ABSTRACT

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences are stressful for many children and their families. Previous research with school-aged children has shown that negative thoughts and worries can predict mental health symptoms following stressful events. So far preschool children have been neglected in these investigations.

Objective: The aim of this study was to explore negative thoughts and worries that preschool aged children are having during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method: As part of a larger mixed-method study, caregivers of N = 399 preschoolers aged between 3 and 5 years (M = 4.41) answered open-ended questions about their COVID-19 related thoughts and worries. Reflexive thematic analysis was used to identify relevant themes from the qualitative data. A theoretical model of child thoughts and worries was developed based on these qualitative findings and the existing empirical and theoretical literature.

Results: Caregivers gave examples that indicated that preschoolers had difficulties understanding causality and overestimated the risk of COVID-19 infection. Caregivers reported that their children expressed worries about getting sick and infecting others as well as about changes in daily life becoming permanent. Caregivers observed their children’s preoccupation with COVID-19 and worries in conversations, play and drawings as well as in behavioural changes – increased arousal, cautiousness, avoidance and attachment-seeking behaviour.

Conclusion: Preschool children can and do express negative thoughts and worries and have also experienced threat and increased vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic. A theoretical model is proposed that could inform assessments, interventions and future research in the field.

KEYWORDS: Preschool, COVID-19, worries, negative thoughts, qualitative

HIGHLIGHTS

In the COVID-19 Unmasked study, caregivers reported that preschoolers struggled to understand the current restrictions.

Preschoolers were worried of getting the virus and that changes might become permanent.

Caregivers reported increased child avoidance, arousal and clinginess.

Abstract

Antecedentes: la pandemia de COVID-19 y sus consecuencias son estresantes para muchos niños y sus familias. Investigaciones previas con niños en edad escolar han demostrado que los pensamientos negativos y las preocupaciones pueden predecir síntomas de salud mental luego de eventos estresantes. Hasta ahora, los niños en edad preescolar han sido desatendidos en estas investigaciones.

Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar los pensamientos negativos y las preocupaciones que los niños en edad preescolar están teniendo durante la pandemia de COVID-19.

Método: Como parte de un estudio más amplio de métodos mixtos, los cuidadores de N = 399 niños en edad preescolar de entre 3 y 5 años (M = 4,41) respondieron preguntas abiertas sobre sus pensamientos y preocupaciones relacionados con COVID-19. Se utilizó un análisis temático reflexivo para identificar temas relevantes a partir de los datos cualitativos. Se desarrolló un modelo teórico de los pensamientos y preocupaciones de los niños, basado en estos hallazgos cualitativos como también la literatura empírica y teórica existente.

Resultados: Los cuidadores dieron ejemplos que indicaban que los niños en edad preescolar tenían dificultades para comprender causalidad, y sobrestimaban el riesgo de infección por COVID-19. Los cuidadores informaron que sus hijos expresaron preocupación por enfermarse e infectar a otros, así como también que los cambios en la vida diaria se vuelvan permanentes. Los cuidadores observaron la preocupación de sus hijos por el COVID-19 en conversaciones, juegos y dibujos, así como también en cambios de conducta: aumento de la alerta, cautela, evitación y comportamientos de búsqueda de apego.

Conclusión: Los niños en edad preescolar pueden y logran expresar pensamientos y preocupaciones negativos, y también han experimentado amenaza y una mayor vulnerabilidad durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Se propone un modelo teórico que podría sustentar evaluaciones, intervenciones e investigaciones futuras en esta área.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Preescolares, COVID-19, preocupaciones, pensamientos negativos, cualitativo

Abstract

背景: COVID-19疫情及其后果对许多儿童及其家庭造成压力。先前对学龄儿童的研究表明, 消极想法和担忧可以预测压力事件后的心理健康症状。迄今为止, 学龄前儿童在这些调查中被忽略了。

目的: 本研究旨在探讨COVID-19疫情期间学龄前儿童所具有的消极想法和担忧。

方法: 作为一项更大型混合方法研究的一部分, N = 399名3至5岁 (M = 4.41) 的学龄前儿童的保姆回答了其COVID-19相关想法和担忧的开放性问题。自反主题分析用于从定性数据中识别相关主题。基于这些定性发现以及现有经验和理论文献, 建立了一个儿童想法和担忧的理论模型。

结果: 照顾者举的例子表明, 学龄前儿童难以理解因果关系, 并高估了COVID-19的感染风险。照顾者报告了他们的孩子对生病和感染他人以及日常生活的改变的担忧变成了永久性的。照顾者观察到他们的孩子沉迷于COVID-19, 并在对话, 玩耍和绘画以及行为改变方面感到担忧–提高了唤起, 谨慎, 回避和寻求依恋行为。

结论: 学龄前儿童可以并且确实表达消极想法和担忧, 并且在COVID-19疫情期间也体验到了威胁并提高的脆弱性。提出了一种理论模型, 可以为该领域的评估, 干预和未来研究提供参考。

