factor, reflecting the level of cognitive status at baseline, and the slope (S) factor, reflecting the rate of change over the three waves of the observation period. LGCM provided average estimates of intercept and slope factors as fixed effects. We produced variance estimates of the respective latent growth factors as random effects. We addressed our research questions in two steps. First, we examined the direct association between the childhood friendship experience and cognitive functioning, controlling for a set of covariates. Second, we tested two adult social isolation pathways (i.e., social disconnectedness and loneliness) through which childhood friendship experiences were hypothesized to be associated with later-life cognitive functioning. We used the following indices to assess goodness of model fit: the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI) higher than .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) lower than .07, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) lower than .05. A chi-square test (χ 2) is provided, but this test is not optimal given the large sample size (Steiger, 2007).

We first estimated an unconditional model, where cognitive functioning trajectory based on the two-factor LGCM provided acceptable fit to the data [χ 2(1) = 78.20, TLI = .96, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .02; model estimates available upon request]. We then estimated a conditional model by introducing childhood friendship experiences along with the full set of covariates (Model 1). To test the mediation hypothesis, we added adult social disconnectedness and loneliness to the previous model (Model 2).

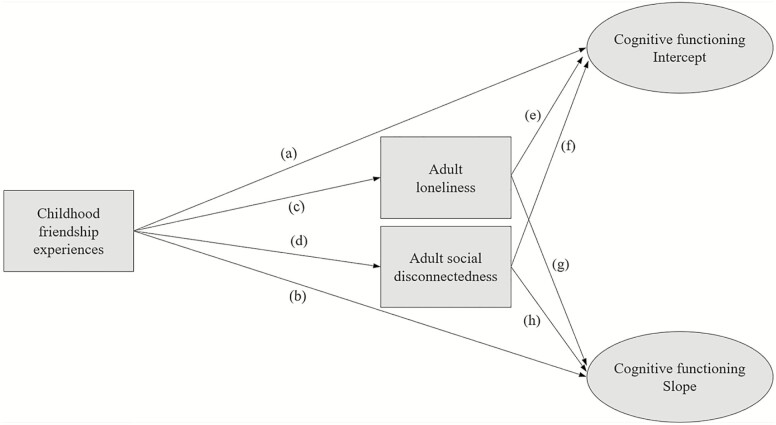

Missing information was observed across the study variables. Variables with the most missing values included father’s education (22.6%) and mother’s education (19.5%). Missing data were handled using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method, allowing model parameters to be estimated based on all available data, providing robust estimates when the data are missing at random and assuming multivariate normality. All analyses were conducted with Mplus 8.1, using 1,000 bootstrap samples (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). A simplified conceptual model with key study variables is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of childhood friendship experiences, adult social disconnectedness and loneliness, and cognitive decline without covariates. Paths a and b represent the direct effect of childhood friendship experiences on the level (i.e., intercept) and rate of change (i.e., slope) of cognitive functioning trajectory, respectively. Indirect effects linking childhood friendship experiences on the level of cognitive functioning via adult loneliness and adult social disconnectedness are indicated by paths c × e and d × f, respectively. Indirect effects linking childhood friendship experiences on the change rate of cognitive decline via adult loneliness and adult social disconnectedness are indicated by paths c × g and d × h, respectively.

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Study sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. The average cognitive functioning scores (range = 0–20) in 2011, 2013, and 2015 were 7.08, 7.07, and 6.53 (range = 0–20), respectively, indicating a downward trend over time. The index of childhood friendship experiences was low (range = 0–3), as indicated by an average score of less than one (0.71). On average, respondents reported a low level of loneliness in adulthood (1.50; range = 1–4) and participated in approximately three social activities (3.25; range = 0–6).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of the CHARLS Sample

| Variables | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive functioning (0–20) | ||

