Abstract

Introduction

We aimed to give a global overview of trends in access to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and what is being done to mitigate its impact.

Material and methods

We performed a descriptive analysis and content analysis based on an online survey among clinicians, researchers, and organizations. Our data were extracted from multiple‐choice questions on access to SRHR services and risk of SRHR violations, and written responses to open‐ended questions on threats to access and required response.

Results

The survey was answered by 51 people representing 29 countries. Eighty‐six percent reported that access to contraceptive services was less or much less because of COVID‐19, corresponding figures for surgical and medical abortion were 62% and 46%. The increased risk of gender‐based and sexual violence was assessed as moderate or severe by 79%. Among countries with mildly restrictive abortion policies, 69% had implemented changes to facilitate access to abortion during the pandemic, compared with none among countries with severe restrictions (P < .001), 87.5% compared with 46% had implemented changes to facilitate access to contraception (P = .023). The content analysis showed that (a) prioritizations in health service delivery at the expense of SRHR, (b) lack of political will, (c) the detrimental effect of lockdown, and (d) the suspension of sexual education, were threats to SRHR access (theme 1). Requirements to mitigate these threats (theme 2) were (a) political will and support of universal access to SRH services, (b) the sensitization of providers, (c) free public transport, and (d) physical protective equipment. A contrasting third theme was the state of exception of the COVID‐19 pandemic as a window of opportunity to push forward women's health and rights.

Conclusions

Many countries have seen decreased access to and increased violations of SRHR during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Countries with severe restrictions on abortion seem less likely to have implemented changes to SRHR delivery to mitigate this impact. Political will to support the advancement of SRHR is often lacking, which is fundamental to ensuring both continued access and, in a minority of cases, the solidification of gains made to SRHR during the pandemic.

Keywords: abortion, access, contraceptives, coronavirus disease 2019, gender‐based violence, sexual and reproductive health and rights

Abbreviations

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- FGM

female genital mutilation

- GBV

gender‐based violence

- SRHR

sexual and reproductive health and rights

- SV

sexual violence

Key Message.

Our survey supports that the COVID‐19 pandemic has had a global negative impact on many aspects of sexual and reproductive health and rights. It has most severely impacted those women who already suffer from lack of access to these needs and rights.

1. INTRODUCTION

Ensuring access to sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) is fundamental to reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, reducing poverty, and increasing equality. 1

Humanitarian crisis, conflict situations, and displacement exacerbate preexisting vulnerabilities and lack of access and rights, and women and children are often the first to suffer the consequences of jeopardized infrastructure and systems. 2 , 3 , 4 The current pandemic has led to a restructuring of healthcare services to meet the demands of the infection with disruptions of reproductive maternal and neonatal health services. 5 Lockdown measures taken to limit the spread of the virus have implications for human rights, acutely so for many women at risk of domestic violence. 6 , 7

This survey provides a quantitative and qualitative account of the impact of the pandemic on SRHR through the voices of providers, researchers, and organizations on the ground working towards advancing women's health and rights.

Our aim was to give a global overview of trends in access to SRHR during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, and how this is impacting different regions of the world, and to understand what is being done to mitigate decrease in access and utilization of services.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

We performed a multi‐methods study based on an anonymous online survey sent out to the network of the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) committee on Human Rights, Refugees, and Violence Against Women. The survey was sent out to 135 respondents from 62 countries between 8 and 11 May 2020 and closed on 30 May 2020. Respondents were invited to snowball the survey to other respondents who they thought would be representative of SRHR in their region. The committee developed the survey content based on a previous instrument mapping abortion and contraception access that we helped to create. The survey asked respondents to categorically assess the impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on access to abortion and contraceptive services, gender‐based violence (GBV), sexual violence (SV), female genital mutilation (FGM), and child marriage, and on the services that respond to these violations. In two open‐ended questions, the survey also asked respondents to qualify the current threats to SRHR and the measures that were required to mitigate these threats.

