Summary

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals agenda calls for health data to be disaggregated by age. However, age groupings used to record and report health data vary greatly, hindering the harmonisation, comparability, and usefulness of these data, within and across countries. This variability has become especially evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when there was an urgent need for rapid cross-country analyses of epidemiological patterns by age to direct public health action, but such analyses were limited by the lack of standard age categories. In this Personal View, we propose a recommended set of age groupings to address this issue. These groupings are informed by age-specific patterns of morbidity, mortality, and health risks, and by opportunities for prevention and disease intervention. We recommend age groupings of 5 years for all health data, except for those younger than 5 years, during which time there are rapid biological and physiological changes that justify a finer disaggregation. Although the focus of this Personal View is on the standardisation of the analysis and display of age groups, we also outline the challenges faced in collecting data on exact age, especially for health facilities and surveillance data. The proposed age disaggregation should facilitate targeted, age-specific policies and actions for health care and disease management.

Introduction

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development has as a core principle: “leave no one behind”. This priority is reflected in the Sustainable Development Goals target 17.18, which calls for countries to increase the availability of data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability status, geographical location, and other characteristics relevant in national contexts.1 Although standard stratification of some of these variables has already been well defined,2 age groupings frequently differ across indicators and across programme-based or project-based priorities, in ways not directly related to biological or common age-dependent societal factors. The lack of standardised age disaggregation results in multiple cutoffs being used, both across and within countries, to report on mortality, morbidity, health behaviours, risk factors, and coverage and quality of health interventions, hampering the analysis, interpretation, and comparison of data across indicators. The use of standard age disaggregation would greatly improve the usability and comparability of data across and within countries and regions, and over time.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in massive, rapid, cross-country analyses of reported cases, but the variations in age groupings have made these analyses difficult, highlighting the urgent need for standardised age categories for reporting. The recent Lancet Commission on adolescent health and wellbeing,3 the UN declaration of the Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021–2030,4 and the Titchfield Group data on ageing-related statistics and age-disaggregated data5 strongly encourage data disaggregation to make adolescents and older people more visible and to inform actions to improve their wellbeing. Given the role of the UN agencies and the mandate of WHO in setting standards for reporting health data, clear recommendations for standard age disaggregation for health statistics by these agencies are important.

In this Personal View, we provide a justification for age groupings based on biological, developmental, and common societal factors, as well as for disease prevention reasons, and propose a modification to existing recommendations to include a finer age disaggregation under the age of 5 years. The focus of this Personal View is on the standardisation of the analysis and display of age groups. However, because this disaggregation is influenced by what age data are collected, we also address the importance of recording exact ages or, when such is not possible, the smallest possible strata.

Why is standard age disaggregation important?

The life-course approach to health regards health and wellbeing as being determined by the accumulation of risk and protective factors, encountered at different stages of life, that can have additive or multiplicative effects.6 Some risk and protective factors change with age and need to be addressed at the age at which they are most relevant.7 However, the use of various age groupings to analyse or display health data makes cross-country comparisons challenging—or, at times, impossible—limiting the ability to determine which countries are making progress in improving survival and maintaining health and wellbeing throughout the life course. Within countries, different age groupings can be used over time and vary by conditions (eg, cancer and tuberculosis) and service providers, complicating the ability to monitor health trends, or to understand the burden of disease or good health in different age groups. These difficulties impede the identification of meaningful correlations among various factors and limit the capacity for quantitative programme evaluations, to assess causal inference, and to pinpoint best practices.

Although recording exact age at the point of care is very important, after data are aggregated, analysed, and displayed, standard age categories for health statistics would help ministries of health to analyse and display data in a more coherent and age-sensitive manner, with clearer messages for action. Finally, standard age categories can be used to guide analysis, monitoring, and planning when a new health condition or disease emerges in a population.

What is the evidence of the problem?

