Abstract

Introduction

Peer learning is increasingly used for healthcare students in the clinical setting. However, as peer learning between students involves students taking a teaching role, it is unclear what the supervisor's role then becomes. It is vital to determine the role of the supervisor in student peer learning to ensure high quality learning and patient safety.

Methods

Semi‐structured interviews were performed with 15 student nurse supervisors (nurses and assistant nurses) from two hospital wards that practice peer learning to investigate the different ways clinical supervisors view their role in students' peer learning. Transcribed data were coded and analysed using a phenomenographic approach.

Results

Four hierarchical levels of the supervisor's understanding of their role in students’ peer learning were identified: the teacher; the facilitator; the stimulator; and the team player. These categories represent an increasingly inclusive view of which people present on the ward play a role in enabling effective peer learning.

Conclusions

The various understandings of supervisor roles have implications for how supervision of peer learning could be implemented in the future.

Short abstract

This interview study reveals different ways in which supervisors view their role in supporting peer learning: teacher; facilitator; stimulator; and team player.

1. INTRODUCTION

Peer learning can be defined as ‘people of similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching’. 1 Worldwide, universities and institutions are increasingly incorporating peer learning into their programmes formally and informally. 2 , 3 Peer learning has been investigated in medical, nursing, physiotherapy 4 and occupational therapy students 5 , 6 and can occur between students or graduates, in the workplace or non‐clinical settings. Near‐peer learning can occur between students or qualified professionals at different stages of training. 7 Existing literature reports benefits of peer learning 8 including increased student satisfaction 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ; developing a professional identity 14 ; increasing and validating students’ knowledge 15 ; building confidence 2 ; learning through social and cognitive congruence 3 , 15 , 16 ; and preparing students for their future teaching role. 17 , 18 , 19 Peer learning allows students to practice teaching, which is a requirement of qualified professionals 20 , 21 that is rarely addressed elsewhere during clinical education. 22

In peer learning, students assume the roles of both the teacher and the learner, giving rise to the question, what becomes of the supervisor? The clinical supervisor is defined as a qualified healthcare professional who is designated to be responsible for students during their clinical placements. The supervisor is also sometimes referred to as a preceptor. 23 The umbrella term of ‘supervisor’ can include roles as an educator, role model and assessor. 24 The importance of supervision of peer learning for productive peer learning and maintain high standards is known 25 , 26 , 27 ; however, the peer learning literature fails to address what the supervisor actually does. The question of how peer learning should be supervised is not addressed in a meta‐analysis of peer learning, 28 or in discussions on quality assurance. 29 In some of the literature, the clinical supervisor is described as a stakeholder, 30 their opinions on peer learning in general explored, 31 and students’ perceptions of supervision of peer learning investigated. 32 However, the supervisors’ own role, from their point of view, is often overlooked and is not clarified by any of the guidance on practicing peer learning. 28 , 33 It has been found that supervisors lack preparation for their role in the peer learning. 31

Much research exists on the supervisors’ role in student learning in non‐peer learning contexts. The roles of supervisors in these contexts have been described as information provider, role model, facilitator and mentor, assessor, evaluator, planner and resource creator. 34 Their roles depend on a wide variety of factors such as medical/clinical knowledge, clinical skill, positive relationships with students, communication skills and enthusiasm. 35 Supervisors described their roles as learner‐centred and set goals jointly with students, 36 and agreement on the role of supervision has been identified as a key part of supervisory relationships. 24 A good clinical supervisor has been described as focusing on students’ growth, focuses on professional development and being a role model and responds in a student‐centred manner. 37 Supervisors’ identity is influenced by their image of themselves as teachers, their familiarity with adult learning principles, the perceived benefits and drawbacks of teaching, and humanitarianism. 38 The supervisor's relationship with the student is also key, with the bond they form and mutual trust being important in the supervisor‐student relationship. 24

A lack of guidance on the role of the supervisor in peer learning may allow inappropriate practices of putting students in the same location in a clinical setting and expecting peer learning to just happen by itself, 39 especially when peer learning has been used as a solution to staffing problems. 31 , 40 , 41 The lack of guidance may also compromise patient safety in clinical settings where responsibility for the patient cannot lie with the student tutor who is not yet qualified. The clinical supervisor is the ‘elephant in the room’, with both their absence and their presence being contentious. In the supervisor's absence, their role could be seen as usurped or undermined 42 ; and in their presence, the student peer tutor is undermined. An understanding of the role of the supervisor in this unique pedagogical set‐up is needed to ensure that the quality of both patient care and student learning is preserved.

