Abstract

Specific organochlorines (OCs) have been associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) with varying degrees of evidence. These associations have not been evaluated in Asia, where the high exposure and historical environmental contamination of certain OC pesticides (e.g. dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH)) are different from Western populations. We evaluated NHL risk and pre-diagnostic blood levels of OC pesticides/metabolites and polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) congeners in a case-control study of 167 NHL cases and 167 controls nested within three prospective cohorts in Shanghai and Singapore. Conditional logistic regression was used to analyze lipid-adjusted OC levels and NHL risk. Median levels of p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p,p’-DDE), the primary DDT metabolite, and β-HCH were up to 12 and 65 times higher, respectively, in samples from the Asian cohorts compared to several cohorts in the United States and Norway. An increased risk of NHL was observed among those with higher β-HCH levels both overall (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR=1.8, 95%CI=1.0-3.2; ptrend =0.049) and after excluding cases diagnosed within two years of blood collection (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR = 2.0, 95%CI =1.1-3.9; ptrend = 0.03), and the association was highly consistent across the three cohorts. No significant associations were observed for other OCs, including p,p’-DDE. Our findings provide support for an association between β-HCH blood levels and NHL risk. This is a concern because substantial quantities of persistent, toxic residues of HCH are present in the environment worldwide. Although there is some evidence that DDT is associated with NHL, our findings for p,p’-DDE do not support an association.

Keywords: organochlorines, DDT, hexachlorocyclohexane, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Chinese cohort

Introduction

Organochlorines (OCs) are a structurally diverse group of chlorinated hydrocarbons and environmentally persistent organic pollutants that have been extensively used as pesticides in agricultural settings, and for industrial applications worldwide.1 Environmental contamination resulting from OC use can be long lasting. For example, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), which was banned in the United States (U.S.) in 1972 but continues to be used in several countries for vector control, has a half-life of up to ~30 years in the environment and has been detected at hundreds of hazardous waste sites in the U.S.2, 3 About ten million tonnes (t) of the pesticide technical hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) are estimated to have been used worldwide from 1948-1997.4 Further, up to seven million t of persistent and toxic residues of HCH were discharged into the environment from lindane production alone, including ~65,000 t in the U.S., resulting in substantial environmental contamination worldwide.4, 5 In addition to the stable β-isomer (5-12%), technical grade HCH also contains other isomers (60-70% α, 6-10% δ, >10% γ, 3-4% ε) whereas pure lindane contains >99% γ-HCH.6 β-HCH, as well as certain DDT metabolites and multiple other OCs, have half-lives measured in years and continue to be detectable in the blood of the U.S. population even though these compounds have been banned in the U.S. and in many other countries for several decades.7

Working groups of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) have classified the OC pesticides lindane and pentachlorophenol as known (Group 1) carcinogens that are causally associated with NHL.8, 9 IARC working groups have also concluded that there is limited evidence (Group 2A) in humans for the carcinogenicity of DDT and noted that “positive associations have been observed between DDT and cancers of the liver, testis, and NHL.”9 Positive associations with NHL have also been observed for polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs).10 Other OC pesticides including hexachlorobenzene (HCB), chlordane, and technical HCH have been classified as possible carcinogens by IARC (Group 2B).11, 12 One methodologic challenge in evaluating the associations between OC pesticides and NHL risk has been the concomitantly relatively high levels of PCB blood levels in Western populations. For example, prospective studies conducted in the U.S. have reported positive associations with NHL risk for higher levels of DDT or its metabolites, particularly p,p’-DDE, but these effects were attenuated after co-adjustment for PCB levels.13

To advance our understanding of the relationship between OC pesticide exposures and NHL risk, epidemiologic studies that include populations with notably high levels of exposure and/or unique exposure patterns may be particularly informative. In Asia, levels of certain OC pesticides have been reported to be higher than in Western countries.14 China was reported to account for an estimated 20% and 33% of global DDT and HCH production, respectively, until 1983 when both were banned, and China contributed to an estimated 10-50% of the global usage of technical HCH.4, 15 In a previous cross-sectional analysis of Chinese women in Shanghai who provided blood samples between 1996 and 1998, lipid-adjusted levels of p,p’-DDE were 8 to 1,800 times higher compared to study populations in Western countries.16 Higher serum levels of β-HCH were also reported among these Chinese women, whereas PCB levels were markedly lower than those measured in Western populations. These patterns in Asia, particularly China, provide a special opportunity to gain further clarity on associations between OC pesticides and NHL risk, especially for DDT and HCH isomers.

We conducted the first epidemiological assessment of OC levels in plasma/serum and NHL risk in Asia using data from a case-control study of 167 NHL cases and 167 individually matched controls nested in three prospective cohorts of Chinese men and women from Shanghai and Singapore. All participants had a pre-diagnostic blood sample collected between 1986 and 2004, with a median of seven years between blood collection and NHL diagnosis. We investigated associations with NHL risk for blood levels of OC pesticides/metabolites as well as for selected PCB congeners.

Methods

Study Population

The study populations and design of this pooled nested case-control study of three cohort populations in Shanghai and Singapore have been described.17 Briefly, cases of NHL and individually matched controls were identified from three prospective cohorts of Chinese individuals. These include the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS),18 the Shanghai Cohort Study (SCS),19 and the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS).20 The SWHS is a prospective cohort of 74,942 women between the ages of 40 and 70 at baseline who were enrolled between 1996 and 2000 in urban Shanghai. Biological samples were collected during the baseline interview. The SCS includes 18,244 men between 45 and 64 years old at enrollment who were recruited between 1986 and 1989 in Shanghai and provided biological samples during the baseline interview. The SCHS is a prospective cohort that includes 63,257 Chinese men and women who were aged 45-74 years at the time of enrollment in 1993-1998. A structured questionnaire was administered through in-person interviews at recruitment. Biologic specimens were collected from SCHS cohort participants who consented to donate biospecimens following the completion of the first follow-up interview during 2000-2004. All studies were approved by the appropriate Institutional Review Boards. It was determined at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that the agency was not engaged in human subjects’ research.

As originally described,17-20 case ascertainment for the cohorts was conducted primarily through annual linkage to the Shanghai Cancer Registry for the SWHS and SCS, and to the Singapore Cancer Registry for the SCHS. For the current study, a total of 167 incident NHL cases (ICD-9 codes 200, 202, and 204 for the SWHS and SCS, and ICD-O-2 codes 9590-9595, 9670-9677, 9680-9688, 9690-9698, 9700-9717, and 9820-9828 for the SCHS) across all three cohorts that had an adequate volume of plasma or serum for the OC analyses were included and were individually matched in a 1:1 ratio to controls from the same cohort population. Cases were diagnosed through 2010 for the SWHS, 2011 for the SCS, and 2008 for the SCHS. The number of matched pairs was 50 in the SWHS, 71 in the SCS, and 46 in the SCHS. Controls were alive and free of cancer at the time of the NHL diagnosis of each index case. For the SWHS, the matching criteria included age at baseline interview (± 5 years) and date of blood collection (± 6 months). For the SCS, the matching criteria were age at baseline interview (± 2 years), date of blood collection (± 1 month), and neighborhood of residence at the time of recruitment. For the SCHS, the matching criteria included age at baseline interview (± 3 years), date of baseline interview (± 2 years), date of biospecimen collection (± 6 months), sex, and dialect group (Cantonese, Hokkien).

