Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Policies and practices that promote advance care planning and advance directive completion implicitly assume that patients’ choices for end-of-life (EOL) care are stable over time, even with changes in health status.

OBJECTIVE

To systematically evaluate the evidence on the stability of EOL preferences over time and with changes in health status.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

We searched for longitudinal studies of patients’ preferences for EOL care in PubMed, EMBASE, and using citation review. Studies restricted to preferences regarding the place of care at the EOL were excluded.

FINDINGS

A total of 296 articles were assessed for eligibility, and 59 met inclusion criteria. Twenty-four articles had sufficient data to extract or calculate the percentage of individuals with stable preferences or the percentage of total preferences that were stable over time. In 17 studies (71%) more than 70% of patients’ preferences for EOL care were stable over time. Preference stability was generally greater among inpatients and seriously ill outpatients than among older adults without serious illnesses (P < .002). Patients with higher education and who had engaged in advance care planning had greater preference stability, and preferences to forgo therapies were generally more stable than preferences to receive therapies. Among 9 of the 24 studies (38%) assessing changes in health status, no consistent relationship with preference changes was identified.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Considerable variability among studies in the methods of preference assessment, the time between assessments, and the definitions of stability preclude meta-analytic estimates of the stability of patients’ preferences and the factors influencing these preferences. Although more seriously ill patients and those who engage in advance care planning most commonly have stable preferences for future treatments, further research in real-world settings is needed to confirm the utility of advance care plans for future decision making.

Advance care planning may improve concordance between the care patients receive near the end of life (EOL) and the care they desire. The promise of advance care planning is suggested by evidence that approximately one third of Americans die in the following unenviable position: a decision needs to be made about the use or nonuse of life support, yet the patients’ diseases have progressed to where they cannot choose for themselves.1 However, the promise of advance care planning, and written advance directives (ADS) in particular, is predicated on the assumption that patients’ stated preferences when enacting their plan or directive will still be applicable at the time decisions must be made.

In a recent systematic review of the stability of patients’ preferences for dying at home, Gomes et al2 found that most people prefer dying at home and that 80% of patients do not change these preferences as illness progresses. However, systematically assembled data are lacking with regard to stability of preferences for other aspects of EOL care. Consequently, physicians and families may be uncertain as to how frequently to discuss EOL preferences with patients and how to interpret an AD or advance care plan enacted some time ago. We therefore conducted a systematic review to address the stability of patients’ EOL preferences over time and to identify patient characteristics associated with preference changes.

Methods

Design

We prospectively registered this systematic review with PROSPERO (registration No. CRD42012003139). The PRISMA checklist is available in eFigure 1 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement.

Search Strategy

In November 2012, we searched for primary studies in PubMed and EMBASE databases, using search terms chosen in consultation with research librarians (eTable 1 in Supplement). Results were restricted to the English language. Literature searches were repeated just before final analyses in June 2013, and further studies were retrieved for inclusion. We did not restrict searches by publication date or study design because we anticipated that few high-quality studies of any single design would be available. We hand-searched reference lists of all identified manuscripts for additional articles of relevance.

Selection Criteria

To be eligible, studies had to report original data on EOL treatment preferences at least twice, with assessments separated by at least 1 week or by a change in clinical status. From this set, additional studies were excluded if they (1) did not explicitly measure or record EOL treatment preferences, (2) conducted the study primarily to validate an instrument, or (3) restricted their assessments to preferences regarding place of care or place of death (as this more focused question was addressed by a prior review2). Intervention studies were eligible if they met all criteria and measured patients’ baseline preferences.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted and managed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform3 under the following headings: general information (country of origin, funding source), study characteristics (study design; study population; sample size; frequency, timing, and method of data collection), patient characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, medical history, education, socioeconomic status, prior exposure to ADS or EOL planning), measurements (preference assessment method, specific treatment preferences queried, format of patients’ responses), results (data required to calculate preference change or stability, predictors of change), and authors’ conclusions. Two of us abstracted data independently for all articles (C.L.A. abstracted data for all articles, R.B. and S.N. each abstracted data for half of the articles); disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Synthesis

We describe included studies in terms of country of origin, populations, design, methods of preference assessment (outlining specific treatment preferences when available), and year of publication. Main results were presented differently in various studies. Some authors calculated the percentage of all expressed preferences by all patients that were stable over time. Others calculated the percentage of patients with stable preferences.

Owing to heterogeneity of study populations, specific preferences elicited, and frequency and interval of assessments, we did not calculate summary effect estimates across studies. Instead, we graphically depict degree of stability across studies and discuss outlying studies in narrative form.

