Abstract

Objective

To review the existing evidence on the effects of viewing visual artworks on stress outcomes and outline any gaps in the research.

Design

A scoping review was conducted based on the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews and using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. Two independent reviewers performed the screening and data extraction.

Data sources

Medline, Embase, APA PsycINFO, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, Google Scholar, Google, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations Database, APA PsycExtra and Opengrey.eu were searched in May 2020.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they investigated the effects of viewing at least one visual artwork on at least one stress outcome measure. Studies involving active engagement with art, review papers or qualitative studies were excluded. There were no limits in terms of year of publication, contexts or population types; however, only studies published in the English language were considered.

Data extraction and synthesis

Information extracted from manuscripts included: study methodologies, population and setting characteristics, details of the artwork interventions and key findings.

Results

14 primary studies were identified, with heterogeneous study designs, methodologies and artwork interventions. Many studies lacked important methodological details and only four studies were randomised controlled trials. 13 of the 14 studies on self-reported stress reported reductions after viewing artworks, and all of the four studies that examined systolic blood pressure reported reductions. Fewer studies examined heart rate, heart rate variability, cortisol, respiration or other physiological outcomes.

Conclusions

There is promising evidence for effects of viewing artwork on reducing stress. Moderating factors may include setting, individual characteristics, artwork content and viewing instructions. More robust research, using more standardised methods and randomised controlled trial designs, is needed.

Registration details

A protocol for this review is registered with the Open Science Framework (osf.io/gq5d8).

Keywords: complementary medicine, mental health, psychiatry, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A comprehensive scoping review was conducted using a broad and inclusive search strategy and a large variety of databases were searched.

The reviewers independently followed a structured and prepublished protocol for searching, screening and extracting data which followed the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines.

Only studies published in the English language were included, possibly resulting in articles of other languages being missed.

Slight deviations in the original protocol were performed in order to make the data screening more feasible.

Introduction

A number of studies and reviews have suggested that participation in the arts is beneficial for health.1–4 Because of this, many healthcare and workplace settings offer art programmes, including art therapy, music and visual art displays, to reduce stress and improve well-being for staff, patients and customers.5 However, there is little evidence that these programmes have the desired effects and there is a need for a high-quality evidence base for art-based interventions.1 4

Engagement with arts can be divided into active and passive participation. Active participation involves making, creating or teaching arts.2 6 This includes art therapy (where an art therapist directs the creation of artworks to achieve a particular goal and foster improved mental health and well-being), as well as other arts-based interventions that are not goal driven and do not require a trained professional.7 In contrast passive participation involves behaviours such as observing, viewing, listening and watching art.2 6 Passive viewing of artworks has the advantages of being an easy, low-cost and non-invasive intervention. This scoping review focused on the effects of passively viewing visual artworks and therefore excluded research pertaining to the active participation in arts.

There is some evidence that viewing artworks as an intervention is beneficial; however, this evidence is not of uniformly high quality, is rarely critical, and is sparse, with many important theoretical and evidential gaps. As well as this, most of the evidence comes from anecdotes, descriptions and personal experiences, rather than empirical research.8 9 Although many settings have been used within this research, including healthcare, art museums and laboratories, there is a paucity of evidence to demonstrate whether these settings affect outcomes differently. Demographics may be important moderators as ethnicity, gender and age may influence preferences for certain types of artworks. However, rigorous research has yet to be conducted examining the influence of settings and populations.

Due to these limitations, it is important to review the existing evidence and identify any research gaps that need to be addressed. As the evidence base is small and heterogeneous, a systematic review could not be accurately completed and would be too restrictive, so instead a scoping review was conducted. The results can be used to direct future research to fill these gaps before a full systematic review can be completed.

There is no universally accepted definition of artworks as this construct has been inconsistent and debated. For the purpose of this review, artwork was defined as two-dimensional artistic works made primarily for their aesthetics, rather than any functional purpose. This definition was created from working definitions of visual and fine arts used in previous research.10 11 Based on this definition, this review included studies on paintings, drawings and prints and excluded studies on sculpture, films, interior design or architecture. Photographs were only included if they depicted artworks, as it was deemed too difficult to determine the difference between ‘artistic’ photography and ‘non-artistic’ photography based on the definition of artworks provided for this review. Digital artworks were included.

Viewing artworks is a form of visual environmental enrichment and is theorised to be stress-reducing through positive distraction.8 12 To explore this theory, the review focused on the effects of viewing visual artworks on stress outcomes. Both psychological and physiological stress outcomes were included.

Objective and research questions

The aim of this scoping review was to systematically identify the current evidence available on the effects of viewing visual artworks on stress outcome measures and identify research and knowledge gaps to aid future research. The following research question was formulated: what research has been conducted on the effects of viewing visual artworks on stress outcomes in any populations and settings?

Several secondary questions were developed to map the available evidence:

What populations and settings were studied?

What study methodologies were used?

What stress outcomes were measured?

What type and content of artworks were viewed?

What was the duration of the artwork viewing and how many artworks were viewed?

Did the studies show changes in the stress outcomes?

Methods

A preliminary search for previous reviews on this topic was conducted on Google Scholar, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence Synthesis and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews prior to creating the protocol.

Protocol

A scoping review protocol was developed based on the JBI methodology for scoping reviews13 and using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews.

Eligibility criteria

Studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria; be a primary study where participants passively viewed at least one visual artwork as an intervention, including viewing paintings, drawings, prints, digital artwork or photographs of artworks, and measured at least one stress outcome measure (physiological or psychological indices). Measures of anxiety or mood were not considered as direct measures of stress and therefore fell out of the scope of this review. Unpublished research, including working papers, theses/dissertations and conference proceedings were included if they were identified by the search.

