Abstract

Background

Quality of life (QOL) can be significantly impacted by symptoms of overactive bladder (OAB). Vibegron is a highly selective β3‐adrenergic receptor agonist that showed efficacy in treatment of symptoms of OAB in the randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active‐controlled phase 3 EMPOWUR trial. Here we report patient‐reported QOL outcomes from the EMPOWUR trial.

Methods

Patients were randomly assigned 5:5:4 to receive vibegron 75 mg, placebo or tolterodine 4 mg extended release, respectively, for 12 weeks. Patients completed the OAB questionnaire (OAB‐q) at baseline and at week 12 and the patient global impression (PGI) scales for severity, control, frequency and leakage at baseline and at weeks 4, 8 and 12. Change from baseline at week 12 and responder rates (OAB‐q: patients achieving a ≥10‐point improvement; PGI: patients reporting best possible response) were assessed. Vibegron was compared with placebo, and no comparisons were made between vibegron and tolterodine.

Results

Of the 1518 patients randomised, 1463 (placebo, n = 520; vibegron, n = 526; tolterodine, n = 417) had evaluable data for efficacy measures and were included in the analysis. Mean baseline OAB‐q and PGI scores were comparable among treatment groups. At week 12, patients receiving vibegron had greater improvements from baseline in OAB‐q subscores of coping, concern, sleep, health‐related QOL total and symptom bother (P < .01 each) compared with patients receiving placebo; a greater proportion of patients receiving vibegron vs placebo were responders in the OAB‐q coping (P < .05) and symptom bother scores (P < .0001). Compared with placebo, a greater proportion of patients who received vibegron achieved the best response on all PGI end‐points at week 12 (P < .05 each) and were classified as responders (P < .05 each).

Conclusions

In the 12‐week EMPOWUR trial, treatment with vibegron was associated with significantly greater and clinically meaningful improvement in OAB‐q and PGI scores compared with placebo, consistent with improvements in OAB symptoms.

Clinical trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier number NCT03492281.

What’s known

Bothersome symptoms of overactive bladder (OAB) negatively impact quality of life (QOL).

Vibegron is a β3‐adrenergic receptor agonist that has been shown to be safe and effective for the treatment of OAB in the phase 3 EMPOWUR trial.

What’s new

Treatment with vibegron was associated with improved QOL as assessed by the OAB questionnaire and patient global impression scale.

Consistent with symptomatic improvement, vibegron improves QOL in patients with OAB.

1. INTRODUCTION

An estimated 23% of US adults ≥40 years old experience bothersome symptoms of overactive bladder (OAB), 1 which can significantly affect quality of life (QOL). Symptoms such as urge urinary incontinence (UUI) are associated with substantial personal burden, including reduced health‐related QOL (HRQL). 2 , 3 Furthermore, patient perception of symptom severity can affect measures of QOL. As measured using the OAB questionnaire (OAB‐q), a gold‐standard measurement in the field, bothersome symptoms of OAB affect a patient's mental health. In the EpiLUTS survey that included 20 000 participants, respondents with OAB and bothersome symptoms reported not only worse HRQL but also increased anxiety and depression compared with respondents with no or minimal symptoms. 4 The psychological impact of OAB can extend beyond anxiety and depression; patients with OAB often report significantly more embarrassment and shame and a greater impact on social and sexual relationships compared with individuals without OAB. 5 As OAB affects both physical and psychological health, and in some cases may lack clinically objective markers, effectively capturing the patient's voice through the OAB‐q can allow physicians to optimise patient care. 6

Goals of treatment for OAB include maximising symptom control and QOL while minimising adverse events (AEs). 7 As such, a patient's willingness to continue taking their medication is imperative to maximise symptom benefit and subjective measures of QOL, which can further improve treatment adherence and persistence. However, a survey of patients taking OAB medications showed that nearly 50% of respondents who discontinued medication reported the medication not working as expected as the primary reason for discontinuation; further, 21% of respondents reported having side effects (ie, poor tolerability) as a reason for discontinuation. 8