To supplement narrative presentations, we assessed unadjusted relationships between study-level factors and preference stability by grouping studies into categories and generating summary proportions for the total number of patients with stable preferences and the total preferences elicited that were stable with time. We then compared these values using X2 analysis. Differences were considered significant for P < .05. We also describe associations between specific patient characteristics and stability of preferences for all patient characteristics examined in at least 3 studies.

Results

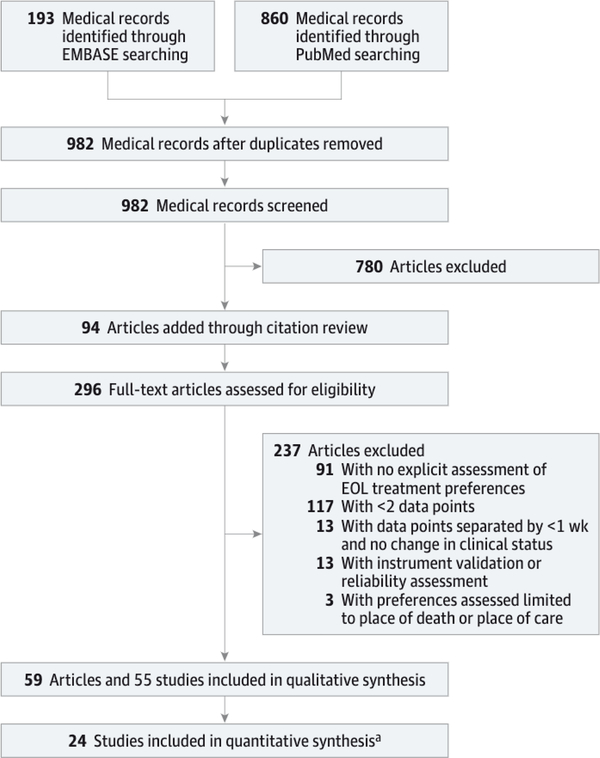

Initial searches of PubMed and EMBASE yielded 982 unique articles. Review of abstracts yielded 202 articles potentially eligible for inclusion. An additional 94 articles were identified by citation review, resulting in a total of 296 articles reviewed in full. After applying exclusion criteria to these 296 articles, 59 articles, reporting 55 distinct studies, were retained (Figure 1). Three articles presented data from the same large study: 2 used the same data set but analyzed different outcomes (these were considered as 1 study and the data merged together),4,5 and 1 used a separate data set in a subset of the larger population (considered separately).6 Three articles presented data from the same study with differences in how data were analyzed (considered as 1 study and merged together).7–9 Two articles presented data from the same population but focused on different outcomes (considered as 1 study and merged together).10,11

Figure 1. Flow of Studies Through the Review Process.

The flow of studies through the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process modeled after the PRISMA flow diagram.

aThe remaining 31 studies did not contain sufficient data to extract or calculate the percentage of individuals with stable preferences for specific treatments or the percentage of total stable preferences over time.

Description of Studies

The 55 studies included in qualitative synthesis reported changes in preferences among 16 870 individuals from 12 different countries. Participants included 10 431 patients with specific diseases; 6254 older, healthy adults (age ≥60 years); and 185 young, healthy adults (age <60 years). Sixty-two percent of the studies (36) were conducted in the United States, and 22% (13) were conducted in 8 European countries.

Most studies (42[76%]) focused on preferences of patients with specific conditions. The most common conditions among diseased cohorts were advanced cancer, advanced heart failure, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or AIDS. Studies of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, severe depression, advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and end-stage renal disease were also identified.

Methods of Preference Assessment

Data on patients’ preferences were assessed primarily using in-person questionnaires (52 studies [95%]). Seven studies (13%) used telephone interviews to supplement in-person questionnaires. Two studies (4%) combined mailed surveys with in-person questionnaires, and 2 studies (4%) used all 3 methods of data collection. One study (1%) used exclusively tele-Phone interviews, and 1 (1%) used exclusively mailed surveys. Two studies (4%) extrapolated patients’ preferences from medical records (1 in addition to in-person questionnaires). The number of preference assessments varied among studies from 2 to 10 assessments per patient. The time between the first 2 preference assessments ranged from 12 hours to 7 years (median, 6 months; interquartile range [IQR], 2.3–12.0 months), and the elapsed time between initial and final assessments ranged from 2 weeks to 7 years (median, 12 months; IQR, 3.4–14.6 months). Fifty-three of the 55 studies (96%) provided data on participation rates. Among these, participation rates ranged from 25% to 98.6% (median, 70.5%; IQR, 56.7%−84.7%).

