Abstract

Aims

The effect of early administration of intravenous (IV) furosemide in the emergency department (ED) on short-term outcomes of acute heart failure (AHF) patients remains controversial, with one recent Japanese study reporting a decrease of in-hospital mortality and one Korean study reporting a lack of clinical benefit. Both studies excluded patients receiving prehospital IV furosemide and only included patients requiring hospitalization. To assess the impact on short-term outcomes of early IV furosemide administration by emergency medical services (EMS) before patient arrival to the ED.

Methods and results

In a secondary analysis of the Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments (EAHFE) registry of consecutive AHF patients admitted to Spanish EDs, patients treated with IV furosemide at the ED were classified according to whether they received IV furosemide from the EMS (FAST-FURO group) or not (CONTROL group). In-hospital all-cause mortality, 30-day all-cause mortality, and prolonged hospitalization (>10 days) were assessed. We included 12 595 patients (FAST-FURO = 683; CONTROL = 11 912): 968 died during index hospitalization [7.7%; FAST-FURO = 10.3% vs. CONTROL = 7.5%; odds ratio (OR) = 1.403, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.085–1.813; P = 0.009], 1269 died during the first 30 days (10.2%; FAST-FURO = 13.4% vs. CONTROL = 9.9%; OR = 1.403, 95% CI = 1.146–1.764; P = 0.004), and 2844 had prolonged hospitalization (22.8%; FAST-FURO = 25.8% vs. CONTROL = 22.6%; OR = 1.189, 95% CI = 0.995–1.419; P = 0.056). FAST-FURO group patients had more diabetes mellitus, ischaemic cardiomyopathy, peripheral artery disease, left ventricular systolic dysfunction, and severe decompensations, and had a better New York Heart Association class and had less atrial fibrillation. After adjusting for these significant differences, early IV furosemide resulted in no impact on short-term outcomes: OR = 1.080 (95% CI = 0.817–1.427) for in-hospital mortality, OR = 1.086 (95% CI = 0.845–1.396) for 30-day mortality, and OR = 1.095 (95% CI = 0.915–1.312) for prolonged hospitalization. Several sensitivity analyses, including analysis of 599 pairs of patients matched by propensity score, showed consistent findings.

Conclusion

Early IV furosemide during the prehospital phase was administered to the sickest patients, was not associated with changes in short-term mortality or length of hospitalization after adjustment for several confounders.

Keywords: Acute heart failure, Furosemide, Diuretics, Mortality, Outcome, Emergency department

Introduction

Fluid retention plays a central role in the pathophysiology of the signs and symptoms developed by patients with acute heart failure (AHF), with more than 90% of patients exhibiting the wet phenotype during decompensations.1,2 Accordingly, reduction of fluid overload has remained the main target of AHF treatment during decades. In current practice, intravenous (IV) loop diuretics, and especially furosemide, are the drugs most frequently used to achieve this purpose, and the latest European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines give a class I recommendation (level of evidence: B) to loop diuretics for the treatment of AHF episodes.3 Although furosemide has largely demonstrated to increase diuresis, natriuresis and weight loss, as well as ameliorate symptoms, its use has never been demonstrated to reduce mortality.4,5

Recently, two studies have explored the impact of early administration of IV furosemide on in-hospital mortality in the emergency department (ED) to patients hospitalized with AHF. Although both studies followed a similar patient inclusion strategy and used the same definition of early IV furosemide administration (within the first 60 min of patient arrival to ED), they showed contrasting results: while the Japanese study of Matsue et al.6 reported a significantly lower in-hospital mortality for patients receiving early IV furosemide, the Korean study of Park et al.7 found a lack of association between early IV furosemide administration and in-hospital mortality. Remarkably, neither study included patients receiving IV furosemide at a very early stage—i.e. during the prehospital phase, while being managed by emergency medical services (EMS). Moreover, the analysis was limited to AHF patients who were admitted to the ED and finally hospitalized, thus dismissing those directly discharged home after ED care (between 16% and 36%, depending on the country8). In order to address these limitations, we designed the FAST-FURO study aimed to evaluate the impact of very early IV furosemide administration by EMS on short-term outcomes among AHF patients that need IV furosemide treatment in the ED.

Methods

Setting

This is a secondary analysis of the Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments (EAHFE) registry. The EAHFE registry was initiated in 2007 and every 2–3 years carries out a 1- to 2-month recruitment period of all consecutive patients diagnosed with AHF in Spanish EDs participating in the project. To date, six recruitment phases (2007, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, and 2018) have been performed with the participation of 45 EDs from community and university hospitals across Spain (representing about 15% of the Spanish public healthcare system hospitals), enrolling a total of 18 370 AHF patients. Details of patient inclusion have been reported previously.9–11 Briefly, patient enrolment is done by any attending emergency physician in the participating EDs, who receives specific study protocol instructions during a weekly ED meeting preceding patient recruitment. All suspected AHF cases are confirmed by the principal investigator of each centre based on the Framingham clinical criteria12 and, if possible, the diagnosis is also confirmed by measurement of plasma natriuretic peptide and/or echocardiography during ED or hospital stay following the current ESC guidelines recommendations.3 The principal investigator at each centre is responsible for the final diagnostic adjudication of the cases. The only exclusion criterion for being included in the EAHFE registry is a primary diagnosis of ST-elevation myocardial infarction while concurrently developing AHF (which occurs in about 3% of AHF cases), as the majority of these patients bypass the ED and go directly to the catheterization laboratory. The EAHFE registry does not include any planned intervention, and the management of patients is entirely based on the attending ED physician decisions.

Design of the study

For the FAST-FURO study, we considered patients recruited in the two to six EAHFE cohorts (in which details of EMS management were registered) for whom prehospital care provided by EMS and treatment in the ED had been collected. According to the strategy of Matsue et al.6 and Park et al.,7 patients who did not receive IV furosemide during ED stay (i.e. those receiving only oral furosemide or no furosemide) were not included in the main analysis and this was the only exclusion criteria.

Patients were divided according to whether they received prehospital IV furosemide during EMS care (FAST-FURO group) and those in whom the first dose of IV furosemide was received in the ED (CONTROL group). Doses of IV furosemide provided by EMS were 20–40 mg, but the time between ED arrival and the first IV furosemide administration at the ED as well as the total dose of furosemide provided at the ED were not recorded.

