Abstract

The present study mainly focused on college students amidst the COVID-19 outbreak and aimed to develop and examine a moderated mediation model between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. Friendship quality as a moderator, and perceived stress as a mediator. A sample of 1032 college students participated in this study and completed questionnaires regarding access to epidemic information, perceived stress, friendship quality, and life satisfaction. Findings indicated that 1) access to epidemic information was strongly related to life satisfaction; 2) perceived stress acts as a mediator in the positive relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction; 3) friendship quality moderated the relationship between access to epidemic information and perceived stress as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction, and such that there was a stronger association between access to epidemic information and perceived stress for college students with high friendship quality. But the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction became weaker for college students with high friendship quality. The results illuminate the mechanism to theoretical and practical implications for improving college students’ life satisfaction during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Access to epidemic information, Life satisfaction, Perceived stress, Friendship quality

Introduction

Life satisfaction refers to a stable and general cognitive evaluation of an individual’s overall living conditions or major aspects of life (Huebner, 2004). It is one of the most important themes reflecting college students’ positive life attitude in facing the difficulties that have received more attention in the field of mental health research. Moreover, life satisfaction is not only an evaluation of the individual’s current state but also impacts the individual’s future psychological state (Proctor et al., 2009). As longitudinal studies show, higher life satisfaction can positively predict individuals’ future behavior and mental state, while lower life satisfaction can predict depression and mental dysfunction (Geng, Xu, et al., 2020a; King & Dela Rosa, 2019). Goal setting and planning for the future may still stay in the stage of thinking and constant adjustment, and life satisfaction is extremely unstable among college students (Karatzias et al., 2013). Any event related to them may directly or indirectly affect their life satisfaction (Karatzias et al., 2013). The sudden emergence of novel coronavirus pneumonia has caused a series of global public health crises. And it is defined as an “international public health emergency” by the World Health Organization (WHO 2020), which has aroused great public concern. As a traumatic life event, COVID-19 not only changes people’s lifestyle (such as quarantined at home, wearing masks for a long time and the excessive use of disinfectants, etc.) but also leads to physical and mental health problems, thereby may have an impact on people’s life satisfaction. Therefore, it is necessary to explore the contributing factors that impact people’s life satisfaction under the stress of unexpected public health events. It is crucial to help people improve their life satisfaction with theoretical and practical implications.

Access to Epidemic Information and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is an important parameter to measure the personal quality of life and an indicator of subjective well-being (Huebner et al., 1998; Wang & Zhang, 2012). During the pandemic, for most Chinese people understanding the latest developments of the epidemic has become a vital part of life. Today, with the development of the Internet, information about the epidemic is regularly updated and omnipresent. Access to epidemic information refers to the activities and processes of obtaining useful information through certain means and methods within a certain range around a certain goal. People will feel relieved when they collect and select valuable information from the massive information, which buffers the discomfort caused by traumatic events and improves life satisfaction.

Previous studies found that life events (Mccullough et al., 2000), sense of control (Andrew & Meeks, 2016; Han & Wu, 2018), perceived stress (Burger & Samuel, 2017; Qi et al., 2014), and so on are the influencing factors of life satisfaction, which can affect the individual’s life satisfaction to a certain extent. However, a recent study found a significant correlation between access to health information and life satisfaction and showed that access to health information can help people maintain their physical and mental health (Kugbey et al., 2019). Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, access to epidemic information is particularly important to public life in China. For them, the more information about the epidemic situation (such as the number of people cured, the relevant measures that are taken by the government, etc.) is obtained, the more certain they are about the safety of their environment, and they have more clear plans and arrangements for their own lives, which highly increases their life satisfaction. However, once individuals feel that they cannot access epidemic information timely and accurately, it will increase their risk awareness and produce a series of negative emotions such as fear and perceived stress, which will harm life satisfaction (Liu et al., 2012). But it remains unknown how access to epidemic information improves life satisfaction of Chinese college students. So, it is necessary to pay attention to college students’ access to epidemic information and life satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress in the Relationship between Access to Epidemic Information and Life Satisfaction

The potential psychological mechanism of access to epidemic information affecting life satisfaction needs to be further explored, and perceived stress may play a mediating role in the process of access to epidemic information affecting life satisfaction. In the era of network communication, to make individual judgments and decisions as accurate as possible. People always try to find the most comprehensive information. However, due to a large number of repeated and false information, college students need to spend more energy and time identifying, which undoubtedly increases the pressure on college students’ information search and selection (Zheng, 2005). Especially during the epidemic, access to epidemic information has become a necessity in their lives (Jiao et al., 2020). For the college students who are affected by the epidemic situation, access to more epidemic information (such as the number of people cured, the government taking relevant measures, etc.) can reduce their perceived stress, because the access to more information can increase their confidence in overcoming the virus and can more positively look at the difficulties they are facing, and even make it possible for them to make a clear life and study plan(Tran et al., 2020; Valizadeh-Haghi et al., 2021). Perceived stress is an individual’s subjective perception of internal and external pressure events, which can not only change people’s cognitive function but also affect people’s emotions and physiological state (Lazarus & Folkman, 1986). Various stimulating events and adverse factors in life (such as the outbreak of an epidemic and information cannot be obtained timely and accurately) will bring psychological confusion, threat, or challenge to the individual. These puzzles or challenges will lead to the individual’s perceived stress, which represents the individual’s tension or out-of-control state (Yang & Huang, 2003).

According to Arnold’s “Assessment-Excitement”, individuals will awaken their entire physical activity and negative emotions after a perceived analysis of stressful events in the cerebral cortex and a negative evaluation (such as fear) (Cotton, 2010), which will reduce their life satisfaction. Therefore, as a risk factor, perceived stress is an important factor affecting life satisfaction (Wang & Gan, 2010). And a large number of studies have also shown that there is a significant negative relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction (Liao et al., 2015; Wiernik et al., 2013; Yang & Huang, 2003).

