Abstract

Deutetrabenazine (Austedo, Teva), an approved treatment of chorea in Huntington's disease and tardive dyskinesia in adult patients, is a rationally designed deuterated form of tetrabenazine. Two studies assessed the pharmacokinetics and safety of deutetrabenazine compared with tetrabenazine, and the effects of food on absorption of the deuterated active metabolites, α‐dihydrotetrabenazine (α‐HTBZ) and β‐dihydrotetrabenazine (β‐HTBZ). One study was an open‐label 2‐part study in healthy volunteers; the first part included a crossover single dose of two 15 mg candidate deutetrabenazine formulations in fed and fasted states compared with tetrabenazine 25 mg in the fasted state, and the second part included single and repeated dosing of the commercial formulation of deutetrabenazine (7.5, 15, and 22.5 mg) compared with tetrabenazine 25 mg. The second study was an open‐label 5‐way crossover study in healthy volunteers (n = 32) to evaluate relative bioavailability of 4 dose levels of the commercial formulation of deutetrabenazine (6, 12, 18, and 24 mg) with a standard meal and 18 mg with a high‐fat meal. Both studies confirmed longer half‐lives for active metabolites and lower peak‐to‐trough fluctuations for the sum of the metabolites (total [α+β]‐HTBZ) following deutetrabenazine compared with tetrabenazine (3‐ to 4‐fold and 11‐fold, respectively) in steady‐state conditions. Deutetrabenazine doses estimated to provide total (α+β)‐HTBZ exposure comparable to tetrabenazine 25 mg were 11.4‐13.2 mg. Food had no effect on exposure to total (α+β)‐HTBZ, as measured by AUC. Although the total (α+β)‐HTBZ Cmax of deutetrabenazine was increased by ≈50% in the presence of food, it remained lower than that of tetrabenazine.

Keywords: CYP2D6, deuteration, deutetrabenazine, tetrabenazine

Deutetrabenazine (Austedo; Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd, Petah Tikva, Israel) is a vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor approved in 2017 for the treatment of chorea associated with Huntington's disease (HD) and tardive dyskinesia (TD) in adult patients. In the FIRST‐HD trial of patients with HD, deutetrabenazine taken twice a day significantly improved chorea, with the mean Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale total maximal chorea score dropping from 12.1 at baseline to 7.7 in weeks 9‐12, a mean −2.5‐unit difference compared with placebo treatment. There was also significant improvement in overall motor function and no increase in adverse events compared with placebo. 1 , 2 In the ARM‐TD and AIM‐TD studies, deutetrabenazine significantly reduced TD as measured by a change in the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale scores with favorable safety and tolerability. 3 , 4 , 5

Deutetrabenazine is a deuterated form of tetrabenazine. Tetrabenazine was first used in the 1950s as a treatment for psychosis and in 1979 was approved in the United Kingdom for the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorders. In the United States, it was approved in 2008 as a treatment for chorea in patients with HD based on the results of the 12‐week TETRA‐HD study, which showed that tetrabenazine significantly reduced chorea severity in tetrabenazine‐treated patients compared with placebo‐treated patients, although adverse events (AEs) included increased suicidal ideation and depression. 6 In an 80‐week open‐label extension study, tetrabenazine continued to show improved chorea scores; however, somnolence, depression, akathisia, and parkinsonism were reported as tetrabenazine‐related AEs. 2 Because of these side effects, dose limitations were implemented to improve tolerability, thus affecting treatment efforts in patients with chorea and TD. In addition to these AEs, tetrabenazine has to be administered frequently, three times a day, to maintain efficacy. Deutetrabenazine, as a deuterated form of tetrabenazine, was developed to advance treatment efforts by improving the tolerability profile and reducing the need for frequency dosing. 7

The process of deuteration involves replacing a hydrogen atom of a compound with deuterium (a naturally occurring isotope of hydrogen, sometimes called hydrogen 2). 8 The deuterium bond is known to be stronger than the hydrogen bond in synthetic reactions, termed the kinetic isotope effect, thereby leading to differences in the pharmacokinetics of the compound. 9 In deutetrabenazine, 2 O‐linked methyl groups (O‐CH3) of the tetrabenazine molecule have been replaced by 2 trideuteromethyl groups (O‐CD3). The rapid conversion of tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine by carbonyl reductase to their respective nondeuterated and deuterated metabolites, α‐dihydrotetrabenazine (α‐HTBZ) and β‐dihydrotetrabenazine (β‐HTBZ), proceeds similarly, and the plasma concentrations of both tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine are near the limit of detection. Thus, tetrabenazine and deutetrabenazine are similar to a prodrug, as the α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ metabolites are primarily responsible for the intended pharmacological activity and are considered the active moieties. The metabolites act as reversible high‐affinity inhibitors of monoamine uptake into vesicles of presynaptic neurons by binding selectively to the VMAT2. 10 In vitro binding studies confirmed that Ki values are within 0.04 log units of those of their corresponding nondeuterated forms. 11 The α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ metabolites of tetrabenazine are mainly metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6. 12 The substitution of the O‐CD3 groups attenuates the metabolism of deuterated α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ by CYP2D6 relative to nondeuterated α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ. 13

These results suggest that after oral administration of deutetrabenazine, the deuterated forms of the pharmacologically active α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ will have greater exposure and half‐lives relative to their nondeuterated forms. Single‐dose studies comparing deutetrabenazine (25 mg) with tetrabenazine (25 mg) in healthy volunteers evaluated the impact of deuteration on pharmacokinetics of the individual active metabolites α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ and total active (α+β)‐HTBZ metabolites’ safety and metabolite profile. These studies demonstrated that the specific deuteration in deutetrabenazine results in an improved pharmacokinetic profile with a 2‐fold increase in overall exposure and a marginal increase in mean peak plasma concentration, no novel plasma and urinary metabolites, and an increased ratio of active‐to‐inactive metabolites, attributes that provide benefits to patients. 13

The studies described here evaluated the pharmacokinetics and safety of different doses of the deutetrabenazine tablet in its commercial formulation, compared with commercial tetrabenazine tablets following single‐ and repeated‐dose administration. The effect of food on exposure was also evaluated.

Methods

Ethics

The final protocol and informed consent documents were approved by the investigational sites for both studies. Subjects received and signed a copy of the informed consent form that summarized in nontechnical terms the purpose of the study, the study procedures, and potential hazards. The first study (study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07) was conducted by Q Pharm Pty Ltd in Brisbane (Queensland, Australia), and all study documents were reviewed by the Queensland Institute of Medical Research (Queensland Australia). The second study (study SD‐809‐C‐11) was conducted by Celerion in Tempe, Arizona, and all study documents were approved by Chesapeake Research Review, Inc. (Columbia, Maryland). The protocols of both studies were designed by Auspex Pharmaceuticals (La Jolla, California), which was acquired by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd (Petah Tikva, Israel). The studies were performed in accordance with the Therapeutic Goods Administration Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95, adopted in July 2000), the ethical rules contained in the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007), and the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) including subsequent revisions.