Independent patient variables

We included 20 patient baseline characteristics that corresponded to demographics, comorbidities, functional status, and treatment with disease-modifying drugs (Supplementary material online, Table S1). Signs and symptoms allowing the clinical diagnosis of AHF are reported in Supplementary material online, Table S2. We also estimated the severity of the AHF episode using the MEESSI-AHF risk score, which includes 13 risk predictors obtained during the first patient evaluation at the ED (age, acute coronary syndrome as trigger of decompensation, and systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, low output signs and symptoms, creatinine, potassium, troponin, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, hypertrophy in the electrocardiogram, and the Barthel index and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class recorded at patient presentation at the ED).13 The MEESSI-AHF score stratifies the risk of dying during the 30 days after the ED index event into four categories (low, intermediate, high, and very high risk) and has demonstrated to consistently maintain a very good discriminatory capacity in external national and international cohorts.14,15

Outcome definitions

We measured three co-primary outcomes: (i) in-hospital all-cause mortality during the index episode; (ii) 30-day all-cause mortality after patient arrival at the ED; and (iii) need for prolonged hospitalization, defined as a period longer than 10 days between ED arrival for the index episode and hospital discharge. Follow-up was performed by personal telephone contact and by consultation of medical records.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical data as absolute values and percentages. For comparisons, we used the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test and χ2 test (for trends, if appropriate), respectively. The magnitude of the association between prehospital IV furosemide administration and outcomes was estimated using logistic regression models and expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using the CONTROL group as reference in the following models: (i) unadjusted (Model 1); (ii) adjusted for baseline patient characteristics with significant differences between the FAST-FURO and CONTROL groups (Model 2); (iii) severity of the AHF index episode (Model 3, the MEESSI score was used as a continuous variable for the adjustment); and (iv) fully adjusted model including covariates of Models 2 and 3 (Model 4). For the adjusted models, we created 10 datasets where missing values in the covariates were replaced by imputed values using the multiple imputation technique provided by SPSS software, which is based on random drawings of imputed data from a Bayesian posterior distribution, and we used Mersenne twister as pseudorandom number generator and 2 000 000 as seed. In order to check for consistent findings, several sensitivity analyses were performed in the fully adjusted model (Model 4), by (A) adding patients that did not receive IV diuretics in the ED, (B) excluding patients that did not require hospitalization, (C) excluding patients that were not brought to the ED by EMS ambulances, (D) excluding patients with a first episode of AHF, (E) performing the main analysis in the non-imputed dataset, (F) considering the worst case scenario, i.e. computing all patients lost at follow up as deaths, (G) including only patients with a known left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF); and (H) running a propensity score (PS) based analysis with FAST-FURO and CONTROL patients with comparable probability of receiving IV furosemide by the EMS. For the PS, we used the package adapted from the R programme provided by Python for SPSS. As PS matching does not accept lacking values, missings were replaced by median in continuous variables and by mode in categorical variables. We introduced in the model the 20 patient baseline characteristics and the MEESSI score that was used as surrogate of the severity of the AHF episode, and we used the nearest neighbour approach to find paired PS matched cases, with a maximum standardized difference between pairs of 1%. Finally, pre-specified stratified analyses were performed based on age (≤ or >80 years), sex (male/female), LVEF (≤39%, 40–49%, and 50%), chronic treatment with loop diuretics at home and MEESSI risk category (low, intermediate or high/very high). Statistical differences were set at a less than 0.05 level. All calculations were performed using SPSS software (IBM, New Castle, NY, USA).

Ethics

The EAHFE registry protocol was approved by a central Ethics Committee at the Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (Oviedo, Spain) with the reference numbers 49/2010, 69/2011, 166/13, 160/15, and 205/17. Due to the non-interventional design of the registry, Spanish legislation allows central Ethical Committee approval, accompanied by notification to the local Ethical Committees. All participating patients gave informed consent to be included in the registry and to be contacted for follow-up. The study was carried out in strict compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The authors designed the study, gathered, and analysed the data, vouched for the data and analysis, wrote the paper, and decided to publish.

Results

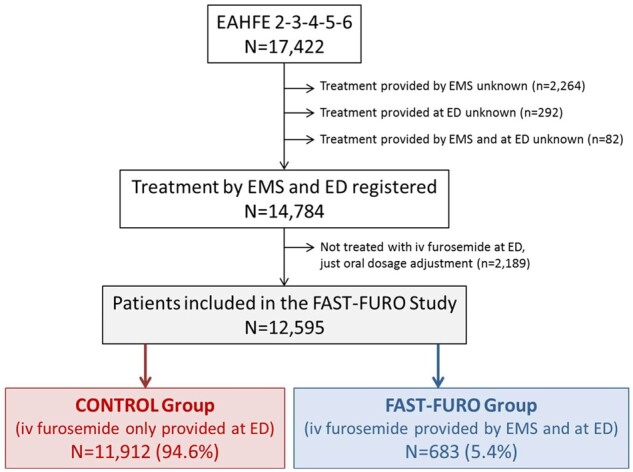

Among the 17 422 patients included in the two to six EAHFE cohorts, 12 595 met the criteria to be included in the analysis of the FAST-FURO study: 683 patients (5.4%) received IV furosemide in the prehospital setting (FAST-FURO group), whereas the remaining 11 912 patients (94.6%) only received IV furosemide in the ED (CONTROL group, Figure 1). Overall, the median age was 83 years (IQR = 76–88) and 42.8% were males. Other patient baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1: comorbidities were frequent, mild or higher functional dependence (Barthel index of 90 or lower) was present in nearly 60% of patients, NYHA class III or IV at baseline was reported in a quarter of cases, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction was the predominant form as it was observed in more than two-third of cases, and chronic treatment with beta-blockers, renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and mineralcorticosteroid-receptor antagonists was present in 45%, 56% and 16% of patients, respectively. Chronic treatment with diuretics at home was received in 75.7% of patients, with no difference between the FAST-FURO and CONTROL groups (75.4% and 75.7%, respectively). Patients in the FAST-FURO group more frequently had diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease and peripheral artery disease and less frequently atrial fibrillation, they were in a better NYHA class at baseline and more frequently had left ventricular systolic dysfunction. With respect to the severity of the AHF episode (Table 1), significant differences were also observed between the two groups, with a more severe decompensation in patients of the FAST-FURO group (30.4% of patients were classified in the high- or very high-risk categories by the MEESSI scale) than those in the CONTROL group (20.7% of patients were in these categories).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for patient inclusion in the FAST-FURO study. ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients included in the FAST-FURO study and comparison between the FAST-FURO and CONTROL groups

| All patients (N = 12 595) | CONTROL group (IV furosemide only provided at the ED) (N = 11 912), n (%) | FAST-FURO group (IV furosemide provided by EMS and at the ED) (N = 683), n (%) | P-value | Missing values, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient baseline characteristics | |||||

| Demographic data | |||||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 83 (76–88) | 83 (76–88) | 82 (74–87) | 0.059 | 5 (0.0) |