2.1. Quantitative analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the categorical data. In a subanalysis we grouped responding countries according abortion policy: (a) those with no or mild restrictions on access to abortion and (b) those with severe restrictions on access to abortion. The first group included both countries where abortion was available without restrictions up to 12 gestational weeks or more, and where it was available with some degree of restriction such as gestational age limit below 12 weeks, socioeconomic indication for abortion, mandatory waiting period, or two‐doctor assessment. In the second group, abortion was allowed only in case of threat to the woman's physical health or life, fetal abnormality, rape, or incest. For countries for which there were multiple respondents, we chose the median or most common response for each answer so that each country was represented by only one respondent in the analysis. We summarized data as the numbers and percentages of each response category, including missing data. Group‐based analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test and excluding missing data. P values <.05 were considered significant.

2.2. Qualitative component

We performed a content analysis of the responses and comments received to the following two open‐ended questions:

In your own words, what are the main threats to SRHR for women in your country/region resulting from the current pandemic and why.

What would be required by clinical providers, policy‐makers and/or SRHR organizations to address these threats?

All responses with coherent text were analyzed, no sampling was performed. Overarching themes were established in an overall reading. Subsidiary categories relating to each theme were established through repeated reading, revision, and coding of the text. The content analysis was performed at the manifest level, meaning that the content was interpreted based on its apparent meaning.

2.3. Ethical approval

Respondents were informed that data from the survey would be used in a scientific report. Respondents were anonymous and no personal data, or data of a personal nature were recorded.

Advisory opinion and exemption from ethical review was obtained from the Karolinska Institutet Ethics Committee (DNR 2020‐04736) on 20 October 2020.

3. RESULTS

Through the combined effect of survey invitations and snowballing, the survey reached 149 people representing 62 countries. The survey was answered by 51 people representing 29 countries from Europe (n = 11), North America (n = 2), South America (n = 4), Africa (n = 4), Asia (n = 6), and Australia/Oceania (n = 2). The overall response rate among countries represented was 46.9%. Response rate varied between regions from 33.3% (Africa) to 100% (Australia/Oceania). The geographic representation and response rate of the survey is available in Supporting Information (Table S1).

Thirteen countries had highly restrictive abortion care policies, and 16 had mildly restrictive abortion care policies of which half allowed for abortion without restriction up to 12 weeks' gestation or more, and half placed some dependent criteria on abortion access on demand. Abortion care guidelines existed in 20 out of 29 countries (69%). Respondents were clinical providers (25.5%), SRHR organizations (13.7%), academics (11.8%), policy‐makers (2%), or clinical providers and one of the above categories (47.1%).

3.1. Descriptive analysis

Reported changes in access to abortion, contraceptives, GBV/SV services, FGM services, and child marriage prevention are shown in Figure 1. Out of all respondents, 86% reported that access to contraceptive services was less or much less because of the COVID‐19 pandemic, corresponding figures for surgical and medical abortion were 62% and 46%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on access to sexual and reproductive health and rights services in 29 countries according to a global survey. FGM, female genital mutilation; GBV, gender‐based violence services; LARC, long‐acting reversible contraception; SV, sexual violence services [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

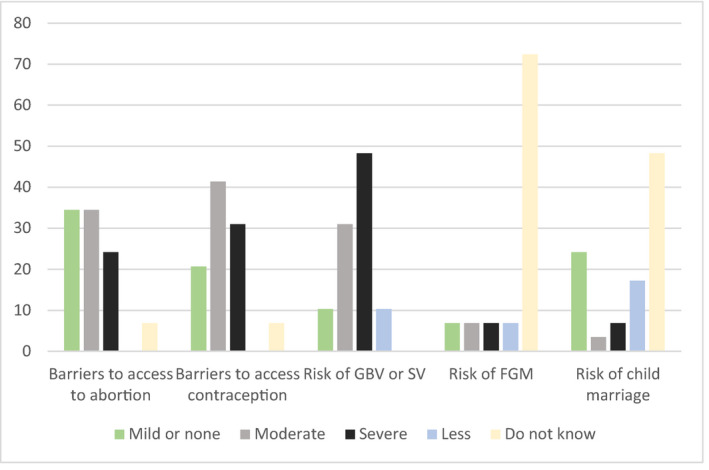

Respondents assessed that the combined effect of barriers on access to abortion and contraceptive services were moderate or severe in 59% and 72% of cases, respectively (Figure 2). The increased risk of GBV during the pandemic was reported as moderate or severe by 79% of respondents. A majority reported that FGM and child marriage were not SRHR violations applicable to their represented country.

