Abstract

A major mitochondrial enzyme for protecting cells from acetaldehyde toxicity is aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2). The correlation between ALDH2 dysfunction and tumorigenesis/growth/metastasis has been widely reported. Either low or high ALDH2 expression contributes to tumor progression and varies among different tumor types. Furthermore, the ALDH2∗2 polymorphism (rs671) is the most common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in Asia. Epidemiological studies associate ALDH2∗2 with tumorigenesis and progression. This study summarizes the essential functions and potential ALDH2 mechanisms in the occurrence, progression, and treatment of tumors in various types of cancer. Our study indicates that ALDH2 is a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy.

KEY WORDS: ALDH2, Polymorphism, Cancer, Tumorigenesis, Progression, Cancer therapy, Acetaldehyde, Metastasis

Abbreviations: 4-HNE, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; ALDH2, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; BCa, bladder cancer; ccRCC, clear-cell renal cell carcinomas; COUP-TF, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor; CRC, colorectal cancer; CSCs, cancer stem cells; DFS, disease-free survival; EC, esophageal cancer; FA, Fanconi anemia; FANCD2, Fanconi anemia protein; GCA, gastric cancer; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HNC, head and neck cancer; HNF-4, hepatocyte nuclear factor 4; HR, homologous recombination; LCSCs, liver cancer stem cells; MDA, malondialdehyde; MDR, multi-drug resistance; MN, micronuclei; NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NCEs, normochromic erythrocytes; NeG, 1,N2-etheno-dGuo; NER, nucleotide excision repair pathway; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; NHEJ, non-homologous end-joining; NRF2, nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2)-related factor 2; NRRE, nuclear receptor response element; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung; OPC, oropharyngeal cancer; OS, overall survival; OvCa, ovarian cancer; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PC, pancreatic cancer; PdG, N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine; REV1, Y-family DNA polymerase; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; TGF-β, transforming growth factor β; VHL, von Hippel-Lindau; εPKC, epsilon protein kinase C

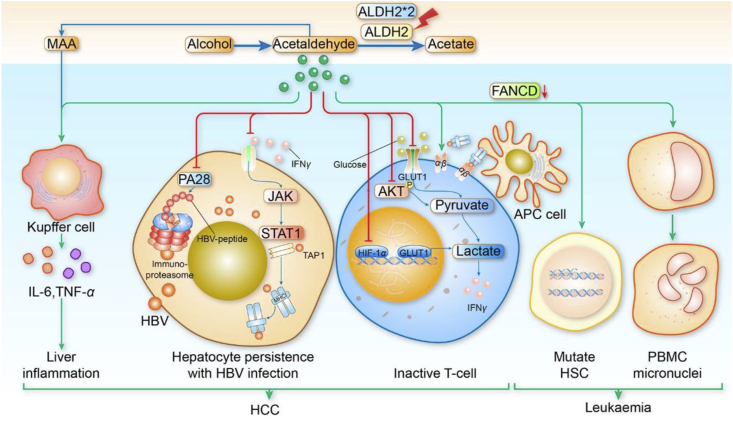

Graphical abstract

ALDH2 dysfunction contributes to the occurrence and development of cancer. A better understanding of the relationship between ALDH2 and cancer can provide a new strategies of treating cancer patients by targeting ALDH2.

1. Introduction

ALDH2 belongs to the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase family, comprising of 517 amino acids and four identical subunits that form an autotetraploid to stabilize protein structure. Each subunit consists of three domain structures, including the catalytic domain, the structure of the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), and the oligomerization domain. Therefore, ALDH2 is a significant participant in the oxidation–reduction reaction of ethanol and endogenous aldehydic products which is set free from lipid peroxidation. The inactive ALDH2 rs671 or low ALDH2 expression causes the accumulation of aldehydic products such as acetaldehyde, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), and malondialdehyde (MDA), which are associated with high morbidity of cancer1,2. This study reveals that not only is ALDH2 involved in aldehyde metabolism but also plays a key role in the growth of tumors. ALDH2 is mainly located in the mitochondria and cytoplasm. However, ALDH2 was found to contain a substantial amount of exosomes in normal human urine3. This is an indication that ALDH2 functions could exceed the ones discussed in this study. ALDH2∗2 heterozygotes or homozygotes with ALDH2 deficiency are associated with a high risk of upper digestive tract cancers among the drinking and smoking populations4. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients with ALDH2 high expression are associated with a good prognosis5. Intriguingly, ALDH2 is a cancer stem cells (CSCs) biomarker and is associated with proliferation, metastasis, and multidrug resistance (MDR) to cancer cell chemotherapy drugs6. The role of ALDH2 in tumor tumorigenesis and progression remains unclear, as well as the effect of ALDH2 on the efficacy of tumor therapies. This study outlines the possible role of ALDH2 and its underlying mechanisms in tumorigenesis, tumor progression and cancer treatment in various types of cancer. We present ALDH2 as a potential therapeutic candidate for cancer.

2. The relationship between ALDH2 and cancer

2.1. ALDH2 polymorphisms is related to cancer occurrence and development

Substitution of glutamic acid by lysine at 487 codons (Glu487Lys), also known as rs671 causes the variant ALDH2∗2 allele in exon 12 that affects estimated 560 million East Asians7. Heterozygote individual enzyme activity (ALDH2∗1/∗2) was significantly lower (50%) than the wild type, while homozygous mutation enzyme activity (ALDH2∗2/∗2) was between 1% and 4% of the ALDH2∗1/∗1 genotype8, 9, 10. Several studies have analyzed the relationship between ALDH2 polymorphism and alcohol-related cancers, including head and neck cancer (HNC), esophageal cancer (EC), HCC, colorectal cancer (CRC), gastric cancer (GCA), and breast cancer. Some meta-analyses and major articles reported an increased risk of HNC, EC, HCC, and GCA in patients with the variant ALDH2∗2 allele11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16. The occurrence of HNC, ESCC, pancreatic cancer (PC), and bladder cancer (BCa) can result from the combination of ADH1B polymorphisms, the slow/non-functional ALDH2 genotypes, and alcohol17, 18, 19, 20, 21. In the Japanese population, individuals with a combination of ALDH2∗1/∗2 and ADH2∗2/∗2, little or moderate alcohol consumers, and patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, are associated with the highest risk of HCC22,23.

Avincsal et al.24 reported that, compared with other patients with hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), alcoholics with the ALDH2∗2 allele were associated with worse overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS). In Japanese populations, heterozygous ALDH2 with poor outcomes could be a potential prognostic factor for oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) patients with P16-negative25. Analysis of the relationship between the ALDH2 rs671 and HCC postoperative outcome showed that the ALDH2∗1/∗1 genotype had a negative outcome after surgery, whereas HCC patients who carried ALDH2∗2 variants had a better postoperative prognosis26. In a recent study, ALDH2 rs671 was associated with a high risk for HCC occurrence in cirrhotic patients with HBV who were heavy drinkers. It was also observed that ALDH2 deficiency in the mouse models of ALDH2 knockout and ALDH2∗1/∗2 knock-in mutant mice aggravated alcohol-associated HCC incidence27.

ALDH2∗2 variants also had an indirect significant protective effect on the digestive tract cancers for moderate alcohol consumers11,28. Liu et al.29 found that ALDH2 rs671 is significantly associated with low risk of HCC (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.61–0.82). Individuals with ALDH2∗2 variants were less likely to alcohol addicts. A meta-analysis analyzed ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism and CRC risk among 2909 CRC patients and 4903 controls and found ALDH2 polymorphism to be a protective factor of CRC30. A recent study showed that there is an indirect relationship between ALDH2 polymorphism and the risk of CRC due to the polymorphism. This polymorphism is thought to reduce the drinking rate11. Another study from Japan reported that compared with the ALDH2∗1/∗1 genotype, only the homozygous ALDH2∗2/∗2 genotype was associated with a reduced risk of CRC (OR = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.33–0.93)28. In addition, ALDH2 rs671 is a protective factor in ovarian cancer (OvCa), but it is not related to alcohol drinking31.

The distribution of polymorphisms in ALDH2 among different ethnic populations is different, with an exception in ALDH2 rs671 polymorphism in the Asian population. In the Central European drinking populations, mutation at ALDH2 nucleotide position 248, as well as the ALDH2 +82A > G and ALDH2 –261C > T polymorphisms, are associated with the risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers32. In a European prospective investigation, individuals with both ADH1 (rs1230025) and ALDH2 (rs16941667) variants are likely to develop GCA33.