| Male | 5498 (43.8) | 6703 (43.6) | 321 (47.3) | 0.054 | 37 (0.3) |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | 10 646 (84.8) | 10 072 (84.8) | 574 (84.3) | 0.728 | 34 (0.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5350 (42.6) | 5021 (42.3) | 329 (48.3) | 0.002 | 35 (0.3) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 3566 (28.4) | 3324 (28.0) | 242 (35.5) | <0.001 | 35 (0.3) |

| Chronic kidney failure (creatinine > 2 mg/mL) | 3561 (28.3) | 3376 (28.4) | 185 (27.2) | 0.482 | 33 (0.3) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1607 (12.8) | 1512 (12.7) | 95 (14.0) | 0.353 | 34 (0.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6341 (50.5) | 6045 (50.9) | 296 (43.5) | <0.001 | 32 (0.3) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 1180 (9.4) | 1094 (9.2) | 86 (12.7) | 0.003 | 37 (0.3) |

| Heart valve disease | 3358 (26.7) | 3176 (26.7) | 182 (26.8) | 0.987 | 36 (0.3) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3017 (24.0) | 2853 (24.0) | 164 (24.1) | 0.953 | 37 (0.3) |

| Dementia | 1514 (12.1) | 1424 (12.0) | 90 (13.2) | 0.331 | 35 (0.3) |

| Active neoplasia | 1766 (14.1) | 1677 (14.1) | 89 (13.1) | 0.461 | 39 (0.3) |

| Previous episodes of acute heart failure | 7556 (62.1) | 7135 (62.1) | 421 (63.0) | 0.619 | 431 (3.4) |

| Baseline status | |||||

| Barthel index (points) | 0.410 | 1043 (8.3) | |||

| No or minimal dependence (>90 points) | 4779 (41.4) | 4532 (41.5) | 247 (38.8) | ||

| Mild to moderate dependence (90–50 points) | 5354 (46.3) | 5047 (46.2) | 307 (48.3) | ||

| Severe or total dependence (<50 points) | 1419 (12.3) | 1337 (12.2) | 82 (12.9) | ||

| NYHA class | 0.004 | 568 (4.5) | |||

| I | 2875 (23.9) | 2723 (23.9) | 152 (23.4) | ||

| II | 6119 (56.8) | 5750 (50.5) | 369 (56.8) | ||

| III | 2826 (23.5) | 2708 (23.8) | 118 (18.2) | ||

| IV | 207 (1.7) | 196 (1.7) | 11 (1.7) | ||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) | 0.009 | 5229 (41.5) | |||

| LVEF <40% | 1341 (18.2) | 1244 (17.9) | 97 (23.5) | ||

| LVEF 40–49% | 980 (13.3) | 921 (13.2) | 59 (14.3) | ||

| LVEF ≥50% | 5045 (68.5) | 4788 (68.9) | 257 (62.2) | ||

| On treatment with disease-modifying drugs | |||||

| Beta-blockers | 5650 (45.2) | 5319 (45.0) | 331 (48.8) | 0.057 | 97 (0.8) |

| Renin–angiotensin system inhibitors | 7050 (56.4) | 6649 (56.2) | 401 (59.1) | 0.149 | 92 (0.7) |

| Mineralcorticosteroid-receptor blockers | 2047 (16.4) | 1947 (16.5) | 100 (14.7) | 0.234 | 92 (0.7) |

| Severity of the acute heart failure episode | |||||

| MEESSI-AHF risk categorya | <0.001 | 4382 (34.8) | |||

| Low risk | 3119 (38.0) | 3001 (38.9) | 118 (24.1) | ||

| Intermediate risk | 3346 (40.7) | 3124 (40.4) | 222 (45.4) | ||

| High risk | 914 (11.1) | 840 (10.9) | 74 (15.1) | ||

| Very high risk | 834 (10.2) | 759 (9.8) | 75 (15.3) | ||

| Components of the MEESSI score at ED arrivalb | |||||

| Barthel index (points), median (IQR) | 70 (45–90) | 70 (45–90) | 55 (30–80) | <0.001 | 2354 (18.7) |

| NYHA-IV class | 5850 (48.0) | 5353 (46.4) | 497 (75.6) | <0.001 | 407 (3.2) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), median (IQR) | 140 (122–157) | 139 (122–157) | 145 (124–165) | <0.001 | 118 (0.9) |

| Respiratory rate (b.p.m.), median (IQR) | 22 (18–26) | 21 (18–26) | 25 (20–30) | <0.001 | 3058 (24.3) |

| Room air pulsioxymetry (%), median (IQR) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (90–96) | 94 (87–97) | 0.801 | 251 (2.0) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), median (IQR) | 1.15 (0.87–1.57) | 1.14 (0.87–1.57) | 1.18 (0.90–1.56) | 0.155 | 143 (1.1) |

| Potassium (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 4.4 (4.0–4.8) | 4.4 (4.0–4.8) | 4.4 (4.0–4.8) | 0.189 | 665 (5.3) |

| Low output signs | 1860 (14.8) | 1651 (13.9) | 209 (30.6) | <0.001 | 19 (0.2) |

| NT-proBNP (ng/mL), median (IQR) | 4021 (1941–8691) | 4026 (1943–8644) | 3976 (1906–9387) | 0.868 | 6043 (48.0) |

| Raised troponin (above 99th percentile) | 3742 (52.9) | 3504 (53.1) | 238 (49.9) | 0.172 | 5523 (43.9) |

| Episode associated with acute coronary syndrome | 324 (2.6) | 270 (2.3) | 54 (8.0) | <0.001 | 91 (0.7) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy in the ECG | 411 (3.4) | 376 (3.3) | 35 (5.2) | 0.006 | 433 (3.4) |

Bold numbers denote statistical significance (P < 0.05).

ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical services.

MEESSI-AHF score is calculated based on 13 variables obtained at patient arrival at emergency department: age, acute coronary syndrome as trigger of decompensation, systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, low output signs and symptoms, creatinine, potassium, troponin, NT-proBNP, hypertrophy in the ECG, and Barthel index and NYHA class at the moment of ED patient presentation.

Age (an individual component of the MEESSI-AHF score) is presented in demographic data.

