Abstract

Psoriasis, a chronic inflammatory skin disease, negatively impacts patients’ quality of life (QoL). This randomized, phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, multicenter study evaluated the efficacy and safety of brodalumab, a human anti‐interleukin‐17 receptor A monoclonal antibody, in Korean patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Coprimary end‐points were the percentage of patients with 75% or more improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75) and static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) success (score 0/1) at week 12. Secondary end‐points included the percentage improvement from baseline in PASI score and proportion of patients with PASI 50/75/90/100 responses. QoL was assessed with the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Eligible patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 210 mg (N = 40) or placebo (N = 22) every 2 weeks (Q2W) at a 2:1 ratio for 12 weeks. Subsequently, all patients entered an open‐label extension phase and received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W until week 62. At week 12, the proportion of patients who achieved the coprimary end‐points, PASI 75 and sPGA success, was significantly higher in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group compared with the placebo group (92.5% vs 0%). At week 12, the mean ± SD percentage improvement in the PASI score was 96.87 ± 6.01% in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, which was maintained until study end (week 64). PASI 50/75/90 responses were achieved by 100% of patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W at weeks 6, 13, and 24, respectively; PASI 100 was achieved by 82.8% of patients at week 64. Brodalumab treatment rapidly improved DLQI scores. The most common treatment‐emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, tinea pedis, and urticaria. Overall, treatment with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W resulted in a rapid and significant clinical benefit and was well tolerated in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Korea.

Keywords: brodalumab, efficacy, Korea, psoriasis, safety

Abbreviations

- AE

adverse events

- BSA

body surface area

- C‐SSRS

Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- DLQI

Dermatology Life Quality Index

- EU

European Union

- FAS

full analysis set

- IL

interleukin

- IL‐17RA

interleukin‐17 receptor A

- IP

investigational product

- IWRS

interactive web response system

- NAPSI

Nail Psoriasis Severity Index

- PASI

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

- PHQ‐8

Patient Health Questionnaire‐8

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- PPS

per‐protocol set

- PSSI

Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index

- Q2W

every 2 weeks

- QoL

quality of life

- SAE

serious adverse events

- SAS

safety analysis set

- SIB

suicidal ideation and behavior

- sPGA

static Physician’s Global Assessment

- TEAE

treatment‐emergent adverse events

- Th

T‐helper

- URTI

upper respiratory tract infection

1. INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, non‐communicable, recurrent, immune‐mediated skin disease, 1 , 2 , 3 with plaque psoriasis being the most common phenotype. 2 , 4 Results from a population‐based epidemiological study in Korea from 2015 reported that the crude prevalence of psoriasis was 459/100 000 individuals, with a male : female ratio of approximately 1.3:1. Overall, 83.8% of patients had plaque psoriasis and 22.6% had moderate to severe psoriasis. 5 Occasionally, reproducing local clinical data for the approval of a new medication may seem inefficient, considering the efforts, expenditure, and time. However, in the area of psoriasis, separate clinical trials in East Asian countries, especially Korea, need to be performed not just for regulatory processes but also because Korean patients present with a unique subtype of psoriasis, small plaque type, in contrast to large plaque‐type psoriasis in Western countries. 6

Psoriasis causes great physical, emotional, and social burden. 3 , 7 There is an urgent need for effective treatment options that are cost‐effective and will improve overall patients’ QoL. In line with other autoimmune inflammatory conditions, novel CD4+ Th cells called Th17 cells are involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. 8 Consequently, targeting the IL‐17 signaling pathway has proven to be effective in the treatment of psoriasis. 9 Brodalumab is a human anti‐IL‐17RA monoclonal antibody that inhibits the biological activity of IL‐17A, IL‐17F, and other IL‐17 isoforms. 10 The efficacy and safety of brodalumab have been demonstrated in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in three phase III trials, AMAGINE‐1/2/3, 11 , 12 where brodalumab showed superior skin clearance efficacy at week 12 compared with placebo and ustekinumab. 12 Furthermore, the long‐term efficacy and safety of brodalumab were demonstrated over more than 2 years in the open‐label extension of the AMAGINE‐2 trial. 13 Similarly, results from a 12‐week phase II trial followed by a 52‐week extension study reported that brodalumab was effective and well tolerated in a Japanese population with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, thereby confirming the results of previous studies in Caucasian patients. 14 , 15 On the basis of these results, brodalumab was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in the USA, EU, and Japan. 16

Therefore, the objective of this phase III study was to assess the efficacy and safety of brodalumab in Korean patients to offer a novel therapeutic option for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Korea.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

