Abstract

Background

This an update of a Cochrane Review.

Paraquat is a widely used herbicide, but is also a lethal poison. In some low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) paraquat is commonly available and inexpensive, making poisoning prevention difficult. Most of the people poisoned by paraquat have taken it as a means of self‐poisoning.

Standard treatment for paraquat poisoning prevents further absorption and reduces the load of paraquat in the blood through haemoperfusion or haemodialysis. The effectiveness of standard treatments is extremely limited.

The immune system plays an important role in exacerbating paraquat‐induced lung fibrosis. Immunosuppressive treatment using glucocorticoid and cyclophosphamide in combination has been developed and studied as an intervention for paraquat poisoning.

Objectives

To assess the effects of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide for moderate to severe oral paraquat poisoning.

Search methods

The most recent searches were run in September 2020. We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Injuries Trials Register), Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE, Embase Classic + Embase (Ovid), ISI WOS (SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, CPCI‐S, and CPSI‐SSH), and trials registries. We also searched the following three resources: China National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI 数据库); Wanfang Data (万方数据库); and VIP (维普数据库) on 12 November 2020. We examined the reference lists of included studies and review papers.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs). For this update, in accordance with Cochrane Injuries' Group policy (2015), we included only prospectively registered RCTs for trials published after 2010. We included trials which assessed the effects of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide delivered in combination. Eligible comparators were standard care (with or without a placebo), or any other therapy in addition to standard care. Outcomes of interest included mortality and infections.

Data collection and analysis

We calculated the mortality risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Where possible, we summarised data for all‐cause mortality at relevant time periods (from hospital discharge to three months after discharge) in meta‐analysis, using a fixed‐effect model. We conducted sensitivity analyses based on factors including whether participants were assessed at baseline for plasma paraquat levels. We also reported data on infections within one week after initiation of treatment.

Main results

We included four trials with a total of 463 participants. The included studies were conducted in Taiwan (Republic of China), Iran, and Sri Lanka. Most participants were male. The mean age of participants was 28 years.

We judged two of the four included studies, including the largest and most recently conducted study (n = 299), to be at low risk of bias for key domains including sequence generation. We assessed one study to be at high risk of selection bias and another at unclear risk, since allocation concealment was either not mentioned in the trial report or explicitly not undertaken. We assessed three of the four studies to be at unclear risk of selective reporting, as no protocols could be identified. An important source of heterogeneity amongst the included studies was the method of assessment of participants' baseline severity using analysis of plasma levels (two studies employed this method, whilst the other two did not).

No studies assessed the outcome of mortality at 30 days following ingestion of paraquat.

Low‐certainty evidence from two studies indicates that glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may slightly reduce the risk of death in hospital compared to standard care alone ((RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99; participants = 322); results come from sensitivity analysis excluding studies not assessing plasma at baseline). However, we have limited confidence in this finding as heterogeneity was high (I2 = 77%) and studies varied in terms of size and comparators. A single large study provided data showing that there may be little or no effect of treatment at three months post discharge from hospital (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13; 1 study, 293 participants; low‐certainty evidence); however, analysis of long‐term results amongst participants whose injuries arose from self‐poisoning must be interpreted with caution.

We remain uncertain of the effect of glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide on infection within one week after initiation of the treatment; this outcome was assessed by two small studies only (31 participants, very low‐certainty evidence) that considered leukopenia as a proxy or risk factor for infection. Neither study reported infections in any participants.

Authors' conclusions

Low‐certainly evidence suggests that glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may slightly reduce mortality in hospitalised people with oral paraquat poisoning. However, we have limited confidence in this finding because of substantial heterogeneity and concerns about imprecision. Glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may have little or no effect on mortality at three months after hospital discharge. We are uncertain whether glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide puts patients at an increased risk of infection due to the limited evidence available for this outcome. Future research should be prospectively registered and CONSORT‐compliant. Investigators should attempt to ensure an adequate sample size, screen participants for inclusion rigorously, and seek long‐term follow‐up of participants. Investigators may wish to research the effects of glucocorticoid in combination with other treatments.

Plain language summary

What are the benefits and risks of treating paraquat poisoning with a combination of steroids and cyclophosphamide (an anti‐cancer medicine)?

Key messages

‐ Steroids given with cyclophosphamide (an anti‐cancer medicine) are unlikely to reduce the risk of death after paraquat poisoning in the short term, or at three months after hospital discharge.

‐ We are uncertain whether these medicines increase the risk of infection.

‐ Future studies need to be larger, measure the level of paraquat poisoning of patients accurately, and monitor patients in the long term. Research into steroids combined with other treatments could be useful.

What happens in people with paraquat poisoning?

Paraquat is used as a herbicide, but is also a deadly poison. Most people who are poisoned by paraquat have taken it as a means of self‐poisoning.

Treatment for paraquat poisoning focuses on the physical removal (via stomach pumping and other methods) of as much paraquat as possible from the person's digestive system (stomach) and blood. Any paraquat that remains inside the body causes inflammation that can damage the lungs severely and lead to death.

Steroids and cyclophosphamide (a medicine normally used in cancer treatment) are medicines that fight inflammation and so are also used to treat paraquat poisoning.

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out if a combination of steroids and cyclophosphamide (plus usual care) works better than usual care alone to reduce the number of people who die from paraquat poisoning.

We also wanted to find out if treatment with steroids plus cyclophosphamide causes an increased number of infections in patients.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that investigated the use of steroids and cyclophosphamide (plus usual care) compared with usual care alone in people poisoned with paraquat.

We compared and summarised the results of the studies and rated our confidence in the evidence, based on factors such as study methods and sizes.

What did we find?

We found four studies that involved 463 people with confirmed paraquat poisoning. Two studies were conducted in Taiwan (Republic of China), one in Iran, and one in Sri Lanka.

All participants were given either:

‐ usual care only, or

‐ steroids (methylprednisolone alone, or with dexamethasone) plus cyclophosphamide, as well as usual care. Cyclophosphamide was given before the steroid(s) or at the same time as them.

Two of the studies measured the severity of poisoning by testing patients’ plasma (a component of blood) at the start of the study. Plasma tests provide the best assessment of how seriously a person is affected by paraquat poisoning.

One study used a placebo (sham) treatment in addition to usual care. Two studies gave patients a steroid (dexamethasone) as part of the usual care.

Death while in hospital

The combined results of two studies showed that steroids plus cyclophosphamide (plus usual care) may slightly reduce the risk of death compared to usual care alone (with, or without, placebo) in people with paraquat poisoning.

Death 3 months after hospital discharge

One large study showed that at 3 months after discharge from hospital there may be no difference in the number of deaths between the people treated with steroids plus cyclophosphamide (plus usual care) and those treated with usual care alone.

Infection

Two small studies checked levels of white blood cells in patients (low levels can increase risk of infection). Neither study reported any infections in the week following treatment with steroids and cyclophosphamide. Due to the small size of the studies, we are very uncertain about whether the treatment affects the risk of infection within one week of treatment.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

The four studies differed in terms of the number of people in them, assessment of level of paraquat poisoning, and types of treatment. This limited our ability to draw firm conclusions from the evidence.

Overall, the studies we found were too small to provide answers to our questions.

How up to date is this evidence?

