Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the prevalence of advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives in Austrian intensive care units (ICUs), and to explore barriers faced by adults engaged in the contemplation and documentation phase of the advance care planning process.

Methods

Two studies were conducted: (1) A 4-week multicenter study covering seven Austrian ICUs. A retrospective chart review of 475 patients who presented to the ICUs between 1 January 2019 and 31 January 2019 was conducted. (2) An interview and focus group study with 12 semi-structured expert interviews and three focus groups with 21 adults was performed to gain insights into potential barriers faced by Austrian adults planning medical decisions in advance.

Results

Of the 475 ICU patients, 3 (0.6%) had an advance directive, 4 (0.8%) had a healthcare proxy, and 7 (1.5%) had a legal guardian. Despite the low prevalence rates, patients and relatives reacted positively to the question of whether they had an advance directive. Patients older than 55 years and patients with children reacted significantly more positively than younger patients and patients without children. The interviews and focus groups revealed important barriers that prevent adults in Austria from considering planning in advance for potentially critical health states.

Conclusion

The studies show low prevalence rates of healthcare documents in Austrian ICUs. However, when patients were asked about an advance directive, reactions indicated positive attitudes. The gap between positive attitudes and actual document completion can be explained by multiple barriers that exist for adults in Austria when it comes to planning for potential future incapacity.

Keywords: Advance care planning, Advance directives, Decision-making, Intensive care units

Introduction

In intensive care medicine, many patients are impaired in their decision-making capacity.1 The need to make treatment decisions in the intensive care unit (ICU), however, is often considerable.2 In situations where patients cannot decide for themselves, instruments such as advance directives, healthcare proxies, or legal representatives can help to guide towards medical care that is consistent with patient preferences3,4. The instruments are completed after an advance care planning process of reflection and discussion about personal values, wishes, and preferences regarding future medical decisions.5,6

Notwithstanding the possibilities to plan in advance, the number of people who complete those instruments remains limited, with varying degrees between Western countries. A retrospective matched-cohort study conducted in four US American ICUs from December 2010 to December 2011 showed that 13% of patients had an advance directive.7 In Germany, a single center cross-sectional study in the intensive care context conducted from November 2013 to July 2014 demonstrated that 31.7% of patients had an advance directive reported in the electronic patient record.8 In Slovenian ICUs, in 2013, advance directives were present for 1.9% of patients.9

Previous research in Austria indicates low single digit prevalence rates of advance directives. In a survey conducted among the general Austrian population in 2014, 4.1% of participants reported having an advance directive.10 In the oncological and hematological context, a single-center cohort study in 2007 found that 5% of patients had an advance directive.11 In ICUs, a survey among 139 physicians conducted in 2008 revealed that 66.2% of physicians had experienced at least one advance directive case in two years, but only 9.6% of them had dealt with more than ten cases in two years,12 indicating a limited uptake and use of advance directives.

In Austria, two types of advance directives exist: binding and non-binding advance directives.13 Whereas physicians are legally bound to comply with binding advance directives, they are not obliged by law to comply with non-binding advance directives. To complete a binding advance directive, medical and legal consultation is required.14 The resulting costs are not covered by the healthcare system but are considered a private service. However, most patient advocacy organizations in Austria offer the legal consultation for advance directives free of charge.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Non-binding advance directives do not require medical and legal consultation by law.

Self-report surveys revealed that people residing in Austria mainly abstain from completing advance directives because they have high trust in physicians and they wish to receive maximum therapy.10,11 Other factors include a lack of time to complete the documents, distrust in physicians, no perceived relevance due to young age and good health and the belief that relatives will make the decisions on behalf of the patient in critial situations.10,11 The barriers were assessed based on closed-ended answer choices, even though little prior qualitative research exists that has explored peoples’ perspectives and perceptions in-depth. In addition, barriers to the early stages of the decision-making process were not considered.

The aims of the present research are twofold: (1) To investigate the prevalence of advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives in Austrian ICUs, and (2) to explore barriers faced by adults engaged in the contemplation and documentation phase of the advance care planning process.