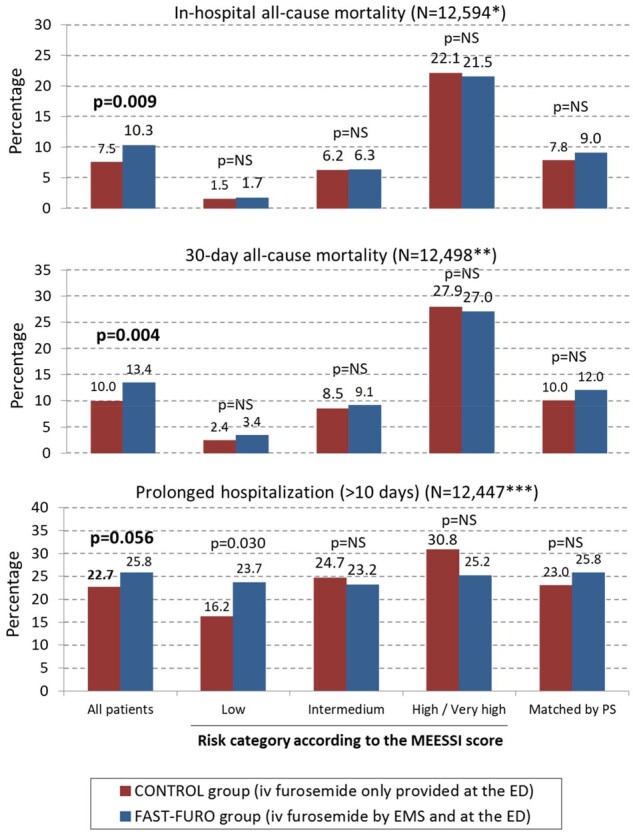

In-hospital mortality was observed in 968 patients (7.7%) and was more frequent in the FAST-FURO (70 patients, 10.3%) than in the CONTROL group (898 patients, 7.5%; OR = 1.403, 95% CI = 1.085–1.81; 3 P = 0.009). Only one patient lacked vital status at hospital discharge. There were 1269 deaths within the first 30 days after the index AHF event (30-day mortality 10.2%), and this was more frequently observed in the FAST-FURO (91 patients, 13.4%) than in the CONTROL group [1178 patients (10.0%); OR = 1.403, 95% CI = 1.146–1.764; P = 0.004]. Ninety-seven patients (0.8%) did not complete 30 days of follow-up, and therefore, they were not considered for the 30-day mortality analysis. Finally, prolonged hospitalization (>10 days) was observed in 2844 patients (22.8%), being more frequent in the FAST-FURO (175 patients, 25.8%) than in the CONTROL group (2669 patients, 22.7%; OR = 1.189, 95% CI = 0.995–1.419; P = 0.056). In 148 patients (1.2%), the length of hospital stay was unknown. When all these outcomes were assessed across the MEESSI-AHF risk categories, there were no significant differences between two groups in any comparison, with the exception of prolonged hospitalization in the low-risk category, that was more frequently observed in patients that received very early furosemide by the EMS (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, and prolonged hospitalization in the FAST-FURO and CONTROL groups. The analysis is presented for the whole cohort (left), by each risk category of the MEESSI scale (middle), and in 599 pairs of patients matched by the propensity score to be treated with intravenous furosemide before arrival to the emergency department (right). aOnly 8213 out of 12 594 (65.2%) were classified by the MEESSI risk score and in 599 pairs of patients matched by propensity score. bOnly 8148 out of 12 498 (65.2%) were classified by the MEESSI risk score and in 599 pairs of patients matched by propensity score. cOnly 8127 out of 12 447 (65.3%) were classified by the MEESSI risk score and in 599 pairs of patients matched by propensity score. ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service; PS, propensity score.

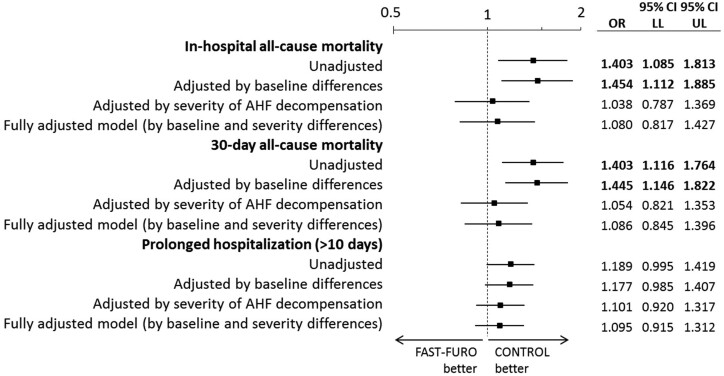

Adjustment for potential confounders among patient baseline characteristics (Model 2 that included diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, NYHA class, and LVEF) rendered few changes with respect to unadjusted analyses, with the differences of in-hospital and 30-day mortality remaining significant. Conversely, these significant differences were attenuated when the adjustment was performed by the severity of the episode estimated by the MEESSI-AHF score (Model 3), and the same was observed when adjustment was performed for the patient baseline characteristics included in Model 2 plus the severity of AHF episode included in Model 3 (Model 4, fully adjusted). In this fully adjusted model, the OR for in-hospital mortality for patients of the FAST-FURO group was 1.080 (95% CI = 0.817–1.427), the OR for 30-day mortality was 1.086 (95% CI = 0.845–1.396), and the OR for prolonged hospitalization was 1.095 (0.915–1.312) (Figure 3). Several sensitivity analyses showed consistency of our findings (Table 2), including a PS analysis of 599 pairs of patients that were matched by PS. The two groups matched by PS did not exhibit a large imbalance for any of the covariates (<25% of relative difference, P > 0.05 for all variables, Supplementary material online, Figure S1). In this PS analysis, in-hospital mortality was observed in 9.0% in the FAST-FURO group and 7.8% in the CONTROL group (OR = 1.166, 95% CI = 0.775–1.754; P = 0.462), 30-day mortality in 12.0% and 10.0%, respectively (OR = 1.217, 95% CI = 0.846–1.752; P = 0.290), and prolonged hospitalization in 25.8% and 23%, respectively (OR = 1.161, 95% CI = 0.890–1.514; P = 0.271).

Figure 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio for the assessed endpoints. Variables corresponding to baseline characteristics used for adjustment were those resulting in significant differences between groups in the univariable analysis: diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, peripheral artery disease, NYHA class, and left ventricular ejection fraction. The variable used for adjustment for the severity of the AHF decompensation was the MEESSI score, taken as a continuous variable. Bold numbers denote statistical significance (P < 0.05). AHF, acute heart failure; CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit; OR, odds ratio; UL, upper limit.

Table 2.

