ABSTRACT

Background

Higher maternal cow-milk intake during pregnancy is associated with higher fetal growth measures and higher birth weight.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with body fat measures and cardiometabolic risk factors at the age of 10 y.

Methods

In a population-based cohort of Dutch mothers and their children (n = 2466) followed from early pregnancy onwards, we assessed maternal first-trimester milk intake (milk and milk drinks) by food-frequency questionnaire. Maternal milk intake was categorized into 0–0.9, 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses/d, with 1 glass equivalent to 150 mL milk. For children at the age of 10 y, we calculated BMI and obtained detailed measures of body and organ fat by DXA and MRI. We also measured blood pressure and lipid, insulin, and glucose concentrations. Data were analyzed using linear and logistic regression models.

Results

Compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d during their pregnancy, those whose mothers consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d had a 0.29 SD (95% CI: 0.10, 0.48) higher BMI, 0.27 SD (95% CI: 0.08, 0.47) higher fat mass, 0.26 SD (95% CI: 0.07, 0.46) higher lean mass, 0.30 SD (95% CI: 0.09, 0.50) higher android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio and 0.38 SD (95% CI: 0.09, 0.67) higher abdominal visceral fat mass. After correction for multiple comparisons, groups of maternal milk intake were not associated with pericardial fat mass index, liver fat fraction, blood pressure, or lipid, insulin, or glucose concentrations (P values >0.0125).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that maternal first-trimester milk intake is positively associated with childhood general and abdominal visceral fat mass and lean mass, but not with other cardiometabolic risk factors.

Keywords: maternal milk intake during pregnancy, childhood, body mass index, body fat, lean mass, visceral fat mass, pericardial fat mass, liver fat

Introduction

Maternal diet during pregnancy has been shown to be important for both short- and long-term offspring growth and development (1, 2). It has been suggested that differences in maternal diet may lead to adaptations in offspring organ structure and function, predisposing the offspring to later cardiometabolic disease (2, 3). Cow-milk is a common component of the Western diet, including that of pregnant women. Milk has a high bioavailability of nutrients important for a child's growth and development, including protein, fatty acids, several types of vitamins, calcium, and other minerals (4, 5). Currently, no recommendations for milk intake specific for pregnant women exist (6–8). However, research suggests that milk intake by pregnant women might be related to fetal growth (9–13). Previous studies have observed mainly positive linear associations of maternal cow-milk intake during pregnancy with birth weight, but results for birth length were less consistent (9–12). In addition, previous studies also observed positive associations of higher maternal milk intake during pregnancy with increased fetal biometry measures and estimated fetal weight from the second trimester onwards (10, 11).

The long-term offspring health effects of maternal milk intake during pregnancy remain unclear. Studies assessing these associations are scarce and show conflicting results. A study from the United Kingdom observed, among other dietary components, no association with child's height at age 7.5 y (14), whereas a study from Denmark showed that maternal milk intake of >150 mL of mainly low-fat milk tended to be associated with increased height, insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and insulin concentrations (15). It has been suggested that maternal milk intake during pregnancy may activate the nutrient-sensitive kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) in the placenta, leading to fetal overnutrition and activated mTORC1 in the fetus (16, 17). mTORC1 is involved in the regulation of cell growth and proliferation, adipogenesis, and metabolic processes (18–20). Also, overactivation of mTORC1 is related to a variety of diseases, including obesity, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and the metabolic syndrome (16, 18, 20).

Based on this background, we hypothesized that higher maternal milk intake during pregnancy may influence long-term offspring body fat distribution and cardiometabolic development. Therefore, we assessed in a population-based cohort among 2466 Dutch mothers and their children the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring body fat and cardiometabolic risk factors across their full ranges age at the age of 10 y.

Methods

Study design

This study was embedded in the Generation R Study, a prospective population-based cohort study from early pregnancy onwards performed in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (21, 22). The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, University Medical Center, Rotterdam (MEC 198.782/2001/31). Written informed consent was obtained from all mothers at enrollment in the study. The response rate at birth was 61%. Of the total of 8879 mothers prenatally included in the study, 8663 were enrolled in the first or second trimester of pregnancy. Of those, 3439 had information available on milk intake during pregnancy, were of Dutch ethnicity, and had singleton live-born children. Of these children, 2466 (72%) children participated in the follow-up measurements at the age of 10 y (Supplemental Figure 1).

Maternal milk intake during pregnancy

We assessed maternal dietary intake, including consumption of milk, once at enrollment in the study (median: 13.5 wk of gestation; 95% range: 10.8, 21.1) using a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ). The FFQ used for this study is a 293-item modified version of the semi-quantitative FFQ by Klipstein-Grobusch et al. (23) previously developed for use in an older population. Adaptations have been made for use in a general population of pregnant women (24). This FFQ is validated against three 24-h recalls and blood concentrations of B-vitamins and fatty acids among pregnant women from the general population (24). This FFQ considered food intake over the prior 3 mo, thereby covering dietary intake within the first trimester of pregnancy. The FFQ consists of 293 items structured according to meal pattern. Questions include consumption frequency, portion size, preparation method, and additions. Portion sizes were estimated by using Dutch household measures and photographs of foods showing different portion sizes (25). To calculate average daily nutritional values, we used the Dutch food-composition table 2006 (26). To obtain frequency measures of milk consumption, we summed the consumption of milk and milk drinks (e.g., chocolate milks or other flavored, sweetened milk drinks). According to the Dutch household measures, 1 glass of milk, on average, contains 150 mL milk (25). We categorized maternal milk intake into 6 categories: 0–0.9 glass/d, 1–1.9 glasses/d, 2–2.9 glasses/d, 3–3.9 glasses/d, 4–4.9 glasses/d, and ≥5 glasses/d based on data availability.

Childhood body fat mass

At the age of 10 y, we measured height (centimeters) using a Harpenden stadiometer (Holtain Limited) and weight (kilograms) using a mechanical personal scale (SECA) without shoes and heavy clothing and calculated BMI (kg/m2). We created age- and sex-adjusted SD scores (SDS) using a Dutch reference growth chart (Growth Analyzer 4.0; Dutch Growth Research Foundation) (27). We defined childhood overweight and obesity using the International Obesity Task Force cutoffs (28) and combined overweight and obesity into 1 category for further analyses. We measured total and regional body fat and lean mass (kilograms) using DXA (iDXA; General Electric–Lunar, 2008) (29). Android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio was calculated and used as a measure of waist-to-hip ratio (29). Abdominal and organ fat were measured in a subgroup by MRI, as described previously (21). Briefly, all children were scanned using a 3.0-Tesla MRI (Discovery MR750w; General Electric Healthcare). The MRI protocol included an axial 3-point Dixon sequence for fat and water separation (IDEAL IQ) for liver fat measurements. This technique also enables the generation of liver fat fraction images (30). An axial abdominal scan from the lower liver to pelvis and a coronal scan centered at the head of the femurs were also performed with a 2-point Dixon acquisition (LavaFlex). The obtained fat scans were analyzed by the Precision Image Analysis company (PIA), using the SliceOmatic (TomoVision) software package (31). Total visceral fat volume ranged from the dome of the liver to the superior part of the femoral head. Fat masses were obtained by multiplying the total volumes by the specific gravity of adipose tissue, 0.9 g/mL. Liver fat fraction was determined by defining 4 regions of interest of at least 4 cm2 in the central portion of the hepatic volume. Subsequently, the mean signal intensities were averaged to generate an overall mean liver fat fraction estimation. Pericardial fat included both epicardial and paracardial fat directly attached to the pericardium, ranging from the apex to the left ventricular outflow tract. To create measures of total fat and lean mass independent of height, we estimated the optimal adjustment by log–log regression analysis and subsequently divided total fat mass by height4 (fat mass index), abdominal visceral fat mass and pericardial fat mass by height3 (abdominal visceral fat mass index and pericardial fat mass index), and lean mass by height2 (lean mass index) (32, 33). More details are given in Supplemental Methods 1.

