ABSTRACT

Background

Flavonoid-rich foods have antiinflammatory, antiatherogenic, and antithrombotic properties that may contribute to a lower risk of ischemic stroke.

Objectives

We aimed to investigate the relationship between habitual flavonoid consumption and incidence of ischemic stroke in participants from the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study.

Design

In this prospective cohort study, 55,169 Danish residents without a prior ischemic stroke [median (IQR) age at enrolment of 56 y (52–60)], were followed for 21 y (20–22). We used Phenol-Explorer to estimate flavonoid intake from food frequency questionnaires obtained at study entry. Incident cases of ischemic stroke were identified from Danish nationwide registries and restricted cubic splines in Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate relationships with flavonoid intake.

Results

During follow-up, 4237 individuals experienced an ischemic stroke. Compared with participants in Q1 and after multivariable adjustment for demographics and lifestyle factors, those in Q5—for intake of total flavonoids, flavonols, and flavanol oligo + polymers—had a 12% [HR (95% CI): 0.88 (0.81, 0.96)], 10% [0.90 (0.82, 0.98)], and 18% [0.82 (0.75, 0.89)] lower risk of ischemic stroke incidence, respectively. Multivariable (demographic and lifestyle) adjusted associations for anthocyanins and flavones with risk of ischemic stroke were not linear, with moderate but not higher intakes associated with lower risk [anthocyanins Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.85 (0.79, 0.93); flavones: 0.90 (0.84, 0.97)]. Following additional adjustment for dietary confounders, similar point estimates were observed; however, significance was only retained for anthocyanins and flavanol oligo + polymers [anthocyanins Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.86 (0.79, 0.94); flavanol oligo + polymers Q5 vs. Q1 0.86 (0.78, 0.94)].

Conclusions

These findings suggest that moderate habitual consumption of healthy flavonoid-rich foods is associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke and further investigation is therefore warranted.

Keywords: nutrition, flavonoids, ischemic stroke, epidemiology, prospective cohort

See corresponding editorial on page 9 and article on page 203.

Introduction

Globally, stroke is a major cause of disability and mortality whose socioeconomic burden continues to rise with the increasing aging population (1). Total stroke, including both ischemic and hemorrhagic, is the second leading cause of death worldwide (2). Approximately 80% of all stroke cases, including fatal and nonfatal, are ischemic, although this varies by population (2). Vessel occlusion, occurring in ischemic stroke, is mostly a consequence of atherosclerosis and cardioembolisms, while hemorrhagic stroke, due to vessel rupture, is caused by different underlying pathogenic mechanisms typically involving hypertension and cerebral amyloid deposition (3–5). Flavonoids, present in foods such as tea, cocoa, nuts, fruits, and vegetables, have shown antiinflammatory, antiatherogenic, and antithrombotic properties and are suggested to play a role in protecting against ischemic stroke (6). We have previously shown that higher intakes of total flavonoids are associated with lower atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease hospitalizations, including lower ischemic stroke hospitalizations (7). However, further to this, only a limited number of other studies have investigated associations between intakes of flavonoids and ischemic stroke risk (8–11). Generally, these studies provide support that higher intakes of the flavonol, flavanone, and anthocyanin subclasses are associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, although results have been mixed (8–11). We have also previously observed that subpopulations prone to atherosclerosis, such as smokers and high alcohol consumers, might stand to benefit the most from higher flavonoid intakes (7,12); whether these results are consistent with outcomes for ischemic stroke requires investigation. The present study was therefore performed to 1) investigate the association between intakes of total flavonoids, flavonoid subclasses, and major flavonoid compounds with ischemic stroke incidence, and 2) identify populations that may benefit the most from higher flavonoid intakes.

Subjects and Methods

Study design

The Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study is a prospective cohort investigation of nutrition, cancer, and other chronic diseases, described in detail previously (13). The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (Ref no 2012–58–0004 I-Suite nr: 6357, VD-2018–117) and all participants provided informed consent. Requests to access the dataset may be sent to the Diet, Cancer and Health Steering Committee at the Danish Cancer Society. Briefly, between 1993 and 1997, 160,725 men and women, aged 50–64 y, who lived in the Copenhagen and Aarhus areas of Denmark, were invited to participate. Invitation was accepted by 57,053 people and the participants attended study centers for baseline assessment. Participants completed a self-administered, interviewer-checked questionnaire on sociodemographic factors and health behavior, while anthropometric measures and blood samples were obtained by professional staff. Dietary intake was assessed by a 192-item FFQ. Participants were then followed prospectively using Danish nationwide registries to identity and record follow-up information. Key registries included the Civil Registration System, which provides information on vital status and emigration; the Integrated Database for Labor Market Research, which contains annual income data; the Danish Registry of Causes of Death, which provides information on mortality; and the Danish National Patient Register (DNPR), which has recorded nearly all (∼99.4%) hospital admissions in Denmark since 1978. The DNPR further includes diagnosis information, classified until 1993 according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 8th Revision (ICD-8) and thereafter, according to the 10th Revision (ICD-10) (14). A total of 56,267 participants completed a FFQ with plausible energy intakes (500 to 5000 kcal/d) and were without a cancer diagnosis prior to enrolment. After excluding participants with a history of ischemic stroke at baseline (n = 887) and missing or extreme covariate outliers (n = 211), 55,169 participants remained for analysis. The study flow diagram is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Assessment of diet and flavonoid intake

Calculations of nutrient and flavonoid intake have been described previously (7, 13, 15). Briefly, data on the flavonoid content of foods were obtained from Phenol-Explorer (without hydrolysis of glycosides or esters) and the effect of food processing was taken into consideration using retention factors (16). Intakes of individual flavonoid compounds were estimated using the flavonoid content reported in Phenol-Explorer for each food and beverage item in the FFQ. Based on chemical structure, all individual flavonoid compounds were summed into subclasses including: flavonols, flavanol monomers, flavanol oligo + polymers (including theaflavins), flavanones, flavones, anthocyanins, isoflavones, dihydrochalcones, dihydroflavonols, and chalcones. Total flavonoid intake was calculated as the sum of all individual flavonoid compounds from all food sources. Following these calculations, exposures were intakes of total flavonoids, flavonoid subclasses, and individual flavonoid compounds with mean intakes of >5mg/d. In our prior work, we report a supplementary table showing the individual flavonoid compounds included in each subclass and total flavonoid intake (15).

