Abstract

Chronic venous ulcers (CVU) of the lower limbs (LL) are common and cause psychological changes and significant social impact, as they make the patient susceptible to pain, absence from work and social bonds. Some materials are suggested as dressings for the treatment of CVU, but they are expensive and are generally not available for use in public health services. To evaluate the efficacy of the treatment for lower limbs (LL) chronic venous ulcer (CVU) using bacterial cellulose (BC), gel and multi-perforated film associated. A randomized controlled clinical-intervention study was performed among participants with LL CVU, divided into two groups: experimental (EG), treated with BC wound dressing and control (CG), treated with a cellulose acetate mesh impregnated with essential fatty acids (Rayon®). The participants were followed for 180 days, evaluated according to the MEASURE methodology. Thirty-nine patients were treated, 20 from the EG and 19 from the CG. In both groups, the wound area decreased significantly (p < 0.001), the healing rate was similar to the CG. The mean number of dressing changes in the SG was 18.33 ± 11.78, while in the CG it was 55.24 ± 25.81, p < 0.001. The healing dressing of bacterial cellulose, gel and associated film, when stimulating the epithelization of the lesions, showed a significant reduction in the initial area, with a percentage of cure similar to the Rayon® coverage. In addition to requiring less direct manipulation of ulcers.

Introduction

The treatment of chronic venous ulcers (CVU) is a challenge to health professionals [1]. Its high incidence and morbidity lead to severe socioeconomical consequences and burdens health services [2–4]. The high cost associated with its treatment does not reflect the effective cure of the disease, this can be explained by the absence of a therapeutic standardization [5].

Health professionals are responsible for choosing and evaluating the adequate dressing for CVU’s treatment [1]. This choice is based on clinical characteristics of the ulcer, efficacy of the material, cost-benefit, practicality and availability of resources [1, 6, 7].

In this scenario, bioengineering gains space by associating the use of biomaterials, cell culture and growth factors in the production of instruments aimed at curing skin lesions [8]. Recently, Bacterial Cellulose (BC), a biomaterial produced from biotechnological synthesis, has gained prominence by achieving promising results when used as a dressing and biological graft [9, 10].

BC is produced from the action of the bacterium Zoogloea SP on the substrate of sugarcane molasses [9], manufactured by POLISA, Biopolymers for Health, a startup hosted by the Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE). It is an exopolysaccharide and composed of several monosaccharides, glucose (87.57%), xylose (8.58%), ribose (1.68), mannose (0.82%), arabinose (0.37), galactose (0.13%), raminose (0.01%), fructose (0.01) and glucuronic acid (0.83) [11, 12].

Presented in the form of gel, continuous or multi-perforated film and sponge, the BC has several physical and chemical properties: flexibility, adhesiveness, water retention capacity, low cytotoxicity, biocompatibility, prolonged use time, low cost, easy storage and handling [11, 13, 14]. Due to its characteristics, it has been used in the reconstruction of several tissues, such as arteries, tympanic membranes, urethra and as a matrix for cell culture [15–19].

A study carried out addressing the cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and antigenotoxicity of BC when testing it in vitro and in vivo in rats, demonstrated that they are neither cytotoxic nor genotoxic [14, 20], other studies also addressed the theme and proved BC biocompatibility and atoxicity [21–24].

BC is a flexible material, molds to the area that is applied, acts as a protective mechanical barrier, framework for cell migration and interaction, promotes neovascularization and, by facilitating cell colonization, creates an environment conducive to the healing process [20, 25–30].

Based on these characteristics, BC has been used in pre-clinical and clinical protocols for the treatment of clean or infected surgical wounds, as well as for active ulcers.

Thus, the BC, the gel and the associated multiperforated film, had their effectiveness evaluated as a dressing, low cost and easy to handle, in the treatment of patients with CVU.

Methods

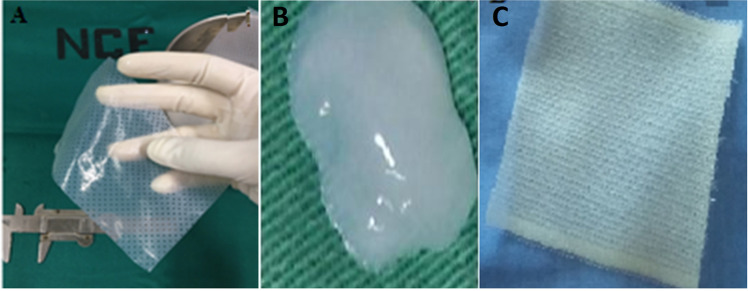

A randomized contromied clinical-intervention study was performed at the Angiology and Vascular Surgery Clinic of the Clinics Hospital/UFPE. Thirty-nine individuals with LL CVU were submitted to intervention, being randomly allocated into two groups: experimental (EG) with 20 patients treated with BC, gel and multi-perforated film associated (Fig. 1A, B) and control (CG) with 19 patients, treated with dressings made of a cellulose acetate mesh impregnated with essential fatty acids (RAYON®) (Fig. 1C). Some patients had more than one ulcer in the lower limbs, where all were treated according to their experimentation group.

Fig. 1.

A Hydrated bacterial cemiulose film showing its ductility, which amiows adaptation to the ulcer. B Aspects of the bacterial cemiulose gel. C Aspects of the Rayon® dressing

The study population included adults, regardless of the gender, with diagnosis of LL CVU. The exclusion criteria were: presence of arterial insufficiency, neoplastic and/or necrotic ulcers on LL. The individuals had a follow up and the ulcers were evaluated weekly for a period of 180 days.