Childhood cardiometabolic risk factors

At 10 y of age, systolic and diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) were measured at the right brachial artery, 4 times with 1-min intervals, using the validated automatic sphygmomanometer Datascope Accutor PlusTM (34). We used the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure values from the last 3 blood pressure measurements. Nonfasting venous blood samples were obtained (22). All blood samples were stored for a maximum of 4 h at 4°C. Blood samples were transported twice daily to the laboratory facility of the regional laboratory in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (STAR-MDC), where they were centrifuged, processed, and stored within 4 h of venous puncture (22). Serum concentrations of total cholesterol (millimoles per liter), HDL cholesterol (millimoles per liter), triglycerides (millimoles per liter), and glucose concentrations (millimoles per liter) were measured using the c702 module on the Cobas 8000 analyzer. Serum concentrations of insulin (picomoles per liter) were measured using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the E411 module (Roche) (22). LDL cholesterol (millimoles per liter) was calculated using Friedewald's formula (35). There is no universally accepted definition of the metabolic syndrome in children (36). In line with previous definitions used in pediatric populations to define a childhood metabolic syndrome–like phenotype (36), we defined clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors as the presence of at least 3 of the following: abdominal visceral fat mass ≥75th percentile, systolic or diastolic blood pressure ≥75th percentile, triglycerides ≥75th percentile or HDL cholesterol ≤25th percentile, and insulin ≥75th percentile (36). As no information on waist circumference was available, we used abdominal visceral fat mass measured by MRI as a proxy.

Covariates

We assessed maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, parity, educational level, and folic acid supplementation use by questionnaire at enrollment in the study. Total energy intake and consumption of fruit, vegetables, meat, and fish were assessed by FFQ at enrollment in the study. Smoking, caffeine intake, nausea, and vomiting during pregnancy were repeatedly assessed by questionnaire. Gestational age was determined based on fetal ultrasound examinations. We obtained information on date of birth and the child's sex from midwife and hospital registries. Information on breastfeeding was obtained by questionnaire in infancy. Information on childhood milk intake was obtained by questionnaire at the age of 8 y. Average television-watching time was assessed by questionnaire at the age of 10 y.

Statistical analysis

First, we tested for differences in maternal and childhood characteristics between groups of maternal milk intake using ANOVA for continuous variables that were normally distributed, Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables that were not normally distributed, and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Second, in order to evaluate possible bias resulting from nonresponse over time, we performed a nonresponse analysis comparing mothers and children included in the analyses with those lost to follow-up at the age of 10 y using independent-samples t tests for continuous variables that were normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables that were not normally distributed, and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Third, for our main analysis we used linear regression models to examine the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with childhood body fat measures and individual cardiometabolic risk factors, comparing the children of mothers who consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. For outcomes that showed a clear linear relation, we tested whether a dose–response relation was present by adding the categorized maternal milk intake variable to the models as a continuous variable. Fourth, we used logistic regression models to examine the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with the risk of childhood overweight/obesity and the risk of clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors. The basic models were adjusted for child's sex and age at follow-up measurement. Based on existing literature, we considered as possible confounders maternal age; maternal prepregnancy BMI; parity; folic acid supplementation use; maternal smoking; maternal total energy intake; level of education; vomiting; nausea; consumption of fruit, vegetables, meat, and fish; maternal caffeine intake; and child's television watching. Of these, only maternal smoking, vomiting, and total energy intake were associated with both the exposure (maternal milk intake) and the outcomes (childhood fat measures and cardiometabolic risk factors) in our study, and changed the effect estimates for the associations between maternal milk intake and childhood fat measures or cardiometabolic risk factors by >10%. Therefore, these variables are considered confounders and are included in the models (confounder models). If associations were present, we explored whether these associations were mediated by gestational age–adjusted birth weight, breastfeeding, or childhood milk intake by adding these variables to the confounder models. Last, we performed several sensitivity analyses for our main findings: 1) we repeated the analyses for body fat measures with the highest 3 milk intake groups combined into 1 category, 2) we repeated the analyses for body fat measures excluding the milk drinks from the definition of milk intake, and 3) we assessed the associations of maternal yogurt and cheese intake with childhood body fat measures in order to examine whether the observed associations are restricted to milk intake or are also present for other dairy products. We tested for interaction between maternal milk intake and child's sex in the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with the outcomes. As a statistically significant interaction was observed in the model with pericardial fat mass index as the outcome (P < 0.05), results from this model were presented stratified by child's sex. No statistically significant interactions between maternal milk intake and child's sex were present in the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with other childhood fat mass outcomes or cardiometabolic risk factors (P > 0.05) and therefore no stratified results are reported. We log-transformed the variables for fat mass index, android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio, abdominal visceral fat mass index, pericardial fat mass index, liver fat fraction, triglycerides, and insulin, as these were not normally distributed. In order to compare effect estimates between the outcomes, we calculated SDS for all outcomes as (observed value − mean)/SD, representing the difference between the observed value and the mean of that particular variable, expressed in SDs. To account for multiple comparisons, we divided the P value of 0.05 by 4 outcome categories (body fat, blood pressure, lipids, glucose metabolism), resulting in a P value of 0.0125, which was considered statistically significant. Missing values of covariates were imputed using multiple imputation, and pooled results from 5 imputed datasets were reported. Analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 24.0 (IBM Corporation) and R statistical software version 3.3.4 (37).

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Table 1 shows that, of the 2466 women included, 663 (26.8%), 638 (25.9%), 691 (28.0%), 271 (11.0%), 95 (3.8%), and 108 (4.4%) had milk intakes of 0–0.9, 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses/d, respectively, during pregnancy. Women who had higher milk intakes smoked more often. These women also had higher total energy intakes, higher intakes of meat, and lower intakes of vegetables. Intakes of fruit and fish did not differ between milk-intake groups. Children born to mothers with higher milk intakes in pregnancy had higher milk intakes at the age of 8 y. Supplemental Table 1 shows that, as compared with women included in the analyses, those lost to follow-up were younger, more often multiparous, and more often less educated. These women also had a 0.4-glass/d higher milk intake and smoked more often during their pregnancy.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the mothers and their children1

| Maternal milk intake during pregnancy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total group (n = 2466) | 0–0.9 glass (n = 663) (26.9%) | 1–1.9 glasses (n = 638) (25.9%) | 2–2.9 glasses (n = 691) (28.0%) | 3–3.9 glasses (n = 271) (11.0%) | 4–4.9 glasses (n = 95) (3.8%) | ≥5 glasses (n = 108) (4.4%) | P | |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||||||