Odds ratio (with 95% confidence interval) in the fully adjusted model (by differences in baseline patient characteristics and severity of the acute heart failure episode) for adverse short-term outcomes for patients who received intravenous furosemide during the prehospital phase (FAST-FURO group) compared with those who did not receive this treatment (CONTROL group)

| In-hospital all-cause mortality OR (95% CI) | 30-day all-cause mortality OR (95% CI) | Prolonged hospitalization OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary adjusted analysis | 1.080 (0.817–1.427) | 1.086 (0.845–1.396) | 1.095 (0.915–1.312) |

| Sensitivity analysis A (including patients not treated with IV furosemide at ED) | 1.231 (0.953–1.590) | 1.161 (0.978–1.378) | 1.161 (1.043–1.225) |

| Sensitivity analysis B (only hospitalized patients) | 0.918 (0.686–1.229) | 0.935 (0.716–1.222) | 0.981 (0.817–1.179) |

| Sensitivity analysis C (only patients brought to ED by EMS) | 0.937 (0.704–1.246) | 1.004 (0.777–1.298) | 1.051 (0.871–1.269) |

| Sensitivity analysis D (only patients with previously known HF) | 1.321 (0.950–1.836) | 1.246 (0.926–1.677) | 1.056 (0.836–1.332) |

| Sensitivity analysis E (without multiple imputation) | 0.920 (0.571–1.482) | 0.996 (0.659–1.506) | 0.958 (0.723–1.269) |

| Sensitivity analysis F (patients missed at 30-day follow up considered as deaths, worst case scenario) | — | 1.180 (0.934–1.492) | — |

| Sensitivity analysis G (including only patients with known LVEF) | 1.248 (0.866–1.798) | 1.172 (0.840–1.634) | 1.091 (0.865–1.375) |

| Sensitivity analysis H (with 599 pairs of patients matched by propensity score) | 1.166 (0.775–1.754) | 1.217 (0.846–1.752) | 1.161 (0.890–1.514) |

Reference group for all ORs is CONTROL group.

CI, confidence interval; ED, emergency department; EMS, emergency medical service; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OR, odds ratio.

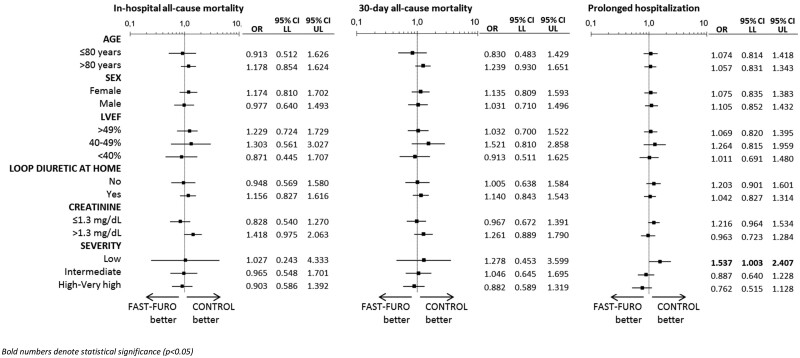

When our cohort was stratified by age, sex, LVEF, chronic treatment with loop diuretics, creatinine at ED arrival and risk category using the fully adjusted model, we failed to show a significant association between early IV furosemide administration and the outcomes in any of the subgroups of patients, with the exception of only low-risk FAST-FURO patients, for whom an increased risk of having prolonged hospitalization was observed in comparison with CONTROL low-risk patients (OR = 1.537, 95% CI = 1.003–2.407; P = 0.049) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stratified analysis by age, sex, left ventricular ejection fraction, on treatment with loop diuretic at home, creatinine concentration at emergency department arrival and severity of the acute heart failure episode assessed by the MEESSI-AHF scale. Bold numbers denote statistical significance (P < 0.05). CI, confidence interval; LL, lower limit; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OR, odds ratio; UL, upper limit.

Discussion

The main conclusion of the FAST-FURO study is that very early IV furosemide administration by EMS during the prehospital phase in AHF patients who will require IV furosemide treatment at the ED was not associated with short-term outcomes with respect to patients treated with IV furosemide exclusively in the ED. This finding seems to be consistent across multiple sensitivity analyses, including PS analysis, and there were no significant subsets of patients in which a positive impact on any of the outcomes evaluated in the present study could be suggested.

Several previous studies have investigated the impact of early AHF treatment on outcomes. Peacock and collaborators were the first to test this hypothesis through retrospectively analyses of the ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) cohort.16–18 However, they mainly investigated the impact of early use of vasoactive drugs (either vasopressors or vasodilators) on prognosis,16,17 and when the specific association of early IV furosemide with in-hospital mortality was evaluated, a 2.1% increase of in-hospital mortality was reported per every 4 h of delay in the time to first IV furosemide.18 A further analysis of 6971 ADHERE patients with detailed data recorded in the ED (forming the ADHERE-EM -emergency module- cohort) showed that the time from ED admission to the administration of first IV HF therapy (loop diuretics, inotropes, or vasodilators, whichever was administered first) was independently associated with a modest but significant increase in the risk of in-hospital mortality and length of hospitalization when time to treatment was examined as a continuous variable, but did not influence 30-day patient outcomes (all-cause death or re-admission).19 Remarkably, when diuretics were the only drug intravenously provided in the ED, the magnitude of associations were lower than when they were provided in association with vasodilators and/or inotropes.

Based on these findings, early management and treatment of AHF patients in the EDs have gained attraction as a potential way to improve prognosis.20 The concept that early IV furosemide administration in the ED may improve outcomes has been specifically addressed in two recent studies, but the results were inconsistent. Matsue et al.6 reported a beneficial effect of early IV furosemide administration in their Japanese cohort, with an adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality of 0.39 for those receiving IV furosemide within the first 60 min of ED arrival. Conversely, Park et al.7 failed to demonstrate any benefit in their Korean cohort using the same definition of early administration (<60 min). Importantly, both studies excluded patients who had received prehospital IV furosemide at a very early stage, i.e. during the pre-hospital phase, while they were managed by EMS. Additionally, both studies focused only on hospitalized patients, thus excluding between one-third and one-sixth of AHF patients entirely managed at the ED and directly discharged home without hospitalization.8 In this sense, the FAST-FURO study covers these two previous limitations (as our study considered treatment provided during the prehospital phase and included all AHF patients arriving to the ED and not only those who were hospitalized), and the results back the findings reported by Park et al. suggesting a lack of impact of early IV furosemide administration on short-term prognosis. Remarkably, in our series, only 5.4% of patients received IV diuretics during the prehospital. Nonetheless, close to 50% of our patients arrived to the ED by their own vehicles, and not all patients arriving to the ED by ambulance were brought by EMS ambulances staffed with physicians allowed to provide IV drugs. Therefore, a more generalized use of IV furosemide in the prehospital setting could eventually lead to different results from those reported in the present study, and should be investigated in other cohorts.