All the patients were submitted to anamnesis, including their socioeconomical status and presence of other comorbidities.

BC, in gel and film forms, were provided by POLISA© Biopolímeros para Saúde, and produced exclusively with pure bacterial cellulose (98.73%), obtained from sugar cane molasses using biotechnological methods. Multi-perforated dressings with 0.1 mm thickness (25 perforations of 1.0 mm per cm²) and 20x10cm size were stored in surgical packaging and sterilized by gamma irradiation (25 kGy5). The gel obtained by homogenizing the microcrystalline bacterial cellulose on the proportion 0.8% cellulose in 99.2% of water [20], was presented in 5.0 mi syringes, stored in surgical packaging and sterilized by gamma irradiation (25 kGy5).

The dressing was performed as described by Cavalcanti et al. [26], (2017) adapting the procedure in specific cases when necessary, such as debriding and cleaning with 0.9% saline solution. On the EG, the ulcers were filled with 0.8% BC gel followed by coverage with the hydrated BC film. On the CG, the ulcers were covered with Rayon®. After dressing the ulcers in both groups, they were occluded with gauze and bandages (secondary dressing).

The CVU were evaluated according to the MEASURE methodology [31, 32], which provides wound-assessment on the following parameters: M (measure), E (exudate), A (appearance), S (suffering), U (undermining), R (re-evaluation), E (edge). This system includes an assessment of the wound in relation to morphometric aspects, quantity, and quality of examination, type of border, detachment (absent or present) and type of wound healing tissue (appearance).

The patients had a follow up and had their wound dressings evaluated weekly, as recommended. On the EG, when the BC film was adhered, only the gel was applied on top of the film in order to hydrate and occlude the dressing.

In the CG, the dressings were changed every 48–72 h, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with an average change of 10–15 a month. GE patients were instructed to remove the secondary dressing and wet their limb during shower, and after that, drying it and placing a new secondary dressing. For all patients, the use of elastic compression stockings was advised. Participants were disconnected from the study after the complete epithelialization of the CVU or by time, when they reached the 180th day of evaluation.

During follow-up visits, the wounds were measured and photographed (digital NIKON 3.200 camera on a 20 cm distance and a 90° angle). Ulcer measurements were obtained using the Image Tool software.

Sampling was performed by convenience, since all patients with active CVU were selected during the period of one year (February 2016 to February 2017), at the Angiology and Vascular Surgery Clinic of the Clinics Hospital / UFPE. All data was evaluated with the software IBM-SPSS, version 23. Mean, standard deviation (SD) and median were used for numerical variables, whereas absolute frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact tests were used to evaluate significant differences between groups in categorical variables. Regarding the numerical variables, Student-t or Mann-Whitney tests were used for independent samples, and the paired Student-t test or Wilcoxon test were used for paired data and comparisons between evaluations. To assess the normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed and for the equality of variances, the Levene F-test. Statistical tests were performed with a significance level of = 0.05.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee in Research of the Health Sciences Center of the Federal University of Pernambuco (CEP/CCS/UFPE). CAAE: 23402513.9.0000.5208; Report number: 1.501.560.

Results

This research included 39 patients with LL CVU and a total of 43 chronic venous ulcers assessed, being 27 (50.9%) in EG and 26 (49.1%) in CG. The female gender was predominant in both groups (EG, 70%; CG, 73.7%), in general, with a mean age of 62.41 ± 10.72 years. The main comorbidities were hypertension (64.1%), and diabetes mellitus (DM, 15.4%), however, without statistical significance (Table 1). For the treatment of comorbidities, most patients reported using antihypertensive pills (61.5%), oral hypoglycemic agents (15.4%) and medicines used for the treatment of Chronic Venous Insufficiency (CVI) 20.5%, being the distribution similar between the groups (p > 0.05), (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic data

| Groups | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | EG | CG | p value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 20 | 100.0 | 19 | 100.0 | 39 | 100.0 | – |

| Gender | p(1) = 0,798 | ||||||

| Male | 6 | 30.0 | 5 | 26.3 | 11 | 28.2 | |

| Female | 14 | 70.0 | 14 | 73.7 | 28 | 71.8 | |

| Age | p(2) = 0.598 | ||||||

| mean ± SD | 61.50 ± 8.36 | 63.37 ± 12.92 | 62.41 ± 10.72 | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| range (years) | p(3) = 0.074* | ||||||

| From 44 to 55 | 5 | 25.0 | 7 | 36.8 | 12 | 30.8 | |

| From 56 to 65 | 11 | 55.0 | 3 | 15.8 | 14 | 35.9 | |

| From 66 to 75 | 2 | 10.0 | 5 | 26.3 | 7 | 17.9 | |

| From 76 to 81 | 2 | 10.0 | 4 | 21.1 | 6 | 15.4 | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes | 2 | 10.0 | 4 | 21.1 | 6 | 15.4 | p(3) = 0.407 |

| Hypertension | 14 | 70.0 | 11 | 57.9 | 25 | 64.1 | p(1) = 0.431 |

| Benign breast lump | 1 | 5.0 | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | p(3) = 1.000 |

| Cardiopathy (CHF, Arrhythmia, CAD) | 4 | 20.0 | 3 | 15.8 | 7 | 17.9 | p(3) = 1.000 |

| Gastritis | 1 | 5.0 | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | p(3) = 1.000 |

| Asthma | 1 | 5.0 | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | p(3) = 1.000 |

