Abstract

Objective:

To determine the relationship between affective measures and cognition before and after non-cardiac surgery in older adults.

Methods:

Observational prospective cohort study in 103 surgical patients age ≥ 60 years old. All participants underwent cognitive testing, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression, and State Anxiety Inventory screening before and 6 weeks after surgery. Cognitive test scores were combined by factor analysis into 4 cognitive domains, whose mean was defined as the continuous cognitive index (CCI). Postoperative global cognitive change was defined by CCI change from before to after surgery, with negative CCI change indicating worsened postoperative global cognition and vice versa.

Results:

Lower global cognition before surgery was associated with greater baseline depression severity (Spearman’s r=−0.30, p=0.002) and baseline anxiety severity (Spearman’s r=−0.25, p=0.010), and these associations were similar following surgery (r=−0.36, p<0.001; r=−0.26, p=0.008, respectively). Neither baseline depression or anxiety severity, nor postoperative changes in depression or anxiety severity, were associated with pre- to postoperative global cognitive change.

Conclusions:

Greater depression and anxiety severity were each associated with poorer cognitive performance both before and after surgery in older adults. Yet, neither baseline depression or anxiety symptoms, nor postoperative change in these symptoms, were associated with postoperative cognitive change.

Keywords: Postoperative cognitive dysfunction, Depression, Anxiety, Older adults, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Preoperative depression and anxiety have been associated with cognitive deficits, increased mortality and other adverse events in older adults following cardiac surgery [1–3]. After non-cardiac surgery the relationship between cognition and either baseline or postoperative changes in depression/anxiety is less clear, although one recent study found an association between postoperative depression and postoperative subjective cognitive complaints in older patients following non-cardiac surgery [4]. Yet, the relationship between baseline affective symptoms and objectively measured cognitive deficits have yet to be evaluated extensively following non-cardiac surgery.

Since pre-operative/pre-existing depression has been associated with postoperative delirium [5, 6], which has been associated with cognitive decline following surgery, depression severity might also correlate with the degree of cognitive decline following surgery. In other words, older adults with more severe depression before surgery might be expected to have larger postoperative declines in cognition, just as they are at greater risk for postoperative delirium. Delirium is defined as a disturbance in attention and level of consciousness, accompanied by an additional disturbance in cognition (e.g., memory deficit, disorientation, language, visuospatial ability or perception) [7]. Postoperative delirium can also be viewed as a spectrum of varying severity, in which some patients have mild delirium signs/symptoms even if they do not meet threshold criteria for delirium as a dichotomous state (i.e. sub-syndromal delirium) [8]. Similarly, decline in cognition following surgery can be viewed as having a spectrum of severity [9, 10]. While precise cognitive testing deficit thresholds have been used to define postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) [11–22], and for the more recent term neurocognitive disorder postoperative [23], patients who do not meet these arbitrary testing thresholds often still have cognitive deficits associated with postoperative quality of life impairments [1, 19]. Thus, even postoperative cognitive deficits below specific thresholds are still highly relevant to patients [1, 19].

Many risk factors for decline in cognition following surgery such as baseline cognition and age are non-modifiable [9], yet depression and anxiety are treatable/modifiable [24–27]. Thus, here we examined the relationship between affective and cognitive function before and after surgery in older adults. In particular, we studied the relationship between depression/anxiety and cognition both before and 6 weeks after surgery in older non-cardiac surgery patients, as well as the relationship between pre- to post-operative changes in depression/anxiety and cognition.

METHODS

Overview

The Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease and Cognitive Outcomes After Perioperative Care (MADCO-PC) observational cohort study collected perioperative cognitive data, quality of life data, CSF samples, and EEG recordings from 140 older adults (≥60 years) undergoing elective non-cardiac, non-neurologic surgery at Duke University Medical Center [28]. Patients were excluded if they: 1) were age <60 years; 2) had a malignant hyperthermia history; 2) were unable to receive propofol and/or isoflurane due to contraindications; 3) were prisoners; 4) had a history of PE, DVT, or other bleeding or clotting disorder; or 5) were taking anticoagulants that precluded safe lumbar puncture [29]. There were no exclusions for preoperative cognitive or mood status.

MADCO-PC was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01993836). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation.

Cognitive Testing

Neurocognitive assessment was conducted preoperatively and 6 ± 3 weeks after surgery by staff trained by a board-certified neuropsychologist using our standard test battery [18, 20]. Scores from the Randt Short Story Memory Test, Modified Visual Reproduction Test from the Wechsler Memory Scale, Digit Span Test from the revised version of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-R), Digit Symbol Test from the WAIS-R, and Trail Making Test, Part B were combined using factor analysis with oblique rotation to produce 4 cognitive domain scores derived in a prior study [30]. These cognitive domains were (1) verbal memory, (2) abstraction/visuospatial orientation, (3) visual memory, and (4) attention/concentration; which together account for 84% of total test variability [30]. The cognitive domain scores were then averaged together to provide a representation of global cognition [31, 32], the continuous cognitive index (CCI). Postoperative CCI change identifies patients with an overall change in cognition across cognitive domains. The CCI is intended to provide a precise measure of overall cognitive function in an individual, and CCI change measures that individual’s cognitive function change over time; it is not intended to identify who has cognitive impairment (as a dichotomous trait) and who does not.

Depression and Anxiety Severity Measurement

Patients completed depression and anxiety self-assessments before and 6 ± 3 weeks after surgery using the following Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [33] and the State Anxiety Inventory (STAI) [34] subscale, respectively. Higher CES-D scores indicate greater depression severity [33, 35]. STAI State is a 20-item self-report measure to assess current anxiety, with scores ranging from 20 to 80; higher scores indicate greater anxiety.

Statistical Analysis

MADCO-PC’s primary aim was to determine the association between postoperative changes in cognition and CSF tau levels. For the secondary analyses reported here, univariable associations between postoperative global cognitive change (CCI change) and either preoperative depression severity or anxiety severity (as continuous variables) were examined both before and after surgery. We also examined univariable associations between pre to 6 week postoperative changes in CCI and CES-D or STAI. These associations were assessed with Pearson or Spearman correlation tests depending on whether the data was normally distributed or not, respectively. Since CCI and CCI change are means of normalized factor scores, our observed data is a sample from a known normal population distribution. Based on results of Shapiro-Wilks tests, all affective measures and their change over time were found to be non-normally distributed. This study cohort of 103 patients provided >80% power to detect a Spearman correlation of ≥0.3 between depression or anxiety scores and CCI change from before to 6 weeks after surgery. We also explored the relationship between each of the four cognitive domain scores and both CES-D and STAI scores via Spearman correlation analysis, for which multiple comparison correction was performed using the Holm method.