Although the prehospital care by EMS is fast and usually does not take more than one hour to bring patients to the ED, patients can stay in the ED for several hours with significant delays until the first treatment is provided due to the frequent long ED waiting times and overcrowding, as in the case in Spanish public EDs.21,22 Therefore, EMS provision of IV furosemide can advance the initiation of AHF treatment by several hours (and not just the 30–60 min between EMS arrival to the patient’s home and transfer to the ED). Indeed, EMS care is not limited to furosemide administration. The SEMICA-2 study evaluated the role of intensive management by EMS in 1493 patients brought to the ED with an advanced life support ambulance, in which the staff is allowed to provide IV treatments.23 Prehospital treatment of these patients consisted in oxygen in 71.2%, diuretics in 27.9%, nitroglycerine in 13.5%, and non-invasive ventilation in 5.3%. Thirty percent of patients who received at least two of these treatments, and were therefore considered as managed in a high-intensity approach, obtained a significant reduction of 7-day mortality (adjusted OR of 0.52), and lower and non-significant reductions in prolonged hospitalization and in-hospital and 30-day mortality. The specific role of furosemide was not investigated, and this makes the FAST-FURO study the first to assess the effect of IV furosemide administered by EMS on the prognosis of AHF patients. Finally, diagnosis of AHF in the prehospital setting can sometimes be challenging. In a recent survey of 104 EMS regions from 18 countries, Harjola et al.24 reported that the prevalence of AHF protocols is rather high, but the contents seem to vary. In addition, the difficulty of diagnosing suspected AHF seems to be moderate compared with other prehospital conditions, and this difficulty is even greater in the dispatch centre evaluating patient complaints, thereby limiting the adjudication of an advanced life support team able to provide IV treatment. Hence, improvement of these prehospital aspects could lead to more frequent, homogeneous and complete AHF patient treatment by EMS which, in turn, could improve the prognosis of AHF.

The interpretation of the lack of effect of early prehospital administration of IV furosemide on short-term outcomes of AHF patients is challenging. The main difficulty lies in the lack of data about doses provided and length of time between IV furosemide administration by EMS and the ED. It is feasible that the advancement of administration of IV furosemide treatment was limited to some minutes or up to one hour, but it is unlikely that this difference in time had any large impact on outcomes. In fact, 60 min was the cut-off used in the Matsue et al.6 and Park et al.7 studies to classify patients in the early or late treatment groups, and in the study by Park et al. this time difference had no impact on prognosis.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, as in every observational study, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Second, the patients came from a nationwide cohort with a universal public health care system, and external validation might be needed to confirm their generalizability. Advanced live support ambulances in Spain are staffed by doctors and nurses who are allowed to provide IV drugs in contrast to other countries and healthcare systems. In addition, there is no common specific protocol guiding prehospital IV furosemide administration in Spain, and although EMS physicians follow the ESC guidelines and provide furosemide when AHF is suspected based on clinical findings, this could not be homogenously performed in all the patients included in the FAST-FURO study. Finally, Spanish EDs are able to provide observations, which is not the rule in other countries. Third, in our study, we did not record the time between EMS and ED administration of IV furosemide, nor the doses of IV furosemide provided by the EMS and in the EDs. Neither are doses of diuretics at home recorded in the EAHFE Registry. Therefore, these variables were not accounted for in the adjusted models. On the other hand, certain parameters of the MEESSI-AHF risk score assessed at the ED could have resulted modified by the prehospital treatment (i.e. systolic blood pressure, oxygen saturation, potassium, creatinine, etc.) and thus the MEESSI-AHF score could not precisely reflect the severity of disease at time of EMS evaluation. Fourth, the FAST-FURO study included a high percentage of elderly AHF patients in whom frailty and dependence are frequent and are two factors strongly related to outcomes.25,26 Although stratified analysis did not suggest differences depending on age, we believe that the effects of IV administration in other AHF populations should be explored. Fifth, this was real life cohort without any planned intervention, and there could be differences in physician strategies of diuretic use. In fact, two recent consensus documents try to achieve a more homogeneous approach.27,28 Sixth, the diagnosis of AHF was based on clinical criteria, and the final diagnosis of AHF was not supported in all cases by natriuretic peptide or echocardiographic results. Although these two latter limitations could impose caution in the interpretation of some of our conclusions, this approach makes our findings more generalizable to the real-world ED practice. Seventh, the number of missing values for some variables was high such as, for example, the LVEF and the MEESSI-AHF score (missing in 41.5% and 34.8% of the patients, respectively). Despite the use of multiple imputation and PS matching these strategies could not be completely adjusted due to the important imbalance in LVEF, in which more patients with reduced LVEF received prehospital furosemide and it is known that the mortality of these patients is higher than that of patients with preserved LVEF. Finally, we did not correct results for multiple comparisons, as this was an exploratory study. Therefore, there was the possibility of chance findings, one of which could be related to the only difference found in the outcome analysis showing a longer length of hospitalization with prehospital IV furosemide use in the subgroup of patients with a low MEESSI-AHF score.

Conclusion

Early IV furosemide is more frequently administered by EMS to the sickest patients, and after adjustment for several confounders, no association was found with changes in short-term mortality or length of hospitalization, either if patients required hospitalization or were discharged home during the decompensation episode.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care online.

Investigators of the ICA-SEMES Research Group (full list)

Marta Fuentes, Cristina Gil (Hospital Universitario de Salamanca), Héctor Alonso, Enrique Pérez-Llantada (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla de Santander), Francisco Javier Martín-Sánchez, Guillermo Llopis García, Mar Suárez Cadenas (Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid), Òscar Miró, Víctor Gil, Rosa Escoda, Sira Aguiló, Carolina Sánchez (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona), María José Pérez-Durá, Eva Salvo (Hospital Politénic La Fe de Valencia), José Pavón (Hospital Dr Negrín de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Antonio Noval (Hospital Insular de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), José Manuel Torres (Hospital Reina Sofía de Córdoba), María Luisa López-Grima, Amparo Valero, María Ángeles Juan (Hospital Dr Peset de Valencia), Alfons Aguirre, Maria Angels Pedragosa, Silvia Mínguez Masó (Hospital del Mar de Barcelona), María Isabel Alonso, Francisco Ruiz (Hospital de Valme de Sevilla), José Miguel Franco (Hospital Miguel Servet de Zaragoza), Ana Belén Mecina (Hospital de Alcorcón de Madrid), Josep Tost, Marta Berenguer, Ruxandra Donea (Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa), Susana Sánchez Ramón, Virginia Carbajosa Rodríguez (Hospital Universitario Rio Hortega de Valladolid), Pascual Piñera, José Andrés Sánchez Nicolás (Hospital Reina Sofía de Murcia), Raquel Torres Garate (Hospital Severo Ochoa de Madrid), Aitor Alquézar-Arbé, Miguel Alberto Rizzi, Sergio Herrera (Hospital de la Santa Creu y Sant Pau de Barcelona), Javier Jacob, Alex Roset, Irene Cabello, Antonio Haro (Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge de Barcelona), Fernando Richard, José María Álvarez Pérez, María Pilar López Diez (Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Pablo Herrero Puente, Joaquín Vázquez Álvarez, Belén Prieto García, María García García, Marta Sánchez González (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias de Oviedo), Pere Llorens, Patricia Javaloyes, Víctor Marquina, Inmaculada Jiménez, Néstor Hernández, Benjamín Brouzet, Begoña Espinosa, Adriana Gil (Hospital General de Alicante), Juan Antonio Andueza (Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón de Madrid), Rodolfo Romero (Hospital Universitario de Getafe de Madrid), Martín Ruíz, Roberto Calvache (Hospital de Henares de Madrid), María Teresa Lorca Serralta, Luis Ernesto Calderón Jave (Hospital del Tajo de Madrid), Beatriz Amores Arriaga, Beatriz Sierra Bergua (Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa de Zaragoza), Enrique Martín Mojarro, Brigitte Silvana Alarcón Jiménez (Hospital Sant Pau i Santa Tecla de Tarragona), Lisette Travería Bécquer, Guillermo Burillo (Hospital Universitario de Canarias de Tenerife), Lluís Llauger García, Gerard Corominas LaSalle (Hospital Universitari de Vic de Barcelona), Carmen Agüera Urbano, Ana Belén García Soto, Elisa Delgado Padial (Hospital Costa del Sol de Marbella de Málaga), Ester Soy Ferrer, María Adrover Múñoz (Hospital Josep Trueta de Girona), José Manuel Garrido (Hospital Virgen Macarena de Sevilla), Francisco Javier Lucas-Imbernón (Hospital General Universitario de Albacete), Rut Gaya (Hospital Juan XXIII de Tarragona), Carlos Bibiano, María Mir, Beatriz Rodríguez (Hospital Infanta Leonor de Madrid), José Luis Carballo (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense), Esther Rodríguez-Adrada, Belén Rodríguez Miranda, Monika Vicente Martín (Hospital Rey Juan Carlos de Móstoles de Madrid), Pere Coma Casanova, Joan Espinach Alvarós (Hospital San Joan de Deu de Martorell, Barcelona).

