Abstract

Jasmonic acid (JA) plays an important role in regulating leaf senescence. However, the molecular mechanisms of leaf senescence in apple (Malus domestica) remain elusive. In this study, we found that MdZAT10, a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor (TF) in apple, markedly accelerates leaf senescence and increases the expression of senescence-related genes. To explore how MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence, we carried out liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry screening. We found that MdABI5 physically interacts with MdZAT10. MdABI5, an important positive regulator of leaf senescence, significantly accelerated leaf senescence in apple. MdZAT10 was found to enhance the transcriptional activity of MdABI5 for MdNYC1 and MdNYE1, thus accelerating leaf senescence. In addition, we found that MdZAT10 expression was induced by methyl jasmonate (MeJA), which accelerated JA-induced leaf senescence. We also found that the JA-responsive protein MdBT2 directly interacts with MdZAT10 and reduces its protein stability through ubiquitination and degradation, thereby delaying MdZAT10-mediated leaf senescence. Taken together, our results provide new insight into the mechanisms by which MdZAT10 positively regulates JA-induced leaf senescence in apple.

Subject terms: Jasmonic acid, Abiotic

Introduction

Plant leaf senescence, the last stage of leaf development, is accompanied by a series of physiological and biochemical changes, including the degradation of intracellular organelles and hydrolysis of macromolecules for the relocation of nutrients and energy into newly developing tissues or storage organs1. It is important to understand how plants regulate the senescence process to prevent major yield losses in agriculture. The leaf senescence process can be triggered and promoted by unfavorable environmental cues, including extended darkness, drought, and pathogen attack2–4, and by endogenous factors such as age, developmental stage, and plant hormones5,6. Leaf senescence inhibits photosynthetic capacity and thus decreases crop quality and yield7,8. Therefore, delaying leaf senescence offers potential economic benefits7.

Plant hormones are known to affect the timing of leaf senescence. Hormones such as abscisic acid (ABA), jasmonic acid, ethylene (ET), and salicylic acid (SA) accelerate the leaf senescence process, whereas auxin, cytokinins (CKs), and gibberellic acid (GA) delay leaf senescence9. JA is a lipid-derived phytohormone that is ubiquitous in the plant kingdom and plays essential roles in the regulation of multiple physiological processes in plants, including root growth, leaf senescence, and the response to wounding and pathogens10–13. In Arabidopsis, the endogenous JA content is higher in senescent leaves than in nonsenescent leaves14. Consistent with this increased JA content, several genes involved in the JA biosynthesis pathway, such as LIPOXYGENASE 1/3/4 (LOX1/3/4) and ALLENE OXIDE CYCLASE 1 (AOC1), are also markedly upregulated during leaf senescence14. In response to JA, the JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) proteins interact with CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 (COI1), a component of the SCFCOI1 complex15,16. The JAZ proteins are then degraded by the 26S proteasome, thereby releasing downstream JA-responsive genes such as the bHLH transcription factor MYC216,17. MYC2 positively regulates JA-induced leaf senescence by directly activating the expression of SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE 29 (SAG29), and MYC2 interacts with the bHLH subgroup IIId TFs bHLH03, 13, 14, and 17, which antagonistically regulate leaf senescence18.

A large number of genetic and transcriptome studies have shown that TFs regulate the leaf senescence process10,19. Some TFs play critical roles in leaf senescence regulatory networks; these TFs include members of the bHLH, NAC, MYB, WRKY, bZIP, C2H2-type zinc finger, and AP2⁄EREBP families19,20. C2H2-type zincfinger proteins (ZFPs) are a large family of transcriptional regulators in plants21. Various C2H2-type zinc finger TFs are known to be involved in plant development and stress responses22,23. Most ZFPs contain one to four highly conserved QALGGH motifs24. In addition, a few ZFPs contain C-terminal ERF-associated amphiphilic repression (EAR) motifs, which function as transcriptional repressors25,26. Several members of the C2H2-type zinc finger TF family were found to be up- or downregulated during natural leaf senescence19, indicating that C2H2-type zinc finger TFs may participate in leaf senescence. Arabidopsis zinc-finger protein 2 (AZF2), a C2H2-type zinc finger TF, positively regulates age-triggered leaf senescence27.

ABSCISIC ACID-INSENSITIVE5 (ABI5), a basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-type TF, positively regulates ABA signaling and participates in seed germination, abiotic stress tolerance, and leaf senescence4,28,29. Previous studies have revealed that ABI5 modulates leaf senescence by transcriptional regulation. ABI5 positively regulates dark-induced leaf senescence by directly repressing the expression of ABA-response protein (ABR)30 and activating the expression of the chlorophyll degradation genes NON-YELLOW COLORING1 (NYC1) and STAY-GREEN 1 (SGR1/NYE1)4. The bHLH TFs PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTORS 4/5 (PIF4/5) directly activate ABI5 during dark-induced senescence4. In rice (Oryza sativa), ONAC054 directly activates OsABI5 in response to leaf senescence31. A recent study found that MdABI5 is involved in ABA-induced leaf senescence32. These findings indicate that ABI5 plays a crucial role in the leaf senescence process.

Previous studies have identified several genes that promote or delay leaf senescence in apple33–35. In this study, we identified a C2H2-type zinc finger TF, MdZAT10, and demonstrated that it positively regulates leaf senescence in apple (Malus domestica). Further experiments showed that MdZAT10 interacts with MdABI5 and accelerates the MdABI5-mediated leaf senescence process. MdZAT10 was also found to accelerate JA-induced leaf senescence. We found a negative JA regulator, MdBT2, which interacts with MdZAT10 and modulates its stability, thereby repressing MdZAT10-mediated leaf senescence. In summary, we used protein–protein interactions to delineate the relationships among MdBT2, MdZAT10, and MdABI5 during leaf senescence.

Results

MdZAT10 positively regulates leaf senescence

The expression of a large number of C2H2-type TFs is markedly induced during natural senescence19. The MdZAT10 gene, a C2H2-type zinc finger TF in subclass C1-2i, is homologous to Arabidopsis STZ/ZAT10 (SALT TOLERANCE ZINC FINGER). The MdZAT10 (MDP0000198015) gene was identified by a BLAST search against the apple genome database (Apple Gene Function & Gene Family DataBase version 1.0). To identify proteins homologous to ZAT10, a phylogenetic tree containing sequences from 21 different plant species was constructed. All proteins contained two conserved zinc finger domains and an EAR motif, and MdZAT10 was highly homologous to PbZAT10 from Pyrus bretschneideri (Supplementary Fig. S1).

