ABSTRACT

Background

Periconceptional folic acid (FA) supplementation is recommended to prevent neural tube defects; however, the extent to which recommendations are met through dietary sources and supplements is not clear.

Objectives

Our objective was to evaluate the dietary and supplemental intakes of FA in a Canadian pregnancy cohort and to determine the proportions of pregnant women exceeding the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) and Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL).

Methods

FACT (the Folic Acid Clinical Trial) was an international multicenter, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase III trial investigating FA for the prevention of pre-eclampsia in high-risk pregnancies. Participants were enrolled from Canadian sites at 8–16 weeks of gestation. Dietary and supplemental FA intake data were collected through participant interviews and FFQs at the time of FACT enrollment. Categorical data were summarized as n (%) and continuous data as median (IQR).

Results

This study included 1198 participants. Participants consumed 485 μg dietary folate equivalents (DFE)/d (IQR: 370–630 μg DFE/d) from dietary sources of folate and FA. Through diet alone, 43.4% of participants consumed ≥520 μg DFE/d, the EAR for pregnant individuals. Of the 91.9% of participants who consumed daily FA supplements, 0.4% consumed <400 μg FA/d and 96.0% consumed ≥1000 μg/d, the UL for FA. Median (IQR) total folate intake was 2167 μg DFE/d (2032–2325 μg DFE/d); 95.3% of participants met or exceeded the EAR from all sources, but 1069 (89.2%) participants exceeded the UL.

Conclusions

The majority of participants in this Canadian pregnancy cohort did not consume the recommended amount of folate from dietary sources. However, most prenatal supplements contained 1000 μg FA, resulting in the majority of women exceeding the UL. With no additional benefit associated with FA intakes beyond the UL for most women, modification of prenatal supplement formulations may be warranted to ensure women meet but do not exceed recommended FA intakes.

FACT was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT01355159 and at isrctn.com as ISRCTN23781770.

Keywords: vitamin B-9, folic acid, folate, supplementation, pregnancy

Introduction

Folate is an essential cofactor for one-carbon metabolism. Its synthetic derivative, folic acid (FA), is used in food fortification and vitamin supplements for the prevention of neural tube defects (NTDs) (1–4). The implications of NTDs vary from mild physical and functional impairments to paralysis, cognitive morbidities, and fetal death. The Estimated Average Requirement (EAR) of combined dietary folate equivalents (DFE) for pregnant women is 520 μg DFE/d and the RDA is 600 μg/d, higher than those for nonpregnant adults (5). In addition, the Institute of Medicine recommends that women of childbearing age consume 400 μg FA from diet or supplements (5). Although dietary folate sources are varied—including leafy and dark green vegetables and legumes—many women do not achieve adequate folate intake from natural food sources alone (6, 7). To address this issue, in 1998, the Government of Canada mandated FA fortification of white flour, enriched pasta, and enriched cornmeal products (8–10). To further mitigate the risk of NTDs, the Government of Canada also recommends that in addition to consuming a healthy diet, all women who could become pregnant should take a daily multivitamin containing 400 μg FA (11). This is consistent with the advice of other professional guidelines (8, 12–16).

In Canada, prenatal FA supplement recommendations range between 400 μg/d for women with no personal or family history of FA-sensitive defects and 5 mg/d where either the male or female partner has a personal NTD history or has had a previously affected pregnancy (8, 17, 18). However, because prenatal supplements in Canada contain almost exclusively 1000 μg FA, most women who consume prenatal supplements in combination with any quantity of FA-fortified foods likely exceed the intake amounts needed to provide the optimal NTD risk reduction benefits. In fact, through combined consumption of FA-fortified foods and prenatal supplements, many women will exceed the Tolerable Upper Intake Level (UL) for FA (1000 μg/d), an amount based on the potential for high-dose FA to mask signs and accelerate neurological complications associated with a vitamin B-12 deficiency (5). Studies have suggested that although 36%–47% of pregnant women in Canada would not meet the EAR if they were to consume dietary sources of folate alone, 67%–90% of women would exceed the UL for FA through combined intake of fortified foods and supplements (6, 7, 19).

