Abstract

Background

The pathophysiology of cervical dystonia is still unclear. Recent evidence points toward a network disorder affecting several brain areas. The objective of this study was to assess the saccadic inhibition as a marker of corticostriatal function in cervical dystonia.

Methods

We recruited 31 cervical dystonia patients and 17 matched healthy controls. Subjects performed an overlap prosaccade, an antisaccade, and a countermanding task on an eye tracker to assess automatic visual response and response inhibition.

Results

Cervical dystonia patients made more premature saccades (P = 0.041) in the overlap prosaccade task and more directional errors in the antisaccade task (P = 0.011) and had a higher rate of failed inhibition in the countermanding task (P = 0.001).

Conclusions

The results suggest altered saccadic inhibition in cervical dystonia, possibly as a consequence of dysfunctional corticostriatal networks. Further studies are warranted to confirm whether these abnormalities are affected by the available therapies and whether this type of impairment is found in other focal dystonias. © 2021 The Authors. Movement Disorders published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society.

Keywords: eye tracking, cervical dystonia, saccadic inhibition, prefrontal cortex

Cervical dystonia (CD) is characterized by involuntary activity of cervical muscles leading to involuntary movements and postures of the head, neck, and shoulders.1, 2 It is often associated with dystonic head tremor and neck pain. 3 Although CD has traditionally been described as a disorder of basal ganglia motor control; nonmotor symptomns such as depression, obsessive–compulsive disorders, and anxiety are common in this condition.4, 5 Conflicting results have been published related to the cognitive function of patients with CD, with some studies failing to detect cognitive deficits,6, 7 others attributing deficits on cognitive testing to pain and abnormal head movements, 8 and more recent studies reporting impairment in set shifting and working memory. 9 The latter domains require intact dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) function and a variety of structural and functional abnormalities of the DLPFC in CD patients have been published.10, 11 The DLPFC and its projections via the striatum are important for response inhibition and for regulating the superior colliculus (SC), a multilayered structure in the midbrain involved in saccadic eye movement generation. 12 Furthermore, the SC receives projections from other cortical structures such as the frontal eye fields for volitional and the parietal eye fields for reflexive saccades. 13 Until now, only a few studies have assessed saccadic eye movements in patients with CD, and results have again been inconsistent. Although some studies reported slower saccadic reaction times, 14 others did not find any difference compared with controls. 15

Based on findings of DLPFC dysfunction in CD, we hypothesized that CD patients may have difficulties in inhibitory saccadic control compared with healthy volunteers and that abnormalities described in saccadic behavior may help to understand the neural networks involved in this disease.

1. Methods

1.1. Participants

Forty‐eight subjects were included: 31 patients with isolated or segmental idiopathic CD and 17 age‐ and sex‐matched healthy controls (HCs).

A Mini–Mental State Examination score below 26, psychiatric disorders, or uncorrected visual impairments were exclusion criteria. Drugs affecting the central nervous system were not allowed with the exception of antidepressants, if on a stable dose for 4 weeks prior to testing. CD patients were on regular treatment with botulinum toxin and had received their last botulinum injection at least 90 days prior to testing. 16

1.2. Experimental Protocol

Participants filled out the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS‐11) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. We adopted the Toronto Western Torticollis Rating Scale 17 and a modified version of the Tsui scale18, 19 to assess disease and tremor severity in CD patients.

Eye tracking was carried out using a Tobii TX300 system (www.tobii.com). All subjects were tested by the same investigator under identical light conditions in the early afternoon. The assessment consisted of a prosaccade task, an antisaccade task, and a countermanding task, always performed in this order.

(1) In the prosaccade task subjects were required to fixate a target in the middle of the screen; the target disappears, and a peripheral cue appears. Subject had to perform a saccade toward the cue. We employed an overlapping variant, with target and cue on the screen simultaneously for a short time, delaying the visually guided saccade. This task was repeated 80 times. (2) The antisaccade task was cognitively more demanding than a prosaccade: subjects were required to perform a mirror saccade in the opposite direction of the cue. Saccades to cue were considered errors. 20 This task was divided in 2 blocks of 20 repetitions each. 21 (3) In the countermanding task the central target was followed by a green arrow anticipating the appearance of the peripheral cue. The arrow was randomly followed by a red stop signal in a fourth of trials. In this case, the subject had to refrain from looking at the peripheral cue. This task was performed 60 times. Anticipatory errors in the prosaccade task, directional errors in the antisaccade task, and inhibition errors in the countermanding task were the main outcome measures.

