Abstract

The metal centres in metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts are responsible for the rearrangement of atoms and electrons during complex chemical reactions, and they enable selective pathways of charge and spin transfer, bond breaking/making and the formation of new molecules. Mapping the electronic structural changes at the metal sites during the reactions gives a unique mechanistic insight that has been difficult to obtain to date. The development of X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) enables powerful new probes of electronic structure dynamics to advance our understanding of metalloenzymes. The ultrashort, intense and tunable XFEL pulses enable X-ray spectroscopic studies of metalloenzymes, molecular catalysts and chemical reactions, under functional conditions and in real time. In this Technical Review, we describe the current state of the art of X-ray spectroscopy studies at XFELs and highlight some new techniques currently under development. With more XFEL facilities starting operation and more in the planning or construction phase, new capabilities are expected, including high repetition rate, better XFEL pulse control and advanced instrumentation. For the first time, it will be possible to make real-time molecular movies of metalloenzymes and catalysts in solution, while chemical reactions are taking place.

In 1895, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered X-rays, which have revolutionized imaging technology1,2. The power of X-rays led to one of the most profound discoveries of the twentieth century: the first high-resolution image of DNA, the molecule of life, revealing its double-helix molecular structure3. Whereas the penetrating power of X-rays benefits medical and large-scale imaging applications, it is the short wavelength and high energy of X-rays that enable the characterization of the atomic and electronic structure of matter, benefitting many areas of science. X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques provide atomic-scale structural information of periodic systems (crystalline) and X-ray scattering provides atomic to mesoscale structural information of non-periodic systems (solutions, non-crystalline). Various forms of X-ray microscopy reveal detailed structural information of complex, non-periodic systems with better than 10-nm resolution, and can further provide elemental specificity. Numerous X-ray spectroscopy techniques provide detailed insights into the local atomic and electronic structure and bonding energetics of many systems in an element-specific manner (local chemical environment).

Ongoing efforts over the past 40 years have pushed these methods to ever better resolution and sensitivity with the development of increasingly brighter synchrotron radiation (SR) sources. In these sources, relativistic electrons circulate in a storage ring, consisting of a series of straight sections connected by bending magnets. The sideways acceleration of the electrons at the bending magnets creates an intense horizontal fan of SR, and periodic arrays of magnets (undulators, wigglers) in the straight sections force the electrons into slalom-like trajectories, creating even brighter SR. Several dozen such facilities now operate worldwide, serving tens of thousands of scientists annually. As the latest round of SR facility upgrades is underway, these powerful X-ray light sources are now approaching a physical limit of possible brightness, the diffraction limit. Another limit of SR sources is the duration of each X-ray pulse, typically 10–100 ps, which defines the fastest timescales accessible with SR (for instance, by stroboscopic probing of dynamics), analogous to the shutter time of an ultrafast camera.

Advancing beyond these limits was enabled by switching from a storage ring to a linear accelerator as the source of relativistic electrons; thus, the X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) was born. The reduced electron beam emittance and higher energy, combined with electron bunch compression and a very long undulator (~100 m), causes the electrons to emit radiation no longer individually but cooperatively in the form of self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE) (FIG. 1). The dramatically increased peak power of XFEL pulses (more than nine orders of magnitude over SR pulses) and the ability to produce extremely short pulses (typically 1–100 fs and, recently, down to the attosecond regime) have revolutionized X-ray science. Femtoseconds (10−15 s) are the fundamental timescale for nuclear motion. Combining this timescale with the atomic and electronic structure sensitivity of X-rays provides, for the first time, simultaneous spatial and temporal access to molecular systems during their various functions as molecules are transformed. How this groundbreaking task can be achieved in metalloenzymes and molecular transition-metal catalysts, using XFEL-based X-ray spectroscopy in combination with X-ray diffraction and scattering, is the subject of this Technical Review.

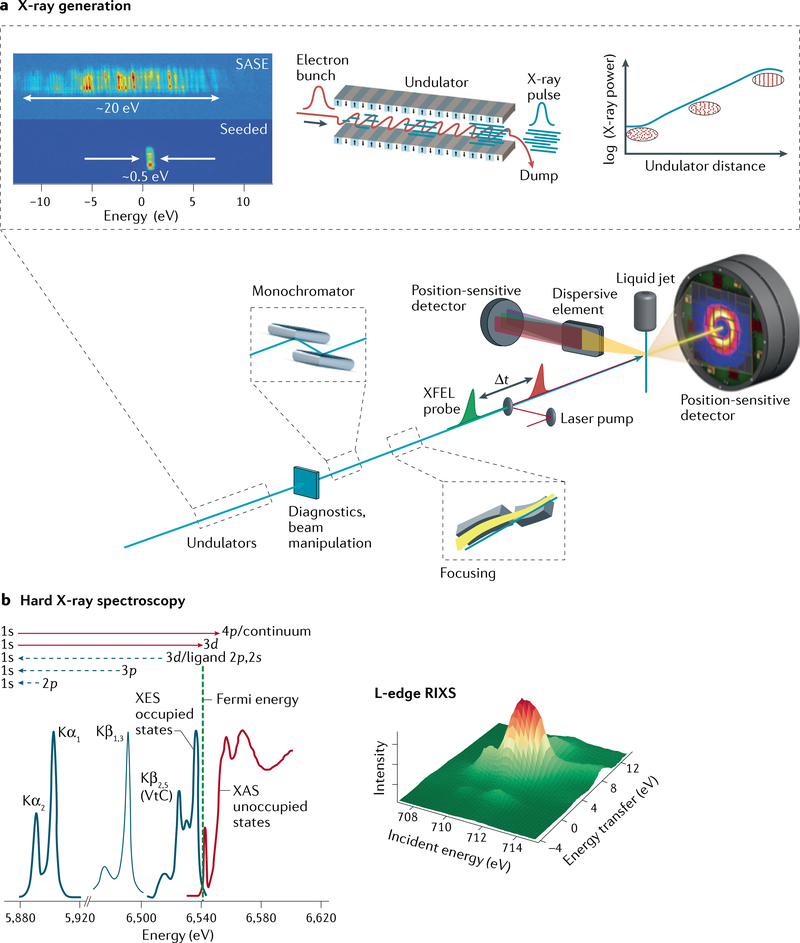

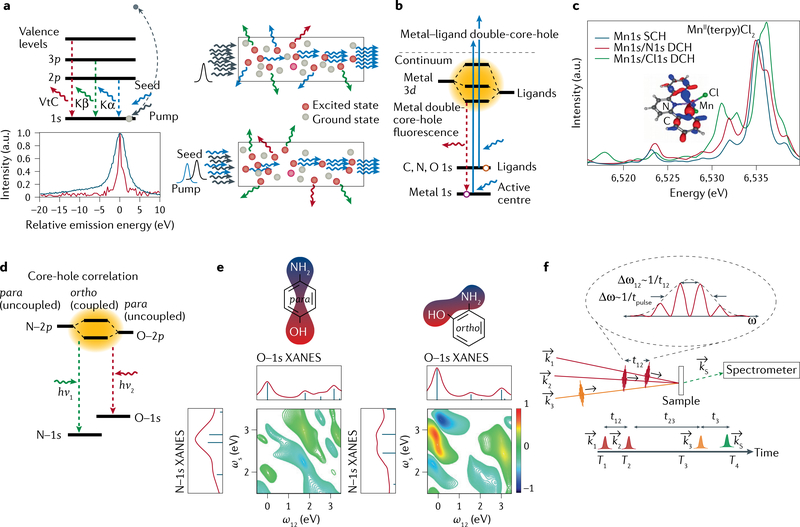

Fig. 1 |. X-ray free-electron laser scheme and experimental design for spectroscopy and diffraction and/or scattering experiments of metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts.

a | Coherent X-rays are generated using relativistic electrons from a linear accelerator propagating through a periodic array of magnets (undulator). The transverse undulating motion of the electrons in the magnetic field gives rise to (spontaneous) X-ray emission. Over a long propagation distance (~100 m), the X-ray field causes microbunching of the electrons at the X-ray wavelength, which, in turn, leads to stronger coherent emission, further microbunching and exponential growth of the coherent X-ray emission. At saturation, the X-ray pulses emitted from this self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE) process have a relative bandwidth ΔE/E0 ≈ 0.2%, with a pulse duration of a few to several tens of femtoseconds (TABLE 1). Diagnostics and beam manipulation provide ways to characterize and change properties of the X-ray free-electron laser (XFEL) beam, such as intensity or photon flux, beam position or pointing, X-ray spectrum, polarization, repetition rate, pulse duration and arrival time. (Not all these properties can be easily changed at every beamline at all XFELs.) X-rays from the undulator are conditioned by beamline optics, which typically include a monochromator (based on ruled gratings or Bragg crystals) and focusing mirrors. Narrower bandwidth (and higher spectral brightness) is achievable using self-seeding, whereby monochromatization is done upstream (between undulator segments), with further amplification in subsequent undulator segments. Samples are introduced at the focus of the X-ray beam, for instance, by using a liquid injector to replace the sample volume at the repetition rate of the X-ray pulses. Numerous spectroscopy techniques are based on the detection of fluorescent X-rays, including fluorescence-detected X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS). X-rays are collected (in the direction orthogonal to the beam propagation) and analysed by a spectrometer consisting of imaging optics and energy-selective elements (Bragg crystals for hard X-rays or dispersive ruled gratings for soft X-rays). b | Schematic of the XES and XAS spectral region (for a Mn compound170) showing the complementarity of the methods (left panel) and schematic of the RIXS spectrum (right panel). VtC, valence to core. Part a adapted with permission from REF.20. Part b adapted with permission from REF.170.

Diffraction limit.

The fundamental relationship between the size of a light source (D), the wavelength of the light (λ) and the divergence of the light beam (Δθ): Δθ ~ λ/πD.

Emittance.

Transverse emittance refers to the relationship between the angular spread (divergence) of an electron beam and the transverse size of the beam.

Bunch compression.

Condensing or squeezing the longitudinal (time) distribution of relativistic electrons in order to increase the peak current.

Self-amplified spontaneous emission (SASE).