Data on the relative contributions of dietary and supplement intake to total folate and FA intakes in the Canadian pregnant population are limited by small sample sizes or focused on geographic regions. Further evaluation of FA intake among pregnant Canadian women is warranted to determine whether intake is aligned with or in excess of current recommendations. The objective of this study was to evaluate early pregnancy folate and FA intake among pregnant women with risk factors for pre-eclampsia, but not necessarily NTDs, from across Canada. The extent to which folate and FA intake recommendations were met through dietary sources and supplement use was assessed.

Methods

Study design and population

This substudy was nested within FACT (the Folic Acid Clinical Trial; ISRCTN23781770), an international, multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized control trial which investigated the effect of high-dose FA supplementation on risk of developing pre-eclampsia (20). Participants were recruited on the basis of having ≥1 of the following risk factors for pre-eclampsia: pre-existing hypertension, prepregnancy diabetes (type 1 or 2), twin pregnancy, diagnosis of pre-eclampsia in a previous pregnancy, or BMI ≥35 kg/m2. In Canada, women were recruited from 23 hospital sites across 8 provinces: Ontario, Québec, British Columbia, Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland.

The FACT protocol and trial results have been published (NCT01355159) (20, 21). In brief, participants were randomized at 8–16 weeks of gestation into 1 of 2 groups to receive either daily 4.0 mg FA or placebo until delivery. Participants could take daily multivitamins or prenatal FA supplements containing ≤1.1 mg FA throughout the trial period. Thus, women enrolled in FACT consumed either ≤1.1 mg (low-dose) or >1.1 to ≤5.1 mg (high-dose) FA daily after randomization. The current study included Canadian FACT participants who completed both a baseline questionnaire and a NutritionQuest Block DFE FFQ (22) before randomization (8–16 weeks of gestation) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Derivation of the study cohort from FACT participants in Canada. This was a substudy of FACT. The analysis was limited to FACT participants in Canada who completed a dietary folate equivalent screener at 8–16 completed weeks of gestation. FACT, the Folic Acid Clinical Trial.

Dietary folate and FA intake and FA supplement use

Dietary folate intake was assessed through participant completion of the NutritionQuest Block DFE FFQ (www.nutritionquest.com), a semiquantitative 21-question screening tool developed from dietary recall data from the United States’ 1999–2001 NHANES, and has been validated for the estimation of usual folate intake based on self-reported data (23, 24). Calculated food-only intake includes naturally occurring food folate intake (μg/d) as well as FA intake from fortified foods (μg/d) from prespecified sources. Intake frequency is reported per food source as ≥2 times/d, every day, 1–2 times/wk, 3–4 times/wk, 5–6 times/wk, 2–3 times/mo, and once per month or less. There is no option to indicate zero intake. This FFQ has been validated in pregnant and nonpregnant women (22–24) and applied in Canadian populations (25).

Current FA supplementation (μg/d) was assessed by FACT study staff upon enrollment at 8–16 weeks of gestation. The EAR for folate is reported in DFE to account for differences in bioavailability between naturally occurring folate and FA; FA is 1.7 times more bioavailable than natural folate when taken with food (5). Where total dietary folate is presented and as it relates to the EAR, FA intake data are expressed as daily DFE intake (μg DFE/d). In contrast, the UL is based on intakes of FA only, not naturally occurring folate, and is expressed in μg FA. Therefore, total FA intake from food and/or supplements, as it relates to the UL, is reported in micrograms (5). In this study, we used dietary intake data derived from the FFQ to draw comparison to DRI values. However, the FFQ provides an estimation of the dietary intake only and cannot be used to derive absolute intake amounts (22).

Descriptive characteristics

Data on participant characteristics relevant to dietary intake and supplement use included sociodemographic information (i.e., age, gestational age at data collection, prepregnancy BMI, parity, ethnicity, marital status, level of education, employment status), health behaviors (i.e., smoking history), and presence of obstetric risk factors that rendered them eligible for enrollment into FACT (i.e., history of pre-eclampsia, chronic hypertension, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, twin pregnancy, BMI ≥35 kg/m2.