Figure 2.

Assessment of barriers to access to sexual and reproductive health and rights services, and risk of sexual and reproductive health and rights violations, due to the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic among 29 countries in a global survey. FGM, female genital mutilation; GBV, gender‐based violence; SV, sexual violence [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

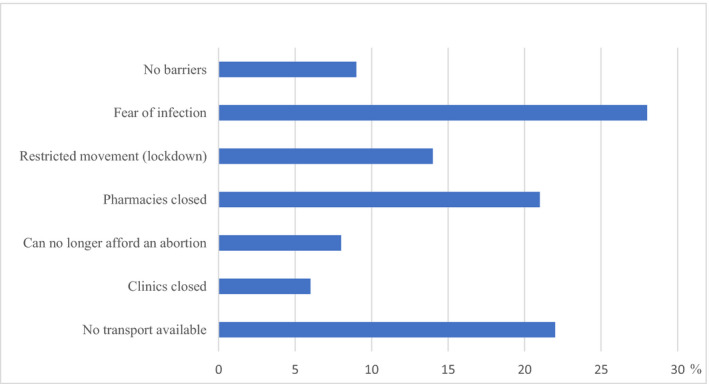

The most frequent stated reasons that women were not seeking abortion services were fear of infection, lack of transport, closure of clinics, and a fear to leave the house because of lockdown restrictions (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Perceived barriers to access to abortion due to the effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic in 29 countries according to a global survey [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. Subanalysis according to abortion restrictions

Countries with severely restrictive abortion policies tended towards decreased access to abortion during the pandemic, in particular for COVID‐19‐positive women, but there was no significant difference between groups (Table 1). These countries were, however, more likely to report that women were not coming to the clinics as usual (P = .026).

Table 1.

Effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on access to abortion and contraceptive services according to preexisting restrictions on abortion

| Impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on access | Abortion policy | Fisher’s exact test | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mildly restrictive (n = 16) number (%) |

Severely restrictive (n = 13) number (%) |

P value | |

| Abortion access | |||

| No effect | 10 (62.5) | 5 (38.5) | .153 |

| Less access | 3 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Much less access | 2 (12.5) | 6 (46.1) | |

| Do not know | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Access for COVID‐19‐positive women | |||

| No effect | 7 (43.8) | 1 (7.7) | .171 |

| Less access | 5 (31.2) | 3 (23.1) | |

| Much less access | 3 (18.7) | 5 (38.4) | |

| Do not know | 1 (6.3) | 4 (30.8) | |

| Are women coming as before? | |||

| Yes | 11 (68.8) | 3 (23.1) | .026 |

| No | 4 (25.0) | 8 (61.5) | |

| Do not know | 1 (6.2) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Access to family planning | |||

| No change | 3 (18.8) | 1 (7.7) | .662 |

| Less access | 9 (56.2) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Much less access | 4 (25.0) | 5 (38.4) | |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | |

Among countries with mildly restrictive abortion policies, 11 (69%) had implemented changes to facilitate access to abortion in response to the pandemic. No country where abortion was severely restricted before the pandemic had instituted any change toward improving access during the pandemic (P < .001). Among countries with mildly restrictive abortion policies, 14 (87.5%) had implemented changes to facilitate access to contraception compared with 6 (46%) of the countries with severe restrictions (P = .023). Policy changes made to mitigate the threat of reduced access were the implementation of telemedicine consultation for abortion or contraceptives, a decrease in number of required visits for medical abortion, changes in the requirement of ultrasound, allowance of over‐the‐counter mifepristone, intake at home, changes to gestational age limits for abortion, and over‐the‐counter provision of contraceptives with home monitoring of blood pressure after initiation of combined hormonal methods, as well as prolonged use of long‐acting reversible contraception such as implants and intrauterine devices (Table 2). Abortion and contraceptive policy changes by country are presented in Supporting Information (Tables S2 and S3).