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was death from, or first-time hospitalization for, ischemic stroke. Stroke hospitalizations were identified through primary or secondary diagnosis codes for ischemic stroke (ICD-10: I63 and I64) in the DNPR. The ICD codes for stroke hospitalization have a positive predictive value between 80.5% and 85% in the DNPR (17, 18). Stroke-related mortality was defined as an ICD-10 diagnosis registered as a cause of death related to ischemic stroke (ICD-10: I63 and I64).

Validated case analysis

To verify the registry-based outcomes, we re-examined associations using only medically reviewed and validated cases of first-time ischemic stroke (ICD-10: I63), with follow-up between March 1994 and November 2009. The methods for validating these cases have been published previously (17).

Covariates

Data on sex, age, education, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, daily activity, anthropometry, cholesterol, medication use, and diet were obtained from the baseline assessment. As an indicator of socioeconomic status, each participant's average annual income over 5 y (defined as household income after taxation and interest, for the value of the Danish currency in 2015) was used. For hypertension and diabetes mellitus, self-reported data were used due to the underreporting of these diagnoses in the DNPR (19). Self-reported myocardial infarction at baseline was combined with ICD codes (Supplementary Table 1) of ischemic heart disease dated prior to participant enrolment. ICD codes dated prior to participant enrolment were used to identify baseline comorbidities of peripheral artery disease, hemorrhagic stroke, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and atrial fibrillation (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

Time-to-event was defined as the time from date of enrolment to the date of an ischemic stroke event, death, emigration (loss to follow-up), or end of follow-up (August 2017), whichever came first. Nelson-Aalen plots of cumulative incidence for stroke with a competing risk of death were computed. In our primary analyses, restricted cubic splines in Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate nonlinear relationships between flavonoid intakes and ischemic stroke outcomes. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested by visually inspecting log–log plots of the survival function versus time, with no violation found. All HRs and 95% CIs were obtained from the model with the exposure fitted as a continuous variable; HR estimates are reported for the median intake in each quintile with the first quintile median as the reference point. For these analyses, all deaths were censored rather than treated as a competing risk (20). Three models of adjustment were used: 1) minimally adjusted: age (y) and sex (male/female); 2) multivariable-adjusted: age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), smoking status (current/former/never), physical activity (total daily metabolic equivalent), pure alcohol intake (g/d), education (≤7/8–10/≥11 y), and social economic status (income); 3) multivariable-adjusted including potential dietary confounders; covariates in Model 2 plus intakes (g/d) of fish, red meat, processed meat, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, and energy (kJ/d). Covariates were chosen a priori to the best of our knowledge of potential confounders of flavonoid intake and stroke. We also conducted exploratory analysis to test the robustness of our results. In addition to covariates in Models 2 and 3 we added separately into the models, a history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease, which may act as confounders and/or intermediates on the causal pathway linking flavonoid intake with ischemic stroke risk. In secondary analyses, we investigated whether associations differed in the presence of ischemic stroke risk factors, by stratifying by known risk factors for stroke (21). We excluded all participants with an alcohol intake of zero (n = 1261) and a BMI < 18.5 (n = 440) when stratifying by alcohol intake and BMI, respectively, due to potential underlying pathologies or habits that may increase cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. When stratifying by smoking status (never/ever), alcohol intake, and BMI, the corresponding continuous variables (smoking pack-years, alcohol intake, and BMI, respectively) were included in the model where appropriate to account for residual confounding. We tested for interactions using a chi-squared test comparing nested models. Standard logistic regression models were used to obtain the 20-y absolute risk estimates of incident ischemic stroke. Unless indicated by the stratification variable, these estimates are for the “average” cohort participant at baseline, i.e., a nonsmoking participant, aged 56 y, with a BMI of 25.5 kg/m2, a total daily metabolic equivalent score of 56, with a mean household income of 394,701–570,930 DKK/y, and an alcohol intake of 13 g/d, presented separately for males and females. All analyses were undertaken using Stata/IC 14.2 (StataCorp LLC) and R statistics (R Core Team, 2019) (22). Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05 (2-tailed) for all tests.

Results

During a median (IQR) follow-up of 21 y (20–22), 4237 incident cases (both fatal and nonfatal) of ischemic stroke occurred. A total of 11,808 participants died without having an ischemic stroke. The cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke and death without a prior ischemic stroke is shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Participants had a median (IQR) age at enrolment of 56 y (52–60) and a total flavonoid intake of 496 mg/d (287–805) (Table 1). Compared with participants with the lowest flavonoid intakes, those with the highest intakes were more likely to be female, have a lower BMI, be more physically active, have a higher education and income, and were less likely to have ever smoked; they also tended to eat more fish, fiber, fruits, and vegetables, and eat less red and processed meat (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population1

| Total flavonoid intake quintiles | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population n = 55,169 | Q1 n = 11,034 | Q2 n = 11,034 | Q3 n = 11,033 | Q4 n = 11,034 | Q5 n = 11,034 | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Total flavonoid intake (mg/d) | 496 [287–805] | 174 [127–213] | 321 [287–357] | 496 [443–549] | 727 [660–805] | 1201 [1025–1435] |

| Sex (male) | 26,141 (47.4) | 6339 (57.4) | 5641 (51.1) | 5236 (47.5) | 4892 (44.3) | 4033 (36.6) |

