Abstract

Due to ongoing concerns about adolescent interpersonal aggression and debates surrounding violent media, this study assesses the potential impacts of parental mediation and parenting style on mature video game play and fighting behaviors using a longitudinal, random‐digit‐dial survey of adolescents (N = 2722). By simultaneously considering fighting, M‐rated video game play, parental restrictions on media use, parenting style, and important covariates, we aim to provide further nuance to existing work on risk and protective factors for interpersonal aggression. Our results show that parental restriction has a significant, linear relationship with later fighting, whereby higher restrictions on a child’s M‐rated video game play predict decreases in reported fighting behavior. Authoritative parenting, high in both warmth and supervisory attention, also relates to decreased levels of fighting compared to other styles. Parenting style also moderated the effects of restriction, such that restriction was not equally predictive of fighting behavior across all parenting styles. However, the association between restriction and fighting was similar for highly demanding parenting styles, suggesting that authoritative parenting is not inherently superior to authoritarian. The effects of restriction were significant despite controlling for multiple covariates. Parental restriction of media use may be an effective strategy for parents concerned about violent games. Given some limitations in our dataset, we call for continued study in this area.

Keywords: adolescent, aggression, protective factors, parenting, surveys and questionnaires, video games, longitudinal studies

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Sparked by high‐profile incidents of childhood or adolescent interpersonal aggression, particularly in schools, many researchers, teachers, and parents seek to understand the risk and protective factors affecting these behaviors. An individual’s likelihood to engage in violence is multidetermined, and research results on the effects of exposure to media are split; many studies find evidence of a connection between violent media and aggression (e.g., Anderson et al., 2010), whereas others find no link or argue that connections are better explained by factors like parenting or family background (e.g., Elson & Ferguson, 2014).

In the current study, we draw on a longitudinal, random‐digit-dial survey of adolescents (N = 2722) to simultaneously test the prospective effects of M‐rated video game play, restrictive mediation,1 and parenting style on a real‐world form of aggression: fighting behaviors. Media often take the blame for aggressive outcomes, but it is important to consider other influences, such as parents’ rule-setting behaviors and how children perceive these. Indeed, researchers have called for more work to address the relationships between parental mediation (i.e., how parents engage with their children around and about media; Valkenburg, Krcmar, Peeters, & Marseille, 1999), children’s use of emerging digital media, and media effects (e.g., Collier et al., 2016; Padilla‐Walker, Coyne, & Collier, 2016; Shin & Huh, 2011). Furthermore, games are becoming omnipresent in our entertainment environment, and many parents are looking for effective strategies to mediate their children’s play habits. Although the data we analyze is from the mid‐2000s, the dearth of research in this area, combined with the dataset’s large size, national representativeness, and longitudinal scope, provides important insight about the relation between games, aggression, and parental mediation.

2 |. ADOLESCENT INTERPERSONAL AGGRESSION

Interpersonal aggression (physical fighting, bullying, gun violence, etc.) in schools is of long‐standing interest (e.g., Gorski & Pilotto, 1993; Peguero, 2011; Warner, Weist, & Krulak, 1999), and fighting in schools can result in many short‐ and long‐term consequences for victims and perpetrators. For instance, victims who fear further issues often avoid school or even drop out (Peguero, 2011; Warner et al., 1999). When victims do attend, the psychological consequences of fear and anxiety can decrease their learning effectiveness and thus their later success in life (Gorski & Pilotto, 1993; Macmillan & Hagan, 2004; Warner et al., 1999). Perpetrators also face consequences, as higher rates of peer violence correlate with lower college aspirations and higher likelihoods of anxiety, depression, and alcohol or drug use (Foshee et al., 2016). As schools’ zero‐tolerance policies increase consequences for fighting, preventive interventions remain necessary. Further, although overall rates of violence have declined, serious issues like school shootings persist, with 52 school shooting incidents occurring between 2000 and 2017 (Musu, Zhang, Wang, Zhang, & Oudekerk, 2019). This is a significant concern for students, parents, teachers, and administrators.

3 |. MEDIA VIOLENCE AND AGGRESSIVE OUTCOMES

Studies provide evidence that violent media exposure can increase an individual’s likelihood of demonstrating short‐ and long‐term aggressive cognitions and behaviors. One of the most widely used models explaining this relationship is the General Aggression Model (GAM) pioneered by Anderson and Bushman (2001, 2002). The GAM draws on multiple theories of mediated learning to describe the complete process by which violent media exposure can affect aggression; it argues, “violent media increase aggression by teaching observers how to aggress, by priming aggressive cognitions (including previously learned aggressive scripts and aggressive perceptual schemata), by increasing arousal, or by creating an aggressive affective state” (Anderson & Bushman, 2001, p. 355). Long‐term change occurs through the repetition of these processes.

Individual characteristics—family background, gender, temperament (e.g., sensation seeking), past media exposure, previous victimization, and past aggression—may also make aggressive outcomes more likely (e.g., Gentile & Bushman, 2012; Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). These influences can stack, with multiple factors serving as “a better predictor of aggression than the sum of their individual parts” (Gentile & Bushman, 2012, p. 1). Researchers have also found protective factors that can make aggressive outcomes less likely, such as parental intervention (e.g., Gentile, Lynch, Linder, & Walsh, 2004).

Considering video games specifically, experimental, cross-sectional correlational, meta‐analytic, and longitudinal studies have all suggested that violent game play can link to aggressive outcomes. Meta‐analyses found that most studies revealed a correlation between game play and aggressive outcomes (Anderson & Bushman, 2001; Anderson et al., 2003, 2010). Other studies exhibit how violent game play can desensitize players to violence and influence behavioral hostility, and physical and verbal aggression (e.g., Anderson et al., 2008; Engelhardt, Bartholow, Kerr, & Bushman, 2011; Funk, Baldacci, Pasold, & Baumgardner, 2004; Gentile & Bushman, 2012; Gentile et al., 2004; Willoughby, Adachi, & Good, 2012).

Many aspects of video games interact with aggression learning mechanisms. Not only do a high proportion of games contain violent material (Haninger & Thompson, 2004; Miller, 2010; S. L. Smith, Lachlan, & Tamborini, 2003), but most games also promote identification between player and character, making the transition from violent media to aggression more likely (Bandura, 1986; 1994; Eastin, 2006; Fischer, Kasenmuller, & Greitemeyer, 2010; Konijn, Nije Bijvank, & Bushman, 2007). Moreover, playable characters are frequently heroes whose violence is justified and rewarded within the game’s storyline and mechanics; players may consequently see violence as reasonable and beneficial, potentially increasing the likelihood of aggressive outcomes (Bandura, 1986; 1994; Carnagey & Anderson, 2005; Hartmann & Vorderer, 2010; Hartmann, Krakowiak, & Tsay‐Vogel, 2014; S. L. Smith et al., 2003). Video games thus present a key area of concern for media violence and aggression research, with the medium’s features potentially strengthening the relationship between stimulus and response.

