Key summary points

Aim

The aims of this study were to describe communication experiences while wearing a mask during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, to identify possible mask-related barriers to COVID-19-adapted communications and to investigate whether the ABC mnemonic (A: Attend Mindfully; B: Behave Calmly; C: Communicate Clearly) might address these.

Findings

The majority of the respondents indicated issues related to lack of time during clinical encounters, uncertainty about how to adapt communication, lack of personal protective equipment, lack of communication skills and lack of information about how to adapt their own communication skills. In addition, the participants indicated acknowledging emotions and providing information using clear, specific, unambiguous, and consistent lay language while wearing a mask were among the main communication challenges created during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the study showed significantly improved self-perceived competency regarding key communication after watching the short video presentation.

Message

Effective communication in medical encounters must utilize on both verbal and nonverbal skills.

Keywords: Communication, COVID-19, Older adults, Training

Abstract

Purpose

The aims of this study were to describe communication experiences while wearing a mask during COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, to identify possible mask-related barriers to COVID-19-adapted communications and to investigate whether the ABC mnemonic (A: attend mindfully; B: behave calmly; C: communicate clearly) might address these.

Methods

This study was a cross-sectional, voluntary, web-based survey between January and February 2021. A 22-item survey was developed using the Surveymonkey platform and question styles were varied to include single choice and Likert scales. The respondents were also asked to view a short video presentation, which outlined the ABC mnemonic. CHERRIES (Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys) was used to ensure completeness of reporting. Diverging stacked bar charts were created to illustrate Likert scale responses.

Results

We received 226 responses. The respondents were mostly women (60.2%) and the majority worked in a teaching hospital (64.6%). The majority of the respondents indicated issues related to lack of time during clinical encounters, uncertainty about how to adapt communication, lack of personal protective equipment, lack of communication skills and lack of information about how to adapt their own communication skills. In addition, the participants indicated acknowledging emotions and providing information using clear, specific, unambiguous, and consistent lay language while wearing a mask were among the main communication challenges created during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the study showed significantly improved self-perceived competency regarding key communication after watching the short video presentation.

Conclusion

Effective communication in medical encounters requires both verbal and nonverbal skills.

Introduction

Caring for older adults requires skillful communication: delivering bad news [1], supporting a patient through periods of functional or cognitive decline, and establishing appropriate goals of care in the setting of serious or life-threatening illness. These issues are made more challenging by cognitive and sensory impairment among older patients and the frequent need, therefore, to communicate with families as proxies or intermediaries. The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has created a global health crisis that has had a deep impact on the way we communicate with patients and their relatives in all care settings because of the need to maintain isolation and social distancing and the widespread use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), which muffles sounds and hides non-verbal expression [2]. Health care professionals around the globe are confronted with new communication tasks including proactive care planning for patients who are already frail, including conducting often delicate conversations around end-of-life either through masks or electronic media [3].

High-quality patient-clinician communication is associated with reduced patient anxiety and enhances patients' trust, satisfaction, and adherence with treatment while poor communication is associated with increased patient anxiety and depression [4]. Communication skills reflecting respect and empathy can be taught and learned by healthcare professionals [5]. However, training in advanced communication skills is generally a high-intensity endeavor, facilitated in classes with low student–teacher ratios, often using recordings to observe desired behaviors and role-play to practice them [5].

The communication challenges raised by COVID-19 were sufficiently novel that they were not covered by existing training, whilst the pandemic meant that in-person training sessions to address this were largely infeasible. One successful approach to educating diverse health care professionals is the use of internet-based teaching [6, 7]. Web-based manuals on how to tailor communication to the needs of patients with COVID-19 have been developed for example by VitalTalk and the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland [8]. We recently produced an “ABC mnemonic” to improve communication when wearing facemasks, especially during communication with older patients or with those with cognitive impairment [9]. In detail, the letter A stands for “attend mindfully” to the situation, e.g. reflecting on the asymmetries of the encounter and remembering the typical communication style—with all of its gestures, tones, and warmth and preparing to use those nonverbal cues during the interaction. The letter B stands for “behave calmly” throughout the encounter, especially for those with cognitive and physiologic barriers, approaching from the front, bending down to eye level, and ensuring that you can be heard in spite of the PPE barrier. The letter C stands for “communicate clearly” with the patient by employing the gestures true to your typical style, keeping your voice even, and sympathetically mirroring the gestures and tone of the older adult."

