Abstract

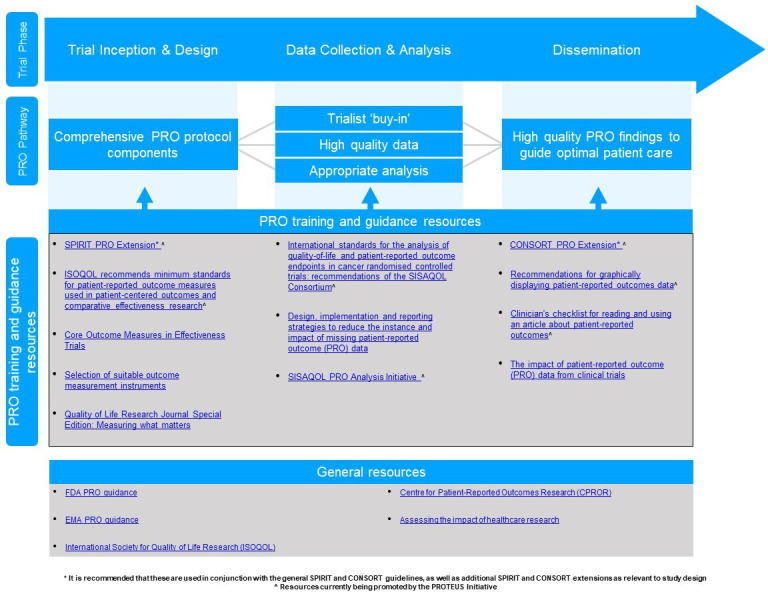

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are used in clinical trials to provide valuable evidence on the impact of disease and treatment on patients’ symptoms, function and quality of life. High-quality PRO data from trials can inform shared decision-making, regulatory and economic analyses and health policy. Recent evidence suggests the PRO content of past trial protocols was often incomplete or unclear, leading to research waste. To address this issue, international, consensus-based, PRO-specific guidelines were developed: the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT)-PRO Extension. The SPIRIT-PRO Extension is a 16-item checklist which aims to improve the content and quality of aspects of clinical trial protocols relating to PRO data collection to minimise research waste, and ultimately better inform patient-centred care. This SPIRIT-PRO explanation and elaboration (E&E) paper provides information to promote understanding and facilitate uptake of the recommended checklist items, including a comprehensive protocol template. For each SPIRIT-PRO item, we provide a detailed description, one or more examples from existing trial protocols and supporting empirical evidence of the item’s importance. We recommend this paper and protocol template be used alongside the SPIRIT 2013 and SPIRIT-PRO Extension paper to optimise the transparent development and review of trial protocols with PROs.

Keywords: statistics & research methods, education & training (see medical education & training), protocols & guidelines, clinical trials

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT)-patient-reported outcome (PRO) Extension aims to improve the completeness and transparency of trial protocols where PROs are a primary or key secondary outcomes and was developed following Enhancing Quality and Transparency of Health Research Network Guidance.

This explanation and elaboration paper provides information to promote understanding and facilitate uptake of the recommended PRO protocol SPIRIT-PRO checklist items for clinical trials.

A comprehensive protocol template and selected examples from existing trial protocols are provided to facilitate implementation.

The protocol template and explanation and elaboration paper were developed with multistakeholder international input including: trialists, PRO methodologists, psychometricians, patient partners, industry representatives, journal editors, regulators and ethicists.

Although the guidance is limited in focus to clinical trials, many of the SPIRIT-PRO items may also provide useful prompts about PRO content for cohort studies and other non-randomised designs.

Background

Clinical trial protocols are essential documents intended to include the study rationale, intervention, trial design methods, study processes, outcomes, sample size, data collection procedures, proposed analyses and ethical considerations. Provision of sufficient detail is necessary to enable the research team to conduct a high-quality, reproducible study. It also facilities external appraisal of the scientific, methodological and ethical rigour of the trial by relevant stakeholders.1 2 Although trial protocols serve as the foundation for study planning, conduct, reporting and appraisal, they vary greatly in content and quality.1 2 Appraisals of the patient-reported outcome (PRO) content of over 350 past trial protocols revealed that many protocols lack specific information needed for high-quality PRO data collection and evidence generation (online supplemental 1).3–5 As a result, research personnel and potential research participants may not appreciate the purpose of PRO data collection,6 and the need for standardised PRO assessment methods. This may result in high levels of missing data and poor quality or non-reporting of PRO trial results, which may hinder the potential for PRO evidence to be used in regulatory decision-making, health policy and clinical care.6–8 For example, a recent review of cancer portfolio trials illustrates this point; recommended PRO protocol content was frequently not addressed and PRO data from 61 trials, including 49 568 participants, was unpublished.9 Another trial also cited poor PRO completion rates as the reason for not publishing PRO data—and the corresponding trial protocol included only sparse guidance related to the PRO study.7

bmjopen-2020-045105supp001.pdf (45.2KB, pdf)

In 2013, core protocol guidelines applicable to all types of trials was published based on expert consensus and research evidence, in the form of the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 2013 statement. Its corresponding SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration (E&E) paper provides important information to promote full understanding of, and assist protocol writers to implement, the 33 checklist recommendations.1 2 However, SPIRIT 2013 does not provide specific recommendations about PRO endpoints. PROs can provide valuable information on the risks, benefits and tolerability of an intervention. PRO data are intrinsically subjective, requiring completion by patient-participants within a specific time frame and, as a result, present a range of scientific and logistical challenges for researchers which should be addressed in the trial protocol.6 10–12

To address this issue, international stakeholders worked to develop the SPIRIT-PRO Extension, with the aim of improving PRO content of trial protocols and supporting documents, for use in conjunction with SPIRIT 2013 Guidelines and E&E papers.1 2 The SPIRIT-PRO Extension was published in 2018 and comprises 11 extensions (new, PRO-specific items) and 5 elaborations (an elaboration of an existing SPIRIT 2013 item as applied to clinical trials assessing PROs) recommended for inclusion in clinical trial protocols that have PROs as primary or key secondary outcomes (table 1).10 The SPIRIT-PRO Extension paper reports the 16 items and describes the methods used to develop the checklist, but does not provide detailed implementation instructions or examples. This SPIRIT-PRO E&E paper aims to promote understanding of the guidelines, provide real examples of SPIRIT-PRO items being addressed from a range of different trials and facilitate uptake of the recommended checklist items. A table of contents detailing where to find an example and explanation of each item is provided in table 2. In addition, we describe the development of a new PRO protocol template (online supplemental file 2) for use in protocol development. Additional information and resources regarding the SPIRIT Initiative are available on the SPIRIT website (www.spirit-statement.org).

Table 1.

SPIRIT 2013 and SPIRIT-PRO Extension checklist: recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol

| SPIRIT section | SPIRIT item no. | SPIRIT item description | SPIRIT-PRO item no. | SPIRIT-PRO extension or elaboration item description | Page number of example/explanation |

| Administrative information | |||||

| Title | 1 | Descriptive title identifying the study design, population, interventions and, if applicable, trial acronym | |||

| Trial registration | 2a | Trial identifier and registry name (if not yet registered, name of intended registry) | |||

| 2b | All items from the WHO Trial Registration Data Set | ||||

| Protocol version | 3 | Date and version identifier | |||

| Funding | 4 | Sources and types of financial, material and other support | |||

| Roles and responsibilities | 5a | Names, affiliations and roles of protocol contributors | SPIRIT5a-PRO Elaboration | Specify the individual(s) responsible for the PRO content of the trial protocol. | 11–12 |

| 5b | Name and contact information for the trial sponsor | ||||

| 5c | Role of study sponsor and funders, if any, in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report and the decision to submit the report for publication, including whether they will have ultimate authority over any of these activities | ||||

| 5d | Composition, roles and responsibilities of the coordinating centre, steering committee, endpoint adjudication committee, data management team and other individuals or groups overseeing the trial, if applicable (see item 21a for data monitoring committee) | ||||

| Introduction | |||||

| Background and rationale | 6a | Description of research question and justification for undertaking the trial, including summary of relevant studies (published and unpublished) examining benefits and harms for each intervention | SPIRIT6a-PRO Extension | Describe the PRO-specific research question and rationale for PRO assessment and summarise PRO findings in relevant studies. | 12 |