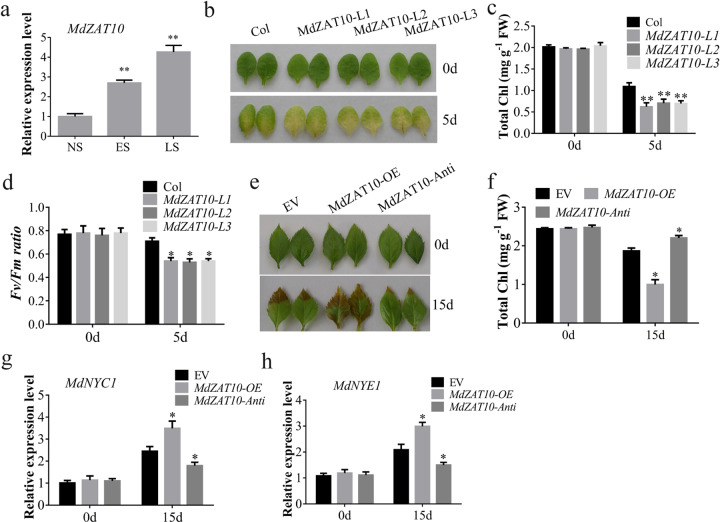

We measured the expression level of MdZAT10 in apple leaves at different developmental stages, including the nonsenescent (NS), early-senescent (ES), and late-senescent (LS) stages. MdZAT10 expression was higher in at ES and LS stages than at the NS stage (Fig. 1a). To confirm the function of MdZAT10 during leaf senescence, an MdZAT10 overexpression vector was transformed into Arabidopsis, generating three independent Arabidopsis lines (MdZAT10-L1, L2 and L3) (Supplementary Fig. S2). Detached leaves from transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings showed greater leaf yellowing than those from wild-type (Col) seedlings (Fig. 1b). Consistent with their differences in color, the leaves of the transgenic plants showed significant decreases in chlorophyll content and maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) (Fig. 1c, d). To further confirm these leaf senescence phenotypes, MdZAT10 overexpression and antisense suppression vectors were transformed into detached apple leaves using a transient expression system (Supplementary Fig. S2). Consistently, apple leaves overexpressing MdZAT10 exhibited early senescence, whereas apple leaves expressing MdZAT10 antisense suppression showed delayed senescence (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, apple leaves’ MdZAT10 overexpression and antisense suppression vectors also showed corresponding differences in chlorophyll content (Fig. 1f). We found that MdZAT10 overexpression increased the expression of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 in apple leaves (Fig. 1g, h). These results suggest that MdZAT10 positively regulates leaf senescence.

Fig. 1. MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence.

a MdZAT10 transcript level in late-senescent (LS), early-senescent (ES), and nonsenescent (NS) leaves. b Detached leaves from 3-week-old wild-type (Col) plants and three transgenic lines (MdZAT10-L1, L2, and L3) were incubated in 3 mM MES buffer in the dark for 5 days. c The chlorophyll content and d Fv/Fm before and after dark treatment were determined. e Leaf senescence phenotype and f the total chlorophyll content of apple leaves transiently expressing empty vector (EV), overexpressing MdZAT10 or MdZAT10 antisense vector in the dark for 15 days. g, h The expression levels of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 in apple leaves after 15 days of dark treatment. Asterisks indicate significant differences determined by t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

MdZAT10 interacts with the MdABI5 protein

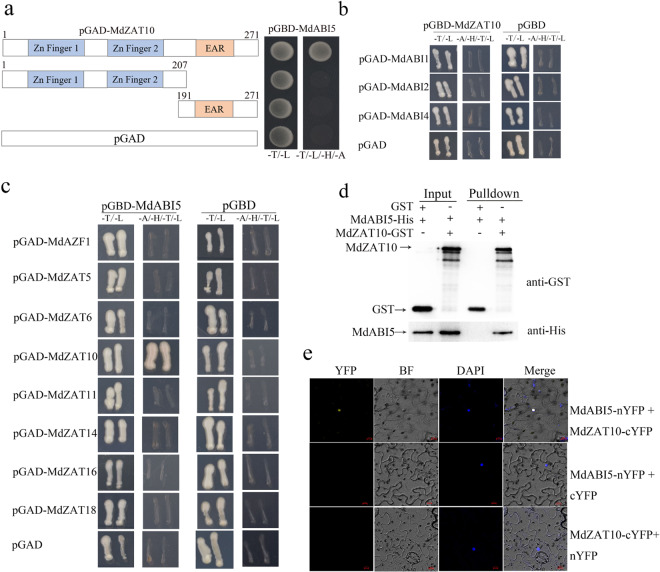

To further explore the mechanism by which MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence, a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) assay was carried out to screen proteins that interact with MdZAT10 using MdZAT10-GFP as bait. After screening, the MdABI5 protein (GenBank accession number: LOC103430245) was found to interact with MdZAT10, and a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay was performed to confirm this interaction. The full-length cDNA of MdZAT10 was fused to the pGAD424 vector as prey (pGAD-MdZAT10), and the full-length cDNA of MdABI5 was fused to the pGBT9 vector as bait (pGBD-MdABI5). The pGAD-MdZAT10 and pGBD-MdABI5 plasmids were cotransformed into yeast. The results showed an interaction between the MdZAT10 and MdABI5 proteins (Fig. 2a). To identify the regions in MdZAT10 that interact with MdAB15, MdZAT10 was divided into N-terminus (MdZAT10-N) and C-terminus (MdZAT10-C) fragments. These results indicated that the zinc finger domains and EAR motif of MdZAT10 are essential for the interaction between MdZAT10 and MdABI5 (Fig. 2a). MdZAT10 interacted with MdABI5, but not interacted with MdABI1, MdABI2, or MdABI4 (Fig. 2a, b); MdABI5 also specifically interacted with MdZAT10 but not with other MdZATs (Fig. 2c). In addition, we carried out an in vitro pull-down assay and found that MdABI5-His could be pulled down by the MdZAT10-GST fusion protein (Fig. 2d). Finally, in a BiFC assay, a strong yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fluorescence signal in the nuclei was observed only when MdZAT10-cYFP and MdABI5-nYFP were cotransformed into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves (Fig. 2e). These results indicated that MdZAT10 physically interacts with MdABI5.

Fig. 2. MdZAT10 physically interacts with MdABI5.

a A yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay showed that MdZAT10 interacts with MdABI5. Full-length MdZAT10 and truncated MdZAT10 sequences were cloned into the pGAD424 vector. Full-length MdABI5 was cloned into the pGBT9 vector. The empty pGAD vector was used as a negative control. b A Y2H assay showed that MdABIs (MdABI1, MdABI2, and MdABI4) and MdZAT10 interact. c A Y2H assay showed that MdABI5 interacts with MdZAT proteins (MdAZF1, MdZAT5, MdZAT6, MdZAT10, MdZAT11, MdZAT14, MdZAT16, and MdZAT18). d In vitro MdZAT10 and MdABI5 pull-down assay. The MdABI5-His protein was incubated with MdZAT10-GST and GST. Proteins pulled down with GST beads were detected using anti-GST and anti-His antibodies. e BiFC assay. The MdZAT10-cYFP and MdABI5-nYFP constructs were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and the fluorescence signal was observed by fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei are indicated by DAPI staining. Scale bars, 10 μm

MdABI5 promotes leaf senescence

Previous studies have reported that MdABI5 regulates ABA-induced leaf senescence32. We detected the expression level of MdABI5 in apple leaves at different developmental stages. The MdABI5 expression level was higher at the ES and LS stages than at the NS stage (Supplementary Fig. S3). To elucidate the role of ABI5 during leaf senescence, an MdABI5 overexpression vector was transformed into Arabidopsis, generating three individual transgenic lines (MdABI5-L1, L2, and L3) (Supplementary Fig. S2). MdABI5 overexpression clearly promoted leaf yellowing and reduced the chlorophyll content and Fv/Fm after 5 days in the dark (Supplementary Fig. S3). Furthermore, the MdABI5 overexpression and MdABI5 antisense suppression vectors were transiently transformed into detached apple leaves. Apple leaves that overexpressed MdABI5 showed a more severe senescence phenotype and lower chlorophyll content, whereas MdABI5 antisense suppression showed a delayed senescence phenotype and higher chlorophyll content (Supplementary Fig. S3). Previous studies have shown that ABI5 induces leaf senescence by directly regulating the expression of the chlorophyll degradation genes NYC1 and NYE14,31. In this study, the expression of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 was enhanced in apple leaves overexpressing MdABI5 (Supplementary Fig. S3). These results suggest that MdABI5 promotes leaf senescence.