Studies were excluded if participants had active engagement in the arts (eg, studies on art therapy or the production/creation of art), the study investigated the effects of interior design, architecture, sculpture, films or photography not depicting artworks, and review papers, including systematic reviews, scoping reviews and meta-analyses.

As per the scoping review objectives, there were no restrictions in terms of populations, contexts, dates of publication or study designs. However, during the screening phase, it was decided to exclude qualitative studies as these studies did not have clear stress outcomes, which was a key inclusion criterion. Only studies published in the English language were considered.

Search strategy

To identify potentially relevant studies, the following electronic databases were systematically searched; Medline, Embase, APA PsycINFO, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus and Google Scholar (first 30 pages), with the help of a subject librarian. The search string combined a set of artwork and stress terms within each set with ‘OR’ and between the two sets with ‘AND.’ The search was first conducted using an extended list of search terms from the registered protocol; however, this search strategy resulted in a large number of irrelevant articles. Therefore, in the final search, some of the more ambiguous search terms were removed to refine the search further. For example, the term ‘drawing’ was removed as this could refer both to artistic drawings and ‘drawing’ blood. The final search strategies for two example databases are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Example search strategy syntax for databases

| Database | Search strategy syntax |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (artwork OR “art work” OR “visual art” OR “art museum” OR painting OR mural OR “works of art” OR “viewing art” OR “viewing artwork” OR “artwork viewing” OR “art gallery” OR “art galleries”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (stress OR “blood pressure” OR anxiety OR “heart rate” OR mood OR norepinephrine OR epinephrine OR “stress hormones” OR stressor OR glucocorticoids OR cortisol OR alpha-amylase OR “stress reduction”)) AND (LIMIT TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| ProQuest Dissertations and thesis | ab(artwork OR “art work” OR “visual art” OR “art museum” OR painting OR mural OR “works of art” OR museum OR “viewing art” OR “artistic work” OR “viewing artwork” OR “artwork viewing” OR “art gallery” OR “art galleries”) AND ab(stress OR “blood pressure” OR anxiety OR respiration OR “heart rate” OR mood OR norepinephrine OR epinephrine OR “stress hormones” OR “mental health” OR stressor OR glucocorticoids OR cortisol OR alpha-amylase OR “immune marker” OR “stress reduction”) |

The grey literature was searched using the same search terms to identify any unpublished studies. Grey literature databases searched included; Google (limited to the first 20 pages), ProQuest theses and dissertations database, APA PsycExtra and Opengrey.eu.

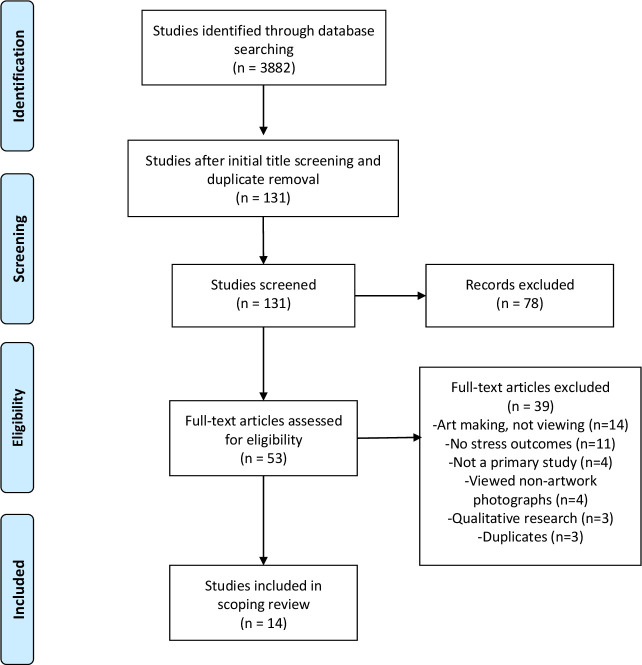

A search was then conducted by hand of the reference lists of relevant identified articles. Lastly, the ‘cited by’ feature of Google Scholar was used to see if any of the relevant studies had been cited by undetected articles. All extracted references from these searches were imported to RefWorks and all duplicates removed. The final search was executed on 27 May 2020. The number of studies identified by the search strategy is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA-ScR flow diagram of the study selection process. PRISMA-ScR, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews.

Screening and study selection

Screening of the studies identified by the search strategy was conducted by two independent reviewers using a two-staged approach using the programme Covidence (www.covidence.org). Due to the high volume and large number of unrelated studies identified, one author initially screened the titles and removed any irrelevant studies, before the first stage. In the first stage of screening, two reviewers independently screened the abstracts for the eligibility criteria. If a study’s eligibility was judged to be uncertain, the article was included in the second stage. In the second stage, two reviewers screened the full texts of the studies to determine final inclusion or exclusion based on the eligibility criteria. The two stages were conducted by the reviewers independently, with the results of each stage discussed. Any disagreements related to eligibility of an article were discussed and agreement was reached. The two reviewers had overall 86% agreement. The number of included and excluded studies at each stage of the screening procedure is shown in figure 1, with reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from each included study into a charting form by the two reviewers independently. This charting form was developed in accordance with the review questions. It included; publication details (ie, title, year, authors), methodology (ie, aims, design, population characteristics, setting, outcomes, study registration, power analyses, comparator groups, randomisation and blinding), artwork details (ie, type and content of artwork, duration of artwork viewing, number of artworks) and key findings related to scoping review questions.