Additionally, multivariable linear regression analyses of CCI change were performed to examine relationships with a) baseline anxiety scores, b) baseline depression scores, c) change in anxiety scores from before to 6 weeks after surgery, and d) change in depression scores from before to 6 weeks after surgery, adjusting for potential confounders of age, years of education, and baseline CCI. We conducted residual diagnostics to ensure the assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality were met. For the multivariable models, complete model diagnostics were performed. In brief, the four criteria for appropriate model formulation were each met- the residuals were found to be unskewed, had proper kurtosis, and followed a linear link function, and there was no evidence of heteroscedasticity. Post-hoc, we explored the potential for confounding due to baseline antidepressant use and sex differences in the relationship between affective measures and their change by adding main effect and interaction terms to each of our multivariable models.

RESULTS

Of the 110 MADCO-PC patients who returned for 6-week postoperative testing, 103 had complete cognitive testing and depression/anxiety measurements at both baseline and 6-week follow-up. Baseline/preoperative characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. Of these 103 patients, 28 were taking antidepressants before and after surgery; one additional patient began antidepressant therapy after surgery, but before the 6-week postoperative assessment. Women had slightly higher CES-D and STAI scores than men at baseline, and women had higher STAI scores than men at 6 weeks after surgery (Supplemental Table 1). However, there was no evidence of a sex difference in any of the cognitive measures (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| All (N=103) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD), years | 68.7±6.2 |

| Education (mean±SD), years | 15.4±3.2 |

| Sex, % male | 63 (61.2) |

| Race, % white | 93 (90.3) |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 29.2±5.9 |

| Surgical Service, % | |

| Thoracic | 9.7 |

| General Surgery | 28.2 |

| Gynecology | 1.9 |

| Orthopedics | 17.5 |

| Otolaryngology Head/Neck | 1.9 |

| Plastic Surgery | 2.9 |

| Urology | 37.9 |

| Surgery Duration (median[IQR]), min | 141 [100–200.5] |

| Baseline MMSE (mean±SD) | 28.36±1.67 |

| Baseline CCI (mean±SD) | 0.17±0.66 |

| Mean Change in CCI (mean±SD) | 0.04±0.31 |

| Baseline CES-D (mean±SD) | 9.65±8.34 |

| Change in CES-D (mean±SD) | −0.42±8.16 |

| Baseline STAI (mean±SD) | 30.19±9.22 |

| Change in STAI (mean±SD) | −1.45±7.80 |

Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; CCI, continuous cognitive index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Subscale

Univariable Associations between Depression Severity, Anxiety Severity and Cognitive Change