On the other hand, some studies have found no relationship between violent media and aggressive outcomes (see Elson & Ferguson, 2014; Ferguson, Olson, Kutner, & Warner, 2014; Savage & Yancey, 2008). Further research is necessary to continue clarifying the relationship between media and aggression. In particular, Ferguson et al. (2014) call for researchers to concentrate on the relationship between media violence and “meaningful real‐world outcomes such as violent crime, physically aggressive behaviors toward other persons, bullying, domestic violence, and so forth” (p. 778), rather than relying on the more abstract measures common to experimental studies. Consequently, we focus here on a meaningful real‐world outcome—physical fighting—as well as alternative explanations, such as parenting.

4 |. PARENTAL MEDIATION

Researchers have identified three types of parental intervention into children’s media use: coviewing, active mediation, and restrictive mediation (parental restriction; An & Lee, 2010; Clark, 2011; Nathanson, 1999, 2002; Nikken & Jansz, 2006; Valkenburg et al., 1999). The current study focuses on restriction—setting rules about media use (e.g., limiting how long a child can use media or forbidding them from using certain types). Parents employ restriction frequently across various media (An & Lee, 2010; Nikken & Jansz, 2006; Nikken, Jansz, & Schouwstra, 2007; Padilla‐Walker et al., 2016; Schaan & Melzer, 2015; Valkenburg et al., 1999; Warren, 2001), and for games in particular. Schaan and Melzer (2015) found that parents employed varied approaches to mediate their children’s interactions with television, but primarily regulated video games through restrictive means. The authors suggested that parents may feel limited in their potential to employ active mediation or coviewing effectively, given a lack of familiarity with digital technologies.

Parental restriction has primarily shown positive results in studies of television (e.g., Nathanson, 2002; Van den Bulck & Van den Bergh, 2000), but results for video games are more equivocal. While multiple studies (Benrazavi, Teimouri, & Griffiths, 2015; Collier et al., 2016; Gentile et al., 2004; Martins, Matthews, & Ratan, 2017) have found restriction effective in reducing games’ potential negative impacts (such as problematic play patterns), others have found no relation between parental restriction and problematic game use (Choo, Sim, Liau, Gentile, & Khoo, 2015; L. J. Smith, Gradisar, & King, 2015). Similarly, Lee and Chae (2007) found that restriction was ineffective in limiting children’s Internet use.

There is also some evidence that restriction can backfire, causing children to seek out the restricted medium in what researchers have called a “forbidden fruit” effect. In these instances, high levels of restriction correlate with increased, rather than decreased, aggressive outcomes (Nathanson, 1999, 2002). This backlash is particularly likely for adolescents, who are navigating their entry into adulthood; parental restriction may increase the desire for the forbidden medium as a way of expressing independence (Clark, 2011; Nathanson, 2002; Nikken & Jansz, 2007). Hence, parents who do not restrict media use and parents who overuse restrictions may both see higher aggressive outcomes among their children than parents whose restrictions are more moderate.

Consequently, we tested two competing hypotheses. Most parental mediation research predicts that more restriction is better—a linear effect. A forbidden fruit effect at high levels of restriction would be consistent with a curvilinear effect.

H1: As parents increase restrictions on their child’s M‐rated video game play, aggressive outcomes should decrease in a primarily linear fashion.

H2: In line with “forbidden fruit” research, parental restriction should display a curvilinear pattern, in which extreme restriction is associated with greater aggressive outcomes than more moderate levels of restriction.

5 |. INFLUENCE OF PARENTING STYLE

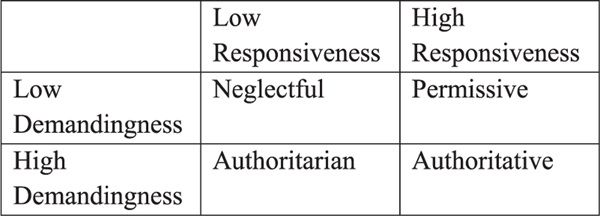

Parenting style may influence both aggressive outcomes and the degree to which restriction affects those outcomes. Parenting styles, as defined by Baumrind (1971), differ along a typology of responsiveness and demandingness. Responsiveness, or warmth, refers to how supportive a parent is of their child. Highly responsive parents discuss household decisions with their children, comfort them when they are upset, and show they care in a variety of ways. Demandingness, or supervision, refers to a parent’s expectations for their child. Highly demanding parents set rules and impose consequences when rules are violated. As outlined in Figure 1, the comparison of these characteristics results in four parenting styles: authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, or neglectful. Parenting styles are first relevant because authoritative parents, who are higher in both responsiveness and demandingness, are more likely to take personal responsibility for mediating their children’s media use than parents who adopt other styles (Walsh, Laczniak, & Carlson, 1998). Therefore, we hypothesize:

FIGURE 1.

Model of parenting styles

H3: Authoritative parenting will be related to higher levels of restriction than other parenting styles.

Parenting styles are also associated with different outcomes for children’s media use, with authoritative parenting as the most effective approach. Authoritative parents are more likely to communicate about media use rules, and their children have higher feelings of closeness to their parents and of satisfaction in their parent‐child relationship (Nathanson, 2002). These factors predict decreased negative media effects and children’s higher likelihood to accept parental restrictions on their media use (e.g., Byrne & Lee, 2011; Choo et al., 2015; Linebarger, 2015). Parental restriction may thus be more effective when used by authoritative parents than by parents who are authoritarian, neglectful, or permissive.

H4: Parenting style will moderate the relation between restriction of M‐rated video game play and aggressive outcomes, such that authoritative parenting will be associated with the lowest negative effects.

6 |. METHODS

6.1 |. Participants and procedure

The data for this study were collected via a multiwave random‐digit-dial telephone survey of U.S. adolescents (10–14 years old at baseline) reflecting the U.S. population of this age in terms of gender, ethnic/racial background, and socioeconomic status. Details regarding sample selection and survey procedures have been previously reported (e.g., Dal Cin, Stoolmiller, & Sargent, 2012; Sargent et al., 2005). Of 9849 screened households meeting eligibility standards (i.e., residences with at least one adolescent), 6522 adolescents completed the survey at Wave 1 (66% of the total eligible group).

Respondents were first contacted between June and October 2003, with three follow‐up surveys thereafter. Researchers attempted to recontact all the original participants at each wave. The current study utilizes responses from survey Waves 3 and 4; the third wave was the first in which information on video game play was collected. Henceforth, we refer to Wave 3 as “Time 1” (T1) and Wave 4 as “Time 2” (T2). The T1 survey was conducted in 20052 and the T2 survey 8 months later. We limited our analyses to respondents (N = 2730) who played video games at T1 and responded again at T2. Eight respondents had missing observations for critical variables of interest, bringing the final sample size to 2,722. Participants’ average age was 13.67 years (SD = 1.41) at T1 and 14.36 years (SD = 1.41) at T2. Boys made up 69.99% of this final sample.

