ABSTRACT

Plants have evolved elaborate physiological and molecular responses to diverse environmental challenges, including biotic and abiotic stresses. Accumulating evidence suggests that biotic and abiotic stress signaling pathways are intricately intertwined, and factors involved in molecular crosstalk between these pathways have been identified. The R2R3-type MYB96 transcription factor is a key player that mediates plant response to drought and osmotic stresses as well as to microbial pathogens, acting as a molecular signaling integrator. Here, we report that MYB96 is required for the transcriptional regulation of SUGAR TRANSPORT PROTEIN 13 (STP13) that lies at the intersection of abscisic acid (ABA) and defense signaling pathways. MYB96 directly binds to the STP13 promoter and activates gene expression upon exogenous application of ABA and bacterial flagellin peptide flg22. Our findings indicate that MYB96 integrates biotic and abiotic stress signals and possibly induces sugar uptake to confer tolerance to a wide range of adverse environmental challenges.

KEYWORDS: Arabidopsis, apoplastic sugar, STP13, MYB96

Plants are sessile organisms and have therefore evolved complex molecular mechanisms to cope with environmental challenges, such as extreme temperature, high salinity, osmotic stress, drought, and pathogen attack. Under environmentally unfavorable conditions, plants employ a variety of defense strategies to increase plant adaptation and fitness. Different stress signals are extensively integrated by key molecular crosstalks.1,2,3 An intriguing example is that of the abscisic acid (ABA)-inducible R2R3-type MYB96 transcription factor, which not only mediates plant response to drought stress by altering root architecture and increasing cuticular wax accumulation on leaves,4,5,6 but also regulates antibacterial defense response.5

Sucrose exported from source tissues is transported through the phloem to apoplastic regions in sink tissues, where it is hydrolyzed by cell wall invertases.7,8,9 The resulting hexoses are then transported into cells in sink tissues by high‐affinity SUGAR TRANSPORT PROTEIN (STP) hexose transporters.10,11 The STP family of Arabidopsis thaliana comprises 14 monosaccharide/H+ symporters.12,13,14 Among these 14 STPs, STP1 and STP13 are largely responsible for the absorption of monosaccharides.12 In particular, STP1 shows the highest transcript level among all STPs and likely plays a major role in monosaccharide uptake under normal conditions. Additionally, apoplastic sugar levels are linked to plant tolerance to various environmental stresses. STP13 is induced by both biotic and abiotic stresses12,15 and facilitates the reabsorption of monosaccharides released from damaged cells under stress conditions.15 Consistently, STP13 confers plant tolerance to high salt, and mutations in the STP13 gene result in increased susceptibility to high salinity, with higher glucose efflux.12 Similarly, apoplastic hexose retrieval mediated by STP13 is also relevant to plant defense against microbial attack. The enzyme activity of STP13 increases antibacterial defense through the deprivation of extracellular sugar levels that serve as an energy source for pathogens.15 STP13 is induced by the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea.16 The stp13 mutants exhibit reduced glucose uptake and increased disease symptoms, whereas constitutive expression of STP13 increases glucose uptake and enhances resistance against B. cinerea.16 In addition, STP13 also interacts with the flagellin receptor FLAGELLIN-SENSITIVE 2 (FLS2) and its coreceptor BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE (BAK1) during plant defense against bacterial pathogens.15 Upon the recognition of microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), BAK1 phosphorylates STP13, which increases hexose uptake.15 This is supported by the enhanced susceptibility of the stp1 stp13 double mutant to the phytopathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 and its high apoplastic glucose levels,15 demonstrating that plant hexose transporter levels balance the hexose fluxes to mediate host–pathogen interactions.