Methods

Study 1

Primary care physicians of anaesthesiology departments in Austrian hospitals were informed and invited for study participation via the Austrian Society for Anaesthesia, Resuscitation and Intensive Care. Sixteen ICUs initially agreed to participate in the study. Intensive care patients on these ICUs in the period from 1 January 2019 until 31 January 2019 were eligible for the study. A retrospective chart review of eligible patients was conducted. This involved an examination of the patient files and completion of the case report form (CRF) for each patient. The CRF specifically developed for this study included items on the presence of advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives; reaction of patients, relatives and physicians to the question of whether patients had an advance directive; socio-demographic information; diagnosis (ICD codes); content and structure of the healthcare documents; impact on treatment; and document limitations. Advance directive prevalence was assessed based on actual submission of completed documents to the ICU team. The reaction of patients, relatives, and physicians to the question of healthcare documents was prospectively assessed on a 10-point semantic differential scale (“reluctant” – “positive”) taken from a previous study.21 After the survey period, seven ICUs returned the CRFs (type of hospital: public (n = 6), university (n = 1); type of ICU: level 3 ICU (n = 7). Descriptive statistics and independent-samples t-test were calculated in IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05. Values are expressed as absolute numbers, percentages and mean values (M) with standard deviation (SD). Two variables were omitted from the analysis due to the large amount of missing values: physicians’ reaction to the question on healthcare documents (445 patients, 93.7%) and diagnosis (ICD codes) (247 patients, 52%). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee in Klagenfurt, Austria (Reference MZ23/18).

Study 2

In order to investigate the barriers faced by private individuals in Austria to develop and document treatment preferences for future medical scenarios, qualitative research was conducted. Primary data were gathered through 12 semi-structured interviews with experts from healthcare, jurisdiction, and charitable organizations, and three focus groups with a total of 21 adults residing in Austria. The interviews and focus groups were held between 16 October 2018 and 11 December 2018. They were conducted in the German language, following a previously developed interview guideline based on the advance care planning process.6 Informed consent in writing was obtained from all individual participants. The interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim. Qualitative content analysis with inductive category development was applied as data analysis method.22 NVivo 12 Plus (QSR International, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) was used for data management and analysis.

Results

Study 1

The final sample consisted of 475 ICU patients. The socio-demographic patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n = 472) | ||

| Male | 306 | 64.8 |

| Female | 166 | 35.2 |

| Age (yrs) (mean, range) (n = 470) | 67.3, 17-99 | |

| <20 | 3 | 0.65 |

| 20-29 | 7 | 1.5 |

| 30-39 | 14 | 3.0 |

| 40-49 | 24 | 5.1 |

| 50-59 | 72 | 15.3 |

| 60-69 | 106 | 22.6 |

| 70-79 | 173 | 37.0 |

| 80-90 | 64 | 13.6 |

| >90 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Marital status (n = 459) | ||

| Married | 262 | 57.1 |

| Single | 87 | 18.9 |

| Divorced | 42 | 9.2 |

| Widowed | 65 | 14.2 |

| Non-marital partnership | 3 | 0.7 |

| Children (n = 408) | ||

| Yes | 313 | 76.7 |

| No | 95 | 23.3 |

| Religion (n = 450) | ||

| Catholic | 305 | 67.8 |

| Protestant | 32 | 7.1 |

| Muslim | 7 | 1.6 |

| Atheist | 7 | 1.6 |

| Other/None | 99 | 22 |

| Admission to the ICU (n = 479)a | ||

| Emergency | 278 | |

| Elective admission | 189 | |

| Appallic syndrome | 2 | |

| Final stage of terminal illness | 6 | |

| Terminal phase | 4 | |

Multiple answers possible.

Document prevalence

The presence of advance directives was assessed at multiple time points during the patients’ stay in the ICU. Within the first 24 h of intensive care therapy, 0.6% of patients (n = 3) had an advance directive, 98.5% of patients (n = 468) did not have an advance directive, and for 0.8% of patients (n = 4), it was not specified. All three advance directives were non-binding. No advance directives were submitted at a later time point. Healthcare proxies were submitted for 0.8% of patients (n = 4) within the first 24 h in the ICU. 98.5% of patients did not have a healthcare proxy on the first day of therapy and for 0.6% (n = 3), it was not specified. No healthcare proxies were submitted later in the study period. Of the three patients who had an advance directive and four patients who had a healthcare proxy, one patient had both documents. For 1.5% of patients (n = 7), a legal representative was registered. Most of them were statutory representatives (n = 5), one was an elected representative, and one a court-appointed representative. For most of these patients (n = 4), the legal representative was appointed during the first and third week of intensive care. For the other patients, the legal representative was known within the first 24 h in the ICU (n = 1) or between the second and seventh day of intensive care therapy (n = 1). For one patient, the time point was not documented on the CRF. No patient with a legal representative had an advance directive. In total, only 0.6% of ICU patients had an advance directive (n = 3), 0.8% of patients had a healthcare proxy (n = 4), and 1.5% had a legal representative (n = 7).

