Abstract

Background

Supersaturated oxygen (SSO2) has recently been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for administration after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) in patients with anterior ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) based on its demonstration of infarct size reduction in the IC‐HOT study.

Objectives

To describe the 1‐year clinical outcomes of intracoronary SSO2 treatment after pPCI in patients with anterior STEMI.

Methods

IC‐HOT was a prospective, open‐label, single‐arm study in which 100 patients without cardiogenic shock undergoing successful pPCI of an occluded left anterior descending coronary artery were treated with a 60‐min SSO2 infusion. One‐year clinical outcomes were compared with a propensity‐matched control group of similar patients with anterior STEMI enrolled in the INFUSE‐AMI trial.

Results

Baseline and postprocedural characteristics were similar in the two groups except for pre‐PCI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction 3 flow, which was less prevalent in patients treated with SSO2 (9.6% vs. 22.9%, p = .02). Treatment with SSO2 was associated with a lower 1‐year rate of the composite endpoint of all‐cause death or new‐onset heart failure (HF) or hospitalization for HF (0.0% vs. 12.3%, p = .001). All‐cause mortality, driven by cardiovascular mortality, and new‐onset HF or HF hospitalization were each individually lower in SSO2‐treated patients. There were no significant differences between groups in the 1‐year rates of reinfarction or clinically driven target vessel revascularization.

Conclusions

Infusion of SSO2 following pPCI in patients with anterior STEMI was associated with improved 1‐year clinical outcomes including lower rates of death and new‐onset HF or HF hospitalizations.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, infarct size, primary percutaneous coronary intervention, supersaturated oxygen

1. INTRODUCTION

Infarct size (IS) measured 1 month after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) for ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or technetium‐99 m sestamibi single‐photon emission computed tomography has been strongly associated with 1‐year clinical outcomes including all‐cause mortality and hospitalization for heart failure (HF). 1 Although early reperfusion therapy in STEMI has led to a decline in mortality over the past several decades, 2 myocardial salvage is often suboptimal despite high rates of restoration of epicardial coronary flow by pPCI and sustained patency of the infarct‐related artery. 3 , 4 This has been attributed to late reperfusion, microcirculatory dysfunction or no reflow, reperfusion injury, and other mechanisms.

Intracoronary infusion of hyperoxemic blood (supersaturated oxygen [SSO2] therapy) into the myocardial infarct zone after reperfusion has been shown to reduce endothelial cell edema, induce capillary vasodilatation, and limit IS in experimental animal models. 5 , 6 , 7 In the pivotal AMIHOT II trial, treatment of patients with anterior STEMI with SSO2 infused into the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) resulted in a significant reduction in IS measured at 14 days compared with control. 8 However, hemorrhagic complications were more frequent in the SSO2 group due to the need for larger or multiple femoral arterial sheaths, and nonsignificant trends were present for increased stent thrombosis and death at 30 days, possibly related to the delivery of the SSO2 through an indwelling catheter in the stented region of the LAD. As a result, the method of intracoronary SSO2 delivery was modified so that following pPCI hyperoxemic blood was infused through a diagnostic catheter to the ostium of the left main coronary artery (LMCA), so called “optimized” SSO2 delivery. The IC‐HOT study was a prospective, open‐label, single‐arm study of 100 patients undergoing successful pPCI of an occluded LAD that found that optimized SSO2 infusion via the LMCA was feasible and was associated with a favorable 30‐day safety profile, with IS at 30 days similar to that observed in the SSO2 therapy group in the AMIHOT II trial. 9 On the basis of this study, on April 2, 2019 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved SSO2 therapy for treatment of patients with anterior STEMI undergoing primary PCI within 6 hrs of symptom onset. 10

Late clinical outcomes after optimized SSO2 infusion in STEMI have not been reported. We thus sought to assess the 1‐year clinical outcomes of patients with anterior STEMI treated with SSO2 infused via the LMCA. To this end, we compared the 1‐year outcomes of patients in the IC‐HOT study with a propensity‐matched control group of similar patients with anterior STEMI enrolled in the INFUSE‐AMI (intracoronary abciximab and aspiration thrombectomy in patients with large anterior myocardial infarction [MI]) trial. 11