MdZAT10 promotes MdABI5-regulated leaf senescence

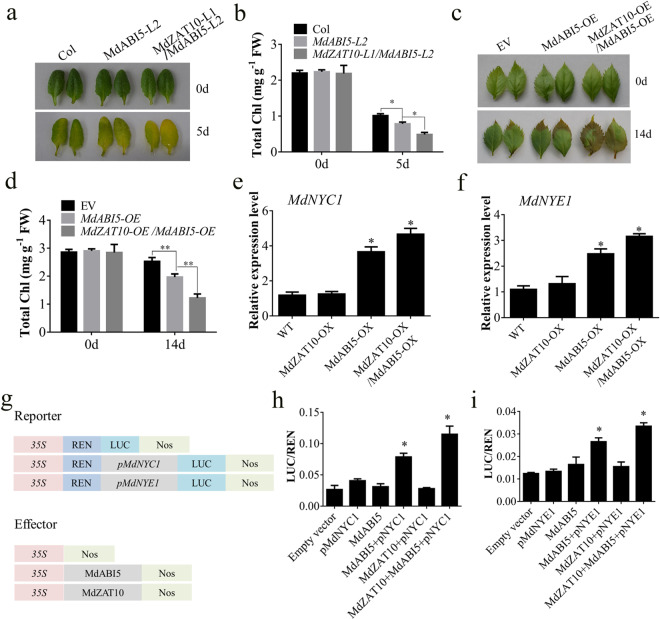

Given the interaction between MdZAT10 and MdABI5, we suspected that MdZAT10 participates in MdABI5-mediated leaf senescence. An Arabidopsis line overexpressing MdZAT10 was crossed with an Arabidopsis line overexpressing MdABI5. The resultant Arabidopsis plants overexpressing MdZAT10/MdABI5 turned yellow much faster and had less chlorophyll content than the plants overexpressing MdABI5 alone (Fig. 3a, b). Consistent with the observed phenotype in Arabidopsis, the overexpression of MdZAT10 increased the MdABI5-mediated leaf senescence in apple leaves (Fig. 3c, d). These results revealed that MdZAT10 accelerates MdABI5-promoted leaf senescence.

Fig. 3. MdZAT10 accelerates MdABI5-regulated leaf senescence.

a Leaf senescence phenotype and b total chlorophyll content of detached leaves from Col, MdABI5-L2, and MdZAT10-L1/MdABI5-L2 transgenic Arabidopsis floated on 3 mM MES buffer in the dark for 5 days. c Leaf senescence phenotype and d total chlorophyll content of apple leaves transiently expressing empty vector (EV), overexpressing MdABI5 alone or overexpressing MdZAT10 and MdABI5 that were floated on 3 mM MES buffer in the dark for 14 days. e, f The expression levels of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 in wild-type (WT) calli and MdABI5-OX, MdZAT10-OX, MdZAT10-OX/MdABI5-OX transgenic calli were measured by qRT-PCR assay. g Schematic diagram of reporter and effector constructs. h, i A luciferase assay showed that transient cotransformation of MdZAT10 and MdABI5 into tobacco leaves activated the expression of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1. The empty vector (SK + LUC) served as a negative control. The LUC/REN ratio represents the ability of MdABI5 to activate MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 expression. Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Therefore, we hypothesized that MdZAT10 affects the transcriptional activation of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 by MdABI5. To confirm this hypothesis, gene expression in the calli of transgenic apple plants overexpressing MdABI5 (MdABI5-OX) was detected (Supplementary Fig. S2). We found that MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 expression was dramatically upregulated in MdABI5-OX calli. The MdZAT10 overexpression vector was introduced into MdABI5-overexpressing transgenic calli, and the resultant MdZAT10-OX/MdABI5-OX transgenic calli showed markedly increased MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 expression (Fig. 3e, f). To confirm this result, we performed a transient expression assay in tobacco leaves. The promoter fragments of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 were fused into the pGreenII 0800-LUC reporter (pMdNYC1-LUC, pMdNYE1-LUC), and MdZAT10 and MdABI5 were fused into the effector construct pGreenII 62-SK (MdZAT10-SK, MdABI5-SK). We found that MdABI5 activated the promoters of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 and had a stronger effect when MdZAT10 and MdABI5 were cotransformed (Fig. 3g–i). These results indicated that the interaction between MdZAT10 and MdABI5 enhances the transcriptional activity of MdABI5 for MdNYC1 and MdNYE1.

MdZAT10 activates JA-induced leaf senescence

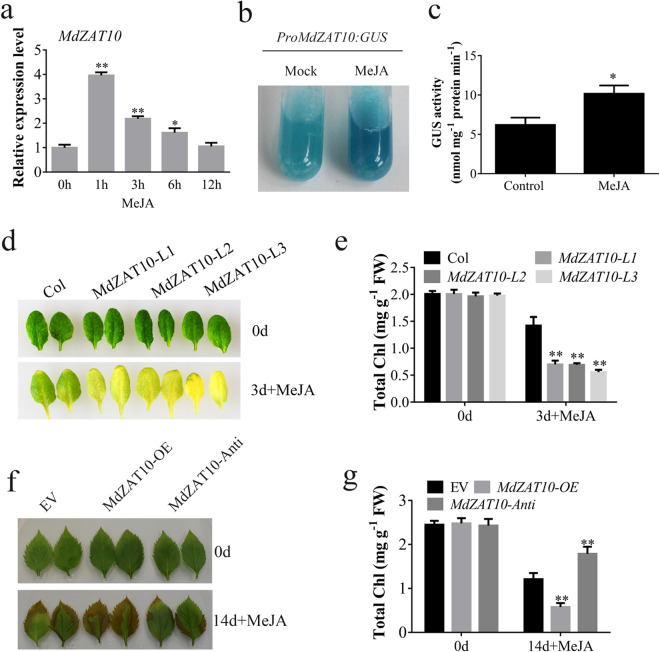

We also found that MdZAT10 was induced by MeJA (Fig. 4a). To further confirm the function of MdZAT10 in response to JA, we produced transgenic apple calli that expressed β-glucuronidase (GUS) driven by a region 2 kb upstream of the MdZAT10 gene. Histochemical staining showed that MeJA treatment significantly increased GUS activity (Fig. 4b, c). Detached leaves from MdZAT10 transgenic Arabidopsis showed increased leaf yellowing with MeJA treatment (Fig. 4d). The chlorophyll content in these leaves was significantly reduced compared to the leaves of Col plants (Fig. 4e). Consistently, upon MeJA treatment, apple leaves overexpressing MdZAT10 also exhibited early senescence, whereas MdZAT10 antisense suppression showed delayed senescence (Fig. 4f). Furthermore, leaves MdZAT10 overexpression and MdZAT10 antisense suppression showed different chlorophyll contents (Fig. 4g). These results indicated that MdZAT10 acts as a positive regulator of JA-induced leaf senescence in apple.