For each task, reaction times were measured from the appearance of the peripheral cue until the first saccade; any saccade with latency under 50 milliseconds was discarded. In the pro‐ and antisaccade task, reaction times shorter than 140 milliseconds were classified as “express saccades.” 22 Variance of the reaction times in the prosaccade task were expressed using the coefficient of variation, defined as the interquartile range of the reaction time divided by the median. 23

Prior to each of the 3 tasks, participants performed a practice run consisting of 4 task repetitions for which verbal feedback was given. A break of a maximum of 2 minutes was allowed between the 3 tasks.

1.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS (v24). 24 Normality of the data was assessed with Shapiro–Wilk test. Based on the distribution of the data, parametric and nonparametric tests were employed. The level of significance for all analyses was set at a 2‐sided P < 0.05.

2. Results

2.1. Demographics and Disease Characteristics

No differences in sex, age, or education were found. CD patients had higher scores for anxiety and depression symptoms compared with HCs (P = 0.010 and P = 0.002, respectively). However, none of the cutoff values for depression and anxiety 25 were reached by subjects in either of the 2 groups. There was no difference in the BIS‐11 total score between the CD and control groups; a subscore comparison revealed a higher score in dystonia patients in the attentional impulsiveness domain (P = 0.031).

2.2. Saccadic Tasks

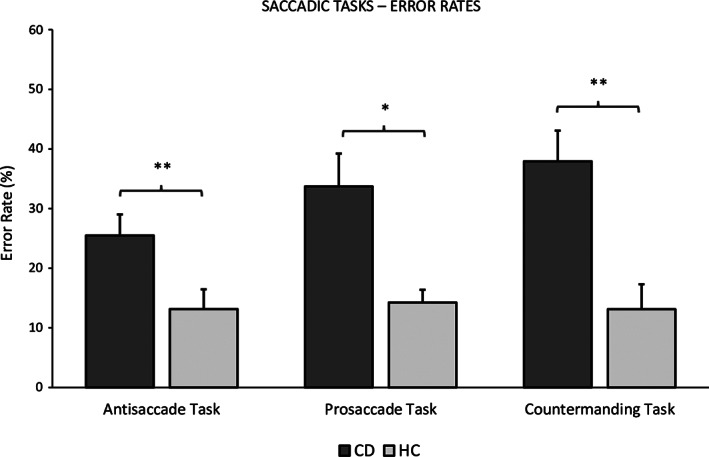

CD patients had higher anticipation errors (P = 0.041), made more express saccades (P = 0.042) in the pro‐saccade task, had longer reaction times (P = 0.036), and made more directional errors at normal and express latencies in the antisaccade task (P = 0.011) compared with HCs. Furthermore, patients made more saccades toward the target in the No‐Go trial of the countermanding task (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference in reaction time variance between CD and HC (Table 1, Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Results and comparison between groups of the saccadic tasks' error rates and reaction times

| Parameters of saccadic tasks | CD | HC | Independent t test/Mann–Whitney test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean | SD | n | Mean | SD | P a | |

| Prosaccade reaction time (ms) | 31 | 269.9 | 75.6 | 15 | 292.9 | 65.1 | 0.313 |

| Prosaccade anticipation errors (%) | 31 | 33.7 | 30.5 | 15 | 14.2 | 8.0 | 0.041 |

| Prosaccadic express saccades (%) | 31 | 21.5 | 19.3 | 15 | 12.5 | 8.9 | 0.036 |

| Prosaccadic coefficient of variance | 31 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 15 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.281 |

| Incorrect antisaccade reaction time (ms) | 31 | 210.3 | 53.1 | 17 | 200.9 | 65.8 | 0.614 |

| Correct antisaccade reaction time (ms) | 31 | 310.7 | 72.7 | 17 | 259.0 | 39.2 | 0.002 |