Thirty-seven of the 55 articles (67%) assessed patients’ preferences for discrete medical treatments. The most frequently assessed treatment preferences were cardiopulmonary resuscitation (32 articles), artificial nutrition (21), mechanical ventilation (15), surgery (11), antibiotics (8), and dialysis (8). Other treatments included invasive diagnostic procedures, blood transfusion, hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and nursing home admission. Eighteen studies (33%) explored topics such as will to live, attitudes toward euthanasia or physician assisted suicide, and decision-making preferences.

Stability of Treatment Preferences

Fourteen studies reporting on 2353 patients did not provide enough information to extract or calculate the percentage of patients with stable preferences. Eighteen studies reporting on 5558 patients evaluated general preferences that did not entail specific medical treatments (eg, attitudes toward euthanasia, decision-making preferences). For clarity, we present these studies separately in eTable 2 and eTable 3 in the Supplement.

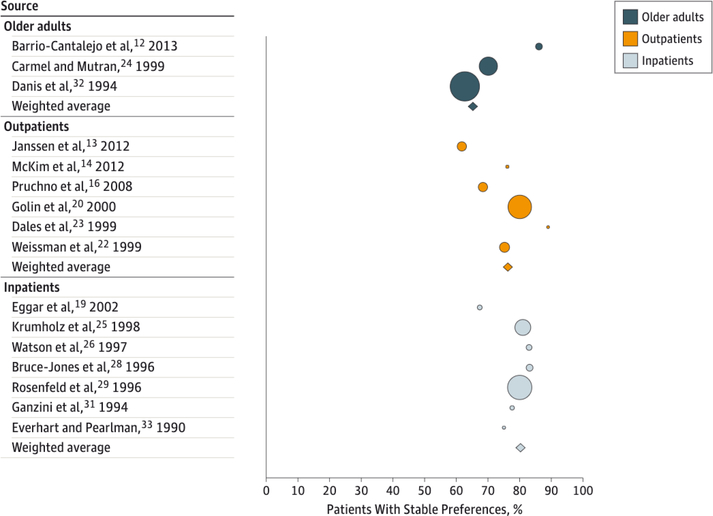

Table 1 and Table 2 summarizes the 24 studies that provided sufficient data to extract or calculate the percentage of individuals with stable preferences for specific treatments or the percentage of total stable preferences over time. Study level estimates of individuals’ preference stability from the 16 studies that reported the percentage of patients with stable preferences are depicted graphically to provide unadjusted portrayals of the effects of patients’ severity of illness (Figure 2). The percentages for each study are weighted by sample size to identify patterns across different types of studies. To avoid skewing the data, we omitted 1 outlying study (Kohut et a127), which reported 20.3% of 103 patients as having stable preferences. This estimate is markedly different from all other studies, perhaps owing to its use of a convenience sample of HIV positive patients attending outpatient clinics at a single hospital.

Table 1.

Studies Included in Quantitative Analysis

| Source, Year | Country | Patient Cohort? | Population Studied | Sample Sizea | Assessments, No. | Time Between Assessmentsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barrio-Cantalejo et al,12 2013 | Spain | No | Longitudinal cohort study of older adults | 85 | 2 | 18 mo |

| Janssen et al,13 2012 | Netherlands | Yes | Outpatients with COPD, CHF, or CRF | 206 | 4 | 4 mo |

| McKim et al,14 2012 | Canada | Yes | Outpatients with ALS | 26 | 2 | 1 mo |

| Sharman,15 2011 | Australia | No | Undergraduate psychology students | 57 | 2 | 1 mo |

| Pruchno et al,16 2008 | United States | Yes | D patients | 204 | 2 | 12 mo |

| Wittink et al,172008 | United States | No | Members of physician cohort study | 818 | 2 | 36 mo |

| Ditto et al,6 2006 | United States | Yes | Hospitalized older adults | 88 | 3 | 1 wk (following discharge) |

| McParland et al,18 2003 | United States | Yes | Nursing home residents | 55 (T2), 42 (T3) | 2–3 | 12 mo |

| Ditto et al,4 2003 and Houts et al,5 2002c | United States | No | Community-dwelling older adults | 361 (T2), 332 (T3) | 2–3 | 12 mo |

| Eggar et al,19 2002 | England | Yes | Inpatients with depression | 47 | 2 | 1 mo |