| 2011 | 7.08 | 3.45 |

| 2013 | 7.07 | 3.57 |

| 2015 | 6.53 | 3.65 |

| Childhood friendship experiences (0–3) | 0.71 | 0.87 |

| Adult social disconnectedness (0–6) | 3.25 | 0.71 |

| Adult loneliness (1–4) | 1.50 | 0.74 |

| Age (45–100) | 58.73 | 9.43 |

| Female (%) | 51.77 | |

| Married (%) | 83.55 | |

| Education (%) | ||

| Illiterate | 25.84 | |

| Less than high school | 61.08 | |

| High school and above | 13.08 | |

| Current agricultural hukou status (%) | 77.08 | |

| Income (yuan, 0–2,160,000) | 3,985.83 | 22,248.44 |

| Occupation (%) | ||

| Nonworking | 48.03 | |

| Agricultural job | 20.65 | |

| Nonagricultural job | 31.32 | |

| Vigorous physical activity (%) | 14.74 | |

| Ever smoked (%) | 39.82 | |

| Ever had stroke (%) | 2.61 | |

| Obese (BMI > 30) (%) | 5.04 | |

| Childhood SES (1–5, %) | 3.54 | 0.97 |

| A lot better off than them | 1.00 | |

| Somewhat better off than them | 7.96 | |

| Same as them | 51.34 | |

| Somewhat worse off than them | 15.86 | |

| A lot worse off than them | 23.84 | |

| Childhood health status (1–5, %) | 2.66 | 1.01 |

| Much healthier | 16.61 | |

| Somewhat healthier | 18.96 | |

| About average | 51.67 | |

| Somewhat less healthy | 7.84 | |

| Much less healthy | 4.92 | |

| Childhood agricultural hukou status (%) | 81.43 | |

| Father illiterate (%) | 59.71 | |

| Mother illiterate (%) | 89.85 |

Notes. Sample N = 13,959. BMI = body mass index; CHARLS = China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study; SES = socioeconomic status.

Association Between Childhood Friendship Experiences and Cognitive Functioning

The LGCM results for the direct association between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning are presented in Model 1, Table 2. Fit indices indicated the model fit the data well: χ 2 (20) = 126.30, TLI = .97, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, and SRMR = .00. The results showed that childhood friendships were significantly related to cognitive functioning at baseline, as well as the rate of change in cognitive functioning. That is, more adverse childhood friendship experiences were associated with a lower level of cognitive functioning in adulthood (path a: β = −0.155, p < .001) at baseline, net of other factors considered in the model. Respondents with a higher degree of adverse childhood friendship experiences showed a faster decline in their cognitive functioning in adulthood (path b: β = −0.053, p = .012).

Table 2.

Latent Growth Curve Model on Childhood Friendship Experiences, Adult Social Disconnectedness and Loneliness, and Cognitive Functioning

| Model 1: Direct effect | Model 2: Indirect effect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Slope | Intercept | Slope | |||||

| Variable | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE | β | SE |

| Childhood friendship | −0.155*** | .030 | −0.053* | .021 | −0.104*** | .030 | −0.047* | .021 |

| Adult social disconnectedness | −0.517*** | .036 | 0.024 | .025 | ||||

| Adult loneliness | −0.197*** | .036 | −0.042 | .024 | ||||

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | −0.075*** | .003 | −0.017*** | .002 | −0.071*** | .003 | −0.017*** | .002 |

| Female | 0.212** | .073 | 0.041 | .047 | 0.222** | .072 | 0.050 | .047 |

| Married | 0.201** | .067 | 0.097* | .049 | 0.157* | .069 | 0.077 | .050 |

| Education: Less than high schoola | 1.337*** | .061 | 0.208*** | .044 | 1.264*** | .061 | 0.208*** | .044 |

| Education: High school and abovea | 2.504*** | .099 | 0.295*** | .070 | 2.343*** | .099 | 0.293*** | .071 |

| Income-logged | 0.054 | .029 | 0.015 | .019 | 0.048 | .029 | 0.014 | .019 |

| Occupation: Nonworkingb | 0.055 | .068 | −0.024 | .046 | 0.064 | .068 | −0.019 | .046 |

| Occupation: Agricultural jobb | 0.160 | .090 | −0.041 | .061 | 0.162 | .090 | −0.042 | .061 |

| Current hukou status | −0.566*** | .142 | −0.029 | .092 | −0.501*** | .140 | −0.025 | .091 |

| Physical activity | 0.022 | .068 | −0.028 | .049 | 0.011 | .068 | −0.026 | .049 |

| Ever smoked | 0.101 | .069 | −0.143*** | .044 | 0.074 | .068 | −0.138** | .044 |

| Ever had stroke | −0.399* | .159 | −0.203 | .112 | −0.304 | .157 | −0.204 | .112 |

| Obese (BMI > 30) | 0.048 | .128 | 0.076 | .082 | −0.041 | .126 | 0.075 | .082 |

