Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to determine the potential diagnostic yield of prenatal whole exome sequencing in fetuses with structural anomalies on expert ultrasound scans and normal chromosomal microarray results.

Material and methods

In the period 2013‐2016, 391 pregnant women with fetal ultrasound anomalies who received normal chromosomal microarray results, were referred for additional genetic counseling and opted for additional molecular testing pre‐ and/or postnatally. Most of the couples received only a targeted molecular test and in 159 cases (40.7%) whole exome sequencing (broad gene panels or open exome) was performed. The results of these molecular tests were evaluated retrospectively, regardless of the time of the genetic diagnosis (prenatal or postnatal).

Results

In 76 of 391 fetuses (19.4%, 95% CI 15.8%‐23.6%) molecular testing provided a genetic diagnosis with identification of (likely) pathogenic variants. In the majority of cases (91.1%, 73/76) the (likely) pathogenic variant would be detected by prenatal whole exome sequencing analysis.

Conclusions

Our retrospective cohort study shows that prenatal whole exome sequencing, if offered by a clinical geneticist, in addition to chromosomal microarray, would notably increase the diagnostic yield in fetuses with ultrasound anomalies and would allow early diagnosis of a genetic disorder irrespective of the (incomplete) fetal phenotype.

Keywords: diagnostic yield, fetal anomalies, prenatal diagnosis, prenatal whole exome sequencing testing, ultrasound anomalies, whole exome sequencing

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- ISS

isolated single system

- NGS

Next Generation Sequencing

- TMT

targeted molecular testing

- WES

whole exome sequencing

Key Message.

Prenatal whole exome sequencing, if offered by a clinical geneticist in case of both isolated and multiple ultrasound anomalies, would detect (likely) pathogenic variants in 18.7% of fetuses and allow early diagnosis of a genetic disorder irrespective of the (incomplete) fetal phenotype.

1. INTRODUCTION

The incidence of congenital structural malformations is approximately 3% in pregnancies worldwide. 1 Most of these malformations are detectable during the second trimester of pregnancy, half of them as early as in the first trimester. 2 There is a wide range of potential outcomes for fetuses with malformations depending on the type of malformation, whether an anomaly is isolated or not, and the potential underlying genetic etiology. 1 Congenital malformations vary from either isolated mild anomalies (ie, postaxial polydactyly) to potentially lethal, multisystem anomalies. When ultrasound anomalies are detected, prenatal cytogenetic diagnosis is routinely offered. In such pregnancies a chromosomal microarray on DNA isolated from chorionic villi or amniocytes is recommended for optimal detection of chromosomal aberrations. 3 It was shown that chromosomal microarray improves diagnosis by up to 6.8% over conventional karyotyping, by detecting (sub)microscopic pathogenic copy number variants in isolated and non‐isolated anomalies. 4 Although microarray analysis enables testing with much higher resolution than conventional karyotyping, the cause of the abnormal phenotype remains unknown in ~75% of the pregnant women referred due to an ultrasound anomaly. 5 In many prenatal diagnostic centers these pregnant women are currently offered additional genetic counseling. When the fetus shows specific features that allow targeted DNA testing, a targeted molecular test can be performed. When the targeted analysis shows normal results, the fetus may have a non‐syndromic birth defect or an undiagnosed genetic disorder that is not detectable with conventional karyotyping, chromosomal microarray or targeted DNA analysis.

In contrast to chromosomal microarray, which offers genome‐wide detection of chromosomal aberrations (genotype first approach), there is currently only a limited number of targeted DNA tests for monogenic disorders that are possible during pregnancy because of the limited prenatal phenotype. Although prenatal imaging (ultrasound, MRI) has dramatically improved, the clinical information obtained is still limited in comparison with postnatal phenotyping. If a pregnancy is continued and a child with congenital anomalies is born, sometimes the phenotype is evident after birth and (further) targeted genetic testing becomes feasible. Because the fetal phenotype is limited to ultrasound findings we anticipate that, similar to chromosomal microarray, routine prenatal whole exome sequencing (WES) will improve prenatal diagnostic yield. The molecular characterization of a disease has fundamental implications in the clinical setting. The etiologic definition of the prenatal phenotype is useful to discuss the parents’ reproductive choices (eg, continuation or termination of pregnancy) of the current affected pregnancy. Not only reproduction autonomy is facilitated, but this knowledge provides optimal birth management (eg, planned birth at a university hospital, planned cesarean section) and allows specific early interventions after birth for the identified disease. Furthermore, it withdraws ineffective or potentially harmful investigations and/or treatments after birth. 6 Parents can be provided with detailed prognostic counseling useful to predict potential complications. And finally, molecular diagnosis enables recurrence risk assessment as well as prenatal or preimplantation diagnosis in future pregnancies. 6 , 7

To assess the potential diagnostic yield of prenatal WES a retrospective analysis of a cohort of fetuses with ultrasound anomalies, but normal prenatal microarray result, was performed and the results are presented here.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

We performed a retrospective analysis investigating the potential influence of WES on the diagnostic yield of prenatal genetic diagnostics. In the period 2013‐2016, 391 pregnant women with fetal ultrasound anomalies who received normal prenatal microarray results were referred for additional genetic counseling and opted for additional molecular testing pre‐ and/or postnatally. Only fetal cases that underwent invasive prenatal sampling were included in this cohort. The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting information (Tables S1‐S5, Figure S1). Additionally, variants are submitted to the DECIPHER database (see Supporting information, Appendix S1).