Electrons propagating through periodic arrays of magnets exhibit transverse undulating motion, leading to X-ray photon emission. Over distances ~ 100 m, the X-ray field causes longitudinal microbunching of the electrons at the X-ray wavelength, causing positive feedback on the emission process.

Fluorescence yield.

The decay of core-excited states by emission of an X-ray fluorescence photon. X-ray fluorescence is a competitive process and its relative yield depends on the atomic number of the core-excited atom. In 3d transition metals, fluorescence decay dominates for K-edge excitation (31% for Mn, REF.68).

Background

The ability of transition metals to accept and donate electrons, at relatively low energy cost, puts them at the centre of many metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts. Among the 3d transition metals, those with unfilled 3d orbitals are of particular importance, as they are the most abundant in nature. (Of the 3d metals, Fe, Mn, Ni, Zn, Cu and Co are the most commonly used in catalysis. Only Zn has a full 3d shell and is usually not involved in redox processes.) Understanding the chemical function of 3d metals is essentially understanding their 3d electronic structure and bonding. X-ray spectroscopy is a powerful probe of the 3d metal electronic structure as it probes, directly or indirectly, the binding energetics and the charge and spin states with element specificity. Given the substantial differences in the experimental approaches, we distinguish between soft X-ray (<1 keV) and hard X-ray (>5 keV) spectroscopy.

The large difference in absorption cross section and fluorescence yield between soft and hard X-ray spectroscopy also has important practical consequences for the application of both approaches. Here, we will focus on photon-in photon-out spectroscopy methods for both hard and soft X-rays, as they are widely applicable and most commonly used for probing chemical reactions of metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts in solution (we note that soft X-ray spectroscopy is also performed in electron and ion yield modes).

Importantly, moving from a synchrotron to an XFEL requires rethinking experimental approaches, with new challenges and opportunities present. As described in a recent review, many of the pioneering experiments at the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV)/soft X-ray FEL, FLASH, which started user operation in 2005, addressed this issue and, thereby, laid the foundation for the methods discussed here4. An important issue that was identified and persists to date is that of X-ray-induced sample damage. A critical question that has to be addressed for each experiment is how to obtain useful information about the sample without the influence of damage.

The standard approach at a synchrotron (in which damage typically arises from average X-ray exposure5) is to cryogenically cool the sample to reduce the mobility of radicals created by ionization from X-rays. However, doing so precludes studies under functional conditions. Moreover, although the cryogenic technique with frozen samples works for hard X-rays, it is not suitable for soft X-ray spectroscopy studies on metalloenzymes. Even with cryo-cooling, soft X-rays induce radiation damage too rapidly, owing to their higher absorption cross section and the larger Auger electron yield. SR studies of metalloenzymes at room temperature are almost impossible in the soft X-ray energy range, although recent advances in sample delivery approaches allow some serial measurements at SR sources in the hard X-ray regime6–10.

Counter-intuitively, the very high peak power of XFEL pulses provides a critical advantage over synchrotrons, opening the door to studies of metalloenzyme samples at room temperature with both hard and soft X-rays. XFEL pulses are so short (~10–50 fs) that they can essentially outrun the sample damage caused by the diffusion of solvated electrons or radicals by probing the sample and getting useful information before the onset of damage. This concept is known as ‘probe-before-damage’ or ‘probe-before-destroy’. The limits above which damage-induced changes in a biological sample would compromise diffraction data have been estimated11. Subsequently, probe-before-destroy was first shown to work experimentally for diffraction12, for X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) of solutions of manganese complexes13 and for soft X-ray spectroscopy of metalloenzymes14. It is now the standard approach for studying many samples at XFELs and for characterizing metalloenzymes and sensitive chemical materials, including molecular catalysts, under ambient and functional conditions in real time.

The work described in this Technical Review directly relies on this critically important probe-before-destroy approach. However, for successful execution, several additional experimental challenges must be addressed. First, because XFEL pulses often do destroy the sample, tailored methods of sample delivery and environment are required to replace the sample after each pulse15–19. Second, the stochastic nature of the SASE XFEL pulses causes complex spectral and temporal pulse profiles and significant shot-to-shot spectral, temporal and intensity fluctuations, requiring specialized diagnostics and spectroscopy instrumentation20–23. Third, it is possible to study the functional changes in metal centres in real time of the reaction with a pump–probe approach, in which a visible laser pump pulse or a trigger such as temperature or a chemical and/or substrate initiates the reaction, and an XFEL pulse probes the atomic and electronic structure as a function of the pump–probe delay time. This method requires shot-to-shot spatial and temporal pump–probe synchronization, spectral and spatial beam diagnostics, detection and data processing. Fourth, the interaction of intense XFEL pulses with matter may create new physical phenomena that need to be understood to properly interpret the data. We discuss examples of such nonlinear phenomena and their potential future applications in the last section of this Technical Review.

Photon-in photon-out spectroscopy.

X-ray spectroscopic methods that separately detect photons incident on the sample (photon-in) and photons leaving the sample (photon-out), to measure the spectroscopic observable. Examples include X-ray absorption spectroscopy in transmission and fluorescence yield mode, X-ray emission spectroscopy and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering.

Auger electron yield.

The decay of core-excited states by emission of an Auger electron. Auger decay is a competitive process and its relative yield depends on the atomic number of the core-excited atom. In 3d transition metals, Auger decay dominates for L-edge excitation with a minor fluorescence decay channel (0.5% for Mn, REF.68).

Stimulated emission.

The process by which an incident photon of a given energy (or wavelength) triggers an electronic transition in an excited atom or molecule to a lower electronic state, resulting in an emitted photon with the same wavevector, energy and phase as the incident photon.

Fourier transform limit.

The lower limit of the duration of a time pulse with a given frequency spectrum. This is based on the fundamental Fourier transform relationship between a time-dependent function and its frequency spectrum, and the lower limit implies a frequency-independent spectral phase.

Seeding.

In laser physics, a process in which a signal (typically from a weak laser) is injected into a gain medium (typically from a strong laser) to improve the output signal by stabilizing the wavelength and reducing variations in the output pulse energy and timing (jitter).

In this Technical Review, we describe how addressing these four challenges will create new opportunities at the current and the next generations of XFELs for spectroscopy of metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts. We first describe the basics of XFELs and their present-day capabilities. We then address hard X-ray and soft X-ray spectroscopy in turn, before discussing the capabilities that will be available in future facilities. Although, presently, there are only a few XFELs in operation, there is a steady worldwide growth of capacity. With new high-repetition-rate XFELs, such as the European XFEL and LCLS-II (Table 1), this capacity increase and the enhanced capabilities of XFELs will be further accelerated. We are optimistic that the explosive growth seen in synchrotron-based research over the last several decades is an indicator of what can be expected from XFEL-based research in the future, and X-ray spectroscopy of metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts will be a key research area and at the heart of this progress. We also want to direct the readers to several recent special issues of journals that provide a broad collection of specialized reviews on this topic24–28.

Table 1 |.

Characteristic parameters of the various X-ray free-electron laser facilities worldwide (adapted from REF.169)

| Location | Facility name | Photon energy (keV) | Pulse lengtha (fs) | Pulse energyb (mJ) | Repetition rate (Hz) | Flux (ph s−1)f | Start of operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | SACLA BL2,3 | 4–20 | 2–10 | 0.1–1 | 60 | 2–9 × 1013 | 2011 |

| SACLA BL1 | 0.04–0.15 | 60 | 0.1 | 60 | 3–9 × 1014 | 2015 | |

| Italy | FERMI FEL-1 | 0.01–0.06 | 40–90 | 0.08–0.2 | 10 (50) | 1–6 × 1015 | 2010 |

| FERMI FEL-2 | 0.06–0.3 | 20–50 | 0.01–0.1 | 10 (50) | 1–5 × 1014 | 2012 | |

| Germany | FLASH1 | 0.02–0.3 | 50–200 | 0.03–0.5 | (1–800) × 10c | 0.08–1 × 1018 | 2005 |

| FLASH2 | 0.01–0.3 | 50–200 | 0.03–0.3 | (1–800) × 10 | 0.05–2 × 1018 | 2015 | |

| Korea | PAL-XFEL | 2.5–15 | 5–50 | 0.8–1.5 | 60 | 0.4–2 × 1014 | 2016 |

| 0.25–1.2 | 5–50 | 0.2 | 60 | 0.6–3 × 1014 | 2016 | ||

| Switzerland | SwissFEL | 1.8–12.4 | 10–70 | 1 | 100 | 0.5–3 × 1014 | 2017 |

| 0.2–2 | 10–70 | 1 | 100 | 0.3–3 × 1015 | 2021 | ||

| Germany | European XFEL-SASE1,2 | 3–25 | 10–100 | 2 | 2,700 × 10d | 0.1–1 × 1017 | 2017 |

| European XFEL-SASE3 | 0.2–3 | 10–100 | 2 | 2,700 × 10 | 0.1–2 × 1018 | 2017 | |

| USA | LCLS | 0.3–12 | 2–500 | 2–4 | 120 | 0.03–1 × 1016 | 2009 |

| LCLS-II | 1–25 | 10–100 | 2–4 | 120 | 0.1–3 × 1015 | 2022e | |

| LCLS-II | 0.2–5 | 10–200 | 0.02–1 | 106 | 0.04–1 × 1019 | 2022e | |

| LCLS-II-HE | 0.2–13 | 10–200 | 0.02–1 | 106 | 0.01–1 × 1019 | 2026e |

Estimated pulse length (full width at half maximum) based on e-bunch length measurement or designed range.

Rough estimates of pulse energy, particularly for projects that are currently under construction.

Burst mode operation at 10 Hz, with each macropulse providing up to 800 bunches at 1 MHz.

Pulsed mode operation at 10 Hz, with each macropulse providing up to 2,700 bunches at 5 MHz.

Projected project completion dates.

Flux (photon s−1) is based on the combination of maximum pulse energy and repetition rate, and the range reflects the range of photon energies available from that source. Note that, for LCLS-II and LCLS-II-HE, the pulse energy (as a function of repetition rate) is constant up to ~300 kHz, and scales inversely with repetition rate above ~300 kHz.

Sources, properties and new capabilities

XFEL sources and properties.