Peer learning today occurs in a variety of contexts, and some adapted student wards have been shown in our previous study to have a community of practice where peer learning is practiced consistently. 22 A community of practice is social learning system 43 with members that are informally bound by what they do together. 44 Student wards have a joint enterprise around peer learning, with mutual engagement of all staff, both supervisors and other healthcare professionals, in creating an environment for peer learning, and a shared repertoire of routines that allow peer learning to be a central part of the workings of the ward. 45 Student wards are inpatient hospital wards set up with adaptations for student learning. Some wards are set up specifically for peer learning, where the explicit purpose and expectation from supervisors and other staff is for student nurses to learn through peer learning. Such settings offer the opportunity to explore supervision of peer learning more deeply, as there is a well‐established community of practice around it.

2. AIM

To explore the different ways clinical supervisors view their role in students' peer learning.

3. METHODS

3.1. Study design

An interview study with a phenomenographic approach was chosen. Phenomenography (not to be confused with phenomenology) is the empirical study of the variation in ways in which people understand or experience phenomena in the world around them and how these ways of understanding are logically and hierarchically related to each other and to the perceptions of the situation in which they are experienced. 46 Phenomenography has a non‐dualistic ontology, which acknowledges that there are multiple, diverse interpretations of reality. The ontological and epistemological assumptions of phenomenography are that meaning is subjective and established by the relationship between a person and their experience of the world. 46 A structural and often hierarchical relationship between the categories (referred to as ‘outcome space’) is one of the core assumptions of phenomenography, where the categories do not necessarily represent certain respondents; instead, the focus is on qualitative differences and critical variations in ways of understanding and the relationships between them. Identifying the internal and structural relationships among the categories in the outcome space is an important additional part of the analysis in phenomenography, which is often not included in other qualitative methods of analysis. 46 Phenomenography is useful in qualitative health research 47 , 48 and medical education 46 and has been used specifically to conceptualise different teacher roles. 37 , 49 This methodology was chosen because it is a research approach with epistemological and ontological assumptions that emphasise change and complexity, 46 and our aim was to explore the variety of different ways supervisors understand their roles in peer learning.

A semi‐structured interview guide was designed with the aim of deepening understanding of the supervisors’ and other staff's perception of their role in students’ peer learning. Questions were formed and refined after pilot testing. Questions were based on the literature on supervision of workplace learning and the finding of our previous observational study on a student ward with peer learning. 22 This previous study found that peer learning and its supervision was one of the key characteristics of a student ward and was an under‐investigated area that stimulated the formation of our research question for this study.

3.2. Study setting

Two student wards specifically designed for peer learning, in two different hospitals in Stockholm, Sweden, were selected (see Table 1). The students came from two different nursing schools with similar curriculums. Although medical students were also present on one of the wards, student nurses were chosen because students of other professions did not routinely practice peer learning. 22

TABLE 1.

Details of selected wards

| Type of ward | Cardiology | Infectious diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Year started | 2015 | 2005 |

| Number of nurse supervisors per period | 6 | 4 |

| Number of students per period | 4 | 15 |

| Number of students per supervisor | 2 | 3‐4 |

| Number of students simultaneously present per shift | 2 | 7‐8 |

| Number of supervisors simultaneously present per shift | 1 | 2 |

| Number of patients per shift | 6 | 8 |

| Student nurses’ term of nursing education | 3 and 6 | 3, 5 and 6 |

| Length of placement (weeks) | 5‐6 | 5‐8 |

3.3. Participants

All nurses that supervised students on the selected wards during the study period were invited to participate by e‐mail, and participation was voluntary with no renumeration (See Table 2). Assistant nurses who formally supervised students were also invited, although their supervision duties differed in that they supervised an introductory period focussing on practical procedures at the beginning of students’ placements. Other staff including doctors and physiotherapists that worked on the ward were simultaneously working on other wards and had no formal supervision duties for student nurses and were therefore excluded.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of participant interviews

| Type of ward | Cardiology | Infectious diseases |

|---|---|---|

| Date for interviews | November 2018 to January 2019 | May 2019 to January 2020 |

| Nurse supervisors | 6 | 4 |

| Supervisors with leadership role | 2 | 1 |

| Healthcare assistants | 1 | 1 |

| TOTAL | 9 | 6 |

All the nurses (n = 15) and two out of three of the assistant nurses were interviewed.

3.4. Data collection

Individual semi‐structured interviews were performed by the first author, AD, a clinically practicing doctor and PhD student. Some participants at one ward were familiar with the interviewer after a previous observational study, 22 and other participants had no connection to the interviewer. Interviews were audio recorded, then transcribed verbatim and checked for congruency with the audio file. Each interview lasted on average 40 minutes. The participants’ quotes are represented by ward (‘I’ denoting infectious diseases ward and ‘C’ cardiology) and participant number.