2.1. Routine diagnostic follow up in pregnancies with ultrasound anomalies in this cohort

Fetal anomalies from our cohort were suspected by routine ultrasound scanning, mostly in the setting of second‐trimester ultrasound screening, and diagnosed by expert ultrasound examination in a center for prenatal diagnosis. Prospective parents were offered pretest counseling on the routine test characteristics and potential benefits and disadvantages for prenatal genetic testing and invasive testing (chorionic villi sampling or amniocentesis). Twin pregnancies where both fetuses had different anomalies and were both sampled, were counted as two separate individuals. After invasive testing, in some cases rapid aneuploidy detection preceded the microarray analysis. If no pathogenic chromosomal aberration was found, additional genetic counseling was considered and, if feasible, a molecular test was offered.

2.2. Targeted molecular testing

Targeted molecular testing (TMT) included a targeted test for an individual disorder, either through Sanger sequencing of a single gene or multiple genes associated with the same disorder or through targeted analysis of multiple genes through next‐generation sequencing (NGS) panels for individual disorders. TMT was performed in cases with a fetal phenotype suggestive for a specific monogenetic disorder (eg, Sanger sequencing of FGFR3 when the fetus presents with a skeletal dysplasia suggestive for achondroplasia).

2.3. Broad molecular testing

Broad molecular testing includes NGS multi‐gene panel analysis targeting multiple disorders (broad gene panels) or analyzing the whole exome (WES). Broad molecular testing was performed when the ultrasound anomalies were non‐suggestive for a specific disorder, but suspect for a genetic cause. Broad gene panels allowed analysis of many genes associated with various symptoms. Some of these panels were improved over time by expanding the panel with extra (newly discovered) well‐described genes. For the general description of the available gene panels see Supporting information (Table S1). The multiple congenital malformations panel and intellectual disability panel were the largest gene panels used. Molecular testing was only performed after thorough counseling (including information about all possible outcomes) and written informed consent from both parents. The multiple congenital malformations and intellectual disability panel as well as open exome analysis were performed on trios (fetus and both parents) for filtering and analysis. In a few cases the open exome was analyzed: sequencing of the exome (the exons of the genome) outside the previously performed gene panel. There are, however, certain parts of the exome that are not (fully) covered with this test.

Fetal DNA for molecular testing was extracted from amniocytes, chorionic villi or from fetal tissues when available after termination of pregnancy or after birth (skin biopsy or umbilical cord blood/biopsy).

2.4. Reported variants

The variants were classified according to Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. 8 , 9 Relevant findings included the class 5 (pathogenic) and class 4 (likely pathogenic) variants. Cases with class 3 variants (variant of uncertain significance) were excluded, unless they were found together with a pathogenic variant on the second allele in case of a recessive disorder matching the fetal phenotype.

2.5. Cohort selection

A total of 391 couples who opted for additional molecular testing either during pregnancy or during postnatal follow up were included in this study. All ultrasound fetal anomalies were included regardless of the severity of these anomalies to create a clinically representative cohort. Some parents postponed (targeted or broad) molecular testing until after the child was born as they, for example, chose termination of the pregnancy based on the ultrasound abnormalities. The results of all performed molecular tests were evaluated retrospectively, regardless of the time of the genetic diagnosis (prenatal or postnatal). The patients were grouped based on their ultrasound anomalies similar to Shaffer et al and Raniga et al (see Supporting information, Table S2) 10 , 11 :

251 fetuses showed one or more major abnormalities (possibly in combination with soft markers) that only involved one organ system (eg, bell‐shaped thorax and short femur). These systems included the central nervous system, musculoskeletal system, cardiovascular system, craniofacial system, gastrointestinal system and urogenital system. Notably, this group also contained the strictly isolated anomalies (eg, isolated nuchal translucency >3.5 mm, isolated cleft lip) (isolated single system).

26 patients were referred due to prenatal diagnosis for one single major fetal abnormality accompanied by one or more soft markers involving a different organ system (eg cleft lip and single umbilical artery) (multiple anomalies (1 system + soft marker in another organ system).

93 fetal cases with at least two major malformations in different organ systems (multisystem malformations, for example, ventriculomegaly and ventricular septal defect) (multiple system anomalies).

Only 21 fetal cases were enrolled with ultrasound abnormalities consisting exclusively of soft markers (mostly due to echogenic bowel) (soft marker(s) only [SM]).

2.6. Statistical analyses

The percentage of cases with relevant clinical (likely) pathogenic single nucleotide variants in fetuses with ultrasound anomalies and with normal chromosomal microarray results is reported with Wilson score 95% confidence intervals, which have a good coverage probability even for small samples and estimated percentages close to zero or one hundred. 12 Computations were performed using the epitools epidemiological calculator (Sergeant, ESG, 2018. Epitools Epidemiological Calculators. Ausvet; available at: http://epitools.ausvet.com.au).

2.7. Ethical approval

All presented data are anonymous and do not allow identification of the individual patients and were obtained during routine diagnostic procedures. Patients are informed that we may investigate/publish their medical data as long as all data remain anonymous and cannot lead to the identification of the individual persons. Our research represents a retrospective patient records study that does not fall under the scope of the WMO (The Medical Scientific Research with Humans Act), and therefore it did not need to be assessed by an accredited Medical Ethical Committee or the CCMO (Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects). According to the Research Codes of Erasmus MC and the FMWV Code of Conduct for Health Research the data that cannot be traced to an individual may be used for research.