Vibegron is a novel, highly selective oral β3‐adrenergic receptor agonist 9 that has a favourable drug‐drug interaction profile. 10 The efficacy of once‐daily vibegron for the treatment of OAB has been assessed in phase 2 and 3 trials. 9 , 11 , 12 EMPOWUR was an international, 12‐week placebo‐ and active‐controlled phase 3 trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of vibegron in patients with symptoms of OAB (N = 1518). 9 Patients treated with vibegron showed significant improvement vs placebo at week 12 in the coprimary end‐points of reduction in micturitions (P < .001) and UUI episodes (P < .0001), as well as in key secondary end‐points. 9 Onset of efficacy was rapid, with significant differences vs placebo observed by week 2, which were sustained throughout the trial. Because symptom severity has been shown to be correlated with patient‐reported QOL, 13 treatment resulting in symptomatic improvement would likely result in concomitant improvement in QOL measures in the EMPOWUR study. Here we present additional secondary and exploratory end‐points from EMPOWUR to assess the effect of 12 weeks of treatment with vibegron on patient‐reported QOL.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and patients

Detailed methods of the international, phase 3, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active‐controlled EMPOWUR trial has been previously published. 9 Briefly, adults with OAB were eligible for inclusion if they had wet or dry OAB for ≥3 months before the screening visit. Wet OAB was defined as an average of ≥8 micturitions and ≥1 UUI episodes per day. Dry OAB was defined as an average of ≥8 micturitions, <1 UUI episode and ≥3 urgency episodes per day. Up to 15% of patients enrolled could be men, and up to 25% could have dry OAB. Patients were randomly assigned 5:5:4 to receive vibegron 75 mg, placebo, or tolterodine 4 mg extended release, respectively, once daily for 12 weeks. The EMPOWUR trial was approved by an institutional review board, research ethics board or independent ethics committee before initiation, and all patients provided written informed consent before participating in any study procedures.

2.2. Assessments and end‐points

Patients completed the OAB‐q long form for a 1‐week recall period at baseline and at week 12. The OAB‐q is a patient‐reported, 33‐item, disease‐specific and validated instrument 6 , 14 that was selected to assess symptom bother and the overall impact of OAB on HRQL. The questionnaire contains an 8‐item symptom bother score (items scored from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity) and a 25‐item HRQL score (items scored from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating better QOL). 6 The HRQL score includes four subscales: coping, concern, sleep and social interaction. As an example, questions asked patients to consider the past week and quantify the frequency in which they: avoided activities (coping); were distressed (concern); were awakened (sleep); had family and social relationships affected (social interaction); or were bothered by the number of micturitions needed during the day (symptom bother) owing to OAB symptoms.

Patients also completed the patient global impression (PGI) of severity (PGI‐severity), PGI‐control, PGI‐frequency, PGI‐leakage and PGI‐change at baseline and at weeks 4, 8 and 12. The PGI‐severity and PGI‐change subscales have been previously validated. 15 The PGI is scored from 1 to 4 for severity; 1 to 5 for control, frequency and leakage; and 1 to 7 for change, with lower scores indicating better QOL. As an example, questions for each subscale asked patients to consider over the past week the severity of their symptoms (severity), control of their symptoms (control), frequency of symptoms (frequency), frequency of urine leakage (leakage) and severity of symptoms compared with the start of the study (change).