Laboratory Methods

Concentrations of OC pesticides/metabolites and PCB congeners were measured in plasma or serum samples (minimum volume 0.5 mL) at the U.S. CDC, National Center for Environmental Health, using methods previously described.21 The measured OC pesticides/metabolites included HCB, β-HCH, oxychlordane, trans-nonachlor, and the main metabolite of DDT, p,p’-DDE. While γ-HCH was not included in the standard panel measured by the U.S. CDC, concentrations of this isomer were measured separately in 50 samples from the SWHS to provide data on detectability and plasma levels. The measured PCB congeners included (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) congeners) 28, 66, 74, 99, 105, 114, 118, 138/158 (co-elution and measured as summed concentration), 146, 153, 156, 157, 167, 170, 178, 180, 183, 187, 189, 194, 196-203, 199, 206, and 209. Given the low concentrations and limited variability of most measured PCB congeners, NHL risk analyses were limited to four representative congeners with the highest concentrations in the study population, and that have previously been associated with NHL in some prospective studies in Western populations (congeners 118, 138/158, 153, 180).13

Briefly, samples were automatically fortified with internal standards using a Gilson 215 liquid handler (Gilson Inc; Middleton, WI) and were extracted by automated liquid liquid extraction (LLE) using the liquid handler. Removal of co-extracted lipids was performed on a silica/sulfuric acid column using the Rapid Trace (Biotage; Uppsala, Sweden) equipment for automation. Final analytical determination of the target analytes was performed by gas chromatography isotope dilution high resolution mass spectrometry (GC-IDHRMS) employing a DFS (Thermo DFS, Bremen, Germany) instrument. Total triglycerides and cholesterol were also measured in each sample using commercially available kits and a Hitachi 912 Chemistry Analyzer (Hitachi; Tokyo, Japan). These measurements were used to calculate total lipid concentrations (mg/dL serum or plasma) using methods described by Phillips et al.22 Background-adjusted OC concentrations were lipid-adjusted and are reported in units of ng/g lipid weight.

Case-control pairs were analyzed sequentially within a laboratory batch and laboratory personnel were blinded to the case-control status of the samples. The median coefficient of variation (CV) for the OCs included in the risk analyses based on 32 blind QC replicates interspersed across batches was 8% for the pesticides (range: 5% for β-HCH to 17% for oxychlordane) and 6% for the PCBs (range: 4% for congeners 118, 153, and 180 to 11% for 138-153). The corresponding median intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were 0.74 for the pesticides (range: 0.20 for oxychlordane to 0.98 for HCB, β-HCH, and p,p’-DDE) and 0.98 for the PCBs (range: 0.94 for congener 138/158 to 0.99 for congeners 118, 153, and 180). A fraction of samples did not pass internal laboratory QC evaluations for specific OCs and the concentrations for these were determined to be non-reportable (ranging from 0.6-14% across OCs; Table 2). Data from these samples were treated as missing in analyses of the corresponding analyte. A very small percentage of the samples (≤1%) had OC pesticide levels below the limit of detection (LOD) (Table 2). These measurements were substituted with a value of one-half the LOD for the specific OC for purposes of reporting concentrations and generating tertile cutpoints for the statistical analyses, and were included in the referent group in all models.

Table 2.

Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and selected PCBs in a nested case-control study of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in three Asian cohorts

| NHL Cases (n=167) | Controls (n=167) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pesticide | ICC/CV(%) | n(%) Below limit of detection1 | n(%) Not reportable |

Median ng/g lipid (25th%, 75th%) |

n(%) Below limit of detection1 | n(%) Not reportable |

Median ng/g lipid (25th%, 75th%) |

| p,p’-DDE | 0.98/6.1 | 0 | 0 | 8,570 (2,970, 12,000) | 0 | 0 | 8,070 (2,850, 10,900) |

| β-HCH | 0.98/5.3 | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 5,670 (672, 9,130) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 5,480 (649, 8,580) |

| Hexachlorobenzene | 0.97/5.7 | 0 | 23 (14) | 57.3 (39.1, 78.1) | 0 | 23 (14) | 56.4 (37.0, 77.5) |

| Oxychlordane | 0.20/16.6 | 0 | 12 (7) | 10.0 (6.4, 12.4) | 2 (1) | 11 (7) | 9.6 (6.0, 12.1) |

| Trans-nonachlor | 0.54/7.5 | 0 | 11 (7) | 13.8 (8.7, 15.5) | 1 (0.6) | 11 (7) | 13.3 (8.2, 15.3) |

| PCB Congeners | |||||||

| 118 | 0.99/4.4 | 0 | 21 (13) | 13.6 (7.3, 17.7) | 0 | 21 (13) | 13.8 (7.9, 17.0) |

| 138/158 | 0.94/11.2 | 0 | 11 (7) | 24.2 (14.7, 28.4) | 0 | 11 (7) | 24.2 (15.4, 30.1) |

| 153 | 0.99/3.7 | 0 | 11 (7) | 33.3 (23.2, 39.1) | 0 | 11 (7) | 33.5 (21.7, 40.4) |

| 180 | 0.99/4.3 | 0 | 22 (13) | 15.1 (9.0, 17.0) | 0 | 21 (13) | 15.5 (7.9, 17.4) |

Limits of detection (LOD) were sample dependent. LOD ranges for each OC compound are as follows (all values expressed in ng/g lipid): p,p’-DDE: 3.3–150; β-HCH: 2.5–120; oxychlordane: 0.9–7.4; HCB: 0.9–7.4; trans-nonachlor: 0.9–7.4; PCB-118: 0.2–1.3; PCB 138/158: 0.2–2.2; PCB-153: 0.2–1.4; PCB-180: 0.3–2.6.

Statistical Analysis

Conditional logistic regression models stratified on matched pairs, and therefore, adjusting for the matching factors were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for NHL risk in relation to lipid-adjusted OC levels categorized into tertiles. Regression analyses were initially conducted within each cohort separately using study-specific tertile cutpoints, based on distributions among all controls with non-missing data for each OC. The data were then pooled across all three cohorts while maintaining the study-specific tertile cutpoints, given the concentration differences across studies. Analyses were also conducted by pooling just the two Shanghai cohorts, using tertiles based on both study-specific as well as combined study cutpoints. Tests for trend were conducted by modeling OC levels as an ordinal variable corresponding to the categorized tertile levels. Given the strong secular trends in OC levels and differences in pesticide usage within this region, and the varied time periods of blood collection across cohorts in our study, which resulted in substantial interstudy OC concentration differences for some compounds, categorical rather than continuous analyses were conducted. These categorical “rankings” of concentration levels are likely to better classify subjects with regard to their historical and cumulative levels relative to other members of the same cohort and also to provide insight into associations that may not be monotonic. Heterogeneity in the associations across cohorts was evaluated by adding interaction terms between the categorical OC tertile variables and dummy variables for study in the regression models.