3. RESULTS

Three hundred and ninety‐one fetal cases where molecular testing was performed were enrolled. Figure S1 (in the Supporting information) illustrates the diagnostic process and tests preceding (open) exome analysis (WES). As WES was not yet routinely performed, in most cases only TMT was performed. In 50/309 (16.2%, 95% CI 12.5%‐20.7%) cases referred for TMT a (likely) pathogenic variant was found. Forty‐seven cases underwent additional broad molecular testing. In total, in 159 cases broad molecular testing using NGS panel and/or open exome sequencing analysis WES (43/159) were performed. Of these 43 cases, open exome analysis was preceded by broad molecular testing in 30 cases. In 26/159 (16.4%, 95% CI 11.4%‐22.9%) a (likely) pathogenic variant was found. Overall, molecular testing yielded a definitive diagnosis by identifying a (likely) pathogenic variant in 76 of the 391 enrolled cases (19.4%, 95% CI 15.8%‐23.6%). Three cases showed hypomethylation of H19 causing Silver‐Russell syndrome, which cannot be detected by offering prenatal WES. Therefore, we calculated that in 18.7% (95% CI 15.1%‐22.8%) of cases (73/391) prenatal WES would detect the (likely) pathogenic variant if offered prenatally. The syndromes/diseases that were most often found were Noonan syndrome (n = 13) and cystic fibrosis (n = 3). However, in our cohort only targeted testing for Noonan syndrome (in the first or early second trimester in cases with neck anomalies) would be feasible before WES request. Cystic fibrosis was often tested in late second trimester, therefore it is not feasible to exclude cystic fibrosis first and then request prenatal WES. If all 13 cases of Noonan syndrome were excluded in the first trimester, the expected diagnostic yield would be 60/378 (15.9%, 95% CI 12.5%‐19.9%) (if only the remaining 378 [ie, 391–13] fetuses were further tested with WES).

Table 1 summarizes cases where a syndromic disorder was detected per category of ultrasound anomaly. All phenotypic case details are shown in the Supporting information (Table S3). Table S4 shows further individual case details and the (likely) pathogenic variants that were detected in this cohort.

TABLE 1.

Summary of cases: fetal phenotypes at the time of invasive sampling and the syndromic disorders detected by various molecular tests in the presented cohort

| Indication for prenatal testing | Gene |

Molecular diagnosis Phenotypic MIM number |

Indication for prenatal testing | Gene |

Diagnosis Phenotypic MIM number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal (17) | Hydrops (7) | ||||

| Short long bones with restrained curvature | DYNC2H1 | Jeune syndrome (short‐rib thoracic dysplasia 3 with or without polydactyly) #613091 | Six cases of hydrops fetalis | PTPN11, RAF1, SOS1 | Noonan syndrome #163950 |

| Signs of skeletal dysplasia | DYNC2H1 | Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy 3) #613091 | Hydrops fetalis | UNC13D | Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 3 #608898 |

| Short limbs | DYNC2H1 | Jeune syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy 3) #613091 | IUGR (3) | ||

| Short long bones, rocker bottom foot right | LEPRE1 ( P3H1) | Osteogenesis imperfecta type 8 #610915 | IUGR | BRCA2 | Fanconi anemia #605724 |

| Signs of skeletal dysplasia | COL1A1 | Osteogenesis imperfecta type 2 #166210 | IUGR | H19 | Silver‐Russell syndrome #180680 |

| Signs of skeletal dysplasia, short ribcage, short long bones with restrained curvature | COL1A1 | Osteogenesis imperfecta type 2 #166200 | IUGR | DDX11 | Warsaw breakage syndrome #613398 |

| Signs of skeletal dysplasia, sacral agenesis, rocker bottom feet | COL2A1 | Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenital (SEDC) #183900 | Genitourinary (4) | ||

| Short long bones | COL2A1 | Spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia congenital (SEDC) #183900 | Unilateral multicystic renal dysplasia and pyelectasis with echogenic cortex left | HNF1B | Renal cysts and diabetes syndrome (RCAD) #137920 |

| Contracture of the hands (flexion of the wrists), short long bones | B3GALT6 | Spondyloepimetaphyseal dysplasia with joint laxity, type 1, with or without fractures #271640 | Ambiguous genitalia | CYP21A2 | Adrenal hyperplasia, congenital, due to 21‐ hydroxylase deficiency #201910 |

| Short long bones | COL2A1 | Achondrogenesis, type II #200610 | Polycystic renal dysplasia | ANKS6 | Nephronophthisis 16 #615382 |

| Short long bones | FGFR3 | Achondroplasia #100800 | LUTO/hydronephrosis, anhydramnios | FRAS1 | Fraser syndrome #219000 |

| Micrognathia | COL1A1 | Marshall syndrome #154780 | CNS (4) | ||

| Micro‐retrognathia | COL2A1 | Stickler syndrome type 1 #108300 | Macrocephaly, frontal bossing | PIK3CA | Megalencephaly‐capillary malformation syndrome (M‐CAP) #602501 |