This review updates our previous review on this subject. The evidence is up to date to September 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide plus usual care compared to usual care (with or without placebo) for oral paraquat poisoning.

| Glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide plus usual care compared to usual care, with or without placebo, for oral paraquat poisoning | |||||

| Patient or population: people with moderate to severe oral paraquat poisoning Setting: hospital Intervention: glucocorticoid(s) with cyclophosphamide plus usual care Comparison: usual care (with or without placebo) | |||||

| Outcomes | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with glucocorticoid plus cyclophosphamide | ||||

| Mortality at 30 days following the ingestion of paraquat | No included studies reported this outcome. | ||||

| All‐cause mortality at final follow‐up: at hospital discharge | 322 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99) (results of a sensitivity analysis) |

63 per 100 | 52 per 100 (43 to 62) |

| All‐cause mortality at final follow‐up: 3 months |

293 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 2,3 | RR 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) | 72 per 100 | 71 per 100 (61 to 81) |

| New infection within 1 week after initiation of treatment Assessed through clinical diagnosis |

0 (0 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 4 | No clinical infections were diagnosed within 1 week after initiation of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide in the included studies. Lin 1999 reported the related outcome of leukopenia in 8 of 22 participants (36.4%) in the intervention arm. These participants spontaneously recovered 1 week later, with no mortality. Lin 2006 reported leukopenia in 6 of 16 participants (37.4%) in the intervention arm, all of whom recovered within 1 to 2 weeks. Neither Gawarammana 2017, the largest included study, nor Afzali 2008, measured infection or leukopenia. | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | |||||

1The sample size fell short of the required information size (439 participants required in each arm of the study), therefore we downgraded one level for imprecision, and a further level because of the high heterogeneity (I2 = 77%). 2We downgraded one level for imprecision, as the sample fell short of the required information size (as above). 3We downgraded once for indirectness: we consider that the reasons for participant mortality whilst being treated after self‐poisoning in hospital may differ substantially from the reasons for participant mortality at longer‐term follow‐up, in the absence of any other information on cause of death. 4The largest RCT, Gawarammana 2017, did not assess infection as an outcome, therefore this outcome was assessed by only two small trials. We therefore downgraded twice for serious imprecision, and once for indirectness (i.e. the outcome of leukopenia is a precursor of, but not identical to, infection).

Background

Paraquat is one of the most widely used herbicides worldwide, and is highly toxic to humans when ingested. It is commercially produced and has been sold in around 130 countries since 1961 (Tomlin 1994). Because it is inexpensive and widely available, it is a common cause of poisoning, through accidental or voluntary ingestion. Paraquat poisoning is most prevalent in lower‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs), where its use is less stringently regulated.

Based on prevalence studies, Karunarathne 2020 estimates the global death toll from pesticide poisoning between 1960 and 2018 to be between 9,859,667 and 17,303,333, and notes that this is likely to be an underestimate. Paraquat is a principal cause of this fatal poisoning in many part of Asia and South America (Dawson 2010; Mew 2017).

The incidence of self‐poisoning increases with age, and is higher in males, although in some LMICs the incidence of self‐poisoning for young adult females exceeds that of males (Gunnell 2003).

The number of deaths due to poisoning, including those by paraquat, is now falling worldwide. This is likely to be a combination of industrialisation and the consequent movement of people out of rural areas, and the fact that many of the most dangerous pesticides, including paraquat, are being banned in an increasing number of countries (Karunarathne 2020). For example, paraquat was phased out and eventually banned in 2010 in Sri Lanka, where it had been the leading cause of death from pesticide poisoning (Eddleston 2003; Knipe 2014). In addition, the overall suicide rate by any means has also decreased markedly in China, which has driven down global numbers (Mew 2017). However, this global trend is unfortunately not reflected in all parts of the world, and the incidence of pesticide poisoning is increasing in some countries, such as Malaysia (Kamaruzaman 2019). Worldwide, pesticide poisoning still represents a serious challenge to public health and accounts for an estimated 150,000 to 168,000 annual deaths, representing around 20% of global suicides (Karunarathne 2020; Mew 2017).

Description of the condition

The mortality rate for paraquat poisoning is estimated to be as high as 60% to 90%, but the exact mechanism of this poisoning is still poorly understood (Gao 2020; Xu 2019). The damage done by paraquat is thought to be primarily due to redox cycling and the subsequent generation of highly reactive oxygen and nitrite species. The resultant oxidative stress results in mitochondrial toxicity, induced apoptosis, lipid peroxidation, and severe secondary inflammation. These mechanisms are thought to act synergistically to cause organ damage (Gao 2020; Gawarammana 2011).

Lung injury is one of the main features of paraquat poisoning: paraquat molecules selectively accumulate in the lungs, and severe inflammation and irreversible pulmonary fibrosis follows, which is known as 'paraquat lung' (Fukuda 1985; Smith 1975). This fibrosis leads to reduced ventilatory and lung diffusion capacity, resulting in hypoxaemia, which is often lethal. A large proportion of patients appear asymptomatic until signs of breathing difficulty emerge; it is difficult to predict the outcome of a patient who appears normal but is actually suffering lung fibrosis (Eddleston 2003).

Although the lung is the primary target organ, multiple organs are affected by paraquat poisoning. Renal function is impaired as the body attempts to excrete paraquat, and the hepatobiliary system, nervous system, and heart are also affected, often resulting in multiple organ failure (Gao 2020).

Diagnosis of paraquat poisoning has evolved over time. Currently the only reliable biomarker for the condition is time‐adjusted paraquat concentration.

The prognosis in paraquat poisoning is associated with the amount of toxin ingested.

In low‐dose poisoning (< 20 mg of paraquat ion per kilogram of body weight), patients are often asymptomatic, or may develop vomiting or diarrhoea, but have a good chance of recovery.

In moderate‐dose poisoning (20 mg to 40 mg of paraquat ion per kilogram of body weight), initial renal and hepatic dysfunction is common. Mucosal damage may become apparent with sloughing of the mucous membranes in the mouth. Difficulty in breathing may develop after a few days in more severe cases. After about 10 days, although renal function often returns to normal, radiological signs of lung damage usually develop. Lung damage is usually followed by irreversible massive pulmonary fibrosis manifested by the progressive loss of the lungs' ability to breathe, and deterioration continues until the patient eventually dies, between two and four weeks after ingestion.

In high‐dose poisoning (> 40 mg paraquat ion per kilogram of body weight), toxicity is much more severe, and death occurs early (within 24 h to 48 h) from multiple organ failure. Vomiting and diarrhoea are severe, with considerable fluid loss. Renal failure, cardiac arrhythmias, coma, convulsions, and oesophageal perforation lead to death (WHO IPCS 2009). This is known as fulminant poisoning (Vale 1987).

Description of the intervention

There is no specific antidote for paraquat poisoning or standard guidelines for treatment (Gawarammana 2011). Treatment often involves decontamination using absorbents such as activated charcoal or Fuller's earth; or elimination methods such as haemodialysis, haemofiltration, or haemoperfusion; antioxidant therapy; or immunosuppressive therapy (Lavergne 2018).

Immunosuppressive therapy

Glucocorticoid drugs are usually used to reduce inflammation and to suppress the immune response. Glucocorticoids are a class of corticosteroid hormones that bind to glucocorticoid receptors. The activated glucocorticoid receptor‐glucocorticoid complex leads to the up‐regulation of the expression of anti‐inflammatory proteins. The glucocorticoids commonly used to treat paraquat poisoning are methylprednisolone and dexamethasone.

Cyclophosphamide is a broad‐spectrum immunomodulatory drug, usually used in the treatment of cancer and autoimmune disease.

Since the 1970s, glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide have been used in combination as a means of suppressing the inflammation responsible for pulmonary fibrosis (Eddleston 2003), and were endorsed as a successful treatment by Addo and Poon‐King (Addo 1986). The effectiveness of this treatment combination for paraquat poisoning remains unclear.

