Abstract

Introduction

Non-pharmacological approaches are recommended as first-line treatment for patients with fibromyalgia. This randomised controlled trial investigated the effects of a multicomponent rehabilitation programme for patients with recently diagnosed fibromyalgia in primary and secondary healthcare.

Methods

Patients with widespread pain ≥3 months were referred to rheumatologists for diagnostic clarification and assessment of study eligibility. Inclusion criteria were age 20–50 years, engaged in work or studies at present or during the past 2 years, and fibromyalgia diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology 2010 criteria. All eligible patients participated in a short patient education programme before inclusion and randomisation. The multicomponent programme, a 10-session mindfulness-based and acceptance-based group programme followed by 12 weeks of physical activity counselling was evaluated in comparison with treatment as usual, that is, no treatment or any other treatment of their choice. The primary outcome was the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC). Secondary outcomes were self-reported pain, fatigue, sleep quality, psychological distress, physical activity, health-related quality of life and work ability at 12-month follow-up.

Results

In total, 170 patients were randomised, 1:1, intervention:control. Overall, the multicomponent rehabilitation programme was not more effective than treatment as usual; 13% in the intervention group and 8% in the control group reported clinically relevant improvement in PGIC (p=0.28). No statistically significant between-group differences were found in any disease-related secondary outcomes. There were significant between-group differences in patient’s tendency to be mindful (p=0.016) and perceived benefits of exercise (p=0.033) in favour of the intervention group.

Conclusions

A multicomponent rehabilitation programme combining patient education with a mindfulness-based and acceptance-based group programme followed by physical activity counselling was not more effective than patient education and treatment as usual for patients with recently diagnosed fibromyalgia at 12-month follow-up.

Trial registration number

BMC Registry (ISRCTN96836577).

Keywords: rheumatology, rehabilitation medicine, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This pragmatic randomised controlled trial was conducted according to a predefined published protocol.

The main treatment effects were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis at 12-month follow-up, with all randomised patients retaining their original allocated groups.

Although we intended to capture patients with fibromyalgia at an early stage of their disease, the included patients reported median symptoms duration of 8 years.

There was a high drop-out rate from the physical activity intervention.

We did not monitor the content of ‘treatment as usual’ in the control group other than physical activity.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is characterised by widespread pain and symptoms such as fatigue, unrefreshed sleep, mood disturbances and cognitive impairment that have persisted more than 3 months without any alternative explanation.1 Patients report unpredictable symptoms that vary in terms of expression and intensity, and reduced quality of life.2–5 The estimated prevalence of FM in the general population worldwide is between 2% and 7%, with women being predominantly affected.6 Many patients experience lack of understanding from their primary care physicians, insufficient healthcare and deficient treatment.7 8

For optimal management of FM, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends prompt diagnosis and patient education as first-line treatment. The effects of pharmacological treatments are inadequate.4 The management should aim at improving patients’ health-related quality of life and initially focus on non-pharmacological modalities.4 9 Individualised physical exercise is recommended for all patients with FM. Cognitive–behavioural therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, meditative movement (ie, qigong, yoga, tai chi), and hydrotherapy have shown promising effects for some patients, although the evidence is still insufficient.4 Further, multicomponent programmes combining physical exercise with either of these modalities have shown beneficial synergetic effects on FM symptoms in terms of reduced pain and FM impact, and increased physical fitness at the end of treatment.4 10

Three recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions had short-term small-to-moderate effects on pain, depression, anxiety, sleep quality and health-related quality of life in patients with FM.11–13 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses on physical exercise in patients with FM have shown beneficial effects on symptoms, such as pain, sleep and physical function.14–18

A Norwegian mindfulness-based and acceptance-based intervention, the Vitality Training Programme (VTP), aimed at strengthening participants’ health-promoting resources and ability to make choices in accordance with own values, has been evaluated in two randomised controlled trials in persons with chronic musculoskeletal pain and inflammatory arthritis (IA). The VTP improved pain, fatigue, psychological distress, pain coping, and self-efficacy for pain and other symptoms.19 20 The effects persisted at 12-month follow-up in both studies. However, a preceding longitudinal pre/post-test study on the VTP in patients with IA and FM showed substantial improvements in patients with IA, but no changes in patients with FM.21 In a nested qualitative study, the patients with FM described how they had struggled for years to be believed and taken seriously.22 The authors suggested that the lack of effects in patients with FM might have been related to long symptoms duration without recognition and treatment, which may have led to the development of maladaptive patterns of coping strategies that are difficult to change. They proposed that future studies should investigate the effects of the VTP in patients with FM at an early stage of their disease.

The aim of the present randomised controlled trial was to study the effects of a community-based multicomponent rehabilitation programme comprising the VTP followed by 12 weeks of physical activity (PA) counselling in patients with recently diagnosed FM. More specifically, we examined whether the multicomponent rehabilitation programme improved patients’ self-perceived health, pain, fatigue, sleep quality, psychological distress, PA and work ability, compared with treatment as usual, that is, no treatment or any other treatment of their choice.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a two-armed parallel randomised controlled trial in rural and urban communities in the southeastern part of Norway. Patients were allocated to the VTP and PA (intervention group) or treatment as usual (control group). More details can be found in the published protocol (ISRCTN 96836577).23 We followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials in this report.24 25

Participants

General practitioners and physiotherapists referred patients who had widespread pain that had lasted for at least 3 months to rheumatologists in specialist healthcare for diagnostic clarification and assessment of study eligibility. Inclusion criteria were age 20–50 years and FM diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology 2010 criteria.1 26 Patients were excluded if they had an inflammatory rheumatic disease, had a severe psychiatric disorder, another disease that did not allow PA, or if they were unable to understand or write Norwegian. We also excluded patients who had been out of work for more than 2 years.