关键词: 学龄前, COVID-19, 担忧, 消极想法, 定性

The COVID-19 pandemic and related consequences such as lockdown, isolation and disruption in childcare services and schooling have impacted the lives of children and their families all around the globe. Emerging empirical data from the first year of the pandemic suggest that there might be a negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child mental health and wellbeing, including elevated levels of anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms (e.g. Duan et al., 2020; Oosterhoff, Palmer, Wilson, & Shook, 2020; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021; Saurabh & Ranjan, 2020; Schmidt, Barblan, Lory & Landolt, 2021). Cognitive processing of stressful events, including the capacity to understand what is happening, anxious thoughts and a dysfunctional interpretation of one’s own reaction, may explain the development of these symptoms (e.g. Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Preschool aged children (3–5 years) can be vulnerable to the impact of stressful events, among other reasons because of their developing cognitive capacities and their dependence on the caregivers to help them understand and process stressful events (De Young & Landolt, 2018; Salmon & Bryant, 2002). For example, preschoolers’ understanding often relies on magical thinking and on the information and emotional cues from their caregivers (Dalton, Rapa, Stein, & Health, 2020). On the other hand, preschoolers might be protected by their lack of knowledge and understanding about the short and long-term consequences related to the pandemic. In this study, we focus on how preschoolers understand the COVID-19 pandemic, what they think and worry about and how they express this verbally or behaviourally.

1.1. Negative thoughts, worries and mental health problems

Cognitive models include negative thoughts and worries to explain the development and maintenance of mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress following negative or traumatic events. For example, the negative interpretation of ambiguous events and an increased attention to threat are hypothesized to be key factors for the development of anxiety (e.g. Mathews & Mackintosh, 1998). Worries can also elevate the anticipation of threat and maintain anxiety (Borkovec, 1985). Ehlers and Clark (2000) suggested that negative appraisals of a traumatic event and its sequalae lead to a sense of permanent threat even in the absence of actual threat and cause symptoms such as increased arousal and avoidance. Negative appraisals in children and adolescents include cognitions about one’s own vulnerability and about changes being permanent (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019, 2009).

Although these models and theoretical considerations were first introduced to explain symptoms in adults, the associations between negative thoughts and worries and mental health problems have also been confirmed in meta-analyses including children and adolescents (Gómez de La Cuesta, Schweizer, Diehle, Young, & Meiser-Stedman, 2019; Hu, Zhang, & Yang, 2015; Mitchell, Brennan, Curran, Hanna, & Dyer, 2017; Stuijfzand, Creswell, Field, Pearcey, & Dodd, 2018). However, the role of thoughts and worries in preschooler’s mental health is almost unknown. There is some evidence from the domestic violence and anxiety literature that child negative thoughts about an ambiguous or negative event are associated with child mental health symptoms (Ablow, Measelle, Cowan, & Cowan, 2009; Creswell, Shildrick, & Field, 2011). However, previous research was either conducted in the absence of a stressful event or in the context of very specific experience (e.g. domestic violence) and cannot be generalized to the current COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Negative thoughts and worries during COVID-19

In the context of COVID-19, low levels of awareness of and negative thoughts about the virus have found to be related to higher levels of depression and anxiety among 12- to 18-year-olds (Zhou et al. (2020). Initial reports of the Co-SPACE survey with 4- to 18-year-old children and adolescents in different countries such as the UK, Iran and Ireland indicated that most children perceive the COVID-19 pandemic as a serious issue. Caregivers reported that their children were most frequently worried that they or their family and friends could catch the virus and that they were missing school (Connor, Gallagher, Walsh, & McMahon, 2020; Rajabi, 2020; Waite, Patalay, Moltrecht, McElroy, & Creswell, 2020). Another study investigated the understanding and representations of COVID-19 in 3- to 12-year-old children (Idoiaga Mondragon, Berasategi, Eiguren, & Picaza, 2020). The study found that children saw the virus as an enemy. Children experienced fears and worries particularly related to the risk of transmitting the virus to their grandparents. Furthermore, children reported conflicting emotional states – fear, nervousness and loneliness on the one hand, and safety and happiness on the other (Idoiaga Mondragon, Berasategi, et al., 2020; Idoiaga Mondragon, Sancho, Santamaria, & Munitis, 2020). The authors acknowledged that the study might have missed variations in different age groups because of the relatively wide age range involved (Idoiaga Mondragon, Berasategi, et al., 2020).

1.3. The current study

The current study aims to explore preschool children’s understanding, negative thoughts and worries about the COVID-19 pandemic from the perspective of their caregivers. We took a qualitative approach to gather information specific for this developmental stage that might be overlooked by previous cognitive processing models developed for adults and adapted for school-aged children and adolescents. The qualitative results were used to build on existing theories and findings and develop a preschool specific model of the pandemic-related cognitive processes and their behavioural expression.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure

This research is part of a prospective longitudinal mixed-methods study on young children’s wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study procedure involved an online survey and was approved by the Human Research Committee of the Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service (HREC/20/QCHQ/63632) and registered by the University of Melbourne Medicine and Dentistry HESC (ID 2057001). We recruited a convenience sample using the team’s existing programmes and partnerships within Australia as well as advertisement through newspapers, research recruitment sites, social media channels, and organizations (e.g. early childcare centres, GP surgeries, child health services, parenting groups). The first data collection for Survey 1 took place between May and July 2021 during the easing of the first lockdown restrictions in Australia (daily new cases between 23 and 306; 10 732 cumulative new cases by the end of the first data collection; Department of Health, 2020). Caregivers are followed up at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months. In this nested mixed-methods study, the qualitative paradigm was embedded within the quantitative main design to gain better understanding of child thoughts and worries during the pandemic. Here we only focus on the qualitative data from Survey 1 (De Young et al., 2020) and included caregivers who answered the voluntary open-ended questions about child negative thoughts and worries. These open-ended questions followed a series of 17 quantitative items on child confusion, worries and negative thoughts. In order to be able to focus on presenting the rich qualitative data in detail, the quantitative results will be presented elsewhere.