| Age (y) | 56 [52–60] | 56 [52–60] | 56 [52–60] | 56 [52–60] | 56 [52–60] | 55 [52–59] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5 [23.3–28.2] | 26.1 [23.8–28.8] | 25.9 [23.6–28.5] | 25.6 [23.3–28.2] | 25.3 [23.2–27.9] | 24.9 [22.7–27.4] |

| MET score | 56.5 [37.0–84.8] | 51.0 [32.3–78.0] | 55.5 [36.3–84.0] | 57.5 [38.5–85.0] | 58.5 [38.5–87.0] | 60.0 [40.0–88.5] |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never | 19,504 (35.4) | 2732 (24.8) | 3711 (33.6) | 3956 (35.9) | 4411 (40.0) | 4694 (42.5) |

| Former | 15,848 (28.7) | 2636 (23.9) | 2983 (27.0) | 3204 (29.0) | 3533 (32.0) | 3492 (31.6) |

| Current | 19,817 (35.9) | 5666 (51.4) | 4340 (39.3) | 3873 (35.1) | 3090 (28.0) | 2848 (25.8) |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤7 y | 18,082 (32.8) | 5034 (45.6) | 4187 (37.9) | 3515 (31.9) | 2966 (26.9) | 2380 (21.6) |

| 8–10 y | 25,454 (46.1) | 4817 (43.7) | 5193 (47.1) | 5289 (47.9) | 5225 (47.4) | 4930 (44.7) |

| ≥11 y | 11,609 (21.0) | 1177 (10.7) | 1651 (15.0) | 2225 (20.2) | 2838 (25.7) | 3718 (33.7) |

| Mean household income2 | ||||||

| ≤394,700 DKK/y | 13,583 (24.6) | 3257 (29.5) | 2692 (24.4) | 2644 (24.0) | 2516 (22.8) | 2474 (22.4) |

| 394,701–570,930 DKK/y | 13,768 (25.0) | 3200 (29.0) | 2956 (26.8) | 2673 (24.2) | 2554 (23.1) | 2385 (21.6) |

| 570,931–758,297 DKK/y | 13,870 (25.1) | 2901 (26.3) | 2988 (27.1) | 2857 (25.9) | 2591 (23.5) | 2533 (23.0) |

| >758,297 DKK/y | 13,948 (25.3) | 1676 (15.2) | 2398 (21.7) | 2859 (25.9) | 3373 (30.6) | 3642 (33.0) |

| Hypertensive | 8772 (15.9) | 1734 (15.7) | 1792 (16.2) | 1781 (16.1) | 1757 (15.9) | 1708 (15.5) |

| Hypercholesterolemic | 3988 (7.2) | 856 (7.8) | 793 (7.2) | 810 (7.3) | 829 (7.5) | 700 (6.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1109 (2.0) | 266 (2.4) | 207 (1.9) | 231 (2.1) | 209 (1.9) | 196 (1.8) |

| Heart failure | 194 (0.4) | 44 (0.4) | 51 (0.5) | 33 (0.3) | 37 (0.3) | 29 (0.3) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2043 (3.7) | 532 (4.8) | 405 (3.7) | 410 (3.7) | 365 (3.3) | 331 (3.0) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 354 (0.6) | 122 (1.1) | 84 (0.8) | 58 (0.5) | 41 (0.4) | 49 (0.4) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 780 (1.4) | 181 (1.6) | 152 (1.4) | 163 (1.5) | 151 (1.4) | 133 (1.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 256 (0.5) | 48 (0.4) | 56 (0.5) | 51 (0.5) | 45 (0.4) | 56 (0.5) |

| COPD | 833 (1.5) | 215 (1.9) | 182 (1.6) | 152 (1.4) | 153 (1.4) | 131 (1.2) |

| CKD | 194 (0.4) | 43 (0.4) | 32 (0.3) | 41 (0.4) | 41 (0.4) | 37 (0.3) |

| Medication use | ||||||

| Insulin treated | 364 (0.7) | 77 (0.7) | 63 (0.6) | 79 (0.7) | 79 (0.7) | 66 (0.6) |

| Antihypertensive | 6592 (11.9) | 1294 (11.7) | 1369 (12.4) | 1339 (12.1) | 1310 (11.9) | 1280 (11.6) |

| Statin | 972 (1.8) | 229 (2.1) | 196 (1.8) | 199 (1.8) | 198 (1.8) | 150 (1.4) |

| HRT | ||||||

| Never | 15,769 (28.6) | 2587 (23.4) | 3002 (27.2) | 3224 (29.2) | 3230 (29.3) | 3726 (33.8) |

| Current | 8743 (15.8) | 1288 (11.7) | 1552 (14.1) | 1684 (15.3) | 1981 (18.0) | 2238 (20.3) |

| Former | 4484 (8.1) | 811 (7.4) | 835 (7.6) | 882 (8.0) | 925 (8.4) | 1031 (9.3) |

| NSAID | 17,766 (32.4) | 3439 (31.4) | 3454 (31.5) | 3572 (32.6) | 3558 (32.4) | 3743 (34.1) |

| Aspirin | 6873 (12.5) | 1336 (12.1) | 1325 (12.0) | 1397 (12.7) | 1348 (12.2) | 1467 (13.3) |

| Dietary characteristics | ||||||

| Energy (kj) | 9501 [7857–11,370] | 8615 [7032–10,396] | 9262 [7715–11,009] | 9750 [8133–11,585] | 9935 [8319–11,824] | 9931 [8260–11,887] |

| Total fish intake (g/d) | 38 [25–55] | 33 [22–49] | 38 [25–54] | 39 [27–57] | 41 [28–59] | 40 [27–57] |

| Red meat intake (g/d) | 78 [56–107] | 80 [58–108] | 81 [59–110] | 80 [58–110] | 78 [57–107] | 72 [52–99] |

