Abstract

Background

Sore throat is a common reason for consultation of primary care physicians, pediatricians, and ENT specialists. The updated German clinical practice guideline on sore throat provides evidence-based recommendations for treatment in the framework of the German healthcare system.

Methods

Guideline revision by means of a systematic search of the literature for international guidelines and systematic reviews. All recommendations were developed by an interdisciplinary guideline committee and agreed by formal consensus. The updated guideline applies to patients aged 3 years and over.

Results

In the absence of red flags such as immunosuppression, severe comorbidity, or severe systemic infection, acute sore throat is predominantly self-limiting. The mean duration is 7 days. Chronic sore throat usually has noninfectious causes. Laboratory tests are not routinely necessary. Apart from non-pharmacological self-management, ibuprofen and naproxen are recommended for symptomatic treatment. Scores can be used to assess the risk of bacterial pharyngitis: one point each is assigned for purulent or inflamed tonsils, palpable cervical lymph nodes, patient age, disease course, and elevated temperature. If the risk is low (<3 points), antibiotics are not indicated; if at least moderate (3 points), delayed prescribing is recommended; if high (>3 points), antibiotics can be taken immediately. Penicillin remains the first choice, with clarithromycin as an alternative for those who do not tolerate penicillin. The antibiotic should be taken for 5–7 days.

Conclusion

After the exclusion of red flags, antibiotic treatment is unnecessary in many cases of acute sore throat. If administration of antibiotics is still considered in spite of patient education on the usual course of tonsillopharyngitis and the low risk of complications, a risk-adapted approach using clinical scores is recommended.

Sore throat is No. 6 on the list of most common reasons for visiting a primary care physician and accounts for 2.7% of all primary care consultations in Germany (1). Acute sore throat is usually caused by viral infections of the pharynx. Bacterial pathogens, such as streptococci, are detected in tonsillopharyngitis in only 20.2%–34% of cases, depending on the seasonal and regional conditions and age group (2, 3). A German study conducted in 2018 with 61 primary care practices found group A streptococci (GAS) in only 15% of patients with sore throat (4). While GAS are nearly always the cause of bacterial tonsillopharyngitis in children, group C and G streptococci are found in up to 12% of cases in adults. Only a handful of primary studies on the prescribing practice of general practitioners in cases of suspected bacterial tonsillopharyngitis are available for Germany and have low case numbers. A 2005 survey found an antibiotic prescription rate of approximately 90% in primary care patients with suspected tonsillitis, whereas a 2016 study found a rate of 41% on initial presentation (5, 6). Non-beneficial prescribing of antibiotics represents an unnecessary risk for patients and promotes the development of resistance (7).

Sore throat is defined as chronic if it persists for more than 14 days, in which case noninfectious causes are more likely. From a differential diagnostic perspective, one should consider physicochemical factors (post-intubation status, smoking, snoring, medications, reflux), voice strain and overuse, concomitant diseases, and adverse drug effects (8).

The German clinical practice guideline “Sore Throat,” which was updated in 2020, takes into account a newly developed clinical score, as well as the principle of delayed prescribing, and presents a revised treatment algorithm.

Methods

To compile the evidence base, a literature search was performed to find current versions of the source guidelines, which were evaluated using the AGREE-II instrument (9). A systematic search was also conducted for review articles, which were evaluated using the AMSTAR-2 instrument. Search strategies and evaluations are described in the eMethods.

The recommendations were discussed and agreed upon in the consensus committee. For any remaining recommendations and text passages on which no consensus had previously been reached, consensus was subsequently established by means of a Delphi procedure. All parties that participated in the development of the guideline are listed in the eBox. The guideline recommendations are given here with strength of recommendation and level of evidence, while statements are accompanied by level of evidence (etable 1).

eBOX. Participants involved in guideline development.

● The following participants were responsible for the evidence-based guideline revision:

Dr. med. Karen Krüger, Dr. med. Jan Hendrik Oltrogge, Prof. Dr. med. Jean-François Chenot, PD Dr. med. Markus Bickel, Prof. Dr. med. Reinhard Berner, Dr. med. Nicole Töpfner, Prof. Dr. med. Jochen Windfuhr, Prof. Dr. med. Rainer Laskawi, PD Dr. med. Guido Schmiemann, Prof. Dr. Gesine Weckmann

● Authors of and collaborators on the guideline report included:

Dr. med. Karen Krüger, Dr. med. Petra Jung, Dr. rer. nat. Karin Ettlinger, Dr. med. Anton Wartner, Dr. med. Jan Hendrik Oltrogge

● The following individuals participated in the consensus process:

Prof. Dr. med. Reinhard Berner, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin e. V. (DGKJ))

PD Dr. med. Markus Bickel, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Infektiologie (DGI)

Dr. med. Karen Krüger, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM)

Prof. Dr. med. Rainer Laskawi and Prof. Dr. med. Jochen Windfuhr (Stellvertreter), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf- und Hals-Chirurgie (DGHNO-KHC)

Dr. med. Jan Hendrik Oltrogge (Leitlinienkoordination), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM)

Dr. med. Nicole Töpfner, Deutsche Gesellschaft für pädiatrische Infektiologie (DGPI)

Moderation: Dr. rer. hum. Cathleen Muche-Borowski

● Additional advisers included:

Dr. med. Hannelore Wächtler, Dr. med. Felix Holzinger

● The following members of the DEGAM guideline committee commented on the guideline:

Prof. Dr. med. Erika Baum, Dr. med. Achim Mainz, Dr. med. Günther Egidi

eTable 1. Strength of recommendation and level of evidence.

| Grade | Strength of recommendation |

| A | High strength of recommendation |

| B | Medium strength of recommendation |

| 0 | Low strength of recommendation |

| Grade | Level of evidence |

| Ia | Highest level, evidence from meta-analyses or systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials |

| Ib | Evidence from individual randomized controlled studies |

| II | Evidence from cohort studies |

| III | Evidence from case-control studies |

| IV | Evidence from case series |

| V | Expert consensus with systematic literature search, no studies found |

| GCP | Expert consensus without a systematic literature search: Good Clinical Practice |

Results

A total of 19 source guidelines (efigure 1) were evaluated, as were 14 guidelines following a search in guideline portals (efigure 2) and 122 guidelines following a systematic search in Medline via PubMed (efigure 3). Altogether, seven guidelines of high methodological quality and relevance for the key questions were identified (10– 16).