Ethical approval

FACT was approved by the Ottawa Health Science Network research ethics board (2009107-01H) and at all participating sites. All participants provided informed, written consent for enrollment in FACT and use of their data for future research.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Boxplots were produced with RStudio software, version 1.1.463 (R Core Team) (26) using the package ggplot2 (27). Descriptive statistics included n (%) for categorical variables. Continuous variables were described with medians (IQRs) and minimum and maximum values. Demographic variables were reported for the overall cohort. FA and folate intake data were reported and stratified by Canadian region, as follows: provinces were grouped as Western Canada (British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba), Ontario, Québec, and Eastern Canada (New Brunswick and Newfoundland). There were no FACT sites in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, or in the Canadian Territories.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 provides baseline participant characteristics. A total of 1198 Canadian FACT participants completed the FFQ at 8–16 completed weeks of gestation. The majority were recruited from the provinces of Ontario (n = 434, 36.2%) and Québec (n = 390, 32.6%). Remaining participants were recruited from British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland (n = 375, 31.3%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of FACT participants in Canada completing the FFQ at 8–16 completed weeks of gestation1

| Characteristics | Study participants |

|---|---|

| Total participants | 1198 (100) |

| Age, y | 32.0 [29.0–35.0] |

| Gestational age, wk | 13.6 [12.6–15.4] |

| Multiparous | 743 (62.0) |

| Twin pregnancy2 | 304 (25.4) |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 32.2 [25.1–38.8] |

| <18.5 | 18 (1.5) |

| 18.5 to <25 | 273 (22.8) |

| 25 to <30 | 231 (19.3) |

| 30 to <35 | 173 (14.4) |

| ≥352 | 503 (42.0) |

| Chronic hypertension2 | 263 (22.0) |

| Diabetes (type 1 or 2)2 | 236 (19.7) |

| History of pre-eclampsia2 | 264 (22.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 955 (79.7) |

| Black | 77 (6.4) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 22 (1.8) |

| Other | 144 (12.0) |

| Married/common law | 1089 (90.9) |

| College/university education | 761 (63.5) |

| Full-time employment | 821 (68.5) |

| Smoking history | 483 (40.3) |

| Current smoker | |

| No | 1042 (87.0) |

| Yes | 81 (6.8) |

| Quit during pregnancy | 75 (6.3) |

n = 1198. Values are n (%) or median [IQR]. FACT, the Folic Acid Clinical Trial.

Enrollment criteria for FACT (20).

The median age of participants was 32 y (IQR: 29.0–35.0 y) and prepregnancy BMI was 32.2 (IQR: 25.1–38.8). The majority were multiparous (n = 743, 62.0%). Participants were predominantly white (79.7%), employed full-time (68.5%), and had attended college/university (63.5%). Self-reported smoking was 6.8% at FACT enrollment and 6.3% had quit earlier in pregnancy. Canadian participants were enrolled into FACT at a median gestational age of 13.6 wk (IQR: 12.6–15.4 wk), based on the following obstetric risk factors: BMI ≥35 kg/m 2 (42.0%), twin pregnancy (25.4%), chronic hypertension (22.0%), a history of pre-eclampsia (22.0%), and diabetes (19.7%).

FA supplement use

Table 2 reports FA supplement use. The majority of participants (n = 1101, 91.9%) reported daily consumption of FA supplements at the time of trial randomization. Of these, 96.0% (n = 1057) consumed between 1000 and 1100 μg/d, and 0.4% (n = 5) of participants reported daily consumption below the recommended dosage for supplementation during pregnancy (400 μg/d) (11). A total of 97 (8.1%) participants were not taking any FA supplements at the time of enrollment.

TABLE 2.

FA intake from supplements among FACT participants in Canada completing the FFQ at 8–16 completed weeks of gestation1

| Overall (n = 1198) | Western Canada (n = 190) | Ontario (n = 434) | Québec (n = 390) | Eastern Canada (n = 184) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FA supplement use at randomization (8–16 weeks of gestation), μg/d | |||||

| Median [IQR] | 1000.0 [1000.0–1000.0] | 1000.0 [1000.0–1000.0] | 1000.0 [1000.0–1000.0] | 1000.0 [1000.0–1000.0] | 1000.0 [1000.0–1000.0] |

| Range (min–max) | 0.0–1100.0 | 0.0–1100.0 | 0.0–1100.0 | 0.0–1100.0 | 0.0–1100.0 |