The charting form was iteratively refined during the extraction process to ensure all useful information was extracted. The charting form was first independently pilot tested by the two reviewers on a random sample of four studies. The reviewers discussed this process and amended the charting form by adding a column about the artwork viewing directives given to the participants. Data extraction was then completed for the remaining studies independently by the two reviewers and any inconsistencies were discussed. This extracted data are reported in tabular and descriptive text format to answer the review questions.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in any phase of this review.

Results

As shown in figure 1, the search strategy resulted in 3882 texts, which were screened for eligibility. After the initial title and abstract screening, the full text was retrieved for 53 articles and examined against the eligibility criteria. During this process, three theses were found to have matching published journal articles and therefore were excluded as duplicates. The remaining excluded articles did not meet the eligibility criteria. This screening narrowed the studies down to 14 articles for inclusion.

The design and key findings related to the stress outcomes of each study are briefly detailed in table 2, with specific details regarding the secondary review questions provided in table 3. All 14 articles were primary studies published as journal articles. Apart from the duplicate theses mentioned above, no grey literature met the eligibility criteria for inclusion. The studies’ publication dates ranged from 1972 to 2020. Eight studies came from Europe,9 14–20 four from the USA10 21–23 and one each from Australia24 and New Zealand.25

Table 2.

Summaries of the studies’ designs and key stress outcome findings

| Study | Study design and methods | Key findings |

| Clow and Fredhoi15 | Studied self-reported stress and arousal, and salivary cortisol levels in a group of London city workers during a lunchtime visit to an art gallery. Measurements were taken before and after the 35–40 min gallery visit to explore pre-post intervention changes. | Self-reported stress and salivary cortisol levels both decreased over the intervention. There were no differences in arousal levels. |

| D'Cunha et al24 | Evaluated the psychophysiological effects of attending the National Art Gallery of Australia Art and Dementia programme. People living with dementia attended the group-based, 6-week programme which involved viewing and discussing artworks, led by an art director. Measures of salivary cortisol and interleukin-6 were taken at baseline, at the end of the programme and 12 weeks later. | Waking salivary cortisol levels increased from baseline to postintervention, but decreased at follow-up. No changes in evening cortisol or interleukin-6 were observed. The ratio of waking to evening cortisol increased from baseline to postintervention indicating a more dynamic diurnal cortisol rhythm. |

| de Jong14 | Three groups of participants (advanced art history students, advanced fine art students and laboratory workers as controls) viewed projections of 12 paintings considered to be ‘beautiful’ and 12 paintings considered to be ‘ugly’ in a random order while their heart rate, respiration rate and skin conductance was measured continuously. | The fine arts and art history students showed a greater change in skin conductance than the laboratory workers. Respiration and skin conductance were higher during the ‘beautiful’ paintings than the ‘ugly’ paintings in all groups. The fine arts students had faster heart rate during the ‘beautiful’ paintings compared with the ‘ugly’ paintings, however, for the other two groups, this result was reversed. |

| Eisen et al10 | The third phase this study investigated which type of art was most effective in reducing stress in paediatric patients. On arrival to the hospital, patients were randomly allocated to one of three rooms; a room with a nature artwork, a room with an abstract artwork or a room with no artwork. Self-reported stress, blood pressure and respiratory rate were taken at baseline and after 2 hours of exposure to the artworks. | Overall, there were no significant differences between the groups on stress, blood pressure or respiration. However, subanalyses showed that significantly more males than females in the 8–10 age group were positively affected by the nature artwork, as demonstrated by decreased self-reported stress, blood pressure and respiratory rates. |

| Karnik et al21 | Installed a diverse collection of artworks in the public spaces and clinic rooms of a hospital. Patients were retrospectively contacted with a survey which included evaluating whether the art installations changed their self-reported stress levels. | 61% of the patients that reported seeing the artworks stated that the artworks somewhat or significantly reduced their stress levels. |

| Krauss et al16 | Participants viewed six Flemish expressionism artworks in an art museum, while heart rate and skin conductance were continuously measured. Participants were randomly assigned to either receive descriptive information about the artworks (described the artwork in a declarative way) or elaborative information about the artworks (described the context and deeper meaning behind the artworks). | There were no significant differences in heart rate, heart rate variability or skin conductance between the two groups. However, in both groups heart rate was lower, and skin conductance and heart rate variability higher when viewing the artworks, compared with baseline. |

| Kweon et al22 | Conducted an experiment investigating the effects of artwork posters on stress and anger levels in an office setting. Students were asked to complete a series of stress and anger provoking computer tasks in one of four different mock office conditions; an office with nature posters, abstract posters, both nature and abstract posters or no posters. Levels of self-reported stress were measured across the experiment. | Males had the highest stress levels in the office with no posters, and the lowest stress levels in the office with mixed art posters. On the other hand, females had the highest stress in the office with all abstract posters and the lowest levels in the office with all nature posters. However, these results were only significant for males and not females. |

| Law et al25 | Conducted a pilot study to investigate whether nature artworks could improve recovery from a laboratory stressor. Participants were randomised to either view a 30 min digital slideshow of landscape artworks or digitally scrambled versions of these artworks after being exposed to a laboratory stressor. Saliva samples were taken at baseline, after the stressor, during the art viewing and after the art viewing to measure cortisol and alpha-amylase. | Salivary cortisol levels decreased more rapidly while viewing the scrambled images compared with the landscape artworks. There were no changes in alpha-amylase across the experiment or between groups. |

| Mastandrea et al17 | Students visited an art museum and were randomly assigned to visit one of three art exhibitions for 5 min; a figurative art exhibition, a modern art exhibition or a museum office as a control condition. Blood pressure and heart rate were measured before and after the visit. | Systolic blood pressure decreased in all groups; however, this decrease was only significant in the figurative art group. Heart rate also decreased in all three groups, however, there was no significant differences between groups. |