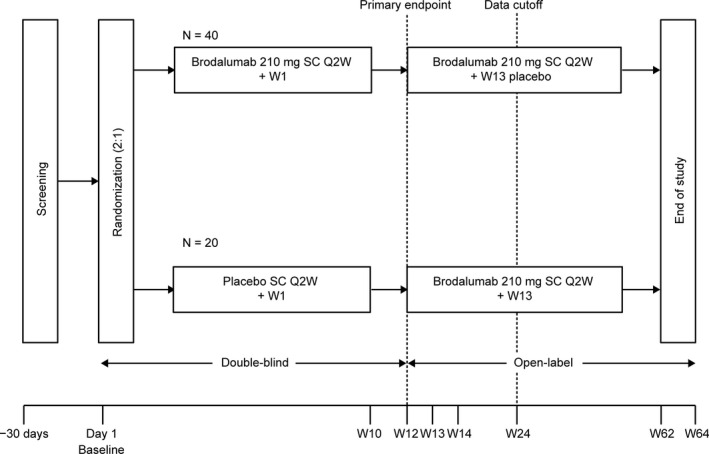

This phase III, randomized, multicenter study consisted of a 12‐week double‐blind phase followed by a 52‐week open‐label extension phase (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02982005). During the double‐blind phase, patients were randomized to receive brodalumab 210 mg Q2W or placebo for 12 weeks at a 2:1 ratio and were stratified by bodyweight at screening (≤70 kg, >70 kg), prior use of biologic agents, and investigative site. Randomization was performed through a dynamic allocation procedure using an IWRS. The IP was administrated after coordination with the IWRS vendor, Cenduit, an IQVIA business (Durham, NC, USA). At week 12, all patients entered an open‐label extension phase and received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W for the remainder of the study. Patients in the placebo group received an additional dose of brodalumab 210 mg at week 13. To maintain blindness of the original randomized group, patients received blinded brodalumab 210 mg or placebo at week 13 (brodalumab 210 mg for those originally randomized to placebo and placebo for those originally randomized to brodalumab 210 mg) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design. Q2W, every 2 weeks; SC, subcutaneous; W, week

The trial protocol and its subsequent amendments were approved by each site’s institutional review board/ethics committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Good Clinical Practice guidelines and adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

2.2. Patients

Patients were enrolled from 10 clinical sites in Korea. Patients in this study were aged over 20 years at the time of consent; had stable moderate to severe plaque psoriasis for 6 months or more before the first dose of IP, psoriasis‐affected BSA of 10% or more, a PASI score of 12 or more, and an sPGA score of 3 or more at screening and baseline; a history of at least one phototherapy or systemic psoriasis therapy; and no findings suggestive of tuberculosis. Negative results for hepatitis B virus surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibody, HIV, and human T‐cell lymphotropic virus type 1 antibody were also required.

Patients were excluded if they were diagnosed with skin conditions that would interfere with the interpretation of results; had erythrodermic, pustular, guttate psoriasis, or medication‐induced psoriasis; a history of Crohn’s disease, myocardial infarction, or unstable angina pectoris within the preceding year; any systemic disease considered by the investigator to be clinically significant and uncontrolled; active malignancy or a history of malignancy within 5 years; had received a live vaccine within 28 days of the first dose of IP; and received anti‐IL biologic therapy within 12 weeks prior to the first dose of IP. In addition, patients with a history or evidence of SIB, based on an assessment with the C‐SSRS, and severe depression, based on a total score of 15 or more on the PHQ‐8 at screening or baseline, were also excluded from the study.

A washout period was required for patients who received systemic therapy, phototherapy, or treatment with biologic agents. The use of upper mid‐strength or lower‐potency topical steroids was permitted during the study on the face, axillae, and groin only; however, their use was prohibited on the day of site visits.

2.3. Intervention

Eligible patients were administrated brodalumab 210 mg or placebo on the day of enrollment or within 3 days of enrollment. Patients received two s.c. injections via the anterior upper abdomen, thigh, or upper arm on day 1 and subsequently at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and Q2W thereafter, until week 62. The dosing regimen included brodalumab 210 mg (two prefilled syringes of 70 mg [0.5 ml] and 140 mg [1.0 ml]) and placebo (two prefilled syringes of 0.5 ml and 1.0 ml). The dose was selected based on the results from previous phase II and III clinical studies for plaque psoriasis. 11 , 14 , 17 From week 28, brodalumab 210 mg Q2W was self‐administrated until week 62.

2.4. Assessments

2.4.1. Efficacy

The coprimary end‐points were the number and percentage of patients achieving PASI 75 at week 12 and the number and percentage of patients with an sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) at week 12.

Secondary end‐points included the percentage improvement from baseline in the PASI score, the proportion of patients with a 50% or more (PASI 50), 75% or more (PASI 75), 90% or more (PASI 90), and 100% or more (PASI 100) reduction in the PASI score from baseline, the proportion of patients with an sPGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), and the proportion of patients with decreased psoriasis BSA involvement (0–100%). NAPSI and PSSI were assessed in patients who had nail and scalp symptoms at baseline, respectively. Patient QoL was assessed using the DLQI before the assessment of PASI and sPGA scores for the skin lesions. 18

2.4.2. Safety

Safety was evaluated by continuous monitoring of TEAE (including drug‐related TEAE), and SAE and was summarized by treatment group. CTCAE version 4.0 was used to grade AE severity. Changes in laboratory, hematological, and chemical parameters, vital signs, and urinalysis from baseline were assessed. Anti‐brodalumab antibody status (detected using an electrochemiluminescent immunoassay) was assessed at baseline and weeks 12, 24, 48, and 64. In addition, tuberculosis tests were performed at screening and weeks 12, 16, 24, 36, 48, and 64.