| Processed meat intake (g/d) | 25 [14–40] | 28 [17–45] | 26 [15–42] | 25 [14–40] | 23 [14–38] | 20 [11–34] |

| Dietary fiber intake (g/d) | 20 [16–25] | 17 [13–20] | 19 [16–23] | 21 [17–25] | 22 [18–27] | 23 [19–29] |

| Saturated FA (g/d) | 31 [24–39] | 29 [23–37] | 31 [24–39] | 32 [24–40] | 32 [25–41] | 32 [24–41] |

| Polyunsaturated FA (g/d) | 13 [10–17] | 12 [9–16] | 13 [10–17] | 14 [10–18] | 14 [11–18] | 14 [10–18] |

| Monounsaturated FA (g/d) | 27 [21–35] | 26 [20–34] | 27 [21–35] | 28 [22–35] | 28 [22–35] | 27 [21–34] |

| Fruit intake (g/d) | 172 [95–281] | 87 [44–141] | 161 [98–238] | 194 [114–301] | 224 [139–360] | 240 [141–389] |

| Vegetable intake (g/d) | 162 [105–231] | 114 [71–170] | 150 [100–212] | 168 [113–235] | 185 [127–253] | 196 [135–272] |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 13 [6–31] | 11 [3–23] | 13 [6–25] | 15 [6–34] | 14 [7–32] | 13 [6–32] |

Data expressed as median [IQR] or n (%), unless otherwise stated. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DKK, Danish krone; FA, fatty acids; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; MET, metabolic equivalent; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

The categories of household income in United States dollar (USD) equivalents are approximately ≤61,985/y; 61,986–89,661/y; 89,662–119,086/y; >119,087/y.

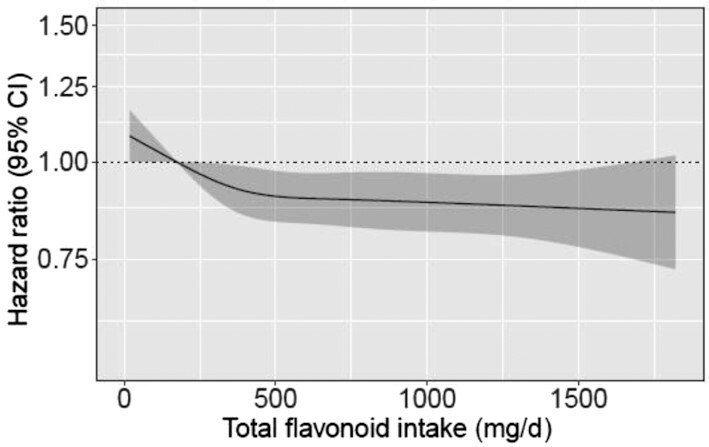

Associations between total habitual flavonoid intake and ischemic stroke incidence

Total flavonoid intake was associated with lower ischemic stroke incidence after multivariable adjustment for demographics and lifestyle factors (Model 2, Table 2). Restricted cubic splines showed a nonlinear inverse association; the association plateaued at intakes of ∼500 mg/d (Figure 1, Table 2). Compared with those with the lowest total flavonoid intakes (Q1), participants with the highest intakes (Q5) had a 12% lower risk of ischemic stroke [HR: 0.88 (95% CI: 0.81, 0.96)] after multivariable adjustment. After further adjustment for dietary confounders, the association was no longer significant (Model 3, Table 2). Using only validated first-time cases, 977 participants were hospitalized for an ischemic stroke. Compared with participants in Q1, those in Q5 had a 17% lower risk of ischemic stroke [Model 2 HR: 0.83 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.99); Supplementary Figure 3]. In exploratory analysis, the addition of intermediate and/or confounding conditions to Models 2 and 3, including history of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease, did not materially change their results (Models 4 and 5, Supplementary Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Hazard ratios of first-time ischemic stroke by quintiles of flavonoid intake1

| Flavonoid intake quintiles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (n = 11,034) | Q2 (n = 11,034) | Q3 (n = 11,033) | Q4 (n = 11,034) | Q5 (n = 11,034) | |

| Total flavonoids | |||||

| No. events | 1020 | 873 | 846 | 779 | 719 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 174 (6–252) | 321 (252–395) | 496 (395–602) | 727 (602–910) | 1201 (910–3552) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.86 (0.82, 0.92) | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.81) | 0.72 (0.66, 0.78) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) | 0.90 (0.84, 0.97) | 0.90 (0.83, 0.97) | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.92 (0.85, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.85, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) |

| Flavonols | |||||

| No. events | 1016 | 892 | 841 | 792 | 696 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 15 (0–21) | 26 (21–32) | 39 (32–50) | 66 (50–83) | 116 (83–251) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | 0.81 (0.76, 0.88) | 0.75 (0.70, 0.81) | 0.73 (0.67, 0.79) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.86, 1.00) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.99) | 0.90 (0.82, 0.98) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.86, 1.01) | 0.92 (0.85, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.84, 1.02) |

| Flavanol monomers | |||||

| No. events | 1024 | 844 | 883 | 781 | 705 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 14 (0–21) | 30 (21–46) | 67 (46–115) | 261 (115–282) | 473 (282–916) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.94 (0.90, 0.97) | 0.85 (0.78, 0.92) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.83) | 0.75 (0.69, 0.82) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.04) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.06) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) |

| Flavanol oligo + polymers | |||||

| No. events | 1010 | 944 | 798 | 768 | 717 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 92 (0–136) | 179 (136–217) | 256 (217–303) | 360 (303–434) | 537 (434–2254) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.84 (0.79, 0.90) | 0.76 (0.71, 0.82) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.77) | 0.68 (0.63, 0.74) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.93 (0.87, 0.99) | 0.88 (0.82, 0.95) | 0.84 (0.78, 0.91) | 0.82 (0.75, 0.89) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) | 0.86 (0.78, 0.94) |