Additional secondary analyses were conducted. To account for potential influences of disease bias, cases diagnosed within two years after blood collection were excluded from the analysis. Pooled analyses using the same OC tertile cutpoints as the main analyses were also conducted in relation to time between blood collection and diagnosis (<7 years, >7 years) to provide insight into the temporal patterns of the associations. We also conducted analyses excluding cases of lymphoid leukemia (ICD-9: 204, ICD-O-2: 9823) to provide broad insight into subtype-specific associations (i.e. chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is an indolent disease with a prolonged clinical course and may have a distinct etiology, compared to other solid NHL tumors) and for comparability with studies using older NHL classifications that did not include lymphoid leukemia in the case definition. Most NHL cases were classified based on ICD-9 codes in these cohorts (78%) and this precluded more detailed analyses by NHL subtype. Finally, the potential for effect modification by age and sex was explored by fitting models in men and women separately and in two age strata defined by the median age in the pooled study population (≤58 years old, >58 years old). Heterogeneity across these strata was assessed by including the categorical OC tertile variables and dummy variables for sex or age in the models. Statistical Analysis Software (SAS v. 9.4, Cary, NC) was used to conduct these analyses.

Results

Study Population and Exposure Characteristics

The majority of the subjects included in the pooled analysis were male (62%) and the mean age at baseline was very similar across the three cohorts (mean (SD) = 57 (8) years) (Table 1). The NHL cases were diagnosed on average 7.6 years after blood collection, with a cohort-specific range of 3-14 years on average.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases and controls from a pooled nested case-control study of subjects from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS), Shanghai Cohort Study (SCS), and the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS)

| Overall | SWHS | SCS | SCHS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | NHL Cases (n = 167) |

Controls (n=167) |

NHL Cases (n= 50) |

Controls (n= 50) |

NHL Cases (n=71) |

Controls (n=71) |

NHL Cases (n= 46) |

Controls (n= 46) |

| Gender, n(%) | ||||||||

| Male | 103 (62) | 103 (62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 71 (100) | 71 (100) | 32 (70) | 32 (70) |

| Female | 64 (38) | 64 (38) | 50 (100) | 50 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (30) | 14 (30) |

| Mean age (years) at baseline, SD | 57 (7) | 57 (8) | 58 (8) | 58 (8) | 56 (6) | 56 (6) | 58 (8) | 58 (8) |

| Median years between blood collection and NHL diagnosis (min, max) | 7.6 (0.3–24) | 8 (0.5, 13) | 14 (0.3, 24) | 3 (0.4, 7) | ||||

