Abstract

Background

Rapid blood culture diagnostics are of unclear benefit for patients with gram-negative bacilli (GNB) bloodstream infections (BSIs). We conducted a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comparing outcomes of patients with GNB BSIs who had blood culture testing with standard-of-care (SOC) culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) vs rapid organism identification (ID) and phenotypic AST using the Accelerate Pheno System (RAPID).

Methods

Patients with positive blood cultures with Gram stains showing GNB were randomized to SOC testing with antimicrobial stewardship (AS) review or RAPID with AS. The primary outcome was time to first antibiotic modification within 72 hours of randomization.

Results

Of 500 randomized patients, 448 were included (226 SOC, 222 RAPID). Mean (standard deviation) time to results was faster for RAPID than SOC for organism ID (2.7 [1.2] vs 11.7 [10.5] hours; P < .001) and AST (13.5 [56] vs 44.9 [12.1] hours; P < .001). Median (interquartile range [IQR]) time to first antibiotic modification was faster in the RAPID arm vs the SOC arm for overall antibiotics (8.6 [2.6–27.6] vs 14.9 [3.3–41.1] hours; P = .02) and gram-negative antibiotics (17.3 [4.9–72] vs 42.1 [10.1–72] hours; P < .001). Median (IQR) time to antibiotic escalation was faster in the RAPID arm vs the SOC arm for antimicrobial-resistant BSIs (18.4 [5.8–72] vs 61.7 [30.4–72] hours; P = .01). There were no differences between the arms in patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Rapid organism ID and phenotypic AST led to faster changes in antibiotic therapy for gram-negative BSIs.

Clinical Trials Registration

Keywords: blood cultures, antibiotic susceptibility testing, rapid diagnostic, bloodstream infection, gram negative

This randomized, controlled trial demonstrates that compared with conventional testing, a rapid phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility testing method implemented together with antibiotic stewardship can facilitate significantly faster antibiotic modifications during treatment of gram-negative bloodstream infections.

Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) cause between one-quarter and one-third of bloodstream infections (BSIs) worldwide [1–3]. Emergence and spread of resistance among many species of GNB, often to multiple drug classes, has led to a dearth of effective therapies. Ineffective therapy for BSIs caused by GNBs is associated with mortality rates in excess of 30% [4–10]. Due to concerns about the possible presence of antimicrobial resistance, use of broad-spectrum therapies has become routine for empiric treatment of BSIs caused by GNB. In turn, this practice may promote further selection of antimicrobial resistance, increased toxicity, and higher costs of care.

Rapid blood culture diagnostics can provide organism identification (ID) and phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of GNB within hours after a blood culture turns positive, in contrast to the 48–96 hours required for conventional testing. Such information should enable timely initiation of optimal antibiotic therapy, with potential for improved outcomes. However, rapid testing methods are costly. Their impact on antibiotic use and patient outcomes must be evaluated and strategies to integrate such testing into clinical practice determined [11].

Prior single-center, observational studies have demonstrated decreased time to appropriate antibiotics, lower mortality, shorter durations of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and reduced costs when rapid identification and AST methods are coupled with antimicrobial stewardship [12–14]. Limitations of these studies include that they were retrospective, subject to temporal trends, single-center, and uncontrolled. A previous single-center, randomized, controlled trial demonstrated that rapid polymerase chain reaction–based blood culture identification paired with antimicrobial stewardship (AS) was associated with more rapid antibiotic deescalation, shorter time to appropriate antibiotic therapy, and decreased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics [15]. However, the diagnostic test evaluated in that study had limited impact on management of patients with GNB BSIs because the test detected only a single GNB resistance determinant (blaKPC) and provided no phenotypic susceptibility information.

The Accelerate PhenoTest BC Kit, performed on the Accelerate Pheno System (Accelerate Diagnostics, Tucson, AZ), hereafter referred to as “RAPID,” is a US Food and Drug Administration–approved automated platform that performs rapid bacterial identification of 8 GNB species followed by phenotypic AST within approximately 7 hours directly from positive blood cultures [16, 17]. We compared time to first antibiotic modification, antibiotic use, and clinical outcomes of patients with GNB BSIs evaluated using RAPID vs standard-of-care culture (SOC) and AST methods in the setting of AS activities.

