Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular comorbidities may predispose to adverse outcomes in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). However, across the USA, the burden of cardiovascular comorbidities varies significantly. Whether clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 differ between regions has not yet been studied systematically. Here, we report differences in underlying cardiovascular comorbidities and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Texas and in New York state.

Methods

We established a multicenter retrospective registry including patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between March 15 and July 12, 2020. Demographic and clinical data were manually retrieved from electronic medical records. We focused on the following outcomes: mortality, need for pharmacologic circulatory support, need for mechanical ventilation, and need for hemodialysis. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed.

Results

Patients in the Texas cohort (n = 296) were younger (57 vs. 63 years, p value <0.001), they had a higher BMI (30.3 kg/m<sup>2</sup> vs. 28.5 kg/m<sup>2</sup>, p = 0.015), and they had higher rates of diabetes mellitus (41 vs. 30%; p = 0.014). In contrast, patients in the New York state cohort (n = 218) had higher rates of coronary artery disease (19 vs. 10%, p = 0.005) and atrial fibrillation (11 vs. 5%, p = 0.012). Pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis were more frequent in the Texas cohort (21 vs. 13%, p = 0.020; 30 vs. 12%, p < 0.001; and 11 vs. 5%, p = 0.009, respectively). In-hospital mortality was similar between the 2 cohorts (16 vs. 18%, p = 0.469). After adjusting for differences in underlying comorbidities, only the use of mechanical ventilation remained significantly higher in the participating Texas hospitals (odds ratios [95% CI]: 3.88 [1.23, 12.24]). Median time to pharmacologic circulatory support was 8 days (interquartile range: 2, 13.8) in the Texas cohort compared to 1 day (0, 3) in the New York state cohort, while median time to in-hospital mortality was 16 days (10, 25.5) and 7 days (4, 14), respectively (both p < 0.001). In-hospital mortality was higher in the late versus the early study phase in the New York state cohort (24 vs. 14%, p = 0.050), while it was similar between the 2 phases in the Texas cohort (16 vs. 15%, p = 0.741).

Conclusions

Geographical differences, including practice pattern variations and the impact of disease burden on provision of health care, are important for the evaluation of COVID-19 outcomes. Unadjusted data may cause bias affecting future regulatory policies and proper allocation of resources.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Texas, New York, Cardiovascular comorbidities, Mortality, Clinical outcomes

Introduction

Since its emergence 1 year ago, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has spread rapidly worldwide, resulting in over 86 million cases and close to 2 million deaths at the time of writing the manuscript [1]. Underlying cardiovascular comorbidities are important predisposing factors to an unfavorable outcome [2, 3, 4, 5]. Large disparities in the burden of cardiovascular comorbidities have been reported between different regions of the USA [6]. Texas and New York are states with unique demographic characteristics and prevalence of cardiovascular disease among their residents [7, 8]. Whether clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are different between regions in the USA has not yet been studied systematically. Our study addresses differences in underlying cardiovascular comorbidities and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in selected hospitals of Texas and New York state.