Reaction

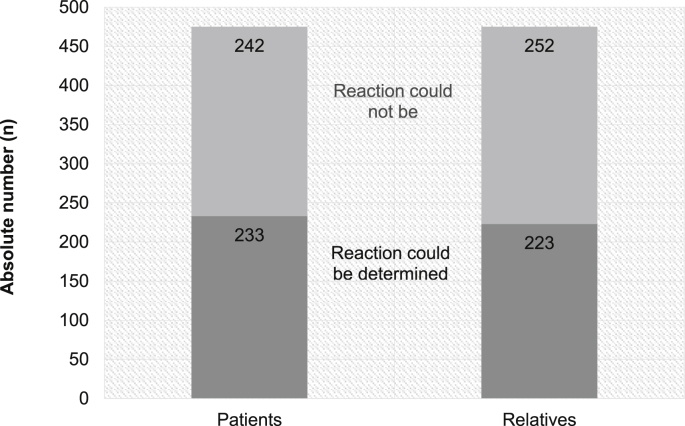

The reaction of patients (n = 233) to the question of whether they had an advance directive was generally positive (M = 6.79, SD = 1.89). Patients older than 55 years reacted signficantly more positively than patients aged 55 years and younger (p ≤ 0.05; older than 55: M = 6.93, SD = 1.76; 55 and younger: M = 6.23, SD = 2.24). Additionally, patients with children reacted significantly more positively to the question of documents compared to patients without children (p ≤ 0.05; with children: M = 6.96, SD = 1.86; without children: M = 6.25, SD = 1.95). For 242 of patients (51%), the reaction could not be assessed because the patients were either sedated, they were transferred to another unit after initial treatment or they died before the question could be asked, among other reasons (Fig. 1). Similar to patients, the reaction of relatives (n = 223) to the question of healthcare documents was positive overall (M = 6.74, SD = 1.95). Relatives aged 65 and older reacted more positively to the question of advance directives than relatives below the age of 65 (p ≤ 0.05; 65 and older: M = 6.94, SD = 2.05; younger than 65: M = 6.39, SD = 1.73). In 252 of cases (53%), the reaction of relatives to the question of whether their family member had an advance directive could not be determined (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Absolute number of patients and relatives for whom a reaction to question of whether they had an advance directive could be determined or not determined.

Study 2

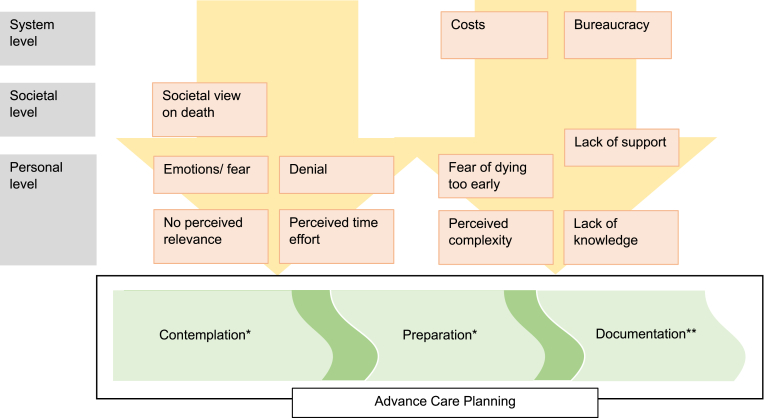

Twelve in-depth expert interviews and three focus groups were conducted. Participant details are illustrated in Table 2. In total, 307 min of interview data and 197 min of focus group data were collected. Through qualitative content analysis, eleven barriers were synthesized that relate to either to the contemplation and preparation process or the documentation process. Barriers were identified on the level of the society, of the system, and on the personal level (Fig. 2). Table 3 presents quotes for each barrier category.