| Milk intake during pregnancy (milk and milk drinks),2 glasses/d | 1.6 [0.0, 5.3] | 0.4 [0.0, 0.9] | 1.2 [1.0, 1.9] | 2.6 [2.0, 2.9] | 3.4 [3.0, 3.9] | 4.6 [4.1, 5.0] | 5.4 [5.0, 7.8] | <0.001 |

| Milk intake during pregnancy (milk only),3 glasses/d | 1.3 [0.0, 5.0] | 0.2 [0.0, 0.9] | 1.0 [0.1, 1.7] | 2.5 [1.0, 2.9] | 2.9 [1.0, 3.8] | 4.5 [2.0, 5.0] | 5.0 [2.5, 7.3] | <0.001 |

| Milk intake during pregnancy (milk drinks only),4 glasses/d | 0.1 [0.0, 1.2] | 0.0 [0.0, 0.5] | 0.1 [0.0, 1.1] | 0.1 [0.0, 1.1] | 0.4 [0.0, 2.1] | 0.1 [0.0, 2.5] | 0.4 [0.0, 3.0] | <0.001 |

| Age, y | 31.9 [22.7, 39.7] | 31.9 [22.7, 39.4]a | 32.4 [23.5, 39.7]b,c | 32.0 [22.8, 39.8]d | 31.5 [22.9, 39.4] | 31.0 [20.0, 39.0]a,b,d | 31.3 [21.0, 42.7]c | <0.001 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 23.2 (3.8) | 22.8 (3.8) | 23.0 (3.7) | 23.5 (3.9) | 23.3 (4.1) | 23.6 (4.0) | 23.4 (3.5) | 0.058 |

| Education,5n (%) | NA | |||||||

| Primary | 38 (1.6) | 11 (1.7) | 7 (1.1) | 10 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (2.1) | 5 (4.6) | |

| Secondary | 842 (34.6) | 214 (32.6) | 193 (30.4) | 243 (35.8) | 96 (36.2) | 39 (41.1) | 57 (52.8) | |

| Higher | 1556 (63.9) | 431 (65.7) | 434 (68.5) | 425 (62.7) | 166 (62.6) | 54 (56.8) | 46 (42.6) | |

| Nulliparous, n (%) | 1540 (62.6) | 429 (65.0) | 417 (65.4) | 401 (58.0) | 163 (60.1) | 63 (66.3) | 67 (62.6) | 0.049 |

| Folic acid supplementation use, n (%) | 1850 (91.5) | 495 (91.8) | 493 (93.2) | 513 (90.8) | 194 (89.8) | 74 (93.7) | 81 (87.1) | 0.306 |

| Smoking during pregnancy, n (%) | 290 (12.7) | 68 (11.0)a | 64 (11.0)b | 85 (13.4) | 38 (15.5) | 19 (21.6)a,b | 16 (15.4) | 0.032 |

| Total energy intake,6 kcal/d | 2127 [1227, 3174] | 1929 [1138, 3038] | 2069 [1285, 3153] | 2181 [1305, 3122] | 2384 [1497, 3208] | 2430 [1627, 3466] | 2562 [1529, 3252] | <0.001 |

| Caffeine intake during pregnancy,7 units/d | 1.9 [0.0, 5.5] | 1.8 [0.0, 5.0]a | 2.0 [0.0, 5.8]a | 2.0 [0.0, 5.5] | 1.9 [0.1, 5.3] | 2.0 [0.1, 5.3] | 2.0 [0.0, 5.1] | 0.022 |

| Fruit intake, g/d | 190 [21, 473] | 189 [23, 472] | 190 [18, 476] | 189 [19, 454] | 192 [31, 472] | 178 [22, 515] | 206 [24, 517] | 0.493 |

| Vegetable intake, g/d | 149 [54, 304] | 152 [53, 303] | 156 [54, 305]a | 145 [55, 281]a | 142 [66, 331] | 150 [50, 307] | 140 [44, 304] | 0.012 |

| Meat intake, g/d | 83 [1,166] | 78 [1, 165]a,b | 78 [0, 166]c,d | 89 [1, 158]a,d | 83 [1, 172] | 99 [1, 168]b,c | 88 [9, 159] | <0.001 |

| Fish intake, g/d | 12 [0, 45] | 12 [0, 42] | 12 [0, 51] | 11 [0, 39] | 12 [0, 46] | 12 [0, 42] | 11 [0, 32] | 0.191 |

| Yogurt intake, g/d | 75 [0, 375] | 75 [0, 396] | 75 [0, 375]a | 64 [0, 375]d | 75 [0, 375]b | 64 [0, 375]a,b,c | 86 [0, 454]c,d | <0.001 |

| Cheese intake, g/d | 41 [1,153] | 40 [1,163] | 40 [3,161] | 42 [0,147] | 44 [3,162] | 44 [1.8,121.5] | 41 [1,147] | 0.415 |

| Daily vomiting,65n (%) | 93 (4.1) | 30 (4.9) | 16 (2.8) | 30 (4.8) | 4 (1.7) | 5 (5.7) | 8 (7.9) | NA |

| Daily nausea, n (%) | 619 (27.5) | 170 (27.7) | 137 (23.5)a,b | 185 (29.6)a | 62 (25.8) | 32 (36.8)b | 33 (32.4) | 0.045 |

| Child characteristics | ||||||||

| Males, n (%) | 1225 (49.7) | 317 (47.8) | 306 (48) | 363 (52.5) | 144 (53.1) | 46 (48.4) | 49 (45.4) | 0.298 |

| Gestational age at birth, wk | 40.3 [36, 42.4] | 40.3 [36.1, 42.4] | 40.3 [35.7, 42.6] | 40.3 [36.1, 42.1] | 40.3 [36.5, 42.3] | 40.0 [34.7, 42.3] | 40.0 [37.0, 42.2] | 0.099 |

| Birth weight, g | 3530 [2335, 4500] | 3500 [2382, 4450]a | 3550 [2259, 4441] | 3530 [2370, 4615] | 3600 [2536, 4462]a | 3400 [1850, 4454] | 3565 [2518, 4448] | 0.017 |

| Gestational age–adjusted birth weight, SD | 0.0 (1.0) | −0.1 (1.0)a,b | 0.1 (1.0)b | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.0)a | 0.0 (0.9) | 0.1 (1.0) | 0.013 |

| Ever breastfeeding, n (%) | 1985 (91.9) | 538 (91) | 535 (92.7) | 554 (92.5) | 204 (90.7) | 73 (89.0) | 81 (95.3) | 0.535 |

| Milk intake, glasses/d | 1.2 [0.0, 3.9] | 0.9 [0.0, 3.8]a,b,c,d,e | 1.2 [0.0, 3.9]a | 1.3 [0.0, 3.7]b | 1.4 [0.0, 3.8]c | 1.8 [0.0, 6.2]d | 1.4 [0.0, 4.9]e | <0.001 |

| Age at follow-up measurement, y | 9.7 [9.3, 10.5] | 9.7 [9.3, 10.5] | 9.7 [9.3, 10.5] | 9.7 [9.3, 10.4] | 9.7 [9.3, 10.4] | 9.7 [9.2, 10.4] | 9.7 [9.5, 10.5] | 0.872 |

| Television watching >2 h/d, n (%) | 613 (26.6) | 160 (25.8) | 152 (25.6) | 181 (27.9) | 73 (29) | 18 (21.2) | 29 (28.4) | 0.660 |