| 0 | 97 (8.1) | 9 (4.7) | 47 (10.8) | 36 (9.2) | 5 (2.7) |

| 1–399 | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| 400–999 | 39 (3.3) | 6 (3.2) | 18 (4.1) | 7 (1.8) | 8 (4.3) |

| 1000 | 967 (80.7) | 163 (85.8) | 331 (76.3) | 304 (77.9) | 169 (91.8) |

| 1001–1100 | 90 (7.5) | 11 (5.8) | 35 (8.1) | 42 (10.8) | 2 (1.1) |

| History of high-dose FA supplement use before FACT randomization (≥1.1 mg/d) | |||||

| Not applicable | 768 (64.1) | 144 (75.8) | 285 (65.7) | 223 (57.2) | 116 (63.0) |

| 1.1–4.9 mg/d | 91 (7.6) | 18 (9.5) | 26 (6.0) | 20 (5.1) | 27 (14.7) |

| ≥5.0 mg/d | 339 (28.3) | 28 (14.7) | 123 (28.3) | 147 (37.7) | 41 (22.3) |

| How long before FACT randomization did high-dose supplementation stop? | |||||

| Not applicable | 768 (64.1) | 144 (75.8) | 285 (65.7) | 223 (57.2) | 116 (63.0) |

| <1 wk | 135 (11.3) | 16 (8.4) | 47 (10.8) | 34 (8.7) | 38 (20.7) |

| ≥1 wk | 293 (24.5) | 29 (15.3) | 101 (23.3) | 133 (34.1) | 30 (16.3) |

| Unknown | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

1Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated. Eastern Canada was defined as New Brunswick and Newfoundland, Western Canada as British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. FA, folic acid; FACT, the Folic Acid Clinical Trial.

A total of 430 (35.9%) women had previously consumed FA from supplements at total daily doses ≥1.1 mg/d (high-dose), of whom 339 (78.8%) had taken ≥5.0 mg FA/d from supplements. FA supplementation at dosages >1.1 mg/d was an exclusion criterion for FACT. Of the 430 women who had a history of using high-dose FA supplements, 135 (31.4%) had stopped high-dose FA supplementation <1 wk before FACT randomization.

Combined folate and FA intake

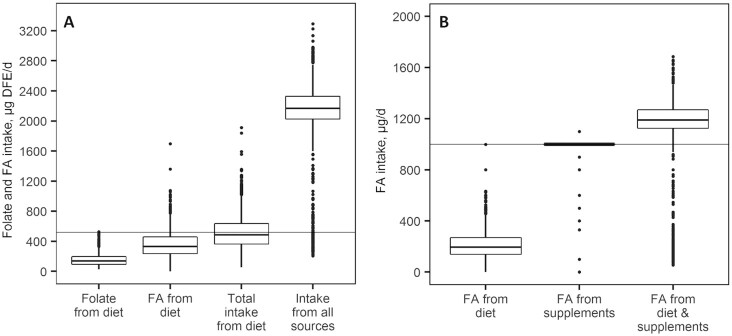

Figure 2 summarizes folate and FA intake from natural and fortified food sources and FA supplements among Canadian women at 8–16 weeks of gestation. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 provide tabular summaries.

FIGURE 2.

Folate (A) and FA (B) intake among Folic Acid Clinical Trial participants in Canada at 8–16 completed weeks of gestation (n = 1198). (A) DFE intake among study participants. Intake data are reported as folate intake from diet, FA intake from fortified foods, total folate and FA intake from diet, and total folate and FA intake from all food and supplement sources. The Estimated Average Requirement in pregnancy is indicated by a horizontal line (5). (B) FA intake among study participants. Data are presented as FA intake from fortified foods, FA intake from supplements, and total FA intake from foods and supplements. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level for FA intake is indicated by a horizontal line (5). Boxplots display the median values and IQRs. Whiskers demonstrate the highest and lowest values which are no more than 1.5 times the IQR away from the box. Points outside of the whiskers represent outliers. Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 provide corresponding tabular data, including stratification by Canadian province. DFE, dietary folate equivalents; FA, folic acid.