Table 2.

Interview and focus group participant characteristics.

| Expert | Gender | Abbrev. |

|---|---|---|

| Physician | m | Doc1 |

| Physician | m | Doc2 |

| Physician | f | Doc3 |

| Physician | m | Doc4 |

| Physician | f | Doc5 |

| Nurse | f | Nurse1 |

| Social worker | f | Socwork1 |

| Notary | m | Not1 |

| Lawyer | F | Lawy1 |

| Charitable organization | F | Char1 |

| Charitable organization | F | Char2 |

| Charitable organization |

F |

Char3 |

|

Focus group |

Gender, Age |

Abbrev. |

| 20–39 years | m, 33 | M33 |

| 20–39 years | m, 31 | M31 |

| 20–39 years | m, 28 | M28 |

| 20–39 years | w, 38 | W38 |

| 20–39 years | w, 34 | W34 |

| 20–39 years | w, 29 | W29 |

| 40–59 years | w, 44 | W44 |

| 40–59 years | w, 57 | W57 |

| 40–59 years | w, 51 | W51 |

| 40–59 years | w, 48 | W48 |

| 40–59 years | m, 41 | M41 |

| 40–59 years | m, 59 | M59 |

| 60–94 years | w, 94 | W94 |

| 60–94 years | w, 63 | W63 |

| 60–94 years | w, 75 | W75 |

| 60–94 years | m, 78 | M78 |

| 60–94 years | w, 64 | W64 |

| 60–94 years | w, 53a | W53 |

| 60–94 years | w, 87 | W87 |

| 60–94 years | m, 65 | M65 |

| 60–94 years | w, 72 | W72 |

A carer of an elderly participant took part in the discussion.

Fig. 2.

Barriers to contemplation, preparation and documentation of advance care planning6 constructed from the analysis. ∗ Reflection, identification of values and treatment preferences; ∗∗ Completion of advance directives.

Table 3.

Barriers with examples.

| Barriers to contemplation and preparation | |

|---|---|

| Societal view on death | “Our society has forgotten how to accept the natural course of life that includes illness and death” (Char3) “We are led to believe that we can live as if there is no end” (Char3) “In our society, everyone is young, dynamic, healthy; people are not concerned with questions about: what if? People do not occupy themselves with illness and death; not with their own death and not with the death of close relatives” (Doc1) “We have a complete societal problem” (Doc1); “For us [in our society], death is associated with panic, grief, fear; it is a taboo topic” (W34) |

| No perceived relevance | “This [the end of life] is something that’s so far away. That’s why I don’t feel the urge of thinking about it now” (W29) “That’s something I’ll deal with in 20 or 15 years” (W51); “Nothing serious ever happened to me” (W44) “I think when I’m physically and mentally not capable anymore, what will happen to me doesn’t matter anyway” (W63) “That’s something I’m still too young to consider” (W64); “Many people think: Nothing will ever happen to me” (M65) |

| Denial | “People refuse to accept that life has an end. They refuse to accept that there should be preparations for the end of life” (Char3) “I have denied it, that’s for sure” (M78); “We all deny it” (W51); “Honestly, everyone denies the topic [end of life]. We do not think about what could happen to us next time we walk across the street; that we might get hit by a motorcycle and become seriously injured and heavily care-dependent” (Char1) |

| Perceived time effort | “It is not something that is done in an hour. It probably takes days or weeks, or I don’t know how long it takes [to identify the medical preferences]” (M33) |

| Emotions/Fear | “I think that many people shy away from it” (Doc3); “People are afraid of dying; not the fact that they have to die but the way of dying” (Doc2) “The majority of people are still afraid of the end of life and of dying. They do not want to be confronted with it” (Char2) “Do I really want to think about such a dark topic? A topic that will heavily depress my mood?” (M33); “Death is always connected to fear” (W51) “Suffering, pain; that causes fear. If you know there is something ahead that will bring suffering, then you are afraid of it” (W48) “I think it’s an emotional topic” (Doc4) |

