Abstract

Background:

Although systemic reactions (SRs) to subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) injections are not uncommon, life-threatening and fatal reactions are rare. The annual incidence of injection-related SRs of varying severity is not well-defined.

Objective:

To determine the annual frequencies of SCIT reactions in North America via a longitudinal surveillance program initiated among practicing allergists in 2008.

Methods:

Physicians were asked to complete a Web-based survey reporting numbers of injections administered, injection- and skin test-related fatal reactions, and all nonfatal SRs in their clinical practices during the previous 12 months. The SR events were classified as mild (grade 1: cutaneous or upper respiratory symptoms), moderate (grade 2: asthma with reduced lung function), or severe (grade 3: life-threatening airway compromise or hypotension).

Results:

In the initial year of the program, 806 physicians responded, representing 1,922 SCIT prescribers. No fatal reactions to SCIT injections were identified during the first 12 months, although 6 SCIT fatal reactions were reported retrospectively between 2001 and 2007. Eighty-two percent of practices reported 8,502 SRs to SCIT (10.2 SRs per 10,000 = 0.1% of injection visits). Most were grade 1 (74%) or grade 2 (23%) SRs. However, 3% (n = 265) were grade 3 anaphylactic events (3 severe reactions for every 100,000 injection visits).

Conclusions:

We demonstrated the feasibility of annual surveillance of SRs associated with SCIT injections. This surveillance study will continue to monitor SCIT adverse events in parallel with vigorous efforts instituted by members of professional organizations aimed at reducing the risk of severe reactions.

INTRODUCTION

Subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy (SCIT) is effective in treating allergic rhinitis, asthma, and stinging insect (Hymenoptera) hypersensitivity.1–4 The benefit of SCIT, however, has been tempered by the risk of severe systemic reactions (SRs) and rare anaphylactic fatal reactions (FRs).5–8 Three retrospective surveys5,9,10 conducted in North America confirmed 76 SCIT-related FRs occurring between 1945 and 2001. From these data, FRs have been estimated to occur in every 2.5 million injections (or 3.4 deaths per year) and near-fatal reactions (NFRs) after every 1 million injections (or 4.7 NFRs per year).5,6 Twenty-six SCIT-related anaphylactic deaths were reported in the United Kingdom in a 10-year period.11 Based on these retrospective surveys, a variety of factors that contribute to SCIT FRs have been identified, including (1) the presence of uncontrolled asthma, (2) errors in dosing and administration of injections, (3) delay or failure to administer epinephrine, (4) previous SCIT-related SRs, (5) an inadequate post injection waiting period and(6) administration of injections in suboptimal settings (eg, at home), where rare severe anaphylactic reactions cannot be successfully managed. Using lessons learned from these surveys, the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters has published clinical practice guidelines in the second update of the Allergen Immunotherapy Practice Parameter aimed at preventing SCIT NFRs and FRs.12,13 The updated parameters have been widely disseminated, presented, and discussed at American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI) and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAAI) immunotherapy meetings and at national meetings of these organizations.

To closely monitor the incidence of SRs and FRs associated with skin testing and SCIT in North America, the ACAAI and AAAAI initiated an annual surveillance program in July 2008 to track such events in the clinical practices of physician members of both societies. This initial report summarizes SCIT reactions reported during the first 12 months of the surveillance study.

METHODS

Study Population

Physician members of the ACAAI and the AAAAI were surveyed. The mailing lists of both societies were merged into a master list of eligible survey respondents. For each multimember practice, a single respondent was identified to report the annual experience of his or her practice group with SCIT and skin test reactions. When contacted, physicians were asked to respond by e-mail if they were no longer prescribing SCIT; those physicians were deleted from the list. A final list was generated of 3,249 potential respondents, each of whom was asked to describe the experience of all members of his or her practice actively prescribing SCIT, including nurse practitioners.