Fig. 4. MdZAT10 accelerates JA-induced leaf senescence.

a Transcript level of MdZAT10 in response to 100 μM MeJA. b GUS staining and c GUS activity in proMdZAT10::GUS transgenic calli with (MeJA) or without (Mock) 100 µM MeJA treatment for 12 h. d Leaf senescence phenotype and e chlorophyll content of detached leaves from 3-week-old Col and transgenic Arabidopsis MdZAT10-L1, L2, and L3 floated on 3 mM MES buffer with or without 100 μM MeJA for 3 days. f Leaf senescence phenotype and g chlorophyll content of apple leaves transiently expressing empty vector (EV), overexpressing MdZAT10 or MdZAT10 antisense vector floated on 3 mM MES buffer with or without 100 μM MeJA for 14 days. Asterisks indicate significant differences by t-test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

MdBT2 physically interacts with the MdZAT10 protein

In addition to its transcriptional regulation, we found that MdZAT10 was regulated at the posttranslational level in response to MeJA treatment. An in vitro protein degradation assay was performed to measure the protein level of MdZAT10 in response to MeJA treatment. The fusion protein MdZAT10-His was incubated with total protein from apple calli with or without MeJA treatment. The MdZAT10-His level dropped rapidly without MeJA treatment, but the drop in the MdZAT10 protein level was markedly abrogated by treatment with MeJA or the 26S proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Supplementary Fig. S4a). Furthermore, the MdZAT10 protein level in MdZAT10-overexpressing transgenic apple calli increased with MeJA treatment (Supplementary Fig. S4b). These results indicated that the presence of MeJA reduced MdZAT10 protein degradation by the 26S proteasome pathway.

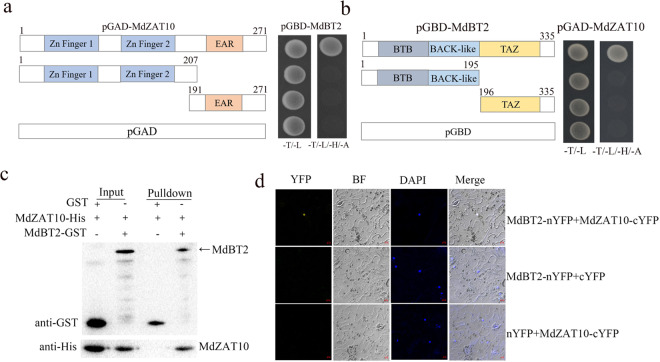

In addition to MdABI5, MdBT2 was screened as a potential interaction protein of MdZAT10. MdBT2 plays a key role in the regulation of JA-mediated leaf senescence36. We used a Y2H assay to determine whether MdBT2 and MdZAT10 interact. The full-length cDNA of MdBT2 was fused to the pGBT9 vector as bait (pGBD-MdBT2). Only yeast cells that contained pGAD-MdZAT10 and pGBD-MdBT2 grew well on -Trp/-Leu/-His/-Ade screening medium (Fig. 5a). To determine the regions of MdBT2 that interact with MdZAT10, MdBT2 was divided into N-terminal (MdBT2-N) and C-terminal (MdBT2-C) fragments. As shown in Fig. 5b, the BTB and TAZ domains of MdBT2 were indispensable for this interaction (Fig. 5b). To determine whether MdBT2 specifically interacts with MdZAT10, seven apple C2H2-type ZFPs (MdAZF1, MdZAT5, MdZAT6, MdZAT11, MdZAT14, MdZAT16, and MdZAT18) were fused to the prey vector pGAD424. However, all of them failed to interact with MdBT2 (Supplementary Fig. S5). MdBT1, MdBT2, MdBT3.1, and MdBT4 are important members of the apple MdBT protein family, and MdBT1 and MdBT2 interact with MdZAT10 (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 5. MdZAT10 physically interacts with MdBT2.

a, b A Y2H assay showed the interaction between MdZAT10 and MdBT2. Full-length and truncated MdZAT10 and MdBT2 sequences were cloned into the pGBD and pGAD vectors. c In vitro pull-down assay with MdZAT10 and MdBT2. The MdZAT10-His protein was incubated with GST-MdBT2 and GST. Proteins that were pulled down with GST beads were detected using anti-GST and anti-His antibodies. d BiFC assay. The MdZAT10-cYFP and MdBT2-nYFP constructs were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves, and the fluorescence signal in the nucleus was observed via fluorescence microscopy. Nuclei are indicated by DAPI staining. Scale bars, 10 μm

The MdBT2-MdZAT10 interaction was further verified by pull-down and BiFC assays. For the pull-down assay, the fusion protein MdBT2-GST and GST as a control were incubated with the fusion protein MdZAT10-His. Only MdBT2-GST could pull down MdZAT10-His (Fig. 5c). Next, we conducted a BiFC assay to further confirm the interaction. MdZAT10 and MdBT2 were fused to the C-terminal (cYFP) and N-terminal (nYFP) regions of yellow fluorescent protein, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5d, a strong fluorescence signal was detected in the nucleus when MdZAT10-cYFP and MdBT2-nYFP were injected into N. benthamiana leaves, whereas no YFP fluorescence signal was detected in the negative controls. Taken together, these results suggested that MdBT2 physically interacts with MdZAT10.

MdBT2 promotes degradation of the MdZAT10 protein

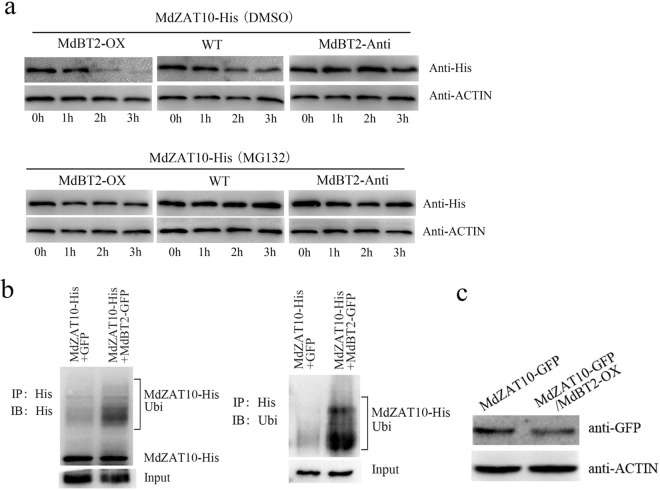

Recent studies have shown that MdBT2 generally negatively regulates the stability of its target proteins by ubiquitination37,38. We incubated the MdZAT10-His fusion protein with total protein from apple calli treated with or without the proteasome inhibitor MG132. The protein stability of MdZAT10 was enhanced by MG132, indicating that the MdZAT10 protein is degraded by the 26S proteasome pathway (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Then, we speculated that MdBT2 mediates MdZAT10 protein stability. To confirm this speculation, we generated transgenic MdBT2-overexpressing and antisense apple calli (MdBT2-OX and MdBT2-Anti). A cell-free MdZAT10 degradation assay was performed by incubating MdZAT10-His with total protein extracted from wild-type, MdBT2-OX, and MdBT2-Anti calli. As shown in Fig. 6a, degradation of the MdZAT10-His protein was much more rapid in the MdBT2-OX calli than in the wild-type calli, whereas MdZAT10-His degraded more slowly in the MdBT2-Anti calli. However, the proteasome inhibitor MG132 noticeably repressed degradation of the MdZAT10-His protein (Fig. 6a). These results indicated that the MdZAT10 protein is degraded by the 26S proteasome pathway, and a ubiquitination assay was performed to further verify this finding. The total protein extracted from MdBT2-GFP calli and GFP was incubated with the MdZAT10-His protein. The ubiquitinated MdZAT10-His protein was assessed using anti-His and anti-Ubi antibodies. A larger amount of high-molecular-mass MdZAT10-His was detected in the MdBT2-GFP + MdZAT10-His mixture (Fig. 6b). To confirm that MdBT2 promotes the degradation of MdZAT10 in vivo, we generated 35S::MdZAT10-GFP and 35S::MdZAT10-GFP + 35S::MdBT2-OX transgenic apple calli. Western blotting was performed with an anti-GFP antibody, and the MdZAT10-GFP protein abundance was lower in the 35S::MdZAT10-GFP + 35S::MdBT2-OX transgenic calli (Fig. 6c). Taken together, these results demonstrated that MdBT2 mediates degradation of the MdZAT10 protein.

