Abstract

Objective

To better understand if employer-based financial coverage of non-medical oocyte cryopreservation impacts the way women make decisions about their reproduction, including the decision to pursue oocyte cryopreservation and the time frame in which they plan to begin family building.

Design

Prospective survey study.

Setting

Academic medical center.

Patient(s)

Female graduate students at five different institutions in the Boston area.

Intervention(s)

A 27-question electronic survey.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Likelihood of pursuing oocyte cryopreservation and time frame in which intend to build family, based on presence or absence of employer-based financial coverage.

Result(s)

The survey was completed by 171 female graduate students: 63% cited professional goals as their primary reason for delaying childbearing, and 54% indicated that oocyte cryopreservation would allow them to focus more on their career for the next several years. For 59% their main concern about egg freezing was the cost; 81% indicated that they would be more likely to consider egg banking if it were covered by their insurance or paid for by their employer. The majority of participants would not change when they would start building their family based on the presence or absence of employer financial coverage for egg freezing.

Conclusion(s)

The primary concern of female graduate students about egg freezing is the cost. More women would consider elective egg freezing if financial coverage was provided by their employer, but the vast majority would ultimately not change their plans for and timing of family building based on this coverage.

Key Words: Egg freezing, fertility preservation, financial coverage, oocyte cryopreservation

Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and other readers at https://www.fertstertdialog.com/posts/xfre-d-20-00135

As the reproductive potential of women decreases with increasing maternal age (1), oocyte cryopreservation (OC) or “egg freezing” allows for its preservation. One application of OC is non-medical (or “elective”), allowing women to defer childbearing and have biologic children later in life while minimizing the impact of age on aneuploidy and spontaneous abortion. The technology for OC has improved dramatically over the past decade, such that the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) no longer considers OC an “experimental” procedure (2). In fact, ASRM considers it ethically permissible for women to use OC to protect against future infertility due to reproductive aging (3). Use of OC for elective fertility preservation is increasing (4), with the preliminary data showing 8,825 OC cycles in 2016, a greater than 25% increase from 1 year prior (5), although notably a portion of these were likely done before gonadotoxic therapy, not solely for elective OC.

Little is known about women’s decision-making about delaying childbearing through OC. In a study of 189 women who had undergone a cycle of elective OC to defer reproduction, 88% cited lack of a partner as a reason, while 19% cited workplace inflexibility (6). Conversely, in a study of medical students and house staff on delaying childbearing, 86% cited education or career as the reason, with relationship status being the second most common indication (7). Furthermore, it remains unclear whether women undergoing elective OC ultimately delay childbearing compared with women who do not. A retrospective study of 86 women who completed an OC cycle compared with 54 women who presented for consultation but ultimately did not cryopreserve oocytes showed no difference in terms of experiencing steady relationships or attempting conception when interviewed 1 to 3 years later (8).

To date, pursuing elective OC has primarily been an out-of-pocket expense (9), and women interested in elective OC cite finances as the most common factor influencing their decision (7, 10). Recently, several large public companies—including Apple, Facebook, Citigroup, JP Morgan Chase, and Intel—have announced coverage of some or all of the costs of elective OC for female employees (11, 12, 13). There has been much speculation as to how this “benefit” will impact women and their choices in pursuing childbearing, including the possibility that this coverage will cause women to feel pressured to delay childbearing for the sake of their career (11, 13, 14). There are few published data to confirm or refute the speculation. The sole study to specifically look at this question surveyed 99 female medical students; despite 76% of the respondents indicating they felt pressure to delay childbearing for professional reasons, 71% did not consider employer coverage of elective OC to be coercive, and 77% indicated that they would not delay childbearing simply due to having employer coverage for OC (15).