| McCabe et al9 | Evaluated the effects of the Open Window art intervention on stem-cell transplantation patients. The Open Window is a virtual window which is installed in a hospital room, where the patients can switch through nine art channels with different artworks. Patients were randomised to either a room with the Open Window or not. Self-reported distress was measured at admission, the day before transplant, 7 days after transplant, prior to discharge and 60 days, 100 days and 6 months post-transplant. | Results demonstrated no significant differences in levels of distress between the two groups at any of the time points. |

| Pearson et al23 | Examined the impact of nature-themed window murals on physiological measures in paediatric patients. Paediatric patients were assigned to hospital rooms with either a fish-themed window mural, a tree-themed window mural or no window mural. Patients’ blood pressure and heart rate were taken retrospectively from the patients’ medical records. | Those patients with the window murals had significant improvements in heart rate and systolic blood pressure, with the tree-themed mural having the greatest effect. |

| Siri et al18 | Examined the effects of viewing original physical artworks and their digital reproductions within a museum context. Cardiovascular variables were measured via ECG continuously in healthy volunteers while viewing two real abstract paintings and their digital reproductions. | Results showed that there was a significant difference in heart rate between viewing the two real paintings, but no difference was found between the digital reproductions, or between the real and digital reproductions. No differences in heart rate variability were found. |

| Tschacher et al19 | Monitored the physiology of visitors to an art museum using an electronic sensor glove which recorded physiological data and locomotion activity while they viewed the artworks. Afterwards, they were asked to rate the aesthetic qualities of some of the artworks. | Heart rate variability increased while viewing artworks that were deemed beautiful, high quality and surprising/humorous. Skin conductance variability increased, and heart rate decreased while viewing more dominant artworks (artworks experienced as dominant and stimulating by the viewers). |

| Wikström et al20 | Investigated whether visual stimulation could improve the health of elderly women living alone. The women were randomised to either an intervention or control group. The intervention group were shown a selection of pictures, including artworks, and asked to discuss them, whereas the control group discussed current events. Blood pressure was measured at baseline, immediately after the intervention and 4 months later. | The intervention group had significantly lower systolic blood pressure than the control group after the intervention and at follow-up. |

Table 3.

Overview of studies included in the review

| Study | Country | Study design | Comparator group | Setting | Population (N) | Stress outcome measures | Type and content of artwork | Quantity of artworks viewed by each participant | Duration of artwork viewing |

| Clow and Fredhoi15 | UK | Pretest and post-test, within groups quasi-experimental study | None | Art gallery | Office workers n=28 (25 included in the analysis) Power analysis not performed |

Self-reported stress Self-reported arousal Salivary cortisol |

Physical artworks in a gallery- exact content not specified | Not specified- gallery exhibition | 35–40 min in the gallery |

| D’Cunha et al24 | Australia | Pre- and post-test, within groups quasi-experimental study | None | Art gallery | People living with dementia n=28 (22 included in the analysis) Power analysis not performed |

Salivary cortisol interleukin-6 | Physical artworks in a gallery- exact content not specified | 3–4 artworks each session, over 5–6 sessions | 5–6×90 min sessions. Each artwork was viewed for 20 min |

| de Jong14 | Netherlands | Between groups experimental study | Laboratory workers (non-art students) Not randomised Not blinded |

Laboratory | Advanced art history students, advanced fine arts students and laboratory workers n=27 Power analysis not performed |

Heart rate Skin conductance Respiration rate |

Digital projections of 12 paintings considered ‘beautiful’ and 12 paintings considered ‘ugly’ | 24 | Each painting was viewed for 10 s |

| Eisen et al10 | USA | Pretest and post-test, randomised controlled trial | Room with no artwork Randomised Not blinded |

Hospital- patients’ room | Paediatric patients (aged 5–17) n=78 Power analysis not performed |

Self-reported stress Heart rate Blood pressure Respiratory rate |

One group had a representational nature artwork hung on the wall, whereas the other group had an abstract artwork hung on the wall | 1 | 2 hours |

| Karnik et al21 | USA | Cross-sectional survey | None | Hospital- public spaces and clinic rooms | Hospital patients n=826 Power analysis not performed |

Self-reported change in stress | Physical collection of abstract and representational imagery (including nature imagery). Includes an assortment of artistic media; and a variety of subject matter | Collection of over 5300 artworks | N/A |

| Krauss et al16 | Switzerland | Randomised controlled trial | Group received only descriptive information about the artwork (compared with elaborative information) Randomised Not blinded |

Art museum | General public aged between 18 and 35 n=75 Power analysis performed |

Heart rate Heart rate variability Skin conductance |

Physical abstract paintings of Flemish expressionism | 6 | Not specified |

| Kweon et al22 | USA | Between groups experimental study | No artwork posters group Randomised Not blinded |

Laboratory (replicated office setting) | Psychology students n=210 Power analysis not performed |

Self-reported stress | Nature posters and abstract posters | 4 | Not specified |

| Law et al25 | New Zealand | Between groups experimental pilot study | Scrambled artwork images Randomised Blinded |

Laboratory | General public n=30 Power analysis not performed |

Salivary cortisol Salivary alpha-amylase |

Digital slideshow of either landscape paintings or digitally scrambled versions of these paintings | 26 | 30 min |

| Mastandrea et al17 | Italy | Between groups experimental study | Museum office Randomised Not blinded |

Art museum | Undergraduate students n=77 Power analysis not performed |

Blood pressure Heart rate |

Physical artworks in a gallery- including figurative artworks (eg, landscapes and portraits) and modern artworks (eg, abstract, impressionist and informal paintings) | Not specified- gallery exhibition | 5 min |

| McCabe et al9 | Ireland | Randomised prospective clinical trial | Room without the ‘Open Window’ Randomised Not blinded |