Conflict of interest: The following authors report conflict of interests: O.M. received grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III supported with funds from the Spanish Ministry of Health and FEDER (PI15/01019, PI18/00773), La Marató de TV3 (2015/2510), and from the Catalonian Government for Consolidated Groups of Investigation (GRC 2009/1385, 2014/0313, 2017/1424). The rest of the authors state that they have no specific conflict of interests related to the present work. The ICA-SEMES Research Group has received unrestricted support from Orion Pharma and Novartis. The present study has been designed, performed, analysed, and written exclusively by the authors independently of any funding source.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

the ICA-SEMES Research Group:

Marta Fuentes, Cristina Gil, Héctor Alonso, Enrique Pérez-Llantada, Francisco Javier Martín-Sánchez, Guillermo Llopis García, Mar Suárez Cadenas, Òscar Miró, Víctor Gil, Rosa Escoda, Sira Aguiló, Carolina Sánchez, María José Pérez-Durá, Eva Salvo, José Pavón, Antonio Noval, José Manuel Torres, María Luisa López-Grima, Amparo Valero, María Ángeles Juan, Alfons Aguirre, Maria Angels Pedragosa, Silvia Mínguez Masó, María Isabel Alonso, Francisco Ruiz, José Miguel Franco, Ana Belén Mecina, Josep Tost, Marta Berenguer, Ruxandra Donea, Susana Sánchez Ramón, Virginia Carbajosa Rodríguez, Pascual Piñera, José Andrés Sánchez Nicolás, Raquel Torres Garate, Aitor Alquézar-Arbé, Miguel Alberto Rizzi, Sergio Herrera, Javier Jacob, Alex Roset, Irene Cabello, Antonio Haro, Fernando Richard, José María Álvarez Pérez, María Pilar López Diez, Pablo Herrero Puente, Joaquín Vázquez Álvarez, Belén Prieto García, María García García, Marta Sánchez González, Pere Llorens, Patricia Javaloyes, Víctor Marquina, Inmaculada Jiménez, Néstor Hernández, Benjamín Brouzet, Begoña Espinosa, Adriana Gil, Juan Antonio Andueza, Rodolfo Romero, Martín Ruíz, Roberto Calvache, María Teresa Lorca Serralta, Luis Ernesto Calderón Jave, Beatriz Amores Arriaga, Beatriz Sierra Bergua, Enrique Martín Mojarro, Brigitte Silvana Alarcón Jiménez, Lisette Travería Bécquer, Guillermo Burillo, Lluís Llauger García, Gerard Corominas LaSalle, Carmen Agüera Urbano, Ana Belén García Soto, Elisa Delgado Padial, Ester Soy Ferrer, María Adrover Múñoz, José Manuel Garrido, Francisco Javier Lucas-Imbernón, Rut Gaya, Carlos Bibiano, María Mir, Beatriz Rodríguez, José Luis Carballo, Esther Rodríguez-Adrada, Belén Rodríguez Miranda, Monika Vicente Martín, Pere Coma Casanova, and Joan Espinach Alvarós