| Golin et al,20 2000 | United States | Yes | Outpatients with severe COPD, CHF, or cancer | 1288 | 2 | 2 mo |

| Gready et al,21 2000 | United States | No | Community-dwelling older adults | 51 | 21 | 24 mo |

| Weissman et al,22 1999 | United States | Yes | Outpatients with AIDS | 252 | 2 | 4 mo |

| Dales et al,23 1999 | Canada | Yes | Outpatients with severe COPD | 20 | 2 | 12 mo |

| Carmel and Mutran,24 1999 | Israel | No | Community-dwelling older adults | 802 (T2), 638 (T3) | 3 | 12 mo |

| Krumholz et al,25 1998 | United States | Yes | Inpatients with CHF exacerbation | 600 | 2 | 2 mo |

| Watson et al,26 1997 | New Zealand | Yes | Elderly inpatients without a terminal diagnosis | 70 | 2 | 2–3 wk (following discharge) |

| Kohut et al,27 1997 | Canada | Yes | Outpatients with HIV | 103 (T2), 62 (T3) | 2–3 | 6 mo |

| Bruce-Jones et al,28 1996 | England | Yes | Elderly inpatients admitted for emergency | 118 | 2 | Not specified (following discharge) |

| Rosenfeld et al,29 1996 | United States | Yes | Seriously ill inpatients | 1420 | 2 | 2 mo |

| Emanuel et al,30 1994 | United States | Yes | Outpatients with no terminal diagnosis; outpatients with HIV/AIDS, or cancer; members of the public | 296 | 3 | 6–12 mo |

| Ganzini et al,311994 | United States | Yes | Inpatients with depression | 43 | 2 | 3–4 wk (following discharge) |

| Danis et al,32 1994 | United States | No | Community-dwelling older adults | 2073 | 2 | 24 mo |

| Everhart et al,33 1990 | United States | Yes | Inpatients admitted to VA ICU | 20 | 2 | 1 mo |

Abbreviations: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRF, chronic renal failure; CX, chemotherapy; D, dialysis; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; T2 and T3, time points 2 and 3 (for studies with multiple repeat assessments of patients’ preferences); VAICU, Veterans Affairs intensive care unit.

Sample size refers to the number of individuals for whom preferences were assessed at 2 or more time points.

Time between assessments is approximated based on available data.

Identifies 2 articles that were considered as 1 study.

Table 2.

Preferences Queried and Rates of Preference Stability Across Studies

| Source, Year | Preference(s) Queried | Method of Data Collection | % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients With Stable Preferencesa | Total Preferences Stableb | Total Preferences |

||||

| CPR Stable | MV Stable | |||||

| Barrio-Cantalejo et al,12 2013 | AB, AN, CPR, CX, S | IPQ | 86.00 | 87.50 | 83.53 | NA |

| Janssen et al,13 2012 | CPR, MV | IPQ, TQ | 61.70 | 63.00 | 61.65 | 61.65 |

| McKim et al,14 2012 | MV | IPQ | 76.00 | 76.00 | NA | 76.00 |

| Sharman,15 2011 | AB, AN, CPR, S | IPQ | NR | 84.00 | DNGE | NA |

| Pruchno et al,16 2008 | D | TQ | 50.70–86.20 | 67.30 | NA | NA |

| Wittink et al,17 2008 | AB, AN, CPR, CX, D, MV, P | MQ | NR | 79.00 | 86.88 | 83.13 |

| Ditto et al,6 2006 | AN, CPR, S, other | IPQ | NR | 77.00 | 78.43 | NA |

| McParland et al,18 2003 | AN, CPR | IPQ | NR | 82.00 (T2), 73.81 (T3) | 79.59 (T2), 73.81(T3) | NA |

| Ditto et al,4 2003 and Houts et al,5 2002c | AN, CPR, S, other | IPQ | NR | 76.00 (T2), 67.00 (T3) | 78.43 | NA |

| Eggar et al,19 2002 | CPR | IPQ | 67.40 | 67.35 | 67.35 | NA |

| Golin et al,20 2000 | CPR | IPQ | 80.00 | NR | 68.00 | NA |

| Gready et al,212000 | AB, AN, CPR, S | IPQ, TQ | NR | 75.00 | 75.00 | NA |

| Weissman et al,22 1999 | CPR | IPQ | 75.21 | 75.21 | 72.60 | NA |

| Dales et al,23 1999 | MV | IPQ, TQ | 88.9 | 88.90 | NA | 88.90 |

| Carmel and Mutran,24 1999 | AN, CPR, MV | IPQ | 70.00 | NR | DNGE | DNGE |

| Krumholz et al,25 1998 | CPR | IPQ | 81.00 | 81.00 | 81.00 | NA |

| Watson et al,26 1997 | CPR | IPQ | 82.9 | 82.86 | 82.86 | NA |

| Kohut et al,27 1997 | AB, AN, CPR, MV | IPQ | 20.30 (T2), 19.40 (T3) | 73.00 | DNGE | DNGE |