| Barriers to documentation | |

| Costs | “I don’t know exactly how much it [a binding advance directive] costs, 100 or 200 EUR? For many of my patients this is a barrier” (Doc3) “Sure, it is a financial burden” (Doc5); “Advance directives and healthcare proxies are definitely too expensive. For the average person, 400 Euros for an advance directive is a fortune” (Doc1) “Many people are deterred by the costs. I think the costs are a very big hurdle” (Lawy1); “So expensive?” (W72) “What a cheek!” (M78) |

| Bureaucracy | “There are bureaucratic barriers and the differentiation between binding and non-binding advance directive is also related” (Doc2) “There are big hurdles to make an advance directive binding” (Doc3)∗; “For sure there are structural barriers” (Doc3) “Having to talk to doctors” (M33); “A hurdle, having to go to the notary” (W57) |

| Fear of dying too early | “Maybe people are afraid of receiving no intensive care at all if they state [in an advance directive], for example, that they don’t want to receive mechanical ventilation over a longer period of time” (Doc3) “Probably we are afraid that something [the end of life] might come too soon; that doctors withhold a therapy thinking they are doing good by releasing me from suffering, without knowing what I actually want in this situation” (W48) |

| Lack of knowledge | “This [the possibility of making an advance directive] is not something the majority of the public knows about” (Char3) “Even some people in the healthcare sector or in social services departments don’t know about advance directives” (Char3) “Many people don’t know that the non-binding advance directive is sufficient” (Doc5) “What does it [binding advance directive] cost?” (W57); “Is it a checklist or do I have to formulate it by myself?” (W57); “Healthcare proxy?” (W48); “Where is the difference?” (W29); “Let’s say I have an accident, I arrive at the hospital; how do the doctors know I have an advance directive? What happens when my husband brings it to the hospital 3 days later? Do the doctors have to withdraw treatment then?” (M59) |

| Lack of support | It would be necessary that [adult] children or other family members say: "Have you thought about making an advance directive? We can help you to make an appointment at the notary or drive you there, in case you need and help." And if no one offers this support, nothing happens (Doc3) |

| Perceived complexity | “The formulations, very complicated. You have to anticipate every possible scenario. With let’s say 15 standardized formulations, such as I don’t want any life-prolonging measures when I’m ill, this is not possible. Such formulations are useless” (Doc2); “That’s too, that sounds too complicated” (W48) |

∗ Binding advance directives can be registered in one of the two central registers for binding advance directives in Austria, the advance directive register of the Austrian lawyers (“Patientenverfügungsregister der österreichischen Rechtsanwälte”) or the advance directive register of the Austrian notaries (“Patientenverfügungsregister des österreichischen Notariats”). In cooperation with the Austrian Red Cross, hospitals in Austria have access to both registries.

Barriers to contemplation and preparation

The societal view on death was identified as a barrier that prevents people from thinking about potential end-of-life wishes. The way society deals with and thinks about the end of life influences individuals in their willingness to contemplate about critical health states. Experts and private individuals noted that death is a taboo topic in society. For example,

Doc1: “In our society, everyone is young, dynamic, healthy; people are not concerned with questions about: what if? People do not occupy themselves with illness and death; not with their own death and not with the death of close relatives”

Participants also noted that planning is irrelevant for them due to a long perceived distance to the end of life. Good perceived health status and young perceived age occurred as indicators. Focus group participants across all three age groups noted this phenomenon.

W51: “That’s something I’ll deal with in 20 or 15 years”; M65: “Many people think: Nothing will ever happen to me”; W64: “That’s something I’m still too young to consider”

Some participants also felt indifferent about the type of end-of-life care they might receive, and therefore did not consider reflecting about end-of-life wishes. For example,

W63: “… what will happen to me doesn’t matter anyway”

Another occurring theme was denial. Focus group participants mentioned that they deny the fact that life has an end and they do not feel susceptible to serious injury or illness. Experts also identified denial as a key barrier for end-of-life planning. For example,

Char3: “People refuse to accept that life has an end. They refuse to accept that there should be preparations for the end of life”; M78: “I have denied it, that’s for sure”

High perceived time effort also emerged as an influencing factor on the willingness to reflect and clarify possibilities and treatment preferences for situations of impaired capacity:

M33: “It is not something that is done in an hour. It probably takes days or weeks, or I don’t know how long it takes [to identify medical preferences for the context close to the end of life]”