Procedure and interventions

All eligible patients received a 3-hour patient education programme and oral information about the study. Patients who agreed to participate completed written informed consent before inclusion. The VTP was organised in the local communities with 7–12 patients in each group. It comprised 10 weekly 4-hour sessions plus a booster session after approximately 6 months. Every session addressed a specific topic: If my body could talk/Who am I?/My resources and potentials/Values—what is important to me?/What do I need?/Strengths and limitations/Bad conscience/Anger/Joy/Resources, potentials and choices/Closure and the way ahead. These were explored by various creative methods, such as guided imagery, music, drawing, poetry, metaphors and reflections. The patients wrote logs after all exercises and shared their experiences with other group participants.

Moreover, patients were invited to attend mindfulness meditation, that is, body scan, sitting and walking meditation, and gentle yoga exercises.27 They were encouraged to listen to guided mindfulness meditation audio files and practise awareness in their daily activities between sessions.28 The group facilitators were experienced nurses and physiotherapists, who were certified by a 1-year postgraduate training programme (30 credits). The facilitators followed a standardised manual with a thorough programme description and monitored the attendance throughout the programme. Based on previous studies, the patients needed to attend at least five sessions to expect effect.20 23 Online supplemental file 1 describes an example of the structure and content of one of the sessions.

bmjopen-2020-046943supp001.pdf (56.4KB, pdf)

The PA counselling was conducted at a Healthy Life Centre (HLC), which is a low threshold healthcare service provided in Norwegian communities designed as easily accessible generic services aimed at lifestyle changes. HLCs typically offer a 12-week programme during daytime, comprising individual counselling based on motivational interviewing, individual and group PAs.29 A physiotherapist provided the individual PA counselling. This intervention aimed at helping patients to set tailored goals, identifying and overcoming barriers to PA, and guiding them into exercises that they could continue after the 12-week period to increase the level of PA gradually.

Control group patients did not receive any organised intervention other than diagnostic clarification and the patient education session but were free to attend any treatment and activity at their own initiative. The control group was offered the VTP and the HLC intervention after completion of the data collection at 12-month follow-up.

Outcomes

The outcome measures were selected according to a core set of domains for FM defined by the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials.30 31 Self-reported questionnaires comprising baseline demographics and all outcome measures were collected electronically before randomisation (baseline), after the VTP (3 months) and at 12 months from baseline.

Primary outcome: Patient Global Impression of Change

Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) is a validated ordinal 7-point self-reported scale that measures how patients feel that their health has changed from they entered the trial to post-intervention data collections. The scale ranges from 1 (I feel very much worse) through 4 (no change) to 7 (I feel very much better).32 Scores 6 and 7 are considered a clinically relevant improvement. PGIC has previously been used in FM trials and is recommended as a core measure to improve the applicability of information from clinical trials to clinical practice.33–35 Higher scores in PGIC have been associated with more significant improvements in key FM symptoms and correlate well with FM outcomes.33 The scores can be dichotomised into ‘Less than much better’ (scores 1–5) and ‘Much better’ (scores 6 and 7).34

Secondary outcomes

Pain, fatigue and sleep quality were assessed by Numerical Rating Scale scored from 0 to 10 (10 is intolerable pain/fatigue/very bad sleep).31 Psychological distress was assessed by the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ-12) that comprises six positively phrased items indicating psychological health and six negatively phrased items indicating psychological distress.36 The respondents scored their condition during the last 2 weeks compared with what they perceived as their ‘normal’ condition on a 4-point Likert scale, reported from 0 (less than usual) to 3 (much more than usual). The scale was reversed for negatively phrased items. Data were analysed and reported as mean sum score; higher scores represented higher psychological distress.37 38 A general tendency to be mindful in daily life situations was assessed by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) that comprises 39 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never true) to 5 (always true).39 Higher scores reflected higher levels of mindfulness. The scale was reversed for negatively phrased items. Data were analysed and reported as a mean sum score, comprising all five facets. PA was assessed by three questions from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study.40 The questions measure frequency, intensity and duration of leisure-time physical exercises such as walking, skiing, swimming or other training/sport activities that improve physical fitness. A summary index of weekly PA was calculated from the frequency, intensity and duration scales with scores from 0 to 15. Higher scores indicate increased PA. Motivation and barriers for PA were assessed by the Exercise Beliefs and Exercise Habits Questionnaire comprising 20 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’.41 The items were divided into four subscales calculated and reported separately as beliefs about one’s ability to exercise, barriers to exercise, benefits of exercise and impact of exercise on muscular pain. Work ability was assessed by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment General Health V.2.1 (WPAI:GH) comprising six questions to determine employment status; hours missed from work because of health problems or other reasons; and hours worked.42 Higher scores indicate more significant impairment and less productivity. For this study, we calculated the outcomes ‘overall work impairment’ and ‘daily activity impairment’. Health-related quality of life was assessed with EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) comprising five dimensions; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression scored on five levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems. The EQ-5D-5L scores range between 0 and 1, 0 indicates death and 1 indicates perfect health.43 Second, the participants rate their overall health on a 0–100 hash-marked, vertical Visual Analogue Scale, 0 is as bad as it could be and 100 as good as it could be.44

Harms

Patients were asked to report adverse events at 12 months and major symptoms that were associated with these events.