| 6b | Explanation for choice of comparators | ||||

| Objectives | 7 | Specific objectives or hypotheses | SPIRIT7-PRO Extension | State specific PRO objectives or hypotheses (including relevant PRO concepts/domains). | 12–14 |

| Trial design | 8 | Description of trial design, including type of trial (eg, parallel group, crossover, factorial, single group), allocation ratio and framework (eg, superiority, equivalence, non-inferiority, exploratory) | |||

| Methods: participants, interventions and outcomes | |||||

| Study setting | 9 | Description of study settings (eg, community clinic, academic hospital) and list of countries where data will be collected; reference to where list of study sites can be obtained | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 10 | Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants; if applicable, eligibility criteria for study centres and individuals who will perform the interventions (eg, surgeons, psychotherapists) | SPIRIT10-PRO Extension | Specify any PRO-specific eligibility criteria (eg, language/reading requirements or prerandomisation completion of PRO). If PROs will not be collected from the entire study sample, provide a rationale and describe the method for obtaining the PRO subsample. | 14 |

| Interventions | 11a | Interventions for each group with sufficient detail to allow replication, including how and when they will be administered | |||

| 11b | Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions for a given trial participant (eg, drug dose change in response to harms, participant request or improving/worsening disease) | ||||

| 11c | Strategies to improve adherence to intervention protocols and any procedures for monitoring adherence (eg, drug tablet return, laboratory tests) | ||||

| 11d | Relevant concomitant care and interventions that are permitted or prohibited during the trial | ||||

| Outcomes | 12 | Primary, secondary and other outcomes, including the specific measurement variable (eg, systolic blood pressure), analysis metric (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event), method of aggregation (eg, median, proportion) and timepoint for each outcome; explanation of the clinical relevance of chosen efficacy and harm outcomes is strongly recommended | SPIRIT12-PRO Extension | Specify the PRO concepts/domains used to evaluate the intervention (eg, overall health-related quality of life, specific domain, specific symptom) and, for each one, the analysis metric (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event) and the principal timepoint or period of interest. | 14–16 |

| Participant timeline | 13 | Time schedule of enrolment, interventions (including any run-ins and washouts), assessments and visits for participants; a schematic diagram is highly recommended (see figure in Chan et al)1 2 | SPIRIT13-PRO Extension | Include a schedule of PRO assessments, providing a rationale for the timepoints and justifying if the initial assessment is not prerandomisation. Specify time-windows, whether PRO collection is prior to clinical assessments, and, if using multiple questionnaires, whether order of administration will be standardised. | 16–17 |

| Sample size | 14 | Estimated number of participants needed to achieve study objectives and how it was determined, including clinical and statistical assumptions supporting any sample size calculations | SPIRIT14-PRO Elaboration | When a PRO is the primary endpoint, state the required sample size (and how it was determined) and recruitment target (accounting for expected loss to follow-up). If sample size is not established based on the PRO endpoint, then discuss the power of the principal PRO analyses. | 17–19 |

| Recruitment | 15 | Strategies for achieving adequate participant enrolment to reach target sample size | |||

| Methods: assignment of interventions (for clinical trials) | |||||

| Allocation | |||||

| Sequence generation | 16a | Method of generating the allocation sequence (eg, computer-generated random numbers), and list of any factors for stratification. To reduce predictability of a random sequence, details of any planned restriction (eg, blocking) should be provided in a separate document that is unavailable to those who enrol participants or assign interventions | |||

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 16b | Mechanism of implementing the allocation sequence (eg, central telephone; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes), describing any steps to conceal the sequence until interventions are assigned | |||

| Implementation | 16c | Who will generate the allocation sequence, who will enrol participants, and who will assign participants to interventions | |||

| Blinding (masking) | 17a | Who will be blinded after assignment to interventions (eg, trial participants, care providers, outcome assessors, data analysts) and how | |||

| 17b | If blinded, circumstances under which unblinding is permissible and procedure for revealing a participant’s allocated intervention during the trial | ||||

| Methods: data collection, management and analysis | |||||

| Data collection methods | 18a | Plans for assessment and collection of outcome, baseline and other trial data, including any related processes to promote data quality (eg, duplicate measurements, training of assessors) and description of study instruments (eg, questionnaires, laboratory tests) along with their reliability and validity, if known; reference to where data collection forms can be found, if not in the protocol | SPIRIT-18a (i)-PRO Extension | Justify the PRO instrument to be used and describe domains, number of items, recall period and instrument scaling and scoring (eg, range and direction of scores indicating a good or poor outcome). Evidence of PRO instrument measurement properties, interpretation guidelines and patient acceptability and burden should be provided or cited if available, ideally in the population of interest. State whether the measure will be used in accordance with any user manual and specify and justify deviations if planned. | 19–20 |

| SPIRIT-18a (ii)-PRO Extension | Include a data collection plan outlining the permitted mode(s) of administration (eg, paper, telephone, electronic, other) and setting (eg, clinic, home, other). | 20–21 | |||

| SPIRIT-18a (iii)-PRO Extension | Specify whether more than one language version will be used and state whether translated versions have been developed using currently recommended methods. | 21–22 | |||

| SPIRIT-18a (iv)-PRO Extension | When the trial context requires someone other than a trial participant to answer on his or her behalf (a proxy-reported outcome), state and justify the use of a proxy respondent. Provide or cite evidence of the validity of proxy assessment if available. | 22–23 | |||

| 18b | Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up, including list of any outcome data to be collected for participants who discontinue or deviate from intervention protocols | SPIRIT-18b (i)-PRO Extension | Specify PRO data collection and management strategies for minimising avoidable missing data. | 23–24 | |

| SPIRIT-18b (ii)-PRO Elaboration | Describe the process of PRO assessment for participants who discontinue or deviate from the assigned intervention protocol. | 24–25 | |||

| Data management | 19 | Plans for data entry, coding, security and storage, including any related processes to promote data quality (eg, double data entry; range checks for data values); reference to where details of data management procedures can be found, if not in the protocol | |||

| Statistical methods | 20a | Statistical methods for analysing primary and secondary outcomes. Reference to where other details of the statistical analysis plan can be found, if not in the protocol | SPIRIT20a-PRO Elaboration | State PRO analysis methods, including any plans for addressing multiplicity/type I (α) error. | 25–26 |

| 20b | Methods for any additional analyses (eg, subgroup and adjusted analyses) | ||||

| 20c | Definition of analysis population relating to protocol non-adherence (eg, as randomised analysis) and any statistical methods to handle missing data (eg, multiple imputation) | SPIRIT20c-PRO Elaboration | State how missing data will be described and outline the methods for handling missing items or entire assessments (eg, approach to imputation and sensitivity analyses). | 26–27 | |

| Methods: monitoring | |||||

| 21a | Composition of data monitoring committee; summary of its role and reporting structure; statement of whether it is independent from the sponsor and competing interests and reference to where further details about its charter can be found, if not in the protocol (alternatively, an explanation of why a data monitoring committee is not needed) | ||||

| 21b | Description of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines, including who will have access to these interim results and make the final decision to terminate the trial | ||||

| Harms | 22 | Plans for collecting, assessing, reporting and managing solicited and spontaneously reported adverse events and other unintended effects of trial interventions or trial conduct | SPIRIT22-PRO Extension | State whether or not PRO data will be monitored during the study to inform the clinical care of individual trial participants and, if so, how this will be managed in a standardised way. Describe how this process will be explained to participants; for example, in the participant information sheet and consent form. | 27–29 |

| Auditing | 23 | Frequency and procedures for auditing trial conduct, if any, and whether the process will be independent from investigators and sponsor(s) | |||

| Ethics and dissemination | |||||

| Research ethics approval | 24 | Plans for seeking research ethics committee/institutional review board approval | |||

| Protocol amendments | 25 | Plans for communicating important protocol modifications (eg, changes to eligibility criteria, outcomes, analyses) to relevant parties (eg, investigators, research ethics committees/institutional review boards, trial participants, trial registries, journals, regulators) | |||

| Consent or assent | 26a | Who will obtain informed consent or assent from potential trial participants or authorised surrogates and how (see item 32) | |||

| 26b | Additional consent provisions for collection and use of participant data and biological specimens in ancillary studies, if applicable | ||||

| Confidentiality | 27 | How personal information about potential and enrolled participants will be collected, shared and maintained to protect confidentiality before, during and after the trial | |||

| Declaration of interests | 28 | Financial and other competing interests for principal investigators for the overall trial and each study site | |||

| Access to data | 29 | Statement of who will have access to the final trial data set and disclosure of contractual agreements that limit such access for investigators | |||

| Ancillary and post-trial care | 30 | Provisions, if any, for ancillary and post-trial care and for compensation to those who are harmed by trial participation | |||

| Dissemination policy | 31a | Plans for investigators and sponsor(s) to communicate trial results to participants, healthcare professionals, the public and other relevant groups (eg, via publication, reporting in results databases or other data-sharing arrangements), including any publication restrictions | |||

| 31b | Authorship eligibility guidelines and any intended use of professional writers | ||||

| 31c | Plans, if any, for granting public access to the full protocol, participant-level data set and statistical code | ||||

| Appendixes | |||||

| Informed consent materials | 32 | Model consent form and other related documentation given to participants and authorised surrogates | |||

| Biological specimens | 33 | Plans for collection, laboratory evaluation and storage of biological specimens for genetic or molecular analysis in the current trial and for future use in ancillary studies, if applicable | |||

PRO, patient-reported outcome; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

Table 2.