COVID-19 surveillance data provide a current example of the problems arising from the lack of standard age disaggregation. As the world struggles with the pandemic, determining the factors that place individuals at a high risk of infection, morbidity, and mortality has become imperative.8 Age continues to be of crucial importance, especially in relation to the risk of severe disease and death.9 COVID-19 death rates are substantially higher among older people.10, 11 Some countries report COVID-19 surveillance data from children younger than 5 years, but many others report only data for children grouped under the age of 10 years.12, 13, 14 In adults, large age aggregations can span more than 10 years., Partly due to this absence of standard age disaggregation, more than 1 year after the beginning of the pandemic, much is not yet fully understood about COVID-19 in infants, children younger than 5 years, or school-aged children, especially regarding transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in these groups. Similarly, determining the best age cutoff to prioritise who should first receive the COVID-19 vaccination in adults has been challenging because of the lack of age-disaggregated data. Monitoring vaccine uptake and effects on susceptible groups, including by age group, will be essential to tailor vaccination strategies and understand rare adverse events.

The issue of the lack of standardised age disaggregation in health data is not new. Countries use a plethora of age groupings when reporting health data. For example, the overall cancer incidence rates for the UK are displayed in 5 year age groups, whereas in the USA, infants (children younger than 1 year) are a separate group, followed by the 1–4 year age group, and then by 5 year age groups.15, 16 Unlike the UK age grouping, the US grouping provides specific information on infant cancers, which can often have a prenatal origin.

Standard age categories are especially important for the collection of data on risky health behaviours and their outcomes, providing more information to inform policies and support prevention programmes for groups at risk. Yet, a comparison of smoking data across countries shows wide variations in age categories used. In Australia, smoking prevalence by age group has been reported for the ages of 18–24 years, followed by 10 year age groups up to 75 years of age. In Canada, the age groups (in years) used are 12–17, 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and 65 years or older. In Thailand, 5 year age groups are used between the age of 15 years and the age of 75 years.17, 18, 19 The age groupings used in Australia and in Thailand result in the loss of information on smoking rates in young adolescents (aged 10–14 years), a group that is at particular risk. Large categories might also mask key differences in smoking rates by age: Canada's age distribution, for example, assumes that smoking rates are similar for people aged 18 years and for people aged 32 years, and that smoking rates in people aged 65 years are similar to those in people aged 90 years.

Even the presentation of mortality data from civil registration and vital statistics varies: age cutoffs often do not distinguish between neonates and infants and instead report on mortality in all children younger than 1 year. To follow trends, age groups are sometimes aggregated into larger groups, such as 15–24 years of age—although the burden of disease, risk behaviours, and programmes to address these factors would not be the same for someone under the age of 19 years and for someone older than 21 years. Furthermore, the oldest age group displayed varies with life expectancy in individual countries.20, 21, 22

What is the current commonly recommended age disaggregation for health data?

In 2001, WHO recommended that groupings for the age standardisation of incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates took into account the rapid and continued declines in age-specific mortality rates among older people, and the increasing availability of epidemiological data for this group.23 To do so, WHO adopted an average age-structure of the world population for the period of 2000–25 based on the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division assessment in 1998. The recommendation at that time was to use 5 year groups from birth up to the oldest reached age (100 years or older).23 Although this recommendation has remained the suggested standard since then, it has not been universally applied.

Further complicating the recommendations, the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistical Division's standards for age disaggregation vary by health indicator and by country. There are ongoing debates as to what standard should be generally recommended for health data.24 For example, given the extensive and rapid changes in development, prevalence of health conditions, and risk behaviours in children, a further refinement of the 5 year age groupings for children should be considered.

What should be the minimum standard age disaggregation for health data?