| Bruce-Jones et al,28 1996 | CPR | IPQ | 83.10 | 83.10 | 83.10 | NA |

| Rosenfeld et al,29 1996 | CPR | IPQ | 80.00 | 80.00 | 80.00 | NA |

| Emanuel et al,30 1994 | AN, CPR, D, MV, P, S, other | IPQ, TQ, MQ | NR | 77.00 | DNGE | NA |

| Ganzini et al,311994 | AN, CPR, MV | IPQ | 67.00–88.00 | 79.17 | 76.40 | 80.56 |

| Danis et al,32 1994 | AN, CPR, MV, S, other | IPQ, TQ | 62.70 | DNGE | DNGE | DNGE |

| Everhart et al,33 1990 | CPR, D, MV, other | IPQ | 65.00–85.00 | 77.30 | 78.30 | 76.70 |

Abbreviations: AB, antibiotics; AN, artificial nutrition and/or hydration; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CX, chemotherapy; D, dialysis; DNGE, data not granular enough; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IPQ, in-person questionnaire; MQ, mailed questionnaire; MV, mechanical ventilation; NA, not available; NR, not reported; P, procedure; S, surgery; T2 and T3, time points 2 and 3 (for studies with multiple repeat assessments of patients’ preferences); TQ, telephone questionnaire.

The percentage of patients with stable preferences over time.

The percentage of all expressed preferences by all patients in the sample that were stable over time.

Identifies 2 articles that were considered as 1 study.

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients With Stable Preferences by Severity of Illness.

Studies were grouped into 3 categories based on the severity of illness of the source population: inpatients, outpatients, and older adults. Bubble size reflects the sample size of the study. Bubble color represents the source population. The diamonds represent a summary measure for each of the 3 groups. (The remaining 31 studies did not contain sufficient data to extract or calculate the percentage of individuals with stable preferences for specific treatment or the percentage of total stable preferences over time.)

The articles revealed considerable heterogeneity. The 2 study-level characteristics that seemed to be associated with patients’ level of EOL preference stability were severity of illness of the study sample and duration of follow-up time. As depicted in Figure 2, the percentage of patients with stable preferences seemed to be greater among inpatients than outpatients, and stability was greater in both patient samples than among community-dwelling older adults. Comparing these values using χ2 analysis revealed statistically significant differences between each group (P < .002). This pattern remained when examining preferences for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation separately (data not shown). Other study-level variables examined (year of publication, country of origin, and method of preference assessment) revealed no clear associations with preference stability.

We also assessed the relationship between preference stability and duration of follow-up, dividing the studies into 3 groups according to duration of follow-up (<6 months between assessments, 6–12 months, or >12 months). Although the numbers of studies in each group were small, studies with shorter follow-up times seemed to have more stable preferences than those with longer follow-up. However, because the 2 studies with long intervals between preference assessments (ie, >12 months) both sampled older outpatients without serious illnesses, 12 ,32 this pattern could not be distinguished from that suggested for patients’ severity of illness.

Clinical Factors and Preference Stability

Advance Directives

The presence of an AD was assessed as a potential predictor of stability in 6 studies.4,16,17,22,30,32 Five4,17,22,30,32 found that patients with an AD had greater stability of preferences than patients who did not. The sixth16 study found no relationship between AD completion and preference stability.

Initial Preferences

Three studies6,30,33 assessed how patients’ baseline preferences predicted later stability. All 3 found that individuals with a baseline preference to forego treatment had more stable preferences than individuals who initially preferred treatment.

Health Condition Queried

The severity of the health condition used in querying treatment preferences was assessed as a predictor of stability in 3 studies.4,16,21 All 3 found that in general, very mild health conditions (eg, mild stroke) and very severe conditions (eg, permanent coma) were associated with high preference stability, generally in the direction of accepting treatments in the former and rejecting them in the latter. Gready et a121 observed that when an individual’s preferences were congruent with the most common selection of the group, there was greater stability, suggesting that initial “outlier” preferences from those common to a population were those most likely to change.