The key QOL secondary end‐point was change from baseline at week 12 in OAB‐q coping subscale score. Additional QOL secondary and exploratory end‐points were change from baseline at week 12 in OAB‐q HRQL total score, subscale scores and symptom bother score and change from baseline at week 12 in PGI scores.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Analysis of QOL end‐points compared vibegron with placebo. Tolterodine was included as an active control, but no statistical comparisons were made between vibegron and tolterodine. Analyses were performed using the full analysis set, which included all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study treatment and had ≥1 evaluable change from baseline micturition measurement. Least squares (LS) mean differences for changes from baseline parameters in each active arm vs placebo (and associated two‐sided 95% CIs) were estimated using a mixed model for repeated measures with restricted maximum likelihood estimation, with terms for treatment, visit, sex, region, OAB type, baseline score and visit‐by‐treatment interaction. To account for missing data, if <50% of the scale or subscale items were missing, the scale was retained as the mean score of the non‐missing items; if ≥50% of the scale items were missing, no scale score was calculated, and the subscale scores were considered missing. Change from baseline in OAB‐q coping score was a key secondary end‐point, which was included in a stepwise gatekeeping procedure to control the overall type 1 error rate at the α = 0.05 level (two‐sided). No adjustment was performed for multiplicity for the other analyses. In addition, a post hoc analysis was performed to calculate the percentage of patients considered responders for the OAB‐q scale and subscale scores at week 12 (ie, achieving a minimally important difference [MID] of ≥10‐point change from baseline). Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI of achieving the OAB‐q MID at week 12 were estimated using a logistic regression model that included terms for OAB type, sex and baseline score. Treatment differences between vibegron and placebo in PGI parameters were also analysed using parametric and non‐parametric methods. Similarly, LS mean differences in change from baseline (and associated 95% CIs) were estimated for each PGI parameter using a parametric mixed model for repeated measures with terms for treatment, visit, sex, region, OAB type, baseline score and visit‐by‐treatment interaction. The distributions of responses between vibegron and placebo for each PGI end‐point were evaluated post hoc using the non‐parametric Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel test for ordinal data adjusted for sex and OAB type. Additional post hoc analyses were performed to determine the percentage of patients achieving the best response on each PGI subscale at week 12 (best response for PGI severity was none, for PGI‐control was complete control, for PGI‐frequency and PGI‐leakage was never, and for PGI‐change was much better). For each end‐point, the adjusted OR and 95% CI of achieving the best possible response at week 12 were derived from a post hoc analysis using a logistic regression model that included terms for OAB type, sex and baseline response.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

Overall, 1518 patients were randomised (placebo, n = 540; vibegron, n = 547; tolterodine, n = 431). Of the randomised patients, 1463 had evaluable data for changes in micturitions and were included in the full analysis set. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics were well balanced across the three treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, mean (SD) age was 60.2 (13.3) years. By trial design, 85% of patients were women, and 77% had wet OAB. Mean baseline OAB‐q and PGI scores were also comparable among treatment groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient baseline demographics, clinical characteristics and QOL measures (full analysis set)

| Characteristic |

Placebo N = 520 |

Vibegron N = 526 |

Tolterodine N = 417 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, y | 59.9 (13.3) | 60.8 (13.3) | 59.8 (13.2) |

| Men, n (%) | 75 (14.4) | 77 (14.6) | 65 (15.6) |

| Wet OAB, n (%) | 405 (77.9) | 403 (76.6) | 319 (76.5) |

| Mean (SD) OAB‐q score, n | 518 | 524 | 416 |

| Total HRQL | 63.7 (23.5) | 62.7 (24.9) | 64.5 (22.9) |

| Coping | 58.7 (27.1) | 57.6 (28.1) | 59.8 (26.4) |

| Concern | 63.5 (25.9) | 61.9 (27.4) | 63.7 (26.0) |

| Sleep | 57.1 (26.4) | 58.0 (27.9) | 59.6 (25.2) |

| Social interaction a | 78.7 (25.0) | 76.8 (26.0) | 78.3 (24.7) |

| Symptom bother | 50.1 (20.6) | 49.7 (22.0) | 48.0 (20.6) |

| Mean (SD) PGI score, n | 519 | 525 | 417 |

| PGI‐severity | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.6) |

| PGI‐control | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.2 (0.9) | 3.2 (0.9) |

| PGI‐frequency | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.8) | 3.7 (0.9) |

| PGI‐leakage b | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.9) |

| PGI‐change | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.5 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: HRQL, health‐related QOL; OAB, overactive bladder; OAB‐q, OAB questionnaire; PGI, patient global impression; QOL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

Placebo, n = 517; tolterodine, n = 417.