METHODS

Design and Oversight

We conducted a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial from October 2017 through October 2018 of patients with GNB BSIs who had blood culture testing with SOC culture and AST vs rapid organism ID and phenotypic AST using the Accelerate PhenoTM System (RAPID). Trial oversight and coordination was performed by the Duke Clinical Research Institute. The investigators remained unaware of the outcomes until database lock in March 2019. All authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and analyses and the fidelity of the trial to the protocol.

Participants

Patients at 2 US academic medical centers who had a positive blood culture with Gram stain showing GNB identified during local laboratory business hours were evaluated for eligibility. One laboratory was open 24/7 while the other was not (see Supplementary Appendix for details). Patients were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: identification of GNB outside of local laboratory rapid testing hours; positive blood culture for GNB within the prior 7 days (if known at the time of randomization); deceased or on comfort care at the time of randomization; GNB plus gram-positive organism, gram-negative cocci, and/or yeast detected on Gram stain; previous enrollment in this study; or no Minnesota research authorization (Rochester, Minnesota, site only). The study was approved by Duke University and site institutional review boards with a waiver of informed consent.

Procedures

Laboratory Testing

For all patients, the local SOC for identification and AST of GNB from positive blood cultures was performed, including standard subculture, species identification by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), and AST using broth microdilution or agar dilution. For patients randomized to the rapid testing arm, testing was also performed using the RAPID system, and results were reported in the electronic medical record without specifying the method used. Details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Antimicrobial Stewardship

All patients in both arms underwent prospective audit and feedback by institutional AS programs. In both arms, the AS physician or pharmacist was notified by page at the time of every positive Gram stain, organism ID, and AST, regardless of testing method. The AS provider reviewed the record and contacted the primary service by telephone if modifications to therapy were indicated. Scenario-based standardized AS recommendations were developed and disseminated to AS clinicians as detailed in the Supplementary Appendix. Timing and type of AS recommendations were at the discretion of the AS clinicians. Acceptance of AS recommendations was at the discretion of treating providers.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was median hours from randomization until first modification (either escalation or deescalation) of antibiotic therapy within 72 hours post randomization, abstracted from the medication administration record in the electronic medical record. For all patients, including those who died within 72 hours, the time of earliest antibiotic modification was used as the time to modification. Patients who did not have antibiotic modifications were assigned a time of 72 hours. No additional censoring was observed. Antibiotic escalation and deescalation are defined in the Supplementary Appendix.

Secondary outcome measures included in-hospital mortality within 30 days of randomization, length of stay in the hospital after randomization up to 30 days for patients alive at 30 days, ICU length of stay after randomization, time to antibiotic escalation and deescalation within 72 hours from randomization, hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile within 30 days, acquisition of new hospital-acquired infections and/or multidrug-resistant organisms within 30 days [18], and concordance of organism ID and AST using RAPID and SOC methods. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Randomization and Blinding

Patients were assigned to each arm in a 1:1 ratio using permuted blocks, stratified by site. Randomization was performed by laboratory technologists at the time the Gram stain detecting GNB was identified. AS providers were not blinded to group assignment. The primary service was unaware of group assignment at the time of randomization. Once blood culture results became available and/or AS interventions were made, treating providers may have been aware of group assignment due to faster reporting of ID and AST results using RAPID.

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed 2 study populations. The total population was used to evaluate rapid test performance and included patients who met eligibility criteria at the time of randomization, even if they were later found to meet exclusion criteria. A modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population included patients who met all eligibility criteria and no exclusion criteria. We estimated that randomization of 500 patients would yield at least 200 evaluable patients in each arm, and 80% power with a 2-sided α = 0.05 test, to detect a difference in the time to first modification of antibiotic therapy between the 2 arms of at least 9 hours, with a standard deviation (SD) of 32 hours. Participants were analyzed as randomized, even if the rapid test did not return a result.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome excluded antibiotic modifications performed within the first 1 and 2 hours of randomization, since these changes may be due to results of the blood culture Gram stain rather than the rapid testing. The primary outcome was evaluated in prespecified subgroup analyses of patients in the ICU or neutropenic (absolute neutrophil count <500 cells/µL) at randomization, patients in whom providers may not deescalate antibiotics based solely on blood culture results. Wilcoxon rank sum tests and t tests were used for analyses and generated with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Trial Population