| Erysipelas | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 4 | 10.3 | p(3) = 0.605 |

| Gastric/breast neoplasm | 2 | 10.0 | – | – | 2 | 5.1 | p(3) = 0.487 |

| CVA | – | – | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 2.6 | p(3) = 0.487 |

| Medications in use | |||||||

| Use of antihypertensive drugs | 14 | 70.0 | 10 | 52.6 | 24 | 61.5 | p(2) = 0.265 |

| Use of oral hypoglyceMIc agent | 2 | 10.0 | 4 | 21.1 | 6 | 15.4 | p(1) = 0.407 |

| Insulin use | 1 | 5.0 | – | – | 1 | 2.6 | p(1) = 1.000 |

| Symptomatic for CVI** | 3 | 15.0 | 5 | 26.3 | 8 | 20.5 | p(3) = 0,451 |

*n = number of patients with Chronic Venous Ulcer (CVU)

EG experimental group using bacterial cemiulose, gel and film associated, CG control group, SD standard deviation, CHF congestive heart failure, CAD coronary artery disease, CVA cerebrovascular accident, CVI chronic venous insufficiency

**Diosmin, Perivasc, Venalot, Varicoss

1Pearson Chi-squared test 2Student t test with unequal variances; 3Fisher’s exact test; 4Multiple answers. *Statisticamiy significant if p < 0.05

Among the topical drugs used by patients prior the start of this study, collagenase was the most used (EG = 75%; CG = 68.4%; p = 0.648), followed by the sunflower oil (EG, 70%; CG, 68.4%; p = 0.915). However, silver sulfadiazine, was used more by patients in the EG (50%) than in the CG (15.8%), with p = 0.023. During the research, these drugs were no longer used (Table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of active ulcers and relapses

| Variables | Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVU number | EG (na = 27) | CG (na = 26) | p value | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Ulcer activity time (months) | p (1) = 0.010* | ||||

| 1 to 12 | 11 | 40.7 | 14 | 53.8 | |

| 13 to 36 | 2 | 7.4 | 3 | 11.5 | |

| 37 to 60 | 4 | 14.8 | 5 | 19.2 | |

| 61 to 120 | 9 | 33.3 | – | – | |

| 121 to 360 | 1 | 3.7 | 4 | 15.4 | |

| Number of patients with CVU | EG (nb = 20) | CG (nb = 19) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | p (1) = 0.756 | ||||

| 0 | 7 | 35.0 | 6 | 31.6 | |

| 1 | 8 | 40.0 | 5 | 26.3 | |

| 2 | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 15.8 | |

| 3 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 10.5 | |

| 4 | – | – | 2 | 10.5 | |

| 5 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 5.3 | |

EG experimental group using the bacterial cemiulose, gel and film associated, CG control group

na = Absolute number of Chronic Venous Ulcer (CVU); nb = number of patients with CVU

*Statisticamiy significant if p < 0.05; 1Fisher’s exact test

Regarding the time of CVU activity, most patients had a time equal to or less than 12 months (EG, 40.7%; CG, 53.8%), with p = 0.01 between the groups. Regarding the occurrence of relapses, both groups showed 13 recurrent CVU patients.

After 180 days of evaluation, the size of the wounds decreased significantly in both groups, when comparing the groups, there were a reduction of 50.58% in EG’s ulcer area and 53.48% in CG (Table 3).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the ulcers’ areas in control (CG) and experimental (EG) groups

| Variable | Evaluation | Groups | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG (n = 27) | CG (n = 26) | |||

| Wound area in cm²: Mean ± SD, (Median) | Day 1 | 62.86 ± 89.46 (23.23) | 37.99 ± 48.30 (15.31) | p (1) = 0.810 |

| Day 180 | 31.06 ± 45.28 (11.26) | 17.67 ± 31.19 (1.44) | p (1) = 0.620 | |

| Difference between wound areas in cm² (day 180—day 1): Mean ± SD, (Median) | −31.80 ± 50.00 (16.35) | −20.32 ± 31.98 (12.96) | p (1) = 0.673 | |

| p value | p (2) < 0.001* | p (2) < 0.001* | ||

EG experimental group using the bacterial cemiulose, gel and film associated, CG control group

n = Absolute number of Chronic Venous Ulcer (CVU). *Statisticamiy significant difference (p < 0.05); 1Mann-Whitney test and 2Wilcoxon test for paired data

During 180 days of evaluation, complete wound healing occurred in 29.6% of the EG and 26.9% of the CG (Table 4). The changing frequency of primary dressings in EG was 18.33 ± 11.78 and 55.24 ± 25.81 in the CG, p < 0.001. Individuals from the CG had their dressings changed at least twice a week. In 70.4% of the EG, dressings with BC film remained adhered to ulcers with 4 to 30 days, p < 0.001.

Table 4.

