Abstract

Objectives

(a) To adapt the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT)-patient-reported outcome (PRO) Extension guidance to a user-friendly format for patient partners and (b) to codesign a web-based tool to support the dissemination and uptake of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension by patient partners.

Design

A 1-day patient and public involvement session.

Participants

Seven patient partners.

Methods

A patient partner produced an initial lay summary of the SPIRIT-PRO guideline and a glossary. We held a 1-day PPI session in November 2019 at the University of Birmingham. Five patient partners discussed the draft lay summary, agreed on the final wording, codesigned and agreed the final content for both tools. Two additional patient partners were involved in writing the manuscript. The study compiled with INVOLVE guidelines and was reported according to the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 checklist.

Results

Two user-friendly tools were developed to help patients and members of the public be involved in the codesign of clinical trials collecting PROs. The first tool presents a lay version of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance. The second depicts the most relevant points, identified by the patient partners, of the guidance through an interactive flow diagram.

Conclusions

These tools have the potential to support the involvement of patient partners in making informed contributions to the development of PRO aspects of clinical trial protocols, in accordance with the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidelines. The involvement of patient partners ensured the tools focused on issues most relevant to them.

Keywords: protocols & guidelines, quality in health care, qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Two user-friendly tools were codeveloped with patient and public involvement (PPI) partners for the use of patient partners involved in the codesign of clinical trials collecting patient-reported outcomes.

The research was reported according to Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 checklist and adhered to INVOLVE recommendations.

The user-friendly tools were not tested among a wider patient partner group.

In addition, the PPI partners included in the codevelopment of the tools were mainly oncology patients.

Introduction

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) provide information about the status of a patient’s health, directly from the patient, without interpretation by a clinician.1 PROs are collected in clinical trials to provide evidence of the impact of disease treatment on functional health, well-being, severity of symptoms or side effects, and psychological impact of the disease and/or the treatment.2

Clinical trials are medical research studies carried out to determine the activity, safety, efficacy, effectiveness and adverse effects of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.3 Clinical trial protocols describe the objective(s), design, procedures and statistical considerations needed to conduct a specific clinical trial. Recent research suggests important PRO protocol-items, such as hypotheses, data collection methods and statistical plans are often missing from trial protocols.4–7 Furthermore, rates of avoidable missing PRO data are often high4 5 8 and PRO data publications are reported long after other outcomes or not at all9 10; if reported, the PRO reporting is often inadequate.7–9 11–14

A recent review of 228 National Institute of Health Research Cancer portfolio studies identified that PRO data were left unreported for studies involving nearly 50 000 patients, which is unacceptable and unethical.9 Moreover, such failures and omissions compromise the impact of PROs on future patient care and health policy, and also waste valuable resources in terms of patient and researcher time and funding.

In 2018, the SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials)-PRO Extension was published with the aim to provide recommendations for researchers on which items should be addressed in clinical trial protocols with primary or key secondary PRO endpoints. However, there is a lack of training materials and tools to support the uptake of the SPIRIT-PRO guidance to promote quality and to simplify the approach for patient partners who are involved in the review and codesign of clinical trials with PRO objectives.15 The aim of this research was to: (a) adapt the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance to a user-friendly format for patient partners and (b) codesign a web-based tool to support the dissemination and uptake of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension by patient partners.

Methods

A patient partner (GP) produced an initial lay summary of the SPIRIT-PRO guideline and drafted a glossary with support from academic coauthors (MC and SCR). The patient partner selected to produce the initial lay summary and glossary was originally involved in the development of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guideline. In addition, the patient partner has experienced completing PRO questionnaires and has been involved in different PRO-specific projects to provide his perspective from a patient’s perspective.