Hospital- patients’ room | Stem cell transplantation patients n=199 (164 included in the analysis) Power analysis performed |

Self-reported distress | Virtual window, with artwork projections. Artwork collections ranged from visually complex abstract images to images of nature. | Not specified- nine art ‘channels,’ each with a collection of artworks | For the duration of their hospital stay- times not specified |

| Pearson et al23 | USA | Pretest and post-test, between groups quasi-experimental study | Room without a window mural Randomised Blinded |

Hospital- patients’ room | Paediatric patients aged 2–18) n=90 Power analysis not performed |

Heart rate Systolic blood pressure |

Window mural- either aquatic or forest themed | 1 | Minimum of 48 hours |

| Siri et al18 | Italy | Within groups experimental study | None | Art museum | General public n=60 Power analysis not performed |

Heart rate Heart rate variability |

two real abstract contemporary paintings and their digitally produced replicates | 4 | 144 s per artwork |

| Tschacher et al19 | Switzerland | Within groups quasi-experimental study | None | Art museum | Museum visitors n=517 (373 included in the analysis) Power analysis not performed |

Skin conductance Heart rate Heart rate variability |

Physical modern and contemporary art exhibition | 76 | No specific timeframe given to participants. On average, they spent 28 min at the gallery. |

| Wikström et al20 | Sweden | Pretest and post-test randomised controlled trial | Group that were not shown artworks Randomised Not blinded |

Senior citizen apartment | Women aged over 70 n=40 Power analysis not performed |

Systolic blood pressure | Physical pictures- ranging from artworks of nature, flowers and people, abstract patterns, white figures on black backgrounds and photographs. | Not specified how many each participant viewed | Not specified |

Summary of study methodologies

Designs

The 14 studies had very different designs and methodologies (see table 3). Only nine studies used a between groups design.9 10 14 16 17 20 22 23 25 Another four used a within groups design, where measures were compared previewing to postviewing the artworks, with no comparator groups.15 18 19 24 The final study used a cross-sectional design, measuring stress-reduction at one time point.21

Of the nine between groups designs, six used a no artwork control group as a comparator,9 10 17 20 22 23 and one used scrambled versions of the artworks.25 Krauss et al16 gave different viewing directives to each group and de Jong14 had groups with different art experience levels. Four of these between groups studies were considered randomised controlled trials (RCTs).9 10 16 20

Settings

Six studies were conducted in an art gallery or museum,15–19 24 three in a laboratory,14 22 25 four in hospital rooms or hospital public spaces9 10 21 23 and one in senior citizens’ apartments.20 These settings represent a mix of both naturalistic settings with high ecological validity and laboratory settings with high experimental control.

Populations

The majority of studies investigated healthy participants in the form of students,14 17 22 office workers15 or the general public.16 18 19 25 Other research used patient populations known to have high stress levels. Four studies investigated hospitalised patients,9 21 with two being paediatric samples.10 23 Lastly, D’Cunha et al24 investigated people living with dementia and Wikström et al,20 elderly women.

There is little research on whether population type affects stress reactions. Very few studies compared demographic factors, with the following exceptions. de Jong14 found that having different art experience affected outcomes. Three studies found significant differences between the stress-reducing effects of viewing artwork between males and females.10 15 22 Lastly, one study compared results across different health conditions, but found similar results between groups.21

Outcomes

Nine studies explored only physiological stress measures,14 16 19 20 23–25 three explored only psychological stress measures9 21 22 and the remaining two explored both.10 15 The psychological stress measures included; the Cox Mackay Stress Arousal checklist,26 a stress adjective checklist,27 Likert scales, and a distress thermometer.28 The physiological measures were mainly cardiovascular, including blood pressure, heart rate and skin conductance, which were measured in eight studies. Salivary biomarkers were measured in three studies15 24 25 including cortisol, alpha-amylase and interlukin-6. Respiration was measured in two studies.10 14

Registration details

None of the studies were preregistered.

Power

Sample sizes ranged from 27 to 826 participants; however, only two studies conducted a power analysis to determine their sample size. Krauss et al’s16 power analysis gave a required sample size of at least 68, and a final sample of 75 was recruited. The power analysis in McCabe et al9 gave 200 participants and a sample of 199 were recruited; however, only 164 were included in the analyses. The other 12 studies did not provide a power analysis. Law et al25 was a pilot study, and was not expected to conduct a power analysis to determine sample size. Therefore, it is difficult to determine if all studies were adequately powered.

Randomisation

All nine between-groups studies reported randomisation of participants to groups. However, the method of randomisation was not stated in many studies. Only four studies9 10 16 20 were RCTs.

Blinding

For most studies, it was difficult to blind the participants, because in most cases participants were explicitly asked to view particular artworks, and therefore both the researcher and participants were aware of which artworks they were viewing. However, two studies did successfully blind the study as both the researchers/nurses collecting the stress measures and the participants themselves were not explicitly made aware of the presence (or absence) of the artworks.23 25

Summary of the artwork interventions

Types of artworks

Ten studies used physical artworks. Most were original paintings, however, one study used posters depicting artworks22 and another used a window mural.23 Another three studies used digital reproductions of artworks. Two used slideshows of digital images,14 25 whereas the third used the Open Window, which digitally projected artworks.9 The last study directly compared physical artworks with their digital reproductions.18 This study did not find any differences between the types of artwork, indicating that digital reproductions may be just as stress-reducing as physical artworks.