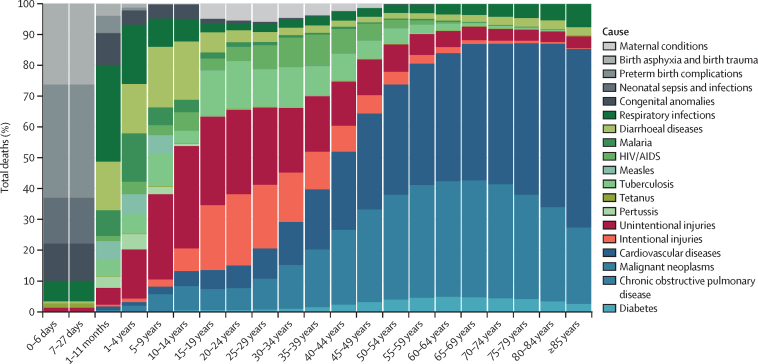

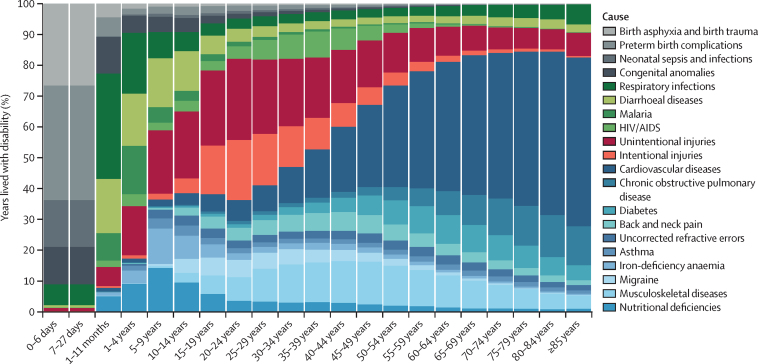

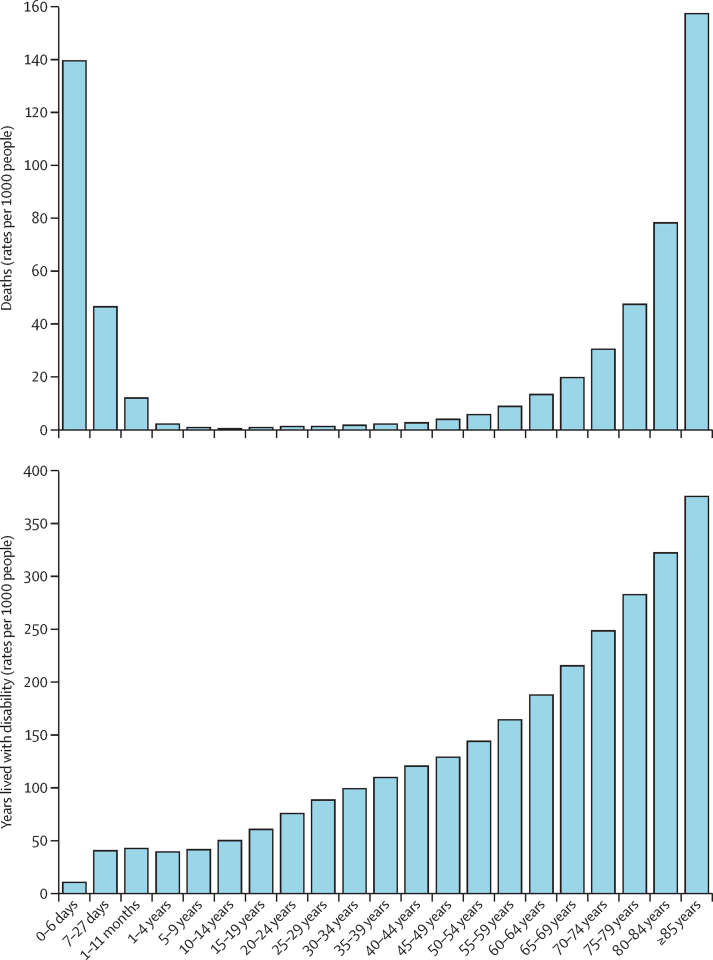

Patterns of disease burden and deaths can be used as a proxy for health needs and risks (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3) and can assist in defining what age disaggregation is best to monitor key health outcomes and health risks. Causes of disease burden change substantially across the life course, especially during childhood and adolescence. In addition, mortality rates and years lived with disability differ greatly for those younger than 11 months, justifying the need for more granular age groupings of health data for neonates and children younger than 5 years.25, 26 Additionally, there are biological, immunological, and developmental changes that occur over the life course—especially in childhood and adolescence—and that affect health outcomes later in life.27, 28, 29, 30 Finally, there are biological and physiological changes with increasing age that affect mental and physical capacities, with considerable variation at each age.

Figure 1.

Deaths by recommended standardised age groups in 201925

Figure 2.

Years lived with disability by recommended standardised age groups in 201925

Uncorrected refractive errors most commonly include myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism and presbyopia, which have not been treated with corrective glasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery.