2.4.3. Pharmacokinetics

Serum samples for the PK assessment were collected from patients in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W treatment group at baseline and weeks 8, 10, 12, and 24, prior to the dose, at trough. Serum brodalumab was assessed using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay with individual serum brodalumab concentrations below the lower limit of quantification (0.0500 μg/mL) considered as “BLQ” during the calculation of descriptive statistics.

2.4.4. Additional assessments

The 8‐item PHQ depression scale, PHQ‐8, was used to evaluate the severity of depression, 19 and the C‐SSRS was used to assess the presence and severity of SIB. 20

2.5. Statistical analysis

The populations analyzed were the FAS, which included all randomized patients; the PPS, which included all patients in the FAS but excluded those who had received no treatment, had no post‐dosing primary efficacy data available, failed to meet major eligibility criteria, or had major protocol deviations; the SAS, which included all randomized patients who received one or more doses of the study drug; and the PK analysis set, which included all randomized patients with the exception of those who were not exposed to brodalumab or for whom blood collection was not performed after brodalumab dosing.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were summarized. Categorical data were summarized using frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics. The Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test was performed with stratification of bodyweight at screening (≤70 kg, >70 kg), prior use of biologic agents, and investigative site to examine the treatment difference in the PASI 75 response and sPGA success at week 12 using the last observation carried forward method or non‐responder imputation method for missing data. The percentage improvement from baseline in PASI scores was summarized by visit and assessed using an ANOVA model with treatment group, strata of total bodyweight at screening (≤70 kg, >70 kg), prior use of biologic agents, and investigative site as variables. In addition, percentage improvement from baseline in PASI 50, 75, 90, and 100 score, sPGA success (score 0/1), an sPGA score of 0 (clear) over time, and mean ± SD baseline improvements in BSA, NAPSI, PSSI, and DLQI scores were analyzed over time.

Safety was evaluated by continuous monitoring of TEAE and SAE, which were tabulated by system organ class and preferred term. A TEAE was defined as any event that occurred or worsened after study drug administration. The serum concentrations of brodalumab were summarized by descriptive statistics at each sampling point. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Based on an integrated summary of brodalumab phase III studies, a total sample size of 60 patients (40 in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 20 in the placebo group) was considered appropriate to achieve a more than 90% power to detect a minimal treatment difference of 75%–80% between the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W and the placebo groups.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population

The study was conducted between January 11, 2017, and August 14, 2018. Of the 70 patients screened, 62 were randomized to receive treatment; 40 patients received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W and 22 patients received placebo. A total of 62 patients were evaluable for the FAS and SAS. However, six patients were excluded from the PPS (two patients from the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and four patients from the placebo group) owing to the use of topical steroids.

Overall, the percentage of male patients was lower in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group than in the placebo group (57.5% and 68.2%, respectively). The mean age of patients was 43.5 years in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 43.7 years in the placebo group, and the mean disease duration of psoriasis was 10.9 years in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 13.6 years in the placebo group. A greater percentage of patients in the placebo group (36.4%) reported previous use of any biologics compared with those in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group (10%). Most patients were previously treated with non‐biologic systemic agents or phototherapy (92.5% in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 86.4% in the placebo group). In general, the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at baseline were balanced across the treatment groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline: full analysis set

| Characteristic | Placebo (N = 22) |

Brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (N = 40) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 7 (31.8) | 17 (42.5) |

| Male | 15 (68.2) | 23 (57.5) |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 43.7 ± 15.8 | 43.5 ± 14.3 |

| Weight at baseline (kg), mean ± SD | 72.76 ± 13.6 | 70.97 ± 15.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 25.52 ± 4.6 | 25.76 ± 4.4 |

| Disease duration of psoriasis (years), mean ± SD | 13.62 ± 10.0 | 10.93 ± 9.8 |

| Baseline PASI score, mean ± SD | 25.96 ± 11.0 | 23.25 ± 9.9 |

| Baseline sPGA score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 3 | 16 (72.7) | 26 (65.0) |

| 4 | 6 (27.3) | 14 (35.0) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Baseline BSA involvement (%), mean ± SD | 37.1 ± 21.2 | 33.5 ± 19.4 |

| Prior biologic use, n (%) | ||

| No | 14 (63.6) | 36 (90.0) |

| Yes | 8 (36.4) | 4 (10.0) |

| Failure of prior biologic psoriasis therapies, n (%) | ||

| No | 18 (81.8) | 38 (95.0) |

| Yes | 4 (18.2) | 2 (5.0) |

| Prior non‐biological systemic or phototherapy, n (%) | ||

| No | 3 (13.6) | 3 (7.5) |

| Yes | 19 (86.4) | 37 (92.5) |

| Baseline PSSI score, mean ± SD | 28.0 ± 18.1 | 24.6 ± 17.1 |

| Baseline NAPSI score, mean ± SD | 6.9 ± 3.7 | 4.6 ± 3.4 |

| Baseline DLQI total score, mean ± SD | 15.1 ± 8.5 | 13.9 ± 7.8 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PSSI, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks; sPGA, static Physician’s Global Assessment every 2 weeks.