Randomisation and blinding

A statistician generated an electronic randomisation list for each geographical area to ensure approximately equal sample sizes. A research assistant not involved in the study generated the allocation sequence and assigned patients to study groups. Further, the facilitators of the VTP groups organised and administered the enrolment. Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the patients and the VTP facilitators to group allocation. The project leader and the research coordinator who were responsible for the data collection and data analysis were blinded to the allocation.

Sample size

Sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome assuming that 10% in the control group would report clinically relevant improvement at 12-month follow-up, and that at least 20% absolute difference in improvement rate between the groups would be considered a minimum clinically relevant difference. With allowance for 10% losses to follow-up, 70 patients in each group were needed to have at least 80% power of detecting differences with 5% alpha level.

Statistical analyses

Mean values and SD were calculated for continuous variables or as median with minimum and maximum values if skewed. Frequency numbers and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Baseline differences in patients’ characteristics between intervention and control group were assessed by independent group t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. For categorical variables, we used Pearson’s Χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when the expected cell count fell below five. The treatment effects were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis with all randomised patients retaining their original allocated groups at 12 months. The distribution of the primary outcome (PGIC) was analysed as an ordinal variable by Mann-Whitney U test. When dichotomised, the difference between groups was tested with Χ2 statistics and Fisher’s exact tests. Treatment effects in secondary outcomes were estimated by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) at 3-month and 12-month follow-up adjusted for the baseline values. The level of statistical significance was set to ≤0.05. We used STATA V.14.045 to analyse the data. Missing values in single items of FFMQ and GHQ-12 were imputed by calculating the mean value of the registered values multiplied with the number of questions.

Patient and public involvement

Representatives from the Patient Advisory Board at the Diakonhjemmet Hospital were involved in the development of the study, such as study design, research questions and recruitment of patients. The electronic questionnaires were tested and amended by user representatives. More information is described elsewhere.23

Results

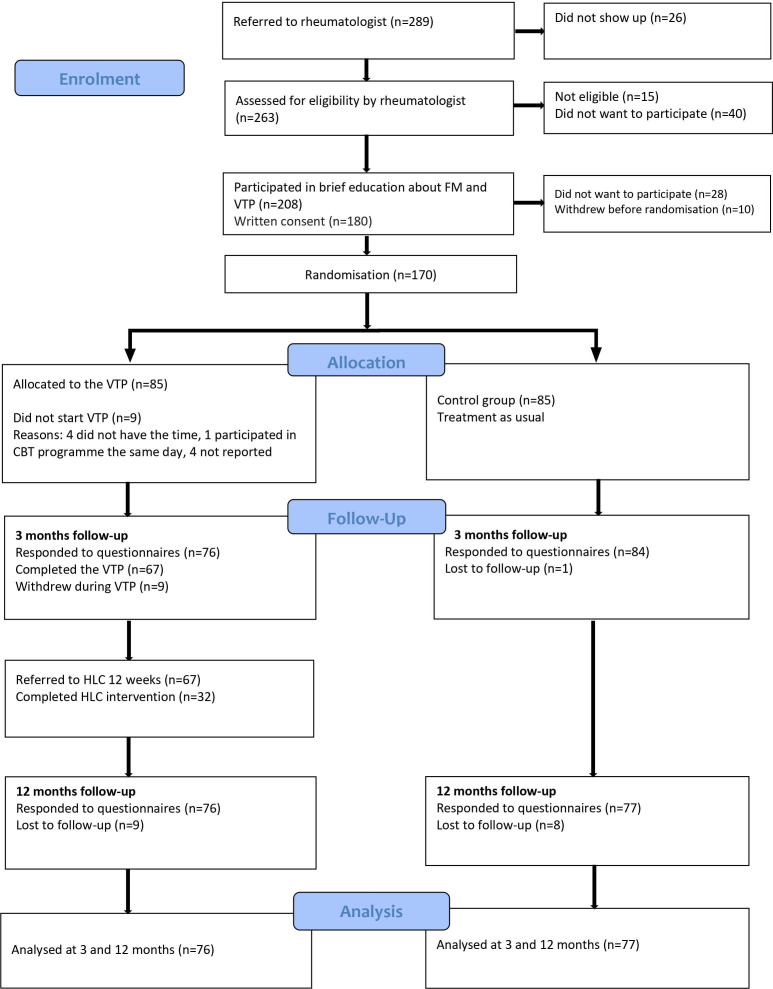

Of the 289 patients who were referred to the rheumatologists, 208 (72%) were eligible for inclusion. A total of 170 consented to participate and were randomised; 85 to the intervention group and 85 to the control group. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of patients through the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; FM, fibromyalgia.

The intervention group had a significant higher median age (p=0.02) and symptoms duration in years (p=0.05) compared with the control group. All other baseline characteristics were equally distributed between the groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics at baseline

| Variables | All patients (n=170) |

Intervention group (n=85) |

Control group (n=85) |

P value |

| Age, years, median (min, max) | 42 (24, 52) | 44 (26, 52) | 41 (24, 51) | 0.02* |

| Gender, women | 159 (94%) | 78 (92%) | 81 (95%) | 0.54† |

| Education | 0.60‡ | |||

| Primary/middle school (1–10 years) | 20 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 12 (14%) | |

| Upper secondary school/vocational 10–12 years | 68 (40%) | 36 (42%) | 32 (38%) | |