| Body composition | ||||||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 16.6 [14.0, 22.5] | 16.3 [14.1, 21.8] | 16.8 [13.9, 22.2] | 16.7 [14.1, 23] | 16.7 [14.0, 22.2] | 16.9 [14.3, 23.1] | 17.1 [14, 23.6] | 0.038 |

| Total body fat mass, kg | 8.1 [4.5, 19] | 7.8 [4.4, 18] | 8.3 [4.4, 18] | 8.0 [4.5, 20] | 8.2 [4.6, 18] | 8.1 [4.5, 18] | 8.6 [4.7, 20] | 0.172 |

| Android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio | 0.2 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.2 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.2 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.2 [0.2, 0.5] | 0.2 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.2 [0.2, 0.4] | 0.3 [0.2, 0.5] | 0.234 |

| Lean mass, kg | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.084 |

| Abdominal visceral fat mass, kg | 0.4 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.4 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.4 [0.2, 0.8] | 0.4 [0.2, 1] | 0.4 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.4 [0.2, 0.9] | 0.4 [0.2, 1] | 0.222 |

| Pericardial fat mass, g | 10.9 [4.9, 22.6] | 10.7 [5.1, 22.2] | 11.1 [4.8, 23.0] | 10.9 [4.7, 22.0] | 10.6 [4.7, 23.6] | 10.2 [5.2, 20.1] | 11.9 [7.1, 24.9] | 0.394 |

| Liver fat fraction, % | 2.0 [1.2, 4.5] | 2.0 [1.2, 4.0] | 2.0 [1.2, 4.2] | 2.0 [1.2, 5.4] | 1.9 [1.2, 4.1] | 2.1 [1.5, 5.3] | 1.9 [1.2, 5.0] | 0.415 |

| Blood pressure | ||||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 103 (8) | 102 (8) | 102 (8) | 103 (8) | 103 (8) | 103 (9) | 104 (7) | 0.311 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 58 (6) | 58 (7) | 58 (6) | 58 (7) | 58 (7) | 58 (7) | 59 (6) | 0.369 |

| Serum biochemistry | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 0.992 |

| LDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.996 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.0 [0.40, 2.5] | 0.9 [0.40, 2.6] | 1.0 [0.40, 2.5] | 1.0 [0.40, 2.4] | 1.0 [0.40, 2.2] | 1.0 [0.50, 3.3] | 1.0 [0.40, 2.2] | 0.908 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.5 (0.30) | 1.5 (0.30) | 1.5 (0.30) | 1.5 (0.30) | 1.5 (0.40) | 1.5 (0.30) | 1.5 (0.30) | 0.962 |

| Insulin, pmol/L | 167 [34.8, 540] | 171 [35.4, 537] | 178 [32.0, 581] | 161 [34.0, 514] | 160 [41.5, 491] | 184 [32.2, 504] | 173 [39.4, 692] | 0.157 |

| Glucose, nmol/L | 200 (136) | 204 (136) | 214 (148) | 188 (129) | 187 (116) | 197 (126) | 205 (152) | 0.297 |

Values are means (SDs), medians [95% range], or number of participants (valid %) unless otherwise indicated. Milk-intake categories labeled with a common letter differ, P < 0.05. NA, not applicable.

All milk-intake categories differ, P < 0.05, except for 3–3.9 glasses vs 4–4.9 glasses and 4–4.9 glasses vs ≥5 glasses.

All milk-intake categories differ, P < 0.05, except for 4–4.9 glasses vs ≥5 glasses.

All milk-intake categories differ, P < 0.05, except for 1–1.9 glasses vs 4–4.9 glasses, 2–2.9 glasses vs 4–4.9 glasses, and 3–3.9 glasses vs ≥5 glasses.

NA: no chi-square test possible due to low expected cell counts (cell counts <5).

All-milk intake categories differ, P < 0.05, except for 3–3.9 glasses vs 4–4.9 glasses, 3–3.9 glasses vs ≥5 glasses, and 4–4.9 glasses vs ≥5 glasses.

1 unit is equivalent to 1 cup of coffee (90 mg caffeine).

Childhood body fat measures

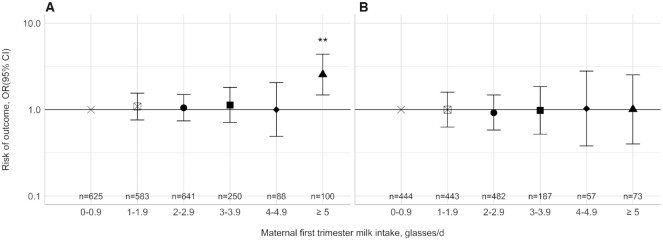

Table 2 shows that, as compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d during their pregnancy, those whose mothers consumed ≥5 glasses/d had a higher BMI (difference: 0.29 SD; 95% CI: 0.10, 0.48), fat mass index (difference: 0.27 SD; 95% CI: 0.08, 0.47), lean mass index (difference: 0.26 SD; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.46), android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio (difference: 0.30 SD; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.50), and abdominal visceral fat mass index (difference: 0.38 SD; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.67). Children whose mothers consumed 4–4.9 glasses of milk/d, but not those whose mothers consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d, had a higher liver fat fraction [differences: 0.33 SD (95% CI: 0.02, 0.63) and 0.16 SD (95% CI: −0.11, 0.44) for 4–4.9 glasses and ≥5 glasses, respectively]. Dose–response relations were present for the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with BMI, fat mass index, android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio (P < 0.05). Most of the observed associations remained present after correction for multiple comparisons (P < 0.0125; Table 2). Table 3 shows that higher maternal milk intakes tended to be associated with a lower pericardial fat mass index in boys, and with a higher pericardial fat mass in girls. After correction for multiple comparisons, only maternal milk intake of ≥5 glasses/d remained associated with a higher pericardial fat mass in girls (difference: 0.65 SD; 95% CI: 0.22, 1.07; compared with 0–0.9 glass/d). Results from the basic models were similar (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). The observed associations were not explained by additional adjustment for gestational age–adjusted birth weight, breastfeeding, or child's milk intake (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). Results were similar for sensitivity analyses excluding the milk drinks or combining the highest 3 milk categories (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7). Sensitivity analyses with first-trimester cheese and yogurt intake showed that cheese and milk intake tended to be associated with lower childhood fat masses (Supplemental Tables 8 and 9). Figure 1A shows that, compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d during their pregnancy, those whose mothers consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d had an increased risk of childhood overweight/obesity (OR: 2.55; 95% CI: 1.48, 4.39). Results from the basic models were similar (Supplemental Figure 2A).

TABLE 2.