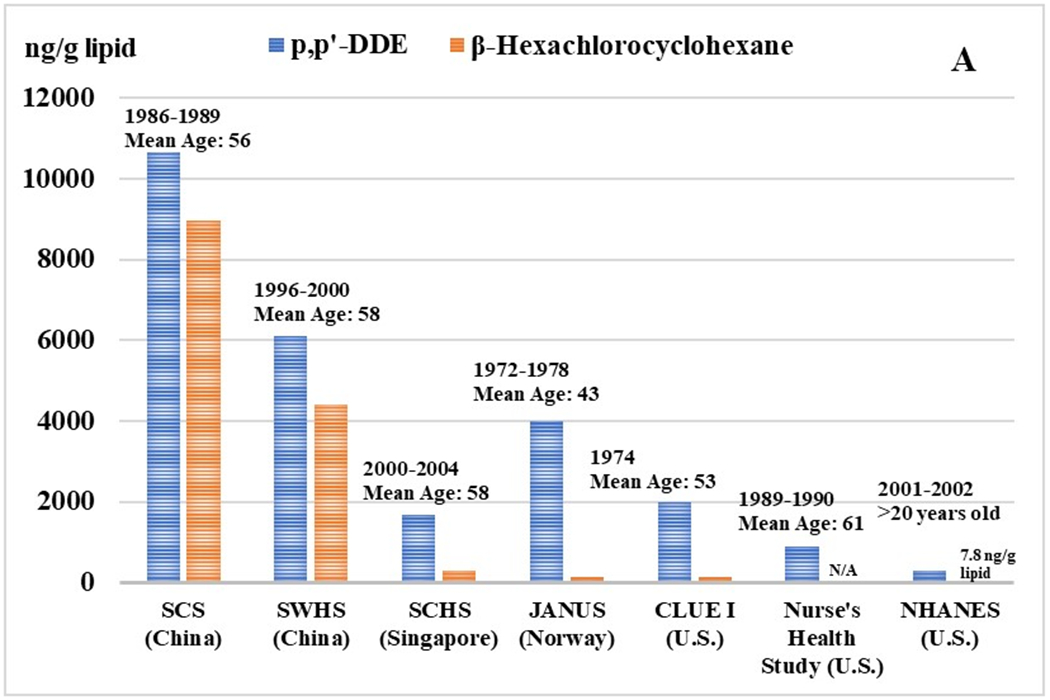

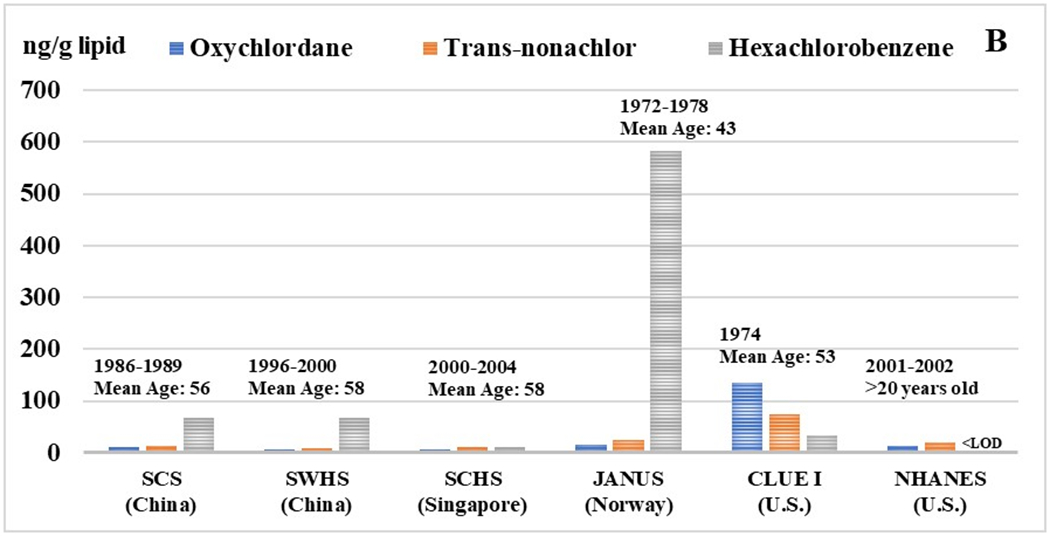

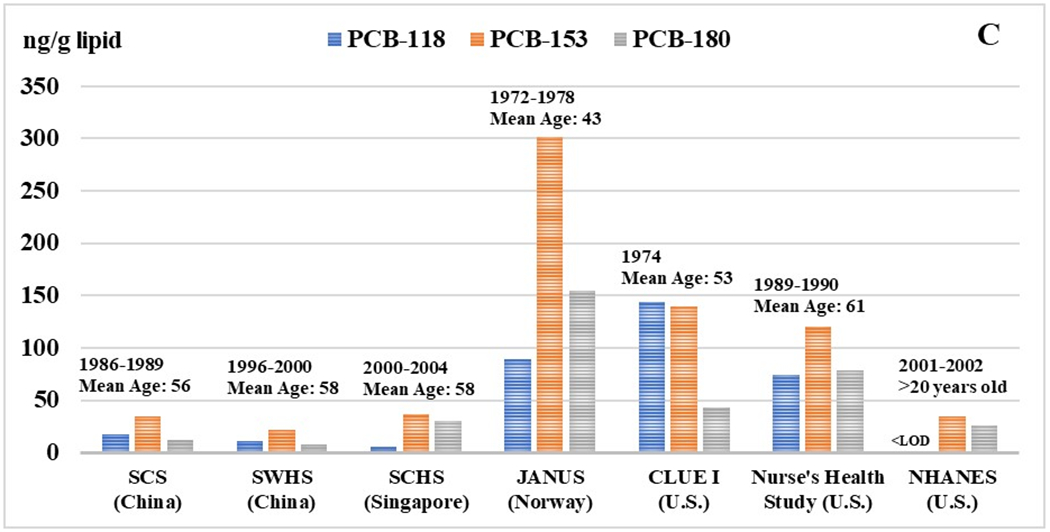

Of the OCs pesticides, p,p’-DDE had the highest concentration among both NHL cases (mean: 8,570 ng/g lipid) and controls (mean: 8,070 ng/g lipid), followed by β-HCH (mean: 5,670 and 5,480 ng/g lipid in cases and controls, respectively) in the pooled study population (Table 2). Concentrations of β-HCH and p,p’-DDE showed large variation across individual cohorts, with considerably higher levels observed in Shanghai than in Singapore (Supplemental Table 1). Whereas the variation in the two Shanghai cohorts may reflect differences in the timing of blood collection, the substantially higher levels in Shanghai relative to Singapore likely reflect differences in external exposure as the SWHS enrolled subjects relatively contemporaneous to those in the Singapore cohort. Median concentrations of p,p’-DDE were up to ~12 times higher (range 2.6-12.1 times higher in SCS; 1.5-7.0 times higher in SWHS) and levels of β-HCH were up to ~65 times higher (range 60.5-64.8 times higher in SCS; 29.8-32.0 times higher in SWHS) in Shanghai compared to those in Western cohorts conducted in the U.S. (CLUE I and/or Nurse’s Health Study) and Norway (Janus), whereas concentrations of these two OCs in Singapore were more comparable to those in the Western cohorts (Figure 1). Notably, these dramatically higher levels were observed in the Shanghai cohorts in blood collected either around the same time or up to almost three decades after that of the comparison Western cohorts, two of which (Janus, CLUE I) also had OCs measured at the U.S. CDC, the same laboratory used in the current study.

Figure 1. Selected organochlorine pesticide and PCB congener concentrations in Asian and Western populations.

Median concentrations of OCs (ng/g lipid) are presented for each population along with the range of blood collection years and mean age of the participants. For the Asian cohort populations, the following abbreviations are used: Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS), Shanghai Cohort Study (SCS), and the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS).

As expected, concentrations of PCBs were substantially lower in all three Asian cohorts relative to the CLUE I, Nurse’s Health Study, and Janus cohorts (Figure 1). Spearman correlations between OC pesticides and PCBs were generally moderate but varied across individual compounds (Supplemental Table 2A and 2B).

Associations between OCs and NHL Risk

The highest tertile concentrations of β-HCH in the pooled analysis were associated with overall NHL (3rd vs. 1st tertile: OR=1.8, 95% CI=1.0-3.2; ptrend = 0.049), as well as for NHL excluding cases of lymphoid leukemia (3rd vs. 1st tertile: OR=1.9, 95% CI = 1.0-3.5; ptrend = 0.04; Table 3; Supplemental Table 3). The β-HCH association was consistent across the three cohorts with no evidence of heterogeneity (pheterogeneity = 0.88; Table 3) and was also consistent in analyses restricted to the two Shanghai cohorts (3rd vs. 1st tertile for combined cutpoint: OR=2.2, 95% CI 0.9-5.8; OR=1.7, 95% CI=0.8-3.6 for study-specific cutpoints). The association between β-HCH levels and overall NHL was consistent or became slightly stronger when further adjusted for other OCs, including PCB congeners (data not shown). In analyses that considered time between blood collection and diagnosis, the β-HCH association was consistent among cases that were diagnosed <7 and >7 years after blood collection and was somewhat stronger when excluding cases diagnosed within two years of blood collection (3rd vs. 1st tertile for overall NHL: OR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.1-3.9; ptrend = 0.03; Table 4; Supplemental Table 4). The β-HCH association was also very similar in men and women, but evidence of effect modification by age was suggested although the p-interaction was not statistically significant (p=0.31; Supplemental Table 5). Specifically, a significant exposure-response relationship for overall NHL risk was observed among those >58 years old (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR = 3.0, 95% CI=1.2-7.5; ptrend = 0.01) but not among those ≤58 years old (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR = 1.0, 95% CI=0.5-2.4; ptrend = 0.92; Supplemental Table 5).

Table 3.

Associations between organochlorine pesticides and non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk in a nested case-control study of three Asian cohorts

| SWHS | SWHS | SCS | SCS | SCHS | SCHS | Pooled2 | Pooled | Pooled2,3 | Pooled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co/Ca1 | OR (95% CI) | Co/Ca | OR (95% CI) | Co/Ca | OR (95% CI) | Co/Ca All NHL |

OR (95% CI) All NHL |

Co/Ca Excludes ICD 204 |

OR (95% CI) Excludes ICD 204 |

|

| p,p’-DDE4 | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 17/18 | 1.0 (ref) | 24/17 | 1.0 (ref) | 16/20 | 1.0 (ref) | 57/55 | 1.0 (ref) | 49/46 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 17/16 | 0.9 (0.3–2.4) | 24/34 | 1.9 (0.9–4.3) | 15/7 | 0.4 (0.1–1.2) | 56/57 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 48/48 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) |

| Tertile 3 | 16/16 | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 23/20 | 1.3 (0.5–3.1) | 15/19 | 1.1 (0.4–2.9) | 54/55 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 50/53 | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

| p-trend | 0.89 | 0.66 | 0.99 | 0.83 | 0.66 | |||||

| p-heterogeneity5 | 0.20 | |||||||||

| β-HCH | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 17/17 | 1.0 (ref) | 24/19 | 1.0 (ref) | 16/12 | 1.0 (ref) | 57/48 | 1.0 (ref) | 48/40 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 17/10 | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 23/21 | 1.3 (0.5–3.3) | 15/15 | 1.2 (0.5–3.3) | 55/46 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 50/39 | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) |

| Tertile 3 | 15/22 | 1.7 (0.5–5.8) | 23/30 | 1.8 (0.7–4.6) | 15/19 | 1.8 (0.6–5.3) | 53/71 | 1.8 (1.0–3.2) | 48/67 | 1.9 (1.0–3.5) |

| p-trend | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.049 | 0.04 | |||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.88 | |||||||||

| Hexachlorobenzene | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 17/16 | 1.0 (ref) | 20/16 | 1.0 (ref) | 12/15 | 1.0 (ref) | 49/47 | 1.0 (ref) | 43/41 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 16/19 | 1.2 (0.5–3.2) | 21/18 | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 12/14 | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 49/51 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 46/46 | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) |

| Tertile 3 | 16/14 | 0.9 (0.4–2.6) | 18/25 | 2.0 (0.7–5.3) | 11/6 | 0.3 (0.1–1.4) | 45/45 | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) | 38/40 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) |

| p-trend | 0.90 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.74 | |||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.30 | |||||||||