How the opportunity to pursue elective OC, especially with the financial burden removed by employer coverage, will impact women’s reproductive decision-making and reproductive autonomy is of critical importance to women’s health and women’s rights within society. Although some argue that female fertility preservation is a step toward reproductive justice and gender equality, others argue that this technology is simply the “medicalization” of societal problems that make it difficult for women to have children at a younger age and that OC undermines efforts to fix the societal cause of delayed childbearing (16). Understanding how women think about their current and future family building and how they make the decision to pursue or not pursue OC can help medical professionals to appropriately counsel women considering this treatment. The aims of our study were to better understand whether employer-based financial coverage of non-medical oocyte cryopreservation impacts the way women make decisions about their reproduction, including the decision to pursue OC and the time frame on which they plan to begin family building.

Materials and methods

Procedure

A secure, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA)–compliant survey was created using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), and the study was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Eight of the largest graduate schools in the Boston area (Bentley University, Boston College, Boston University, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Northeastern University, Suffolk University, and Tufts University) were contacted via their deans of the arts and sciences, law, master of business administration (M.B.A.), dental, and medical schools.

Permission was requested to distribute the survey via e-mail to the deans’ female students. Five deans representing different graduate degrees (arts and sciences masters and doctorate, M.B.A., law, and dental) at five different universities granted permission. The participating deans e-mailed the survey through the graduate program’s electronic mailing list. The participants consented via the first survey question. No identifying information was collected, and no remuneration was given.

The Survey

The 27-item survey (available as supplemental material) collected information on demographics, plans for future fertility, and the impact of employer coverage for OC on the decision to pursue OC and the timing of family building.

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14 (StataCorp LLC). Demographic data were reported as percentages of the total study population. Chi-square analyses (with Bonferroni P value corrections for multiple comparisons) and univariate logistic regression were used to determine any associations between demographic factors and consideration of OC and childbearing plans. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

One hundred and seventy-one female graduate students completed the survey. Detailed demographic data are summarized in Table 1. Most (81%) of the participants were between the ages of 21 and 30, 82% identified their race as White, and 91% identified as non-Hispanic. Half (50%) of participants identified as single, 25% identified as partnered, and 22% as married. Almost all participants (94%) had no children at the time of the survey administration. Most participants (83%) reported their total annual household income as $99,999 or less, with 39% of participants reporting an annual total household income of $20,000 to $49,999. For educational background, 50% of participants were pursuing a doctorate, 26% a master’s degree, 12% a dental degree, 6% a law degree, and 6% an M.B.A. No participants were pursuing a medical degree. Forty-nine percent of participants worked or were attending school 40 to 59 hours per week.

Table 1.

Basic demographics of respondents about egg freezing employer coverage (n = 171).

| Demographic | Value, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 21–25 | 63 (37) |

| 26–30 | 75 (44) |

| 31–35 | 25 (15) |

| 36–40 | 7 (4) |

| 41–45 | 1 (<1) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 19 (11) |

| Black or African American | 2 (1) |

| White | 140 (82) |

| More than 1 race | 8 (5) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 9 (5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 155 (91) |

| Missing | 7 (4) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 38 (22) |

| Single | 86 (50) |

| Separated | 2 (1) |

| Partnered | 43 (25) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| No. of current children | |

| 0 | 160 (94) |

| 1 | 5 (3) |

| 2 | 3 (2) |

| 3 | 1 (<1) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| Total annual household income | |