Table 2.

Policy changes in abortion and family planning services in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic according to preexisting restrictions on abortion

| Policy changes in response to the pandemic | Abortion policy | Fisher’s exact test | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Mildly restrictive (n = 16) number (%) |

Severely restrictive (n = 13) number (%) |

P value | |

| Abortion care policy change | |||

| Yes | 11 (68.8) | 0 (0) | <.001 |

| No | 5 (31.2) | 13 (100) | |

| Type of policy change (n = 11) | |||

| Number of visits required | 6 (37.5) | None | |

| Gestational age limit increased | 4 (25.0) | None | |

| Home abortion facilitated | 6 (37.5) | None | |

| Dispensation of mifepristone facilitated | 4 (25.0) | None | |

| Telemedicine allowed | 8 (50.0) | None | |

| Contraceptive services policy change | |||

| Yes | 14 (87.5) | 6 (46.2) | .023 |

| No | 2 (12.5) | 7 (53.9) | |

| Type of policy change (n = 20) | |||

| Telemedicine consultation allowed | 13 (81.3) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Over‐the‐counter contraceptives permitted | 1 (6.3) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Amended in‐clinic services available | 7 (43.8) | 2 (15.4) | |

3.3. Content analysis

Forty‐five out of 51 respondents replied to the questions that informed the content analysis. The text responses varied in length (3‐270 words), median word count was 45 per respondent, including additional comments, and 21 per response. Saturation was assessed to have been achieved after 30 responses. We identified three main themes and eight subcategories subsidiary to these themes:

-

1.

Threats to SRHR access

-

1.1

Prioritizations made in health service delivery at the expense of SRHR

-

1.2

Lack of political will

-

1.3

The detrimental effect of lockdown

-

1.4

The suspension of sexual education

-

1.1

-

2.

Requirements to mitigate the threat to SRHR

-

2.1

Political will and support to facilitate access

-

2.2

Sensitization of providers of women's needs and rights

-

2.3

Free public transport

-

2.4

Physical protective equipment for providers

-

2.1

-

3.

Opportunities provided by the COVID‐19 pandemic

-

3.1

State of exception as a window of opportunity to push forward women's health and rights

-

3.1

Most respondents described an overall decrease in access to SRHR services because of the prioritization of the pandemic response, and that access was often a result of initiatives from individual organizations or clinicians.

The biggest threat is that attention has been focussed only on COVID‐19 patients. Outpatient sexual and reproductive health care has been suspended in hospitals. In public sector hospitals and health centers, there are no obstetric, gynecological, or family planning consultations. (Peru)

No involvement from the health authorities to guarantee access to abortion and contraception. The clinical providers organized themself to guarantee access to abortion. (Portugal)

Several respondents described a scenario where SRHR were already lacking because of a lack of political will to advance women's rights, and that the current pandemic was an excuse to pause, ignore, or dismantle progress made towards increasing SRHR.

Family planning services (are) closed during pandemic, hospitals are dedicated to COVID‐19 patients, (…) every excuse to work against abortion. (Italy)

Lack of political will and support where SRHR matters are concerned. Limited funds to those willing to implement interventions. Poverty pushing some negative decisions. (Kenya)

They should take care of these issues. But they do not! (Poland)

Multifactorial threats to SRHR as a result of lockdown restrictions were described in the answers, consisting of absolute barriers such as lack of finances, lack of transport, and closure of clinics, as well as qualitative barriers such as fear of infection, restricted movement, and increased stigma related to seeking abortion and contraceptive services. Many respondents stressed the vulnerability of women and children.

COVID‐19 has increased the burden on women and children. It has highlighted to what extent women and children have been neglected despite the signing of various conventions. (South Africa)

The requirements needed to meet the threats to SRHR reflected the threats reported in the first question. Respondents called primarily for increased government response, will, and accountability for universal access to abortion and contraceptive services. The policy changes that were called for were the provision of outpatient abortion services, allowance for home medical abortion, increased gestational age limits, increased sexual education at schools, and the facilitation of abortion and contraceptive services through telemedicine.