Methods

Patient Population and Data Collection

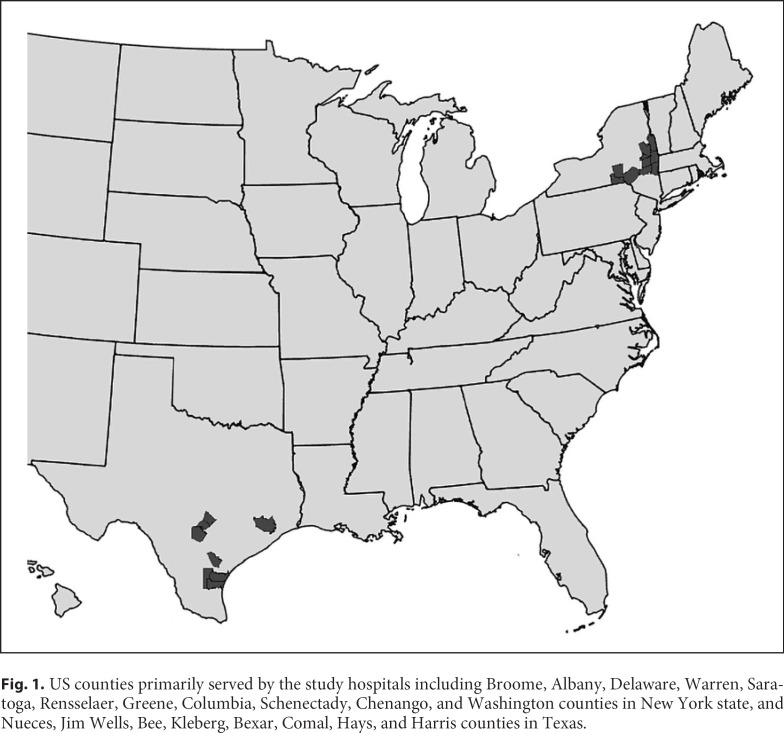

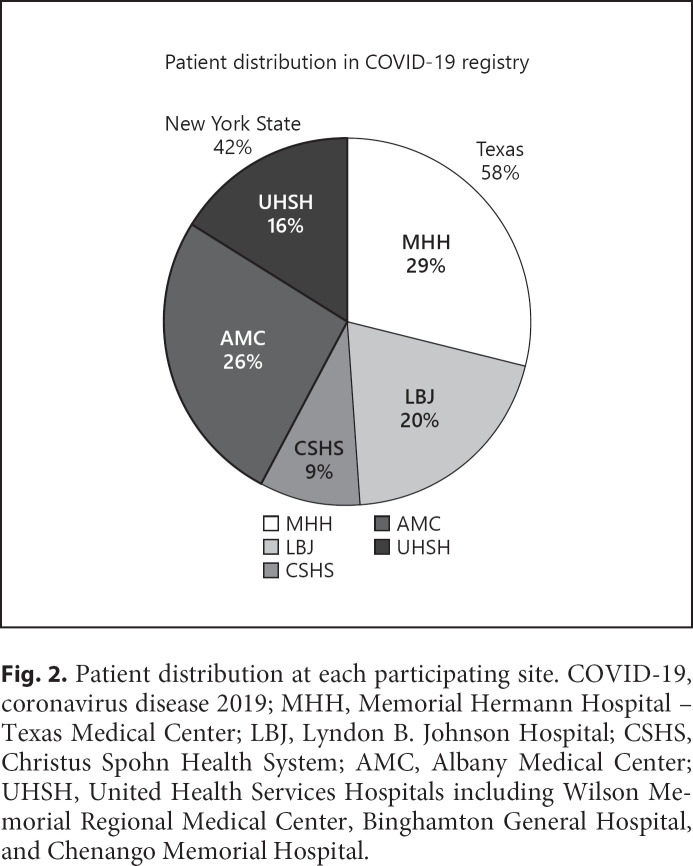

We established a multicenter retrospective registry of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the states of Texas and New York between March 15 and July 12, 2020. Participating hospitals included the Memorial Hermann Hospital-Texas Medical Center; Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital in Houston, TX, USA; Christus Spohn Health System in Corpus Christi, TX, USA; Albany Medical Center in Albany, NY, USA; and 3 United Health Services Hospitals in New York, Wilson Memorial Regional Medical Center in Johnson City, Binghamton General Hospital in Binghamton, and Chenango Memorial Hospital in Norwich. Figure 1 shows the US counties primarily served by the study hospitals and Figure 2 shows the patient distribution at each site.

Fig. 1.

US counties primarily served by the study hospitals including Broome, Albany, Delaware, Warren, Saratoga, Rensselaer, Greene, Columbia, Schenectady, Chenango, and Washington counties in New York state, and Nueces, Jim Wells, Bee, Kleberg, Bexar, Comal, Hays, and Harris counties in Texas.

Fig. 2.

Patient distribution at each participating site. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; MHH, Memorial Hermann Hospital − Texas Medical Center; LBJ, Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital; CSHS, Christus Spohn Health System; AMC, Albany Medical Center; UHSH, United Health Services Hospitals including Wilson Memorial Regional Medical Center, Binghamton General Hospital, and Chenango Memorial Hospital.