Study Participants

Both studies recruited healthy male and female volunteers aged 18 to 50 years who were in good general health, with a CYP2D6 extensive‐ or intermediate‐metabolizer phenotype and a body mass index within ≥18 and ≤27 and ≥18 and ≤30 kg/m2 for the first and second studies, respectively. Key exclusion criteria included CYP2D6 poor‐ or ultrarapid‐metabolizer phenotype, pregnancy, history or presence of malignancy, psychiatric condition, or evidence of clinically relevant medical illness.

Study Design

Study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 was a single‐center, open‐label, 2‐part, single‐ and repeated‐dose investigation in healthy volunteers. In the first part of the study, single oral doses of a commercially available tetrabenazine 25‐mg tablet in a fasted state and single 15‐mg oral tablets of 2 deutetrabenazine formulations in fed and fasted states were administered to 25 subjects in a randomized treatment sequence across 5 dosing periods lasting 17 days from start of dosing to study termination (Figure S1a). For the fasted state, subjects were administered either tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine in the morning following an overnight fast of 10 or more hours. For the fed state, subjects were administered deutetrabenazine in the morning following a meal, which conformed to the high‐fat meal definition in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on Food‐Effect Bioavailability and Fed Bioequivalence Studies. 14 During each period, subjects received a single dose of either tetrabenazine 25 mg or 1 of the deutetrabenazine formulations on day 1 of the study period, and pharmacokinetic sampling and safety assessments were conducted for 72 hours postdose. Subjects remained in the clinic during the entire 17‐day study. Subjects participating in the first part of the study were not eligible to participate in the second part.

In the second part of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, subjects received either commercially available tetrabenazine or the tablet formulation of deutetrabenazine from part 1 of the study that was selected for further development. Subjects were divided into 2 groups of 12 subjects; each subject received 2 single‐dose regimens and 2 repeated‐dose regimens (every 12 hours) over a 20‐day period, which included administrations of 3 doses of deutetrabenazine (7.5, 15, and 22.5 mg) in the fed state, compared with single and repeated doses of tetrabenazine (25 mg) in a fasted state (Figure S1b). Dosing in the second group was delayed by at least 7 days after dosing in the first group to allow tolerability of deutetrabenazine to be evaluated at the lower doses before proceeding to the higher doses. In the fed state, subjects were given 1 of the standard test meals, which were consistent in calorie count and nutritional content and were designed to test conditions close to that after intake of a regular conventional meal.

On days 1 and 4, subjects received a single dose of study drug separated by at least 72 hours, during which blood samples for pharmacokinetic profiling were collected. On day 7, subjects began a 3.5‐day repeated‐dosing regimen of the first dose. Trough blood samples for steady‐state assessment were collected predose on days 7‐10. Blood samples for pharmacokinetic profiling were collected over 72 hours commencing on day 10 and ending on day 13. Urine samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were collected for 12 hours postdose on day 10. On day 13, after a 72‐hour washout and pharmacokinetic sampling, subjects began a 4.5‐day ascending repeated‐dose regimen of study drug up to the second target dose. Trough blood samples were again collected predose on days 13‐17. In addition, blood samples for pharmacokinetic profiling were collected over 72 hours commencing on day 17 and ending on day 20. Urine samples for pharmacokinetic analysis were collected for 12 hours postdose on day 17. On the pharmacokinetic profile days, subjects were administered deutetrabenazine within 30 minutes after consuming a standard test meal. The standard meals had the same fat, protein, caloric, and nutritional content but not necessarily the same food composition. For the twice‐daily dosing of deutetrabenazine on nonpharmacokinetic profile days, dosing was administered twice per day separated by 12 hours and within 30 minutes of consuming a standard meal. Tetrabenazine in the second group was administered as a single dose in the fasted state on pharmacokinetic profile days or as a twice‐daily dosing on nonpharmacokinetic profile days with the first dose administered in the morning in the fasted state (10 hours fasted) and the second dose administered in the afternoon in an “empty stomach” fasted state (2 hours fasted). Each group remained confined for 20 nights in the clinic for treatment, safety monitoring, and pharmacokinetic sample collection.

Study SD‐809‐C‐11 was an open‐label 5‐way crossover study in 32 healthy volunteers to evaluate the relative bioavailability of 4 dose levels of deutetrabenazine in the commercial formulation (Figure S1c). Based on the results of study‐SD‐809‐C‐7, tablet strengths of 6, 12, and 18 mg of deutetrabenazine were subsequently manufactured for use in study SD‐809‐C‐11. The treatment, which was administered in a random sequence, included single oral doses of 6, 12, 18, and 24 mg (18‐ + 6‐mg tablet) following a standard meal and a single dose of 18 mg following a high‐fat meal. A 5‐day washout period separated each treatment period. The standard meal had a composition that was intermediary between the low‐fat and high‐fat meals recommended in FDA guidance and consisted of 600‐800 calories, with 35% of total calories from fat, 45% to 65% from carbohydrates, and 10% to 35% from protein. The high‐fat meal conformed to the definition in the FDA guidance. 14 Blood samples were collected predose and at multiple points over 72 hours following dosing during each treatment period for determination of plasma concentrations of deutetrabenazine and metabolites.

Safety

Safety assessments consisting of AE monitoring, physical examination, vital sign assessment, standard 12‐lead electrocardiograms (ECGs), psychometric scales (Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale), and laboratory testing were conducted multiple times throughout both studies. Triplicate 12‐lead digital ECGs were collected to perform preliminary assessment of cardiac repolarization (QTc) on dosing days 1 and 4 of part 2 in AUS‐SD‐CTP‐07.