In focus groups and expert interviews, negative emotions associated with dying were identified that restrain people from thinking about potential end-of-life situations or medical scenarios. Fear occurs as a strong emotion that seems to be elicited when thinking about states of mental and physical incapacity, dying, and death:

M33: “Do I really want to think about such a dark topic? A topic that will heavily depress my mood?”; Doc2: “People are afraid of dying; not the fact that they have to die but the way of dying”

Barriers to documentation

In addition to the barriers related to the contemplation of treatment preferences, the documentation phase bears its own hindering factors. Two system-related barriers were identified: costs and bureaucracy. The costs of arranging a binding advance directive and healthcare proxies were perceived as a considerable barrier mentioned by both experts and focus group participants. Similarly, the medical and legal consultation for a binding advance directive was perceived as a hindrance.

Doc1: “Advance directives and healthcare proxies are definitely too expensive. For the average person, 400 Euros for an advance directive is a fortune”

Another important and omnipresent theme is lack of knowledge. People are not well informed about advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives:

Char3: “This [the possibility of making an advance directive] is not something the majority of the public knows about”; “Even some people in the healthcare sector or in social services departments don’t know about advance directives”

A further barrier to documenting preferences was the fear of withheld or withdrawn therapy against the patient’s wishes. Noted by an expert and by focus group participants, there seems to be a concern that the patient’s wishes in real medical situations might differ from the documented wishes. As a consequence, people fear that therapies might be withdrawn or withheld based on a document that does not represent their current wishes. Therefore, they abstain from document completion.

W48: “Probably we are afraid that something [the end of life] might come too soon; that doctors withhold a therapy thinking they are doing good by releasing me from suffering, without knowing what I actually want in this situation”

Based on experiences, a physician noted that a lack of support can impede elderly people in documenting their wishes formally. Without the help of others, e.g. family members, elderly people might have restricted possibilities to create legally binding documents. For example,

Doc3: It would be necessary that [adult] children or other family members say: "Have you thought about making an advance directive? We can help you to make an appointment at the notary or drive you there, in case you need any help." And if no one offers this support, nothing happens”

Discussion

The clinical study showed that advance directives were rarely present in patients admitted to Austrian ICUs. The actual overall prevalence rate of advance directives was found to be only 0.6%, hence, much lower than the rate reported in previous studies in Austria that relied on self-reported data.10,11 Compared to two-digit rates in the others countries such as the United States7 or Germany,8 the present findings illustrate that advance directives seem to be a marginal phenomenon in Austrian ICUs. This accords with results for Slovenian ICUs.9 Healthcare proxies and legal representatives were submitted more often than advance directives, however, still at very low rates.

The reactions of patients and relatives to the question of whether they had an advance directive were generally positive and not reluctant. This finding differs to that of an Austrian clinical study that found a high rejection of advance directives.11 However, the latter study was conducted about ten years ago; the possibility to complete advance directives was relatively new in Austria at that time. The present study’s findings revealed significantly more positive attitudes towards advance care planning documents, particularly for patients older than 55 years and for patients with children. These findings broadly support the work of other studies, which found that higher age23,24 and higher age and children25 were factors positively related to advance directive completion.

Still, the generally positive reactions of patients and relatives in the present study are interesting, considering the very low rates of actual use. This discrepancy between peoples’ attitudes and actual behavior highlights the complexity of the phenomenon and indicates the existence of barriers that prevent people from actively engaging in anticipatory planning. The identification of eleven barriers demonstrates forces which seem to hinder people in Austria from engaging in advance care planning. The influences relate to the phase of document completion, but also to the contemplation process prior to documentation.

As a central barrier category to completing legal forms, lack of knowledge occurred. This finding is consistent with other studies, which showed that people in Austria feel uninformed about advance directives.10,11 Additionally, the barrier category “fear of dying too early” is in accord with previous study findings that indicate distrust in physicians as a reason for not completing advance directives.10,11

The present qualitative study showed that “no perceived relevance” was an essential barrier category. This corroborates earlier findings, which demonstrated that people in Austria do not complete advance directives because it is “not an important topic at the moment (too young and optimistic)”.11 By taking a nuanced perspective to the advance care planning process,6 the present study revealed that “no perceived relevance” does not directly occur as a barrier to the documentation phase but rather to the contemplation phase of advance care planning (Fig. 2). People who feel young and healthy do not seem to reflect about treatment preferences for end-of-life care. These results are in agreement with the significantly more positive reactions of older people and relatives to the question of whether they have completed an advance directive.