| Childhood SES | 0.004 | .030 | −0.023 | .020 | 0.018 | .030 | −0.021 | .020 |

| Childhood self-rated health | −0.119*** | .028 | −0.005 | .017 | −0.097*** | .028 | −0.004 | .017 |

| Childhood hukou status | −0.556*** | .146 | −0.024 | .095 | −0.491*** | .143 | −0.030 | .095 |

| Father illiterate | −0.276*** | .061 | −0.008 | .041 | −0.233*** | .061 | −0.009 | .041 |

| Mother illiterate | −0.166 | .101 | −0.121 | .064 | −0.150 | .100 | −0.122 | .064 |

| Constant | 11.63*** | .29 | 0.78*** | .19 | 13.15*** | .31 | 0.77*** | .20 |

| Variance | 2.83*** | .18 | 0.24* | .10 | 2.67*** | .18 | 0.23* | .10 |

| Fit indices | ||||||||

| χ 2(df) | 126.30 (20) | 125.78 (22) | ||||||

| TLI | .97 | .97 | ||||||

| CFI | .99 | .99 | ||||||

| RMSEA | .02 | .02 | ||||||

| SRMR | .00 | .00 |

Notes. Sample N = 13,959. BMI = body mass index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SES = socioeconomic status; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index.

aReference category = illiterate.

bReference category = not currently working.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The Mediating Effects of Adult Social Disconnectedness and Loneliness

Next, we examined the mediating role of adult social disconnectedness and loneliness for the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning (Model 2, Table 2). The two mediational pathways were tested simultaneously: adulthood loneliness and social disconnectedness. Fit indices indicated the model fit the data well: χ 2 (22) = 125.78, TLI = .97, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .02, and SRMR = .00. Childhood friendship was significantly associated with higher levels of adult loneliness (path c; β = 0.046, p < .001) and adult social disconnectedness (path d; β = 0.080, p < .001; paths c and d not shown in table). Both adult loneliness (path e; β = −0.197, p < .001) and adult social disconnectedness (path f; β = −0.517, p < .001) were significantly associated with worse cognitive functioning at baseline. Adult loneliness (path g; β = −0.042, p = .086) and adult social disconnectedness (path h; β = 0.024, p = .328) were not associated with faster decline in cognitive functioning. Taken together, the findings indicated that a higher level of adult social isolation mediated the link between childhood friendship experiences and a compromised level of cognitive functioning in adulthood, but the evidence for a mediating role of adult social disconnectedness and loneliness for cognitive decline was limited. The association between childhood friendship and cognitive functioning at baseline was partially mediated through both adult loneliness (path c × e; β = −0.009, p < .001) and adult social disconnectedness (path d × f; β = −0.041, p < .001. However, the pathway linking childhood friendship and cognitive decline through adult loneliness (path c × g; β = −0.002, p = .108) and social disconnectedness was not significant (path d × h; β = 0.002, p = .332).

We present the total, direct, and indirect effects linking childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning in Table 3 (results are derived from those presented in Table 2). The total association of childhood friendship experiences for the level of cognitive functioning was −0.154 (p < .001), and adulthood social disconnectedness accounted for approximately 82% (= −0.041/−0.050) of the pathway. The total association for the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive decline was sizable (β = −.047, p = .024), and no significant indirect association was found for the association between childhood friendships and the rate of change in cognitive functioning.

Table 3.

Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects of Childhood Friendship Experiences on Cognitive Functioning in Later Life

| Intercept | Slope | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | β | SE | β | SE |

| Direct effect | −0.104*** | .030 | −0.047* | .021 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Via adult loneliness | −0.009*** | .002 | −0.002 | .001 |

| Via adult social disconnectedness | −0.041*** | .004 | 0.002 | .002 |

| Total indirect | −0.050*** | .005 | 0.000 | .002 |

| Total effect | −0.154*** | .030 | −0.047* | .021 |

Notes. Sample N = 13,959. Estimates based on Model 2.

*p < .05. ***p < .001.

Discussion

Although the scholarly literature on childhood conditions and cognitive outcomes is growing (DiNapoli et al., 2014; Z. Zhang et al., 2018), earlier studies did not examine the role of childhood friendship experiences. Given that friendship conditions during childhood are critical for cognitive and social relationship development throughout the life course, we examined the association between childhood friendships and adulthood cognitive functioning among Chinese adults aged 45 and older, and we also tested the mediating roles of adult loneliness and social disconnectedness.