How the intervention might work

In animal studies, glucocorticoids such as dexamethasone have been shown to reduce lipid peroxidation and paraquat accumulation in the lungs (Dinis‐Oliveira 2006). Cyclophosphamide has a broad immunomodulatory effect.

Given the profound secondary inflammation seen in paraquat poisoning, particularly in the lungs where paraquat molecules actively accumulate, immunosuppression would appear to be a logical therapy for paraquat poisoning.

Why it is important to do this review

Though it has been inferred from experimental, Lee 1984, and clinical experience, Agarwal 2006, that immunosuppressive therapy might reduce deaths among paraquat‐poisoned patients, there is no consensus on the effectiveness of this treatment. Considering the potential hazards associated with immunosuppressive drugs (Winsett 2004) ‐ such as making patients more prone to infection ‐ an update of the previous Cochrane Review on this topic was due in order to revisit assessments of effectiveness and risk, support decision‐making and inform further research.

Objectives

To assess the effects of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide for moderate to severe oral paraquat poisoning.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs. We excluded any trials of a cross‐over design as this is incompatible with our review question. For RCTs published after 2010, we considered only prospectively registered RCTs to be eligible for this 2021 update, in accordance with Cochrane Injuries Group policy.

Types of participants

Any person of any age, diagnosed with oral paraquat poisoning (although poisoning via inhalation or contact with skin is possible, these were not foci of the review). The review focuses on participants with moderate to severe poisoning, given that generally in trials (as in clinical practice) individuals with mild cases of paraquat poisoning (which tend to resolve on their own) and those with extremely severe intoxication (see definition of 'fulminant' in both Description of the condition and Included studies) may not be treated; or, if they are treated, may not be analysed with other groups of participants, due to prognosis.

Types of interventions

Intervention: glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide, in combination.

Eligible comparators: placebo; standard care alone; or any alternative therapy in addition to standard care.

We excluded studies that focused on any single immunosuppressant (either a glucocorticoid drug or cyclophosphamide by themselves) or other combinations of therapies.

Types of outcome measures

Mortality at 30 days following the ingestion of paraquat.

All‐cause mortality at the end of the maximum follow‐up period recorded by investigators, as long as they are clinically compatible.

Otherwise we reported findings in the short term (typically at hospital discharge, which of necessity varied between participants), and longer term (three months after discharge in the one trial that reported any follow‐up), as appropriate.

New infections diagnosed within one week after initiation of treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

In order to reduce publication and retrieval bias we did not restrict our search by language, date, or publication status.

Search strategies with notes for this update are listed in Appendix 1. Search methods and strategies for previous versions of the review can be found in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Injuries Group's Information Specialists searched:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (which contains the Cochrane Injuries Trials Register) in the Cochrane Library (searched 21 September 2020);

Ovid MEDLINE(R), Ovid MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid OLDMEDLINE (1946 to 21 September 2020);

Embase Classic + Embase (OvidSP) (1947 to 21 September 2020);

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (1970 to 21 September 2020);

ISI Web of Science: SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, ESCI (2017 to 22 September 2020)

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (21 September 2020);

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled-trials.com/) (20 September 2020);

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (21 September 2020).

The following Chinese databases were searched by one review author (LL):

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI 数据库) (12 November 2020);

Wanfang Data (万方数据库) (12 November 2020);

VIP (维普数据库) (12 November 2020).

Searching other resources

We searched the internet through search engines google.com and baidu.com on 12 November 2020 using the term 'clinical trial & paraquat'. We also checked the reference lists of reports and systematic/literature reviews on paraquat poisoning for potentially relevant published or unpublished trials. We contacted the authors of the included trials for further information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the present version of the review, three review authors (LL, JD and HW) independently screened the search results from the English language databases. LL, CY and BC independently screened the results from the Chinese databases. We obtained and assessed the full‐text versions of potentially relevant trials. Duplicate reports were identified and noted.

Review authors LL and BC disagreed about the inclusion of the Afzali 2008 study due to the use of alternate allocation as the method of sequence generation. Review author CY moderated the discussion on inclusion of this trial, and in the last published version of this review (Li 2014), it was agreed that the trial would be included, but classified as being at high risk of bias. Following statistical advice in 2021, the author team as a whole decided once again to retain the trial, whilst highlighting issues to do with its interpretation, on the basis not only of design, but also due to investigator‐acknowledged failure to assess participants via plasma concentration.

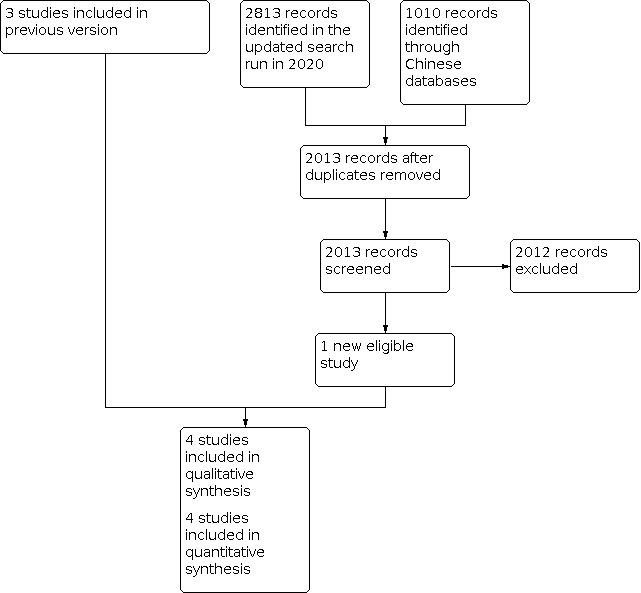

We identified one new study that met our eligibility criteria (Gawarammana 2017). A flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram for 2021 update

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (LL, BC, and JD) independently extracted the following data from the four included trials:

study design;

study setting (country, city, number of centres);

inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies;

number, gender, and severity of intoxication of participants in the intervention and control groups;

outcome data including number of deaths and infection cases assessed at each data collection point;

loss to follow‐up/withdrawals from analysis;

information on study conduct sufficient to assess risk of bias, including evidence of prospective trial registration for all studies published from 2010 onwards.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Four review authors (LL, BC, JD, and HW) independently evaluated the risk of bias for each included trial based on the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and any other sources of bias. We based our judgements on the criteria outlined in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed each domain as at low or high risk, or unclear risk if the information provided was insufficient to permit a judgement on a particular area of bias, or if it was unclear in which direction a bias might lead. Risk of bias judgements are provided in the risk of bias tables in Characteristics of included studies, and summaries of the judgements are given in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study

Measures of treatment effect

Where feasible, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). We summarised data for all‐cause mortality at final follow‐up in a meta‐analysis using a fixed‐effect model. When assuming a 75% and 65% mortality rate for control and treatment group respectively, with a level of significance of 5% and a power of 90%, we calculated that 439 participants would be required in each arm of a study to detect the effect sufficiently.

Unit of analysis issues

No unit of analysis issues arose within the current version of this review. We excluded cross‐over studies as inappropriate for our review question (given our focus on mortality). We identified no cluster‐RCTs and no trials with multiple eligible intervention (or comparator) arms.

Should the issue of clustering arise in future updates, we plan to use the methods detailed in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as applicable (Higgins 2021), based on information provided by investigators, including: the number of clusters (or groups) randomised or the average (mean) size of each cluster; and an estimate of the intracluster (or intraclass) correlation coefficient (ICC).

Should the issue of multiple eligible arms or comparator groups arise, we will consider appropriate methods including pooling data from eligible arms, or conversely treating a multiple‐arm study as two or more studies. In the latter case, we will take care to reduce the number of participants in the arm(s) left intact, in order to preserve the independence of findings.