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and population

The study design, protocol, and primary results of the IC‐HOT study have been previously described in detail. 9 The IC‐HOT study was a prospective, open‐label, single‐arm study designed with U.S. FDA guidance to assess the safety of an optimized SSO2 infusion. A total of 100 patients with acute anterior STEMI undergoing pPCI were enrolled between February 2016 and May 2017. In brief, major inclusion criteria included presentation within 6 hrs of symptom onset with ≥1 mm ST‐segment elevation in ≥2 contiguous leads in V1–V4 or new left bundle branch block. Successful PCI of a proximal or mid LAD lesion with commercially available coronary stents and achievement of thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade 2 or 3 flow were required. Major exclusion criteria included prior coronary artery bypass grafting, prior MI, known prior left ventricular ejection fraction <40%, use of thrombolytic therapy, any prior LAD PCI, mechanical complications of the STEMI or cardiogenic shock, contraindications to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, creatinine clearance <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, and postindex PCI planned within 30 days. The local institutional review board at each center approved the study, and informed written consent was obtained from each patient before enrollment.

All patients received 324 mg aspirin and a loading dose of clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor prior to angiography. PCI was performed using standard techniques with commercially available bare metal or drug‐eluting stents.

2.2. SSO2 therapy

SSO2 therapy was initiated immediately following successful pPCI. Blood was withdrawn from the femoral sheath and circulated via a roller pump through an extracorporeal oxygenator in a polycarbonate chamber (TherOx, Irvine, CA) to achieve a PaO2 of 760–1,000 mmHg as previously described. 8 The origin of the LMCA was engaged with a 5‐Fr soft‐tip JL diagnostic catheter (IMPULSE, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) for the delivery of hyperoxemic blood. The SSO2 solution of hyperoxemic blood was then delivered at a flow rate of 100 ml/min for 60 min in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Systemic arterial PaO2 was measured prior to the SSO2 infusion, with nasal oxygen adjusted to maintain PaO2 ≥ 80 mmHg.

2.3. Definitions and endpoints

The definitions of all endpoints are provided in the original publication. 9 The primary endpoint of the current study was the composite of all‐cause death or new‐onset HF or HF hospitalization at 1 year. The definition of HF required 100% oxygen by face mask, documented PaO2 < 60 mmHg or radiographic evidence of pulmonary edema, intubation, intra‐aortic balloon counterpulsation or other mechanical circulatory device support, or HF necessitating rehospitalization. Secondary endpoints included the individual components of the primary endpoint, recurrent MI, clinically driven revascularization, and stent thrombosis. An independent central events committee reviewed and adjudicated all safety and effectiveness endpoints.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Clinical outcomes were compared with a matched set of control arm patients from the randomized INFUSE‐AMI trial, a study of very similar entry criteria (STEMI with proximal or mid‐LAD occlusion), which enrolled patients between November 2009 and December 2011. Patients from INFUSE‐AMI treated with an intralesional infusion of abciximab, the experimental therapy, were excluded from the propensity score analysis as this therapy was associated with IS reduction. A propensity score model was developed to control for selection bias in the comparison of 1‐year clinical outcomes between IC‐HOT and INFUSE‐AMI patients. The propensity score for an individual is defined as the probability of being included in the IC‐HOT (vs. INFUSE‐AMI) study conditional on the individual's baseline characteristics. The propensity score was estimated using a logistic regression model in which the study variable (IC‐HOT vs. INFUSE‐AMI) is the outcome and the baseline characteristics are the covariates. The following covariates were included in the propensity score model: Age, sex, diabetes mellitus, time from symptom onset to first device, baseline (0/1 vs. 2/3) and post‐PCI (0/1/2 vs. 3) TIMI flow assessed by the angiographic core laboratory, and target lesion location (proximal‐ vs. mid‐LAD). A greedy nearest neighbor algorithm was used to match (1:1) IC‐HOT patients with available control patients from INFUSE‐AMI. A caliper of 0.2 times the standard deviation of the propensity score was enforced.