Figure 3.

Age-specific death and years lived with disability rates per 1000 people by recommended standardised age groups in 201925

To establish a standard minimum for age disaggregation, we combined data on the disease burden caused by disability and deaths25 with information on biological, developmental, and common societal and environmental factors, and we provide some examples of health prevention and treatment programmes in which this age disaggregation would support decision making and planning (table). Taking these factors into consideration and carefully considering the reporting burden, we propose more nuanced groupings for younger ages, followed by 5 year age groupings for adults (table). This proposed age disaggregation would result in a set of 24 age groups, or 48 groups if disaggregated by sex.

Table.

Recommended standardised age disagregration groups for data analysis by life stage

| Recommended age grouping | Disease burden and health risk* | Examples of key prevention and health promotion interventions | Living conditions and societal factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early neonates | 0–6 days | A third of all neonatal deaths occur on the day of birth, and nearly 75% occur within the first week of life | Immediate breastfeeding; vaccination (eg, for BCG and hepatitis B) and screening for genetic, endocrine, and metabolic disorders at birth or within the first 24 h of life | Early neonates might be in facility care immediately after birth, especially if premature and low-weight or ill, but are most commonly cared for at home by family |

| Late neonates | 7–27 days | The first 27 days of life (neonatal or newborn period) are the most crucial for survival; neonates accounted for 2·5 million deaths (47% of all deaths under the age of 5 years) in 2019;31 causes of death in this age group differ from those in early neonatal and post-neonatal infants and a large proportion is due to congenital anomalies | Ensure neonates have received vaccines at birth, check weight, assess for birth defects, and promote the continuation of exclusive breastfeeding | Commonly cared for at home by family or caretakers |

| Post-neonatal infants | 28–364 days | The first year of life after the neonatal phase is the second riskiest period for child survival; about 24% of all deaths under the age of 5, in 2019, occurred in this age group,31 with pneumonia, diarrhoea, and malaria as leading causes of death | Completion of common vaccines schedule (diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, Haemophilus influenzae type b, hepatitis B, poliovirus, pneumococcal, rotavirus, measles-rubella, and two doses of seasonal influenza);32 continuation of breastfeeding with weaning and introduction of complementary foods when appropriate; long-lasting insecticidal nets and intermittent preventive treatment for infants in malaria-endemic countries | Commonly cared for at home by family, but can begin to go to day care |

| Young children | 1–4 years | This group has the greatest reductions in mortality of all age groups to date, but mortality in this group remains fairly high in many countries; environmental exposures during the first 3 years of life can affect a child's developmental trajectory and lead to an increased risk of physical and psychological illness, affecting health and wellbeing in later life27, 28, 29 | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles-rubella boosters and seasonal influenza vaccine;32 completion of weaning; long-lasting insecticidal nets and seasonal malaria chemoprevention in malaria endemic countries; early childhood programmes; environmental and policy interventions (eg, clean water and sanitation, fluoridation, safe playgrounds, and appropriate car seats) | Children can begin to attend preschool or day care and often play with other children |

| Older children | 5–9 years | This group is still subject to illness and death from common childhood causes but starts to have a higher risk of injuries, specifically from road traffic and drowning | Diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and measles-rubella boosters, seasonal influenza vaccine (some countries); environmental and policy interventions (eg, clean water and sanitation, fluoridation, safe playgrounds, appropriate car seats, and bike helmets) | Children begin attending school |

| Young adolescents | 10–14 years | In addition to road traffic injuries, leading causes of illness in this group are iron-deficiency anaemia, mental health disorders (eg, childhood behavioural disorders), drowning, and some infectious diseases (eg, pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases);33, 34 this group also includes the common age of puberty onset, when gender norms are fixed;35 cognitive developments in this period include increased capacity for abstract thought, and social and emotional development are often characterised by struggles with the sense of identity30, 35 | Common vaccine schedule for human papillomavirus (two doses) for girls or for both sexes (in some countries); sexual health education; educational interventions such as bullying prevention, physical education, mental health interventions, and nutritional education; key environmental and policy interventions such as for safe road traffic; alcohol and tobacco policies; road safety, safe place for exercise, and safe water and sanitation access | Young adolescents are generally in school |