Our findings indicated that respondents with higher levels of adverse childhood friendship experiences had a lower level of cognitive functioning and faster cognitive decline in later life, supporting our first hypothesis. As discussed earlier, an individual’s health trajectory is to some extent forged early in life (Ritchie et al., 2011). Thus, negative events experienced in childhood, such as experiencing fewer positive friendship experiences, may substantially alter an individual’s cognitive functioning trajectory throughout the life course. One explanation for such “long arm of childhood” relationships is that resources and opportunities for personal development were shaped in part by an individual’s early life conditions and experiences (Li et al., 2019; Light et al., 2019). Our study underscored the thesis that childhood is a sensitive period for cognitive development that has far-reaching consequences for cognitive functioning in middle and late adulthood in China. The findings were also consistent with the growing literature that shows childhood conditions had an enduring association with cognition in later adulthood (Chapko et al., 2017; Z. Zhang et al., 2018, 2019).

The second hypothesis that adult loneliness and social disconnectedness would mediate the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning in later life was partially supported. Our results demonstrated that higher levels of adult loneliness and social disconnectedness were mechanisms through which childhood friendship experiences were associated with levels of cognitive functioning. This suggested that the negative effects of poor childhood friendship experiences cascaded over the life course, where the effects of these experiences were related to adult social disconnectedness and loneliness in later life, resulting in an erosion of cognitive functioning over time (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Previous prospective studies that followed children into adulthood demonstrated that early negative experiences, like a chronic disease, had a persistent and cumulative detrimental association with adult health conditions (e.g., health, coping strategies; Caspi et al., 2006; Sherman et al., 2000). Moreover, the negative association between adult social disconnectedness and loneliness and cognitive functioning has been widely demonstrated in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (DiNapoli et al., 2014; Rafnsson et al., 2020; Seeman et al., 2011; Shankar et al., 2013). Our findings suggested that adverse childhood friendship experiences may lead to a lack of opportunities for individuals to experience cognitive stimulation through communication and social interaction with others, thereby leading to increased social isolation in adulthood, subsequently undermining cognitive functioning in later life.

Evidence for the mediating role of adult social disconnectedness and loneliness for the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and rate of cognitive decline was limited in this study. Consistent with a recent study, we found that loneliness in later life was not associated with faster cognitive decline among older Chinese adults (H. Wang, Lee, Hunter, Fleming, & Brayne, 2019). This finding was possibly attributable to the use of a single indicator of loneliness (a limitation of the CHARLS data), and future studies should test the mediating role of loneliness using a more comprehensive measure (Wang et al., 2019). Given that childhood friendship experiences had consequences for various dimensions of one’s well-being in adulthood, future studies should also explore whether factors such as education, health behaviors, and health in adulthood moderate the link between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive decline.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our findings indicated that Chinese adults who had limited and less fulfilling childhood friendship experiences had lower levels of cognitive functioning and more rapid cognitive decline, which have implications for designing intervention programs that alleviate the harmful effects of negative childhood friendship experiences. Community-based intervention programs should aim to promote children’s social engagement and reduce structural barriers to friendship opportunities by providing recreation and leisure opportunities designed around social and cognitively stimulating activities (e.g., interaction with friends, teamwork, club activities). Our findings also suggested that adverse childhood friendship experiences may be a risk factor for cognitive decline in later life; if the finding is corroborated in future studies, childhood conditions, including family social isolation, may be considered as a screening tool for identifying the risk of cognitive decline. Intervention programs, such as strengthening social engagement and maintaining a wide range of emotionally supportive relationships, may also help reduce the risk of cognitive decline. Professionals, such as social workers, involved in children’s social welfare should be aware of the long-term negative effects of children’s relationship with their peers.

Our findings indicated that adult loneliness and social disconnectedness partly mediated the association between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning later in life. As such, intervention efforts directed at reducing multiple dimensions of adult social isolation may help to partly recover cognitive deficits associated with adverse childhood friendship experiences earlier in life (Pitkala, Routasalo, Kautiainen, Sintonen, & Tilvis, 2011). Review studies suggested that group activities with educational and supportive inputs may be a promising avenue for reducing social disconnectedness during adulthood (Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2011). Policymakers and community organizations should consider implementing programs designed to encourage social participation among older adults.