3.2. Patient disposition

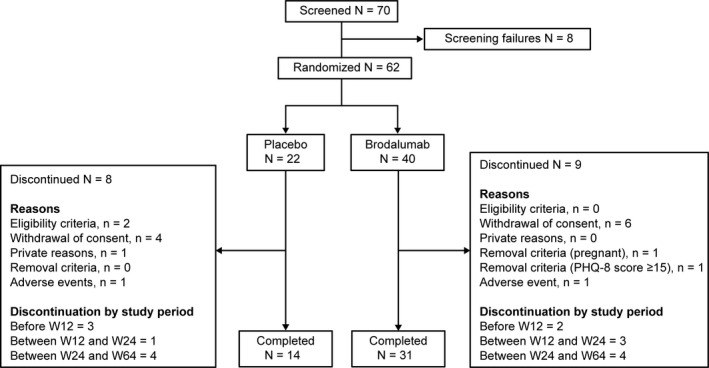

Overall, 57 (91.9%) patients completed the double‐blind treatment phase and 45 (72.6%) continued treatment through week 64 (31 in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 14 in the placebo group). Of the 17 (27.4%) patients who discontinued from the study, nine were from the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and eight were from the placebo group. Overall, five patients (two in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and three in the placebo group) discontinued the study before week 12, four patients (three in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and one in the placebo group) discontinued between weeks 12 and 24, and eight patients (four each in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W and placebo groups) discontinued between weeks 24 and 64. The most common reason for discontinuation was withdrawal of consent. Patient disposition is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition. PHQ‐8, Patient Health Questionnaire‐8; W, week

3.3. Efficacy

3.3.1. Primary end‐points

At week 12, the proportion of patients who achieved the coprimary end‐points, PASI 75 and sPGA success (score 0 or 1), was significantly higher in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group compared with the placebo group (92.5% vs 0%, P < 0.001, for both) (Table 2). Similar results were observed with the PPS, where 92.1% of patients in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group achieved the coprimary end‐points compared with no patients in the placebo group (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Analysis of PASI 75 response and sPGA success at week 12 (NRI) a

| Primary endpoint | Analysis parameters |

Placebo N = 22 |

Brodalumab 210 mg Q2W N = 40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PASI 75 (FAS) | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 37 (92.5) |

| 95% CI | 0.0–15.4 | 79.6–98.4 | |

| P‐value* | <0.001 | ||

| Rate difference (%) | 92.5 | ||

| sPGA (FAS) | n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 37 (92.5) |

| 95% CI | 0.0–15.4 | 79.6–98.4 | |

| P‐value* | < 0.001 | ||

| Rate difference (%) | 92.5 | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FAS, full analysis set; NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks; sPGA, static Physician’s Global Assessment every 2 weeks.

Non‐responder imputation was applied for analysis.

P‐value was calculated using Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by total bodyweight at screening (≤70 kg, >70 kg), prior use of biologic agent (yes, no), and investigative site.

Improvements ranging 50%–100% for PASI 75 response and sPGA success were observed in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group compared with the placebo group for subgroups, including sex, age, baseline PASI, duration of psoriasis, failure of previous biologic therapy for psoriasis, or investigative sites, at week 12. Additionally, stratification factors such as bodyweight (≤70 kg, >70 kg) and prior biologic use, classified for dynamic allocation, demonstrated more than 90% rate difference in the treatment group versus the placebo group. The rate difference was similar between the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and the placebo group for each subgroup, indicating that the efficacy of brodalumab 210 mg was not altered by confounding factors (Table S1).

3.3.2. Secondary end‐points

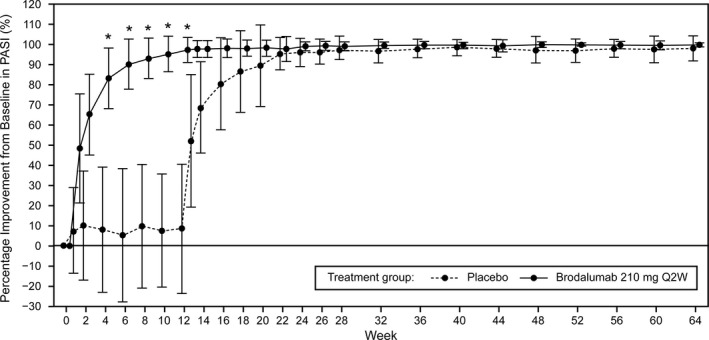

A clinically rapid response in mean ± SD percentage improvements in the PASI score was observed in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group relative to the placebo group within 4 weeks of the study. At week 6, the mean ± SD percentage improvements in PASI scores were greater in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group (89.91 ± 12.27%) compared with the placebo group (5.32 ± 32.99%). At week 12, the mean ± SD percentage improvement was 96.87 ± 6.01% in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, which was maintained throughout the study, with an improvement of 99.57 ± 1.06% observed at week 64. Following administration of brodalumab at week 13, mean ± SD percentage improvements in PASI scores rapidly increased in the placebo group to 51.95 ± 32.77%. Improvements from baseline in PASI scores were similar in both treatment groups in the open‐label extension phase, from week 24 to week 64, when all patients received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean ± SD percentage improvement from baseline in PASI scores over time. *Rapid response in patients treated with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W compared with placebo. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks

Responses of PASI 50, PASI 75, and PASI 90 were achieved by 100% of patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W at weeks 6, 13, and 24, respectively. Complete skin clearance, as indicated by PASI 100 response, was achieved by 82.8% of patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W at week 64. In contrast, no patient receiving placebo achieved PASI 75 response by week 12. However, following administration of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W during the open‐label extension phase, 100% of patients in the placebo group achieved PASI 50 and 75 responses by weeks 22 and 24, respectively, and 82.4% and 47.1% of patients achieved PASI 90 and 100 responses by week 24, respectively (Figure S1).

The proportion of patients who achieved sPGA success (score 0 or 1) rose rapidly in the first 4 weeks following treatment with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, increasing from 38.5% at week 1 to 92.3% at week 4. At week 12, 97.4% of patients in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group achieved sPGA success and 76.3% had an sPGA score of 0 (clear). By week 64, 100% of patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W reported sPGA success and 89.7% had an sPGA score of 0. In contrast, no patient in the placebo group achieved sPGA success or an sPGA score of 0 (clear) until week 12. However, after patients in the placebo group received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, the proportions of patients achieving sPGA success and an sPGA score of 0 (clear) at week 64 increased to 92.9% and 71.4%, respectively (Figure S2).

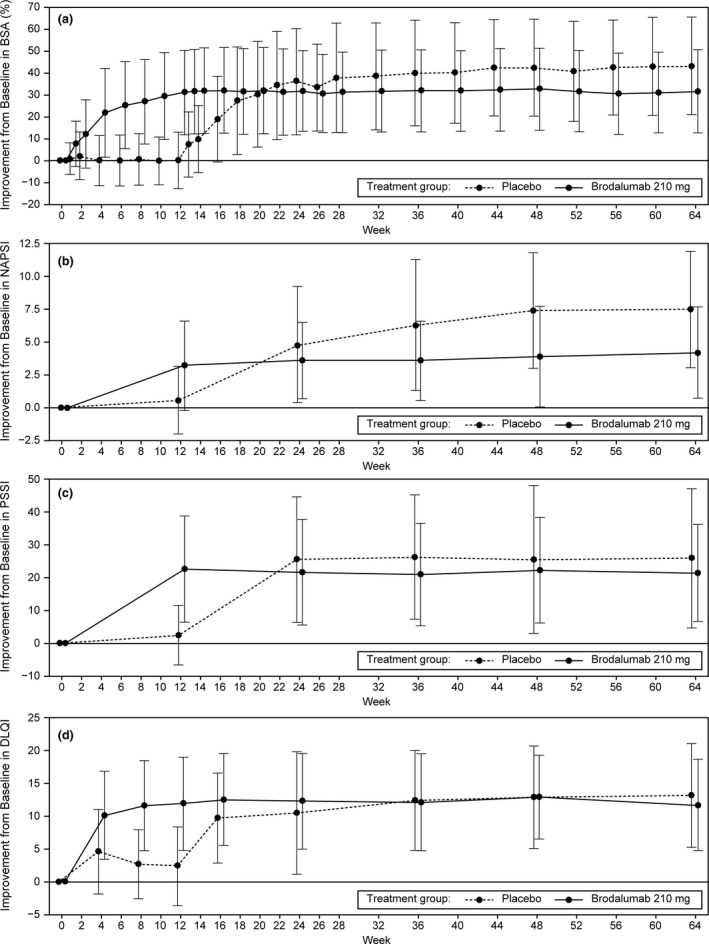

The reduction in BSA involvement with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W was rapid, occurring between weeks 1 and 4. The mean ± SD improvement from baseline in BSA involvement was 31.2 ± 19.3% in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group at week 12; this was maintained at week 64 (31.6 ± 18.8%). Similar results were observed in the placebo group from week 24 to week 64, when all patients received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, with a mean ± SD improvement of 43.2 ± 22.1% at week 64 (Figure 4a). Among patients with nail psoriasis, the mean ± SD improvement from baseline in NAPSI scores was greater in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group (3.2 ± 3.4) compared with the placebo group (0.6 ± 2.6) at week 12. At week 64, the mean ± SD improvements from baseline in NAPSI scores were 4.2 ± 3.5 and 7.5 ± 4.4 in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and placebo group, respectively (Figure 4b). Among patients with scalp psoriasis, the mean ± SD improvement in PSSI scores from baseline to week 12 was greater in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group (22.8 ± 16.2) compared with the placebo group (2.5 ± 9.2). At week 64, the mean ± SD improvements from baseline in the PSSI scores were 21.6 ± 14.8 and 26.1 ± 21.3 in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and placebo group, respectively (Figure 4c). The DLQI total score improved from baseline (13.9 ± 7.8) to week 12 (1.4 ± 2.4) in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, which was sustained at week 64 (1.2 ± 3.1). In contrast, the DLQI total score in the placebo group only markedly improved during the open‐label extension phase, when all patients received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Mean ± SD percentage improvements from baseline in (a) BSA involvement, (b) NAPSI score, (c) PSSI score, and (d) DLQI score over time. BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PSSI, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks

3.4. Safety

During the double‐blind randomized treatment phase, 21 patients (52.5%) in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group and 11 patients (50%) in the placebo group reported TEAE. Overall, eight (20.0%) patients reported drug‐related TEAE in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, with no such events reported in the placebo group. The most commonly reported TEAE were hordeolum (10.0%, four patients) and tinea pedis (7.5%, three patients) in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, and URTI (9.1%, two patients) and headache (9.1%, two patients) in the placebo group. In an analysis of pooled TEAE for the entire study period of 64 weeks, 45 patients (76.3%) reported TEAE and 25 patients (42.4%) reported drug‐related TEAE. The most commonly reported TEAE were nasopharyngitis (16.9%, 10 patients), URTI (16.9%, 10 patients), tinea pedis (10.2%, six patients), and urticaria (10.2%, six patients). The most commonly reported drug‐related TEAE were hordeolum, tinea pedis, and urticaria (6.8%, four patients each) and nasopharyngitis (5.1%, three patients). Only one patient in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, up to week 64, was diagnosed with candidiasis. The most commonly reported TEAE reported throughout the study are shown in Table S2.

In the pooled analysis for the entire study period of 64 weeks, the exposure‐adjusted event rate per 100 patient‐years was 124.3 for drug‐related TEAE. The most common exposure‐adjusted drug‐related TEAE were hordeolum (rate, 16.8; 10 events), nasopharyngitis (rate, 8.4; five events), and urticaria and tinea pedis (rate, 6.7 each; four events). Overall, nine patients (15.3%) reported CTCAE grade of 3 or more; however, none of these serious TEAE were considered drug related. Two patients who received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W discontinued from the study during the extension phase owing to AE; one patient experienced an increase in blood pressure and tachycardia, which was considered related to the study drug, while the other patient was diagnosed with a solid pseudopapillary pancreatic tumor, which was considered unrelated to the study drug. No clinically important changes were observed in laboratory examinations, including hematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis, and vital signs including weight. No anti‐brodalumab antibodies were detected during the study. Moderate to severe depression was reported in one patient receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, as assessed by a PHQ‐8 score of 16, at week 52. However, there were no findings suggestive of SIB in any patients, as indicated by the C‐SSRS.

3.5. Pharmacokinetics

In the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group, serum concentrations of brodalumab (mean ± SD) were constant from week 8 (16.2 ± 11.0 μg/ml) to week 24 (16.6 ± 14.4 μg/ml). In the placebo group, which received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from week 12, serum concentrations of brodalumab (mean ± SD) were 14.6 ± 14.1 μg/ml at week 24.

4. DISCUSSION

This phase III study further validates the crucial role of the IL‐17 receptor in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. At the end of 12 weeks, patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W achieved the coprimary end‐points, and the efficacy of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W was not affected by confounders. Furthermore, substantial improvements in PASI, BSA, NAPSI, and PSSI scores were observed. Notably, these improvements were observed in all patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, including those patients originally assigned to the placebo group but who later received brodalumab 210 mg Q2W from week 12; this highlights that brodalumab treatment was still able to benefit patients in the placebo group, who appeared to have more severe psoriasis at baseline, even when treatment was started later compared with the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group.

Although cross‐study comparisons are often complicated by variability in parameters, overall, results observed in this study from Korea were consistent with those previously reported from the phase III AMAGINE‐1/2/3 studies performed in populations with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis from the USA, Canada, and EU, and two phase II studies in the Japanese population with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 In line with the results from previous studies, brodalumab 210 mg Q2W was significantly more effective than placebo and provided rapid and significant clinical benefit in terms of PASI responses and sPGA success (score 0 or 1). 11 , 14 Similarly, results of the secondary end‐points were in concordance with other population‐based studies. 13 , 14 , 15 Notably, in line with findings from an integrated analysis of the AMAGINE‐2 and AMAGINE‐3 trials, the efficacy of brodalumab 210 mg was similar regardless of prior biologics use. 21 The efficacy of brodalumab was also sustained across 64 weeks; this finding is in agreement with results from other long‐term studies, thereby providing further supporting evidence that brodalumab is efficacious over the longer term. 13 , 15

Reports indicate that patients who achieve skin clearance have improved QoL‐related outcomes than patients who do not. 22 Moreover, research has shown that a PASI 90 response is necessary to achieve a DLQI of 0 or 1. 23 A majority of patients receiving brodalumab 210 mg Q2W achieved PASI 90 and 100 responses during this study. Similar results have been reported in other studies, 14 , 15 , 24 suggesting that the increased likelihood of achieving complete skin clearance with brodalumab may improve patient QoL relative to other biologic agents with a reduced rate of achieving skin clearance. 13