Placebo, n = 405; vibegron, n = 402; tolterodine, n = 319.

3.2. OAB‐q measures

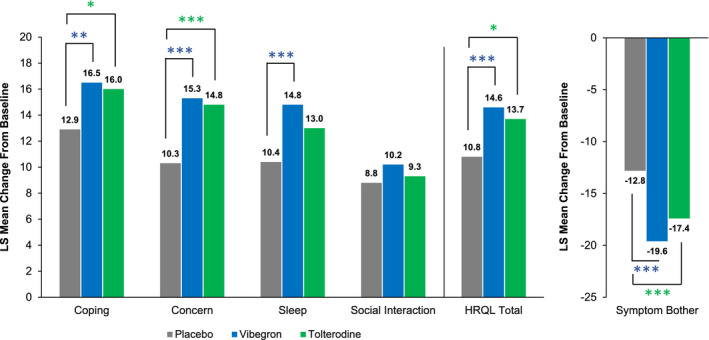

Patients receiving vibegron had significantly greater improvement from baseline to week 12 in OAB‐q coping subscale score compared with placebo (LS mean [SE] change: 16.5 [1.3] vs 12.9 [1.3], respectively; P < .01; Figure 1). Patients receiving vibegron also had greater improvement from baseline to week 12 in concern, sleep, HRQL total and symptom bother subscale scores (Figure 1). The between‐group difference at week 12 for vibegron vs placebo was significant for five of the six OAB‐q measures (coping, concern, sleep, HRQL total, symptom bother; Table 2). Although direct statistical comparisons were not performed, patients treated with vibegron had numerically greater improvement in OAB‐q scores from baseline to week 12 compared with tolterodine. At week 12, greater percentages of patients receiving vibegron compared with placebo were classified as responders for the OAB‐q coping (61.9% vs 54.4%, respectively), concern (55.7% vs 49.8%), sleep (53.9% vs 51.8%), social interaction (40.6% vs 35.2%), HRQL total (54.1% vs 48.6%) and symptom bother (70.1% vs 58.3%) scores. At week 12, patients treated with vibegron vs placebo were significantly more likely to be classified as responders in the coping score (OR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.09‐1.90]; P < .05) and symptom bother score (OR, 1.89 [95% CI, 1.43‐2.50]; P < .0001). The OR [95% CI] for vibegron vs placebo was more favourable than for tolterodine vs placebo at week 12 for sleep (1.20 [0.91‐1.59] vs 1.10 [0.82‐1.47], respectively), social interaction (1.32 [0.94‐1.85] vs 1.21 [0.84‐1.74]), HRQL total (1.32 [0.99‐1.75] vs 1.26 [0.93‐1.70]) and symptom bother (1.89 [1.43‐2.50] vs 1.64 [1.22‐2.20]).

FIGURE 1.

LS mean change from baseline at week 12 in OAB‐q scores. The n value for each treatment group varied for each OAB‐q subscale score. For coping, concern, sleep, social interaction and HRQL total, increases indicate improvement; for symptom bother, decreases indicate improvement. HRQL, health‐related quality of life; LS, least squares; OAB‐q, overactive bladder questionnaire. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001

TABLE 2.

LSMD in OAB‐q scores vs placebo at week 12 (full analysis set)

| OAB‐q score a | Vibegron | Tolterodine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSMD (95% CI) b | P value b | LSMD (95% CI) b | P value b | |

| HRQL total | 3.8 (1.7 to 5.8) | <.001 | 2.9 (0.6 to 5.1) | .0114 |

| Coping | 3.6 (1.2 to 6.0) | .0039 | 3.1 (0.5 to 5.7) | .0210 |

| Concern | 5.0 (2.7 to 7.3) | <.0001 | 4.5 (2.0 to 6.9) | <.001 |

| Sleep | 4.5 (2.0 to 7.0) | <.001 | 2.6 (0.0 to 5.3) | .0524 |

| Social interaction c | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.3) | .1081 | 0.6 (−1.4 to 2.5) | .5621 |

| Symptom bother | −6.9 (−9.2 to −4.6) | <.0001 | −4.6 (−7.1 to −2.2) | <.001 |

HRQL items were scored from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating better QOL; increases in scores indicate improvement. Symptom bother items were scored from 1 to 6, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity; decreases in scores indicate improvement.