Quantification of Drug and Metabolite Concentrations in Plasma

The validated bioanalytical methods employed to quantify deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine and metabolite concentrations in these studies are similar to those described previously. 13 Briefly, the plasma concentrations of the parent drugs and their respective metabolites were determined by liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry analysis performed on a Sciex API 4000 mass spectrometer interfaced to an Accela high‐pressure liquid chromatography system fitted with a Gemini‐NX C18 reverse‐phase column and a gradient mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile/100 mM ammonium acetate (pH 8.0). Analytes were quantified using selected reaction monitoring procedures in which the precursor ions in all cases were the 12C‐containing protonated molecular ion species (MH+); for unlabeled molecules, these were at m/z 318 (tetrabenazine), m/z 320 (HTBZ), m/z 306 (O‐desmethyl‐HTBZ), m/z 334 (monohydroxy tetrabenazine), and m/z 350 (2‐ methylpropanoic acid‐β‐HTBZ). Product ions monitored (from both unlabeled and deuterated compounds) corresponded to those formed by the following neutral losses from their respective MH+ precursors: tetrabenazine‐C6H10O (98 Da), α/β‐HTBZ and O‐desmethyl α/β‐HTBZ‐C2H6O (46 Da), monohydroxy tetrabenazine‐C2H4O2 (60 Da), and 2‐methylpropanoic acid‐β‐HTBZ‐C3H8O3 (92 Da). The corresponding deuterium‐labeled compounds were used as internal standards for the quantification of unlabeled analytes and vice versa for the measurement of the deuterated analytes. The mean interrun precision for the analytes was 2.5% and 14.0% and the intraassay precision was between 0.9% and 8.0%; see Table S1 for the individual analytes. For the unlabeled and deuterated analytes, the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for the parent drug was 0.100 ng/mL and 0.500 ng/mL for all metabolites. Plasma concentrations below the LLOQ at initial and trailing measurement points were set to zero for summary statistics and were excluded from calculations of geometric means. For analytes with concentrations below the LLOQ followed by measurable concentrations at intermediate times, the plasma concentration was set to the LLOQ of the assay.

Pharmacokinetic Analyses

For the deuterated and nondeuterated forms of the active metabolites, α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ, the sum total of α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ (total [α+β]‐HTBZ) and their O‐desmethyl metabolites, the following pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated, as appropriate, using standard noncompartmental methods by Phoenix WinNonlin version 6.3 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, California): AUC0‐t, AUCinf, %AUCextrap Rac, Cmax, Tmax, Cmin, tmin, λz, t1/2, and AUC0‐12.. The accumulation ratio, Rac, was calculated as AUC0‐12 at steady state divided by AUC0‐12 following a single dose where 12 hours is the length of the dose interval used for multiple dosing. Visual inspections of trough concentrations following repeated administration of deutetrabenazine were conducted to confirm that steady state was achieved.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive summary statistics were performed for all pharmacokinetic parameters including arithmetic mean, geometric mean (for Cmax, AUC0‐t, AUCinf, and derived parameters), range, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation.

Sample Size Calculations

For study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, the sample size of 24 subjects in part 1 was selected to provide > 90% power to demonstrate no food effect (ie, that the 90% confidence interval for the geometric mean ratio to be contained within the 80%‐125% limits) for an assumed within‐subject standard deviation (log‐transformed scale) of 0.217, and the sample size of 24 subjects in part 2 was selected based on pharmacokinetic practice. In study SD‐809‐C‐11, the sample size of 26 completed subjects was estimated to provide 90% power to demonstrate bioequivalence (the 2‐sided 90%CI for the geometric mean ratio lies within the interval of 80%‐125%) for an assumed within‐subject standard deviation (log‐transformed scale) of 0.235. This sample size estimation for both studies considered the data from earlier studies available at the time of protocol preparation.

Comparative Bioavailability

In study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, the comparative bioavailability of the deutetrabenazine formulation relative to tetrabenazine (reference treatment) and the effect of high‐fat meal versus fasting for the deutetrabenazine formulation were assessed for Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf of deuterated and nondeuterated α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ, and deuterated and nondeuterated total (α+β)‐HTBZ using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with subject, period (part 1 only), and treatment as the classification variables and the natural logarithms of these parameters as the dependent variable. Confidence intervals (90%) were constructed for the geometric mean ratios of the Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf for the individual α‐ and β‐HTBZ metabolites and the total (α+β)‐HTBZ using the log‐transformed data and a 1‐sided t test.

In study SD‐809‐C‐11, the comparative bioavailability of multiple doses (6, 12, 18, and 24 mg) of deutetrabenazine to 25 mg tetrabenazine was assessed for Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf of the deuterated and nondeuterated forms of α‐HTBZ, β‐HTBZ, and total (α+β)‐HTBZ, using an ANOVA model with subject and treatment as the classification variables and the natural logarithm of the parameters as the dependent variable. The effect of food was assessed in a similar manner by comparing deutetrabenazine 18 mg following a standard meal to deutetrabenazine 18 mg following a high‐fat meal. Confidence intervals (90%) were constructed for the geometric mean ratios using a 1‐sided t‐test procedure. The point estimates and confidence limits were transformed back to the original scale.

Dose Proportionality

Dose proportionality for deutetrabenazine tablets was evaluated in both studies using power regression (parameter = α × dosebeta) and linear regression (parameter = β × dose). In addition, in the second part of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, dose proportionality was estimated by the back‐transformed least‐squares means and corresponding 95% confidence intervals of the AUC0‐t and AUCinf following the different doses and administration regimens of deutetrabenazine. The analyses were repeated using dose‐normalized (parameter divided by administered dose) values of AUC and Cmax to test for possible deviations from dose proportionality. Similarly, in study SD‐809‐C‐11, the dose proportionality of deutetrabenazine when administered with a standard meal was investigated by assessing the relative bioavailability of the dose‐normalized pharmacokinetic parameters of the metabolites at 4 doses (6, 12, 18, and 24 mg).

Results

Subject Disposition and Demographics

In study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 1, 25 subjects were enrolled and received treatment and were included in the safety population. Twenty‐four subjects completed the study as planned and were included in the per‐protocol pharmacokinetic analysis set. Subjects who were in part 1 of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 were not eligible to be in part 2. In part 2 of the study, 24 subjects were enrolled and received treatment and were included in the safety population and the per‐protocol analysis set. Mean ± SD age of participants in parts 1 and 2 was 26.4 ± 6.5 and 25.1 ± 5.1 years; 28% and 29%, respectively, were female; and 92% and 87%, respectively, were white. The reasons for study discontinuation included withdrawal of consent because of difficulty with venous access, problems with additional confinement, and personal reasons.

In study SD‐809‐C‐11, 32 participants enrolled in the study and had a mean ± SD age of 34.1 ± 7.4 years; 53% were female; and 94% were white. Two participants discontinued early, 1 because of withdrawal of consent and 1 because of an AE. The subject who discontinued because of an AE was a 36‐year‐old woman who experienced syncope while orthostatic vital signs were being assessed prior to a deutetrabenazine dosing and ≈5 days after a previous deutetrabenazine dose. The AE was moderate in severity, and the primary investigator did not believe that it was related to study medication, as the plasma concentrations of deutetrabenazine and active metabolites were below the LLOQ by 24 hours after the previous dose.