Associations of maternal first-trimester milk intake with childhood fat and lean mass at the age of 10 y1

| Maternal milk intake | BMI (n = 2461) | Fat mass index (n = 2433) | Lean mass index (n = 2443) | Android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio (n = 2436) | Abdominal visceral fat mass index (n = 1238) | Liver fat fraction (n = 1386) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | |

| 0–0.9 glass | Reference | 662 | Reference | 651 | Reference | 651 | Reference | 652 | Reference | 339 | Reference | 380 |

| 1–1.9 glasses | 0.11 (0.01, 0.21)* | 637 | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.19) | 631 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.16) | 631 | 0.09 (−0.02, 0.20) | 632 | 0.00 (−0.15, 0.15) | 330 | −0.01 (−0.15, 0.13) | 368 |

| 2–2.9 glasses | 0.13 (0.03, 0.23)** | 691 | 0.12 (0.02, 0.22)* | 687 | 0.06 (−0.04, 0.16) | 687 | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.18) | 687 | 0.07 (−0.08, 0.22) | 336 | 0.09 (−0.05, 0.23) | 379 |

| 3–3.9 glasses | 0.13 (−0.01, 0.26) | 269 | 0.12 (−0.02, 0.26) | 265 | 0.05 (−0.09, 0.18) | 265 | 0.08 (−0.07, 0.22) | 266 | 0.00 (−0.20, 0.20) | 140 | 0.02 (−0.17, 0.22) | 152 |

| 4–4.9 glasses | 0.17 (−0.03, 0.37) | 94 | 0.29 (0.08, 0.49)** | 93 | −0.06 (−0.26, 0.15) | 93 | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.33) | 93 | 0.06 (−0.27, 0.39) | 40 | 0.33 (0.02, 0.63)* | 47 |

| ≥5 glasses | 0.29 (0.10, 0.48)** | 108 | 0.27 (0.08, 0.47)** | 106 | 0.26 (0.07, 0.46)** | 106 | 0.30 (0.09, 0.50)** | 106 | 0.38 (0.09, 0.67)** | 53 | 0.16 (−0.11, 0.44) | 60 |

| P-trend2 | 0.001** | <0.001** | NA | 0.015* | NA | NA | ||||||

Values are differences in childhood outcomes in SDs (95% CI) between children whose mothers consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, compared with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. One glass is equivalent to 150 mL milk. The models were adjusted for child's sex, child's age at follow-up measurement, maternal smoking, maternal vomiting, and maternal total energy intake. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0125 (Bonferroni-corrected P value).

P values for trend were obtained from models in which the categorized milk-intake variable was entered as a continuous variable. NA, not applicable (secondary analysis not performed as results from primary analysis are not linear).

TABLE 3.

Associations of maternal first-trimester milk intake with childhood pericardial fat at the age of 10 y1

| Pericardial fat mass index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total group (n = 1269) | Boys (n = 626) | Girls (n = 643) | ||||

| Maternal milk intake | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n |

| 0–0.9 glass | Reference | 346 | Reference | 165 | Reference | 181 |

| 1–1.9 glasses | 0.00 (−0.15, 0.15) | 336 | −0.23 (−0.45, −0.01)* | 160 | 0.19 (−0.01, 0.40) | 176 |

| 2–2.9 glasses | 0.02 (−0.13, 0.17) | 356 | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.11) | 191 | 0.11 (−0.10, 0.32) | 165 |

| 3–3.9 glasses | −0.04 (−0.24, 0.17) | 140 | −0.33 (−0.63, −0.04)* | 70 | 0.24 (−0.04, 0.52) | 70 |

| 4–4.9 glasses | 0.05 (−0.28, 0.39) | 39 | −0.66 (−1.25, −0.06)* | 12 | 0.41 (0.01, 0.81)* | 27 |

| ≥5 glasses | 0.29 (0.00, 0.59) | 52 | −0.06 (−0.47, 0.35) | 28 | 0.65 (0.22, 1.07)** | 24 |

| P-trend2 | NA | NA | 0.003** | |||

Values are differences in childhood outcomes in SDs (95% CI) between children whose mothers consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, compared with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. One glass is equivalent to 150 mL milk. The models were adjusted for child's sex, child's age at follow-up measurement, maternal smoking, maternal vomiting, and maternal total energy intake. P value for interaction < 0.001. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0125 (Bonferroni-corrected P value).

P values for trend were obtained from models in which the categorized milk-intake variable was entered as a continuous variable. NA, not applicable (secondary analysis not performed as results from primary analysis are not linear).

FIGURE 1.

Associations of maternal first-trimester milk intake with the risk of childhood overweight/obesity and clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors at the age of 10 y. Values are ORs (95% CI) that reflect the risk of overweight/obesity (A) or clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors (B) in children whose mothers consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, compared with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. One glass is equivalent to 150 mL milk. The models were adjusted for child's sex, child's age at follow-up measurement, maternal smoking, maternal vomiting, and maternal total energy intake. **P < 0.0125 (Bonferroni-corrected P value).

Childhood cardiometabolic risk factors

Table 4 shows that, compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d, those whose mothers consumed ≥5 glasses of milk had higher systolic and diastolic blood pressures [differences: 0.24 SD (95% CI: 0.03, 0.44) and 0.24 SD (95% CI: 0.03, 0.45), respectively]. These associations did not persist after correction for multiple comparisons (P > 0.0125). Table 5 shows that maternal milk intake during pregnancy was not associated with childhood lipid, insulin, or glucose concentrations (P > 0.05). Results from the basic models were similar (Supplemental Tables 10 and 11). Maternal milk intake during pregnancy was not associated with the risk of clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors (P > 0.05; Figure 1B). Results from the basic models were similar (Supplemental Figure 2B).

TABLE 4.

Associations of maternal first-trimester milk intake with childhood blood pressure at the age of 10 y1

| Systolic blood pressure (n = 2379) | Diastolic blood pressure (n = 2379) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal milk intake | Values | n | Values | n |

| 0–0.9 glass | Reference | 635 | Reference | 635 |

| 1–1.9 glasses | 0.04 (−0.07, 0.15) | 616 | 0.04 (−0.08, 0.15) | 616 |

| 2–2.9 glasses | 0.08 (−0.03, 0.19) | 667 | 0.10 (−0.01, 0.21) | 667 |

| 3–3.9 glasses | 0.11 (−0.04, 0.26) | 263 | 0.09 (−0.06, 0.23) | 263 |

| 4–4.9 glasses | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.34) | 92 | 0.05 (−0.17, 0.27) | 92 |

| ≥5 glasses | 0.24 (0.03, 0.44)* | 106 | 0.24 (0.03, 0.45)* | 106 |

| P-trend2 | 0.011** | 0.024* | ||

Values are differences in childhood outcomes in SDs (95% CI) between children whose mothers consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, compared with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. One glass is equivalent to 150 mL milk. The models were adjusted for child's sex, child's age at follow-up measurement, maternal smoking, maternal vomiting, and maternal total energy intake. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.0125 (Bonferroni-corrected P value).

P values for trend were obtained from models in which the categorized milk-intake variable was entered as continuous variable.

TABLE 5.