| Older adolescents | 15–19 years | In this group, in which most physical changes of puberty are complete, self-harm, depression, anxiety, interpersonal violence among boys, and maternal conditions among girls become, in addition to road traffic injuries, leading causes of poor health outcomes;25, 34 risky behaviours emerge (eg, as drug and alcohol use), and while cognitive and socioemotional development continues, this group has an increased capacity for setting goals, interest in moral reasoning, and an increased interest in sexual activity30, 35 | Common vaccine schedule for human papillomavirus (three doses if not received earlier); promoting access to sexual health services such as contraception; screening for suicidal ideation and violence; promotion of mental health and prevention of ill mental health programmes at the school and community level; nutritional screening; educational interventions such as substance use prevention, bullying prevention, nutrition and physical education; key environmental and policy interventions (eg, seat belt policies, helmet use laws, alcohol and tobacco policies, road safety, safe space for exercise, and safe water and sanitation access) | Depending on the setting, older adolescence can be one of the phases in the life course with the most societal transitions; in some countries, older adolescents are in school or beginning employment, and in others they might be living independently and starting families; in many countries, a person's legal status changes at the age of 18 years |

| Young adults | 20–24 years | Protective and risk factors established during adolescence are often more pronounced during young adulthood, and although main causes of disease are similar to those of older adolescents, rates tend to be higher | Start of cholesterol and other non-communicable disease prevention screenings (eg, diabetes and blood pressure); screening for suicidal ideation and violence, and preventive mental health interventions | This period is often characterised by many important social transitions such as entry into the workforce, living independently, and for some, becoming a parent |

| Adults | 25–59 years, grouped in 5 year intervals | The risk profiles of different age groups vary across the life course and often within a 5 year age range; causes of death and years lived with disability change over time and are better captured by a 5 year age group disaggregation (figure 1); risk factors for chronic diseases are not equally distributed among adults36 (eg, the risk of heart disease is very different at 28 years and at 58 years; menopause commonly happens between the ages of 48 and 55 years37); in the second half of life, declines in physical and mental capacities are generally related to chronological age, but there are many variations at each group38, 39 | Cholesterol, diabetes, and blood pressure screening; first colonoscopy at the age of 50 years; mammograms for women older than 45 years, cervical screening for women as per country guidelines (depending on age and clinical history) | Age at which most people are active in the work force, become parents, and care for older parents as well as for young children |

| Older adults | 60–99 years, grouped in 5 year intervals, plus a category for people older than 100 years | In 2020, people older than 60 years made up 13·5% of the world's population (by 2030, one in six people will be older than 60 years and by 2050, this proportion will have increased to one in five people);40 many individuals experience gradual decreases in physiological reserves that result in an increased risk of many diseases due to accumulated risk over the life course (although not inevitable, most older people have a decline in physical and mental capacities); there is substantial variation at every age and changes are not linear nor consistent by chronological age:38, 39 for example, evidence suggests that the range of physical and cognitive capacities (measured by hand grip strength and delayed word recall) is far greater in older age;38, 41, 42 physical and cognitive decline-related rates of death increase dramatically after the age of 60 years, but years lived with disability vary significantly across 5 year age ranges (figure 2) | Pneumococcal and seasonal influenza vaccine; hypertension, obesity, malnutrition, cholesterol, and diabetes screening; colonoscopy every 10 years; mammograms for women every 2 years; cervical screening can be discontinued at the age of 65 years; electrocardiograms annual, cognitive annual, annual hearing loss, and annual visual impairment screening for people older than 65 years; prostate cancer screening for men as per national guidelines | In this stage, individuals undergo various social and economic transitions, although there is great variability: examples are shifts in social roles and positions, the need to deal with the loss of close relationships, changes in working life, different forms of contribution to the family, community, and society, changes in providing and receiving social and emotional support from family and friends, and changes in living arrangements (eg, due to changes in household structure or inability to age in place) |

Although not the focus of this Personal View, we recognise that equity and sex disaggregation of health data are important across all age groups43 and especially for adolescents, given the differences in top causes of deaths and years lived with disability by sex.44 Sex disaggregation is also important to differentiate women of reproductive age and for adults older than 60 years, considering the large differences in mortality rates by sex in this age group.