Hospital registries and hospitalization billing codes were used to identify consecutive patients admitted with COVID-19. All patients had laboratory confirmation of infection with SARS-CoV-2. A positive laboratory finding for SARS-CoV-2 was defined as a positive result on real-time RT-PCR assay of nasopharyngeal swab specimens. A diagnosis of COVID-19 was made based on the presence of disease-defining symptoms plus at least 1 positive RT-PCR assay.

A retrospective review of electronic medical records was performed, and detailed demographic and clinical characteristics, including past medical history, were recorded. Cardiovascular comorbidities were retrieved based on the admission medical records and included hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), dyslipidemia (DLD), coronary artery disease (CAD), heart failure (HF), atrial fibrillation (Afib), and stroke. Outcomes included mortality, need for pharmacologic circulatory support, need for mechanical ventilation, and need for hemodialysis. Pharmacologic circulatory support was defined as the use of vasopressors or inotropic agents for the treatment of shock. Demographic characteristics, cardiovascular comorbidities, and clinical outcomes of patients admitted to participating Texas hospitals were compared to those of patients admitted to participating New York state hospitals. Furthermore, we evaluated the time to the development of adverse clinical outcomes in the Texas versus New York state cohort as an attempt to determine whether the patients were admitted to the hospital at the same point in their illness. In order to evaluate the evolution of practice patterns over time, as care teams became more experienced treating COVID-19 patients, we divided the study period into an early (March 15 to April 30) and late phase (May 1 to July 12) and compared clinical outcomes between the 2 phases in Texas and New York state cohorts.

All data were collected after patients were discharged from the hospital or after patients expired while in the hospital. In order to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of our data, we abstained from any automated data extraction. We also performed random quality checks, which yielded no errors in abstracted data.

Oversight

The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards of each participating site (protocol numbers: HSC-MS-20-0286, 20-04-2328, and 2020-063). It was also registered as an observational study at ClinicalTrials.gov on April 6, 2020 (NCT04335630).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were tested for normality of distribution with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Non-normally distributed variables are presented as median values with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables are presented as percentages and were compared using the χ2 test. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to test for significant differences in clinical outcomes after adjusting for underlying demographics and comorbidities. The multivariable logistic regression model was adjusted for age at admission, BMI, Hispanic ethnicity, race, insurance type, and histories of DM, CAD, Afib, and cancer to yield odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A 2-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

We identified 514 consecutively hospitalized patients with COVID-19: 296 (58%) in Texas and 218 (42%) in New York state. The median age was 59 years (IQR 48–71), 53% were female, and 59% were Caucasians. Cardiovascular comorbidities were prevalent among the study participants, with HTN at 56%, DM at 36%, DLD at 30%, CAD at 14%, and HF at 11%. The median BMI was 29.4 kg/m2 (IQR 25.4–35.5).

Differences in Demographic Data and Baseline Cardiovascular Comorbidities between Patients Hospitalized in the Participating Texas and New York State Hospitals

Table 1 compares the demographic characteristics and baseline cardiovascular comorbidities of patients with COVID-19 admitted to the participating Texas versus New York state hospitals. Patients in Texas hospitals were younger (57 vs. 63 years, p value <0.001), had a higher BMI (30.3 vs. 28.5 kg/m2, p = 0.015), and higher rates of DM (41 vs. 30%, p = 0.014). In contrast, patients in New York state hospitals were older, had higher rates of CAD (19 vs. 10%, p = 0.005), and a higher prevalence of Afib (11 vs. 5%). More African Americans and Hispanics were present in the Texas cohort than in the New York state cohort (30 vs. 11% and 43 vs. 7%, respectively). Of note is also that 22% of patients in the Texas hospitals were uninsured, compared to only 1% in the New York state hospitals (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics and underlying cardiovascular comorbidities of patients with COVID-19 admitted to Texas and New York state hospitals