A 1-day PPI (patient and public involvement) session was held with patient partners in November 2019 at the University of Birmingham, UK. The aim of the PPI session was to adapt the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance to a user-friendly format for patient partners, and codesign a tool to aid patient partners in the codesign of PRO clinical trials. The PPI session was conducted and reported according to the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP) 2 reporting checklists. This international provides guidance on the key reporting items for reporting PPI in health and social care research.16 In addition, the PPI session complied with the INVOLVE guideline, a government supported programme that promotes active public involvement in National Health Service, public health and social care research.17

Patient and public involvement

Seven PPI partners who were already known to the team, who had relevant experience in clinical trials, were recruited by the research team to assist at different stages in the development of the tools. The PPI partners were six patients and one carer with personal experience of different health conditions including oncology (four PPI partners), Parkinson’s (one PPI partner) and chronic kidney disease (one PPI partner). Six PPI partners identified themselves as white and one as Sikh British. Only three of the PPI partners were previously involved as trial participants. One partner was involved in the development of the first version of the patient-friendly SPIRIT-PRO guidance. Five were involved in the codesign of the patient-friendly SPIRIT-PRO tools, and all seven contributed to writing this manuscript.

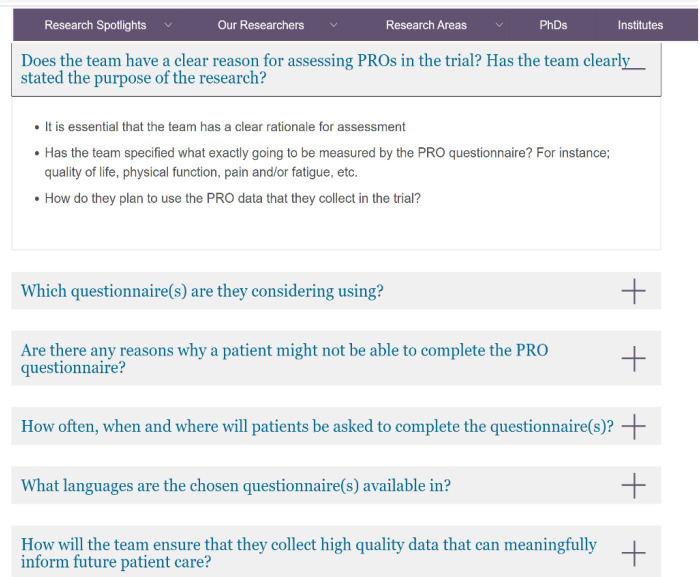

During the session, five PPI partners (GP/LR/LG/RV/PE) and two academics (MC and SCR) discussed the original SPIRIT-PRO Extension guideline and contrasted it with the initial lay summary drafted. PPI partners commented on the comprehension and refined and agreed the wording and clarity of the lay version of the SPIRIT-PRO guideline and glossary (figure 1). Following the PPI session, attendees commented on the wording and agreed on the penultimate version of the user-friendly SPIRIT-PRO Extension content. Broader feedback on final guidance was sought from two additional patient partners (RW/RS).

Figure 1.

User-friendly SPIRIT-PRO Extension and glossary methods. PPI, patient and public involvement; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

During the PPI session, patient partners discussed the design and content of a previously published diagram (PRO learn resource for patient advocates involved in coproduction of research or review, online supplemental appendix 1) on the PRO considerations for PPI partners in the design and review of trials collecting PROs.18 PPI partners highlighted key SPIRIT-PRO items and additional information that should be incorporated in the published diagram. These changes led to the development of the web-tool.

bmjopen-2020-046450supp001.pdf (35.7KB, pdf)

Results

Seven PPI partners were involved in the codesign of two tools to promote the uptake and dissemination of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance by patient partners involved in the codevelopment of clinical trials. PPI partners highlighted specific priorities and preferred formats. In addition, PPI partners contributed to the writing up of the discussion section and in particular around the benefits of the development of these tools.