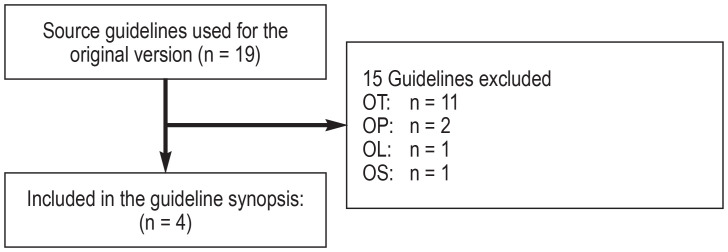

eFigure 1.

Flow diagram: update of the source guidelines used for the original version

Abbreviations of reasons for exclusion:

OS: Other subject

OP: Other type of publication

OW: Withdrawn

OL: Language other than English or German

OT: Other time of publication or search (no update/older than 5 years)

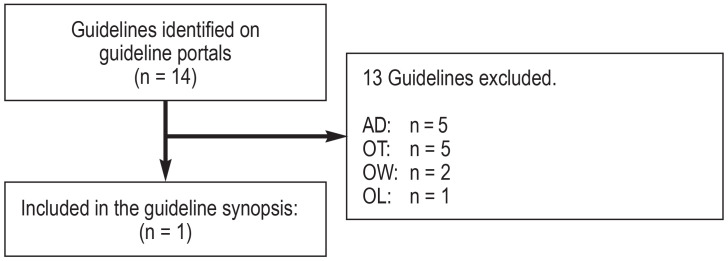

eFigure 2.

Flow diagram: guideline portal search

(see eFigure 1 for abbreviations of the reasons for exclusion)

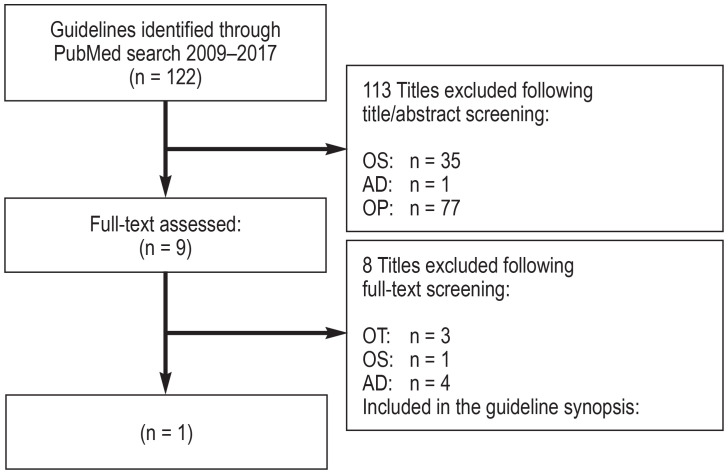

eFigure 3.

Flow diagram: systematic guideline search in Medline via PubMed

(see eFigure 1 for abbreviations of the reasons for exclusion)

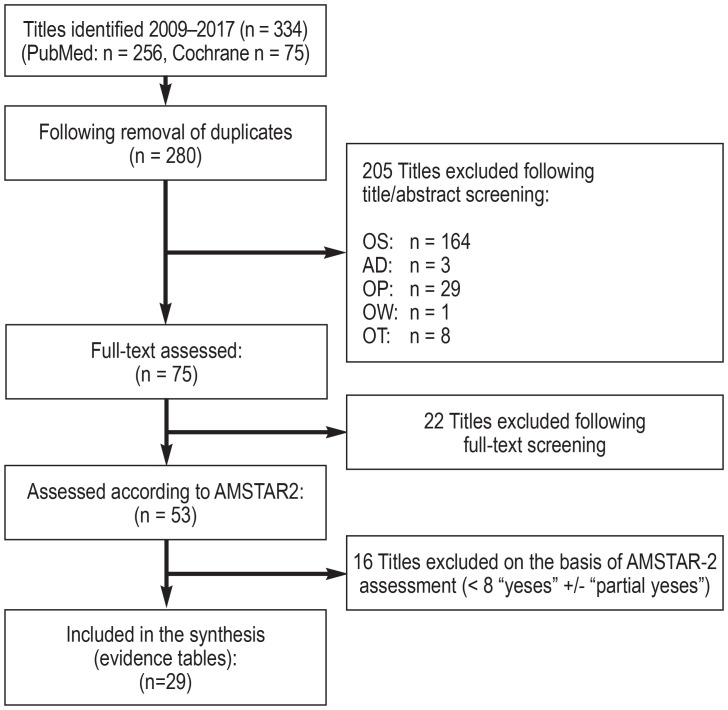

The search for reviews and meta-analyses in Medline via PubMed and in the Cochrane Database yielded 334 hits, of which 29 systematic reviews of high quality and relevance were included (efigure 4). Since guidelines and reviews provided a sufficient evidence base, no systematic search for original papers was performed.

eFigure 4.

Flow diagram: systematic search for review articles in Medline via PubMed and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

The 29 systematic reviews included were summarized in evidence tables. The evidence tables can be found in full in Appendix B of the guideline report.

(See eFigure 1 for abbreviations of reasons for exclusion)

In all, 10 statements and 17 recommendations were unanimously adopted, while there was one abstention each for four guideline recommendations (17).