Health Status: Objective and Subjective

Nine studies examined the association between an objective change in health status and stability of treatment preferences. Changes in health status were defined in several ways, including a decline in activities of daily living, decrease in physical functioning measures, and need for hospitalization. Four studies 16–18,33 found no relationship between 1 or more Of these measures and preference stability. Three studies found that being hospitalized22‘32 or reporting an increased number of disease diagnoses12 was associated with wanting more treatment. Two studies13,24 found that similar declines in health status were associated with wanting less treatment.

Four studies assessed baseline health status as a predictor for preference stability. Three found no association,6,16,27 while 1 study24 reported that individuals with a worse baseline health status had more stable preferences, consistent with the study-level pattern observed in Figure 2.

The patients’ subjective perceptions of their own health were assessed in 5 studies,6,12,27,31,32none of which found individual’s perceptions to be predictive of preference stability. Similarly, 3 studies6,12,27 examining pain found no association with preference stability.

Depression

Eight studies examined the relationship between depression and stability of preferences. Four found no association.6,18,27,33 Three studies found that an improvement in depression scores was associated with favoring more treatment19,31 or that a worsening was associated with favoring less treatment. 13 The final study32 noted the opposite, that a worsening depression score was associated with favoring more treatment.

Demographic Factors and Preference Stability

Seven studies examined age as a predictor of preference stability. Six studies12,16–18,31,32 found no relationship between age and preference stability, while 1 study4 found increased stability associated with increased age.

Sex was assessed as a potential predictor of preference stability in 6 studies. While 5 studies12,16,24,31,32 found no relationship, 1 study4 noted that men had more stable preferences than women.

The association between patients’ education and preference stability was assessed in 6 studies.4,16,22,24,30,32 All 6 found that patients with greater years of education were more likely to have stable treatment preferences.

Finally, race/ethnicity was assessed in 4 studies, with mixed results: 2 studies16,24 found no relationship, 1 study29 found white race to be associated with stability,32 and 1 study29 found African American race to be associated with stability.

Discussion

This systematic review suggests that most patients’ preferences for the types of EOL care they would like to receive are stable over time and after changes in health status. However, significant minorities of patients experience changes in these preferences. It is important to note that when such changes are observed, they are not in consistent directions. Indeed, striking findings of this systematic review include the variability found in both the proportions of patients whose preferences change across studies and in the directions of these changes when they occur (eg, toward or away from more aggressive care).

For example, most studies evaluating directions of preference changes showed that preferences typically evolve toward less aggressive care over time.8,17,24,32 However, other studies showed modal changes toward more aggressive care over time,7 or roughly even numbers of patients changing toward more and less aggressive care.22 Among studies examining the effects of health-state changes on preferences, declines in function have been associated with both decreased13,16and increased12,22,32 acceptance of aggressive treatments.

The variability in core findings among these studies could be attributable to differences in the patient populations or durations of follow-up. Variability may also stem from the methods used to assess preferences. Most studies were conducted by repeatedly asking the same questions of patients at different points in time. This approach could introduce changes in stated preferences (or possibly stability of preferences) that would not be observed if stated preferences or real decisions were monitored longitudinally in real-world settings. The 1 study14 in our review that evaluated trajectories of preferences under natural conditions found that the choices made by patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to receive ventilatory support following an educational program on mechanical ventilation accurately predicted the clinical choices made by 76% of patients.

The stability of preferences seemed to be greater among studies examining sicker populations (Figure 2), suggesting that for more seriously ill individuals, the questions may be more relevant, be contemplated more carefully, or may more closely respond to their current needs. However, this observation might also be attributable to the shorter duration between preference assessments among seriously ill cohorts. Indeed, a patient-level comparison within a large study30 published 20 years ago noted similar levels of stability among seriously ill outpatients and members of the general public. It therefore remains uncertain whether stability is particularly common to choices made by seriously ill patients. However, this review found no evidence that preference changes are particularly common among seriously ill patients, a finding that would have suggested real threats to the conceptual validity and clinical utility of advance directives. 34,35

Other observations provide complementary evidence in support of the conclusion that previously stated preferences for EOL care may be sufficiently stable to guide current care when patients’ preferences cannot be reassessed in the moment when decisions need to be made. First, 1 of the most consistent findings in this review was that patients who complete ADS have more stable preferences than those who do not. 17,22,32,36 This finding is consistent with prior work by Volandes et a137 showing that efforts to engage patients in actively thinking about these decisions can augment stability of preferences for treatment over time. Second, studies have found that initial preferences provide the most accurate among several potential predictors of subsequent preferences16 and it is important to note that these may be more accurate than surrogates’ predictions of patients’ later preferences. 5 Indeed, a systematic review of surrogates’ predictions of patients’ treatment preferences found that surrogates’ predictions were only 68% accurate.38 Finally, prospectively stated preferences for receiving certain treatments at the EOL have high degrees of convergent validity with patients’ own ratings of health states that treatments would produce.39