| Texas (N = 296, 58%) | New York state (N = 218, 42%) | p value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 165 (56.3) | 103 (48.1) | 0.068 |

| Age, median (IQR), years | 57 (47–66) | 63 (51–77) | <0.001 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| <40 years | 49 (16.6) | 31 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| 40–49 years | 46 (15.5) | 20 (9.2) | |

| 50–59 years | 77 (26.0) | 37 (17.0) | |

| 60–69 years | 62 (21.0) | 48 (22.0) | |

| 70–79 years | 42 (14.2) | 38 (17.4) | |

| 80+ years | 20 (6.8) | 44 (20.2) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| White | 146 (49.3) | 156 (71.6) | <0.001 |

| Black | 88 (29.7) | 24 (11) | |

| Asian | 9 (3.0) | 7 (3.2) | |

| Other | 53 (17.9) | 31 (14.2) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 127 (43.2) | 14 (6.6) | <0.001 |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 30.3 (25.9–35.9) | 28.49 (24.5–34.01) | 0.015 |

| Insurance, n (%) | |||

| Private | 97 (33.0) | 50 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 65 (22.1) | 93 (43.1) | |

| Medicaid | 14 (4.8) | 49 (22.7) | |

| Uninsured | 65 (22.1) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Positive history of, n (%) | |||

| HTN | 174 (58.8) | 112 (51.4) | 0.095 |

| HF | 31 (10.5) | 26 (11.9) | 0.604 |

| CAD | 30 (10.1) | 41 (18.8) | 0.005 |

| Afib | 14 (4.7) | 23 (10.6) | 0.012 |

| Stroke | 20 (6.8) | 21 (9.6) | 0.234 |

| DM | 121 (40.9) | 66 (30.3) | 0.014 |

| Lung disease | 34 (11.5) | 33 (15.1) | 0.224 |

| DLD | 93 (31.4) | 61 (28.0) | 0.400 |

| Cancer | 13 (4.4) | 19 (8.7) | 0.045 |

| Smoking exposure | 87 (33.0) | 65 (30.0) | 0.481 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; HTN, hypertension; HF, heart failure; CAD, coronary artery disease; Afib, atrial fibrillation; DM, diabetes mellitus; DLD, dyslipidemia.

p values from χ2 tests, except for age and BMI (Mann-Whitney test).

Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19 in Participating Texas and New York State Hospitals

Pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis were used in 17, 22, and 9%, respectively, in the entire cohort. In-hospital mortality was 17% for the entire cohort. COVID-19 patients admitted in Texas were more frequently treated with pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis than the patients in New York state hospitals (21 vs. 13%, p = 0.020; 30 vs. 12%, p < 0.001; and 11 vs. 5%, p = 0.009, respectively; Table 2). However, in-hospital mortality was similar between the 2 cohorts (16 vs. 18%, p = 0.469). After adjusting for differences in underlying comorbidities using a multivariable logistic regression model, only the use of mechanical ventilation remained significantly higher in Texas (OR [95% CI]: 3.88 [1.23, 12.24]; Table 3). No significant differences in the use of pharmacologic circulatory support, hemodialysis, or in-hospital mortality were observed (OR [95% CI]: 0.93 [0.28, 3.11], 1.96 [0.56, 6.79], and 1.48 [0.60, 3.66], respectively; Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 admitted to Texas and New York state hospitals

| Clinical outcomes | Texas (N = 296, 58%) | New York state (N = 218, 42%) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacologic circulatory support | 59 (20.6) | 27 (12.6) | 0.020 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 85 (29.7) | 25 (11.7) | <0.001 |

| Hemodialysis | 32 (11.3) | 10 (4.7) | 0.009 |

| In-hospital mortality | 45 (15.6) | 39 (18.1) | 0.469 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

p values from χ2 tests.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis evaluating differences in clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients admitted to Texas and New York state hospitals† after adjusting for differences in demographics and underlying cardiovascular comorbidities

| Regression model (predictor: state) | Clinical outcome, OR (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pharmacologic circulatory support | mechanical ventilation | hemodialysis | death | |

| Crude logistic | 1.79 (1.09, 2.94) | 3.20 (1.96, 5.21) | 2.58 (1.24, 5.37) | 0.84 (0.56, 1.35) |

| Multivariable logistic* | 0.93 (0.27, 3.12) | 3.88 (1.23, 12.24) | 1.96 (0.56, 6.79) | 1.48 (0.60, 3.66) |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Afib, atrial fibrillation; DM, diabetes mellitus.