Safety

In study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, single administration of deutetrabenazine 15 mg in part 1 (both formulations) and single‐dose and repeated administration of deutetrabenazine doses 7.5‐22.5 mg in part 2 (selected commercial formulation) were well tolerated, and the AE profiles were similar. Somnolence and headache were the most frequent AEs reported as possibly drug related. One serious AE of vessel puncture‐site reaction at the site for pharmacokinetic and laboratory blood draw occurred after a single dose of tetrabenazine; the event resolved without sequelae and was not considered study drug related. No serious AEs were reported following deutetrabenazine administration. There were no clinically significant abnormalities in laboratory parameters, vital signs, and physical examination following administration of either single or multiple doses of deutetrabenazine or tetrabenazine. No subject had a postdose QTc > 450 milliseconds or a change from predose in QTc of >30 milliseconds following administration of either tetrabenazine or deutetrabenazine.

In study SD‐809‐C‐11, treatments were generally well tolerated; a total of 10 subjects (31%) reported 25 AEs, all of which were mild to moderate in severity. No serious AEs were reported, and there was no evidence of a dose‐response in the incidence of AEs. All AEs resolved without sequelae. No safety concerns were observed regarding clinical laboratory tests, physical examinations, ECGs, and psychometric assessments. No dose‐response was observed with regard to either the overall incidence of AEs or individual AEs.

Pharmacokinetic Evaluations

Relative Pharmacokinetics of Deutetrabenazine Tablets to Tetrabenazine

In part 1 of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07, 2 formulations of deutetrabenazine were administered, one that was further studied in part 2 and subsequently became the commercial formulation, and the other that was discontinued from further evaluation. The pharmacokinetic results from part 1 described here compare the pharmacokinetics for the formulation selected for further development with tetrabenazine; the results for the discontinued formulation are not presented.

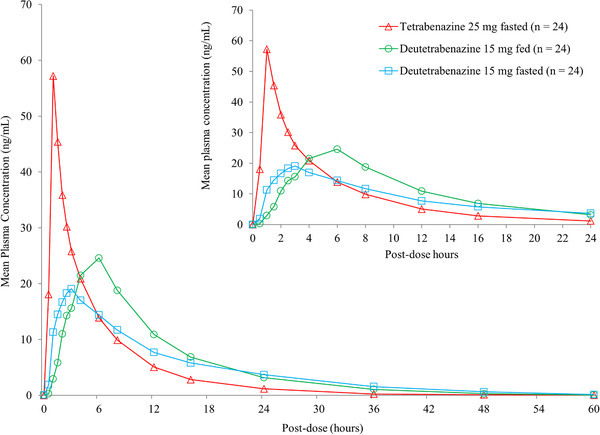

The plasma concentrations of the parent compounds were near or at the LLOQ and transient following single administration of 15‐mg deutetrabenazine and 25‐mg tetrabenazine tablets. Because of the small number of samples with quantifiable levels, pharmacokinetic parameters could not be reliably estimated for either deutetrabenazine or tetrabenazine. For the active metabolites, the corresponding mean concentration‐time profiles for total (α+β)‐HTBZ following single administration of deutetrabenazine 15 mg in the fed or fasted state and tetrabenazine 25 mg in the fasted state are displayed in Figure 1. A summary of the mean pharmacokinetic parameters and the relative bioavailability of the individual active metabolites α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ and of total (α+β)‐HTBZ following 15 mg deutetrabenazine in fasted and fed states compared with 25 mg tetrabenazine in the fasted state are presented in Table 1. These data show that the total exposure (AUCinf) to the total (α+β)‐HTBZ was slightly higher after a single dose of a 15‐mg deutetrabenazine tablet in both fasted and fed states compared with 25‐mg tetrabenazine tablets, and in contrast, the maximal concentration (Cmax) was substantially lower following deutetrabenazine.

Figure 1.

Mean plasma concentrations of total (α+β)‐HTBZ following single‐dose administration of deutetrabenazine 15 mg in the fed or fasted state compared with tetrabenazine 25 mg in the fasted state. Data are arithmetic means of plasma concentrations from study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 1 and depicted for the first 24 hours in the upper figure and for 60 hours in the lower figure.

Table 1.

Summary of Pharmacokinetic Parameters for the Active HTBZ Metabolites and Their Relative Bioavailability Following Treatment With Deutetrabenazine 15 mg in Fed and Fasted States Compared With Tetrabenazine 25 mg Fasted

| Tetrabenazine 25 mg Fasted | Deutetrabenazine 15 mg Fed | Deutetrabenazine 15 mg Fasted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (CV%) | Mean (CV%) | % Ratio (90%CI) a | Mean (CV%) | % Ratio (90%CI) a | ||

| α‐HTBZ | Cmax, ng/mL | 42.4 (29) | 20.8 (27) | 49.3 (44.5‐54.7) | 14.2(34) | 32.2 (28.5‐38.8) |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 172 (54) | 207 (30) | 128.2 (115.8‐138.4) | 185 (25) | 116.1 (105.7‐127.5) | |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 179 (53) | 217 (29) | 129.7 (118.1‐142.5) | 196 (24) | 118.7 (108.1‐130.3) | |

| T1/2, h | 5.1 (47) | 7.7 (21) | nc | 10.3 (23) | nc | |

| Tmax, h b | 1.0 (0.5‐2.0) | 6.0 (1.0‐8.0) | nc | 2.5 (1.0‐8.0) | nc | |

| β‐HTBZ | Cmax, ng/mL | 22.9 (46) | 12.7 (50) | 55.3 (47.7‐64.2) | 8.43 (48) | 36.8 (31.1‐43.5) |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 77.2 (109) | 85.6 (102) | 117.0 (104.5‐131.1) | 74.2 (108) | 99.6 (91.6‐108.2) | |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 80.7 (107) | 102 (92) | 119.9 (105.5‐136.2) | 81.4 (105) | 104.7 (96.6‐113.5) | |

| T1/2, h | 3.0 (56) | 4.6 (63) | nc | 6.6 (56) | nc | |

| Tmax, h b | 1.0 (0.5‐2.0) | 6.0 (1.5‐8.0) | nc | 2.5 (1.0‐8.0) | nc | |

| Total (α+β)‐HTBZ | Cmax, ng/mL | 65.1 (33) | 33.3 (33) | 51.4 (46.0‐57.4) | 22.5 (36) | 34.4 (29.3‐40.2) |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 251 (69) | 296 (48) | 126.6 (115.8‐138.4) | 263 (45) | 113.5 (104.7‐123.0) | |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 257 (69) | 305 (46) | 127.7 (116.7‐139.6) | 273 (45) | 115.4 (106.4‐125.2) | |

| T1/2, h | 4.5 (57) | 7.0 (23) | nc | 9.4 (25) | nc | |

| Tmax, h b | 1.0 (0.5‐2.0) | 6.0 (1.5‐8.0) | nc | 2.3 (1.0‐8.0) | nc | |

CV, coefficient of variation; HTBZ, dihydrotetrabenazine; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; AUC0‐t, area under the concentration‐time curve from time 0 to the last quantifiable concentration; AUCinf, area under the plasma concentration‐versus‐time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; Tmax, time of maximum observed plasma concentration; nc, not calculated.