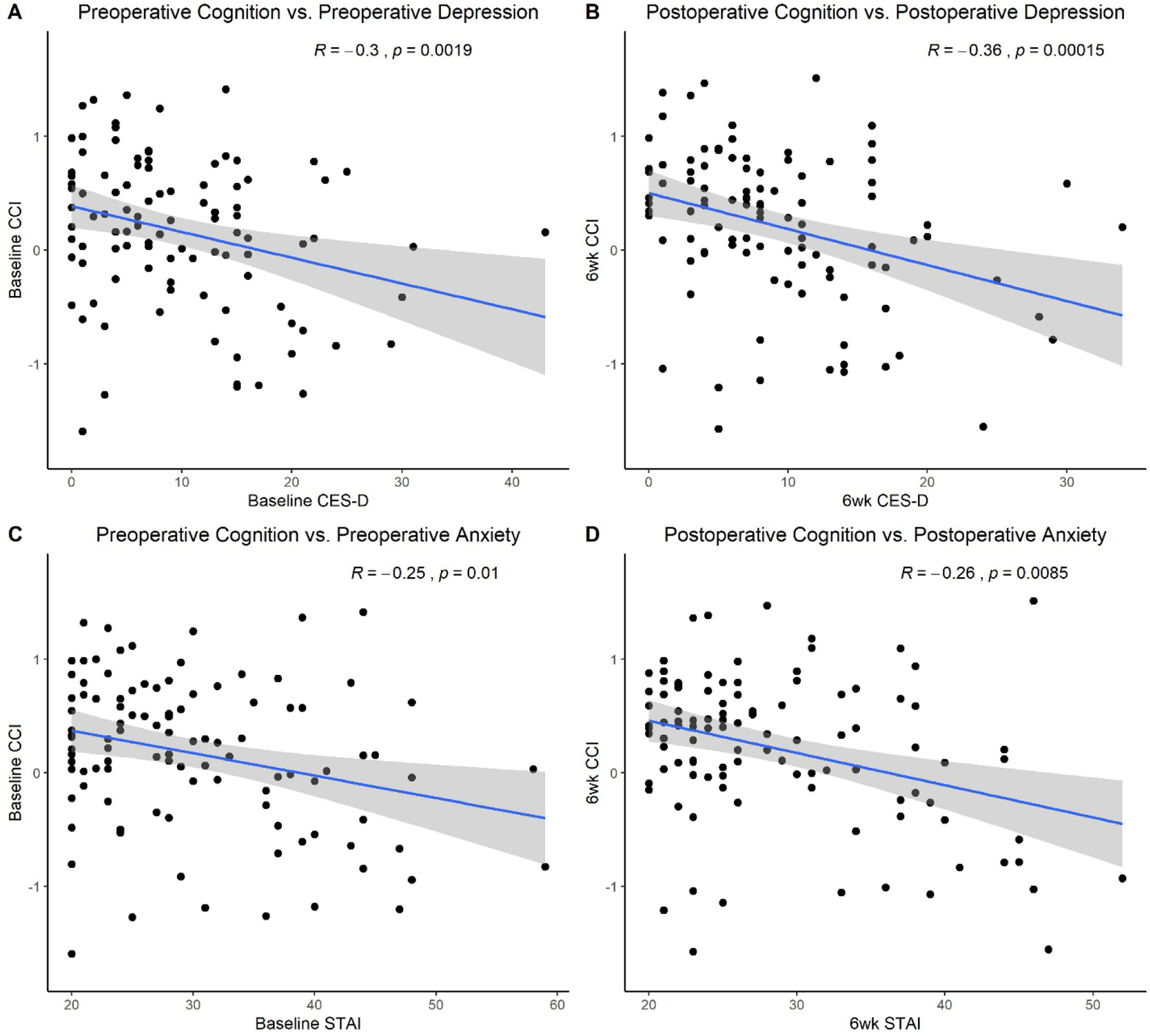

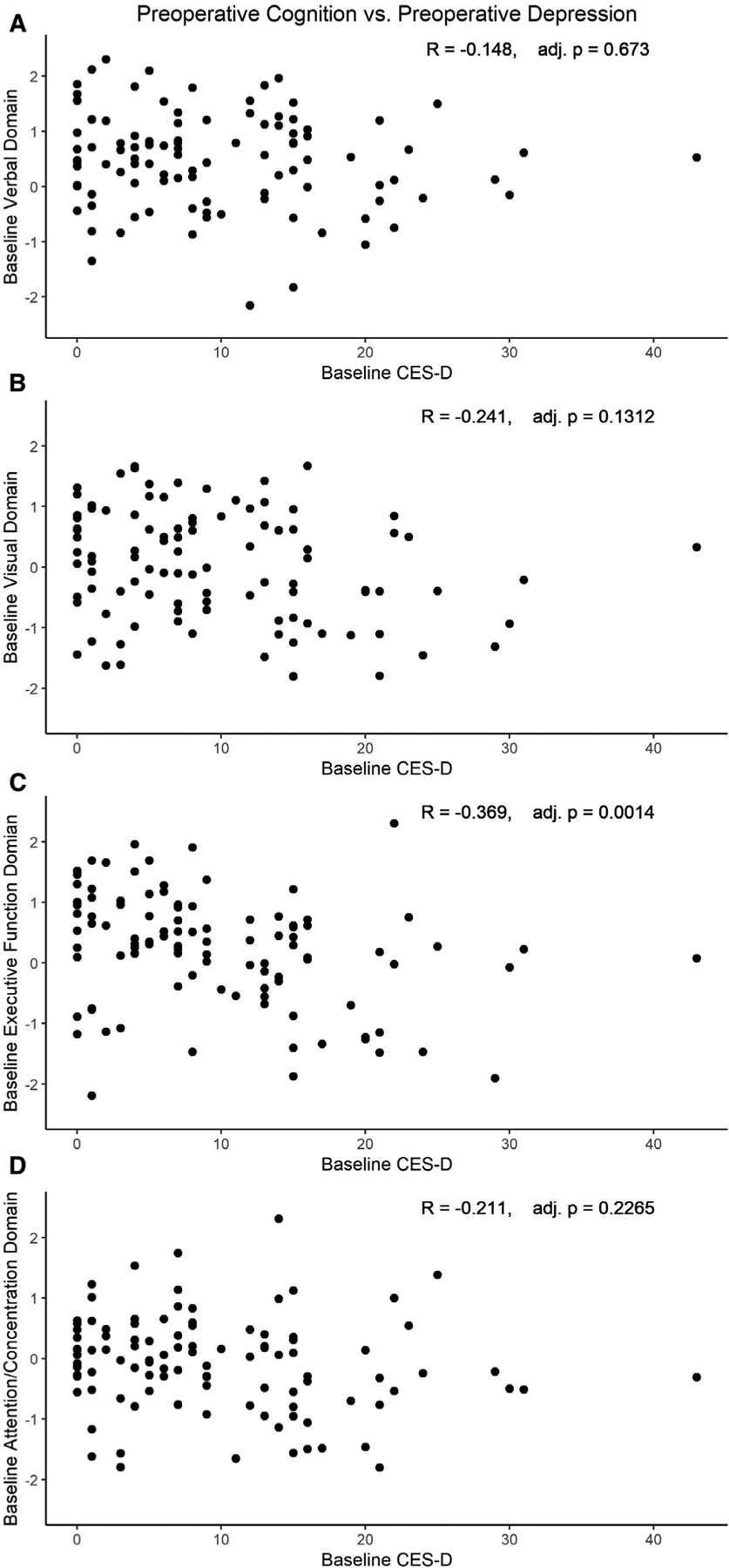

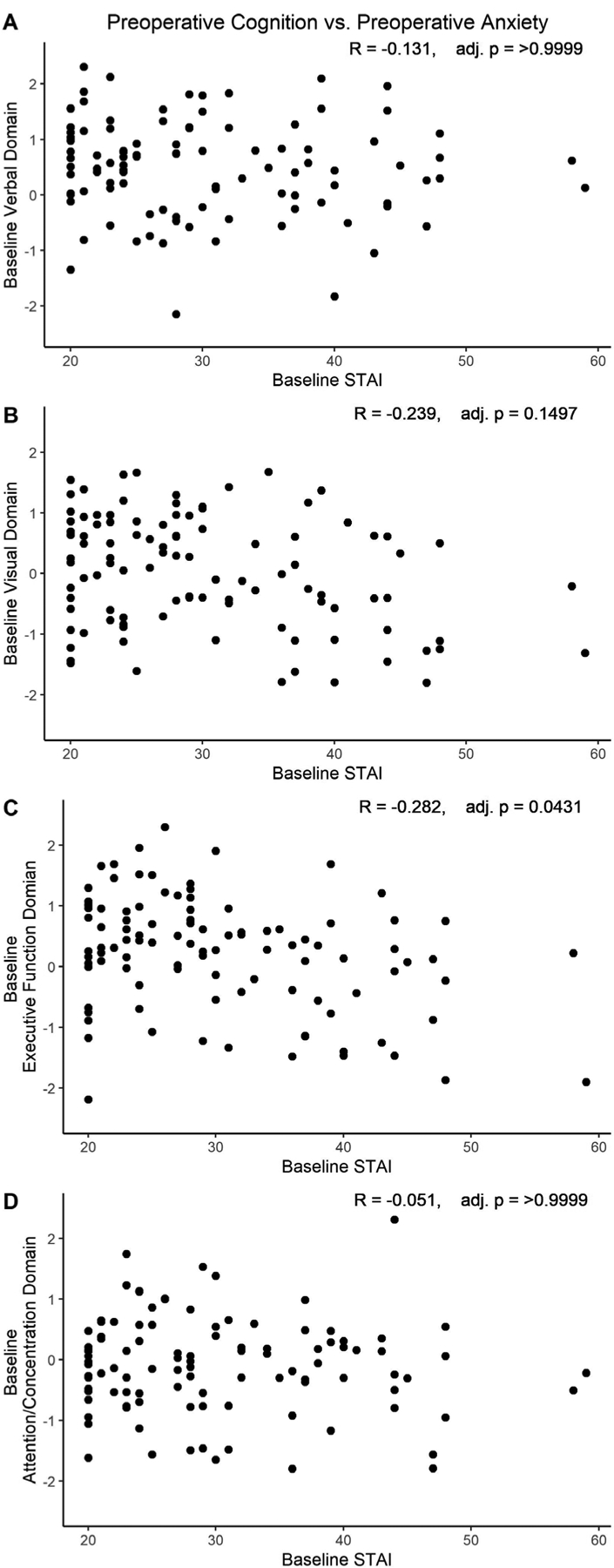

Across all patients, lower preoperative global cognition (CCI) was associated with greater depression severity (Spearman’s r=−0.30, p=0.002) and greater anxiety severity (Spearman’s r=−0.25, p=0.010) before surgery (Figure 1A, 1C). The correlation between baseline affective measures and global cognition was likely driven by highly significant correlations between baseline executive function (one of the four cognitive domain factors that make up the CCI score [20, 28]) and both baseline depression scores (r=−0.369, p=0.001; Figure 2C) and baseline anxiety scores (r=−0.239, p=0.043; Figure 4C).

Figure 1.

Relationship between affective and cognitive function before and after surgery. a) preoperative CCI and preoperative CES-D scores; b) postoperative CCI and postoperative CES-D scores; and preoperative cognition; c) preoperative CCI and preoperative STAI scores; d) postoperative CCI and postoperative STAI scores. CCI, continuous cognitive index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Subscale

Figure 2.

Relationship between preoperative depression severity and cognitive domain scores. Baseline CES-D score correlations with preoperative A) verbal domain, B) visual domain, C) executive function, D) attention/concentration. CCI, continuous cognitive index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Figure 4.

Relationship between preoperative anxiety severity and cognitive domain scores. Baseline STAI score correlations with preoperative A) verbal domain, B) visual domain, C) executive function, D) attention/concentration. CCI, continuous cognitive index; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Subscale.