(We need) the political and medical (…) will to provide free contraception, over‐the‐counter contraception and early medical abortion. (New Zealand)

Thinking about innovative measures in dealing with current status, such as remote approaches (telephone, digital applications, SMS text messaging, voice calls, interactive voice response) whenever applicable. (Iraq)

The need for providers to become sensitized to women's needs and rights was also a recurring topic.

Clinical providers should be trained in unconscious bias and non‐judgemental engagement with clients and ensuring consumer choices in contraception. (Lebanon)

In contrast, some respondents (notably from England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) described that the state of exception that the pandemic represented had provided them with a window to push forward women's abortion rights and that decreased access had been mitigated or even reversed as a result. Some were hopeful that these changes would be made permanent, but others feared that advances would be retracted when the pandemic was over.

We are treating up to 20% more women than usual. Women who previously turned to illegal online pill providers (…) are no longer doing so because they can access medication over the telephone via legal means. The pandemic has provided the means for a huge step forward in provision (…) and we will be aiming to keep this in place long term. (United Kingdom)

As a result of [COVID‐19] we have been able to set up a temporary medical abortion service for first time but not funded or commissioned and will prob stop after things return to normal. (Northern Ireland)

Other responses described how advances were made in the private sector but that the public sector was falling behind.

Teleconsultations are being carried out; however especially in the public sector where people are less prepared, access (…) is limited. (Peru)

4. DISCUSSION

Our results indicate that changes that are occurring in healthcare delivery and health‐seeking behavior in response to the COVID‐19 pandemic are having an overall negative impact on SRHR. Countries that had preexisting severe restrictions on abortion were less likely to have implemented changes to abortion and contraception delivery to mitigate this impact compared with countries with more liberal policies.

Most countries represented in the survey had seen an overall decrease in access to abortion, contraceptive, and GBV/SV support services, despite the fact that access to these services may have been highly restricted before the pandemic. The qualitative analysis of responses showed a consensus around the fact that political will to support the advancement of SRHR was often lacking, and that this will was fundamental to ensuring both continued access during the pandemic and, in a minority of cases, the solidification of gains made to SRHR during the crisis. This lack of political will also works to exacerbate inequalities between private and public health services, where advances can be made in the independent health sector that benefit mostly women of increased financial means.

The decrease in access to SRH services has been previously reported. 8 Our survey also suggests that the extent to which the pandemic has impacted SRHR may correlate inversely with the extent to which these services and rights were available before the pandemic. It is likely that countries that gave SRHR low prioritization before the pandemic continued to make SRHR a low priority during the pandemic. The COVID‐19 pandemic has in that case most severely impacted the SRHR of women who already suffer from lack of access to these needs and rights.

Consistent across settings and respondents was the assessment that the risk of GBV and SV had increased significantly as a result of the the pandemic but that access to GBV and SV services had simultaneously decreased. The increased occurrence of GBV during the pandemic has been reported by multiple previous studies and reports. 7 , 9 Indications that GBV and SV services are simultaneously discontinued is of great concern. These services urgently need to be scaled up to meet increased demand.

Respondents in the study recognized several factors related to the pandemic as well as to the effects of lockdown that hindered women from accessing and utilizing services; the qualitative analysis nuanced these responses by showing that it was often the simultaneous effects of fear, less income, and disrupted transport and health services that kept women away. Universal access to SRHR occurs only in the joint presence of several factors: knowledge and empowerment on the part of women, willing providers, legal prerequisites, and available services. 10 , 11 , 12 Recognizing that access depends on multiple variables is important to understand how access can be lost through a combination of small changes.