The adolescent provided all responses in the current analyses, including measures of parenting style. Past research indicates that child reports of parenting style are more strongly associated with outcome measures than parent reports (Fujioka & Austin, 2002; Gentile, Nathanson, Rasmussen, Reimer, & Walsh, 2012; Livingstone & Helsper, 2008); in terms of effects, how the child perceives their parent appears to matter more than how the parent thinks of themselves.

6.2 |. Measures

Descriptive statistics for all variables are reported in Table 1, and details on question wording and response options are in the Appendix.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics

| M | SD | Cronbach's α | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental mediation | |||

| Video game restriction | 0.45 | 0.39 | – |

| Movie restriction | 0.48 | 0.33 | – |

| Parenting style | |||

| Parental demandingness (4–16) | 12.72 | 2.53 | .66 |

| Parental responsiveness (5–20) | 16.19 | 3.18 | .8 |

| Fighting | |||

| Time 1 | 0.16 | 0.21 | .32 |

| Time 2 | 0.15 | 0.21 | .39 |

| Covariates | |||

| Household income (Median = $50–75k/y) | – | – | – |

| Parent education (Median = some college) | – | – | – |

| Sensation seeking | 0.37 | 0.21 | – |

| Rebelliousness | 0.14 | 0.17 | – |

| School performance | 0.64 | 0.27 | – |

| Smoking behavior | 0.09 | 0.2 | – |

| Violent movie viewing | 0.23 | 0.18 | .92 |

Note: All variables are scaled 0–1, unless otherwise indicated.

6.2.1 |. Parental restriction

Parents use video game ratings as tools for restriction (Nikken et al., 2007; Shin & Huh, 2011). In the United States, the Electronic Software Ratings Board (ESRB) places an “M” (mature) rating on games suitable for players 17 and older. As our respondents were under 17, parents following ESRB ratings should restrict access to these games. Restriction was measured using the question, “How often do your parents let you play M‐rated video games?” with higher scores indicating higher parental restrictions. A direct statistical test of reliability (e.g., Cronbach’s α) is not possible for this single‐item measure, but reliability can be inferred from tests of criterion and construct validity (as unreliable measurement attenuates correlations with other variables). Respondents were asked if they had played specific M‐rated games—Grand Theft Auto III (n = 1533) and Manhunt (n = 302). If the measure of parental restriction on M‐rated game play is reliable (and valid), as it increases, the number of specific M‐rated games played should decrease. Parental restriction was negatively correlated with M‐rated game play, Spearman’s ρ = −.55, p < .001.

Parents tend to employ rules consistently across different media (Gentile & Walsh, 2002). Therefore, parents who restrict access to M-rated games should likewise restrict access to R‐rated movies. As an additional validity check, parental restriction of R‐rated movie viewing was measured using the question, “How often do your parents let you watch movies or videos that are rated R?” The correlation of M‐rated game and R‐rated movie restrictions was r = .60, p < .001.

6.2.2 |. Parenting style

Measures of the responsiveness and demandingness of a child’s primary caregiver (usually their mother) were those used by Hull, Draghici, and Sargent (2012). Items for responsiveness included questions such as: my primary caregiver “listens to what I have to say” or “makes me feel better when I am upset.” Demandingness was measured via items including: my primary caregiver “knows where I am after school” and “makes sure I go to bed on time.”

We summed the answers for each component, with positive numbers indicating higher levels. Because we employ the two dimensions of parenting style together as an interaction, standardized versions are used in all analyses. Thus, a neglectful parenting style is denoted by both low (−1SD) responsiveness and demandingness, permissive by high (+1SD) responsiveness and low (−1SD) demandingness, authoritarian by low (−1SD) responsiveness and high (+1SD) demandingness, and authoritative by both high (+1SD) responsiveness and demandingness.3

6.2.3 |. Aggressive outcomes

We examine self‐reported fighting behavior at each wave using two items: “During the past month, how many times did you hit, slap, or shove someone who was not a member of your family?” and “During the past month, how many times were you sent to the school office because of fighting?” Response options were never, once, twice, and three or more times. Though not highly correlated (T1, t[2720] = 13.47, r = .25; T2, t[2720] = 16.04, r = .29; p < .001), these items were averaged to create 0‐to‐1 scales, with higher scores indicating more fighting. Previous studies using this dataset reveal that doing so yields similar results as conducting independent analyses for each item (Hull, Brunelle, Prescott, & Sargent, 2014).

6.2.4 |. Covariates

As in previous studies using this data (e.g., Dal Cin et al., 2012; Hull et al., 2014; Sargent et al., 2005), analyses included measures of variables expected to covary with media rules, parenting style, and aggressive outcomes. Covariates were selected to be consistent with those used by Hull et al. (2014), and included age (in years), gender (boy = 1, girl = 2), parental income, parental education, sensation seeking, rebelliousness, self‐reported school performance, smoking, and violent movie viewing. All were assessed at T1 except gender, parental income, and parental education, which had been measured upon entry into the study.

7 |. RESULTS

7.1 |. Restriction and aggressive outcome

To test H1, we first specified a simple regression model with T1 M‐rated game restriction and T1 fighting as predictors of T2 fighting. The model predicted 20% of the variance in T2 fighting (R2 = .26; F(2, 2719) = 472.71; p < .001), and restriction significantly predicted decreased T2 fighting (b = −.05; p < .001). We then specified two models including covariates and T1 fighting. The first included all covariates except for violent movie viewing (R2 = .30; F(10, 2534) = 109.31; p < .001). Given the likely overlap between violent movie viewing and violent game play (Gentile & Walsh, 2002), this estimates the role of parental restriction without interference due to multicollinearity; restriction remained a significant predictor of T2 fighting (b = −.03, p = .011). Finally, we included violent movie viewing in a final model (R2 = .30; F(11, 2533) = 100.39; p < .001), and the relation of restriction and T2 aggression became only marginally significant (b = −.02; p = .075). Therefore, we find qualified support for H1 (full results are displayed in Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Models predicting Time 2 aggression with parental restriction and covariates

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental restriction | −.05**** (.01) | −.03** (.01) | −.02* (.01) |

| Time 1 aggression | .48**** (.02) | .37**** (.02) | .36**** (.02) |

| Age | −.01** (.00) | −.01** (.00) | |

| Female | −.02** (.01) | −.02** (.01) | |

| Household income | −.01**** (.00) | −.01**** (.00) | |

| Parent education | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | |

| Sensation seeking | .06** (.02) | .06** (.02) | |

| Rebelliousness | .20**** (.03) | .20**** (.03) | |

| School performance | −.03** (.01) | −.03** (.01) | |

| Smoking behavior | .00 (.02) | −.01 (.02) | |

| Violent movie viewing | .06*** (.02) | ||

| Constant | .09**** (.01) | .23**** (.04) | .22*** (.04) |

| N | 2722 | 2545 | 2545 |

| R2 | .26 | .30 | .30 |

| F | 472.71**** | 109.31**** | 100.39**** |

| df | 2; 2719 | 10; 2534 | 11; 2533 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We tested H2 by adding a second step to this final model, so that the linear effect of restriction on T2 fighting was tested in step one and the possible curvilinear effect in step two. The addition of the quadratic factor explained no further variance (R2 = .30; F(12, 2532) = 92.03; p < .001), and the relation of the quadratic factor to change in fighting was nonsignificant (b = .02; p = .568). H2 is unsupported.

