Abstract

Intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) immunotherapy has been the gold standard adjuvant treatment for intermediate- and high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) after transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT). BCG immunotherapy prevents disease recurrence and progression to muscle-invasive disease following TURBT. Although most patients initially respond well to intravesical BCG, considerable concern has been raised for patients with BCG failure who are refractory or recur in 6 months after their last BCG, which implies ‘BCG-unresponsiveness’. Based on current clinical guidelines, early radical cystectomy (RC) is recommended to treat BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. However, due to the high risk of morbidity and mortality of RC and patients' desire to preserve their own bladder, there is a critical unmet need for alternative conservative treatments as bladder-sparing strategies in BCG-unresponsive patients. Trials for effective bladder-sparing treatments are ongoing, and several novel agents have been recently tested in the NMIBC setting. The goal of this review is to introduce and summarize recently reported novel and emerging drugs and ongoing clinical trials for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.

Keywords: Antibody-drug conjugate, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, Immune checkpoint inhibitors, Oncolytic virotherapy, Urinary bladder neoplasms

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the fifth most prevalent cancer worldwide. Globally, 549,393 new cases and 199,922 deaths from bladder cancer were reported in 2018 [1]. The National Cancer Institute estimated that over 79,000 new cases of UC were diagnosed in 2017, of which more than 16,000 people died in the United States alone. Based on the Korea Central Cancer Registry, 4,379 new cases were diagnosed in 2017 in Korea [1,2].

UC of the bladder can be categorized as non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), and metastatic bladder cancer according to stage. NMIBC constitutes 75% of primary diagnoses and is characterized by frequent recurrence and progression to MIBC. Of bladder cancer patients, 20% are classified with MIBC at diagnosis, and the condition is potentially lethal in approximately 50% of patients despite radical cystectomy (RC) [3,4]. International guidelines recommend treatment methods based on classification of NMIBC into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups according to the probability of recurrence and progression (Table 1) [5,6,7]. The current gold standard for intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC is transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) followed by intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) instillation. The mycobacterium strain to which BCG belongs is being improved. For instance, Mycobacterium smegmatis is less pathogenic than Mycobacterium bovis but easier to cultivate in the laboratory owing to its rapid reproduction [8]. Further, the antitumor immune effect of M. smegmatis can be increased using genetic engineering [9,10]. BCG is a live, attenuated M. bovis, which induces a nonspecific anti-tumor immune response in the bladder mucosa, although the exact mechanism of BCG is not completely understood [11]. Intravesical BCG after TURBT has been reported to reduce risk of recurrence by 20% to 65% at 5 years [12,13]. BCG may also reduce disease progression. A meta-analysis and several large studies have indicated a reduction in risk of progression by 30% to 50% when compared to TURBT alone [12,13,14]. Bladder preservation and time to RC were also improved by BCG in the adjuvant setting [15].

Table 1. Risk group stratification by the international guidelines and risk-based treatment strategies in NMIBC.

| Risk group | EAU | AUA | NCCN | Treatment recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-risk | Primary, solitary, Ta, LG/G1, <3 cm, no CIS | Small volume, LG Ta | LG Ta | TURBT+single immediate instillation of intravesical chemotherapy |

| Intermediate-risk | All tumors not defined in the two adjacent categories (between the category of low and high risk) | Multifocal and/or large volume LG Ta (high risk of recurrence, low risk of progression) | HG Ta | TURBT+single immediate instillation of intravesical chemotherapy±either intravesical chemotherapy for a maximum of 1 year or 1-year full-dose BCG |

| High-risk | Any of the following: • T1 tumor • HG/G3 tumor • CIS • Multiple and recurrent and large (≥3 cm) Ta, G1, G2 tumors |

HG Ta, all T1, CIS | All T1 (CIS listed separately) | TURBT±re-staging TURBT+intravesical full-dose BCG instillation for 1–3 years (induction and maintenance course) or cystectomy |

NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; EAU, European Association of Urology; AUA, American Urological Association; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; LG, low grade; TURBT, transurethral resection of bladder tumor; HG, high grade; BCG, bacillus Calmette–Guérin; CIS, carcinoma in situ.

In particular, carcinoma in situ (CIS) is a type of NMIBC that exhibits high-grade features and increases the risk of recurrence and progression [16,17]. Generally, 40% to 60% of untreated CIS patients develop MIBC with an average risk of progression of 54% within 5 years of diagnosis [16,17]. The complete resolution rate of CIS after intravesical BCG treatment was 60% to 70% and 30% with a median disease-free survival of 4 and 10 years, respectively [18].

Nevertheless, 20% to 50% of NMIBC patients may recur or progress to MIBC despite sufficient intravesical BCG therapy; these patients are considered as ‘BCG failure’ [19,20]. Given that BCG failure is associated with an increased risk of progression to muscle-invasive disease and substantial risk of death, both the European Association of Urology (EAU) and American Urological Association (AUA) have recommended early RC as a standard treatment option for BCG-refractory NMIBC patients [5,6]. However, RC is associated with morbidity and mortality rates of 28% to 94% and 2% to 5%, respectively. Further, many patients either have comorbidities precluding surgical intervention or refuse cystectomy due to concerns about decreased quality of life [21]. Additionally, the global BCG supply is becoming more tenuous, which has substantially impacted patient treatment options.

Additional intravesical therapy with non-BCG agents has been extensively evaluated in both front-line and post-BCG settings [22]. Valrubicin is the only agent approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients with BCG-failed CIS who are not medically eligible for or refuse cystectomy. Several studies on intravesical valrubicin demonstrated a complete response (CR) rate of 18% to 21% at 6 months and an estimated CR rate of 16.4% at 12 months [23,24,25]. Several intravesical chemotherapeutic agents have been evaluated in BCG-failed NMIBC but have demonstrated variable efficacy because heterogeneous groups of patients were included, and they do not provide a satisfactory oncologic efficacy profile [23,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Systemic immunotherapy using pembrolizumab has recently received approval from the FDA for the treatment of patients with BCG-unresponsive high-risk NMIBC with CIS who are ineligible for or decline RC. Furthermore, several clinical trials investigating the efficacy of novel agents in BCG-unresponsive disease are in progress.

In this paper, we clarified the concept of BCG unresponsive NMIBC who will not benefit from additional BCG courses anymore and summarized salvage treatment options at the frontier of therapeutic approaches for BCG-failure NMIBC. We also provide an overview of novel and emerging drugs, including immune check point inhibitors, viral gene therapy as GC0070 or nadofaragene firadenovec, and antibody-drug-conjugate as oportuzumab monatox in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC by discussing the available data and ongoing relevant clinical trials.

DEFINITION OF BCG UNRESPONSIVENESS

The prognosis of patients with a recurred tumor after optimal BCG therapy differs to that of patients with recurrence following suboptimal or inadequate treatment. Therefore, a precise definition of BCG failure is crucial when assessing patients with tumor recurrence after BCG immunotherapy. Similarly, the prognosis of patients with recurrence of a low-grade tumor or more than 1 year after the last dose of BCG is clearly more favorable than that of patients presenting with a high-grade and/or T1 tumor recurrence or less than 1 year [32], which affects subsequent clinical management. Therefore, several principles should be considered when managing recurrent NMIBC patients. First, maintenance therapy following BCG induction may be considered sufficient BCG immunotherapy, particularly in high-risk NMIBC groups. Studies have demonstrated that a 6-week induction course of BCG followed by maintenance BCG instillations at regular intervals is important for preventing recurrence and tumor progression [33,34,35,36]. The typical intravesical BCG course includes a six-times weekly induction course followed by three-times weekly maintenance intravesical instillations at 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 months, termed the SWOG 6+3 regimen [33,37]. Current guidelines recommend 1 to 3 years of maintenance with three weekly instillations based on the risk of tumor recurrence and progression [3,4,5]. For clinical trial design, sufficient intravesical BCG therapy can be defined as the performance of at least five-times weekly induction course followed by one maintenance or reinduction course at least two-times instillations [15,38]. Second, various terminology has been used to define the different types of BCG failure (Table 2). The term “BCG-intolerant” implies a situation whereby a patient cannot receive BCG due to a serious adverse events (AEs) or symptomatic intolerance [4,5]. “BCG-refractory” indicates the presence of persistent high-risk NMIBC at 6 months after the start of induction therapy or progression of disease stage or grade at 3 months after the start of induction therapy [4,5]. “BCG-relapsing” refers to tumor recurrence after achieving a disease-free status by 6 months after adequate BCG treatment [4,5]. Among patients experiencing BCG relapse, those with recurrent high-risk NMIBC within 6 months or CIS recurrence within 12 months from the last BCG exposure are likely to have poor prognosis, similar to BCG-refractory patients. Consequently, both BCG-refractory and BCG-relapsing patients who recur within 6 months or present with CIS recurrence within 12 months after their last BCG exposure are combined into the “BCG-unresponsive” category [15]. The term “BCG-unresponsive” indicates patients at high risk of disease recurrence and progression, who have failed intravesical BCG therapy and who will no longer benefit from additional BCG courses.