Guideline recommendations

Preventable high-risk disease courses: specific problems

In addition to tonsillopharyngitis with typical symptoms and findings (such as sore throat and pain swallowing, elevated temperature, pharyngeal erythema, possible tonsillar exudates, and cervical lymph node swelling), fulminant courses, systemic diseases, as well as other differential diagnoses requiring individualized decision-making or referral to another level of care need to be differentiated in the case of corresponding symptoms or underlying disease (table 1).

Table 1. Overview of red flags for sore throat, as well as how to proceed in the case of preventable high-risk courses and re-evaluation.

| Individual approach in the case of the following red flags: | Referral to an ENT specialist in the case of: | Immediate admission to hospital in the case of: | Re-evaluation if there is no improvement after 3–4 days |

| Suspected scarlet fever Suspected infectious mononucleosis A different focus of infection (pneumonia, bronchitis, otitis media, sinusitis) Typical conditions involving severe immunosuppression Increased risk of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) Severe comorbidities |

Suspected neoplasm Suspected peritonsillar abscess (presentation on same day, otherwise hospital admission) Persisting > 6 weeks Recurrent acute tonsillitis (if more than six times per year: check indication for surgery) |

Stridor or difficulty breathing (suspected epiglottitis, infectious mononucleosis) Signs of severe systemic disease (e.g., meningitis, diphtheria, Kawasaki syndrome, Lemierre’s syndrome) Signs of severe suppurative complications (peritonsillar and para- or retropharyngeal abscess) Exsiccation |

Consider the following: Differential diagnoses (such as infectious mononucleosis) Signs or symptoms of more serious/systemic disease Previous antibiotic treatment (resistance development!) |

Complications and sequelae

High-risk complications of sore throat are very rare in countries such as Germany, Great Britain, and the Netherlands (Statement, 1a).

Suppurative complications (otitis media, peritonsillar abscess, sinusitis, bacterial skin infections) occur in less than 1.4% of cases of acute sore throat (18). The most common non-suppurative complications worldwide that can develop as a result of GAS tonsillopharyngitis include acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN). The annual incidence of ARF in Germany is estimated to be less than 1/1 000 000 inhabitants (19). The incidence in many developing countries is far higher. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), which develops in 30–80% as a result of ARF, represents the most frequent cause of acquired heart diseases in high-incidence countries. Patients at high risk for the development of ARF include:

ARF or RHD in the patient’s own or family history

Crowding (an above average number of persons per household/dwelling) (20)

Current positive migration history for regions with a high incidence of ARF (≥ 2/100 000 schoolchildren) or high prevalence of RHD (≥1/1000 population-years), for example, sub-Saharan Africa, South and Central Asia, as well as Oceania

Belonging to population groups with a high incidence of ARF (≥ 2/100 000 schoolchildren) or high prevalence of RHD (≥ 1/1000 population-years), for example, populations in sub-Saharan Africa, South and Central Asia, Oceania, as well as Maoris in New Zealand) (21).

APSGN is rare in Germany and generally has a good prognosis for complete resolution. It has not been demonstrated that antibiotic treatment of the primary infection is able to prevent APSGN (22).

Clinical diagnosis

From a clinical perspective, it is not possible to reliably distinguish between viral, bacterial, and noninfectious pharyngitis (Statement, Ia). However, the ascertainment of symptoms and findings may increase the likelihood of a viral or bacterial etiology in acute sore throat (11, 14), meaning that a shared decision can be made on the initiation of antibiotic therapy on this basis.

Clinical scores

Clinical scores estimate the probability of microbiological detection of beta-hemolytic streptoccici in a throat swab in acute tonsillopharyngitis. One point each is assigned for defined findings in the medical history and clinical examination, such as elevated temperature, patient age, disease course, pharyngeal and tonsillar findings, as well as cervical lymph node swelling (box 1). New to the guideline is a consideration of the FeverPAIN score published in 2013 (23). For the Centor and McIsaac scores, external validation with high case numbers is now available (24). Use of the FeverPAIN score in a British study resulted in a 27–29% reduction in antibiotic administration with no increase in complications or readmissions (23, 25). The guideline recommends that a clinical score be determined in patients (aged ≥ 3 years) with acute sore throat and no red flags (table 1) if antibiotic therapy is being considered (B, Ib). A comparison of the three scores made it possible, irrespective of the score used, to define a low risk (≤ 2 points: 0–20%), a medium risk (3 points: 30–50%), and a high risk (≥ 4 points: over 50%) for the presence of bacterial tonsillopharyngitis (table 2).

BOX 1. Risk assessment scores.

-

FeverPAIN score (1 point each):

Elevated temperature in the preceding 24 h

Tonsillar exudates

Presentation to a physician within 3 days due to severity of symptoms

Pronounced redness and swelling of the tonsils

No cough or rhinitis

-

Centor score (1 point each):

Tonsillar exudates

Cervical lymphadenopathy

History of temperature elevated above 38 °C

No cough

-

McIsaac score (1 point each):

Tonsillar exudates

Cervical lymphadenopathy

History of temperature elevated above 38 °C

No cough

Patient < 15 years: + 1 point

Patient > 45 years: - 1 point

Table 2. Comparison of the three clinical scores.

| Clinical score | Low risk | Moderate risk | High risk | Pretest probability* |

| Centor (age ≥ 15 years) |

0–2 Points 13% GAS (LR+ 0.5) |

3 Points 38% GAS (LR+ 2.1) |

4 Points 57% GAS (LR+ 4.4) |

23% GAS (n = 142,081) |

| McIsaac (age ≥ 3 years) |

0–2 Points 11% GAS (LR+ 0.3) |

3 Points 37% GAS (LR+ 1.6) |

4–5 Points 55% GAS (LR+ 3.3) |

27 % GAS (n = 206,870) |

| FeverPAIN (age ≥ 3 years) |

0–2 Points 16% A/C/G strep (LR+ 0.3) |

3 Points 43% A/C/G strep (LR+ 1.3) |

4–5 Points 63% A/C/G strep (LR+ 2.9) |

37% A/C/G strep (25% GAS, 12% non-GAS) (n = 1109) |

The table gives the percentage of persons within the study population with evidence of beta-hemolytic streptococci in a throat swab and the positive likelihood ratio (LR+).