7.2 |. Authoritative parenting and restrictive mediation

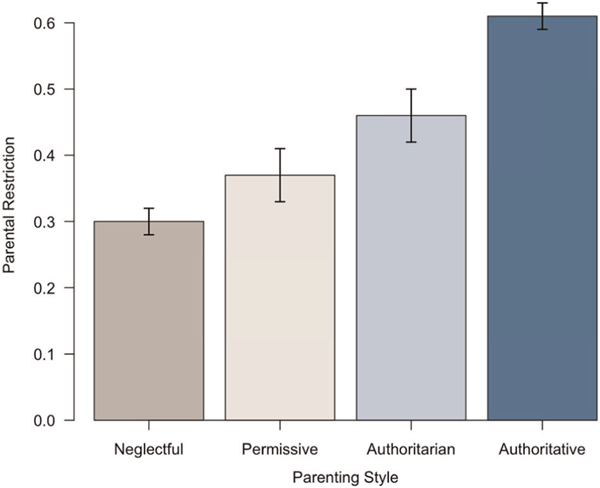

We estimated the value for parental mediation for each parenting style by modeling the interaction between standardized versions of the responsiveness and demandingness variables; see Table 3, Step 2. We generated the estimates by performing simple slopes analyses on 5,000 bootstrap samples of the original dataset, sampled with replacement, to calculate the values for parental mediation. The below results are the Ms, 95% confidence intervals, and SEs ([CIupper – CIlower]/3.92) for their respective values based on those 5,000 bootstrap samples. Authoritative parents engaged in the highest level of parental restriction (M = .61, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [0.59, 0.64]), followed by authoritarian (M = .46; SE = 0.02; 95% CI [0.42, 0.50]), permissive (M = 0.37; SE = 0.02; 95% CI [0.33, 0.41]), then neglectful (M = .30; SE = 0.01; 95% CI [0.28, 0.32]) parents; see Figure 2. Authoritative parents engaged in greater parental restriction than did neglectful, permissive, and authoritarian parents, ts(9998) = 21.92, 10.73, and 6.71, respectively; p s < .001. H3 is supported.

TABLE 3.

Models predicting parental restriction with responsiveness × demandingness interaction

| Step 1 | Step 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Parental responsiveness | .05**** (.01) | .06**** (.01) |

| Parental demandingness | .10**** (.01) | .10**** (.01) |

| Responsiveness × demandingness | .02**** (.01) | |

| Constant | .45**** (.01) | .43**** (.01) |

| R2 | .11 | .11 |

| F | 170.37**** | 118.45**** |

| df | 2; 2719 | 3; 2718 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 2722 for all models. All models used standardized versions of all predictor variables.

p < .001.

FIGURE 2.

Predicted values of parental video game restriction for four parenting styles. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

7.3 |. Parenting style, restriction, and aggressive outcome

To test for a possible moderation effect, we specified a three‐step regression model (with standardized scores for all predictors). Step one predicted T2 fighting from T1 fighting and parental restriction, responsiveness, and demandingness. Step two added the interaction between parental responsiveness and demandingness, predicting the amount of fighting behavior for children of different parenting styles, controlling for effects of parental restriction. Finally, step three added the interaction between parental restriction, responsiveness, and demandingness (with lower order interaction terms) allowing us to determine the effect of restriction on fighting behavior for different parenting styles. All models are reported in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Models predicting Time 2 aggression with parental restriction × responsiveness × demandingness interaction

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 aggression | .10**** (.00) | .10**** (.00) | .10**** (.00) |

| Parental restriction | −.02**** (.00) | −.02**** (.00) | −.02**** (.00) |

| Parental responsiveness | −.01*** (.00) | −.01*** (.00) | −.01*** (.00) |

| Parental demandingness | .00 (.00) | −.01 (.00) | −.01* (.00) |

| Responsiveness × demandingness | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | |

| Restriction × responsiveness | .01 (.00) | ||

| Restriction × demandingness | −.01** (.00) | ||

| Restriction × responsiveness × demandingness | .00 (.00) | ||

| Constant | .15**** (.00) | .15**** (.00) | .15**** (0.00) |

| R2 | .26 | .26 | .26 |

| F | 241.73**** | 193.78**** | 122.10**** |

| df | 4; 2717 | 5; 2716 | 8; 2713 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses. N = 2722 for all models. All models used standardized versions of all predictor variables

.p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

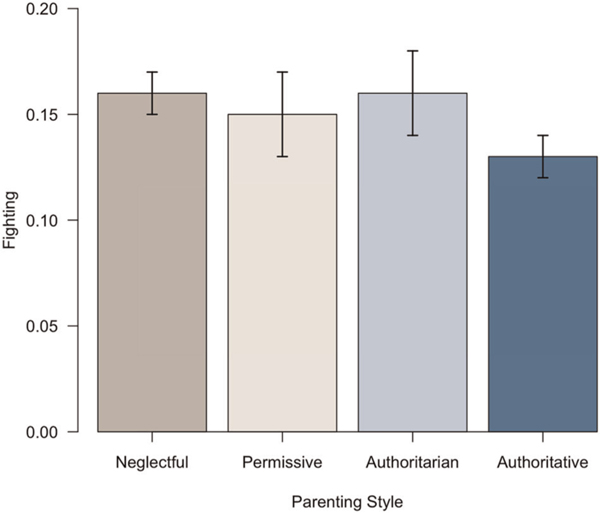

Using the second‐step model, we predicted the amount of fighting behavior for children who perceive the four parenting styles, controlling for parental restriction; see Figure 3. As was done for the H3 analyses, we conducted simple slopes analyses on the 5,000 bootstrap samples to generate the values for fighting behavior for the four parenting styles. Children who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritative engaged in the least fighting behavior (M = 0.13; SE = 0.01; 95% CI [0.12, 0.14]). This was significantly less fighting than among children who perceived neglectful or authoritarian parenting, both M s = 0.16; SEs = 0.01; 95% CIs [0.15, 0.18] and [0.14, 0.18], respectively; t s(9998) = 2.12, p s = .034. Children who perceived their primary caregiver as permissive did not engage in any more or less fighting behavior (M = 0.15; SE = 0.02; 95% CI [0.13, 0.17]) than children who perceived other parenting styles.

FIGURE 3.