All patients entered an open‐label extension for 52 weeks after 12 weeks of the double‐blind period. The reported drug‐related TEAE were shown to increase over the entire study period to 25 (42.4%) as compared with eight (20.0%) in the double‐blind period. This study further characterized the safety profile of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W, which was generally well tolerated up to 64 weeks. Despite more TEAE being reported in the extension phase than in the randomized treatment phase owing to the longer timeframe, no remarkable differences were observed in the safety profile of the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group in either the extension phase or the randomized treatment phase. Consistent with previous clinical trials of psoriasis, nasopharyngitis, URTI, tinea pedis, and urticaria were the most commonly reported TEAE during the entire study period, and no patients discontinued treatment due to hypersensitivity or immunogenic events. 11 , 12 Impaired production of IL‐17 could result in the persistence of neutropenia and infections such as tinea pedis and candidiasis. 25 , 26 Indeed, both neutropenia and candidiasis have been reported in patients receiving treatment with brodalumab in previous psoriasis clinical trials. 11 , 12 However, in this study, no neutropenia was observed and only one patient experienced oral candidiasis of moderate severity (CTCAE grade 2); this finding is in line with the results from a phase II study in Japanese patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. 14 Notably, results of an analysis of one phase II and three phase III psoriasis trials reported that 2.7% of patients tested positive for antidrug antibodies after receiving treatment with brodalumab, which was lower than the incidence of antibodies to ustekinumab across the global phase III ustekinumab in studies of psoriasis (~5%), 27 whereas no neutralizing antibodies were observed. 11 , 12 , 17 , 28 , 29 However, no anti‐brodalumab antibodies were detected in any patients tested for anti‐brodalumab antibody in this study. Overall, in concordance with the published literature on brodalumab, 14 , 17 no fatal events occurred.

Patients with psoriasis have high rates of depression and may be at an increased risk of SIB, irrespective of the treatment regimen. 30 Despite the package warning of suicidality, no causal relationship between brodalumab and SIB has been established. 10 , 31 Higher rates of depression, anxiety, self‐harm, and suicidality have been detected in patients with psoriasis than in the general population or in individuals with other dermatological conditions. 31 In this study, patients with a history or evidence of SIB, severe depression, or a psychiatric disorder that could pose a risk to patient safety were excluded. In addition, one patient who reported a psychiatric AE, severe depression (PHQ‐8 score, 16) at week 52, was discontinued from the study. However, based on the C‐SSRS assessment, there were no findings suggestive of SIB in this study. 32 Indeed, results from clinical trials have reported that treatment with brodalumab resulted in improved symptoms of depression and anxiety among patients with psoriasis, and SIB rates were comparable versus treatment with ustekinumab. 11 , 32 SIB events have been reported with other drugs used to treat psoriasis, including adalimumab, apremilast, certolizumab, ixekizumab, and secukinumab. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 As anticipated, and in line with the results of a population PK model based on patients with psoriasis from six clinical trials, 37 mean serum concentrations in the brodalumab 210 mg Q2W group reached steady‐state after 8 weeks of brodalumab treatment.

This study has limitations that need to be acknowledged. The study had a small sample size of only 62 patients, was for a limited duration (64 weeks), and was performed at a limited number of clinical sites.

In conclusion, treatment with brodalumab 210 mg Q2W resulted in a rapid and robust improvement in the symptoms of psoriasis, improved patient QoL, and was well tolerated. The efficacy and safety of brodalumab 210 mg Q2W were maintained throughout the 64‐week trial period, demonstrating the efficacy of brodalumab as a treatment option for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Korea.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Haeyoun Jeong is a full‐time employee of Kyowa Kirin Korea Co., Ltd. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1 PASI 50, 75, 90, and 100 responses over time: full analysis set. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Figure S2 sPGA success over time: full analysis set. Q2W, every 2 weeks; sPGA, static Physician’s Global Assessment.

Table S1 PASI 75 response and sPGA success at week 12 by subgroup

Table S2 Most common TEAE by preferred term (≥5% of patients in either group): safety analysis set