Table 2. Types of BCG failure in NMIBC.

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| BCG intolerance | Tumor recurs after less than an adequate course of therapy due to a BCG related adverse event |

| BCG refractory | 1) Increase in tumor stage, grade, or disease extent at 3 months after iBCG |

| 2) Persistent high-risk disease at 6 months (failure to achieve a disease-free status by 6 months) despite adequate BCG (iBCG+mBCG) treatment | |

| BCG relapsing | Recurrence of high-risk disease after achieving a disease-free status by 6 months after adequate BCG (iBCG+mBCG) treatment (early <12 months, immediate 12–24 months, and late <24 months) |

| BCG unresponsive | BCG refractory or BCG relapse with high-risk tumor within 6 months or CIS development within 12 months from last BCG exposure |

BCG, bacillus Calmette–Guérin; NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; iBCG, induction BCG; mBCG, maintenance BCG.

SALVAGE TREATMENTS FOR BCG FAILURE NMIBC

RC is recommended as the standard of care in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC by various guidelines and expert panels, i.e. EAU and AUA guidelines [5,6]. A retrospective study demonstrated that disease-specific survival was improved in NMIBC patients experiencing disease recurrence or progression after BCG who underwent early RC (92% within 2 years of initial BCG) compared to that in patients who underwent delayed RC (56% after 2 years of initial BCG) [39]. In another retrospective study of patients with T1 recurrence after BCG, patients who underwent RC exhibited a decreased incidence of death from cancer (31%) when compared to those who were treated with repeat TURBT and intravesical BCG (48%) [40]. Furthermore, tumor progression to muscle-invasive disease in patients initially presenting with NMIBC portends a poorer prognosis compared to that of patients with initial T2 disease presentation [41,42]. However, the decision to perform RC should be determined carefully given the morbidity and mortality rates of 20% to 94% and 2% to 5%, respectively, as well as the detrimental impact on patients' quality of life associated with the procedure [21,43,44]. Moreover, with the aging of the population, a substantial number of patients are unsuitable for radical treatment owing to their comorbidities and frailty. These factors have led clinicians to seek bladder preserving treatment options that are less invasive in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.

1. Intravesical chemotherapy

Several intravesical chemotherapeutic agents have been assessed for BCG failure NMIBC, either alone or in combination. Valrubicin is the only FDA-approved agent for intravesical use in CIS patients with BCG failure when RC is not an option. A pivotal single-arm study, which included 90 BCG failure patients treated with intravesical valrubicin (six or nine weekly doses of 800 mg in 75 mL saline), reported that the CR rate was 21% at 6 months [23]. The majority of AEs were classified as local bladder symptoms, and 81 patients (90%) had at least one AE during treatment. The most common AEs included urinary frequency (66%), urinary urgency (63%), and dysuria (60%); however, most AEs were mild to moderately severe and none were life threatening [23]. Updated results from both this study and another phase II/III trial (A9303 study), which enrolled 80 patients with BCG-refractory/recurrent CIS containing NMIBC, revealed that the 6-month CR rate was lower (18%) [24]. Of the 80 patients, 69 (86%) experienced at least one local bladder symptom during treatment and 36 (45%) during follow-up. However, the majority of symptoms were mild to moderately severe (73% [45/62] during treatment; 75% [15/20] during follow-up) [24]. The most common local bladder symptoms were urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and dysuria [24]. A multi-institutional retrospective analysis for 113 NMIBC patients who failed previous intravesical treatments, including BCG and/or chemotherapy, demonstrated that the 12-month CR rate to intravesical valrubicin was even lower (16.4%) [25]. Treatment-related local bladder symptoms and serious AEs were reported in 56 (49.6%) and 7 (6.2%) patients, respectively [25]. The most common local bladder symptoms were hematuria (17.7%), pollakiuria (17.7%), micturition urgency (15.9%), bladder spasm (14.2%), and dysuria (13.3%) [25]. In total, 4.4% (5/113) of patients discontinued valrubicin owing to AEs [25]. These data suggest that intravesical valrubicin is a suboptimal salvage treatment in terms of efficacy in BCG-unresponsive settings.

Traditionally, gemcitabine has been systemically used in neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant settings of MIBC and palliative settings of locally advanced or metastatic UC (mUC). However, gemcitabine has been extensively investigated as a salvage intravesical agent in BCG failure NMIBC. In a phase II trial of 30 patients treated with intravesical gemcitabine after BCG failure, the CR rate at 12 months was 21%, with median follow-up duration of 19 months [45]. Three patients showed grade 2 dysuria defined by occasional pain or difficulty urinating, and six patients had grade 3 dysuria defined by continuous difficulty urinating with pain and frequency [45]. One patient developed a rash on the glans penis, and one patient who was receiving immunosuppressants for a renal transplantation developed cellulitis of the leg and required intravenous antibiotics [45]. A multi-institutional phase II study (SWOG S0353 trial) of 58 patients treated with intravesical gemcitabine (2,000 mg/100 mL normal saline six times weekly, and then monthly for 12 months) after at least two prior BCG courses demonstrated that a CR rates were 28% and 21% at 12 months and 24 months, respectively [46]. A total of 34 patients (62%) showed grade 1–2 toxicity, primarily dysuria and urinary frequency, whereas 3 showed grade 3 toxicity (dysuria, frequency, and neutropenia). No patients had grade 4 or 5 toxicity. One patient discontinued treatment 4 weeks after starting treatment because of personal reasons and another 5 weeks after because of grade 2 dysuria [46]. Although the efficacy of gemcitabine in true BCG-unresponsive NMIBC is unknown, several trials have reported that intravesical gemcitabine has superior efficacy and safety profiles when compared to repeat BCG in NMIBC patients failing one course of BCG [28]. Further, patients with high-grade recurrence after BCG exhibit better disease-free survival and lower toxicity when treated with gemcitabine as opposed to mitomycin (MMC) [27]. Despite these promising results, the long-term efficacy of gemcitabine in BCG unresponsive NMIBC for preventing disease progression remains unknown [28].

Taxanes have been investigated for intravesical use in BCG failure NMIBC. A phase I study of 18 NMIBC patients treated with intravesical docetaxel after at least one course of BCG demonstrated that 1-year CR rate was approximately 50%, and 22% of patients maintained disease-free status at 4 years [47]. None of the patients experienced any delayed toxicities [47]. Updated results from an expanded cohort (54 patients) revealed that 1- and 3-year recurrence-free survival rates for the entire cohort treated with intravesical docetaxel (maximum dose of 75 mg/100 mL; six weekly and monthly instillations for maximum of a 9 maintenance) were 40% and 25%, respectively [48]. In a similar patient population, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel as salvage intravesical chemotherapeutic agent resulted in a 36% disease-free rate at 1 year in 28 BCG-failed NMIBC patients [49]. Treatment-related AEs were observed in nine patients (32.1%) and were limited to grade 1 (four patients, 14%) or 2 (five patients, 18%), with no grade 3 or higher, toxicities [49]. Grade 1 or 2 AEs included fatigue, urinary frequency and urgency, hematuria, and urinary tract infection. There was no treatment discontinuation due to treatment-related AEs [49].