In summary, our findings underscore the importance of taking a life-course approach in promoting population health. Given that childhood friendship experiences and adult loneliness and social disconnectedness were related to cognitive functioning in later life, the goal of intervention programs and public policies should be to promote participation in various types of social, leisure, and intellectual activities from an early age, and to inform adults that active social participation has a potential protective effect on cognitive functioning. These findings serve as a basis for creating public health programs aimed at reducing isolation across the life course to promote healthy cognitive aging.

Limitations

The limitations of the study are acknowledged. First, the childhood variables were measured based on retrospective self-reports, which may have led to recall bias, suggesting caution is needed in the interpretation of the estimates for the association between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning. Also, loneliness in later life may bias retrospective reports of childhood experiences, implying possible reciprocal causation. Second, the association between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning may vary at different developmental stages, spanning early childhood through adolescence. Pre-adolescents and adolescents, for example, are likely to experience friendship deficits differently and may yield different consequences for later-life cognitive functioning. The CHARLS measures of childhood friendship conflated these potential age group differences. More research is needed to examine whether social relationships experienced at different developmental stages yield different cognitive outcomes later in the life course. Third, adult social disconnectedness was measured by asking survey respondents how many of six activities they participated in during the last month. It is likely that some respondents participated in a limited number of activities, but frequently participated in each activity, while other respondents may have participated in a variety of activities, but participated in each activity less frequently. Future studies should take into account the frequency and intensity of older adults’ participation in social activities. Fourth, although we focused on episodic memory in this study, future research should examine other domains of cognition, including a more comprehensive measure. Finally, we suggest additional qualitative and quantitative measures are needed to capture more comprehensive information about childhood friendships, such as the negative consequences of peer relationships.

Conclusions

Childhood friendship experiences are considered a modifiable risk factor for cognitive health. This novel study extended our understanding of the enduring relationships between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning later in life. This study contributed to the scientific literature on life-course models of health by (i) combining a child development framework with frameworks from gerontology and aging studies, (ii) examining the direct and indirect relationships between early-life conditions, adult social disconnectedness and adult loneliness, and cognitive functioning, and (iii) performing a longitudinal analysis of the central research questions with national data from China. In future research, investigators should examine whether the relationship between childhood friendship experiences and cognitive functioning among Chinese older adults varied by other factors, such as gender, age group, birth cohort, and rural versus urban residence.

Funding

This research was supported in part by a grant awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD042849). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Andrews, N. C. Z., Hanish, L. D., & Santos, C. E. (2017). Reciprocal associations between delinquent behavior and social network position during middle school. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(9), 1918–1932. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0643-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi, A., Harrington, H., Moffitt, T. E., Milne, B. J., & Poulton, R. (2006). Socially isolated children 20 years later: Risk of cardiovascular disease. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160(8), 805–811. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapko, D., McCormack, R., Black, C., Staff, R., & Murray, A. (2017). Life-course determinants of cognitive reserve (CR) in cognitive aging and dementia: A systematic literature review. Aging and Mental Health, 22, 921–932. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1348471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooc, N., & Kim, J. S. (2017). Peer influence on children’s reading skills: A social network analysis of elementary school classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109, 727–740. doi: 10.1037/edu0000166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009a). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650905000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009b). Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(Suppl. 1), i38–i46. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli, E. A., Wu, B., & Scogin, F. (2014). Social isolation and cognitive function in Appalachian older adults. Research on Aging, 36(2), 161–179. doi: 10.1177/0164027512470704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, P. (2013). Intergenerational solidarity and old-age support for the social inclusion of elders in Mainland China: The changing roles of family and government. Ageing and Society, 33, 44–63. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X12000773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, K., Warner, L. M., & Schwarzer, R. (2017). The role of self-efficacy and friend support on adolescent vigorous physical activity. Health Education & Behavior, 44(1), 175–181. doi: 10.1177/1090198116648266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, L. C., Glymour, M. M., Kahn, K., Payne, C. F., Wagner, R. G., Montana, L.,…Berkman, L. F. (2017). Childhood deprivation and later-life cognitive function in a population-based study of older rural South Africans. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 190, 20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempinen, L., Junttila, N., & Sourander, A. (2018). Loneliness and friendships among eight-year-old children: Time-trends over a 24-year period. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 59(2), 171–179. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, L. M., & Juvonen, J. (2018). Losing and gaining friends: Does friendship instability compromise academic functioning in middle school? Journal of School Psychology, 69, 143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Kawachi, I., Buxton, O. M., Haneuse, S., & Onnela, J. P. (2019). Social network analysis of group position, popularity, and sleep behaviors among US adolescents. Social Science and Medicine, 232, 417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light, J. M., Mills, K. L., Rusby, J. C., & Westling, E. (2019). Friend selection and influence effects for first heavy drinking episode in adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 80(3), 349–357. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(3), 219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China . (2018). China Statistical Yearbook. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexeh.htm