2.2. Participants

Participants were caregivers of young children (aged 1–5 years) who were able to complete the online survey in English. In total, N = 998 caregivers participated in the first wave of data collection. Mothers, caregivers with higher education and families living in metropolitan areas were overrepresented in this sample. We assessed data on child cognitive processes only for 3- to 5-year-old children. Thus, the open-ended questions about child worries and thoughts were shown only to caregivers with children between 3 and 5 years of age. Within the subsample of caregivers of 3- to 5-year-old children (n = 614), we compared quantitative data for caregivers who did (N = 399) and caregivers who did not answer the optional open-ended questions about child negative thoughts and worries (n = 215). Caregivers who answered the open-ended questions had slightly older children (t = −3.68, df = 612, p < .001) and reported more negative COVID-19 related experiences which were assessed using an index based on a Likert scale with 15 questions (e.g. financial hardship, change in routine, social isolation, etc.; t = −2.86, df = 589, p = .004). There were no differences in participating caregivers’ gender, child gender or whether there was suspected or substantiated COVID-19 diagnosis of the child, caregiver or other family member (all p > .05).

The qualitative data of N = 399 children between 3 and 5 years (M = 4.41 years, SD = 0.82; 51.6% female) were included in this analysis. Seven children (1.8%) identified as Aboriginal or Torres Islander. Between 2% and 5% of caregivers reported that their children had a diagnosed emotional or mental health difficulty, neurodevelopmental disorder or sleep disorder prior to the pandemic. There were 2.3% children with sensory disability and 6.8% children with a chronic health condition. Most participating caregivers were females (96.2%) and the biological parent of the child (98.0%). Caregivers’ mean age was M = 36.39 years (SD = 5.99). Twenty children (5.0%) and 44 caregivers (11.0%) were tested for COVID-19 and had negative results. One parent had a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis.

2.3. Open-ended questions

Caregivers answered the following three open-ended questions: ‘How do you know your child is worried about these things? What have they done to show you this?’; ‘Can you write any examples of COVID-19 related thoughts or worries your child has talked about or showed in play or drawings?’ This resulted in 15 927 words written by the caregivers.

2.4. Analysis

The qualitative analysis followed the six steps of reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). After familiarization with the answers (Step 1), the first author coded data manually going through every single answer (Step 2). Segments were coded based on commonalities found between or within subjects, similarities with previous findings in the literature, if consistent with other theories and/or if they were unexpected. This resulted in 602 codes which were analysed together in Step 3, irrespective of the initial questions. Common themes and subthemes were generated by the first author, and data were collated to each candidate theme or subtheme (Step 3). The approach was inductive, so that the codes and themes were directed by the content of the data. We chose semantic codes and themes that reflect the data and assumed that the data created certain reality (critical realist way). The candidate themes developed by the first author were then reviewed by the author team (Step 4), named (Step 5) and included in the analytical narrative report and theoretical model (Step 6). The broader team discussed, revised and modified the themes. The broader team had access to the codes as well but did not edit them. In line with the approach described by Braun and Clarke (2006), the last step goes beyond a description of the themes and includes a suggestion of how the themes are related to each other. As the analysis follows an inductive approach, the themes, generated from the empirical data, were included in a theoretical model, building on the literature known to the research team while doing the analysis. In particular, the cognitive model of Ehlers and Clark (2000) and previous findings about older children’s cognitions (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019, 2009) as well as preschoolers’ dependence on their caregiver in the context of stressful events (Salmon & Bryant, 2002), were considered when developing the eventual model.