If individuals can’t get the epidemic information in time, they perceive pressure which will lead to the decline of life satisfaction. So, perceived stress may act as a mediator in the positive relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. The outbreak of Covid-19 has seriously threatened people’s lives and life, so people need to obtain effective information. Wang (2017) shows that the improvement of information effectiveness can relieve information anxiety and psychological stress of college students. Bawden and Robinson (2009) showed that when individuals are unable to obtain, understand or use information, and their quality of life will be affected because individuals perceive psychological pressure during the process of acquiring information. Hartog (2017) also showed that people’s psychological pressure is caused by the uncertainty of information, and he also pointed out that complex information tasks and information disorganization are easy for users to generate information anxiety and psychological stress. However, chronic perceived stress is a significant factor in the decline in life satisfaction (Burger & Samuel, 2017; Zheng et al., 2019). Kiesswetter et al. (2020) found that the higher an individual’s perceived stress, the lower his life satisfaction. Matheny et al. (2002) found that individuals with high-pressure perception could not handle problems brought about by stressful situations well, so the level of their life satisfaction was low. Therefore, this study expands on previous research and proposes a hypothesis of the mediating effect of perceived stress: perceived stress mediates the process of college students’ access to epidemic information positively affecting life satisfaction.

The Moderating Role of Friendship Quality

Friendship quality is an important index to measure friendships, which reflects the level of support, company, and conflict between friends (Van Schalkwyk et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). Access to epidemic information may have an impact on life satisfaction through the mediating role of perceived stress, but this is not true of all individuals, so the process by which access to epidemic information affects life satisfaction may be moderated by other factors. Adolescents are in a critical period of close contact with their peers. During the epidemic, peer friendships can provide important information that is not available to the individual or to the family, which is of great significance to the individual’s psychological and behavioral development (Corsano et al., 2017). Therefore, friendship quality may play a moderating role in the process of how access to epidemic information affects life satisfaction. As a common protective factor, friendship quality can moderate the impact of risk factors on individual psychology and behavior. The buffer effect model of social support regulating mental health holds that when individuals suffer from stressful events, and social support can make individuals get more positive emotions and reduce the perceived stress, negative emotions, and physiological reactions, which will promote people’s mental health (Wang, Zhang, & Tan, 2020a). A good friendship is beneficial in offering social support for dealing with psychological distress and solving problems (Ho et al., 2021; Kim, 2020; Markovic & Bowker, 2017). College students are increasingly dependent on the support of close friends (Kim & In-soo, 2019). According to the buffering model of stress, social or personal resources, as a protective factor, will play a buffer role in the process of pressure acting on individual physical and mental health (Laborde et al., 2011). Individuals with positive resources will adapt well no matter what degree of stress they perceive (Laborde et al., 2011). High-quality friendship provides the most important social-emotional support for college students (Ling et al., 2021; Terry et al., 2019). College students may have psychological pressure when they have emotional problems due to life events, and high-quality friendship becomes the buffer for teenagers to resist perceived stress (Kingery & Marshall, 2011), which helps to improve life satisfaction.

During the period of the COVID-19 outbreak, good friendships can make it easier to access epidemic information and reduce perceived pressure and improve life satisfaction. On the one hand, college students who have a high-quality friendship can get the epidemic information through the help of friends to alleviate the psychological impact brought by information failure. On the other hand, college students who have a high-quality friendship can talk to good friends to reduce negative emotions and stress. However, the negative emotions are easy to be generated and difficult to be released if the individual fails to acquire information on time, which leads to an increase in the individual’s fear and pressure on the surrounding and the level of individual life satisfaction will be reduced. It can be seen that friendship quality can be used as an effective protective factor to reduce the harm of perceived stress on life satisfaction. So, this study intends to explore that friendship quality may play a moderating role in the relationship between access to epidemic information and college students’ perceived stress as well as between perceived stress and life satisfaction.

The Present Study

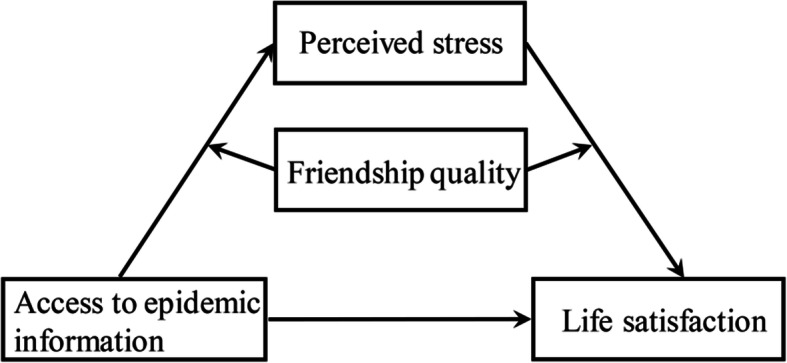

The current study attempted to establish how perceived stress helped explain the process by which access to epidemic information was correlated with life satisfaction and the specific relationships among the factors. Besides, the role of friendship quality was assessed to test whether friendship quality would moderate the association between access to epidemic information and perceived stress as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction (Fig. 1). Consequently, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Access to epidemic information will be positively correlated with life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2. Perceived stress will mediate the relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3. Friendship quality will moderate the association between perceived stress and access to epidemic information as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction.