Study Design

To maintain the confidentiality of the respondents, all contacts with physician respondents were made exclusively through a nonphysician research coordinator. It was established a priori that physicians overseeing this surveillance study would not be privy to the identity of respondents. All potential participants were contacted by e-mail, fax, or both and were assigned a randomly generated alpha-numeric identification code to eliminate the need to enter personal or geographic identifiers on survey forms. Respondents were given the option of either completing surveys online at a dedicated Website or completing and faxing back printed forms. To optimize participation, nonresponders were contacted again by e-mail or fax approximately 4 to 6 weeks after the initial contact and, if necessary, were telephoned directly by the study coordinator to encourage participation. Physician respondents were asked to complete a 7-item questionnaire describing the entire experience of all SCIT prescribers in their respective clinical practices. The surveillance questionnaire, summarized in Table 1, queried about allergic FRs and SRs to SCIT and skin testing that had occurred in the previous 12 months in the clinical practice of the respondent. Physicians who completed the survey were also asked to report any known fatal events related to SCIT or skin testing that occurred in an outside clinical practice in their regional area. Respondents were asked to provide the numbers of mild, moderate, and severe nonfatal allergic SRs in their respective practices. Mild reactions (grade 1) were defined as generalized urticaria or upper respiratory symptoms (eg, itching of the palate and throat, sneezing). Moderate reactions (grade 2) were defined as asthmatic symptoms accompanied by a reduction in lung function (eg, a peak expiratory flow rate decrease of 20%–40%) with or without generalized urticaria, upper respiratory symptoms, or abdominal symptoms (nausea, cramping). Finally, severe reactions (grade 3) were defined as life-threatening anaphylaxis with severe airway compromise or upper airway obstruction with stridor or hypotension (with or without loss of consciousness).

Table 1.

Survey Questions

| 1. During the past 12 months, have any patients in your entire clinical practice (including patients of your associates) experienced a fatal anaphylactic reaction(s) after an allergen immunotherapy injection? |

| If yes, how many patients had fatal reactions in your entire practice during the past 12 months? ____ |

| 2. During the past 12 months, have any patients in your entire clinical practice (including patients of your associates) experienced nonfatal systemic reactions after allergen immunotherapy injections? |

| If yes, how many nonfatal systemic reactions have there been in the entire clinical practice in the past 12 months? ____ |

| According to the following severity classification system, please indicate the number of nonfatal systemic reactions in your entire practice during the past 12 months (including patients of your associates) that are best described as: |

| Grade 1 → Mild systemic reactions: generalized urticaria or upper respiratory symptoms (eg, itching of the palate and throat, sneezing). |

| Grade 2 → Moderate systemic reactions: asthma (eg, peak expiratory flow rate falls 20%–40%) with or without generalized urticaria, upper respiratory symptoms, or abdominal symptoms (nausea, cramping). |

| Grade 3 → Severe, life-threatening anaphylaxis: severe airway compromise due to severe bronchospasm (eg, peak expiratory flow rate falls >40%), or upper airway obstruction with stridor or hypotension (with or without loss of consciousness). |

| 3. During the past 12 months, are you aware of a fatal anaphylactic reaction(s) associated with an allergen injection in another practice in your community? |

| 4. During the past 12 months, are you aware of a fatal anaphylactic reaction(s) associated with allergen skin testing: |

| (a) in your practice? |

| (b) in another practice in your community? |

| 5. During the past 12 months, how many subcutaneous allergen injections has your entire practice billed under Current Procedural Terminology codes 95115 and 95117 for single and multiple injections (or other codes)? |

| 6. Please indicate the total number of allergists and nurse practitioners who write orders for (or prescribe) immunotherapy in your entire clinical allergy practice. |

Data Analysis

A statistical software program (SAS; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used to compute descriptive statistics, including the total number of injection visits for all respondents and the median number of injection visits per practice. The number of FRs in participants’ practices and in their communities was determined based on responses to survey items 1, 3, and 4 (Table 1). Participants who reported deaths in the community were contacted directly by the study coordinator to confirm the event and year of death.

The main analyses focused on nonfatal SRs. The total number of SRs and the mean and median number of reactions per practice were determined for all 806 respondents (Table 1, survey item 2). The rates of grades 1, 2, and 3 SRs per 10,000 injection visits were calculated in 746 practices with complete injection visit and reaction grading data.