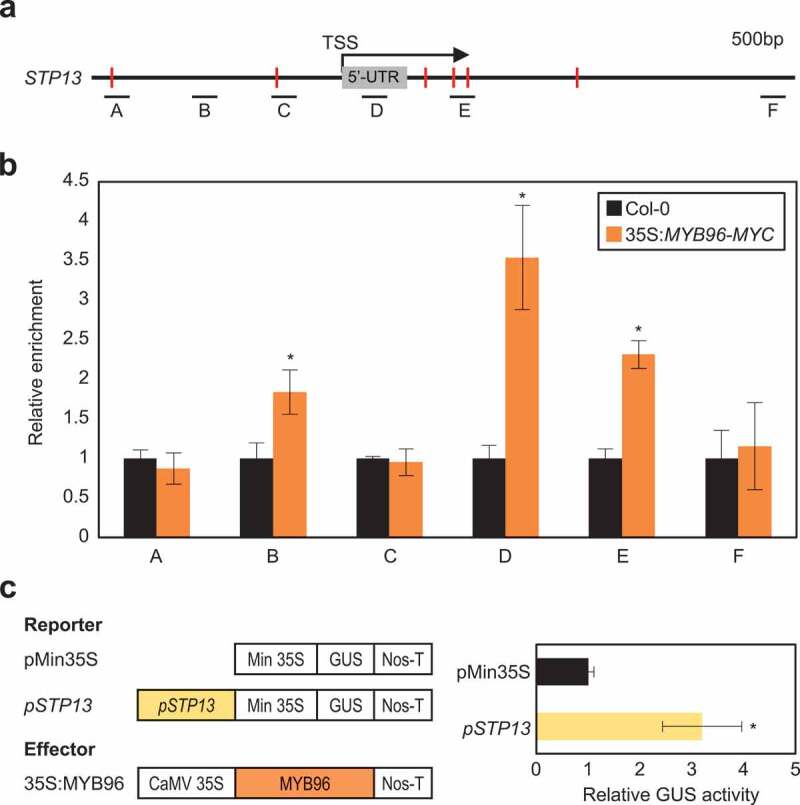

Despite the importance of apoplastic sugar levels for effective plant tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses and the knowledge that the STP13 protein is subject to multilayered regulation,15,16 the mechanism of STP13 gene regulation remains unclear. Therefore, we conducted promoter analysis of the STP13 gene. MYB-binding sites were particularly enriched in the STP13 gene promoter (Figure 1a). Taking into account that MYB96 mediates biotic and abiotic stress signaling,5,6,17 we asked if the MYB96 protein binds to the STP13 promoter. Chromatin immunoprecipitation-quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) analysis of 35S:MYB96-MYC transgenic plants showed that MYB96 binds to a proximal region of the STP13 promoter (Figure 1b), supporting the interaction of MYB96 with the STP13 locus.

Figure 1.

MYB96, an R2R3-type MYB protein, binds to the STP13 promoter. (a) Consensus MYB-binding sequences in the STP13 promoter. Red lines indicate putative MYB-binding sites. Black underbars indicate regions amplified by quantitative PCR (qPCR) following chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). (b) Analysis of ChIP assays. Total protein extracts of 35:MYB96-MYC transgenic plants grown for 2 weeks under a long-day (LD; 16 h light/8 h dark) photoperiod were immunoprecipitated with anti-MYC antibody. The fragmented genomic DNA was eluted from the protein–DNA complexes and subjected to qPCR analysis. Data represent mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) of three independent biological replicates, and statistically significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05; Student’s t-test). (c) Transient gene expression analysis. The core STP13 promoter was cloned into the reporter plasmid. The recombinant reporter and effector constructs were transiently co-expressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts, and GUS activity was measured fluorometrically. The normalized values in control protoplasts were set to 1 and represented as relative activation. Data represent mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates, and statistically significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05; Student’s t-test)

To confirm the binding of MYB96 to core sequences in the STP13 promoter, we performed transient expression assays using Arabidopsis protoplasts. The promoter region of STP13 containing the MYB96-binding site was fused to the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S minimal promoter (Figure 1c). A recombinant reporter plasmid and the 35S:MYB96 effector plasmid were co-transformed into Arabidopsis protoplasts. This co-transformation increased the GUS activity by 3-fold, compared with empty vector transfection (Figure 1c), indicating that MYB96 specifically targets sequences in the STP13 promoter region to activate gene expression.