Fighting behavior (predicted values) for children perceiving four parenting styles. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

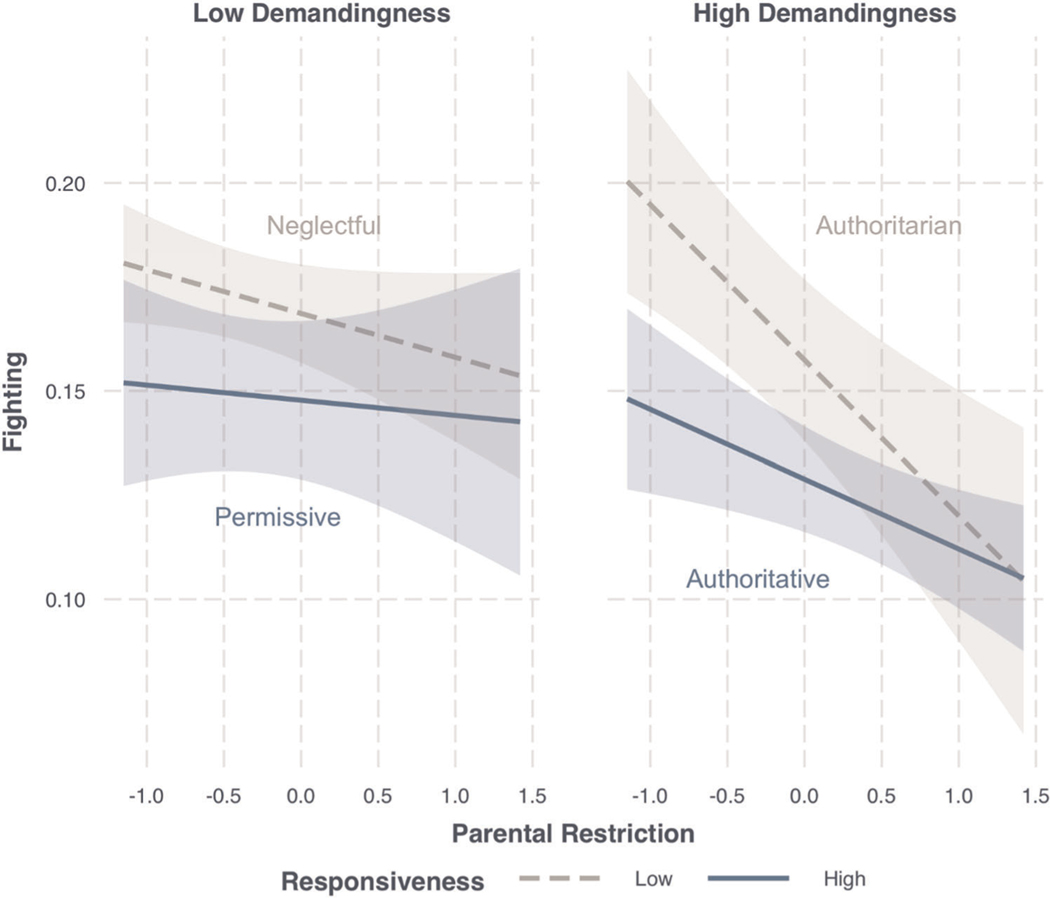

Using the Step 3 model, we examined the effect of parental restriction on fighting behavior at different parenting styles (see Figure 4), then conducted simple slopes analyses to estimate these effects. Parental restriction had no effect on fighting behavior if the primary caregiver was perceived as permissive (β = .00, SE = 0.01, p = .706) or neglectful (β = −.01, SE = 0.01, p = .092). Restriction was effective for more demanding parents: children who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritarian (β = −.04, SE = 0.01, p < .001) or authoritative (β = −.02, SE = 0.01, p = .007) engaged in less fighting behavior if their parents restricted M‐rated game play more (+1SD of restriction) than if their parents restricted M‐rated game play less (−1SD of restriction). There was no statistically significant difference between the strength of the effect for these two parenting styles, β = .01, F(1, 2,713) = 2.99, p = .084. In other words, the effect of restriction on fighting behavior was the same for authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles.

FIGURE 4.

The effect of parental restriction on fighting behavior for children perceiving four parenting styles. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. The scale for parental restriction is in standard deviations. In the left panel (low demandingness), the dashed line denotes neglectful parenting and the solid line denotes permissive parenting. In the right panel (high demandingness), the dashed line denotes authoritarian parenting and the solid line denotes authoritative parenting [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Estimates of children’s fighting behavior for all parenting styles at both low (−1SD) and high (+1SD) levels of restriction are reported in Table 5. As shown in Figure 4, for children whose parents engaged in low levels of restriction, those who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritative engaged in less fighting (M = 0.15; SE = 0.0; 95% CI [0.12, 0.17]) than those who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritarian (M = 0.20; SE = 0.01; 95% CI [0.17, 0.22]); t(9998) = 3.54; p < .001; see Table 5. For children whose parents engaged in high levels of restriction, there was no difference in the fighting behavior of children who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritative and those who perceived their primary caregiver as authoritarian, t(9998) = 0.71, p = .480. The children of authoritative parents engage in less fighting than the children of neglectful parents both when those parents employ low and high restriction, ts(9998) = 2.12 and 3.54, p = .034 and p < .001, respectively. Comparing authoritative and permissive styles, there is no difference in children’s fighting behavior when parents of either style adopt lower levels of restriction, t(9998) = 0, p = .99; however, the children of high‐restriction authoritative parents fight less than the children of high‐restriction permissive parents, t(9998) = 2.12, p = .034. This result warrants further scrutiny, as Figure 4 reveals that the confidence intervals for authoritative and permissive parents at high levels of restriction would overlap, indicating no statistically significant difference. The discrepancy between these results is likely due to the nature of the analyses: The size of the confidence intervals in Figure 4 are affected by the actual n at a given parenting style and level of restriction, whereas the estimates, SEs, and 95% CIs used for the t tests and reported in Table 5 are based on 5,000 bootstrap samples.

TABLE 5.

Estimates and 95% confidence intervals for fighting behavior for all parenting styles at both low and high levels of parental restriction

| Low responsiveness |

High responsiveness |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction | Est. (SE) | 95% CI | Restriction | Est. (SE) | 95% CI | |

| Low demandingness | −1SD | 0.18 (0.01) | [0.16, 0.19] | −1SD | 0.15 (0.01) | [0.12, 0.18] |

| +1SD | 0.16 (0.01) | [0.14, 0.18] | +1SD | 0.14 (0.01) | [0.12, 0.17] | |

| High demandingness | −1SD | 0.20 (0.01) | [0.17, 0.22] | −1SD | 0.15 (0.01) | [0.12, 0.17] |

| +1SD | 0.12 (0.01) | [0.09, 0.15] | +1SD | 0.11 (0.01) | [0.10, 0.12] | |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses; 95% confidence intervals are based on 5000 bootstrap samples

In sum, H4 is not supported. Although, after controlling for parental restriction, the children of authoritative parents engage in less fighting behavior than the children of both neglectful and authoritarian parents, the effect of parental restriction on fighting was similar for children of both authoritative and authoritarian parents. There was a statistically significant difference between the amount of fighting behavior of children of authoritative and authoritarian parents who engage in low levels of restriction, but not those who engage in high levels of restriction. Conversely, the children of lowrestriction authoritative and permissive parents have similar levels of fighting, but there is tentative evidence that the children of high-restriction authoritative parents fight less than the children of high‐restriction permissive parents. Further, parental restriction statistically significantly reduces the fighting behavior of children of authoritative (and authoritarian) parents but has no effect on the fighting behavior of the children of neglectful parents. The children of authoritative parents fought less than the children of neglectful parents at both low and high levels of restriction.