Interestingly, no evidence of the most common barriers of previous studies, the wish to receive maximum therapy10 and a high trust in physicians,11 was detected in this study. Due to the closed-ended survey questions in the previous studies, respondents might have been limited in their ability to express their true thoughts and attitudes.

Across the interview and focus group data, psychosocial factors were identified that influence people’s willingness to start the reflection process about future treatment preferences, including the societal stance on death, denial, and negative emotions. These barriers were not identified before in studies that investigated advance directive completion in Austria, however, they match those of previous studies conducted in other Western countries such as Australia,26 the United States,27 or Canada.28

Lack of support by family members for elderly people was mentioned as a barrier to formally issuing advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives. As in Study 1, patients with children reacted significantly more positively to the question of healthcare documents, indicating the central role of children in the context of advance care planning. In this vein, a recent study that explored the concept of “good dying” in Austria showed that family networks play a central role.29

By investigating advance directive prevalence in seven Austrian ICUs over a multi-week period and by exploring Austrian adults’ barriers in relation to the advance care planning process, the studies offer unique insights. Still, the research has several limitations. The results from Study 1 are bound to the ICU context, accordingly, investigating advance directive prevalence in other medical contexts may warrant further research. Of the 16 ICUs that initially agreed to participate in Study 1, only seven ICUs returned the CRFs. In addition, over 50% of patients in the sample were admitted to one clinical center. Due to the large amount of missing values for two items, these were omitted from the analysis. Besides, because of the low number of advance directives in the sample, no further analysis of document content and structure, and their impact on treatment were conducted. Study 2 yielded interesting findings regarding barriers to advance care planning, however, due to the qualitative nature of the study, the results are not generalizable.

Conclusion

Advance directives, healthcare proxies, and legal representatives rarely occur in Austrian ICUs. Less than one percent of patients presented either an advance directive or a healthcare proxy and less than 2 percent had a legal representative. The positive reactions of patients and relatives to the question of whether they had an advance directive indicate that, in general, attitudes towards advance care planning documents are positive. In order to increase engagement in advance care planning in the future, the identified barriers need to be addressed.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no overlap with previous publications and they don’t have any conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the permission granted by Miha Orazem, Urh Groselj, Manca Stojan, Neza Majdic, Gaj Vidmar, and Stefan Grosek for using their questionnaire form as basis for the development of the case report form for this research.

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, to drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and made a final approval of the version which is submitted.

References

- 1.Cohen S., Sprung C., Sjokvist P. Communication of end-of-life decisions in European intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31(9):1215–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, et al, For the ethicus study G (2003) end-of-life practices in European intensive care UnitsThe ethicus study. J Am Med Assoc 290 (6):790-797. doi:10.1001/jama.290.6.790 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bischoff K.E., Sudore R., Miao Y., Boscardin W.J., Smith A.K. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209–214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lautrette A., Peigne V., Watts J., Souweine B., Azoulay E. Surrogate decision makers for incompetent ICU patients: a European perspective. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14(6):714–719. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283196319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sudore R.L., Lum H.D., You J.J. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53(5):821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudore R.L., Schickedanz A.D., Landefeld C.S. Engagement in multiple steps of the advance care planning process: a descriptive study of diverse older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(6):1006–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartog C.S., Peschel I., Schwarzkopf D. Are written advance directives helpful to guide end-of-life therapy in the intensive care unit? A retrospective matched-cohort study. J Crit Care. 2014;29(1):128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Heer G., Saugel B., Sensen B., Rübsteck C., Pinnschmidt H.O., Kluge S. Advance directives and powers of attorney in intensive care patients. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(21):363–370. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orazem M., Groselj U., Stojan M., Majdic N., Vidmar G., Grosek S. End-of-life decisions in 34 Slovene Intensive Care Units: a nationwide prospective clinical study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(7):728–736. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11711-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Körtner U., Kopetzki C., Kletečka-Pulker M., Kaelin L., Dinges S., Leitner K. Rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen und Erfahrungen bei der Umsetzung von Patientenverfügungen: folgeprojekt zur Evaluierung des Patientenverfügungsgesetzes (PatVG) - endbericht August 2014. 2014. https://www.oegern.at/wp/wp-content/uploads/studie_patientenverfuegung_patvgii_15.12.2014.pdf