User-friendly version of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance

This tool was developed to adapt the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance to a user-friendly format for patient partners. The user-friendly tool (table 1) presents five different key items for PPI partners to consider while involved in the codesign and/or review of trials collecting PROs: (a) SPIRIT-PRO item number and description; (b) questions for PPI partner(s) to consider; (c) key considerations for PPI partner(s); (d) considerations for the lay summary and (e) considerations for the participant information sheet and consent form. A glossary (online supplemental appendix 2) was also codeveloped to aid PPI partners in the implementation of the user-friendly tool.

Table 1.

User-friendly version of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance

| SPIRIT-PRO item number and description | Questions for PPI partner(s) to consider | Key considerations for PPI partner(s) | Considerations for the lay summary | Considerations for participant information sheet and consent form |

| Administrative information | ||||

| SPIRIT-5a-PRO Elaboration: specify the individual(s) responsible for the PRO content of the trial protocol | Are PPI partners being involved in the codesign of trials involving PROs? (Are they patients or carers; are there different considerations?) |

|

||

| ||||

| Introduction | ||||

| SPIRIT-6a-PRO Elaboration: describe the PRO-specific research question and rationale for PRO assessment and summarise PRO findings in relevant studies | Is the research team collecting PROs? If not, why not? |

|

Has the research team looked at the literature around previous trials, qualitative work or COS (core outcome sets) on what matters to the patient (or carer)? | Describe the PRO specific research question and rationale for PRO assessment, and summarise PRO findings in relevant studies. |

| If yes, do the team have a clear reason for assessing PROs in the trial? |

|

|||

| Have the team specified their goals in assessing PROs? |

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

| SPIRIT-7-PRO Elaboration: state specific PRO objectives or hypotheses (including relevant PRO concepts/domains) | Has the research team clearly stated the purpose of the research? |

|

It is important that lay summary clearly describe the purpose of assessing PROs in the trial. | Include the purpose of assessing PROs in the trial. |

| Methods: participants, interventions and outcomes | ||||

| SPIRIT-10-PRO Elaboration: specify any PRO-specific eligibility criteria (eg, language/reading requirements or prerandomisation completion of PRO). If PROs will not be collected from the entire study sample, provide a rationale and describe the method for obtaining the PRO subsample | Are there any specific reasons why a participant might not be able to complete the PRO questionnaire? |

|

Has data protection been taken into consideration if proxy completion is a possibility? | |

| ||||

| ||||

| SPIRIT-12-PRO Elaboration: specify the PRO concepts/domains used to evaluate the intervention (eg, overall health-related quality of life, specific domain, specific symptom) and, for each one, the analysis metric (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event) and the principal time point or period of interest | Has the team specified exactly what is going to be measured? How and when do they plan to do this? For example, physical function, pain and/or HRQL, etc. |

|

Include what questionnaire(s) are going to be completed during the trial. | |

| SPIRIT-13-PRO Elaboration: include a schedule of PRO assessments, providing a rationale for the time points, and justifying if the initial assessment is not prerandomisation. Specify time windows, whether PRO collection is prior to clinical assessments, and, if using multiple questionnaires, whether order of administration will be standardised | How often will participants be asked to complete the questionnaire(s)? |

|

How often are the participants going to be asked to complete the questionnaire(s), when and with what deadlines? | |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| SPIRIT-14-PRO Elaboration: when a PRO is the primary end point, state the required sample size (and how it was determined) and recruitment target (accounting for expected loss to follow-up). If sample size is not established based on the PRO end point, then discuss the power of the principal PRO analyses | Is the required number of participants feasible to recruit based on the population being assessed? | PPI partners are not expected to assess whether the sample size is adequate, but you may have views on whether people are likely to be interested in participating in the PRO aspects of the trial. | ||

| Are the exclusion criteria too restrictive (ie, they are excluding too many people)? | If you see something in the protocol that patients or carers might not like then please raise this with the trial team as it may affect whether they have big enough numbers for their study. | |||

| Are there cultural/age related/geography/frailty/language condition/working status reasons why people may not participate or may drop-out? | ||||