Content of artworks

The content ranged from representational nature images, to complex abstract artworks. Five studies provided an assortment of artwork content in one exhibition15 17 21 24 and therefore it could not be determined whether content was influential. Two studies investigated the effects of abstract artwork but did not compare these to another artwork type.16 18 Another study14 compared the physiological effects of artworks rated to be ‘ugly’ or ‘beautiful.’ Although the exact content of the artwork was not described, this study did find that participants had higher skin conductance and respiration rates while viewing the ‘beautiful’ paintings, compared with the ‘ugly’ paintings, demonstrating that the aesthetic content of the artwork may influence their effects.

Another four studies investigated the effects of viewing nature artworks. Two studies found that self-reported stress was lower when viewing nature artworks compared with abstract artworks.10 22 One study found that different aspects of nature might have stronger effects; a forest mural resulted in larger blood pressure decreases than an aquatic mural.23 Nature content may also affect biological indicators of stress responses; cortisol levels decreased faster after a stressor in people viewing scrambled versions of nature artworks, compared with the original nature artworks.25

The remaining two studies9 20 did not report on the content of the artwork, and therefore, cannot be categorised.

Duration of artwork viewing

Nine studies reported the duration participants spent looking at the artwork (see table 3). This ranged from 2 min to over 48 hours. No study investigated whether changing the duration of exposure to artworks affected stress outcomes.

Quantity of artworks

Most of the studies did not specify the exact number of artworks viewed. Of those studies that did specify a number, it ranged from one artwork to over 5300 in one exhibition. Half of the studies had participants view a collection of artworks as an exhibition or art programme. Only two studies showed each participant one artwork and both were in paediatric hospital rooms.10 23 The other experimental studies ranged from viewing 4 to 26 artworks in one sitting, with the exact numbers provided in table 3.

Viewing directives

Five studies explicitly mentioned the viewing directives given to participants. The researchers from two experimental studies told participants to attentively look at and explore each artwork,14 18 whereas the researcher in another study asked visitors to explore the art gallery in any way they pleased.15 The remaining two studies asked participants to discuss and describe each artwork to the group during art programmes.20 24 One of these studies24 had a trained art educator facilitating the discussions, whereas the other20 had a lead researcher, with no specified training.

Summary of key findings

All but one of the studies that measured self-reported stress found a significant decrease after viewing artwork,10 15 21 22 with the final study showing no significant changes.9 A consistent decrease in systolic blood pressure was also found across the four studies measuring blood pressure.10 17 20 23 Skin conductance and skin conductance variability both increased while viewing artworks.14 16 19 The results for heart rate were mostly consistent. Two of the three studies that measured heart rate found that viewing artworks decreased heart rate.19 23 The other study found that viewing beautiful paintings increased heart rate for students trained in fine arts and decreased heart rate for other participants.14

The cortisol and respiration results were less consistent. An art gallery visit decreased salivary cortisol levels15; however, a 6-week art intervention for people living with dementia increased waking cortisol levels.24 Lastly, after a stressor, salivary cortisol decreased faster in those viewing scrambled images, compared with those viewing landscapes.25 Viewing beautiful paintings lead to an increase in respiration rates in a healthy sample.14 Whereas nature artworks in a hospital room decreased respiration rates in children.10 These studies all had different samples, settings and artworks which may have accounted for these mixed findings. Lastly both alpha-amylase25 and interleukin- 624 were each only measured in one study and showed no significant changes.

Discussion

This scoping review aimed to identify the available evidence on the effects of viewing visual artworks on stress outcomes and identify gaps in the research. The 14 included studies demonstrate that research in this area is growing, with 10 studies being published in the last 10 years. There are a number of limitations to research in this area, including a paucity of RCTs, and heterogeneous methodologies and interventions. This scoping review was able to comprehensively identify the relevant research and descriptively present some evidence to address the research questions outlined in the introduction and identify gaps for future research, as detailed below.

Overall, the preliminary findings from the included studies support the claim that viewing artworks can reduce stress, in particular self-reported stress and systolic blood pressure. These preliminary quantitative results support qualitative research showing that viewing artworks provides positive distraction from a hospital environment and lowers self-reported stress.9 12 29 The findings indicated that digital artworks can have similar stress-reducing effects to physical artworks, thus increasing the avenues available for viewers. Artwork interventions can therefore be transposed onto computers, televisions, phones and tablets, as a portable, cheap and easy intervention for stress-reduction.

Together the preliminary evidence suggest that the provision of artworks could reduce stress. However, mixed findings combined with a lack of homologous methodologies mean that more rigorous research is needed. Future research needs to employ stronger methods including: adequate comparator groups, power analyses to ensure sufficient sample sizes, clearly defined randomisation procedures and preregistration. If we examine the results from just the four RCTs, the evidence is even less conclusive. More detail on these studies and their findings are provided in table 2; however, only one of the four RCTs showed significant effects for their main hypotheses. Wikström et al20 found a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure after an art intervention. In contrast, McCabe et al9 found no significant effects on distress measures, and Eisen et al10 only found significant effects when subgroup analyses of age were conducted. Lastly, Krauss et al16 did find significant decreases in physiological stress when viewing artworks compared with baseline; however, they found no significant differences between the viewing directives provided, which was their main hypothesis. Therefore, more RCTs still need to be conducted on this topic for clearer conclusions to be made.