Comparison of baseline and procedural characteristics, medical history, and clinical events were conducted by χ 2 test or Fisher exact test for binary variables, t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, and log‐rank test for time‐to‐event variables. Adjusted comparisons of IS were conducted using linear regression. All p values are 2‐tailed, and p < .05 was deemed statistically significant for all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

3. RESULTS

The propensity score‐matched cohort included 166 patients (83 patients treated with intracoronary SSO2 from IC‐HOT and 83 control patients from INFUSE‐AMI). Patients treated with SSO2 had a higher prevalence of hypertension (50.6 vs. 26.5%, p = .001), hyperlipidemia (48.2 vs. 15.7%, p < .0001), and family history of premature coronary disease (42.2 vs. 21.1%, p = .004) at baseline, while pre‐PCI TIMI 3 flow was less common in these patients (9.6 vs. 22.9%, p = .02). Otherwise, baseline characteristics, including the rate of TIMI 2 or 3 at baseline and postprocedural characteristics, were similar in the two groups (Table 1). Concomitant medications at baseline and at discharge are presented in Table 2. Treatment with aspirin, a P2Y12 inhibitor or both (dual antiplatelet therapy; DAPT) was more common among patients treated with SSO2 at baseline; however, at discharge, rates of treatment with DAPT were similar between the two groups. Treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or with angiotensin‐receptor blockers (ARB) at discharge was more common among patients who were not treated with SSO2.

TABLE 1.

Baseline and angiographic characteristics in the propensity‐matched cohorts according to treatment with SSO2

| Characteristic | SSO2 therapy (IC‐HOT) (n = 83) | No SSO2 therapy (INFUSE‐AMI) (n = 83) | Standardized difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.0 ± 10.1 | 60.4 ± 13.2 | −0.04 | .79 |

| Male | 80.7 (67/83) | 81.9 (68/83) | −0.03 | .13 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.9 ± 5.0 | 27.6 ± 4.2 | 0.27 | .09 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19.3 (16/83) | 19.3 (16/83) | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Insulin‐treated | 7.2 (6/83) | 8.5 (7/83) | −0.05 | .76 |

| History of smoking | 62.7 (52/83) | 59.8 (49/82) | 0.06 | .70 |

| Current smoker | 42.2 (35/83) | 47.6 (39/82) | −0.11 | .49 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 48.2 (40/83) | 15.7 (13/83) | 0.74 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 50.6 (42/83) | 26.5 (22/83) | 0.51 | .001 |

| Family history of premature coronary artery disease | 42.2 (35/83) | 21.1 (16/76) | 0.47 | .004 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.0 (0/83) | 1.2 (1/83) | −0.16 | .32 |

| Killip class | 0.33 | .09 | ||

| I | 95.2 (79/83) | 85.5 (65/76) | 0.33 | .04 |

| II | 3.6 (3/83) | 13.2 (10/76) | −0.35 | .03 |

| III | 1.2 (1/83) | 1.3 (1/76) | −0.01 | .95 |

| Time from symptom onset to first device (min) | 159.4 ± 70.3 | 157.7 ± 54.8 | 0.03 | .57 |

| Baseline TIMI flow grade | 0.51 | .02 | ||

| 0 | 59.0 (49/83) | 54.2 (45/83) | 0.10 | .53 |

| 1 | 0.0 (0/83) | 3.6 (3/83) | −0.27 | .25 |

| 2 | 31.2 (26/83) | 19.3 (16/83) | 0.28 | .07 |

| 3 | 9.6 (8/83) | 22.9 (19/83) | −0.36 | .02 |

| Baseline TIMI flow grade (categorized) | −0.02 | .87 | ||

| 0/1 | 59.0 (49/83) | 57.8 (48/83) | ||

| 2/3 | 41.0 (34/83) | 42.2 (35/83) | ||

| Post‐PCI TIMI flow grade | 0.14 | .59 | ||

| 0 | 0.0 (0/83) | 0.0 (0/83) | — | — |

| 1 | 0.0 (0/83) | 1.2 (1/83) | −0.16 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 13.3 (11/83) | 12.0 (10/83) | 0.04 | .82 |

| 3 | 86.7 (72/83) | 86.7 (72/83) | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Location of anterior infarct target lesion | 0.05 | .75 | ||

| Proximal LAD | 42.2 (35/83) | 39.8 (33/83) | ||

| Mid LAD | 57.8 (48/83) | 60.2 (50/83) | ||

| Propensity score | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 0.01 | .97 |

Note: Values are % (n/N) or mean ± SD.

Abbreviations: LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SSO2, supersaturated oxygen; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

TABLE 2.