| Antisaccade directional errors (%) | 31 | 25.5 | 19.7 | 17 | 13.1 | 13.7 | 0.011 |

| Antisaccade express errors (%) | 31 | 20.1 | 23.7 | 17 | 8.6 | 15.2 | 0.039 |

| Countermanding inhibition errors (%) | 31 | 37.9 | 28.6 | 17 | 13.1 | 16.7 | 0.001 |

|

Countermanding task (Go) Reaction time (ms) |

31 | 209.7 | 37.3 | 17 | 207.8 | 62.2 | 0.911 |

|

Countermanding task (No‐Go) Reaction time (ms) |

31 | 279.5 | 88.3 | 17 | 298.5 | 179.8 | 0.663 |

Significant P values are represented in bold text.

Abbrevations: CD, cervical dystonia; HC, healthy controls.

FIG. 1.

Results and comparison between groups of the saccadic tasks' error rates. Each column represents the mean error rate, each presented with standard error of the mean on top. The directional error is depicted for the antisaccade task, the anticipatory error for the prosaccade task, and the failed inhibition error for the countermanding task. Asterisks represent the difference between groups (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). CD, cervical dystonia; HC, healthy controls.

Next, we performed a subanalysis on error rates and reaction times in the antisaccade task comparing the first 20 trials (block 1) with the second 20 trials (block 2). Patients made fewer errors (23.0 ± 20.0 vs 27.9 ± 21.1, P = 0.02) and had shorter reaction times for correctly performed antisaccades (298.2 ± 70.9 vs 329.3 ± 84.0, P < 0.01) in block 2. HCs showed no difference between blocks (P > 0.05). Similarly, we analyzed the error rate in the countermanding task dividing it in half. Again patients performed significantly better in the second half (CD, 46.9 ± 31.9 vs 25.9 ± 27.5; P < 0.01; HC, 16.4 ± 20.8 vs 8.9 ± 13.6; P = 0.09).

To account for possible effects of the laterality of dystonic head rotation, we compared reaction times and error rates separately for either direction (right or left) for every saccadic task. There were, however, no significant differences between saccadic tasks in the direction of the laterality of CD and those in the opposite direction (all P > 0.05; see Supplementary Material S1.). There were also no group differences regarding the percentage of hypometric (CD, 5.3 ± 5.9; HC, 6.3 ± 4.0; P = 0.512) or hypermetric (CD, 2.0 ± 3.8; HC, 1.9 ± 3.8; P = 0.916) saccades in the prosaccade task.

3. Discussion

In this study we describe poorer saccadic response inhibition in CD patients compared to HCs. More specifically, CD patients made more anticipatory prosaccades, more directional errors in the antisaccade task, and more errors in the countermanding task.

A loss of inhibition can occur at different levels in patients with focal dystonia. 26 At least 2 mechanisms of inhibition are required in the antisaccade task: at the beginning of the task a preemptive top‐down inhibition, which relies on intact frontal areas (mainly the DLPFC and frontal eye fields but also the superior colliculus), is necessary to avoid express latency errors. In contrast, once the stimulus appears automated saccades toward the target are suppressed by the supplementary eye field. A failure of this system leads to longer latency errors. Crucially, both these mechanisms are mediated by the basal ganglia. Furthermore, a large network of other brain areas including the thalamus, the cerebellum, the brain stem reticular formation, the parietal eye field, and other cortical areas are necessary for visual fixation and saccadic control. 27

In this study, CD patients made more directional errors than controls, at both longer and express latencies, implying a dysfunction of both mechanisms. The countermanding task differs from the antisaccade task. Here, the inhibition of an already started action is necessary. In addition to the DLPFC and frontal eye fields, the supplementary eye field and other frontal areas such as the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex as well as intact basal ganglia function are required.27, 28

Our results highlight a dysfunction of the frontal cortical top‐down inhibitory control in CD and are also consistent with previous results in other focal dystonias. 29 In line with this, functional imaging studies have shown that successful top‐down inhibition to prevent the automatic prosaccade relies on an intact network comprising the DLPFC together with the frontal eye field, basal ganglia, and SC.30, 31 Importantly, imaging studies suggest that this network is altered in CD. 11 In accordance with our findings, neuropsychological tests have revealed impairment in working memory, cognitive flexibility, and frontal lobe function in patients with CD.9, 32, 33 Finally, disruption of sensory‐motor integration in patients with focal dystonia 34 may also affect oculomotor performance. 35

The results of the antisaccade task presented here are in contrast with a previous small study in CD (n = 8). 14 However, because of the small sample size, a direct comparison of the 2 studies is not possible.