Evaluation of the CVU regarding the need of dressing change in experimental and control groups

| Variable | Evaluation | Group | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EG (n = 27) | CG (n = 26) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Outcomes (%) | Complete wound healing | 8 | 29.6 | 7 | 26.9 | p (1) = 0.287 |

| Hospital Discharge for time** | 19 | 70.4 | 19 | 73.1 | ||

| Dressing changes in 180 days: Mean ± SD (Median) | 18.33 ± 11.78 (20.00) | 55.24 ± 25.81 (66.00) | p (2) < 0.001* | |||

| Period, in days, of the dressing’s adhesion (without change): | ||||||

| 1 to 3 | – | – | 26 | 100.0 | p (3) < 0.001* | |

| 4 to 30 | 19 | 70.4 | – | – | ||

| 31 to 60 | 05 | 18.5 | – | – | ||

| 61 to 90 | 02 | 7.4 | – | – | ||

| 91 to 120 | 01 | 3.7 | – | – | ||

n = Absolute number of Chronic Venous Ulcer (CVU)

EG experimental group using the bacterial cemiulose, gel and film associated, CG control group

*Statisticamiy significant difference (p < 0.05); 1Pearson Chi-squared test; 2Mann-Whitney test; 3Fisher’s exact test

**Patients reached the 180th day of evaluation

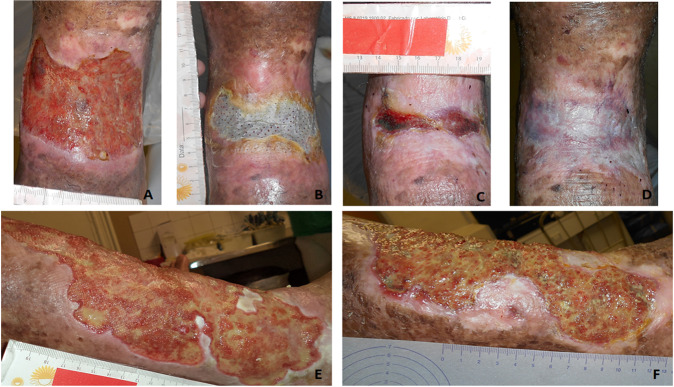

Figure 2 illustrates the healing evolution after treatment with BC dressings. Figure 2B demonstrates the adherence of the BC dressing to the ulcer. The BC, gel and film associated, CVU outline and protect the edges.

Fig. 2.

A Day 0 of treatment. Total skin loss, irregular edges, granulation tissue with reduced shattering, smami amount of serosanguineous exudate. B 68th day, BC film presents good adherence after 41 days without change. C 90th day, effective ulcer reduction, absence of maceration with smami areas of tissue granulation and seropurulent exudate, epithelialized edges. D 139th day, complete healing. Seven dressing changes were performed until complete healing of this patient. E Day 0. Active ulcer for 10 years, lateral view, irregular edges, macerated, bed with mixed tissue (granulation and shattering), large amounts of exudate. F 180th day, presenting reduction of total ulcer area, edge epithelization without maceration, bed stimi presents mixed tissue, moderate amount of exudate, 27 dressing changes were performed

A reduction in the amounts of exudate was observed in both EG and CG, p = 0.176. A part of the patients’ ulcers had complete healing of the injured tissue, ~29.6% in the EG and 26.9 in the CG (Healthy tissue, p = 0.744) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Evaluation of CVU qualitative data in the studied groups according to MEASURE

| Variable | Evaluation | Parameters | Groups | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | EG (n = 27) | CG (n = 26) | |||

| Exudate quantity | Day 1 | None | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.8) | p(1) = 0.922 |

| Smami | 14 (51.9) | 12 (46.2) | |||

| Moderate | 7 (25.9) | 8 (30.8) | |||

| Large | 4 (14.8) | 5 (19.2) | |||

| Day 180 | None | 9 (33.3) | 12 (46.2) | p(1) = 0.176 | |

| Smami | 9 (33.3) | 5 (19.2) | |||

| Moderate | 9 (33.3) | 6 (23.1) | |||

| Large | – (–) | 3 (11.5) | |||

| Exudate quality | Day 1 | Serous | 1 (3.7) | 9 (34.6) | p(1) = 0.005* |

| Serosanguineous | 23 (85.2) | 13 (50.0) | |||

| Seropurulent | 1 (3.7) | 3 (11.5) | |||

| None | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Day 180 | Serous | 2 (7.4) | 3 (11.5) | p(1) = 0.390 | |

| Serosanguineous | 16 (59.3) | 10 (38.5) | |||

| Sanguineous | – (–) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| None | 9 (33.3) | 12 (46.2) | |||

| Edge | Day 1 | Epithelialized | 1 (3.7) | – (–) | p(1) = 0.137 |

| Delimited | 6 (22.6) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| Irregular | 11 (40.7) | 14 (53.8) | |||

| Hardened | 1 (3.7) | – (–) | |||

| Macerate | 5 (18.5) | 8 (30.8) | |||

| Peeling | – (–) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| Shattered | 1 (3.7) | – (–) | |||

| Warmth/Erythema | 2 (7.4) | – (–) | |||

| Day 180 | Epithelialized | 17 (63.0) | 13 (50.0) | p(1) = 0.544 | |

| Delimited | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| Irregular | 6 (22.2) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Hardened | 1 (3.7) | – (–) | |||

| Macerated | 1 (3.7) | 4 (15,4) | |||

| Color | Day 1 | Red | 10 (37.0) | 8 (30.8) | p(2) = 0.725 |

| Yemiow | 4 (14.8) | 6 (23.1) | |||

| Mixed | 13 (48.1) | 12 (46.2) | |||

| Day 180 | Red | 12 (44.4) | 13 (50.0) | p(1) = 0.905 | |

| Yemiow | – (–) | 1 (3.8) | |||

| Mixed | 7 (25.9) | 5 (19.2) | |||

| Healed | 8 (29.6) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Appearance | Day 1 | Partial skin loss (Epidermis) | 8 (29.6) | 5 (19.2) | p(2) = 0.379 |

| Total skin loss (Subcutaneous) | 19 (70.4) | 21 (80.8) | |||

| Day 180 | Partial skin loss (Epidermis) | 4 (14.8) | 6 (23.1) | p(2) = 0.744 | |