Nonfatal SRs, including respective reaction grades, were compared among those practices reporting greater than or equal to vs less than the mean and median number of injection visits, with and without adjustment for the number of practitioners per practice. The 626 practices included in this analysis provided complete data regarding the occurrence of reactions, reaction severity grades, and the number of injection visits. Given that data were nonnormally distributed, we used a nonparametric analysis involving events trial syntax (modeling the proportion of "successes" with PROC GENMOD in SAS) to compare the proportions of grade 1, 2, and 3 reactions among practices giving at least the median number of injections vs those giving fewer than the median.14

RESULTS

Eight hundred six practices participated, representing 1,922 physician prescribers of SCIT. We estimated that these data reflected the annual clinical experiences of 49% of AAAAI and ACAAI members contacted. Respondents reported a total of 8.1 million SCIT injection visits during the previous 12 months, with a median of 4,700 injection visits per practice. Because single and multiple injections given at each visit could not be determined from the data provided, it is likely that the actual number of injections exceeded 8.1 million.

Fatal Reactions

There were no direct reports of deaths attributable to SCIT injections or allergen skin testing spanning the first year of the surveillance study (mid-July 2008 to mid-July 2009). Similarly, there were no indirectly reported deaths due to skin testing or SCIT injections occurring in outside community practices. Although respondents were not asked to provide information regarding FRs preceding July 2008, 6 new fatal SCIT reactions that had occurred between 2001 and 2007 were voluntarily reported. All of these events were indirect reports and occurred in outside medical practices other than those of the respondents. The study coordinator confirmed all 6 events and their approximate dates of occurrence by speaking with the reporting physicians. Respondents were not privy to specific details of the FRs. Thus, we estimated that approximately 1 FR per year occurred between 2001 and 2007 since the last published retrospective AAAAI-sponsored survey.5

Nonfatal SRs

After SCIT injections, SRs occurred in 82% of practices (660 of 806). As seen in Table 2, 8,502 SRs were reported. In the 804 practices that reported data on reaction severity, 6,293 (74%) were mild (grade 1) reactions translating to an annual mean of 7.8 (median 3.0) events per clinical practice. Providers reported 1,944 moderately severe (grade 2) SRs, representing 23% of SRs and corresponding to an annual mean of 2.4 (median 1.0) grade 2 reactions per clinical practice (Table 2). Severe, potentially life-threatening (grade 3) anaphylactic reactions were uncommon, accounting for 3% of all SRs (265 events). It is noteworthy that 76% (613 practices) reported at least 1 grade 1 SR, 54% (436 practices) reported at least 1 grade 2 SR, and 18% (144 practices) reported at least 1 grade 3 SR.

Table 2.

Severity Grade of 8,502 Total Systemic Reactions

| Severity of reaction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 Mild | Grade 2 Moderate | Grade 3 Severe | |

| All systemic reactionsa | 6,293 (74) | 1,944 (23) | 265 (3) |

| Practices experiencing event (n = 804 practices)b | 613 (76) | 436 (54) | 144 (l8) |

The number (%) of different severity grades (of 8,502 total systemic reactions).

The number (%) of practices reporting at least 1 episode of a given event (eg, ≥1 grade 1 reaction).

Physician respondents were asked to provide the annual number of billing codes filed for single and multiple injections. Based on these data, 8.1 million injection visits reportedly occurred between July 1, 2008, and July 31, 2009. Among practices that provided injection visit data (n = 748), there were 10.2 SRs (of any severity type) per 10,000 injection visits. There were 7.6 grade 1 reactions, 2.3 grade 2 reactions, and 0.3 grade 3 reactions per 10,000 injection visits in clinical practices that provided these data (n = 746).

In clinical practices that provided complete data regarding the occurrence of reactions, reaction severity grades, and number of injection visits (n = 626), the median number of injection visits was 5,217 per practice. Clinical practices reporting at least the median number of injections accounted for 76% of all grade 1 SRs, 74% of all grade 2 SRs, and 72% of all grade 3 SRs (Table 3). Because practices included variable numbers of SCIT prescribers, we also analyzed findings based on the number of practitioners per practice (Table 3). Results were similar to those based on the raw number of practices.