Dealing with missing data

The amount of missing data in each trial was assessed, outcome by outcome, and any potential effects on results informed our risk of bias assessment (see Risk of bias in included studies) and GRADE ratings.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered possible causes of clinical heterogeneity (e.g. how studies measured severity of poisoning, treatment regimen, variation in standard care, length of follow‐up) when making decisions about whether to pool data.

Where possible and appropriate, we examined statistical heterogeneity using the Chi2 test and I2 statistic. For the outcome of mortality, we considered an I2 value of more than 50% as indicative of substantial heterogeneity, and acknowledged this in our interpretation of the data.

Assessment of reporting biases

Had we identified 10 or more eligible trials for this update, we would have investigated the possibility of reporting biases, including publication bias, by assessing funnel plots for asymmetry where 10 or more studies reported on the same outcome (Egger 1997). We acknowledge that asymmetry could be due to publication bias or to a genuine relationship between trial size and effect size. We also searched for evidence of prospective trial registration and trial protocols for all studies included in the review.

Data synthesis

Where feasible, we analysed data using Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2020). Where this was not feasible, we reported results narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Had there been sufficient studies, we would have performed subgroup analysis based on the treatment regimen used to investigate the impact on both mortality and adverse effects.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed post hoc sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of reporting bias in the Lin 1999 study, as well as on the effect of possible selection bias in the Afzali 2008 study (see Effects of interventions). These two studies also merited exclusion from sensitivity analyses because they were subject to bias based on lack of appropriate assessment of plasma paraquat levels on entry to the study, leading ultimately to our decision to present a sensitivity analysis for the outcome 'all‐cause mortality at final follow‐up: at hospital discharge' in Table 1.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We summarised our findings for all outcomes in Table 1.

We assessed the certainty of the evidence for each outcome measure using the GRADE approach (Yan 2016). GRADE is used to assess the certainty of evidence according to the following five domains: imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency, risk of bias, and publication bias. The certainty of evidence assessments are provided in Table 1 and were generated within the online tool GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT 2020).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The study selection process is outlined in Figure 1.

The English language electronic search retrieved a total of 2813 records across all years. We identified eight potentially relevant trials, four of which were eligible for inclusion in this update.

Review author LL identified a total of 1010 reports through a Chinese language search on Chinese language databases; none of these met our inclusion criteria.

Review author LL identified one report whilst searching google.com using the term 'clinical trial & paraquat', which was later excluded (Tsai 2009). We identified no additional eligible RCTs through screening reference lists or literature reviews.

Included studies

In this update, we included one new study (Gawarammana 2017), which resulted in a total of four included studies, with a combined total of 463 participants for analysis (Afzali 2008; Gawarammana 2017; Lin 1999; Lin 2006). See also Characteristics of included studies.

Design and setting

All of the included studies were reported as parallel RCTs; however, following contact with one trialist, it became clear that one study used quasi‐randomised methods to generate the sequence (Afzali 2008).

Two studies were conducted at a single site (a hospital in Taiwan, which featured a dedicated poison control centre) (Lin 1999; Lin 2006); one study took place at single site in Hamadan, Iran; and one study was a multisite RCT conducted at six district hospitals in Sri Lanka (Gawarammana 2017).

Sample sizes

No sample size calculation is mentioned in the text of Lin 1999, which reports data for 121 participants but retrospectively excluded those with fulminant poisoning who died within one week of intoxication (n = 71), leaving 50 participants. The same trialists reported for their later, smaller study (n = 23), which assessed a different treatment regimen, that an "a priori estimate of sample size for this study could not be performed because only case reports using the new treatment method were noted in previous literature" (Lin 2006). No sample size calculation is mentioned in the text of Afzali 2008 (n = 20). Investigators in Gawarammana 2017 (n = 299) did provide a sample size calculation, reporting: "In order to be able to detect whether either regimen increases survival from 18% to 28%, with a significance level (alpha) of 5% and a power of 80%, a minimum of 295 patients must be recruited to each arm of the trial (i.e. 590 patients in total)" (p 634). This recruitment objective was manifestly unmet due to the trial stopping early, which was sanctioned by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee because of a "collapse" in recruitment due firstly to restrictions on, and subsequently the banning of, paraquat use in Sri Lanka.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

All four included trials involved paraquat‐intoxicated individuals who had had their paraquat poisoning confirmed by sodium dithionite test. The included trials varied in the time period during which participants could be recruited. In both Lin 1999 and Lin 2006, participants had to present within 24 hours of ingestion of paraquat. No explicit criteria were given for presentation in the trial reported in Afzali 2008, but figures provided for mean time between poisoning and admission to hospital never exceeded seven hours. The largest and most recent trial reported inclusion criteria permitting recruitment up to 48 hours after ingestion (Gawarammana 2017).

As mentioned in Description of the condition and Types of participants, symptoms of paraquat ingestion are dose‐dependent, and intoxication is usually categorised as mild or 'low dose', moderate, or severe or 'high dose'. Mild cases tend to resolve without further sequelae and therefore trialists typically exclude such individuals when conducting trials of therapeutics. Similarly, where they can be identified, 'fulminant' participants who have ingested a dose likely to kill within 48 to 72 hours due to multiple organ failure are also typically excluded, if possible. Palliative care tends to be the recommended course for people in this category. Methods for assessing degree of intoxication evolved between the conduct of the oldest study in this review, Lin 1999, and the latest study, Gawarammana 2017. We considered these differential criteria for defining severely poisoned patients to be a potential source of clinical heterogeneity, and this was reflected in sensitivity analysis for mortality and in our GRADE assessments.

All of the included studies attempted to exclude severely poisoned patients who were expected to die imminently with little chance of responding to therapy: Gawarammana 2017 excluded severely poisoned patients with a Glasgow Coma Score of less than 8/15 or a systolic blood pressure less than 70 mmHg that did not respond to 1 L of intravenous fluid; Afzali 2008 only provided analysis for 20 of 45 participants screened for the trial, apparently not randomising 15 participants whose sodium dithionite reactions tests indicated their cases were too mild, and 10 participants considered fulminant; they specifically listed their failure to conduct plasma assessments as a study limitation.

The Lin 2006 trial only included participants with a predicted mortality of > 50% and ≤ 90% according to the Hart 1984 formula. Lin 1999 excluded all participants who died within one week of poisoning in what appears to be a post hoc decision (see Risk of bias in included studies), but which in fact leads to a population broadly in line with other studies included in this review. The authors of the Lin 1999 paper ‐ the oldest in the review ‐ defended their choice to analyse as they did by explaining that they were constrained at the time of recruitment "because no paper suggested an index to accurately predict the clinical severity of PQ [paraquat]‐poisoned patients up till now" (Buckley 2001).

Demographics

Although inclusion criteria, where specified, admitted the recruitment of adolescents from the age of 14, Gawarammana 2017, or 15, Lin 2006, the included participants tended to be adults, with means of 33 to 37 years of age in Lin 2006, 26 in Afzali 2008, 27 in Gawarammana 2017, and 27 to 37 in the two groups reported within Lin 1999. The majority of participants across trials (69%) were male.

Diagnostic certainty/severity

Two of the four included studies used the Severity Index of Paraquat Poisoning (SIPP), defined as plasma paraquat poisoning in mg/L multiplied by the number of hours since paraquat ingestion, as a means of assessing severity on arrival to hospital (Sawada 1988). By this measure, participants were comparable at baseline within Lin 2006 (mean values between 14 and 16), but investigators in Gawarammana 2017 reported a small but significant baseline difference in participants allocated to intervention (mean 18.4) compared to control (mean 13.1). Lin 1999, Lin 2006, and Afzali 2008 also reported urine colour (whether "dark blue" or "navy blue") and found groups comparable, although there is consensus in the field that only plasma tests are truly reliable. The authors of Afzali 2008 state lack of such testing in the "limitations" section of their paper; the authors of Lin 1999 did not, but they included such testing in their subsequent study (Lin 2006).