| Total skin loss (Subcutaneous) | 15 (55.6) | 13 (50.0) | |||

| Healed | 8 (29.6) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| Wound healing tissue | Day 1 | Shattered | 18 (66.7) | 20 (76.9) | p(2) = 0.407 |

| Granulated | 25 (92.6) | 21 (80.8) | p(1) = 0.250 | ||

| Epithelium | — | 1 (3.8) | p(1) = 0.491 | ||

| Day 180 | Healthy | 9 (34.6) | 8 (30.8) | p(2) = 0.768 | |

| Granulated | 19 (70.4) | 18 (69.2) | p(2) = 0.928 | ||

| Epithelium | 13 (50) | 8 (30.8) | p(2) = 0.158 | ||

| Shattered | 10 (38.5) | 15 (57.7) | p(2) = 0.165 | ||

| Necrosis | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) | p(1) = 1.000 | ||

n = Absolute number of Chronic Venous Ulcer (CVU)

EG experimental group using the bacterial cemiulose, gel and film associated, CG Control group

*Statisticamiy significant difference (p < 0.05); 1 Fisher’s exact test and 2 Pearson’s Chi-square test

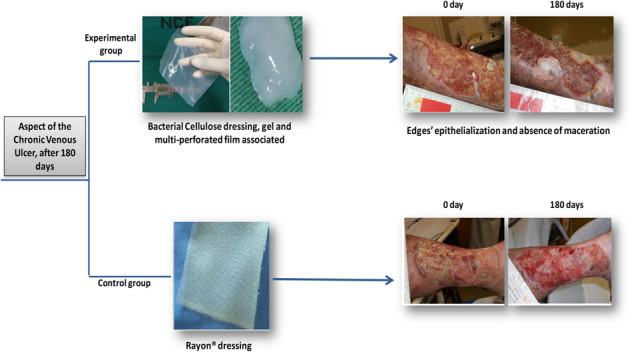

Figure 3 represents the clinical progression of CVU. In 180 days, it was possible to observe the edges’ epithelization and absence of maceration in the EG. Regarding the wound bed, there was a predominance of mixed tissue (devitalized tissue and granulated). In the CG, it was also observed epithelization and presence of mixed tissue (shattered and granulated) on the wound bed.

Fig. 3.

Aspect of the chronic venous ulcer. A, B represents the experimental group: A Day 0. Irregular and profound edges, maceration, wound bed with shattered (yemiow) and granulated (red) tissue, large amount of exudate. B After 180 days. Epithelial edges without maceration, presence of granulation and reduction of shattering, increased epithelization areas, low amounts of exudate and macerated islands of epithelial tissue (lateral and inferior edges). C, D represent the control group: C day 0, Irregular edges, maceration, large amount of shattered wound bed (yemiow), large amount of exudate. D Day 180. Epithelialized edge, low amount of maceration on the inferior part, large amount of granulation tissue (red), moderate amount of exudate

Discussion

In the current study, the mean age of the participants was 62 years old, the predominance was the female gender (above 70%) with a low-income social status. The predominance of CVU in females over 60 years of age are similar to data found in the literature [33, 34]. The high age of the patients and the active time of the ulcers reaffirm the chronic character of the disease, which can stay active for years or even decades [4]. The most observed comorbidities, without statistical significance, were hypertension and diabetes mellitus, conditions which are compatible to the participants’ age [35, 36].

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity observed in the studied groups, as it was present in more than 50% of patients. This data corroborates with other studies, demonstrating that this is a highly prevalent morbidity in patients with CVU, followed by heart diseases and DM [37–40]. The coexistence of these diseases is considered a risk factor for it negatively influences the healing process of CVU [39, 40]. These diseases cause micro and macrovascular changes, increase fluid overload and vascular resistance, reducing peripheral tissue perfusion and exacerbating the signs and symptoms of an already installed CVU [21, 22, 37, 39–41]. A previous study observed that among patients with CVU with activity times over 18 months, 63% had DM [38], and also that DM favors the installation of infections [37].

As a consequence of the comorbidities presented by the studied groups, treatments with antihypertensive and hypoglycemic drugs appear to be the most common, followed by the use of medications to relieve secondary symptoms caused by CVU. Pain, limb heaviness, edema and CVU itself are all clinical manifestations of CVU. By eliminating these symptoms, the edema reduces, leading to the improvement of local perfusion and bringing more comfort to the patient [42]. In general, a successful CVU therapy is associated with the treatment of metabolic disorders, since the patient’s clinical condition directly reflects on the response of the healing process [43].

Collagenase dressings, sunflower oil, Unna boots and silver sulfadiazine are widely described in the literature [26, 37, 40, 44–49].

The use of these coverings can be explained by the easy access to these products, sometimes because they are common in Family Health Units (FHU) and sometimes because they are the most economically viable coverings for the population. However, the prolonged use of silver sulfathiazine can lead to therapeutic failure, since CVU tend to be contaminated, and the continued use of topical antibiotics leads to bacterial resistance, and together with the chronicity of the lesion, facilitates the formation of biofilms [39].

When evaluating the mean of the areas of the CVU, it is observed that this is approximately twice as high in the EG when compared to the CG. In addition, the EG has a longer activity time of the UVC and more than 50% of them relapsed, factors that are associated negatively influencing the healing process, since the healing time is directly related to the extent and activity of the ulcer [36–38, 50]. However, after 180 days of treatment, there was not only a significant reduction in the area, but also a percentage of cure statistically similar to that of the CG.