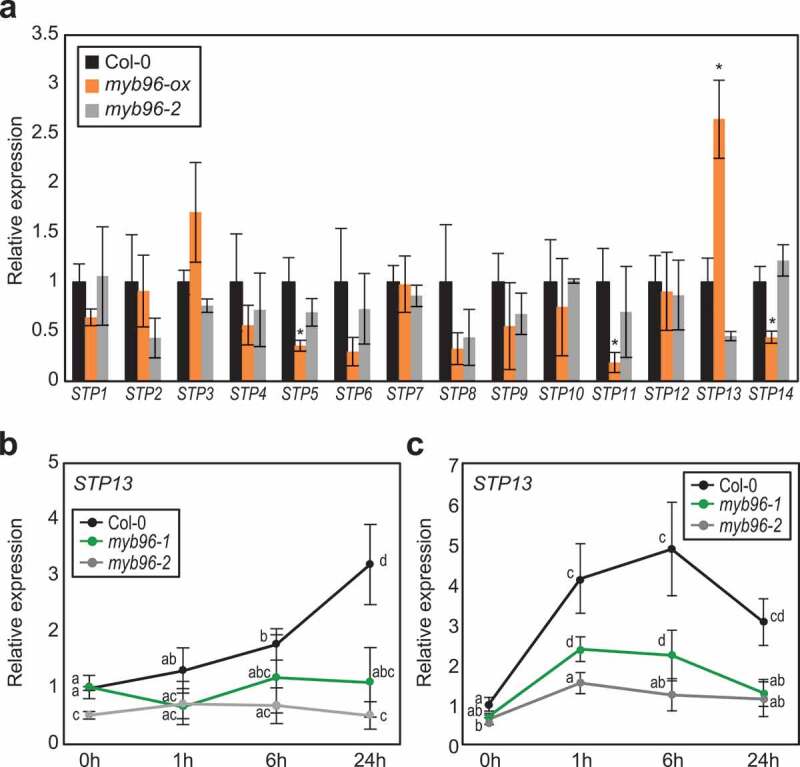

We also examined the expression of STP genes in wild-type, myb96-ox, and myb96-2 seedlings under normal growth conditions. The expression of none of the genes examined was discernibly affected by MYB96 activity, except for that of STP13 (Figure 2a). The expression of STP13 was reduced in myb96-2 plants but increased in myb96-ox plants (Figure 2a). Spatiotemporal expression patterns of MYB96 and STP13 during plant development are also similar to each other (Figure S1). Since both MYB96 and STP13 are inducible by ABA and flg22, we also analyzed transcript levels of STP13 in myb96-1 and myb96-2 mutant seedlings in the presence of ABA or flg22. The STP13 gene was induced by ABA and flg22 (Figure 2b,c), consistent with previous reports;15,16 however, the induction of STP13 by ABA and flg22 was significantly reduced in the myb96 mutants compared with the wild type (Figure 2b,c). These results indicate that MYB96 regulates STP13 expression under both biotic and abiotic stress conditions and is potentially required for STP13-dependent control of apoplastic sugar levels.

Figure 2.