| Anthocyanins | |||||

| No. events | 996 | 761 | 783 | 841 | 856 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 5 (0–10) | 13 (10–17) | 20 (17–24) | 36 (24–53) | 70 (53–397) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.81 (0.76, 0.86) | 0.74 (0.69, 0.81) | 0.78 (0.72, 0.84) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.89 (0.84, 0.95) | 0.85 (0.79, 0.93) | 0.87 (0.80, 0.94) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.90 (0.85, 0.96) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.94) | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) |

| Flavanones | |||||

| No. events | 917 | 811 | 859 | 782 | 868 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 3 (0–6) | 9 (6–13) | 18 (13–26) | 32 (26–49) | 70 (49–564) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.94 (0.89, 0.99) | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97) | 0.89 (0.83, 0.96) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.01) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.98 (0.93, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.10) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.99 (0.93, 1.04) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) |

| Flavones | |||||

| No. events | 919 | 855 | 787 | 811 | 865 |

| Intake (mg/d)* | 2 (0–3) | 4 (3–4) | 5 (4–6) | 7 (6–9) | 11 (9–51) |

| HR (95% CI) | |||||

| Model 1 | ref. | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) | 0.81 (0.75, 0.87) | 0.81 (0.76, 0.87) | 0.87 (0.80, 0.94) |

| Model 2 | ref. | 0.93 (0.87, 0.98) | 0.90 (0.84, 0.97) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) |

| Model 3 | ref. | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.93 (0.86, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.93, 1.12) |

Hazard ratios (95% CI) for first-time ischemic stroke during 21 y of follow-up, obtained from restricted cubic splines in Cox proportional hazards models. Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, education, and social economic status (income); Model 3 adjusted for all covariates in Model 2 plus intakes of fish, red meat, processed meat, polyunsaturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, saturated fatty acids, and energy.

*Median; range in parentheses (all such values). Intake quintiles are mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 1.

Cubic spline curves describing the association between total flavonoid intake and total (first-time) ischemic stroke events (n = 4237) among participants of the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health cohort. Hazard ratios are based on Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, education, and social economic status (income) and are comparing the specific level of flavonoid intake (horizontal axis) to the median intake for participants in the lowest intake quintile (174 mg/d).

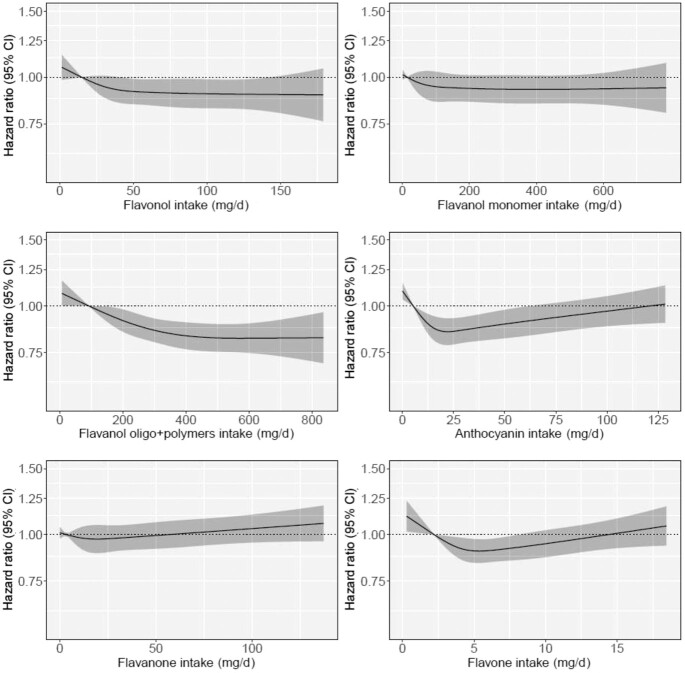

Associations between habitual flavonoid subclass intakes and ischemic stroke incidence

Intakes of flavonols and flavanol oligo + polymers were inversely associated with incidence of ischemic stroke (Figure 2) with the lowest relative risks observed for those in Q5 [flavonols Q5 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.90 (0.82, 0.98); flavanol oligo + polymers Q5 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.82 (0.75, 0.89); Model 2; Table 2]. The association remained statistically significant for intakes of flavanol oligo + polymer, but not flavonols, following additional adjustment for dietary confounders (Model 3; Table 2). Associations for anthocyanins and flavones were U-shaped (Figure 2); the lowest relative risks of ischemic stroke were observed for moderate consumers [anthocyanins Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.85 (0.79, 0.93); flavones Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.90 (0.84, 0.97); Model 2; Table 2]. The association remained statistically significant for intakes of anthocyanins, but not flavones, following additional adjustment for dietary confounders (Model 3; Table 2). Intakes of flavanones and flavanol monomers were not associated with ischemic stroke (Figure 2 and Table 2). In exploratory analysis, further adjustment for intermediate and/or confounding conditions did not materially change the results of Models 2 or 3 for all subclasses, except for flavones, where further adjustment attenuated the relationship in Model 2 (Models 4 and 5, Supplementary Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Hazard ratios based on cubic spline curves to describe the association between flavonoid subclass intakes (mg/d) and total (first-time) ischemic stroke events (n = 4237) among participants of the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health cohort. Hazard ratios are based on Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, education, and social economic status (income) and are comparing the specific level of flavonoid intake (horizontal axis) to the median intake for participants in the lowest intake quintile.