Interventions

All studies compared the use of standard care alone versus standard care and glucocorticoid (invariably methylprednisolone or dexamethasone, or both) with cyclophosphamide for individuals with paraquat poisoning. Gawarammana 2017 also provided normal saline as a placebo within the control group, which no other trial did.

Standard care

Standard care given to both groups was defined in Lin 1999 and Lin 2006 as including gastric lavage with normal saline followed by active charcoal added in magnesium citrate given through a nasogastric tube, courses of 8‐hour active charcoal haemoperfusion therapy and administration of intravenous dexamethasone. "Conventional treatment" within the small Afzali 2008 study was similar, including gastric lavage with normal saline, "charcoal‐sorbitol lavage every two to four hours for three days, forced alkalinised diuresis in the first day of admission to the hospital, and haemodialysis of four hours duration". This differed from Gawarammana 2017, where standard care was limited to intravenous fluid, activated charcoal, and pain relief.

Treatment regimens

The combinations of cyclophosphamide and glucocorticoid treatments in the four studies used pulse therapy administration (high doses daily over a short period of time, to maximise therapeutic effect whilst minimising toxicity).

Following gastric lavage, active charcoal and charcoal haemoperfusion therapy, the treatment arm in Lin 1999 received infusions of cyclophosphamide for two hours per day for two days, and methylprednisolone for two hours per day for three days; 10 mg dexamethasone was then administered every eight hours for 14 days. The treatment arm in Gawarammana 2017 was similar, except that the methylprednisolone was infused over one hour rather than two, and participants were given 8 mg dexamethasone daily for 14 days. The authors of Afzali 2008 reported a similar regimen (but without administration of dexamethasone), with cyclophosphamide infused in two hours for two days with methylprednisolone also infused for four hours, repeated over three consecutive days. Participants in the Afzali 2008 and Gawarammana 2017 trials also received MESNA (2‐mercaptoethane sulfonate sodium (Na)) to mitigate the effects of cyclophosphamide.

Lin 2006 had a more complex treatment regimen. Following the same initial pulse therapy of cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone described in Lin 1999, 5 mg dexamethasone was administered every six hours until the participant's partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) reached a certain threshold. Another pulse of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide (the latter only for one day, and only if it was more than two weeks since the previous cyclophosphamide dose) was repeated if physiological parameters fell below a certain threshold, indicating a poor outcome. Dexamethasone was then continued until the desired PaO2 was reached.

Outcomes

All of the included studies reported the primary outcome, mortality, at hospital discharge (Afzali 2008; Gawarammana 2017; Lin 1999; Lin 2006), and in one case, at three months after hospital discharge (Gawarammana 2017). No study reported on the outcome of infections (a known sequela of immunosuppression therapy), although two studies considered the related outcome of leukopenia (Lin 1999; Lin 2006). Afzali 2008 did not report on infections or on adverse events per se, but did confirm that no complications of treatment appeared by the time participants had been discharged. The fourth trial assessed participants for two specific potential adverse effects of treatment (haematuria, bladder pain) attributable to cyclophosphamide (Gawarammana 2017).

Study funding sources

Two studies did not report any source of funding (Afzali 2008; Lin 1999); one reported funding from a governmental body in Taiwan (Lin 2006). One study reported mixed sources of funding including charitable and research grants from the UK and Australia as well as support from Syngenta, a manufacturer of herbicides including paraquat (Gawarammana 2017).

Excluded studies

We excluded four trials: one trial with uncertain sequence generation that assessed the effects of methylprednisolone only (Tsai 2009); one trial that used a historical control (Perriens 1992); and two potentially eligible studies that were not preregistered as required by the Cochrane Injuries Group for studies published after the year 2010 (Chen 2014; Ghorbani 2015).

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed Lin 2006 to be at low risk of bias across most domains. Lin 1999 randomised all urine‐positive patients, but presented the outcomes for those who died within one week of poisoning separately from those who survived longer. Presenting the data separately to exclude very severely poisoned people is reasonable given the specific clinical features of paraquat poisoning, but this post hoc decision introduces the risk of selective reporting. The small trial conducted by Afzali 2008 was poorly reported, but personal communication with the authors permitted some judgements with respect to risk of bias, which was frequently assessed as high risk because of the method of sequence generation. Gawarammana 2017 was a well‐conducted, preregistered multicentre RCT that was underpowered due to stopping early. Our risk of bias judgements are recorded in the risk of bias tables in Characteristics of included studies and displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Allocation

Lin 2006 reported an appropriate method of sequence generation and allocation concealment using a sequence of labelled cards in sealed envelopes that were prepared by a statistical advisor. Gawarammana 2017 used computer programs to generate the random sequence by an IT consultant, and the allocations were conducted by the pharmacist and concealed from other members of the team. Lin 1999 generated the randomisation sequence using a random numbers table, but there was no mention of allocation concealment, so we judged this to be at unclear risk of bias.

Afzali 2008 used alternate allocation as a method of sequence generation, which obviates concealment of allocation and under normal circumstances would call for an assessment of high risk of bias and exclusion of the study in sensitivity analysis, if the trial were to be included in the review at all. After discussion with the Cochrane Injuries statistician, we revised our assessment to unclear risk, given that the pace of recruitment (just 20 eligible participants across 25 months) reduced the risk of manipulation of the allocation of any given participant to a particular group.

Blinding

In Gawarammana 2017, the pharmacist allocated participants and prepared identical treatment packs of both active treatment and placebo, protecting team members and participants from awareness of allocation.

In Lin 1999 and Lin 2006, the statistician who contributed to the trial report was blinded to the allocation. Treating physicians and participants were not blinded, nor could they be, as there was no placebo. Given that the primary outcome is death, this may not constitute a significant risk of bias. We therefore judged the risk of bias for blinding as low in this version of the review, instead of high as in previous versions, but considered the lack of blinding to be an issue when performing the GRADE assessment for the outcome of infection.

Investigators involved in the Afzali 2008 trial confirmed by personal correspondence that no blinding was attempted of any of the staff involved in the trial (nor could they be, with no placebo in use). As with Lin 1999 and Lin 2006, we believe this does not constitute a high risk of bias for the objective outcome used in our review (mortality at discharge).

Incomplete outcome data

Our main outcome of interest was mortality, which was reported in full in all studies either at hospital discharge or at six weeks. In Gawarammana 2017, the primary result, in‐hospital death, was reported for all 299 randomised participants, as well as follow‐up at three months after hospital discharge, by which time only six participants had been lost to follow‐up, two out of 152 (1.3%) from the control group and four out of 147 (2.7%) from the treatment group. Given the high risk of death (65% in treatment group and 75% in control group), we judged the potential impact of the loss of outcome data on the risk of attrition bias to be small.

Selective reporting

We identified no suggestion of selective reporting in Gawarammana 2017, as it was prospectively registered and appears to have reported methods and data in full as planned, up to the time of stopping prematurely (see below).

Lin 2006 appears to have reported on all relevant outcomes, but in the absence of a prospective registration or a trial protocol, and in compliance with the Cochrane Injuries Group policy (2015), we must assess the risk of selective outcome reporting as (at best) unclear whenever no prospective plans are made public.