Whereas optical lasers rely on the quantum process of stimulated emission in a gain medium, typically through multiple passes within a cavity, XFELs amplify coherent electromagnetic radiation using a single pass of relativistic GeV-scale electrons propagating through a very long undulator29,30 (FIG. 1). This SASE mode generates femtosecond coherent X-ray pulses, at multi-gigawatt peak powers and wavelengths spanning from tens of nanometres to below 1 Å (photon energies of hundreds of eV to above 10 keV). Thus, the peak brightness of XFEL pulses is ~109 times higher than that of current synchrotron X-ray pulses. The XFEL facilities FERMI31, LCLS20, SACLA32, PAL-XFEL33 and SwissFEL34 (Table 1) use normal conducting pulsed radio frequency accelerator technology operating at repetition rates in the 10–120-Hz range. FLASH35 and the European XFEL36 facilities use pulsed superconducting accelerator technology, creating a burst mode of pulse trains at 10 Hz, with each macropulse comprising up to 800 (FLASH) or 2,700 (European XFEL) pulses. The new XFELs now under development (LCLS-II37 and LCLS-II-HE38 in the USA, and SHINE in China) use continuous-wave superconducting radio frequency accelerator technology, providing high repetition rates with uniform or programmable time distributions. The first of these facilities (project name LCLS-II) is scheduled to start operation in 2022, delivering soft and tender X-ray pulses up to 5 keV (2.5 Å) at repetition rates up to 1 MHz (REF.37). In the second phase38, the X-ray range will be extended beyond 12 keV (1.0 Å). Other performance enhancements identified by the rapidly growing XFEL user community and demonstrated to date include ultrashort (<1 fs) X-ray pulse generation and characterization39,40, temporal coherence (near the Fourier transform limit) via seeding and related schemes41–48, and versatile operating modes such as two-colour multi-pulse sequences43,46,49–54, and large coherent bandwidth55. These enhancements, and the fact that the capacity and access to XFELs and lab-based femtosecond sources is growing worldwide56, will strongly benefit the science enabled by the X-ray spectroscopy and scattering techniques we review in the next section.

Time-dependent X-ray spectroscopy and scattering using an XFEL.

Using ultrabright femtosecond XFEL pulses for X-ray spectroscopy (the X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), XES and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) methods described in BOXES 1 and 2) has created an enormous potential for time-dependent, operando studies of ultrafast dynamics and chemical reactions of metal complexes. The most common approach uses an optical laser pump pulse to initiate the chemical process and an XFEL pulse to probe it. The measurement is repeated at varying time delays between pump and probe to create a sequence of spectra or scattering patterns that reflect the temporal evolution of the system after excitation. Such sequences, sometimes called ‘molecular movies’, provide a way to follow reactions as they proceed. Critical to the success of this approach is the property of femtosecond XFEL pulses (described in the introduction to this Technical Review) to probe the system before destroying it. Femtosecond XFEL pulses are so short that they can outrun the diffusion of ions, radicals and electrons created by the interaction of X-rays and the sample, which is the main cause of the various forms of radiation damage observed at synchrotron facilities in molecular and biological catalysts5. Therefore, cryo-cooling is not required in XFEL experiments13,57. The combination of high peak power and ultrashort duration of XFEL pulses enables efficient probing of dilute species of catalysts in solution with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. Radiation-sensitive molecular catalysts and metalloenzymes in solution are now routinely studied in XFELs to probe their steady states14 and to capture intermediates that occur on slow58,59 and ultrafast timescales60–62. However, at sufficiently high peak power, highly focused XFEL pulses start to create nonlinear effects that change the linear X-ray spectra63–67. These nonlinear phenomena and the magnitude of these effects on linear X-ray spectra critically depend on the experimental conditions, such as X-ray wavelength, pulse duration and sample concentration.

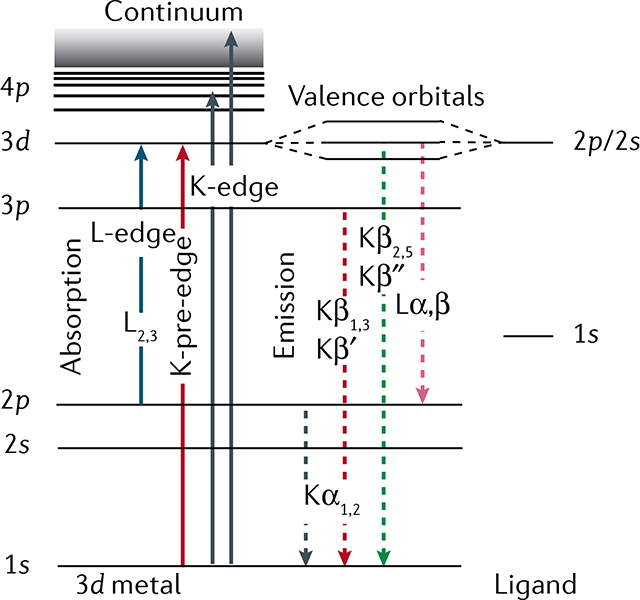

Box 1 |. Absorption and emission X-ray spectroscopy.

In general, X-ray spectroscopy is used to characterize electronic and geometric structures of elements in their chemical environment172, but in this Technical Review, we focus on 3d transition metals. X-ray spectroscopy is element-selective because the binding energies of core electrons are specific to each element173. It is sensitive to the chemical environment, which imposes small shifts on these binding energies174,175. By tuning the incident energy to a resonance, X-ray spectroscopy exhibits orbital specificity89,120,176,177. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) probes the electronic transitions from ground to core-excited states, whereas X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) probes the fluorescence decay of core-excited states. The panel below shows a generalized energy-level diagram for 3d transition-metal systems for hard and soft X-ray spectroscopy. XAS and XES are complementary techniques providing information about local metal oxidation states, valence orbital populations and interactions, local metal spin states, ligand coordination, bond lengths and symmetry changes, and metal–ligand covalency.

XAS probes the transitions of a core electron to empty or partially unoccupied molecular orbitals, with symmetries given by the dipole selection rule176–180. K-edge XAS (hard X-rays) probes predominantly unoccupied molecular orbitals with p symmetry via 1s → 4p transitions. In the K-pre-edge region, weak quadrupolar 1s → 3d transitions can be observed, which gain intensity through mixing with orbitals with p symmetry. L-edge XAS (soft X-rays) predominantly probes the orbitals with d symmetry via 2p → 3d transitions. These transitions relate to the low-energy region of an XAS spectrum (first few eV in the soft X-ray range and first few tens of an eV in the hard X-ray range), also called the X-ray absorption near edge structure region. At higher energies (tens to hundreds of eV) is the extended X-ray absorption fine structure region, which is dominated by scattering processes. In this case, the energy of the X-ray photons liberate photoelectrons that propagate from the absorber atom and are backscattered by neighbouring atoms, producing interferences and the characteristic extended X-ray absorption fine structure oscillations181. This signal provides information about the atomic number, distance and coordination number of the atoms surrounding the metal absorber atom.

XES probes the transitions of an electron from an occupied orbital to an unoccupied or partially occupied core orbital182. These transitions result from spontaneous fluorescence decays of core-excited states reached by X-ray absorption of the system. Non-resonant K-edge XES (Kα, Kβ1,3, Kβ′, Kβ2,5 and Kβ˝), where the excitation energy is well above the core electron binding energy, provides information on the metal oxidation state, effective spin, metal bonding orbitals and nature of the ligand. L lines in XES of 3d transition metals and K lines in XES of ligand atoms such as N or O provide sensitivity to oxidation states, symmetry, energies and interactions of occupied orbitals, and metal–ligand covalency.

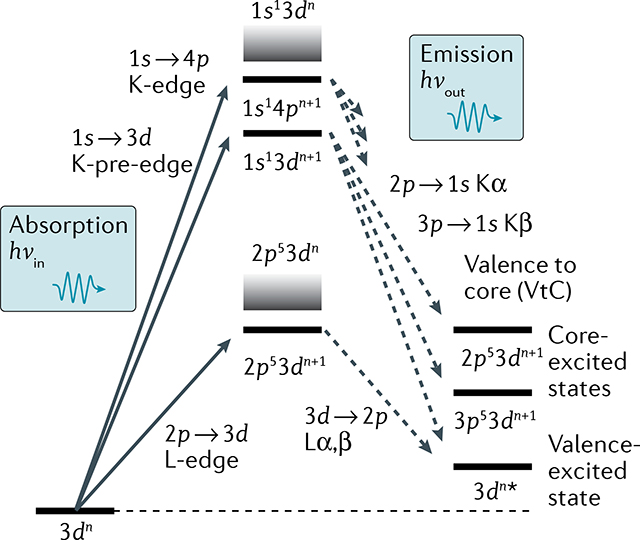

Box 2 |. Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering.

Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) is a multidimensional X-ray spectroscopy offering enhanced electronic structural information81,122,183,184. In RIXS, the energy of photons scattered/emitted by the sample is measured with high spectral resolution, while the incident photon energy is scanned across the absorption edge. The corresponding 2D spectrum shows the incident photon energy versus that transferred to the sample, defined as the difference in incident and emitted/scattered photon energies. This energy transfer is in the range of meV to eV for soft X-ray RIXS, corresponding to vibrational and valence-electronic d–d transitions, and up to several 100 eV for hard X-ray RIXS, corresponding to resonant core–electron transitions. RIXS is the X-ray analogue of resonance Raman scattering and provides the ability to probe the occupancy and interactions of both occupied and unoccupied orbitals in valence-excited and core-excited states.

In 1s RIXS, the incident hard X-ray energy is scanned across the K-pre-edge exciting 1s electrons to unoccupied 3d-derived valence orbitals, where 1s → 3d transitions lead to 1s13dn+1 intermediate states and 2p53dn+1, 3p53dn+1 or 3dn⋆ final states, respectively122 (see panel). Therefore, 1s RIXS probes 2p → 3d (similar to L-edge absorption), 3p → 3d (similar to M-edge absorption) or valence–electron transitions, with the advantages of hard X-rays.