3.5. Data analysis

A preliminary analysis of the data was performed simultaneously with the data collection, and NVivo software 50 was used. The results were then analysed using a phenomenographic method. This involved a seven‐step approach. 47 The first author familiarised herself with the transcripts (step 1); key quotations were condensed into meaning units of text that relates to a specific phenomenon (step 2); these were then compared (step 3); then grouped into categories with other similar meaning units (step 4); the categories were then analysed and the essence of the meaning was described (step 5); this description was given a label (step 6); and the labels were then compared to one another and sorted into the outcome space, representing ways of understanding of the supervisor's role (step 7). In phenomenography, the first steps of the analysis are similar to those of a thematic inductive analysis, meaning that there are no predefined themes or categories. The process was iterative, with much interplay and repetition between the various steps. In order to better be able to compare and contrast the different categories, they are not presented separately but discussed integrated with one another with regard to three broad areas that the data reflects; supervisors’ understandings of their own role; the student's role; and patient care.

The various interpretations of the interview data were discussed among all four authors with different backgrounds: one nurse, one junior doctor, one senior doctor and one researcher outside clinical practice. Both consensus and disagreement of the interpretation contributed to a broader understanding, and the meaning of the categories was further explored and refined.

A preliminary summary of the researchers’ interpretations of the interview findings was presented to and discussed with the staff at one student ward. They unanimously supported the interpretations and suggested no amendments or additions.

3.6. Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was received from the regional ethical committee in Stockholm (Dnr 2016/2524‐31/2). Participants gave written consent for the study after written and oral information. All data was anonymised. No patient data were collected. The risks for harm to the participants were considered, especially that the supervisors could feel that the interviewers questioned their learning techniques or passed judgement on the supervisory abilities. On balance, it was felt that the reflective nature of the questions and the clarity of the aims of the study presented to the participants ameliorated this risk.

4. RESULTS

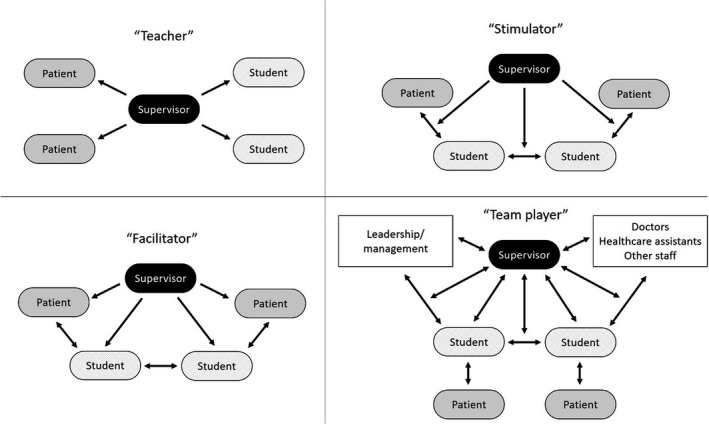

Four hierarchical levels of the supervisor's understanding of their role in students’ peer learning were identified as forming the outcome space: the teacher; the facilitator; the stimulator; and the team player. The supervisors’ view on their role varies in the breadth of focus among the four categories. The least inclusive or narrowest category is the ‘teacher’, which represents viewing supervision as a property of the supervisor themselves, and the transfer of knowledge flowed from supervisor to student. The category ‘facilitator’ broadens this view and includes the interaction between the supervisor and the student in defining the supervisor's role and views the students as able to impart knowledge themselves, to the other students and even to other staff. The category ‘stimulator’ broadens this view even more and recognises the role of the other staff, the students’ relationship between themselves, and the clinical environment as a whole, as forming and defining the supervisor's role. Highest up in the hierarchy is the category of ‘team player’, who sees a wide variety of factors not just their own actions, as all contributing to the community of peer learning. Moreover, these factors, such as the actions and attitudes of other staff, are seen as interrelated and dynamic, constantly re‐defining the role of the supervisor. The team player's role can in peer learning is not what they directly say or do with the students, but of the culture they uphold for the ward as a whole, which indirectly impacts students’ peer learning (see Table 3 and Figure 1).

TABLE 3.

Categories of ways in which supervisors understand their role in student peer learning

| Teacher | Facilitator | Stimulator | Team player | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The supervisor | Teaches students who do passive learning | Takes actions that enable students to learn by doing | Steps back to allow space for students to take initiative to learn by doing | contributes to the work environment that facilitates students to become part of the team |

| The focus is | Teacher‐led | Student‐led | Patient‐led | Community‐led |

| Peer learning happens by | Multiple students being present simultaneously with one supervisor | Supervisors getting the students to do peer learning by what they say | Supervisors getting the students to do peer learning by what they do | Supervisors contributing to the ward culture of peer learning so that it happens automatically |

| The student is | A dependent learner | An independent learner | A caregiver, can be entrusted with clinical tasks | A future colleague, a key member of the workplace |

| Clinical workload | Must be alternated and balanced with supervision | can be carried out by the supervisor at the same time as supervision as they are linked. | can be shared between the students and supervisors and learning happens alongside | is shared between all staff and students on the ward and is the key component in student learning |

FIGURE 1.