Participants had a median dietary intake of 140 μg DFE/d (IQR: 100–193 μg DFE/d) of natural folate and 333 μg DFE/d (IQR: 243–455 μg DFE/d) of FA from fortified foods. The median total folate (natural folate and FA) intake from all dietary sources among participants was 485 μg DFE/d (IQR: 370–630 μg DFE/d), with 520 (43.4%) women meeting the EAR for pregnant women (520 μg DFE/d) (5). The most commonly consumed food folate sources were bread products and vegetables (median intake frequencies: every day and 3–4 times/wk, respectively). Supplemental Table 3 includes participant-reported intake frequencies of all FFQ products.

With the addition of FA supplements, the median combined total folate intake from all sources increased to 2167 μg DFE/d (IQR: 2032–2325 μg DFE/d) and 1142 (95.3%) women met or exceeded the EAR (5). Participants had a median total FA intake of 1189 μg/d (IQR: 1128–1266 μg/d) from both fortified foods and supplements. A total of 1069 (89.2%) participants in our cohort met or exceeded the UL for FA (1000 μg/d) (5).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that a majority of pregnant Canadian women do not achieve sufficient folate intake from diet alone to achieve the EAR for pregnancy (5). Further, FA intake from food is insufficient for most women to achieve the 400 μg FA/d recommended by the Institute of Medicine to reduce the risk of NTDs (5). Together, these data indicate that FA supplements are indeed necessary for Canadian women, even in the context of food fortification. However, because most prenatal FA supplements in Canada contain 1000 μg FA, women who consume these supplements have FA intakes above the UL (5).

Since the introduction of mandatory FA fortification in Canada in 1998, the prevalence of NTD-affected pregnancies has decreased substantially (2, 28). Over 90% of women report taking FA supplements in the first trimester and into late pregnancy (7, 19, 29–31), and folate deficiency is virtually nonexistent among pregnant Canadian women (30, 32, 33). Not unexpectedly, 56.6% of pregnant women in our cohort did not meet the folate EAR through dietary intake alone, indicating the need for FA supplementation. In fact, supplements were the primary source of FA intake among our study participants, with 88.2% of participants taking daily supplements containing ≥1000 μg FA, an amount above that recommended for individuals at low risk of NTDs (400 μg/d) and also above the UL (5). Combined dietary and supplement intake of FA was at or above the UL in 89.2% of the women in our study. It is worth noting that 8.5% of participants in our study consumed less than the recommended 400 μg/d FA from supplements (11). Although this group constitutes a minority of our study sample, the reasons for low use or nonuse of FA supplements in the Canadian population warrant further examination.

Our findings are consistent with those of other Canadian studies (6, 7, 19). In an assessment of dietary intake and supplement use among 62 pregnant and lactating women in Ontario, 36% of participants did not achieve the EAR from dietary sources alone (6). The use of prenatal supplements was associated with higher folate intake but resulted in over two-thirds (67%) exceeding the UL for FA (1000 μg/d) (5). A survey study of 368 pregnant Ontarian women found that 85% consumed FA at or exceeding the UL through supplement use alone (7). More recently, nutritional intake from food and supplements was assessed in a cohort of 1533 pregnant women in Québec. Although dietary intake of folate from food sources was below the EAR in 70% of women in this cohort, combined dietary folate and FA intake was above the UL in 87% of participants (19).

In addition to a folate-rich diet, FA supplementation is recommended before conception and during pregnancy to prevent NTDs and, in Canada, the recommended daily dose for the typical, low-risk pregnancy is 400 μg FA/d to be consumed as part of a multivitamin (11). Individuals at moderate to high risk of an NTD-affected pregnancy by way of maternal or paternal personal/family history of NTDs or other folate-sensitive congenital anomalies, maternal comorbidities, certain medical or surgical conditions, and/or folate-inhibitory teratogenic medications are recommended to take higher daily doses (1–5 mg/d) (18). Almost all prenatal supplements marketed in Canada contain 1000 μg FA, making it difficult for women to consume the recommended 400 μg/d (11). Although the Institute of Medicine noted that FA intakes at or above the UL in women of childbearing age are unlikely to produce adverse effects (5), the long-term implications of FA intake above the UL in pregnancy for both mother and child remain unclear. In the pregnant population, use of FA supplements increases RBC folate concentrations and circulating concentrations of unmetabolized FA (30). Unmetabolized FA appears in the circulation when FA is consumed at supraphysiological doses, and is common in the obstetric population (30, 34), including in FACT participants (35). Unmetabolized FA has been hypothesized to induce adverse effects, albeit inconsistently, owing to observed associations between high-dose FA supplementation and various pregnancy and offspring outcomes in some studies (30, 34). Prenatal supplements containing 400 μg FA/d, as is currently recommended for low-risk pregnancies (11), should be sufficient to prevent folate deficiency and reduce the risk of NTDs while also minimizing the risk of FA intake above the UL (36). However, harmonization of clinical guidelines, prescribing practices, and prenatal supplement formulations in Canada has proven challenging (37).