| Oxychlordane | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 17/12 | 1.0 (ref) | 24/22 | 1.0 (ref) | 11/12 | 1.0 (ref) | 52/46 | 1.0 (ref) | 45/40 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 17/23 | 1.9 (0.7–5.0) | 24/25 | 1.1 (0.5–2.6) | 12/10 | 0.7 (0.2–2.5) | 53/58 | 1.2 (0.7–2.1) | 49/50 | 1.1 (0.6–2.0) |

| Tertile 3 | 16/15 | 1.3 (0.5–3.4) | 23/24 | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) | 11/12 | 1.1 (0.3–4.5) | 50/51 | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | 43/46 | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

| p-trend | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.59 | 0.56 | |||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.81 | |||||||||

| Trans-nonachlor | ||||||||||

| Tertile 1 | 17/13 | 1.0 (ref) | 24/11 | 1.0 (ref) | 12/14 | 1.0 (ref) | 53/38 | 1.0 (ref) | 45/34 | 1.0 (ref) |

| Tertile 2 | 17/20 | 1.4 (0.6–3.5) | 24/38 | 3.0 (1.3–7.3) | 12/10 | 0.7 (0.3–2.2) | 53/68 | 1.7 (1.0–2.8) | 46/58 | 1.6 (0.9–2.7) |

| Tertile 3 | 16/17 | 1.3 (0.5–3.0) | 23/22 | 2.3 (0.8–6.6) | 11/11 | 0.8 (0.2–2.9) | 50/50 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 46/45 | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) |

| p-trend | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.75 | 0.27 | 0.44 | |||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.40 |

Study includes a maximum of 167 NHL cases and 167 controls across all three cohorts. Subjects with non-reportable data and their corresponding matched case/control for specific OCs (see Table 2) are not included in case/control counts.

Pooled results based on cohort-specific cutpoints based on distributions in all cohort-specific controls, calculated before combining data from the three studies (Shanghai Women’s Health Study (SWHS), Shanghai Cohort Study (SCS), and the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS)).

Removes cases of lymphoid leukemia and their matched controls from the analysis.

Tertile cutpoints (1st, 3rd) for each OC pesticide in individual cohorts were as follows (ng/g lipid): p,p’-DDE (SWHS: 5,114, 7,760; SCHS: 1,447, 2,039; SCS: 9,249, 15,910), HCB (SWHS: 61.5, 79.4; SCHS: 8.5, 14.2; SCS: 57.9, 74.5), β-HCH (SWHS: 3,648.0, 5,242.0; SCHS: 219.2, 401.9; SCS: 7,753.0, 10,530.0), oxychlordane (SWHS: 5.4, 8.2; SCHS: 5.8, 7.2; SCS: 10.6, 13.4), trans-nonachlor (SWHS: 7.0, 10.5; SCHS: 9.8, 13.4; SCS: 10.9, 16.2).

P-heterogeneity for tertile results across cohorts.

Table 4.

Associations between organochlorine pesticides and non-Hodgkin lymphoma risk in a nested case-control study of three Asian cohorts, stratified by time between blood collection and diagnosis

| Pooled1 | Pooled | Pooled | Pooled | p-het2 (time period) | Pooled | Pooled | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co/Ca | OR (95% CI) | Co/Ca | OR (95% CI) | Co/Ca | OR (95% CI) | ||

| <7 years | <7 years | >7 years | >7 years | Excluding first 2yrs follow-up | |||

| p,p’-DDE | |||||||

| Tertile 1 | 25/29 | 1.0 (ref) | 32/26 | 1.0 (ref) | 49/47 | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Tertile 2 | 25/19 | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 31/38 | 1.5 (0.7–3.2) | 48/53 | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) | |

| Tertile 3 | 27/29 | 0.9 (0.4–2.1) | 27/26 | 1.3 (0.6–2.7) | 49/46 | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | |

| p-trend | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.94 | ||||

| p-heterogeneity2 | 0.30 | ||||||

| β-HCH | |||||||

| Tertile 1 | 25/21 | 1.0 (ref) | 32/27 | 1.0 (ref) | 51/39 | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Tertile 2 | 26/21 | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) | 29/25 | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 46/42 | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | |

| Tertile 3 | 26/35 | 1.9 (0.8–4.5) | 27/36 | 1.7 (0.8–4.0) | 47/63 | 2.0 (1.1–3.9) | |

| p-trend | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.03 | ||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.89 | ||||||

| Hexachlorobenzene | |||||||

| Tertile 1 | 19/25 | 1.0 (ref) | 30/22 | 1.0 (ref) | 46/42 | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Tertile 2 | 20/25 | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 29/26 | 1.3 (0.6–2.6) | 45/44 | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | |

| Tertile 3 | 25/14 | 0.2 (0.1–0.8) | 20/31 | 2.2 (1.0–5.0) | 37/42 | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) | |

| p-trend | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.46 | ||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.01 | ||||||

| Oxychlordane | |||||||

| Tertile 1 | 18/20 | 1.0 (ref) | 34/26 | 1.0 (ref) | 48/39 | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Tertile 2 | 26/23 | 0.8 (0.3–1.9) | 27/35 | 1.7 (0.8–3.3) | 47/57 | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) | |

| Tertile 3 | 21/22 | 1.0 (0.4–2.6) | 29/29 | 1.3 (0.6–2.9) | 45/43 | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | |

| p-trend | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.63 | ||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.42 | ||||||

| Trans-nonachlor | |||||||

| Tertile 1 | 22/19 | 1.0 (ref) | 31/19 | 1.0 (ref) | 48/32 | 1.0 (ref) | |

| Tertile 2 | 24/23 | 1.1 (0.5–2.5) | 29/45 | 2.1 (1.1–4.3) | 45/65 | 2.0 (1.1–3.4) | |

| Tertile 3 | 20/24 | 1.4 (0.6–3.4) | 30/26 | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | 47/43 | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | |

| p-trend | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.36 | ||||

| p-heterogeneity | 0.96 | 0.33 |

Pooled results based on cohort-specific tertiles calculated before combining data. Cutpoints are the same as those used for the primary analyses in Table 3.

P-heterogeneity for tertile results for <7 vs. >7 years between blood collection and diagnosis in the pooled analysis.

Of 50 samples from the SWHS that were measured for γ-HCH, serum levels of 46 (92%) were below the LOD. Three samples had detectable levels of both γ-HCH and β-HCH, and in these samples blood levels of β-HCH were 84-725 times higher than levels of γ-HCH.

No significant exposure-response associations were observed between other OC pesticide levels and NHL risk (Table 3). Higher concentrations of trans-nonachlor were associated with NHL risk in the SCS cohort, but the exposure response relationship was not monotonic (Tertile 2 OR = 3.0, 95% CI = 1.3-7.3; Tertile 3 OR = 2.3, 95% CI = 0.8-6.6; ptrend = 0.13) and there was no evidence for an association in the other two cohorts (Table 3). For p,p’-DDE, the pooled OR for overall NHL risk in the highest vs. lowest tertile was 1.1 (95% CI = 0.6-1.8) and no exposure-response relationships were observed across individual cohorts (Table 3). Similarly, there were no significant exposure-response associations with p,p’-DDE for NHL risk excluding lymphoid leukemia or in analyses based on time between blood collection and diagnosis. Concentrations of HCB were not associated with overall NHL risk or risk of NHL excluding lymphoid leukemia (Table 3). However, there was evidence of heterogeneity in the risk based on time between blood collection and diagnosis whereby higher HCB levels were associated with NHL among cases diagnosed >7 years after blood collection (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR = 2.2, 95% CI=1.0-5.0; ptrend = 0.06), but not among cases diagnosed <7 years after blood collection (3rd vs. 1st tertile OR=0.2, 95% CI=0.1-0.8; ptrend = 0.04; Table 4).