If <50% of items were available, the subscore was regarded as missing; if ≥50% of items were available, the subscore included missing items imputed as the average of the remaining non‐missing items for the subscore.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HRQL, health‐related QOL; LSMD, least‐squares mean difference; OAB, overactive bladder; OAB‐q, OAB questionnaire; QOL, quality of life.

Vibegron, n = 512; tolterodine, n = 400; placebo, n = 504.

Vs placebo.

Tolterodine n = 401; placebo, n = 503.

3.3. PGI measures

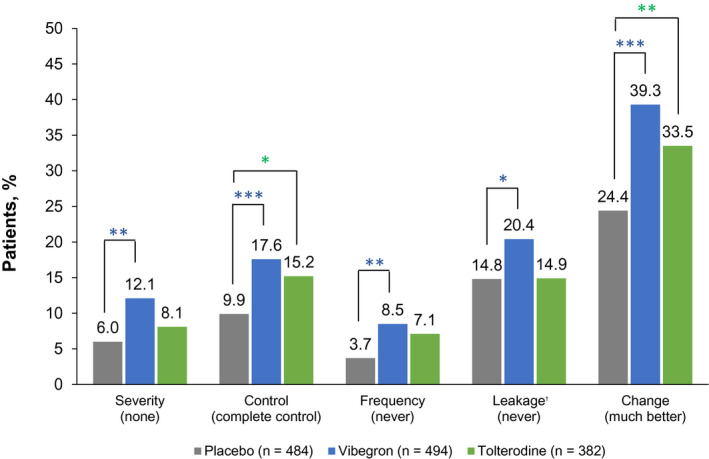

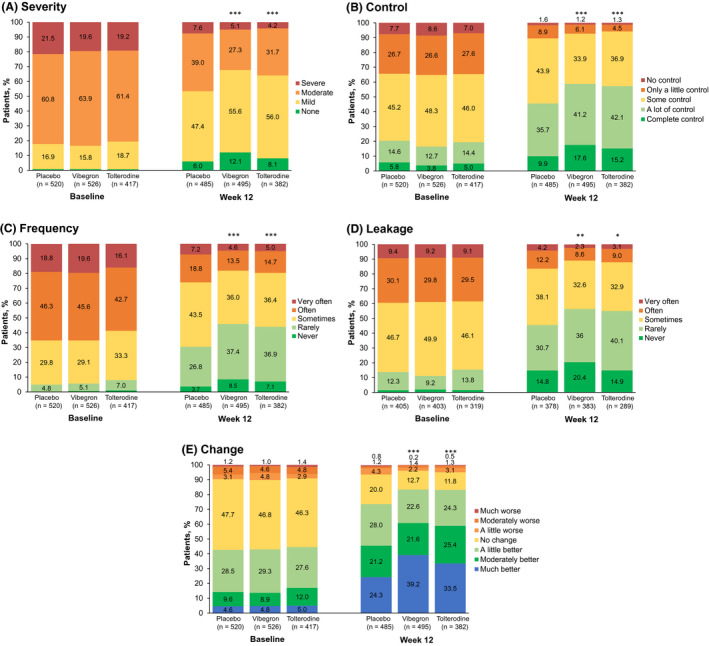

LS mean change from baseline at week 12 was significantly improved with vibegron for all PGI end‐points compared with placebo (Table 3). Patients treated with vibegron had numerically greater LS mean change from baseline at week 12 compared with tolterodine. A greater proportion of patients who received vibegron reported the most favourable responses on PGI end‐points at week 12 compared with placebo (Figure 2). At week 12, patients treated with vibegron vs placebo were significantly more likely to report best response for each PGI end‐point; ORs and 95% CIs for vibegron vs placebo were >1.0 for all PGI end‐points. The overall distribution of responses for each PGI measure shifted over time from less favourable to more favourable responses, with significantly greater changes from baseline seen with vibegron vs placebo (Figure 3). The OR [95% CI] for vibegron vs placebo was more favourable than for tolterodine vs placebo for all PGI measures at week 12: severity (2.2 [1.4‐3.5] vs 1.4 [0.8‐2.3], respectively), control (2.2 [1.5‐3.3] vs 1.7 [1.1‐2.6]), frequency (2.4 [1.4‐4.3] vs 1.7 [0.9‐3.3]), leakage (1.6 [1.1‐2.4] vs 1.0 [0.6‐1.5]) and change (2.2 [1.6‐2.9] vs 1.6 [1.1‐2.2]).

TABLE 3.

LSMD in PGI scores vs placebo at week 12 (full analysis set)

| PGI end‐point a | Vibegron | Tolterodine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSMD (95% CI) b | P value b | LSMD (95% CI) b | P value b | |

| PGI‐severity | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | <0.0001 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0) | .0055 |

| PGI‐control | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | <0.0001 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | <.001 |

| PGI‐frequency | −0.3 (−0.4 to −0.2) | <0.0001 | −0.2 (−0.3 to −0.1) | .0023 |

| PGI‐leakage c | −0.2 (−0.4 to −0.1) | <0.001 | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0) | .1768 |

| PGI‐change | −0.4 (−0.6 to −0.3) | <0.0001 | −0.3 (−0.5 to −0.1) | <.001 |

The PGI is scored from 1 to 4 for severity; 1 to 5 for control, frequency and leakage; and 1 to 7 for change. Lower scores indicate better QOL; decreases in score indicate improvement.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; LSMD, least‐squares mean difference; PGI, patient global impression; QOL, quality of life.