* Data on pretest probability and study population were taken from the validation study (Centor and McIsaac score [24]) as well as from the derivation study of the FeverPAIN score (25).

GAS, group A streptococci

Determination of laboratory parameters

Laboratory parameters, such as leukocytes, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and procalcitonin, should not be routinely determined as part of the diagnostic work-up in patients with acute sore throat (lasting < 14 days) in the absence of red flags (Statement, Good Clinical Practice [GCP]).

Rapid tests for group A streptococci

In randomized controlled trials, the use of rapid GAS testing conferred no benefits in terms of symptom duration or readmission and complication rates compared to the use of scores alone (23, 25). However, in contrast to adults, children and adolescents in Germany have a very low prevalence of tonsillopharyngitis caused by non-group-A streptococci. Therefore, the guideline supports the use of rapid tests in the case of medium to high clinical probability of streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis (≥ 3 score points) in children aged 3–15 years. In the case of a negative GAS rapid test, unnecessary antibiotic treatment can be dispensed with.

Microbiological culture detection is not routinely recommended either before or after antibiotic therapy. Exceptions apply to patients with signs of notifiable diseases, diseases requiring treatment, atypical pathogens in known immunosuppression, and risk constellations for ARF (see Sect. “Complications and sequelae”) (26).

Since 2020, COVID-19 needs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of all new-onset respiratory symptoms. The suspicion is supported primarily by the concomitant occurrence of acute sore throat and symptoms typical for COVID-19, such as cough, elevated temperature, difficulty breathing, and sudden loss of sense of smell and taste, as well as by the occurrence of sore throat on its own following contact with individuals that have tested positive. The current regional incidence rate also needs to be included in the testing strategy. If COVID-19 is suspected, additional diagnostic testing and treatment in line with the current guidelines need to be initiated (27).

Taking red flags into consideration

An important step in the treatment of acute sore throat is the identification of red flags in the clinical history and examination (box 1).

Patients with red flags may belong to groups whose risk for severe disease courses is difficult to assess since these groups are often excluded from controlled trials:

Conditions with severe immunosuppression, such as long-term use of systemic steroids, organ transplantation, stem cell transplantation, AIDS, neutropenia, and other congenital or acquired immune defects

Severe comorbidities.

The presence of red flags may also point to other diseases for which there are different guidelines or treatment recommendations:

Scarlet fever

Infectious mononucleosis

Respiratory infections, such as pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis, otitis media.

Therefore, the evidence-based recommendations described below for the treatment of sore throat are only applicable once red flags have been ruled out.

Consultation

A medical consultation is indispensable for a shared decision-making process. A consensus was reached in the guideline on recommendations relating to the content of the consultation. In addition to what is likely to be a self-limiting 1-week disease course, the low risk of complications should also be mentioned and guidance on self-management provided. If antibiotic therapy is desired, its individual benefit needs to be weighed up against adverse events prior to administration (box 2).

BOX 2. Patient consultation.

The following points should be addressed with all patients (age ≥ 3 years) presenting with acute sore throat (< 14 days duration) without red flags (GCP):

Disease course is likely to be self-limiting (lasting approximately 1 week)

Low risk of suppurative complications requiring treatment

Self-management (for example, fluids, physical rest, other non-pharmacological measures)

Estimated probability of the presence of bacterial tonsillopharyngitis based on medical history and assessment of findings

-

Advantages and disadvantages of antibiotic treatment:

Shortening of symptoms by on average 16 h

High number needed to treat (NNT) of approximately 200 patients to prevent suppurative complications

Rate of adverse drug reactions (diarrhea, anaphylaxis, mycoses) is approximately 10% with antibiotic treatment

If asked, point out that the estimated incidence of ARF and APSGN in Germany is very low. There is no evidence that either ARF or APSGN can be prevented with antibiotic treatment.

APSGN, acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis; ARF, acute rheumatic fever; GCP, Good Clinical Practice

Symptomatic treatment with throat preparations

The guideline endorses with only a weak level of recommendation the use of throat preparations (lozenges, gargle solutions, sprays) containing local anesthetics and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Cases of methemoglobinemia have been described with local anesthetics (28). Although these adverse events are rare, one should take into account the fact that, at best, throat preparations offer low efficacy for a very limited period of time against what are already self-limiting symptoms.

The guideline explicitly advises against local antiseptic- and/or antibiotic-containing throat preparations with a strong level of recommendation since the vast majority of cases of acute sore throat are viral infections. These substances can cause severe allergic reactions (29, 30). However, there is no data available on the frequencies of these events.

Symptomatic treatment with oral corticosteroids

Corticosteroids should not be used for analgesic treatment of sore throat (A, 1a). The evidence for any efficacy of oral corticosteroids in acute sore throat is derived almost exclusively from studies that tested the administration of corticosteroids in addition to an established treatment. A 2017 study showed evidence for an earlier resolution of sore throat after 48 h with a single dose of dexamethasone (31). This evidence was considered to be an insufficient basis on which to recommend the administration of oral corticosteroids for symptoms treatable by self-management and over-the-counter substances.

Symptomatic treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol

Ibuprofen or naproxen can be offered for the short-term symptomatic treatment of sore throat (O, Ib). A Cochrane review conducted in 2013 found insufficient evidence of efficacy for paracetamol in resolving symptoms of the common cold (32). A 2011 systematic review described efficacy of NSAIDs for sore throat in the first 24 h (12 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]; significant improvement in 25–75% of patients) and after 2–5 days (six RCTs, significant improvement in 33–93% of patients) (33). The longest experience with ibuprofen has been gained in pediatrics. Among the NSAIDs, diclofenac is associated with a higher risk for cardiovascular events (34).