Fig. 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model

Method

Participants

The study questionnaire was distributed to 1032 college students in China (Mage = 19.50, SD = 1.65, range = 18–24, 57.6% Female). The study questionnaire was distributed to potential participants electronically via Survey Star (Changsha Ranxing Science and Technology, Shanghai, China) and was entirely contact-free. All participants consented to participation and all data were anonymized. Furthermore, 31.2% of these participants were 1st year standing, 28.2% were 2nd year standing, 17.3% were 3rd year standing, and 23.3% were 4th year standing.

Measures

Access to Epidemic Information

Access to epidemic information was compiled based on the Risk Information Questionnaire (Shi et al., 2003). This scale consists of twenty items (e. g. “I am aware of the number of the COVID-19 being diagnosed each day”) and includes four dimensions: coronavirus disease information (ten items), cure information (two items), personal related information (three items) and the government’s precautions (five items). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of access to epidemic information. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.92. The validity information of access to epidemic information was CFI =0.971, TLI =0.963, RMSEA = 0.065, SRMR = 0.039.

Perceived Stress

Perceived stress was measured by the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al., 1983); Chinese version revised by Yang and Huang (2003). This scale consists of fourteen items (e.g., “Getting upset when something unexpected happens”) and includes two dimensions: nervous feeling (seven items) and out of control (seven items). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. The Chinese version of the Perceived Stress Scale has been demonstrated to be reliable (Li & Ma, 2019). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.82.

Friendship Quality

Friendship quality was measured by the Friendship Quality Scale (Parker & Asher 1993); Chinese version revised by Zou et al. (1998). This scale consists of eighteen items (e.g., “We always sit together whenever we have a chance”) and includes five dimensions: including trust and support (three items), companionship and entertainment (three items), certainly worth (three items), intimate disclosure and communication (four items) and conflict and betrayal (five items). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of friendship quality. The Chinese version of Friendship Quality Scale has been demonstrated to be reliable (Wang, Zhang, Tan, & Lin, 2020b). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.89.

Life Satisfaction Scale

Life satisfaction was measured by the Life Satisfaction Scale (Diener et al., 1985; Chinese version revised by Xiong & Xu, 2009), which consists of five items (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to ideal”). Participants rated their life satisfaction on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). Higher total scores indicating higher levels of life satisfaction. The Chinese version of Life satisfaction Scale has been demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measurement in assessing life satisfaction among the Chinese (Chang et al., 2017; Kong et al., 2014; Kong & You, 2013). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.89.

Procedures

This investigation was approved by the first author’s University Ethics Committee. All study participants over the age of majority provided informed consent. For participants under the age of majority, consent of their legal guardian was obtained. All participants were informed of the importance of the authenticity and completeness of their answers and were reassured that their responses would not be linked to their identities. The anonymity of the study was emphasized before data collection. Participants were then directed to an anonymous survey in which they completed the measures listed above.

Data Analysis

First, data screening revealed that there were no outliers in our data, and responses with missing data (e.g., gender not reported) were excluded from the data processing. Then analyze the mediation model, the steps are as follows. First, descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were calculated among the study variables. Second, the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 4) was applied to examine the mediating effect of perceived stress (Hayes, 2013). Third, the PROCESS macro (Model 58) was applied to examine the moderating effect of friendship quality on the indirect links between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. The bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs) determine whether the effects in Model 4 and Model 58 are significantly based on 5000 random samples (Hayes, 2013). An effect is regarded as significant if the CIs do not include zero. All study variables were standardized in Model 4 and Model 58 before data analyses.

Result

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics for all variables, including the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations between access to epidemic information, perceived stress, friendship quality, and life satisfaction were presented in Table 1. Perceived stress was negatively correlated with access to epidemic information (r = −0.27, p < .001) and life satisfaction (r = −0.53, p < .001). Additionally, access to epidemic information was positively correlated with life satisfaction (r = 0.26, p < .001). Hypothesis 1 was supported. Moreover, friendship quality was related positively to the access to epidemic information (r = 0.34, p < .001) and life satisfaction (r = 0.38, p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables of interest

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| API | 3.57 | 0.54 | 1 | |||

| Perceive stress | 2.59 | 0.42 | −0.27*** | 1 | ||

| Life satisfaction | 4.58 | 1.15 | 0.26*** | −0.53*** | 1 | |

| Friendship quality | 3.70 | 0.54 | 0.34*** | −0.41*** | 0.38*** | 1 |

Note. N = 1032. API = Access to Epidemic Information. *p < 0.05.**p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Testing for Mediation Effect

In Hypothesis 2, we assumed that perceived stress would mediate the relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. This hypothesis was tested with Model 4 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). As Table 2 showed, access to epidemic information was negatively related to perceived stress (β = −0.27, t = −9.08, p < 0.001), and the negative direct association between life satisfaction and perceived stress remained significant (β = −0.50, t = −18.46, p < 0.001). The positive direct association between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction remained significant (β = 0.12, t = 4.53, p < 0.001). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported. Perceived stress acts as a mediator in the positive relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction (indirect effect = 0.136, SE = 0.021, 95% CI = [0.096, 0.179]). The indirect effect was 0.135. The effect size of the mediation effect in this paper was Pm = (ab)/c = [−0.27× (−0.50)]/0.26 = 0.519.

Table 2.