Vibegron, n = 494; tolterodine, n = 382; placebo, n = 484.

Vs placebo.

Vibegron, n = 382; tolterodine n = 289; placebo, n = 378.

FIGURE 2.

Post hoc analysis of percentage of patients reporting the best response for each PGI measure at week 12. For PGI‐severity, responses included none (best response), mild, moderate and severe. For PGI‐control, responses included complete control (best response), a lot of control, some control, only a little control and no control. For PGI‐frequency and PGI‐leakage, responses included never (best response), rarely, sometimes, often and very often. For PGI‐change, responses included much better (best response), moderately better, a little better, no change, a little worse, moderately worse and much worse. Percentages were calculated based on the number of patients included in the logistic regression model, where each patient had values at baseline and at week 12. PGI, patient global impression. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. †Placebo, n = 378; vibegron, n = 382; tolterodine, n = 289

FIGURE 3.

Post hoc analysis of percentage of patients selecting each response at baseline and week 12 for PGI (A) severity, (B) control, (C) frequency, (D) leakage and (E) change. Percentages were calculated based on the number of patients at each visit. PGI, patient global impression. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001 (for the distribution compared with placebo)

4. DISCUSSION

In this analysis of patient‐reported outcomes from the EMPOWUR trial, 12 weeks of treatment with once‐daily vibegron was associated with significant improvement in subjective QOL outcomes related to OAB, extending results of the coprimary and key secondary end‐points in which vibegron significantly improved OAB symptoms compared with placebo. 9 Consistent with significant and rapid improvements observed on all efficacy parameters, 9 patients receiving vibegron had significantly greater improvements vs placebo at week 12 for OAB‐q coping, concern, sleep and symptom bother subscale scores and HRQL total score. Patients receiving vibegron also had greater improvement in PGI scores vs placebo at week 12, and a significantly higher percentage of patients indicated the best possible response in individual PGI measures, suggesting that they were unaffected or minimally affected by symptoms of OAB. Patients receiving tolterodine also showed significant improvement vs placebo at week 12 for OAB‐q coping, concern and symptom bother subscale scores and HRQL total score and for PGI measures, consistent with the results of previous studies. 16 , 17 , 18