We aimed this survey to describe healthcare professionals’ communication experiences in relation to managing older patients while wearing a mask during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, to understand possible barriers for COVID-19-adapted communication strategies while wearing a mask and to investigate what role the ABC mnemonic might play in overcoming these.

Methods

Survey development

An online survey was developed using the Surveymonkey platform (Surveymonkey® San Mateo, CA). The survey was built de novo by one author (MS) based on expertise and previous research in the field [1]. Input for content validity and comprehensibility was sought from research and clinical peers (KS, NM, AG). Survey planning and administration were reported as per the “Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys” (CHERRIES) [10]. The survey was iteratively revised and pilot-tested prior to administration to the target sample. The resulting questionnaire comprised five sections headed: demographics; overall experiences communicating through a mask; communication challenges during COVID-19; effective health communication; and mindful communication. Question-styles were varied to include single choice and Likert scales. Participants were prompted to complete questions before clicking through to the next section. A back arrow was present on all pages to enable participants to revisit and change a response if needed. Before completing the survey, the respondents were asked to view a 13 min presentation entitled “Communication during COVID-19 Pandemic” [11], which outlined the ABC mnemonic. The survey closed with an open question, which enabled informal free-text comment. We considered responses received between January 06, 2021, and February 05, 2021.

Ethics procedures

As the study only involved professionals and referred to an educational improvement initiative with expert health care professionals as participants, it did not raise any of the ethical issues flagged by the European Commission in the Horizon 2020 Programme Guidance “How to complete your ethics self-assessment” [12]. Therefore, ethics approval by an ethics review board/committee was deemed not to be necessary. This study fully complies with ethical principles, relevant EU, and international legislation [13] including the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights [14]. Data were stored in a database on a password-protected computer as an encrypted file. Due to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this database is not openly available. No personal information was collected.

Population selection

The survey was promoted by a blog “Communicating through a mask: Learning from the collective experience during COVID-19” [15] from the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) and disseminated over the social media platforms of the BGS and individual accounts of the authors (Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp). The main BGS e-Bulletin is sent to all subscribers and members interested in geriatric medicine, which currently stands at around 4400 healthcare professionals. The European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS), is the collaborating and coordinating organization of the national geriatric medical societies of the European Union member states, but also includes Switzerland. Starting January 22nd 2021, the survey was also highlighted by the EuGMS (European Geriatric Medicine Society) [16]. Checking IP addresses for duplication of responses was not performed to maintain privacy and anonymity of respondents. We considered responses received between January 06, 2021, and February 05, 2021.

Statistical analysis

Categorical data were reported as frequencies and percentages. Associations between categorical data were assessed using the Chi squared test. Diverging stacked bar charts were created to illustrate Likert scale responses [17]. In these, shorter bar segments indicate a lower frequency of respondents and vice versa [18]. All statistics were performed using XLSTAT—life sciences, Adinsoft, France, 2020. The level of statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

We received responses from 226 health care professionals. Mean question completion rate per questionnaire was 87.0%. Participants’ characteristics are described in Table 1. The majority of respondents were women (60.82%) and work settings included in a teaching hospital (64.6%), in multiple settings (11.5%) or in an urban non-teaching setting (9.7%). Most respondents came from Europe or North America, with healthcare professionals from UK and Switzerland being most prevalent in the sample.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Total (N = 226) 100% | Female (N = 136) 60.2% | Male (N = 90) 39.8% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | |||