In 2p3d RIXS, the incident soft X-ray energy is scanned across the L-edge, exciting 2p electrons to unoccupied 3d-derived valence orbitals, where 2p → 3d transitions lead to 2p53dn+1 intermediate states and 3dn⋆ final states122,185. The energy transfer corresponds to valence–electron transitions of ultraviolet–visible (UV/Vis) absorption, with the advantages of using an element-specific, chemical-site-specific and orbital-specific X-ray probe. 2p3d RIXS offers several additional advantages over UV/Vis absorption spectroscopy: it reveals d–d or ligand-field (LF) excitations over much wider energy ranges often hard to access with UV/Vis spectroscopy (down to below 1 eV and up to several 10 eV). LF or charge-transfer excitations can be selectively enhanced by resonant excitation, allowing to probe LF excitations unmasked from potentially overlapping charge-transfer transitions and solvent absorption that often dominate UV/Vis spectroscopy. Finally, due to spin–orbit interaction in the 2p-excited intermediate states, 2p3d RIXS allows probing transitions that are formally spin-forbidden in UV/Vis spectroscopy122,185,186.

Soft X-rays with typical absorption cross sections of ~10−17 to 10−18 cm2 and incident fluence of >1017 photons cm−2 within a core-hole lifetime (~4 fs for low-Z elements68,69) lead to an appreciable probability of instantaneous nonlinear effects. This corresponds to peak power densities >1015 W cm−2 at 500 eV. A hard X-ray study67 discussed the effects of high peak power and sample concentration on the X-ray emission spectra of Fe samples of varying concentrations. XFELs based on superconducting linacs, such as the existing European XFEL and the future LCLS-II, with kHz to MHz repetition rates with the same or smaller pulse energies compared with existing low-repetition-rate XFELs, are ideally suited for the traditional X-ray spectroscopy data collection. In some cases, however, nonlinear X-ray phenomena can be exploited to reveal information that is unavailable from linear X-ray spectroscopy, which is an area of active research.

Finally, the XFEL-based pump–probe approach has led to some important experimental changes in hard X-ray spectroscopy as compared with its long-standing use at synchrotron sources. To analyse the emitted or resonantly scattered (photon-out) spectrum at an XFEL, dispersive X-ray optics, where the whole spectrum is recorded in a shot-by-shot approach, are most commonly used13 (BOXES 1 and 2). In hard X-ray spectroscopy, non-resonant XES above the metal K-edge has proven very valuable to early XFEL applications60,70. The technique does not require monochromatic X-rays, which has the advantage that it can use the full SASE XFEL pulse, and it can be simultaneously applied with X-ray scattering and diffraction, two techniques that provide complimentary atomic structure information57,59,71.

Hard X-ray spectroscopy at XFELs

Hard X-ray spectroscopy techniques have been widely used for studying molecular catalysts and metalloenzymes at SR facilities. To avoid X-ray-induced changes, data are often collected at cryogenic temperature, meaning that only the chemical states that can be trapped by a freeze-quench method are accessible. There have also been various efforts in recent years to collect data at room temperature using jet and micro-fluidics systems6–10,72, and these often benefitted from sample delivery approaches initially developed for XFEL experiments. At XFELs, the ability to collect X-ray data at room temperature, that is, free from X-ray-induced changes, has advanced mechanistic studies of catalysis, by providing a way to follow a reaction as it proceeds. Among several reaction triggers, so far, photochemical pump–probe methods are most often carried out at XFELs, and have provided a way to capture chemical and structural changes at various time delays as short as tens of femtoseconds. The vast majority of catalytic reactions, however, proceed by substrate binding at catalytic sites. Such reactions proceed at much slower rates, due to diffusion-limited processes of substrates. In this case, it is the advantage of the probe-before-destroy nature of ultrashort XFEL pulses that allows capturing the population shift of reaction intermediates, thus, enabling the untangling of the sequence of events at reaction conditions without the requirement of cryo-cooling.

Oxidation states.

The oxidation state of an atom in a compound describes the degree to which the electron number of an atom has changed compared with the uncharged neutral form of the same atom. In case of redox reactions of first-row transition metals, these changes happen in the 3d shell; hence, the oxidation state is directly related to the number of 3d electrons present.

Spin states.

In transition-metal complexes, the spin state refers to the distribution of electrons in the valence shell. Often, there are two distributions possible for the same number of electrons: low-spin or high-spin configurations, having a low or a high number of unpaired electrons, respectively.

Although soft X-ray L-edge spectroscopy is a more direct probe of the 3d transition-metal electronic structure, the hard X-ray regime offers several practical advantages, as experiments under ambient pressure conditions and on bulk materials are facilitated, due to their larger penetration depth. Furthermore, the shorter hard X-ray wavelengths (~1–2 Å) are comparable to atomic distances, allowing simultaneous scattering/diffraction experiments that provide structural information at atomic resolution. Below, we describe examples of time-resolved XES and XAS experiments (FIG. 2) and multimodal experiments using combinations of spectroscopy and diffraction measurements with hard X-rays (FIG. 3).

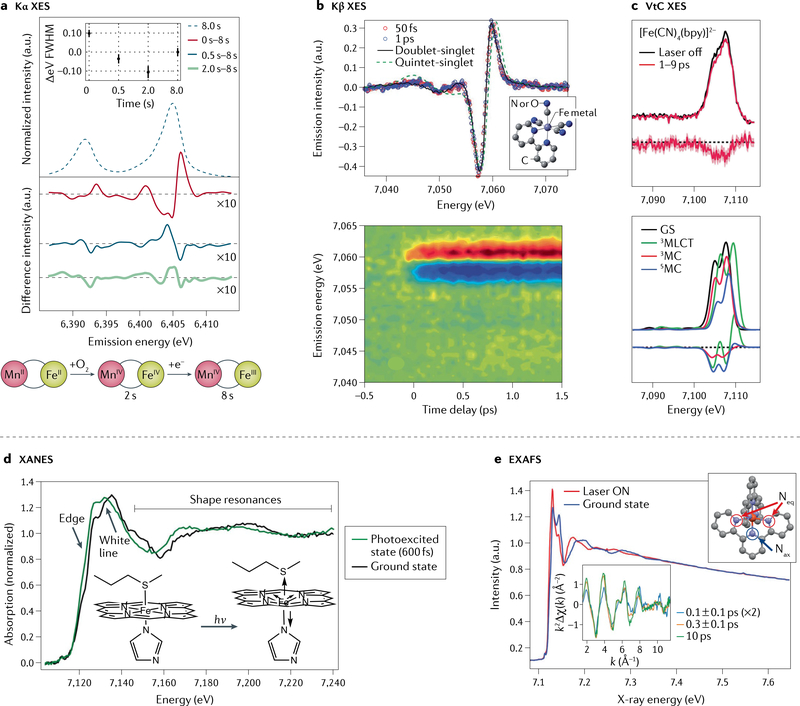

Fig. 2 |. Hard X-ray spectroscopy at X-ray free-electron lasers.

a | Fe Kα X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) of solutions of Fe/Mn containing ribonucleotide reductase R2c measured at room temperature prior to O2 incubation, and changes observed after 0.5, 2 and 8 s in situ O2 incubation. The change in spectral shape and full width at half maximum (FWHM) indicates, first, formation of a FeIV intermediate (within ~2 s), followed by the catalytically active FeIII state (schematic). b | Transient Fe Kβ XES difference spectra of Fe(CN)4(bpy) (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine; structure in inset) at 50 fs and 1 ps after photoexcitation and the calculated difference involving either a doublet metal–ligand charge transfer (MLCT) or a quintet metal-centred excited state (top). The contour plot (bottom) shows light-induced changes of the XES up to 1.5 ps after excitation. The spectra indicate that, likely, only one excited state is present and the MLCT state fits the data best. c | Transient Fe valence-to-core (VtC) XES of Fe(CN)4(bpy) (top) and calculated spectra (bottom), showing light-induced changes in the picosecond time range due to photo-oxidation and ligand dissociation. d | Time-resolved X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of cytochrome c before and 600 fs after light excitation. The changes in the edge position and the shape resonances were interpreted as an out-of-plane motion of the haem Fe coupled with a loss of the Fe–S(Met) bond (inset). e | Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of Fe(terpy)2 (terpy = 2,2′:6′,2˝-terpyridine, structure in right inset, with equatorial (Neq) and axial (Nax) nitrogen atoms indicated) in the ground state and after excitation (“Laser ON”). The k2 weighted difference EXAFS modulation (k2Δχ(k)) as plotted in k-space (bottom inset) indicates light-induced changes in the Fe–ligand distances on the sub-picosecond timescale. k, photoelectron wavevector. Part a adapted with permission from REF.18. Part b adapted with permission from REF.75. Part c adapted with permission from REF.84. Part d adapted with permission from REF.60. Part e adapted with permission from REF.95.

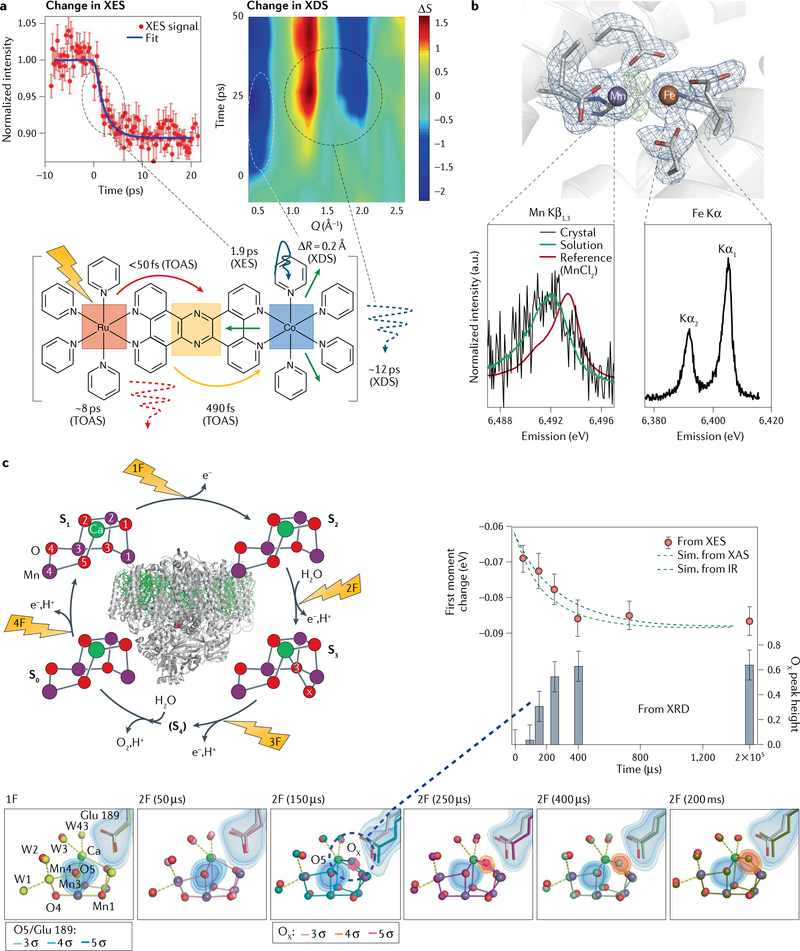

Fig. 3 |. Multimodal detection methods in X-ray free-electron laser studies using hard X-rays.