There is also a lot of evidence that ALDH2 variants are high-risk factors of ESCC patients who smoke and drink4,34,35. Smokers with ALDH2∗2/∗2 genotype are susceptible to lung cancer36,37. In conclusion, the variant ALDH2∗2 allele is a genatic risk of smoke and alcohol-induced neoplasm (Table 14, 5, 6,9,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47). These findings suggest that individuals with ALDH2∗2 allele should quit drinking and smoking.

Table 1.

Selected studies showing the relationship of ALDH2 with tumorigenesis and progression.

| Tumor type | ALDH2 status | Tumorigenesis | Cancer progression | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | Overexpression | – | Unfavorable | 6 |

| Esophageal cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | 4,12,20,34,35,38,39 |

| Head and neck cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | 11,18,19,24,25,32,40–43 |

| Colorectal cancer | Mutation | Favorable | – | 11,28,30 |

| Colorectal cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | – | 16 |

| Gastric cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | 13–15,33 |

| Hepatocellular cancer | Downexpression | – | Unfavorable | 5,9,44 |

| Hepatocellular cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | 22,23,27 |

| Hepatocellular cancer | Mutation | Favorable | Favorable | 26,29 |

| Bladder cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | Unfavorable | 17,45 |

| Pancreatic cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | – | 21 |

| Ovarian cancer | Mutation | Favorable | – | 31 |

| Lung cancer | Mutation | Unfavorable | – | 36,37 |

| Lung cancer | Activation | – | Favorable | 46 |

| Liver cancer stem cells | Overexpression | – | Unfavorable | 47 |

–Not applicable.

2.2. Tumor progression associated with ALDH2's alarming expression

Not only are the ALDH2 variants associated with alcohol-mediated cancer, but ALDH2 expression has also been identified as a possible prognostic marker for several types of cancer. Based on our findings, ALDH2 has numerous effects on tumors. Transcriptional suppression of ADH1A and ALDH2 expression reduced survival and aggravated HCC44. To study the lung and liver cancer cell lines, some scientists have used both biochemical and bioinformatics techniques. They found that ALDH2 expression was negatively correlated with DNA base excision repair protein (XRCC1) expression, an indication that low ALDH2 expression was responsible for poor overall survival48. Consistent with previous studies, downregulated ALDH2 of liver cancer cells caused migration and invasion5. One of the mechanisms of ALDH2-modulated HCC progression is that ALDH2 down-expression leads to cell redox status by acetaldehyde accumulation, which then increases the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway in HCC5. In addition, a recent study has shown that ALDH2 deficiency induces HCC progression by transmitting extracellular vesicles enriched with oxidized mtDNA from weakened hepatocytes into HCC cells27. ALDH2 can therefore be a useful biomarker and target for assessing the prognosis and developing potential HCC therapeutic strategies.

Notably, ALDHs are hallmarks of CSCs which are characterized by cell self-renewal, metastasis, and multidrug resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Some studies showed that ALDH2 is not only an enzyme involved in aldehyde detoxification but also a cancer stem marker in tumors. Chen et al.47 reported that ALDH2 promots the expression of cancer stem biomarkers (e.g., NANOG, OCT4, AND SOX2), leading to the proliferation, migration, and invasion of liver CSCs. ARRB2 (β-arrestin-2) decreased the growth of bladder cancer cells by stem cell marker (CD44, ALDH2, and BMI-1) downregulation6. Paradoxically, enhancing the activity of ALDH2 by agonist Alda-1 inhibited the cancer stemness, proliferation, and migration to minimize DNA damage in lung adenocarcinoma cells46. However, further research is needed to determine whether ALDH2 is also a cancer stem marker.

3. The regulation of ALDH2

The ALDH2 regulation is summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Transcriptional and post-translational level control of ALDH2. PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathways are involved in transcriptional control of ALDH2. HDAC1 activated by PI3K/AKT/mTOR/pathway and SET has a role in inhibiting the acetylation of nucleosomes for transcriptional suppression. The activated transcription factors of ALDH2 include NRF2, VHL, HNF-4, RXRs, and FOXM1, which interact with the FP330-3′ element of the promoter region to promote the expression of ALDH2. COUP-TFI and ARP-1 bind to the FP330-5′ element repress the promoter activity of ALDH2. JNK, AMPK, and εPKC can phosphorylate the specific sites of ALDH2 protein for repressing or enhancing its activity. SIRT3 inhibits the enzyme activity of ALDH2 by decreasing its acetylation level. RTKs, receptor tyrosine kinase.

3.1. Transcriptional control of ALDH2

The major method involved in ALDH2 expression is transcriptional regulation. The crucial role of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (HNF-4) in the management of ALDH2 has also been implied in COS-1 and hepatoma cells. Besides, the binding site for HNF-4 has been identified at the ALDH2 promoter domain, which is about 300 bp upstream region from the translation initiation site49. Some researchers, however, claim that the nuclear receptor response element (NRRE) is more complicated. The promoter region (at –300–360 bp) of ALDH2 could bind the superfamily of nuclear receptors, comprising the FP330-5 and FP330-3′ elements. The ALDH2 FP330-3′ site serves as a positive transcriptional element that can be activated by retinoid X receptors (RXRs) and HNF-4. However, the present of the family chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor (COUP-TF) and apolipoprotein regulatory protein-1 (ARP-1) can repress the promoter activity of ALDH2 that is activated by RXRs and HNF-4 through binding to the FP330-5′ site50. von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) binds to the HNF-4 alpha activating promoter to activate ALDH2 expression, causing the resistance of anthracyclines to clear-cell renal cell carcinomas (ccRCC)51. Chen et al.47 reported that transcription factor FOXM1 binds to the ALDH2 promoter region to promote its expression thereby affecting the expression of NANOG, OCT4, AND SOX2 in LCSCs. Another in vitro study showed the ability of vitamin D in mitigating alcoholic liver disease. The mechanism involves vitamin D treatment inducing nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2)-related factor 2 (NRF2) expression that results in the upregulation of ALDH2 expression to facilitate alcohol metabolism52. ALDH2 then mediates ERK phosphorylation through MEK/ERK pathway to increases transcriptional NRF2 through AP-1/TRE52. These changes have also been observed in human hepatoma cells53. Hyperactivation or MEK/ERK pathway mutations are part of the mechanisms that promote cancer development. It is therefore important to establish the relationships between the MEK/ERK activated pathway and ALDH2 in tumors.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are essential epigenetic factors linked to the regulation of non-histone targets. The mTOR signaling in the upstream of HDAC1 is a key mechanism in oncogenesis promoting the survival and proliferation of cancer cell. mTOR/HDAC1 is involved in the regulation of ALDH2 promoter deacetylation, thus, leading to the transcriptional suppression of the ALDH2 gene in HCC44. Furthermore, the SET protein (template-activating factor-I b/inhibitor-2 of protein phosphatase-2A) has a role in inhibition of nucleosome acetylation54. SET binds specifically to the ALDH2 promoter via the SET NAP domain that targets ALDH2's N-terminal histone tails to repress its expression55.

3.2. Post-transcriptional control of ALDH2

Post-transcriptional regulatory factors form RNA expression are microRNAs (miRNAs), whose aberrant expression is associated with the development of cancer56. MiR-34a is a critical suppressor of tumor progression and metastasis in multiple cancers including HCC57, CRC58, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)59,60, and pancreatic cancer61. By binding to the 3′UTR of ALDH2, miR-34a downregulates ALDH2 protein and develops its anti-tumor effects by halting the G1 phase thus suppressing migration and invasion of HCC cell62. More research should focus on establishing the mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation of ALDH2.

3.3. Post-translational regulation of ALDH2

Epigenetic modification modulates ALDH2 as well. Pyrosequencing-based quantitative analysis was used to detect DNA methylation in GC samples and ALDH2 exhibited significant hypomethylation in gastric tumors63. ALDH2 is a target of lysine (Lys) acetylation, and the hyper-acetylation and deacetylation of ALDH2 protein lysine residues alter its biological functions. The major mitochondrial deacetylase sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) plays a crucial role in modulating cellular mitochondrial oxidation reactions. SIRT3 decreased the rate of acetylation of ALDH2 by deacetylation of Lys369 (K369)64 or Lys377 (K377)65. This influenced the enzyme activity to inhibit the normal binding site of the NAD+ cofactor without affecting the expression of the ALDH2 protein66. By modulating cellular metabolism and oxidative stress, deregulated SIRT3 can cause cancer progression67. Alcohol influences the activity and/or protein level of SIRT3 in various alcohol-related diseases by increasing ALDH2 activity68,69. More researches are needed to ascertain if this mechanism can cause tumorigenesis.