Associations of maternal first-trimester milk intake with childhood metabolic outcomes at the age of 10 y1

| Total cholesterol (n = 1718) | HDL cholesterol (n = 1705) | LDL cholesterol (n = 1698) | Triglycerides (n = 1701) | Insulin (n = 1703) | Glucose (n = 1704) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal milk intake | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n | Values | n |

| 0–0.9 glass | Reference | 488 | Reference | 447 | Reference | 445 | Reference | 446 | Reference | 477 | Reference | 477 |

| 1–1.9 glasses | −0.01 (−0.14, 0.12) | 452 | −0.05 (−0.18, 0.08) | 453 | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.13) | 449 | 0.09 (−0.04, 0.23) | 450 | 0.05 (−0.08, 0.18) | 451 | 0.05 (−0.08, 0.18) | 453 |

| 2–2.9 glasses | −0.03 (−0.15, 0.10) | 486 | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.06) | 487 | 0.00 (−0.13, 0.13) | 486 | 0.10 (−0.03, 0.23) | 487 | −0.10 (−0.23, 0.03) | 487 | 0.06 (−0.07, 0.19) | 487 |

| 3–3.9 glasses | 0.01 (−0.17, 0.18) | 188 | −0.04 (−0.21, 0.14) | 188 | 0.04 (−0.13, 0.22) | 188 | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.23) | 188 | −0.05 (−0.23, 0.12) | 188 | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.23) | 188 |

| 4–4.9 glasses | 0.00 (−0.28, 0.28) | 57 | 0.01 (−0.28, 0.29) | 57 | −0.07 (−0.34, 0.21) | 57 | 0.16 (−0.12, 0.44) | 57 | −0.03 (−0.31, 0.25) | 57 | 0.24 (−0.04, 0.52) | 57 |

| ≥5 glasses | −0.02 (−0.27, 0.23) | 73 | −0.05 (−0.30, 0.20) | 73 | 0.02 (−0.23, 0.27) | 73 | 0.05 (−0.20, 0.30) | 73 | 0.01 (−0.24, 0.26) | 73 | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.11) | 72 |

Values are differences in childhood outcomes in SDs (95% CI) between children whose mothers consumed 1–1.9, 2–2.9, 3–3.9, 4–4.9, and ≥5 glasses of milk/d, respectively, compared with those whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. One glass is equivalent to 150 mL milk. The models were adjusted for child's sex, child's age at follow-up measurement, maternal smoking, maternal vomiting, and maternal total energy intake.

Discussion

In this population-based prospective cohort study, high maternal milk intake during pregnancy was associated with a higher childhood general and abdominal visceral fat mass, a higher lean mass, and a higher risk of overweight/obesity at the age of 10 y. Maternal milk intake during pregnancy was not associated with childhood blood pressure, metabolic outcomes, or cardiometabolic risk factor clustering.

Interpretation of main findings

Results from previous studies, including one from the same cohort as the current study, strongly suggest that maternal milk intake during pregnancy is associated with high offspring birth weight (9–12). Thus far, it is unclear whether maternal milk intake during pregnancy also affects long-term offspring body composition. Only 2 studies assessed the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring growth and body composition. In a study from the United Kingdom among 6663 mothers and children, maternal milk intake in late pregnancy was not associated with height in 7.5-y-old children (14). In a study among 685 mothers and children from Denmark, maternal milk intake in late pregnancy was not associated with offspring BMI at age 20 y (15). In contrast, we observed that a milk intake of ≥5 glasses/d was associated with a higher childhood BMI, fat mass index, android-to-gynoid fat mass ratio, and a higher risk of overweight/obesity at the age of 10 y. Dose–response relations were present for most of these outcomes. Although the models used were similar, the different results of the current study compared with those of previous studies might be attributed to differences in definition of milk intake, fat contents of the milk, or timing of assessment of maternal milk consumption. In the Danish study, milk intake was defined as the total intake of whole, semi-skimmed, skimmed, and cultured milk. Participants from the Danish study mainly consumed low-fat milk (15). The UK study did not report on the definition of milk intake or fat contents (14). In our study, milk intake was defined as the consumption of milk or milk drinks, which may be (sugar-) sweetened. As results from the sensitivity analyses excluding milk drinks were similar to those with milk drinks included, we consider it unlikely that added sugars are an important contributor to the associations observed. Unfortunately, we do not have information available on fat contents of the milk consumed in our study, limiting comparison with the previous studies. Both previous studies assessed milk intake in late pregnancy, whereas milk intake in our study was assessed in early pregnancy. The same adverse exposure might have different effects depending on the stage of development of fetal organ systems (38, 39). Our results may suggest that early pregnancy is a more important period with respect to the effects of maternal milk intake on offspring body composition. Maternal milk intake of ≥5 glasses of milk/d was also associated with a higher lean mass index, but no associations were present for lower milk intakes and no dose–response relation was present. This might suggest that a high milk intake might affect both fat and lean body mass, although being more pronounced for fat mass. Children of mothers with high maternal milk intake during pregnancy also had higher organ-specific fat masses, including abdominal visceral fat and liver fat. In addition, maternal milk intake was associated with lower pericardial fat mass in boys, but with higher pericardial fat mass in girls. In adults it has been shown that men have higher pericardial fat masses than women, but that correlations of pericardial fat with cardiometabolic risk factors are higher in women than in men (40). Although not much is known on sex differences specifically for childhood pericardial fat mass development, these observed differences in associations between boys and girls might be attributed to differences in timing or location of fat deposition throughout childhood (41, 42). Future studies should confirm these findings. In this study, we observed differences in childhood fat measures of ∼0.3 SD for children of mothers who consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d during their pregnancy. These effect estimates are of comparable size to those for well-known determinants of childhood adiposity, including maternal prepregnancy BMI and smoking during pregnancy (43–45). Thus, our results suggest that high maternal milk intake during pregnancy seems to be associated with childhood body composition.

In addition to effects on body composition, it has been suggested that milk consumption might also influence blood pressure and metabolism (17, 20). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with childhood blood pressure. We observed higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure in children of mothers who consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–0.9 glass of milk/d. However, these effect estimates were not statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons. Further studies are needed to assess whether maternal milk intake during pregnancy is associated with blood pressure in childhood. Thus far, only 1 study among 685 mothers and their 20-y-old children assessed the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring metabolic outcomes, and observed higher insulin and IGF-I concentrations in children of mothers with milk intakes of ≥150–600 mL/d during their pregnancy compared with children whose mothers consumed 0–150 mL/d (15). In our current study, we did not observe associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with blood concentrations of lipids, insulin, or glucose or cardiometabolic risk factor clustering at the age of 10 y. However, the children in our study were 10 y younger than those in the study from Denmark. It might be that associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring metabolic risk factors appear at later ages. Thus, maternal milk intake during pregnancy does not seem to be associated with offspring cardiometabolic risk factors in childhood.