Concomitant medications at baseline and at discharge in the propensity‐matched cohorts according to treatment with SSO2

| Characteristic | SSO2 therapy (IC‐HOT) (n = 83) | No SSO2 therapy (INFUSE‐AMI) (n = 83) | Standardized difference | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ||||

| Aspirin | 38.6 (32/83) | 10.8 (9/83) | 0.67 | <.0001 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 9.6 (8/83) | 0.0 (0/83) | 0.46 | .007 |

| Clopidogrel | 2.4 (2/83) | 0.0 (0/83) | 0.22 | .49 |

| Prasugrel | 0.0 (0/83) | 0.0 (0/83) | — | — |

| Ticagrelor | 7.2 (6/83) | 0.0 (0/83) | 0.39 | .03 |

| DAPT | 9.6 (8/83) | 0.0 (0/0) | 0.46 | .007 |

| Beta blockers | 10.0 (8/83) | 7.2 (6/83) | 0.10 | .53 |

| ACEi or ARB | 15.7 (13/13) | 12.1 (10/83) | 0.10 | .50 |

| ACEi | 10.8 (9/83) | 8.4 (7/83) | 0.08 | .60 |

| ARB | 4.8 (4/83) | 3.6 (3/83) | 0.06 | .70 |

| Statin | 9.6 (8/83) | 10.8 (9/83) | −0.04 | .80 |

| Discharge | ||||

| Aspirin | 96.3 (78/81) | 98.8 (82/83) | −0.16 | .36 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor | 96.3 (78/81) | 98.8 (81/82) | −0.16 | .37 |

| Clopidogrel | 44.4 (36/81) | 67.1 (55/82) | −0.47 | .004 |

| Prasugrel | 13.6 (11/81) | 31.7 (26/82) | −0.44 | .006 |

| Ticagrelor | 38.3 (31/81) | 0.0 (0/82) | 1.11 | <.0001 |

| DAPT | 92.6 (75/81) | 97.6 (81/83) | −0.23 | .14 |

| Beta blockers | 93.8 (75/80) | 96.4 (80/83) | −0.12 | .49 |

| ACEi or ARB | 75.9 (63/83) | 94.0 (78/83) | −0.52 | .001 |

| ACEi | 67.5 (56/83) | 80.4 (75/83) | −0.58 | .0003 |

| ARB | 8.43 (7/83) | 6.0 (5/83) | 0.09 | .55 |

| Statin | 60.2 (50/83) | 97.6 (81/83) | −1.02 | <.0001 |

Note: Values are % (n/N).

Abbreviations: DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ACEi, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin‐receptor blockers; SSO2, supersaturated oxygen.