New York was the referent category for all analyses.

Model was adjusted for age, BMI, Hispanic ethnicity, race, insurance type, DM, coronary artery disease, Afib, and cancer.

The median time to pharmacologic circulatory support of patients in the Texas cohort was 8 days (IQR: 2, 13.8) compared to 1 day (0, 3) in the New York state cohort (p < 0.001). The median time to intubation was not different between the 2 cohorts (1 [0, 4] vs. 0 [0, 5], p = 0.430). Comparison of the time to hemodialysis between the 2 cohorts was not statistically meaningful due to the small number of data available. The median time to in-hospital mortality of patients in the Texas cohort was 16 days (10, 25.5) compared to 7 days (4, 14) in the New York state cohort (p < 0.001).

Clinical Outcomes of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Texas and New York State Cohorts during the Early and Late Study Phases

One hundred seventy-nine patients (62%) in the Texas cohort were admitted to the hospital during the early study phase and 110 (38%) during the late study phase. One hundred twenty-four patients (58%) in the New York state cohort were admitted to the hospital during the early study phase and 90 (42%) during the late study phase. No significant differences in the use of pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis between the early and late study phases were noted in the Texas and New York state cohorts (Table 3). Although in-hospital mortality was similar in the early and late study phases in the Texas cohort (16 vs. 15%, p = 0.741), it was higher in the late study phase in the New York state cohort (24 vs. 14%, p = 0.050; Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 admitted to Texas and New York state hospitals in early versus late study period

| March to April | May to July | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Admissions, N (%) | |||

| Texas | 179 (62) | 110 (38) | n/a |

| New York | 124 (58) | 90 (42) | n/a |

| Pharmacologic circulatory support, N (%) | |||

| Texas | 35 (20) | 23 (21) | 0.880 |

| New York | 12 (10) | 15 (17) | 0.147 |

| Mechanical ventilation, N (%) | |||

| Texas | 53 (30) | 30 (27) | 0.690 |

| New York | 15 (12) | 10 (11) | 1.000 |

| Hemodialysis, N (%) | |||

| Texas | 19 (11) | 12 (11) | 1.000 |

| New York | 7 (6) | 3 (3) | 0.525 |

| Death, N (%) | |||

| Texas | 29 (16) | 16 (15) | 0.741 |

| New York | 17 (14) | 22 (24) | 0.050 |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Discussion

This study draws attention to significant differences in demographics and baseline cardiovascular comorbidities between patients with COVID-19 admitted to a spectrum of hospitals in Texas and in New York state. While pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis were more commonly used in Texas than in New York, in-hospital mortality was not different. After adjusting for differences in the underlying comorbidities between the patients in the 2 cohorts, the use of mechanical ventilatory support was less frequent in the New York state cohort.

A high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, including HTN, DLD, DM, CAD, and HF, was noted throughout the entire registry. This is in line with reports suggesting that cardiovascular comorbidities predispose to an unfavorable outcome and hospitalization of patients with COVID-19 [2, 3, 4, 5]. However, the high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities may also reflect a lower threshold for admission of these patients. The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in their clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed COVID-19, advise for close monitoring and possible hospitalization of patients with risk factors for severe disease including cardiovascular comorbidities [9].