Testing the mediation effect of access to epidemic information on life satisfaction

| predictors | model1(LS) | model2(PS) | model3(LS) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |

| API | 0.26(c) | 8.61*** | (0.20,0.32) | −0.27(a) | −9.08*** | (−0.33, −0.21) | 0.12(c’) | 4.53*** | (0.07,0.18) |

| PS | −0.50(b) | −18.46*** | (−0.55, −0.45) | ||||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.3 | ||||||

| F | 74.19*** | 82.40*** | 219.73*** | ||||||

Note. N = 1032. Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. API = Access to Epidemic Information. PS = Perceived Stress. LS = Life Satisfaction. The beta values are standardized coefficients; thus, they can be compared to determine the relative strength of different variables in the model. *p < 0.05.**p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

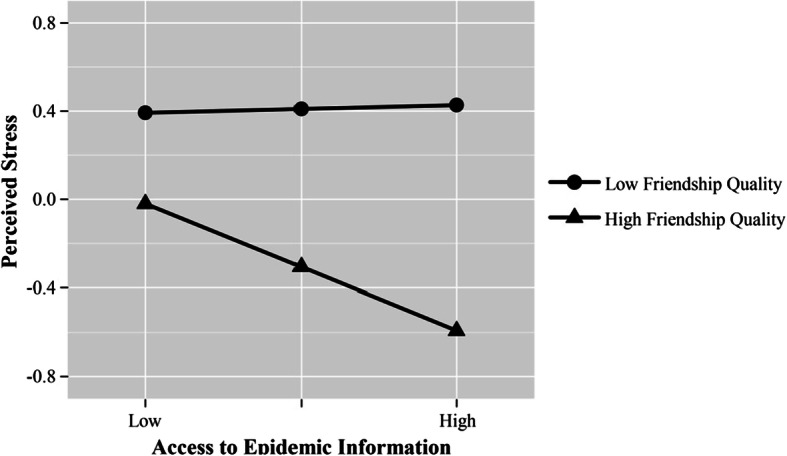

To test the moderated mediation model, we used Model 58 of the SPSS macro-PROCESS compiled by Hayes (2013). The results of the friendship quality moderation test were shown in Table 3. As shown in Model 1 of Table 3, the product (interaction term) of access to epidemic information and friendship quality had a significant predictive effect on perceived stress (β = −0.15, t = −6.44, p < 0.001). The interaction effects was 0.033. For descriptive purposes, we plotted explored perceived stress against access to epidemic information, separately for low and high levels of friendship quality (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Testing the moderated mediation effects of access to epidemic information on life satisfaction

| predictors | model1(Perceived stress) | model2(Life satisfaction) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | t | 95% CI | Β | t | 95% CI | |

| API | −0.13 | −4.57*** | (−0.19, −0.08) | 0.09 | 3.1*** | (0.03,0.14) |

| FQ | −0.36 | −12.18*** | (−0.42, −0.30) | 0.17 | 5.78*** | (0.11,0.23) |

| API×FQ | −0.15 | −6.44*** | (−0.20, −0.11) | |||

| PS | −0.47 | −15.48*** | (−0.53, −0.41) | |||

| PS×FQ | 0.05 | 2.38* | (0.01,0.09) | |||

| R2 | 0.22 | 0.33 | ||||

| F | 95.65*** | 123.92*** | ||||

Note. N = 1032. Each column is a regression model that predicts the criterion at the top of the column. API = Access to Epidemic Information. PS = Perceived Stress. LS = Life Satisfaction. FQ = Friendship Quality. The beta values are standardized coefficients; thus, they can be compared to determine the relative strength of different variables in the model. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001

Fig. 2.

Interaction between access to epidemic information and friendship quality on perceived stress

Simple slope tests showed that for college students with high friendship quality, access to epidemic information was significantly associated with perceived stress, bsimple = −0.29, p < 0.001. However, for college students with low friendship quality, access to epidemic information was not significantly associated with perceived stress, bsimple = 0.02, p = 0.661.

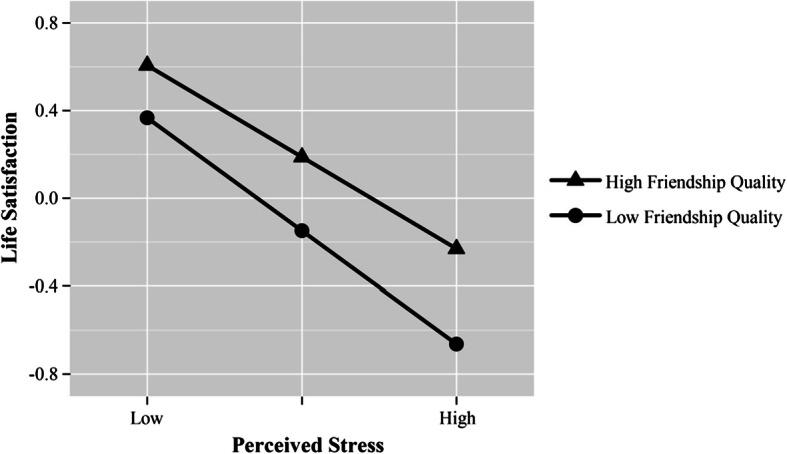

Moreover, model 2 of Table 3 showed that the product (interaction term) of perceived stress and friendship quality had a significant predictive effect on life satisfaction (β = 0.05, t = 2.38, p < 0.001). The interaction effects was 0.014. For the descriptive purpose, we plotted predicted perceived stress against life satisfaction, separately for low and high levels of friendship quality (Fig. 3). Simple slope tests showed that perceived stress significantly predicted life satisfaction in high-level friendship quality and low-level friendship quality, but the predictive function of perceived stress on life satisfaction was stronger for college students with low levels of friendship quality (bsimple = −0.51, p < 0.001) than for college students with high levels of friendship quality (bsimple = −0.42, p < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Interaction between perceived stress and friendship quality on life satisfaction

The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap analyses further showed that the indirect effect of access to epidemic information on life satisfaction via perceived stress was moderated by friendship quality. Specially, for college students with high friendship quality, the indirect relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction was significant, b = 0.112, SE = 0.023, 95% CI = [0.077, 0.166]. For college students with low friendship quality, the indirect relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction was not significant, b = −0.009, SE = 0.026, 95% CI = [−0.062, 0.041]. In sum, these results indicated that friendship quality moderated indirect associations between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction via perceived stress. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Discussion

This research examined whether there is a positive effect of access to epidemic information on college students’ life satisfaction and whether perceived stress has a mediating role as well as whether friendship quality has a moderating role. That’s consistent with our hypothesis. Our findings further contributed to the literature by testing a moderated mediation model, showing that perceived stress acts as a mediator in the positive relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. Moreover, the relationship between access to epidemic information and perceived stress as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction was further moderated by friendship quality. The results helped to understand the psychological processes of how access to more epidemic information may prevent the decrease of life satisfaction of college students and had critical implications for improving college students’ life satisfaction.