Lin 1999 randomised 121 participants, but made what appears to be a post hoc decision to exclude 71 of these participants following treatment, based on the very severe nature of their poisoning. Although the clinical decision to exclude these fulminant patients seems sensible given the predictable course of very severe paraquat poisoning ‐ which was done in all four included studies ‐ the criteria by which these patients were defined (death within a week) and the post hoc nature of the decision leaves the study open to reporting bias. Nevertheless, we believe we have obviated the risk of bias from selective reporting by presenting data for both groups and by using sensitivity analysis. However, as there is no evidence of prospective reporting and no identifiable protocol, we are again obliged to report the risk of bias for this domain to be unclear.

Afzali 2008 was a small study reported in a very short paper, with virtually no information on study conduct and a lack of clarity on the screening and allocation process. Some relevant information was acquired by personal correspondence to which an author on a previous version of this review has lost access. In view of this, and in the absence of a prospective registration or a trial protocol, and in compliance with the Cochrane Injuries Group policy, we must assess the risk of selective outcome reporting as at best unclear whenever no prospective plans are made public.

Other potential sources of bias

The Gawarammana 2017 trial was stopped early "after consultation with the data monitoring and ethics committee due to a collapse in recruitment" following the phasing out and eventual banning of paraquat in Sri Lanka, where the trial was being conducted. However, since the reason for stopping early was unrelated to the observed intervention effect, we do not deem this to be a source of bias. The same trialists reported a small baseline difference in the median SIPP score of participants allocated to intervention (median 18.4) compared to control (median 13.1). As the method of randomisation was unlikely to have been compromised (it was done using purpose‐designed software), this difference is likely to have been caused by chance alone, and is therefore not considered to be a source of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Mortality at 30 days following the ingestion of paraquat

None of the included studies assessed this outcome.

All‐cause mortality at the end of the follow‐up period

See Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All‐cause mortality, outcome: 1.1 All‐cause mortality

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1.2 Sensitivity analysis: all‐cause mortality at final follow‐up: including fulminant (and excluding Afzali 2008 due to risk of selection bias)

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 All‐cause mortality, outcome: 1.3 Sensitivity analysis: all‐cause mortality: excluding studies without plasma paraquat assessment at baseline

All‐cause mortality (in hospital)

The primary analysis suggests that participants who receive glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may have lower mortality in hospital than those who received standard care alone (risk ratio (RR) 0.73, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.88; 4 studies; 392 participants). Statistical heterogeneity for this result was substantial (I2 = 70%) (Analysis 1.1). There was also some clinical heterogeneity relating to participant inclusion criteria: Lin 1999 randomised 121 participants, but made what appears to be a post hoc decision to exclude 71 following treatment, given that they died within a week due to the very severe nature of their poisoning.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: All‐cause mortality, Outcome 1: All‐cause mortality

We thus had serious concerns about the possibility of selection bias, and to investigate, we performed an exploratory post hoc sensitivity analysis to re‐include the 71 fulminant participants from Lin 1999. With the fulminant participants included, the estimated effect of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care was reduced to a less clear effect (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.93; 463 participants). (Analysis 1.2). This was expected, given that fulminant patients will almost inevitably die irrespective of treatment (WHO IPCS 2009; Gawarammana 2017). Heterogeneity remained substantial (I2 = 53%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: All‐cause mortality, Outcome 2: Sensitivity analysis: all‐cause mortality re‐including fulminant participants

We also elected to perform a second previously unplanned sensitivity analysis, excluding all participants from both the Lin 1999 and Afzali 2008 trials, on the grounds that they stood out amongst the included trials by not using SIPP methods at baseline. The results left two studies with combined results suggesting that there may be a small benefit of the intervention on the outcome of mortality (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.99; participants = 322) (Analysis 1.3). The I2 of 77% indicates that only the smaller study (Lin 2006, n = 23) with just seven participants in the control group showed benefit, whilst the larger trial (Gawarammana 2017) found none. We chose to present the latter results as our main analysis for the purposes of GRADE, and judged the certainty of the evidence to be low, downgrading twice for imprecision and inconsistency (Analysis 1.3; Table 1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: All‐cause mortality, Outcome 3: Sensitivity analysis: all‐cause mortality: excluding studies without plasma paraquat assessment at baseline

All‐cause mortality (long term ‐ three months after discharge from hospital)

Low‐certainty evidence suggests that there may be little or no difference in mortality at three months after discharge from hospital between participants who received glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care and those who received standard care alone (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.13) (Analysis 1.1). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence for imprecision (the total number of participants across the included studies fell short of the optimal information size) and for indirectness (which we defined as uncertainty with regard to the interpretation of long‐term mortality data in a population where injury is sustained as a result of self‐harm).

New infection diagnosed within one week after initiation of treatment

Two of the four included trials assessed the outcome of infection (Lin 1999; Lin 2006). Neither study reported any new infections diagnosed within one week after initiation of methylprednisolone and cyclophosphamide. Lin 1999 reported the related outcome of leukopenia in 8 of 22 participants (36.4%) in the intervention arm. These participants spontaneously recovered one week later, with no mortality. Lin 2006 reported leukopenia in 6 of 16 participants (37.4%) in the intervention arm, all of whom recovered within one to two weeks. There were no reports of leukopenia in the control groups.

Afzali 2008 and Gawarammana 2017 measured neither infection nor leukopenia. As this outcome was reported by only two small trials, and since we have concerns about reporting bias in the larger of the two trials, we downgraded for serious imprecision and risk of bias for this outcome, assessing the evidence to be of very low certainty.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review update includes four trials with a combined total of 463 participants who had moderate to severe paraquat poisoning. Low‐certainty evidence from two trials indicates that participants who received glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may have a slightly lower risk of death than those receiving standard care alone in the short term (at hospital discharge). We chose the results of a sensitivity analysis as the main analysis for this outcome, conceding that the lack of plasma testing at baseline rendered the results of two studies unreliable. Heterogeneity was high, as one small study found a large benefit whilst the other (the largest and best conducted within the review) found none. The same single, large study provided low‐certainty evidence of little or no effect of treatment on mortality at three‐month follow‐up after discharge from hospital.

We are uncertain about the effects of glucocorticoids with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care on infection risk within one week of treatment. Two trials recorded leukopenia in just over one‐third of participants in the treatment arm, all of whom recovered within two weeks and none progressed to a diagnosed infection. We assessed the evidence for this outcome to be of very low certainty.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The completeness of the evidence for the effects of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide for paraquat‐poisoned patients is limited by the fact that we were only able to include four RCTs, three of which were small, and the largest of which was still underpowered due to trial termination. Differing inclusion criteria regarding severity of paraquat poisoning, leading to concerns about clinical heterogeneity, was also an issue (see Quality of the evidence).

With regard to representation of populations most affected by this condition, trials are relatively restricted, having only been conducted in China (two studies), Iran (one study), and Sri Lanka (one study), and the context of recruitment may well have changed since the time when these studies were conducted (range 1997 to 2010). The mean age of participants was in the upper 20s, and the vast majority of participants were male. Since poisoning as a means of attempting suicide is most prevalent in older age groups in many countries (e.g. China and Korea), this review is limited in its applicability to this population (Wang 2019). This is particularly important since age can increase physiological susceptibility to the effects of pesticides (Ginsberg 2005).

One consideration of our results is that this effect estimate applies only to moderate to severe cases of poisoning: mild cases with a negative urine dithionite test were excluded, as were very severe cases. This makes clinical sense, as mild cases tend to make a complete recovery with only mild symptoms, whilst very severe cases of fulminant poisoning are expected to die imminently and have little chance of responding to therapy (WHO IPCS 2009).

