Abstract

Patient: Female, 75-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Bacteremia • pyometra

Symptoms: Fever • vaginal discharge

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Curettage • drainage

Specialty: Infectious Diseases • Obstetrics and Gynecology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Pyometra is an accumulation of pus in the uterine cavity. It is rare in the general population but more common in elderly women. If diagnosed in the early stage, life-threating conditions may be avoided. The most common etiological microorganisms of pyometra are Escherichia coli, Bacteroides species, Staphylococci (eg, epidermidis) and Streptococci. Occasionally, atypical bacteria may be the cause.

Case Report:

We present the case of a 75-year-old woman, with multiple risk factors, admitted to the Gynecology Department with a 15-day history of yellowish-brown vaginal discharge. Because of rapid enlargement of the uterine cavity, the patient underwent to endometrial curettage. Three hours after surgery, she developed a high-grade fever, and Streptococcus constellatus was isolated in her blood cultures. A specific antibiotic therapy was administered for a total of 14 days, resulting in complete resolution of the infection.

Conclusions:

This case report describes a rare case of bacteremia caused by Streptococcus constellatus, that resulted from a pyometra. The classic triad of symptoms (postmenopausal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and lower abdominal pain) may be helpful for diagnosis; however, 50% of patients are asymptomatic. An early recognition of the condition is important to avoid rare but risky consequences, such as perforation of the uterus itself. Nevertheless, surgery can cause dangerous complications such as bacteremia. A different spectrum of bacteria may be involved in the development of pyometra, even in atypical cases, mostly when multiple comorbidities are present. A correct evaluation and management of the patient is essential to guarantee a good prognosis in this rare infection.

Keywords: Pyometra, Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus constellatus, Pelvic Infection, Bacteremia

Background

Streptococcus constellatus is a gram-positive coccus occurring in chains. Along with Streptococcus anginosus and Streptococcus intermedius, it is part of the Streptococcus anginosus group (SAG) (also known as Streptococcus milleri group), a subgroup of viridans streptococci.

S. anginosus strains belong to the normal human flora as they are usually found in the oral cavity, throat, stool, and vagina. They can cause bloodstream infections and abscesses, usually in immunocompromised patients [1,2].

Pyometra is defined as an accumulation of pus in the uterine cavity [3]. It occurs in 0.1–0.2% of all gynecology patients and 13.6% of elderly gynecology outpatients [4]. This condition may be due to cervical obstruction with superinfection of menstrual blood, normal secretions, and cellular debris, or due to necrosis of submucosal fibroids. It is usually a benign condition, sometimes associated with malignancy [5,6]. Therefore, a correct diagnosis should be performed. In rare cases, Pyometra leads to life-threatening consequences if not detected at the early stage. The accumulation of pus may evolve into spontaneous perforation of the uterus, with generalized peritonitis and possible septic shock, requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics [5–10]. On the contrary, non-ruptured pyometra is a non-urgent condition that can be managed successfully by transcervical drainage and curettage, followed by administration of targeted antibiotics and supportive care.

To the best of our knowledge, only 1 case report of pyometra caused by S. anginosus group has been documented in the literature so far [6].

We report the case of an elderly woman hospitalized for pyometra who developed an S. constellatus bacteremia after surgery.

Case Report

A 75-year-old postmenopausal woman was evaluated by her gynecologist for a 15-day history of yellowish-brown vaginal discharge. She had a medical history of diabetes mellitus type II, chronic kidney disease, ischemic heart disease, and mitral and aortic valve insufficiency. Her past gynecologic history was characterized by 2 cesarean sections.

At the transvaginal ultrasonography (US) performed by her gynecologist, copious hyperechogenic material inside the uterine cavity was found, compatible with a purulent collection (maximum diameter 18 mm). Therefore, the patient was directed to our gynecological emergency department.

At admission, the patient was apyretic, with normal white blood cell count (WBC) and negative C-reactive protein (CRP). At the vaginal examination, the external uterine orifice was stenotic, with the spillage of whitish material. Transvaginal US was performed and detected normal uterus dimensions (Figures 1, 2) but a 7-mm increase in the uterine cavity volume (from 18 mm to 29 mm in less than 12 hours) (Figure 3).