It is important to note that the impairment described here is not specific to CD. Poorer saccadic performance has been previously described in patients with dementia as well as patients with other basal ganglia disorders such as Huntington's disease, atypical parkinsonism, idiopathic Parkinson's disease, and patients with schizophrenia 13, 36, 37, 38, 39strengthening the hypothesis that dysfunction of the corticobasal network, either because of basal ganglia lesions, frontal cortex dysfunction, or both may lead to poorer saccadic control.

We want to highlight a limitation of this study: we used a fixed order for the eye‐tracking paradigms. Future studies should consider using a pseudorandomized order to avoid possible learning effects. Importantly, however, poorer performance of the CD group was not because of fatigue, as patients performed significantly better in the second half of the antisaccade and countermanding task.

In conclusion, we demonstrate impaired saccadic response inhibition in CD patients, which may be because of dysfunction of the corticostriatal network. Saccadic assessment in CD is noninvasive, time, and cost effective and could represent a viable biomarker of disease to be implemented both in research and clinical practice. Further studies are needed to assess whether this impairment is shared by other focal or segmental dystonias.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution, D. Software design, E. Eye tracking paradigms design; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and Critique

F.C.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 1E 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B.

P.E.: 1E.

M.R.: 1D.

S.S.: 1C.

P.M.: 1C, 3B.

E.H.: 1C.

A.H.: 1C.

A.H.: 1C.

R.G.: 1C.

K.S.: 1A.

W.P.: 2C, 3B.

S.B.: 1B, 1C, 3B.

A.D.: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2C, 3B.

Supporting information

Table S1. Demographic data of study population

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: Nothing to report.