Fig. 6. MdBT2 mediates MdZAT10 protein stability.

a Cell-free MdZAT10-His degradation assay. The MdZAT10-His fusion protein was incubated with total protein extracted from wild-type (WT), MdBT2-OX, and MdBT2-Anti transgenic calli for the indicated time periods. b MdBT2 ubiquitinated the MdZAT10-His protein in vivo. MdZAT10-His was immunoprecipitated using an anti-His antibody and then examined using anti-His and anti-Ubi antibodies. IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot; Ubi, ubiquitin. c The MdZAT10-GFP protein abundance in transgenic apple calli (MdZAT10-GFP and MdZAT10-GFP/MdBT2-OX) was assessed by immunoblotting using an anti-GFP antibody

MdBT2 delayed the MdZAT10-mediated leaf senescence

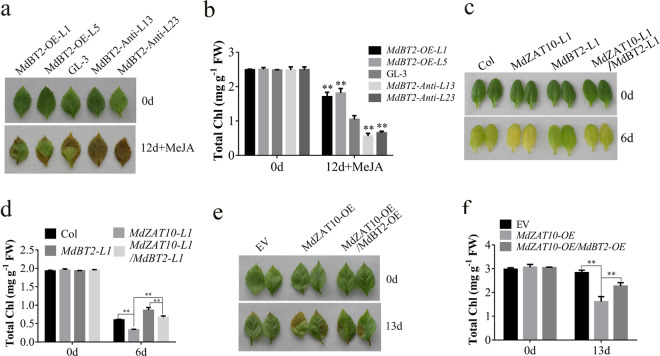

Previous studies have revealed that MdBT2 delays JA-induced leaf senescence36. Given that MdBT2 promoted the ubiquitination of MdZAT10, we speculated that MdBT2 is involved in the regulation of MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence. To investigate the potential function of MdBT2 in leaf senescence, we obtained three transgenic Arabidopsis lines (MdBT2-L1, L2, and L3) and transgenic apple plants overexpressing BT2 (MdBT2-OE-L1 and MdBT2-OE-L5) and BT2 antisense (MdBT2-Anti-L13 and MdBT2-Anti-L23) (Supplementary Fig. S2). MdBT2-overexpressing leaves from both Arabidopsis and apple showed a delayed senescence phenotype, whereas MdBT2 antisense plants showed accelerated JA-induced leaf senescence. The chlorophyll content was consistent with the phenotype (Fig. 7a, b and Supplementary Fig. S6). The Arabidopsis line overexpressing MdZAT10 was crossed with the Arabidopsis line overexpressing MdBT2. The resultant Arabidopsis plants overexpressing MdZAT10/MdBT2 showed delayed leaf senescence and enhanced chlorophyll content compared to those of plants overexpressing MdZAT10 (Fig. 7c, d). Consistent with these results, the overexpression of MdBT2 decreased the MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence phenotype in apple leaves and increased the chlorophyll content (Fig. 7e, f). Taken together, these results indicated that MdBT2 delayed the MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence.

Fig. 7. MdBT2 delayed the MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence.

a Leaf senescence phenotype and b chlorophyll content of detached leaves from wild-type (GL-3) and transgenic apple seedlings overexpressing MdBT2 (MdBT2-OE-L1, MdBT2-OE-L5) and MdBT2 antisense (MdBT2-Anti-L13, MdBT2-Anti-L23) that were floated on 3 mM MES buffer with 100 μM MeJA in the dark for 12 days. c Leaf senescence phenotype and d chlorophyll content of detached leaves from Col and transgenic Arabidopsis MdZAT10-L1, MdZAT10-L1/MdBT2-L1, and MdZAT10-L1/MdBT2-L2 that were floated on 3 mM MES buffer in the dark for 6 days. e Leaf senescence phenotype and f chlorophyll content of apple leaves transiently expressing empty vector (EV) or overexpressing MdZAT10 alone or MdZAT10 and MdBT2 were floated on 3 mM MES buffer in the dark for 13 days. Asterisks indicate significant differences at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Discussion

Leaf senescence is a complex process that involves the degradation of cellular components such as chloroplasts39. Accompanied by the degradation of massive amounts of chlorophyll, the most visible feature of plant senescence is leaf yellowing. Leaf senescence also affects crop productivity and plant fitness40. Many TFs show expression changes during leaf senescence41. In this study, we identified a C2H2-type zinc finger TF, MdZAT10, which positively regulates dark- and JA-induced leaf senescence.

STZ/ZAT10 is a member of the C2H2-type zinc finger TF family in subclass C1-2i that is involved in different abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, cold, and osmotic stresses42–46. In addition, it plays central roles in plant growth and development47. Previous studies showed that several C2H2-type zinc finger TFs are induced during senescence in Arabidopsis19,41. AZF2 functions as a positive regulator of age-dependent leaf senescence, and the loss of AZF2 function delayed leaf senescence27. Our results showed that MdZAT10 expression is higher in senescent leaves than in young leaves (Fig. 1), and overexpressing MdZAT10 accelerated leaf senescence (Fig. 1). We further explored how MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence and measured the expression levels of some senescence-related genes. MdZAT10-OX transgenic calli showed significantly enhanced the expression of senescence-related genes MdSAG29 and MdPAO and downregulated the expression of MdWRKY70 and MdAPX2 (Supplementary Fig. S7). Overexpression of SAG29 in Arabidopsis accelerated leaf senescence48. SAG29 acts as a target gene of MYC2 and is involved in JA-induced leaf senescence18. Pheophorbide a oxygenase (PAO) is induced by natural senescence, and the pao1 mutant exhibits a stay-green phenotype49. In Arabidopsis, WRKY70 negatively regulates age-dependent leaf senescence50. APX2 (ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE2) encodes cytosolic APX2, which plays a key role in removing H2O251. H2O2 is the most commonly used inducer of leaf senescence52. Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels have been reported to accelerate leaf senescence53–55. It is possible that MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence by reducing ROS scavenging or regulating the expression of senescence-related genes.

In addition, we found that MdZAT10 promotes JA-induced leaf senescence. MdZAT10 was induced with MeJA treatment, and MdZAT10-OX transgenic calli showed an enhanced expression of MdAOC1 and MdAOS (ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE) (Supplementary Fig. S7). AOC1 and AOS are associated with the JA biosynthesis pathway, and their expression is upregulated during leaf senescence10. In Arabidopsis, MYC2 binds the promoter of STZ/ZAT10 and regulates its expression56. STZ/ZAT10 and AZF2 can bind the LOX3 promoter to regulate the early response to MeJA57. These results indicate that STZ/ZAT10 is involved in JA signaling.