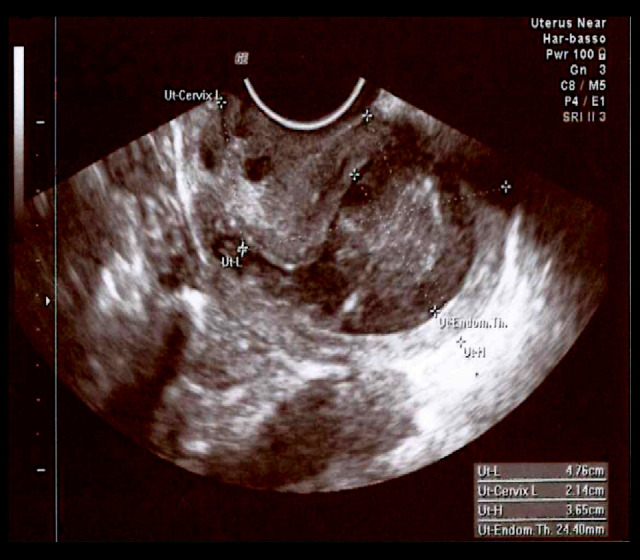

Figure 1.

Transvaginal ultrasonography: retroverted uterus, length: 47.6 mm (body)+21.4 mm (cervix), height: 36.5 mm, with an endometrial thickness of 24.4 mm.

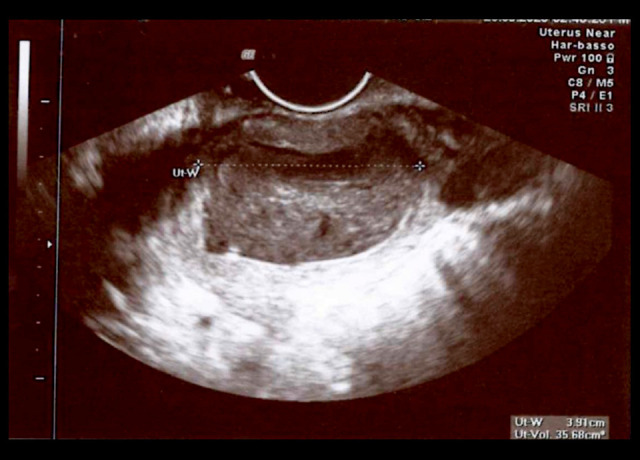

Figure 2.

Transverse plane of the uterus. Uterus width: 39.1 mm.

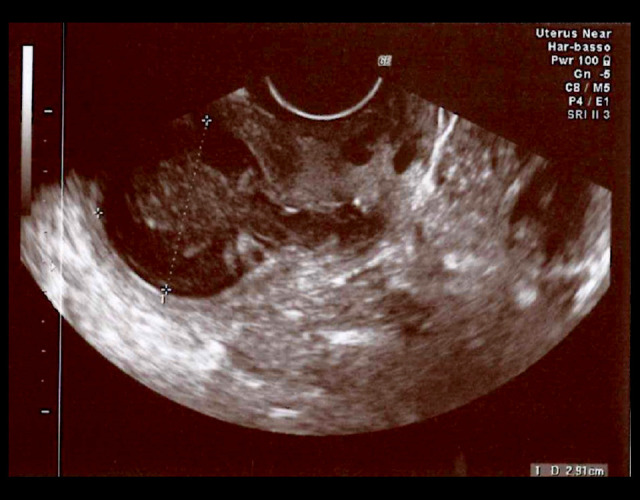

Figure 3.

The purulent collection of 29 mm (maximum endometrial thickness) inside the uterine cavity.

In view of the rapid growth of endometrial thickness, the previous cesarean sections, and her age, a dilatation and curettage (D&C) was scheduled for the next day, considering the high risk of uterine perforation.

D&C was carried out under general anesthesia. During the procedure, intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis with 600 mg of clindamycin was administered. After dilation, a large quantity of purulent and malodorous material spilled out. The histological examination excluded malignant degeneration and revealed a purulent acute phlogistic pattern, confirming the suspicion of pyometra.

Three hours later, the patient was feverish (body temperature 39.1°C); a laboratory workup revealed an increased WBC count (20.20×103/µL; neutrophils 16.70×103/µL) and CRP (67.32 mg/L). After the collection of blood cultures, empiric antibiotic therapy with 1g every 8 h of meropenem was started considering the reported allergy to cefixime (risk of cross-allergenicity with penicillin). The body temperature normalized in a few hours and no more fever episodes were observed during the hospitalization.

Two sets of blood cultures yielded S. constellatus. Considering the minor reaction reported to cefixime (no history of anaphylactic shock) and the usual susceptibility profile of S. constellatus, antibiotic therapy was shifted to 18 g of piperacillin/ tazobactam in 24 h (continuous infusion) and carried out successfully. After 11 days of intravenous antibiotic therapy and microbiological eradication (as evidenced by negative blood cultures), the patient was discharged on the 10th postoperative day, and the therapy was completed with 4 more days of 1 g every 8 h of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid orally administered. A gynecologic visit and ultrasound were performed after 12 days, showing total resolution of the condition. Considering the patient’s medical history of mitral and aortic valve insufficiency and the ability of S. constellatus to form abscesses [11], an echocardiography was performed 5 weeks after surgery; it revealed no cardiac vegetations or abscesses.