What are the challenges in collecting and reporting data using these age groups?

Currently, data to monitor disease trends come from several sources, such as population-based household surveys, routine information from medical records and health registries, civil registration and vital statistics systems, community-based systems, school health surveys, and disease surveillance systems. We strongly recommend collecting each individual's exact age, birth date, or both, although there might be barriers to doing so. There is much evidence that health-care workers are already overburdened with data collection and reporting, especially at the facility level, and capturing exact age might add to this burden.45 Additionally, in many low-income and middle-income countries, health information systems rely on inefficient processes for aggregating individual data from the facility level to national level. In low-income and middle-income country facilities, records are often kept on paper-based data capture forms; with a defined frequency (eg, monthly), these forms are tallied and summarised into the relevant aggregation groupings (eg, sex and age) before being reported to the district level (again, often on paper-based reporting forms). In many cases, these records are not digitised until they reach the district level, at which point the granular, disaggregated data have already been lost.46 Implementing age-specific recording, aggregation, and reporting (in addition to other important aspects) within current processes would result in exponential demands on the systems' human and information and communications technology capacity. To properly record and report these data, substantial resources are required to expand the use of electronic health records and registries, increase information and communications technology capacity, improve data architecture, digitise data recording, develop reporting processes, and build local capacity.

Other obstacles to collecting exact age include the fact that some individuals or people reporting information on behalf of others (particularly older people) might not know exact ages. This is especially true in low-income and middle-income countries, where many people have never had their births registered.47 Investing in and improving civil registration and vital statistics systems are crucial steps to overcome these obstacles. However, 80% of the world's population lives in countries that have either low-quality data or no data at all;48 improvements will therefore require large investments and probably take many years.

The age of consent for health services varies by country, so registering exact ages might, in some circumstances, hinder the ability of those under the age of consent to obtain services. The need to collect exact age versus the importance of providing health services must be considered as a factor in equitable access to services.

Finally, some age groups, such as older children and adolescents, adult men, and older individuals, are frequently not recorded in household health surveys, especially in low-income and middle-income countries.

When might disaggregation by other age groupings be appropriate?

Although we strongly advocate for the proposed age disaggregation (table), we recognise that larger aggregations or further disaggregation might be necessary, when justified, for the planning and action of health programmes, or on the basis of the natural history for specific diseases. Age ranges and the number of age groups may differ from one specific condition to another, based upon the burden of a specific disease and their specific risk factors, determinants, relevant policies, and programmes.

Rights-based approaches to health and specific international conventions might also require different cutoffs. One example is the UN's Convention of the Rights of the Child, which defines children as those younger than 18 years. In some countries, the age of entry into primary school might not align exactly with the proposed year groupings, which would result in some children not yet in school being aggregated with those who are.

Social factors, including eligibility for social benefits, might warrant additional disaggregation. In many countries, particularly high-income and middle-income settings, adolescents aged 15–17 years tend to be in secondary school, whereas those aged 18–19 years encounter, with the end of schooling, changes in legal rights, life circumstances, and relationships, which affect their health determinants, behaviours, and access to health-care services in ways that can only be understood if data are disaggregated. Similarly, for older individuals, retirement age and age of receipt of public health insurance benefits and living situations vary widely by country.

Finally, there can be methodological reasons to use different age groupings. For example, health surveys among adults aged 25–65 years might require large sample sizes to have sufficient precision and acceptable coefficients of variation to support subgroup analyses in 5 year age groups. If oversampling is not feasible, larger age groupings might be the only alternative. Also, 5 year age group disaggregation can result in very few numbers in some age groups (eg, people older than 85 years), increasing the possibility that individuals might be identifiable in some settings, which would violate data protection rights.

Although we propose general recommendations for a standard age disaggregation (panel) to update existing guidelines for health data collecting and reporting at the global level, we acknowledge that different disaggregation by age groups might be needed on the basis of local context, specific health programmes, policies, and specific diseases.

Panel. Recommendations for age disaggregation to report health data.