Visual representation of the different categories of the supervisor's understanding of their role in students’ peer learning. Arrows represent the transfer of information

The different levels of understanding were dynamically interrelated rather than static and were all expressed, to varying extents, by each participant, and between the different professions alike (nurses with managerial roles, supervising nurses and assistant nurses). There was a degree of temporal flow, where supervision was adapted as students matured over time and the relationship of trust between student and supervisor developed. There was temporal flow over a longer time scale too, where the staff who had worked for longer on a student ward had a tendency to give more answers reflecting the view of the supervisor in the more inclusive categories. However, even the staff with least experience in a student ward gave viewpoints in all categories. The results represent the answers of participants on both of the wards and from all staff. The majority of answers fell within the three broadest categories, where the distribution was quite even.

All four categories representing the different supervisor's view of their roles are discussed together to compare and contrast their understandings in relation to three broad areas.

4.1. The supervisor's own role

The ‘teacher’ represented the view of the supervisor as the imparter of knowledge, and the students as multiple individual learners who received that knowledge, and the transfer of knowledge was unidirectional from teacher to student. The ‘teacher’ focused on the importance of what the supervisor did to enable the students to learn. Learning was seen as an individual process occurring in individual students. There were fewest responses corresponding to the ‘teacher’ category, and these responses often alluded to how supervisors viewed their role when they or the students were new on the ward.

Both students need help simultaneously, it’s hard to know, shall I begin with one or the other. (C5)

The ‘facilitator’ represented the view of the supervisor as enabling the students to learn between themselves. They encouraged peer learning by telling the students to first try to problem solve together before asking the supervisor. Peer learning was viewed as a process that happened automatically when students are scheduled to look after the same patients, and by being told to work together.

They often forget that the other student is present, instead it’s easier to ask the supervisor… and I always interrupt and say, “You can discuss this. I will listen". (I3)

The ‘stimulator’ also enabled students to learn from one another but did this by their passive supervision style rather than by giving direct instructions. The focus shifted from what the student or teacher did, to patient care.

They say, "We’ll go and check the patient first, and then dispense medicines", and I just say "OK". (C4)

I sit on my hands and bite my tongue. (I5)

The ‘team player’ viewed their role as upholding the culture of peer learning on the ward, where the transfer of knowledge was multidirectional, staff learnt from one another and listened to the students’ point of view as much as they sought to contribute their own. The supervisor's expectations that the students are capable of providing clinical care were projected to other members of staff, who in turn treated them as valuable members of the team, empowering the students to meet those expectations. The team player viewed their role as dynamic, depending on the staff and students on the ward, both learning from past feedback and adapting to present students. The supervisors created a community of supervising peer learning by taking the time to regularly support one another in their roles through meetings and reflection.

Peer learning can happen between colleagues, can’t it? (C3)

We [nurse supervisors] talk the whole time. There are formal meetings, there are informal meetings, we have time for reflection, we have a continuous dialogue. (C9)

We have a pedagogical philosophy on our unit, where we put a lot of responsibility on the students themselves. As a supervisor, I expect much more from the students than they themselves think they can handle. (I3)

4.2. The student's role

The ‘teacher’ represented the view of the students as dependent learners who are shown or told what to do. The students needed to be supervised by direct observation or by being given instructions, and they were seen to learn through being taught by the supervisors.

I want them to collect all the equipment they need [to put in an intravenous line], and then tell me what they’re thinking of doing, then do it in practice, and feedback after. (C1)

I’ve maybe happened to just serve them the answer sometimes. (C4)

The ‘facilitator’ represented the view of students as independent learners who can take responsibility for their own learning and to whom clinical tasks can be delegated. The students could actively perform clinical tasks, either with support or independently.

It is the student that stands in front and does things with the patient. (I4)

I would rather they command their whole shift, how they plan to do their tasks and everything. (C1)

The ‘stimulator’ represented a view of students as caregivers, who can be trusted with both patient care and with their own learning. The students were seen as having their own unique experiences and knowledge that they could use to take initiative to care for patients, and to teach one another in the process. This required a development of trust between the student and supervisor which happens over time.

We don’t have a supervisor who the student follows, but a supervisor who follows the students. The students focus on the patients. (C8)

It’s hard, but we need to get to know an individual [student] really deeply… to know what they need to work on, what they don’t need to work on. (I1)

When [a student] matures, feels ready, we notice. We start small. (C9)

The ‘team player’ represented a view of the student as not only an independent learner and caregiver but as a future colleague. In addition to being delegated to like the ‘facilitator’ and entrusted like the ‘stimulator’, they even took initiative to perform clinical tasks, were a source of information and had valid opinions. The team player empowered the students to lead their own learning, allowing the development of teamwork and teaching skills that could not have been achieved with traditional supervision.

We give them a place in the team, so that they feel they are worthwhile team members, as it is really important to try out how it feels to really be listened to (C9)

4.3. Patient care duties

The ‘teacher’ represented the view of supervisors having a dual role as a supervisor and a clinician as conflicting. In this context, the balance of the separate task of patient care alongside the teaching of students was described as a challenge.