Based on mechanisms of action, chemotherapy combinations have evolved around sequential intravesical gemcitabine followed by intravesical docetaxel or MMC. In a retrospective analysis, 27 patients with recurrent NMIBC after BCG therapy received intravesical gemcitabine (1 g/50 mL for 90 min weekly for 6–8 weeks) followed by intravesical MMC (40 mg/20 mL for 90 min weekly for 6–8 weeks) [30]. The median disease-free survival of all patients was 15.2 (range, 1.7–39.3) months, and 10 patients (37%) demonstrated recurrence-free at a median follow-up duration of 22 months [30]. AEs were observed in eight patients (29.6%), and the most common side effect was irritative voiding and bladder spasm (22%), which occurred in six patients [30]. Anemia, thought to be secondary to systemic absorption of gemcitabine, occurred in two patients (7%), and one patient (4%) developed acute renal failure during treatment [30]. Four patients, one with acute renal failure and three with secondary irritative voiding symptoms, received incomplete courses of therapy [30]. A recent multi-institutional, retrospective study reported that the use of sequential intravesical gemcitabine (1 g/50 mL for 60 min weekly for 6 weeks) and docetaxel (37.5 mg/50 mL for 60 min weekly for 6 weeks) in 276 NMIBC patients who recurred after BCG treatment resulted in 1-year and 2-year recurrence-free survival rates of 60% and 46%, respectively, with manageable tolerability [50]. Further large prospective studies are required to verify these preliminary results.

2. Device-assisted treatments

Device-assisted treatments have been applied with the purpose of improving the efficacy of intravesical chemotherapy by increasing its permeability through the bladder wall. Among these approaches, chemohyperthermia (CHT), electromotive drug administration (EMDA), and photodynamic therapy (PDT) have been extensively studied [51].

CHT therapy aims to attain a bladder wall temperature >41℃ for at least two sessions of 20 minutes each, while circulating a solution of MMC. The use of combined CHT and intravesical MMC in NMIBC patients has been investigated extensively. A retrospective analysis of 111 BCG failure NMIBC patients reported that CHT+MMC yielded 1- and 2-year disease-free survival rates of 85% and 56%, respectively, and the progression rate was 3% for all patients, with a median follow-up period of 16 months (range, 2–72 months) [52]. AEs occurred in 45% of patients, of which most were mild (grade 1 or 2) and transient. The most common AEs were bladder spasm (30.6%) and pain (27.0%) during treatment sessions, followed by hematuria (18.9%), dysuria (16.2%), and transient incontinence (9.9%) [52]. In a randomized controlled trial comparing CHT+MMC with BCG in 190 intermediate- and high-risk NMIBC patients, 24 month recurrence-free survival rates were 78.1% and 64.8% in the CHT+MMC group and BCG group, respectively [53]. Progression was observed in less than 2% of patients in both groups. In the CHT+MMC group, the most common AEs during treatment sessions were bladder spasms (14.4%) and bladder pain (14.1%). The most common AEs after treatment were dysuria (11.7%), nocturia (10.3%), and urinary frequency (9.9%) [53]. Although encouraging, these results should be cautiously interpreted in terms of their applicability to BCG-unresponsive patients, because a large proportion of tumors were not high grade, and prior BCG treatment within 48 months was an exclusion criterion of the study. Indeed, 95% of patients in this trial were BCG-naïve [53].

EMDA enhances the penetration of chemotherapeutics across the bladder urothelium and stroma via iontophoresis [54]. In a randomized trial comparing BCG alone with sequential BCG+EMDA MMC in treatment-naïve T1 bladder cancer patients, the sequential BCG+EMDA MMC group exhibited a longer disease-free interval (69 months) when compared to the BCG alone group (21 months). Other secondary end-points, including recurrence rate (41.9% vs. 57.9%), progression (9.3% vs. 21.9%), overall mortality (21.5% vs. 32.4%), and disease-specific mortality (5.6% vs. 16.2%) were more favorable in the sequential BCG+EMDA MMC group [55]. Neither the frequency nor severity of AEs differed between both groups. In the BCG+EMDA MMC group, AEs were mainly localized in the bladder, including macroscopic hematuria (64/107), dysuria (54/107), and drug-induced cystitis (49/107) [55]. Three patients from each group withdrew from the study because of severe AEs [55]. To date, only one study has evaluated the efficacy of EMDA in BCG failure settings [56]. This prospective phase II trial enrolled 26 patients with recurrent high-grade NMIBC after BCG therapy. The high-grade recurrence-free survival was 61.5%, with a median follow-up duration of 36 months [56]. Of patients, 10 were finally treated with RC due to persistent high-grade disease (six patients, 23.1%) or progression to muscle-invasive stage (four patients, 15.4%) [56]. Three patients (11.5%) showed severe adverse systemic events of hypersensitivity to MMC with a hand-foot reaction, which caused treatment discontinuation. Six patients (23.1%) had local AEs, namely dysuria (15.4%), pain (11.5%), bladder spasms (11.5%), and frequency/urgency (11.5%) [56]. Although emerging evidence suggests that EMDA may be a useful tool against NMIBC, its specific role in BCG-unresponsive settings requires elucidation in additional well-designed prospective trials.

PDT acts via the activation of a photosensitizer agent that is selectively absorbed by cancer cells following the administration of specific wavelengths of an intravesical light. To date, several PDT-related studies involving small populations have been conducted in NMIBC [57,58,59]. Although PDT is effective for BCG-refractory NMIBC, the wide use of PDT in bladder cancer is limited due to high levels of toxicity (i.e., detrusor scarring, skin hypersensitivity, reduction and loss in bladder capacity, and storage LUTS such as frequency and urgency) [60]. However, novel agents with more effective therapeutic indices and less toxicity are being explored and may offer an effective salvage option for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC.

EMERGING THERAPIES IN BCG-UNRESPONSIVE NMIBC

The current search for effective bladder-sparing approaches for BCG-unresponsive patients is ongoing and represents one of the most relevant unmet needs in the field of urologic oncology. Growing evidence suggests that immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), oncolytic adenoviruses, recombinant interferon-α2b protein, and antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) exhibit promising responses with tolerable toxicity profiles and are potential salvage treatment options for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC [61]. Further, several relevant clinical trials are underway in this setting.

1. Immune checkpoint inhibitors

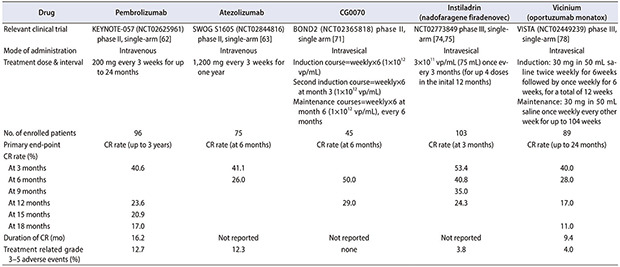

ICIs block programmed cell death 1 protein (PD-1) and/or the programmed cell death 1 protein ligand (PD-L1)-mediated pathways, and have been mainly assessed in mUC settings. To date, five ICIs blocking PD-1 (pembrolizumab and nivolumab) or PD-L1 (atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab) have been approved by the FDA for first- or second-line use in mUC [62]. In a small study of NMIBC patients, at least 30% of patients expressed PD-1, with an association noted between PD-1 expression and prior BCG therapy [63]. Another study demonstrated marked expression of PD-L1 in 69% of post-BCG relapsed urothelial cancer tumors compared to 19% of BCG-naïve tumors from the same patients [64]. These data implicate the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway as a key resistance mechanism to traditional BCG therapy in NMIBC. Recently, the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab has gained FDA approval for the treatment of patients with BCG-unresponsive high-risk NMIBC with CIS who are ineligible for or decline RC. This approval was based on preliminary results of the KEYNOTE-057 (NCT02625961) phase II trial [65]. This study enrolled 96 patients with BCG-unresponsive high-risk NMIBC with CIS to receive intravenous administration of 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks until unacceptable toxicity, persistent or recurrent high-risk NMIBC, or disease progression. Primary end point was CR rate with absence of high grade NMIBC and secondary end point was duration of response. At a median follow-up duration of 28 months, the CR rate was 41.2%. Among the 39 patients who achieved a CR, the median duration of response was 16.2 months, and 46% exhibited a response of 12 months or longer (Table 3) [65]. As the treatment was proceeded, no patient developed muscle-invasive or metastatic disease while receiving pembrolizumab. Of the 39 CR patients, 22 experienced recurrence, and 40% of them had cystectomy. Fifty-seven patients showed failure to CR, 47 percent of whom had cystectomy. Of the 36 patients who received cytectomy after pembrolizumab, only 3 cases who are non-responders to pembrolizumab progressed to muscle invasive bladder cancer. 66% of patients experienced treatment-related side effects, although side effects above grade 3 occurred in 13% of patients, which is similar to previous reports of pembrolizumab monotherapy. Nine percent of patients discontinued treatment due to treatment-related side effects. Immune-related side effects occurred in a total of 21 people, and grade 3–4 side effects occurred in 3 patients. The most common side effects were thyroid-related side effects in 13 patients. Pneumonitis was the most common adverse reaction that led to permanent discontinuation of pembrolizumab.