Phosphorylation is an essential post-translational modification of changing protein construction, function, and activity. The activated JNK translocated to mitochondria for phosphorylation the serine 463 (S463) of ALDH2 after carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) exposure, and attenuated the activity of ALDH2 in rats70. Besides, in low-density lipid protein receptor (LDLR) knockout mice, the threonine 356 (T356) of ALDH2 phosphorylated by AMPK could shuttle from cytoplasm into the nuclear thereby suppressing ATP6V0E2 transcription and impairing lysosomal function71. Epsilon protein kinase C (εPKC), an oncogenic gene of multiple types of cancer, increases the activity of ALDH2 enzymes by phosphorylation of three ALDH2 sites, including threonine 185 (T185), serine 279 (S279) and threonine 412 (T412)72.

3.4. ALDH2 rs671 variants have a dominant-negative effect on protein turnover

ALDH2 is a tetrameric enzyme, the encode subunit (ALDH2K) of ALDH2∗2 gene is lower activity compared with ALDH2∗1 transforming the wild-type subunit (ALDH2E)73. The ALDH2E protein (half-life >22 h) is more stable than the ALDH2K protein (half-life = 14 h). In addition, the ALDH2K has a dominant-negative effect on enzyme regeneration73. The stabilization of ALDH2 in various genotypes is ALDH2∗1/∗1, ALDH2∗1/∗2, and ALDH2∗2/∗273, in descending order. Similarly, Jin et al.74 suggested that the ALDH2 rs671 variants reduce the level of ALDH2 protein that promotes murine hepatocarcinogenesis in liver cells. However, more research should be done to establish the specific mechanisms of ALDH2 mutant protein decreasing the stability of ALDH2 protein.

4. The related mechanisms of ALDH2 mediated cancers

The related mechanisms of ALDH2 mediated cancers are summarized in graphical abstract.

4.1. ALDH2 and endogenous aldehydes metabolism

ALDH2 is an essential cellular detoxification enzyme for endogenous aldehydes formed in cells by oxidative metabolism. Oxidative reactions promote cancer development due to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation. ALDH2 influences the removal of endogenous aldehydes generated by the ROS-mediated peroxidation such as 4-HNE and MDA. MDA levels were found to be significantly higher levels in CRC patients than the healthy controls75. CRC production is associated with increased serum MDA levels76. Sawczuk et al.77 stated that MDA also plays a pivotal role in non-invasive diagnosis of BRCA1 mutated breast cancer patients with elevated levels of lipid oxidation products in saliva. In addition, 4-HNE has been reported to be both an endogenous carcinogen and an anti-cancer product. 4-HNE exhibits antitumor effects by regulating oncogenic signal pathways and oncogenes downregulation78. For example, 4-HNE inhibited nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway and its anti-apoptotic target BCL-2 leading to cell apoptosis79. 4-HNE contributes to colorectal carcinogenesis by activation of the oncogenic transcription factor AP-1 such as c-Jun and NRF280. 4-HNE has also been identified as a major electrophile that binds to DNA and forms a 4-HNE-guanine adduct that induces a high frequency of codon 249 mutation in the P53 gene81.

4.2. ALDH2 and the metabolism of exogenous acetaldehyde

ALDH2 plays a key role in acetaldehyde metabolism, which is an intermediate metabolite of ethanol. Individuals with ALDH2 rs671 variants are unable to metabolize exogenous and endogenous aldehydes, leading to the accumulation of acetaldehyde thus forming DNA adducts. The acetaldehyde-derived DNA adducts include N2-ethylidene-detoxication, R- and S-a–CH3–g-OH-1,N2-propano-2′-deoxyguanosine (PdG), and 1,N2-etheno-dGuo (NeG). Such adducts cause damage to DNA, including DNA mutations, DNA interstrand-cross-links, DNA single-strand breaks, and DNA double-strand breaks82. Acetaldehyde causes mutations of DNA by changing GG to TT tandem substitutions in human nucleotide excision repair (NER) deficient cells, and such changes are associated with alcohol-related tumors83. Yakawa et al.84 treated Aldh2-knockout mice with ethanol and found that the level of NeG was much higher in the esophagus of Aldh2-knockout mice compared to wild-type mice. Matsuda et al.85 tested 44 blood DNA samples of Japanese alcoholics and detected that the levels of both PdG and NeG adducts were significantly higher in patients with the ALDH2∗1/∗2 genotype compared to alcoholics with the ALDH2∗1/∗1 genotype. All these studies show that acetaldehyde indirectly affects genome stability by creating DNA adducts.

Some studies have shown that human cells with acetaldehyde increase the number of DNA-protein crosslinks (DPCs), leading to genetic and epigenetic instability. The adducts affect genomic stability by slowing the activity of O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) which is a DNA repair protein by protecting DNA from alkylationc86 and DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) which is a regulator of the epigenetic gene by methylation at the C5 of cytosine87. In addition, another potential mechanism that is critical in maintaining genetic and epigenetic stability is the histones modifications. Chen et al.88 showed that acetaldehyde incubation reduces the level of acetylation for cytosolic histones H3 and H4 N-terminal tails in BEAS-2B cells due to the formation of histone adducts. Acetaldehyde can also form histones H1 adducts and impair its DNA binding functions89. Acetaldehyde decreases methylation and acetylation levels thus inducing DPCs to influence the genome function. Further studies are required on DPCs mechanisms and the types of carcinogens they regulate.

4.3. ALDH2 deficiency and DNA damage repair

Cells need to activate and exploit DNA damage repair to protect against acetaldehyde-induced DNA crosslink since ALDH2 deficiency leads to detoxification of acetaldehyde-impaired (Fig. 2). It has been shown that the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway participates in DNA damage repair. Langevin et al.90 showed that Fanconi anemia protein (FANCD2) deficient cells were hypersensitive to acetaldehyde exposure; such a phenomenon was also observed in Fancd2−/− mice. They further found that the addition of acetaldehyde to cell lines stimulated FANCD2 monoubiquitination, which was necessary to remove DNA interstrand crosslinks. Monoubiquitination of FANCD2 and FANCI form FANCD2–FANCI heterodimers that bind onto DNA and recruit other DNA repair factors to the DNA interstrand crosslinks91. As a result, mice with Aldh2–/–Fancd2−/− double-mutant can develop acute leukemia90. Moreover, β2-spectrin (β2SP/Sptbn1), a transcriptional cofactor of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), plays a key role in the repair of alcohol-induced DNA damage by activation of FANCD2 in liver cells92. When the TGF-β/β2SP signaling pathway is suppressed, the FA DNA repair pathway could be defective as well. After the absence of the FA DNA repair pathway, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and alternative non-homologous end-joining (Alt-NHEJ) are required to determine the acetaldehyde-induced DNA damage in the mouse hematopoietic system after the failure of the FA DNA repair pathway93. The role of the FA pathway cannot be substituted since the NHEJ pathway that induces subsequent mutagenic repair and alternative end-joining. Recent studies have showed that the micronuclei of normochromic erythrocytes (NCEs), one marker of genetic instability, is much more in Aldh2−/− Fancd2−/− mice (9.5-fold) compared with the wild-type controls. The increase in Aldh2−/− mice was 2.9-fold while that of Fancd2−/− mice was 1.9-fold93. Embryo dysplasia, hematopoietic stem cell dysfunction, and cancer predisposition are aggravated in FA patients diagnosed with ALDH2 deficiency90,93.

Figure 2.

The mechanism of DNA damage repair for ALDH2 deficiency induced DNA damage. The ALDH2 deficiency can lead to acetaldehyde-induced DNA interstrand crosslinks, DNA double-strand breaks (DSB), and tandem mutation, which requires the Fanconi anemia pathway (FA), homologous recombination pathway (HR), Y-family DNA polymerase mediated pathway, classical non-homologous end-joining pathway (NHEJ), alternative non-homologous end-joining repair pathway (Alt-NHEJ), and NER pathway for DNA damage repair. The DNA interstrand crosslinks repair mechanisms involve FA and REV1 pathway. The difference between FA and REV1 pathways is that FA pathway needs to incise for unhooking the crosslink, which leads to DNA strand breaks or abasic sites. However, REV1 repair pathway can operate without excision and promote genome stability. The DSBs repair pathways of acetaldehyde-induced include HR, NHEJ, and Alt-NHEJ. When presents BRCA1/2 mutation or FA pathway inactivation, NHEJ, and Alt-NHEJ pathway are required to repair DSBs and this leads to mutagenesis. NER pathway mediates acetaldehyde-induced tandem mutation repair.