- 11.Kierner K.A., Hladschik-Kermer B., Gartner V., Watzke H.H. Attitudes of patients with malignancies towards completion of advance directives. Support Care Canc. 2010;18(3):367–372. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0667-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaden E., Herczeg P., Hacker S., Schopper A., Krenn C.G. The role of advance directives in end-of-life decisions in Austria: survey of intensive care physicians. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs . 2019. Advance Health Care Directive (Or Living Will)https://www.bmeia.gv.at/en/travel-stay/living-abroad/documents-civil-status-family/advance-health-care-directive-or-living-will/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Republik Österreich . 2019. Gesamte Rechtsvorschrift für Patientenverfügungs-Gesetz. Fassung vom 12.07.2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patientenanwaltschaft Wiener. 2019. Patientenverfügung.https://www.wien.gv.at/gesundheit/einrichtungen/patientenanwaltschaft/vorsorge/patientenverfuegung.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vorarlberg Patientenanwaltschaft. 2019. Patientenverfügung.https://www.patientenanwalt-vbg.at/patientenverfugung/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tirol Patientenvertretung. 2019. Patientenverfügung: eine Kurzinformation der Tiroler Patientenvertretung.https://www.tirol.gv.at/gesundheit-vorsorge/patientenvertretung/patientenverfgung/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patientenvertretung Salzburger. 2019. Die Patientenverfügung.https://www.salzburg.gv.at/themen/gesundheit/patientenvertretung/patientenverfuegung [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kärnten Patientenanwaltschaft. Tätigkeitsbericht. 2019:10–11. https://www.patientenanwalt-kaernten.at/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/2019/Bericht-2018.pdf 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burgenland Patientenanwaltschaft. 2019. Patientenverfügungen: Rechtsbelehrungen und Beurkundungen.https://www.burgenland.at/service/landes-ombudsstelle/gesundheits-patientinnen-patienten-und-behindertenanwaltschaft-burgenland/patientenverfuegungen-rechtsbelehrungen-und-beurkundungen/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brokmann J.C., Grützmann T., Pidun A.K. Vorsorgedokumente in der präklinischen Notfallmedizin. Anaesthesist. 2014;63(1):23–31. doi: 10.1007/s00101-013-2260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2000;1(2) doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koss C.S. Beyond the individual: the interdependence of advance directive completion by older married adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(7):1615–1620. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halpern N.A., Pastores S.M., Chou J.F., Chawla S., Thaler H.T. Advance directives in an oncologic intensive care unit: a contemporary analysis of their frequency, type, and impact. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(4):483–489. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Scoy L.J., Howrylak J., Nguyen A., Chen M., Sherman M. Family structure, experiences with end-of-life decision making, and who asked about advance directives impacts advance directive completion rates. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(10):1099–1106. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLennan V.E.J., Boddy J.H.M., Daly M.G., Chenoweth L.M. Relinquishing or taking control? Community perspectives on barriers and opportunities in advance care planning. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(5):528–532. doi: 10.1071/AH14152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schickedanz A.D., Schillinger D., Landefeld C.S., Knight S.J., Williams B.A., Sudore R.L. A clinical framework for improving the advance care planning process: start with patients’ self-identified barriers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon J., Porterfield P., Bouchal S.R., Heyland D. ‘Not yet’ and ‘Just ask’: barriers and facilitators to advance care planning—a qualitative descriptive study of the perspectives of seriously ill, older patients and their families. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2015;5(1):54. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger B., Heimerl K., Likar R., Hoppe M. Sorgenetzwerke am Lebensende: interviews über das ,gute Sterben‘ im österreichischen Bundesland Kärnten (Care Networks at the End of Life: interviews about ‘Good Dyingʼ in the Austrian Province Carinthia) Palliativmedizin. 2019;20:133–140. doi: 10.1055/a-0886-9427. 03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]