| Methods: data collections, management and analysis | ||||

| SPIRIT-18a(i)-PRO Elaboration: Justify the PRO instrument to be used and describe domains, number of items, recall period, instrument scaling and scoring (eg, range and direction of scores indicating a good or poor outcome). Evidence of PRO instrument measurement properties, interpretation guidelines, and patient acceptability and burden should be provided or cited if available, ideally in the population of interest. State whether the measure will be used in accordance with any user manual and specify and justify deviations if planned | How did they select the questionnaire (eg, literature, PPI session)? |

|

Include how long is going to take to complete the questionnaire. | |

| Which questionnaire(s) are they considering using? |

|

Are there any questions, such as sexual function, which patients may not wish to answer and may result in missing data? | ||

| Does it cover patient priorities? |

|

Specify the estimated time to complete each assessment, and discuss feasibility of assessment for the population. | ||

| Are the instructions for completion of the questionnaire clear? |

|

|||

| Can you understand the scoring categories? Are they properly explained and do they make sense? | ||||

| SPIRIT-18a(ii)-PRO Elaboration: include a data collection plan outlining the permitted mode(s) of administration (eg, paper, telephone, electronic, other) and setting (eg, clinic, home, other) | Where, when and how will the PRO questionnaire be completed? |

|

Include a data collection plan outlining the permitted mode(s) of administration (eg, paper, telephone, electronic, other) and setting (eg, clinic, home, other). | |

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| SPIRIT-18a(iii)-PRO Elaboration: specify whether more than 1 language version will be used and state whether translated versions have been developed using currently recommended methods | What languages are the chosen questionnaire(s) available? |

|

||

| Have they got questionnaires available for trial population? |

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

| These are the responsibilities of the trial team but PPI partners may be able to suggest ways of widening inclusivity. | ||||

| SPIRIT-18a(iv)-PRO Elaboration: when the trial context requires someone other than a trial participant to answer on his or her behalf (a proxy-reported outcome), state and justify the use of a proxy respondent. Provide or cite evidence of the validity of proxy assessment if available | Has the research team made clear whether it is possible for someone other than the patient to complete the questionnaire from the patient’s point of view? |

|

If it is permissible for another person to help the study participant complete the PROM, describe what type and level of assistance is acceptable. | |

| ||||

| How will the team ensure that data collected is complete? So that it can be used to inform patient care. |

|

|||

| Ideally researchers should have plans in place to ensure that participants complete questionnaires as they are scheduled | Can you think of any other ideas that may help promote completion? |

|

||

|

||||

| SPIRIT-18b(ii)-PRO Elaboration: describe the process of PRO assessment for participants who discontinue or deviate from the assigned intervention protocol | Is there a plan for collecting data provided by patients who stop receiving the treatment under study (discontinue), or receive the treatment in a way other than planned (deviation)? |

|

||

| ||||

| SPIRIT-20a-PRO Elaboration: state PRO analysis methods, including any plans for addressing multiplicity/type I (α) error | What method has the research team selected to analyse the PRO data? | PPI partners are not expected to contribute in the selection of methods for addressing multiple testing. However, they could ask the team to explain what PRO analysis method has been chosen and why. | ||

| SPIRIT-20c-PRO Elaboration: state how missing data will be described and outline the methods for handling missing items or entire assessments (eg, approach to imputation and sensitivity analyses) | How is the research team going to analyse the PRO data? | PPI partners are not expected to plan how data will be analysed, but can question the trial team about the methods that will be used to handle missing data. | ||

| How will the team deal with missing data? | ||||

| Monitoring | ||||

| SPIRIT-22-PRO Elaboration: state whether or not PRO data will be monitored during the study to inform the clinical care of individual trial participants and, if so, how this will be managed in a standardised way. Describe how this process will be explained to participants; for example, in the participant information sheet and consent form | Will questionnaire data be reviewed by the research or clinical team? If so, when? What happens if the PRO indicates patient deterioration or distress? Have the research team explained what sorts of scores would indicate distress or deterioration? |

|

What measures are in place to ensure patient distress or deterioration is identified, communicated to patient and dealt with it? | |

| How will participants be informed of this process? (ie, in the participant information sheet and consent form). |

|

If data will not be clinically reviewed, how concerns are going to be dealt with by the clinical research team. For instance, mobile phone to support (emergency number) and what resources are there to support participants. | ||

| Include detailed plans for regular feedback to participants via letter/newsletter on PRO aspect of study. | ||||