Sometimes I feel split, and that I’m not enough. (C6)

It was a challenge to be a nurse and simultaneously a supervisor. (C1)

The ‘facilitator’ represented the view of the two roles co‐existing.

We play the role of both the nurse and the supervisor. (I4)

The ‘stimulator's’ clinician and supervisor roles were seen as not only simultaneous but also integrated. This represented a view of patient care as a tool for learning rather than a separate task that must be performed alongside teaching. Therefore, peer learning relieved supervisors’ workload as students were learning resources for one another and caregivers to the patients.

Now I am both a nurse and a supervisor, they are intertwined with one another. (C3)

Being a nurse and supervisor, they go hand in hand. (C9)

The view represented by the ‘team players’ was that their clinical role was integrated not only with their supervisory role but also indivisible from the roles of the all the staff on the unit, the leadership of the unit and the work environment as a whole. This was perceived as a multidirectional interaction, where the students themselves, their opinions, experiences and personality, even their unique relationships on any particular shift, were vital in shaping their learning, and supervision of the students required adaptation to all these factors. These variables were seen as new dynamics to learn from, essential factors needed to learn the realities of their profession. The workload was seen as a shared property of all the staff and students rather than a factor attributable to an individual supervisor.

A large part of teamwork is about interprofessional learning. (C9)

When you have an educational ward where everything is about learning, the way of supervision does not conflict with what happens on the ward. What needs to be done on the ward is done by the students and supervisors, it assumes that patient care and learning go hand in hand. (I6)

5. DISCUSSION

Our findings are presented as a hierarchical description of the different views the supervisors have of their own role in peer learning, and the relationship between these different views. There is considerable overlap with previous findings of the role of the supervisor in regular (non‐peer learning) supervision, particularly supervisors as ‘teachers’ and ‘facilitators’. This is perhaps an unsurprising finding, as supervisors of peer learning have the same educational background and have almost always previously supervised in other healthcare settings. Although our research did not include a control group of supervisors on regular wards, comparing with findings from the literature we saw a tendency for supervisors of peer learning to show a broader view of supervision, with more allusions to the more inclusive categories.

The teacher is perhaps the most traditional view of what a supervisor does. Studies of the role of the clinical supervisor in regular wards often allude to conveying knowledge 37 and being an educator. 23 In the peer learning literature, the supervisor is rarely described in this way. In our study, the ‘teacher’ role was seen as difficult or stressful due to multiple students, which is echoed in previous studies. 31 This could demonstrate the inappropriateness of the teacher role in peer learning. There were signs that supervisors sense they have made a blunder when they answer students’ questions directly, indicating that they see the ‘teacher’ role as one that they should try to avoid. Although the teacher was the narrowest category of the view of a supervisor's role in peer learning, it could be necessary as part of one's repertoire in order to meet students’ expectations of regular supervision during a transition period, or to revert to it in certain circumstances.

The facilitator focused on what the student does and empowers the students’ learning activities. This facilitation includes organisational features such as scheduling multiple students to be present on the ward simultaneously and encouraging the students to perform peer learning by what they say (Table 3). Previous studies describe the supervisors role in peer learning as supporting the students in solving clinical problems, 51 taking a step back while providing support, 52 promoting student interaction by developing activities encouraging collaboration, 53 and enabling student independence. 31 The supervisor has also been described in regular learning settings as a facilitator, 23 enabling students to be independent and allowing them to assume responsibility on their own learning. 32

The stimulator focused not on what the student does, but on patient care, stimulating the students to find answers to questions and to work in a team. Not only did they make peer learning possible like the facilitator, but also compelled students to take charge of their learning and patient care by their actions or lack thereof (Table 3). Trust was necessary for the supervisor to step back and allow students to care for the patient. Trust was developed over time by creating a personal relationship between the student and supervisor, and the importance of this bond has been shown in the literature in the context of regular supervision. 24 Other supervisor roles in peer learning described in the literature include encouraging critical thinking and supporting development of independence, 52 giving students acknowledgement and confirmation, 32 which is similar to our finding of the stimulator. The stimulator's shift in focus to patient care positions both the students and supervisors as caregivers, reducing power imbalance. Creating a non‐hierarchical relationship between student and supervisor has previously been shown to foster constructive supervisor‐student relationships. 24 , 54

The team player was the most inclusive category, in which supervisors saw themselves as equal parties with all the others present on the ward in enabling student peer learning. According to Wenger's theory of a community of practice, members of a community seek to perform and align their identities to be in line with the practices and activities within that community. 55 This approach is instructive in understanding how the team player viewed their role in peer learning; supervisors were active participants in the community of practice with a distinct pattern of actions and behaviours, which became a cornerstone of the supervisor's identity. The focus was no longer on what the supervisor or student does, or on only the patient, but instead on the dynamic whole, the ward, staff and learning environment. The influence of the community of practice on how clinicians become teachers has previously been explored, 56 and it is therefore unsurprising that the community remains vital in maintenance of that role. In relation to peer learning the ‘team player’ view has been alluded to in the description that supervisors created a structure and acceptance for supervision. 52

5.1. Strengths and weaknesses

The results were discussed in relation to the results of our previous observational study 22 on one of the selected wards, and the congruency with our current findings provided methodological triangulation.