Benefits of antibiotic treatment

Sore throat (even of bacterial etiology) does not represent a general indication for antibiotic administration (Statement, Ia). Therefore, the updated guideline explicitly supports foregoing antibiotic treatment in the German healthcare context, even in the case of strong clinical suspicion of bacterial tonsillopharyngitis. The “number needed to treat” (NNT) to avoid suppurative complications through antibiotic administration is extremely high at 194 patients (18). A Cochrane meta-analysis calculated that antibiotics shorten symptoms by on average 16 h (35). Thus, the primary goal of antibiotic treatment in patients aged ≥ 3 years with acute sore throat is to shorten the duration of the disease rather than to prevent complications.

If the physician is considering—or the patient is expecting—antibiotic treatment in the absence of red flags, the guideline recommends that the treatment decision be made on the basis of one of the three clinical scores (strength of recommendation B, II) (box 1). Antibiotic treatment is not recommended in the case of a point score of < 3. From a point score of 3, the principle of delayed prescribing (DP) is recommended; immediate antibiotic therapy should only be offered from a point score of 4 at the earliest. DP refers to the issuing of a prescription that is only redeemed by the patient if symptoms worsen or do not improve after 3–5 days. In controlled studies, only around a third of these prescriptions were used, thereby significantly reducing antibiotic use without causing an increase in complications (25, 36).

Selection of the active substance and treatment duration

If antibiotic treatment is to be performed, either by DP or by immediate administration, the following active substances are recommended (strength of recommendation A, Ia):

-

Adolescents (> 15 years) and adults:

Penicillin V 0.8–1.0 million IU orally three times daily for 5–7 days

In the case of penicillin intolerance: clarithromycin 250–500 mg orally twice daily for 5 days.

-

Children (3–15 years):

Penicillin V 0.05–0.1 million IU/kg body weight/day divided into three single oral doses for 5–7 days

In the case of penicillin intolerance: clarithromycin 15 mg/kg body weight/day divided into two single oral doses for 5 days.

The risk of adverse drug reactions and the development of resistance increases with increasing duration of antibiotic use (7). Therefore, the guideline recommends restricting the duration of use to between 5 and a maximum of 7 days. Pathogen eradication with 10-day penicillin should be reserved for individual cases at increased risk for a severe course (GCP). Taking penicillin at midday may be difficult in patients aged 3–15 years (for example, if they attend community facilities). In these cases, it is possible to divide the daily dose of penicillin V into two doses (mornings and evenings) (Statement; Ia).

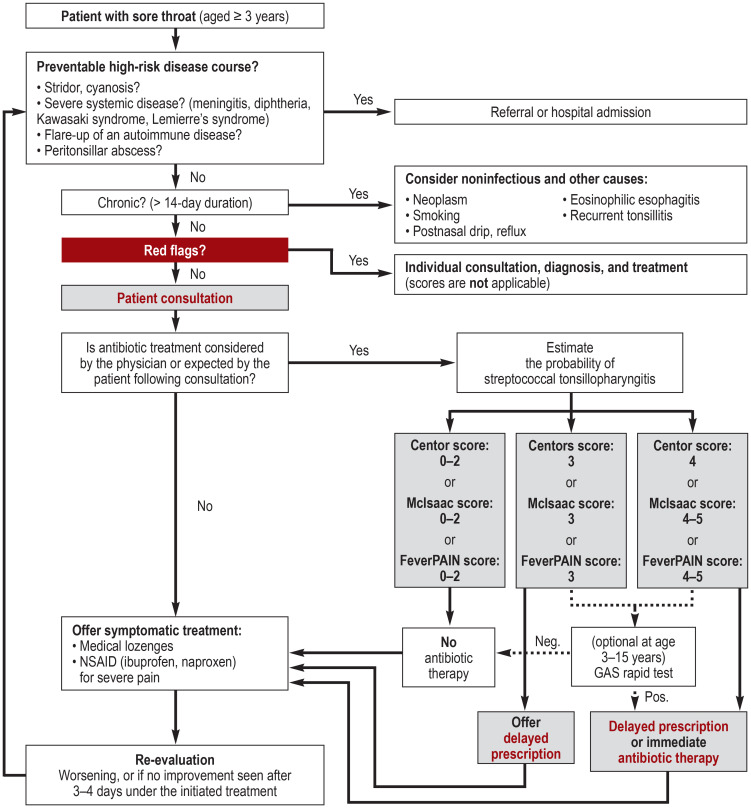

The recommendations on the approach to sore throat are summarized in a clinical algorithm (figure).

Figure.

Clinical algorithm on the approach to sore throat

GAS, group A streptococci; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Recurrent acute tonsillitis

Frequent or recurrent episodes of sore throat can be burdensome for the patient and justify the desire for causal treatment. When considering surgical treatment, an assessment of (ideally medically documented and treated) episodes of sore throat, defined as follows, is recommended:

Elevated temperature > 38.3 ºC (oral) or

Purulent tonsils or

New-onset painful cervical lymph node swelling or

Detection of streptococcus in the swab.

From a frequency of six episodes or more in the preceding 12 months, tonsillectomy or tonsillotomy is a therapeutic option (GCP). Given the heterogeneous quality of data, the basis for decision-making in this regard is consensus-based and applies to patients aged 3 years and older (37).

If tonsillectomy is not possible or undesired, a one-off attempt at pharmacological eradication of the pathogens with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid or clindamycin can be made during the sore throat episode (0, Ia). If data on long-term effects are lacking, adverse events and complications with the two treatment options must always be weighed against the spontaneous recovery rate for recurrent acute tonsillitis.

Research needs

The process of updating the guideline gave rise to further research questions:

How high is the age-dependent pretest probability for group A streptococcal versus non-group A streptococcal tonsillopharyngitis in Germany?