-

1

Collect exact age or birth date whenever possible, allowing for many different age groupings

-

2

Use the standard recommended age disaggregation when reporting on health data, especially when reporting on multiple diseases simultaneously, burden of disease, or a not previously recognised disease or condition

-

3

Disaggregate by sex, especially when differences by sex are important within specific age groupings

-

4

Consider deviations from these age groupings only when absolutely necessary, such as health service provision requirements, or in case of methodological or statistical limitations

How can these recommendations be implemented?

Addressing the various presentations of age-disaggregated health data among UN agencies, which vary and do not yet align with these recommendations, is essential. To do so, there is a need to support forums to increase engagement among UN agencies, international programmes that implement health surveys, national statistics offices, ministries of health, and the donor community to further refine the proposed age breakdowns and to facilitate endorsement of these age groupings. Designing standard templates and forms for collection of health data will be important, as will sharing best practices for collecting these age-specific data (while reducing the burden on health workers) and supporting investments in individual medical records, digital health management systems, civil registration and vital statistics, and age-reporting standards in population-based surveys.

To reach the Sustainable Development Goals targets for 2030, improving health across the life course requires regular reporting on standardised age disaggregation based on scientific evidence. Health data analyses that follow the proposed minimum age disaggregation should facilitate common information on age-specific health and disease and thus better inform public health action.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the recommendations from the following advisory groups for initiating this work and facilitating the review of draft manuscripts: Mother and Newborn Information for Tracking Outcomes and Results, Child Health Accountability Tracking Group, The Global Action for Measurement of Adolescent Health, and the Titchfield Group on Ageing-related Statistics and Age-disaggregated Data. We thank Amal Abou Rafeh, Angele Storey, Dakshitha Wickremarathne, Krishna Bose, Mariame Guèye Ba, Joanna Inchley, Sunil Mehra, Elizabeth Saewyc, Diana Yeung, Parviz Abduvahobov, and Carolina M Danovaro for review and input into at least one version of the manuscript.

Contributors

TD developed the concept with all authors and coordinated the inputs of all authors. BC provided data for the figures. KLS produced the figures. All authors made a substantial contribution to writing and reviewing and provided approval to submit the final version for publication. The authors alone are responsible for the contents of this Personal View, which does not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

References

- 1.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Goal 17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development. SGD Indicators Metadata repository. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/?Text=&Goal=17&Target=17.18

- 2.WHO Handbook on health inequality monitoring with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. 2013. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/gho-documents/health-equity/handbook-on-health-inequality-monitoring/handbook-on-health-inequality-monitoring.pdf

- 3.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387:2423–2478. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UN General Assembly . United Nations General Assembly seventy-fifth session. United Nations; New York, NY: 2020. Agenda item 131: global health and foreign policy. United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030)https://undocs.org/en/A/75/L.47 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Titchfield City Group on Ageing Report of the 2nd Technical Meeting of the Titchfield City Group on ageing and age-disaggregated data. June, 2019. https://gss.civilservice.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Report-of-the-2nd-technical-meeting-of-the-Titchfield-City-Group-11-12-June-2019.pdf

- 6.Kuruvilla S, Sadana R, Montesinos EV. A life-course approach to health: synergy with sustainable development goals. Bull World Health Organ. 2018;96:42–50. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.198358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu S. The life-course approach to health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:768. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan American Health Organization Why data disaggregation by age group is key during a pandemic? 2020. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52002

- 9.Sunil S, Bhopal R. Sex differential in COVID-19 mortality varies markedly by age. Lancet. 2020;346:532–533. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31748-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team Vital surveillances: the epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19)—China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020;2:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs World population ageing 2020 highlights. October, 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/files/documents/2020/Sep/un_pop_2020_pf_ageing_10_key_messages.pdf

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker—demographic trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#demographics

- 13.South Africa National Institute for Communicable Diseases COVID-19 update. 2020. https://www.nicd.ac.za/covid-19-update-61

- 14.Gobierno de Mexico Covid-19 México—Información General. 2020. https://coronavirus.gob.mx/datos

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Cancer Institute United States Cancer statistics: data visualizations. 2020. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/DataViz.html

- 16.Cancer Research UK Cancer incidence by age. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/age#:~:text=Children%20aged%200%2D14%2C%20and,males%20in%20this%20age%20grou