| <$20,000 | 41 (24) |

| $20,000–49,999 | 67 (39) |

| $50,000–99,999 | 35 (20) |

| $100,000–249,999 | 15 (9) |

| $250,000–499,999 | 2 (1) |

| $>500,000 | 1 (<1) |

| Missing | 10 (6) |

| Graduate degree pursuing | |

| Masters | 45 (26) |

| Ph.D. | 86 (50) |

| M.B.A. | 10 (6) |

| Dental | 20 (12) |

| Law | 10 (6) |

| Hours worked | |

| 0–19 | 14 (8) |

| 20–39 | 49 (29) |

| 40–59 | 83 (49) |

| 60–79 | 21 (12) |

| 80–99 | 1 (<1) |

| Missing | 3 (2) |

Family-Building Plans

When asked to describe their future plans around family building, 59% of the participants indicated they definitely planned to have children in the future (but not immediately), 32% were currently undecided about having children in the future, 5% either had or were currently trying to have children and may want more in the future, 2% already had children and did not want more in the future, and 2% indicated they do not have and do not plan to have children (Table 2). Those who were planning to become pregnant in the future but were not currently trying to conceive at the time were then asked their primary reason for deferring childbearing. The majority (63%) cited professional goals as their primary reason, 18% indicated it was due to lack of a partner, and 7% cited financial concerns. When asked if they worry about their future fertility, 50% of participants indicated that it was a concern, while another 19% stated they were not sure.

Table 2.

Family-building plans and egg freezing awareness.

| Survey question | Value, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Please describe your future plans around family building: | |

| I am definitely planning on having children in the future, but this is not part of my immediate planning. | 100 (59) |

| I am currently undecided about having children in the future, but would like to keep the option available. | 54 (32) |

| I am currently trying to have children or already have a child(ren), and may want to have children in the future as well. | 8 (5) |

| I already have children and do not plan on having more. | 4 (2) |

| I do not have children and do not plan to have children. | 4 (2) |

| If you plan to have children in the future but are not actively trying to become pregnant now, what is your primary reason for deferring pregnancy at this time? | |

| Financial | 11 (7) |

| Don’t have a partner | 27 (18) |

| Partner isn’t ready | 3 (2) |

| Professional goals | 95 (63) |

| Other | 15 (10) |

| Do you worry about your future fertility? | |

| Yes | 85 (50) |

| No | 51 (30) |

| Not sure | 33 (19) |

| Other | 1 (<1) |

| Have you heard of egg freezing fertility preservation (also known as “egg banking”)? | |

| Yes | 164 (97) |

| No | 5 (3) |

| How did you first hear about egg freezing? | |

| Friend | 27 (15) |

| Family member | 3 (2) |

| Medical provider (OB/GYN) | 3 (2) |

| Medical provider (medical doctor) | 1 (<1) |

| Advertisement | 8 (5) |

| Media coverage | 115 (68) |

| My educational institution | 9 (5) |

| Other | 3 (2) |

| What concerns do you have about freezing eggs? | |

| Cost | 98 (59) |

| Success rates | 23 (14) |

| Social stigma | 10 (6) |

| Other | 34 (21) |

| Are you currently pursuing egg freezing? | |

| Yes | 7 (4) |

| No | 127 (74) |

| Unsure | 37 (22) |

| Does your employer/educational institution offer financial coverage for egg freezing? | |

| Yes | 1 (<1) |

| No | 53 (31) |

| Unsure | 116 (68) |

| Other | 1 (<1) |

Egg-Freezing Awareness

Almost all (97%) of the female graduate students who participated in this study had heard of egg freezing (Table 2). The majority (68%) first heard about it through the media, while 15% heard about this technology through a friend. Less than 3% of participants first heard about egg freezing from a medical professional. For 59% of study participants, their main concern about egg freezing was the cost. Another 14% indicated that they were concerned about the success rates, and only 6% expressed concern about the social stigma associated with egg freezing. Notably, 4% of participants indicated that they were currently pursuing egg freezing.

Thought Process Regarding Career and Egg Freezing

About half the participants felt that they would be able to focus more on their career for the next several years if they were able to preserve their fertility by banking eggs (Table 3). Some indicated that were it not for their career goals, they would be ready to begin building a family now. The majority of participants felt that they had to choose between advancing their career and starting a family, and that they would be more likely to consider egg banking if it were covered by their insurance or paid for by their employer.

Table 3.