Another way to maintain genome integrity is via homologous recombination (HR) repair pathway (Fig. 2). HR family members like BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51 have been associated with the FA pathway for DNA crosslink repair94,95. Tacconi et al.95 found that acetaldehyde decreases the growth of BRCA1/2-deficient tumors in vivo and using disulfiram, an ALDH2 inhibitor used for clinical treatment of alcoholism also significantly destroys BRCA1/2-deficient cells. Besides, enhanced monoubiquitination of FANCD2 and Ser1524 phosphorylation of BRCA1, the acetaldehyde-induced DNA adducts triggers the FA and BRCA pathways94. BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant carriers tend to develop breast and ovarian cancer96. In addition to their roles in other cancers, BRCA1 mutation is associated with colorectal cancer97. BRCA2 carriers’ mutations are likely to cause prostate cancer98,99. More researches are needed to establish whether individuals with both BRCA1/2 and ALDH2 mutations are more likely to develop cancer.

Recent studies have shown a new way of restoring crosslinks caused by acetaldehyde100. The scholars reacted acetaldehyde with guanine to generate PdG which was an acetaldehyde-crosslinked DNA substrate. Two different pathways that repaired these lesions were found. The first was the FA pathway, which determined the DNA interstrand crosslinks caused by acetaldehyde through DNA crosslinks excision100. FA pathway increased the frequency of mutations and alerted the mutational spectrum100. The second was the Y-family DNA polymerase (REV1) mediated pathway, which was faster with fewer mutations compared with the FA pathway, and involved cutting within the crosslink itself100.

In addition, acetaldehyde can also react with adjacent guanine, cytosine and adenine, to induce intra-strand crosslinks of DNA (Fig. 2). Matsuda et al.83 found that acetaldehyde forms intra-strand crosslinks with adjacent guanine bases in human cells thus causing GG to TT tandem mutations. As a result, XP-A protein, a NER pathway related protein, recognizes and binds to the acetaldehyde-mediated DNA damage for repair83.

4.4. ALDH2 and autophagy

Autophagy, a lysosomal degradation system that degrades intracellular components through the lysosome, is used to maintain cellular homeostasis in many human diseases, especially cancer. ALDH2 deficiency induces the accumulation of acetaldehyde and oxidative stress after ethanol treatment. Activated autophagy can serve as a protection against alcohol-related esophageal carcinogenesis at this point94,101. However, Guo et al.102 showed that ethanol and acetaldehyde suppress autophagy in VA-13 cells, although such changes can be reversed by ALDH2. ALDH2 deficiency impairs the beclin-1-dependent autophagy pathway to result in cardiac dysfunction in cardiometabolic diseases103. Recent studies have shown that AMPK phosphorylated ALDH2 shuttles to the nucleus to inhibit the lysosomal proton pump protein transcription of ATP6V0E2. This leads to increased foam cells in ALDH2 variant carriers for the attenuated autophagy pathway71. To enhance autophagy, ALDH2 enhancement activation is necessary. This is done by attenuating the carbonylation of SIRT1 and stimulating SIRT1 activity, thus improving the deacetylation of nuclear LC3, resulting in increased interaction between LC3 and ATG7 in the cytoplasm104. This study shows that in some human diseases, ALDH2 is linked to autophagy regulation, but it is unclear if this association may be the case in cancer. We speculate that autophagy is one of the mechanisms that ALDH2 uses to regulate tumor occurrence and development.

4.5. ALDH2 and immune system dysfunction

Seldom studies mention the relationship between ALDH2 and inflammation. Next, we consider describing indirect effects of ALDH2 on the immunity response. ALDH2 regulates the inflammatory response caused by acetaldehyde. Ganesan et al.105 found that that acetaldehyde decreased the expression of hepatocyte cell surface HBV peptide-MHC class I complexes by decreasing the expression of PA28 and immune proteasome subunits and impairing the signaling pathway of JAK/STAT1/IFNγ. This inhibited CTL activation, leading to persistent HBV infection. In Aldh2−/− mice with acetaldehyde exposure, the TCR mutant frequency was much higher compared to Aldh2+/+ mice after oral administration106. Aldh2 knockout mice fed with chronic ethanol might lead to acetaldehyde accumulation and thereby inhibit T cells activation by suppressing the AKT phosphorylation, the mRNAs expression of glucose transporter 1 (Glut1) and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (Hif-1α), both of them mediate aerobic glycolysis107. In addition, in Aldh2−/− Fancd2−/− mice, deletions and rearrangements of hematopoietic stem cell by alcohol and endogenous aldehydes resulting from DNA damage were observed93, which could destroy the standard immune system. ALDH2 deficient alcohol consumers have an increased frequency of micronuclei108,109, leading to another lymphocyte chromatid exchanges110. Besides, acetaldehyde can combine with MDA generated by lipid peroxidation of membranes as MAA which modifies liver cytosols as the immunogen can contribute to autoimmune hepatitis in patients who take alcohol111. MAA adducts modulated immune response has also been associated with the pathogenesis of liver injury with alcohol exposure112,113. MDA adducts promote peripheral blood mononuclear cell T-cell proliferation in patients with ALD. This stimulates cellular immune responses that result into advanced ALD114. Therefore, ALDH2 indirectly regulates the immune system due to its role in aldehydes metabolism and acetaldehyde adducts. Our previous research showed that Aldh2 downregulation increases CD3+ and CD8+ T lymphocyte tumor infiltration, and significantly suppresses tumor growth and progression in our murine CRC model (unpublished data). The ALDH2-mediated immune system dysfunction could be one of the mechanisms leading to cancer (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

ALDH2 deficiency is related to immune dysfunction and causes HCC and leukemia. The ALDH2 deficiency causes acetaldehyde accumulation which induces liver inflammation, HBV infection persistence, T-cell inactivation, resulting to HCC occurrence. Acetaldehyde accumulation mediates HSC mutation and PBMC micronuclei, and these changes can lead to leukemia.

5. ALDH2 and cancer therapy

5.1. Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a significant cancer treatment method. However, MDR is still a problem in chemotherapy. Gemcitabine is a chemotherapeutic antimetabolic agent for non-small-cell lung (NSCLC), gastrointestinal and genitourinary cancer ALDH2 is a cancer stem cell marker for bladder cancer as the downregulation of ALDH2 can make bladder cancer cells gentamicin-sensitive, both in vitro and in vivo6. Mitoxantrone (MTX) is an anti-metabolic drug used to treat many types of cancer, including breast cancer, leukemia, lymphomas, etc. MTX toxicity is associated with ALDH2 expression, particularly with ALDH2 variants115.

While microtubule inhibitors induce drug resistance acquisition in cancer therapy, Wang et al.116 found that ALDH2 silently increases the cytotoxicity of A549/Taxol and KB/VCR cells to Taxol or vincristine (VCR), respectively, by reducing the effects of cancer stem cells. Disulfiram (DSF), a small molecule-based drug used for the treatment of alcohol addiction targeting ALDH2, irreversibly inhibits the activity of ALDH2's catalytic Cys302 through its metabolic agents, such as S-methyl-N,N-diethyldithiocarbamate (DETC) and S-methyl-N,N-diethyldithiocarbamate (Me-DDTC) that are converted by hepatic thiol methyltransferases117. DSF attenuates ALDH2 activity in vivo but not in vitro. DSF induces apoptosis of multiple cancer cells when it reacts with copper ions to form copper diethyldithiocarbamate (Cu(DDC)2), a major active ingredient116. Skrott et al.118,119 suggested that disulfiram kills cancer cells by suppressing P97/NPL4 that is essential for the turnover of proteins involved in stress-response pathways, rather than inhibiting ALDH activity. In addition, DSF cannot specifically inhibit the activity of ALDH2 without effecting other ALDH isozymes like ALDH1 which is the marker of CSCs in many cancers. The main mechanisms of DSF reversing microtubule inhibitor resistance in targeting ALDH2 need more research. Many clinical trials have considered incorporating the use of DSF with chemotherapy for cancer treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical trials of disulfiram combined chemotherapy.