Table of contents and resources

| SPIRIT-PRO item no. | Item title | SPIRIT-PRO extension or elaboration item description | Page number of example/explanation |

| 5a | SPIRIT5a-PRO Elaboration | Specify the individual(s) responsible for the PRO content of the trial protocol. | 11–12 |

| 6a | SPIRIT6a-PRO Extension | Describe the PRO-specific research question and rationale for PRO assessment and summarise PRO findings in relevant studies. | 12 |

| 7 | SPIRIT7-PRO Extension | State-specific PRO objectives or hypotheses (including relevant PRO concepts/domains). | 12–14 |

| 10 | SPIRIT10-PRO Extension | Specify any PRO-specific eligibility criteria (eg, language/reading requirements or prerandomisation completion of PRO). If PROs will not be collected from the entire study sample, provide a rationale and describe the method for obtaining the PRO subsample. | 14 |

| 12 | SPIRIT12-PRO Extension | Specify the PRO concepts/domains used to evaluate the intervention (eg, overall health-related quality of life, specific domain, specific symptom) and, for each one, the analysis metric (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event) and the principal timepoint or period of interest. | 14–16 |

| 13 | SPIRIT13-PRO Extension | Include a schedule of PRO assessments, providing a rationale for the timepoints and justifying if the initial assessment is not prerandomisation. Specify time-windows, whether PRO collection is prior to clinical assessments, and, if using multiple questionnaires, whether order of administration will be standardised. | 16–17 |

| 14 | SPIRIT14-PRO Elaboration | When a PRO is the primary endpoint, state the required sample size (and how it was determined) and recruitment target (accounting for expected loss to follow-up). If sample size is not established based on the PRO endpoint, then discuss the power of the principal PRO analyses. | 17–19 |

| 18a | SPIRIT-18a (i)-PRO Extension | Justify the PRO instrument to be used and describe domains, number of items, recall period and instrument scaling and scoring (eg, range and direction of scores indicating a good or poor outcome). Evidence of PRO instrument measurement properties, interpretation guidelines and patient acceptability and burden should be provided or cited if available, ideally in the population of interest. State whether the measure will be used in accordance with any user manual and specify and justify deviations if planned. | 19–20 |

| SPIRIT-18a (ii)-PRO Extension | Include a data collection plan outlining the permitted mode(s) of administration (eg, paper, telephone, electronic, other) and setting (eg, clinic, home, other). | 20–21 | |

| SPIRIT-18a (iii)-PRO Extension | Specify whether more than one language version will be used and state whether translated versions have been developed using currently recommended methods. | 21–22 | |

| SPIRIT-18a (iv)-PRO Extension | When the trial context requires someone other than a trial participant to answer on his or her behalf (a proxy-reported outcome), state and justify the use of a proxy respondent. Provide or cite evidence of the validity of proxy assessment if available. | 22–23 | |

| 18b | SPIRIT-18b (i)-PRO Extension | Specify PRO data collection and management strategies for minimising avoidable missing data. | 23–24 |

| SPIRIT-18b (ii)-PRO Elaboration | Describe the process of PRO assessment for participants who discontinue or deviate from the assigned intervention protocol. | 24–25 | |

| 20a | SPIRIT-20a-PRO Elaboration | State PRO analysis methods, including any plans for addressing multiplicity/type I (α) error. | 25–26 |

| 20c | SPIRIT-20c-PRO Elaboration | State how missing data will be described and outline the methods for handling missing items or entire assessments (eg, approach to imputation and sensitivity analyses). | 26–27 |

| 22 | SPIRIT-22-PRO Extension | State whether or not PRO data will be monitored during the study to inform the clinical care of individual trial participants and, if so, how this will be managed in a standardised way. Describe how this process will be explained to participants; for example, in the participant information sheet and consent form. | 27–29 |

| Additional resources | |||

| Table 1. SPIRIT 2013 and SPIRIT-PRO Extension checklist: recommended items to address in a clinical trial protocol | 3–8 | ||

| Glossary of terms | 10–11 | ||

| Protocol template | Online supplemental file 2 | ||

PRO, patient-reported outcome; SPIRIT, Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials.

bmjopen-2020-045105supp002.pdf (366.6KB, pdf)

The development of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension followed the Enhancing Quality and Transparency of Health Research Network’s methodological framework for guideline development,13 and has been published elsewhere.10 Briefly, these methods included:

a systematic review of existing PRO-specific protocol guidelines to generate the list of potential PRO-specific protocol items;14

refinements to the list and removal of duplicate items by the International Society for Quality of Life Research (ISOQOL) Protocol Checklist Taskforce;

an international stakeholder survey of trial research personnel, PRO methodologists, health economists, psychometricians, patient advocates, funders, industry representatives, journal editors, policy makers, ethicists and researchers responsible for evidence synthesis (distributed by 38 international partner organisations);

an international Delphi exercise;

a consensus meeting in May 2017 to finalise the guidelines and implementation strategy.

International stakeholders provided feedback on the final wording of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension during a final 3-week consultation period. Following minor edits, the guidelines were finalised and agreed by the SPIRIT-PRO Group.10

Development of the PRO protocol template

A PRO protocol template was developed to support implementation of the SPIRIT-PRO guidance (ethical approval ERN_19–0939). The draft template was reviewed by members of the project team and broader SPIRIT-PRO Group, including patient partners. In addition, an international advisory group (IAG), comprising global PRO leads from major pharmaceutical companies, regulators and academics, was convened to review and provide additional feedback on the template. Teleconference meetings were held with members of the SPIRIT-PRO Group and the IAG to discuss the feedback received. Based on the feedback, the template was revised and sent to all for final comments. After a final consultation period, the PRO protocol template was revised and finalised.

Patient and public involvement

Patient partners were involved in the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans of our research, including development of the SPIRIT-PRO Extension, the E&E paper, protocol template, tools to support implementation by patient partners and are included as coauthors.15

Glossary

Concept

‘The specific measurement goal (ie, the thing that is to be measured by a PRO instrument). In clinical trials, a PRO instrument can be used to measure the effect of a medical intervention on one or more concepts. PRO concepts represent aspects of how patients function or feel related to a health condition or its treatment’.16

Domain

‘A subconcept represented by a score of an instrument that measures a larger concept comprised multiple domains. For example, psychological function is a larger concept with multiple domains (emotional and cognitive function) that are measured by relevant items.’16

Endpoint*

The variable to be analysed. It is a precisely defined variable intended to reflect an outcome of interest that is statistically analysed to address a particular research question. A precise definition of an endpoint typically specifies the type of assessments made, the timing of those assessments, the assessment tools used and possibly other details, as applicable, such as how multiple assessments within an individual are to be combined17 (eg, change from baseline at 6 weeks in mean fatigue score).18

Health-related quality of life

‘A multidimensional concept that usually includes self-report of the way in which physical, emotional, social or other domains of well-being are affected by a disease or its treatment.’19