- 17.Australia Bureau of Statistics National health survey. 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2017-18~Main%20Features~Smoking~85#:~:text=For%20men%20aged%2018%2D24,age%2075%20years%20and%20over

- 18.Statistics Canada Smokers, by age group. 2018–2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009610

- 19.Aungkulanon S, Pitayarangsarit S, Bundhamcharoen K. Smoking prevalence and attributable deaths in Thailand: predicting outcomes of different tobacco control interventions. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:984. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7332-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Statistics Canada Leading causes of death, total population, by age group. 2015–2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310039401

- 21.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2018. January, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db355.htm

- 22.Department of Statistics South Africa Mortality and causes of death in South Africa: findings from death notification. 2017. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932017.pdf

- 23.Ahmad OA, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inoue M. World Health Organization; 2001. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard.https://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Data disaggregation and SDG indicators. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/iaeg-sdgs/disaggregation/

- 25.WHO WHO methods and data sources for country-level causes of death 2000–2019. December, 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/ghe2019_cod_methods.pdf?sfvrsn=37bcfacc_5

- 26.Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Ramos Rodriguez G, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e517–e528. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30145-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, Borja S. Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: a stress process analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;45:143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, Harris NB, Danese A, Samara M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ. 2020;371 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2:223–228. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UNICEF . UNICEF; New York, NY: 2020. Levels and trends in child mortality 2020.https://www.unicef.org/reports/levels-and-trends-child-mortality-report-2020 [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper. Nov 23, 2012. https://www.who.int/wer/2012/wer8747.pdf?ua=1

- 33.WHO Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): guidance to support country implementation. 2017. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255415/9789241512343-eng.pdf;jsessionid=119A9DCC303A580842EEADBDB715A9F9?sequence=1

- 34.Guthold R, White Johansson E, Mathers CD. Global and regional levels and trends of child and adolescent morbidity from 2000 to 2016: an analysis of years lost due to disability (YLDs) BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandra-Mouli V, Plesons M, Adebayo E. Implications of the global early adolescent study's formative research findings for action and for research. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(suppl 4):S5–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esmailnasab N, Moradi G, Delaveri A. Risk factors of non-communicable diseases and metabolic syndrome. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41:77–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chan S, Gomes A, Singh RS. Is menopause still evolving? Evidence from a longitudinal study of multiethnic populations and its relevance to women's health. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:74. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00932-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO Decade of Healthy Ageing: baseline report. 2020. https://https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338677

- 39.Campisi J, Kapahi P, Lithgow GJ, Melov S, Newman JC, Verdin E. From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature. 2019;571:183–192. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs World population prospects 2019: highlights. June 17, 2019. https://www.un.org/development/desa/publications/world-population-prospects-2019-highlights.html

- 41.Addison O, Steinbrenner G, Goldberg AP, Katzel LI. Aging, fitness, and marathon times in a 91 year-old man who competed in 627 marathons. Br J Med Med Res. 2015;8:1074–1079. doi: 10.9734/BJMMR/2015/17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodds RM, Syddall HE, Cooper R. Grip strength across the life course: normative data from twelve British studies. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heidari S, Ahumada C, Kurbanova Z. Towards the real-time inclusion of sex- and age-disaggregated data in pandemic responses. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.WHO Meeting report: redesigning child and adolescent health programmes. January, 2019. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/stage/child-health-redesign-report.pdf?sfvrsn=7f117c10_2

- 45.WHO A rapid assessment of the burden of indicators and reporting requirements for health monitoring. February, 2014. https://www.uhc2030.org/fileadmin/uploads/ihp/Documents/Tools/M_E_Framework/Rapid_Assessment_Indicators_Reporting_report_for_WG_revised_03Mar14.pdf

- 46.Hoxha K, Hung YW, Irwin BR, Grépin KA. Understanding the challenges associated with the use of data from routine health information systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Health Inf Manag. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1833358320928729. published online June 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.UNICEF Birth Registration for every child by 2030: are we on track? December, 2019. https://data.unicef.org/resources/birth-registration-for-every-child-by-2030

- 48.WHO Data availability: a visual summary. 2020. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data-availability-a-visual-summary