8 |. DISCUSSION

The goal of the current study was to examine how parenting style and restrictions on media use relate to reported fighting. Using longitudinal, nationally representative survey data, it has demonstrated interesting, if not hypothesized, results, showing that restriction of mature game play was related to lower levels of fighting, particularly for children who perceive specific parenting styles. The results showed that parenting style was, in addition to other factors, a statistically significant buffer against increases in fighting, particularly for the children of more demanding (authoritarian and authoritative) parents.

H1 predicted that increasing levels of restriction would predict less fighting, while H2 proposed that high levels of restriction could result in a “forbidden fruit” effect, potentially driving children towards more aggressive media. H1 was supported (even in the presence of important covariates), but H2 was not. Higher levels of restriction were linearly related to less fighting. Although this is good news for parents who impose rules, it may be premature to argue that all levels of restriction are equal. The respondents in the current study were in their early teens (13‐14 years old); older adolescents may be more inclined to rebel against parental rules than younger adolescents (Nathanson, 2002). Further, the ordinal nature of the restriction measure may mask differences between levels of restriction that would be detectable using a more sensitive measure of game restrictions. Therefore, these findings should be treated with caution; imposing rules on children’s gameplay may be a positive step towards mitigating aggressive outcomes, but rules should still be well thought‐out and logically imposed.

Support for parenting style hypotheses was mixed. H3, which predicted that authoritative parenting would be related to higher levels of restriction, was supported, consistent with work on other media. H4, which predicted that parenting style would serve a moderating role and that authoritative parenting would yield the lowest negative effects, was unsupported. Authoritative parenting was associated with less fighting behavior than neglectful and authoritarian parenting, controlling for restriction. However, restriction had no effect on fighting behavior when parents were less demanding (neglectful or permissive), but it led to less fighting when parents were more demanding (authoritarian and authoritative). Thus, although authoritative parenting was associated with the best outcomes overall, the children of authoritarian parents who engaged in high levels of restriction exhibited the same lower levels of fighting as the children of authoritative parents who engaged in high levels of restriction.

Our analyses did reveal additional interesting, though not hypothesized, patterns on which future research can build. Although the effect of restriction on fighting was similar for both authoritarian and authoritative styles, there were differences in fighting behavior between the children of authoritarian and authoritative parents across the range of restriction. When less restriction was enacted, the children of authoritarian parents fought more often than the children of authoritative parents; however, when more restriction was enacted, the children of authoritarian and authoritative parents engaged in the same amount of fighting behavior. Restriction had no effect for permissive parents but did for authoritative ones, and our analyses provide tentative evidence that at high levels of restriction, the children of authoritative parents fight less than those of permissive ones. Whether they employed low or high restriction, authoritative parents’ children fought less than neglectful parents’ children. We suggest designing future research to further probe these relationships.

Given the age of the dataset employed here, these results measure the relationship between videogame play, aggressive outcomes, parental restriction and parenting style at a time now over a decade past. This does not, however, mean they have no use in the present. Games have become more realistic (potentially exacerbating the impacts of violent content) and more pervasive (moving onto mobile phones, social media, and other platforms); parents’ need for effective mediation techniques has likely increased, and researchers continue to call for investigations into the relationships between media, aggressive outcomes, and parental mediation (e.g., Collier et al., 2016; Padilla‐Walker et al., 2016; Shin & Huh, 2011). Moreover, recent calls for more transparency in science advocate for secondary analysis of high‐quality data. One challenge of secondary analysis is that the number of relevant datasets is often limited, and researchers may find that the highest‐quality data are somewhat historical. It is important to keep in mind that all research findings are produced in a historical context, and thoughtful consideration of how context changes over time is a source of generative insight.

This study serves as a foundation for further investigation, as the size and scope of the dataset provide evidence that restriction, together with more responsive and demanding parenting, may affect relations between videogame play and aggressive outcomes. Future research should aim to: collect more detailed data regarding types of parental mediation, assess restriction using a continuous measure, and include assessments of active mediation and co‐viewing. This could reveal more nuanced relationships between mediation style and parenting style and test the significance of results that remain somewhat equivocal. It would also be interesting to test the impacts of game restriction and parenting on more diverse outcome variables, such as the reckless driving behaviors or alcohol and smoking behaviors measured by Hull et al. (2012, 2014). Finally, our dataset lacks overall measures of videogame play (e.g., hours/day) and violent gameplay specifically (as games can be M‐rated for several reasons, our restriction measure is a conservative proxy for violence rather than a direct metric of it). Adding these specific measures to future studies will help distinguish more clearly the impacts of violent gameplay vs. general gameplay or exposure.

Despite study limitations, we can conclude that restrictions placed on a child’s M‐rated game play do appear to relate to later fighting behavior, even after controlling for age, gender, parental income and education, deviant behaviors, school performance, sensation seeking, rebelliousness, and previous fighting. Further, we found that this relationship was linear, with no evidence that parents’ restriction efforts provoke a forbidden fruit effect (at least among early teens). Consistent with previous research, our results show that authoritative parents mediate their children’s media use more heavily than do more permissive, authoritarian, and neglectful parents, and that authoritative parenting generally results in positive outcomes for children. Although other styles can be effective depending on restriction, parents should strive to build a relationship with their children that is high in both responsiveness and demandingness. When a child has clear guidelines, but also feels supported and loved, possible negative media effects are likely to be ameliorated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data collection funded by the National Institutes of Health CA77026 and AA015591, PI James Sargent. The authors would like to thank James D. Sargent for his assistance in making the data available and Jay G. Hull for his thoughtful and helpful comments on a previous version of the manuscript.

Funding information

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Grant/Award Number: AA015591; National Cancer Institute, Grant/Award Number: CA77026