| 20–30 | (33) 14.6 | (21) 15.4 | (12) 13.3 |

| 31–40 | (82) 36.3 | (47) 34.6 | (35) 38.9 |

| 41–50 | (67) 29.7 | (41) 30.2 | (26) 28.9 |

| 51–60 | (31) 13.7 | (23) 16.9 | (8) 8.9 |

| > 60 | (13) 5.8 | (4) 2.9 | (9) 10 |

| Main practice setting | |||

| Teaching hospital | (146) 64.6 | ||

| Urban non-teaching | (22) 9.7 | ||

| Community teaching | (8) 3.5 | ||

| Community non-teaching | (20) 8.9 | ||

| Rural | (4) 1.8 | ||

| Multiple settings | (26) 11.5 | ||

| Healthcare discipline | |||

| Medical health care workers | (155) 68.6 | ||

| Consultant geriatrician | (79) 35 | ||

| Specialty consultant | (44) 19.5 | ||

| Non consultant career grade | (5) 2.2 | ||

| Junior doctor | (20) 8.9 | ||

| Old age psychiatrist | (5) 2.2 | ||

| General practitioner | (2) 0.9 | ||

| Nurses | (23) 10.2 | ||

| Specialist nurse in geriatrics | (9) 3.9 | ||

| ANP/ACP | (11) 5.3 | ||

| Acute medical unit nursing staff | (2) 0.9 | ||

| Other health care workers | (48) 21.2 | ||

| Physiotherapy | (4) 1.8 | ||

| Occupational therapy | (7) 3.1 | ||

| Therapy assistant | (4) 1.8 | ||

| Dietician | (3) 1.3 | ||

| Care assistance | 0 | ||

| Not sure | (1) 0.4 | ||

| Other | (29) 12.8 | ||

| Country | |||

| Switzerland | (59) 26.1 | ||

| United Kingdom | (54) 23.9 | ||

| United States of America | (18) 8 | ||

| Turkey | (14) 6.2 | ||

| Spain | (13) 5.8 | ||

| Italy | (11) 4.9 | ||

| France | (8) 3.5 | ||

| Canada | (5) 2.2 | ||

| Russia | (5) 2.2 | ||

| Belgium | (4) 1.8 | ||

| Germany | (4) 1.8 | ||

| Finland | (3) 1.3 | ||

| Israel | (3) 1.3 | ||

| Norway | (3) 1.3 | ||

| Othera | (23) 10.2 |

aOther countries: Australia, China, Czech Republic, Ireland, Peru, Poland, Austria, Brazil, Denmark, India, Malta, Philippines, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sweden

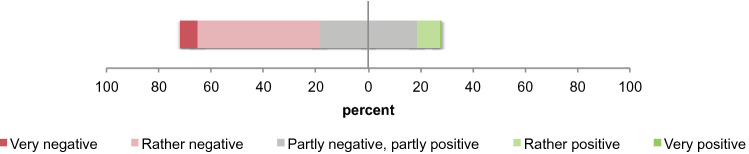

Overall experience communicating through a mask

As shown in Fig. 1, the majority of the respondents (n = 222; 98.2%) rated their overall experience communicating with their patients and their families through a mask rather negative (46.4%) and partly negative/partly positive (37.3%) without a significant difference in gender (p = 0.670), healthcare discipline (p = 0.373) and age (p = 0.890).

Fig. 1.

Overall experience communicating through a mask. For this question, the respondents (n = 222) answered the following question: "How do you rate your overall experience communicating with your patients and their families through a mask?" Percentages of participants for this question are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 5 levels of agreement from very negative to very positive. Neutral opinion is in gray, negative experiences are in red and positive experiences are in green. The more the experience was intense, the more the color is dark

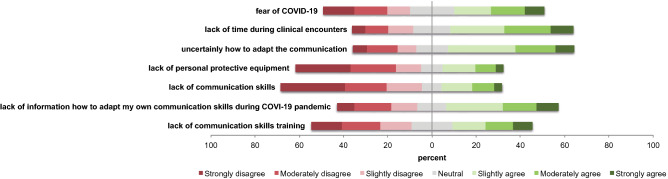

Communication challenges due to COVID-19

As shown in Fig. 2, the majority of the respondents (n = 210; 93.0%) indicated issues related to lack of time during clinical encounters, uncertainty about how to adapt communication, lack of personal protective equipment, lack of communication skills, and lack of information about how to adapt their own communication skills during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a significant association between uncertainty about how to adapt communication to the pandemic and gender (p = 0.021). Furthermore, younger respondents were more likely to express problems around lack of communication training (p = 0.031).

Fig. 2.