a | Measurements of femtosecond time-resolved Kα X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) (left) in parallel with X-ray diffuse scattering (XDS) (right) on a Ru–Co dyad (bottom). The kinetics of the XES show the conversion of the low-spin to the high-spin form of Co within 2 ps. At early times, the XDS data exhibit a strong dip in intensity (ΔS) at momentum transfer Q = 0.5 Å−1, indicating an expansion by 0.2 Å on the 500-fs timescale; a second feature at higher Q indicates thermal equilibration at ~12 ps. The schematic also contains information derived from transient optical absorption spectroscopy (TOAS) measurements, indicating ultrafast electron transfer from Ru to the bridge and transfer from the bridge to Co in under 500 fs. b | X-ray diffraction (XRD) in combination with Mn Kβ and Fe Kα XES of ribonucleotide reductase. The structure of the dinuclear metal centre found in crystals of oxidized ribonucleotide reductase is shown. Electron density is contoured at 1.2 s in blue. Omit density (green) indicates the position of the bridging oxygen atoms. The Mn Kβ spectrum obtained from crystals and solutions is shown, together with a calibration spectrum of MnIICl2 (bottom left); the Fe Kα spectrum of the crystals is shown on the bottom right. c | Combined XRD and XES studies on photosystem II. Left: the overall structure of the protein and the four-step catalytic cycle (Kok cycle), revealed by flashes 1F–4F. For each of the stable states S0, S1, S2 and S3, the XRD structure of the catalytic Mn4Ca cluster obtained from X-ray free-electron laser measurements is also shown, exhibiting a change in the distance between Mn atoms 1 and 4 (given in Å). Right: results from time-resolved XES and XRD measurements, together with kinetic simulations based on previous infrared (IR) or X-ray absorption (XAS) measurements. Bottom: XRD and XES data show concomitant Mn oxidation and insertion of a new oxygen (OX) in the Mn cluster on the 250-μs timescale during the S2 → S3 transition. The S1 state structure is shown in light grey and the different time point structures in various colours (yellow to olive). The electron density is contoured at 3, 4 and 5 σ around the O5 and OX atoms of the Mn cluster and Glu189, a critical mobile amino acid side chain. Part a adapted with permission from REF.99. Part b adapted with permission from REF.18. Part c adapted with permission from REFS58,59.

X-ray emission spectroscopy.

XES probes occupied states and can be performed off resonance with any incident photon energy above the absorption edge region of the absorbing metal (BOX 1), allowing the use of the full XFEL SASE pulse and combining the technique with scattering/diffraction. XFEL-based XES has been used widely to study changes in metal oxidation states and spin states of enzyme systems, including the haem Fe in cytochrome c (REFS60,61) and in myoglobin62, the Mn4Ca cluster in photosystem II (PS II) (REFS18,57–59,73), the dinuclear Mn–Fe site in ribonucleotide reductase (RNR)18 (FIGS 2a,3b) and the dinuclear Fe–Fe site in methane monooxygenase74. Numerous other photosensitive transition-metal complexes have been studied to understand the initial steps of photoexcitation and light-induced charge transfer, and the time-resolved XES provided detailed information about changes in the effective spin of the transition metal70,71,75–80 (FIG. 2b).

Although most XFEL-based XES studies have focused on the stronger Kα1,2 and Kβ1,3 XES lines, the weakest XES lines resulting from dipole-allowed valence-to-core transitions (VtC, also known as Kβ2,5 and Kβ”, see BOX 1 ) contain the most detailed information about the bonding and chemical environment of the absorbing atom81,82. Steady-state83 and time-resolved VtC-XES using an XFEL was reported84 (FIG. 2c). Comparing the observed spectral changes for three Fe(CN)-bipyridine compounds, recorded 0.2–50 ps after light excitation, with density functional theory calculations revealed the sensitivity of VtC-XES to bond length expansion. It was found that the integrated intensity of the VtC-XES spectrum is a measure of the metal–ligand bond length because it is primarily determined by the overlap of ligand valence orbitals with metal np orbitals. A decrease of intensity with increasing metal–ligand distance was observed. The spectra also showed signatures of photo-oxidation as measured by the energy position of the VtC-XES spectrum, where a blue shift was associated with increased oxidation state of the Fe centre. With further evidence of ligand dissociation for Fe(CN)6, and metal-centred triplet and quintet states for Fe(CN)4(bpy) and Fe(CN)2(bpy)2, where bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine, respectively, the study concluded that the metal–ligand bond length expanded by either 0.1 or 0.2 Å upon formation of the respective metal-centred triplet or quintet state on the sub-picosecond timescale84 (FIG. 2c).

X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

The X-ray absorption near edge structure region of XAS probes the unoccupied states via metal 1s → np transitions (see FIG. 1b and BOX 1 ) and, like XES, XAS can reveal details of ultrafast changes in the environment of transition metals in natural and synthetic molecules. Unlike XES, however, XAS measures changes of the absorption coefficient around the metal absorption edges and, therefore, requires monochromatized incoming X-rays to scan through a wide energy range (<50 eV for X-ray absorption near edge structure and >500 eV for X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), see BOX 1). To observe small spectral changes, the normalization of data at each incoming X-ray energy, considering the fluctuation of both incoming X-ray intensity and probed sample volume during the shot-by-shot experiments at XFELs is crucial. Energy-dispersive XAS using a wide energy range has also been described85. When using monochromatized beams, the flux is reduced by a factor of about 100 for SASE pulses, but much less when using self-seeded pulses.

XAS was used at an XFEL to observe the formation of a high-spin state ~160 fs after light excitation in a Fe–tris-bipyridine compound, indicating a metal–ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) state at very short times86. Fe K-edge XAS was also used to study the ultrafast photodissociation process of CO bound to the haem group in myoglobin87. Changes of the Fe K-edge energy and intensity were fit by two processes with characteristic times of 70 and 400 fs. The faster process was interpreted as being connected to an elongation of the Fe–N bond length in the haem, coupled to a shortening of the Fe–His bond. The slower process was interpreted as an iron out-of-plane motion coupled to the motion of the helix F of the myoglobin, being the first step in the observed protein quake. These spectroscopic results agree well with independently conducted time-resolved crystallographic experiments on the sub-picosecond timescale88. Interestingly, an XES study on the photodissociation of NO-bound myoglobin showed that, within 100 fs, a ligand-free triplet state is formed and that it takes about 800 fs to form a domed high-spin quintet state62.

Metal–ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) state.

MLCT excitations are special cases of charge-transfer excitations in metal complexes. MLCT excited states result from one-electron transitions in which an electron is promoted from a metal-centred to a ligand-centred orbital.

XAS is sensitive to structure and ligand environment because the metal 1s → np transition energies and intensities change when metal–ligand orbitals overlap and ligand fields (LFs) change89. Examples for other ultrafast XAS studies include measurements on Cu–phenanthroline90 or on Ni porphyrins91. It is possible to extend the amount of information that can be obtained by XAS studies by using polarized photoexcitation. The idea is to exploit the fact that optical excitation in metal complexes is often anisotropic and, by using different relative polarizations of the optical pump and X-ray probe beams, it is possible to select different sub-ensembles of differently excited species. Polarized cobalt XAS studies on a cobalamin derivate, for example, showed that structural changes upon photoexcitation of the corrin ring occur mainly in the ring plane first along one direction at 19 fs and then in the perpendicular direction of the ring 50 fs later. These changes are followed by the elongation of the axial ligands on a 200–250-fs timescale, and the internal conversion to the ground state occurs on a 6.2-ps timescale. These results describe the features that influence the reactivity, stability and deactivation of electronically excited cobalamins92,93.

To obtain very precise measurements of distance changes of the ligands of transition-metal systems, EXAFS is an essential tool in SR studies. The EXAFS region of XAS was successfully collected at XFELs94,95. Precise signal normalization to the incoming beam intensity and the probed sample volume is critical when measuring the subtle changes in EXAFS spectra. This was achieved by recording the forward scattering signal from the solvent for each shot and using it for signal normalization. Time-resolved EXAFS with delay times of 0 to 600 fs and 10 ps on a solution of Fe(terpy)2, where terpy stands for 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine, showed a 0.2-Å change in the Fe–ligand distance between the ground state and the excited state, and revealed an intermediate spin state in the laser-induced low-spin (LS) to high-spin (HS) transition on the 100-fs timescale95 (FIG. 2e). In the HS final excited state, all Fe–N bonds were found to be expanded by ~0.2 Å. The intermediate state was best explained by expansion of the equatorial Fe–N bonds by 0.15 Å, while the axial Fe–N bonds did not yet expand95.

Multimodal measurements.

Combining complementary techniques leads to a more complete picture of the local changes of a transition metal site during a reaction. An example is the use of both XAS and XES to study the weak covalent bond between the haem Fe and an S-methionine (S-Met) ligand present in cytochrome c (REF.60). The presence of this bond ensures that the Fe stays in its LS state in both FeII and FeIII oxidation states. Loss of the S-Met bond changes the functionality of cytochrome c. The bond can be broken by laser excitation, after which it quickly reforms. 600 fs after excitation changes in the XAS spectrum indicate a change from a six-coordinate LS to a five-coordinate HS Fe configuration, including loss of the S-Met ligand and elongation of the His–Fe bond length (FIG. 2d). The sensitivity to structure and ligand environment with XAS was complemented with Kβ XES, which gives access to the metal spin state (number of unpaired electrons in the metal-derived 3d orbitals). This provided a 6.1-ps time constant for re-formation of the LS state and a 6.4-ps time constant for heat transfer out of the haem. The study shows that the Fe–(S-Met) bond enthalpy is stronger in the presence of protein constraints, demonstrating how biological systems use subtle differences in energetics to control chemical function of transition-metal systems60. An XES and XAS study on ferric cytochrome c found that haem-doming is also occurring in ferric haems upon photodissociation of bound ligands and results from populating HS states61.