The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress

The present study is the first to demonstrate the mediating role of perceived stress in the association between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction. That is, access to epidemic information was negatively related to one’s perceived stress, which in turn, was negatively related to the development of life satisfaction. Therefore, perceived stress is not only an outcome of access to epidemic information but also a catalyst for life satisfaction. Furthermore, it is worth noting that perceived stress acts as a mediator in the positive relationship between access to epidemic information and life satisfaction, suggesting that the remaining direct effect of access to epidemic information remained a prominent factor in predicting college students’ life satisfaction.

In addition to the overall mediation result, each of the separate links in our mediation model is noteworthy. For the first step of the mediation process (i.e., access to epidemic information➔perceived stress), the present study found that access to epidemic information was negatively related to one’s perceived stress. This negative relationship may be due to the outbreak of COVID-19, which leads to the public’s strong demand for information on epidemics. As a public health emergency of international concern, COVID-19 is easy to cause a huge threat to the safety of public life and property, which arouses a strong public demand for access to epidemic information and generates perceived stress (Schmidt et al., 2021). As people who are affected by the pandemic focusing more on accessing epidemic information, they will perceive stress when they find the useful information insufficient, such as incomplete information (Guere, 2021). From another perspective, the public is highly concerned about the major public health emergencies, which shows the need to further understand the relevant progress of the event. Individuals use various media channels to obtain information to satisfy their need for control over their lives. After access to more information, they can have a comprehensive understanding of the development of the epidemic and a clear understanding of the preventive measures, which ultimately alleviate the individual’s perceived stress caused by the epidemic (Geng, Gu, et al., 2020b). Thus, the more information available about the epidemic, the lower the public’s perceived stress. For the second path of the mediation model (i.e., perceived stress ➔life satisfaction), the present study found that perceived stress was negatively related to life satisfaction. The outbreak of COVID-19 and the series of rapid social changes brought about by the epidemic likely challenged students’ ability to cope with perceived stress (Limcaoco et al., 2020; Pedrozo-Pupo et al., 2020). For students with low-stress tolerance, negative emotions and thoughts may be pervasive obstacles in maintaining normative daily functioning (Li et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2016). In other words, the higher the individual’s perceived stress, the lower their life satisfaction.

With the outbreak of the COVID-19, information about the epidemic is everywhere. So, collecting useful information (such as the number of people cured or deaths, anti-epidemic measures, etc.) becomes the key to understanding an individual’s living environment. Especially for people in other countries where the epidemic is still very severe, such as the United States, access to information about the epidemic is even more important. Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, when college students do not have access to epidemic information, they will feel overwhelmed about the safety of their surroundings as well as their future lives and generate a series of self-repression and tension. This potential hazard is a serious threat to the study and life of contemporary young college students. Studies have shown that groups with obvious symptoms of stress often search and browse a large amount of epidemic information frequently and eagerly to ease their fear and anxiety about the epidemic (Wang & Ma, 2020). However, their anxiety and perceived stress about access to information are more prominent when they get little useful information. As a risk factor in life, perceived stress will make individuals more likely to fall into an anxiety state such as tension or loss of control. However, an individual’s strong anxiety state may seriously affect their life order and life satisfaction. Research among students in Turkey showed that students’ psychological pressure during the pandemic was at high risk. Moreover, research among students in Turkey also revealed that satisfaction with life was low before and during the pandemic and decreased during the pandemic (Aslan et al., 2020). Thus, during the pandemic, the greater the individual’s perceived stress, the lower the life satisfaction.