Communication challenges to take account of COVID-19. For this question, the respondents (n = 210) answered the following question: "What challenged your communication strategy to take account of COVID-19?" Percentages of participants for each question (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. Questions have been sorted into two classes: working conditions (fear of COVID-19, lack of time during clinical encounters, lack of personal protective equipment) and communication with own perceived barriers (uncertainly how to adapt the communication, lack of communication skills) and external barriers (lack of information how to adapt my own communication skills during COVID-19 pandemic, lack of communication skills training)

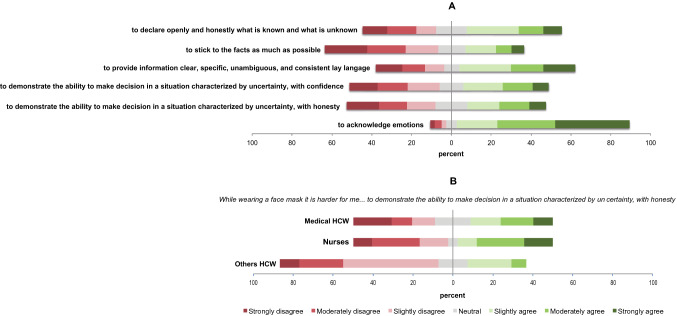

Effective health communication

As shown in Fig. 3A, the majority of the respondents indicated that wearing a mask makes it harder to acknowledge emotions and to provide information using clear, specific, unambiguous, and consistent lay language. There were no significant differences by gender and age. However, there was a significant difference (p = 0.040) between the different health care disciplines, with professions allied to medicine indicating less difficulty making a decision in a situation characterized by uncertainty, with honesty (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effective health communication. A Effective health communication. For this question, the respondents (n = 208) answered the following question: "While wearing a face mask it is harder for me…". Percentages of participants for each question (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. B Effective health communication by health care discipline. For this question, the respondents (n = 208) answered the following question: "While wearing a face mask it is harder for me…to demonstrate the ability to make decision in a situation characterized by uncertainty, with honesty". Percentages of participants for each health care worker category (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. HCW health care worker

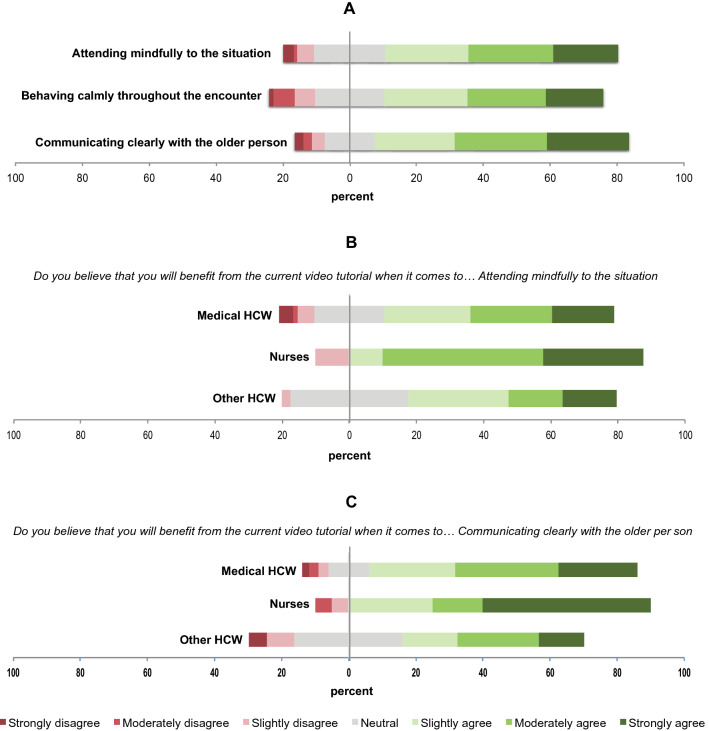

Self-perception of communication skills

As shown in Fig. 4A, the majority of the respondents indicated that their communication would benefit from using the ABC-protocol [9]. Differences were noted between the different health care disciplines regarding the relative merits of the ABC-protocol [9] when it comes to attending mindfully to the situation (p = 0.039) (Fig. 4B) and communicating clearly (p = 0.008) (Fig. 4C) with the older person.

Fig. 4.