3. Results

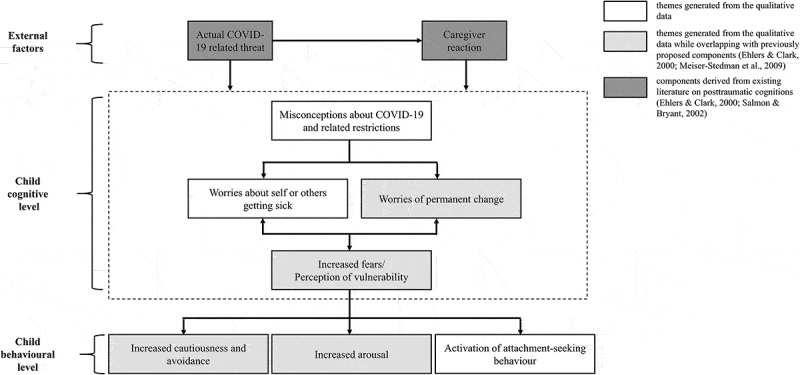

Based on the developed themes for preschoolers and incorporating knowledge from previous research on dysfunctional cognitive processing styles (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019, 2009) as well as preschoolers’ cognitive processing of stressful events (Salmon & Bryant, 2002), we propose a theoretical model explaining preschool children’s negative thoughts and worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). We used the framework of the previous cognitive model (Ehlers & Clark, 2000) and findings about school-aged children (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019) to explain how themes might be related to each other. Based on the common themes in the caregivers’ answers, preschoolers’ thoughts and worries could be expressed on the cognitive and behavioural levels. On the cognitive level, children’s misconception about the virus and/or the associated restrictions may lead to an overestimation of the risk of getting sick (e.g. one will always get sick when going out) and subsequently increase worries about themselves or loved ones getting sick. Furthermore, children verbally expressed worries that things will never be normal again (worries of permanent change) which might be also related to their limited knowledge and ability to predict the consequences of the pandemic. Children’s worries could be associated with increased fears and the perception of vulnerability. On the behavioural level, children expressed their anxiety with increased arousal and might control their anxiety and perception of vulnerability by being more cautious, avoiding potential risks and seeking safety and support from their caregivers by activating attachment-seeking behaviours. We propose that child worries and perceived vulnerability on the cognitive level affect child behaviour.

Figure 1.

Cognitive and behavioural expression of COVID-19 related negative thoughts and worries in preschool children. Note. The direction of the associations is derived from existing literature on post-traumatic cognitions (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019)

Another level of external factors, which were not based on the current qualitative analysis, was added to the model to acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic constitutes an actual health threat (Javakhishvili et al., 2020) and that caregivers influence their children’s cognitive processing of stressful events through their own reactions (Salmon & Bryant, 2002). During high levels of actual threat, some thoughts and behaviours (e.g. increased cautiousness) may actually be adaptive or protective for the child’s physical and mental health (e.g. social distancing to stop them catching or spreading the virus). However, in the absence of actual threat, persisting high levels of worries and perceived vulnerability are expected to be maladaptive (Ehlers & Clark, 2000). Hence, the proposed external factor, actual threat, can be seen as a moderator differentiating between adaptive and maladaptive reactions. Furthermore, parents own reactions during the pandemic might directly (e.g. through verbal interpretation cues, model learning) or indirectly (e.g. through increased stress and preoccupation) affect child cognitive processing (Salmon & Bryant, 2002).

In the following, we present details about the different themes on the cognitive and behavioural level in the model that were derived from the qualitative data including examples of parents’ report.

3.1. Cognitive level

3.1.1. Misconception of causality

Preschool children struggled to understand and accept why restrictions were in place such as loss of freedom and not being able to see grandparents and friends. Caregivers also reported limitations in their child’s understanding of causality in the context of the virus. Typical misconceptions reported included beliefs that people will always get sick if they do not adhere to the restrictions, beliefs that not feeling well meant that the child had COVID-19, or beliefs that people will always die if they get sick from the virus. Preschoolers had difficulties understanding the concepts of risk and how risk changes depending on the conditions and context (examples are presented in Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of negative thoughts and worries about COVID-19

| Theme | Example | Child gender, age |

|---|---|---|

| Misconceptions of causality | ‘My child goes through stages of appearing to understand … She has been angry and confused and has struggled to make sense of it … One day she appears to understand but then other days like today she kept saying she wanted to go to the play centre. It’s such a huge thing to understand for a 3 year old … ’ | Girl, 3 years old |

| ‘Everyone going out will get the virus. People going out are all naughty and the police will need to get them.’ | Girl, 4 years old | |

| ‘Grandpa came into house once during restrictions, just in backyard to look at a picture we had drawn. Child told grandpa he had to leave and started crying thinking grandpa would die. But then a few days later thought I was tricking him about COVID-19 because grandpa was still alive and talking to us on the phone.’ | Boy, 4 years old | |

| ‘He says “because of the virus” to explain everything I say No to.’ | Boy, 4 years old | |

| Worries about self or others getting sick | ‘Another night she had a slight head cold and woke up with a blocked nose. When she was trying to go back to sleep, she said “I’m scared I have Coronavirus”.’ | Girl, 5 years old |

| ‘They worry about their grandparents getting sick and get sad and upset that they can’t see them, hug them etc.’ | Girl, 4 years old | |

| ‘She talks about being worried her germs will make other people sick.’ | Girl, 3 years old | |

| ‘They have openly said they don’t want to get sick’ | Boy, 5 years old | |

| Worries of permanent change | ‘More recently she had a big breakdown, when she cried and cried that ‘everything is GONE. There’s no school, no park, no friends. There’s only the shops and bushwalking, and kids can’t even go to the shops!!’ | Girl, 5 years old |

| ‘He is just worried it will be forever and he won’t get to go back to preschool or play with his friends again.’ | Boy, 4 years old | |

| ‘Concerns that things will never go back to how they were.’ | Girl, 5 years old | |

| ‘He has said that he is worried he won’t see family members who live overseas again.’ | Boy, 3 years old | |

| ‘He says this will never end and we will be stuck home forever. He’s scared he will never see his friends again’ | Boy, 4 years old | |

| Increased fears | ‘She is more timid, especially of the dark … ’ | Girl, 4 years old |

| ‘Fearful of lots more things now. The dark, nightmares, being alone.’ | Boy, 3 years old | |

| ‘Showed signs of anxiety and shutting down when asked to do different things’ | Boy, 3 years old |

3.1.2. Preschoolers’ worries

Caregivers’ answers indicated two different themes of child COVID-19 related worries – worries that the child or others can get sick and worries that changes to daily life might be permanent. Furthermore, some parents stated that they did not think their child was actually worried but rather just aware that there is a virus and restrictions related to that.