A strength of our study is our large cohort of pregnant individuals from across the country with well-documented medical and obstetric histories. We were also able to obtain detailed folate and FA intake data from both dietary and supplement sources. Our study is not without limitations. First, the cohort population represents pregnant individuals at higher risk of developing pre-eclampsia (20), which restricts the generalizability of our findings to the whole obstetric population. Pregnancies at high risk of an NTD were excluded from our sample based on FACT enrollment criteria, thus our population also does not provide insight into the folate intake of women who meet the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada guidelines for prescription of high-dose FA (18). In addition, folate and FA intake data were collected by participant self-report. Dietary assessment methods, including FFQs, have a tendency to underreport energy intake (38). FA specific underreporting is likely further exacerbated by methods relying on label data for folate and FA content, because FA overages are well documented (39). Therefore, our data may be subject to bias, resulting in an underestimation of the proportions of women exceeding both the EAR and the UL. Although we were unable to confirm the folate status of our participants, an ancillary study of 50 Canadian FACT participants found that the median RBC total folate concentration was 2701 nmol/L at 24–26 weeks of gestation, ∼12 wk after random assignment to FACT treatment (4.0–5.1 mg/d or ≤1.1 mg/d) (35). Of note, RBC total folate concentrations were higher than those previously reported in other Canadian populations of women who were pregnant or of reproductive age, regardless of participant treatment allocation, values that reflected the relatively high doses of supplemental FA consumed by FACT participants (30, 33).

The FFQ used in this study has been validated against other measures of folate intake and status including full-length FFQs and RBC folate concentration, respectively (23, 24). However, it does not require participants to specify portion sizes and does not provide estimates for the contributions of specific foods to total folate and FA intake. Accordingly, our data were limited to frequency of intake of specific foods and estimates of total dietary intake from a selection of sources of natural food folates and FA from fortified foods. The FFQ is designed to query users on their intake of the top 60% of contributors of dietary folate in the American diet (24), therefore, the data provided in our analyses likely underestimate participants’ actual dietary intake. As such, our results likely underestimate both the proportion of participants with intake below the EAR and the proportion exceeding the UL. Also, food fortification strategies, dietary patterns of Canadians, and major folate contributors to Canadian intakes are similar but not identical to those reported in the United States, and our findings should be interpreted with this in mind. Despite these limitations, our findings demonstrating that a large proportion of Canadian women report folate intake below the EAR through diet alone, but that FA supplement use results in most women consuming FA above the UL, are consistent with observations from smaller cohorts (6, 7, 19).

In conclusion, in this large sample of pregnant Canadian women at high risk of pre-eclampsia, nearly 60% did not meet the EAR for folate in pregnancy through diet alone. However, >89% of pregnant women in our cohort had FA intakes at or above the UL through combined consumption of fortified foods and supplements. With no additional benefit associated with FA intakes beyond the UL for most women, modification of prenatal supplement formulations may be warranted to ensure women meet but do not exceed recommended FA intakes. Ideally, combined dietary and supplemental FA intake would enable the obstetric population to optimize their FA intake.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MSQM, KAM, ALJH, SWW, and MCW: designed the research; EGR, MSQM, EE, KAM, AJM, RRW, and ALJH: conducted or oversaw the conduct of the research; EGR and EE: performed the statistical analysis; EGR, MSQM, and AJM: wrote the paper; MCW: had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

Supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Foundation Grant FDN 148438 (to MCW). FACT (the Folic Acid Clinical Trial) was funded by CIHR grants 198801 and 98030.

Author disclosures: the authors report no conflicts of interest.

FACT was conceived, designed, and coordinated independently of the funding source. The funder did not act as sponsor for the trial and had no role in analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication.