Discussion

Pyometra is defined as a collection of purulent material in the uterine cavity [3]. Cervical canal obstruction can lead to this condition, interfering with normal uterine drainage and increasing susceptibility to infections [7,12] Postmenopausal women often have a high incidence of stenosis and no obvious clinical manifestations.

Possible causes of this purulent accumulation include both malignancy (carcinoma) and benign conditions (endometrial polyp and leiomyoma, senile cervicitis, congenital malformations, a forgotten intrauterine device, postoperative cervical occlusion, and radiation) [5,6] Consequently, the histological analysis is mandatory. Generally, the most common etiological microorganisms causing pyometra are E. Coli, Bacteroides species, Staphylococci (eg, epidermidis), and Streptococci. More rarely, Klebsiella, Acinetobacter, and Actinomyces species have been isolated [6,8].

As for other infections, patient’s comorbidities may play an important role as risk factors. In particular, diabetes, renal failure, restricted mobility, cognitive deterioration, poor hygiene, compromised immunity, age-related genital tract atrophy, and uterine circulatory insufficiency seem to be associated with pyometra [7,12]. Comorbidities may compromise the immunological state of the patient, favoring the infection, but also may influence antibiotic and surgery treatment.

In the case reported here, the patient had several risk factors (diabetes mellitus type II, chronic kidney disease, 2 past cesarean sections) which may have contributed to the development of infection. She was asymptomatic for lower abdominal pain; therefore, she underwent transvaginal US only 2 weeks after symptom onset; meanwhile, the purulent material dangerously enlarged the uterus.

Although none of these symptoms are specific for pyometra, the classic triad is postmenopausal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and lower abdominal pain. Nevertheless, 50% of patients are asymptomatic at diagnosis. A potential rare and serious complication is spontaneous perforation of the uterus caused by a progressive and asymptomatic enlargement of the organ, which can result in a generalized peritonitis [8,9].

Elective D&C should be generally avoided in patients with cervical or uterine infection because it can cause ascending infection, pelvic inflammatory disease, or development of intrauterine adhesions or uterine rupture. However, pyometra (together with septic abortion or endometritis with suspected retained products of conception) is an exception to this general recommendation [13]. Since an active pelvic infection represents a contraindication to hysteroscopy, it was not considered as a possible treatment [14].

Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered intraoperatively but did not avoid the spreading of the infection: the bacteremia that occurred after the procedure was likely to be a complication of D&C itself. Clindamycin is effectively active against the S. anginosus group, although a resistance rate between 14% and 16.6% was documented in some countries [15,16]. The prevalence of resistant strains varies by geographic locations, patient age, and risk factors (eg, recent hospitalization, long antibiotic treatments, comorbidities).

The absence of a microbiological analysis of the purulent discharge did not allow us to formulate a hypothesis about the source of the bloodstream infection; however, the S. constellatus bacteremia probably originated from the uterus and was less likely to have had a urinary or gastrointestinal focus.

The members of the SAG, such as S. constellatus, reside as commensal organisms in the flora of the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract and they are rarely reported as relevant pathogens [2,17]. However, our patient presented with a uterine collection also documented at the histological examination, and the number of cases in which SAG have a pathogenic role in abscesses and blood cultures is increasing [2,17,18]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, only 1 case report of pyometra caused by S. anginosus group has been documented in literature so far, with a presentation totally different from the one described here. Actually, in the case reported by Abu-Zaid et al, the patient presented to the emergency department with a generalized peritonitis, an exceedingly uncommon but extremely dangerous complication of pyometra [5-10].

SAG infections often involve the oral cavity, head and neck, or the gastrointestinal tract and they are usually polymicrobial, including anaerobes and members of the Enterobacteriaceae family [2]. It is known that the propensity of SAG to cause abscess is unique and sets them apart from the rest of the viridans streptococci groups [2,17,18]. Bloodstream infections caused by SAG are rare and usually opportunistic. SAG can spread hematogenously to cause metastatic abscesses in the brain, subdural space, liver, spleen, bone, ands heart valves [1,2,11].

Endocarditis can occur in patients with abnormal heart valves [19,20]. Due to our patient’s history of mitral and aortic valve insufficiency, she underwent an echocardiography, which did not show valve abnormalities or cardiac abscesses. As proven by the literature, endocarditis is uncommon, even with high-rate bacteremia and with risk factors. In the absence of endocarditis or distant focal suppurative complications, bloodstream infections by SAG have a good prognosis [2].

Considering the positive blood cultures and the patient’s risk of endocarditis, the antibiotic therapy was carried out for a total of 15 days (11 days intravenously and 4 day orally) [21,22].