| Signs of arthrogryposis | ECEL1 | Distal arthrogryposis type 5D #615065 | Dysgenesis of corpus callosum | FLNA | Periventricular nodular heterotopia and corpus callosum hypoplasia #300049 |

| Unilateral reduction defect of the upper extremity | DOCK6 | Adams/Oliver syndrome #614219 | Ventriculomegaly and hypoplastic cerebellum | ISPD | Walker‐Warburg syndrome (congenital muscular dystrophy‐dystroglycanopathy with brain and eye anomalies type A) #614643 |

| Signs of skeletal dysplasia, hand and foot anomalies, polydactyly, short long bones and short ribs | EVC | Ellis van Creveld syndrome #225500 | Lissencephaly | DCX | Subcortical laminar heterotopia, X‐linked, included double cortex syndrome #300067 |

| Short long bones, bell‐shaped thorax | FGFR3 | Thanatophoric dysplasia type I #187600 | NT ≥ 3.5 mm (3) | ||

| Major anomaly accompanied by a soft marker in another system (6) | 3 cases: NT 3.6 mm, NT 8.3 mm, NT 8.0 mm | PTPN11 | Noonan syndrome #163950 | ||

| Hydrops fetalis, ascites, echogenic bowel | CFTR | Cystic fibrosis #602421 | Multiple system anomalies | ||

| Ventriculomegaly, echogenic bowel | SOX2 | Microphthalmia, syndromic 3 #206900 | NT 9.3 mm, cardiac anomalies | PTPN11 | Noonan syndrome #163950 |

| IUGR, echogenic bowel, short femoral bones | SKIV2L |

Trichohepatoenteric syndrome (THES) type 2 #614602 |

Hydrops fetalis, complex cardiac anomalies, abnormal intracranial anatomy | PTPN11 | Noonan syndrome #163950 |

| Short long bones and bilateral pyelectasis | H19 | Silver‐Russell syndrome #180680 | NT 8.0 mm and unilateral talipes | RAF1 | Noonan syndrome #611553 |

| SUA, pyelectasis, asymmetric ventriculomegaly | ZEB2 | Mowat‐Wilson syndrome #235730 | Dandy Walker malformation, polycystic renal disease, oligohydramios | CEP290 | Joubert syndrome type 5 #610188 |

| Bilateral talipes, varix vena umbilicalis | PTEN | Cowden syndrome PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS) #158350 | Vermis hypoplasia, ventriculomegaly, severe dysplastic renal disease, anhydramnios, ascites | CEP290 | Joubert syndrome #610188 |

| Cardiovascular (2) | Craniofacial defect, semi‐lobar holoprosencephaly, encephalocele, retrognathia, bilateral (multiple) renal cysts, deformity of the hands and feet. | CC2D2A | Joubert syndrome 9 #612284 or Meckel Gruber syndrome 6 #612284) | ||

| Complex cardiac anomaly | MASP1 | 3MC syndrome 1 #257920 | NT 4.6 mm, AVSD, absence cavum septi pellucidi, severe vermian defect, | ARID1A | Coffin‐ Siris syndrome #614607 |

| AVSD | PTPN11 | Noonan syndrome #163950 | VSD, corpus callosum dysgenesis, ventriculomegaly | ARID1A | Coffin‐Siris syndrome #614607 |

| Mild ventriculomegaly, dysgenesis of corpus callosum, rocker bottom foot, SUA | SMARCB1 | Coffin‐Siris syndrome #614608 | |||

| Gastrointestinal (2) | Spina bifida, oligohydramnios and IUGR | MANBA | β‐Mannosidosis #248510 | ||

| Echogenic bowel, dilated intestinal loop | CFTR | Cystic fibrosis #602421 | Encephalocele, ventriculomegaly, micrognathia, palatoschisis, polydactyly, pes equinovarus, bilateral clubhand and clubfeet, VSD | HSPG2 | Dyssegmental dysplasia, type Silverman‐Handmaker #224410 |

| Omphalocele | CDKN1C | Beckwith‐Wiedemann syndrome #130650 | IUGR, microcephaly, porencephaly, hypotelorism, micrognathia | RNU4ATAC | Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism type 1 #210710 |

| Soft markers (1) | Arthrogryposis, midline defect | MYH3 | Freeman‐Sheldon syndrome (distal arthrogryposis type 2A) #193700 | ||

| SUA, echogenic bowel | CFTR | Cystic fibrosis #602421 | VSD, short femur, pyelectasis, and urinary bladder cyst | CREBBP | Rubinstein‐ Taybi syndrome #180849 |

| Multiple system anomalies (27) | Cleft hand/foot malformation, small abdominal circumference | H19 | Silver‐Russell syndrome #180680 | ||

| SUA, AVSD, small abdominal circumference < P1 | SETD5 | Mental retardation (MRD) type 23 #615761 | Hydrops fetalis, severe short extremities and retained curvature of the bones | COL1A1 | Osteogenesis imperfecta type 2A #166210 |

| Hydrops fetalis, complex cardiac anomalies | KMT2D | Kabuki syndrome 1 #147920 | Microcephaly, IUGR | DHCR7 | Smith‐Lemli‐Opitz syndrome #270400 |

| CL, tetralogy of Fallot, hypertelorism, hypospadias | MID1 | Opitz G/BBB syndrome #300000 | Nuchal fold, possible syndactyly, craniosynostosis (sutura coronalis sinistra) | FGFR2 | Apert syndrome #101200 |