3.1. Clinical outcomes

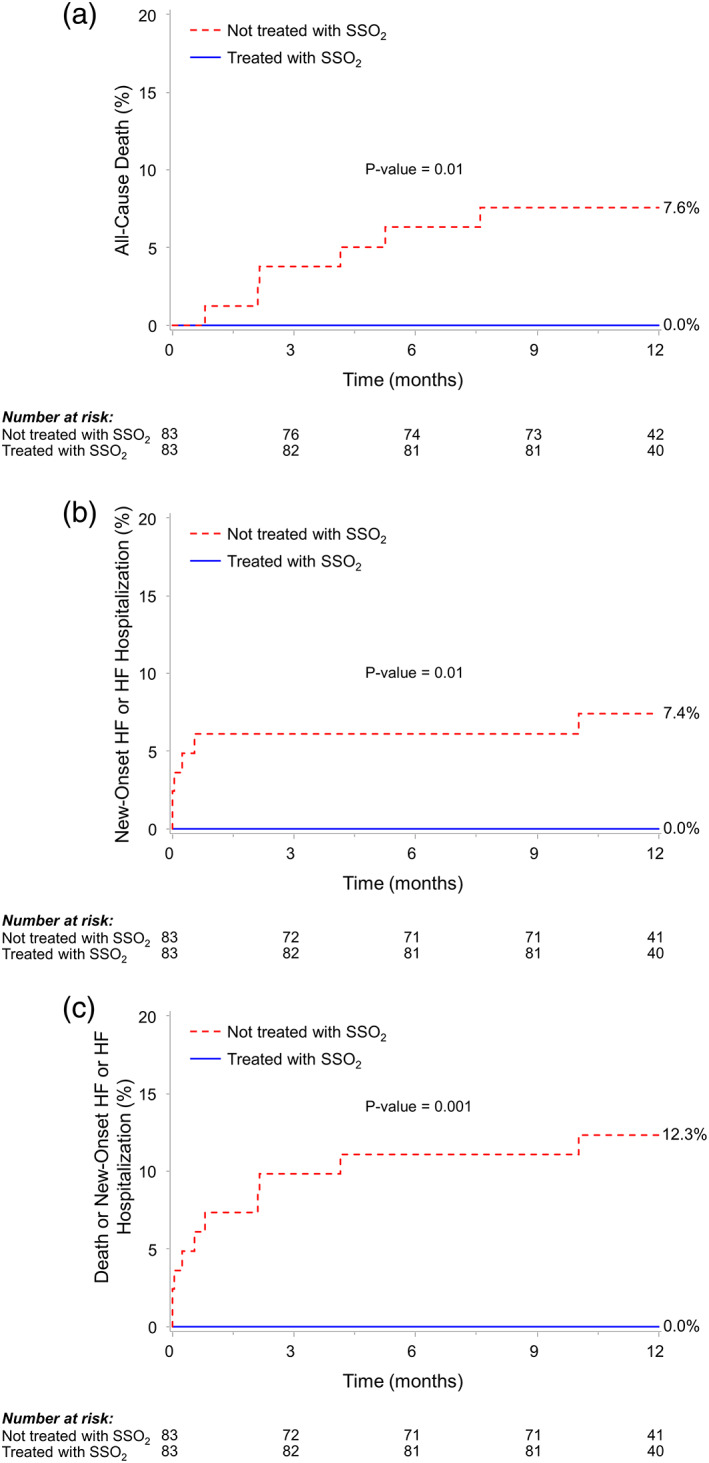

At 1 year the primary composite endpoint of all‐cause death or new‐onset HF or HF hospitalization had occurred in 0% of SSO2‐treated patients compared with 12.3% of control patients (p = .001) (Table 3 and Figure 1). Treatment with SSO2 was also associated with lower 1‐year rates of all‐cause death (0 vs. 7.6%, p = .01) driven by lower rates of cardiovascular mortality (0 vs. 4.0%, p = .04), and lower 1‐year rates of new‐onset HF or HF hospitalization (0 vs. 7.4%, p = .01). There were no significant differences between patients who were treated versus not treated with SSO2 in the 1‐year rates of reinfarction (2.4 vs. 2.4% respectively, p = .97) or clinically driven target vessel revascularization (3.1 vs. 5.1% respectively, p = .40). The rate of the composite of death, MI, clinically‐driven target vessel revascularization, or new‐onset HF or readmission for HF was also lower among patients treated with SSO2 (5.5 vs. 14.8%, p = .035). Stent thrombosis rates at 1 year were not significantly different in patients treated with SSO2 compared with control (1.2 vs. 4.9% respectively, p = .17).

TABLE 3.

One‐year clinical outcomes according to treatment with SSO2

| SSO2 therapy (IC‐HOT) (n = 83) | No SSO2 therapy (INFUSE‐AMI) (n = 83) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause death, new‐onset HF, or HF hospitalization | 0.0 (0) | 12.3 (10) | — | .001 |

| All‐cause death | 0.0 (0) | 7.6 (6) | — | .01 |

| Cardiovascular death | 0.0 (0) | 5.1 (4) | — | .04 |

| Cardiac death | 0.0 (0) | 3.8 (3) | — | .08 |

| Vascular death | 0.0 (0) | 1.3 (1) | — | .30 |

| Noncardiovascular death | 0.0 (0) | 2.6 (2) | — | .14 |

| New‐onset HF or HF hospitalization | 0.0 (0) | 7.4 (6) | — | .01 |

| MI | 2.4 (2) | 2.4 (2) | 0.97 (0.14–6.88) | .97 |

| Clinically‐driven target vessel revascularization | 3.1 (2) | 5.1 (4) | 0.49 (0.09–2.69) | .40 |

| Composite of death, new‐onset HF or readmission for HF, or clinically‐driven target vessel revascularization | 3.1 (2) | 14.8 (12) | 0.16 (0.04–0.70) | .005 |

| Composite of death, MI, or clinically‐driven target vessel revascularization | 5.5 (4) | 10.0 (8) | 0.49 (0.15–1.61) | .23 |

| Composite of death, MI, clinically‐driven target vessel revascularization, or new‐onset HF or readmission for HF | 5.5 (4) | 14.8 (12) | 0.32 (0.10–0.98) | .035 |

| Stent thrombosis (ARC definite or probable) | 1.2 (1) | 4.9 (4) | 0.25 (0.03–2.20) | .17 |

Note: Values are % (n).