Table 3.

Reactions of Varying Severity Occurring in Practices/Practitioners Reporting Higher Numbers of Injection Visitsa

| Severity of reaction |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 (Mild) | Grade 2 (Moderate) | Grade 3 (Severe) | |

| Reactions occurring in practices reporting ≥5,217 injection visits (median No. of injection visits/practice), %b | 76 (4,666/6,138 reactions)c | 74 (1,402/1,899 reactions) | 72 (180/250 reactions) |

| Reactions occurring in practitioners reporting ≥3,105 injection visits (median No. of injection visits/practitioner), %d | 68 (4,201/6,135 reactions)c | 67 (1,268/1,899 reactions) | 63 (158/250 reactions) |

This analysis includes practices/practitioners providing complete data regarding number and severity grade(s) of systemic reactions and total number of injection visits.

Practices (n = 626 in this portion of the analysis) may include more than 1 practitioner.

The total number of mild reactions (the denominator) is different between the first and second row of this table because 1 practice that did not provide the number of practitioners was excluded from the analysis involving practitioners.

Practitioners refers to individual prescribers (physicians or nurse practitioners) of subcutaneous immunotherapy (n = 625 practices representing 1,559 practitioners were included in this portion of the analysis; 1 practice that did not provide the number of practitioners was excluded).

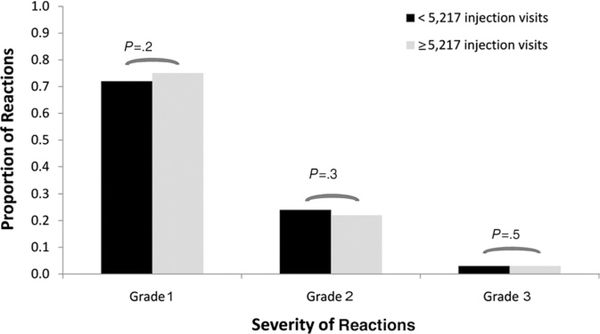

We next asked if there might be a disproportionate increase in the risk of severe reactions based on the number of injection visits relative to the increased risk of less severe reactions in practices reporting higher numbers of injection visits. In practices providing complete data (n = 626) and reporting at least the median number of injection visits per year (5,217 visits), 75% (4,666 of 6248 events) of all reported reactions were grade 1, 22% (1,402 of 6,248 reactions) were grade 2, and 3% (180 of 6,248 reactions) were grade 3. In practices with fewer than 5,217 injection visits per year, 72% (1,472 of 2,039 reactions) were grade 1, 24% (497 of 2,039 reactions) were grade 2, and 3% (70 of 2,039 reactions) were grade 3. There were no significant differences between the proportions of grade 1, 2, or 3 reactions based on the number of injection visits (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Severity of systemic reactions based on the number of injection visits. The relative proportions of grade 1, 2, or 3 reactions among practices reporting more than or less than the median number (n = 5,217) of injection visits are shown.

DISCUSSION

The benefits of SCIT are well documented, as are the potential risks of injection-related allergic SRs and rare anaphylactic FRs.5,10 Awareness of FRs with SCIT has generated considerable discussion concerning strategies to decrease the risk and occurrence of these events. Substantial information gained from retrospective surveys of SCIT FRs and NFRs have shaped practice parameters and guidelines, including the most recently published second update of the Allergen Immunotherapy Practice Parameters.12,13

Based on previous retrospective surveys,5,10 the estimated frequency of SCIT-related FRs is 1 per 2.0 to 2.5 million injections. However, FRs associated with SCIT occurring after 2001 have not been evaluated in North America until this surveillance study was initiated in 2008. Although we did not request that physicians report FRs occurring before 2008, respondents voluntarily reported 6 new SCIT-associated FRs known to have occurred outside their own clinical practices between 2001 and 2007. This translated into approximately 1 SCIT FR per year. Each of these reports was subsequently confirmed by contacting physician respondents. Because these were indirectly reported, we could not contact treating physicians to obtain more specific details of FRs. It cannot be ascertained how accurately these incidental reports reflect the actual number of FRs occurring during that period. Nevertheless, it is clear that FRs had occurred between 2001 and 2008.