| NT 7 mm, SUA, echogenic bowel, dilated LV abnormal mitralis valve, aortic valve with high PSV, cardiomegaly | NOTCH1 | Adams‐Oliver syndrome #616028 | Exencephaly, bilateral enlarged cystic renal disease with no filling of the urinary bladder, bilateral talipes | CC2D2A | Meckel syndrome type 6 #612284 |

| Bilateral enlarged kidneys, enlarged cisterna magna, ascites, pes equinovarus and oligohydramnios | BBS2 | Bardet‐Biedl syndrome #209900 | complex cardiac anomalies, abnormal fossa posterior, abdominal cyst | CHD7 | CHARGE syndrome #214800 |

|

Bilateral cleft palate and lip, polydactyly, nuchal fold thickening, echogenic focus within heart, stenosis of the arteria pulmonalis, mild tricuspid valve insufficiency and stenosis |

CEP164 | Nephronophthisis 15 #614845 | Prefrontal edema, ascites, hypoplastic nose, kyphoscoliosis thoraco‐lumbar, bilateral rocker bottom feet, bilateral clenched hands, short long bones < p5, bell‐shaped thorax | COG5 | Congenital disorder of glycosylation type IIi (CDG2i) #613612 |

Abbreviations: AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; CL, cleft lip; CNS, central nervous system; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; LUTO, lower urinary tract obstruction; LV, left ventricle; NT, nuchal translucency; PSV, persistent sciatic vein; SUA, single umbilical artery; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

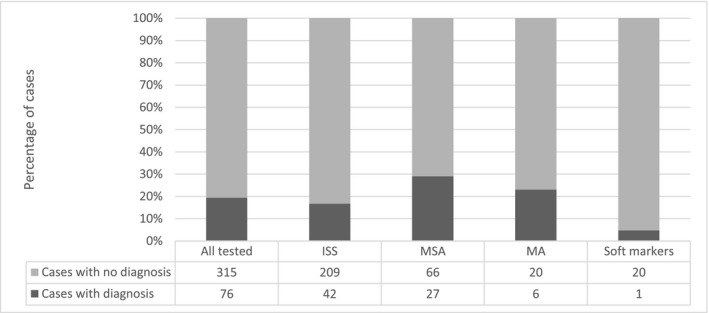

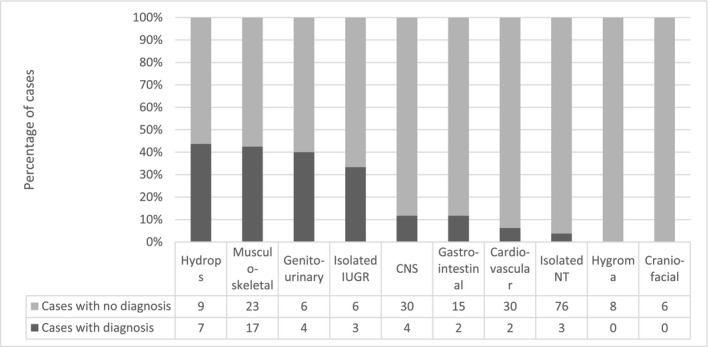

The diagnostic yield rates were subdivided into major categories shown in the Supporting information (Table S2). Most (likely) pathogenic findings were identified in fetuses with multiple system anomalies, 27/93 (29.0%, 95% CI 20.8%‐38.9%) (Table 2). The majority of fetuses in our cohort showed (apparently isolated) single system malformations. In 16.7% of these fetuses (42/251, 16.7%, 95% CI 12.6%‐21.8%) a molecular diagnosis was made. Figure 1 presents the number and percentage of cases with molecular diagnosis in fetuses per ultrasound category: fetuses with multiple system anomalies, fetuses with multiple anomalies (1 system + soft marker(s) in another organ, multiple anomalies), fetuses with anomalies isolated single system and fetuses with (multiple) soft markers. Figure 2 shows the number and percentage of abnormal cases per ultrasound anomaly within the isolated single system category. The results in fetuses with isolated nuchal translucency, hygroma colli and hydrops fetalis were also given separately. The highest percentage of abnormal cases was found in cases with hydrops fetalis and in cases with musculoskeletal anomalies. Unfortunately, the individual groups were too small to calculate statistically significant percentages. More cases are needed to study the prevalence of pathogenic variants in these subgroups. Interestingly in four out of six consanguineous couples that were tested, a recessive disorder explaining the fetal phenotype was detected (F32, F38, F44, F58, Supporting information, Tables S3 and S4).

TABLE 2.

The diagnostic yield rates in our cohort subdivided into major categories, the diagnostic yields after Noonan syndrome and cystic fibrosis are excluded and overall potential diagnostic yield of prenatal WES (after exclusion of imprinting disorders)

| Category of ultrasound anomalies | Overall DY | Overall without Noonan/CF cases | Overall potential DY of WES if applied instead of targeted testing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | DY rate; % (95% CI) | No. of Noonan and CF cases | n | DY rate; % (95% CI) | No. of Silver‐Russell cases a | n | DY rate; % (95% CI) | |