Antimicrobial susceptibility data from the literature suggest that nearly all isolates of the S. anginosus group are susceptible to amoxicillin and penicillin [15,16,19,20], although a few penicillin-resistant strains have been encountered [15,16,18]. This suggests that, with proper microbiological intraoperative and postoperative investigations, broad-spectrum antibiotics are usually not needed, and targeted therapy can be performed.

Conclusions

We presented an extremely rare case of pyometra caused by S. constellatus, and this is only the second such case to be published. A different spectrum of bacteria could be involved in the development of the uterine collection, even atypical ones. At present, the literature contains no confirmed recommendations about pyometra, but a histological examination is essential to exclude malignancy. A limitation of this case report is that a specimen was not collected for culturing. Microbiological insight might have been helpful in the identification of the pathogen, considering that an invasive infection could have spread. When a rapidly growing intrauterine collection is detected, it is important to take action promptly, avoiding unfavorable consequences, which may be life-threating and may need a more invasive surgical management.

References:

- 1.Jiang S, Li M, Fu T, et al. Clinical characteristics of infections caused by Streptococcus anginosus group. Sci Rep. 2020 Jun 3;10(1):9032. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-65977-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Majid F, Aldrees A, Barry M, et al. Streptococcus anginosus group infections: Management and outcome at a tertiary care hospital. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(11):1749–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muram D, Drouin P, Thompson FE, Oxorn H. Pyometra. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;125:589–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawabe M, Takubo K, Esaki Y, et al. Spontaneous uterine perforation as a serious complication of pyometra in elderly females. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;35(1):87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1995.tb01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malvadkar SM, Malvadkar MS, Domkundwar SV, Mohd S. Spontaneous rupture of pyometra causing peritonitis in elderly female diagnosed on dynamic transvaginal ultrasound. Case Rep Radiol. 2016;2016:1738521. doi: 10.1155/2016/1738521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abu-Zaid A, Alomar O, Nazer A, et al. Generalized peritonitis secondary to spontaneous perforation of pyometra in a 63-year-old patient. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:929407. doi: 10.1155/2013/929407. Erratum in: Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014:2014;180867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yildizhan B, Uyar E, Sişmanoğlu A, et al. Spontaneous perforation of pyometra. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2006:26786. doi: 10.1155/IDOG/2006/26786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitai T, Okuno K, Ugaki H, et al. Spontaneous uterine perforation of pyometra presenting as acute abdomen. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:738568. doi: 10.1155/2014/738568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saha PK, Gupta P, Mehra R, et al. Spontaneous perforation of pyometra presented as an acute abdomen: A case report. Medscape J Med. 2008;10(1):15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gita R, Jain K, Vaid NB. Spontaneous rupture of pyometra. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1995;48(1):111–12. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)02241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Claridge JE, 3rd, Attorri S, Musher DM, et al. Streptococcus intermedius, Streptococcus constellatus, and Streptococcus anginosus (“Streptococcus milleri group”) are of different clinical importance and are not equally associated with abscess. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(10):1511–15. doi: 10.1086/320163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan LY, Lau TK, Wong SF, Yuen PM. Pyometra. What is its clinical significance? J Reprod Med. 2001;46(11):952–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braaten K P, Dutton C. Up-to-date, Dilatation and curettage – contraindications – precautions – pelvic infection. 2020 https:www.upto-date.com/contents/dilation-and-curettage?search=piometra&source=search_result&selectedTitle=3~8&usage_type=default&display_rank=3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Use of Hysteroscopy for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Intrauterine Pathology: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 800. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(3):e138–48. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tracy M, Wanahita A, Shuhatovich Y, et al. Antibiotic susceptibilities of genetically characterized Streptococcus milleri group strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(5):1511–14. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1511-1514.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Limia A, Jiménez ML, Alarcón T, et al. Five-year analysis of antimicrobial susceptibility of the Streptococcus milleri group. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(6):440–44. doi: 10.1007/s100960050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asam D, Spellerberg B. Molecular pathogenicity of Streptococcus anginosus. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2014;29(4):145–55. doi: 10.1111/omi.12056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohanty S, Panigrahi MK, Turuk J, Dhal S. Liver abscess due to Streptococcus constellatus in an immunocompetent adult: A less known entity. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018;110(6):591–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bert F, Bariou-Lancelin M, Lambert-Zechovsky N. Clinical significance of bacteremia involving the “Streptococcus milleri” group: 51 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(2):385–87. doi: 10.1086/514658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gossling J. Occurrence and pathogenicity of the Streptococcus milleri group. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(2):257–85. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belko J, Goldmann DA, Macone A, Zaidi AK. Clinically significant infections with organisms of the Streptococcus milleri group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21(8):715–23. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200208000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giuliano S, Rubini G, Conte A, et al. Streptococcus anginosus group disseminated infection: Case report and review of literature. Infez Med. 2012;20(3):145–54. Erratum in: Infez Med. 2012;20(4): 316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]