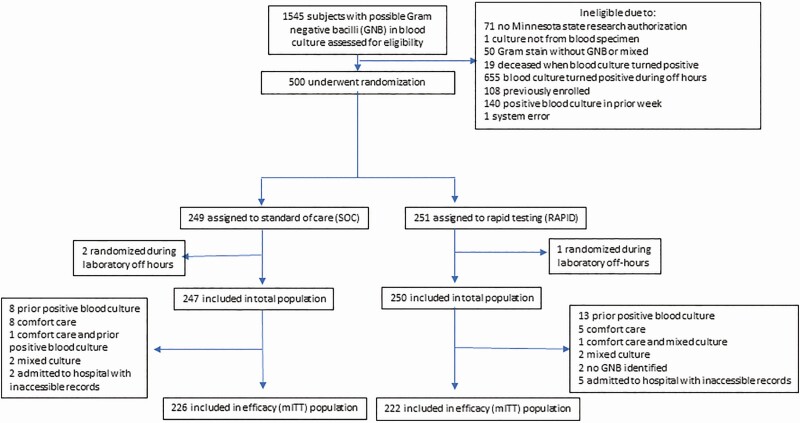

A total of 1545 patients were screened, 500 randomized, 497 included in the total population, and 448 included in the final mITT analysis (Figure 1). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and severity of illness were similar between the SOC and RAPID arms (Table 1). Fourteen (3%) patients were aged <18 years. Length of stay prior to randomization and the proportion in the ICU at randomization were slightly greater in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm.

Figure 1.

Participant screening and randomization. The total population was used to evaluate rapid test performance and included patients who met eligibility criteria at the time of randomization regardless if they were later found to meet exclusion criteria. The mITT population included patients who met all eligibility criteria and no exclusion criteria. Abbreviations: GNB, gram-negative bacilli; mITT, modified intention-to-treat; RAPID, organism identification and phenotypic antibiotic susceptibility testing using the Accelerate Pheno System.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Microbiologic Characteristics by Treatment Arm

| Characteristic | Standard of Care (N = 226) | RAPID (Accelerate Pheno System) (N = 222) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Study site | ||

| 1, no. (%) | 181 (80) | 181 (82) |

| 2, no. (%) | 45 (20) | 41 (18) |

| Male, no. (%) | 130 (58) | 122 (55) |

| Race or ethnic group | ||

| White, no. (%) | 185 (82) | 177 (80) |

| Black, no. (%) | 9 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Asian, no (%) | 8 (4) | 7 (3) |

| Hispanic, no. (%) | 13 (6) | 16 (7) |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 65.8 (18.3) | 62.2 (20.3) |

| Coexisting conditions | ||

| Charlson score, mean (SD) | 2.4 (2.2) | 2.3 (2.2) |

| Length of stay prior to randomization, mean (SD) | 3.3 (7.7) | 6.8 (25) |

| Diabetes mellitus, with or without end- organ damage | 62 (27) | 61 (27) |

| Myocardial infarction | 7 (3) | 6 (3) |

| Congestive heart failure | 32 (14) | 35 (16) |

| Dementia | 16 (7) | 8 (4) |

| Renal disease | 56 (25) | 57 (26) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13 (6) | 14 (6) |

| Solid tumor last 5 years | 45 (20) | 35 (16) |

| Leukemia or lymphoma | 35 (15) | 34 (15) |

| Liver disease | 13 (5.7) | 19 (8.6) |

| Clinical characteristics at randomization | ||

| Pitt bacteremia score, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.9) | 1.9 (1.6) |

| Admitted in intensive care unit, no. (%) | 64 (28) | 80 (36) |

| Mechanical ventilation, no. (%) | 43 (19) | 39 (18) |

| Neutropenic, no. (%) | 43 (19) | 30 (14) |

| Source of bacteremia, no. (%) | ||

| Urinary | 88 (39) | 71 (32) |

| Central venous catheter | 26 (12) | 24 (11) |

| Intra- abdominal | 57 (25) | 66 (30) |

| Skin/soft tissue | 13 (6) | 12 (5) |

| Lung | 11 (5) | 13 (6) |

| Temperature ≤36ºC or ≥ 39ºC, no. (%) |

38 (16.8) | 37 (16.7) |

| Hypotension,a no. (%) | 71 (31) | 81 (36) |

| Requiring vasopressor agents at time of randomization, no. (%) | 43 (19) | 46 (21) |

| Altered mental status,b no. (%) | 20 (9) | 18 (8) |

| Community-onset infectionc | 172 (76) | 165 (74) |

| Blood culture organisms,d,e no. (% of total) | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | 2 (1) | 1 (0) |

| Citrobacter species | 5 (2) | 3 (1) |

| Escherichia coli | 103 (44) | 98 (42) |

| Enterobacter speciesf | 17 (7) | 14 (6) |

| Klebsiella species | 47 (20) | 50 (21) |

| Proteus species | 7 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 24 (10) | 29 (12) |

| Serratia marcescens | 3 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Off-panel organisms | 23 (10) | 20 (9) |

| Antimicrobial resistance in blood culture isolates, no./total no. (%) | ||

| Third-generation nonsusceptible Enterobacteralesg | 32/182 (18) | 34/177 (19) |