Quality of the evidence

We judged two of the four included studies to be at low risk of bias for key domains, including the largest of the three trials (Gawarammana 2017, n = 299). Although three trials, Afzali 2008, Lin 1999 and Lin 2006, did not use a placebo, we did not consider this to be a major source of bias since our main outcome of interest was mortality. We assessed Lin 1999 to be at unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment, as this was not mentioned in the trial report. This study randomised 121 participants regardless of the severity of poisoning, and data on mortality were presented in full. However, the trialists made what appears to be a post hoc decision to exclude very severely poisoned participants ("fulminant", n = 71) from the final analysis. We performed a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of including these participants in the final analysis. The effect estimate was reduced, as would be expected given that people with fulminant paraquat poisoning are likely to die imminently irrespective of treatment. The Afzali 2008 trial was small and poorly reported, but considering that its use of alternate allocation was unlikely to seriously bias results given the slow pace of recruitment, we included data from this study. We further conducted sensitivity analysis to consider the impact of diagnostic uncertainty, as noted below.

Our meta‐analyses revealed substantial statistical heterogeneity, therefore we downgraded the certainty of evidence accordingly. There were several possible sources for this heterogeneity, as follows.

Differing inclusion criteria regarding severity: Lin 1999 did not employ plasma testing, and also retrospectively excluded participants who died within a week. Lin 2006 only included participants with a predicted mortality of > 50% and ≤ 90% according to the Hart 1984 formula. Afzali 2008 did not use SIPP values and provided limited detail on inclusion criteria other than that "mild" and "fulminant" cases were excluded. Gawarammana 2017 excluded severely poisoned people with a Glasgow Coma Score of less than 8/15 or a systolic blood pressure less than 70 mmHg.

Variation between treatment arms across trials: dosages and infusion times varied; the Afzali 2008 regimen did not include dexamethasone, unlike the other three studies.

Variation between standard care arms across trials: Gawarammana 2017 limited standard care to intravenous fluid, activated charcoal, and pain relief, whilst Lin 1999 and Lin 2006 included gastric lavage with normal saline followed by active charcoal added in magnesium citrate given through a nasogastric tube, courses of 8‐hour active charcoal haemoperfusion therapy and administration of intravenous dexamethasone. It is possible that there was a synergistic interaction between one of these elements of standard care in the Lin trials, when combined with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide, as suggested by Xu 2019.

The sample size for this review fell short of the 429 participants required in each arm of the study, therefore we downgraded the certainty of evidence to reflect this imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

This review was conducted according to predefined inclusion criteria and methodology to select and appraise eligible studies. The search for trials was extensive, and was conducted on both English and Chinese language databases. Publication bias is a consideration in any systematic review. Although only four trials were included in the review, we believe that given the extent of the search for trials, these were the only eligible RCTs addressing this research question at the time of the search. We excluded two studies because they were not prospectively registered and therefore did not meet the Cochrane Injuries Group inclusion criteria for studies conducted after the year 2010.

We differed from the authors of previous updates and used the data as analysed in Lin 1999, in which the trialists, following completion of the trial, excluded participants with very severe fulminant poisoning from their analysis. Whilst we acknowledge that this introduces a high risk of selection bias, we considered that it made better sense clinically to exclude these participants, since people with fulminant poisoning are very unlikely to respond to any therapy, and the other studies also excluded these participants. We accounted for this high risk of selection bias in our GRADE assessment, and undertook sensitivity analysis. If there are sufficient data in future updates of this review, we will perform subgroup analysis according to severity of poisoning.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The authors of the largest and best‐conducted study included in this review, Gawarammana 2017, appear to be sceptical of any real benefit of the treatment regimen they studied. Based on their experience and their assessment of other literature in the field, they concluded that it is likely that "any possible benefit" of the glucocortoid/cyclophosphamide combined treatment "is due to the dexamethasone component rather than high‐dose immunosuppression. We believe clinical research efforts would be best spent on exploring the optimal dose of dexamethasone and other inexpensive and low toxicity antidotes with favourable effects in animal studies (for example acetylcysteine)" (Gawarammana 2017, p 639, emphasis added).

This is in considerable contrast to the findings of two recently published systematic reviews, whose authors conclude that "immunosuppressive pulse therapy can efficiently reduce the mortality of PQ [paraquat] poisoning and is relatively safe" (Xu 2019, p 588), and that immunosuppressive drugs generally "may reduce the mortality and incidence rate of MODS [multiple organ dysfunction syndrome] in moderate to severe PQ poisoning patients, and severe PQ poisoning patients might benefit more from ISDs [immunosuppressant drugs]" (Gao 2020). However, both systematic reviews had markedly different inclusion criteria to our review, including results from many non‐randomised studies, as well as one recent RCT that we excluded because there was no evidence of preregistration. Furthermore, Xu 2019 unaccountably omits results from the largest study included within this review (Gawarammana 2017).

The findings of our review align more closely with those of Gawarammana 2017 itself, for obvious reasons. We believe their trial, and our review, provide low‐certainty evidence that participants who received glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may have little reduction in mortality compared to those receiving standard care alone at hospital discharge, and little or no effect at three months after discharge from hospital. We considered longer‐term data as more equivocal than shorter‐term data, believing it to be possible that the special circumstances of this type of injury (paraquat is normally ingested in quantities seen in the included studies as a method of self‐poisoning) render any interpretation of longer‐term data difficult, as factors other than the intervention may have a greater impact on the long‐term well‐being and survival of patients.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Low‐certaintly evidence indicates that glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide in addition to standard care may have a small effect on mortality in people with moderate to severe paraquat poisoning during hospitalisation, however, there appears to be little or no effect at three months post hospital discharge. Our confidence in the evidence is limited by the small number of participants contributing reliable data and the heterogeneity of results across studies. We are uncertain about the potential of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide to increase the risk of infection due to limited evidence.

Implications for research.

To enable further study of the effects of glucocorticoid with cyclophosphamide for individuals with moderate to severe paraquat poisoning, hospitals may provide this treatment as part of a randomised controlled trial with appropriate allocation concealment. All future research should be prospectively registered, CONSORT‐compliant, and investigators should make rigorous efforts to ensure an adequate sample size as well as seek long‐term follow‐up of participants, including on adverse events. In research contexts, no participant should be recruited without an assessment of plasma for time‐adjusted paraquat concentration being conducted.

Since the drafting of the protocol for this review in 2009, other trials have been conducted to assess the effects of glucocorticoids in combination with other treatments, such as haemoperfusion. Use of other treatment options such as therapy with high‐dose, long‐term antioxidant free radicals is also increasing. We aim in future updates to conduct a network meta‐analysis in an effort to determine the most effective therapy ‐ or combination of therapies ‐ for paraquat poisoning.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 June 2021 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Review updated with a search date of 21 September 2020 and one new study added. |

| 12 November 2020 | New search has been performed | The search has been updated to 21 September 2020. This update includes four studies. One study has been added since the previous published version of this review (Gawarammana 2017). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2009 Review first published: Issue 6, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 November 2020 | Amended | Jane Dennis has been added as an author for this update. |

| 12 December 2019 | Amended | Helen Wakeford was added as an author for this update. |

| 12 December 2019 | Amended | Helen Wakeford was added as an author for this update. |

| 20 July 2019 | Amended | We added the outcome 'new infections within one week after initiation of the treatment' (adverse effect of treatment). |

| 20 July 2019 | Amended | Emma Sydenham is no longer an author for this update. |

| 20 July 2019 | Amended | Deirdre Beecher is no longer an author for this update. |

| 25 May 2012 | New search has been performed | The search has been updated to 1 February 2012. No new studies were identified. The results and conclusions remain the same. |

| 24 May 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The search has been updated, but no new studies were identified. The results and conclusions remain the same. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen Blackhall for providing the search strategy and the search of English language databases for previous versions of this review. We thank Xi Lv for searching Chinese language databases in 2012. We thank Iris Gordon for help with search processing with English language databases. We thank Marialena Trivella for statistical peer review, and Elizabeth Royle for managing the editorial process. We thank peer reviewers Dr James Coulson (Cardiff University/Cardiff & Vale University Health Board, UK), Prof Narcisse Elenga (University of French West Indies/Cayenne General Hospital, French Guiana), Harrison Davies, and Danial Sayyad for their constructive comments, which we believe improved this manuscript profoundly.