Scores for the OAB‐q social interaction subscale were relatively high at baseline across all treatment groups, indicating high patient‐perceived QOL with respect to social interaction. It is therefore not surprising that patients receiving vibegron or tolterodine did not show significant differences vs placebo after 12 weeks. These results are in agreement with previous analyses in which the social interaction subscale has shown the smallest effect size compared with the other OAB‐q subscales. 19 , 20

Although objective efficacy measures are able to show clear benefit for patient symptoms, it is important to show that symptomatic improvements also translate into improvements in patient‐reported QOL. As such, guidance from the International Continence Society recommends assessing QOL measures in addition to symptom measures. 21 Patient satisfaction with treatment, which can differ among patients owing to intrinsic characteristics or beliefs (ie, that of efficacy and tolerability), can also influence subjective QOL and is an important factor contributing to treatment adherence. 8 Vibegron has been shown to be safe and well tolerated, with a low incidence of AEs, 9 which may also improve treatment adherence and be associated with improved QOL. 22 The 12‐week EMPOWUR study was a relatively short duration to measure long‐term treatment adherence and persistence, but subjective measures of QOL may provide insight into a patient's likelihood of continuing treatment. A 10‐point change in OAB‐q subscales has been shown to represent a MID 20 and suggests that patients achieving this change in score perceive greater treatment benefit and potentially greater satisfaction. In this study, responder analysis at week 12 showed that a significantly higher percentage of patients receiving vibegron compared with placebo achieved a MID in OAB‐q coping and symptom bother subscale scores.

Despite the QOL end‐points being secondary objectives in the EMPOWUR trial, validated measures (ie, OAB‐q long form for 1‐week recall and PGI) were used, and the results were robust in the large patient population. While 12 weeks of treatment with vibegron are generally sufficient to demonstrate clinical efficacy, long‐term effects of vibegron on OAB outcomes and QOL measures may be more meaningful. Furthermore, EMPOWUR was not designed to assess differences between vibegron and the active control, tolterodine; however, patients receiving vibegron had numerically greater improvements in all OAB‐q scores and all PGI scores from baseline to week 12 compared with those receiving tolterodine.

5. CONCLUSION

In the 12‐week EMPOWUR trial, patients treated with vibegron experienced significantly greater and clinically meaningful improvements compared with placebo in patient‐reported QOL measures. Vibegron treatment improves symptomatic efficacy measures as well as QOL measures and should lead to improved treatment adherence and persistence. Vibegron may represent an important new therapy to address a high unmet medical need for patients with OAB.

DISCLOSURE

JF is an investigator for Urovant Sciences, an investigator and speaker for Astellas Pharma and Pfizer Inc, and a speaker for Tolmar Inc. SV is principal investigator for Clinical Research Consulting and adjunct professor at Sacred Heart University and University of Bridgeport. DS is an investigator and consultant for Urovant Sciences; a consultant, investigator and speaker for Astellas Pharma; and a consultant for New Uro BV. DS, RJ and PNM are employees of Urovant Sciences and may be shareholders.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Krystina Neuman, PhD, CMPP, of The Curry Rockefeller Group, LLC (Tarrytown, NY), and was funded by Urovant Sciences, Inc (Irvine, CA). This study was funded by Urovant Sciences.