Data are from part 1 of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07.

Percent ratio of least‐squares geometric means of test treatment (deutetrabenazine 15 mg fed or deutetrabenazine 15 mg fasted)/reference treatment (tetrabenazine 25 mg fasted).

Median.

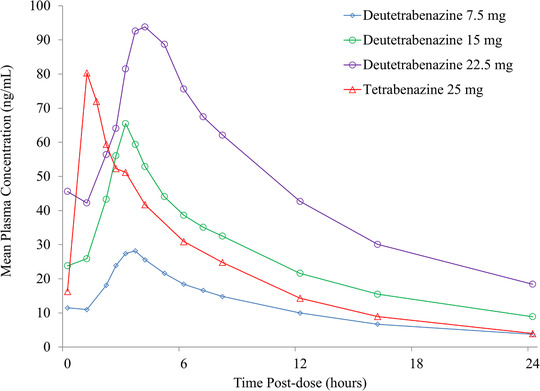

Mean concentration‐time profiles for total (α+β)‐HTBZ after repeated doses in steady state are displayed in Figure 2. The mean pharmacokinetic parameters for the individual metabolites α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ and total (α+β)‐HTBZ in the second part of study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 are listed in Table 2. The half‐lives for the deuterated metabolites, α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ, and consequently total (α+β)‐HTBZ following both single and repeated administration of all deutetrabenazine doses were longer than the corresponding half‐lives of the nondeuterated metabolites following tetrabenazine administration. The median Tmax of HTBZ metabolites was later postdose for both single and repeated administration of deutetrabenazine doses compared with tetrabenazine. Visual examination of the trough plasma metabolite concentrations following repeated dosing on days 7‐10 and days 13‐17 confirmed that steady state was achieved by day 10 and day 17 for both groups (shown in Figure S2). In steady state, the peak‐to‐trough fluctuation (as indicated by the Cmax/Cmin ratio) for total (α+β)‐HTBZ of deutetrabenazine at all doses was lower than that observed for the corresponding analytes of tetrabenazine at 25 mg twice a day.

Figure 2.

Steady‐state mean plasma concentrations of total (α+β)‐HTBZ following repeated administration of 3 doses of deutetrabenazine (7.5, 15, and 22.5 mg) in the fed state compared with repeated doses of tetrabenazine 25 mg in the fasted state. Data are arithmetic means of plasma concentrations from study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 2. Steady state following repeated doses was confirmed with visual assessment of predose trough plasma concentrations on days 9 and 10 and days 16 and 17.

Table 2.

Mean (CV%) Pharmacokinetic Parameters for the Active HTBZ Metabolites After Single Doses and After Repeated (Twice‐Daily) Dosing to Steady State With Tetrabenazine or Deutetrabenazine Tablets

| Mean (CV%) | Tetrabenazine 25 mg Fasted a (n = 12) | Deutetrabenazine 7.5 mg Fed a (n = 12) | Deutetrabenazine 15 mg Fed a (n = 12) | Deutetrabenazine 22.5 mg Fed a (n = 12) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α‐HTBZ | Single Dose | Steady State | Single Dose | Steady State | Single Dose | Steady State | Single Dose | Steady State |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 35.1 (33) | 60.3 (24) | 13.1 (27) | 20.2 (22) | 27.2 (15) | 46.0 (17) | 40.0 (20) | 67.7 (35) |

| Tmax, h b | 1.0 (0.5‐2.5) | 1.0 (0.5‐3.0) | 3.0 (2.5‐5.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐4.0) | 3.0 (2.5‐5.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐3.0) | 3.8 (3.0‐5.0) | 4.0 (2.5‐5.0) |

| AUC c , ng·h/mL | 224 (55) | 280 (46) | 125 (32) | 136 (29) | 278 (32) | 301 (25) | 415 (32) | 484 (31) |

| T1/2, h | 6.5 (33) | 7.0 (31) | 8.1 (21) | 10.0 (28) | 9.0 (24) | 9.9 (24) | 9.1 (25) | 10.3 (24) |

| Cmin, d ng/mL | nc | 10.1 (77) | nc | 7.2 (41) | nc | 15.6 (37) | nc | 26.3 (40) |

| Cmax/Cmin | nc | 8.7 (57) | nc | 3.0 (26) | nc | 3.2 (29) | nc | 2.6 (14) |

| β‐HTBZ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax, ng/mL | 20.5 (57) | 35.0 (42) | 8.34 (43) | 11.6 (37) | 18.6 (27) | 26.3 (28) | 27.5 (35) | 42.9 (56) |

| Tmax, h b | 1.25 (0.5‐2.5) | 1.0 (1.0‐3.0) | 3.01 (2.5‐5.0) | 3.50 (2.5‐4.0) | 3.26 (2.5‐4.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐3.5) | 3.75 (3.0‐5.0) | 4.0 (2.5‐5.0) |

| AUC, c ng·h/mL | 99.4 (99) | 136 (81) | 53.9 (59) | 67.0 (48) | 135 (49) | 142 (37) | 198 (85) | 285 (75) |

| T1/2, h | 3.4 (32) | 3.9 (44) | 5.2 (45) | 5.7 (38) | 5.7 (28) | 6.0 (24) | 4.9 (50) | 6.5 (43) |

| Cmin, ng/mL | nc | 3.3 (131) | nc | 2.8 (71) | nc | 5.5 (54) | nc | 13.1 (102) |

| Cmax/Cmin | nc | 21.4 (61) | nc | 5.2 (56) | nc | 6.0 (51) | nc | 4.5 (35) |

| (α+β)‐HTBZ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax, ng/mL | 55.5 (39) | 94.9 (31) | 21.4 (32) | 31.5 (26) | 45.3 (18) | 72.0 (20) | 67.5 (25) | 111 (43) |

| Tmax, h b | 1.25 (0.5‐2.5) | 1.0 (1.0‐3.0) | 3.0 (2.5‐5.0) | 3.25 (2.5‐4.0) | 3.3 (2.5‐4.0) | 3.0 (2.0‐3.5) | 3.8 (3.0‐5.0) | 4.0 (2.5‐5.0) |

| AUC c , ng·h/mL | 320 (69) | 416 (57) | 176 (39) | 203 (34) | 408 (36) | 443 (28) | 610 (48) | 769 (46) |

| T1/2, h | 5.6 (34) | 6.3 (31) | 7.2 (19) | 8.8 (22) | 7.7 (18) | 9.1 (28) | 8.4 (26) | 9.5 (24) |

| Cmin, ng/mL | nc | 13.4 (89) | nc | 10.1 (48) | nc | 21.1 (41) | nc | 39.5 (59) |

| Cmax/Cmin | nc | 10.8 (58) | nc | 3.50 (31) | nc | 3.8 (30) | nc | 3.0 (19) |

CV, coefficient of variation; HTBZ, dihydrotetrabenazine; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; Tmax, time of maximum observed plasma concentration; AUC0‐12, area under concentration‐time curve from time 0 to 12 hours postdose; AUCinf, area under the plasma concentration‐versus‐time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity; Cmin, minimum blood plasma concentration; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; nc, not calculated.