3.1.2.1. Worries about self or others getting sick from COVID-19

Caregivers reported that their preschoolers worried that they might get sick, transmit the virus to others or that loved ones might get sick. Such worries could increase child anxiety and avoidance of places and people (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019; Mitchell et al., 2017). A subtheme in children’s worries that they might get sick was related to their concerns about going back to childcare or preschool, even when the restrictions were eased (at the time of the survey) and the risk of getting the virus was becoming lower. These concerns might be connected to children’s limited understanding that risk can change. This subtheme has particular relevance for supporting children who are scared to go back to childcare after a lockdown period.

3.1.2.2. Worries of permanent change

Children expressed during conversations with their parents that they were worried that changes were permanent (e.g. that they will never be able to see their grandparents again). The perception of negative changes as permanent can lead to a sense of current threat and hopelessness (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2009).

3.1.3. Increased fears

Caregivers reported that their children became more scared of things in general (e.g. scared from the dark, scared to be alone). Increased fears could be related to the perception of vulnerability (Armfield, 2006).

3.2. Behavioural level

3.2.1. Cautiousness and avoidance

Caregivers observed increased cautiousness regarding social distancing and hygiene measures. Children showed particular behaviours (e.g. increasing hand washing or keeping distance from others) themselves or demanded others to do so. Furthermore, caregivers noticed that their children were avoiding places, activities and conversations related to COVID-19 (examples are presented in Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of behaviours related to negative thoughts and worries about COVID-19

| Subtheme | Example | Child gender, age |

|---|---|---|

| Increased cautiousness and avoidance | ‘ … she instantly just became obsessed with germs … always washing hands and displaying more physical hygiene than normal. Cleaning toys up, making sure rubbish is it the bin and overly cautious of everything.’ | Girl, 3 years old |

| ‘He mentions that he shouldn’t go near people and gets worried if he does.’ | Boy, 3 years old | |

| ‘Tells mum off when not coughing into elbow and why, then shows and demands you do it this way’ | Girl, 4 years old | |

| ‘She told us she wants to stop hearing about [COVID-19].’ | Girl, 5 years old | |

| Increased arousal | ‘She is quicker to get upset or angry at small inconveniences and has been having night terrors more frequently.’ | Girl, 3 years old |

| ‘She has had noticeably less resilience, especially in the first few weeks of the pandemic.’ | Girl, 5 years old | |

| ‘She hasn’t been sleeping as well and is up a couple of times throughout the night. This may be because she isn’t as worn out (from going to school) but she also says she has bad dreams and can’t go back to sleep. These dreams aren’t specific or related to COVID.’ | ||

| Activation of attachment-seeking behaviour |

‘She is clingier to me and my husband, but can also push us away aggressively and hit, and not want to be touched when she is upset.’ ‘Very clingy, don’t want to let me out of their sight’ |

Girl, 3 years old Boy, 3 years old |

| ‘She has increased separation anxiety and refuses to be alone (even if a parent is in another part of the house).’ | Girl, 5 years old | |

| ‘Increased need for close physical attention, hugs, sitting on lap, etc.’ | Girl, 4 years old | |

| ‘He keeps asking if I love him/like him. He was otherwise a very confident child before COVID-19.’ | Boy, 4 years old | |

| ‘Regression in ability to toilet overnight (increased bed wetting when previously night trained’ | Boy, 4 years old |

3.2.2. Increased arousal

Children showed increased arousal following the COVID-19 outbreak including irritability, sleep disturbance, strong emotions and difficulties in regulating these emotions.

3.2.3. Activation of attachment-seeking behaviour

Some caregivers reported that their children showed attachment-seeking behaviour which is normal for young children in stressful situations (Ainsworth, 1985). Children expressed their worries about losing their caregivers and showed increased clinginess, more separation anxiety, and more need to be comforted. Some caregivers reported that their children regressed in developmental tasks they had already acquired before the pandemic (e.g. stopped using the toilet) and in this way may have required more of their caregiver’s attention.

3.3. Further themes related to the preschool age group

Some further themes emerged from parents’ reports that were not directly related to child negative thoughts and worries but show reactions to the pandemic that might be specific for this stage of development.

3.3.1. Magical thinking

An aspect of children’s understanding of how the COVID-19 virus can be fought involved magical thinking. Magical thinking refers to a child’s belief that they can change things with their thoughts or actions. Caregivers also gave examples of their child believing that superheros or authorities can physically stop the virus. While this type of thinking can give some children initial reassurance, it might be frustrating in situations when children do not see the expected change.

This week she has decided that Rona has gone away and is very frustrated that she can’t return to normal life. She has been getting mad at us when we tell her that unfortunately Rona is still here so we can’t recommence her normal routine. (girl, 3 years old)

Had also stated he will become a doctor to help get rid of the virus so he can go play again and keep people safe. (boy, 3 years old)

3.3.2. COVID-19 related drawing and play

Caregivers reported that children’s drawings and play included COVID-19 related themes. The imaginary play ranged from re-enacting social isolation, playing doctor roles and pretend play where toys and people die because of the virus. Children’s play and drawings did not always have negative content and might not be an indicator for children’s worries. However, they show children’s preoccupation with COVID-19 related changes and risks. Furthermore, play can be an important way for children to cope with stress and process what is happening around them. Play could also be a way that young children feel they can have some control.