The healing rate obtained in this study was similar to others [26, 38–40] and higher than the percentage found in pioneering research, with the application of BC multiperforated film in CVU. The study in question obtained a cure rate of 14.28% and in the non-healed lesions it did not show a reduction rate, but there was superficialization of the wounds [26]. The success achieved by the present study may be associated with a longer treatment time and the association of BC gel with the multiperforated film. In preclinical studies, BC gel has demonstrated the ability of vascular neoformation, which might promote an increase of granulation tissues [21, 22, 51].

The BC gel promoted better adhesion and fixation time of EG dressings, enabling a greater acceptance by the patients in comparison to the CG. There were no cases of hypersensitivity reactions and dermatitis induced by the BC gel, similar to other studies [20, 29, 30]. The reduction on the number of dressing changes in the EG promoted by its longer permanence on the CVU was significantly higher in comparison to the GC, p = 0.001. The BC, gel and film associated are easy to handle and can remain on the CVU for a long time or even remain on the lesion until complete epithelialization [29, 30, 51].

By being adhered to the CVU for a longer period, the multi-perforated BC film acts as a second skin, reducing the need of direct manipulation with frequent dressing changes, and allows the direct hygiene of the ulcerated limb during shower. Therefore, the pain is reduced and there is a low risk of infection, also enabling the patient to have more freedom, simplifying self-care, and reducing the high operational cost [41].

Clinically, there was a reduction in exsudativas CVUs with loss of subcutaneous tissue, this decrease is directly associated with superficialization and epithelization of the wounds, a result similar to studies with the theme [26, 51].

The association between the multi-perforated film and the BC gel, stimulates and leads to cell growth in the wound bed, because by acting as a framework [25] it favors the proliferation of granulation tissue and superficialization of the lesion [10, 14]. Important property for healing, since it is depends not only on the epithelialization of the edges, but also on the granulation and superficialization of the bed [26].

Based on the data evidenced by the study, the BC dressing is a promising alternative for the treatment of CVU.

Therefore, the concomitant application of Bacterial Cellulose, gel and multi-perforated film for the treatment of CVU has clinical quality, allowing its application in different types of skin lesions. Thus, its use in human health can be expanded, benefiting patients and reducing the operational costs associated with the treatment of ulcers.

Conclusion

The healing dressing of Bacterial Cellulose, gel and associated film, showed a statistically significant reduction in the initial area, with a cure percentage similar to rayon coverage, which is already widely known in the market. It also required less frequency of changes, minimizing the direct manipulation of ulcers and the risk of contamination. It is noteworthy that the ease of handling and self-adhesion of the CB dressing to the bed of the CVU provided greater autonomy and well-being to patients. The data confirm that the BC healing dressing is an effective alternative for the treatment of CVU.

Acknowledgements

The research was performed in collaborstion with the Department of Nuclear Energy (DEN), Geosciences and Technology Center (CTG), Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife/PE, Brazil and Federal Rural University of Pernambuco (UFRPE, Recife/PE, Brazil).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Santos AC, Dutra RAA, Salomé GM, Ferreira LM. Construction and internal reliability of an algorithm for choice cleaning and topical therapy on wounds. J Nurs UFPE Line. 2018;12:1250–62. doi: 10.5205/1981-8963-v12i5a230675p1250-1262-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dantas D, Torres GV, Dantas RAN. Assistência aos portadores de feridas: caracterização dos Protocolos existentes no Brasil. Cienc Cuid Saude. 2011;10:366–372. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saraiva DMRF, Bandarra AJF, Agostinho ES, Pereira NMM, Lopes TS. Quality of life of service users with chronic venous ulcers. Rev de Enferm Refência. 2013;serIII:109–18. doi: 10.12707/RIII1241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samuel N, Carradice D, Wamiace T, Smith GE, Chetter IC. Endovenous thermal ablation for healing venous ulcers and preventing recurrence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;10 (CD009494). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Borges EL, Caliri MHL, Haas VJ, Ferraz AF, Spira JO, Tyrone AC. Use of the Diffusion of Innovation Model in venous ulcers by specialized professionals. Rev Bras Enferm. 2017;70:610–7. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zenilman J, Vamie MF, Malas MB, Maruthur N, Qazi U, Suh Y et al. Chronic Venous Ulcers: A Comparative Effectiveness Review of Treatment Modalities. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 127. (Prepared by Johns Hopkins Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10061-I). [Rockvimie, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality]. AHRQ Publication. 2013; 13(14): EHC121-EF.