Supplemental Tables 1–3 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

Abbreviations used: DFE, dietary folate equivalents; EAR, Estimated Average Requirement; FA, folic acid; FACT, the Folic Acid Clinical Trial; NTD, neural tube defect; UL, Tolerable Upper Intake Level.

Contributor Information

Elaine G Rose, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Medicine and Medical Science, University College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

Malia S Q Murphy, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Erica Erwin, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; BORN Ontario, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Katherine A Muldoon, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Alysha L J Harvey, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Ruth Rennicks White, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Newborn Care, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Amanda J MacFarlane, Nutrition Research Division, Health Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Shi Wu Wen, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Newborn Care, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Mark C Walker, OMNI Research Group, Clinical Epidemiology Program, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; BORN Ontario, Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Newborn Care, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Data Availability

The authors of this study commit to making data available upon reasonable request. Requests for access to data from FACT or substudies of FACT should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Pitkin RM. Folate and neural tube defects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:285S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Wals P, Tairou F, Van Allen MI, Uh S-H, Lowry RB, Sibbald B, Evans JA, Van den Hof MC, Zimmer P, Crowley Met al. Reduction in neural-tube defects after folic acid fortification in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MRC Vitamin Study Research Group . Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet. 1991;338:131–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imbard A, Benoist J-F, Blom HJ. Neural tube defects, folic acid and methylation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:4352–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and Choline. Dietary Reference Intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherwood KL, Houghton LA, Tarasuk V, O'Connor DL. One-third of pregnant and lactating women may not be meeting their folate requirements from diet alone based on mandated levels of folic acid fortification. J Nutr. 2006;136:2820–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masih SP, Plumptre L, Ly A, Berger H, Lausman AY, Croxford R, Kim Y-I, O'Connor DL. Pregnant Canadian women achieve recommended intakes of one-carbon nutrients through prenatal supplementation but the supplement composition, including choline, requires reconsideration. J Nutr. 2015;145:1824–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Health Canada . Prenatal nutrition guidelines for health professionals: folate. [Internet]. Ottawa (Ontario): Health Canada; 2009. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/fn-an/alt_formats/hpfb-dgpsa/pdf/pubs/folate-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Government of Canada . Regulatory impact analysis statement. [Internet]. Canada Gazette Part II. 1998;132(24):3026–40.. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/1998/1998-11-25/pdf/g2-13224.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Government of Canada . Food and drug regulations. [Internet]. Ottawa (Ontario): Government of Canada; 2019. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/C.R.C.,_c._870/FullText.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Government of Canada . Folic acid and neural tube defects. Canada.ca; 2018, Date of access: 25 Aug 2020. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/pregnancy/folic-acid.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) . Nutrition during pregnancy. [Internet]. Washington (DC): ACOG; 2018. [Cited 2019 June 10]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Nutrition-During-Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) . Update on folic acid. [Internet]. London, UK: SACN; 2017. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/637111/SACN_Update_on_folic_acid.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) . Folic acid/folate and pregnancy. [Internet]. Kingston (Australia) and Wellington (New Zealand): FSANZ; 2016. [Cited 2019 June 11], . Available from: http://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/generalissues/pregnancy/folic/Pages/default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada . Folic acid for preconception and pregnancy. [Internet]. 2009. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26334606/. [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer and Department of Reproductive Health and Research . Standards for maternal and neonatal care. [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2007. [Cited 2020 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/a91272/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 17. O'Connor DL, Evans J, Koren G. High dose folic acid supplementation - questions and answers for health professionals. [Internet]. Ottawa (Ontario): Government of Canada; 2010. [Cited 25 May, 2020]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-food-guide/resources/prenatal-nutrition/high-dose-folic-acid-supplementation.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson RD, Audibert F, Brock J-A, Carroll J, Cartier L, Gagnon A, Johnson J-A, Langlois S, Murphy-Kaulbeck L, Okun Net al. Pre-conception folic acid and multivitamin supplementation for the primary and secondary prevention of neural tube defects and other folic acid-sensitive congenital anomalies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:534–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dubois L, Diasparra M, Bédard B, Colapinto CK, Fontaine-Bisson B, Morisset A-S, Tremblay RE, Fraser WD. Adequacy of nutritional intake from food and supplements in a cohort of pregnant women in Québec, Canada: the 3D Cohort Study (Design, Develop, Discover). Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:541–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wen SW, White RR, Rybak N, Gaudet LM, Robson S, Hague W, Simms-Stewart D, Carroli G, Smith G, Fraser WDet al. Effect of high dose folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on pre-eclampsia (FACT): double blind, phase III, randomised controlled, international, multicentre trial. BMJ. 2018;362:k3478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wen SW, Champagne J, Rennicks White R, Coyle D, Fraser W, Smith G, Fergusson D, Walker MC. Effect of folic acid supplementation in pregnancy on preeclampsia: the Folic Acid Clinical Trial study. J Pregnancy. 2013:294312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. NutritionQuest . Questionnaires and screeners – assessment & analysis services. [Internet]. Berkeley (CA): NutritionQuest; 2020. [Cited 23 June, 2020]. Available from: https://nutritionquest.com/assessment/list-of-questionnaires-and-screeners/ [Google Scholar]