He has been building houses out of LEGO and saying that Mum, Dad, himself and his brother are in the house but no one else is allowed to come in cause of the virus. (boy, 4 years old)

Everything she draws (animals, buildings etc) she puts germs in them. She says I’m giving them the germ or I’m making them have the germ. (girl, 3 years old)

3.3.3. Being upset about missing out

Parents also reported their children had been upset about missing out on activities (e.g. seeing friends and grandparents, going to the park, etc.). Although this may be stressful to children, it was not classified as worry in this analysis.

He wants to go to the playground and visit cousins, which we always normally do. He’s annoyed and upset that we can’t. (boy, 5 years old)

3.3.4. General death talk

Some children showed increased interest in death related topics not specifically related to COVID-19. General death talk might indicate children processing of the current threat and health risks or trying to understand terms they haven’t heard about previously (Panagiotaki, Hopkins, Nobes, Ward, & Griffiths, 2018).

Talking about death more and asking about my work and looking after sick patients and what happens if they die. (girl, 4 years old)

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore negative thoughts and worries of preschool children that might cause mental health symptoms. Caregivers were asked via open-ended questions in an online survey if their preschool-aged child (3–5 years) had expressed thoughts or worries related to the COVID-19 pandemic in conversations or through their behaviour. Drawing on the current qualitative findings as well as empirical and theoretical literature (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019, 2009; Salmon & Bryant, 2002), a theoretical model (Figure 1) to describe cognitive processing of stressful events in preschool children was proposed. The model includes child cognitions (misconceptions, worries, fears and perceived vulnerability) and behaviours (increased cautiousness and avoidance, arousal and attachment-seeking behaviour) as well as external factors (actual COVID-19 related threat and caregivers’ reaction).

The qualitative data supported similar cognitions that were presented in the cognitive model of posttraumatic stress in adults (Ehlers & Clark, 2000) and in the literature about school-aged children’s cognitive processing (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2019, 2009) – overestimating the risk for the traumatic experience to happen again and worries that changes are permanent can lead to the perception of vulnerability and increased arousal and avoidance. The mechanisms of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on preschool children seem to have similarities to cognitive and behavioural response following traumatic events (De Young & Landolt, 2018). Our model considers factors specific for the developmental stage of preschoolers. First, due to their developing cognitive capacities, preschoolers are more likely to have misconceptions of causality, of risk and of how risk can change. Second, preschoolers showed increased attachment-seeking behaviour which is related to child dependence on caregivers to regulate emotions (e.g. Bechtel-Kuehne, Strodthoff, & Pauen, 2016). Third, the model includes the external impact of caregivers which has been considered important in the development and maintenance of stress-related cognitive processing styles and symptoms (De Young & Landolt, 2018; Salmon & Bryant, 2002). The proposed model gives a framework for cognitive and behavioural preventions and interventions for young children and can guide future research on cognitive processing of stressful, disruptive or traumatic experiences of preschool children. For example, prevention efforts can focus on teaching and supporting caregivers and educators to help children understand and process what is happening and to clarify any misunderstandings or worries. Some parents try to protect their children from negative information but overprotection might have negative effect on child wellbeing by promoting fear and avoidance (Williamson et al., 2017). Regular child-appropriate conversations, and using developmentally appropriate materials (e.g. therapeutic storybooks, animations) can help children understand the situation and form accurate estimates of the current risks.

The current findings on child thoughts about the COVID-19 pandemic are consistent with the previous study on representations of the COVID-19 in 3- to 12-year-old children in Spain (Idoiaga Mondragon, Berasategi, et al., 2020). Children in the previous study reported that they did not know what the virus was exactly, but they knew it was an enemy. Furthermore, they were worried about getting sick and infecting older people (Idoiaga Mondragon, Berasategi, et al., 2020). In the current study, caregivers also observed that children had misconceptions about the virus and overestimated the risk of infection. However, the themes that emerged from the current qualitative data include further components that were not reported when using child report (e.g. attachment-seeking behaviour). This might be due to different research questions and age range in both studies but could also be due to the reliance on caregiver proxy-report in this study. Caregivers awareness and interpretation of their child’s cognitive and behavioural expressions may be influenced by their own knowledge, worries and level of reflective functioning.

Comparisons between the current with the previous study by Idoiaga Mondragon et al. (2020) might help understand child thoughts and worries in contexts with different levels of current threat. When data collection in each study took place, there were social distancing measures in both countries with Spain having higher COVID-19 incidence rates and very strict restrictions including complete lockdown while in Australia restrictions were easing and numbers of new daily cases were much lower. Even though the objective level of threat to COVID-19 exposure has been different between countries, young children in both countries still appear to have similar worries.

The qualitative results showed that caregivers noticed that their preschool children perceived a threat and increased vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic and expressed this through behaviours such as being more cautious, avoiding things, places and conversations, and showing attachment-seeking behaviours. It remains unclear if child thoughts and worries reported by the parents and their behaviours were pathological or a normal reaction to the pandemic, especially as these questions were asked during the early stages of the pandemic when families were coming out of their first lockdown. Child worries about getting sick and/or infecting others can be justified in the context of a pandemic. Overall, during the early stages of the pandemic in Australia it has been important and adaptive to have good hand hygiene, be cautious and physically distance from people outside the family. Attachment-seeking behaviour towards the primary caregiver is also a normal reaction of securely attached children in stressful situations (Ainsworth, 1985).