MYB96-dependent induction of STP13 expression by abscisic acid (ABA) and flg22. (a) Transcript accumulation of STP genes in 2-week-old wild-type, myb96-ox, and myb96-2 seedlings grown under LDs. (b, c) Effects of ABA (b) and flg22 (c) on STP13 expression in myb96 mutants. Two-week-old seedlings grown under LDs were transferred to liquid MS medium supplemented with 100 μM ABA (b) or 1 μM flg22 (c), and incubated for the indicated time period (hours). In (a) to (c), transcript accumulation was analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Three independent biological replicates were averaged, and statistically significant differences are indicated by asterisks (*P < 0.05; Student’s t-test)

Overall, our results suggest that the MYB96–STP13 module is important for balancing extracellular sugar levels, especially under adverse environmental conditions. The regulation of transporter activity is critical for plant defense against biotic and abiotic stresses. The increased uptake of glucose from the soil and from damaged cells facilitates energy conservation in host plants and optimizes plant fitness. Thus, sugar uptake could be a basal defense strategy employed by plants against a wide spectrum of environmental challenges.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research [NRF-2019R1A2C2006915] and Basic Research Laboratory [NRF-2020R1A4A2002901] programs funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea, and by the Creative-Pioneering Researchers Program through Seoul National University [0409-20200281].

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- 1.Knight H, Knight MR.. Abiotic stress signalling pathways: specificity and cross-talk. Trends Plant Sci. 2001;6(6):1–4. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(01)01946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma R, De Vleesschauwer D, Sharma MK, Ronald PC.. Recent advances in dissecting stress-regulatory crosstalk in rice. Mol Plant. 2013;6(2):250–260. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang J, Duan G, Li C, Liu L, Han G, Zhang Y, Wang C. The crosstalks between jasmonic acid and other plant hormone signaling highlight the involvement of jasmonic acid as a core component in plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1349. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seo PJ, Lee SB, Suh MC, Park MJ, Go YS, Park CM. The MYB96 transcription factor regulates cuticular wax biosynthesis under drought conditions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2011;23(3):1138–1152. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seo PJ, Park CM. MYB96-mediated abscisic acid signals induce pathogen resistance response by promoting salicylic acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2010;186(2):471–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo PJ, Xiang F, Qiao M, Park JY, Lee YN, Kim SG, Lee YH, Park WJ, Park CM. The MYB96 transcription factor mediates abscisic acid signaling during drought stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(1):275–289. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.144220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giaquinta R. Sucrose hydrolysis in relation to phloem translocation in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1977;60(3):339–343. doi: 10.1104/pp.60.3.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lemoine R, La Camera S, Atanassova R, Dedaldechamp F, Allario T, Pourtau N, Bonnemain JL, Laloi M, Coutos-Thevenot P, Maurousset L, et al. Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front Plant Sci. 2013;4:272. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang K, Senthil-Kumar M, Ryu CM, Kang L, Mysore KS. Phytosterols play a key role in plant innate immunity against bacterial pathogens by regulating nutrient efflux into the apoplast. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(4):1789–1802. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.189217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eom JS, Chen LQ, Sosso D, Julius BT, Lin IW, Qu XQ, Braun DM, Frommer WB. Sweets, transporters for intracellular and intercellular sugar translocation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2015;25:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roitsch T, Gonzalez MC. Function and regulation of plant invertases: sweet sensations. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9(12):606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamada K, Kanai M, Osakabe Y, Ohiraki H, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Monosaccharide absorption activity of Arabidopsis roots depends on expression profiles of transporter genes under high salinity conditions. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(50):43577–43586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buttner M. The monosaccharide transporter(-like) gene family in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 2007;581(12):2318–2324. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson DA, Hill JP, Thomas MA. The monosaccharide transporter gene family in land plants is ancient and shows differential subfamily expression and expansion across lineages. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:64. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamada K, Saijo Y, Nakagami H, Takano Y. Regulation of sugar transporter activity for antibacterial defense in Arabidopsis. Science. 2016;354(6318):1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.aah5692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemonnier P, Gaillard C, Veillet F, Verbeke J, Lemoine R, Coutos-Thevenot P, La Camera S. Expression of Arabidopsis sugar transport protein STP13 differentially affects glucose transport activity and basal resistance to Botrytis cinerea. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85(4–5):473–484. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee HG, Seo PJ. The Arabidopsis MIEL1 E3 ligase negatively regulates ABA signalling by promoting protein turnover of MYB96. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12525. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.