Important or key secondary PROs/endpoints

Some PRO measures (particularly health-related quality-of-life measures) are multidimensional, producing several domain-specific outcome scales; for example, pain, fatigue, physical function, psychological distress. For any particular trial, it is likely that a particular PRO or PRO domain(s) will be more relevant than others, reflecting the expected effect(s) of the trial intervention(s) in the target patient population. These relevant PRO(s) and/or domain(s) may additionally constitute the important or key secondary PROs (identified a priori and specified as such in the trial protocol and statistical analysis plan) and will be the focus of hypothesis testing. In a regulatory environment, these outcomes may support a labelling claim. Because these outcomes are linked with hypotheses (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)-PRO Extension 2b),19 they may be subject to p value adjustment (or ‘α spending’). Beyond efficacy/effectiveness, PROs may also be used to capture and provide evidence of safety and tolerability (eg, using the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events).20

Instrument

‘A means to capture data (eg, a questionnaire) plus all the information and documentation that supports its use. Generally, that includes clearly defined methods and instructions for administration or responding, a standard format for data collection and well-documented methods for scoring, analysis and interpretation of results in the target patient population.’16

Intervention/Treatment

A process or action that is the focus of a clinical study. Interventions include drugs, medical devices, procedures, vaccines and other products that are either investigational or already available. Interventions can also include non-invasive approaches, such as education or modifying diet and exercise.21

Item

‘An individual question, statement or task (and its standardised response options) that is evaluated by the patient to address a particular concept.’16

Observer-reported outcome

‘A measurement based on a report of observable signs, events or behaviours related to a patient’s health condition by someone other than the patient of a healthcare professional.’22

Outcome*

The variable to be measured. It is the measurable characteristic that is influenced or affected by an individuals’ baseline state or an intervention as in a clinical trial or other exposure17 (eg, a fatigue score).

Patient-reported outcome

A PRO is any report of the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else and may include patient assessments of health status, quality of life or symptoms.16 19 PROs are assessed by self-reported questionnaires, referred to as PRO measures or instruments.17

Primary outcome

The most important outcome in a trial, prespecified in the protocol, providing the most clinically relevant evidence directly related to the primary objective of the trial.

Proxy-reported outcome

‘A measurement based on a report by someone other than the patient reporting as if he or she is the patient.’16

Secondary outcomes

Outcomes prespecified in the protocol to assess additional effects of the intervention; some PROs may be identified as important or key secondary outcomes.

SPIRIT Elaboration item

An elaboration of an existing SPIRIT item as applied to a specific context; in this instance, as applied to clinical trials assessing PROs.

SPIRIT-PRO Extension item

An additional checklist item describing PRO protocol content to address an aspect of PRO assessment that is not adequately covered by SPIRIT, as judged by available evidence and expert opinion.

Time-window

A predefined time frame before and after the protocol-specified PRO assessment timepoint, whereby the result would still be deemed to be clinically relevant.23

*The terms outcome and endpoint are often used interchangeably, although this is not always consistent with the range of definitions available. For the definitions included in this glossary, an endpoint is defined from PRO data (ie, the outcome) by fully specifying four components: measurement variable (eg, fatigue ‘in the past week’ as measured by the QLQ-C30), analysis metric (eg, change in fatigue from baseline, final fatigue value, time to clinically important increase in fatigue (and ‘event’), method of aggregation (eg, median fatigue, proportion of patients with severe fatigue, proportion of patients with clinically important change in fatigue) and timepoint. Note that using these definitions, several endpoints can be defined from the same outcome source data, revealing the distinction and relationship between ‘outcome’ and ‘endpoint’ for PROs.

Purpose and development of the explanation and elaboration paper and PRO protocol template

The SPIRIT-PRO Extension, this E&E and the included PRO protocol template are intended to guide the development of trial protocols for ethical review, where PROs are a primary or key secondary outcome, including single-arm and multi-arm trials. We recommend that authors also consider inclusion of checklist items when PROs are exploratory in nature, as appropriate. Protocols may be formatted in accordance with local requirements, however they need to address the SPIRIT-PRO items completely and transparently. The examples provided in this E&E document and protocol template are not intended to be prescriptive about how information is included in protocols, nor how trials be conducted. Trialists may, for example, wish to include a PRO-specific, dedicated section in the protocol with content informed by the SPIRIT-PRO checklist, while others may wish to add PRO content to existing sections of the protocol.

Modelled after other reporting guidelines,2 24 25 this E&E paper presents each checklist item with at least one example from a trial protocol, followed by an explanation of the rationale and main issues to address, to facilitate understanding and usage. The guidelines are intended to be used in conjunction with the SPIRIT-PRO Extension, SPIRIT 2013 Statement and E&E paper and other relevant extensions.1 2 10 26 Empirical data and references to support each SPIRIT-PRO item are provided. Real-world examples for each SPIRIT-PRO item, quoted verbatim, are presented to reflect how key elements could be appropriately described in a trial protocol. These examples were obtained from E&E paper authors, public websites, journals, trial investigators and industry sponsors. Some examples illustrate a specific component of a checklist item, while others encompass all key recommendations for an item. Reference numbers cited in the original quoted text are denoted by (Reference) to distinguish them from references cited in this E&E paper. Health-related quality of life (HRQL) has been used consistently to replace terms for quality of life in examples.

Administrative information

SPIRIT-5a-PRO Elaboration

Specify the individual(s) responsible for the PRO content of the trial protocol.

Example

Trial name: multicentre randomized controlled trial of conventional versus laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme (EnROL)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°

EnROL Trial Management Group

Chief Investigator/Clinical Coordinator

RK, [address, telephone]

Co-Investigator

DK, [address, telephone]

Deputy Clinical Coordinator

TR, [address, telephone]

Trial Management/QA

SP, [address, telephone]; JB, [address, telephone], LD, [address, telephone]; AF, [address, telephone]

Nurse Advisor

SB, [address, telephone]

Statistics

SD, [address, telephone]

Health Economics

PF, [address, telephone]

Quality of Life

JMB, [address, telephone]

Translational Science Advisor

PQ, [address, telephone]

Collaborating Surgeons

HW, [address, telephone]; MG, [address, telephone].27

Explanation

For trials assessing PROs, input from a person with expertise in PRO methodology early in the development phase of the protocol will improve its completeness and quality.10 Providing names and contact details of those contributing to the PRO-specific aspects of the protocol provides recognition, accountability and transparency. It aids identification of competing interests and prevents ghost authorship. It also provides a named point of contact to resolve any PRO-specific queries from other research team members, protocol reviewers and sites (during trial start-up and conduct). Acknowledgements of PRO protocol input from patient-partners as per guidelines for the reporting of patient and public involvement is also recommended.28 Patient and public involvement in all aspects of trial design, including but not limited to: selection of outcomes and measures, timepoints, mode of assessment and reporting, can help minimise burden and ensure that data collected is patient-centred and relevant to participants and to the future patients who will benefit from the research.

Only 7 of 75 (9%) protocols that included PROs from the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme explicitly described who was responsible for the PRO component (online supplemental 1).3

SPIRIT-6a-PRO Extension

Describe the PRO-specific research question and rationale for PRO assessment and summarise PRO findings in relevant studies.

Example

Trial name: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of idelalisib (GS-1101) in combination with rituximab for previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

PRO endpoints: 2°

Endpoint selection rationale

Health-related quality of life

‘Direct patient reporting of outcomes using standardised methods has become an increasingly important component of therapeutic assessment. Evaluation of PROs is particularly relevant in patients who cannot be cured of disease (Reference).

PRO questionnaires have been previously used in CLL to understand how patients differ from the general population in terms of health concerns (References), to understand differences in perceptions of well-being in younger versus older patients (References), to determine how treatment affects HRQL (References), and to assess the pharmacoeconomic cost of improvements in HRQL (Reference).

Patients with CLL have overtly impaired well-being relative to comparable controls (References). Fatigue is cited as a common complaint, being present in the substantial majority of patients. Impairment of HRQL prior to any treatment is apparent in those with B symptoms or in patients with anaemia, supporting the concept of initiating treatment when patients experience symptomatic disease. Factors associated with lower overall HRQL have included older age, greater fatigue, severity of comorbid health conditions, advanced stage and ongoing treatment for CLL (Reference). Younger patients appear to have worse emotional and social well-being but older patients experience worse physical HRQL (Reference). In comparative evaluation of chemotherapy-containing regimens, differences in HRQL between therapies (eg, fludarabine vs fludarabine-cyclophosphamide vs chlorambucil) reflected differences in toxicity while greater efficacy was associated with improved HRQL (References).