Concentrations of PCB congeners 118, 138/158, 153, and 180 were not significantly associated with risk of overall NHL or NHL excluding cases of lymphoid leukemia (Supplemental Tables 3 and 6).

Meta-analysis of β-HCH levels and NHL risk

We conducted a meta-analysis of our β-HCH results with data from one previously published prospective cohort study conducted in the United States 23 and with unpublished data from the prospective Janus Serum Bank Cohort, which was conducted in Norway (Dazhe Chen and Lawrence S. Engel, unpublished). The overall study of NHL within this cohort has been described previously.13 The summary OR from a meta-analysis of higher vs. lower levels was 1.6 (95% CI= 1.0-2.5; Supplemental Table 7). We then included these data as well as data from three case-control studies conducted in Western populations24-26 that published data on categorized β-HCH levels and NHL risk in the meta-analysis, and the overall summary OR for higher vs. lower levels was 1.4 (95% CI: 1.1-1.8; Supplemental Table 7). Samples from all of the prospective cohort studies and from one of the case-control studies25 were analyzed for OCs at the U.S. CDC.

Discussion

This is the first study to our knowledge that has evaluated associations between blood levels of OCs and risk of NHL in Asia. The blood concentrations of p,p’-DDE and β-HCH were markedly higher in the Shanghai cohorts than in several Western cohorts, despite blood collection periods up to almost three decades later in Shanghai (1986-2000) than in the U.S. and Norwegian cohorts (1972-1990) included for comparison. Our findings provide the first evidence suggesting associations between blood levels of β-HCH and NHL risk in a population in Asia. Although there is some limited evidence that DDT (IARC Group 2A) is associated with NHL risk based on studies in Western populations, our findings among Asians do not support an association with levels of p,p’-DDE.

China was the largest producer and user of technical HCH as a general insecticide until its ban in 1983, and our data are consistent with reports of extremely high levels of historical technical HCH contamination in China.4 Lindane (predominantly the γ-HCH isomer) was reported to be used in China beginning only in 1991, after blood samples were collected in the SCS, and its usage (~3,200 t between 1991-2000) was far lower than that of technical HCH (>100,000 t in 1980).27, 28 In contrast to the high persistence of β-HCH, which has a half-life of ~7 years in the body and accounts for roughly 5-12% of technical HCH, the α-HCH, δ-HCH, and γ-HCH isomers are more rapidly excreted in the urine.29 The low detectability of γ-HCH in plasma of subjects from the SWHS suggested that at the time of blood draw, the vast majority of subjects from this study did not have current exposure to this isomer. Given these historical usage and production patterns of HCH in China, the β-HCH levels measured in our Chinese population likely originate predominantly from technical HCH (IARC Group 2B) use rather than from lindane (IARC Group 1 carcinogen associated with NHL). Our data therefore provide evidence that environmental exposure to technical HCH may be associated with risk of NHL.

We observed an increased risk of NHL in relation to the highest vs. lowest β-HCH levels among studies in our meta-analysis. This included data from three prospective cohorts in Asia and two prospective cohorts and three case-control studies conducted in Western countries. β-HCH levels in previous Western studies have been considered to some extent to be a proxy for exposure to lindane,6 or possibly its manufacturing process, but these levels may also reflect earlier use of technical HCH, which was largely replaced by lindane in the West.5 Although β-HCH levels across studies likely reflect diverse exposure scenarios and can be proxies for different mixtures of isomers depending on the specific HCH formulations used and the temporal patterns of that usage, the magnitude of associations for blood β-HCH levels and NHL risk in prospective studies in Asia and in our meta-analysis of cohorts was highly consistent. This suggests that environmental exposure to HCH isomer mixtures may be associated with NHL even if β-HCH levels have reflected exposure to different mixtures of HCH isomers over time. This has potentially important public health implications for the carcinogenic potential of the substantial environmental contamination from HCH waste isomers worldwide.5

Our findings also raise a question about the carcinogenicity of the β-HCH isomer itself. As a consequence of the switch from technical HCH to lindane (99% pure γ-HCH), there appears to be more extensive toxicological data available for the γ-HCH rather than the β-HCH isomer.6 However, there is some evidence suggesting that β-HCH might be a lymphomagen rather than being only a proxy for lindane. An IARC working group updated review of technical HCH in 1987 concluded that there was limited evidence of carcinogenicity in animals for the β-isomer.12 A study of inbred Swiss mice with oral exposure to technical HCH found significant increases in the incidence of lymphoreticular neoplasms.30 In addition, evidence of immune function changes was observed in mice exposed to β-HCH through dietary intake.31 Further, we observed in our study that β-HCH blood levels were significantly and positively correlated with blood levels of soluble CD27 (spearman R = 0.21; p=0.0001), which stimulate B-cell activation,32, 33 and which were associated with increased risk of NHL in another of our reports from the same Asian cohorts.17

Our exploratory analyses stratified by age at baseline in the Asian cohorts also suggested that the β-HCH association was limited to older individuals (>58 years old). The cases >58 years old at baseline (mean: 64 years old) would have had peak blood levels to β-HCH at older ages compared to cases ≤58 years old at baseline (mean: 52 years old), which may also suggest that timing of exposure influences development of lymphoma. Stratified analyses by key demographic variables such as age is warranted in future studies of this association.

Whereas use of DDT was officially banned in the U.S. and Norway in the early 1970s, its use for agricultural activities in China continued until the early 1980s and China continued to produce DDT for export through 2007.34 In Singapore, general population exposure to DDT may have resulted from the importing of contaminated food,35 including from Malaysia, which did not ban DDT until 1999. Risk of NHL in relation to total DDT or individual DDT metabolites has been evaluated in multiple prospective cohorts in Western populations. In several Western studies, DDT associations with NHL have been largely attenuated after further adjusting for PCB levels.13, 36 Studies of occupational DDT use and NHL risk, which have primarily utilized job exposure matrices or questionnaire-based exposure assessments, have reported inconsistent results.6 A significantly elevated risk of NHL was observed for increasing duration of DDT use in the U.S. Agricultural Health Study,37 but no excess of lymphoma mortality was observed in a cohort of 4,552 men who were occupationally exposed to DDT during antimalaria operations in Sardinia.38 Although there is limited evidence that DDT causes NHL based on the IARC classification (Group 2A), our data in Asians do not suggest an association with p,p’-DDE levels that are comparable to or substantially higher than those measured previously in Western cohorts.

Concentrations of other OC pesticides in these Chinese populations were generally comparable or even lower relative to population-based samples in Western countries. Our analyses did not suggest consistent associations or exposure-response relationships for NHL with other OC pesticides. While no association between HCB levels and NHL risk was observed in the overall analyses, we observed significant heterogeneity and opposite directions in the associations based on the timing of blood collection and diagnosis. These differences in the stratified analyses by follow-up time are likely due to chance as there is no known mechanism by which HCB exposure would be protective against NHL risk. If this result was driven by some consequence of undiagnosed NHL, which might be expected among those with shorter periods of time between blood collection and diagnosis, it is likely that we would have observed evidence of a similar pattern for other OC compounds. To the contrary, associations with other OCs were very consistent across follow-up time strata.