The Moderating Role of Friendship Quality

Results also showed that friendship quality moderated the relation between access to epidemic information and perceived stress as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction. Especially, the relation between access to epidemic information and perceived stress was stronger for college students with high friendship quality. But the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction was weaker for college students with high friendship quality. Adolescents increasingly rely on their peers, especially on close friends, for companionship, intimacy, and support (Buhrmester & Furman, 1987; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). According to Sullivan’s theory of interpersonal relationship development (Sullivan, 1953), friendship plays a potentially important role in individual development under unfavorable circumstances. Therefore, the students with low friendship quality may be left to face obstacles, difficulties, and challenges alone. With the COVID-19 outbreak forcing many to shelter at home and they can’t see their peers for a long time, a weak friendship may also fail in providing social support. Thus, compared with individuals with high friendship quality, these individuals with low friendship quality and access to little epidemic information will increase their internal fear and perceived stress. Indeed, as evidenced in this study, the negative relationship between access to information and perceived stress was more significant for strong friendship qualities. According to Fig. 2 in the article, it can be seen that for people with high friendship quality, their perceived stress dropped sharply as access to information about the epidemic increased. The possible reason for this is that, on the one hand, individuals with high friendship quality broaden their sources of information and help them to get more effective information. Therefore, as individuals acquire more information, their perceived stress will gradually decrease (Dubow et al., 1991; Sahler et al., 2013). On the other hand, those who have high-quality friendships can have better positive evaluations and judgments on the epidemic through emotional interaction and social support with their friends, which also led to a decrease in perceived stress as more useful information increased (Abdollahi et al., 2018; Lakey & Heller, 1988). But for people with low friendship quality, perceived stress does not decrease with the more epidemic information they obtain. This may be because individuals with low friendship quality are inherently prone to anxiety. Such individuals already have high levels of perceived stress in normal life, so their perceived stress is at a high level even after an outbreak of COVID-19. Therefore, for people with low friendship quality, perceived stress does not decrease with the more epidemic information they obtain during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Many studies have also confirmed that friendship is the most important social support during adolescence and plays a crucial role in an individual’s emotional adaptation (Gaertner et al., 2010; Ling et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2015). In the second half path of this moderated mediation model, it is shown that friendship quality has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between college students’ perceived stress and life satisfaction, that is, compared with college students with high friendship quality, college students with low friendship quality may be more likely to be dissatisfied with life after experiencing perceived stress. This result indicates that high-quality friendship support can effectively buffer the impact of perceived stress on college students’ life satisfaction and verifies the cushioning effect model of social support. This epidemic has not only seriously damaged people’s health but also inadvertently changed people’s life satisfaction. For college students, high-quality friendship can not only help them release their emotions but also help them overcome many difficulties in life and reduce life pressure. So that they can feel the beauty of life even during the epidemic and still be hopeful about life in the face of adversity. Thus, results support the notion that friendship quality may act as a protective factor that can mitigate the risk of stress and improve life satisfaction.

Overall, college students with more access to epidemic information and higher friendship quality have higher life satisfaction. Even when one gets little useful information, college students with high-quality friendships can still buffer stress and have a good life experience. The results highlight that it is essential to establish support systems to provide the necessary resources for individuals who lack the quality of friendship and governments should establish a public trust platform to timely release information related to the epidemic (Tang, 2020) and improve life satisfaction of individuals during the epidemic.

Limitations

Several limitations need to be considered when interpreting the implications of the findings. Firstly, because this was a cross-sectional study, we could not make causal inferences about the results or investigate the dynamic process. Future research should use longitudinal designs to test our moderated mediation model. Secondly, all variables were assessed via self-report measures, which might affect the validity of the present study. Finally, COVID-19 is currently spreading in many countries in the world, so further verification with samples from other countries that may be more heavily affected by COVID-19 may warrant further inquiry. Despite these limitations, however, the current study has several theoretical and practical contributions. From a theoretical perspective, this study further extends previous research by examining the mediating role of perceived stress and the moderating role of friendship quality. From a practical perspective, results from this study may be used to examine the efficacy of friend-oriented social interventions in mitigating the negative effects of perceived stress due to access to epidemic information failure on quality of life.

Conclusion

In summary, while further replication and extension of the current results are still needed to make definitive claims, this study is an important step in unpacking how access to epidemic information relates to the development of life satisfaction among Chinese college students. This study showed that perceived stress serves as one potential mechanism by which access to epidemic information was associated with more life satisfaction. The focus on perceived stress brings additional nuances in linking access to epidemic information to life satisfaction of college students. Moreover, the relationship between access to epidemic information and perceived stress as well as perceived stress and life satisfaction were moderated by friendship quality, and the relationship between access to epidemic information and perceived stress became stronger for college students with high friendship quality. But the relationship between perceived stress and life satisfaction was weaker for high friendship quality among college students.

Author’s Contributions

B. Y, J. H, and G. X. are Co-first authors as they contributed equally to this paper. B. Y and Y. Z design the study. B. Y and J. H collected and interpreted the data. J. H and G. X applied the search strategy, analyzed the data, and writing the manuscript. M. L, X. W, Q. Y, and F. X revised the manuscript. Y. Z conceptualized the models and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Baojuan Ye, Jing Hu, Gensen Xiao are Co-first authors as they contributed equally to this paper.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Baojuan Ye, Email: yebaojuan0806@163.com.

Jing Hu, Email: hj01021@163.com.

Gensen Xiao, Email: gensenxiao@gmail.com.

Yanzhen Zhang, Email: zyz122@gmail.com.

Mingfan Liu, Email: lmfxub@sina.com.

Xinqiang Wang, Email: xinqiangw101@163.com.

Qiang Yang, Email: davidyang12345@163.com.

Fei Xia, Email: 13065199630@163.com.

References

- Abdollahi A, Abu Talib M, Carlbring P, Harvey R, Yaacob SN, Ismail Z. Problem-solving skills and perceived stress among undergraduate students: The moderating role of hardiness. Journal of Health Psychology. 2018;23(10):1321–1331. doi: 10.1177/1359105316653265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew N, Meeks S. Fulfilled preferences, perceived control, life satisfaction, and loneliness in elderly long-term care residents. Aging and Mental Health. 2016;22(2):1–7. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1244804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan I, Ochnik D, Cinar O. Exploring perceived stress among students in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(23):8961. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17238961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bawden D, Robinson L. The dark side of information: Overload, anxiety and other paradoxes and pathologies. Journal of Information Science. 2009;35(2):180–191. doi: 10.1177/0165551508095781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D, Furman W. The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development. 1987;58(4):1101–1113. doi: 10.2307/1130550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger K, Samuel R. The role of perceived stress and self-efficacy in young people’s life satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2017;46(1):78–90. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0608-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang BR, Bai BY, Zhong N. Effect of negotiable fate on subjective well-being: The mediating role of meaning in life. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;25(4):724–730. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2017.04.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsano P, Musetti A, Caricati L, Magnani B. Keeping secrets from friends: Exploring the effects of friendship quality, loneliness and self-esteem on secrecy. Journal of Adolescence. 2017;58:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton JL. A review of research on Schachter’s theory of emotion and the misattribution of arousal. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;11(4):365–397. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420110403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Tisak J, Causey D, Hryshko A, Reid G. A two-year longitudinal study of stressful life events, social support, and social problem-solving skills: Contributions to children's behavioral and academic adjustment. Child Development. 1991;62(3):583–599. doi: 10.2307/1131133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality Social Psychology. 1986;50(5):992–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.5.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63(1):103–115. doi: 10.2307/1130905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner AE, Fite PJ, Colder CR. Parenting and friendship quality as predictors of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in early adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19(1):101–108. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9289-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng, R. L., Xu, J. G., Jin, Y., Wang, N., & Fu, L. H. (2020a). Research on individuals' information acquisition behavior and fear of missing out during a major public health emergency: coronavirus disease 2019. Library and Information Service, (15), 112–122. 10.13266/j.issn.0252-3116.2020.15.014.