In this phase III study of GS-1101 and rituximab, it is postulated that incremental GS-1101-mediated tumor control will be correlated with greater positive changes in HRQL and that assessments of the drug’s safety profile will be supported by HRQL evaluations.’29

Explanation

A summary of available PRO evidence and a clearly defined PRO question is required in the background section of the protocol, or a dedicated PRO section if appropriate. Researchers should demonstrate the need for the research and identify the PRO-specific research question to demonstrate the scientific approach and integrity of the PRO study. This should include a review of existing PRO evidence from relevant trials and observational studies (eg, same/similar target population or intervention). This will avoid duplication of research, establish the burden of disease from the patient perspective, identify likely effects of treatment and inform objectives, hypotheses, selection of measures, endpoint definition and analyses (covered by subsequent SPIRIT-PRO items).

Many protocols include PROs without specifying the PRO-specific research question and without a rationale or any reference to PROs in related studies.3 4 9

Provision of this information can inform and motivate research personnel to take note of PRO assessment methods and adhere to standardisation of PRO assessment (eg, when, where, how and who of PRO assessment, as outlined in the protocol under subsequent SPIRIT-PRO items).6 11 Staff who understand the importance of PROs in a trial are able to share this understanding with participants. The combined effect of motivated and co-operative staff and participants may help reduce missing PRO data rates.30 This information is also relevant to research ethics committees/institutional review boards (IRBs) and funders responsible for reviewing the scientific integrity and ethical aspects of the trial.

SPIRIT-7-PRO Extension

State-specific PRO objectives or hypotheses (including relevant PRO concepts/domains).

Examples

Trial group name: Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG)

Trial name: a randomised phase III trial of high-dose palliative radiotherapy (HDPRT) versus concurrent chemotherapy+HDPRT (C-HDPRT) in patients with good performance status, locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with symptoms predominantly due to intrathoracic disease who are not suitable for radical chemo-radiotherapy (TROG 11.03 P-LUNG GP)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°

Objectives

‘The primary objective is to compare, in this group of patients, HDPRT versus C-HDPRT, with respect to

the relief of dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis and chest pain as assessed by change in total symptom burden from baseline to 6 weeks after the completion of treatment;

response for each component symptom separately (dyspnoea, cough, haemoptysis, chest pain).

The secondary objectives are to compare the two regimens in terms of dysphagia during treatment, thoracic symptom response rate, duration of thoracic symptom response, HRQL, toxicity, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival.

The exploratory/tertiary objectives are

to determine how much improvement in HRQL and symptom palliation would be necessary to make the inconvenience due to the longer duration of radiotherapy of C-HDPRT worthwhile, relative to HDPRT. This objective will be addressed in the patient preferences substudy;

to analyse serum protein glycosylation changes and exosomes to identify potential biomarkers of disease response and progression. Prospectively collect and bank tumour tissue and blood samples from this cohort of patients for future evaluation of potential biological markers.’31

Trial name: evaluating different rate control therapies in permanent atrial fibrillation: a prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint trial comparing digoxin and beta-blockers as initial RAte control Therapy Evaluation in permanent Atrial Fibrillation (RATE-AF)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°, exploratory

Hypothesis

‘Null hypothesis for primary outcome: no difference in patient-reported quality of life (measured using the physical functioning domain of the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) questionnaire) when comparing a strategy of digoxin versus beta-blocker therapy for initial rate control in patients with permanent AF.

Alternative hypothesis: use of digoxin or beta-blocker therapy as initial rate control in patients with permanent AF is superior based on patient-reported quality of life (measured using the physical functioning domain of the SF-36 questionnaire).

Primary objective

Patient-reported quality of life (HRQL), with a predefined focus on physical well-being using the SF-36 physical component summary at 6 months.

Secondary objectives

Generic and AF-specific patient-reported HRQL using the SF-36 global and domain-specific scores, the Atrial Fibrillation Effect on QualiTy of Life (AFEQT) overall score and the 5-level EQ-5D version (EQ-5D-5L) summary index and visual analogue scale at 6 and 12 months.

Echocardiographic left ventricular ejection fraction and diastolic function (E/e’ and composite of diastolic indices) at 12 months.

Functional assessment, including 6-min walking distance achieved, change in European Heart Rhythm Association class and cognitive function at 6 and 12 months.

Change in B-type natriuretic peptide levels as a surrogate for total cardiac strain at 6 months.

Change in heart rate from baseline and group comparison using 24-hour ambulatory ECG.’32

Explanation

The PRO objectives should reflect the research question to be addressed in the trial (SPIRIT-6a-PRO Extension) and be described in the context of the population, intervention, comparator, outcome and timepoint and the estimand framework.33 Study objectives may focus on measuring treatment benefit (superiority), non-inferiority, equivalence. Alternatively, or in addition to one of these objectives, the trial may focus on assessing the safety and tolerability from the patient perspective, or may be more exploratory in nature, where results are presented but no comparative conclusions can be drawn. The PRO-specific study objectives need to clearly align with the proposed analyses methods (SPIRIT-20a-PRO Elaboration). Critically, as described in work by the Setting International Standards in Analysing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoints (SISAQOL) Consortium,34 four key attributes need to be considered a priori for each PRO domain:

Broad PRO research objective/research question.

Between-group PRO objective.

Within-treatment group PRO assumption for the treatment or control arm.

Within-patient/within-treatment PRO objective (please note this component of the objective directly addresses the SPIRIT-12-PRO Extension).

More detailed information on how these can be applied are described in the SISAQOL consensus recommendations.34 Although the SISAQOL recommendations were published for oncology trials, the principles apply more broadly. Prespecification of objectives and hypotheses encourages identification of key PRO domains and timepoints. This is particularly important because PRO data are multidimensional in two important ways. First, there is often more than one relevant PRO in a trial, particularly when the high-level outcome of interest is HRQL. Many HRQL questionnaires yield separate scores for distinct dimensions, such as physical, emotional and social functioning, as well as key symptoms such as fatigue and pain. Second, PRO assessments are typically scheduled at several timepoints during a trial, such as baseline, end of treatment, then a series of long-term follow-ups. Prespecification of objectives and hypotheses—focussing on the most important PRO domains and timepoints—is a good way to reduce multiple statistical testing and avoid selective reporting of PROs based on statistically significant results. Exploratory, hypothesis generating, analyses can also be undertaken but should be specified as such in the final trial report.19 This links to the SPIRIT-20a-PRO Elaboration, which includes plans for addressing multiplicity/type 1 (α) error. The objectives are generally phrased using neutral wording (eg, ‘to compare the effect of treatment A vs treatment B on fatigue’) rather than in terms of a particular direction of effect.2 35 In contrast, the PRO hypothesis states the predicted effect of the interventions on the trial outcomes (eg, ‘patients allocated to treatment A will have less fatigue than those allocated to treatment B’).36–38

Despite the importance of clearly defined PRO objectives and hypotheses, a review of trial protocols determined that 23% failed to include PRO-specific objectives and 81% were missing a clear PRO hypothesis.3

Methods: participants, interventions and outcomes

SPIRIT-10-PRO Extension

Specify any PRO-specific eligibility criteria (eg, language/reading requirements or prerandomisation completion of PRO).30 If PROs will not be collected from the entire study sample, provide a rationale and describe the method for obtaining the PRO subsample.

Example

Trial group name: South West Oncology Group (SWOG)

Trial name: health status and quality of life in patients with early stage Hodgkin’s disease: a companion study to SWOG-9133 (SWOG S9208)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°

‘Eligibility criteria

Ages eligible for study: 18 years and older (adult, older adult)

Sexes eligible for study: All

Accepts healthy volunteers: No

Sampling method: Non-probability sample

Study population: community sample.

Criteria: disease characteristics: patients must be eligible for and registered to SWOG-9133.

Patient characteristics: patients must be able to complete the questionnaires in English. If they are not able to complete questionnaires in English, patients may be registered to SWOG-9133 without participating in SWOG-9208.’

The Symptom and Personal Information Questionnaire #1, the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System Short Form and Cover Sheet must be completed prior to registration and randomisation on SWOG-9133.39

Explanation

Any eligibility criteria relevant to PRO assessment should be considered during the trial design and clearly specified in the protocol for consistent use by research personnel. In some trials, the baseline PRO assessment is required before randomisation as an eligibility criterion.30 This helps to ensure there will be a valid baseline questionnaire from all patients, which is essential for calculation of change scores, or inclusion as a covariate in modelling longitudinal PRO data. For unblinded trials, this also ensures PRO data are collected before participants are aware of the randomisation which may affect some aspects of the participant’s response, for example, anxiety/emotional well-being.40 In the absence of such an eligibility criterion, there is a risk that the baseline assessment may be conducted after randomisation but before the intervention is administered, resulting in detection bias. The maximum time between this assessment and randomisation should be defined and should not be too long.