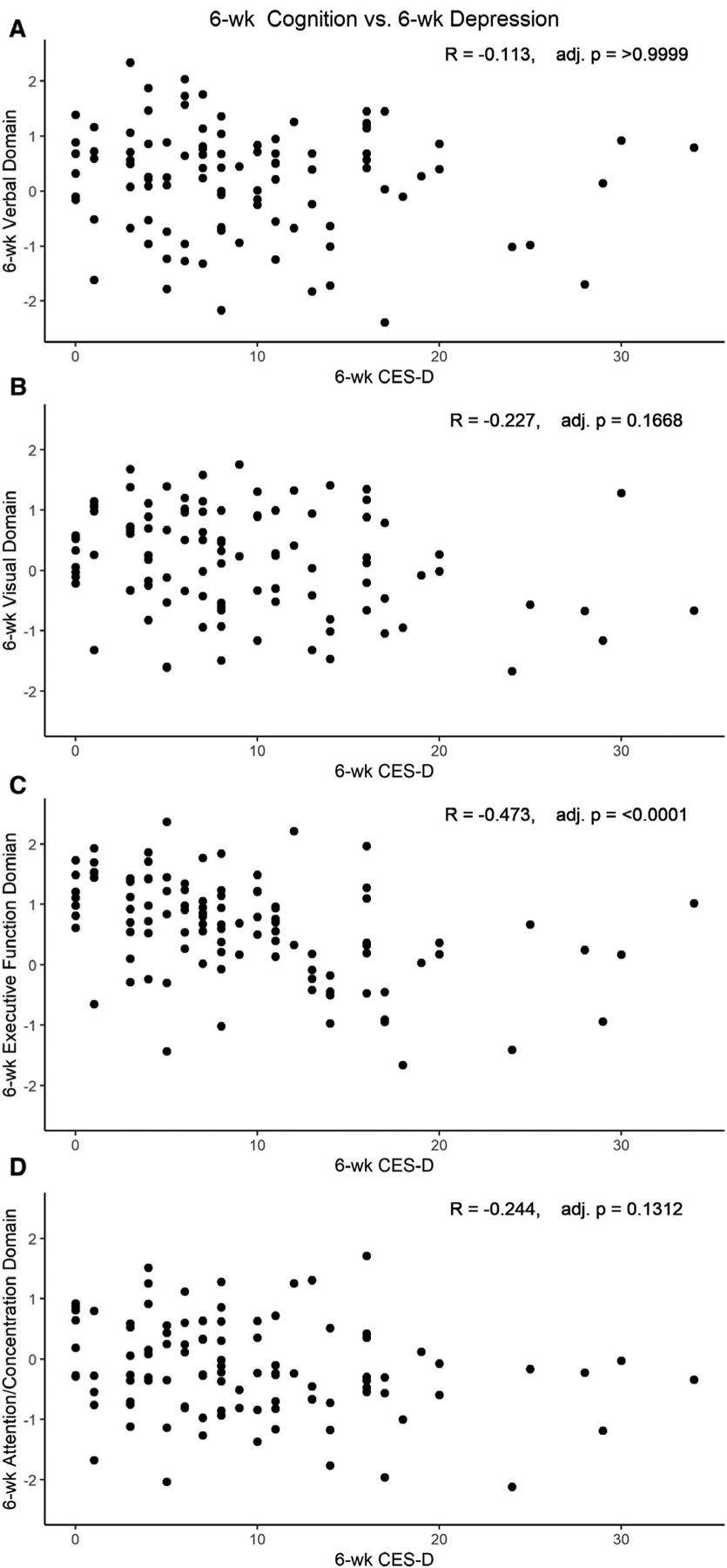

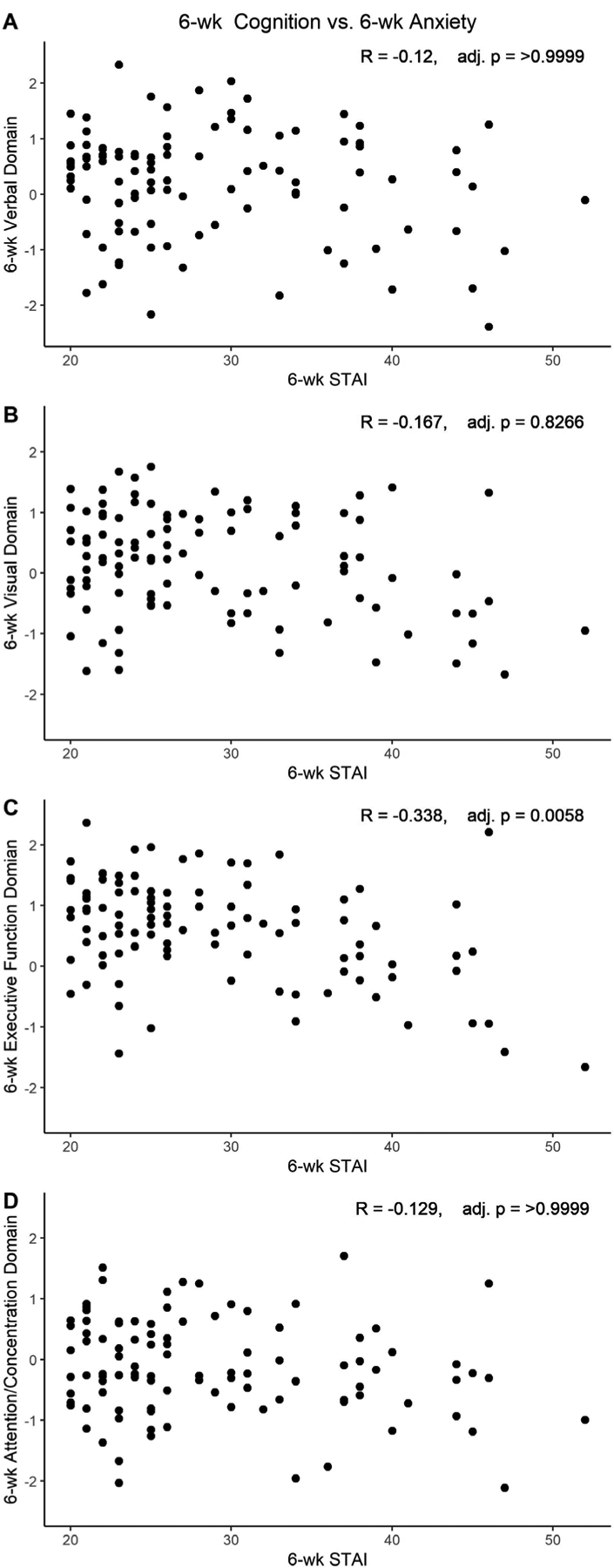

Similarly, lower 6 week postoperative CCI (worse cognitive function) was associated with greater depression severity (Spearman’s r=−0.36, p<0.001; Figure 1B) and anxiety severity (Spearman’s r=−0.26, p=0.008; Figure 1D) 6 weeks after surgery. The relationship between six week postoperative affective measures and cognition was again likely driven by highly significant correlations between the 6 week postoperative executive function domain score and both 6 week postoperative depression (r=−0.473 (p<0.001; Figure 3C) and 6 week postoperative anxiety scores (r=−0.338, p=0.006; Figure 5C).

Figure 3.

Relationship between postoperative depression severity and postoperative cognitive domain scores. Six week postoperative CES-D score correlation with 6 week postoperative A) verbal domain, B) visual domain, C) executive function domain, D) attention/concentration domain. CCI, continuous cognitive index; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Figure 5.

Relationship between postoperative anxiety severity and postoperative cognitive domain scores. Six week postoperative STAI score correlation with 6 week postoperative A) verbal domain, B) visual domain, C) executive function domain, D) attention/concentration domain. CCI, continuous cognitive index; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State Subscale.

There were no significant correlations between baseline depression severity or baseline anxiety severity and postoperative global cognitive change (e.g. CCI change; Spearman’s r=0.07, p=0.513; Spearman’s r=−0.06, p=0.576, respectively). There were also no significant correlations between postoperative changes in depression severity or anxiety severity and the magnitude of postoperative global cognitive change (Spearman’s r=−0.11, p=0.267; Spearman’s r=−0.04, p=0.710; Supplemental Figure 1). Similarly, there was no correlation between postoperative changes in depression severity and postoperative changes in any of the four cognitive domains (Supplemental Figure 2), or between postoperative changes in anxiety and postoperative changes in any of the four cognitive domains (Supplemental Figure 3). We explored the potential for non-linear relationships between our affective measures and cognition and in each of these univariable models (Figures 1–5, Supplemental Figures 1–3), and there was no evidence of quadratic (or cubic) relationships between our independent variables (i.e. affective measures or their change over time) and dependent variable of interest (CCI or CCI change over time).

Multivariable Associations between Depression Severity, Anxiety Severity and Cognitive Change

Multivariable models for global cognitive change (i.e. CCI change from before to 6 weeks after surgery) were constructed, adjusting for age, years of education, and baseline CCI. These global cognitive change models showed no significant effect of baseline depression severity (β=0.00, 95% CI −0.01, 0.01; p=0.956), or postoperative change in depression severity (β=−0.00, 95% CI, −0.01, 0.00; p=0.355; Table 2). A non-negligible proportion of our cohort was taking antidepressants as baseline (n=28, 27%), but when antidepressant use was added to our multivariable model as both a main effect and as an interaction effect with CES-D measures, there remained no evidence of an association between changes in depression and cognition. A post-hoc investigation for sex differences in our multivariable models for global cognitive change also found no significant main effect for sex, nor evidence for interaction of sex with any of the affective measures (p>0.05 for all).

Table 2.

Effect of Depression and Anxiety on Pre- to Postoperative Change in Cognition in Multivariable Models. Each line in the table is from a different such model; each model was adjusted for age, years of education, and baseline cognition.

| Adjusted R2 | Beta Coefficients | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline CES-D | 0.062 | 0.000 (−0.008, 0.007) | 0.956 |

| CES-D Change | 0.070 | −0.003 (−0.011, 0.004) | 0.355 |

| Baseline STAI | 0.076 | −0.004 (−0.011, 0.002) | 0.216 |

| STAI Change | 0.070 | −0.002 (−0.010, 0.005) | 0.462 |

DISCUSSION

Here, we found significant associations between depression and anxiety severity measures and global cognition before and 6 weeks after non-cardiac surgery in older adults, effects that were largely driven by relatively tighter associations between executive function and these affective measures both before and 6 weeks after surgery. Prior studies have shown that baseline depression, anxiety, and poor cognitive function are associated with worse outcomes after surgery [3, 9, 36]. Depression in particular has been associated with increased postoperative morbidity and mortality [36]. Our findings replicated prior studies demonstrating a cross-sectional association between depression severity, anxiety severity, and cognitive function both before and after surgery [37, 38]. However, our findings did not support the hypothesis that baseline depression and/or anxiety severity, or postoperative changes in these measures, would be associated with the magnitude of global cognitive change from before to after surgery.