| (1) ISS | 42/251 | 16.7% (12.6%‐21.8%) | 11 | 31/240 | 12.9% (9.3%‐17.8%) | 1 | 41/251 | 16.3% (12.3%‐21.4%) |

| (2) MA | 6/26 | 23.1% (11.0%‐42.1%) | 1 | 5/25 | 20.0% (8.9%‐39.1%) | 1 | 5/26 | 19.2% (8.5%‐37.9%) |

| (3) MSA | 27/93 | 29.0% (20.8%‐38.9%) | 3 | 24/90 | 26.7% (18.6%‐36.6%) | 1 | 26/93 | 28.0% (19.9%‐37.8%) |

| (4) SM | 1/21 | 4.8% (0.8%‐22.7%) | 1 | 0/20 | 0.0% (0.0%‐16.1%) | 0 | 1/21 | 4.8% (0.8%‐22.7%) |

| All cases | 76/391 | 19.4% (15.8%‐23.6%) | 16 | 60/375 | 16.0% (12.6%‐20.1%) | 3 | 73/391 | 18.7% (15.1%‐22.8%) |

Abbreviations: CF, cystic fibrosis; CI, confidence interval; DY, diagnostic yield; ISS, (isolated) single system anomalies; MA, multiple anomalies (1 system + soft marker in another organ system); MSA, multiple system anomalies; SM, soft marker(s) only; WES, whole exome sequencing.

Cases of abnormal methylation would still remain undetected if prenatal WES was implemented.

FIGURE 1.

Number and percentage of cases with a molecular diagnosis per ultrasound category. The total number of tested cases was 391. ISS, (isolated) single system; MA, major anomaly accompanied by a soft marker in another system; MSA, multiple system anomalies

FIGURE 2.

Number and percentage of cases with a molecular diagnosis per category of (apparently) isolated anomalies. The total number of cases with (apparently) isolated anomalies was 251. IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; CNS, central nervous system; NT, nuchal translucency

Only 14/76 cases were diagnosed during pregnancy (Supporting information, Table S3), because prenatal WES was not offered before 2017. In the remaining cases, it was not feasible to achieve diagnosis before birth or before termination of pregnancy. In the remaining fetuses, diagnosis was made either after termination of pregnancy (parents did not want to wait for further testing or achieving results was not feasible before 24 weeks of gestation) or after birth when new phenotypic information became available. Due to the obstacles mentioned above the time span from invasive sampling to receiving a positive molecular result from the laboratory varied from 7 days to 1001 days (median = 200, mean = 271, data not shown, calculated from the date of invasive sampling until the reporting date).

In our cohort, only in 36 cases ultrasound anomalies were diagnosed in the third trimester. In the large majority of cases (355/391, 90.8%) ultrasound anomalies were detected in the first or second trimester. Therefore invasive sampling was performed before the 24th week of gestation. Prenatal WES, if directly offered, may significantly contribute to pregnancy management (Supporting information, Table S5).

3.1. Unexpected diagnoses, so‐called incidental findings

Unexpected diagnoses are results that seem to be unrelated to the primary indication of the molecular test and may or may not be relevant to the patient's health. 13 In our cohort, one incidental finding was documented by performing gene panels (F60, see Supporting information, Table S3). The fetus had a neural tube defect and growth restriction. The multiple congenital malformations panel showed a pathogenic variant in homozygous form in the MANB gene, causing β‐mannosidosis. β‐Mannosidosis is a rare lysosomal storage disorder of glycoprotein catabolism caused by a deficiency of lysosomal β‐mannosidase activity (MIM #248510). β‐Mannosidosis is not associated with structural fetal malformations. The patients’ phenotype is variable and the age of onset ranges between infancy and adolescence. Individuals with β‐mannosidosis can show intellectual disability, delayed motor development and epileptic seizures (MIM #248510). Both parents were found to be heterozygous for the pathogenic variant, which implicates a recurrence risk of 25%.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to evaluate the potential (additional) value of WES for explaining fetal anomalies found during the fetal anomaly scan. In our department, clinical geneticists select patients for additional molecular testing, so we were especially interested in the diagnostic yield in our selected population. Our data showed that in our patient group the potential diagnostic yield is high enough to offer prenatal WES at the time of invasive sampling. If this was done in our cohort 18.7% (95% CI 15.1%‐22.8%) of the patients would receive a diagnosis already in pregnancy (Table 2), whereas when subsequent testing was employed the mean time until final diagnosis was 271 days after invasive testing. This is partially due to incompleteness of the fetal phenotype (targeted tests could be requested after birth or termination of pregnancy), subsequential character of testing (first targeted test, then broader test) and due to the parental requests to postpone the additional testing. In our cohort the large majority of cases (90.8%) underwent invasive sampling before the 24th week of gestation and early diagnosis by prenatal WES would likely contribute to the decision on continuation of pregnancy.