It may not always be possible to collect PROs from all study participants, for example, due to non-availability of questionnaires in appropriate languages (see SPIRIT-18a(iii)-PRO Extension),9 literacy requirements or due to cognitive function (see SPIRIT-18a(iv)-PRO Extension). These PRO-relevant exclusions typically should not preclude the affected participants from enrolling in the trial, unless the PRO is the primary outcome. Evidence suggests eligibility criteria as stated in trial protocols often differ from what is finally reported in the trial publication,41 and data on use of other language or culturally appropriate PRO instruments is often missing from the protocol.13 42

Where the needs of specific groups have been identified (eg, not fluent in English) but not accommodated in the study protocol (eg, non-English language versions not available, assistance with reading and writing English version not permitted), this should be stated, and the rationale for the sampling method described and justified. Trialists should aim to be as inclusive as possible. Given the significance of PROs, the research community has a moral obligation to, where possible, to address gaps in availability of culturally validated PRO instruments. In the meantime, the implications for generalisability of findings should be discussed in subsequent publications.19

SPIRIT-12-PRO Extension

Specify the PRO concepts/domains used to evaluate the intervention (eg, overall HRQL, specific domain, specific symptom) and, for each one, the analysis metric (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event) and the principal timepoint or period of interest.

Examples

Trial name: evaluating different rate control therapies in permanent atrial fibrillation: a prospective, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint trial comparing digoxin and beta-blockers as (RATE-AF)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°, exploratory

Primary outcome

‘Patient-reported quality of life (HRQL)—SF-36 physical component summary score at 6 months.

Secondary outcomes

Patient-reported HRQL

SF-36 global and domain-specific scores at 6 and 12 months.

EQ-5D-5L summary index and visual analogue scale at 6 and 12 months.

AFEQT overall score at 6 and 12 months.’32

Trial name: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy and safety of idelalisib (GS-1101) in combination with rituximab for previously treated CLL

PRO endpoints: 2°

‘Change in HRQL domain and symptom scores based on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy: Leukaemia (FACT-Leu)—defined as the change from baseline and the time to definitive increments or decrements of 10%, 20% and 40% from baseline; time to definitive increment (better than baseline by the specified amount) is the interval from randomisation to the first timepoint when the HRQL measure is consistently better than at baseline (including that timepoint as well as all the subsequent timepoints) in a subject whose last HRQL score is better than at baseline; and time to definitive HRQL decrement (worse than baseline by the specified amount) is the interval from randomisation to the earliest of death or the first timepoint when the HRQL measure is consistently worse than at baseline (including that timepoint as well as all the subsequent timepoints) in a subject whose last performance status score is worse than at baseline.’29

Explanation

For each outcome, including PROs, the trial protocol should define four components: the specific measurement variable, which corresponds to the data collected directly from trial participants (eg, Beck Depression Inventory score, all-cause mortality); the participant-level analysis metric, which corresponds to the format of the outcome data that will be used from each trial participant for analysis (eg, change from baseline, final value, time to event); the method of aggregation, which refers to the summary measure format for each study group (eg, mean, proportion with score >2) and the specific measurement timepoint of interest for analysis.1 Many PRO questionnaires are multidimensional, assessing multiple facets of the impact of a disease and its treatment and usually include multiple assessments over the course of the trial. The multidimensional nature of PROs is most apparent in HRQL questionnaires, which often include various aspects of functioning and symptoms, which are often scored as distinct ‘domains’. These domains may not be affected equally by the trial interventions. The SPIRIT-7-PRO Extension encourages protocol writers to identify the domains that are most likely to be affected in the trial objectives and hypotheses, drawing on previous evidence (SPIRIT-6a-PRO Extension). The SPIRIT-12-PRO Extension item reinforces the statement of these key domains, and also the most important timepoints (ie, where greatest impact of interventions are expected), and develops that concept further by encouraging protocol contributors to think about how these PRO domains and timepoints will be analysed, that is, the analysis metric.34 To ensure transparency and credibility of the analysis, it is recommended that there is prespecification of the PRO concepts/domains, analysis metric(s) and timepoint(s) of interest, whether the PRO is a primary, secondary or exploratory outcome. These should closely align with the study hypotheses/objectives and the nature and trajectory of the disease or condition under investigation.34 43 The selected key domains, timepoints and analysis metric should be used to specify the PRO endpoints, integrated in the full endpoint model of the trial.

A clearly defined endpoint model, organising all trial outcomes (PRO and non-PRO), typically in primary, secondary and exploratory endpoints, allows rigorous control of the evidence demonstration, especially the control of the statistical testing. Each PRO endpoint in the model should explicitly specify a single domain and a single time horizon. The endpoint model enables procedures for type I error control (risk of false positive finding) (see SPIRIT-20a-PRO Elaboration). Broadly, the concepts and domains (sub concepts) measured by a PRO may be ‘proximal’ in nature, that is, direct impact of the disease and treatment (eg, symptoms such as pain, fatigue, nausea, rash and anxiety) or more distal, ‘knock-on’ effects, (eg, functional status and global quality of life), as illustrated for ovarian cancer in (figure 1, inspired by the Wilson and Cleary model44). Of note, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are increasingly focused on the individual measurement of well-defined concepts that impact on HRQL but are more proximal to a therapy’s effect on the patient and the patient’s disease: symptomatic adverse events, physical function and, where appropriate, a measure of the key symptoms of the disease.45

Figure 1.

Proximal and distal effects of therapy on patient symptoms and quality of life. Adapted from Wilson and Cleary.44

Common analysis metrics may include magnitude of event at time t, proportion of responders at time t, overall PRO score over time or response patterns/profiles. These should be prespecified alongside the levels of statistical and clinical significance for the study and any responder definition in use.16 Timepoints for analysis should be chosen to best address the research question, while taking into account aspects such as the natural history of the disease/condition and its treatment, the PRO measurement properties and recall period and participant completion burden.16 46

The example, idelalisib and rituximab improve PFS over rituximab alone in unfit patients with relapsed CLL: a phase III study, illustrates a ‘time to event’ PRO endpoint or analysis metric, where the event is definitive improvement or definitive deterioration in a PRO. This approach allows repeated PRO measurements to be converted to a single measure: time to definitive increment or decrement. This requires quite complex and specific criteria for degree and duration of change. Also, this particular example does not specify any key domains of the FACT-Leu, but rather applies this analysis metric to all HRQL domain and symptom scores. In contrast, the RATE-AF example identifies a single score (the SF-36 physical component score), and a specific timepoint (6 months) as the primary outcome, with other SF-36 domains, questionnaires and timepoints specified as secondary outcomes.

SPIRIT-13-PRO Extension

Includes a schedule of PRO assessments, providing a rationale for the timepoints and justifying if the initial assessment is not prerandomisation. Specify time-windows, whether PRO collection is prior to clinical assessments, and, if using multiple questionnaires, whether order of administration will be standardised.

Examples

Trial group: TROG

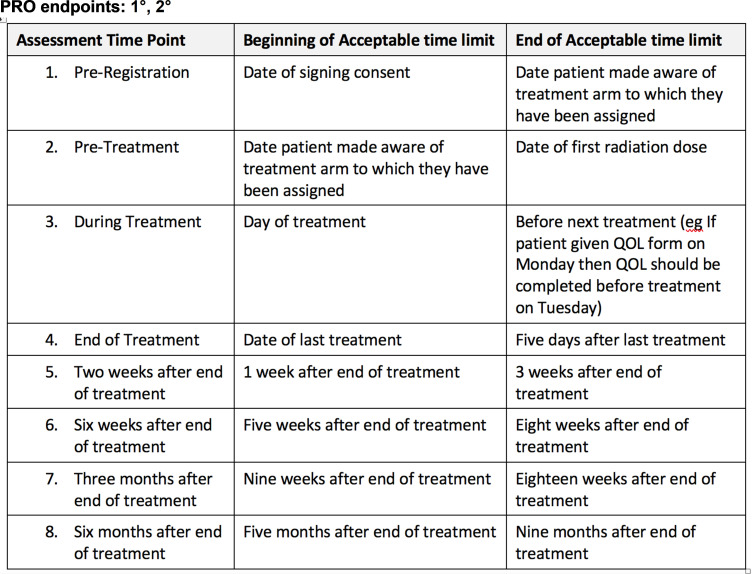

Trial name: a randomised phase III trial of HDPRT versus concurrent C-HDPRT in patients with good performance status, locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with symptoms predominantly due to intrathoracic disease who are not suitable for radical chemo-radiotherapy (TROG 11.03 P-LUNG GP) (figure 2).31

Figure 2.