Opinions on employer coverage of egg freezing.

| Opinions on elective oocyte cryopreservation and employer financial coverage | Yes | No | Not sure |

|---|---|---|---|

| If you DID NOT have financial coverage for egg freezing offered by your institution/employer, would you consider egg freezing? | 10 | 39 | 51 |

| If you DID have financial coverage for egg freezing offered by your institution/employer, would you consider egg freezing? | 48 | 19 | 32 |

| If it weren’t for my career, I would be ready to begin building my family now. | 32 | 68 | — |

| I feel that right now I need to choose between advancing my career and starting a family. Doing both at the same time is not realistic. | 65 | 35 | — |

| I would be able to focus more upon my career for the next several years if I was able to preserve my fertility by banking eggs. | 54 | 46 | — |

| I would be more likely to consider egg banking if it were covered by my insurance or paid for by my employer. | 81 | 19 | — |

Employer Coverage of Egg Freezing

Only one participant indicated that her employer or education institution currently offers financial coverage for egg freezing. Most participants were unsure whether their employer or educational institution offered financial coverage (Table 2). The participants were asked whether they would consider egg freezing if their institution or employer offered financial coverage for the procedure (Table 3). Without financial coverage, only 10% of participants said they would consider egg freezing; if they did have financial coverage, 48% of participants would consider egg freezing, and another 32% remained unsure.

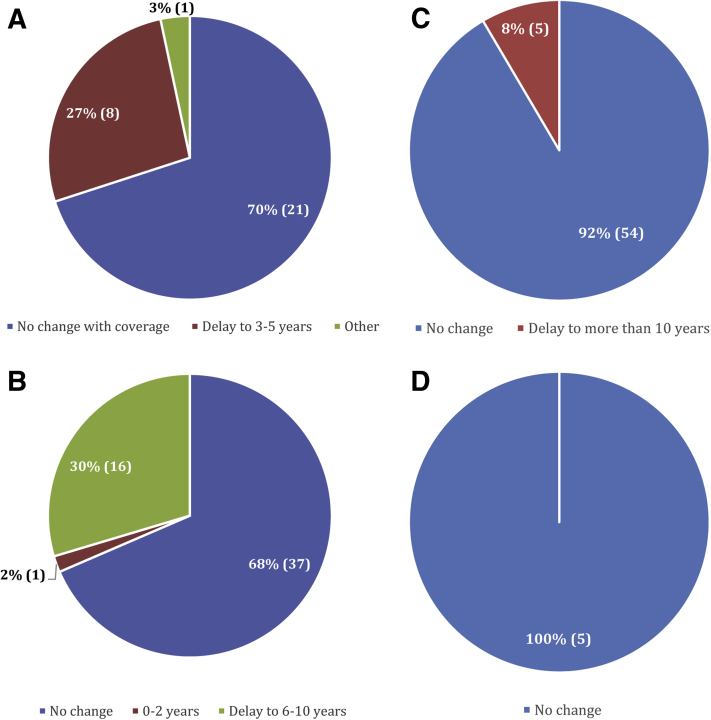

Figure 1 depicts how participants think about their plans for future family building and how those would change based on whether an employer covers egg freezing. The participants were also asked what time frame they would consider for their plan to have children if they did not have financial coverage for egg freezing offered by their institution or employer. Without coverage, 18% indicated they would plan to have children in 0 to 2 years, 32% said 3 to 5 years, 35% said 6 to 10 years, and 3% indicated they would plan to wait more than 10 years before having children.

Figure 1.

How does family planning change with employer-offered coverage? (A) Women who plan to start a family in 0–2 years in the absence of employer-covered egg freezing (n = 30). (B) Women who plan to start a family in 3–5 years in the absence of employer-covered egg freezing (n = 54). (C) Women who plan to start a family in 6–10 years in the absence of employer-covered egg freezing (n = 59). (D) Women who plan to start a family in more than 10 years in the absence of employer-covered egg freezing (n = 5).