HRQL, Health-related quality of life; PPI, patient and public involvement; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

bmjopen-2020-046450supp002.pdf (134.6KB, pdf)

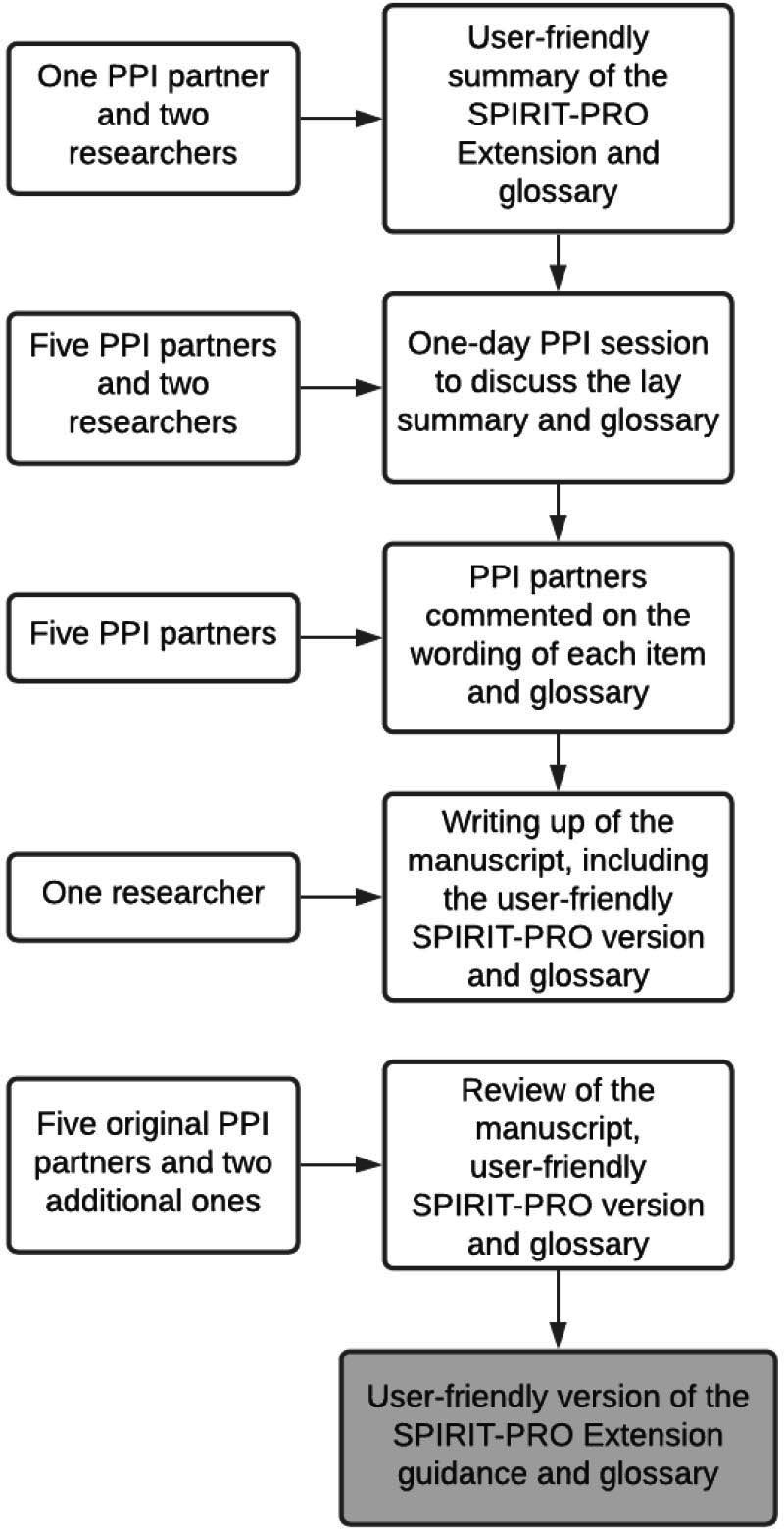

Web-based tool

The web-based tool, presented in concertina style, illustrates the main key items PPI partners considered most relevant from the user-friendly SPIRIT-PRO Extension version. The web-tool aimed at supporting the dissemination and uptake of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension by patient partners, provides PPI partners with six general PRO-specific questions to facilitate their role as codesigners and interaction with the trial team. PPI partners are not expected to answer these questions but to raise these questions with the research team while codeveloping the clinical trial.

The main six SPIRIT-PRO items included were: (a) does the team have a clear reason for assessing PROs in the trial? And has the team clearly stated the purpose of the research? (b) which questionnaire(s) are they considering using? (c) are there any reasons why a patient might not be able to complete the PRO questionnaire? (d) how often, when and where will patients be asked to complete the questionnaire(s)? (e) what languages are the chosen questionnaire(s) available in? and (f) how will the team ensure that they collect high quality data that can meaningfully inform future patient care? The diagram provides further detail to each question to help PPI partners ask more in depth questions and better understand the importance of capturing PROs in trials. In addition, the web-tool includes ‘other considerations’ and ‘other resources’ for PPI partners to facilitate their understanding and participation in the design of the trial. For instance, ‘other considerations’ includes key elements that should be covered in the participant information sheet for potential trial participants. ‘Other resources’ include web resources such as ePROVIDE and GRIPP 2 checklist.19 The webtool is available from the Centre for Patient Reported Outcomes Research website.20 Figure 2 presents an overview of the codeveloped web-tool.

Figure 2.

Web-tool for patient advocates involved in coproduction of PRO research or review. PRO, patient-reported outcome.

Discussion