How high is the age-dependent incidence of poststreptococcal disease in Germany?

How effective is delayed prescribing for acute respiratory infections in terms of avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use in Germany?

What are the long-term effects of tonsillectomy and tonsillotomy for recurrent acute tonsillitis?

Supplementary Material

eMethods

Systematic guideline search

As part of the revision of the original 2009 version of the AWMF clinical practice guideline “Sore Throat” (AWMF Registry No. 053–010), a systematic search for new source guidelines was conducted. The search was limited to clinical guidelines in English and German.

Search for updates of the source guidelines used for the original version

In a first step, the source guidelines cited in the original 2009 version (n = 19) were checked for currentness. The inclusion criterion with regard to currentness was defined as a time of publication dating back less than 5 years from the date of the systematic search for the update, 16.11.2017 (flowchart: eFigure 1).

Guideline portal search

A search was also conducted in the following guideline portals (flow diagram: eFigure 2):

Database search

An additional search in Medline via PubMed (www.pubmed.org) was undertaken with the following search strategy (flow diagram: eFigure 3):

Search (((nasopharyngitis[MeSH Terms] OR nasopharyngit*[Title/Abstract]) OR ((tonsillitis[MeSH Terms]) OR tonsillit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (sore throat[MeSH Terms]) OR ((sore*[Title/Abstract]) AND throat*[Title/Abstract]) OR (pharyngitis[MeSH Terms] OR pharyngit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (rhinopharyngitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (rhinopharyngit*[Title/Abstract])) AND ((“german”[Language] OR “english”[Language]) AND ((“Guidelines as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Health Planning Guidelines”[Mesh] OR “Practice Guidelines as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Guideline”[Publication Type] OR “Standard of Care”[Mesh] OR “Evidence-Based Practice”[Mesh] OR “Evidence-Based Medicine”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Protocols”[Mesh]) OR “Practice Guideline”[Publication Type]))) AND (“2009/10/01”[Date – Publication]: “2017/11/16”[Date – Publication]).

Source guidelines included

In summary, six evidence-based clinical guidelines were found using this method (10– 13, 15, 16). After completion of the systematic search, one additional evidence-based guideline was included by consensus among the guideline committee due to currentness and relevance of the subject matter (14).

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the source guidelines included

The methodological quality of the source guidelines found was evaluated in each case by two authors of the guideline report (9) using the AGREE II instrument (38). An overall rating of ≥ 50% was defined as the cut-off for inclusion as source guidelines in the guideline update. A detailed overview of the individual results of the rating can be found in the guideline report, while the full synopsis of the guideline can be found in Appendix A of the guideline report (9).

Systematic search for systematic review articles

In order to update the original version, a systematic search for systematic reviews was performed in Medline via PubMed and in the Cochrane Library (etable 2).

PICO model used:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the systematic reviews included

The methodological quality of the systematic reviews found was evaluated in each case by two authors of guideline report (9) using the AMSTAR-2 instrument (39). The 16 AMSTAR-2 questions on methodological quality were answered with “yes,” “partial yes,” or “no” and “not applicable.” A cut-off of at least eight “yeses” or “partial yeses” was specified for the inclusion of a systematic review. As a result of this approach, a total of 29 systematic reviews were included in the synthesis (flow diagram in eFigure 4). The evidence tables are provided in full in Appendix B of the guideline report of the clinical practice guideline “Sore Throat” (9).

Grading strength of recommendation and level of evidence

The recommendations in this guideline have been graded to indicate their strength of recommendation and the quality of the studies on which they are based (evidence level). The grading of evidence level was carried out on the basis of the Oxford evidence grading system (2009 version, available at www.cebm.net). An overview of the grades used can be found in eTable 1.

NGC National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guidelines.gov); Suchstrategie: (“pharyngitis” OR “tonsillitis” OR “nasopharyngitis” OR “rhinopharyngitis” OR “tonsillopharyngitis” OR “sore throat”) + Clinical Speciality: “Family practice” + Publication year: 2009 to 2017

GIN Guidelines international network (www.g-i-n.net); Suchstrategie: “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis” OR “tonsillitis” OR “nasopharyngitis” OR “rhinopharyngitis” OR “tonsillopharyngitis”

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany; www.awmf.de); search terms: Pharyngitis OR Tonsillitis OR Nasopharyngitis OR Rhinopharyngitis OR Tonsillopharyngitis OR Pharyngotonsillitis OR Halsschmerzen.

Population: sore throat, tonsillitis, pharyngitis

Intervention: no restrictions

Comparison: no restrictions

Study Type: only systematic reviews

eTable 2. PubMed search strategy (www.pubmed.org) (16 November 2017).

| No. | Search query | Number | |

| #1 | Search (((nasopharyngitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (nasopharyngit* [Title/Abstract]) OR (tonsillitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (tonsillit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (sore throat[MeSH Terms]) OR ((sore*[Title/Abstract]) AND (throat*[Title/Abstract])) OR (pharyngitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (pharyngit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (rhinopharyngitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (rhinopharyngit*[Title/Abstract])) AND ((“german”[Language]) OR (“english”[Language])) AND (“2009/10/01”[Date –Publication] : “2017/11/16”[Date – Publication]) AND (“systematic”[Filter])) | 259 | |

| Number of hits: 259 | |||

| Cochrane Library database search strategy (www.cochranelibrary.com) (16 November 2017) | |||

| No. | Search query | Number | |

| #1 | “sore throat”:ti,ab,kw or “pharyngitis”:ti,ab,kw or “tonsillitis”:ti,ab,kw or “nasopharyngitis”:ti,ab,kw or “rhinopharyngitis”:ti,ab,kw Publication Year from 2009 to 2017, in Other Reviews and Technology Assessments (Word variations have been searched) | 74 | |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Pharyngitis] explode all trees | 1074 | |

| #3 | #1 OR #2, Publication Year from 2009 to 2017, in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews only), Other Reviews and Technology Assessments | 75 | |

| Number of hits: 75 | |||

| Summary of database search results | |||

| Medline | Cochrane databases | Total | |

| Hits | 259 | 75 | 334 |

Acknowledgments

Clinical practice guidelines in the Deutsches Ärzteblatt, as in numerous other specialist journals, are not subject to a peer review procedure, since clinical practice guidelines represent texts that have already been evaluated, discussed, and broadly agreed upon multiple times by experts (peers).