The participants then were asked about the time frame in which they would plan to have children if they did have financial coverage for egg freezing offered by their institution or employer. Figure 1 shows how these answers changed based on lack of coverage or presence of coverage. Figure 1A shows that among the 30 women who indicated they would start a family in 0 to 2 years in the absence of employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation, 70% would not change their plans based on the presence of coverage, and 27% would delay childbearing and wait 3 to 5 years to start a family. In Figure 1B, of the 54 participants who indicated they would wait 3 to 5 years to start family in the absence of coverage, 68% would not change their plans should coverage be available, and 30% indicated they would delay childbearing and wait 6 to 10 years to start their family. Of those who planned to wait 6 to 10 years to start building their family (Fig. 1C), 92% would not change their plans based on the presence of employer coverage, while 8% would delay further. Of those who, in the absence of coverage, planned to wait more than 10 years before starting a family (Fig. 1D), 100% indicated that having employer coverage for oocyte cryopreservation would not change their childbearing plans.

Correlation of Demographics with Egg-Freezing Decision-Making

Asian graduate students were more likely to consider egg freezing compared with White graduate students (P<.002) or students of more than one race (P<.023). Dental students were more likely to consider egg freezing compared with the master’s students (P<.013). Those who worked 40 to 59 hours per week were more likely to consider egg freezing than those who worked <20 hours per week (P<.046). No other demographic factors correlated with the likelihood of considering egg freezing. Dental and law students were more likely to change their childbearing plans based on the presence of employer coverage compared with the master’s students (P<.013 and P<.022, respectively). No other demographic factor correlated with participants’ likelihood of changing their childbearing plans based on the absence or presence of employer coverage of egg freezing.

Discussion

In this study, the survey results indicated that female graduate student’s primary concern about egg freezing is the cost, and that more women would consider elective egg freezing if financial coverage was provided by their employer. However, the vast majority would ultimately not change their plans for and timing of family building based on this coverage. This finding is consistent with that of Ikhena-Abel et al. (15), the only other published survey analyzing the impact of employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation, who found that 73% of medical students would consider oocyte cryopreservation if coverage was offered by their employer, but 77% would not delay childbearing due to employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation. Furthermore, when asked specifically if they considered employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation coercive, 71% of medical students indicated they did not (15). Given media speculation that employer coverage of elective oocyte cryopreservation would impact women’s reproductive decision-making and potentially coerce women to delay childbearing for the sake of their careers (11, 13, 14), it is reassuring that professional women appear to maintain their reproductive autonomy irrespective of this new financial offering.

The study population, comprising women in a variety of graduate programs, was selected based on the knowledge that higher education levels are associated with later ages of childbearing (17), and women who pursue elective oocyte cryopreservation are more commonly college educated and professionally employed (18). Therefore, this population would be among those most likely to be faced with the decision to pursue elective oocyte cryopreservation, either with or without employer financial coverage.

Our study included graduate students across many specialties, although it did not include medical students; the deans of the area’s medical schools were contacted but did not accept our request for distribution of our survey. Therefore, our study provides an interesting point of comparison to the work of Ikhena-Abel et al. (15), which explored the views of 99 female medical students. In both studies, women would not change their childbearing plans based on employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation. This consistent finding across both studies is important because it dispels the potentially paternalistic argument that employer coverage is coercive, regardless of women’s professional fields or underlying medical knowledge.

Despite indicating that employer coverage of egg freezing would generally not change their plans regarding when to have children, 63% of graduate students cited professional goals as their reason for deferring childbearing, and 65% stated they needed to choose between advancing their careers and starting a family, a sentiment also seen among medical students and residents, where 76% to 86% reported delaying childbearing for professional reasons (7, 15). Our finding that professional goals are the primary reason for deferring childbearing differs from a study of women who actually underwent elective oocyte cryopreservation, which found lack of a partner to be the main reason women chose to pursue the technology (6).

This difference is likely reflective of the respective patient populations studied, with graduate students in professional programs who have already embarked on a strenuous educational path prioritizing their careers irrespective of partner status, as compared with a more general population of women. If not having a partner is the primary reason for delaying childbearing, then it could be inferred that employer coverage of elective oocyte cryopreservation should have no impact, as it does not affect partner status. Conversely, in a population in which educational and professional goals are the factor driving the decision to delay childbearing, it seems very feasible that the option to cryopreserve oocytes at limited financial cost to the individual could drive decisions about family building. Thus, our findings that women are not substantially altering their childbearing plans based on the presence or absence of employer coverage for elective egg freezing is particularly notable because the population of professional women surveyed likely reflects the population most at risk for being influenced by this offering.