The mechanisms underlying the observed associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring body composition are not yet known. Translational research has suggested that milk intake by pregnant women increases concentrations of insulin, IGF-I, growth hormone, amino acids, particularly the branched-chain amino acids, and fatty acids in maternal blood, which might subsequently lead to activation of the nutrient-sensitive kinase mTORC1 in the placenta. mTORC1 is involved in the regulation of cell growth and adipogenesis (18–20). In addition, overactivation of mTORC1 is associated with several cardiometabolic diseases, including obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes (16, 18, 20). Activation of mTORC1 in the placenta might result in increased placental transfer of amino acids and glucose and subsequent fetal overnutrition, causing fetal mTORC overactivation and stimulation of anabolic processes, cell growth, and adipogenesis (16, 17). Also, milk contains microRNAs that might cause epigenetic upregulation of genes that are involved in the development of cardiometabolic diseases, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes (46). These microRNAs are not present in fermented milk products (46), which might explain the different associations of maternal cheese and yogurt intake in our study. In our study, milk intake was defined as the consumption of milk or milk drinks, which may be (sugar-)sweetened. As results from the sensitivity analyses excluding milk drinks were similar to those with milk drinks included, we consider it unlikely that added sugars are an important contributor to the associations assessed. It has been suggested that the protein in milk might be an important contributor to growth and development. However, previous studies from the same cohort showed that maternal protein intake during pregnancy was not associated with offspring body fat or blood pressure at the age of 6 y (47, 48). Therefore, we consider it unlikely that the protein content of milk is a major contributor to the observed associations. Further research is needed to disentangle the mechanisms linking maternal milk intake during pregnancy with adverse offspring body composition. Alternatively, the associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with offspring body mass might be explained by confounding by unhealthy lifestyle factors that are shared within families. Socioeconomic and lifestyle factors associated with offspring body composition and cardiometabolic risk in previous research (49–52), such as maternal age, level of education, parity, smoking during pregnancy, and caffeine intake during pregnancy, differed between milk-intake groups. Also, children of mothers with higher milk intakes also had higher milk intakes at age 8 y, which might be explained by shared lifestyles between mother and child. Although some of these factors were not associated with the outcomes in our current study and, for those that were, adjustment for these possible factors did not influence the effect estimates, we cannot completely exclude that our results are influenced by shared lifestyle.

No recommendations specific for pregnant women exist. In the Netherlands, it is recommended that women of reproductive age consume 2–3 glasses (equivalent to 300–450 mL/d) of skimmed or semi-skimmed milk products daily, but there are no recommendations with respect to maximum intakes (6). These recommendations do not include sugar-sweetened milk products and cheeses. Recommendations for most European countries and the United States are similar to those for the Netherlands, although it should be noted that some differences including products and portion size exist (7, 8). Our results suggest that high maternal milk intakes of ≥5 glasses/d might have adverse effects for offspring body fat development. In our study population, 4.4% of participants consumed ≥5 glasses of milk/d. However, it should be noted that the Netherlands is among the countries with the highest milk consumption globally (>300 kg milk equivalents per capita), along with some other European countries (53), and that our results are most relevant for those countries that have high milk consumption. We did not observe associations of maternal milk intake during pregnancy with cardiometabolic risk factors. However, as excess body fat, and especially excess ectopic fat, is an important predictor of the development of later cardiometabolic disease (54, 55), we speculate that it might still be possible that children of mothers with high milk intakes are at risk of these diseases in adulthood. Replication of our results in other studies and populations and evidence from randomized controlled trials are needed before conclusions can be drawn on whether high milk intake during pregnancy is safe with respect to long-term offspring cardiometabolic health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Our study is embedded in a large population-based cohort study that follows pregnant women and their children from early pregnancy until young adulthood, which enabled us to prospectively study the associations of interest. Of all participants with available information on maternal milk intake during pregnancy, 28.3% did not participate in the follow-up measurements at the age of 10 y. This nonresponse might have led to biased effect estimates if the associations of interest differ between those included and not included in the analyses. As only a small difference in maternal milk intake of 0.4 glass was observed between these groups, we consider this unlikely. Compared with the general population of Rotterdam (56), the population for analysis was highly educated, which might have affected the generalizability of the results. Information about maternal milk intake during pregnancy is based on self-report and we assumed that milk is consumed in glasses of 150 mL. However, this might have differed between participants and might subsequently have led to some misclassification of milk intake and either under- or overestimation of the effect estimates. The blood samples were nonfasting and taken during nonfixed times of the day. This may have led to nondifferential misclassification, resulting in an underestimation of the effect sizes for insulin and glucose concentrations. In addition, since no universally accepted definition of the metabolic syndrome in pediatric populations exists (36), there is a potential for nondifferential misclassification of clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors, which might have led to an underestimation of the effect estimates. We were able to adjust our models for many possible confounders. However, residual confounding by unmeasured factors—for example, maternal physical activity—might still be present. Last, it should be noted that, due to the observational design of the study, we are not able to draw conclusions on the causality of the observed associations.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that maternal first-trimester milk intake is positively associated with childhood general and abdominal visceral fat mass and lean mass but not with other cardiometabolic risk factors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Generation R Study is conducted by the Erasmus Medical Center in close collaboration with the School of Law and Faculty of Social Sciences of the Erasmus University Rotterdam; the Municipal Health Service Rotterdam area, Rotterdam; the Rotterdam Homecare Foundation, Rotterdam; and the Stichting Trombosedienst and Artsenlaboratorium Rijnmond (STAR), Rotterdam. The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—EV, RG, and VWVJ: designed and conducted the research and wrote the manuscript; EV: performed the statistical analysis; VWVJ: coordinated data acquisition; MLG: critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; EV and VWVJ: had primary responsibility for the final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Notes

The Generation R Study is financially supported by the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Erasmus University Rotterdam, and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. VWVJ received a European Research Council Consolidator Grant (ERC-2014-CoG-648916). RG received funding from the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant number 2017T013), the Dutch Diabetes Foundation (grant number 2017.81.002), and the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW; grant number 543003109).

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental Tables 1–11, Supplemental Figures 1 and 2, and Supplemental Methods 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/jn/.

Abbreviations used: FFQ, food-frequency questionnaire; IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor I; mTORC1, mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1; SDS, SD score.

Contributor Information

Ellis Voerman, The Generation R Study Group, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pediatrics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Romy Gaillard, The Generation R Study Group, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pediatrics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Madelon L Geurtsen, The Generation R Study Group, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pediatrics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Vincent W V Jaddoe, The Generation R Study Group, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Department of Pediatrics, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- 1. Mousa A, Naqash A, Lim S. Macronutrient and micronutrient intake during pregnancy: an overview of recent evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11;443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Koletzko B, Godfrey KM, Poston L, Szajewska H, van Goudoever JB, de Waard M, Brands B, Grivell RM, Deussen AR, Dodd JMet al. Nutrition during pregnancy, lactation and early childhood and its implications for maternal and long-term child health: the Early Nutrition Project recommendations. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;74:93–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pereira PC. Milk nutritional composition and its role in human health. Nutrition. 2014;30:619–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willett WC, Ludwig DS. Milk and health. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:644–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stichting Voedingscentrum Nederland . Richtlijnen Schijf van Vijf. Den; Haag (Netherlands):Stichting Voedingscentrum Nederland; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Department of Agriculture . All about the dairy group. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 10]. Available from: https://www.choosemyplate.gov/eathealthy/dairy. [Google Scholar]