- Geng Y, Gu J, Zhu X, Yang M, Zhao F. Negative emotions and quality of life among adolescents: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2020;20:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guere HN. What kind of information we receive about COVID-19. Perception and consumption study. Chasqui-revista Ltinamericana De Comunicacion. 2021;145:67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X. S., & Wu, J. (2018). Relationship between stress perception and life satisfaction in poor college students: Moderating effect of future sense of control. A Think-tank Era, (30), 37-38. CNKI: SUN: ZKSD.0.2018-30-023.

- Hartog, P. (2017). A generation of information anxiety: Refinements and recommendations. The Christian Librarian, 60(1), 44–45. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/tcl/vol60/iss1/8/.

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Ho, H. Y., Chen, Y. L., & Yen, C. F. (2021). Moderating effects of friendship and family support on the association between bullying victimization and perpetration in adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, (3), 088626052098550. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Huebner ES. Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research. 2004;66(1–2):3–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-2312-52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner ES, Laughlin JE, Ash C, Gilman R. Further validation of the multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1998;16(2):118–134. doi: 10.1177/073428299801600202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, S. M., Shi, K., Zhou, H. M., Guo, H. D., & Gao, W. B. (2020). People’s psychological state and emotional guidance strategies in the face of the risk information of COVID-19. Medicine and Society, (5), 98-104. 10.13723/j.yxysh.2020.05.021.

- Karatzias T, Chouliara Z, Power K, Brown K, Begum M, Mcgoldrick T, Mac Lean R. Life satisfaction in people with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Mental Health. 2013;22(6):501–508. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2013.819418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesswetter M, Marsoner H, Luehwink A, Fistarol M, Mahlknecht A, Duschek S. Impairments in life satisfaction in infertility: Associations with perceived stress, affectivity, partnership quality, social support and the desire to have a child. Behavioral Medicine. 2020;46(2):130–141. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2018.1564897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. The correlation analysis between Korean middle school students’ emotional level and friendship in science learning. Journal Pendidikan IPA Indonesia. 2020;9(1):22–31. doi: 10.15294/jpii.v9i1.22744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, In-soo O. A study on the relationship between parental overprotection and college student burnout: The moderated mediating effect of ego-resiliency and friendship quality. Journal of Educational Innovation Research. 2019;29(1):207–227. doi: 10.21024/pnuedi.29.1.201903.207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King RB, Dela Rosa ED. Are your emotions under your control or not? Implicit theories of emotion predict well-being via cognitive reappraisal. Personality and Individual Differences. 2019;138:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.09.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kingery JN, Marshall EKC. Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents' adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2011;57(3):215–243. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2011.0012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, You X. Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Social Indicators Research. 2013;110(1):271–279. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong F, Wang X, Zhao J. Dispositional mindfulness and life satisfaction: The role of core self-evaluations. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;56:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kugbey N, Meyer-Weitz A, Oppong Asante K. Access to health information, health literacy and health-related quality of life among women living with breast cancer: Depression and anxiety as mediators. Patient Education and Counseling. 2019;102(7):1357–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laborde S, Anne B, Weber J, Anders LS. Trait emotional intelligence in sports: A protective role against stress through heart rate variability? Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51(1):23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakey B, Heller K. Social support from a friend, perceived support, and social problem solving. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1988;16(6):811–824. doi: 10.1007/BF00930894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Jiang Z, Han X, Shang X, Tian W, Kang X, Fang M. A moderated mediation model of perceived stress, negative emotions and mindfulness on fertility quality of life in women with recurrent pregnancy loss. Quality of Life Research. 2020;29(7):1775–1787. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JY, Ma L. The effect of the passive use of social networking sites on college students' fear of missing out: The role of perceived stress and optimism. Psychological Science. 2019;42(4):949–955. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20190426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao HJ, Li ZY, Ou Yang LY. The relationship between impoverished college students' perceived stress and mental health. Chinese Journal of Special Education. 2015;5:91–96. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3728.2015.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limcaoco, R. S. G., Mateos, E. M., Fernandez, J. M., & Roncero, C. (2020). Anxiety, worry and perceived stress in the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary results. MedRxiv. 10.1101/2020.04.03.20043992.

- Ling H, En FU, Zhang J. Peer relationships of left-behind children in China moderate their loneliness. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal. 2017;45(6):901–914. doi: 10.2224/sbp.6021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, K. C., Ling, C. P., Zhimin, W., Hung, K. K., & Leong, L. H. (2021). The impacts of reactive aggression and friendship quality on cyberbullying behaviour: An advancement of cyclic process model. Research Anthology on Rehabilitation Practices and Therapy.