The differences between the studies suggest important moderating factors, one of which is setting. The museum context may add to the effects of viewing artwork, as museum related factors may lead to greater appreciation of artwork.30 In addition, viewing artwork in a museum usually involves walking, which has its own stress-reducing effects.31 Laboratory studies remove some of these contextual factors and may provide more specific evidence for the effects of viewing artworks, but they have lower ecological validity. The hospital room is an important setting as patients are often confined to their room for long time periods and rooms are often deprived of environmental enrichment. Artwork could act as visual stimulation to positively distract patients from their stress, pain and medical conditions, and therefore it is suggested that artwork is placed in hospital rooms and waiting rooms. Artwork could also have stress-reducing benefits in other settings such as waiting rooms and workplaces, which are often related to high stress. More research in these settings should be conducted.

Other possible moderating factors include individual characteristics, although little research has investigated these. Gender differences were found in two of the included studies, with a trend towards females experiencing greater stress-reduction in response to nature artworks.10 22 One small survey found that African Americans and Caucasians have similar preferences for nature artworks32; however, no study has investigated whether culture affects the stress-reducing effects of artworks. Given the diversity in cultures, demographics and individual preferences for artwork, it may be over simplistic to suggest that all individuals experience artwork the same way.33

The findings indicate that the content and aesthetic qualities of artwork are also important considerations. Although mixed, the studies generally indicated that nature, especially greenery, may be the most stress-reducing. This is consistent with research demonstrating that nature artwork is most preferred by adults34 and children.10 There are two main theories as to why viewing nature is beneficial for humans. The evolutionary theory proposes that because humans evolved in a natural environment, nature is processed more efficiently and we are predisposed to experience restoration.35 On the other hand, the attention restoration theory posits that nature can counteract the mental fatigue caused by stress and therefore reduce cognitive strain.36 Thus, these two theories point to nature artwork as having the greatest stress reducing effects, as demonstrated in this review. In contrast, abstract artworks can be seen as challenging, ambiguous and unclear for viewers, leading to increased stress.30 37 This is supported by the emotional congruence theory which posits that stressed people are likely to project their negative experiences and emotions onto ambiguous environmental surroundings, including artworks.5 Other artwork content could be provocative and emotionally inappropriate for certain situations, eliciting anger and dislike. For example, a study by Ho et al33 found that certain provocative artworks elicited feelings of loneliness and hopelessness in viewers, suggesting artwork must be chosen carefully, with particular emphasis on the provision of nature artworks.

The mixed findings suggest that under some conditions, viewing artwork may be physiologically relaxing, whereas under other conditions viewing artwork may be physiologically stimulating. The direction of these effects may not only depend on the content of the artwork, but also the context and viewers’ stress levels. Regardless of the direction of effects on physiology, lower self-reported stress may result.

Although this review focused on the stress-reducing effects of viewing artwork, it may also be important to investigate the stimulating aspects of artwork. For certain populations, such as people living with dementia, visual stimulation and enrichment through artworks could improve other aspects of health, such as cognitive function.24 As discussed above, visual stimulation and enrichment may also be important to provide positive distraction from negative experiences. Three studies showed an increase in physiological stress.14 24 25 This increased stimulation may be related to the content of the artworks (‘beautiful’ vs ‘ugly’ paintings,14 or landscapes vs scrambled images25) or the types of populations involved (people living with dementia24 and art students14). Therefore, the provision of stimulating artworks may be appropriate for certain situations, including for people living with dementia.

Choice may be another important variable. This is especially pertinent in settings where people have little control. Art Carts have been used in hospitals to allow patients to choose which artworks to view during their stay to give them a sense of control over their environment.29 Two studies in this review9 20 gave participants a choice of artwork, however research is yet to investigate whether the element of choice affects stress outcomes.

Directives given to viewers may influence the way participants view artworks and therefore moderate the artworks’ stress-reducing effects. Wikström38 previously discussed the importance of creating an art-dialogue when viewing and discussing artworks in order to improve engagement, understanding and empowerment. Other research33 demonstrated that the descriptions given to viewers about artwork could be influential, and therefore this may be an important element for studies to include. However, few studies reported the directives given. It is important for future research to report what directives were provided and investigate whether this is influential.

Finally, it is difficult to determine the dose-response relationship of artwork viewing. There was little consistency in the number of artworks shown to each participant, and no study investigated whether the quantity of artworks or viewing durations mattered. Therefore, future research could investigate the best artwork viewing duration and number of works.

Limitations

This review is limited by only including articles published in the English language. Articles in other languages could have been missed. The review deviated slightly from the original protocol. Due to the large number of irrelevant articles identified using the original search strategy, the search terms were narrowed and the original title screening was only conducted by one reviewer. These deviations were required to make the search and screening more feasible. This review did not include anxiety or mood measures or studies using qualitative methodology, as these outcomes were considered outside the scope of the review.