Our study has several strengths. Evaluation of OCs and NHL risk in these Asian populations provided several unique advantages with respect to OC exposure characteristics. In addition to the higher p,p’-DDE and β-HCH exposure levels, blood levels of PCB congeners were substantially lower than in previous studies of Western populations as expected based on previously published observations in Shanghai16 and were not independent risk factors for NHL in this population. Therefore, concerns about potential confounding effects for PCBs on associations between OC pesticides and NHL risk were minimized, particularly for p,p’-DDE. Our study also provides a meta-analysis suggesting an association between higher blood levels of β-HCH and NHL risk based on five prospective cohort studies and three case-control studies. All blood samples in our study were collected before NHL diagnosis and were analyzed concurrently by the same laboratory, which was blinded to the case-control status of the samples. This mitigated the potential for disease bias and enabled analyses stratified by follow-up time. Random measurement error was also likely minimal, as evidenced by the high reproducibility of the laboratory data (i.e. ICCs >90% for seven of the nine measured OCs, including for p,p’-DDE and β-HCH (0.98)). The blood concentrations of p,p’-DDE and β-HCH were high in these Asian populations but we also observed adequate variation to analyze exposure-response relationships (i.e. ~ 2-4 fold differences between mean values of the first vs. third tertiles).

Several limitations of our study should also be noted. First, we were unable to comprehensively evaluate NHL subtype-specific associations given the high percentage of cases with only ICD-9 diagnosis codes. However, our exploratory analyses suggested that the NHL association for β-HCH was similar with and without lymphoid leukemia included in the case group. The lymphoid leukemias accounted for a relatively small proportion of the overall NHL case series in this analysis (12%). Therefore, the overall results are driven in large part by the solid tumor NHL subtypes. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common NHL subtype in both Chinese and Western populations, accounting for at least 30% of cases,39, 40 whereas in Asia the proportions of T-cell lymphomas are higher compared to Western countries (e.g. ~13-18% in Shanghai and ~11% in Singapore compared to ~7% in the U.S.).40-42 It is therefore likely that our findings reflect at least in part associations with DLBCL given that this is the predominant expected subtype in our study. Second, samples were collected relatively close (but prior to) NHL diagnosis in the Singapore study, but our analyses, stratified by time between blood collection and diagnosis and also excluding cases diagnosed within the first two years after blood collection, did not suggest meaningful differences in the NHL association with β-HCH levels. Third, correlations between the OCs were generally moderate but exploratory analyses that included co-adjustment for other OCs in the model resulted in similar or slightly stronger associations with NHL for β-HCH. Finally, our study sample was relatively small, despite pooling three cohorts. In Asia, incidence rates of NHL B-cell subtypes historically have been lower than in Western countries.43 This limited our statistical power for detecting heterogeneity in the associations across characteristics such as age and sex. However, evidence suggests that rates of either overall NHL or specific subtypes may be increasing in Shanghai, China,44, Taiwan,45, Japan,41 and Korea.46 Future studies in Asia that accrue additional NHL cases as the follow-up of individual cohorts matures would be useful to replicate and extend our findings, particularly if these more recently diagnosed cases have additional information on NHL subtype.

In conclusion, our study showed a positive association between pre-diagnostic blood levels of β-HCH and NHL risk that was highly consistent across the three Asian cohorts. Further, a meta-analysis of our results with results from two prospective cohorts and three case-control studies in the West provided evidence of an association with NHL as well. This provides support that environmental exposure to HCH may be associated with risk of NHL and adds some evidence that β-HCH may itself be a carcinogen. No significant exposure-response associations were observed for other OCs, including p,p’-DDE despite very high concentrations measured in these Asian populations. Further evaluation of these associations, particularly in understudied Asian populations that have OC exposure characteristics that differ from the West, would be informative to further our understanding of the lymphomagenic potential of these ubiquitous compounds.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Impact.

Organochlorines (OC) are environmentally persistent organic pollutants that have been associated with cancer risk. Here the authors conducted a prospective study of blood OC levels and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in Asia, where high exposures and historical environmental contamination of certain OC pesticides have been reported. They find an association between risk of NHL and higher levels of β-hexachlorocyclohexane, median levels of which were up to 65-times higher in the Asian samples than in samples from several Western populations. These results add to the weight of evidence that environmental exposure to HCH is carcinogenic.

Funding

This nested case-control study of organochlorines was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the CDC, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Shanghai Cohort Study and the Singapore Chinese Health Study were supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health grant numbers R01CA144034 and UM1CA182876. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health research grants R37 CA70867 and UM1 CA173640, and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- DDT

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane

- p,p’-DDE

p,p’-dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene

- HCH

Hexachlorocyclohexane

- HCB

Hexachlorobenzene

- PCB

Polychlorinated biphenyl

- NHL

non-Hodgkin lymphoma

References

- 1.Jayaraj R, Megha P, Sreedev P. Organochlorine pesticides, their toxic effects on living organisms and their fate in the environment. Interdiscip Toxicol 2016;9: 90–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mansouri A, Cregut M, Abbes C, Durand MJ, Landoulsi A, Thouand G. The Environmental Issues of DDT Pollution and Bioremediation: a Multidisciplinary Review. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2017;181: 309–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Public Health Statement for DDT, DDE, and DDD. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/phs/phs.asp?id=79&tid=20. Accessed 10/25/2018.

- 4.Li YF. Global technical hexachlorocyclohexane usage and its contamination consequences in the environment: from 1948 to 1997. Science Total Environ; 232:121–58. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vijgen J, Abhilash PC, Li YF, Lal R, Forter M, Torres J, Singh N, Yunus M, Tian C, Schaffer A, Weber R. Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) as new Stockholm Convention POPs--a global perspective on the management of Lindane and its waste isomers. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2011;18: 152–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs Vol 113: DDT, Lindane, and 2,4-D. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/mono113.pdf. Accessed 1/4/2019.

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals Volume 2. https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Volume2_Mar2018.pdf. Accessed 10/25/2018.

- 8.Guyton KZ, Loomis D, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K, International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of pentachlorophenol and some related compounds. Lancet Oncol 2016;17: 1637–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loomis D, Guyton K, Grosse Y, El Ghissasi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K, International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group ILF. Carcinogenicity of lindane, DDT, and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Lancet Oncol 2015;16: 891–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Baan R, Mattock H, Straif K, WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer. Carcinogenicity of polychlorinated biphenyls and polybrominated biphenyls. Lancet Oncol 2013;14: 287–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs Vol 79: Some Thyrotropic Agents. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/mono79.pdf. Accessed 3/2/2019.