Significant differences in demographic characteristics and baseline comorbidities were detected between the patient population hospitalized with COVID-19 in Texas and New York state. Patients in the Texas cohort were younger, were more severely obese, and had higher rates of DM. More African Americans and Hispanics were present in the Texas cohort than in the New York state cohort. Of note is that the number of uninsured patients was significantly higher in the Texas cohort than in the New York state cohort (22 vs. 1%). However, one of the 3 hospitals that we studied in Texas is a county hospital with a particularly high prevalence of uninsured patients. We also note that the patients in New York state cohort were older, with higher rates of underlying CAD and Afib. Medicare and Medicaid were the primary insurance plans for two-thirds of the patients hospitalized in the participating New York state hospitals. These differences reflect baseline demographic differences in the communities that we studied [6, 7, 8]. It is also likely that the different disease burden and time of peak hospitalization rates in the 2 states contributed to differences in the population characteristics of the infected patients.

Pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, and hemodialysis were more commonly used in the Texas cohort than in the New York state cohort. Although this might suggest that hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in the Texas cohort have a more severe disease course, no significant difference was noted in the in-hospital mortality between the 2 cohorts. When we adjusted for the differences in the underlying comorbidities between the 2 cohorts, only the use of mechanical ventilation remained more common in Texas hospitals. This may reflect the reluctance of the older patient population in New York state to give consent to intubation or practice pattern variations between the south and northeast regions of the USA. Our study is the first to report on these practice pattern variations related to COVID-19 treatment. Although, they have not been previously studied in COVID-19 patients, practice pattern variations between the south and northeast regions of the USA, pertaining to the use of mechanical ventilation, vasoactive medications, and hemodialysis, have been described in the literature. In a large nationwide study of over 17,000 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, clinicians treating patients in the south of the USA were more likely to offer mechanical ventilatory support compared to the northeast [10]. In a different study of over 100,000 adults from 294 US hospitals, use of vasoactive medications after cardiac surgery was significantly more common in the south compared to the northeast region [11]. Furthermore, a study of over 400,000 hospitalizations with dialysis-requiring acute kidney injury in the USA reported more frequent use of hemodialysis in the south than the northeast region [12]. Our study findings are in line with the above studies, suggesting that there is regional variation in the use of mechanical ventilation, vasoactive medications, and hemodialysis in the treatment of COVID-19 patients between the south and northeast regions of the USA.

In-hospital mortality of patients with COVID-19 in our registry was 17%. This is close to the in-hospital mortality rate of 20%, which was previously reported in a large multicenter US study of more than 11,000 patients [13]. In addition, in-hospital mortality rates were similar among patients in the participating Texas and New York state hospitals. This supports that the standard of patient care provided in the participating Texas hospitals was overall similar to patient care in the participating New York state hospitals.

In order to evaluate whether COVID-19 patients in the participating Texas and New York state hospitals were admitted at about the same point in their illness, we compared the time to the development of adverse outcomes. We observed that the patients in the New York state cohort required pharmacologic circulatory support sooner and died earlier than the patients in the Texas cohort. This suggests that the patients in the New York state cohort may have been admitted at a later point in their illness compared to patients in the Texas cohort, leading to earlier need for interventions and greater in-hospital mortality.

Our study also evaluated potential differences in the practice patterns over time, as care teams became more experienced in treating COVID-19 patients, by comparing clinical outcomes of patients admitted to the hospital in the early (March 15 to April 30) versus the late study period (May 1 to July 12) between the Texas and New York state cohorts. No significant differences in the use of pharmacologic circulatory support, mechanical ventilation, or hemodialysis were identified over time in either of the 2 cohorts. This may be due to the short time frame that our study examined. Although no difference was noted in mortality between the 2 phases in the Texas cohort, mortality was higher in the late phase in the New York state cohort. Of note is that on March 25, 2020, a policy directive from the New York State Department of Health was issued, allowing expedited readmission or admission of COVID-19 patients to the nursing homes, in an effort to ensure adequate hospital capacity for COVID patients requiring advanced care [14]. Although this nursing home policy might have contributed to the mortality difference, our data did not reveal any difference in the median age or median number of comorbidities between the 2 phases, which argues against the above hypothesis (median age: 63 [IQR 50.8–77] vs. 61 [IQR 51–76.8] years; p = 0.889, and median number of cardiovascular comorbidities: 2 [IQR 0–3] vs. 1 [IQR 0–3] comorbidities; p = 0.372).