Self-perception of communication skills. A Self-perception of communication skills. For this question, the respondents (n = 197) answered the following question: "Do you believe that you will benefit from the current video tutorial when it comes to…". Percentages of participants for each question (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. B Self-perception of communication skills by health care discipline—attending mindfully to the situation. For this question, the respondents (n = 197) answered the following question: "Do you believe that you will benefit from the current video tutorial when it comes to… attending mindfully to the situation". Percentages of participants for each health care worker category (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. HCW health care worker. C Self-perception of communication skills by health care discipline—communicating clearly. For this question, the respondents (n = 197) answered the following question: "Do you believe that you will benefit from the current video tutorial when it comes to… communicating clearly with the older person". Percentages of participants for each health care worker category (described in the left strip label) are represented in diverging stacked bar charts in accordance with a Likert scale 7 levels of agreement from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Neutral opinion is in gray, disagreement is in red and agreement is in green. The more the level of disagreement or agreement is important, the more the color is dark. HCW health care worker

Discussion

This study describes the self-perceived competency of health care professionals regarding key communication skills during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main findings are that challenges during the pandemic influenced the ability of healthcare professionals from medicine, nursing, and allied health professional backgrounds to communicate clearly and unambiguously. A majority of participants related this challenge to a lack of specific training and competencies in how to adapt communication skills to work through PPE in the context of social distancing. Respondents were positive about the way in which the ABC mnemonic might improve their communication skills.

That professionals found their communication competencies challenged by PPE and social distancing likely reflects that most were taught to communicate according to societal norms before the pandemic. Previous research has described how healthcare professionals use touch to share emotions, demonstrate empathy and presence to patients [19]. Recently, Saunders and colleagues performed a survey of 460 members of the general public in the UK around the time face coverings were becoming common, but before their use was mandatory. Respondents reported that face coverings affected the content of communication, feelings of interpersonal connection, and willingness to engage in conversation and that they had strong negative impacts on anxiety levels, stress, and self-confidence. They also reported that face coverings made communication fatiguing, frustrating, and embarrassing [20]. Before the pandemic, most healthcare professionals were taught to use both non-verbal facial expression and touch as part of communication routines and lacked training to adapt these to the use of masks and minimized physical contact.

We did note differences in response by gender and age. One potential explanation is that the underlying communication styles of men and women inherently differ, requiring different adaptations. It is also possible that younger clinicians’ increased experience and comfort with communicating over digital platforms lessened the need to adapt. Due to the scarce literature on this particular topic, it is difficult to elaborate whether the differences by gender and age are replicated elsewhere. However, the effect of masks on physician–patient interactions was examined in a large 2013 study performed in Hong Kong in primary care to explore the effects of doctors wearing facemasks on patients’ perception of doctors’ empathy, patient enablement, and patient satisfaction. The authors found that the wearing of facemasks by doctors had a significant and negative effect on patients’ perceptions of the doctors’ empathy without a difference by gender and age [21]. Recently, Kratzke and colleagues performed a randomized clinical trial in 200 patients examining communication between surgeons and their patients when surgeons wore clear vs covered masks in surgical outpatient clinics. Surgeons who wore clear masks were perceived by patients to be better communicators, have more empathy, and elicit greater trust [22]. For this study, differences by gender and age were not reported.

There was consistency in respondents across professional backgrounds and countries with regard to the types of challenges described. Most respondents felt that the content of the video teaching provided toward the end of the study, outlining the ABC mnemonic, would help them structure their communications in a way that was more mindful of the barriers to communication encountered during the pandemic. It is often the case in the pedagogical literature that respondents will rate “some teaching” better than “no teaching” though bad teaching can be resented or viewed as time wasted. The overall positive response to the video was reassuring and clinicians did not indicate that it was time badly spent. The internet can be an effective platform to disseminate information about health and health care, enhance communication, and facilitate a wide range of interactions between health care professionals and the health care delivery system, especially during the pandemic when short, focused teaching interventions can have an impact. In terms of the Kirkpatrick model of training evaluation [23], these findings provide evidence of positive reaction to the model and associated training materials—we need now to show that exposure to the materials results in learning, and ultimately in changes to behavior and outcomes for patients and the staff that care for them. Given the positive findings here, we propose a more focused evaluation to understand whether these benefits on outcomes can be realized.

From a clinical point of view, several questions addressing communication challenges during the COVID-19 era remain open, especially when it comes to communications with older patients while wearing PPE.

First, if and to what extend communicating behind a mask contributes to the stress, anxiety, social isolation, and psychological distress caused by the pandemic and the lockdown measures [24]. Second, in addition to minimizing psychological distress, maximizing patient recall and comprehension of diagnostic and prognostic information is an important goal. Patients need to understand the novel and often-complicated medical information provided by their physician if they are to participate in decision-making about their own care [25]. Our current clinical impression is that the level of comprehension especially in older adults is lower as compared to the pre-COVID-19 era. Finally, will there be a change in patient preferences? For example, patients have generally reported wanting their doctors to be empathic and supportive [26], to use simple language, and to allow plenty of time for questions [27]. With facemasks restricting how staff and patients express emotion and use non-verbal communication, there might be a need for an adaption of communication practices.