| Tumor type | Phase | Treatment | Clinicaltrials.gov identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | II | Disulfiram, vinorelbine Cisplatin Copper |

NCT04265274 |

| Pancreatic cancer | II | Nab-paclitaxel/Gemcitabine/FOLFIRINOX + Disulfiram/copper |

NCT03714555 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | II | Chemotherapy (cisplatin, novelbine) +/− Disulfiram | NCT00312819 |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | I | Gemcitabine hydrochloride, Disulfiram |

NCT02671890 |

VHL-deficient ccRCC cells present enhanced sensitivity to anthracyclines, and ALDH2 is transcriptionally downregulated by VHL deficiency, which then helps to mitigate anthracycline resistance in ccRCC cells51. The main toxic side effect of anthracycline treatment in cancer patients is cardiotoxicity. Doxorubicin is one of the anthracyclines that affects cardiac geometry and functions by impairing mitochondrial integrity and inducing cardiac functional defect. However, ALDH2 overexpression or the ALDH2 agonist Alda-1 can relieve these effects, which mediated TRPV1-related mitochondrial integrity protection pathway120. Sun et al.121 reported that upregulation of 4-HNE and PI3K/AKT mediated autophagy is another mechanism of doxorubicin-induced cardiac defect. However, ALDH2 up-regulation or Alda-1-offered protective action can reverse these effects121.

ALDH2 is associated with the detoxification of reactive aldehydes, including 4-HNE, MDA, and acrolein, generated from ROS-mediated lipid peroxidation. Cisplatin treatment produces a large amount of ROS. Some scholars found that mice with an ALDH2∗2 variant were sensitive to cisplatin for increasing ROS levels122. Moreover, cells with SET overexpression (HEK293/SET) are more likely to be destroyed by cisplatin compared with HEK293 cells, which is partly caused by low ALDH2 expression and high DNA damage response55.

5.2. Molecular targeted treatment

Molecular targeted inhibitors that block the specific molecules have been a breakthrough in cancer treatment. Trastuzumab/pertuzumab antibodies have been approved for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive breast and gastric cancer. Komarova et al.123 reported that trastuzumab and pertuzumab plant biosimilars cooperated with DSF are more effective in killing breast cancer cells compared with pertuzumab plant biosimilars treatment alone. In another study, DSF inhibited the growth of BRCA1/2-deficient patient-derived tumor xenograft cells (PDTCs) that was resisted to treatment of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors therapy95. More research should focus on establishing whether targeting ALDH2 is the main mechanism used by DSF in enhancing molecular targeted therapy.

5.3. Immunotherapy

There are several approaches to cancer immunotherapy, including active vaccination, chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, and immune checkpoint blockade. Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin is an effective treatment in urothelial precancerous lesions. The ALDH2 expression level was lower in the Bacillus Calmette-Guerin-treated group compared with the non-treated group124. Some researchers used proteomic profiling of clinical melanoma patients undergoing anti-programmed death 1 (PD-1) immunotherapy to determine the prognostic biomarkers of immunotherapy response125. They found that mitochondrial metabolic pathways including branched-chain amino acid degradation, fatty acid oxidation, and oxidative phosphorylation activation are related to high response to immunotherapy125. ALDH2 is one of the proteins in ranched-chain amino acid degradation, whose expression is higher in the anti-PD1 responder group compared to the patients of the non-response patients group125. Our study also shows that a combination of ALDH2 inhibition and PD-1 blockade, which increases tumor infiltration of TILs and prevents immune evasion, is a novel strategy for potentiating immunotherapy in murine CT26 colon cancer model (unpublished data).

6. Conclusions and perspectives

ALDH2 plays a key role in ethanol metabolism. This study, however, shows that ALDH2 is correlated with occurrence and progression of cancer. While genetic and epigenetic regulation of ALDH2 expression and the function of ALDH2 in the development of cancer has attracted a lot of research, there remains a lot of gaps in the subject. For instance, the role of ALDH2 in oncogenic signaling pathways is only partially understood. A better understanding of this can help in understanding the functions of ALDH2 in cancer. ALDH2 also exists in different parts of cells like mitochondrion, cytosol, nuclear, etc. Exosomal ALDH2 was found in normal human urine, and we suspect that cancer cells can secrete ALDH2. In addition, the dominant participant in aldehyde metabolism is ALDH2 in mitochondria, whereas the functions of ALDH2 in other locations are still unknown.

ALDH2 has a double-edged activity. It can be antioncogenic by reducing the damaging effects of aldehydes, and be oncogenic as well by promoting drug resistance and signaling cell survival. ALDH2∗2 affects about 30%–40% Asians and about 8% global populations. ALDH2∗2 variant carriers are susceptible to HNC, EC, GCA and HCC due to acetaldehyde accumulation. However, the correlation between CRC and ALDH2∗2 remains confusion. Regarding the protection of cancer, if these individuals have no other alternative, they could use the ALDH2 activator to prevent cancer, especially populations with both ALDH2 and FANCD or BRCA mutations. Some studies suggest that ALDH2 overexpression or high activity is correlated with MDR, such as antimetabolic medicines, microtubule inhibitors, and anthracyclines. Accordingly, perhaps individual-based therapy is necessary for ALDH2 variant carriers, and targeting it could be a novel method to overcome MDR in patients with ALDH2 overexpression. Our study also indicates that downregulation of ALDH2 could enhance PD-1 blockade immunotherapy in murine CT26 colon cancer model (unpublished data). In addition, the ALDH2 inhibitors are designed to only target their activation sites for suppression without affecting their expression. More researches should be done to establish whether the ALDH2 expression inhibitors are superior to their activity antagonists in cancer treatment. The study shows that ALDH2 regulates the proliferation, invasion, and migration of cancer cells. More researches are required to establish whether ALDH2 can serve as a cancer stem cell marker. More researches should also be done to establish whether ALDH2 expression level is associated with the effect of immunotherapy in solid tumors.

In summary, many researchers have elaborated the potential functions of ALDH2 in cancer treatment. Populations with ALDH2∗2 polymorphism are susceptible to cancers such as EC, GCA, and HCC. In addition, ALDH2 is also associated with cancer prognosis because it can be a cancer stem cell marker that regulates the proliferation, invasion, migration, and MDR of cancer cells. Many theories about cancer occurrence and development caused by ALDH2 deficiency include: gene mutations, epigenetic instability, autophagy, and immune system dysfunction. Meanwhile, the regulation of ALDH2 expressions such as transcriptional factors, post-transcriptional factors, and post-transcriptional modulators was obtained and identified. ALDH2 expression is associated with the therapeutic effect of chemotherapy, molecular targeted treatment, and immunotherapy. A better understanding of the relationship between ALDH2 and cancer can provide a basis for clinical use, and new strategies of treating cancer patients by targeting ALDH2.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673463), the National Key Research and Development Program (No. 2018ZX09711002-003-011, China), the Guangdong Provincial Special Fund for Marine Economic Development Project (GDNRC [2020]042, China), and Leading Talent Project of Guangzhou Development Zone (CY2018-002, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Author contributions