Our sample size and geographical representation were not designed to quantify the effect of the pandemic on SRHR but to qualify the direction and underlying reasons for these changes. Our study should therefore only be considered a rapid and momentary appraisal of the current global situation in relation to SRHR. The survey was performed at a time when countries had highly varying levels of infection, something which the analysis does not adjust for. Levels of lockdown restrictions and healthcare restructuring, which are arguably more likely to impact SRHR, were however similar. European respondents were somewhat overrepresented in the initial survey invitation, which was made more pronounced by the effect of snowballing, the survey does, however, have representatives from all the main regions of the world. In a statistical model, the United Nations Population Fund has estimated that the combined effect of the pandemic and a 12‐month lockdown could result in an additional 15 million unintended pregnancies, 13 million cases of child marriage, 2 million cases of FGM, and 60 million cases of GBV. 13

In meeting the increased demands on services posed by the pandemic it is essential to not dismantle services that are essential to maternal health, the absence of which will have implications for a whole generation of women and their children, families, and society, far beyond the course of the pandemic.

5. CONCLUSION

Many countries have seen decreased access to services and increased violations of SRHR during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Countries that had preexisting severe restrictions on abortion seem less likely to have worked towards facilitating access to abortion and contraception to mitigate this impact than countries with more liberal policies, which indicates that the COVID‐19 pandemic has most severely impacted women who already suffer from a lack of access to these SRHR services. Political will to support the advancement of SRHR is often lacking, and this is fundamental to ensuring both continued access during the pandemic and, in a minority of cases, the solidification of gains made in SRHR during the crisis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2‐S3

Endler M, Al‐Haidari T, Benedetto C, et al. How the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights and response: Results from a global survey of providers, researchers, and policy‐makers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand.2021;100:571–578. 10.1111/aogs.14043

REFERENCES

- 1. Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher‐Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2018;391:2642‐2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pugh S. Politics, power, and sexual and reproductive health and rights: impacts and opportunities. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27:1662616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heidari S, Onyango MA, Chynoweth S. Sexual and reproductive health and rights in humanitarian crises at ICPD25+ and beyond: consolidating gains to ensure access to services for all. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2019;27:1676513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. UNFPA . Maternal Mortality in Humanitarian crisis and fragile settings. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource‐pdf/MMR_in_humanitarian_settings‐final4_0.pdf (accessed 15th Jan 2020). 2015.

- 5. World Health Organization . COVID‐19 significantly impacts health services for noncommunicable diseases. June 1st 2020. https://www.who.int/news‐room/detail/01‐06‐2020‐covid‐19‐significantly‐impacts‐health‐services‐for‐noncommunicable‐diseases (accessed June 8th 2020).

- 6. Human Rights Watch, Human Rights Dimensions of COVID‐19 Response, March 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/19/human‐rights‐dimensions‐covid‐19‐response (accessed June 9th 2020).

- 7. UN Women, COVID‐19 and Ending Violence Against Women and Girls, 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/‐/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2020/issue‐brief‐covid‐19‐and‐ending‐violence‐against‐women‐and‐girls‐en.pdf?la=en&vs=5006 (accessed June 8th 2020).

- 8. Tang K, Gaoshan J, Ahonsi B, et al. Sexual and reproductive health (SRH): a key issue in the emergency response to the coronavirus disease (COVID‐ 19) outbreak. Reprod Health. 2020;17:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. UNDP . UNDP brief. Gender Based Violence and Covid 19. 2020. file:///C:/Users/margi/Downloads/undp‐gender‐GBV_and_COVID‐19%20(2).pdf (accessed June 8th 2020).

- 10. Benson J. Evaluating abortion‐care programs: old challenges, new directions. Stud Fam Plann. 2005;36:189‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization . Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems, 2nd edn. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization . Health worker roles in providing safe abortion care and post‐abortion contraception. Geneva: WHO; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. UNFPA . Impact of the COVID‐19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender‐based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage. 27 April 2020. https://gbvguidelines.org/wp/wp‐content/uploads/2020/05/Impact‐of‐the‐COVID‐19‐Pandemic‐on‐Family‐Planning‐and‐Ending‐Gender‐based‐Violence‐Female‐Genital‐Mutilation‐and‐Child‐Marriage‐EN.pdf (accessed June 8th 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2‐S3