Funding agencies: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord 2013;28:863–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Defazio G, Jankovic J, Giel JL, Papapetropoulos S. Descriptive epidemiology of cervical dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2013;3. 10.7916/D80C4TGJ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dauer WT, Burke RE, Greene P, Fahn S. Current concepts on the clinical features, aetiology and management of idiopathic cervical dystonia. Brain 1998;121:547–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stamelou M, Edwards MJ, Hallett M, Bhatia KP. The non‐motor syndrome of primary dystonia: clinical and pathophysiological implications. Brain 2012;135:1668–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jinnah HA, Neychev V, Hess EJ. The anatomical basis for dystonia: the motor network model. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (NY) 2017;7:506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor AE, Lang AE, Saint‐Cyr JA, Riley DE, Ranawaya R. Cognitive processes in idiopathic dystonia treated with high‐dose anticholinergic therapy. Clin Neuropharmacol 1991;14:62–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jahanshahi M, Rowe J, Fuller R. Cognitive executive function in dystonia. Mov Disord 2003;18:1470–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Allam N, Frank JE, Pereira C, Tomaz C. Sustained attention in cranial dystonia patients treated with botulinum toxin. Acta Neurol Scand 2007;116:196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romano R, Bertolino A, Gigante A, Martino D, Livrea P, Defazio G. Impaired cognitive functions in adult‐onset primary cranial cervical dystonia. Park Relat Disord 2014;20:162–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prell T, Peschel T, Köhler B, et al. Structural brain abnormalities in cervical dystonia. BMC Neurosci 2013;14:123. 10.1186/1471-2202-14-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Filip P, Gallea C, Lehéricy S, et al. Disruption in cerebellar and basal ganglia networks during a visuospatial task in cervical dystonia. Mov Disord 2017;32:757–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munoz DP, Everling S. Look away: the anti‐saccade task and the voluntary control of eye movement. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004;5:218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Terao Y, Fukuda H, Hikosaka O. What do eye movements tell us about patients with neurological disorders? ‐an introduction to saccade recording in the clinical setting. Proc Japan Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2017;93:772–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Beck RB, Kneafsey SL, Narasimham S, et al. Reduced frequency of ipsilateral express saccades in cervical dystonia: probing the nigro‐tectal pathway. Tremor Other Hyperkin Mov (NY) 2018;8:4–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stell R, Bronstein AM, Gresty M, Buckwell D, Marsden CD. Saccadic function in spasmodic torticollis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990;53:496–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brodoehl S, Wagner F, Prell T, Klingner C, Witte OW, Günther A. Cause or effect: altered brain and network activity in cervical dystonia is partially normalized by botulinum toxin treatment. NeuroImage Clin 2019;22:101792. 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyce MJ, Canning CG, Mahant N, Morris J, Latimer J, Fung VSC. The Toronto Western spasmodic torticollis rating scale: reliability in neurologists and physiotherapists. Park Relat Disord 2012;18:635–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tsui JKC, Jon Stoessl A, Eisen A, Calne S, Calne DB. Double‐blind study of Botulinum toxin in spasmodic torticollis. Lancet 1986;328:245–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jost WH, Hefter H, Stenner A, Reichel G. Rating scales for cervical dystonia: a critical evaluation of tools for outcome assessment of botulinum toxin therapy. J Neural Transm 2013;120:487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hallett PE. Primary and secondary saccades to goals defined by instructions. Vision Res 1978;18:1279–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Antoniades C, Ettinger U, Gaymard B, et al. An internationally standardised antisaccade protocol. Vision Res 2013;84:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fischer B, Ramsperger E. Human express saccades: extremely short reaction times of goal directed eye movements. Exp Brain Res 1984;57:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smyrnis N, Karantinos T, Malogiannis I, et al. Larger variability of saccadic reaction times in schizophrenia patients. Psychiatry Res 2009;168:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. IBM Corp . Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- 25. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hallett M. Neurophysiology of dystonia: the role of inhibition. Neurobiol Dis 2011;42:177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Coe BC, Munoz DP. Mechanisms of saccade suppression revealed in the anti‐saccade task. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2017;372(1718):20160192. 10.1098/rstb.2016.0192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu KZ, Anderson BA, Emeric EE, et al. Neural basis of cognitive control over movement inhibition: human fMRI and primate electrophysiology evidence. Neuron 2017;96:1447–1458.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stinear CM, Byblow WD. Impaired inhibition of a pre‐planned response in focal hand dystonia. Exp Brain Res 2004;158:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Everling S, Dorris MC, Klein RM, Munoz DP. Role of primate superior colliculus in preparation and execution of anti‐saccades and pro‐saccades. J Neurosci 1999;19:2740–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Everling S, Munoz DP. Neuronal correlates for preparatory set associated with pro‐saccades and anti‐saccades in the primate frontal eye field. J Neurosci 2000;20:387–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mahajan A, Zillgitt A, Alshammaa A, et al. Cervical dystonia and executive function: a pilot magnetoencephalography study. Brain Sci 2018;8(9):159. 10.3390/brainsci8090159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ospina‐García N, Escobar‐Barrios M, Rodríguez‐Violante M, Benitez‐Valenzuela J, Cervantes‐Arriaga A. Neuropsychiatric profile of patients with craniocervical dystonia: a case‐control study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020;193:105794. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Avanzino L, Tinazzi M, Ionta S, Fiorio M. Sensory‐motor integration in focal dystonia. Neuropsychologia 2015;79:288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Desrochers P, Brunfeldt A, Sidiropoulos C, Kagerer F. Sensorimotor control in dystonia. Brain Sci 2019;9:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zee DS, Lasker AG. Antisaccades: probing cognitive flexibility with eye movements. Neurology 2004;63:1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barbosa P, Kaski D, Castro P, Lees AJ, Warner TT, Djamshidian A. Saccadic direction errors are associated with impulsive compulsive behaviours in Parkinson's disease patients. J Parkinsons Dis 2019;9:625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reuter B, Rakusan L, Kathmanna N. Poor antisaccade performance in schizophrenia: an inhibition deficit? Psychiatry Res 2005;135:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kahana Levy N, Lavidor M, Prosaccade VE. Antisaccade paradigms in persons with Alzheimer's disease: a meta‐analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev 2018;28:16–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Demographic data of study population