APPENDIX. Question‐wording and response options for variables of interest

| Construct and items | Response options | Coded values |

|---|---|---|

| Play of M-rated games (higher values = more play) | ||

| Have you played Grand Theft Auto III? (yes/no) | Played both (n = 268) | 1 |

| Have you played Manhunt? (yes/no) | ||

| Played one (n = 1299) | .5 | |

| Played neither (n = 1155) | 0 | |

| Parental mediation | ||

| Video game restriction (higher values = more restriction) | ||

| “How often do your parents let you play M-rated video games?” | Never (1) | 1 |

| Once in a while | .66 | |

| Sometimes | .33 | |

| All the time | 0 | |

| Movie restriction (higher values = more restriction) | ||

| How often do your parents let you watch movies or videos that are rated R? | “Never” | 1 |

| Once in a while | .66 | |

| Sometimes | .33 | |

| All the time | 0 | |

| Parenting—demandingness/supervision (responses to each question coded 1–4; answers summed to create overall demandingness measure) | ||

| My [primary caregiver]... | ||

| • Checks to see if I do my homework | Not like her/him A little like her/himA lot like her/ him Just like her/him |

|

| • Knows where I am after school | ||

| • Makes sure I go to bed on time | ||

| • Asks me what I do with my friends | ||

| Parenting—responsiveness (responses to each question coded 1–4; answers summed to create overall responsiveness measure) | ||

| My [primary caregiver]... | ||

| • Listens to what I have to say | Not like her/him A little like her/him A lot like her/ him Just like her/him |

|

| • Likes me just the way I am | ||

| • Is pleased with how I behave | ||

| • Makes me feel better when I'm upset wants to hear about my problems | ||

| Aggressive outcomes (responses to each question coded 1–4; items averaged to create overall 0–1 fighting scale) | ||

| During the past month, how many times did you hit, slap, or shove someone who was not a member of your family? | Never | |

| Once | ||

| Twice | ||

| Three or more times | ||

| During the past month, how many times were you sent to the school office because of fighting? | Never | |

| Once | ||

| Twice | ||

| Three or more times | ||

| Sensation seeking (responses to each question coded 1–4; answers summed to create overall measure) | ||

| I like to do scary things | Not like you | |

| I like to do dangerous things | A little like you | |

| I often think there is nothing to do | A lot like you | |

| I like to listen to loud music | Just like you? | |

| Rebelliousness (responses to each question coded 1–4; answers summed to create overall measure) | ||

| I get in trouble at school | Not like you | |

| I argue a lot with other kids | A little like you | |

| I do things my parents would not want me to do | A lot like you | |

| I do what my teachers tell me to do | Just like you? | |

| I argue with teachers | ||

| I like to break the rules | ||

| School performance | ||

| How would you describe your grades in school? Would you say your grades were... | Excellent | 1 |

| Good | .66 | |

| Average | .33 | |

| Below average | 0 | |

| Smoking (Responses to below questions combined in a scale; no for Q1 coded as zero, other questions coded 1–4) | ||

| Have you ever tried smoking a cigarette, even just a puff? | No = nonsmokers, 0 | 0 |

| Yes = sorted according to next question (0.5 or 1) | ||

| How many cigarettes have you smoked in your life? | Experimental smokers: | .5 |

| Just a few puffs to 99 cigarettes | ||

| Established smokers: 100+ cigarettes | 1 | |

| Violent movie viewing | ||

| Respondents were asked whether they have seen (yes/no) 55 different movies. A movie violence exposure scale was calculated using the ratio of violent movies seen by the participant. | No violent movies | 0 |

| Some subset of violent movies | Between 0 and 1 | |

| Maximum observed movie violence score | 1 | |

| Questions asked of parents at initial study enrollment Household income | ||

| In studies like this, households are sometimes grouped according to | 1. $10,000 or less | |

| income. Please tell me which group best describes the total | 2. $10,001 to $20,000 | |

| income of all persons living in this household over the past year? | 3. $20,001 to $30,000 | |

| Please include income from all sources, such as salaries, interest, | 4. $30,001 to $50,000 | |

| retirement, or any other source for all household members. | 5. $50,001 to $75,000 | |

| 6. Over $75,000? | ||

| Parent education | ||

| What is the highest grade or year of school that *you* completed? | 1. Up to 8th grade | |

| 2. 9th-11th grade | ||

| 3. 12th grade but no diploma | ||

| 4. High-school diploma/equivalent | ||

| 5. Voc/tech program after high school but no diploma | ||

| 6. Voc/tech diploma after high school | ||

| 7. Some college but no degree | ||

| 8. Associate's degree | ||

| 9. Bachelor's degree | ||

| 10. Some graduate or professional school but no degree | ||

| 11. Master's degree | ||

| 12. Doctorate degree | ||

| 13. Professional degree beyond bachelors (e.g., MD, DDS, JD, etc.) |

Footnotes

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study were used with the permission of James D. Sargent. They are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Parental mediation research uses the term “restrictive mediation” to refer to parents’ rule‐setting behaviors around media. For readability and to avoid confusion with moderator/mediator variables, we will refer to this throughout the rest of the article as restriction or parental restriction.

This older data remains relevant due to the understudied nature of parental mediation and parenting style on gaming. Further comments on our views of the strengths and limitations of this dataset are in the discussion.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for identifying a coding error in our original analysis; the current analysis, suggested by the reviewer, corrects this error and allows comparisons across all four parenting styles. Please contact the corresponding author with any questions regarding this process.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2009). Policy statement‐media violence. Pediatrics, 124(5), 1495–1503. 10.1542/peds.2009-2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An S‐K, & Lee D. (2010). An integrated model of parental mediation: The effect of family communication on children’s perception of television reality and negative viewing effects. Asian Journal of Communication, 20, 389–403. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, Huesmann LR, Johnson JD, Linz D, & Wartella E. (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(3), 81–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, & Bushman BJ (2001). Effects of violent videogames on aggressive behavior, aggressive cognition, aggressive affect, physiological arousal, and prosocial behavior: A meta‐analytic review of the scientific literature. Psychological Science, 12(5), 353–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, & Bushman BJ (2002). Violent videogames and hostile expectations: A test of the general aggression model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1679–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Sakamoto A, Gentile DA, Ihori N, Shibuya A, Yukawa S, … Kobayashi K. (2008). Longitudinal effects of violent videogames aggression in Japan and the United States. Pediatrics, 122, 1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CA, Shibuya A, Ihori N, Swing EL, Bushman BJ, Sakamoto A, … Saleem M. (2010). Violent videogame effects on aggression, empathy, and prosocial behavior in Eastern and Western countries: A meta‐analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 151–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice‐Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1994). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In Bryant J, & Zillma D. (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 61–90). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Benrazavi R, Teimouri M, & Griffiths MD (2015). Utility of parental mediation model on youth’s problematic online gaming. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 13(6), 712–727. [Google Scholar]

- Brambor T, Clark WR, & Golder M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82. 10.1093/pan/mpi014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulck J, & van den Bergh B. (2000). The influence of perceived parental guidance patterns on children’s media use: Gender differences and media displacement. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 44(3), 329–348. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne S, & Lee T. (2011). Toward predicting youth resistance to Internet risk prevention strategies. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55(1), 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carnagey NL, & Anderson CA (2005). The effects of reward and punishment in violent videogames on aggressive affect, cognition, and behavior. Psychological Science, 16(11), 882–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo H, Sim T, Liau AKF, Gentile DA, & Khoo A. (2015). Parental influences on pathological symptoms of video‐gaming among children and adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(5), 1429–1441. [Google Scholar]

- Clark LS (2011). Parental mediation theory for the digital age. Communication Theory, 21(4), 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Collier KM, Coyne SM, Rasmussen EE, Hawkins AJ, Padilla-Walker LM, Erickson SE, & Memmott‐Elison MK (2016). Does parental mediation of media influence child outcomes? A meta-analysis on media time, aggression, substance use, and sexual behavior. Developmental Psychology, 52(5), 798–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Stoolmiller M, & Sargent JD (2012). When movies matter: Exposure to smoking in movies and changes in smoking behavior. Journal of Health Communication, 17(1), 76–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastin MS (2006). Videogame violence and the female game player: Self‐ and opponent gender effects on presence and aggressive thoughts. Human Communication Research, 32(3), 351–372. [Google Scholar]