In addition to regulating downstream genes, MdZAT10 may regulate leaf senescence by interacting with other proteins. Here, we demonstrated that MdZAT10 interacts with MdABI5 (Fig. 2). ABI5 regulates dark- and ABA-induced leaf senescence4,30,32,58. Recent studies have indicated that ABI5 negatively regulates photosynthesis and chloroplast development under dark treatment4,58. RNA-seq data showed that StABI5 negatively regulates the expression level of photosynthesis-related genes58. ABI5 positively regulates leaf senescence by directly repressing the expression of ABR30 and activating the expression of NYC1 and NYE14,31,58. Here, our data showed that MdABI5-overexpressing transgenic plants showed enhanced leaf senescence and that MdABI5 antisense suppression delayed leaf senescence (Supplementary Fig. S3). MdABI5 activated the expression of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 in MdABI5-OX transgenic apple calli, further confirming the positive regulation of leaf senescence by MdAB15 (Fig. 3). We found that MdZAT10 accelerated MdABI5-mediated leaf senescence and increased the transcriptional activation of MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 by MdABI5 (Fig. 3). It is possible that MdZAT10 promotes leaf senescence by interacting with MdABI5 to affect the transcriptional activity of MdABI5 for target genes.

In addition to MdABI5, MdZAT10 also interacts with MdBT2. MdBT2 delayed JA-induced leaf senescence, and MdBT2 delayed the MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence (Fig. 7). These results indicated that MdBT2 plays an opposite role in MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence. Ubiquitination is widely involved in plant biological processes20. Several studies have shown the involvement of some E3 ligases in leaf senescence via the 26S proteasome pathway59. A recent study revealed that MdBT2 interacts with MdMYC2 and MdJAZ2, thereby regulating JA-induced leaf senescence36. BT2 is a component of the CRL3 complex that promotes target protein ubiquitination60. Our results showed that MdBT2 promoted the degradation of MdZAT10 and delayed JA-induced leaf senescence (Figs. 5–7). In the presence of JA, the degradation of MdBT2 was promoted36, thus releasing MdZAT10 from MdBT2-mediated degradation. Our results provide insight into the molecular mechanisms by which BT2 mediates JA-induced leaf senescence. These results imply that MdBT2 dynamically regulates JA-induced leaf senescence by regulating different target proteins. Although MdZAT10 interacts with MdBT2 and MdABI5, it is unclear whether these two interactions are related. The same region of MdZAT10 interacts with MdBT2 and MdABI5, and both MdBT2 and MdABI5 interact with full-length MdZAT10 (Figs. 2 and 5). It is possible that MdBT2 and MdABI5 competitively interact with MdZAT10 to antagonistically regulate leaf senescence, but this hypothesis requires further verification.

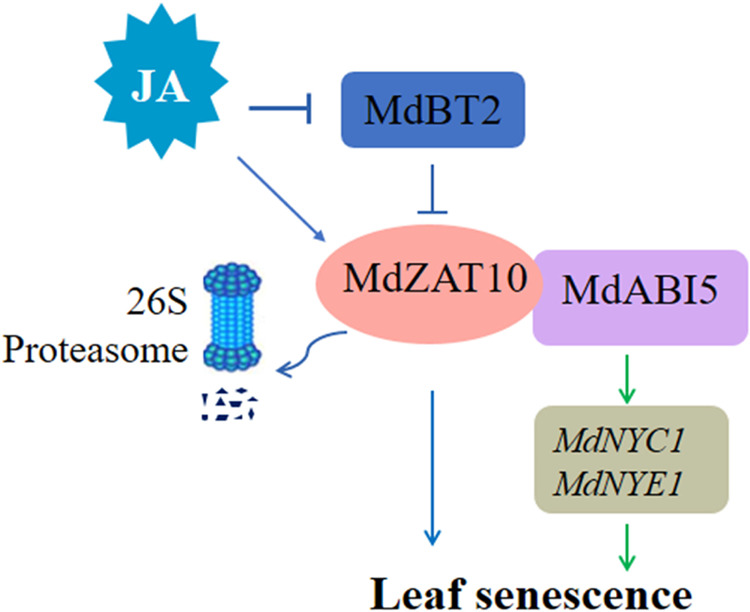

In summary, a working model to summarize the role of MdZAT10 in leaf senescence is proposed (Fig. 8). On the one hand, MdZAT10 positively regulates leaf senescence through its interaction with MdABI5, enhancing the transcriptional activity of MdABI5 for the chlorophyll degradation genes MdNYC1 and MdNYE1. On the other hand, in the absence of MeJA, MdBT2 interacts with MdZAT10 and ubiquitinates MdZAT10 to degrade MdZAT10, thereby negatively regulating MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence. In contrast, MdZAT10 is induced by exogenous MeJA, which promotes leaf senescence. MeJA accelerates the degradation of MdBT2, releasing MdZAT10, which contributes to JA-induced leaf senescence. In this study, we have characterized the role of MdZAT10 in the leaf senescence regulatory network through its direct interaction with MdBT2 and MdABI5.

Fig. 8. A working model of the role of MdZAT10 in apple leaf senescence.

On the one hand, MdZAT10 positively regulates leaf senescence by interacting with MdABI5, enhancing the transcriptional activity of MdABI5 for MdNYC1 and MdNYE1. On the other hand, in the absence of JA, MdBT2 interacts with MdZAT10 and ubiquitinates MdZAT10 to degrade MdZAT10, thereby negatively regulating MdZAT10-promoted leaf senescence. In the present of JA, JA accelerates the degradation of MdBT2, releasing MdZAT10, which contributes to JA-induced leaf senescence.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Tissue cultures of apple (Malus × domestica ‘GL-3’) were used in this study. The apple seedlings were subcultured on MS medium supplemented with 0.6 mg L−1 6-BA, 0.2 mg L−1 GA, and 0.2 mg L−1 NAA under long-day conditions (25 °C, 16/8 h light/dark) and subcultured at 30-day intervals. ‘Orin’ apple calli (Malus domestica Borkh.) were also used in this study. The calli were cultured on MS medium supplemented with 1.5 mg L−1 2,4-D and 0.4 mg L−1 6-BA at room temperature under dark conditions and subcultured at 15-day intervals. The apple calli were used for genetic transformation. Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia seedlings were grown at 22 °C under long-day conditions (16/8 h light/dark). Arabidopsis seedlings were used for genetic transformation and functional identification.

Vector construction and plant transformation

To construct overexpression vectors, the full-length coding sequences of MdBT2 and MdABI5 were cloned into the pCXCN-Myc vector, and the full-length coding sequence MdZAT10 was cloned into the pRI-101 vector (with a GFP tag). To generate antisense suppression vectors (MdBT2-Anti, MdABI5-Anti, and MdZAT10-Anti), fragments of the MdBT2, MdABI5, and MdZAT10 sequences were cloned into the pRI-101 vector. MdBT2-GFP transgenic apple calli were obtained as described in our previous study38. To generate the proMdZAT10:GUS construct, the promoter fragment of MdZAT10 was inserted into the pCAMBIA1300-GUS vector, which was then transformed into apple calli. Transgenic apple seedlings, apple calli, and Arabidopsis seedlings were obtained according to previously described methods61,62. The transient transformation apple leaves were obtained according to a previously described method62. All the primers used for gene cloning are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

RNA extraction and gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from apple seedlings, apple calli, Arabidopsis seedlings, and treated seedlings using the RNAplant Plus kit (TIANGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed on a StepOnePlus instrument (Applied Biosystems) using UltraSYBR Mixture (Takara). All primers are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for each experiment.

MdZAT10-interacting protein screen

A LC/MS assay was performed with the MdZAT10-GFP protein to screen out MdZAT10-interacting proteins as previously described63. The MdZAT10-GFP protein was extracted from MdZAT10-overexpressing transgenic calli and purified using a Pierce Classic IP Kit (Thermo Fisher). The MdZAT10-GFP protein was incubated with total protein extracted from apple seedlings for 6 h. The mixed protein solutions were incubated with protein A/G agarose beads and anti-GFP antibody according to a standard co-immunoprecipitation protocol. Then, the resin was eluted, and the eluted proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE gels. Protein identification was carried out by LC-MS/MS (OE Biotech, Shanghai, China).