The tight correlations observed here between executive function and both depression and anxiety scores fit with a large body of literature demonstrating that depression is associated with poorer executive function [39]. Further, these executive function deficits persist in many individuals even after their depressive symptoms have improved [39, 40]. Depression is also prevalent among community-dwelling older adults with cognitive impairment [41]. Cognitive dysfunction among individuals with depression appears to be associated with subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease (e.g. endothelial dysfunction), independent of the severity of depressive symptoms [42].

Depression prior to surgery has been associated with increased risk of delirium and cognitive dysfunction following surgery [43–45], which may be partly attributable to elevated emotional and psychological stress following surgery. Few studies, however, have examined depressive or anxiety symptoms following non-cardiac surgery and their association with cognitive function, despite recent data suggesting that both depression and cognitive dysfunction are associated with increased mortality risk during the first postoperative year [46]. Our findings therefore extend prior work by demonstrating that the associations between depression, anxiety, and cognitive function are robust both before and after non-cardiac surgery.

We had hypothesized that patients with worse preoperative depression would have further worsening of postoperative depression due to additional physical stress from surgery [47], and thus would have greater cognitive deficits after surgery. Yet, we did not observe a significant relationship between baseline preoperative depression severity and postoperative cognitive change. It is unlikely that the lack of association between depression and anxiety severity and cognitive change was due to a type II statistical error (i.e. insufficient sample size), as this study had >80% power to detect a spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.3, a low to moderate correlation. Instead, this lack of association between postoperative cognitive and affective changes is likely a true negative finding. This negative funding may be due in part to the variety of surgeries represented in our study cohort. We included participants across various surgical subspecialties with the intention of increasing the generalizability of our findings. Yet, this procedural diversity may have reduced our ability to observe significant relationships between participants’ baseline affective health and postoperative cognitive change, if the relationship between these variables differs across surgery types. It is possible that some depressed patients would have worsened cognition after surgery, while others would see marked postoperative cognitive improvements, particularly if surgery addressed a cause of their depression. For example, patients with depression related to impaired mobility and functionality due to a hip injury might have less depression and a related improvement in cognition after a hip arthroplasty, if the hip arthroplasty improves their mobility. Our findings may also have been influenced by the relatively high education level of our sample, suggesting elevated cognitive reserve. Higher levels of cognitive reserve have been associated with lower risk of neurocognitive disorders following surgery, independent of pre-surgical mood symptoms [48, 49].

The association between depression and cognition in older adults has been extensively studied, however, the relationship between anxiety and cognition is less clear, with evidence both for and against associations between anxiety and cognition. Some studies have found associations between anxiety and both memory and executive function deficits in older adults [50, 51], while other studies have shown that state anxiety in particular is not associated with significant cognitive deficits [52]. Prior studies have not found a relationship between state anxiety prior to surgery and postoperative cognitive change, and our study findings are consistent with cardiac surgery studies showing no significant relationship between postoperative changes in state anxiety and cognition [1, 20].

While this study did not find a correlation between either baseline anxiety or depression severity and postoperative cognitive change, it did confirm that in older adults, increased depression and/or anxiety severity are associated with lower cognitive function, both before and after surgery. This finding highlights the importance of depression and anxiety assessments in the perioperative period. Depression and anxiety can be managed with pharmacologic and/or behavioral interventions, which could potentially lead to improved cognition before and after surgery. Studies examining the effects of anxiolytics, antidepressants, or behavioral therapy on perioperative cognition have focused primarily on spinal and cardiac surgery patients [53, 54]. Thus, more studies are needed to examine the effects of treating preoperative depression on cognitive outcomes after non-cardiac surgery [9]. Ideally, this should be prospectively studied in older patient cohorts undergoing a single type of surgery, since the relationship between affective and cognitive measures could differ across surgery types. In prior randomized trials, depressed older adult outpatients have shown improvements in cognitive function following selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) administration [55–57]. Thus, future studies are also warranted to examine the effect of SSRI treatment or other treatment strategies on both mood and cognition following non-cardiac surgery in older adults.

Conclusion

In conclusion, both depressive and anxiety symptoms were associated with cognitive function in older adults both before and after a variety of different surgical procedures. Future studies should examine whether the associations seen here between affective and cognitive function after surgery in older adults reflect causal relationships, by determining whether modulating mood via antidepressant treatment or other therapeutic modalities would improve cognition as well as mood following surgery in older adults.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alicia Pucci, Karen Clemmons, Naraida Balajonda and the Duke Anesthesiology Clinical Anesthesiology Research Endeavors (CARE) staff for help with enrolling study patients, and for performing cognitive testing on these patients. We also thank Kathy Gage for editorial assistance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Dr. Berger acknowledges funding from Minnetronix, Inc. (St. Paul, Minnesota), for a project unrelated to the subject matter of this review, and has received material support, i.e., electroencephalogram monitors, from Masimo, Inc. (Irvine, California) for a postoperative recovery study in older adults. Dr. Berger has also received legal consulting fees related to postoperative cognition in older adults. Dr. Browndyke acknowledges funding from Claret Medical, Inc. (Santa Rosa, California). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the International Anesthesia Research Society Mentored Research Award and grants T32 #GM08600 and R03-AG050918 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Berger also acknowledges support from a Jahnigen Award from the American Geriatrics Society and the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, Duke Anesthesiology departmental funds, and additional support from the NIH [P30AG028716, K76AG057022]. Ms. Oyeyemi acknowledges support from the Pfizer Foundation and a Duke Clinical Translational Science Institute grant. Dr. Whitson acknowledges support from the NIH [UH2AG056925, UL1TR002553]. Dr. Browndyke acknowledges support from the NIH [R01-HL130443, R01-AG042599, R21-HL10997]. The investigators retained full independence in the conduct of this research.