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteralesg | 6/182 (3) | 4/177 (2) |

| Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosah | 2/24 (8) | 6/29 (21) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

aDefined as an acute hypotensive event with a drop in systolic blood pressure >30 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg, requirement for intravenous vasopressor agent, systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, or mean arterial pressure <70 mm Hg within 24 hours before or on the day of randomization.

bAs documented by providers in the medical record.

cRandomization occurred prior to hospitalization or ≤2 days of hospital admission.

dAs determined by standard-of-care (SOC) method. Total number of organisms identified by SOC method is 233 for SOC arm and 234 for the RAPID (Accelerate Pheno System) arm.

eIsolates with second morphologies detected using SOC are not shown (SOC arm = 2, RAPID arm = 7).

fIncludes Enterobacter (now Klebsiella) aerogenes.

gAs determined by SOC method. Enterobacterales isolates totaled 182 for SOC and 177 for RAPID and included Escherichia coli, Citrobacter species, Enterobacter species, Klebsiella species, Proteus species, and Serratia marcescens.

h Pseudomonas species isolates totaled 24 for SOC and 29 for RAPID.

Monomicrobial blood cultures were found in 98% of SOC and 95% of RAPID patients. Escherichia coli was the most commonly identified organism in blood cultures, being found in nearly half of both arms (Table 1). Arms were similar in terms of the identified microorganisms (Table 1), resistance phenotypes (Table 1), and antibiotics used within the first 72 hours of randomization (Supplementary Table 1). The number of antimicrobial-resistant GNB was low and similar between arms (Table 1).