Two user-friendly tools were codesigned with the assistance of seven patient partners to assist PPI partners involved in the design or review of clinical trials and provide informed, patient-centred input into development of PRO aspects of clinical trial protocols. PPI in this research was essential to ensure that the tools were comprehensive and user friendly for PPI partners. In addition, it was essential to enhance the dissemination and uptake of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance.

The involvement of PPI partners helped ensure that the tools focused on issues that matter most to them. PPI should go beyond involvement; it should be a platform for patients to influence, design processes, identify relevant content and to make decisions significant for and acceptable to end users.21 22 PPI partners raised important concerns related to the completion of PRO questionnaires such as: time needed to complete the PRO questionnaire(s) and frequency patients need to complete the questionnaire(s). Although these are covered by the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance, they were included in the patient information sheet section under the ‘other resources’ section.

Patients have recently advocated against regulatory agencies for approving oncology drugs based on surrogate endpoints rather than the value they add to patients’ lives.23 24 In addition, patients frequently do not completely understand their diagnostics and are not aware of the side effects of the interventions, as they are occasionally not effectively communicated by healthcare professionals.24 Therefore, patient and public awareness and their involvement can help tackle these issues.23 24 Currently, PRO stakeholders are making concerted efforts to incorporate the patients’ experience into the drug development process, which has the potential to better inform shared decision-making.25 For instance, the Food and Drug Administration is patient-focused drug development guidance to address how stakeholders can collect and include PROs from patients and caregivers in the development and regulation of medical products.26 In 2016, the European Medicine Agency published Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. Appendix 2 describes the use of PRO endpoints in oncology studies and the value of PRO data from the regulatory perspective.27