| Bachelor/university >12 years | 81 (48%) | 40 (47%) | 41 (48%) | |

| Work status | ||||

| Currently in paid work | 119 (70%) | 59 (69%) | 60 (71%) | 0.94‡ |

| Not in paid work | 48 (28%) | 24 (28%) | 24 (28%) | 0.94‡ |

| In paid work but on sick leave (100%) | 8 (17%) | 3 (13%) | 5 (21%) | |

| Work assessment allowance | 35 (73%) | 20 (83%) | 15 (62%) | |

| Unemployed | 4 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (13%) | |

| Student | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Married/living with partner | 120 (71%) | 54 (64%) | 66 (78%) | 0.06‡ |

| Symptoms duration, years, median, (min, max) | 8 (1, 32) | 10 (1, 32) | 7 (1, 30) | 0.05* |

| Comorbidities, median (min, max) | 2 (1, 6) | 2 (1, 6) | 2 (1, 6) | 0.24* |

| Smokers | 23 (14%) | 14 (17%) | 9 (11%) | 0.25‡ |

| FM in family | 57 (34%) | 27 (32%) | 30 (35%) | 0.55‡ |

| Use of medication in the last 3 months | ||||

| Pain medications | 149 (88%) | 73 (86%) | 76 (89%) | 0.64‡ |

| Hypnotics | 51 (30%) | 27 (32%) | 24 (28%) | 0.63‡ |

| Antidepressants | 20 (12%) | 8 (9%) | 12 (14%) | 0.48‡ |

| Anxiolytics | 8 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 6 (7%) | 0.28† |

Values are means (SD) or numbers (%).

*Mann-Whitney U test,

†Fisher’s exact test.

‡Pearson’s Χ2 test.

FM, fibromyalgia.

Of the 75 patients who attended the VTP, 67 (89%) completed five sessions or more; 21 (31%) of these patients completed all 10 sessions, 20 (30%) completed nine, and 9 (13%) completed eight sessions. The average attendance rate was 7.5 sessions. Thirty-two patients (43%) attended the PA intervention after the VTP, but only 14 patients participated more than 12 times during the 12-week programme. The data collection was completed by 160 (94%) at 3 months and 153 (90%) at 12 months. Recruitment of patients started in September 2016 and ended in August 2018. Electronic data collection started in February 2017 and ended in September 2019 when the complete 12-month follow-up data were attained.

Patient Global Impression of Change

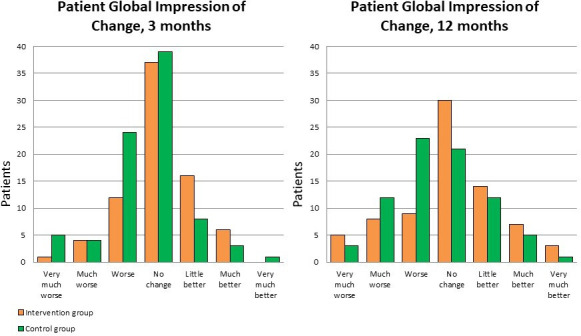

The median PGIC score was 4 (range 1–7) in both groups at 3-month and 12-month follow-up. However, we found statistically significant differences between the groups in distribution of the PGIC scores at 3-month follow-up (p=0.01), but not at 12-month follow-up (p=0.06). The distribution across all response categories is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

The distribution of PGIC scores. PGIC, Patient Global Impression of Change.

There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention group and the control group at 3-month and 12-month follow-ups when the PGIC was dichotomised into ‘Less than much better’ and ‘Much better’. At 12-month follow-up, 13% in the intervention group reported ‘Much better’ compared with 8% in the control group (table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of intervention, primary outcome: Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC)

| PGIC | 3 months | 12 months | P value | |||

| Intervention (n=76) | Control (n=84) | P value | Intervention (n=76) | Control (n=77) | ||

| Much better (scores 6 and 7), n (%) | 6 (7.9) | 4 (4.8) | 0.52* | 10 (13.2) | 6 (7.8) | 0.28† |

*Fisher’s exact test.

†Pearson’s Χ2 test.

Secondary outcomes

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at 12-month follow-up in any disease-related outcomes (table 3). However, there was a statistically significant improvement in favour of the intervention group in ‘general tendency to be mindful’. Moreover, there was a statistically significant difference between groups in ‘perceived benefits of exercise’ due to a small deterioration in the control group (table 3). The numbers of people working, assessed by the WPAI:GH, were 56 (67%) at baseline and 48 (64%) at 12-month follow-up in the intervention group, compared with 52 (61%) at baseline and 50 (64%) at 12-month follow-up in the control group.

Table 3.

Effects of intervention, secondary outcomes estimated by ANCOVA adjusted for baseline scores

| Intervention (n=76) mean (SD) |

Control (n=77) mean (SD) |

Baseline-adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |

| Pain (NRS 0–10, 0=no pain) | ||||

| Baseline | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.8 (1.9) | – | – |

| 3 months | 6.4 (1.7) | 6.6 (1.8) | 0.30 (−0.15 to 0.75) | 0.19 |

| 12 months | 5.8 (2.1) | 6.4 (1.8) | 0.55 (−0.00 to 1.11) | 0.05 |

| Fatigue (NRS 0–10, 0=no fatigue) | ||||

| Baseline | 7.5 (2.0) | 7.4 (2.0) | – | – |

| 3 months | 7.2 (1.9) | 7.1 (2.2) | −0.03 (−0.60 to 0.54) | 0.92 |

| 12 months | 6.8 (2.3) | 6.8 (2.3) | 0.12 (−0.56 to 0.80) | 0.72 |

| Sleep (NRS 0–10, 0=no sleep) | ||||

| Baseline | 6.8 (2.3) | 7.1 (2.5) | – | – |

| 3 months | 6.6 (2.5) | 6.9 (2.5) | 0.27 (−0.42 to 0.97) | 0.44 |

| 12 months | 6.5 (2.5) | 6.3 (2.5) | −0.24 (−0.99 to 0.50) | 0.52 |

| Psychological distress (GHQ-12, mean sum score, 0–36, 0=no distress) | ||||

| Baseline | 16.5 (6.6) | 19.2 (6.8) | – | – |

| 3 months | 13.4 (6.5) | 16.5 (7.0) | 1.57 (−0.37 to 3.50) | 0.11 |

| 12 months | 14.8 (6.8) | 16.6 (6.9) | 1.03 (−1.08 to 3.14) | 0.34 |

| Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (mean sum score, 39–195, low to high) | ||||