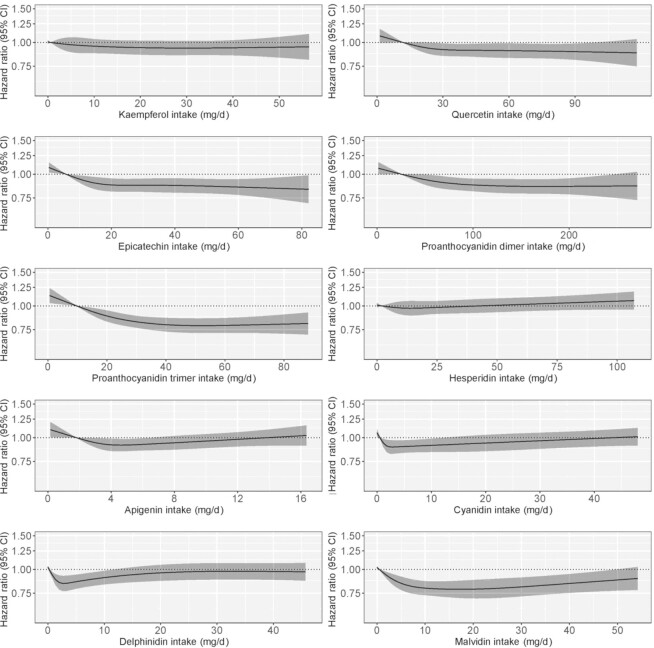

Associations between habitual major flavonoid compound intakes and ischemic stroke incidence

Of the flavonol compounds investigated, quercetin but not kaempferol, was nonlinearly associated with lower ischemic stroke risk; the inverse association plateaued at moderate intakes [quercetin Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.92 (0.85, 0.99); Model 2; Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3]. Following additional adjustment for dietary confounders, neither quercetin nor kaempferol were significantly associated with ischemic stroke risk (Model 3; Supplementary Table 3). Both flavanol oligomers examined, that is, proanthocyanidin dimers and proanthocyanidin trimers, were nonlinearly associated with lower ischemic stroke risk, as was the flavanol monomer epicatechin; the significant inverse association plateaued for all at moderate intakes [proanthocyanidin dimers Q2 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.94 (0.88, 0.99); proanthocyanidin trimers Q2 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.92 (0.87, 0.97); epicatechin Q2 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.92 (0.87, 0.98); Model 2; Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3] and was unchanged in Model 3. Concerning anthocyanin compounds, higher intakes of malvidin were associated with lower ischemic stroke risk in all models [malvidin Q2 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.93 (0.89, 0.97); Model 2]; however, associations for cyanidin and delphinidin were U-shaped; a lower risk of ischemic stroke was observed for moderate consumption [cyanidin Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.90 (0.84, 0.97); delphinidin Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.85 (0.78, 0.93) Model 2; Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3]. Following adjustment for dietary intake, significance was attenuated for cyanidin but not delphinidin (Model 3; Supplementary Table 3). The flavone apigenin was also associated with ischemic stroke in a U-shaped pattern [apigenin Q3 vs. Q1 HR (95% CI): 0.91 (0.85, 0.98); Model 2], although this was attenuated following adjustment for diet (Model 3; Supplementary Table 3). No association was observed for the flavanone hesperidin (Figure 3; Supplementary Table 3).

FIGURE 3.

Hazard ratios based on cubic spline curves to describe the association between major flavonoid compound intakes and total (first-time) ischemic stroke events (n = 4237) among participants of the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health cohort. Hazard ratios are based on Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for age, sex, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, education, and social economic status (income) and are comparing the specific level of flavonoid compound intake (horizontal axis) to the median intake for participants in the lowest intake quintile.

Associations between habitual total flavonoid intake and ischemic stroke incidence stratified by risk factors for stroke

The association between total flavonoid intake and ischemic stroke was present in all subgroups investigated (Pinteraction ≥ 0.05 for all); the shape of the associations appeared similar to that seen in the whole population except in those with a BMI of >30 kg/m2 for which the association appeared more U-shaped (Supplementary Figure 4). On the absolute scale, the difference in the estimated risk of an ischemic stroke [risk for a person with a high flavonoid intake (Q5) – risk for a person with a low flavonoid intake (Q1)] tended to be higher in smokers (1.22% males, 0.90% females) than nonsmokers (0.87% males, 0.63% females), obese participants (1.22% males, 0.88% females) than non-obese participants (1.19% males, 0.66% females), and higher alcohol consumers (0.92% males, 0.66% females) than low alcohol consumers (0.84% males, 0.60% females; Supplementary Tables 4–6). Moreover, on the absolute scale, the risk difference across all stratification variables (i.e., smoking status, alcohol intake, and BMI) was slightly higher in males than females.

Discussion

Overall, we found a moderate habitual intake of certain flavonoids are significantly associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke. In demographic and lifestyle-adjusted models, higher intakes of total flavonoids, flavanol oligo + polymers, and flavonols were significantly associated with lower ischemic stroke risk, whereas anthocyanins and flavones were associated in a U-pattern. Following additional adjustment for dietary confounders, similar point estimates were observed; however, significance was only retained for anthocyanins and flavanol oligo + polymers. For major flavonoid compounds, associations with ischemic stroke risk were also present in demographic and lifestyle-adjusted models (proanthocyanidin dimers, proanthocyanidin trimers, epicatechin, quercetin, apigenin, cyanidin, delphinidin, and malvidin); these tended to follow the same pattern as the subclass to which the compound belongs. With additional adjustment for dietary covariates, significance was limited to specific anthocyanin and flavanol oligo + polymer compounds (proanthocyanidin dimers, proanthocyanidin trimers, and malvidin) in addition to the flavanol monomer epicatechin. In our effort to identify population subgroups that may benefit the most from higher flavonoid intakes, we did not find clear evidence of effect modification by smoking status, BMI, or alcohol intake on the relative scale.