- 8. EU Joint Research Centre . Food-based dietary guidelines in Europe. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 10]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/health-knowledge-gateway/promotion-prevention/nutrition/food-based-dietary-guidelines#_Toctb7. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Olsen SF, Halldorsson TI, Willett WC, Knudsen VK, Gillman MW, Mikkelsen TB, Olsen J, Consortium N. Milk consumption during pregnancy is associated with increased infant size at birth: prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heppe DH, van Dam RM, Willemsen SP, den Breeijen H, Raat H, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Maternal milk consumption, fetal growth, and the risks of neonatal complications: the Generation R Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borazjani F, Angali KA, Kulkarni SS. Milk and protein intake by pregnant women affects growth of foetus. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31:435–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brantsaeter AL, Olafsdottir AS, Forsum E, Olsen SF, Thorsdottir I. Does milk and dairy consumption during pregnancy influence fetal growth and infant birthweight? A systematic literature review. Food Nutr Res. 2012;56, 20050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Achón M, Úbeda N, García-González Á, Partearroyo T, Varela-Moreiras G. Effects of milk and dairy product consumption on pregnancy and lactation outcomes: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S74–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leary S, Ness A, Emmett P, Davey Smith G, ALSPAC Study Team. Maternal diet in pregnancy and offspring height, sitting height, and leg length. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:467–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hrolfsdottir L, Rytter D, Hammer Bech B, Brink Henriksen T, Danielsen I, Steingrimsdottir L, Olsen SF, Halldorsson TI. Maternal milk consumption, birth size and adult height of offspring: a prospective cohort study with 20 years of follow-up. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:1036–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Melnik BC, John SM, Schmitz G. Milk is not just food but most likely a genetic transfection system activating mTORC1 signaling for postnatal growth. Nutr J. 2013;12:103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melnik BC, John SM, Schmitz G. Milk consumption during pregnancy increases birth weight, a risk factor for the development of diseases of civilization. J Transl Med. 2015;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Das A, Reis F, Maejima Y, Cai Z, Ren J. mTOR signaling in cardiometabolic disease, cancer, and aging. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:6018675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laplante M, Sabatini DM. An emerging role of mTOR in lipid biosynthesis. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R1046–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM, Duijts L, Franco OH, van IMH, de Jongste JC, Klaver CC, van der Lugt A, Mackenbach JPet al. The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:1243–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kruithof CJ, Kooijman MN, van Duijn CM, Franco OH, de Jongste JC, Klaver CC, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Raat H, Rings EHet al. The Generation R Study: Biobank update 2015. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29:911–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Klipstein-Grobusch K, den Breeijen JH, Goldbohm RA, Geleijnse JM, Hofman A, Grobbee DE, Witteman JC. Dietary assessment in the elderly: validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1998;52:588–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Voortman T, Steegers-Theunissen RPM, Bergen NE, Jaddoe VWV, Looman CWN, Kiefte-de Jong JC, Schalekamp-Timmermans S. Validation of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire for Dutch pregnant women from the general population using the method or triads. Nutrients. 2020;12;1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Donders-Engels MR, van der Heijden L, Hulshof KF. Maten, Gewichten en Codenummers [Weights, measures and code numbers]. Wageningen (Netherlands): Vakgroep Humane Voeding, Landbouwuniversiteit Wageningen en TNO Voeding Zeist; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Netherlands Nutrition Centre . Nevo: Dutch Food Composition Database 2006. The Hague (Netherlands): Stichting Nederlands Voedingsstoffenbestand; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fredriks AM, van Buuren S, Burgmeijer RJ, Meulmeester JF, Beuker RJ, Brugman E, Roede MJ, Verloove-Vanhorick SP, Wit JM. Continuing positive secular growth change in The Netherlands 1955–1997. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:316–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Helba M, Binkovitz LA. Pediatric body composition analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;34:729–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hu HH, Nayak KS, Goran MI. Assessment of abdominal adipose tissue and organ fat content by magnetic resonance imaging. Obes Rev. 2011;12:e504–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. VanItallie TB, Yang MU, Heymsfield SB, Funk RC, Boileau RA. Height-normalized indices of the body's fat-free mass and fat mass: potentially useful indicators of nutritional status. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:953–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wells JC, Cole TJ, steam AS. Adjustment of fat-free mass and fat mass for height in children aged 8 y. Int J Obes. 2002;26:947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wong SN, Tz Sung RY, Leung LC. Validation of three oscillometric blood pressure devices against auscultatory mercury sphygmomanometer in children. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:281–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steinberger J, Daniels SR, Eckel RH, Hayman L, Lustig RH, McCrindle B, Mietus-Snyder MLAmerican Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nutrition; et al. ; American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular NutritionProgress and challenges in metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Atherosclerosis, Hypertension, and Obesity in the Young Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2009;119:628–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Langley-Evans SC. Developmental programming of health and disease. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cameron N, Demerath EW. Critical periods in human growth and their relationship to diseases of aging. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;119:159–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gill CM, Azevedo DC, Oliveira AL, Martinez-Salazar EL, Torriani M, Bredella MA. Sex differences in pericardial adipose tissue assessed by PET/CT and association with cardiometabolic risk. Acta Radiol. 2018;59:1203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fuente-Martin E, Argente-Arizon P, Ros P, Argente J, Chowen JA. Sex differences in adipose tissue: it is not only a question of quantity and distribution. Adipocyte. 2013;2:128–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karastergiou K, Smith SR, Greenberg AS, Fried SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues—the biology of pear shape. Biol Sex Dif. 2012;3:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Voerman E, Santos S, Patro Golab B, Amiano P, Ballester F, Barros H, Bergström A, Charles MA, Chatzi L, Chevrier Cet al. Maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the risk of overweight and obesity across childhood: an individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16:e1002744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riedel C, Fenske N, Müller MJ, Plachta-Danielzik S, Keil T, Grabenhenrich L, von Kries R. Differences in BMI z-scores between offspring of smoking and nonsmoking mothers: a longitudinal study of German children from birth through 14 years of age. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grzeskowiak LE, Hodyl NA, Stark MJ, Morrison JL, Clifton VL. Association of early and late maternal smoking during pregnancy with offspring body mass index at 4 to 5 years of age. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2015;6:485–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Melnik BC, Schmitz G. Milk's role as an epigenetic regulator in health and disease. Diseases. 2017;5;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tielemans MJ, Steegers EAP, Voortman T, Jaddoe VWV, Rivadeneira F, Franco OH, Kiefte-de Jong JC. Protein intake during pregnancy and offspring body composition at 6 years: the Generation R Study. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56:2151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. van den Hil LC, Rob Taal H, de Jonge LL, Heppe DH, Steegers EA, Hofman A, van der Heijden AJ, Jaddoe VW. Maternal first-trimester dietary intake and childhood blood pressure: the Generation R Study. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:1454–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gaillard R, Rurangirwa AA, Williams MA, Hofman A, Mackenbach JP, Franco OH, Steegers EA, Jaddoe VW. Maternal parity, fetal and childhood growth, and cardiometabolic risk factors. Hypertension. 2014;64:266–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Durmuş B, Heppe DH, Taal HR, Manniesing R, Raat H, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Gaillard R, Jaddoe VW. Parental smoking during pregnancy and total and abdominal fat distribution in school-age children: the Generation R Study. Int J Obes. 2014;38:966–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ruiz M, Goldblatt P, Morrison J, Porta D, Forastiere F, Hryhorczuk D, Antipkin Y, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Lioret S, Vrijheid Met al. Impact of low maternal education on early childhood overweight and obesity in Europe. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2016;30:274–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Voerman E, Jaddoe VW, Hulst ME, Oei EH, Gaillard R. Associations of maternal caffeine intake during pregnancy with abdominal and liver fat deposition in childhood. Pediatric Obesity. 2020;15:e12607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations . Global dairy sector: status and trends. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Mar 5]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/i1522e/i1522e02.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Britton KA, Fox CS. Ectopic fat depots and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;124:e837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Pou KM, Maurovich-Horvat P, Liu CY, Vasan RS, Murabito JM, Meigs JB, Cupples LAet al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Verhulst FC, Witteman JC, Hofman A. The Generation R Study: design and cohort profile. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:475–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.