| Baseline | 119 (17.2) | 113 (16.9) | – | – |

| 3 months | 124 (19.1) | 118 (16.3) | −1.07 (−4.73 to 2.58) | 0.56 |

| 12 months | 126 (17.6) | 118 (16.3) | −4.72 (−8.57 to −0.9) | 0.02 |

| Physical activity (0–15, 0=inactive) | ||||

| Baseline | 3.0 (2.4) | 2.8 (1.8) | – | – |

| 3 months | 2.3 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.9) | 0.53 (−0.04 to 1.10) | 0.07 |

| 12 months | 2.9 (2.3) | 2.8 (1.8) | 0.10 (−0.60 to 0.79) | 0.78 |

| Motivation and barriers for physical activity | ||||

| Self-efficacy (4–20, low to high) | ||||

| Baseline | 12.0 (2.9) | 12.0 (3.2) | – | – |

| 3 months | 12.5 (3.1) | 12.6 (3.1) | 0.08 (−0.70 to 0.86) | 0.84 |

| 12 months | 13.1 (3.5) | 12.8 (3.1) | −0.33 (−1.27 to 0.62) | 0.50 |

| Barriers (3–15, low to high) | ||||

| Baseline | 12.1 (2.4) | 12.1 (2.0) | – | – |

| 3 months | 11.8 (2.3) | 11.8 (1.9) | −0.00 (−0.48 to 0.47) | 0.99 |

| 12 months | 12.2 (2.4) | 12.2 (1.7) | −0.07 (−0.61 to 0.46) | 0.79 |

| Benefits (5–25, low to high) | ||||

| Baseline | 20.4 (3.2) | 21.1 (2.7) | – | – |

| 3 months | 20.3 (3.0) | 20.4 (2.7) | −0.19 (−0.89 to 0.50) | 0.59 |

| 12 months | 20.7 (3.0) | 20.1 (2.9) | −0.90 (−1.73 to −0.07) | 0.03 |

| Impact (8–40, low to high) | ||||

| Baseline | 28.8 (4.6) | 29.0 (4.8) | – | – |

| 3 months | 28.4 (4.8) | 28.5 (4.3) | 0.08 (−0.90 to 1.06) | 0.87 |

| 12 months | 28.9 (5.4) | 28.3 (4.6) | −0.49 (−1.63 to 0.65) | 0.40 |

| Work Productivity and Activity Impairment General Health | ||||

| Work impairment (0–10, 10=completely impaired) | ||||

| Baseline | 5.2 (2.5) | 6.2 (2.2) | – | – |

| 3 months | 5.1 (2.4) | 5.4 (2.5) | −0.15 (−1.05 to 0.76) | 0.75 |

| 12 months | 4.9 (3.2) | 5.3 (2.9) | 0.73 (−0.58 to 2.03) | 0.27 |

| Daily activity impairment (0–10, 10=completely impaired) | ||||

| Baseline | 7.0 (2.0) | 7.1 (1.9) | – | – |

| 3 months | 6.9 (1.7) | 6.7 (2.3) | −0.25 (−0.83 to 0.34) | 0.41 |

| 12 months | 6.3 (2.5) | 6.5 (2.2) | 0.07 (−0.65 to 0.79) | 0.84 |

| EQ-5D-5L | ||||

| Index (0–1, 1=perfect health) | ||||

| Baseline | 0.51 (0.2) | 0.47 (0.2) | – | – |

| 3 months | 0.55 (0.2) | 0.53 (0.2) | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.09) | 0.86 |

| 12 months | 0.54 (0.2) | 0.50 (0.2) | 0.04 (−0.03 to 0.11) | 0.48 |

| VAS (0–100, 100=as good as it could be) | ||||

| Baseline | 44.6 (16.5) | 41.61 (17.0) | – | – |

| 3 months | 46.4 (16.1) | 51.5 (21.7) | −5.1 (−12.10 to 1.90) | 0.03 |

| 12 months | 49.0 (20.6) | 46.8 (18.5) | 2.19 (−4.67 to 9.05) | 0.77 |

ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; GHQ-12, General Health Questionnaire-12; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Harms

A total of 34 patients reported adverse events: 21 (28%) in the intervention group and 13 (17%) in the control group. Increased pain and fatigue were the most frequent adverse events. Thirteen (nine in the intervention group and four in the control group) related the events to medication; 21 (12 in intervention and 9 in control) to PA; 4 in the intervention group related the events to the VTP; 2 (one in intervention and one in control) related the events to alternative treatment.

Discussion

In this pragmatic randomised controlled trial, we examined the effects of a multicomponent rehabilitation programme for patients with FM. The study demonstrated that a mindfulness-based and acceptance-based intervention, the VTP, followed by PA counselling in patients with recently diagnosed FM was not more effective than treatment as usual. Only 13% in the intervention group reported clinically relevant improvement in self-perceived health status at 12-month follow-up compared with 8% in the control group. We did not observe differences between the groups in any disease-related secondary outcomes. However, there were statistically significant differences between groups in ‘tendency to be mindful’ and ‘perceived benefits of exercise’ in favour of the intervention group. The latter was due to a slight deterioration in the control group.