The research group considered the implications of the high response rate, which could reflect the ideals of the staff on student wards of the importance of contributing to development and learning. The interviewer's previous involvement can also explain the high response rate from one of the wards. We viewed the high response rate as a strength of the study, given that our aim was to capture the variety of views.

Although the study was conducted in two different wards with two different specialisations in two different hospitals, the study was limited to a hospital inpatient setting, the same geographical region and with students of only one profession. As supervision of peer learning shows differences from regular supervision, we believe that peer learning supervisory roles are a cornerstone of supervision and would be transferrable to other professions such as medical students, and even other settings such as primary care.

The interviewer's previous observation of the participants on one of the wards could have affected the participants’ degree of caution in their answers, as discrepancies between their observed behaviours and verbal answers would be apparent. This could have increased trustworthiness in their answers and decreased any reporting of things that in reality rarely happen, however, could also lead to under‐reporting of features that the participants assume the interview is familiar with from having observed them.

The variety of backgrounds of the authors led to many different viewpoints on interpretations. We perceived this as a strength and a broad range of viewpoints were considered.

5.2. Implications

Our findings have implications on how clinicians, educators, institutions and healthcare settings can implement supervised peer learning of students in the clinical setting.

5.2.1. Defining the supervisor's role

The view of peer learning as a threat to the hierarchy and the supervisors’ role is a barrier to the implementation of peer learning, and clinician buy‐in is a necessary step in peer learning. 42 An understanding that peer learning involves a change from the regular supervisors role rather than stepping away from teaching is important to support the process. 39 This study has explored how the role of the peer tutor relates to the supervisor that oversees these interactions. Specific decisions should be made about where the supervisor is physically present (in the same room, or nearby); how feedback will occur; for which activities will peer learning be practiced; at what stage is it appropriate for the supervisor to intervene or for the students to step out of their roles as peer tutors.

5.2.2. Role of other staff

Our findings emphasise the importance of the community of practice in upholding peer learning, and members of the interprofessional team who do not supervise students directly still have an important role in creating a learning environment where this is possible. This can be achieved through a default practice for all staff of treating the students as participants in this community; by addressing them by name; using them as a valuable resource and asking them questions; allocating them tasks within their abilities; and having expectations of them that they will participate in the team.

5.2.3. Learning to be a supervisor of peer learning

To avoid an increase in workload from supervising multiple students, supervisors must find ways of overseeing students’ interactions in peer learning. Supervisors have no formal training in peer learning and often learn these skills through experience and support from colleagues. Formal or informal support to supervisors in the form of courses, collegiate discussions and reflection can aid in helping supervisors in their role.

5.2.4. Developing trust between the student and supervisor

The development of trust in the student‐supervisor relationship has previously been shown to be a key factor in enabling peer learning to occur in a student ward. 22 The build‐up of trust is understood variably by clinical supervisors and can be seen as inherent to the student, or a dynamic process depending on the student, supervisor and contextual factors. 57 Creating opportunities for the supervisor to develop trust in the student can implemented, such as described previously in the literature, from direct observation of the trainee as a team leader or care provider, input from team members and patients. 58

6. CONCLUSION

We have identified categories representing how the supervisors viewed their role in students’ peer learning, which showed different requirements needed to shift from supervising single students to supervising multiple students and their interactions. These findings highlight the complexity and required mind shift in order for successful supervision to occur, one that requires interventions at the individual, collegial and even broader cultural level.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors meet conditions 1, 2, 3 and 4. Anna Dyar participated in the study design, developed the interview guide, performed the interviews and the initial analysis, participated in the analysis and wrote the manuscript. Terese Stenfors provided methodological expertise, participated in the study design, analysis, interpretation and critically reviewed the paper. Hanna Lachmann participated in the study design, development of the interview guide and in the analyses, and critically reviewed the draft paper. Anna Kiessling came up with the idea and design of the study, participated in the development of the interview guide, the analysis and interpretation of the results and critically reviewed the draft paper. All authors gave final approval to the submitted paper.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval was received from the regional ethical committee in Stockholm (Dnr 2016/2524‐31/2).

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the nurse supervisors at the student wards who were interviewed for the study.

Dyar A, Stenfors T, Lachmann H, Kiessling A. What about the supervisor? Clinical supervisors’ role in student nurses’ peer learning: A phenomenographic study. Med Educ.2021;55:713–723. 10.1111/medu.14436

Funding information

This project was funded by the Stockholm County Council (ALF project).