The strengths of this work include a high number of responses, comprising healthcare professionals from multiple countries, professional backgrounds, and levels of experience. This study provides a useful insight into clinicians’ experiences communicating during the pandemic and enabled us to evaluate the reaction of diverse participants to one possible training resource. The main limitation relates to the bias in the sample towards European countries and North America, and to particular countries within Europe, which limit the generalizability of the findings beyond these settings. The voluntary nature of the survey invariable includes selection bias. What biases this may have introduced are difficult to speculate but it could, for example, have selected less-clinically busy staff due to being less actively clinically deployed or selected those who had faced particular difficulties with communication in their roles and felt motivated to respond. Taken, however, as a signal of communication difficulties during the pandemic and a marker of staff desire, across multiple countries and professional groupings, to improve their communication strategies to take account of COVID, this work represents a meaningful contribution to our understanding.

With these results firmly in mind, this study hereby shows that, although extensive in-person training is the standard, the current approach is feasible. It also reaffirms that effective communication in medical encounters must capitalize on both verbal and nonverbal aspects, which must be valued during and after the current crisis. Finally, it highlights the need for innovative communication skills courses to be shared between services, and for national guidance or toolkits to support services interested in this work. The current pandemic has created unique challenges in providing traditional in person care. The traditional practice of medicine is not easily reconfigured and adjusting to the communicating while wearing personal protective equipment will take time. Given the success of treatment under these circumstances, clinicians need to prepare for protective measures continuing for an indeterminate amount of time and be aware of how they influences communication with patients. Person centered care should respect and act upon older adults ‘needs and preferences and ensure patients’ values guide care decisions [28]. Creating an environment for successful communication [29], speech modification strategies, supplemental communication methods (i.e., written gestural and picture support) and safely modifications to PPE may reduce cognitive demands and facilitate comprehension for patients who have trouble [30]. Clinicians should be educated on how to increase utilization of available non-verbal communication techniques and use virtual geriatric clinics [31], which may allow continuing to provide an outpatient service, despite the encountered inherent challenges [32]. Communication is an under-researched area, and future studies are necessary to underpin future work. We believe that, despite the paradoxes and constraints invoked by the current pandemic, this period in history can be seen as an opportunity for us to reflect and transform key aspects of our practice not only for ourselves but also for the greater good and, for the sake of the other: our patients and their families [2].

In conclusion, we found a number of areas where communication had been challenged by the barrier methods adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that a brief training intervention focused on a mnemonic to improve communication was positively received. We plan, now, to evaluate more fully if this can affect knowledge, behavior, and clinical outcomes. Longer-term, the challenge will be to consolidate the learning from the pandemic about how staff communication is impacted by barrier methods and social distancing to permit adaptations that enhance our ability to communicate with empathy. Approaches such as the ABC mnemonic could, once more fully evaluated, be integrated into communication training to enable staff to more consistently overcome such challenges in the future.

Author contributions

MS had the idea for the study (conception and design), reviewed the literature, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, managed the survey and collected the data. SM analyzed the data. MS and SM had full access to all the data and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AG, KS and NM participated in the design of the survey. All Co-Authors participated in the interpretation of the results, revising the manuscript, and review and approval of the final manuscript. All authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria and authorship eligibility.

Funding

AG is funded in part by the National Institute of Health Research Applied Research Collaboration-East Midlands (ARC-EM). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. N.M.-V. received funding from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434), under agreement LCF/PR/PR15/51100006.

Availability of data and material

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Other information of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

As the study only involved professionals and referred to an educational improvement initiative with expert health care professionals as participants, it did not raise any of the ethical issues flagged by the European Commission in the Horizon 2020 Programme Guidance “How to complete your ethics self-assessment”. Therefore, ethics approval by an ethics review board/committee was deemed not to be necessary. This study fully complies with ethical principles, relevant EU, and international legislation including the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights. Data were stored in a database on a password-protected computer as an encrypted file. Due to the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), this database is not openly available. No personal information was collected.