Translated from the original German by Christine Rye.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all authors of and participants in the DEGAM Clinical practice guideline on Sore Throat:

Prof. Dr. med. Jean-François Chenot, PD Dr. med. Markus Bickel, Prof. Dr. med. Rainer Laskawi, PD Dr. med. Guido Schmiemann, Prof. Dr. Gesine Weckmann, Dr. med. Petra Jung, Dr. rer. nat. Karin Ettlinger, Dr. med. Anton Wartner, Dr. med. Hannelore Wächtler, Dr. med. Felix Holzinger, Dr. rer. hum. Cathleen Muche-Borowski, Prof. Dr. med. Erika Baum, Dr. med. Achim Mainz, Dr. med. Günther Egidi.

Funding

The guideline was funded by resources of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin, DEGAM), the Department of General Practice and Primary Care (Institut und Poliklinik für Allgemeinmedizin) at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), and the Institute of General Practice (Institut für Allgemeinmedizin) at the Charité.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Berner received speaker’s fees from Infectopharm.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Kühlein T, Laux G, Gutscher A, Szecsenyi J. Urban & Vogel. München: 2008. Kontinuierliche Morbiditätsregistrierung in der Hausarztpraxis Vom Beratungsanlass zum Beratungsergebnis; 48 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronman MP, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Bacterial prevalence and antimicrobial prescribing trends for acute respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e956–e965. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little P, Hobbs FR, Mant D, McNulty CA, Mullee M. Incidence and clinical variables associated with streptococcal throat infections: a prospective diagnostic cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:e787–e794. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X658322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansmann-Wiest J, Kaduszkiewicz H, Hedderich J, et al. DEGAM-Leitlinie zur Senkung der Antibiotikaverschreibungsrate bei Halsschmerzen geeignet? Kongressbeitrag, Kongress für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin Innsbruck, 2018. www.egms.de/static/en/meetings/degam2018/18degam086.shtml (last accessed on 23 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer T, Fischer S, Kochen MM, Hummers-Pradier E. Influence of patient symptoms and physical findings on general practitioners’ treatment of respiratory tract infections: a direct observation study. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maaß S. Diagnostik und Therapie bei Halsschmerzpatienten in der hausärztlichen Praxis: eine epidemiologische Studie. Christian-Albrechts Universität Kiel. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renner B, Mueller CA, Shephard A. Environmental and non-infectious factors in the aetiology of pharyngitis (sore throat) Inflamm Res. 2012;61:1041–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00011-012-0540-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oltrogge J, Krüger K. DEGAM S3-Leitlinie Nr 14 „Halsschmerzen“ AWMF-Register-Nr. 053-010. Leitlinienreport. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trauzeddel R, Neudorf U. S2k Leitlinie „Rheumatisches Fieber - Poststreptokokkenarthritis im Kindes- und Jugendalter“ AWMF-Register-Nr. 023-027. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Kardiologie. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randel A. IDSA updates guideline for managing group a streptococcal pharyngitis. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:338–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiappini E, Mazzantini R, Bruzzese E, et al. Rational use of antibiotics for the management of children’s respiratory tract infections in the ambulatory setting: an evidence-based consensus by the Italian Society of Preventive and Social Pediatrics. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2014;15:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schott G, Lasek R, Ludwig W-D. Therapieempfehlungen der Arzneimittelkommission der deutschen Ärzteschaft. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2008;102:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NICE Guideline (NG 84) Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84 (last accessed on 25 June 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Windfuhr JP, Berner R, Steffen G, Waldfahrer F. S2k Leitlinie „Therapie entzündlicher Erkrankungen der Gaumenmandeln-Tonsillitis“, AWMF-Register-Nr 017-024. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hals-Nasen-Ohren-Heilkunde, Kopf- und Hals-Chirurgie. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 16.NICE Clinical Guideline (CG 69) Respiratory tract infections (self-limiting): prescribing antibiotics. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg69 (last accessed on 29 December 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oltrogge J, Krüger K. DEGAM S3-Leitlinie Nr 14 „Halsschmerzen“ AWMF-Register-Nr. 053-010. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FDR, et al. Antibiotic prescription strategies for acute sore throat: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Koskull S. Incidence and prevalence of juvenile arthritis in an urban population of southern Germany: a prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:940–945. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.10.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coffey PM, Ralph AP, Krause VL. The role of social determinants of health in the risk and prevention of group A streptococcal infection, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006577. e0006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sims Sanyahumbi A, Colquhoun S, Wyber R, Carapetis JR. Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editors. Global disease burden of group A streptococcus. Streptococcus pyogenes: basic biology to clinical manifestations. University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center. 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor JL, Howie JGR. Antibiotics, sore throats and acute nephritis. JR Coll Gen Pract. 1983;33:783–786. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little P, Hobbs FDR, Moore M, et al. Clinical score and rapid antigen detection test to guide antibiotic use for sore throats: randomised controlled trial of PRISM (primary care streptococcal management) BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine AM, Nizet V, Mandl KD. Large-scale validation of the Centor and McIsaac scores to predict group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:847–852. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little P, Hobbs FR, Moore M, et al. PRImary care Streptococcal Management (PRISM) study: in vitro study, diagnostic cohorts and a pragmatic adaptive randomised controlled trial with nested qualitative study and cost-effectiveness study. Health Technol Assess. 2014 doi: 10.3310/hta18060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group a streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:e86–e102. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blankenfeld H, Kaduszkiewicz H, Kochen MM, et al. DEGAM S1-Handlungsempfehlung „Neues Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) - Informationen für die hausärztliche Praxis“ AWMF-Register-Nr 053-054. Langfassung Version 14, 09/2020 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seibert RW, Seibert JJ. Infantile methemoglobinemia induced by a topical anesthetic, Cetacaine. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:816–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giovannini M, Sarti L, Barni S, Pucci N, Novembre E, Mori F. Anaphylaxis to over-the-counter flurbiprofen in a child. PHA. 2017;99:121–123. doi: 10.1159/000452671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calapai G, Imbesi S, Cafeo V, et al. Fatal hypersensitivity reaction to an oral spray of flurbiprofen: a case report. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38:337–338. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayward GN, Hay AD, Moore MV, et al. Effect of oral dexamethasone without immediate antibiotics vs placebo on acute sore throat in adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317:1535–1543. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li S, Yue J, Dong BR, Yang M, Lin X, Wu T. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for the common cold in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008800.pub2. CD008800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenealy T. Sore throat. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt M, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L. Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: series of nationwide cohort studies. BMJ. 2018 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinks A, Glasziou PP, Del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000023. CD000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spurling GK, Del Mar CB, Dooley L, Foxlee R, Farley R. Delayed antibiotic prescriptions for respiratory infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004417.pub5. CD004417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Windfuhr JP. Evidenz basierte Indikationen der Tonsillektomie. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie. 2016;95:S38–S87. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-109590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1308–1311. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