A systematic literature review revealed a broad range (6.2%‐80%) of diagnostic yield in fetuses with structural anomalies across 16 studies published in the period 2014‐2017. 14 Many of these studies included either severe multiple fetal anomalies or the families were highly selected (multiple affected fetuses, high percentage of consanguinity, selected type of anomalies). 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 The high diagnostic yield of Alamillo et al (42.9%), Pangalos et al (42.9%) and Vora et al (46.7%) reflects the inclusion of fetuses with multiple congenital anomalies. 15 , 21 , 22 Careful selection by clinical geneticists indeed results in a very high diagnostic yield. 23 Our study confirms that the potential diagnostic yield of WES in fetuses with multiple system anomalies is higher (29%, 95% CI 20.8%‐38.9%) than the estimated yield in the group of (isolated) single system anomalies; however, the group of isolated anomalies showed a substantial percentage of abnormal cases (16.7%, 95% CI 12.6%‐21.8%). These results suggest that also fetuses with an isolated anomaly could be offered prenatal WES testing and confirms that patient selection based on the prenatal phenotype may be challenging. 24

The cohort selection may be the major reason for the large variation in the incidence of pathogenic WES findings in the cohorts published so far in the literature. In our cohort with a wide range of phenotypes that are typically seen in the clinic cohort, 18.7% (95% CI 15.1%‐22.8%) of patients showed DNA variants that could have been detected by WES. Although WES was not performed in all cases, our results are similar to the percentage found by Fu et al 25 Due to our cohort size and the subgroups of fetal anomalies, our estimated diagnostic yield showed a relatively wide confidence interval in some cases, which indicates that these estimates should be interpreted with caution. The large prospectively tested cohorts that have recently been published by Lord et al 26 and Petrovski et al 27 show lower prevalence of pathogenic findings (8.5% and 10%, respectively). Neither cohort was selected by clinical geneticists and patients were invited to participate after ultrasound anomalies were found. These studies confirm that in unselected fetuses with ultrasound anomalies the diagnostic yield of WES testing is high enough to conclude that prenatal WES would be of great clinical value if offered simultaneously with chromosomal microarray.

In our cohort, some of the fetuses had ultrasound anomalies suggestive for a known genetic disease for which rapid standard targeted testing is available, for example, cystic fibrosis and Noonan syndrome. Therefore, one could consider employing a targeted test first to exclude certain disorders. However, when there is a legal limit for termination of the pregnancy it may not be feasible to first request a targeted test and if that is normal then to proceed with WES. Therefore, we have hypothesized that it might be interesting to consider replacing all targeted tests in pregnancy with WES and obtain diagnosis of all syndromes possibly detected by WES in one test as early as possible. In the Netherlands, the legal limit for pregnancy termination is the 24th week of gestation and therefore only if the fetus is sampled in the first trimester would first a targeted test and then subsequent WES testing be feasible. In our cohort, only testing for Noonan syndrome (in the first or early second trimester in cases with neck anomalies) would be feasible before WES request. In our cohort among 79 cases with apparently isolated nuchal translucency, three cases of Noonan syndrome were detected, therefore we hypothesize that in the first trimester the dedicated Noonan NGS panel could be performed and then only in cases showing additional anomalies, WES analysis could follow in the second‐trimester. However, although such a two‐step procedure is feasible in the first trimester, it is unfavorable for patients who wish to receive a final diagnosis as soon as possible.

While offering prenatal WES testing, we should be aware of its technical limitations. These technical limitations imply that repeat expansions will not be detected and small (one or two) exon deletions and single nucleotide variants in poorly covered regions may be missed. 28 As shown in this study, methylation disorders will remain undetected as well. Prenatal WES can detect many syndromes, but certainly cannot exclude all genetic diseases, which should be addressed in pre‐ and posttest counseling.

Another limitation is the incomplete fetal phenotype as determined by prenatal imaging. In some cases variants may remain of unknown significance until more phenotypic data become available after birth. For this reason, during pregnancy, it may be difficult to conclude that the genotype is causal, especially if the variant is previously not described. Lord et al. presented several genes identified in their cohort that had diagnostic variants without previous prenatal phenotype descriptions. 26

The possibility of re‐interpretation of variants after more data become available should be discussed during pretest counseling as well. Efforts to share genotypes and prenatal phenotypes in databases should be made to further reduce the uncertainty related to several genetic variants and facilitate data interpretation. Because of the incomplete fetal phenotype, more studies are necessary to assess which approach is the most suitable in the prenatal setting: WES or a specific broad gene panel analysis.

An often‐discussed issue of any whole genome testing is the possibility of reporting the so‐called unexpected diagnoses or incidental findings that seem to be unrelated to the initial indication. In our cohort only one unexpected diagnosis was made and it concerned an early onset disorder. Unexpected diagnoses are not new in the context of prenatal testing, as it is known from the era of karyotyping as well as chromosomal microarray, but proper pretest counseling should always be provided, so that the unexpected character of such a finding can be reduced. 29

The retrospective character of this data analysis is the major limitation. The percentages of cases with a genetic diagnosis are based on different tests that were performed in different stages of pregnancy or after delivery. A large number of cases proceeded only to targeted sequencing (n = 232) which may cause underestimation of the number of abnormal fetal cases. Broad molecular testing was performed in some cases (n = 159), where potentially an underlying monogenetic disorder could be identified and where parents wished to proceed with further diagnostics. Some of the patients refused to proceed to molecular testing if the results were not available before the 24th week of gestation. Therefore, the presented data may differ from cohorts prospectively tested with WES.