References

- 1.-Chioncel O, Mebazaa A, Maggioni AP, Harjola VP, Rosano G, Laroche C, Piepoli MF, Crespo-Leiro MG, Lainscak M, Ponikowski P, Filippatos G, Ruschitzka F, Seferovic P, Coats AJS, Lund LH; ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry Investigators. Acute heart failure congestion and perfusion status—impact of the clinical classification on in-hospital and long-term outcomes; insights from the ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1338–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.-Javaloyes P, Miró Ò, Gil V, Martín‐Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Herrero P, Takagi K, Alquézar‐Arbé A, López Díez MP, Martín E, Bibiano C, Escoda R, Gil C, Fuentes M, Llopis García G, Álvarez Pérez JM, Jerez A, Tost J, Llauger L, Romero R, Garrido JM, Rodríguez‐Adrada E, Sánchez C, Rossello X, Parissis J, Mebazaa A, Chioncel O, Llorens P; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Clinical phenotypes of acute heart failure based on signs and symptoms of perfusion and congestion at emergency department presentation and their relationship with patient management and outcomes. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:1353–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola V-P, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129–2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llorens P, Miró Ò, Herrero P, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Valero A, Alonso H, Pérez-Durá MJ, Noval A, Gil-Román JJ, Zapater P, Llanos L, Gil V, Perelló R.. Clinical effects and safety of different strategies for administering intravenous diuretics in acutely decompensated heart failure: a randomised clinical trial. Emerg Med J 2014;31:706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ng KT, Yap JLL.. Continuous infusion vs. intermittent bolus injection of furosemide in acute decompensated heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Anaesthesia 2018;73:238–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsue Y, Damman K, Voors AA, Kagiyama N, Yamaguchi T, Kuroda S, Okumura T, Kida K, Mizuno A, Oishi S, Inuzuka Y, Akiyama E, Matsukawa R, Kato K, Suzuki S, Naruke T, Yoshioka K, Miyoshi T, Baba Y, Yamamoto M, Murai K, Mizutani K, Yoshida K, Kitai T.. Time-to-furosemide treatment and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:3042–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park JJ, Kim SH, Oh IY, Choi DJ, Park HA, Cho HJ, Lee HY, Cho JY, Kim KH, Son JW, Yoo BS, Oh J, Kang SM, Baek SH, Lee GY, Choi JO, Jeon ES, Lee SE, Kim JJ, Lee JH, Cho MC, Jang SY, Chae SC, Oh BH.. The effect of door-to-diuretic time on clinical outcomes in patients with acute heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2018;6:286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.-Miró Ò, Levy PD, Möckel M, Pang PS, Lambrinou E, Bueno H, Hollander JE, Harjola V-P, Diercks DB, Gray AJ, DiSomma S, Papa AM, Collins SP.. Disposition of emergency department patients diagnosed with acute heart failure. Eur J Emerg Med 2017;24:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Llorens P, Javaloyes P, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Jacob J, Herrero-Puente P, Gil V, Garrido JM, Salvo E, Fuentes M, Alonso H, Richard F, Lucas FJ, Bueno H, Parissis J, Müller CE, Miró Ò; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Time trends in characteristics, clinical course, and outcomes of 13,791 patients with acute heart failure. Clin Res Cardiol 2018;107:897–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Llauger L, Jacob J, Moreno LA, Aguirre A, Martín-Mojarro E, Romero-Carrete JC.. Worsening renal function during an episode of acute heart failure and its relation to short- and long-term mortality: associated factors in the Epidemiology of Acute heart failure in Emergency Departments-Worsening Renal Function study. Emergencias 2020;32:332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miró Ò, Gil V, Rosselló X, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Llorens P, Jacob J.. Patients with acute heart failure discharged from the emergency department and classified as low risk by the MEESSI score (multiple risk estimate based on the Spanish emergency department scale): prevalence of adverse events and predictability. Emergencias 2019;31:5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D.. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham heart study subjects. Circulation 1993;88:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miró Ò, Rossello X, Gil V, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Llorens P, Herrero-Puente P, Jacob J, Bueno H, Pocock SJ; ICA-SEMES Research Group. Predicting 30-day mortality for patients with acute heart failure in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:698–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wussler D, Kozhuharov N, Sabti Z, Walter J, Strebel I, Scholl L, Miró O, Rossello X, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Pocock SJ, Nowak A, Badertscher P, Twerenbold R, Wildi K, Puelacher C, de Lavallaz Du FJ, Shrestha S, Strauch O, Flores D, Nestelberger T, Boeddinghaus J, Schumacher C, Goudev A, Pfister O, Breidthardt T, Mueller C.. External validation of the MEESSI acute heart failure risk score. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miró Ò, Rosselló X, Gil V, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Llorens P, Herrero P, Jacob J, López-Grima ML, Gil C, Lucas Imbernón FJ, Garrido JM, Pérez-Durá MJ, López-Díez MP, Richard F, Bueno H, Pocock SJ.. The usefulness of the MEESSI score for risk stratification of patients with acute heart failure at the emergency department. Rev Esp Cardiol 2019;72:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.-Peacock Iv WF, Fonarow GC, Emerman CL, Mills RM, Wynne J.. Impact of early initiation of intravenous therapy for acute decompensated heart failure on outcomes in ADHERE. Cardiology 2007;107:44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peacock WF, Emerman C, Costanzo MR, Diercks DB, Lopatin M, Fonarow GC.. Early vasoactive drugs improve heart failure outcomes. Congest Heart Fail 2009;15:256–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.-Maisel AS, Peacock WF, McMullin N, Jessie R, Fonarow GC, Wynne J, Mills RM.. Timing of immunoreactive B-type natriuretic peptide levels and treatment delay in acute decompensated heart failure: an ADHERE (Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.-Wong YW, Fonarow GC, Mi X, Peacock WF, Mills RM, Curtis LH, Qualls LG, Hernandez AF.. Early intravenous heart failure therapy and outcomes among older patients hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure: findings from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Registry Emergency Module (ADHERE-EM). Am Heart J 2013;166:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mebazaa A, Yilmaz MB, Levy P, Ponikowski P, Peacock WF, Laribi S, Ristic AD, Lambrinou E, Masip J, Riley JP, McDonagh T, Mueller C, deFilippi C, Harjola VP, Thiele H, Piepoli MF, Metra M, Maggioni A, McMurray J, Dickstein K, Damman K, Seferovic PM, Ruschitzka F, Leite-Moreira AF, Bellou A, Anker SD, Filippatos G.. Recommendations on pre-hospital & early hospital management of acute heart failure: a consensus paper from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, the European Society of Emergency Medicine and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:544–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rivas-Clemente FPJ, Pérez-Baena S, Ochoa-Vilor S, Hurtado-Gallar J.. Patient-initiated emergency department visits without primary care follow-up: frequency and characteristics. Emergencias 2019;31:234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiménez Moreno FX. Are we using our emergency services as if they were Google? Emergencias 2019;31:225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miró Ò, Hazlitt M, Escalada X, Llorens P, Gil V, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Harjola P, Rico V, Herrero-Puente P, Jacob J, Cone DC, Möckel M, Christ M, Freund Y, di Somma S, Laribi S, Mebazaa A, Harjola V-P; On behalf of the ICA-SEMES Research Group. Effects of the intensity of prehospital treatment on short-term outcomes in patients with acute heart failure: the SEMICA-2 study. Clin Res Cardiol 2018;107:347–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harjola P, Miró Ò, Martín-Sánchez FJ, Escalada X, Freund Y, Penaloza A, Christ M, Cone DC, Laribi S, Kuisma M, Tarvasmäki T, Harjola V; EMS-AHF Study Group. Pre-hospital management protocols and perceived difficulty in diagnosing acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2020. Feb; 7 (1): 289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aguilar Ginés S. Prognosis in heart failure: importance of physical frailty at the time of admission. Emergencias 2020;32:147–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Llopis García G, Sánchez SM, García Briñón MA, Alonso CF, Del Castillo JG, Martín-Sánchez FJ.. Physical frailty and its impact on long-term outcomes in older patients with acute heart failure after discharge from an emergency department. Emergencias 2019;31:413–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mullens W, Damman K, Testani JM, Martens P, Mueller C, Lassus J, Tang WHW, Skouri H, Verbrugge FH, Orso F, Hill L, Dilek U, Lainscak M, Rossignol P, Metra M, Mebazaa A, Seferovic P, Ruschitzka F, Coats A.. Evaluation of kidney function throughout the heart failure trajectory—a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2020;22:584–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mullens W, Damman K, Harjola VP, Mebazaa A, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Martens P, Testani JM, Tang WHW, Orso F, Rossignol P, Metra M, Filippatos G, Seferovic PM, Ruschitzka F, Coats AJ.. The use of diuretics in heart failure with congestion—a position statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2019;21:137–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.