Primary Outcome

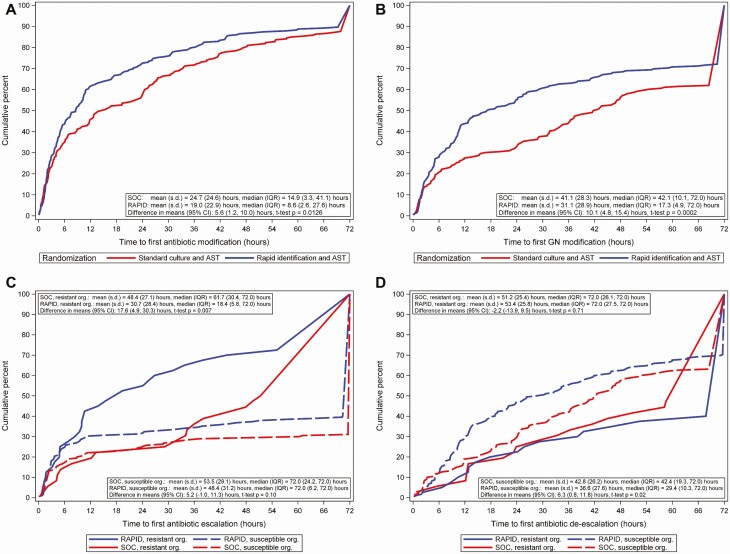

The time (hours) from randomization to first antibiotic change was faster in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm (median [interquartile range, IQR]: RAPID, 8.6 [2.6–27.6] vs SOC, 14.9 [3.3–41.1] hours; difference, 6.3 hours; P = .02; Figure 2A). The difference in primary outcome was slightly greater when antibiotic changes made within the first 1 and 2 hours after randomization were excluded in a sensitivity analysis (Table 2). The primary outcome was faster in the RAPID arm vs the SOC arm among patients who were not neutropenic at baseline or had a Pitt bacteremia score ≥2 but did not differ between the arms in the other prespecified subgroup analyses (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Time from randomization to antibiotic changes by treatment arm in the modified intention-to-treat population. A, Time from randomization to first antibiotic modification by treatment arm. For patients who died within 72 hours, the time of earliest antibiotic modification was used as the time to modification. Patients who did not have antibiotic modifications were assigned a time of 72 hours. No censoring was observed. Includes time to first antibiotic modification for 8 patients who died within 72 hours of randomization. B, Time from randomization to first gram-negative antibiotic modification by treatment arm. Patients who did not have gram-negative antibiotic modifications were assigned a time of 72 hours. Includes time to first gram-negative antibiotic modification for 8 patients who died within 72 hours of randomization. C, Time from randomization to first antibiotic escalation in gram-negative or gram-positive antibiotics by treatment arm and isolate resistance. Resistance is defined as third-generation cephalosporin nonsusceptible Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, or carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas species. Isolates with intermediate susceptibility were considered resistant. Resistant organisms: n = 36 for SOC and 40 for RAPID. Susceptible organisms: n = 190 for SOC and 182 for RAPID. Patients who did not have antibiotic escalation were assigned a time of 72 hours. Antibiotic escalation was assessed by local stewardship providers. D, Time from randomization to first antibiotic deescalation in gram-negative or gram-positive antibiotics by treatment arm and isolate resistance. Resistance is defined as third-generation cephalosporin nonsusceptible Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, or carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas species. Isolates with intermediate susceptibility were considered resistant. Resistant organisms: n = 36 for SOC and 40 for RAPID. Susceptible organisms: n = 190 for SOC and 182 for RAPID. Patients who did not have antibiotic deescalation were assigned a time of 72 hours. Antibiotic deescalation was assessed by local stewardship providers. Abbreviations: AST, antibiotic susceptibility testing; CI, confidence interval; GN, gram-negative; IQR, interquartile range; Org, organism; RAPID, organism identification and phenotypic AST using the Accelerate Pheno System; s.d., standard deviation; SOC, standard-of-care culture.

Table 2.

Time to First Antibiotic Modification by Treatment Arm Among Subgroups

| Time (hours) from Randomization to First Antibiotic Modification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants |

Standard of Care (N = 226),

Median (IQR) |

RAPID (N = 222),

Median (IQR) |

Difference | P Value a |

| All | 14.9 (3.3–41.1) |

8.6 (2.6–27.6) |

6.3 | .02 |

| Excluding modifications in first 1 hour | 21.2 (5.1–41.7) |

10.0 (3.6–30.4) |

11.2 | <.001 |

| Excluding modifications in first 2 hours | 24.0 (6.8–45.3) |

12.2 (5.4–31.1) |

11.8 | .005 |

| Pitt bacteremia score ≥2b | 15.7 (3.4–38.9) |

7.6 (2.0–30.8) |

8.1 | .02 |

| Pitt bacteremia score <2c | 14.4 (3.2–41.5) |

9.3 (3.7–27.6) |

5.1 | .50 |

| In ICU at randomizationd | 11.8 (2.5–33.8) |

8.0 (2.0–22.9) |

3.8 | .13 |

| Not in ICU at randomizatione | 16.2 (3.6–41.8) |

8.7 (2.8–32.5) |

7.4 | .10 |

| Neutropenic at randomizationf | 20.8 (3.1–41.1) |

9.5 (2.4–30.4) |

11.3 | .63 |

| Not neutropenic at randomizationg | 14.4 (3.3–41.6) |

7.5 (2.6–27.0) |

6.9 | .02 |

| Excluding metronidazole | 19.3 (3.3–42.3) |

9.3 (2.8–30.4) |

10.0 | .02 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range.

aThe t test for difference in means; Wilcoxon rank sum test for difference in medians.

bn = 141 for standard-of-care (SOC) and 151 for RAPID (Accelerate Pheno System).

cn = 85 for SOC and 71 for RAPID.

dn = 64 for SOC and 80 for RAPID.

en = 162 for SOC and 142 for RAPID.

fn = 43 for SOC and 30 for RAPID.

gn = 183 for SOC and 192 for RAPID.

Secondary and Other Outcomes

Antibiotic changes in both arms were more common in gram-negative than gram-positive antibiotics. Among the mITT population, initial antibiotic changes were assessed by AS providers as escalation in gram-negative therapy in 162 (36%), escalation in gram-positive therapy in 16 (4%), deescalation in gram-negative therapy in 185 (41%), and deescalation in gram-positive therapy in 97 (22%) patients. The proportion of patients with any gram-negative antibiotic changes was higher in the RAPID arm than the SOC arm; by 24 hours postrandomization, gram-negative modifications had occurred for 55% of patients in the RAPID arm vs 33% of patients in the SOC arm.