Data are from study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 2.

Deutetrabenazine was administered twice a day after a standard meal, and tetrabenazine was administered twice a day in a fasted state. Steady state following repeated doses was confirmed with visual assessment of the trough plasma concentrations on days 9 and 10 and days 16 and 17 (shown in Figure S2).

Median (min‐max range).

AUCinf for single dose administration and AUC0‐12 for steady‐state administration.

Minimum concentration between 0 and 12 hours post administration of either deutetrabenazine or tetrabenazine.

Consistent with what has been reported previously, 13 exposure to the 9‐ and 10‐O‐desmethyl metabolites was less following repeated dosing of deutetrabenazine 15 mg in a fed state compared with tetrabenazine 25 mg in a fasted state (Table S2). The concentrations of deuterated 10‐O‐desmethyl‐α‐HTBZ and 10‐O‐desmethyl‐β‐HTBZ metabolites were below the LLOQ for deutetrabenazine 15 mg, whereas they were measurable for tetrabenazine 25 mg.

Accumulation and Dose Proportionality

In study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 2, following multiple doses of either deutetrabenazine or tetrabenazine twice a day, accumulation was observed for α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ in the range of ≈1.4‐ to 1.8‐fold for Cmax and ≈1.6‐ to 2‐fold for AUC. The ratios of parameters AUC0‐12 at steady state compared with a single dose were similar for HTBZ metabolites of deutetrabenazine as for tetrabenazine, indicating that there were no appreciable differences in the extent of accumulation for the corresponding analytes.

Dose linearity was assessed by comparing dose‐normalized exposure between dose levels of deutetrabenazine and by regression models fitted to AUCinf for a single dose, to AUC0‐12 at steady state, and to Cmax for both a single dose and steady state. The point estimates for the ratios were all close to 1 for the comparison of the 15‐ and 22.5‐mg dose groups; however, point estimates for the comparisons of the lowest dose, 7.5 mg, with both 15 and 22.5 mg were all > 1, with marked deviations observed, especially for Cmax and AUC of β‐HTBZ (data not shown). Because the 90% confidence intervals for all the dose‐normalized exposure comparisons contained 100%, a significant deviation from dose proportionality was not concluded. Using a power regression model, the estimates of the exponents of dose for each of Cmax and AUC were slightly > 1 although these differences were not statistically significant. Using linear regression, the r² value was at least 85% for each of these parameters, indicating that linear dose dependence was able to explain most of the variation across dose levels for these parameters. All 3 approaches were in agreement that increases in the exposure parameters of α‐HTBZ, β‐HTBZ, and (α+β)‐HTBZ are approximately linear with dose.

Estimates from the power regression model of single‐dose exposure AUCinf and steady‐state AUC0‐12 were then used to determine the dose of deutetrabenazine in the fed state that provided an exposure of total (α+β)‐HTBZ equivalent to that from tetrabenazine 25 mg in the fasted state. The power regression model estimated the equivalent deutetrabenazine doses at single dose and steady state to be 11.4 and 13.2 mg, respectively; similar results were shown for the linear regression model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimation of Deutetrabenazine Dose Providing Exposure Similar to Tetrabenazine 25 mg for Total (α+β)‐HTBZ

| Power Regression Model Parameter = α × doseβ, Determined From Linear Regression Model: log(parameter) = log(dose) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α | β | Tetrabenazine 25 mg Geometric Mean | Estimate of Comparable Dose of Deutetrabenazine (mg) | |

| AUCinf (single dose) | 17.0 | 1.1 | 267 | 11.4 |

| AUC0‐12 (steady state) | 17.8 | 1.2 | 370 | 13.2 |

| Linear Regression Model Parameter = β × dose, Zero Intercept Determined From Linear Regression Model: parameter = dose/no intercept | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (Zero Intercept) | Tetrabenazine 25 mg Mean | Estimate of Comparable Dose of Deutetrabenazine (mg) | |

| AUCinf (single dose) | 26.9 | 320 | 11.9 |

| AUC0‐12 (steady state) | 32.4 | 416 | 12.8 |

HTBZ, dihydrotetrabenazine; AUCinf, area under plasma concentration‐versus‐time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity; AUC0‐12, area under concentration‐time curve from time 0 to 12 hours postdose.

Data are from study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07.

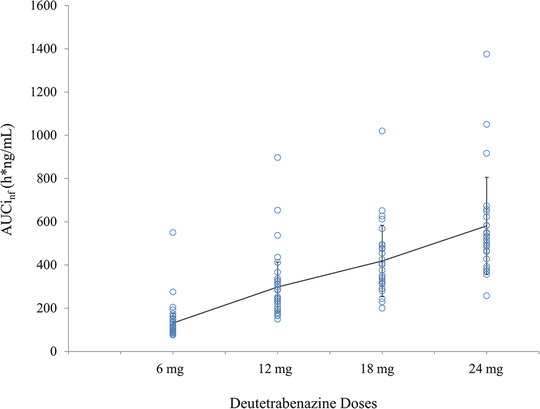

In study SD‐809‐C‐11, the exposure of deuterated total (α+β)‐HTBZ metabolites appeared to increase in a dose‐dependent manner for doses of deutetrabenazine (6, 12, 18, and 24 mg) administered with a standard meal, as illustrated in Table 4. The dose dependence of AUCinf of total (α+β)‐HTBZ is displayed graphically in Figure 3 as a scattergraph of individual subject values at each dose level. Linear dose dependence of AUCinf of total (α+β)‐HTBZ was again supported by linear analysis and power regression analyses.

Table 4.

Dose‐Normalized Pharmacokinetic Parameters for the Active HTBZ Metabolites After Single Doses of Deutetrabenazine

| Deutetrabenazine Doses Following a Standard Meal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 mg | 12 mg | 18 mg | 24 mg | |

| LS Means (n = 30) | Deuterated α‐HTBZ | |||

| Cmax, ng/mL | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 14.5 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 16.2 |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 16.3 | 17.0 | 16.4 | 16.7 |

| Deuterated β‐HTBZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax, ng/mL | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 4.1 | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.7 |

| AUCinf. ng·h/mL | 4.8 | 5.6 | 5.47 | 6.0 |

| Deuterated Total (α+β)‐HTBZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax, ng/mL | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 19.1 | 21.7 | 21.2 | 22.3 |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 20.8 | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.7 |

Dose normalized, parameter value divided by dose value; LS mean, least‐squares mean; HTBZ, dihydrotetrabenazine; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; AUC0‐t, area under concentration‐time curve from time 0 to last quantifiable concentration; AUCinf, area under plasma concentration‐versus‐time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity.