Table 3. Comparison of emerging novel drugs in BCG unresponsive NMIBC (with CIS).

| Drug | Pembrolizumab | Atezolizumab | CG0070 | Instiladrin (nadofaragene firadenovec) | Vicinium (oportuzumab monatox) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant clinical trial | KEYNOTE-057 (NCT02625961) phase II, single-arm [62] | SWOG S1605 (NCT02844816) phase II, single-arm [63] | BOND2 (NCT02365818) phase II, single arm [71] | NCT02773849 phase III, single-arm [74,75] | VISTA (NCT02449239) phase III, single-arm [78] | |

| Mode of administration | Intravenous | Intravenous | Intravesical | Intravesical | Intravesical | |

| Treatment dose & interval | 200 mg every 3 weeks for up to 24 months | 1,200 mg every 3 weeks for one year | Induction course=weekly×6 (1×1012 vp/mL) | 3×1011 vp/mL (75 mL) once every 3 months (for up 4 doses in the inital 12 months) | Induction: 30 mg in 50 mL saline twice weekly for 6weeks followed by once weekly for 6 weeks, for a total of 12 weeks | |

| Second induction course=weekly×6 at month 3 (1×1012 vp/mL) | ||||||

| Maintenance courses=weekly×6 at month 6 (1×1012 vp/mL), every 6 months | Maintenance: 30 mg in 50 mL saline once weekly every other week for up to 104 weeks | |||||

| No. of enrolled patients | 96 | 75 | 45 | 103 | 89 | |

| Primary end-point | CR rate (up to 3 years) | CR rate (at 6 months) | CR rate (at 6 months) | CR rate (at 3 months) | CR rate (up to 24 months) | |

| CR rate (%) | ||||||

| At 3 months | 40.6 | 41.1 | 53.4 | 40.0 | ||

| At 6 months | 26.0 | 50.0 | 40.8 | 28.0 | ||

| At 9 months | 35.0 | |||||

| At 12 months | 23.6 | 29.0 | 24.3 | 17.0 | ||

| At 15 months | 20.9 | |||||

| At 18 months | 17.0 | 11.0 | ||||

| Duration of CR (mo) | 16.2 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 9.4 | |

| Treatment related grade 3–5 adverse events (%) | 12.7 | 12.3 | none | 3.8 | 4.0 | |

BCG, bacillus Calmette–Guérin; NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; CIS, carcinoma in situ; CR, complete response.

The PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab is also being investigated in BCG unresponsive NMIBC. The results of the SWOG S1605 phase II trial (NCT02844816) were recently presented in the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology Virtual Annual Meeting [66]. The study enrolled 75 patients with BCG unresponsive CIS (with or without concomitant Ta/T1) to receive an intravenous administration of 1,200 mg atezolizumab every 3 weeks for 1 year. The primary end point was the 6-month pathological CR rate as defined by mandatory biopsy, and the secondary end points included the 3-month CR rate and safety profiles. A CR was observed in 30 patients (41.1%) at 3 months and in 19 (26.0%) at 6 months. Possibly-treatment-related AEs were observed in 61 patients (83.6%) [66]. The most frequent AEs were fatigue (49.3%), pruritus (11.0%), hypothyroidism (11.0%), and nausea (11.0%). Grade 3–5 AEs occurred in nine patients (12.3%), and there was one treatment-related death (myasthenia gravis with respiratory failure and sepsis) [66].

The response to these ICIs in UC can be predicted using molecular subtype classifications and immune markers. A series of studies demonstrated that the “genomically unstable” Lund subtype classification was associated with the best response to atezolizumab [67]. Additionally, the neuronal subtype in the Cancer Genome Atlas cohort, which features low levels of transforming growth factor-beta expression and high mutation/neoantigen burden, may be significantly responsive to ICIs in progressive UC [67,68]. Several immune markers, including high CD3 and PD-L1 expression, may predict favorable response to ICIs in UC [69]. Therefore, in a situation in which ICIs are used in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, these molecular subtypes and immune markers may provide therapeutic guidance.

Several PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors are currently being investigated for NMIBC, including BCG-unresponsive disease (Table 4).

Table 4. Ongoing clinical trials in BCG unresponsive NMIBC.

| Clinical trial number | Interventions | Population enrollment | Study design | Phase | Measured endpoints (primary/secondary) | Study completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT02625961 (KEYNOTE-057) [62] | Pembrolizumab (intravenous) | 260 | Single-arm trial | II | CRR, DFS/DoR | July 30, 2023 |

| NCT02808143 [82] | Pembrolizumab (intravesical)+BCG solution | 9 | Single-arm trial | I | MTD/DLTs, TRAE | February 2022 |

| NCT04387461 (CORE1) [83] | Pembrolizumab (intravenous)+CG0070 (intravesical) | 37 | Single-arm trial | II | CRR/TRAE, median DoR, OS, PFS | June 2022 |

| NCT03258593 [84] | Durvalumab (intravenous)+vicinium (intravesical) | 40 | Single-arm trial | I | Safety and tolerability/efficacy, response rate, immune parameters, urinary EpCAM, PD-L1 and PD-1 levels | December 30, 2022 |

| NCT03317158 [85] | Durvalumab (intravenous)±EBRT±BCG | 186 | Randomized, multi-arm, multi-cohort trial <Phase 1> Cohort 1: durvalumab alone Cohort 2a: durvalumab+BCG Cohort 2b: durvalumab+EBRT <Phase 2> Cohort 2a: durvalumab+BCG Cohort 2b: durvalumab+EBRT BCG re-treatment: cross-over durvalumab |

I/II | <Phase 1> MTD/RFS, TRAE <Phase 2> RFS/TRAE |

March 1, 2023 |

| NCT03759496 [86] | Durvalumab (intravesical) | 39 | Single-arm trial | II | MTD, high-grade recurrence free rate/high-grade progression-free rate, PD-L1 and VEGF expression | December 31, 2021 |

| NCT03950362 [87] | Avelumab (intravenous)+radiotherapy | 67 | Single-arm trial | II | High-risk RFS | June 15, 2024 |

| NCT02844816 (SWOG S1605) [63,88] | Atezolizumab (intravenous) | 202 | Single-arm trial | II | CRR, EFS/PFS, cystectomy-free survival, bladder cancer specific survival, OS, TRAE | April 1, 2021 |

| NCT03519256 [89] | Nivolumab (intravenous)±BMS-986205 (intravenous)±BCG | 358 | Randomized, multi-arm trial Arm 1: nivolumab alone Arm 2: nivolumab+BCG Arm 3: nivolumab+BMS-986205 Arm 4: nivolumab+BMS-986205+BCG |

II | CRR, DoR/RFS, TRAE | September 15, 2024 |

| NCT02202772 [90] | Intravesical cabazitaxel, gemcitabine, and cisplatin | 19 | Randomized, multi-arm trial Arm 1: gemcitabine+low dose cabazitaxel Arm 2: gemcitabine+high dose cabazitaxel Arm 3: gemcitabine+high dose cabazitaxel+low dose cisplatin Arm 4: gemcitabine+high dose cabazitaxel+moderate dose cisplatin Arm 5: gemcitabine+high dose cabazitaxel+high dose cisplatin |

I | TRAE/CRR | December 1, 2020 |

| NCT03945162 [91] | TLD-1433 (photosensitizer, intravesical)+photodynamic therapy | 125 | Single-arm trial | II | CRR/TRAE | May 2022 |

| NCT04179162 [92] | BCG+gemcitabine (intravesical) | 68 | Single-arm trial | I/II | MTD, CRR | November 2022 |

| NCT04172675 [81] | Erdafitinib (oral) | 280 | Randomized, multi-cohort trial Cohort 1 (experimental): erdafitinib in highrisk NMIBC without CIS Cohort 1 (active comparator): intravesical chemotherapy (gemcitabine or MMC) in high-risk NMIBC without CIS Cohort 2: erdafitinib in BCG-unresponsive CIS Cohort 3: erdafitinib in intermediate-risk NMIBC without CIS |