5. CONCLUSION

Our retrospective cohort study shows that WES, if routinely offered by a clinical geneticist to patients in a prenatal setting, would significantly increase the diagnostic yield. Prenatal WES could lead to early diagnosis of a genetic disorder in a significant percentage of cases irrespective of the (incomplete) fetal phenotype. We assumed that only when an anomaly is detected in the first trimester, it may be feasible to request targeted tests before broad genetic testing, otherwise there may not be time to perform subsequent panel or whole exome analysis (if there is a legal limit for terminating an affected pregnancy).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Diderich KEM, Romijn K, Joosten M, et al. The potential diagnostic yield of whole exome sequencing in pregnancies complicated by fetal ultrasound anomalies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:1106–1115. 10.1111/aogs.14053

Marieke Joosten and Lutgarde C. P. Govaerts contributed equally to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hillman SC, Willams D, Carss KJ, McMullan DJ, Hurles ME, Kilby MD. Prenatal exome sequencing for fetuses with structural abnormalities: the next step. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45:4‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kenkhuis MJA, Bakker M, Bardi F, et al. Effectiveness of 12–13‐week scan for early diagnosis of fetal congenital anomalies in the cell‐free DNA era. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51:463‐469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics; Committee on Genetics; Society for Maternal‐Fetal Medicine . Practice Bulletin No. 162: Prenatal Diagnostic Testing for Genetic Disorders. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e108‐e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Wit MC, Srebniak MI, Govaerts LC, Van Opstal D, Galjaard RJ, Go AT. Additional value of prenatal genomic array testing in fetuses with isolated structural ultrasound abnormalities and a normal karyotype: a systematic review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2014;43:139‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Srebniak MI, Knapen MFCM, Polak M, et al. The influence of SNP‐based chromosomal microarray and NIPT on the diagnostic yield in 10,000 fetuses with and without fetal ultrasound anomalies. Hum Mutat. 2017;38:880‐888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borghesi A, Mencarelli MA, Memo L, et al. Intersociety policy statement on the use of whole‐exome sequencing in the critically ill newborn infant. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tetreault M, Bareke E, Nadaf J, Alirezaie N, Majewski J. Whole‐exome sequencing as a diagnostic tool: current challenges and future opportunities. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:749‐760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405‐424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Plon SE, Eccles DM, Easton D, et al. Sequence variant classification and reporting: recommendations for improving the interpretation of cancer susceptibility genetic test results. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:1282‐1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shaffer LG, Rosenfeld JA, Dabell MP, et al. Detection rates of clinically significant genomic alterations by microarray analysis for specific anomalies detected by ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:986‐995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raniga S, Desai PD, Parikh H. Ultrasonographic soft markers of aneuploidy in second trimester: are we lost? Med Gen Med. 2006;8:9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci. 2001;16:101‐117. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Srebniak MI, Diderich KEM, Govaerts LCP, et al. Types of array findings detectable in cytogenetic diagnosis: a proposal for a generic classification. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:856‐858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Best S, Wou K, Vora N, Van der Veyver IB, Wapner R, Chitty LS. Promises, pitfalls and practicalities of prenatal whole exome sequencing. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:10‐19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alamillo CL, Powis Z, Farwell K, et al. Exome sequencing positively identified relevant alterations in more than half of cases with an indication of prenatal ultrasound anomalies. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35:1073‐1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Al‐Hamed MH, Kurdi W, Alsahan N, et al. Genetic spectrum of Saudi Arabian patients with antenatal cystic kidney disease and ciliopathy phenotypes using a targeted renal gene panel. J Med Genet. 2016;53:338‐347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rasmussen M, Sunde L, Nielsen ML, et al. Targeted gene sequencing and whole‐exome sequencing in autopsied fetuses with prenatally diagnosed kidney anomalies. Clin Genet. 2018;93:860‐869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boissel S, Fallet‐Bianco C, Chitayat D, et al. Genomic study of severe fetal anomalies and discovery of GREB1L mutations in renal agenesis. Genet Med. 2018;20:745‐753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Wit MC, Boekhorst F, Mancini GM, et al. Advanced genomic testing may aid in counseling of isolated agenesis of the corpus callosum on prenatal ultrasound. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37:1191‐1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filges I, Friedman JM. Exome sequencing for gene discovery in lethal fetal disorders—harnessing the value of extreme phenotypes. Prenat Diagn. 2015;35:1005‐1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pangalos C, Hagnefelt B, Lilakos K, Konialis C. First applications of a targeted exome sequencing approach in fetuses with ultrasound abnormalities reveals an important fraction of cases with associated gene defects. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vora NL, Powell B, Brandt A, et al. Prenatal exome sequencing in anomalous fetuses: new opportunities and challenges. Gen Med. 2017;19:1207‐1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Becher N, Andreasen L, Sandager P, et al. Implementation of exome sequencing in fetal diagnostics—Data and experiences from a tertiary center in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99:783‐790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diderich K, Joosten M, Govaerts L, et al. Is it feasible to select fetuses for prenatal WES based on the prenatal phenotype? Prenat Diagn. 2019;39:1039‐1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fu F, Li R, Li Y, et al. Whole exome sequencing as a diagnostic adjunct to clinical testing in fetuses with structural abnormalities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018;51:493‐502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lord J, McMullan DJ, Eberhardt RY, et al. Prenatal exome sequencing analysis in fetal structural anomalies detected by ultrasonography (PAGE): a cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:747‐757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Petrovski S, Aggarwal V, Giordano JL, et al. Whole‐exome sequencing in the evaluation of fetal structural anomalies: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;393:758‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meienberg J, Bruggmann R, Oexle K, Matyas G. Clinical sequencing: is WGS the better WES? Hum Genet. 2016;135:359‐362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Joosten M, Diderich KE, Van Opstal D, et al. Clinical experience of unexpected findings in prenatal array testing. Biomark Med. 2016;10:831‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material