As already stated, there are inherent limitations in conducting retrospective surveys to monitor FRs and NFR events occurring across multiple years. We anticipated that institution of an annual reporting system could improve relatively low participation rates (approximately 25%) in previous retrospective surveys of serious life-threatening SCIT reactions and diminish recall bias and underreporting associated with less frequently conducted studies.5,9,10 For these reasons, this annual surveillance study of SCIT SRs was initiated in 2008 under the auspices of the ACAAI and the AAAAI to closely monitor and determine annual incidences of FRs and NFRs.5,9 In contrast to previously published retrospective studies of FRs, the aim of this surveillance project was not directed at identifying the already well-defined risk factors associated with life-threatening anaphylactic reactions to SCIT injections. Indirectly, we sought to determine whether greater awareness of risk factors for FRs and NFRs and adherence to recent recommendations aimed at reducing risk contained in the recent Allergen Immunotherapy Practice Parameter (second update) may have been associated with a decline in FRs after 2007 compared with previous experience defined by the aforementioned retrospective surveys.5,9,10 It is noteworthy that in the first 12 months of the study, not a single fatal reaction was reported after skin testing or a SCIT injection either directly or indirectly by a physician responding to this survey. Although this 1-year result is promising and suggests that the frequency of FRs may be trending down, a longer period of surveillance (ie, 3–5 years) is required to verify this early finding.

The study sought to maximize responses by AAAAI and ACAAI members by maintaining the anonymity of the respondents, providing multiple platforms for physicians to respond to the brief survey (ie, facsimiles, direct e-mails, and completion of a Web-based survey), and contacting nonresponders on at least 3 occasions using either direct e-mail or telephone calls. In the first year of the study, 806 physicians representing single-member and multimember physician practices completed the survey and reported reaction experiences among more than 1,900 SCIT prescribers, representing approximately 49% of known SCIT prescribers. These data represent a broader sample of practitioners than was captured in the most recent retrospective survey of SCIT FRs and NFRs (from 1990–2001) wherein 646 physicians reported their individual experiences and not those of their practice associates.

In addition to life-threatening SCIT reactions, for the first time, to our knowledge, this study sought to collect data to define annual incidence rates of allergic SCIT SRs of lesser severity. To achieve this, we established a 3-grade classification system of severity, including mild (grade 1), defined as cutaneous or upper respiratory symptoms; moderate (grade 2) or asthmatic responses with or without urticaria, upper respiratory symptoms, or abdominal symptoms; and severe anaphylaxis (grade 3), defined by severe airway compromise (severe bronchospasm or upper airway obstruction) or hypotension. The grade 3 category was intended to capture severe anaphylactic, life-threatening SCIT SRs. We used a simplified 3-grade system for classifying SRs that was intended to be user friendly and encourage participation. Although not all reactions may fit precisely into any one of these categories, respondents did not express broad concerns about this classification system.15 A more detailed grading system for allergic SRs to SCIT injections has been developed by members of the World Allergy Organization and is likely to be used in this and other SCIT surveillance questionnaires.16

The first year’s data established that injection-related nonfatal SRs are not uncommon (0.1% of injection visits) and occurred in 82% of practices. The overall SR rate of 0.1% of injection visits is consistent with frequencies of 0.06% to 0.23% SRs per number of injections reported in other longterm SCIT safety studies.17–20 Most SRs (74%) were of mild severity (grade 1). Moderate (grade 2) reactions were less common, representing 23% of all reported SRs, but occurred in most clinical practices. Severe anaphylactic (grade 3) reactions, although responsible for only 3% of SRs, were reported to have occurred in 18% of practices during the first year of this survey. This translated into 1 life-threatening SR in every 300,000 injection visits, which is 3-fold more frequent than what was reported in the most recent AAAAI survey of SCIT NFRs.6 The higher severe reaction rate identified in the present study may be attributed to a more aggressive approach to soliciting participation of all potential respondents via multiple contact attempts and by ensuring the confidentiality of the respondents. In addition, the incidence data in this study may be more reflective of practicing allergists compared with the last NFR 12-year retrospective survey, 6 which likely had selection and recall bias.