Frankel J, Varano S, Staskin D, Shortino D, Jankowich R, Mudd PN Jr. Vibegron improves quality‐of‐life measures in patients with overactive bladder: Patient‐reported outcomes from the EMPOWUR study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13937. 10.1111/ijcp.13937

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Request for data from Urovant Sciences (email: medinfo@urovant.com) will be considered from qualified researchers on a case‐by‐case basis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, Thompson C, Kopp ZS, Milsom I. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology. 2011;77:1081‐1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Comorbidities and personal burden of urgency urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:1015‐1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, Ebel‐Bitoun C, Milsom I, Chapple C. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health‐related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2011;108:1459‐1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Milsom I, Kaplan SA, Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS. Effect of bothersome overactive bladder symptoms on health‐related quality of life, anxiety, depression, and treatment seeking in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. Urology. 2012;80:90‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kinsey D, Pretorius S, Glover L, Alexander T. The psychological impact of overactive bladder: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:69‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coyne K, Revicki D, Hunt T, et al. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder symptom and health‐related quality of life questionnaire: the OAB‐q. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:563‐574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gormley EA, Lightner DJ, Burgio KL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non‐neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. Am Urol Assoc. 2019;1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient‐reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int. 2010;105:1276‐1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Staskin D, Frankel J, Varano S, Shortino D, Jankowich R, Mudd PN Jr. International phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo and active controlled study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of vibegron in patients with symptoms of overactive bladder: EMPOWUR. J Urol. 2020;204:316‐323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rutman MP, King JR, Bennett N, Ankrom W, Mudd PN. Once‐daily vibegron, a novel oral β3 agonist, does not inhibit CYP2D6, a common pathway for drug metabolism in patients on OAB medications. J Urol. 2019;201:e231. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitcheson HD, Samanta S, Muldowney K, et al. Vibegron (RVT‐901/MK‐4618/KRP‐114V) administered once daily as monotherapy or concomitantly with tolterodine in patients with an overactive bladder: a multicenter, phase IIb, randomized, double‐blind, controlled trial. Eur Urol. 2019;75:274‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoshida M, Takeda M, Gotoh M, Nagai S, Kurose T. Vibegron, a novel potent and selective β3‐adrenoreceptor agonist, for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled phase 3 study. Eur Urol. 2018;73:783‐790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Homma Y, Gotoh M. Symptom severity and patient perceptions in overactive bladder: how are they related? BJU Int. 2009;104:968‐972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coyne KS, Gelhorn H, Thompson C, Kopp ZS, Guan Z. The psychometric validation of a 1‐week recall period for the OAB‐q. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1555‐1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tincello DG, Owen RK, Slack MC, Abrams KR. Validation of the Patient Global Impression scales for use in detrusor overactivity: secondary analysis of the RELAX study. BJOG. 2013;120:212‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelleher CJ, Kreder KJ, Pleil AM, Burgess SM, Reese PR. Long‐term health‐related quality of life of patients receiving extended‐release tolterodine for overactive bladder. Am J Manage Care. 2002;8:S616‐S630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelleher CJ, Reese PR, Pleil AM, Okano GJ. Health‐related quality of life of patients receiving extended‐release tolterodine for overactive bladder. Am J Manage Care. 2002;8:S608‐S615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roberts R, Bavendam T, Glasser DB, Carlsson M, Eyland N, Elinoff V. Tolterodine extended release improves patient‐reported outcomes in overactive bladder: Results from the IMPACT trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:752‐758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coyne KS, Matza LS, Thompson CL. The responsiveness of the Overactive Bladder Questionnaire (OAB‐q). Qual Life Res. 2005;14:849‐855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coyne KS, Matza LS, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, Khullar V. Determining the importance of change in the overactive bladder questionnaire. J Urol. 2006;176:627‐632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mattiasson A, Djurhuus JC, Fonda D, Lose G, Nordling J, Stöhrer M. Standardization of outcome studies in patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction: a report on general principles from the Standardisation Committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:249‐253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim A, Lee KS, Jung R, et al. Health related quality of life in patients with side‐effects after antimuscarinic treatment for overactive bladder. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2017;9:171‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Request for data from Urovant Sciences (email: medinfo@urovant.com) will be considered from qualified researchers on a case‐by‐case basis.