It would be ideal to use multimodal techniques, simultaneously, to minimize systematic errors potentially introduced by varying conditions from each separate experiment, such as varying sample conditions or varying time zero of the optical pump and the X-ray probe. The combination of XES from two different metals18,96–98 or XES with scattering/diffraction is well suited for this approach, as the incident X-ray energy can be freely selected (as long as it is above the absorption edge). We provide examples below of the simultaneous use of these techniques.

A study99 combined XES with X-ray diffuse scattering to monitor the ultrafast electron transfer in a Ru–Co dyad following excitation with a femtosecond pump laser (FIG. 3a). The dyad used is a representative model for many synthetic and natural photocatalysts, with a distance between the electron donor (Ru) and the acceptor (Co) of about 13 Å. While Co Kα XES was used to follow the changes in oxidation state of the Co centre and, hence, the kinetics of electron transfer, the X-ray diffuse scattering signal was used to follow structural changes in the dyad. The Kα XES, in addition to transient optical absorption spectra, revealed that the electron transfer occurs in a two-step mechanism with initial formation of a LS Co(II) species (500 fs) and subsequent conversion to a HS Co(II) within 2 ps. The simultaneously recorded X-ray scattering also revealed a fast change in the Co binding environment by 0.2 Å and showed that charge separation is faster (~2 ps) than the thermalization of the excitation energy with the surroundings, which was observed at around 12 ps (REF.99).

Another example of measurements of XES and XRD was done on Mn/Fe containing RNR18. In this case, XRD and XES of both Mn and Fe were measured, simultaneously, on crystals of RNR in the aerobic MnIIIFeIII state, confirming the oxidation state of the metal centres and showing the undamaged structure of the active site at room temperature (FIG. 3b).

The prime example for the simultaneous use of XES and XRD is the series of studies on PS II crystals57–59,100. PS II is a metalloenzyme that catalyses the light-driven oxidation of water to molecular oxygen in a four-step reaction cycle (FIG. 3c) and has been widely studied using XFELs (REFS57–59,100–105). The catalytic site contains a Mn4CaO5 cluster embedded in the large protein complex. Each step is driven by the absorption of one photon and the Mn4CaO5 cluster acts as a site of charge accumulation to finally catalyse the oxidation of two molecules of water to release molecular oxygen, four protons and four electrons. Samples such as PS II, which are very sensitive to radiation, are extremely difficult to study under functional conditions with X-rays106, but, as discussed above, the ultrashort XFEL pulses can outrun the damage they cause. Combined XRD and XES studies initially confirmed that the Mn4CaO5 cluster in PS II is in an intact, non-reduced state in the microcrystals used for the diffraction measurements57. Mn Kβ XES for the four stable intermediate states of the Mn cluster58 indicated proper in situ turnover of the PS II enzyme under the illumination conditions and allowed to estimate the population of each of the intermediate states in the sample. The XRD obtained in parallel showed that the Mn cluster undergoes a structural rearrangement in the S2 to S3 transition that consists of a widening of the cluster and insertion of an additional oxygen bridge between Mn and Ca to form a Mn4CaO6 cluster, different from earlier results at lower resolution103,104 and confirmed by a second independent study105. Subsequent time-resolved data collection of both XES and XRD59 revealed the time constant of this transition to be around 300 μs based on the XES data and showed that several amino acid residues in the vicinity of the Mn4CaO5 cluster first undergo structural changes, followed by an expansion of the metal cluster and subsequent insertion of the new oxygen bridge. Based on XES, it was possible to conclude that Mn oxidation and insertion of the new oxygen occur concomitantly59 (FIG. 3c).

Soft X-ray spectroscopy at XFELs

Soft X-ray spectroscopy of metalloenzymes and molecular catalysts at XFELs has the advantage of directly probing the local electronic structure of 3d transition metals via the dipole-allowed 2p → 3d transitions at the metal L-edge. The tunability and high intensity of the soft X-ray XFEL radiation are essential to address the dilute metal species in solution. The femtosecond duration of the XFEL pulses is necessary for avoiding X-ray damage and collecting time-resolved spectroscopy data, and this defines the two classes of applications we discuss (FIG. 4). The first is where high-valent metal sites in inorganic molecular complexes and metalloenzymes are studied with L-edge XAS (FIG. 4a–c). In this case, the high-valent metal species are probed with femtosecond pulses before X-ray-induced damage of the sample sets in. The second is time-resolved 2p3d RIXS, without X-ray-induced damage, where the femtosecond resolution in optical pump and X-ray probe experiments gives access to the frontier–orbital interactions in short-lived reaction intermediates (FIG. 4d–i). In this case, RIXS is used to probe ligand-field (LF) and charge-transfer (CT) transitions during molecular transformations and in excited-state dynamics. All examples are photon-in photon-out experiments on liquid samples, relying on the bulk sensitivity of the respective method. Liquid jets are used to prepare the solution samples in the vacuum environment necessary for soft X-rays with fast sample replenishment to avoid X-ray-induced sample damage from consecutive X-ray pulses. Many of the early soft X-ray investigations at XFELs aimed at proving that undistorted signals of intact samples could be measured (REF.4 and references therein). Although, in this Technical Review, we focus on homogeneous transition-metal catalysts, we note that there are other important applications of soft X-ray spectroscopy at XFELs in surface science and heterogeneous catalysis107–111, in photochemistry of small molecules and organic systems in solution112,113, and in the gas phase114–116

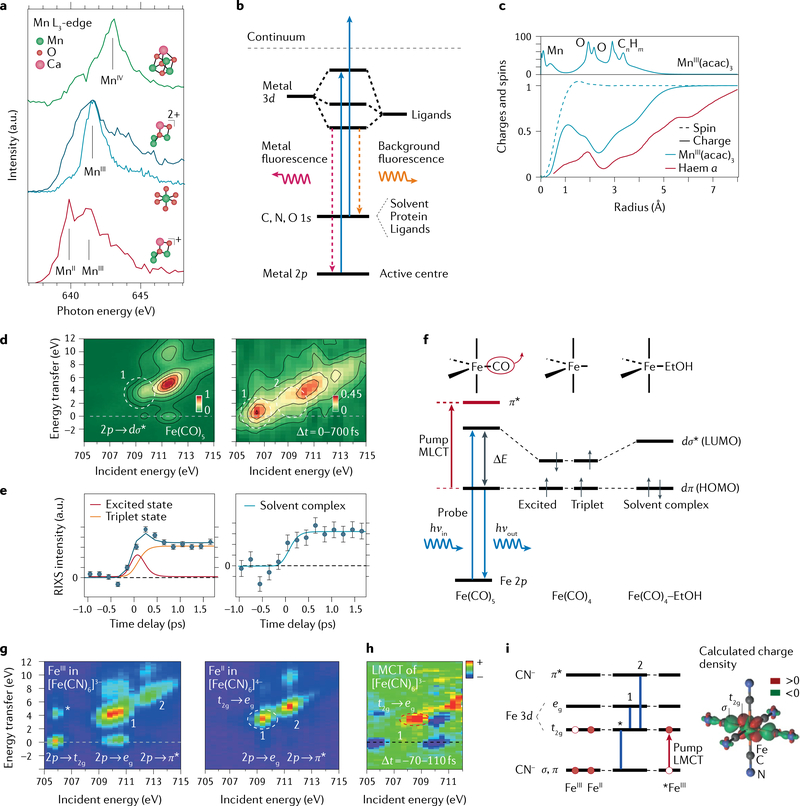

Fig. 4 |. Soft X-ray spectroscopy at transition-metal L-edges with X-ray free-electron lasers.

a | Mn L-edge absorption spectra (L3-edge partial fluorescence yield spectra) and structures of non-cubane reduced MnIIMnIII2CaO(OH) (red), non-cubane oxidized MnIII3CaO(OH) (dark blue), closed-cubane MnIV3CaO4 (green, measured in solution, Mn concentrations 6–15 mM) and of MnIII(acac)3 (light blue, measured in solution, Mn concentration 100 mM). b | Energy-level diagram for metal-specific L-edge partial fluorescence yield absorption spectroscopy. c | Top: calculated electron charge density in MnIII(acac)3 (acac = acetylacetonate) as a function of distance from the Mn centre. Bottom: accumulated electron charge and spin densities upon reduction of MnIII(acac)3 and haem a as a function of distance from the Mn and Fe centre, respectively. d | Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) intensities as a function of incident photon energy at the Fe L3-edge and as a function of energy transfer for Fe(CO)5 (left) and averaged for pump-probe delay times of 0–700 fs after optical excitation of Fe(CO)5 (right, measured in solution, Fe concentration 1 M). e | Integrated RIXS intensities as a function of the pump–probe delay time for regions 1 and 2 as marked in part d, with a kinetic model (solid lines) relating measured RIXS intensities and populations of fitted species. f | Energy-level diagram for RIXS at the Fe L3-edge of Fe(CO)5 with optical excitation (metal–ligand charge-transfer (MLCT) excitation initiating dissociation to Fe(CO)4) and frontier–orbital energies and populations in excited-state and triplet-state Fe(CO)4 and Fe(CO)4-ethanol (EtOH) solvent complexes (dπ and dσ denote Fe-centred 3d-derived orbitals of π and σ symmetry, respectively). g | RIXS intensities at the Fe L3-edge of ferric (FeIII) and ferrous (FeII) iron hexacyanide Fe(CN)6 (as measured in solution, Fe concentrations 0.5 and 0.33 M, respectively). h | RIXS intensity differences (pumped minus unpumped) averaged for pump–probe delay times of −70 to 110 fs after optical excitation of FeIII-cyanide, representative of the ligand–metal charge-transfer (LMCT) state, measured in solution with Fe concentration 0.3 M. Integration is for −70 to 110 fs because the temporal resolution in the experiment was 180 fs; saturated intensities are shown for better visualization. i | Energy-level diagram in octahedral (Oh) symmetry for FeIII-cyanide and FeII-cyanide and the LMCT state of ferric hexacyanide (*FeIII) with main RIXS transitions (*, 1 and 2 as indicated in parts g and h and calculated electron charge density difference between LMCT *FeIII-cyanide and FeIII-cyanide (LMCT minus ground state)). HOMO, highest occupied molecular orbital; LUMO, lowest occupied molecular orbital. Part a adapted with permission from REFS14,117. Part c adapted with permission from REFS117,171. Part d adapted with permission from REF.120. Part e adapted with permission from REF.120. Part g adapted with permission from REF.124. Parts h and i adapted with permission from REF.125.