It is notable that 68% of respondents in this study learned of egg freezing through the media, while fewer than 3% learned about the technology from a medical professional. This finding is consistent with, but even lower than, previous reports (6). A study of U.S. obstetrics and gynecology residents (OB/GYNs) found that the majority (83%) believe that OB/GYNs should initiate discussions about age-related fertility decline with their patients, but only 40% believed that OB/GYNs should initiate discussion about elective oocyte cryopreservation, and 20% believed it should be part of the annual well-woman examination (19). Meanwhile, 61% of women surveyed think physicians should provide women of childbearing age with information on oocyte cryopreservation at their annual visit (10). This lack of patient education by medical providers is a disconcerting finding given the evidence of misinformation regarding age-related fertility decline, ovarian reserve, and the effectiveness of fertility treatments among young highly educated women (19, 20, 21).

It is critically important that women be accurately informed and appropriately counseled about the process and time requirements of egg freezing, as well as the fact that oocyte cryopreservation does not guarantee a live birth in the future. One of the largest studies to date calculated an approximately 6% live-birth rate per frozen oocyte, with decreasing live-birth rates per oocyte cryopreserved as the woman’s age at cryopreservation increases (22). So as to not impart false hope, it is imperative that women pursue this technology with accurate expectations. While more specific counseling about oocyte cryopreservation may be left to a reproductive endocrinologist, women who have false expectations about the effectiveness of the procedure, particularly at later ages, may be delaying even pursuing a visit with a reproductive endocrinologist, which sets them up for disappointment when they do attempt to pursue oocyte cryopreservation or childbearing. Because OB/GYNs have at least annual interactions with these young women, their relationship presents an important opportunity for education on elective oocyte cryopreservation.

The strengths of this study include the timeliness of the topic and the input from women in several different disciplines of study. Notably, there has been very little study of attitudes toward fertility preservation and the related cost constraints even as reproductive technologies have increased the options for a growing number of women. Our conclusions are limited by our sample size, though it is larger than in other published similar studies (15). It was not possible to ascertain exactly how many women received or opened our survey e-mail; those who opted to complete the survey may have been overrepresentative of women with an interest in oocyte cryopreservation, resulting in a selection bias. The study population also included only graduate students and thus was more educated than the general population. Furthermore, the study sample had a higher percentage of White women than the general population, so the results may not be generalizable to the larger U.S. population. It is also possible that professional goals and advancement and partner status may be confounding variables. Finally, the possibility exists that decision-making on a theoretical scenario such as those posed in this survey may not be the same as what women would do if an opportunity were to actually present itself.

A greater understanding of this topic has far-reaching public health and economic implications. Future research is needed to explore attitudes and decision-making regarding employer coverage of oocyte cryopreservation in the general population, and it should specifically explore the use of oocyte cryopreservation among women at companies that do offer coverage, as compared with the general population. It is possible that those with graduate degrees have more confidence in their position in the workplace and thus feel less pressure to delay childbearing based on employer coverage than those without advanced degrees. Alternatively, it is also feasible that those with graduate degrees are pursuing more time-intensive careers and are even more likely than the general population to feel compelled to cryopreserve oocytes and delay childbearing.

Conclusion

Our study shows that the majority of graduate student women would consider elective egg freezing if financial coverage were offered by their employer, but would not change their family building plans based on this coverage. Nonetheless, it remains imperative that women are educated about age-related fertility decline, and realistic success rates of oocyte cryopreservation. Given that elective egg freezing is not a guarantee of a future live birth, and that this study demonstrates a clear pattern of women wanting to delay childbearing for professional reasons, improved employer-based and social policies to counteract postponement (17, 23) in conjunction with egg freezing may be a better solution to this conundrum.