Example schedule of patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessments in the Trans Tasman Radiation Oncology Group 11.03 P-Lung GP Trial. QoL, quality of life.

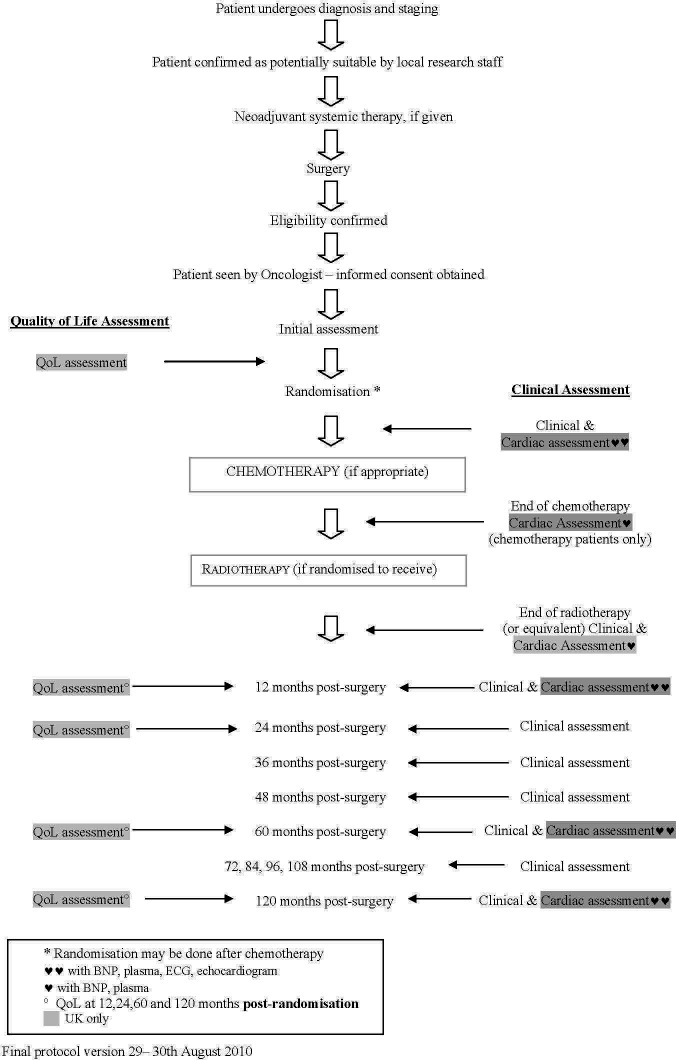

Trial group: UK Medical Research Council Scottish Cancer Trials Breast Group in association with: Breast International Group

Trial name: MRC phase III randomised trial to assess the role of adjuvant chest wall irradiation in ‘intermediate risk’ operable breast cancer following mastectomy (MRC SUPREMO TRIAL (BIG 2–04) (figures 3 and 4))

Figure 3.

Example schedule of patient-reported outcome assessments in the MRC SUPREMO TRIAL (BIG 2–04).140 BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; QoL, quality of life.

Figure 4.

Flow diagram schedule of patient-reported outcome assessments in the MRC SUPREMO TRIAL (BIG 2–04).140 BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; QoL, quality of life.

Explanation

A clear and concise schedule of PRO assessments (figures 2–4) can: assist trial staff to be organised and prepared for participant visits, inform study participants about the methods and expectations of trial participation and facilitate review of participant burden by research ethics committees/IRBs.30 The scheduled PRO assessments should provide the data required to address the study’s PRO objectives. When selecting appropriate timepoints for assessment, it is important to consider the natural history of disease/progression, the hypothesised impact of therapy over time and practical considerations such as alignment of assessments with clinic visits and recall period of PRO measures. PRO assessments should be described in the protocol text and in the schedule of assessment table along with the other clinical data collection activities, for ease of reference. This is recommended whether the PRO is completed by the participant during study visits or outside of the study visits (eg, at home).

The timing of the baseline PRO assessment relative to other study-related events is important and therefore should be specified in the schedule of assessments. Collecting PRO data prior to randomisation helps ensure an unbiased baseline assessment, and if specified as an eligibility criterion, can promote data completeness (SPIRIT-10-PRO Extension). Baseline PRO data are often used as a covariate in analyses and are essential to calculating change from baseline, however, collecting data from enrolled patients prior to randomisation can be logistically challenging. One approach is to have participants complete the baseline PRO assessment immediately after providing consent, while the site staff obtain the randomisation assignment from the study system. However, there may be scenarios in which prerandomisation PRO assessment is unnecessary or not possible, for example, emergency surgery trials.

Stating the time-windows for each PRO assessment clearly in the protocol text and schedule of assessments table or footnote will help staff adhere to them. Examples of time-windows for PRO assessment are similar to time-windows for other types of assessments, such as a study visit that may occur on day 10–14 postbaseline, or on day 30±3 days postsurgery. Time-windows for each scheduled PRO assessment require an unambiguous reference point, to ensure that PRO data collection captures clinically relevant timepoints of interest. In deciding the size of the time-window for a PRO assessment, consider the trade-off between a smaller, more precise, time-window and a larger more feasible window. One approach is to specify a time-window that is a little larger than the ideal and not allow exceptions; this approach is more consistent than setting a smaller time-window and allowing exceptions. Often PRO assessments that occur during active treatment, for example, chemotherapy, have a smaller time-window to capture acute toxicity that arise and resolve relatively quickly, while those occurring many months or years after treatment completion can have a larger window if the participant’s outcomes are expected to stabilise over time.

When the PRO assessment occurs during a research or clinic visit, it is recommended that PRO assessment is standardised to be completed prior to clinical consultation, assessments or procedures. For example, if a PRO instrument assesses participants’ experiences of pain in the past 7 days, and the study visit includes a bone marrow biopsy, the schedule of assessments should indicate that the PRO assessment be completed prior to the biopsy. This will prevent the pain assessment from capturing pain associated with the biopsy, reduce risk of missing data as participants may not feel well enough to complete PROs following their procedure and offer a ‘routine’ for study staff responsible for data collection.

When more than one PRO questionnaire is scheduled, it is recommended that the order of questionnaires is standardised, with those higher in the endpoint hierarchy being collected first.

These two forms of standardisation of PRO administration are examples of the more general principle in research methodology that standardisation of methods reduces unwanted sources of variation, whether random (ie, no net effect on estimates of interest, such as the impact of interventions on PROs) or systematic (ie, causing bias).

SPIRIT-14-PRO Elaboration

When a PRO is the primary endpoint, state the required sample size (and how it was determined) and recruitment target (accounting for expected loss to follow-up). If sample size is not established based on the PRO endpoint, then discuss the power of the principal PRO analyses.

Examples

Trial name: the chronic autoimmune thyroiditis quality of life selenium trial (CATALYST)

PRO endpoints: 1°

‘The primary outcome is thyroid-related quality of life during 12 months’ intervention, as measured by a composite score from the ThyPRO questionnaire. Sample size estimation is based on this outcome.

The trial should be sufficiently powered to identify a difference between the intervention and the control group of 4 points on the 0–100 ThyPRO composite scale, corresponding to a small to moderate effect. In previously obtained data, the SD of ThyPRO-scores (sigma level) was 20 points. With a correlation between observations on the same participant of 0.50, and a power of 80% and a type I error probability (two-sided α level) of 0.05, a sample size of 236 experimental participants and 236 control participants is required. The sample size estimate is based on a design with five repeated measurements having a compound symmetry covariance structure’.47

Trial name: cosmesis and body image after single-port laparoscopic or conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multicentre double-blinded randomised controlled trial (SPOCC-trial)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°

‘The primary endpoint of the study concerns patient’s satisfaction with cosmesis and body image 12 weeks after surgery. This endpoint is assessed using a validated cosmesis and body image score (CBIS) that was previously used in surgery for Crohn’s disease and in donor nephrectomy. This score is calculated on an 8-item multiple choice type questionnaire ranging between 8 and 48 points.