Abbreviations: ARC, Academic Research Consortium; CI, confidence interval; HF, heart failure; MI, myocardial infarction; SSO2, supersaturated oxygen; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier time to first event rates in patients with anterior ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction according to treatment with SSO2. (a) All‐cause death; (b) new‐onset heart failure (HF) or HF hospitalization; and (c) death, new‐onset HF, or HF hospitalization. SSO2, supersaturated oxygen [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, treatment of patients with anterior STEMI after successful pPCI with SSO2 infused through the LMCA was associated with lower rates of the primary endpoint of all‐cause death or new‐onset HF or HF hospitalization at 1 year and its components. The current study is the first to demonstrate an association between intracoronary treatment with SSO2 after pPCI and improved long‐term clinical outcomes in patients with anterior STEMI.

Several pharmacologic strategies have been utilized in the past to improve microcirculatory function, prevent reperfusion injury, and reduce IS in patients with STEMI, including intracoronary adenosine, nitroprusside, and abciximab infusions 12 , 13 ; however, none of these treatments have been shown to improve clinical outcomes. 14 In the AMIHOT II trial, the intracoronary delivery of SSO2 significantly reduced IS after pPCI in patients with large anterior MI, 8 a parameter that is strongly predictive of subsequent death and HF rehospitalizations. 1 SSO2 thus became the first therapy demonstrated in a pivotal adequately powered randomized trial to enhance myocardial salvage and reduce IS.

While the AMIHOT II trial met its primary composite safety endpoint, bleeding complications were more frequent, and there were signals for higher 30‐day rates of stent thrombosis, myocardial rupture, and death in patients treated with SSO2. 8 Given these concerns, SSO2 delivery was “optimized” in the IC‐HOT study to be selectively infused to the origin of the LMCA rather than to the LAD at the stent site. In the IC‐HOT study, SSO2 administered via LMCA was found to be feasible and was associated with a favorable early safety profile and IS consistent with that seen in earlier studies, which led to the approval of intracoronary treatment with SSO2 by the FDA for administration after pPCI in patients with anterior STEMI. 8

The present study was not designed to elucidate the potential mechanisms for the observed improvements in death and HF after SSO2 treatment observed in the IC‐HOT study compared with similar patients with anterior STEMI treated in INFUSE‐AMI. The AMIHOT II trial established the utility of intracoronary SSO2 delivery to reduce IS, 8 a critical determinant of prognosis. 1 In addition, the observed extent of microvascular obstruction (MVO) after SSO2 therapy in IC‐HOT was only 0.30% of the left ventricular mass, which is low compared with historical controls. 15 Compromised microvascular flow after epicardial coronary artery reperfusion has been associated with reduced myocardial salvage and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, 16 and has been reported to be an independent predictor of mortality, even after accounting for IS. 15 The pathophysiology of MVO is multifactorial and includes a variety of contributing mechanisms such as distal embolization, ischemia‐induced vasoconstriction, and reperfusion injury. Thus, SSO2, which has been shown to decrease endothelial cell swelling and improve microcirculatory blood flow, 5 , 6 , 7 may decrease MVO. In addition, SSO2 administered to the LMCA in anterior STEMI is also delivered to the nonoccluded left circumflex myocardial territory, which could theoretically improve collateral flow to the infarct zone, given the vasodilatory properties of SSO2. Further study is required to examine the salutary benefits of SSO2 delivery following pPCI in patients with anterior STEMI.

4.1. Limitations

First, the present study represents an analysis from a modest‐sized propensity‐matched cohort rather than a large randomized controlled trial and should thus be considered hypothesis generating. Second, the study population represents a selected cohort of patients; therefore, findings of this study may not apply to all patients with STEMI, such as those with cardiogenic shock, nonanterior MI, and others who did not undergo pPCI with stenting within 6 hrs of symptom onset. In addition, patients from the comparator control group were drawn from the randomized INFUSE‐AMI trial; as such, there may be variability from the types of patients enrolled in a single‐arm registry such as IC‐HOT. Third, in the propensity‐matched groups the baseline TIMI 3 flow was less prevalent in the SSO2 arm, which if anything might have biased the outcomes against SSO2. Nonetheless, despite propensity‐score matching, we cannot rule out the possibility that the analysis is confounded by other unmeasured factors that are correlated with SSO2 treatment. However, the fact that in the current study reinfarction and revascularization rates did not differ between the groups suggests that the beneficial effects of SSO2 in reducing mortality and HF hospitalization are specific rather than confounded, as reinfarction and revascularization endpoints would not be expected to be affected by SSO2. Finally, some details regarding the clinical presentation such as hemodynamic instability and HF symptoms and the completeness of revascularization were not available.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the present nonrandomized but propensity‐matched controlled study, intracoronary treatment with SSO2 in patients with anterior STEMI after successful pPCI was associated with improved 1‐year clinical outcomes compared to standard treatment without SSO2, including lower rates of death and new‐onset HF or HF hospitalizations. Appropriately powered randomized trials are warranted to demonstrate the effect of SSO2 treatment on outcomes in patients with anterior STEMI after successful pPCI.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