Ligand-field (LF) and charge-transfer (CT) transitions.

The valence orbitals in metal complexes can often be classified as either being metal-centred (large amplitude on the metal) or ligand centred (large amplitude on one or several ligands). LF and CT transitions are electronic excitations in metal complexes. LF excitations, often also denoted d–d excitations, refer to one-electron transitions between metal-centred orbitals. CT excitations correspond to one-electron transitions between metal-centred and ligand-centred orbitals.

Partial fluorescence yield XAS.

Measuring fluorescence as a function of incident photon energy is often denoted partial fluorescence yield X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and it usually applies to soft X-rays.

X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

The Mn L-edge XAS study14 in FIG. 4a exemplifies the use of XFELs for probe-before-destroy spectroscopy at room temperature of solutions of high-valent Mn species in inorganic complexes and in PS II. The motivation is to study high-valent metal sites in inorganic molecular complexes and metalloenzymes at functional conditions (room-temperature solution) in order to relate their reactivity to the probed electronic structure. Successful implementation of such experiments requires specialized liquid-jet sample delivery, intense femtosecond X-ray pulses and an efficient soft X-ray spectrometer for partial fluorescence yield XAS. Low-consumption liquid jets are needed to prepare the often precious and dilute solutions with typical metal concentrations in the millimolar range16. The femtosecond pulse length is essential to avoid photoreduction and probe the sample before ions, radicals and electrons created by the ionizing soft X-ray radiation in the solvent, ligands or protein environment reduce the high-valent metal centres. As the level diagram in FIG. 4b shows, incident X-rays tuned to metal L-edges also ionize non-resonantly, light elements (C, N, O) in the sample (solvent, protein, ligands), followed by emission of their characteristic X-ray fluorescence. Efficient soft X-ray spectrometers are necessary to discriminate the metal fluorescence of interest from this light-element fluorescence background.

High throughput is essential to address the low (millimolar) concentrations of metals in inorganic catalysts and metalloenzymes. The successful implementation of the example in FIG. 4a at the LCLS XFEL shows that these requirements can all be met. The spectra of the high-valent MnIII and MnIV complexes in FIG. 4a do not contain significant amounts of the most reduced MnII state as present in the mixed-valent MnII–MnIII compound (peak around 639.5 eV). The spectra shift to higher energies with increasing Mn oxidation state, with a blue shift of 1.5–2 eV per unit increase of oxidation state. The investigation also included the Mn L-edge measurements of two states of the water oxidation catalyst Mn4CaO5 in PS II solution and the measured PS II spectra consistently shift, on illumination, to higher oxidation state14. This establishes probe-before-destroy soft X-ray spectroscopy at XFELs and opens the door to a new way of probing the electronic structure in inorganic catalysts and metalloenzymes at functional conditions in room-temperature solutions with soft X-ray L-edge spectroscopy.

Future prospects of X-ray L-edge spectroscopy include gaining more detailed insight into how the metal L-edge XAS spectrum probes charge and spin densities at high-valent metal sites. Quantum-chemical calculations indicate that the local charge at the metal site does not change considerably with changing oxidation state117,118, and the examples in FIG. 4c illustrate this. For the reduction of both the simple MnIII(acac)3, where acac stands for acetylacetonate, complex and the much larger iron haem a complex, the displayed calculations show that the additional charge density effectively spreads over the whole molecule, whereas the added spin density accumulates locally at the metal centre. Relating such calculations of charge and spin density distributions with measured L-edge XAS spectra as done in REF.117 for MnIII(acac)3 (see FIG. 4a for the spectrum of MnIII(acac)3) has led to a new understanding of metal L-edge XAS. With future developments in ab initio theoretical descriptions of the electronic structure and X-ray spectra119, in particular, the ability to describe multinuclear metal centres, a detailed understanding of charge and spin density changes in the redox reactions of inorganic compounds and metalloenzymes will be accessible with soft X-ray L-edge spectroscopy at XFELs.

Charge and spin densities.

Each electron as a particle carries one unit of charge and one unit of spin (alpha/spin up or beta/spin down). in the ensemble averages as described by quantum-chemical calculations, however, charge and spin density distributions in a metal complex or in the active centre of a metalloenzyme can differ, in that alpha (spin up) and beta (spin down) electrons are differently distributed in space.

Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering.

The essence of the optical pump and X-ray probe experiment is depicted in FIG. 4d–f: (REF.120): a MLCT excitation induces dissociation of a ligand from Fe(CO)5 in solution and creates the reactive intermediate Fe(CO)4 (FIG. 4f). As the Fe–CO bond breaks and new bonds are formed in the course of the reaction, covalent metal–ligand interactions change. This process was probed with time-resolved Fe 2p3d RIXS (for the ab initio calculations of X-ray spectra used to assign species; for more details, see REFS89,120–122). The RIXS intensities in FIG. 4d are plotted as a function of incident energy (hvin) versus energy transfer (ΔE = hvin − hvout). The encircled maxima are most informative and they are due to Fe 2p → LUMO(dσ⋆) transitions with inelastic scattering to final states, where ΔE corresponds to HOMO-LUMO (dπ → dσ⋆) excitations (FIG. 4f). ΔE decreases from Fe(CO)5 to Fe(CO)4 as covalent metal–ligand interactions and the HOMO-LUMO energy difference decrease (marked 1 in FIG. 4d, Fe(CO)4 is the most abundant species at pump–probe delays of 0–700 fs). Consistently, as the LUMO energy decreases, the Fe 2p → LUMO(dσ⋆) resonance red shifts. 2p3d RIXS, therefore, probes bonding at the Fe centre via the HOMO-LUMO (dπ → dσ⋆) LF transitions. They are selectively probed and resonantly enhanced by tuning the incident photon energy to the Fe 2p → LUMO (dσ⋆) resonance. A parallel pathway was also observed in which an ethanol solvent molecule attaches to the Fe centre in Fe(CO)4 to form an Fe(CO)4–EtOH solvent complex. This is seen in the RIXS measurement with intensities marked 2 in FIG. 4d: HOMO-LUMO excitation energies are increased compared with 1 because forming the bond in Fe(CO)4-EtOH partially restores the covalent Fe–ligand interactions and pushes apart the HOMO and the LUMO (FIG. 4f, the 2p → LUMO resonance energy is increased consistently as the LUMO energy is increased). In the discussion here, the different spin states of Fe(CO)4 (singlet excited state and triplet, FIG. 4f) are not distinguished in that they both contribute to the circled region 1. However, they can be distinguished by when they arise in the reaction, and the integrated RIXS intensities plotted versus time delay (FIG. 4e) are a measure of how the populations of singlet excited state and triplet Fe(CO)4 (1) and the Fe(CO)4–EtOH solvent complex (2) change over time. The combination of femtosecond 2p3d RIXS with ab initio calculations revealed that the reactivity of the transient intermediate Fe(CO)4 in terms of binding molecules is determined by the population of the LUMO (dσ⋆) orbital120. When it is populated, as in singlet excited state and triplet Fe(CO)4, ligand-to-Fe σ donation is impeded and these species are unreactive (do not bind any molecule) on the probed timescales. Fe(CO)4–EtOH, in turn, is formed by binding ethanol to singlet ground-state Fe(CO)4, which has an empty LUMO orbital and is formed by electronic relaxation. It will be interesting to see in future applications of 2p3d RIXS at XFELs how this approach can be used to understand, and, ultimately, control, the reactivity of new photocatalytic systems in solution.

HOMO-LUMO.

In molecular-orbital theory, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are frontier orbitals of molecules.

Ligand–metal charge-transfer (LMCT) excited state.

LMCT excitations are special cases of charge-transfer excitations in metal complexes. LMCT excited states result from one-electron transitions in which an electron is promoted from a ligand-centred to a metal-centred orbital.

10Dq.

The ligand-field splitting energy separating eg and t2g orbitals in coordination compounds with octahedral (Oh) symmetry.