II | RFS/ time to progression, time to disease worsening, DFS, OS, TRAE, quality of life | June 10, 2026 |

| NCT04109092 [93] | E7766 (intravesical) | 110 | Multi-arm, dose escalation & expansion trial Arm 1 (dose escalation): MNIBC and BCG-unresponsive NMIBC Arm 2 (dose expansion): CIS with/without Ta or T1 Arm 3 (dose expansion) high-grade Ta or T1 without CIS |

I | DLTs, TRAE, CRR | September 29, 2022 |

| NCT02371447 [94] | VPM1002BC (intravesical) | 39 | Single-arm trial <Phase I> Induction (6 instillations) <Phase 2> Induction (6 instillations)+maintenance ( 3 instillation at 3, 6, and 12 months) |

I/II | DLTs, recurrence-free rate/ time to recurrence, time to progression, OS, TRAE, quality of life | December 31, 2022 |

| NCT02773849 [74,75] | Instiladrin (intravesical) | 157 | Single arm, open label study | III | CRR/DoR, EFS, durability of EFS, incidence of cystectomy, OS | August 31, 2022 |

| NCT02449239 (VISTA) [78] | Vicinium (intravesical) | 134 | Open-label, multicenter, single arm trial | III | CRR/recurrence rate, EFS, PFS, OS | November 2021 |

| NCT04452591 (BOND3) [95] | CG0070 (intravesical) | 110 | Global, single arm, open label study | III | CRR/DoR, PFS, cystectomy free OS, safety | December 2024 |

| NCT03711032 (KEYNOTE-676) [96] | Pembrolizumab (intravenous)+BCG | 550 | Randomized, comparator-controlled clinical trial Arm 1: BCG+pembrolizumab Arm 2: BCG alone |

III | CRR/EFS, RFS, OS, DSS, time to cystectomy, DoR, TRAE | November 25, 2024 |

| NCT04149574 [97] | Nivolumab (intravenous)+BCG | 700 | Randomized, double-blind trial Arm A (experimental): nivolumab+BCG Arm B (comparator): placebo+BCG |

III | EFS/WFS, OS, CRR, DoR, TRAE | August 16, 2030 |

BCG, bacillus Calmette–Guérin; NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; CRR, complete response rate; DFS, disease-free survival; DoR, duration of response; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; DLTs, dose-limiting toxicities; TRAE, treatment-related adverse events; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 protein ligand; PD-1, programmed cell death 1 protein; EBRT, external beam radiotherapy; RFS, recurrence-free survival; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; EFS, event-free survival; CIS, carcinoma in situ; MMC, mitomycin C; WFS, worsening-free survival; DSS, disease-specific survival.

2. Viral gene therapy (CG0070 and instiladrin/nadofaragene firadenovec)

Intravesical viral gene therapy occupies another frontier of immunotherapy for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. Oncolytic immunotherapy employs viruses that are designed to preferentially replicate in and lyse cancer cells, and trigger anti-tumor immunity in this process. Following the first description of a virus engineered to replicate selectively in cancer cells over 20 years ago, the field of oncolytic immunotherapy has expanded substantially [61]. CG0070 is an oncolytic adenovirus modified to include a human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) gene. CG0070 selectively replicates in retinoblastoma (Rb)-deficient cells, induces lysis and release of tumor-specific antigens, and induces local GM-CSF expression. This produces long-lasting antitumor immunity by activating antigen-presenting cells and, consequently, acting as an ‘in situ’ vaccine. In a phase I study of 35 patients with BCG-unresponsive disease, CG0070 therapy was correlated with a 48.6% response rate at a median duration of 10.4 months; patients with Rb-deficient tumors were likely to exhibit even higher response rates [70]. A recent interim analysis from the phase II BOND2 trial (NCT02365818), which included 45 patients with high-grade BCG-unresponsive disease who refused RC, reported that intravesical CG0070 yielded the CR rate of 50% in patients with CIS containing tumors (58% in pure CIS) at 6 months, with an acceptable level of toxicity [71]. The ongoing phase III BOND3 trial (NCT04452591) aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of intravesical CG0070 monotherapy in BCG-unresponsive settings (Table 4).

Another promising viral gene therapy is instiladrin (rAd-IFNα/Syn3, nadofaragene firadenovec), which is a replication-deficient recombinant adenovirus vector encoding IFNα-2b with anti-tumor activity. Instiladrin was investigated in a phase I trial of 17 patients with BCG-unresponsive disease, and a CR rate of 36% was observed at 12 months after intravesical instiladrin treatment [72]. A multi-center phase II trial (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01687244) including 40 BCG-unresponsive patients reported a CR rate at 3 months of approximately 57%, and 35% of patients maintained disease-free status up to 12 months [73]. An interim analysis of the results of a single arm phase III trial (NCT02773849) presented at the Society of Urologic Oncology (SUO) Meeting in December 2019 were recently published [74,75]. A total of 151 patients, consisting of 103 patients with CIS and 48 with papillary disease, were enrolled in this study. The efficacy results demonstrated that 53.4% of patients with CIS demonstrated a CR at 3 months, and 24.3% of patients maintained disease-free at 12 months after intravesical instiladrin treatment (Table 3) [74,75]. Even more favorable results were observed in patients with papillary-only disease (12-month CR rate of 43.8%).

3. Antibody-drug conjugates (vicinium/oportuzumab monatox)

ADCs are a novel therapeutic approach combining the high specificity of monoclonal antibodies with highly active cytotoxic agents. UC may be an optimal candidate for these drugs, because it expresses unique cell surface antigens that permit specific targeting of these cells. Enfortumab vedotin, an ADC consisting of a Nectin-4-directed antibody and microtubule inhibitor, recently became the first FDA-approved ADC for the treatment of mUC based on the results of the single-arm phase II EV-201 trial [76]. This ADC is also being studied in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC. Vicinium (oportuzumab monatox) is a recombinant fusion protein comprising a humanized anti-EpCAM (epithelial cell adhesion molecule) single-chain antibody linked to Pseudomonas exotoxin A. Vicinium was investigated in a phase II trial (NCT00462488) of 45 BCG-unresponsive CIS patients. The results demonstrated that 40% (18/45) of the enrolled patients exhibited a CR at 3 months after intravesical vicinium instillation, and the 12-month CR rate was 15.6%, with minimal treatment-related AEs [77]. Currently, a phase III VISTA trial (NCT02449239) is underway to confirm the efficacy and tolerability of intravesical vicinium in a larger number of similar BCG-unresponsive NMIBC patients (Table 4). An interim analysis results were presented at the 2020 AUA annual meeting [78]. In CIS patients (n=89) who recurred within 12 months after the last BCG treatment, intravesical vicinium resulted in CR rates of 40%, 28%, 17%, and 11% at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively [78]. More favorable results were observed for papillary-only tumors (n=38), with recurrence-free rates of 71%, 58%, 50%, and 37% at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively [78]. Further, vicinium was well-tolerated with only 52% of patients experiencing treatment-related AEs, the majority being grade 1–2 [78]. The favorable toxicity profile of ADC has led to several combination strategies, especially with checkpoint inhibitors. For instance, a phase I single-arm trial (NCT03258593) evaluating the combination of durvalumab, PD-L1 inhibitor, and vicinium in high-grade BCG-unresponsive NMIBC is currently ongoing (Table 4).

Table 3 summarizes the results of five representative novel therapeutic agents (pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, CG0070, instiladrin, and vicinium) recently investigated in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC patients. Although promising results have been reported, the small sample sizes of the studies are a limitation. Confirmation of these promising results in well-designed clinical trials with long follow-up periods and larger sample sizes will support the use of these drugs as salvage bladder-sparing treatments in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC patients in clinical practice.