However, our findings suggest that young children might overestimate the risk for transmission of the COVID-19 virus due to misconceptions of causality. For example, some children thought that they would get sick if they go out on the streets instead of estimating the more complex conditional risk that they might get sick if they go out on the streets and if they have close contact to an infected person. Worries that changes are permanent have also been found in previous trauma-focused research with older children and adolescents and have been described as dysfunctional cognitions that are associated with mental health symptoms in the long-term (Gómez de La Cuesta et al., 2019; Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2009; Mitchell et al., 2017). The emotional and behavioural expressions of child worries that were found in the current study included increased anxiety, arousal, avoidance, clinginess and regression of already acquired tasks which have been also observed as reactions in preschool children who experienced other stressful or traumatic events such as a serious injury, natural disaster or violence (De Young & Landolt, 2018; Scheeringa, 2003; Vasileva, Haag, Landolt, & Petermann, 2018). These reactions are normal within the early stages of a traumatic or disruptive event but might be pathological if they continue over longer periods and cause functional impairment (De Young & Landolt, 2018). Longitudinal quantitative research on the consequences of COVID-19 is necessary to estimate if and for which children the negative thoughts, worries and related behaviours continue in the absence of current threat.

There are some limitations of this study that need to be taken into consideration. Firstly, as this was a convenience sample recruited through several sources, there might be (self-) selection bias – children particularly at risk (e.g. with sick family members) might have not been included in the sample. Additionally, the open-ended questions were optional and were answered by 64% of caregivers of children between 3 and 5 years. This means that we missed the observations of one third of caregivers. Furthermore, the sample was overrepresented by mothers (96.2%). It would be ideal for future research to actively engage participation from fathers. The open-ended questions asked about child thoughts (and not specifically negative thoughts) and worries about COVID-19. This may have resulted in caregivers reporting thoughts that are not necessarily negative. An interview with the caregivers instead of online open-ended questions would have generated more in-depth qualitative data. Due to the age of the children and the nature of the pandemic, it was only possible to have one parent proxy-report via an online survey. Although we asked parents particularly about their observations, answers might still include parents’ interpretation of child thinking. Furthermore, poor child-parent agreement was found previously in trauma research (Stover, Hahn, Im, & Berkowitz, 2010). Finally, it is important to acknowledge researchers’ subjectivity in reflexive thematic analysis. In line with the reflexive thematic analysis paradigm, the first author coded the data and developed the themes, in conversation with the co-authors. While this is an important analytical resource (Braun & Clarke, 2020), the resulting synthesis is influenced by the authors’ background in the cognitive-behavioural school of thought. For this reason and because the questions were optional, we did not report percentage of children meeting each theme, which is common for other approaches (e.g. content analysis).

The findings have some important practical and research implications for the current COVID-19 pandemic but also for future work and research with preschool children who experienced stressful or traumatic events. First, it seems that young children experienced threat but struggled to understand causality and risk. Child-appropriate conversations and regular updates are necessary to support them understand the situation and related health risk. Second, the developed theoretical model can inform future research on cognitive processing of preschool children. So far, preschool children have been excluded from research on cognitive processing following stressful or traumatic events. Our findings based on caregiver report indicate that preschool children can also develop negative thoughts and worries in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research needs to directly ask preschool aged children about their worries and validate the proposed model that is based on caregiver-only observations. Furthermore, studies could focus on including appropriate quantitative measures to assess negative thoughts and worries in the preschool age following traumatic or disruptive events and to investigate their long-term impact on child wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participating families. We appreciate the engagement and help of all colleagues who were involved and supported this project. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as Australia’s First People and Traditional Custodians and pay our respect to their Elders past, present and emerging.

Funding Statement

The postdoc fellowship of Mira Vasileva is funded by the German Research Foundation (Research Fellowship #420503242). Eva Alisic is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT190100255).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MV]. Following the completion of data collection and the publication of the results related to the primary study aims, the data will be made publicly available via PACT/R. The qualitative data will be not publicly available due to information that may compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Ablow, J. C., Measelle, J. R., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2009). Linking marital conflict and children’s adjustment: The role of young children’s perceptions. Journal of Family Psychology, 23(4), 485–11. doi: 10.1037/a0015894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M. D. (1985). Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 61(9), 771–791. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armfield, J. M. (2006). Cognitive vulnerability: A model of the etiology of fear. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(6), 746–768. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel-Kuehne, S., Strodthoff, C. A., & Pauen, S. (2016). Co-and self-regulation in the caregiver-child dyad: Parental expectations, children’s compliance, and parental practices during early years. Journal of Self-regulation and Regulation, 2, 33–56. doi: 10.11588/josar.2016.2.34352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borkovec, T. D. (1985). Worry: A potentially valuable concept. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 23(4), 481–482. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(85)90178-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–25. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI]

- Connor, C. O., Gallagher, E., Walsh, E., & McMahon, J. (2020). Co-SPACE Irland Report 02: COVID-19 worries, parent/carer stress and support needs, by child special educational needs and parent/carer work status. Retrieved from http://cospaceoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Cospace-2nd-Report-30th-June-Final.pdf