Yeast two-hybrid assay

To confirm the interactions between MdZAT10 and MdABI5, and MdBT2 and MdZAT10, the coding sequences of MdZAT10, MdABI5, and MdBT2 were cloned into the pGAD424 and pGBT9 vectors to form pGAD-MdZAT10, pGBD-MdABI5, and pGBD-MdBT2. Truncated MdZAT10 sequences (amino acids 1–207 and 191–270) were cloned into pGAD424. The truncated MdBT2 sequences were also cloned into pGBT937. We performed a Y2H assay as described previously64. The pGBD-MdABI5 and pGBD-MdBT2 plasmids were individually transformed with pGAD-MdZAT10 into yeast strain Y2H Gold (Clontech). Yeast transformants were grown on SD base/-Leu/-Trp medium and then transferred onto SD base/-Leu/-Trp/-His/-Ade medium for interactions.

Pull-down and BiFC assays

The full-length coding sequences of MdZAT10, MdBT2, and MdABI5 were cloned into the pET32a and pGEX4T-1 vectors to generate the recombinant constructs MdZAT10-pET32a, MdZAT10-pGEX 4T-1, MdABI5-pET32a, and MdBT2-pGEX 4T-1. The constructs were introduced into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3), after which the MdZAT10-His, MdZAT10-GST, MdABI5-His, and MdBT2-GST fusion proteins were generated by induction with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The eluted proteins were detected by western blotting with anti-GST and anti-His antibodies (Abmart, Shanghai, China).

The coding sequences of MdZAT10, MdBT2, and MdABI5 were cloned into the 35S::pSPYCE-cYFP and 35S::pSPYNE-nYFP vectors to generate MdZAT10-cYFP, MdBT2-nYFP, and MdABI5-nYFP. The recombinant constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 and then injected into N. benthamiana leaves. YFP fluorescence signals were detected using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss).

Analysis of leaf senescence phenotype

To examine the leaf senescence phenotype, detached leaves were placed on 3 mM MES buffer (pH 5.8) in the dark at 22 °C. To examine phytohormone-induced leaf senescence, detached leaves were floated on 3 mM MES buffer (pH 5.8) containing 100 μM MeJA at 22 °C and kept under dim light for the indicated time period.

Quantification of the chlorophyll content and Fv/Fm ratio

To measure the total chlorophyll concentration, total pigments were extracted from plant leaves with 95% (v/v) ethanol for 24 h. The absorbance at 649 and 665 nm was measured using an ultraviolet/visible spectrophotometer (SOPTOP UV2800S, Shanghai, China). To calculate the Fv/Fm ratios, leaves were analyzed with a closed chlorophyll fluorescence imaging system (Photon System Instruments, Brno, Czech Republic) according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described31.

Protein degradation and ubiquitination assays

For the in vitro protein degradation assay, total protein was extracted from wild-type and transgenic apple calli using degradation buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5 mM DTT, and 10 mM ATP). The protein extracts were incubated with MdZAT10-His at 22 °C and assessed by western blotting with an anti-His antibody (Abmart).

We performed an in vivo ubiquitination assay as described previously64. In brief, MdBT2-GFP transgenic calli was extracted using a PierceTM Classic IP Kit (Thermo Fisher), and the extracts were incubated with MdZAT10-His protein at 4 °C overnight. The in vivo ubiquitination of MdZAT10 was detected by western blotting with anti-His (Abmart) and anti-Ubi (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies.

Transient expression assay

To carry out the transient expression assay, the MdNYC1 and MdNYE1 promoter sequences were inserted into the pGreenII 0800-LUC vector. Full-length MdZAT10 and MdABI5 were cloned into the pGreen 62-SK vector. The recombinant plasmids were transformed into N. benthamiana leaves by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, and LUC/REN activity ratio was detected using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega)64.

GUS analysis

For GUS staining, transgenic plants were incubated in X-gluc buffer (1 mM X-Gluc, 0.5 mM ferricyanide, 0.5 mM ferrocyanide, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100) at 37 °C for 12 h. GUS activity was detected using a fluorescence spectrophotometer.

Statistical analyses

Each experiment in this study was repeated at least three times. The data were analyzed by t-test using GraphPad Prism 6.02 software, and asterisks denote significant differences (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Apple Genome (GDR): MdABI5 (LOC103430245), MdABI1 (MDP0000265371), MdABI2 (MD15G1054500), MdABI4 (MD01G1155400), MdBT1 (MDP0000151000), MdBT2 (MDP0000643281), MdBT3.1 (MDP0000296225), MdBT4 (MDP0000215415), MdNYE1, (MDP0000322543), MdNYC1 (MDP0000124013), MdAZF1 (MDP0000265345), MdZAT5 (MDP0000769354), MdZAT6 (MDP0000319225), MdZAT10 (MDP0000198015), MdZAT11 (MDP0000305944), MdZAT14 (MDP0000204390), MdZAT16 (MDP0000137826), and MdZAT18 (MDP0000768369).

Supplementary information

Revised - Supplementary materials-clean.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31772288) and Shandong Natural Science Major Basic Research Foundation (ZR2020ZD43).

Author contributions

J.A. proposed the project. K.Y. performed most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. X.S., D.W., and C.L. constructed the vectors. Y.L. and X.J. provided the plant materials and assay methodology. Y.H. and C.Y. discussed the article. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Yu-Jin Hao, Email: haoyujin@sdau.edu.cn.

Chun-Xiang You, Email: youchunxiang@126.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41438-021-00593-0.