4. Fibroblast growth factor receptor inhibitor (erdafitinib)

Erdafitinib is the pan-fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) kinase inhibitor approved by the FDA for second-line and beyond treatment in patients with mUC with susceptible FGFR3/2 alterations based on phase II BLC2001 trial results [79]. In that trial, the confirmed response rate to erdafitinib among all enrolled patients (n=99) was 40%. In patients who received previous ICI (n=22), the confirmed response rate was 59% [79]. Generally, patients with FGFR3 alterations exhibit lower responses to ICI, although FGFR3 alterations are correlated with a lower grade and stage of NMIBC and a favorable prognosis [80]. For these reasons, FGFR3 alterations are presumed to predict BCG responses. Results of a relevant trial were recently presented at the SUO meeting in December 2019. In 119 patients with high-grade NMIBC treated with intravesical BCG, FGFR3 alterations were identified in 51 of them (43%). Significant differences in high-grade recurrence free rates were observed between the FGFR3 alteration group and FGFR3 wild-type group (39% vs. 65%, p<0.05) over a median follow-up duration of 60 months. These results suggested that FGFR3-altered NMIBC portends high recurrence following BCG. As such, patients with NMIBC with these alterations may benefit from an alternative therapy with FGFR3 kinase inhibitors. Based on this hypothesis, a phase II clinical trial (NCT04172675) investigating the use of erdafitinib in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC is currently underway [81].

5. Ongoing clinical trials

Table 4 presents an overview of ongoing clinical trials for BCG-unresponsive NMIBC [82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97]. Current clinical studies in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC patients have mainly focused on the efficacy of the combination of various treatment modalities. Based on the efficacy observed in the KEYNOTE-057 trial [65], pembrolizumab is being investigated using combination approaches with intravesical use of BCG (NCT02808143) [82] and intravesical CG0070 [83] in phase I or II settings. Other ICIs including durvalumab, avelumab, atezolizumab, and nivolumab are being actively examined as monotherapies (intravenous or intravesical use) or as a part of combination approaches with various treatment modalities, such as radiotherapy, BCG, and intravesical ADC (vicinium) [84,85,86,87,88,89]. In particular, the results of clinical studies on the combination of intravenous ICI with intravesical viral gene therapy (pembrolizumab+CG0070) (NCT04387461, CORE1 trial) [83] or ADC (durvalumab+vicinium) (NCT03258593) [84] will reveal whether these combinations exert synergistic effects that increase the effectiveness of each treatment. In addition, several phase I and II trials testing intravesical multiple chemotherapy combinations (cabazitaxel, gemcitabine, and cisplatin) (NCT02202772) [90], PDT with TLD-1443 as a photosensitizer (NCT03945162) [91], and intravesical BCG and gemcitabine combination (NCT04179162) [92], are underway. The efficacy and safety of several other novel agents are being assessed in a phase I or II setting. These agents include oral erdafitinib (NCT04172675) [81], intravesical E7766 (NCT04109092) [93], which is an agonist of macrocycle-bridged stimulator of interferon genes (STING) protein, and VPM1002BC (modified mycobacterium BCG) (NCT02371447) [94]. Finally, five phase III clinical trials are in progress. These include the aforementioned studies on instiladrin (NCT02773849) [74,75], vicinium (VISTA trial, NCT02449239) [78], and CG0070 (BOND3 trial, NCT04452591) [95], and trials of intravesical BCG with intravenous pembrolizumab (NCT03711032) [96] or nivolumab (NCT04149574) [97]. The results of these phase III clinical studies will provide clearer evidence of the effectiveness of each treatment in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC patients.

CONCLUSIONS

BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, which is defined as BCG refractory or BCG relapse with high-risk NMIBC within 6 months or CIS development within 12 months from last BCG exposure, results in an increased risk of cancer progression and even death. Although RC is currently the recommended salvage option in BCG-unresponsive NMIBC, nonsurgical bladder-preserving strategies are required, given the high morbidity and mortality rates associated with RC. To date, many studies on various intravesical and systemic therapies have been conducted. In particular, systemic ICIs (pembrolizumab and atezolizumab), intravesical viral gene therapy (CG0070 and instiladrin), and intravesical vicinium may be considered novel standard non-surgical treatment options in patients with BCG-unresponsive high-risk NIMBC with CIS who are ineligible for or RC.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC-1810866).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors have nothing to disclose.

- Research conception and design: Ho Kyung Seo and Hyung Suk Kim.

- Data acquisition: Ho Kyung Seo and Hyung Suk Kim.

- Statistical analysis: Hyung Suk Kim.

- Data analysis and interpretation: Ho Kyung Seo and Hyung Suk Kim.

- Drafting of the manuscript: Hyung Suk Kim.

- Critical revision of the manuscript: Ho Kyung Seo.

- Obtaining funding: Ho Kyung Seo.

- Administrative, technical, or material support: Ho Kyung Seo and Hyung Suk Kim.

- Supervision: Ho Kyung Seo.

- Approval of the final manuscript: Ho Kyung Seo and Hyung Suk Kim.