This project was supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research, through Cochrane Infrastructure funding to the Cochrane Injuries Group. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies for update searches run in 2017 and 2020

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) 1946 to September 21, 2020 1 exp Herbicides/ 2 exp Paraquat/ 3 (Paraquat or (methyl adj3 viologen) or Dimethyl* or gramoxone or grammoxone or paragreen or Herbicide* or Pyridinium compound* or pathclear or weedol).mp. 4 1 or 2 or 3 5 exp Glucocorticoids/ 6 glucocorticoid*.ab,ti. 7 exp Cyclophosphamide/ 8 (cyclophosphamid* or carloxan or clafen or cycloblastin or cycloblastine or cyclofos amide or cyclofosfamid or cyclofosfamide or cyclophosphan*or cycloxan or cyphos or cytophosphan* or cytoxan or endocyclo phosphate or endoxan* or enduxan or genoxalor mitoxan or neosan or neosar or noristan or nsc 26271 or nsc 2671 or b‐518 or procytox* or semdoxan or sendoxan).ab,ti. 9 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 10 4 and 9 11 randomi?ed.ab,ti. 12 randomized controlled trial.pt. 13 controlled clinical trial.pt. 14 placebo.ab. 15 clinical trials as topic.sh. 16 randomly.ab. 17 trial.ti. 18 Comparative Study/ 19 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 20 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 21 19 not 20 22 10 and 21

EMBASE 1980 to 2020 Week 38 1 exp Herbicide/ 2 exp Paraquat/ 3 exp pyridinium derivative/ 4 (Paraquat or (methyl adj3 viologen) or Dimethyl* or gramoxone or grammoxone or paragreen or Herbicide* or Pyridinium compound* or pathclear or weedol).mp. 5 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6 exp Glucocorticoids/ 7 glucocorticoid*.ab,ti. 8 exp Cyclophosphamide/ 9 exp cyclophosphamide derivative/ 10 (cyclophosphamid* or carloxan or clafen or cycloblastin or cycloblastine or cyclofos amide or cyclofosfamid or cyclofosfamide or cyclophosphan*or cycloxan or cyphos or cytophosphan* or cytoxan or endocyclo phosphate or endoxan* or enduxan or genoxalor mitoxan or neosan or neosar or noristan or nsc 26271 or nsc 2671 or b‐518 or procytox* or semdoxan or sendoxan).ab,ti. 11 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 12 5 and 11 13 exp Randomized Controlled Trial/ 14 exp controlled clinical trial/ 15 exp controlled study/ 16 comparative study/ 17 randomi?ed.ab,ti. 18 placebo.ab. 19 *Clinical Trial/ 20 exp major clinical study/ 21 randomly.ab. 22 (trial or study).ti. 23 13 or 14 or 15 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 24 exp animal/ not (exp human/ and exp animal/) 25 23 not 24 26 5 and 11 and 25 27 limit 26 to embase 28 limit 27 to yr="2017 ‐ 2021"

WEB OF SCIENCE. SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, ESCI (2017 to 22 September 2020)SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI‐S, CPCI‐SSH, ESCI (all years to 21 Sept 2020) # 3#2 AND #1 Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=2017‐2020 # 2TS=(cyclophosphamid* or carloxan or clafen or cycloblastin or cycloblastine or cyclofos amide or cyclofosfamid or cyclofosfamide or cyclophosphan*or cycloxan or cyphos or cytophosphan* or cytoxan or endocyclo phosphate or endoxan* or enduxan or genoxalor mitoxan or neosan or neosar or noristan or nsc 26271 or nsc 2671 or b‐518 or procytox* or semdoxan or sendoxan) Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=2017‐2020 # 1TS=(Paraquat or Dimethyl* or gramoxone or grammoxone or paragreen or Herbicide* or pathclear or weedol or Pyridinium compound*) or TS=(methyl same viologen) Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, CPCI‐S Timespan=2017‐2020

CENTRAL (searched 21 September 2020) #1 MeSH descriptor: [Herbicides] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Paraquat] explode all trees #3 (Paraquat or (methyl near/3 viologen) or Dimethyl* or gramoxone or grammoxone or paragreen or Herbicide* or Pyridinium compound* or pathclear or weedol):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #4 #1 or #2 or #3 #5 MeSH descriptor: [Glucocorticoids] explode all trees #6 (cyclophosphamid* or carloxan or clafen or cycloblastin or cycloblastine or cyclofos amide or cyclofosfamid or cyclofosfamide or cyclophosphan*or cycloxan or cyphos or cytophosphan* or cytoxan or endocyclo phosphate or endoxan* or enduxan or genoxalor mitoxan or neosan or neosar or noristan or nsc 26271 or nsc 2671 or b‐518 or procytox* or semdoxan or sendoxan):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched) #7 MeSH descriptor: [Cyclophosphamide] explode all trees #8 #5 or #6 or #7 #9 #4 and #8

Chinese databases were searched using the general strategy: Paraquat AND cyclophosphamide AND lung in abstracts, with synonym expansion, and publication time from 2014 to 2020.

CNKI: 检索范围: (摘要%百草枯) AND (摘要%环磷酰胺) AND (摘要%肺) 资源范围: 总库;同义词扩展;时间范围:发表时间:2014‐04‐01到2020‐11‐12;

WAN FANG DATA: 更新时间: 不限万方:检索表达式:百草枯 * 环磷酰胺 * 肺 * Date:2014‐2020

VIP: 文摘=百草枯AND文摘=环磷酰胺AND文摘=肺 AND 年份:2014‐2020

Translation:

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI): (Abstract % paraquat ) AND (Abstract% cyclophosphamide ) AND (Abstract % lung). All databases; synonym expand; Time: from 2014‐04‐01 to 2020‐11‐12.

WAN FANG DATA: paraquat*cyclophosphamide*lung*Date: 2014‐2020.

VIP: Abstract=paraquat AND Abstract=cyclophosphamide AND Abstract=lung AND year: 2014‐2020.

Appendix 2. Search strategies 2014 update

For this update the search strategies were modified: the terms relating to lung were removed and the RCT filters were added. The strategies, as they were, did not retrieve the included studies even though they were indexed in MEDLINE and /or Embase. The included studies may have been retrieved either by screening reference lists.The added study filter is a modified version of the Ovid MEDLINE Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2011); for Embase we added to the search strategy study design terms as used by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011).

Other strategies for databases in the English language were not modified.

Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register

#1 ((Paraquat or (methyl and viologen) or Dimethyl* or gramoxone or grammoxone or paragreen or Herbicide* or "Pyridinium compound" or pathclear or weedol)) AND ((cyclophosphamid* or carloxan or clafen or cycloblastin or cycloblastine or "cyclofos amide" or cyclofosfamid or cyclofosfamide or cyclophosphan* or cycloxan or cyphos or cytophosphan* or cytoxan or "endocyclo phosphate" or endoxan* or enduxan or "genoxalor mitoxan" or neosan or neosar or noristan or "nsc 26271" or "nsc 2671" or b‐51)) [REFERENCE] [STANDARD]