Informed consent

For this type of study, informed consent is not required.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schildmann J, Härlein J, Burchardi N, Schlögl M, Vollmann J. Breaking bad news: evaluation study on self-perceived competences and views of medical and nursing students taking part in a collaborative workshop. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1157–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rushton C, Edvardsson D. Nursing, masks, COVID-19 and change. Nurs Philos. 2020 doi: 10.1111/nup.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back A, Tulsky JA, Arnold RM (2020) Communication skills in the age of COVID-19. 172. 10.7326/M20-1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemper KJ, Foy JM, Wissow L, Shore S. Enhancing communication skills for pediatric visits through on-line training using video demonstrations. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kemper KJ, Gardiner P, Gobble J, Mitra A, Woods C. Randomized controlled trial comparing four strategies for delivering e-curriculum to health care professionals [ISRCTN88148532] BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beal T, Kemper KJ, Gardiner P, Woods C. Long-term impact of four different strategies for delivering an on-line curriculum about herbs and other dietary supplements. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finset A, Bosworth H, Butow P, Gulbrandsen P, Hulsman RL, Pieterse AH, et al. Effective health communication—a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103:873–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlögl M, Jones AC. Maintaining our humanity through the mask: mindful communication during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:E12–E13. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlögl M Communication during COVID-19 pandemic. https://vimeo.com/497558181. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 12.European Commission (n.d.) Horizon 2020 programme guidance “how to complete your ethics self-assessment”, https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/ethics/h2020_hi_ethics-self-assess_en.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 13.European Commission (n.d.) Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 14.European Court of Human Rights (n.d.) European convention on human rights, https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Convention_ENG.pdf. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 15.British Geriatrics Society (BGS) (2021) Communicating through the mask: learning from the collective experience during COVID-19. https://www.bgs.org.uk/blog/communicating-through-the-mask. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 16.European Geriatric Medicine Society (EuGMS) (2021) Survey on Communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.eugms.org/news/read/article/526. Accessed 12 June 2021

- 17.Heiberger R, Robbins N. Design of diverging stacked bar charts for Likert scales and other applications. J Stat Softw. 2014;57(5):132. doi: 10.18637/jss.v057.i05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Indratmo HL, Boedianto JM, Daniel B. The efficacy of stacked bar charts in supporting single-attribute and overall-attribute comparisons. Vis Inform. 2018;2:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.visinf.2018.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly M, Svrcek C, King N, Scherpbier A, Dornan T. Embodying empathy: a phenomenological study of physician touch. Med Educ. 2020;54:400–407. doi: 10.1111/medu.14040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders GH, Jackson IR, Visram AS. Impacts of face coverings on communication: an indirect impact of COVID-19. Int J Audiol. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1851401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong CKM, Yip BHK, Mercer S, Griffiths S, Kung K, Wong MC-S, et al. Effect of facemasks on empathy and relational continuity: a randomised controlled trial in primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kratzke IM, Rosenbaum ME, Cox C, Ollila DW, Kapadia MR. Effect of clear vs standard covered masks on communication with patients during surgical clinic encounters: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:372–378. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Falletta S. Evaluating training programs: the four levels: Donald L. Kirkpatrick, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA, 1996, 229 pp. Am J Eval. 1998;19:259–261. doi: 10.1016/S1098-2140(99)80206-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Violant-Holz V, Gallego-Jiménez MG, González-González CS, Muñoz-Violant S, Rodríguez MJ, Sansano-Nadal O, et al. Psychological health and physical activity levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schofield PE, Butow PN. Towards better communication in cancer care: a framework for developing evidence-based interventions. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butow PN, Maclean M, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, Boyer MJ. The dynamics of change: cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:857–863. doi: 10.1023/a:1008284006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Lenzi R, Kudelka AP, Cohen L. Breaking bad news about cancer: patients’ preferences for communication. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2049–2056. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.7.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet A-M. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:953–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, Brown-Johnson CG, Schwartz R, Tierney AA, et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323:70–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knollman-Porter K, Burshnic VL. Optimizing effective communication while wearing a mask during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020;46:7–11. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20201012-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chua IS, Jackson V, Kamdar M. Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1507–1509. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy RP, Dennehy KA, Costello MM, Murphy EP, Judge CS, O’Donnell MJ, et al. Virtual geriatric clinics and the COVID-19 catalyst: a rapid review. Age Ageing. 2020;49:907–914. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Other information of this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Not applicable.