Conclusions

This scoping review summarised the relevant research that investigated viewing visual artworks on stress outcomes. Fourteen studies met the eligibility criteria, with extracted results showing consistent reductions in self-reported stress and systolic blood pressure, but mixed effects on other physiological outcomes. However, there were only four RCTs, and there was high heterogeneity in research methodologies. Setting, individual characteristics, artwork content and viewing instructions may be important moderating factors. More robust research is recommended that uses standardised interventions, validated assessment methods and RCT designs, to investigate the effects of viewing visual art on stress outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ML and EB conceptualised the project and designed the scoping review protocol. ML performed the search strategy. ML and NK performed the study screening and data extraction. ML wrote the manuscript. EB and NK edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript. ML and EB made the revisions to the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Boyce M, Bungay H, Munn-Giddings C, et al. The impact of the arts in healthcare on patients and service users: a critical review. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26:458–73. 10.1111/hsc.12502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carswell C, Reid J, Walsh I, et al. Arts-based interventions for hospitalised patients with cancer: a systematic literature review. British Journal of Healthcare Management 2018;24:611–6. 10.12968/bjhc.2018.24.12.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Lith T. Art therapy in mental health: a systematic review of approaches and practices. The Arts in Psychotherapy 2016;47:9–22. 10.1016/j.aip.2015.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vetter D, Barth J, Uyulmaz S, et al. Effects of art on surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2015;262:704–13. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hathorn K, Nanda U. A guide to evidence-based art. The Center for Health Design 2008:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies CR, Rosenberg M, Knuiman M, et al. Defining arts engagement for population-based health research: art forms, activities and level of engagement. Arts Health 2012;4:203–16. 10.1080/17533015.2012.656201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spooner H. Embracing a full spectrum definition of art therapy. Art Therapy 2016;33:163–6. 10.1080/07421656.2016.1199249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lankston L, Cusack P, Fremantle C, et al. Visual art in hospitals: case studies and review of the evidence. J R Soc Med 2010;103:490–9. 10.1258/jrsm.2010.100256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCabe C, Roche D, Hegarty F, et al. ‘Open Window’: a randomized trial of the effect of new media art using a virtual window on quality of life in patients’ experiencing stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology 2013;22:330–7. 10.1002/pon.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisen SL, Ulrich RS, Shepley MM, et al. The stress-reducing effects of art in pediatric health care: art preferences of healthy children and hospitalized children. J Child Health Care 2008;12:173–90. 10.1177/1367493508092507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacey S, Hagtvedt H, Patrick VM, et al. Art for reward's sake: visual art recruits the ventral striatum. Neuroimage 2011;55:420–33. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George DR, de Boer C, Green MJ. "That landscape Is where I'd Like to be… ": offering patients with cancer a choice of artwork. JAMA 2017;317:890–2. 10.1001/jama.2017.1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, McInerney P. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence manual. Adelaide, Australia: JBI, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Jong MA. A physiological approach to aesthetic preference. I. paintings. Psychother Psychosom 1972;20:360–5. 10.1159/000286439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clow A, Fredhoi C. Normalisation of salivary cortisol levels and self-report stress by a brief lunchtime visit to an art gallery by London City workers. Journal of Holistic Healthcare 2006;3:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krauss L, Ott C, Opwis K, et al. Impact of contextualizing information on aesthetic experience and psychophysiological responses to art in a museum: a naturalistic randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2019. 10.1037/aca0000280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mastandrea S, Maricchiolo F, Carrus G, et al. Visits to figurative art museums may lower blood pressure and stress. Arts Health 2019;11:123–32. 10.1080/17533015.2018.1443953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siri F, Ferroni F, Ardizzi M. Behavioral and autonomic responses to real and digital reproductions of works of art. Prog Brain Res 2018;237:201–21. 10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tschacher W, Greenwood S, Kirchberg V, et al. Physiological correlates of aesthetic perception of artworks in a museum. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2012;6:96–103. 10.1037/a0023845 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wikström B-M, Theorell T, Sandström S. Medical health and emotional effects of art stimulation in old age. Psychother Psychosom 1993;60:195–206. 10.1159/000288693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karnik M, Printz B, Finkel J. A hospital's contemporary art collection: effects on patient mood, stress, comfort, and expectations. HERD 2014;7:60–77. 10.1177/193758671400700305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kweon B, Ulrich R, Walker V. Anger and stress: the role of landscape posters in an office setting. Environ Behav 2008;40:355–81. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearson M, Gaines K, Pati D, et al. The physiological impact of window murals on pediatric patients. HERD 2019;12:116–29. 10.1177/1937586718800483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Cunha NM, McKune AJ, Isbel S, et al. Psychophysiological responses in people living with dementia after an art gallery intervention: an exploratory study. JAD 2019;72:549–62. 10.3233/JAD-190784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Law M, Minissale G, Lambert A, et al. Viewing landscapes is more stimulating than scrambled images after a stressor: a cross-disciplinary approach. Front Psychol 2019;10:3092. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackay C, Cox T, Burrows G, et al. An inventory for the measurement of self-reported stress and arousal. Br J Soc Clin Psychol 1978;17:283–4. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1978.tb00280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King MG, Burrows GD, Stanley GV. Measurement of stress and arousal: validation of the stress/arousal adjective checklist. Br J Psychol 1983;74 (Pt 4:473–9. 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1983.tb01880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer 1998;82:1904–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suter E, Baylin D. Choosing art as a complement to healing. Appl Nurs Res 2007;20:32–8. 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mastandrea S. Visitor’s approaches, personality traits and psycho-physiological well-being in different art style museums. International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Digital Environments for Education, Arts and Heritage; Springer 2018:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly P, Williamson C, Niven AG, et al. Walking on sunshine: Scoping review of the evidence for walking and mental health. Br J Sports Med 2018;52:800–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hathorn K, Ulrich R. The therapeutic art program of Northwestern memorial hospital. Creating Environments that Heal: Proceedings of the Symposium On Healthcare Design 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho RTH, Potash JS, Fang F, et al. Art viewing directives in hospital settings effect on mood. HERD 2015;8:30–43. 10.1177/1937586715575903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nanda U, Eisen SL, Baladandayuthapani V. Undertaking an art survey to compare patient versus student art preferences. Environ Behav 2008;40:269–301. 10.1177/0013916507311552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulrich R, Simons R, Miles M. Effects of environmental simulations and television on blood donor stress. J Archit Plann Res 2003;20:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol 1995;15:169–82. 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ulrich R. How design impacts wellness. Healthc Forum J 1992;35:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wikström B-M. The dynamics of visual art dialogues: experiences to be used in hospital settings with visual art enrichment. Nurs Res Pract 2011;2011:1–7. 10.1155/2011/204594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. No data are available.