Data are from study SD‐809‐C‐11.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of the exposure (AUCinf)‐versus‐dose relationship for total (α+β)‐HTBZ. Data are from study SD‐809‐C‐11. The dose dependence of AUCinf of total (α+β)‐HTBZ is displayed as the individual values with a line of the means (standard deviations) plotted across the doses. Dose linearity was confirmed in a linear model (r 2 = 0.87) and a power regression analysis (AUCinf = 18.12 × dose 1 .07; 95%CI, 0.95‐1.19; P = .232) over the dose range studied (6‐24 mg).

Food Effect on Pharmacokinetics

The effects of food on the rate and extent of absorption of deutetrabenazine tablets were assessed first in study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 1 by comparing the administration of deutetrabenazine 15 mg in a fasted state versus following a high‐fat meal. Food increased the Cmax of the individual metabolites, α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ, and total (α+β)‐HTBZ by about 50% compared with the fasted state (data for total [α+β]‐HTBZ is shown in Table 5). AUC0‐t and AUCinf were only slightly increased for all individual and total active metabolites, with an increase of about 11% for the AUCinf of (α+β)‐HTBZ. For total (α+β)‐HTBZ, the apparent terminal half‐life was 9.1 hours compared with 6.8 hours for the fasted versus fed state. The Tmax for the α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ metabolites occurred later after administration in the fed state (median, 6.0 hours) compared with administration in the fasted state (median, 2.5 hours).

Table 5.

Comparison of Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Total (α+β)‐HTBZ for Deutetrabenazine Administration Following High‐Fat/High‐Calorie Meals, Standard Meals, or in a Fasted State

| Total (α+β)‐HTBZ LS Means | Deutetrabenazine 15 mg Following High‐Fat/High‐Calorie Meal Versus Fasted a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deutetrabenazine 15 mg High‐Fat/High‐Calorie Meal | Deutetrabenazine 15 mg Fasted | % Ratio c | 95%CI | |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 31.7 | 21.2 | 149.7 | (126.0‐177.8) |

| AUC0‐t, h × ng/mL | 272.8 | 244.6 | 111.5 | (104.6‐118.9) |

| AUCinf, ng × h/mL | 282.0 | 254.9 | 110.6 | (104.0‐117.7) |

| T1/2, h | 6.8 | 9.1 | 75.3 | (70.7‐80.3) |

| Total (α+β)‐HTBZ LS Means | Deutetrabenazine 18 mg Following High‐Fat/High‐Calorie Meal Versus Standard Meal b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deutetrabenazine 18 mg High‐Fat/High‐Calorie Meal | Deutetrabenazine 18 mg Standard Meal | % Ratio c | 95%CI | |

| Cmax, ng/mL | 48.4 | 46.5 | 104.2 | (97.3‐111.6) |

| AUC0‐t, ng·h/mL | 408 | 382 | 107.0 | (101.4‐112.9) |

| AUCinf, ng·h/mL | 419 | 394 | 106.4 | (100.9‐112.2) |

| T1/2, h | 9.9 | 9.7 | 101.8 | (95.9‐108.1) |

HTBZ, dihydrotetrabenazine; LS mean, least‐squares mean; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; AUC0‐t, area under the concentration‐time curve from time 0 to the last quantifiable concentration; AUCinf, area under plasma concentration‐versus‐time curve from time 0 extrapolated to infinity; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; nc, not calculated.

From study AUS‐SD‐809‐CTP‐07 part 1, in which subjects were administered deutetrabenazine 15 mg following a high‐fat (50% total calories) and high‐calorie (800‐1000 calories) test meal. For the fasted state, subjects were administered deutetrabenazine 15 mg in the morning following an overnight fast of at least 10 hours.

From study SD‐809‐C‐11, in which subjects were administered deutetrabenazine 18 mg following a high‐fat (50% total calories) and high‐calorie (800‐1000 calories) or following a standard meal (35% of calories from fat, 45%‐65% from carbohydrate, and 10%‐35% from protein), 600‐800 total calories.

Treatment comparisons are percent ratios (test/reference) by analysis of variance of log‐transformed parameters using SAS Proc GLM with model: < parameter ≥ treatment period subject, then back‐transformed.

Study SD‐809‐C‐11 further evaluated the effect of meal composition on the relative bioavailability of a single 18‐mg dose of deutetrabenazine by comparing exposure after a high‐fat/high‐calorie test meal compared with a standard meal. For the ratios of the LS means of Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf, the 90%CI upper and lower bounds lie within the 80%‐125% limits, showing bioequivalence of the tested meal types (Table 5).

Discussion

Deutetrabenazine was rationally designed using specific deuteration with the intention of slowing the CYP‐dependent breakdown of the active metabolites of tetrabenazine to their less potent O‐desmethyl metabolites. Earlier studies demonstrated slowed conversion of the active α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ metabolites to inactive products, resulting in a lengthening of mean half‐life and a >2‐fold increase in overall exposure (AUC0‐inf), with only a marginally increased Cmax relative to the nondeuterated form, tetrabenazine, at the same dose of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API). 13 The studies further demonstrated reduced interindividual variability in the metabolism and the potential of deutetrabenazine to reduce the impact of genetic or acquired CYP2D6 deficiency. The pharmacokinetic studies described here investigated the final tablet formulation that was used in the pivotal clinical studies and provided additional data to establish the dosing regimen of deutetrabenazine, confirming that about half the dose of deutetrabenazine is needed to achieve the same total exposure (AUC) to active metabolites as tetrabenazine, with a resultant lowering of Cmax.

Comparing tested deutetrabenazine doses with tetrabenazine in the fasted state confirmed that the Cmax of the deuterated active metabolites is considerably lower at comparable total exposure. This led to smaller peak‐to‐trough fluctuations at steady state as reflected in the lower Cmax/Cmin ratios at all doses of deutetrabenazine compared with tetrabenazine 25 mg, when both were given twice a day. To note, this relatively large fluctuation stands behind tetrabenazine USPI requiring three‐times‐a‐day administration for daily doses >37.5 mg. The later Tmax following administration of deutetrabenazine tablets compared with tetrabenazine tablets is considered a feature of the formulation, as the comparison of the API showed only small differences. 13 The longer half‐life of the active metabolites, α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ, and the corresponding reduced exposure to their O‐desmethyl metabolites following deutetrabenazine compared with tetrabenazine show that the intended effect of deuteration observed with powder in capsule administration 13 is retained in the final tablet formulation.