D. C. M.: Symposium honoraria—Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific. A. S. L.: Research grant—Boston Scientific. T. A. L.: research support from Medtronic and Abiomed; speaker honorarium from Novartis and AstraZeneca. P. G.: Speaker's fees—Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Tryton Medical Inc., Cardinal Health, and Cardiovascular Systems Inc., consulting fees—Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems Inc., and Pi‐Cardia; institutional research grant—Boston Scientific. Equity—SIG.NUM, SoundBite Medical Solutions Inc., Saranas, and Pi‐Cardia. A. M.: Grant support from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific, consultant for Conavi Medical Inc. G. W. S: Consultant to TherOx, Miracor, and Abiomed. Other authors: No relevant conflicts.

STUDY REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02603835.

Chen S, David SW, Khan ZA, et al. One‐year outcomes of supersaturated oxygen therapy in acute anterior myocardial infarction: The IC‐HOT study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:1120–1126. 10.1002/ccd.29090

EDITORIAL COMMENT: Expert Article Analysis for: Supersaturated oxygen therapy in acute anterior myocardial infarction: Going small is the next big thing

Funding information The IC‐HOT study was sponsored by TherOx.

REFERENCES

- 1. Stone GW, Selker HP, Thiele H, et al. Relationship between infarct size and outcomes following primary PCI: patient‐level analysis from 10 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1674‐1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bolognese L, Neskovic AN, Parodi G, et al. Left ventricular remodeling after primary coronary angioplasty: patterns of left ventricular dilation and long‐term prognostic implications. Circulation. 2002;106:2351‐2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halkin A, Stone GW, Dixon SR, et al. Impact and determinants of left ventricular function in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:325‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartorelli AL. Hyperoxemic perfusion for treatment of reperfusion microvascular ischemia in patients with myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2003;3:253‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spears JR, Prcevski P, Xu R, et al. Aqueous oxygen attenuation of reperfusion microvascular ischemia in a canine model of myocardial infarction. ASAIO J. 2003;49:716‐720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Spears JR, Prcevski P, Jiang A, Brereton GJ, Vander Heide R. Intracoronary aqueous oxygen perfusion, performed 24 h after the onset of postinfarction reperfusion, experimentally reduces infarct size and improves left ventricular function. Int J Cardiol. 2006;113:371‐375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stone GW, Martin JL, de Boer MJ, et al. Effect of supersaturated oxygen delivery on infarct size after percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:366‐375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. David SW, Khan ZA, Patel NC, et al. Evaluation of intracoronary hyperoxemic oxygen therapy in acute anterior myocardial infarction: the IC‐HOT study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:882‐890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. TherOx DownStream System PMA P170027 approval letter. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf17/P170027a.pdf. April 2, 2019. Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 11. Stone GW, Maehara A, Witzenbichler B, et al. Intracoronary abciximab and aspiration thrombectomy in patients with large anterior myocardial infarction: the INFUSE‐AMI randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1817‐1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nazir SA, McCann GP, Greenwood JP, et al. Strategies to attenuate micro‐vascular obstruction during P‐PCI: the randomized reperfusion facilitated by local adjunctive therapy in ST‐elevation myocardial infarction trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1910‐1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eitel I, Wohrle J, Suenkel H, et al. Intracoronary compared with intravenous bolus abciximab application during primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: cardiac magnetic resonance substudy of the AIDA STEMI trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1447‐1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fordyce CB, Gersh BJ, Stone GW, Granger CB. Novel therapeutics in myocardial infarction: targeting microvascular dysfunction and reperfusion injury. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2015;36:605‐616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Waha S, Patel MR, Granger CB, et al. Relationship between microvascular obstruction and adverse events following primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient data pooled analysis from seven randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3502‐3510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu KC, Zerhouni EA, Judd RM, et al. Prognostic significance of microvascular obstruction by magnetic resonance imaging in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:765‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]