The results of this trial both negate and support earlier studies on the VTP for patients with FM. One randomised controlled trial in patients with musculoskeletal pain conditions, including FM, demonstrated substantial health improvements.19 In contrast, a longitudinal study in patients with IA and FM showed improvements in the IA group, but not in the FM group.21 Based on the latter study, it was hypothesised that the lack of effects in patients with FM might have been related to living with distressing symptoms over a long time without receiving any diagnosis. The present study aimed to improve the management of FM by following the EULAR recommendations for management of FM in a Norwegian context. We assumed that offering patients who had been recently diagnosed with FM a mindfulness-based and acceptance-based intervention might help them overcome some of their internal barriers to PA before they attended a PA intervention. However, we found no support for this assumption.

There were statistically significant differences between the groups in distribution of the PGIC scores at 3-month follow-up, but not at 12 months. This corresponds to other studies on mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions that have shown beneficial short-term effects, but no evidence for long-term effects.10 11 Our primary outcome, the PGIC scale, was dichotomised to distinguish between those who reported clinically relevant improvement in self-perceived health and those who did not. This has also been performed in previous studies, in which clinically relevant improvements have been shown.33 34 However, we did not find any clinically relevant differences between the groups in our study. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses on mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions have shown small-to-moderate beneficial effects on pain, sleep quality and health-related quality of life for patients with FM.10–13 In the present study, we did not see any of these effects. However, we found a statistically significant effect in ‘tendency to be mindful’. Improvement in mindfulness may be associated with enhanced mental health outcomes.39 46 Longer follow-up may be needed to see if this improvement will result in effects in other outcomes, such as perceived health status and PA.

As many as 57% of the patients never attended the HLC intervention, and they did not report any increase in PA at 12-month follow-up. Twelve of the 32 patients who took part in the HLC intervention reported adverse events, such as increased pain and fatigue, which may have been one reason for quitting the training. This corresponds to other studies, which have shown that many patients report PA to be challenging, and that adherence to exercise interventions is poor.18 47–49 A recent systematic review showed that PA should be tailored to individual characteristics to be effective.50 Given the varied clinical picture associated with FM, the initial objective of the HLC intervention was to adapt the PA to each patient’s physical condition and individual preferences. The patients reported the type of PA they performed in general terms, such as walking, strength training, cycling, spinning, etc. A limitation of our study is that we did not monitor to which degree the physiotherapists at the HLC adapted the PA to the individual patient’s condition, nor did we monitor if the patients experienced that the PA was individually tailored. Further studies are needed to explore ways to improve adherence to PA.

Because we wanted to investigate if it was possible to prevent work loss and improve work participation, we excluded patients that had been out of work for more than 2 years. Long-term absence from work due to illness has been identified as a risk factor for transition into disability pension.51 52 Seventy-one per cent of the patients in our study had paid work. Previous studies have shown that non-working patients with FM have more severe symptoms than working patients.53 54 Despite the high number of workers in our study, the patients reported high symptom burden, in terms of pain, fatigue and psychological distress.

Because we assumed that higher age might be associated with more comorbid conditions, we defined 50 years as the upper age limit for inclusion. Nevertheless, the median number of comorbidities in the included patients was 2.

Although we intended to capture patients with FM at an early stage of their disease, the included patients reported median symptoms duration of 8 years. These findings, although contrary to our expectations, correspond to other studies, which have shown that patients wait a significant time before presenting symptoms to a physician.55 Further, there may be a delay in diagnosis in primary healthcare due to an overlap of symptoms with other conditions and patients may have difficulties in communicating their symptoms.56 Other reasons for the delay in diagnosis and treatment may be lack of knowledge and understanding of FM from primary care physicians.57

This study was conducted according to a predefined published protocol.23 It was well powered, and all included patients were allocated to the groups to which they were randomised, ensuring valid treatment comparisons and assessment of treatment effects.58 The losses to follow-up were within our assumption of 10%. We had predefined that patients needed to attend at least 50% of the sessions to expect effects of the VTP intervention, and nearly 90% attended more than half of the VTP sessions.23 This attendance rate is comparable with other studies on mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions.13 The percentage of patients with complete follow-up data was high. The VTP facilitators were certified and followed a manualised programme, which improves transparency and replication.59 Moreover, the 12-month follow-up time was relatively long, and in line with what has been asked for in previous research.13

Several limitations need to be mentioned. First, before randomisation, all study participants received a short patient education session, which is recommended as a first-line intervention by the EULAR recommendations. This might have served as a validation of the FM diagnosis and may have provided the patients with knowledge and information about possible coping strategies. The control group could include strategies and activities at their own initiative. We did not monitor the content of ‘treatment as usual’ in the control group other than PA. Thus, we do not know if the patients had initiated beneficial self-management strategies during the control period.

Second, our study was a pragmatic randomised controlled trial, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the effects of the various interventions and to interpret the lack of effects. Moreover, we did not monitor the adherence to the homework between the VTP sessions. Consequently, we do not know to what extent the patients practised mindfulness training and integrated the training in their daily life. A recent review on mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions showed a small but significant association between the extent of formal practice and positive intervention outcomes.60 It is recommended that future research should adopt a standardised approach for monitoring home practice across mindfulness-based and acceptance-based interventions.61 Further, we included already existing HLCs in the communities. The activities offered vary between centres, and consequently, it was not possible to standardise the frequency, intensity, duration, progression or type of exercise. Moreover, the HLCs offer PA counselling at daytime only, making the intervention challenging to combine with a daytime job. Subsequently, a PA intervention with more flexible access might have increased the patient participation.