PROs carry the ‘voice’ of the patients; hence, trials collecting PROs should include patients and carers as codesigners to inform PRO measure development, selection, and implementation and ensure that PRO data are analysed and published.21 28 Thus, maximising the impact on future patient benefit and reducing research waste. The design of trials collecting PROs without patient input can be considered unreasonable and unacceptable.9 21 PPI partners should be empowered to be involved in the design of trials collecting PROs and their content, and make decisions by using the two different tools developed, while following the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance. The strengths of the research include the participation of seven PPI partners, who were selected with a range of levels of experience and exposure to trial development to ensure the outputs were well-informed, but also accessible for new patients and public. Adherence to GRIPP 2 guidance to report PPI involvement in research was a further strength of the study.16 The tools presented in this manuscript were developed to aid patient partners in the codevelopment or review of clinical trials collecting PROs. Nonetheless, these tools have the potential to be used in other types of clinical studies in which the participation of patients and carers is essential.

However, the tools developed were not tested among patient partners with less trial experience or less experience with research, which could have helped in the refinement of the tools. A further limitation is that two PPI partners involved in the codevelopment of the user-friendly version of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidance were involved in the development of the original guidance. This previous knowledge and understanding of the SPIRIT-PRO items might have influenced the selection of lay vocabulary. However, to tackle these four additional PPI partners were included to agree on the best wording of the guidance. Patient partners were involved in the same way in both research projects. However, patient partners drove the agenda more during the codevelopment of the tools for patients as the aim of the research was to develop tools for them to use. An additional limitation is that PPI partners’ perspectives may not be reflective of a larger patient population as the majority of the participants were oncology partners and only one carer was included.

In conclusion, the tools developed, if used appropriately, have the potential to facilitate the involvement of patient partners in providing informed input into the development of PRO aspects of clinical trial protocols, in accordance with the SPIRIT-PRO Extension guidelines.

Next steps

Feedback can be provided on the resource using an anonymised survey https://www.smartsurvey.co.uk/s/SPIRIT-PRO_Tools_for_patients/, which will help inform future developments. We encourage PPI partners and researchers involved in the design or review of trials collecting PROs to provide further feedback to the research team.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @samsamcr

Contributors: SCR lead the conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology and writing of the original draft. RS critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. GP contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript and reviewed the draft. PE, LG, LR and RV contributed to the conceptualisation of the manuscript. RW, RM-B, CR, OLA and AS contributed to the conceptualisation and reviewed and edited the manuscript. MC acquired funding, lead the conceptualisation and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by an unrestricted educational research grant from UCB Pharma. Award/Grant number is not applicable.

Competing interests: MC and AS receive funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, the NIHR Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre and NIHR ARC West Midlands at the University of Birmingham and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Health Data Research UK, Innovate UK (part of UK Research and Innovation), Macmillan Cancer Support, UCB Pharma. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. MC has received personal fees from Astellas, Takeda, Merck, Daiichi Sankyo, Glaukos, GlaxoSmithKline and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) outside the submitted work. RM-B is supported by the Australian Government by a National Health and Medical Research. OLA declares personal fees from Gilead Sciences Ltd and GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was gained from the University of Birmingham, UK (ERN_19-0939).

References

- 1.FDA . Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims., 2009. Available: http://wwwfdagov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Wilson IB, Cleary P. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. JAMA 1995;273:59. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520250075037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK Clinical Research Collaboration . Understanding clinical trials 2006. Available: https://www.ukcrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/iCT_Booklet.pdf