- 7.Rocha DM, Bezerra SMG, Oliveira AC, Silva JS, Ribeiro IAP, Nogueira LT. Custo da terapia tópica em pacientes com lesão por pressão. Rev enferm UFPE. 2018;12:2555–63. doi: 10.5205/1981-8963-v12i10a237569p2555-2563-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobral CS, Gragnani A, Xudong C, Morgan JR, Ferreira LM. Human keratinocytes cultured on collagen matrix used as an experimental burn model. J Burns Wounds. 2007;7:53–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albuquerque PCVC, Aguiar JLA, Santos SM, Pontes FilhoN, Mello RJV, Costa MLCR, et al. Comparative macroscopic study of osteochondral defects produced in femors of rabbits reoaired with biopolymer gel cane sugar. Acta Cir Bras. 2011;26:383–6. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502011000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fragoso AS, Silva MB, Melo CP, Aguiar JLA, Rodrigues CG, Medeiros PL, et al. Dielectric study of the adhesion of mesenchymal stem cemis from human umbilical cord on a sugarcane biopolymer. J Mater Sci: Mater Med. 2014;25:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s10856-013-5056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterson-Beedle M, Kennedy JF, Melo FAD, Lloyd LL, Medeiros VA. Cellulosic exopolysaccharide produced from sugarcane molasses by a zoogloea sp. Carbohydr Polym. 2000;42:375–383. doi: 10.1016/S0144-8617(99)00179-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavalcante AHM, Carvalho Júnior LB, Carneiro-da-Cunha MG. Cellulosic exopolysaccharide produced by Zoogloea sp. as a film support for trypsin immobilisation. Biochemical Eng J. 2006;29:258–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2006.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucena MT, Melo Júnior MR, Lira MMM, Castro CM, Cavalcanti LA, Menezes MA, et al. Biocompatibility and cutaneous reactivity of cellulosic polysaccharide film in induced skin wounds in rats. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2015;26:5410. doi: 10.1007/s10856-015-5410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira GM, Vieira JMS, Albuquerque ELMS, Albuquerque AV, Aguiar JLA, Pinto FCM. Curativo de celulose bacteriana para o tratamento de lesões por pressão em pacientes hospitalizados. Ver. Enfer. Atual in Derme – Especial. 2019;87.

- 15.Coelho COC, Carrazoni PG, Monteiro VLC, Melo FAD, Mota A, Filho FT. Biopolímero produzido a partir da cana-de-áçucar para cicatrização cutânea. Acta Cir Brasileira. 2002;17(Suppl 1):11–13. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502002000700003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marques SRB, Lins EM, Aguiar JLA, Albuquerque MCS, Rossiter RO, Montenegro LT, et al. A new vascular substitute: femoral artery angioplasty in dogs using sugarcane biopolymer membrane patch – hemodynamic and histopathologic evaluation. J Vasc Bras. 2007;6:309–315. doi: 10.1590/S1677-54492007000400003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silveira ABFN, Aguiar JLA, Campos Júnior O, Diniz GT, Lima SV. Membrana de Biopolímero da Cana-de-açúcar: Uma Realidade como Opção para Correção da Incontinência Urinária. Millenium. 2014;46:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer DLB, Araújo JG, Leal MC, Caldas NSS, Ataíde RF, Mello RJV. Sugarcane biopolymer membrane: experimental evaluation in the middle ear. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;77:44–50. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942011000100008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lima SVC, Machado MR, Pinto FCM, Lira MMM, Albuquerque AVA, Lustosa ES, et al. A new material to prevent urethral damage after implantation of artificial devices: an experimental study. Int Braz J Urol. 2017;43:335–344. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2016.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinto FCM, De-Oliveira ACAX, De-Carvalho RR, Gomes-Carneiro MR, Coelho DR, Lima SVC, et al. Acute toxicity, cytotoxicity, genotoxicity and antigenotoxic effects of a cemiulosic exopolysaccharide obtained from sugarcane molasses. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;137:556–560. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordeiro-Barbosa FA, Aguiar JLA, Lira MMM, Pontes Filho NT, Bernardino-Araújo S. Use of a gel biopolymer for the treatment of eviscerated eyes: experimental model in rabbits. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012;75:267–272. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492012000400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medeiros Júnior MD, Carvalho EJA, Catunda IS, Bernardino-Araújo S, Aguiar JLA. Hydrogel of polysaccharide of sugarcane molasses as carrier of bone morphogenetic protein in the reconstruction of critical bone defects in rats. Acta Cir Bras. 2013;28:233–238. doi: 10.1590/S0102-86502013000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albuquerque PCVC, Aguiar JLA, Pontes Filho NT, Mello RJV, Olbertz CMCA, Albuquerque PEMC, Paz ST, Santos AHS, MaiaCS. A comparative study of the areas of osteochondral defects produced in femoral condyles of rabbits treated with sugar cane biopolymer gel. Acta Cirúrgica Brasileira. 2015;30 770-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Silva JGM da; Pinto FCM, Oliveira GM de, Silva AA da; Campos Júnior O, Silva RO, et al., Oliveira ACAX, Aguiar JLA, Teixeira AAC. Estudo não clínico de segurança de um hidrogel de celulose bacteriana de cana-de-açúcar. Research, Society and Development. 2020; [S. l.], v. 9, n. 9, p. e960997932.

- 25.Ferreira LKM, Muniz-Filho E, Oliveira EB, Paz ST, Santos FAB, Alves LC et al. Avaliação in vitro do processo de adesão de macrófagos j774 com arcabouço 3d de biopolimero de cana-de-açúcar. Anais do Encontro Anual da Biofísica. 2017;p.33-35.