- Liu Y, Wang ZH, Li ZG. Affective mediators of the influence of neuroticism and resilience on life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;52(7):833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Markovic A, Bowker JC. Friends also matter: Examining friendship adjustment indices as moderators of anxious-withdrawal and trajectories of change in psychological maladjustment. Developmental Psychology. 2017;53(8):1462–1473. doi: 10.1037/dev0000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny KB, Curlette WL, Aysan F, Herrington A, Gfroerer CA, Thompson D, Hamarat E. Coping resources, perceived stress, and life satisfaction among Turkish and American university students. International Journal of Stress Management. 2002;9(2):81–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1014902719664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mccullough G, Huebner ES, Laughlin J. Life events, self-concept, and adolescents’ positive subjective well-being. Psychology in the Schools. 2000;37(3):281–290. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(200005)37:3<281::AID-PITS8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29(4), 611-621. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611.

- Pedrozo-Pupo JC, Pedrozo-Cortés MJ, Campo-Arias A. Perceived stress associated with COVID-19 epidemic in Colombia: An online survey. Cadernos De Saude Publica. 2020;36:e00090520. doi: 10.1590/0102-311X00090520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor CL, Linley PA, Maltby J. Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009;10(5):583–630. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W, Chan MM, Cui LJ. Time pressure, anxiety and job satisfaction: Perceive control of time as a mediator. Psychological Research. 2014;7(4):74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sahler OJZ, Dolgin MJ, Phipps S, Fairclough DL, Askins MA, Katz ER, Butler RW. Specificity of problem-solving skills training in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer: Results of a multisite randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(10):1329–1335. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AE, Abboud LA, Bogaert P. Making the case for strong health information systems during a pandemic and beyond. Archives of Public Health. 2021;79(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00531-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi K, Fan HX, Jia JM. The risk perceptions of SARS and socio-psychological behaviors of urban people in China. Journal of Psychology. 2003;35(4):546–554. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton.

- Tang DH. Recommendations for psychosocial response during the COVID-19 epidemic. Chinese Journal of Mental Health. 2020;34(3):238–239. [Google Scholar]

- Terry N, Shelton KH, Riglin L, Frederickson N, Mcmanus IC, Rice F. 'Best friends forever'? Friendship stability across school transition and associations with mental health and educational attainment. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2019;89(4):585–599. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BX, Dang AK, Thai PK, Le HT, Le XTT, Do TTT, Ho CS. Coverage of health information by different sources in communities: Implication for COVID-19 epidemic response. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(10):3577. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valizadeh-Haghi S, Khazaal Y, Rahmatizadeh S. Health websites on covid-19: Are they readable and credible enough to help public self-care? Journal of the Medical Library Association JMLA. 2021;109(1):75–83. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2021.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schalkwyk GI, Marin CE, Ortiz M, Rolison M, Qayyum Z, McPartland JC, Silverman WK. Social media use, friendship quality, and the moderating role of anxiety in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017;47(9):2805–2813. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3201-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., & Gan, W. (2010). Relationship between anxiety level, life stress and social support of college students. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 18(9), 1081-1083. CNKI: SUN: JKXL.0.2010-09-026.

- Wang, L., & Ma, Z. Q. (2020). Research on information anxiety of university students under the epidemic of COVID-19——From the perspective of stress disorder. Journal of Modern Information, (7). 10.3969/j.Issn.1008-0821.2020.07.002.

- Wang XQ, Zhang DJ. The change of junior middle school students’ life satisfaction and the prospective effect of resilience: A two year longitudinal study. Psychological Development and Education. 2012;28(1):91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. I., Zhang, M. Q., Tan, G.L, & L, F. (2020a). The relationship between cybervictimization and self-injury of adolescents: The moderating role of friendship quality and ruminative response. Psychological science, 43(2), 363–370. 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200215.

- Wang YL, Zhang MQ, Tan GL, Lin F. The relationship between internet bullying and self-injury among adolescents: The moderating role of friendship quality and rumination thinking. Psychological Science. 2020;43(2):363–370. doi: 10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen A, Ni H. The relationship between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese adolescents: A moderated-mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:572100. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.572100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen X, Gong J, Yan Y. Relationships between stress, negative emotions, resilience, and smoking: Testing a moderated mediation model. Substance Use & Misuse. 2016;51(4):427–438. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.1110176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Analysis of influencing factors of internet information anxiety of university students. Journal of Xi’an University of Posts and Telecommunications. 2017;22(1):122–126. doi: 10.13682/j.issn.2095-6533.2017.01.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiernik E, Pannier B, Czernichow S, Nabi H, Hanon O, Simon T, Simon JM, Thomas F, Bean K, Consoli SM, Danchin N, Lemogne C. Occupational status moderates the association between current perceived stress and high blood pressure: Evidence from the IPC cohort study. Hypertension. 2013;61(3):571–577. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 an emerging global health threat. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 13(4), 644–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Xiong CQ, Xu YL. Reliability and validity of the China version of the life satisfaction scale in the public. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;17(8):948–949. doi: 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2009.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YZ, Huang HT. An epidemiological study on stress among urban residents in social transition period. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;24(9):760–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Liu X, Wang M. Parent-child cohesion, friend companionship and left-behind children’s emotional adaptation in rural China. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2015;48:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng XF. Memory information processing in two states of anxiety and priming emotion. Psychological Science. 2005;2:351–355. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-6981.2005.02.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y, Zhou Z, Liu Q, Yang X, Fan C. Perceived stress and life satisfaction: A multiple mediation model of self-control and rumination. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28(11):3091–3097. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01486-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zou H, Zhou H, Zhou Y. The relationship between friendship, friendship quality and peer acceptance of middle school students. Journal of Beijing Normal University: Social Science Edition. 1998;1:43–50. [Google Scholar]