We also observed that more than 70% of SRs of all severity grades occurred in clinical practices reporting at least the median of 5,217 injection visits per year. Although we considered other explanations, further analysis demonstrated that the proportions of all 3 grades of reactions were not significantly different in clinics reporting at least 5,217 injection encounters and clinics with fewer than 5,217 injection encounters. This finding suggests that practices administering more injections have a greater probability of experiencing mild, moderate, and severe SRs. The increased incidence of severe reactions in practices giving more injections is proportionate to the increase for other types of reactions. We are, nonetheless, curious to know whether differences exist in risk management procedures aimed at preventing SCIT reactions in clinics reporting the most severe (grade 3) SRs. To address this question, a case-control study is currently under way comparing standard procedures related to SCIT administration used in clinics reporting grade 3 SRs compared with those reporting only grade 1 (mild) SRs. Examples of SCIT-related procedures being assessed include allergenic potency of treatment extracts, dose adjustment during the pollen season, and pre-injection screening for changes in asthma control.

In conclusion, we demonstrated the feasibility of conducting annual surveillance of FRs associated with SCIT injections in physician members of 2 medical subspecialty societies (the ACAAI and the AAAAI). No new FR events related to SCIT or skin testing have been identified during the first 12 months of this surveillance study. Nonfatal SRs are a common occurrence in allergy clinics that administer SCIT injections, but most are mild (ie, grade 1). In the future, this surveillance study will continue to annually track FRs, and the scope of the survey will be expanded to assess the annual incidence of late reactions, administration and timing of epinephrine use for mild SRs, and risk factors for serious anaphylactic (grade 3) reactions.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Funded jointly by the ACAAI and the AAAAI.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Grant provided by ACAAI and AAAAI to Bernstein Clinical Center staff for conduct of this study and to Gary M. Liss, MD for data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walker SM, Pajno GB, Lima MT, Wilson DR, Durham SR. Grass pollen immunotherapy for seasonal rhinitis and asthma: a randomized, controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramson MJ, Puy RM, Weiner JM. Allergen immunotherapy for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD001186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD001936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golden DB. Insect sting allergy and venom immunotherapy: a model and a mystery. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:439–447; quiz 48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein DI, Wanner M, Borish L, Liss GM. Twelve-year survey of fatal reactions to allergen injections and skin testing: 1990–2001. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin HS, Liss GM, Bernstein DI. Evaluation of near-fatal reactions to allergen immunotherapy injections. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117: 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox LS. How safe are the biologicals in treating asthma and rhinitis? Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2009;5:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox L. Allergen immunotherapy and asthma: efficacy, safety, and other considerations. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2008;29:580–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockey RF, Benedict LM, Turkeltaub PC, Bukantz SC. Fatalities from immunotherapy (IT) and skin testing (ST). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79:660–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid MJ, Lockey RF, Turkeltaub PC, Platts-Mills TA. Survey of fatalities from skin testing and immunotherapy 1985–1989. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CSM Update: desensitising vaccines. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;293:948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90(suppl 1):1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter second update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(suppl):S25–S85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Logistic Procedure, SAS for Windows, Version 9.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SG. Clinical features and severity grading of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cox L, Larenas-Linnemann D, Lockey RF, Passalacqua G. Speaking the same language: the World Allergy Organization Subcutaneous Immunotherapy Systemic Reaction Grading System. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:569–74, 74 e1–74 e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragusa VF, Massolo A. Non-fatal systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy: a 20-year experience comparison of two 10-year periods. Allerg Immunol (Paris). 2004;36:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gastaminza G, Algorta J, Audicana M, Etxenagusia M, Fernandez E, Munoz D. Systemic reactions to immunotherapy: influence of composition and manufacturer. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:470–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ragusa FV, Passalacqua G, Gambardella R, et al. Nonfatal systemic reactions to subcutaneous immunotherapy: a 10-year experience. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1997;7:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nettis E, Giordano D, Pannofino A, Ferrannini A, Tursi A. Safety of inhalant allergen immunotherapy with mass units-standardized extracts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32:1745–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]