- 26.Cavalcanti LM, Pinto FCM, Oliveira GM, Lima SVC, Aguiar JLA, Lins EM. Efficacy of bacterial cemiulose membrane for the treatment of lower limbs chronic varicose ulcers: a randoMIzed and contromied trial. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2017;44:072–080. doi: 10.1590/0100-69912017001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martins AGS, Lima SVC, Araujo LAP, Vilar FO, Cavalcante NTP. A wet dressing for hypospadias surgery. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:408–413. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.03.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilar FO, Pinto FCM, Albuquerque AV, Martins AGS, Araújo LAP, Aguiar JLA, et al. A wet dressing for male genital surgery: A phase II clinical trial. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42:1220–1227. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2016.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lima SVC, Rangel AEO, Lira MMM, Pinto FCM. Campos Junior O, Sampaio FJB, et al. The biocompatibility of a cemiulose exopolysaccharide implant in the rabbit bladder when compared with dextranomer microspheres plus hyaluronic acid. Urology. 2015;85:1520.el–1520.e6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Pita PCC, Pinto FCM, Lira MMM, Melo FAD, Ferreira LM, Aguiar JLA. Biocompatibility of the bacterial cemiulose hydrogel in subcutaneous tissue of rabbits. Acta Cir Bras. 2015;30:296–300. doi: 10.1590/S0102-865020150040000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keast DH, Bowering CK, Evans AW, Mackean GL, Burrows C, D’Souuza L. MEASURE: A proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(Suppl 3):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.0123S1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cruz RAO, Acioly CMC, Nóbrega VKM, Oliveira OS. Feridas complexas e o biofilme: atualização de saberes e práticas para enfermagem. Rev Rede de Cuid em Saúde. 2016;10:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silva MH, Pinto de Jesus MC, Merighi MAB, Oliveira DM, Santos SMR, Vicente EJD. Manejo clínico de úlceras venosas na atenção primária à saúde. Acta Paul Enferm. 2012;25:329–33. doi: 10.1590/S0103-21002012000300002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gethin G, Cowman S, Kolbach DN. Debridement for venous leg ulcers (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 9(CD008599).52 pag. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Oliveira BGRB, Nogueira GA,Carvalho MR, et al. dos pacientes com úlcera venosa acompanhados no Ambulatório de Reparo de Feridas. Rev. Eletr. Enf. 2012; 14:156-63.

- 36.Afonso A, Barroso P, Marques G, Gonçalves A, Gonzalez A, Duarte N, et al. Úlcera crónica do membro inferior — experiência com cinquenta doentes. Angiol Cir Vasc. 2013;9:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mata VE, Porto F, Firmino F. Tempo e custo do procedimento: curativo em úlcera vasculogênica. Rev Pesq Cuid Fundam. 2011;3:1628–37. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro APL, Oliveira BGRB, Soares MF, et al. SR. A efetividade dos géis de papaína a 2% e 4% na cicatrização de úlceras venosas. Rev esc enferm Usp. 2015;49:394–400. doi: 10.1590/S0080-623420150000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scotton MF, Miot HA, Abbade LPF. Factors that influence healing of chronic venous leg ulcers:a retrospective cohort. Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:414–22. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maia AL, Lins EM, Aguiar JLA, Pinto FCM, Rocha FA, Batista MI, et al. Curativo com filme e gel de biopolímero de celulose bacteriana no tratamento de feridas isquêmicas após revascularização de membros inferiores. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2019;46:e20192260. doi: 10.1590/0100-6991e-20192260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chicone G, Carvalho VF. Aspectos etiológicos, epideMIológicos e fisiopatológicos das feridas causadas por hipertensão venosa. Rev Enferm Atual Derme. 2012;63:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belczak SQ, Sincos IR, Campos W, Beserra J, Nering G, Aun R. Veno-active drugs for chronic venous disease: A randoMIzed, double-blind, placebo-contromied paramiel-design. Trial Phlebol. 2014;29:454–460. doi: 10.1177/0268355513489550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gershater MA, Apelqvist J. Elderly individuals with diabetes and foot ulcer have a probability for healing despite extensive comorbidity and dependency. Expert Review of PharmacoeconoMIcs & Outcomes Research, 2020. 10.1080/14737167.2020.1773804 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Abbade LPF, Ferreira Júnior RS, Santos LD, Barraviera B. Chronic venous ulcers: a review on treatment with fibrin sealant and prognostic advances using proteoMIc strategies. J Venom Anim Toxins incl Trop Dis. 2020;26:e2019010. doi: 10.1590/1678-9199-jvatitd-2019-0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farina Junior JA, Coltro PS, Oliveira TS, Correa FB, Dias-de-Castro JC. Curativos de prata iônica como substitutos da sulfadiazina para feridas de queimaduras profundas: relato de caso. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2017;16:53-57.

- 46.Sharp NE, Aguayo P, Marx DJ, Polak EE, Rash DE, Peter SD, et al. Nursing preference of topical silver sulfadiazine versus comiagenase ointment for treatment of partial thickness burns in children: survey fomiow-up of a prospective randoMIzed trial. J Trauma Nurs. 2014;21:253–7. doi: 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sant’Ana SMSC, Bachion MM, Santos QR, Nunes CAB, Malaquias SG, Oliveira BGRB.Úlceras venosas: caracterização clínica e tratamento em usuários atendidos em rede ambulatorial. Rev. Bras. de Enferm. 2012;65:637-644. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Colenci R, MIot HA, Marques MEA, SchMItt JV, Basmaji P, Jacinto JS, et al. Cemiulose biomembrane versus comiagenasedressing for the treatment of chronic venous ulcers: a randomized, contromied clinical trial. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:387–95. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nornan G, Westby MJ, Rithalia AD, Stubbs N, Soares MO, Dumvimie JC. Dressings and topical agents for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018, Issue 6. Art. N°.: CD012583.DOI10.1002/14651858.CD012583.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Hämmerle G, Strohal R. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of octenidine wound gel in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers in comparison to modern wound dressings. Int Wound J. 2014;13:182–188. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliveira MH, Pinto FCM, Ferraz-Carvalho RS, Albuquerque AV, Aguiar JL. BIO-NAIL: a bacterial cellulose dressing as a new alternative to preserve the nail bed after avulsion. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2020;31:121. doi: 10.1007/s10856-020-06456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]