REFERENCES

- 1. Topping KJ. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. High Educ. 1996;32(3):321‐345. 10.1007/BF00138870 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bene KL, Bergus G. When learners become teachers: a review of peer teaching in medical student education. Fam Med. 2014;46(10):783‐787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ten Cate O, Durning S. Peer teaching in medical education: twelve reasons to move from theory to practice. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):591‐599. 10.1080/01421590701606799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alpine LM, Caldas FT, Barrett EM. Evaluation of a 2 to 1 peer placement supervision model by physiotherapy students and their educators. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(8):748‐755. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1458168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin M, Morris J, Moore A, Sadlo G, Crouch V. Evaluating practice education models in occupational therapy: comparing 1:1, 2:1 and 3:1 placements. Br J Occup Ther. 2004;67(5):192‐200. 10.1177/030802260406700502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Price D, Whiteside M. Implementing the 2:1 student placement model in occupational therapy: strategies for practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2016;63(2):123‐129. 10.1111/1440-1630.12257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ramani S, Mann K, Taylor D, Thampy H. Residents as teachers: Near peer learning in clinical work settings: AMEE Guide No. 106. Med Teach. 2016;38(7):642‐655. 10.3109/0142159X.2016.1147540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stenberg M, Carlson E. Swedish student nurses’ perception of peer learning as an educational model during clinical practice in a hospital setting‐an evaluation study. BMC Nurs. 2015;14(1):48. 10.1186/s12912-015-0098-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lidskog M, Löfmark A, Ahlström G. Learning through participating on an interprofessional training ward. J Interprof Care. 2009;23(5):486‐497. 10.1080/13561820902921878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lidskog M, Löfmark A, Ahlström G. Learning about each other: students’ conceptions before and after interprofessional education on a training ward. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(5):521‐533. 10.1080/13561820802168471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ponzer S, Hylin U, Kusoffsky A, et al. Interprofessional training in the context of clinical practice: Goals and students’ perceptions on clinical education wards. Med Educ. 2004;38(7):727‐736. 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mulready‐Shick J, Flanagan KM, Banister GE, Mylott L, Curtin LJ. Evaluating dedicated education units for clinical education quality. J Nurs Educ. 2013;52(11):606‐614. 10.3928/01484834-20131014-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKown T, McKeon L, Webb S, McKown L, Webb S. Using quality and safety education for nurses to guide clinical teaching on a new dedicated education unit. J Nurs Educ. 2011;50(12):706‐710. 10.3928/01484834-20111017-03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burgess A, Nestel D. Facilitating the development of professional identity through peer assisted learning in medical education. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:403‐406. 10.2147/amep.s72653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Silberberg P, Ahern C, van de Mortel TF. ‘Learners as teachers’ in general practice: stakeholders’ views of the benefits and issues. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(6):410‐417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lockspeiser TM, O’Sullivan P, Teherani A, Muller J. Understanding the experience of being taught by peers: the value of social and cognitive congruence. Adv Heal Sci Educ Theory Pr. 2008;13(3):361‐372. 10.1007/s10459-006-9049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. ten Cate O. A teaching rotation and a student teaching qualification for senior medical students. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):566‐571. 10.1080/01421590701468729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spencer J. Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ. 2003;326(7389):591‐594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dandavino M, Snell L, Wiseman J. Why medical students should learn how to teach. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):558‐565. 10.1080/01421590701477449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Högskoleförordning . https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument‐lagar/dokument/svensk‐forfattningssamling/hogskoleforordning‐1993100_sfs‐1993‐100.

- 21. General Medical Council . Tomorrow’s doctors: recommendations on undergraduate medical education. Published 2003. http://www.gmc‐uk.org/Tomorrow_s_Doctors_0414.pdf_48905759.pdf.