- Creswell, C., Shildrick, S., & Field, A. P. (2011). Interpretation of ambiguity in children: A prospective study of associations with anxiety and parental interpretations. Journal of Child Family Studies, 20(2), 240–250. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9390-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, L., Rapa, E., Stein, A. J. T. L. C., & Health, A. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID-19. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 346–347. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Young, A. C., & Landolt, M. A. (2018). PTSD in children below the age of 6 years. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(11). doi: 10.1007/s11920-018-0966-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Young, A. C., Paterson, R., March, S., Hoehn, E., Alisic, E., Cobham, V., Donovan, C., Middeldorp, Ch., Gash, T., & Vasileva, M. (2020). Report 1: Early findings & recommendations from COVID-19 unmasked young child survey 1. Brisbane: Queensland Centre for Perinatal & Infant Mental Health, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) current situation and case numbers. Retrieved from https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert

- Duan, L., Shao, X. J., Wang, Y., Huang, Y. L., Miao, J. X., Yang, X. P., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319–345. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez de La Cuesta, G., Schweizer, S., Diehle, J., Young, J., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2019). The relationship between maladaptive appraisals and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1620084. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1620084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Yang, Z. (2015). The relationship between attributional style for negative outcomes and depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(4), 304–321. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2015.34.4.304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Berasategi, N., Eiguren, A., & Picaza, M. (2020). Exploring children’s social and emotional representations of the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Sancho, N. B., Santamaria, M. D., & Munitis, A. E. (2020). Struggling to breathe: A qualitative study of children’s wellbeing during lockdown in Spain. Psychology & Health. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2020.1804570 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Javakhishvili, J. D., Ardino, V., Bragesjö, M., Kazlauskas, E., Olff, M., & Schäfer, I. (2020). Trauma-informed responses in addressing public mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Position paper of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1780782. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1780782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, A., & Mackintosh, B. (1998). A cognitive model of selective processing in anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22(6), 539–560. doi: 10.1023/A:1018738019346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser‐Stedman, R., McKinnon, A., Dixon, C., Boyle, A., Smith, P., Dalgleish, T. J. (2019). A core role for cognitive processes in the acute onset and maintenance of post‐traumatic stress in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 60(8), 875–884. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser‐Stedman, R., Smith, P., Bryant, R., Salmon, K., Yule, W., Dalgleish, T., & Nixon, R. D. V. (2009). Development and validation of the child post-traumatic cognitions inventory (CPTCI). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(4), 432–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R., Brennan, K., Curran, D., Hanna, D., & Dyer, K. F. (2017). A meta‐analysis of the association between appraisals of trauma and posttraumatic stress in children and adolescents. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(1), 88–93. doi: 10.1002/jts.22157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhoff, B., Palmer, C. A., Wilson, J., & Shook, N. (2020). Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with mental and social health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67, 179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotaki, G., Hopkins, M., Nobes, G., Ward, E., & Griffiths, D. (2018). Children’s and adults’ understanding of death: Cognitive, parental, and experiential influences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 96–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajabi, M. (2020). Co-Space Iran Report 01: Covid-19 worries, parent/carer stress and support needs, by child special educational needs and parent/carer work status. Retrieved from http://cospaceoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Co-SPACE-Iran-Report-1.pdf

- Ravens-Sieberer, U., Kaman, A., Erhart, M., Devine, J., Schlack, R., & Otto, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Salmon, K., & Bryant, R. A. (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder in children: The influence of developmental factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(2), 163–188. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00086-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saurabh, K., & Ranjan, S. (2020). Compliance and psychological impact of quarantine in children and adolescents due to Covid-19 pandemic. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 87, 532–536. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03347-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheeringa, M. S. (2003). Research diagnostic criteria for infants and preschool children: The process and empirical support. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(12), 1504–1512. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200312000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, S. J., Barblan, L. P., Lory, I., & Landolt, M. A. (2021). Age-related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1901407.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover, C. S., Hahn, H., Im, J. J., & Berkowitz, S. (2010). Agreement of parent and child reports of trauma exposure and symptoms in the early aftermath of a traumatic event. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2(3), 159. doi: 10.1037/a0019156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuijfzand, S., Creswell, C., Field, A. P., Pearcey, S., & Dodd, H. (2018). Research review: Is anxiety associated with negative interpretations of ambiguity in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(11), 1127–1142. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva, M., Haag, A.-C., Landolt, M., & Petermann, F. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder in very young children: Diagnostic agreement between DSM-5 and ICD-11. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31, 529–539. doi: 10.1002/jts.22314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite, P., Patalay, P., Moltrecht, B., McElroy, E., & Creswell, C. (2020). Covid-19 worries, parent/carer stress and support needs, by child special educational needs and parent/carer work status. Retrieved from http://cospaceoxford.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Co-SPACE-report-02.pdf

- Williamson, V., Creswell, C., Fearon, P., Hiller, R. M., Walker, J., & Halligan, S. L. (2017). The role of parenting behaviors in childhood post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 53, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S. J., Zhang, L. G., Wang, L. L., Guo, Z. C., Wang, J. Q., Chen, J. C., Liu, M., Chen, X., & Chen J. X. (2020). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 10. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MV]. Following the completion of data collection and the publication of the results related to the primary study aims, the data will be made publicly available via PACT/R. The qualitative data will be not publicly available due to information that may compromise the privacy of research participants.