The pharmacokinetics of the deuterated active metabolites are linear and approximately proportional following single deutetrabenazine doses of 6 to 24 mg and after repeated doses of 7.5 to 22.5 mg twice a day. In the investigated dose ranges, no apparent saturation of drug absorption or elimination processes was observed. Results of the ANOVA of the logarithmic transformed parameters Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf for total (α+β)‐HTBZ showed that, for all pair‐wise deutetrabenazine dose comparisons, the two 1‐sided 95% confidence limits fell with the interval of 80% to 125% required to demonstrate bioequivalence. This was also true for Cmax, AUC0‐t, and AUCinf of α‐HTBZ and for the Cmax of β‐HTBZ. For β‐HTBZ, the upper end of the 90%CI was somewhat higher for AUC0‐t and AUCinf in isolated dose comparisons. However, because exposure to the β‐HTBZ metabolite following single‐dose and repeated deutetrabenazine administration is approximately one‐third of α‐HTBZ and because both α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ are potent inhibitors of VMAT2, 6 the variance of β‐HTBZ parameters is not considered clinically meaningful.

Modest accumulation was observed for both deuterated and nondeuterated α‐HTBZ and β‐HTBZ and total (α+β)‐HTBZ when given twice a day. The ratios of parameters AUC0‐12 at steady state compared with single doses were similar for deuterated HTBZ metabolites compared with the nondeuterated HTBZ metabolites, indicating that there were no appreciable differences in the extent of accumulation between deutetrabenazine and tetrabenazine. Slight time or total daily dose dependency in the pharmacokinetics was observed, as the ratios of AUC0‐12 steady state to AUCinf single dose were > 1. This is consistent with a slight increase (10%‐20%) in the observed half‐life of the HTBZ analytes (both deuterated and nondeuterated) at steady state compared with single dose. The dose linearity of the pharmacokinetics of deuterated α‐HTBZ, β‐HTBZ, and (α+β)‐HTBZ was confirmed along with slightly greater than dose‐proportional increases in AUC and Cmax. These results are in agreement with the historical data reported for tetrabenazine. 15

Food had a minimal effect on the extent of exposure to (α+β)‐HTBZ, with only slightly increased AUC0‐t. In contrast, peak exposure as measured by Cmax was increased by approximately 50% in the presence of food, even though concentrations were still lower than those from a therapeutically equivalent dose of tetrabenazine. Thus, the administration of deutetrabenazine in the fasted or fed state preserved the desired effect with systemic exposure comparable to the active metabolites while reducing the Cmax compared with tetrabenazine. In addition, study SD‐809‐C‐11 demonstrated that the effect of food is similar across meals with different fat or caloric content because the pharmacokinetic parameters for the highest dose (18 mg) given with a high‐fat, high‐calorie meal were bioequivalent to those observed with a standard meal.

Single and repeated administration of deutetrabenazine was well tolerated. No safety concerns were observed from the clinical laboratory tests, physical examination, ECG, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9, and Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale assessments. Formulating deutetrabenazine in a tablet formulation did not introduce any unique safety concerns compared with the previously evaluated capsule formulation. 13

In summary, the studies described here demonstrate that the commercially available deutetrabenazine tablets administered with food can provide, at half the dose, the desired overall active HTBZ metabolite exposure and a lower Cmax compared with those obtained from commercially available tetrabenazine. The pharmacokinetics of total (α+β)‐HTBZ were approximately linear with dose, and the tablet formulation was not sensitive to the composition of meals consumed. Furthermore, the longer half‐life increased concentrations at trough, and together with the lower Cmax, resulted in reduced peak‐to‐trough fluctuations of the active HTBZ metabolites at steady state compared with tetrabenazine. Together, this unique pharmacokinetic profile has the potential to reduce the need for frequent dosing and lessen AEs related to peak plasma concentrations.

Conflicts of Interest

Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd acquired deutetrabenazine from Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc., La Jolla, California. Authors F.S., P.S.L, L.R.G., and M.F.G. are employees of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. Authors D.S., M.B., D.C., E.H., and J‐M.S. are former employees of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd and authors D.S. and M.B. were employees at Auspex Pharmaceuticals at the time the studies were conducted.

Funding

The studies described in this report were sponsored by Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (La Jolla, California), which was acquired by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd (Petah Tikva, Israel).

Data‐Sharing Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to patient‐level data and related study documents including the study protocol and the statistical analysis plan. Patient‐level data will be deidentified and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of trial participants and to protect commercially confidential information. Please email USMedInfo@tevapharm.com to make your request.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

References

- 1. Huntington Study Group , S Frank, Testa CM, et al. Effect of deutetrabenazine on chorea among patients with Huntington disease: an randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(1):40‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bashir H, Jankovic J. Treatment options for chorea. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18(1):51‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fernandez HH, Factor SA, Hauser RA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2003‐2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson KE, Stamler D, Davis MD, et al. Deutetrabenazine for treatment of involuntary movements in patients with tardive dyskinesia (AIM‐TD): a double‐blind randomized placebo‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Psychiatr. 2017;4(8):595‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Claassen DO Philbin M Carroll B. Deutetrabenazine for tardive dyskinesia and chorea associated with Huntington's disease: a review of clinical trial data. Expert Opin Pharmacol. 2019;20(18):2209‐2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huntington Study Group . Tetrabenazine as antichorea therapy in Huntington disease: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2006;66(3):366‐372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Armstrong MJ, Miyasaki JM. American Academy of Neurology: evidence‐based guideline: pharmacologic treatment of chorea in Huntington disease: report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79(6):597‐603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Russak EM, Bednarczyk EM. Impact of deuterium substitution on the pharmacokinetics of pharmaceuticals. Ann Pharmacother. 2019;53(2):211‐216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Timmins GS. Deuterated drugs: where are we now? Expert Opin Ther. 2014;24(10):1067‐1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yao Z, Wei X, Wu X, et al. Preparation and evaluation of tetrabenazine enantiomers and all eight stereoisomers of dihydrotetrabenazine as VMAT2 inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46(5):1841‐1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Niemann N, and Jankovic J. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a general overview with focus on the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2018;78(5):525‐541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yero T, and Rey JA. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), an FDA‐approved treatment option for Huntington's disease–related chorea. Pharm. Ther. 2008;33(12):690‐694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schneider F, Bradbury M, Baillie TA, et al. Pharmacokinetic and metabolic profile of deutetrabenazine (TEV‐50717) compared with tetrabenazine in healthy volunteers. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13(4):707‐717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. US Food and Drug Administration Guidance Document. Food‐Effect Bioavailability and Fed Bioequivalence Studies. Guidance for Industry. 2002. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/food-effect-bioavailability-and-fed-bioequivalence-studies. Accessed June 10, 2020.

- 15. Mehvar R, Jamali F, Watson M, Skelton D. Pharmacokinetics of tetrabenazine and its major metabolite in man and rat. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987;15(2):250‐255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information