Footnotes

E.R.C. has nothing to disclose. J.M.T. has nothing to disclose. K.E.J. has nothing to disclose. M.P.F. has nothing to disclose. T.L.T. has nothing to disclose.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Committee on Gynecologic Pratice of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Practice Committee of American Society for Reprodutive Medicine Age-related fertility decline: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(Suppl):S154–S155. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Practice Committee of American Society for Reprodutive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Planned oocyte cryopreservation for women seeking to preserve future reproductive potential: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2018;110:1022–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman K.N., Labella P.A., Grifo J.A., McCulloh D., Noyes N. The evolution of oocyte cryopreservation (OC): longitudinal trends at a single center. Abstract P-77. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(Suppl):e164. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology National summary report. https://www.sartcorsonline.com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx?reportingYear=2016 Available at:

- 6.Hodes-Wertz B., Druckenmiller S., Smith M., Noyes N. What do reproductive-age women who undergo oocyte cryopreservation think about the process as a means to preserve fertility? Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anspach Will E., Maslow B.S., Kaye L., Nulsen J. Increasing awareness of age-related fertility and elective fertility preservation among medical students and house staff: a pre- and post-intervention analysis. Fertil Steril. 2017;107:1200–1205.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoop D., Maes E., Polyzos N.P., Verheyen G., Tournaye H., Nekkebroeck J. Does oocyte banking for anticipated gamete exhaustion influence future relational and reproductive choices? A follow-up of bankers and non-bankers. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:338–344. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mertes H., Pennings G. Elective oocyte cryopreservation: who should pay? Hum Reprod. 2012;27:9–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniluk J.C., Koert E. Childless women’s beliefs and knowledge about oocyte freezing for social and medical reasons. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2313–2320. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett J. Company-paid egg freezing will be the great equalizer. Time, Oct. 15, 2014. http://time.com/3509930/company-paid-egg-freezing-will-be-the-great-equalizer/ Available at:

- 12.Friedman D. NBC News; Oct. 14, 2014. Perk up: Facebook and Apple now pay for women to freeze eggs.http://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/perk-facebook-apple-now-pay-women-freeze-eggs-n225011 Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoll M., Mertes H., Gupta J. Corporate giants provide fertility benefits: have they got it wrong? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;195:A1–A2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller C.C. NY Times; Oct. 14, 2014. Freezing eggs as part of employee benefits: some women see darker message.http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/15/upshot/egg-freezing-as-a-work-benefit-some-women-see-darker-message.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikhena-Abel D.E., Confino R., Shah N.J., Lawson A.K., Klock S.C., Robins J.C. Is employer coverage of elective egg freezing coercive? A survey of medical students’ knowledge, intentions, and attitudes towards elective egg freezing and employer coverage. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34:1035–1041. doi: 10.1007/s10815-017-0956-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dondorp W., de Wert G., Pennings G., Shenfield F., Devroey P., Tarlatzis B. Oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility loss. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1231–1237. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills M., Rindfuss R.R., McDonald P., te Velde E., ESHRE Reproduction and Society Task Force Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:848–860. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldwin K., Culley L., Hudson N., Mitchell H., Lavery S. Oocyte cryopreservation for social reasons: demographic profile and disposal intentions of UK users. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;31:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu L., Peterson B., Inhorn M.C., Boehm J.K., Patrizio P. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions toward fertility awareness and oocyte cryopreservation among obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:403–411. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bavan B., Porzig E., Baker V.L. An assessment of female university students’ attitudes toward screening technologies for ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:1195–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lampic C., Svanberg A.S., Karlstrom P., Tyden T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:558–564. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle J.O., Richter K.S., Lim J., Stillman R.J., Graham J.R., Tucker M.J. Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertil Steril. 2016;105:459–466.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mertes H. Does company-sponsored egg freezing promote or confine women’s reproductive autonomy? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2015;32:1205–1209. doi: 10.1007/s10815-015-0500-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.