Sponsors’ Role

The funding sources had no role in study design and methodology, nor in sample analysis and preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Preliminary results presented at: American Geriatrics Society Annual Meeting, 2019

REFERENCES

- [1].Phillips-Bute B, Mathew JP, Blumenthal JA, Grocott HP, Laskowitz DT, Jones RH, Mark DB, Newman MF (2006) Association of neurocognitive function and quality of life 1 year after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Psychosom Med 68, 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Blumenthal JA, Lett HS, Babyak MA, White W, Smith PK, Mark DB, Jones R, Mathew JP, Newman MF, Investigators N (2003) Depression as a risk factor for mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery. Lancet 362, 604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Williams JB, Alexander KP, Morin JF, Langlois Y, Noiseux N, Perrault LP, Smolderen K, Arnold SV, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L, Monette J, Bergman H, Smith PK, Afilalo J (2013) Preoperative anxiety as a predictor of mortality and major morbidity in patients aged >70 years undergoing cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 111, 137–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Deiner S, Liu X, Lin HM, Sieber F, Boockvar K, Sano M, Baxter MG (2019) Subjective cognitive complaints in patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery: a prospective single centre cohort trial. Br J Anaesth 122, 742–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Smith PJ, Attix DK, Weldon BC, Greene NH, Monk TG (2009) Executive function and depression as independent risk factors for postoperative delirium. Anesthesiology 110, 781–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leung JM, Sands LP, Mullen EA, Wang Y, Vaurio L (2005) Are preoperative depressive symptoms associated with postoperative delirium in geriatric surgical patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60, 1563–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Oh ES, Fong TG, Hshieh TT, Inouye SK (2017) Delirium in Older Persons: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA 318, 1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vasunilashorn SM, Devinney MJ, Acker L, Jung Y, Ngo L, Cooter M, Huang R, Marcantonio ER, Berger M (2020) A New Severity Scoring Scale for the 3-Minute Confusion Assessment Method (3D-CAM). J Am Geriatr Soc 68, 1874–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Berger M, Nadler JW, Browndyke J, Terrando N, Ponnusamy V, Cohen HJ, Whitson HE, Mathew JP (2015) Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: Minding the Gaps in Our Knowledge of a Common Postoperative Complication in the Elderly. Anesthesiol Clin 33, 517–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Berger M, Terrando N, Smith SK, Browndyke JN, Newman MF, Mathew JP (2018) Neurocognitive Function after Cardiac Surgery: From Phenotypes to Mechanisms. Anesthesiology 129, 829–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Berger M, Murdoch DM, Staats JS, Chan C, Thomas JP, Garrigues GE, Browndyke JN, Cooter M, Quinones QJ, Mathew JP, Weinhold KJ, Team M-PS (2019) Flow Cytometry Characterization of Cerebrospinal Fluid Monocytes in Patients With Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction: A Pilot Study. Anesth Analg 129, e150–e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Djaiani GN, Phillips-Bute B, Blumenthal JA, Newman MF (2003) Chronic exposure to nicotine does not prevent neurocognitive decline after cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 17, 341–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fontes MT, McDonagh DL, Phillips-Bute B, Welsby IJ, Podgoreanu MV, Fontes ML, Stafford-Smith M, Newman MF, Mathew JP (2014) Arterial hyperoxia during cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative cognitive dysfunction. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 28, 462–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fontes MT, Swift RC, Phillips-Bute B, Podgoreanu MV, Stafford-Smith M, Newman MF, Mathew JP (2013) Predictors of cognitive recovery after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg 116, 435–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Grocott HP, Mackensen GB, Grigore AM, Mathew J, Reves JG, Phillips-Bute B, Smith PK, Newman MF (2002) Postoperative hyperthermia is associated with cognitive dysfunction after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Stroke 33, 537–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Klinger RY, Cooter M, Bisanar T, Terrando N, Berger M, Podgoreanu MV, Stafford-Smith M, Newman MF, Mathew JP (2019) Intravenous Lidocaine Does Not Improve Neurologic Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 130, 958–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Mathew JP, Mackensen GB, Phillips-Bute B, Stafford-Smith M, Podgoreanu MV, Grocott HP, Hill SE, Smith PK, Blumenthal JA, Reves JG, Newman MF (2007) Effects of extreme hemodilution during cardiac surgery on cognitive function in the elderly. Anesthesiology 107, 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mathew JP, White WD, Schinderle DB, Podgoreanu MV, Berger M, Milano CA, Laskowitz DT, Stafford-Smith M, Blumenthal JA, Newman MF, Neurologic Outcome Research Group of The Duke Heart C (2013) Intraoperative magnesium administration does not improve neurocognitive function after cardiac surgery. Stroke 44, 3407–3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Newman MF, Grocott HP, Mathew JP, White WD, Landolfo K, Reves JG, Laskowitz DT, Mark DB, Blumenthal JA (2001) Report of the substudy assessing the impact of neurocognitive function on quality of life 5 years after cardiac surgery. Stroke 32, 2874–2881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, Mark DB, Reves JG, Blumenthal JA, Neurological Outcome Research G, the Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Research Endeavors I (2001) Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 344, 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stanley TO, Mackensen GB, Grocott HP, White WD, Blumenthal JA, Laskowitz DT, Landolfo KP, Reves JG, Mathew JP, Newman MF (2002) The impact of postoperative atrial fibrillation on neurocognitive outcome after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesth Analg 94, 290–295, table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Moller JT, Cluitmans P, Rasmussen LS, Houx P, Rasmussen H, Canet J, Rabbitt P, Jolles J, Larsen K, Hanning CD, Langeron O, Johnson T, Lauven PM, Kristensen PA, Biedler A, van Beem H, Fraidakis O, Silverstein JH, Beneken JE, Gravenstein JS (1998) Long-term postoperative cognitive dysfunction in the elderly ISPOCD1 study. ISPOCD investigators. International Study of Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction. Lancet 351, 857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, Scott DA, DeKosky ST, Rasmussen LS, Oh ES, Crosby G, Berger M, Eckenhoff RG, Nomenclature Consensus Working G (2018) Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Cognitive Change Associated With Anaesthesia and Surgery-2018. Anesth Analg 127, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, Scott CP, Rodriguez E, Imber SD, Perel J, Lave J, Houck PR, Coulehan JL (1996) Treating major depression in primary care practice. Eight-month clinical outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53, 913–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, Rodriguez E (1997) Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Arch Intern Med 157, 1113–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr., Trivedi M, Chiquette E, Aguilar C, Cornell JE, Badgett R, Noel PH, Lawrence V, Lee S, Luther M, Ramirez G, Richardson WS, Stamm K (1999) Treatment of depression--newer pharmacotherapies. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ), 1–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Mulrow CD, Williams JW Jr., Chiquette E, Aguilar, Hitchcock-Noel P, Lee S, Cornell J, Stamm K (2000) Efficacy of newer medications for treating depression in primary care patients. Am J Med 108, 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Giattino CM, Gardner JE, Sbahi FM, Roberts KC, Cooter M, Moretti E, Browndyke JN, Mathew JP, Woldorff MG, Berger M, Investigators M-P (2017) Intraoperative Frontal Alpha-Band Power Correlates with Preoperative Neurocognitive Function in Older Adults. Front Syst Neurosci 11, 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Horlocker TT, Wedel DJ, Rowlingson JC, Enneking FK, Kopp SL, Benzon HT, Brown DL, Heit JA, Mulroy MF, Rosenquist RW, Tryba M, Yuan CS (2010) Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Third Edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med 35, 64–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].McDonagh DL, Mathew JP, White WD, Phillips-Bute B, Laskowitz DT, Podgoreanu MV, Newman MF, Neurologic Outcome Research G (2010) Cognitive function after major noncardiac surgery, apolipoprotein E4 genotype, and biomarkers of brain injury. Anesthesiology 112, 852–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Browndyke JN, Berger M, Harshbarger TB, Smith PJ, White W, Bisanar TL, Alexander JH, Gaca JG, Welsh-Bohmer K, Newman MF, Mathew JP (2017) Resting-State Functional Connectivity and Cognition After Major Cardiac Surgery in Older Adults without Preoperative Cognitive Impairment: Preliminary Findings. J Am Geriatr Soc 65, e6–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Browndyke JN, Berger M, Smith PJ, Harshbarger TB, Monge ZA, Panchal V, Bisanar TL, Glower DD, Alexander JH, Cabeza R, Welsh-Bohmer K, Newman MF, Mathew JP, Duke Neurologic Outcomes Research G (2018) Task-related changes in degree centrality and local coherence of the posterior cingulate cortex after major cardiac surgery in older adults. Hum Brain Mapp 39, 985–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Radloff LS (1977) The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) STAI manual for the Stait-Trait Anxiety Inventory (“self-evaluation questionnaire”), Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, Calif. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB (1997) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging 12, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ghoneim MM, O’Hara MW (2016) Depression and postoperative complications: an overview. BMC Surg 16, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dotson VM, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB (2008) Differential association of concurrent, baseline, and average depressive symptoms with cognitive decline in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16, 318–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Stillman AN, Rowe KC, Arndt S, Moser DJ (2012) Anxious symptoms and cognitive function in non-demented older adults: an inverse relationship. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 27, 792–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lockwood KA, Alexopoulos GS, van Gorp WG (2002) Executive dysfunction in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry 159, 1119–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Semkovska M, Quinlivan L, O’Grady T, Johnson R, Collins A, O’Connor J, Knittle H, Ahern E, Gload T (2019) Cognitive function following a major depressive episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 6, 851–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Boyle LL, Porsteinsson AP, Cui X, King DA, Lyness JM (2010) Depression predicts cognitive disorders in older primary care patients. J Clin Psychiatry 71, 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Smith PJ, Blumenthal JA, Hinderliter AL, Watkins LL, Hoffman BM, Sherwood A (2018) Microvascular Endothelial Function and Neurocognition Among Adults With Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 26, 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Galanakis P, Bickel H, Gradinger R, Von Gumppenberg S, Förstl H (2001) Acute confusional state in the elderly following hip surgery: incidence, risk factors and complications. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16, 349–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Greene NH, Attix DK, Weldon BC, Smith PJ, McDonagh DL, Monk TG (2009) Measures of executive function and depression identify patients at risk for postoperative delirium. Anesthesiology 110, 788–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kadoi Y, Kawauchi C, Ide M, Kuroda M, Takahashi K, Saito S, Fujita N, Mizutani A (2011) Preoperative depression is a risk factor for postoperative short-term and long-term cognitive dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Anesth 25, 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tang VL, Jing B, Boscardin J, Ngo S, Silvestrini M, Finlayson E, Covinsky KE (2020) Association of Functional, Cognitive, and Psychological Measures With 1-Year Mortality in Patients Undergoing Major Surgery. JAMA Surg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Willner P (2017) The chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression: History, evaluation and usage. Neurobiol Stress 6, 78–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Du J, Plas M, Absalom AR, van Leeuwen BL, de Bock GH (2020) The association of preoperative anxiety and depression with neurocognitive disorder following oncological surgery. J Surg Oncol 121, 676–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Scott JE, Mathias JL, Kneebone AC, Krishnan J (2017) Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and its relationship to cognitive reserve in elderly total joint replacement patients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 39, 459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yochim BP, Mueller AE, Segal DL (2013) Late life anxiety is associated with decreased memory and executive functioning in community dwelling older adults. J Anxiety Disord 27, 567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R (2008) Late-life anxiety and cognitive impairment: a review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 16, 790–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Potvin O, Bergua V, Meillon C, Le Goff M, Bouisson J, Dartigues JF, Amieva H (2013) State anxiety and cognitive functioning in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 21, 915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Altiparmak B, Guzel C, Gumus Demirbilek S (2018) Comparison of Preoperative Administration of Pregabalin and Duloxetine on Cognitive Functions and Pain Management After Spinal Surgery: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Clin J Pain 34, 1114–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Freedland KE, Skala JA, Carney RM, Rubin EH, Lustman PJ, Davila-Roman VG, Steinmeyer BC, Hogue CW Jr. (2009) Treatment of depression after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66, 387–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Cassano GB, Puca F, Scapicchio PL, Trabucchi M, Italian Study Group on Depression in Elderly P (2002) Paroxetine and fluoxetine effects on mood and cognitive functions in depressed nondemented elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 63, 396–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Newhouse PA, Krishnan KR, Doraiswamy PM, Richter EM, Batzar ED, Clary CM (2000) A double-blind comparison of sertraline and fluoxetine in depressed elderly outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 61, 559–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, Sheikh J, Xu J, Dinkel JJ, Rotz BT, Mohs RC (2007) Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 164, 900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.