Third, we did not include any coping measures, such as self-efficacy, to assess the coping with their symptoms. We used the GHQ-12 to assess mental health status because this was found to be sensitive to change in previous studies on the VTP. The GHQ-12 does not capture more severe symptoms of depression and anxiety but is a widely used instrument to assess psychological distress.

Finally, we could have applied other statistical analyses, such as linear mixed models rather than ANCOVA, to estimate effects. However, ANCOVA was chosen because it has shown great power and low variability when compared with other traditional analyses approaches, and it is regarded as a preferred analysis when post-treatment assessments adjusted for the pretreatment assessments are measured.62 63 We did not adjust for multiple comparisons.

This study has demonstrated that a multicomponent rehabilitation programme combining recent diagnosis and patient education with a mindfulness-based and acceptance-based intervention followed by PA counselling was not more effective than recent diagnosis, patient education and treatment as usual for patients with FM.

There was a high drop-out rate from the PA intervention. Further, studies on how to adapt and tailor PA interventions to patients with FM are needed.

Our intention to include patients at an early stage of the disease was not fulfilled. The patients reported high symptom burden and had a median symptom duration of 8 years. Thus, future research should aim at including patients with more recent disease onset and explore the effects of prompt diagnosis and patient education.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the patients who have participated and contributed to this study. We would also like to thank Oddfrid Nesse, Ingrid Helle Trana, Ann-Grete Dybvik Akre, Ida Sjørbotten, Linda Ann Rørkoll, Ingunn Tveit Nafstad, Bente Dreiem Løken, Marianne Iversen Mejia and Iren Folkem for having facilitated the Vitality Training groups. Further, we thank the Healthy Life Centres in Ullensaker, Eidsvoll, Nannestad, Hurdal, Gjerdrum, Nes, Oslo and Bærum. Finally, we want to thank the service user, Astrid Kristine Andreassen.

Footnotes

Contributors: KBH and HAZ contributed to the initial design of the project, and all authors contributed to the conception of the study. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by TH, SAP and GS. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TH and all authors commented and revised previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Norwegian South-Eastern Regional Health Authority (grant number 2016015).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Study design, information strategy, written consent formula and data security are approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2015/2447/REK sør-øst A).