Time to first gram-negative antibiotic change was faster in the RAPID arm vs the SOC arm (median [IQR]: RAPID, 17.3 [4.9–72] vs SOC, 42.1 [10.1–72] hours; difference, 24.8 hours; P < .001; Figure 2B). Type of antibiotic change (ie, escalation or deescalation) varied by antibiotic resistance of the blood isolate. Among patients with resistant organisms (defined as blood culture with third-generation cephalosporin not-susceptible Enterobacterales, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales, or carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas species), time to first antibiotic escalation was significantly faster in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm (median [IQR]: RAPID, 18.4 [5.8–72] vs SOC, 61.7 [30.4–72] hours; difference, 43.3 hours; P = .01), but time to deescalation did not differ between the arms (Figure 2C). In contrast, among patients with antimicrobial-susceptible organisms, time to first antibiotic deescalation was faster in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm (median [IQR]: RAPID, 29.4 [10.3–72] vs SOC, 42.4 [19.3–72] hours; difference, 13 hours; P = .02), but time to escalation did not differ between the arms (Figure 2D). Arms did not differ in clinical outcomes including mortality, time to death, and length of stay. In both arms, 10% of patients acquired multidrug-resistant organisms (as defined in Table 3) after randomization. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales occurred in 5 SOC patients and none of the RAPID patients (P = .06; Table 3). Among patients with community-onset infection (defined as randomization ≤2 days prior to admission), there was no difference in total or direct costs of hospitalization between the arms (Supplementary Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes by Treatment Arm

| Outcome | Standard of Care (N = 226) | RAPID (N = 222) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 day mortality, no. (%) | 18 (8) | 25 (11) | .27 |

| Length of stay up to 30 days, mean (standard deviation)a | 8.2 (8.7) | 9.8 (9.8) | .09 |

| Readmission within 30 days, no. (%) | 47 (21) | 40 (18) | .48 |

| In intensive care unit 72 hours after randomization, no. (%) | 39 (17) | 45 (20) | .47 |

| Hospital-onset Clostridioides difficile infection,b no. (%) | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | .77 |

| Acquisition of a MDRO,c no. (%) | 23 (10) | 23 (10) | 1.0 |

| Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus | 8 (4) | 7 (3) | 1.0 |

| Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus species | 6 (3) | 11 (5) | .23 |

| Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteralesd | 5 (2) | 0 | .06 |

| Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosae | 6 (3) | 10 (5) | .32 |

| Acquisition of new hospital-onset C. difficile or MDRO, rate per 10 000 patient days (95% confidence interval) | 123.3 (82–185.6) |

105.5 (70.1–158.8) |

.97f |

Abbreviations: MDRO, multidrug-resistant organism.

aFor patients alive at 30 days (standard of care = 208, RAPID [Accelerate Pheno System] = 197).

bDefined as a positive laboratory test for C. difficile collected after randomization and on or after day 4 of hospitalization, up to 30 days while still in the hospital.

cNew acquisition within 30 days defined as no organism detected in clinical or surveillance cultures in the 3 months prior to randomization, or culture results from 3 months prior to randomization are unknown.

dDefined as resistant to imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and doripenem.

eDefined as resistant to aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems.

f P value calculated using Poisson regression.

Antibiotics used between the arms were similar (Supplementary Table 1). AS recommendations were made for more patients in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm within 24 hours (51% vs 28%, P ≤ .001) and 72 hours (66% vs 50%, P ≤ .001) of randomization (Supplementary Table 2).

In RAPID arm patients, 260 isolates were identified by the SOC method. Among these, 235 (90%) were organisms present on the RAPID panel (on-panel) and 25 (10%) were off-panel organisms. Among patients randomized to the RAPID arm who had on-panel organisms, RAPID provided faster results than SOC for organism ID (mean [SD] 2.7 [1.2] hours vs 14.5 [42.3] hours; P < .001) and AST (13.5 [56.0] hours vs 49.6 [15.6] hours; P < .001; Supplementary Table 4). Among on-panel organisms, 88% of organism ID results were concordant between RAPID and SOC methods and 12% were identified by SOC but not RAPID (Supplementary Table 5). Among 2112 antibiotic susceptibility tests performed using both RAPID and SOC for on-panel isolates, there were 115 (5%) minor errors, 24 (1%) major errors, and 2 (0.1%) very major errors (Supplementary Table 6).