- 4.Ahmed K, Kyte D, Keeley T, et al. Systematic evaluation of patient-reported outcome (PRO) protocol content and reporting in UK cancer clinical trials: the EPIC study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012863. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Retzer A, Keeley T, Ahmed K, et al. Evaluation of patient-reported outcome protocol content and reporting in UK cancer clinical trials: the EPIC study qualitative protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017282. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercieca-Bebber R, Friedlander M, Kok P-S, et al. The patient-reported outcome content of international ovarian cancer randomised controlled trial protocols. Qual Life Res 2016;25:2457–65. 10.1007/s11136-016-1339-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyte D, Duffy H, Fletcher B, et al. Systematic evaluation of the patient-reported outcome (pro) content of clinical trial protocols. PLoS One 2014;9:e110229. 10.1371/journal.pone.0110229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercieca-Bebber R, Friedlander M, Calvert M, et al. A systematic evaluation of compliance and reporting of patient-reported outcome endpoints in ovarian cancer randomised controlled trials: implications for generalisability and clinical practice. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2017;1:5. 10.1186/s41687-017-0008-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kyte D, Retzer A, Ahmed K, et al. Systematic evaluation of patient-reported outcome protocol content and reporting in cancer trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2019;111:1170–8. 10.1093/jnci/djz038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schandelmaier S, Conen K, von Elm E, et al. Planning and reporting of quality-of-life outcomes in cancer trials. Ann Oncol 2015;26:1966–73. 10.1093/annonc/mdv283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brundage M, Bass B, Davidson J, et al. Patterns of reporting health-related quality of life outcomes in randomized clinical trials: implications for clinicians and quality of life researchers. Qual Life Res 2011;20:653–64. 10.1007/s11136-010-9793-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercieca-Bebber RL, Perreca A, King M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in head and neck and thyroid cancer randomised controlled trials: a systematic review of completeness of reporting and impact on interpretation. Eur J Cancer 2016;56:144–61. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, et al. Beyond the development of health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) measures: a checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials - does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision making? J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3502–11. 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dirven L, Taphoorn MJB, Reijneveld JC, et al. The level of patient-reported outcome reporting in randomised controlled trials of brain tumour patients: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer 2014;50:2432–48. 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, et al. Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols: the spirit-pro extension. JAMA 2018;319:483–94. 10.1001/jama.2017.21903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Staniszewska S, Brett J, Simera I, et al. GRIPP2 reporting checklists: tools to improve reporting of patient and public involvement in research. BMJ 2017;358:j3453. 10.1136/bmj.j3453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.INVOLVE . About involve. Available: https://www.invo.org.uk/about-involve/ [Accessed Oct 2020].

- 18.Calvert MaK, Derek . I’m a patient advocate involved in the design or review of a study using PROs. What should I consider? : CPROR, 2016. Available: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-mds/centres/PRO-Guide-for-Patient-Advocates.pdf

- 19.ePROVIDE clinical support for clinical outcome assessments. Available: https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/

- 20.Centre for patient reported outcomes research - PRO learn. Available: https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/applied-health/research/prolearn/patient-advocates.aspx

- 21.Wilson R. Patient led PROMs must take centre stage in cancer research. Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:7. 10.1186/s40900-018-0092-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selby P, Velikova G. Taking patient reported outcomes centre stage in cancer research - why has it taken so long? Res Involv Engagem 2018;4:25. 10.1186/s40900-018-0109-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cromptom S. PROMs put patients at the heart of research and care, 2018. Available: https://cancerworld.net/featured/proms-put-patients-at-the-heart-of-research-and-care/81

- 24.Richards T. The responses to the “cancer drugs scandal” must fully involve patients-an essay by Tessa Richards. BMJ 2017;359:j4956. 10.1136/bmj.j4956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kluetz PG, O'Connor DJ, Soltys K. Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e267–74. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30097-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FDA patient-focused drug development guidance series for enhancing the incorporation of the patient’s voice in medical product development and regulatory decision making, 2018. Available: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/ucm610279.htm [Accessed Jan 2019].

- 27.European Medcines Agency . Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. The use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies. London: European Medicine Agency, 2016. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/other/appendix-2-guideline-evaluation-anticancer-medicinal-products-man_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haywood KL, Wilson R, Staniszewska S, et al. Using PROMs in healthcare: who should be in the driving seat-policy makers, health professionals, methodologists or patients? Patient 2016;9:495–8. 10.1007/s40271-016-0197-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046450supp001.pdf (35.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-046450supp002.pdf (134.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.