Systematic guideline search

As part of the revision of the original 2009 version of the AWMF clinical practice guideline “Sore Throat” (AWMF Registry No. 053–010), a systematic search for new source guidelines was conducted. The search was limited to clinical guidelines in English and German.

Search for updates of the source guidelines used for the original version

In a first step, the source guidelines cited in the original 2009 version (n = 19) were checked for currentness. The inclusion criterion with regard to currentness was defined as a time of publication dating back less than 5 years from the date of the systematic search for the update, 16.11.2017 (flowchart: eFigure 1).

Guideline portal search

A search was also conducted in the following guideline portals (flow diagram: eFigure 2):

Database search

An additional search in Medline via PubMed (www.pubmed.org) was undertaken with the following search strategy (flow diagram: eFigure 3):

Search (((nasopharyngitis[MeSH Terms] OR nasopharyngit*[Title/Abstract]) OR ((tonsillitis[MeSH Terms]) OR tonsillit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (sore throat[MeSH Terms]) OR ((sore*[Title/Abstract]) AND throat*[Title/Abstract]) OR (pharyngitis[MeSH Terms] OR pharyngit*[Title/Abstract]) OR (rhinopharyngitis[MeSH Terms]) OR (rhinopharyngit*[Title/Abstract])) AND ((“german”[Language] OR “english”[Language]) AND ((“Guidelines as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Health Planning Guidelines”[Mesh] OR “Practice Guidelines as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Guideline”[Publication Type] OR “Standard of Care”[Mesh] OR “Evidence-Based Practice”[Mesh] OR “Evidence-Based Medicine”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Protocols”[Mesh]) OR “Practice Guideline”[Publication Type]))) AND (“2009/10/01”[Date – Publication]: “2017/11/16”[Date – Publication]).

Source guidelines included

In summary, six evidence-based clinical guidelines were found using this method (10– 13, 15, 16). After completion of the systematic search, one additional evidence-based guideline was included by consensus among the guideline committee due to currentness and relevance of the subject matter (14).

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the source guidelines included

The methodological quality of the source guidelines found was evaluated in each case by two authors of the guideline report (9) using the AGREE II instrument (38). An overall rating of ≥ 50% was defined as the cut-off for inclusion as source guidelines in the guideline update. A detailed overview of the individual results of the rating can be found in the guideline report, while the full synopsis of the guideline can be found in Appendix A of the guideline report (9).

Systematic search for systematic review articles

In order to update the original version, a systematic search for systematic reviews was performed in Medline via PubMed and in the Cochrane Library (etable 2).

PICO model used:

Evaluation of the methodological quality of the systematic reviews included

The methodological quality of the systematic reviews found was evaluated in each case by two authors of guideline report (9) using the AMSTAR-2 instrument (39). The 16 AMSTAR-2 questions on methodological quality were answered with “yes,” “partial yes,” or “no” and “not applicable.” A cut-off of at least eight “yeses” or “partial yeses” was specified for the inclusion of a systematic review. As a result of this approach, a total of 29 systematic reviews were included in the synthesis (flow diagram in eFigure 4). The evidence tables are provided in full in Appendix B of the guideline report of the clinical practice guideline “Sore Throat” (9).

Grading strength of recommendation and level of evidence

The recommendations in this guideline have been graded to indicate their strength of recommendation and the quality of the studies on which they are based (evidence level). The grading of evidence level was carried out on the basis of the Oxford evidence grading system (2009 version, available at www.cebm.net). An overview of the grades used can be found in eTable 1.

NGC National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guidelines.gov); Suchstrategie: (“pharyngitis” OR “tonsillitis” OR “nasopharyngitis” OR “rhinopharyngitis” OR “tonsillopharyngitis” OR “sore throat”) + Clinical Speciality: “Family practice” + Publication year: 2009 to 2017

GIN Guidelines international network (www.g-i-n.net); Suchstrategie: “sore throat” OR “pharyngitis” OR “tonsillitis” OR “nasopharyngitis” OR “rhinopharyngitis” OR “tonsillopharyngitis”

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany; www.awmf.de); search terms: Pharyngitis OR Tonsillitis OR Nasopharyngitis OR Rhinopharyngitis OR Tonsillopharyngitis OR Pharyngotonsillitis OR Halsschmerzen.

Population: sore throat, tonsillitis, pharyngitis

Intervention: no restrictions

Comparison: no restrictions

Study Type: only systematic reviews