- 12.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Overall Evaluations of Carcinogenicity: An Updating of IARC Monographs Volumes 1 to 42 Supplement 7. https://monographs.iarc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Suppl7.pdf. Accessed 3/2/2019. [PubMed]

- 13.Engel LS, Laden F, Andersen A, Strickland PT, Blair A, Needham LL, Barr DB, Wolff MS, Helzlsouer K, Hunter DJ, Lan Q, Cantor KP, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl levels in peripheral blood and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from three cohorts. Cancer Res 2007;67: 5545–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang JH, Chang YS. 2011. Organochlorine Pesticides in Human Serum PMS, IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/13642. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/pesticides-strategies-for-pesticides-analysis/organochlorine-pesticides-in-human-serum. Accessed 10/25/2018. [DOI]

- 15.Zhang G, Parker A, House A, Mai B, Li X, Kang Y, Wang Z. Sedimentary records of DDT and HCH in the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ Sci Technol 2002;36: 3671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SA, Dai Q, Zheng W, Gao YT, Blair A, Tessari JD, Tian Ji B, Shu XO. Association of serum concentration of organochlorine pesticides with dietary intake and other lifestyle factors among urban Chinese women. Environ Int 2007;33: 157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassig BA, Shu XO, Koh WP, Gao YT, Purdue MP, Butler LM, Adams-Haduch J, Xiang YB, Kemp TJ, Wang R, Pinto LA, Zheng T, et al. Soluble levels of CD27 and CD30 are associated with risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in three Chinese prospective cohorts. Int J Cancer 2015;137: 2688–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng W, Chow WH, Yang G, Jin F, Rothman N, Blair A, Li HL, Wen W, Ji BT, Li Q, Shu XO, Gao YT. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162: 1123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross RK, Yuan JM, Yu MC, Wogan GN, Qian GS, Tu JT, Groopman JD, Gao YT, Henderson BE. Urinary aflatoxin biomarkers and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 1992;339: 943–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan JM, Stram DO, Arakawa K, Lee HP, Yu MC. Dietary cryptoxanthin and reduced risk of lung cancer: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12: 890–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones R, Edenfield E, Anderson S, Zhang Y, Sjodin A. Semi-automated extraction and cleanup method for measuring persistent organic pollutants in human serum. Organohalogen Comp 2012; 74: 97–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips D, Pirkle J, Burse V, Bernet J, Henderson L, Needham L. Chlorinated hydrocarbon levels in human serum: effects of fasting and feeding. Arch Environ Contamin Toxicol 1989;18:495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantor KP, Strickland PT, Brock JW, Bush D, Helzlsouer K, Needham LL, Zahm SH, Comstock GW, Rothman N. Risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and prediagnostic serum organochlorines: beta-hexachlorocyclohexane, chlordane/heptachlor-related compounds, dieldrin, and hexachlorobenzene. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111: 179–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spinelli JJ, Ng CH, Weber JP, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Lai AS, Brooks-Wilson AR, Le ND, Berry BR, Gallagher RP. Organochlorines and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Cancer 2007;121: 2767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Roos AJ, Hartge P, Lubin JH, Colt JS, Davis S, Cerhan JR, Severson RK, Cozen W, Patterson DG Jr., Needham LL, Rothman N. Persistent organochlorine chemicals in plasma and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer Res 2005;65: 11214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cocco P, Brennan P, Ibba A, de Sanjose Llongueras S, Maynadie M, Nieters A, Becker N, Ennas MG, Tocco MG, Boffetta P. Plasma polychlorobiphenyl and organochlorine pesticide level and risk of major lymphoma subtypes. Occup Environ Med 2008;65: 132–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li YF. Global gridded technical hexachlorocyclohexane usage inventories using a global cropland as a surrogate. J Geophysical Res 1999;104: 23785–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YF, Cai DJ, Shan ZJ, Zhu ZL. Gridded usage inventories of technical hexachlorocyclohexane and lindane for China with 1/6 latitude by 1/4 longitude resolution. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2001; 41: 211–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Toxicological Profile: Hexachlorocyclohexane. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp43-c1.pdf; https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp43-c4.pdf. Accessed 10/8/2018.

- 30.Kashyap SK, Nigam SK, Gupta RC, Karnik AB, Chatterjee SK. Carcinogenicity of hexachlorocyclohexane (BHC) in pure inbred swiss mice. J Environ Sci Health B 1979;14: 305–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornacoff JB, Lauer LD, House RV, Tucker AN, Thurmond LM, Vos JG, Working PK, Dean JH. Evaluation of the immunotoxicity of beta-hexachlorocyclohexane (beta-HCH). Fundam Appl Toxicol 1988;11: 293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lens SM, Tesselaar K, van Oers MH, van Lier RA. Control of lymphocyte function through CD27-CD70 interactions. Semin Immunol 1998;10:491–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Croft M Co-stimulatory members of the TNFR family: keys to effective T-cell immunity? Nat Rev Immunol 2003;3:609–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berg H, Manuweera G, Konradsen F. Global trends in the production and use of DDT for control of malaria and other vector-borne diseases. Malar J 2017;16: 401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo XW, Foo SC, Ong HY. Serum DDT and DDE levels in Singapore general population. Sci Total Environ 1997;208: 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothman N, Cantor KP, Blair A, Bush D, Brock JW, Helzlsouer K, Zahm SH, Needham LL, Pearson GR, Hoover RN, Comstock GW, Strickland PT. A nested case-control study of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and serum organochlorine residues. Lancet 1997;350: 240–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alavanja MC, Hofmann JN, Lynch CF, Hines CJ, Barry KH, Barker J, Buckman DW, Thomas K, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA, Koutros S, Andreotti G, et al. Non-hodgkin lymphoma risk and insecticide, fungicide and fumigant use in the agricultural health study. PLoS One 2014;9: e109332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cocco P, Fadda D, Billai B, D’Atri M, Melis M, Blair A. Cancer mortality among men occupationally exposed to dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane. Cancer Res 2005;65: 9588–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang QP, Zhang WY, Yu JB, Zhao S, Xu H, Wang WY, Bi CF, Zuo Z, Wang XQ, Huang J, Dai L, Liu WP. Subtype distribution of lymphomas in Southwest China: analysis of 6,382 cases using WHO classification in a single institution. Diagn Pathol 2011;6: 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gross SA, Zhu X, Bao L, Ryder J, Le A, Chen Y, Wang XQ, Irons RD. A prospective study of 728 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma from a single laboratory in Shanghai, China. Int J Hematol 2008;88: 165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chihara D, Ito H, Matsuda T, Shibata A, Katsumi A, Nakamura S, Tomotaka S, Morton LM, Weisenburger DD, Matsuo K. Differences in incidence and trends of haematological malignancies in Japan and the United States. Br J Haematol 2014;164: 536–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong KY, Tai BC, Chia SE, Kuperan P, Lee KM, Lim ST, Loong S, Mow B, Ng SB, Tan L, Tan SY, Tan SH, et al. Sun exposure and risk of lymphoid neoplasms in Singapore. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23: 1055–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bassig BA, Au WY, Mang O, Ngan R, Morton LM, Ip DK, Hu W, Zheng T, Seow WJ, Xu J, Lan Q, Rothman N. Subtype-specific incidence rates of lymphoid malignancies in Hong Kong compared to the United States, 2001-2010. Cancer Epidemiol 2016;42: 15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin F, Devesa SS, Zheng W, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF Jr., Gao YT. Cancer incidence trends in urban Shanghai, 1972–1989. Int J Cancer 1993;53: 764–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ko BS, Chen LJ, Huang HH, Wen YC, Liao CY, Chen HM, Hsiao FY. Subtype-specific epidemiology of lymphoid malignancies in Taiwan compared to Japan and the United States, 2002-2012. Cancer Med 2018;7: 5820–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H, Park HJ, Park EH, Ju HY, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Jung KW, Park BK, Lee E, Eom HS, Won YJ. Nationwide Statistical Analysis of Lymphoid Malignancies in Korea. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50: 222–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.