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the brodalumab study investigators, site staff, and patients for granting permission to publish. We thank Min‐Geol Lee from the Department of Dermatology of the Severance Hospital; Tae‐Yoon Kim from the Department of Dermatology of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St Mary’s Hospital; Byung‐Soo Kim and Gun‐Wook Kim from the Department of Dermatology of the Pusan National University Hospital; Sang Woong Youn from the Department of Dermatology of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital; Eun‐So Lee from the Department of Dermatology of the Ajou University Hospital; Min Kyung Shin from the Department of Dermatology of the Kyung Hee University Hospital; and Jeung Hoon Lee from the Department of Dermatology of the Chungnam National University Hospital. This study was sponsored by Kyowa Kirin Korea Co., Ltd. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Shaleen Multani, Ph.D., Mami Hirano, M.S., and Frances Gambling, B.A. (honors), of Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications) and funded by Kyowa Kirin Korea Co., Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1. Greb JE, Goldminz AM, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(suppl_2):ii18–ii23; discussion ii24–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . Global report on psoriasis (2016). [Cited 2020 October 8]. Available from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204417 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dogra S, Mahajan R. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, co‐morbidities, and clinical scoring. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:471–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee JY, Kang S, Park JS, Jo SJ. Prevalence of psoriasis in Korea: a population‐based epidemiological study using the Korean national health insurance database. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:761–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lew W, Lee E, Krueger JG. Psoriasis genomics: analysis of proinflammatory (type 1) gene expression in large plaque (Western) and small plaque (Asian) psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:668–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffiths CEM, Jo SJ, Naldi L, et al. A multidimensional assessment of the burden of psoriasis: results from a multinational dermatologist and patient survey. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:173–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, Kurtz SE, Blauvelt A. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: recent advances on IL‐23 and Th17 cytokines. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2007;9:461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lonnberg AS, Zachariae C, Skov L. Targeting of interleukin‐17 in the treatment of psoriasis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:251–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Food and Drug Administration . SILIQ™ (brodalumab) prescribing information. [Cited 2020 May 26]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761032lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1318–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Puig L, Lebwohl M, Bachelez H, Sobell J, Jacobson AA. Long‐term efficacy and safety of brodalumab in the treatment of psoriasis: 120‐week results from the randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled phase 3 AMAGINE‐2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:352–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakagawa H, Niiro H, Ootaki K. Brodalumab, a human anti‐interleukin‐17‐receptor antibody in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II randomized controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;81(1):44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Umezawa Y, Nakagawa H, Niiro H, Ootaki K. Long‐term clinical safety and efficacy of brodalumab in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1957–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kyntheum approved in the EU for the treatment of adults with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. [Cited 2020 May 26]. Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media‐centre/press‐releases/2017/kyntheum‐approved‐in‐the‐eu‐for‐the‐treatment‐of‐adults‐with‐moderate‐to‐severe‐plaque‐psoriasis‐20072017.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Brodalumab, an anti–interleukin‐17–receptor antibody for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ‐8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Papp KA, Gordon KB, Langley RG, et al. Impact of previous biologic use on the efficacy and safety of brodalumab and ustekinumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: integrated analysis of the randomized controlled trials AMAGINE‐2 and AMAGINE‐3. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strober B, Papp KA, Lebwohl M, et al. Clinical meaningfulness of complete skin clearance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:77–82.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Torii H, Sato N, Yoshinari T, Nakagawa H, Japanese Infliximab Study Investigators. Dramatic impact of a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index 90 response on the quality of life in patients with psoriasis: an analysis of Japanese clinical trials of infliximab. J Dermatol. 2012;39:253–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lebwohl MG, Blauvelt A, Menter A, et al. Efficacy, safety, and patient‐reported outcomes in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis treated with brodalumab for 5 years in a long‐term, open‐label, phase II study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roman M, Chiu MW. Spotlight on brodalumab in the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: design, development, and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:2065–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sahoo AK, Mahajan R. Management of tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea pedis: a comprehensive review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:77–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tsai TF, Ho JC, Song M, et al. Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate‐to‐severe psoriasis: a phase III, randomized, placebo‐controlled trial in Taiwanese and Korean patients (PEARL). J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63:154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bagel J, Lebwohl M, Israel RJ, Jacobson A. Immunogenicity and skin clearance recapture in clinical studies of brodalumab. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:344–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Papp K, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Safety and efficacy of brodalumab for psoriasis after 120 weeks of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1183–90.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koo J, Ho RS, Thibodeaux Q. Depression and suicidality in psoriasis and clinical studies of brodalumab: a narrative review. Cutis. 2019;104:361–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chiricozzi A, Romanelli M, Saraceno R, Torres T. No meaningful association between suicidal behavior and the use of IL‐17A‐neutralizing or IL‐17RA‐blocking agents. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15:1653–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lebwohl MG, Papp KA, Marangell LB, et al. Psychiatric adverse events during treatment with brodalumab: analysis of psoriasis clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:81–9.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Minnema LA, Giezen TJ, Souverein PC, Egberts TCG, Leufkens HGM, Gardarsdottir H. Exploring the association between monoclonal antibodies and depression and suicidal ideation and behavior: a VigiBase study. Drug Saf. 2019;42:887–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong Elke MGJ, Kimball AB, Langley Richard G, Lakdawala N. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmutz JL. Apremilast: beware of suicidal ideation and behaviour. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2017;144:243–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Strober BE, Langley RGB, Menter A, et al. No elevated risk for depression, anxiety or suicidality with secukinumab in a pooled analysis of data from 10 clinical studies in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:e105–e107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Timmermann S, Hall A. Population pharmacokinetics of brodalumab in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;125:16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 PASI 50, 75, 90, and 100 responses over time: full analysis set. PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; Q2W, every 2 weeks.

Figure S2 sPGA success over time: full analysis set. Q2W, every 2 weeks; sPGA, static Physician’s Global Assessment.

Table S1 PASI 75 response and sPGA success at week 12 by subgroup

Table S2 Most common TEAE by preferred term (≥5% of patients in either group): safety analysis set