Nonetheless, the results of this review should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, despite the use of a systematic and fully reported search strategy, it is possible that studies reporting compatible data were not identified. The fact that some eligible articles were identified by hand search suggests that our search strategy was not fully sensitive. Second, we have not graded the quality of included studies. Given the nature of the research question, randomized trials are not germane, so most studies in this review would be categorized as low quality using modern evaluative systems.

Third, many studies used structured questionnaires to query EOL preferences and had a relatively short (12 months) median duration of follow-up time. Fourth, although the participation rates for the studies were reasonably high (median, 70.5%; IQR, 56.7%−84.7%), the sampling practices, when clearly reported, often included convenience samples. This may limit generalizability of the data. These attributes are important limitations both of the individual studies and, in turn, of our systematic review. Finally, the quantitative results are limited to those studies in which it was possible to extract sufficient data from manuscript text. This may have skewed the sample toward studies of specific treatment preferences rather than overall goals, and may have introduced bias if articles from which data were extractable contained different estimates of the stability than did others.

Conclusions

With these limitations in mind, this systematic review provides the most robust evidence to date suggesting that most patients for whom advance directives might be beneficial— namely, the seriously ill and those who actually complete directives—have preferences that are sufficiently stable such that they may be used to retain patient-centered decision making even when these patients lose capacity. However, this evidence base remains limited by the largely hypothetical settings in which preferences have been measured in studies to date, and by the possibility that bias could be introduced by the fact that in most studies, respondents were prompted to answer identical questions repeatedly over time, even when they did not volunteer changes in their preferences. Because these limitations would tend to overestimate the proportions of patients who change their preferences, future longitudinal research in more natural settings is needed to accurately assess the stability of EOL preferences over time and with changes in health states. Such work will further inform the conceptual basis for ADS and guide health care professionals regarding the optimal frequency for reassessing the preferences their patients state in ADS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation to Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania to fund Clinical Research Fellow Dr Auriemma, and by a grant from the Otto Haas Charitable Trust (Dr Halpern).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation. review. or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Contributor Information

Catherine L. Auriemma, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; Fostering Improvement in End-of-Life Decision Science (FIELDS) Program. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Christina A. Nguyen, Fostering Improvement in End-of-Life Decision Science (FIELDS) Program. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia Harvard College, Harvard University. Cambridge. Massachusetts; Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia.

Rachel Bronheim, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey.

Saida Kent, Fostering Improvement in End-of-Life Decision Science (FIELDS) Program. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Shrivatsa Nadiger, Department of Medicine, Presbyterian Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dustin Pardo, Department of Medicine. Einstein/Montefiore Medical Center, New York, New York.