A clinically relevant improvement of the CBIS is defined as an improvement of 20% of the cosmesis score (8 points). Given the reported SD of the CBIS between 4 and 6 and using (alpha=0.05 and beta=0.90), two groups of 49 patients are needed. This is based on a two-sided significance level (alpha) of 0.05 and a power of 0.90. Estimating a 10% dropout rate, which is common in randomised controlled trials, 55 patients will be randomised per arm.’48

Trial group: TROG

Trial name: a randomised phase III study of radiation doses and fractionation schedules for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (BIG 3-07/TROG 07.01)

PRO endpoints: 2°

The sample size for this trial, based on the primary endpoint (time to local recurrence of invasive or intraductal breast cancer in the ipsilateral breast), was 1600 patients. The sample size for the PRO substudy was determined a priori, and was less than that required for the primary endpoint, as explained in the protocol excerpt below. Therefore, patients recruited after the PRO-specific target sample size was achieved did not complete PRO questionnaires, saving trial resources in data collection and management.

‘Sample size determination: for the quality of life study aiming to detect a difference between the tumour bed boost and no boost groups of 0.2 SD of a continuous scale such as fatigue or physical symptoms, with 80% power at a two-sided alpha level of 5%, the required sample size is 790 patients. To allow for attrition at a rate of 5% per year, 1020 patients are required to participate in the quality of life study.’49

Explanation

As with any primary endpoint, including those that focus on PRO, the criteria and methods for estimating the necessary sample size should be specified, with adjustments for expected discontinuation from the clinical study.46 Ideally, the criteria for clinical significance (eg, minimal important difference, clinically meaningful within-patient change threshold, responder definition) should be specified when known.50 51 It is important to note that the FDA is more interested in what constitutes a meaningful within-patient change in score from the patient perspective.16

In cases where the PRO is specified as a key secondary endpoint, the statistical power based on the estimated sample size for the primary endpoint, should be determined. If overpowered, specifying a smaller PRO-specific sample size will save trial resources, as illustrated in the BIG 3–07/TROG 07.01 example. When sufficient power may be achieved by collecting PROs from a representative subset of participants, the sampling strategy should be clearly described.

Only 50.7% of NIHR Health Technology Assessment clinical trial protocols address sample size and statistical power for PRO specified as secondary endpoints.3 If the clinical trial is international in scope, the sampling across countries may be influenced by availability of language translations.52 In addition, the variability of measurement between countries may inflate type 2 error (reduces power).

Methods: data collection, management and analysis

SPIRIT-18a(i)-PRO Extension

Justify the PRO instrument to be used and describe domains, number of items, recall period, instrument scaling and scoring (eg, range and direction of scores indicating a good or poor outcome). Evidence of PRO instrument measurement properties, interpretation guidelines and patient acceptability and burden should be provided or cited if available, ideally in the population of interest. State whether the measure will be used in accordance with any user manual and specify and justify deviations if planned.

Examples

Trial name: impact of a multimodal support intervention after a ‘mild’ stroke (YOU CALL-WE CALL)

PRO endpoints: 1°, 2°

‘A number of quality of life tools were reviewed (eg, SF-36, Stroke Impact Scale, Quality of Life Index (QLI)) and the tool chosen was a compromise between psychometric properties and adequacy of content for mild stroke. The 32-item questionnaire QLI (Reference) which was developed from Ferran’s conceptual model of quality of life and which has been used with a stroke clientele (Reference) was chosen as the primary outcome. Each item of the QLI as relating to four life domains (health and functioning, socioeconomic, psychological/spiritual and family), is evaluated in terms of satisfaction and importance on a 6-point scale. Scores for each domain and a global score are expressed from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating a better quality of life. These four life domains relate well with the main issues covered through the WE CALL intervention. It has shown to have adequate psychometric properties (concurrent validity, test–retest reliability and high internal consistency: a=0.90) (Reference) and thus should be responsive to therapy-induced change (Reference). A 1-point difference was observed in the first 6 months poststroke descriptive follow-up (n=63) for an effect size of 0.33 (Reference). A 2-point difference is considered a clinically meaningful change leading to a moderate effect size of 0.66.’53

Trial name: a randomised phase II/III multicentre clinical trial of definitive chemoradiation, with or without cetuximab, in carcinoma of the oesophagus (SCOPE 1: Study of Chemoradiotherapy in Oesophageal Cancer Plus or Minus Erbitux)

PRO endpoints: 2°

HRQL instruments

‘Generic domains of HRQL will be assessed with the EORTC core Quality of Life Questionnaire, the EORTC QLQ-C30 (Reference). This instrument has been well validated in many international clinical trials in oncology including oesophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer. Disease-specific and Chemoradiotherapy (CRT)-associated symptoms and side effects will be assessed with the oesophageal cancer-specific module, the EORTC QLQ-OES18 (Reference). This has been validated and tested in patients receiving definitive CRT. The module includes scales assessing dysphagia, eating restrictions, reflux, dry mouth and problems with saliva and deglutition. The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) will also be administered (Reference). This is a well-validated, easy-to-use index which assesses the impact of dermatological conditions on patients’ HRQL (Reference). It has been included to accurately assess the impact of the acneiform eruption commonly seen with cetuximab.’54

Explanation

The justification for the selection of PRO instrument(s) is required in the trial protocol. This will help trial personnel and participants understand why specific measures are being used and how they directly address the trial objectives and stakeholder needs.11 For example, regulatory agencies often focus on physical symptoms and functioning to inform licensing and labelling claims, whereas patients and health-policy makers may be more interested in broader aspects of HRQL, such as engaging in social activities and emotional well-being.55 56 For regulatory trials, it is prudent to seek regulatory advice at an early stage of trial development regarding the acceptability of the instrument and the approach to PRO assessment. Stakeholder-relevant PROs can be identified through patient involvement, qualitative research or core outcome sets,56 57 which alongside clinical outcomes, often include outcomes such as symptom burden, functioning, and disease control, which can be measured using PRO instruments.

Appropriately developed and evaluated PRO instruments can provide more sensitive and specific measurements of the effects of medical intervention, thereby increasing the efficiency of clinical trials that attempt to measure the meaningful treatment benefits of those therapies.58–60 Irrespective of whether the trial is conducted for regulatory purposes, FDA guidance and ISOQOL guidance provide a useful conceptual framework to assist in the selection of measures.16 61 Identifying and selecting valid, reliable tools that are acceptable to patients from the target population may prove challenging. The Consensus Based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COMET) initiative and the Evaluating the Measurement of Patient Reported Outcomes programme provide useful guidance to support the review of measurement properties.56 62 63

Ideally, the PRO instrument(s) will have been validated in the target population and this evidence cited. This will help reviewers understand if claims being supported by the PRO instrument can be substantiated by the evidence for using that instrument in that, or a related, population. Further details on the domains, number of items, recall period, instrument scaling and scoring (eg, range and direction of scores indicating a good or poor outcome) should be provided. This will assist trial personnel in the collection and analysis of the PRO data. Questionnaires should be used in accordance with user manuals to promote good data quality and ensure standardised scoring. Deviations from user manuals or different ways of capturing PRO data may invalidate the measure; therefore, any deviations should be declared and transparently reported.19

If in the trial there are plans to use a questionnaire which has not been validated in the trial’s target population, or if a new instrument is being developed alongside the trial, it is important to explain this in the protocol. Including an outline of any plans for the evaluation of its measurement properties using the trial data, if this will be undertaken, and if not why. This should be in accordance with established current guidelines for PRO validation.64

Although all the reviewed NIHR Health Technology Assessment clinical trial protocols identified the PRO instrument to be used in the trial, few justified their use in relation to the study hypotheses, PRO instrument measurement properties or expected participant burden (41.3%, 37.3% and 14.7%, respectively).3

Patient partners involved in the design of the study can assist with the selection of PRO instruments and provide feedback on the likely acceptability of the questions, and participant burden (eg, time taken for completion, cognitive burden, emotional burden, repetition across questionnaires).65 The number of PRO instruments/questions to be assessed in a trial requires careful justification. Minimising participant burden has been identified as a strategy to reduce risk of missing PRO data, improve recruitment and retention.30

SPIRIT-18a(ii)-PRO Extension