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter trial, we found that among patients with GNB BSIs, rapid organism ID and phenotypic AST led to significantly faster antibiotic modifications compared with SOC testing, likely reflecting an earlier switch from empirical to pathogen-directed antibiotic therapy in the RAPID arm. Several studies have demonstrated that rapid blood culture diagnostics may shorten time to optimal antibiotic therapy for BSIs caused by gram-positive organisms [15, 19, 20]. However, the testing platforms used detected only a few resistance genes and are not ideal for GNB, which have diverse resistance mechanisms. The diagnostic test used in this trial provided rapid phenotypic AST, providing optimal information to tailor antibacterial management of GNB BSIs.

The RAPID test had few discrepancies compared with conventional methods of organism ID and AST. On-panel organisms may not have been identified by the RAPID test because of poor mixing (the company changed the mixing protocol after the study), the presence of a low number of cells in the sample, the presence of slow-growing organisms, or other factors. The most common AST discrepancies observed between RAPID and conventional testing were minor errors (ie, intermediate by one method and susceptible or resistant by the other method); such “wobble” around the breakpoint can occur even when the same susceptibility assay is repeated using identical isolates. The RAPID test generally yielded more resistant results than conventional AST methods and was thus unlikely to lead to undertreatment of patients.

Rapid testing enabled gram-negative antibiotic modifications to occur a median of 24.8 hours faster than SOC, which is a clinically significant time frame for patients with sepsis and is a more dramatic difference than reported in a recent pre–post intervention study that evaluated the impact of the RAPID platform [21]. Notably, RAPID enabled timely antibiotic escalations to occur almost 2 days faster for patients with antimicrobial-resistant infections, which can be life-saving especially if empirical antibiotics are ineffective [6, 22]. Additionally, more AS recommendations were made in the RAPID arm than in the SOC arm, and many antibiotic changes involved antibiotic deescalation, especially among patients without resistant organisms, suggesting that rapid blood culture diagnostics can support efforts to promote judicious antibiotic use. Timely antibiotic deescalation may be clinically significant, as antibiotic exposures as short as 1 day have been shown to increase risks of bacteremia [23] and C. difficile infection [24, 25] and to reduce microbiome richness [26].

Strengths of this study include its pragmatic trial design and incorporation of baseline activities of AS programs, which have been shown to optimize clinical impact of diagnostics [15, 27]. This study also had limitations. The rapid testing platform did not have targets to identify one-third of the GNB that grew in blood cultures and did not test all clinically important antibiotics for susceptibility. The rapid testing platform also required that blood cultures be placed on the instrument within 8 hours of turning positive. In laboratories that are not open 24 hours/day, this can prevent blood cultures that turn positive overnight from undergoing RAPID testing, as was observed in one of the centers in our study. Thus, the rapid testing platform may not be sufficient to fully replace SOC AST. The study had insufficient power to detect differences in clinical outcomes and was not designed to assess compliance with AS recommendations nor appropriateness of antibiotic modifications. The study sites that were included did not have high rates of multidrug-resistant GNB; thus, empirical antibiotic therapy was likely effective in the majority of patients, potentially limiting our ability to detect differences in mortality or other clinical outcomes. Findings may not be applicable to settings with higher resistance rates or those that do not use MALDI-TOF as standard of care, where rapid testing may actually have greater impact. Results may also not be generalizable to settings without stewardship programs, where RAPID may have reduced impact. Although the arms were balanced with regard to many baseline characteristics, more patients were in the ICU at randomization in the RAPID arm compared with the SOC arm, and it is possible that having sicker patients in the RAPID arm may have reduced the observed impact of the intervention. Due to logistical challenges, patients were not enrolled evenly between the 2 sites. Last, we did not perform a formal cost-effectiveness analysis, which is warranted since novel rapid blood culture diagnostics are more costly than conventional testing methods.

Despite these limitations, RAPID demonstrates that rapid phenotypic AST methods implemented together with AS can facilitate faster antibiotic modifications during treatment of GNB BSIs and aid clinicians in providing timely, effective therapy, while supporting AS efforts. Development of rapid, innovative methods for detection of microorganisms and drug resistance in blood cultures is an important component in the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support . This study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH (award UM1AI104681). Accelerate Diagnostics provided instruments, technical support, and half of the Accelerate Pheno assays but had no other role in the trial.