Prior studies reported conflicting evidence that higher intakes of flavonols and flavanones might be associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke, while for other flavonoid exposures (i.e., quercetin, flavones, and total flavonoid) no clear associations have been observed (8–11, 23). Our study did not find clear evidence for the involvement of flavanones, yet we did find some evidence suggesting a possible benefit of quercetin, flavonols, flavones, and total flavonoid intake on ischemic stroke risk, although these associations may be due, in part, to differences in dietary patterns. Prior studies also report conflicting null and beneficial results regarding anthocyanin intake and ischemic stroke risk; however, those investigating flavanol oligo + polymers have consistently observed no relationship (8–11). We found both anthocyanin and flavanol oligo + polymer intake, in addition to several of their compounds, are associated with lower ischemic stroke risk independent of established dietary and non-dietary CVD risk factors. In addition, we found evidence of an inverse association between epicatechin intake and ischemic stroke risk independent of diet and lifestyle; however, we did not observe a role of total monomer intake, which is in agreement with findings from another cohort (8).

The reasons for apparent inconsistencies in results between studies on flavonoid intake and ischemic stroke risk are not clear. Whether the differences in outcomes between studies is due to differences in the absolute intakes between cohorts, the inclusion or exclusion of flavonoid-rich foods in FFQs, differences in other cohort characteristics, chance findings, or combinations of such limitations is less certain (24). One hypothesis is that the associations observed may represent a signal of the flavonoids acting in concert with the co-occurring nutrient matrix within flavonoid-rich foods, rather than a benefit of the compounds per se (24, 25). If this is true, then differences in the patterns of the flavonoid food sources consumed may account for the different outcomes of the prospective cohort studies described. It may also explain the U-shaped associations observed for the anthocyanin and flavone subclasses; that is, significance in the highest exposure category might have been attenuated due to introduced confounding, as higher intakes of certain co-occurring components in flavonoid-bearing foods or mixed meals may exert detrimental actions (e.g., anthocyanin-rich juice may provide excess sugar intake or processed flours reported to contain higher flavones may be otherwise nutrient-poor). Interestingly, although the anthocyanin subclass was associated with ischemic stroke incidence in a U-shaped pattern, the anthocyanin compound malvidin was associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke across Q2 to Q5 in comparison with Q1. In this cohort, the primary dietary source of malvidin was red wine, pointing to a potential protective association between red wine consumption and ischemic stroke.

The pathology of ischemic stroke is complex. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of flavonoids and flavonoid-rich foods have shown that they exert several antiatherogenic actions including the capacity to beneficially modulate blood pressure, endothelial function, and arterial stiffness (24). At the same time, flavonoids have demonstrated antithrombotic and antiinflammatory properties (26, 27). Collectively, these actions may facilitate a lower risk of ischemic stroke. However, up to ∼25% of all ischemic strokes can be cryptogenic in nature, while up to ∼5% can be due to other rarer causes (e.g., infectious disease) (3, 4). If flavonoids are protective to some forms of ischemic stroke but not others, then differences in the causes of ischemic stroke comprising the outcome events between cohort studies or even between quantiles within cohorts could potentially lead to different findings. For example, a well-known risk factor for stroke, atrial fibrillation, was not associated with flavonoid intake (28). However, we found that peripheral vascular disease was highly associated with flavonoid intake (7, 12), which could indicate the primary mechanism of flavonoids in reducing ischemic stroke is to reduce overall atherogenesis. For these reasons, further investigation focusing on flavonoid intake and ischemic stroke subtypes would be of value.

In our study, on the relative scale, associations did not differ for subgroups at a higher risk of atherosclerosis. However, on the absolute scale, subpopulations with risk factors for atherosclerosis (including smokers, high alcohol consumers, males, and obese participants) had a modest, yet larger, absolute risk difference than their counterparts. In line with our prior research, this might indicate that subpopulations prone to atherosclerosis may benefit the most from higher flavonoid intakes, although further investigation is needed to support these preliminary enquiries (7, 12).

The limitations of the present study include possible measurement error relating to the use of self-report subjective measures such as diet, physical activity, etc. While the FFQ used ascertained the frequency of strawberry consumption, it did not capture intakes of other berries, a major food source of anthocyanins. The use of an observational design also restricts our ability to infer causality or to exclude the possibility of confounding by unmeasured or residual factors. Additionally, dietary data and covariate information were obtained at baseline and it is unclear how these might have changed over time. However, any misclassification error arising would have likely attenuated any observed associations. Despite this, the lower risk of ischemic stroke remained even after adjusting for other major indicators of a healthy lifestyle suggesting that higher intake of certain flavonoid-rich foods may be associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke. However, because the Danish population is more homogeneous than many other countries, the generalizability of our results is limited.

Conclusions

In conclusion, moderate habitual intakes of certain flavonoid subclasses and compounds appear to be associated with a lower risk of ischemic stroke. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm these observations as well as RCTs to disentangle the relative influence of flavonoid compounds on markers of stroke risk. Nonetheless, these findings provide support for the consumption of healthy flavonoid-rich foods and highlight the potential to improve population health in future health-promotion policies, practices, or programs targeting nutrition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—NPB and FD: designed research (project conception, development of overall research plan, and study oversight); AT and KO: conducted original study; AS: calculated the flavonoid intake from FFQ data; NPB, KM, and FD: analyzed data; BHP: wrote the paper; NPB: had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: critically reviewed the final draft of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

Sources of support: The Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study was funded by the Danish Cancer Society, Denmark. BHP is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Stipend Scholarship. NPB is funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship (Grant number APP1159914), Australia. JRL is funded by a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (ID: 102817). The salary of JMH is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Senior Research Fellowship, Australia (Grant number APP1116937).

Where authors are identified as personnel of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization, the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the International Agency for Research on Cancer/World Health Organization.

Supplemental Figures 1–4 and Supplemental Tables 1–6 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

BHP and FD contributed equally to this manuscript.

Abbreviations used: CVD, cardiovascular disease; DKK, Danish krone; DNPR, Danish National Patient Register; ICD, International Classification of Diseases.

Contributor Information

Benjamin H Parmenter, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Western Australia, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia.