References

- 1.Miranda-Filho A, Bray F, Charvat H, Rajaraman S, Soerjomataram I. The world cancer patient population (WCPP): an updated standard for international comparisons of population-based survival. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;69:101802. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2020.101802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Lee ES. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2016. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:417–430. doi: 10.4143/crt.2019.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamat AM, Hegarty PK, Gee JR, Clark PE, Svatek RS, Hegarty N, et al. ICUD-EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: screening, diagnosis, and molecular markers. Eur Urol. 2013;63:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamat AM, Hahn NM, Efstathiou JA, Lerner SP, Malmström PU, Choi W, et al. Bladder cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:2796–2810. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30512-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babjuk M, Burger M, Compérat EM, Gontero P, Mostafid AH, Palou J, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in situ) - 2019 update. Eur Urol. 2019;76:639–657. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang SS, Boorjian SA, Chou R, Clark PE, Daneshmand S, Konety BR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO guideline. J Urol. 2016;196:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flaig TW, Spiess PE, Agarwal N, Bangs R, Boorjian SA, Buyyounouski MK, et al. Bladder cancer, version 3.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:329–354. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young SL, Murphy M, Zhu XW, Harnden P, O'Donnell MA, James K, et al. Cytokine-modified Mycobacterium smegmatis as a novel anticancer immunotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:653–660. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jian W, Li X, Kang J, Lei Y, Bai Y, Xue Y. Antitumor effect of recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis expressing MAGEA3 and SSX2 fusion proteins. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:2160–2166. doi: 10.3892/etm.2018.6425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kadir NA, Acosta A, Sarmiento ME, Norazmi MN. Immunomodulatory effects of recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis expressing antigen-85B epitopes in infected J774A.1 murine macrophages. Pathogens. 2020;9:1000. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9121000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angelidou A, Conti MG, Diray-Arce J, Benn CS, Shann F, Netea MG, et al. Licensed Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) formulations differ markedly in bacterial viability, RNA content and innate immune activation. Vaccine. 2020;38:2229–2240. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sylvester RJ, van der MEIJDEN AP, Lamm DL. Intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin reduces the risk of progression in patients with superficial bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of the published results of randomized clinical trials. J Urol. 2002;168:1964–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemdan T, Johansson R, Jahnson S, Hellström P, Tasdemir I, Malmström PU. 5-Year outcome of a randomized prospective study comparing bacillus Calmette-Guérin with epirubicin and interferon-α2b in patients with T1 bladder cancer. J Urol. 2014;191:1244–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quhal F, D'Andrea D, Soria F, Moschini M, Abufaraj M, Rouprêt M, et al. Primary Ta high grade bladder tumors: determination of the risk of progression. Urol Oncol. 2021;39:132.e7–132.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamat AM, Colombel M, Sundi D, Lamm D, Boehle A, Brausi M, et al. BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive blad der cancer: recommendations from the IBCG. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:244–255. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shariat SF, Palapattu GS, Amiel GE, Karakiewicz PI, Rogers CG, Vazina A, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with carcinoma in situ only at radical cystectomy. Urology. 2006;68:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subiela JD, Rodríguez Faba O, Guerrero Ramos F, Vila Reyes H, Pisano F, Breda A, et al. Carcinoma in situ of the urinary bladder: a systematic review of current knowledge regarding detection, treatment, and outcomes. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6:674–682. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang DH, Chang SS. Management of carcinoma in situ of the bladder: best practice and recent developments. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7:351–364. doi: 10.1177/1756287215599694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarosdy MF, Lamm DL. Long-term results of intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin therapy for superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1989;142:719–722. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38865-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weizer AZ, Tallman C, Montgomery JS. Long-term outcomes of intravesical therapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol. 2011;29:59–71. doi: 10.1007/s00345-010-0617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein JP, Lieskovsky G, Cote R, Groshen S, Feng AC, Boyd S, et al. Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer: long-term results in 1,054 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:666–675. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yates DR, Rouprêt M. Failure of bacille Calmette-Guérin in patients with high risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer unsuitable for radical cystectomy: an update of available treatment options. BJU Int. 2010;106:162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinberg G, Bahnson R, Brosman S, Middleton R, Wajsman Z, Wehle M. Efficacy and safety of valrubicin for the treatment of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin refractory carcinoma in situ of the bladder. The Valrubicin Study Group. J Urol. 2000;163:761–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinney CP, Greenberg RE, Steinberg GD. Intravesical valrubicin in patients with bladder carcinoma in situ and contraindication to or failure after bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1635–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cookson MS, Chang SS, Lihou C, Li T, Harper SQ, Lang Z, et al. Use of intravesical valrubicin in clinical practice for treatment of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer, including carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Ther Adv Urol. 2014;6:181–191. doi: 10.1177/1756287214541798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barlow LJ, McKiernan JM, Benson MC. The novel use of intravesical docetaxel for the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer refractory to BCG therapy: a single institution experience. World J Urol. 2009;27:331–335. doi: 10.1007/s00345-009-0377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Addeo R, Caraglia M, Bellini S, Abbruzzese A, Vincenzi B, Montella L, et al. Randomized phase III trial on gemcitabine versus mytomicin in recurrent superficial bladder cancer: evaluation of efficacy and tolerance. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:543–548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Lorenzo G, Perdonà S, Damiano R, Faiella A, Cantiello F, Pignata S, et al. Gemcitabine versus bacille Calmette-Guérin after initial bacille Calmette-Guérin failure in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a multicenter prospective randomized trial. Cancer. 2010;116:1893–1900. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solsona E, Madero R, Chantada V, Fernandez JM, Zabala JA, Portillo JA, et al. Sequential combination of mitomycin C plus bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is more effective but more toxic than BCG alone in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in intermediate- and high-risk patients: final outcome of CUETO 93009, a randomized prospective trial. Eur Urol. 2015;67:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cockerill PA, Knoedler JJ, Frank I, Tarrell R, Karnes RJ. Intravesical gemcitabine in combination with mitomycin C as salvage treatment in recurrent non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2016;117:456–462. doi: 10.1111/bju.13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milbar N, Kates M, Chappidi MR, Pederzoli F, Yoshida T, Sankin A, et al. Oncological outcomes of sequential intravesical gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2017;3:293–303. doi: 10.3233/BLC-170126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mmeje CO, Guo CC, Shah JB, Navai N, Grossman HB, Dinney CP, et al. Papillary recurrence of bladder cancer at first evaluation after induction bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy: implication for clinical trial design. Eur Urol. 2016;70:778–785. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamm DL, Blumenstein BA, Crissman JD, Montie JE, Gottesman JE, Lowe BA, et al. Maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guerin immunotherapy for recurrent TA, T1 and carcinoma in situ transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol. 2000;163:1124–1129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hinotsu S, Akaza H, Naito S, Ozono S, Sumiyoshi Y, Noguchi S, et al. Maintenance therapy with bacillus Calmette-Guérin Connaught strain clearly prolongs recurrence-free survival following transurethral resection of bladder tumour for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2011;108:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu S, Tang Y, Li K, Shang Z, Jiang N, Nian X, et al. Optimal schedule of bacillus calmette-guerin for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:332. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guallar-Garrido S, Julián E. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy for bladder cancer: an update. Immunotargets Ther. 2020;9:1–11. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S202006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oddens J, Brausi M, Sylvester R, Bono A, van de Beek C, van Andel G, et al. Final results of an EORTC-GU cancers group randomized study of maintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin in intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the urinary bladder: one-third dose versus full dose and 1 year versus 3 years of maintenance. Eur Urol. 2013;63:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamat AM, Sylvester RJ, Böhle A, Palou J, Lamm DL, Brausi M, et al. Definitions, end points, and clinical trial designs for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: recommendations from the International Bladder Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1935–1944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.4070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herr HW, Sogani PC. Does early cystectomy improve the survival of patients with high risk superficial bladder tumors? J Urol. 2001;166:1296–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raj GV, Herr H, Serio AM, Donat SM, Bochner BH, Vickers AJ, et al. Treatment paradigm shift may improve survival of patients with high risk superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 2007;177:1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.090. discussion 1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrier BP, Hollander MP, van Rhijn BW, Kiemeney LA, Witjes JA. Prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer: difference between primary and progressive tumours and implications for therapy. Eur Urol. 2004;45:292–296. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breau RH, Karnes RJ, Farmer SA, Thapa P, Cagiannos I, Morash C, et al. Progression to detrusor muscle invasion during urothelial carcinoma surveillance is associated with poor prognosis. BJU Int. 2014;113:900–906. doi: 10.1111/bju.12403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stimson CJ, Chang SS, Barocas DA, Humphrey JE, Patel SG, Clark PE, et al. Early and late perioperative outcomes following radical cystectomy: 90-day readmissions, morbidity and mortality in a contemporary series. J Urol. 2010;184:1296–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hounsome LS, Verne J, McGrath JS, Gillatt DA. Trends in operative caseload and mortality rates after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer in England for 1998-2010. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1056–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalbagni G, Russo P, Bochner B, Ben-Porat L, Sheinfeld J, Sogani P, et al. Phase II trial of intravesical gemcitabine in bacille Calmette-Guérin-refractory transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2729–2734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skinner EC, Goldman B, Sakr WA, Petrylak DP, Lenz HJ, Lee CT, et al. SWOG S0353: Phase II trial of intravesical gemcitabine in patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer and recurrence after 2 prior courses of intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J Urol. 2013;190:1200–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laudano MA, Barlow LJ, Murphy AM, Petrylak DP, Desai M, Benson MC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of a phase I trial of intravesical docetaxel in the management of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer refractory to standard intravesical therapy. Urology. 2010;75:134–137. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barlow LJ, McKiernan JM, Benson MC. Long-term survival outcomes with intravesical docetaxel for recurrent nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer after previous bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. J Urol. 2013;189:834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKiernan JM, Holder DD, Ghandour RA, Barlow LJ, Ahn JJ, Kates M, et al. Phase II trial of intravesical nanoparticle albumin bound paclitaxel for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder after bacillus Calmette-Guérin treatment failure. J Urol. 2014;192:1633–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steinberg RL, Thomas LJ, Brooks N, Mott SL, Vitale A, Crump T, et al. Multi-institution evaluation of sequential gemcitabine and docetaxel as rescue therapy for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2020;203:902–909. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hendricksen K. Device-assisted intravesical therapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2019;8:94–100. doi: 10.21037/tau.2018.09.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nativ O, Witjes JA, Hendricksen K, Cohen M, Kedar D, Sidi A, et al. Combined thermo-chemotherapy for recurrent bladder cancer after bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J Urol. 2009;182:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arends TJ, Nativ O, Maffezzini M, de Cobelli O, Canepa G, Verweij F, et al. Results of a randomised controlled trial comparing intravesical chemohyperthermia with mitomycin C versus bacillus Calmette-Guérin for adjuvant treatment of patients with intermediate- and high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2016;69:1046–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chien YW, Banga AK. Iontophoretic (transdermal) delivery of drugs: overview of historical development. J Pharm Sci. 1989;78:353–354. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600780502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Stasi SM, Giannantoni A, Giurioli A, Valenti M, Zampa G, Storti L, et al. Sequential BCG and electromotive mitomycin versus BCG alone for high-risk superficial bladder cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:43–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70472-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Racioppi M, Di Gianfrancesco L, Ragonese M, Palermo G, Sacco E, Bassi PF. ElectroMotive drug administration (EMDA) of Mitomycin C as first-line salvage therapy in high risk “BCG failure” non muscle invasive bladder cancer: 3 years follow-up outcomes. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1224. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5134-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nseyo UO, Shumaker B, Klein EA, Sutherland K. Photodynamic therapy using porfimer sodium as an alternative to cystectomy in patients with refractory transitional cell carcinoma in situ of the bladder. Bladder Photofrin Study Group. J Urol. 1998;160:39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bader MJ, Stepp H, Beyer W, Pongratz T, Sroka R, Kriegmair M, et al. Photodynamic therapy of bladder cancer - a phase I study using hexaminolevulinate (HAL) Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1178–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JY, Diaz RR, Cho KS, Lim MS, Chung JS, Kim WT, et al. Efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy for recurrent, high grade nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer refractory or intolerant to bacille Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy. J Urol. 2013;190:1192–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Railkar R, Agarwal PK. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of bladder cancer: past challenges and current innovations. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;4:509–511. doi: 10.1016/j.euf.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sathianathen NJ, Regmi S, Gupta S, Konety BR. Immunooncology approaches to salvage treatment for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 2020;47:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2019.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim HS, Seo HK. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for urothelial carcinoma. Investig Clin Urol. 2018;59:285–296. doi: 10.4111/icu.2018.59.5.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukumoto K, Kikuchi E, Mikami S, Hayakawa N, Matsumoto K, Niwa N, et al. Clinical role of programmed cell death-1 expression in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer recurring after initial bacillus Calmette-Guérin therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2484–2491. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kates M, Matoso A, Choi W, Baras AS, Daniels MJ, Lombardo K, et al. Adaptive immune resistance to intravesical BCG in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: implications for prospective BCG-unresponsive trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:882–891. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Balar AV, Kulkarni GS, Uchio EM, Boormans J, Mourey L, Krieger LEM, et al. Keynote 057: Phase II trial of Pembrolizumab (pembro) for patients (pts) with high-risk (HR) nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) unresponsive to bacillus calmette-guérin (BCG) J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7 Suppl):350 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Black PC, Tangen C, Singh P, McConkey DJ, Lucia S, Lowrance WT, et al. Phase II trial of atezolizumab in BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: SWOG S1605 (NCT #02844816) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(15 Suppl):5022 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim J, Kwiatkowski D, McConkey DJ, Meeks JJ, Freeman SS, Bellmunt J, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas expression subtypes stratify response to checkpoint inhibition in advanced urothelial cancer and identify a subset of patients with high survival probability. Eur Urol. 2019;75:961–964. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song BN, Kim SK, Mun JY, Choi YD, Leem SH, Chu IS. Identification of an immunotherapy-responsive molecular subtype of bladder cancer. EBioMedicine. 2019;50:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Zhang Q, Shuman L, Kaag M, Raman JD, Merrill S, et al. Evaluation of PD-L1 and other immune markers in bladder urothelial carcinoma stratified by histologic variants and molecular subtypes. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1439. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58351-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burke JM, Lamm DL, Meng MV, Nemunaitis JJ, Stephenson JJ, Arseneau JC, et al. A first in human phase 1 study of CG0070, a GM-CSF expressing oncolytic adenovirus, for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:2391–2397. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Packiam VT, Lamm DL, Barocas DA, Trainer A, Fand B, Davis RL, 3rd, et al. An open label, single-arm, phase II multicenter study of the safety and efficacy of CG0070 oncolytic vector regimen in patients with BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: interim results. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dinney CP, Fisher MB, Navai N, O'Donnell MA, Cutler D, Abraham A, et al. Phase I trial of intravesical recombinant adenovirus mediated interferon-α2b formulated in Syn3 for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin failures in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2013;190:850–856. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shore ND, Boorjian SA, Canter DJ, Ogan K, Karsh LI, Downs TM, et al. Intravesical rAd-IFNα/Syn3 for patients with high-grade, bacillus Calmette-Guerin-refractory or relapsed non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a phase II randomized study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3410–3416. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Boorjian SA, Dinney CPN SUO Clinical Trials Consortium. Safety and efficacy of intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec for patients with high-grade, BCG unresponsive nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC): results from a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6 Suppl):442 [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boorjian SA, Alemozaffar M, Konety BR, Shore ND, Gomella LG, Kamat AM, et al. Intravesical nadofaragene firadenovec gene therapy for BCG-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a single-arm, open-label, repeat-dose clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:107–117. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30540-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenberg JE, O'Donnell PH, Balar AV, McGregor BA, Heath EI, Yu EY, et al. Pivotal trial of enfortumab vedotin in urothelial carcinoma after platinum and anti-programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:2592–2600. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kowalski M, Guindon J, Brazas L, Moore C, Entwistle J, Cizeau J, et al. A phase II study of oportuzumab monatox: an immunotoxin therapy for patients with noninvasive urothelial carcinoma in situ previously treated with bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J Urol. 2012;188:1712–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shore N, O'Donnell M, Keane T, Jewett MAS, Kulkarni GS, Dickstein R, et al. PD03-02 Phase 3 results of Vicinium in BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. J Urol. 2020;203(4 Suppl):e72 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, Garcia-Donas J, Huddart R, Burgess E, et al. Erdafitinib in locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:338–348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kacew A, Sweis RF. FGFR3 alterations in the era of immunotherapy for urothelial bladder cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575258. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.575258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steinberg GD, Palou-Redorta J, Gschwend JE, Tran B, Loriot Y, Daneshmand S, et al. A randomized phase II study of erdafitinib (ERDA) versus intravesical chemotherapy (IC) in patients with high-risk nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (HR-NMIBC) with FGFR mutations or fusions, who recurred after Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(6 Suppl):TPS603 [Google Scholar]