- Elson M, & Ferguson CJ (2014). Twenty‐five years of research on violence in digital games and aggression. European Psychologist, 19(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt CR, Bartholow BD, Kerr GT, & Bushman BJ (2011). This is your brain on violent videogames: Neural desensitization to violence predicts increased aggression following violent videogame exposure. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(5), 1033–1036. [Google Scholar]

- “ESRB Ratings Guide”. (2014). New York, NY: Entertainment Rating Software Board. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ, Olson CK, Kutner LA, & Warner DE (2014). Violent videogames, catharsis seeking, bullying, and delinquency. Crime & Delinquency, 60(5), 764–784. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P, Kasenmuller A, & Greitemeyer T. (2010). Media violence and the self: The impact of personalized gaming characters in aggressive videogames on aggressive behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Gottfredson NC, Reyes HLMN, Chen MS, David-Ferdon C, Latzman NE, … Ennett ST (2016). Developmental outcomes of using physical violence against dates and peers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(6), 665–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka Y, & Austin EW (2002). The relationship of family communication patterns to parental mediation styles. Communication Research, 29(6), 642–665. [Google Scholar]

- Funk JB, Baldacci HB, Pasold T, & Baumgardner J. (2004). Violence exposure in real‐life, videogames, television, movies, and the Internet: Is there desensitization? Journal of Adolescence, 27(1), 23–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, & Bushman BJ (2012). Reassessing media violence effects using a risk and resilience approach to understanding aggression. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(3), 138–151. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Lynch PJ, Linder JR, & Walsh DA (2004). The effects of violent videogame habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors, and school performance. Journal of Adolescence, 27(1), 5–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, Nathanson AI, Rasmussen EE, Reimer RA, & Walsh DA (2012). Do you see what I see? Parent and child reports of parental monitoring of media. Family Relations, 61(3), 470–487. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile DA, & Walsh DA (2002). A normative study of family media habits. Applied Developmental Psychology, 23(2), 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gorski JD, & Pilotto L. (1993). Interpersonal violence among youth: A challenge for school personnel. Educational Psychology Review, 5(1), 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Haninger K, & Thompson K. (2004). Content and ratings of teen‐rated videogames. Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(7), 856–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T, Krakowiak KM, & Tsay‐Vogel M. (2014). How violent videogames communicate violence: A literature review and content analysis of moral disengagement factors. Communication Monographs, 81(3), 310–332. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann T, & Vorderer P. (2010). It’s okay to shoot a character: Moral disengagement in violent videogames. Journal of Communication, 60(1), 94–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG, Brunelle TJ, Prescott AT, & Sargent JD (2014). A longitudinal study of risk‐glorifying videogames and behavioral deviance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(2), 300–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull JG, Draghici AM, & Sargent JD (2012). A longitudinal study of risk‐glorifying videogames and reckless driving. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(4), 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Konijn EA, Nije Bijvank M, & Bushman BJ (2007). I wish I were a warrior: The role of wishful identification in the effects of violent video games on aggression in adolescent boys. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S‐J, & Chae Y‐G (2007). Children’s Internet use in a family context: Influence on family relationships and parental mediation. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 10(5), 640–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linebarger DL (2015). Contextualizing videogame play: The moderating effects of cumulative risk and parenting styles on the relations among videogame exposure and problem behaviors. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 4(4), 375–396. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone S, & Helsper EJ (2008). Parental mediation of children’s Internet use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 52(4), 581–599. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan R, & Hagan J. (2004). Violence in the transition to adulthood: Adolescent victimization, education, and socioeconomic attainment in later life. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 14(2), 127–158. [Google Scholar]

- Martins N, Matthews NL, & Ratan RA (2017). Playing by the rules: Parental mediation of videogame play. Journal of Family Issues, 38(9), 1215–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MK (2010). Exploring the relationship between videogame ratings implementation and changes in game content as represented by game magazines. Politics & Policy, 38(4), 705–735. [Google Scholar]

- Musu L, Zhang A, Wang K, Zhang J, & Oudekerk BA (2019). Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2018. Washington, DC:National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI (1999). Identifying and explaining the relationship between parental mediation and children’s aggression. Communication Research, 26(2), 124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson AI (2002). The unintended effects of parental mediation of television on adolescents. Media Psychology, 4(3), 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Nikken P, & Jansz J. (2006). Parental mediation of children’s videogame playing: A comparison of the reports by parents and children. Learning, Media and Technology, 31(2), 181–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nikken P, & Jansz J. (2007). Playing restricted videogames: Relations with game ratings and parental mediation. Journal of Children and Media, 1(3), 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Nikken P, Jansz J, & Schouwstra S. (2007). Parents’ interest in videogame ratings and content descriptors in relation to game mediation. European Journal of Communication, 22(3), 315–336. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla‐Walker LM, Coyne SM, & Collier KM (2016). Longitudinal relations between parental media monitoring and adolescent aggression, prosocial behavior, and externalizing problems. Journal of Adolescence, 46, 86–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero AA (2011). Violence, schools, and dropping out: Racial and ethnic disparities in the educational consequence of student victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(18), 3753–3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi‐Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, TitusErnstoff LT, Carusi CP, … Dalton MA (2005). Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics, 116(5), 1183–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage J, & Yancey C. (2008). The effects of media violence exposure on criminal aggression. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(6), 772–791. [Google Scholar]

- Schaan VK, & Melzer A. (2015). Parental mediation of children’s television and videogame use in Germany: Active and embedded in family processes. Journal of Children and Media, 9(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shin W, & Huh J. (2011). Parental mediation of teenagers’ videogame playing: Antecedents and consequences. New Media & Society, 13(6), 945–962. [Google Scholar]

- Smith LJ, Gradisar M, & King DL (2015). Parental influences on adolescent videogame play: A study of accessibility, rules, limit setting, monitoring, and cybersafety. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 18(5), 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Lachlan K, & Tamborini R. (2003). Popular videogames: Quantifying the presentation of violence and its context. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 47(1), 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Krcmar M, Peeters AL, & Marseille NM (1999). Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “instructive mediation”, “restrictive mediation”, and “social coviewing”. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 43(1), 52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, & Peter J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh AD, Laczniak RN, & Carlson L. (1998). Mothers’ preferences for regulating children’s television. The Journal of Advertising, 27(3), 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Warner BS, Weist MD, & Krulak A. (1999). Risk factors for school violence. Urban Education, 34(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Warren R. (2001). In words and deeds: Parental involvement and mediation of children’s television viewing. Journal of Family Communication, 1(4), 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby T, Adachi PC, & Good M. (2012). A longitudinal study of the association between violent videogame play and aggression among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48(4), 1044–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]