Frederik Dalgaard, Department of Cardiology, Herlev & Gentofte University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Kevin Murray, School of Population and Global Health, University of Western Australia, Australia.

Aedin Cassidy, Institute for Global Food Security, Queen's University, Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Catherine P Bondonno, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia; Medical School, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

Joshua R Lewis, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia; Medical School, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia; Centre for Kidney Research, School of Public Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Kevin D Croft, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Western Australia, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia.

Cecilie Kyrø, The Danish Cancer Society Research Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Gunnar Gislason, Department of Cardiology, Herlev & Gentofte University Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark; The National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark; The Danish Heart Foundation, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Augustin Scalbert, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

Anne Tjønneland, The Danish Cancer Society Research Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark; Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Jonathan M Hodgson, School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia; Medical School, University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia.

Nicola P Bondonno, School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Western Australia, Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia; Institute for Global Food Security, Queen's University, Belfast, Northern Ireland; School of Medical and Health Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Perth, Australia.

Data Availability

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval by the Diet, Cancer and Health Steering Committee at the Danish Cancer Society.

References

- 1. Feigin VL, Norrving B, George MG, Foltz JL, Roth GA, Mensah GA. Prevention of stroke: a strategic global imperative. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:501–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donkor ES. Stroke in the 21st century: a snapshot of the burden, epidemiology, and quality of life. Stroke Res Treat. 2018;3238165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johns P. Clinical Neuroscience. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2014. Chapter 10, Stroke. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Norrving B. Common causes of ischemic strokeIn: Textbook of Stroke Medicine. Brainin M, Heiss WDeds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hankey GJ. Stroke. Lancet North Am Ed. 2017;389:641–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodriguez-Mateos A, Vauzour D, Krueger CG, Shanmuganayagam D, Reed J, Calani L, Mena P, Del Rio D, Crozier A. Bioavailability, bioactivity and impact on health of dietary flavonoids and related compounds: an update. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88:1803–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalgaard F, Bondonno NP, Murray K, Bondonno CP, Lewis JR, Croft KD, Kyrø C, Gislason G, Scalbert A, Cassidy Aet al. . Associations between habitual flavonoid intake and hospital admissions for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Planet Heal. 2019;3:e450–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cassidy A, Rimm EB, ÉJ O'R, Logroscino G, Kay C, Chiuve SE, Rexrode KM. Dietary flavonoids and risk of stroke in women. Stroke. 2012;43:946–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mursu J, Voutilainen S, Nurmi T, Tuomainen TP, Kurl S, Salonen JT. Flavonoid intake and the risk of ischaemic stroke and CVD mortality in middle-aged Finnish men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Br J Nutr. 2008;100:890–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goetz ME, Judd SE, Hartman TJ, McClellan W, Anderson A, Vaccarino V. Flavanone intake is inversely associated with risk of incident ischemic stroke in the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. J Nutr. 2016;146:2233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cassidy A, Bertoia M, Chiuve S, Flint A, Forman J, Rimm EB. Habitual intake of anthocyanins and flavanones and risk of cardiovascular disease in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:587–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bondonno NP, Murray K, Cassidy A, Bondonno CP, Lewis JR, Croft KD, Kyrø C, Gislason G, Torp-Pedersen C, Scalbert Aet al. . Higher habitual flavonoid intakes are associated with a lower risk of peripheral artery disease hospitalizations. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;113:187–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Boll K, Stripp C, Christensen J, Engholm G, Overvad K. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: a population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35:432–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bondonno NP, Dalgaard F, Kyrø C, Murray K, Bondonno CP, Lewis JR, Croft KD, Gislason G, Scalbert A, Cassidy Aet al. . Flavonoid intake is associated with lower mortality in the Danish Diet Cancer and Health Cohort. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neveu V, Perez-Jiménez J, Vos F, Crespy V, du Chaffaut L, Mennen L, Knox C, Eisner R, Cruz J, Wishart Det al. . Phenol-Explorer: an online comprehensive database on polyphenol contents in foods. Database. 2010;2010:bap024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lühdorf P, Overvad K, Schmidt EB, Johnsen SP, Bach FW. Predictive value of stroke discharge diagnoses in the Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2017;45:630–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krarup LH, Boysen G, Janjua H, Prescott E, Truelsen T. Validity of stroke diagnoses in a national register of patients. Neuroepidemiology. 2007;28:150–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Noordzij M, Leffondré K, Van Stralen KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW, Jager KJ. When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology?. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2670–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV. Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ Res. 2015;7:472–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. R Core Team.. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Knekt P, Isotupa S, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, Järvinen R, Häkkinen S, Aromaa A, Reunanen A. Quercetin intake and the incidence of cerebrovascular disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:415–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parmenter BH, Croft KD, Hodgson JM, Dalgaard F, Bondonno CP, Lewis JR, Cassidy A, Scalbert A, Bondonno NP. An overview and update on the epidemiology of flavonoid intake and cardiovascular disease risk. Food Funct. 2020;11:6777–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bondonno NP, Bondonno CP, Ward NC, Hodgson JM, Croft KD. The cardiovascular health benefits of apples: whole fruit vs. isolated compounds. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;69:243–56. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ostertag LM, O'Kennedy N, Kroon PA, Duthie GG, de Roos B. Impact of dietary polyphenols on human platelet function–a critical review of controlled dietary intervention studies. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2010;54:60–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quiñones M, Miguel M, Aleixandre A. Beneficial effects of polyphenols on cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;68:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bondonno N, Murray K, Bondonno CP, Lewis JR, Croft KD, Kyro C, Gislason G, Tjonneland A, Scalbert A, Cassidy Aet al. . Flavonoid intake and its association with atrial fibrillation. Clin Nutr. 2020;39:3821–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval by the Diet, Cancer and Health Steering Committee at the Danish Cancer Society.