- 23. Owens JE, Holstege DM, Clifford AJ. Comparison of two dietary folate intake instruments and their validation by RBC folate. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:3737–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clifford AJ, Noceti EM, Block-Joy A, Block T, Block G. Erythrocyte folate and its response to folic acid supplementation is assay dependent in women. J Nutr. 2005;135:137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tam C, O'Connor D, Koren G. Circulating unmetabolized folic acid: relationship to folate status and effect of supplementation. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012:485179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ray JG, Vermeulen MJ, Boss SC, Cole DEC. Declining rate of folate insufficiency among adults following increased folic acid food fortification in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2002;93:249–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gómez MF, Field CJ, Olstad DL, Loehr S, Ramage S, McCargar LJ, Kaplan BJ, Dewey D, Bell RC, Bernier FPet al. Use of micronutrient supplements among pregnant women in Alberta: results from the Alberta Pregnancy Outcomes and Nutrition (APrON) cohort. Matern Child Nutr. 2015;11:497–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Plumptre L, Masih SP, Ly A, Aufreiter S, Sohn K-J, Croxford R, Lausman AY, Berger H, O'Connor DL, Kim Y-I. High concentrations of folate and unmetabolized folic acid in a cohort of pregnant Canadian women and umbilical cord blood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:848–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chalmers B, Dzakpasu S, Heaman M, Kaczorowski J. The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey: an overview of findings. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2008;30:217–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Houghton LA, Sherwood KL, Pawlosky R, Ito S, O'Connor DL. [6S]-5-Methyltetrahydrofolate is at least as effective as folic acid in preventing a decline in blood folate concentrations during lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:842–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Colapinto CK, O'Connor DL, Tremblay MS. Folate status of the population in the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Can Med Assoc J. 2011;183:E100–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith AD, Kim Y-I, Refsum H. Is folic acid good for everyone?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:517–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Murphy MSQ, Muldoon KA, Sheyholislami H, Behan N, Lamers Y, Rybak N, Rennicks White R, Harvey ALJ, Gaudet LM, Smith GNet al. The effects of high-dose folic acid supplementation on folate status in pregnancy: ancillary study of the Folic Acid Clinical Trial (FACT). Am J Clin Nutr. 2021; nqaa407, Available at:, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33675351/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crider KS, Qi YP, Devine O, Tinker SC, Berry RJ. Modeling the impact of folic acid fortification and supplementation on red blood cell folate concentrations and predicted neural tube defect risk in the United States: have we reached optimal prevention?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107:1027–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lamers Y, MacFarlane AJ, O'Connor DL, Fontaine-Bisson B. Periconceptional intake of folic acid among low-risk women in Canada: summary of a workshop aiming to align prenatal folic acid supplement composition with current expert guidelines. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:1357–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bailey RL, Fulgoni VL, Taylor CL, Pfeiffer CM, Thuppal SV, McCabe GP, Yetley EA. Correspondence of folate dietary intake and biomarker data. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:1336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shakur YA, Rogenstein C, Hartman-Craven B, Tarasuk V, O'Connor DL. How much folate is in Canadian fortified products 10 years after mandated fortification?. Can J Public Health. 2009;100:281–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors of this study commit to making data available upon reasonable request. Requests for access to data from FACT or substudies of FACT should be addressed to the corresponding author.