Building on earlier L-edge XAS work at SR sources123, the studies on iron hexacyanide Fe(CN)6 in solution in FIG. 4g–i exemplify how time-resolved 2p3d RIXS at XFELs can be used to map transient charge distributions124,125. In contrast to the former example, the molecule stays intact, but valence-orbital occupations change. The 2p3d RIXS intensities for ferric (FeIII) and ferrous (FeII) hexacyanide (FIG. 4g) demonstrate how RIXS reflects valence-orbital occupations in the ground states of the two compounds (valence configurations of the Fe-centred orbitals are t2g5eg0 for FeIII-hexacyanide and t2g6eg0 for FeII-hexacyanide, both with octahedral, Oh, symmetry). The hole in the t2g orbital in ferric FeIII-hexacyanide (FIG. 4i) gives rise to a 2p → t2g resonance that is missing in ferrous FeII-hexacyanide, whereas both compounds exhibit 2p → eg and 2p → π⋆ resonances. 2p3d RIXS in this example probes the t2g → eg LF transitions (marked 1 in FIG. 4g–i) and the t2g → π⋆ CT transitions (marked 2 in FIG. 4g,i). By tuning the incident photon energy, the LF (1) or CT transitions (2) can be resonantly enhanced (evidently, ligand σ/π to t2g excitations only appear in FeIII-hexacyanide, marked ⋆ in FIG. 4g,i). FIGURE 4h shows how the Fe 2p3d RIXS intensities change when going from the ground state to the ligand–metal charge-transfer (LMCT) excited state of FeIII-cyanide, as generated by optical excitation. Femtosecond resolution was needed here to catch the transient intermediate LMCT state. As can be seen in the calculated charge densities in FIG. 4i, where charge decreases on two ligands and charge increases at the Fe centre, LMCT excitation of FeIII-hexacyanide promotes an electron from a ligand σ orbital to the Fe-centred t2g orbital, resulting in the LMCT excited-state configuration ⋆FeIII t2g6eg0. In the time-resolved RIXS measurement, the signatures of ground-state FeIII-hexacyanide decrease (blue in FIG. 4h, the 2p → t2g resonance disappears in particular, as the t2g shell is filled) and the new intensities (red) characterize the LMCT ⋆FeIII excited state. Since both FeII-hexacyanide and LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide have the same t2g6eg0 configuration, these intensities measure the transient effect of the ligand σ hole (FIG. 4i). In LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide, the 2p → eg resonance (1) is redshifted by 1 eV compared with FeII-hexacyanide, and this indicates that the 2p core-hole is better screened in the XAS final states of LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide. This stabilization of the 2p core-excited states indicates that the charge density locally at the Fe is higher in LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide compared with FeII-hexacyanide. Indeed, calculations confirm that the ligand σ hole in LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide induces an increase of charge density at Fe (REF.125). Calculations also suggest that this charge increase is due to an increase of ligand-to-Fe σ donation. This strengthens the Fe–ligand bond and increases the LF strength 10Dq (REFS125,126). 2p3d RIXS measures this by an increase of the t2g → eg transition energy of 0.3 eV in LMCT ⋆FeIII-hexacyanide compared with FeII-hexacyanide (1, FIG. 4g,h). Such detailed insight into transient charge distributions made accessible by time-resolved 2p3d RIXS could prove essential in the development of efficient photocatalysts by probing, for example, the effects of manipulating ligands in metal complexes to control excited-state dynamics127 or by resolving the CT dynamics between metal complexes and solid-state surfaces in dye-sensitized semiconductor devices.

The element-specific, site-specific and orbital-specific access to photochemical reaction mechanisms as demonstrated in these experiments enables correlating orbital symmetry and interactions, spin multiplicity and reactivity of metal compounds in solution. In future applications, this ability promises unique insight into the photochemical reaction dynamics of fundamentally important metal complexes, functional photocatalysts and dilute bioinorganic systems. High-repetition-rate XFELs, such as the European XFEL and LCLS-II, will enable systematic soft X-ray spectroscopy of functional systems in solution at the millimolar concentration level at metal L-edges with XAS and 2p3d RIXS.

New capabilities and methods at future XFELs

In the previous two sections, we focused on linear X-ray spectroscopy methods, in which the response of the signal of interest is independent of the X-ray intensity. Nonlinear X-ray spectroscopy accesses new aspects of matter, where the response depends on the X-ray intensity. These new forms of X-ray spectroscopy build upon the developments in nonlinear optics,and offer qualitative new scientific insights through element specificity, atomic spatial resolution and sub-femtosecond time resolution. In the following, we highlight a few emerging nonlinear X-ray spectroscopy methods that are particularly promising for a deeper understanding of molecular catalysts and metalloenzymes. Note that this section is not a comprehensive coverage of the emerging field of nonlinear X-ray science that has been opened by XFELs, which includes advances in nonlinear scattering128–130, two-photon absorption131, second-harmonic generation132 and transient-grating methods133–135, to name a few.

Amplified spontaneous emission.

The spontaneous emission in an ensemble of atoms or molecules, the majority of which are in an electronic excited state. In this scenario, initial spontaneous emission events trigger subsequent stimulated emission events along the propagation path, and the resulting amplified spontaneous emission signal grows exponentially.

Seeded stimulated emission.

A variation of the stimulated emission process, in which the incident photon is provided in the form of a coherent pulse. Photons with a specific wavelength stimulate the emission of photons with that same wavelength.

Spontaneous emission.

The process in which an atom or molecule in an electronic excited state relaxes to a lower-energy electronic state through the emission of a photon.

Core-hole lifetime broadening.

The (homogeneous) energy broadening of a core transition due to the finite lifetime of the core-hole. For a Lorentzian line shape, this can be expressed as ΔEFWHMΔT1/e = 0.6589 eV fs, where ΔEFWHM is the full width at half maximum of the linewidth and ΔT1/e is the exponential lifetime (also referred to as dephasing time) of the corresponding core-excited state.

Stimulated XES: extracting VtC, Kβ, soft XES and other weak emission lines.

Spontaneous XES is a powerful element-specific probe, but is subject to relatively weak emission cross sections, and photons are emitted in all directions. Stimulating the emission offers three potential advantages: signals are emitted along a well-defined X-ray beam direction, enabling efficient collection of the entire signal; strong signal enhancements that can out-compete other decay channels; spectral narrowing and selective stimulation may result in enhanced chemical sensitivity.

Strongly enhanced stimulated Kα emission and RIXS has been observed in Ne gas136,137 and in 3d transition-metal systems138,139. The two main approaches are amplified spontaneous emission (ASE)136,138,139 and seeded stimulated emission137,138 (FIG. 5a). In ASE, an intense X-ray pump creates a population inversion along the propagation path. Spontaneously emitted photons along the population inversion path can stimulate the emission of additional photons at the same wavelength and direction (FIG. 5a), resulting in an ASE signal that grows exponentially. Kα ASE can be used for spectroscopy, as it exhibits chemical shifts and strong spectral gain narrowing139. To stimulate the spectroscopically more sensitive Kβ and VtC emission lines, a second-colour seed pulse is tuned to the respective energy (FIG. 5a). The seeding approach is required because Kα amplification always dominates the weaker Kβ lines.

Fig. 5 |. Examples of future X-ray free-electron laser-based nonlinear spectroscopy methods.

a | Level diagram of various transition-metal K emission lines (top left) and schematics of amplified spontaneous emission (top right) and seeded stimulated emission (bottom right). The pump pulse is tuned above the K-edge to create 1s core-hole excited states in the sample (red dots). In amplified spontaneous emission, a randomly forward emitted photon stimulates emission when encountering an excited atom, leading to amplification along the path of atoms in the excited state, as created by the pump pulse. In seeded stimulated emission, the seed pulse energy is tuned to that of the emission line that one wants to enhance along the pump or seed pulse direction. Bottom left: single-shot seeded Kβ stimulated X-ray emission spectroscopy (S-XES) spectrum (red line) of NaMnO4 compared with conventional X-ray emission spectroscopy (XES) spectrum (blue line), showing the potential for spectral narrowing in S-XES. b | Level diagram and calculated valence-to-core (VtC) spectra in metal–ligand double-core-hole XES. Two photons from the X-ray free-electron laser pulse simultaneously create a double-core-hole (DCH) state, with one core-hole in the metal and one in the ligand. c | Calculated DCH spectra with N and Cl are compared with the conventional single-core-hole (SCH) VtC spectrum of MnII(terpy)Cl2 (terpy=2,2′:6′,2˝-terpyridine). d,e | Level diagram (part d) and representative calculated 2D X-ray core-hole correlation spectroscopy maps (part e) for the para and ortho isomers of aminophenol. The degree of orbital mixing of the N–2p and O–2p valence states gives rise to a nonlinear mixing of the polarizations associated with resonant excitation from the O–1s and N–1s core levels. The off-diagonal cross peaks (right map) indicate the enhanced mixing in the ortho conformation (effectively, mixing of the N–1s and O–1s X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra). Such quantum effects are absent in the para isomer due to the separation of the O and N atoms. f | Generalized schematic of X-ray core-hole correlation spectroscopy using a four-wave mixing geometry with a three-pulse sequence (k1, k2, k3). The signal of interest is the nonlinear polarization, kS, shown here resolved in frequency (energy) using a spectrometer. The other energy axis (ω12) is determined by the Fourier transform of the signal with respect to the time delays of the first two phase-locked pulses. Part a adapted with permission from REF.140. Parts b and c adapted with permission from REF.159. Parts d and e adapted with permission from REF.162.

Seeding of Kβ emission from a NaMnO4 solution with an enhancement of more than 105 compared with spontaneous emission into the same solid angle was reported140, with strong spectral narrowing (FIG. 5a). Although these studies were not performed under optimal conditions, they show that seeded stimulated emission is, potentially, a powerful tool. Besides the practical advantages of larger signal and outcompeting other decay channels, we envision using seeded stimulated emission to enhance individual spectral features characteristic of the electronic structure of a species of interest, while potentially decreasing the core-hole lifetime broadening. Tuning to resonant features at the absorption edge can widen this approach to stimulated RIXS137. The enhanced spectral sensitivity and control will widen XFEL-based spectroscopy to reveal subtle electronic structure changes that are currently below the detection limit. Such studies will include complex systems and ultrafast intersystem crossings in 3d metal centres of light-harvesting and photocatalytic molecules.

Metal–ligand double-core-hole spectroscopy.

An important challenge for photocatalysis is understanding coupled valence states (where metal and ligand orbitals mix) that mediate charge separation and reactivity. A powerful element-specific approach relies on the simultaneous creation of two core-level transitions in adjacent atoms, for example, one from a metal and one from a bonded ligand atom or metal (FIG. 5). Theoretical studies of the creation of such double-core-hole (DCH) states date back to 1986, when it was predicted that the binding energies associated with DCHs at different atomic sites of small molecules could sensitively probe the chemical environment of the ionized atoms141. Since then, most theoretical studies142–146, synchrotron experiments147–152 (where the DCH states were created by one photon ejecting two core electrons) and XFEL experiments153–158 (where two photons create the DCH state) have focused on probing the chemical environment of atoms in small gas-phase molecules.

The application of DCH spectroscopy to 3d transition-metal compounds has been discussed in a theoretical study of VtC-XES in mononuclear Mn complexes and binuclear Co complexes with metal–metal direct bonds159. For the mononuclear Mn complexes, the VtC-XES signals of the metal-1s/ligand-1s DCH states, and, for the binuclear Co complexes, the VtC-XES signals for the two-site Fe and Co 1s DHC states were calculated and compared with the conventional single-core-hole (SCH) VtC-XES signals. Figure 5b,c show the schematics of DCH VtC-XES and a comparison of the DCH and the SCH VtC-XES signals of these systems.