- Nicholson, N. R., Jr. (2009). Social isolation in older adults: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(6), 1342–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie, H., Xu, Y., Liu, B., Zhang, Y., Lei, T., Hui, X.,…Wu, Y. (2011). The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment about elderly population in China: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(6), 558–563. doi: 10.1002/gps.2579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkala, K. H., Routasalo, P., Kautiainen, H., Sintonen, H., & Tilvis, R. S. (2011). Effects of socially stimulating group intervention on lonely, older people’s cognition: A randomized, controlled trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(7), 654–663. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181f7d8b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poey, J. L., Burr, J. A., & Roberts, J. S. (2017). Social connectedness, perceived isolation, and dementia: Does the social environment moderate the relationship between genetic risk and cognitive well-being? The Gerontologist, 57(6), 1031–1040. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafnsson, S. B., Orrell, M., D’Orsi, E., Hogervorst, E., & Steptoe, A. (2020). Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: Prospective findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(1), 114–124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, K., Jaussent, I., Stewart, R., Dupuy, A. M., Courtet, P., Malafosse, A., & Ancelin, M. L. (2011). Adverse childhood environment and late-life cognitive functioning. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(5), 503–510. doi: 10.1002/gps.2553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, T. E., Miller-Martinez, D. M., Stein Merkin, S., Lachman, M. E., Tun, P. A., & Karlamangla, A. S. (2011). Histories of social engagement and adult cognition: Midlife in the US study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 141–152. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, A., Hamer, M., McMunn, A., & Steptoe, A. (2013). Social isolation and loneliness: Relationships with cognitive function during 4 years of follow-up in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(2), 161–170. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827f09cd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, A. M., de Vries, B., & Lansford, J. E. (2000). Friendship in childhood and adulthood: Lessons across the life span. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 51(1), 31–51. doi: 10.2190/4QFV-D52D-TPYP-RLM6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spithoven, A. W. M., Bastin, M., Bijttebier, P., & Goossens, L. (2018). Lonely adolescents and their best friend: An examination of loneliness and friendship quality in best friendship dyads. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 3598–3605. doi: 10.1007/s10826-018-1183-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J. H. 2007. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 893–898. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Lee, C., Hunter, S., Fleming, J., & Brayne, C.; The CC75C Study Collaboration . (2019). Longitudinal analysis of the impact of loneliness on cognitive function over a 20-year follow-up. Aging and Mental Health. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1655704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G., Zhang, X., Wang, K., Li, Y., Shen, Q., Ge, X., & Hang, W. (2011). Loneliness among the rural older people in Anhui, China: Prevalence and associated factors. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(11), 1162–1168. doi: 10.1002/gps.2656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir, D., Lay, M., & Langa, K. (2014). Economic development and gender inequality in cognition: A comparison of China and India, and of SAGE and the HRS sister studies. Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 4, 114–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jeoa.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z., Yang, X., Wang, L., Zhao, Y., & Yu, L. (2014). Social change and birth cohort increase in loneliness among Chinese older adults: A cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1995–2011. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(11), 1773–1781. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y., Xu, Y., Nie, H., Lei, T., Wu, Y., Zhang, L., & Zhang, M. (2012). Prevalence of dementia and major dementia subtypes in the Chinese populations: A meta-analysis of dementia prevalence surveys, 1980–2010. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 19, 1333–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Liu, H., & Choi, S. W. (2019). Early-life socioeconomic status, adolescent cognitive ability, and cognition in late midlife: Evidence from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Social Science and Medicine. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Liu, J., Li, L., & Xu, H. (2018). The long arm of childhood in China: Early-life conditions and cognitive function among middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 30, 1319–1344. doi: 10.1177/0898264317715975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B. L., Chen, S. L., Tu, X., & Conwell, Y. (2017). Loneliness and cognitive function in older adults: Findings from the Chinese longitudinal healthy longevity survey. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(1), 120–128. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]