Hong Zhang wrote the paper. Liwu Fu revised the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yoval-Sanchez B., Rodriguez-Zavala J.S. Differences in susceptibility to inactivation of human aldehyde dehydrogenases by lipid peroxidation byproducts. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:722–729. doi: 10.1021/tx2005184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heymann H.M., Gardner A.M., Gross E.R. Aldehyde-induced DNA and protein adducts as biomarker tools for alcohol use disorder. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonzales P.A., Pisitkun T., Hoffert J.D., Tchapyjnikov D., Star R.A., Kleta R. Large-scale proteomics and phosphoproteomics of urinary exosomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:363–379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cui R., Kamatani Y., Takahashi A., Usami M., Hosono N., Kawaguchi T. Functional variants in ADH1B and ALDH2 coupled with alcohol and smoking synergistically enhance esophageal cancer risk. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1768–1775. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou G., Chen L., Liu G., Li L., Yang Y., Yan H.X. Aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) opposes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating AMP-activated protein kinase signaling in mice. Hepatology. 2017;65:1628–1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.29006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kallifatidis G., Smith D.K., Morera D.S., Gao J., Hennig M.J., Hoy J.J. β-Arrestins regulate stem cell-like phenotype and response to chemotherapy in bladder cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18:801–811. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks P.J., Enoch M.A., Goldman D., Li T.K., Yokoyama A. The alcohol flushing response: an unrecognized risk factor for esophageal cancer from alcohol consumption. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farres J., Wang X., Takahashi K., Cunningham S.J., Wang T.T., Weiner H. Effects of changing glutamate 487 to lysine in rat and human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. A model to study human (oriental type) class 2 aldehyde dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13854–13860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferencz-Biro K., Pietruszko R. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase: catalytic activity in oriental liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;118:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J., Weiner H. Basis for half-of-the-site reactivity and the dominance of the K487 oriental subunit over the E487 subunit in heterotetrameric human liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12019–12024. doi: 10.1021/bi001221k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koyanagi Y.N., Suzuki E., Imoto I., Kasugai Y., Oze I., Ugai T. Across-site differences in the mechanism of alcohol-induced digestive tract carcinogenesis: an evaluation by mediation analysis. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1601–1610. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu C., Guo Y., Bian Z., Yang L., Millwood I.Y., Walters R.G. Association of low-activity ALDH2 and alcohol consumption with risk of esophageal cancer in Chinese adults: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2018;143:1652–1661. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin C.M., Kim N., Cho S.I., Kim J.S., Jung H.C., Song I.S. Association between alcohol intake and risk for gastric cancer with regard to ALDH2 genotype in the Korean population. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1047–1055. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hidaka A., Sasazuki S., Matsuo K., Ito H., Sawada N., Shimazu T. Genetic polymorphisms of ADH1B, ADH1C and ALDH2, alcohol consumption, and the risk of gastric cancer: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:223–231. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishioka K., Masaoka H., Ito H., Oze I., Ito S., Tajika M. Association between ALDH2 and ADH1B polymorphisms, alcohol drinking and gastric cancer: a replication and mediation analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21:936–945. doi: 10.1007/s10120-018-0823-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang H., Zhou Y., Zhou Z., Liu J., Yuan X., Matsuo K. A novel polymorphism rs1329149 of CYP2E1 and a known polymorphism rs671 of ALDH2 of alcohol metabolizing enzymes are associated with colorectal cancer in a southwestern Chinese population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2522–2527. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masaoka H., Ito H., Soga N., Hosono S., Oze I., Watanabe M. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) and alcohol dehydrogenase 1B (ADH1B) polymorphisms exacerbate bladder cancer risk associated with alcohol drinking: gene-environment interaction. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:583–588. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgw033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiraki A., Matsuo K., Wakai K., Suzuki T., Hasegawa Y., Tajima K. Gene-gene and gene-environment interactions between alcohol drinking habit and polymorphisms in alcohol-metabolizing enzyme genes and the risk of head and neck cancer in Japan. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1087–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsai S.T., Wong T.Y., Ou C.Y., Fang S.Y., Chen K.C., Hsiao J.R. The interplay between alcohol consumption, oral hygiene, ALDH2 and ADH1B in the risk of head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:2424–2436. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suo C., Yang Y., Yuan Z., Zhang T., Yang X., Qing T. Alcohol intake interacts with functional genetic polymorphisms of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) to increase esophageal squamous cell cancer risk. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:712–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanda J., Matsuo K., Suzuki T., Kawase T., Hiraki A., Watanabe M. Impact of alcohol consumption with polymorphisms in alcohol-metabolizing enzymes on pancreatic cancer risk in Japanese. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:296–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.01044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakamoto T., Hara M., Higaki Y., Ichiba M., Horita M., Mizuta T. Influence of alcohol consumption and gene polymorphisms of ADH2 and ALDH2 on hepatocellular carcinoma in a Japanese population. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1501–1507. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomoda T., Nouso K., Sakai A., Ouchida M., Kobayashi S., Miyahara K. Genetic risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus: a case control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:797–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avincsal M.O., Shinomiya H., Teshima M., Kubo M., Otsuki N., Kyota N. Impact of alcohol dehydrogenase-aldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphism on clinical outcome in patients with hypopharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2018;40:770–777. doi: 10.1002/hed.25050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinomiya H., Shinomiya H., Kubo M., Saito Y., Yoshida M., Ando M. Prognostic value of ALDH2 polymorphism for patients with oropharyngeal cancer in a Japanese population. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang P.H., Hu C.C., Chien C.H., Chen L.W., Chien R.N., Lin Y.S. The defective allele of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 gene is associated with favorable postoperative prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10:5735–5743. doi: 10.7150/jca.33221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seo W., Gao Y., He Y., Sun J., Xu H., Feng D. ALDH2 deficiency promotes alcohol-associated liver cancer by activating oncogenic pathways via oxidized DNA-enriched extracellular vesicles. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1000–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin G., Kono S., Toyomura K., Moore M.A., Nagano J., Mizoue T. Alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase polymorphisms and colorectal cancer: the Fukuoka colorectal cancer study. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1248–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J., Yang H.I., Lee M.H., Jen C.L., Hu H.H., Lu S.N. Alcohol drinking mediates the association between polymorphisms of ADH1B and ALDH2 and hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:693–699. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao H., Liu K.J., Lei Z.D., Lei S.L., Tian Y.Q. Meta-analysis of the aldehyde dehydrogenases-2 (ALDH2) Glu487Lys polymorphism and colorectal cancer risk. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ugai T., Kelemen L.E., Mizuno M., Ong J.S., Webb P.M., Chenevix-Trench G. Ovarian cancer risk, ALDH2 polymorphism and alcohol drinking: Asian data from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:435–445. doi: 10.1111/cas.13470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hashibe M., Boffetta P., Zaridze D., Shangina O., Szeszenia-Dabrowska N., Mates D. Evidence for an important role of alcohol- and aldehyde-metabolizing genes in cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:696–703. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duell E.J., Sala N., Travier N., Munoz X., Boutron-Ruault M.C., Clavel-Chapelon F. Genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1A, ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH7) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2), alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:361–367. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka F., Yamamoto K., Suzuki S., Inoue H., Tsurumaru M., Kajiyama Y. Strong interaction between the effects of alcohol consumption and smoking on oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma among individuals with ADH1B and/or ALDH2 risk alleles. Gut. 2010;59:1457–1464. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.205724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu C., Kraft P., Zhai K., Chang J., Wang Z., Li Y. Genome-wide association analyses of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Chinese identify multiple susceptibility loci and gene-environment interactions. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1090–1097. doi: 10.1038/ng.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eom S.Y., Zhang Y.W., Kim S.H., Choe K.H., Lee K.Y., Park J.D. Influence of NQO1, ALDH2, and CYP2E1 genetic polymorphisms, smoking, and alcohol drinking on the risk of lung cancer in Koreans. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:137–145. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park J.Y., Matsuo K., Suzuki T., Ito H., Hosono S., Kawase T. Impact of smoking on lung cancer risk is stronger in those with the homozygous aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 null allele in a Japanese population. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:660–665. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao Y., He Y., Xu J., Xu L., Du J., Zhu C. Genetic variants at 4q21, 4q23 and 12q24 are associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk in a Chinese population. Hum Genet. 2013;132:649–656. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abiko S., Shimizu Y., Miyamoto S., Ishikawa M., Matsuda K., Tsuda M. Risk assessment of metachronous squamous cell carcinoma after endoscopic resection for esophageal carcinoma based on the genetic polymorphisms of alcoholdehydrogense-1B aldehyde dehydrogenase-2: temperance reduces the risk. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1120–1130. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muto M., Hitomi Y., Ohtsu A., Ebihara S., Yoshida S., Esumi H. Association of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 gene polymorphism with multiple oesophageal dysplasia in head and neck cancer patients. Gut. 2000;47:256–261. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yokoyama A., Muramatsu T., Omori T., Yokoyama T., Matsushita S., Higuchi S. Alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase gene polymorphisms and oropharyngolaryngeal, esophageal and stomach cancers in Japanese alcoholics. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:433–439. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muto M., Takahashi M., Ohtsu A., Ebihara S., Yoshida S., Esumi H. Risk of multiple squamous cell carcinomas both in the esophagus and the head and neck region. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1008–1012. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee W.T., Hsiao J.R., Ou C.Y., Huang C.C., Chang C.C., Tsai S.T. The influence of prediagnosis alcohol consumption and the polymorphisms of ethanol-metabolizing genes on the survival of head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:248–257. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zahid K.R., Yao S., Khan A.R.R., Raza U., Gou D. mTOR/HDAC1 crosstalk mediated suppression of ADH1A and ALDH2 links alcohol metabolism to hepatocellular carcinoma onset and progression in silico. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1000. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrew A.S., Gui J., Hu T., Wyszynski A., Marsit C.J., Kelsey K.T. Genetic polymorphisms modify bladder cancer recurrence and survival in a USA population-based prognostic study. BJU Int. 2015;115:238–247. doi: 10.1111/bju.12641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li K., Guo W., Li Z., Wang Y., Sun B., Xu D. ALDH2 repression promotes lung tumor progression via accumulated acetaldehyde and DNA damage. Neoplasia. 2019;21:602–614. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2019.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L., Wu M., Ji C., Yuan M., Liu C., Yin Q. Silencing transcription factor FOXM1 represses proliferation, migration, and invasion while inducing apoptosis of liver cancer stem cells by regulating the expression of ALDH2. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:285–295. doi: 10.1002/iub.2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen X., Legrand A.J., Cunniffe S., Hume S., Poletto M., Vaz B. Interplay between base excision repair protein XRCC1 and ALDH2 predicts overall survival in lung and liver cancer patients. Cell Oncol. 2018;41:527–539. doi: 10.1007/s13402-018-0390-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart M.J., Dipple K.M., Estonius M., Nakshatri H., Everett L.M., Crabb D.W. Binding and activation of the human aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 promoter by hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1399:181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinaire J., Hasanadka R., Fang M., Chou W.Y., Stewart M.J., Kruijer W. The retinoid X receptor response element in the human aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 promoter is antagonized by the chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter family of orphan receptors. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;380:192–200. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao Y.H., Wu Z.X., Xie L.Q., Li C.X., Mao Y.Q., Duan Y.T. VHL deficiency augments anthracycline sensitivity of clear cell renal cell carcinomas by down-regulating ALDH2. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15337. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H., Xue L., Li B., Zhang Z., Tao S. Vitamin D protects against alcohol-induced liver cell injury within an NRF2–ALDH2 feedback loop. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201801014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kitakaze T., Makiyama A., Samukawa Y., Jiang S., Yamashita Y., Ashida H. A physiological concentration of luteolin induces phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes through the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in HepG2 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019;663:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nowak S.J., Pai C.Y., Corces V.G. Protein phosphatase 2A activity affects histone H3 phosphorylation and transcription in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6129–6138. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.6129-6138.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Almeida L.O., Goto R.N., Pestana C.R., Uyemura S.A., Gutkind S., Curti C. SET overexpression decreases cell detoxification efficiency: ALDH2 and GSTP1 are downregulated, DDR is impaired and DNA damage accumulates. FEBS J. 2012;279:4615–4628. doi: 10.1111/febs.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gebert L.F.R., MacRae I.J. Regulation of microRNA function in animals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:21–37. doi: 10.1038/s41580-018-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deng X., Yin Z., Zhou Z., Wang Y., Zhang F., Hu Q. Carboxymethyl dextran-stabilized polyethylenimine-poly(epsilon-caprolactone) nanoparticles-mediated modulation of microRNA-34a expression via small-molecule modulator for hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:17068–17079. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b03122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oner M.G., Rokavec M., Kaller M., Bouznad N., Horst D., Kirchner T. Combined inactivation of TP53 and MIR34A promotes colorectal cancer development and progression in mice via increasing levels of IL6R and PAI1. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1868–1882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bayraktar R., Ivan C., Bayraktar E., Kanlikilicer P., Kabil N.N., Kahraman N. Dual suppressive effect of miR-34a on the FOXM1/eEF2-kinase axis regulates triple-negative breast cancer growth and invasion. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:4225–4241. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weng Y.S., Tseng H.Y., Chen Y.A., Shen P.C., Al H.A.T., Chen L.M. MCT-1/miR-34a/IL-6/IL-6R signaling axis promotes EMT progression, cancer stemness and M2 macrophage polarization in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:42. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0988-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gibori H., Eliyahu S., Krivitsky A., Ben-Shushan D., Epshtein Y., Tiram G. Amphiphilic nanocarrier-induced modulation of PLK1 and miR-34a leads to improved therapeutic response in pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9:16. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng J., Zhou L., Xie Q.F., Xie H.Y., Wei X.Y., Gao F. The impact of miR-34a on protein output in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells. Proteomics. 2010;10:1557–1572. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Balassiano K., Lima S., Jenab M., Overvad K., Tjonneland A., Boutron-Ruault M.C. Aberrant DNA methylation of cancer-associated genes in gastric cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-EURGAST) Cancer Lett. 2011;311:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harris P.S., Gomez J.D., Backos D.S., Fritz K.S. Characterizing sirtuin 3 deacetylase affinity for aldehyde dehydrogenase 2. Chem Res Toxicol. 2017;30:785–793. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu Z., Bourdi M., Li J.H., Aponte A.M., Chen Y., Lombard D.B. SIRT3-dependent deacetylation exacerbates acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:840–846. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei S.J., Xing J.H., Wang B.L., Xue L., Wang J.L., Li R. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition prevents reactive oxygen species induced inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:479–486. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torrens-Mas M., Oliver J., Roca P., Sastre-Serra J. SIRT3: oncogene and tumor suppressor in cancer. Cancers. 2017;9:90. doi: 10.3390/cancers9070090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Picklo M.J., Sr. Ethanol intoxication increases hepatic N-lysyl protein acetylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shulga N., Pastorino J.G. Ethanol sensitizes mitochondria to the permeability transition by inhibiting deacetylation of cyclophilin-D mediated by sirtuin-3. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4117–4127. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 70.Moon K.H., Lee Y.M., Song B.J. Inhibition of hepatic mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase by carbon tetrachloride through JNK-mediated phosphorylation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhong S., Li L., Zhang Y.L., Zhang L., Lu J., Guo S. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 interactions with LDLR and AMPK regulate foam cell formation. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:252–267. doi: 10.1172/JCI122064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nene A., Chen C.H., Disatnik M.H., Cruz L., Mochly-Rosen D. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activation and coevolution of its epsilonPKC-mediated phosphorylation sites. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24:3. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0312-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xiao Q., Weiner H., Crabb D.W. The mutation in the mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) gene responsible for alcohol-induced flushing increases turnover of the enzyme tetramers in a dominant fashion. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2027–2032. doi: 10.1172/JCI119007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jin S., Chen J., Chen L., Histen G., Lin Z., Gross S. ALDH2(E487K) mutation increases protein turnover and promotes murine hepatocarcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9088–9093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510757112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zinczuk J., Maciejczyk M., Zareba K., Romaniuk W., Markowski A., Kedra B. Antioxidant barrier, redox status, and oxidative damage to biomolecules in patients with colorectal cancer. can malondialdehyde and catalase be markers of colorectal cancer advancement?. Biomolecules. 2019;9:637. doi: 10.3390/biom9100637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rasic I., Rasic A., Aksamija G., Radovic S. The relationship between serum level of malondialdehyde and progression of colorectal cancer. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57:411–416. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.03.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sawczuk B., Maciejczyk M., Sawczuk-Siemieniuk M., Posmyk R., Zalewska A., Car H. Salivary gland function, antioxidant defence and oxidative damage in the saliva of patients with breast cancer: does the BRCA1 mutation disturb the salivary redox profile?. Cancers. 2019;11:1501. doi: 10.3390/cancers11101501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cucci M.A., Compagnone A., Daga M., Grattarola M., Ullio C., Roetto A. Post-translational inhibition of YAP oncogene expression by 4-hydroxynonenal in bladder cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;141:205–219. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Timucin A.C., Basaga H. Pro-apoptotic effects of lipid oxidation products: HNE at the crossroads of NF-kappaB pathway and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2. Free Radic Biol Med. 2017;111:209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yang Y., Huycke M.M., Herman T.S., Wang X. Glutathione S-transferase alpha 4 induction by activator protein 1 in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:5795–5806. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hu W., Feng Z., Eveleigh J., Iyer G., Pan J., Amin S. The major lipid peroxidation product, trans-4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, preferentially forms DNA adducts at codon 249 of human p53 gene, a unique mutational hotspot in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1781–1789. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.11.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kotova N., Vare D., Schultz N., Gradecka M.D., Stepnik M., Grawe J. Genotoxicity of alcohol is linked to DNA replication-associated damage and homologous recombination repair. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:325–330. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matsuda T., Kawanishi M., Yagi T., Matsui S., Takebe H. Specific tandem GG to TT base substitutions induced by acetaldehyde are due to intra-strand crosslinks between adjacent guanine bases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1769–1774. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.7.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yukawa Y., Ohashi S., Amanuma Y., Nakai Y., Tsurumaki M., Kikuchi O. Impairment of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 increases accumulation of acetaldehyde-derived DNA damage in the esophagus after ethanol ingestion. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;4:279–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Matsuda T., Yabushita H., Kanaly R.A., Shibutani S., Yokoyama A. Increased DNA damage in ALDH2-deficient alcoholics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:1374–1378. doi: 10.1021/tx060113h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Grafstrom R.C., Dypbukt J.M., Sundqvist K., Atzori L., Nielsen I., Curren R.D. Pathobiological effects of acetaldehyde in cultured human epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 1994;15:985–990. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.5.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garro A.J., McBeth D.L., Lima V., Lieber C.S. Ethanol consumption inhibits fetal DNA methylation in mice: implications for the fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1991;15:395–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1991.tb00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen D., Fang L., Li H., Jin C. The effects of acetaldehyde exposure on histone modifications and chromatin structure in human lung bronchial epithelial cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2018;59:375–385. doi: 10.1002/em.22187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Niemela O., Mannermaa R.M., Oikarinen J. Impairment of histone H1 DNA binding by adduct formation with acetaldehyde. Life Sci. 1990;47:2241–2249. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90155-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Langevin F., Crossan G.P., Rosado I.V., Arends M.J., Patel K.J. Fancd2 counteracts the toxic effects of naturally produced aldehydes in mice. Nature. 2011;475:53–58. doi: 10.1038/nature10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alcon P., Shakeel S., Chen Z.A., Rappsilber J., Patel K.J., Passmore L.A. FANCD2-FANCI is a clamp stabilized on DNA by monoubiquitination of FANCD2 during DNA repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:240–248. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0380-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen J., Shukla V., Farci P., Andricovich J., Jogunoori W., Kwong L.N. Loss of the transforming growth factor-beta effector beta2-Spectrin promotes genomic instability. Hepatology. 2017;65:678–693. doi: 10.1002/hep.28927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garaycoechea J.I., Crossan G.P., Langevin F., Mulderrig L., Louzada S., Yang F. Alcohol and endogenous aldehydes damage chromosomes and mutate stem cells. Nature. 2018;553:171–177. doi: 10.1038/nature25154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Abraham J., Balbo S., Crabb D., Brooks P.J. Alcohol metabolism in human cells causes DNA damage and activates the Fanconi anemia-breast cancer susceptibility (FA-BRCA) DNA damage response network. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:2113–2120. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01563.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tacconi E.M., Lai X., Folio C., Porru M., Zonderland G., Badie S. BRCA1 and BRCA2 tumor suppressors protect against endogenous acetaldehyde toxicity. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:1398–1414. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201607446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Elezaby M., Lees B., Maturen K.E., Barroilhet L., Wisinski K.B., Schrager S. BRCA mutation carriers: breast and ovarian cancer screening guidelines and imaging considerations. Radiology. 2019;291:554–569. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Garcia J.M., Rodriguez R., Dominguez G., Silva J.M., Provencio M., Silva J. Prognostic significance of the allelic loss of the BRCA1 gene in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2003;52:1756–1763. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Page E.C., Bancroft E.K., Brook M.N., Assel M., Hassan A.B.M., Thomas S. Interim results from the IMPACT study: evidence for prostate-specific antigen screening in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Eur Urol. 2019;76:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patel V.L., Busch E.L., Friebel T.M., Cronin A., Leslie G., McGuffog L. Association of genomic domains in BRCA1 and BRCA2 with prostate cancer risk and aggressiveness. Cancer Res. 2020;80:624–638. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hodskinson M.R., Bolner A., Sato K., Kamimae-Lanning A.N., Rooijers K., Witte M. Alcohol-derived DNA crosslinks are repaired by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2020;579:603–608. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2059-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tanaka K., Whelan K.A., Chandramouleeswaran P.M., Kagawa S., Rustgi S.L., Noguchi C. ALDH2 modulates autophagy flux to regulate acetaldehyde-mediated toxicity thresholds. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6:781–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Guo R., Xu X., Babcock S.A., Zhang Y., Ren J. Aldehyde dedydrogenase-2 plays a beneficial role in ameliorating chronic alcohol-induced hepatic steatosis and inflammation through regulation of autophagy. J Hepatol. 2015;62:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 103.Shen C., Wang C., Fan F., Yang Z., Cao Q., Liu X. Acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) deficiency exacerbates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by inhibiting Beclin-1 dependent autophagy pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu B., Yu L., Wang Y., Wang H., Li C., Yin Y. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activation in aged heart improves the autophagy by reducing the carbonyl modification on SIRT1. Oncotarget. 2016;7:2175–2188. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ganesan M., Krutik V.M., Makarov E., Mathews S., Kharbanda K.K., Poluektova L.Y. Acetaldehyde suppresses the display of HBV-MHC class I complexes on HBV-expressing hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2019;317:G127–G140. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kunugita N., Isse T., Oyama T., Kitagawa K., Ogawa M., Yamaguchi T. Increased frequencies of micronucleated reticulocytes and T-cell receptor mutation in Aldh2 knockout mice exposed to acetaldehyde. J Toxicol Sci. 2008;33:31–36. doi: 10.2131/jts.33.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gao Y., Zhou Z., Ren T., Kim S.J., He Y., Seo W. Alcohol inhibits T-cell glucose metabolism and hepatitis in ALDH2-deficient mice and humans: roles of acetaldehyde and glucocorticoids. Gut. 2019;68:1311–1322. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ishikawa H., Yamamoto H., Tian Y., Kawano M., Yamauchi T., Yokoyama K. Effects of ALDH2 gene polymorphisms and alcohol-drinking behavior on micronuclei frequency in non-smokers. Mutat Res. 2003;541:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(03)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ishikawa H., Miyatsu Y., Kurihara K., Yokoyama K. Gene-environmental interactions between alcohol-drinking behavior and ALDH2 and CYP2E1 polymorphisms and their impact on micronuclei frequency in human lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2006;594:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Morimoto K., Takeshita T. Low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2) polymorphism, alcohol-drinking behavior, and chromosome alterations in peripheral lymphocytes. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104 Suppl 3:563–567. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104s3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thiele G.M., Duryee M.J., Willis M.S., Tuma D.J., Radio S.J., Hunter C.D. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by syngeneic liver cytosolic proteins biotransformed by alcohol metabolites. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:2126–2136. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rolla R., Vay D., Mottaran E., Parodi M., Traverso N., Arico S. Detection of circulating antibodies against malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology. 2000;31:878–884. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tuma D.J. Role of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in liver injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stewart S.F., Vidali M., Day C.P., Albano E., Jones D.E. Oxidative stress as a trigger for cellular immune responses in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2004;39:197–203. doi: 10.1002/hep.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Aslibekyan S., Brown E.E., Reynolds R.J., Redden D.T., Morgan S., Baggott J.E. Genetic variants associated with methotrexate efficacy and toxicity in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the treatment of early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis trial. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14:48–53. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wang N.N., Wang L.H., Li Y., Fu S.Y., Xue X., Jia L.N. Targeting ALDH2 with disulfiram/copper reverses the resistance of cancer cells to microtubule inhibitors. Exp Cell Res. 2018;362:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Koppaka V., Thompson D.C., Chen Y., Ellermann M., Nicolaou K.C., Juvonen R.O. Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitors: a comprehensive review of the pharmacology, mechanism of action, substrate specificity, and clinical application. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:520–539. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Skrott Z., Mistrik M., Andersen K.K., Friis S., Majera D., Gursky J. Alcohol-abuse drug disulfiram targets cancer via p97 segregase adaptor NPL4. Nature. 2017;552:194–199. doi: 10.1038/nature25016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Skrott Z., Majera D., Gursky J., Buchtova T., Hajduch M., Mistrik M. Disulfiram's anti-cancer activity reflects targeting NPL4, not inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase. Oncogene. 2019;38:6711–6722. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ge W., Yuan M., Ceylan A.F., Wang X., Ren J. Mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase protects against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through a transient receptor potential channel vanilloid 1-mediated mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1862:622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sun A., Cheng Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Q., Wang S., Tian S. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced myocardial dysfunction through detoxification of 4-HNE and suppression of autophagy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;71:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]