- 82.US National Library of Medicine. A phase 1 dose-escalation study of intravesical MK-3475 and bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) in subjects with high risk and BCG-refractory non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2016. Jun 21, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02808143. [Google Scholar]

- 83.US National Library of Medicine. A phase 2, single arm study of CG0070 combined with pembrolizumab in patients with non muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) unresponsive to bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2020. May 13, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04387461. [Google Scholar]

- 84.US National Library of Medicine. A phase I single-arm study of the combination of durvalumab (MEDI4736) and vicinium (oportuzumab monatox, VB4-845) in subjects with high-grade non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer previously treated with bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2017. Aug 23, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03258593. [Google Scholar]

- 85.US National Library of Medicine. Phase 1/2 study of modern immunotherapy in BCG-relapsing urothelial carcinoma of the bladder - (ADAPT-BLADDER) HCRN GU16-243 [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2017. Oct 23, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03317158. [Google Scholar]

- 86.US National Library of Medicine. Intravesical administration of durvalumab (MEDI4736) to patients with high-risk, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). A phase II study with correlative [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2018. Nov 30, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03759496. [Google Scholar]

- 87.US National Library of Medicine. Bladder preservation by radiotherapy and immunotherapy in BCG unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (PREVERT) [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2019. May 15, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03950362. [Google Scholar]

- 88.US National Library of Medicine. Phase II trial of atezolizumab in BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2016. Jul 26, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02844816. [Google Scholar]

- 89.US National Library of Medicine. A phase 2, randomized, open-label study of nivolumab or nivolumab/BMS-986205 alone or combined with intravesical BCG in participants With BCG-unresponsive, high-risk, non-muscle invasive bladder cancer [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2018. May 08, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03519256. [Google Scholar]

- 90.US National Library of Medicine. A phase I trial for the use of intravesical cabazitaxel, gemcitabine, and cisplatin (CGC) in the treatment of BCG-refractory non-muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder cancer [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2014. Jul 29, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02202772. [Google Scholar]

- 91.US National Library of Medicine. A phase II clinical study of intravesical photodynamic therapy in patients with BCG-unresponsive non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (“NMIBC”) or patients who are intolerant to BCG therapy (“Study”). [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2019. May 10, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03945162. [Google Scholar]

- 92.US National Library of Medicine. Phase I/II trial of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and intravesical gemcitabine for patients with BCG-relapsing high-grade non-muscle invasive bladder cancer [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2019. Nov 27, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04179162. [Google Scholar]

- 93.US National Library of Medicine. Intravesical phase 1/1b study of STING agonist E7766 in NMIBC including subjects unresponsive to BCG therapy, INPUT-102 [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2019. Sep 30, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04109092. [Google Scholar]

- 94.US National Library of Medicine. A phase I/II open label clinical trial assessing safety and efficacy of intravesical instillation of VPM1002BC in patients with recurrent non-muscle invasive bladder cancer after standard BCG therapy [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2015. Feb 25, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02371447. [Google Scholar]

- 95.US National Library of Medicine. A phase 3 study of CG0070 in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) unresponsive to bacillus-Calmette-Guerin (BCG) [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2020. Jun 30, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04452591. [Google Scholar]

- 96.US National Library of Medicine. A phase 3, randomized, comparator-controlled clinical trial to study the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in combination with bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) in participants with high-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (HR NMIBC) that is either persistent or recurrent following BCG induction or that is naïve to BCG treatment (KEYNOTE-676) [Internet] Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine; 2018. Oct 18, [cited 2020 Oct 31]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03711032. [Google Scholar]