References

- 1.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, et al. The American College of rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:600–10. 10.1002/acr.20140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walitt B, Nahin RL, Katz RS, et al. The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the 2012 National health interview survey. PLoS One 2015;10:e0138024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: an overview. Am J Med 2009;122:S3–13. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:318–28. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verbunt JA, Pernot DHFM, Smeets RJEM. Disability and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:8. 10.1186/1477-7525-6-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marques AP, Santo AdeSdoE, Berssaneti AA, et al. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: literature review update. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed 2017;57:356–63. 10.1016/j.rbre.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes SM, Myhal GC, Thornton JF, et al. Fibromyalgia and the therapeutic relationship: where uncertainty meets attitude. Pain Res Manag 2010;15:385-91. 10.1155/2010/354868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armentor JL. Living with a contested, Stigmatized illness: experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res 2017;27:462–73. 10.1177/1049732315620160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nüesch E, Häuser W, Bernardy K, et al. Comparative efficacy of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions in fibromyalgia syndrome: network meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:955–62. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Häuser W, Bernardy K, Arnold B, et al. Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:216–24. 10.1002/art.24276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauche R, Cramer H, Dobos G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction for the fibromyalgia syndrome. J Psychosom Res 2013;75:500–10. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernardy K, Klose P, Welsch P, et al. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of cognitive behavioural therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome - A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pain 2018;22:242–60. 10.1002/ejp.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haugmark T, Hagen KB, Smedslund G, et al. Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for patients with fibromyalgia - A systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;24:CD011336. 10.1002/14651858.CD011336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Bath B, et al. Exercise for adults with fibromyalgia: an umbrella systematic review with synthesis of best evidence. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2014;10:45–79. 10.2174/1573403x10666140914155304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Häuser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, et al. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther 2010;12:R79. 10.1186/ar3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perrot S, Russell IJ. More ubiquitous effects from non-pharmacologic than from pharmacologic treatments for fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis examining six core symptoms. Eur J Pain 2014;18:1067–80. 10.1002/ejp.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Mixed exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;14. 10.1002/14651858.CD013340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haugli L, Steen E, Laerum E, et al. Learning to have less pain - is it possible? A one-year follow-up study of the effects of a personal construct group learning programme on patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Educ Couns 2001;45:111–8. 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00200-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zangi HA, Mowinckel P, Finset A, et al. A mindfulness-based group intervention to reduce psychological distress and fatigue in patients with inflammatory rheumatic joint diseases: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:911–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zangi HA, Finset A, Steen E, et al. The effects of a vitality training programme on psychological distress in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases and fibromyalgia: a 1-year follow-up. Scand J Rheumatol 2009;38:231–4. 10.1080/03009740802474680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zangi HA, Hauge M-I, Steen E, et al. "I am not only a disease, I am so much more". Patients with rheumatic diseases' experiences of an emotion-focused group intervention. Patient Educ Couns 2011;85:419–24. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haugmark T, Hagen KB, Provan SA, et al. Effects of a community-based multicomponent rehabilitation programme for patients with fibromyalgia: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021004. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:e1–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, et al. 2016 revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:319-329. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York.: Delacorte, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steen E, Haugli L. The body has a history: an educational intervention programme for people with generalised chronic musculoskeletal pain. Patient Educ Couns 2000;41:181–95. 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00077-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundahl B, Burke BL. The effectiveness and applicability of motivational interviewing: a practice-friendly review of four meta-analyses. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:1232–45. 10.1002/jclp.20638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Christensen R, et al. Toward development of a fibromyalgia responder index and disease activity score: OMERACT module update. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1487–95. 10.3899/jrheum.110277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choy EH, Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, et al. Content and criterion validity of the preliminary core dataset for clinical trials in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2330–4. 10.3899/jrheum.090368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beasley M, Prescott GJ, Scotland G, et al. Patient-reported improvements in health are maintained 2 years after completing a short course of cognitive behaviour therapy, exercise or both treatments for chronic widespread pain: long-term results from the MUSICIAN randomised controlled trial. RMD Open 2015;1:e000026. 10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rampakakis E, Ste-Marie PA, Sampalis JS, et al. Real-Life assessment of the validity of patient global impression of change in fibromyalgia. RMD Open 2015;1:e000146. 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McBeth J, Prescott G, Scotland G, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy, exercise, or both for treating chronic widespread pain. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:48–57. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. J Man Manip Ther 2009;17:163–70. 10.1179/jmt.2009.17.3.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malt UF, Mogstad TE, Refnin IB. [Goldberg's General Health Questionnaire]. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1989;109:1391–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nerdrum P, Geirdal Amy Østertun. Psychological distress among young Norwegian health professionals. Professions and Professionalism 2014;4. 10.7577/pp.526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldberg D, Williams P. A User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ. Windsor (UK: NFER Nelson Publishing Company, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dundas I, Vøllestad J, Binder P-E, et al. The five factor mindfulness questionnaire in Norway. Scand J Psychol 2013;54:250–60. 10.1111/sjop.12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurtze N, Rangul V, Hustvedt B-E, et al. Reliability and validity of self-reported physical activity in the Nord-Trøndelag health study: HUNT 1. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:52–61. 10.1177/1403494807085373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gecht MR, Connell KJ, Sinacore JM, et al. A survey of exercise beliefs and exercise habits among people with arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 1996;9:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reilly MC, Gooch KL, Wong RL, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness of the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire in ankylosing spondylitis. Rheumatology 2010;49:812–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1717–27. 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Obradovic M, Lal A, Liedgens H. Validity and responsiveness of EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) versus Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) questionnaire in chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:110. 10.1186/1477-7525-11-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.StataCorp . Stata statistical software. 14 ed. Texas, USA: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baer RA, Carmody J, Hunsinger M. Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Clin Psychol 2012;68:755–65. 10.1002/jclp.21865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O'Dwyer T, Maguire S, Mockler D, et al. Behaviour change interventions targeting physical activity in adults with fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 2019;39:805–17. 10.1007/s00296-019-04270-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Álvarez-Gallardo IC, Bidonde J, Busch A, et al. Therapeutic validity of exercise interventions in the management of fibromyalgia. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2019;59:828–38. 10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08897-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Richards SCM, Scott DL. Prescribed exercise in people with fibromyalgia: parallel group randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;325:185. 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Estévez-López F, Maestre-Cascales C, Russell D, et al. Effectiveness of exercise on fatigue and sleep quality in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102:752–61. 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gjesdal S, Bratberg E. Diagnosis and duration of sickness absence as predictors for disability pension: results from a three-year, multi-register based* and prospective study. Scand J Public Health 2003;31:246–54. 10.1080/14034940210165154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, et al. Sickness absence as a risk factor for job termination, unemployment, and disability pension among temporary and permanent employees. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:212–7. 10.1136/oem.2005.020297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palstam A, Mannerkorpi K. Work ability in fibromyalgia: an update in the 21st century. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2017;13:180–7. 10.2174/1573397113666170502152955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henriksson CM, Liedberg GM, Gerdle B. Women with fibromyalgia: work and rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2005;27:685–94. 10.1080/09638280400009089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gendelman O, Amital H, Bar-On Y, et al. Time to diagnosis of fibromyalgia and factors associated with delayed diagnosis in primary care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2018;32:489–99. 10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Golden A, D'Arcy Y, Masters ET, et al. Living with fibromyalgia: results from the functioning with fibro survey highlight patients' experiences and relationships with health care providers. Nursing: Research and Reviews 2015;5:109–17. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choy E, Perrot S, Leon T, et al. A patient survey of the impact of fibromyalgia and the journey to diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:102. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Armijo-Olivo S, Warren S, Magee D. Intention to treat analysis, compliance, drop-outs and how to deal with missing data in clinical research: a review. Phys Ther Rev 2009;14:36–49. 10.1179/174328809X405928 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parsons CE, Crane C, Parsons LJ, et al. Home practice in Mindfulness-Based cognitive therapy and Mindfulness-Based stress reduction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of participants' mindfulness practice and its association with outcomes. Behav Res Ther 2017;95:29–41. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lloyd A, White R, Eames C, et al. The utility of Home-Practice in Mindfulness-Based group interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness 2018;9:673–92. 10.1007/s12671-017-0813-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Connell NS, Dai L, Jiang Y, et al. Methods for analysis of pre-post data in clinical research: a comparison of five common methods. J Biom Biostat 2017;8:1–8. 10.4172/2155-6180.1000334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Valente MJ, MacKinnon DP. Comparing models of change to estimate the mediated effect in the pretest-posttest control group design. Struct Equ Modeling 2017;24:428–50. 10.1080/10705511.2016.1274657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046943supp001.pdf (56.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.