Potential conflicts of interest. R. B. reports grants from Biomerieux, Roche, and Biofire outside the submitted work. S. B. D. reports personal fees from Genentech and Basilea Pharmaceutica outside the submitted work. R. P. reports grants from CD Diagnostics, Merck, Hutchison Biofilm Medical Solutions, ContraFect, TenNor Therapeutics Limited, Shionogi, and Accelerate Diagnostics; consulting fees from Curetis, Specific Technologies, Next Gen Diagnostics, PathoQuest, Selux Diagnostics, 1928 Diagnostics, PhAST, and Qvella; travel reimbursement from America Society of Microbiology and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA); honoraria from IDSA, National Board of Medical Examiners, and Up-to-Date; and Infectious Diseases Board Review Course outside the submitted work. R. P. has a patent Bordetella pertussis/parapertussis polymerase chain reaction issued, a patent method for sonication with royalties paid to Mayo Clinic, and a patent antibiofilm substance issued. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Albrecht SJ, Fishman NO, Kitchen J, et al. Reemergence of gram-negative health care-associated bloodstream infections. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stryjewski ME, Boucher HW. Gram-negative bloodstream infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2009; 34(Suppl 4):S21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. ; EPIC II Group of Investigators . International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 2009; 302:2323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ibrahim E, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser V, Kollef M. The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest 2000; 118: 46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:745–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006; 34:1589–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee YT, Kuo SC, Yang SP, et al. Impact of appropriate antimicrobial therapy on mortality associated with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia: relation to severity of infection. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lodise TP Jr, Patel N, Kwa A, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007; 51:3510–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moehring RW, Sloane R, Chen LF, et al. Delays in appropriate antibiotic therapy for gram-negative bloodstream infections: a multicenter, community hospital study. PLoS One 2013; 8:e76225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Mortality and delay in effective therapy associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007; 60:913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller MB, Atrzadeh F, Burnham C-AD, et al. Clinical utility of advanced microbiology testing tools. J Clin Microbiol 2019; 57:e00495–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang AM, Newton D, Kunapuli A, et al. Impact of rapid organism identification via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight combined with antimicrobial stewardship team intervention in adult patients with bacteremia and candidemia. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 57:1237–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Perez KK, Olsen RJ, Musick WL, et al. Integrating rapid pathogen identification and antimicrobial stewardship significantly decreases hospital costs. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2013; 137:1247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perez KK, Olsen RJ, Musick WL, et al. Integrating rapid diagnostics and antimicrobial stewardship improves outcomes in patients with antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteremia. J Infect 2014; 69:216–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banerjee R, Teng CB, Cunningham SA, et al. Randomized trial of rapid multiplex polymerase chain reaction-based blood culture identification and susceptibility testing. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1071–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Accelerate Diagnostics, Inc. Accelerate PhenoTest BC kit instructions for use. Tucson, AZ: Diagnostics, Inc, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pantel A, Monier J, Lavigne J-P. Performance of the Accelerate PhenoTM system for identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of a panel of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacilli directly from positive blood cultures. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:1546–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. ; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America . Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:431–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nguyen DT, Yeh E, Perry S, et al. Real-time PCR testing for mecA reduces vancomycin usage and length of hospitalization for patients infected with methicillin-sensitive staphylococci. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48:785–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pardo J, Klinker KP, Borgert SJ, Butler BM, Giglio PG, Rand KH. Clinical and economic impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions with the FilmArray blood culture identification panel. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 84:159–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ehren K, Meisner A, Jazmati N, et al. Clinical impact of rapid species identification from positive blood cultures with same-day phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing on the management and outcome of bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 70:1285–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lodise T, Berger A, Altincatal A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance or delayed appropriate therapy— Does one influence outcomes more than the other among patients with serious infections due to carbapenem-resistant versus carbapenem-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6:ofz194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gouliouris T, Warne B, Cartwright EJP, et al. Duration of exposure to multiple antibiotics is associated with increased risk of VRE bacteraemia: a nested case-control study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73:1692–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seddon MM, Bookstaver PB, Justo JA, et al. Role of early de-escalation of antimicrobial therapy on risk of Clostridioides difficile infection following Enterobacteriaceae bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:414–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Webb BJ, Subramanian A, Lopansri B, et al. Antibiotic exposure and risk for hospital-associated Clostridioides difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64:e02169–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rooney AL, Timberlake K, Brown KA, et al. Each additional day of antibiotics is associated with lower gut anaerobes in neonatal intensive care unit patients. Clin Infect Dis 2019. pii:ciz698. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pliakos EE, Andreatos N, Shehadeh F, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. The cost-effectiveness of rapid diagnostic testing for the diagnosis of bloodstream infections with or without antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Micro Reviews 2018; 31:e00095–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.