References

- 1.Lim PO, Kim HJ, Nam HG. Leaf senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007;58:115–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Häffner E, Konietzki S, Diederichsen E. Keeping control: the role of senescence and development in plant pathogenesis and defense. Plants (Basel) 2015;4:449–488. doi: 10.3390/plants4030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivero RM, et al. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19631–19636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709453104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakuraba Y, et al. Phytochrome-interacting transcription factors PIF4 and PIF5 induce leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4636. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo HR, Kim HJ, Lim PO, Nam HG. Leaf senescence: systems and dynamics aspects. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019;70:347–376. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida S. Molecular regulation of leaf senescence. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003;6:79–84. doi: 10.1016/S1369526602000092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu XY, Kuai BK, Jia JZ, Jing HC. Regulation of leaf senescence and crop genetic improvement. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2012;54:936–952. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miersch I, Heise J, Zelmer I, Humbeck K. Differential degradation of the photosynthetic apparatus during leaf senescence in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant Biol. 2008;2:618–623. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-16632. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jibran R, Hunter DA, Dijkwel PP. Hormonal regulation of leaf senescence through integration of developmental and stress signals. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013;82:547–561. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, et al. Jasmonate regulates leaf senescence and tolerance to cold stress: crosstalk with other phytohormones. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:1361–1369. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Zhang F, Melotto M, Yao J, He SY. Jasmonate signaling and manipulation by pathogens and insects. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:1371–1385. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhuo MN, Sakuraba Y, Yanagisawa S. A jasmonate-activated MYC2-Dof2.1-MYC2 transcriptional loop promotes leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2020;32:242–262. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du MM, et al. MYC2 orchestrates a hierarchical transcriptional cascade that regulates jasmonate-mediated plant immunity in tomato. Plant Cell. 2017;29:1883–1906. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He Y, Fukushige H, Hildebrand DF, Gan S. Evidence supporting a role of jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:876–884. doi: 10.1104/pp.010843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thines B, et al. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCF(COI1) complex during jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2007;448:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature05960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chini A, et al. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2007;448:666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature06006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheard LB, et al. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature. 2010;468:400–405. doi: 10.1038/nature09430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qi TC, et al. Regulation of jasmonate-induced leaf senescence by antagonism between bHLH subgroup IIIe and IIId factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;27:1634–1649. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balazadeh S, Riaño-Pachón DM, Mueller-Roeber B. Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. (Stuttg.) 2008;10:63–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim J, Kim JH, Lyu JI, Woo HR, Lim PO. New insights into the regulation of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:787–799. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo K, et al. Cys2/His2 zinc-finger protein family of petunia: evolution and general mechanism of target-sequence recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:608–615. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.2.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi HT, et al. The cysteine2/histidine2-type transcription factor ZINC FINGER OF ARABIDOPSIS THALIANA6 modulates biotic and abiotic stress responses by activating salicylic acid-related genes and C-REPEAT-BINDING FACTOR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;165:1367–1379. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.242404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han G, et al. Arabidopsis ZINC FINGER PROTEIN1 acts downstream of GL2 to repress root hair initiation and elongation by directly suppressing bHLH genes. Plant Cell. 2020;32:206–225. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laity JH, Lee BM, Wright PE. Zinc finger proteins: new insights into structural and functional diversity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2001;11:39–46. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazan K. Negative regulation of defence and stress genes by EAR-motif-containing repressors. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakamoto H, et al. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:2734–2746. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Peng J, Wen X, Guo H. Gene network analysis and functional studies of senescence-associated genes reveal novel regulators of Arabidopsis leaf senescence. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2012;54:526–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2012.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu YR, et al. The transcription factor INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION1 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 and DELLA proteins to fine-tune abscisic acid signaling during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2019;31:1520–1538. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brocard IM, Lynch TJ, Finkelstein RR. Regulation and role of the Arabidopsis abscisic acid-insensitive 5 gene in abscisic acid, sugar, and stress response. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1533–1543. doi: 10.1104/pp.005793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su MY, et al. The LEA protein, ABR, is regulated by ABI5 and involved in dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Sci. 2016;247:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakuraba Y, et al. Multilayered regulation of membrane-bound ONAC054 is essential for abscisic acid-induced leaf senescence in rice. Plant Cell. 2020;32:630–649. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.An JP, et al. MdABI5 works with its interaction partners to regulate abscisic acid-mediated leaf senescence in apple. Plant J. 2021;105:1566–1581. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan Y, et al. Overexpression of MpCYS4, a phytocystatin gene from Malus prunifolia (Willd.) Borkh., delays natural and stress-induced leaf senescence in apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017;115:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang N, et al. Functional analysis of apple MhYTP1 and MhYTP2 genes in leaf senescence and fruit ripening. Sci. Hortic. 2017;221:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2017.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu DG, Sun CH, Zhang QY, Gu KD, Hao YJ. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor MdbHLH3 modulates leaf senescence in apple via the regulation of dehydratase-enolase-phosphatase complex 1. Hortic. Res. 2020;7:50. doi: 10.1038/s41438-020-0273-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.An JP, Wang XF, Zhang XW, You CX, Hao YJ. Apple BT2 protein negatively regulates jasmonic acid-triggered leaf senescence by modulating the stability of MYC2 and JAZ2. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44:216–233. doi: 10.1111/pce.13913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang XF, et al. The nitrate-responsive protein MdBT2 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by interacting with the MdMYB1 transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2018;178:890–906. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Q, et al. Ubiquitination-related MdBT scaffold proteins target a bHLH transcription factor for iron homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 2016;172:1973–1988. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masclaux C, Valadier MH, Brugière N, Morot-Gaudry JF, Hirel B. Characterization of the sink/source transition in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.) shoots in relation to nitrogen management and leaf senescence. Planta. 2000;211:510–518. doi: 10.1007/s004250000310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao C, et al. A rice NAC transcription factor promotes leaf senescence via ABA biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2017;174:1747–1763. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.00542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breeze E, et al. High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell. 2011;23:873–894. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.083345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mittler R, et al. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:6537–6542. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. The zinc finger network of plants. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:1150–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7473-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He F, et al. PeSTZ1, a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor from Populus euphratica, enhances freezing tolerance through modulation of ROS scavenging by directly regulating PeAPX2. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:2169–2183. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, Dang P, Liu L, He C. Cold acclimation by the CBF-COR pathway in a changing climate: lessons from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2019;38:511–519. doi: 10.1007/s00299-019-02376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rossel JB, et al. Systemic and intracellular responses to photooxidative stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:4091–4110. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.045898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan X, et al. A zinc finger transcriptional repressor confers pleiotropic effects on rice growth and drought tolerance by down-regulating stress-responsive genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:2129–2142. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seo PJ, Park JM, Kang SK, Kim SG, Park CM. An Arabidopsis senescence-associated protein SAG29 regulates cell viability under high salinity. Planta. 2011;233:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pruzinská A, et al. Chlorophyll breakdown in senescent Arabidopsis leaves. Characterization of chlorophyll catabolites and of chlorophyll catabolic enzymes involved in the degreening reaction. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:52–63. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Besseau S, Li J, Palva ET. WRKY54 and WRKY70 co-operate as negative regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:2667–2679. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kubo A. Expression of arabidopsis cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase gene in response to ozone or sulfur dioxide. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995;29:479–489. doi: 10.1007/BF00020979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duan J, Duan J, Zhang Z, Tong T. Irreversible cellular senescence induced by prolonged exposure to H2O2 involves DNA-damage-and-repair genes and telomere shortening. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:1407–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rogers H, Munné-Bosch S. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species and redox signaling during leaf and flower senescence: similar but different. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:1560–1568. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kan C, Zhang Y, Wang HL, Shen Y, Li Z. Transcription factor NAC075 delays leaf senescence by deterring reactive oxygen species accumulation in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:634040. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.634040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Procházková D, Wilhelmová N. Leaf senescence and activities of the antioxidant enzymes. Biol. Plant. 2007;51:401–406. doi: 10.1007/s10535-007-0088-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zander M, et al. Integrated multi-omics framework of the plant response to jasmonic acid. Nat. Plants. 2020;6:290-+. doi: 10.1038/s41477-020-0605-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pauwels L, et al. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1380–1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhu TT, Li LX, Feng L, Ren MZ. StABI5 involved in the regulation of chloroplast development and photosynthesis in potato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1068. doi: 10.3390/ijms21031068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou J, et al. The dominant negative ARM domain uncovers multiple functions of PUB13 in Arabidopsis immunity, flowering, and senescence. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:3353–3366. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gingerich DJ, et al. Cullins 3a and 3b assemble with members of the broad complex/tramtrack/bric-a-brac (BTB) protein family to form essential ubiquitin-protein ligases (E3s) in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18810–18821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang X, Henriques R, Lin SS, Niu QW, Chua NH. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip method. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:641–646. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.An JP, et al. MdbHLH93, an apple activator regulating leaf senescence, is regulated by ABA and MdBT2 in antagonistic ways. N. Phytol. 2019;222:735–751. doi: 10.1111/nph.15628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.An JP, et al. MdWRKY40 promotes wounding-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in association with MdMYB1 and undergoes MdBT2-mediated degradation. N. Phytol. 2019;224:380–395. doi: 10.1111/nph.16008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.An JP, et al. Apple bZIP transcription factor MdbZIP44 regulates abscisic acid-promoted anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:2678–2692. doi: 10.1111/pce.13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Revised - Supplementary materials-clean.