- 22. Dyar A, Lachmann H, Stenfors T, Kiessling A. The learning environment on a student ward: an observational study. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(5):276‐283. 10.1007/s40037-019-00538-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Omer TA, Suliman WA, Moola S. Roles and responsibilities of nurse preceptors: perception of preceptors and preceptees. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;16(1):54‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jackson D, Davison I, Adams R, Edordu A, Picton A. A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med Educ. 2019;53(9):874‐885. 10.1111/medu.13897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herrmann‐Werner A, Gramer R, Erschens R, et al. Peer‐Assisted Learning (PAL) im medizinischen Grundstudium: eine Übersicht. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2017;121:74‐81. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tai JH, Canny BJ, Haines TP, Molloy EK. Identifying opportunities for peer learning: an observational study of medical students on clinical placements. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(1):13‐24. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1165101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murray E, Alderman P, Coppola W, Grol R, Bouhuijs P, Van Der Vleuten C. What do students actually do on an internal medicine clerkship? A log diary study. Med Educ. 2001;35(12):1101‐1107. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.01053.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Burgess A, McGregor D, Mellis C. Medical students as peer tutors: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(1):115. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iwata K, Furmedge DS. Are all peer tutors and their tutoring really effective? Considering quality assurance. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):393‐395. 10.1111/medu.12968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tai J, Molloy E, Haines T, Canny B. Same‐level peer‐assisted learning in medical clinical placements: a narrative systematic review. Med Educ. 2016;50(4):469‐484. 10.1111/medu.12898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nygren F, Carlson E. Preceptors’ conceptions of a peer learning model: a phenomenographic study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;49:12‐16. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hellström‐Hyson E, Mårtensson G, Kristofferzon ML. To take responsibility or to be an onlooker. Nursing students’ experiences of two models of supervision. Nurse Educ Today. 2012;32(1):105‐110. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ross MT, Cameron HS. Peer assisted learning: a planning and implementation framework: AMEE Guide no. 30. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):527‐545. 10.1080/01421590701665886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harden RM, Crosby JR. The good teacher is more than a lecturer – the twelve roles of the teacher. Med Teach. 2000;22(4):334‐347. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, Schiffer R. What makes a good clinical teacher in medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83(5):452‐466. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816bee61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mann KV, Bruce Holmes D, Hayes VM, Burge FI, Viscount PW. Community family medicine teachers’ perceptions of their teaching role. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):278‐285. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00769.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stenfors‐Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren LO. What does it mean to be a good teacher and clinical supervisor in medical education? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(2):197‐210. 10.1007/s10459-010-9255-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stone S, Ellers B, Holmes D, Orgren R, Qualters D, Thompson J. Identifying oneself as a teacher: the perceptions of preceptors. Med Educ. 2002;36(2):180‐185. 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sevenhuysen S, Haines T, Kiegaldie D, Molloy E. Implementing collaborative and peer‐assisted learning. Clin Teach. 2016;13(5):325‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Callese T, Strowd R, Navarro B, et al. Conversation starter: advancing the theory of peer‐assisted learning. Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(1):7‐16. 10.1080/10401334.2018.1550855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ten Cate O, Durning S. Dimensions and psychology of peer teaching in medical education. Med Teach. 2007;29(6):546‐552. 10.1080/01421590701583816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tai JHM, Canny BJ, Haines TP, Molloy EK. Implementing peer learning in clinical education: a framework to address challenges in the “real world”. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(2):162‐172. 10.1080/10401334.2016.1247000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems: the career of a concept A social systems view on learning : communities of practice as social learning systems. Soc Learn Syst Communities Pract. 2010;7(2):225‐246. 10.1177/135050840072002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wenger E. Communities of practice and social learning systems: the career of a concept. In: Blackmore C, ed. Social Learning Systems and Communities of Practice. London: Springer; 1988:179‐198. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andrew N, Ferguson D, Wilkie G, Corcoran T, Simpson L. Developing professional identity in nursing academics: the role of communities of practice. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29(6):607‐611. 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stenfors‐Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren MA. A phenomenographic approach to research in medical education. Med Educ. 2013;47(3):261‐270. 10.1111/medu.12101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dahlgren LO, Fallsberg M. Phenomenography as a qualitative approach in social pharmacy research. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1991;8(4):150‐156. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barnard A, McCosker H, Gerber R. Phenomenography: a qualitative research approach for exploring understanding in health care. Qual Health Res. 1999;9(2):212‐226. 10.1177/104973299129121794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stenfors‐Hayes T, Hult H, Dahlgren LO. What does it mean to be a mentor in medical education? Med Teach. 2011;33(8):e423–e428. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.586746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. NVivo . https://www.qsrinternational.com/Nvivo/what‐is‐nvivo.

- 51. Pålsson Y, Mårtensson G, Swenne CL, Ädel E, Engström M. A peer learning intervention for nursing students in clinical practice education: a quasi‐experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;51:81‐87. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mamhidir AG, Kristofferzon ML, Hellström‐ Hyson E, Persson E, Mårtensson G. Nursing preceptors’ experiences of two clinical education models. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(4):427‐433. 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carlson E. Precepting and symbolic interactionism – a theoretical look at preceptorship during clinical practice. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(2):457‐464. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06047.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wearne SM, Dornan T, Teunissen PW, Skinner T. Supervisor continuity or co‐location: which matters in residency education? Findings from a qualitative study of remote supervisor family physicians in Australia and Canada. Acad Med. 2015;90(4):525‐531. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cantillon P, D’Eath M, De Grave W, Dornan T. How do clinicians become teachers? A communities of practice perspective. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2016;21(5):991‐1008. 10.1007/s10459-016-9674-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lundh P, Palmgren PJ, Stenfors T. Perceptions about trust: a phenomenographic study of clinical supervisors in occupational therapy. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):1‐9. 10.1186/s12909-019-1850-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hauer KE, Oza SK, Kogan JR, et al. How clinical supervisors develop trust in their trainees: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2015;49(8):783‐795. 10.1111/medu.12745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material