Scott D. Halpern, Fostering Improvement in End-of-Life Decision Science (FIELDS) Program. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia; Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania, Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Pennsylvania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Silveira MJ, Kim SY. Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(13): 1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomes B Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care.2013.−12:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R. Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2) :377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ditto PH, Smucker WD, Danks JH, et al. Stability of older adults’ preferences for life-sustaining medical treatment. Health Psychol. 2003;22(6): 605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houts RM. Smucker WD, Jacobson JA. Ditto PH. Danks JH. Predicting elderly outpatients’ life-sustaining treatment preferences over time: the majority rules. Med Decis Making. 2002;22(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ditto PH, Jacobson JA, Smucker WD. Danks JH, Fagerlin A. Context changes choices: a prospective study of the effects of hospitalization on life-sustaining treatment preferences. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(4):313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried TR. O’Leary J, Van Ness P. Fraenkel L. Inconsistency over time in the preferences of older persons with advanced illness for life-sustaining treatrnent. J Am Geriatrsoc. 2007;55(7):1007–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fried TR. van Ness PH, Byers AL, Towle VR, O’Leary JR. Dubin JA. Changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among older persons with advanced illness. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(4): 495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried TR. Byers AL, Gallo WT. et al. Prospective study of health status preferences and changes in preferences over time in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):890–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pardon K, Deschepper R, Stichele RV, et al. ; EOLIC-Consortium. Preferences of patients with advanced lung cancer regarding the involvement of family and others in medical decision-making. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(10):1199–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pardon K Deschepper R. Vander Stichele R, et al. ; EOLIC-Consortium. Changing preferences for information and participation in the last phase of life: a longitudinal study among newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(10):2473–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrio-Cantalejo 1M, Simön-Lorda P. Molina-Ruiz A, et al. Stability over time in the preferences of older persons for life-sustaining treatment. J Bioeth Inq. 2013;10(1):103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janssen DJ. Spruit MA, Schols JM, et al. Predicting changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatment among patients with advanced chronic organ failure. Chest. 2012;141(5):1251–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKim DA, King J, Walker K, et al. Formal ventilation patient education for ALS predicts real-life choices. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2012;13(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharman SJ. Current negative mood encourages changes in end-of- life treatment decisions and is associated with false memories. Cogn Emot. 2011; 25(1):132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pruchno RA, Rovine MJ, Cartwright F, Wilson-Genderson M. Stability and change in patient preferences and spouse substituted judgments regarding dialysis continuation. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63(2):S81–S91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittink MN, Morales KH, Meoni LA, et al. Stability of preferences for end-of-life treatment after 3 years of follow-up: the Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2125–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McParland E, Likourezos A, Chichin E, Castor T. Paris BEBE. Stability of preferences regarding life-sustaining treatment: a two-year prospective study of nursing home residents. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggar R, Spencer A, Anderson D, Hiller L. Views of elderly patients on cardiopulmonary resuscitation before and after treatment for depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):170174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golin CE, Wenger NS, Liu H, et al. A prospective study of patient-physician communication about resuscitation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5)(suppl): S52–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gready RM. Ditto PH, Danks JH, Coppola KM, Lockhart LK. Smucker WD. Actual and perceived stability of preferences for life-sustaining treatment. J Clin Ethics. 2000;11(4):334–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weissman IS. Haas IS. Fowler FJ Jr, et al. The stability of preferences for life-sustaining care among persons with AIDS in the Boston Health study. Med Decis Making. 1999;19(1):16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dales RE, O’Connor A. Hebert P, Sullivan K, McKim D, Llewellyn-Thomas H. Intubation and mechanical ventilation for COPD: development of an instrument to elicit patient preferences. Chest. 1999;116(3):792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carmel S Mutran EJ. Stability of elderly persons’ expressed preferences regarding the use of life-sustaining treatments. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49 (3):303–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krumholz HM, Phillips RS, Hamel MB, et al. ; Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Resuscitation preferences among patients with severe congestive heart failure: results from the SUPPORT project. Circulation. 1998;98(7):648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watson DR, Wilkinson TJ, Sainsbury R, Kidd JE. The effect of hospital admission on the opinions and knowledge of elderly patients regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Age Ageing. 1997; 26(6):429–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohut N Sam M, ORourke K, MacFadden DK, Salit l, Singer PA. Stability of treatment palthough most preferences do not change, most people change some of their preferences. J Clin Ethics.1997;8(2):124–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce-Jones P, Roberts H, Bowker L, Cooney V. Resuscitating the elderly: what do the patients want? J Med Ethics. 1996;22(3):154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenfeld IKE, Wenger NS, Phillips RS. et al. ; SUPPORT Investigators. Factors associated with change in resuscitation preference of seriously ill patients. Arch Intern Med.1996;156(14):1558–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emanuel LL. Emanuel EJ, Stoeckle JD, Hummel I-R. Barry MJ. Advance directives: stability of patients’ treatment choices. Arch Intern Med. 1994; 154(2):209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ganzini L, Lee MA. Heintz RT. Bloom JD, Fenn DS. The effect of depression treatment on elderly patients’ preferences for life-sustaining medical therapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(11):1631–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danis M, Garrett J, Harris R, Patrick DL. Stability of choices about life-susta ining treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(7):567–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everhart MA, Pearlman RA. Stability of patient preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments. Chest. 1990;97(1):159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halpern SD. Shaping end-of-life care: behavioral economics and advance directives. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33(4):393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA. 2011;306(13):1447–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lockhart LK. Ditto PH, Danks JH, Coppola KM, Smucker WD. The stability of older adults’ judgments of fates better and worse than death. Death Stud. 2001;25(4):299–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow Ml. Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shalowitz DI. Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patrick-. Pearlman RA, Starks HE, Cain KC, Cole WG, Uhlmann RE Validation of preferences for life-sustaining treatment: implications for advance care planning. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(7):509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.