Our study has several strengths. First, it is based on a multicenter registry with patients admitted to both tertiary and community hospitals across the states of Texas and New York. This contributed to a diverse patient population, with 53% of the patients being female and 41% non-white. Therefore, the findings of the study are representative of and relevant to all racial and socioeconomic segments of the population. Second, all data used in the study were manually abstracted from patients' electronic health records, yielding thorough reporting of patient history and clinical course. Additionally, missing values represented only <10% of the patient data, providing a complete picture of the patient's clinical course.

Our study also has certain limitations. The retrospective nature of the data collection makes our study prone to biases. We attempted to eliminate selection bias and confounding by using multivariable logistic regression analysis, although residual selection bias is likely. Furthermore, the hospitals that we studied may not be completely representative of hospitals in the rest of each state in terms of equipment, level of care, and the population they serve. In fact, no hospitals from New York City participated in the New York state cohort, as opposed to Texas cohort, which included hospitals in Houston. Last, the collection of baseline cardiovascular comorbidities was dependent on appropriate documentation by the primary care provider and accurate retrieval of the data by our data collection team. As already mentioned, to eliminate inaccuracies with the data collection, we elected to collect the data by manual chart review and avoid automated data extraction algorithms. Furthermore, we performed random quality checks, which yielded no errors in abstracted data.

Conclusions

Geographical differences, including practice pattern variations and the impact of disease burden on provision of health care, are important for the evaluation of COVID-19 outcomes. Unadjusted data may cause bias affecting future regulatory policies and the allocation of resources.

Statement of Ethics

The study complies with internationally accepted standards for research practice and reporting, and it was approved by the respective Institutional Review Boards of each participating site (protocol numbers: HSC-MS-20-0286, 20-04-2328, and 2020-063). Since our study involved retrospective review of patients' medical charts, the need for written informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No competing interests exist.

Author Contributions

E.K. and H.T. conceived and designed the study. S.S.H. and E.K. performed the statistical analysis. E.K., S.S.H., E.G.-S., and H.T. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors listed contributed to data collection and the editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL061483) to H.T. We thank Anna Menezes for expert editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Retrieved from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html Date retrieved: 1-5-2021.

- 2.Chen R, Liang W, Jiang M, Guan W, Zhan C, Wang T, et al. Risk factors of fatal outcome in hospitalized subjects with coronavirus disease 2019 from a nationwide analysis in China. Chest. 2020;158((1)):97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584((7821)):430–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, Zhao J, Liu H, Peng J, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID-19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81((2)):e16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, Pu K, Chen Z, Guo Q, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth GA, Roth GA, Johnson CO, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Ahmed M, et al. The burden of cardiovascular diseases among US states, 1990–2016. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3((5)):375–89. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prevalence of Heart Disease Among Adults bDC, Risk Factors/Comorbid Conditions, and Place of Residence, Texas 2018. Prepared by Chronic Disease Epidemiology Branch, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Section, Texas Department of State Health Services

- 8.Cardiovascular Disease Mortality in New York State. Results from the New York State Vital Records Death Statistics and the Bureau of Vital Statistics. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. https://health.ny.gov/diseases/cardiovascular/heart_disease/docs/cvd_mortality.pdf.

- 9. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Accessed 2020 Dec 13.

- 10.Rush B, Wiskar K, Berger L, Griesdale D. The use of mechanical ventilation in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the United States: a nationwide retrospective cohort analysis. Respir Med. 2016;111:72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vail EA, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Gershengorn HB, Walkey AJ, Lindenauer PK, et al. Use of vasoactive medications after cardiac surgery in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18((1)):103–11. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-465OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu RK, McCulloch CE, Ku E, Dudley RA, Hsu CY. Regional variation in the incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8((9)):1476–81. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12611212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, Fakih M, Ottenbacher A, Jesser C, et al. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3((8)):e2018039. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York State Department of Health's (NYSDOH) Advisory www.hurlbutcare.com.NYSDOH_Notice.